Work-life balance of university teachers after two years of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Apart from being a topic of key interest during the last decades for its individual and organizational effectiveness, work-life balance also has specific implications during the period of imposed remote work.

OBJECTIVE:

The article outlines some of the antecedents of university teachers’ work-life balance. They were the only professionals teleworking during the whole period of imposed restriction and furthermore, university teachers are a group of professionals without any prior home office or remote work experience.

METHODS:

The cross-sectional study comprises randomized convenient sample of 708 university teachers who were administered an online instrument, measuring the constructs of work-life balance, perceived stress, burnout, job satisfaction, general health, general fears and anxiety, and satisfaction with personal relations.

RESULTS:

The results reveal that perceived stress, burnout, job satisfaction, physical and mental health, psychosomatic problems and quality of relations are antecedents of participants’ work-life balance.

CONCLUSIONS:

University teachers have adapted to the new working mode and succeeded in maintaining moderate levels of work-life balance and burnout. However, our findings outline the need of a robust comprehensive framework, accounting for the multiple and multi-level predictors of work-life balance. Future research and HR perspectives have been outlined.

Professor Margarita Bakracheva, PhD, is a lecturer in general and developmental psychology, psychology of personality, social psychology, organisational psychology, clinical and consulting psychology, mass behaviour and crisis communication. She is author of 6 books, and co-author of 6 books. Overall, she has more than 100 scientific publications. Professor Bakracheva is a professional trainer and manages a programme for coping with identity crises. She is an evaluator of national and international programmes. She is featured in more than 350 popular materials and videos in the media. Key interests: identity, happiness and life satisfaction, lifelong development, stress and coping strategies, marketing, communication.

Professor Ekaterina Sofronieva, PhD, is a lecturer at “St. Kliment Ohridski” University of Sofia in Bulgaria. She holds a PhD from the Sapienza University of Rome in Italy (Faculty of Medicine and Psychology). She teaches methodology of foreign language teaching, early second language acquisition, empathy and communication, and intercultural communication. She has been involved in many international and national programmes for pre-service and in-service language teachers in Bulgaria and abroad. She is author of 12 books and coursebooks and publishes extensively in the field of FLT methodology, psycholinguistics and sociolinguistics. Key interests: empathy, language education, communication, early language acquisition, happiness.

Assistant Professor Martin Tsenov has a doctorate in general psychology (Personality Psychology) from the Institute for Population and Human Research - BAS. He has a master’s degree in work and organisational psychology from SU “St. Kliment Ohridski”. M. Tsenov is a teacher of general psychology, developmental psychology, psychology of communication at SU “St. Kliment Ohridski”. He has expertise in the field of human resources - selection and evaluation of personnel. His interests are focused on the use of psychodiagnostics methods when working with clients and group interventions. Key interests: professional burnout, lifelong development, stress and coping strategies, emotional intelligence.

1Introduction

Working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic had different patterns depending on the restrictions in each county, as well as the degree of their impact on the various employment sectors. This article presents the results of our survey conducted among university teachers in Bulgaria, and, in particular, how remote work in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic has affected their work-life balance (WLB). The reason to focus on this target group is due to the fact that higher education institutions were the only organizations which remained in remote working mode throughout the two-year COVID-19 pandemic period (from 9 March, 2020 to 1 April, 2022). In comparison, businesses in the country had just one major lockdown period, which lasted from 8 March to 15 April, 2020, and during the rest of the time public and private organizations operated under specific measures which, while restrictive, allowed them greater freedom to organize their operations in hybrid mode or attendance. Conversely, remote work was fully applied to university teachers in the country, including all academic activities like meetings (team meetings, management meetings, academic councils, etc.), public lectures, practical classes, conferences, seminars, scientific juries and all ongoing discussions. It is also important to note that, in Bulgaria, work in universities is traditionally carried out in an attendance form, and the COVID-19 pandemic not only placed new demands on teachers in their transition to a new working environment and way of communication, but also raised many challenges in the field of human resource management in universities. Delivery of education was challenged to a great extend due to the limited ICT resources, absence of digital platforms and online teaching materials, which was strongly felt, especially at the beginning of the pandemic. Thus, the lack of clarity, rules, guidelines and resources, as well as the lack of control over the entire process and work staff at the beginning, drew a line of personal self-organization, time and resource management that can best be described as highly stressful. Gradually, different dimensions of the pandemic were taken into account, appropriate measures were taken, new work rules were adopted and resources provided for remote work in electronic environment. Meanwhile, human resource management had also changed to adapt to the new settings.

The purpose of our study, after this extended period of remote work is to present a summary of the perceived burnout, stress, job satisfaction and communications and their relation to work-life balance of university teachers, as well as to outline implications for future research. The main research questions we posed, to effectively address the specific research tasks, concern WLB of university teachers and its antecedents and what can be optimized in order to manage the teaching and working processes more effectively in future periods of crisis and in general.

Apart from the survey presented in this article, we have also conducted a series of studies during life in pandemic environment. One of our earliest research projects was launched three weeks after the lockdown and addressed teachers and the need for transitioning to remote work in a very short period of time [1]. Other studies focused on people’s adaptation and self-regulation in the course of the pandemic [2–4] as well as on a cross-sectional perspective [5]. Since the end of the restrictions, we have conducted research among nursery and primary school teachers [6–8] and a survey among university teachers [9]. In summary, our findings revealed some undeniable negative effects which the new work conditions had on employees. In brief, even though the burnout levels remained moderate, a great degree of emotional exhaustion, psychosomatic symptoms and worsened physical health were registered. A negative impact of telecommunication on the quality of teacher-student interactions was also reported along with a disrupted work-life balance. On the other hand, there were some positive outcomes like, for instance, gaining new competences, having an opportunity to save time and money, working in a safe home environment with one’s beloved people around. The outlined results are discussed in the line of limitations and future research perspectives. In this survey we have outlined some of the most significant antecedents of work-life balance as self-reported after a prolonged period of teleworking. We believe that the highlighted trends give robust insights that can be successfully integrated into HR management in order to instil more resilience and preparedness for conceivable future challenges and living in crisis settings as well as to enhance university teachers’ work-life balance.

1.1Literature review and hypotheses

The problem of conflict between work and personal life in modern society is extremely important, but the satisfactory balance is influenced by a number of economic, social and occupational factors [10]. The conclusion that work-life balance (WLB) is inconsistently defined, despite the widespread interest in the topic [11], is still relevant to some extent. As both an individually and organizationally relevant issue, WLB is conceptualized from different perspectives –the Role balance theory, the Person-Environment fit theory and the Satisfaction theory [12–14]. The dynamic changes and insights lead to different approaches and even new formulations of the research field itself–work-life balance, work-family balance, job-family conflict, etc. In this article we use “work-life balance” as a broader term, which we consider to be more appropriate to our research settings. Chronologically and most commonly, researchers consider WLB as the lack of conflict between the two domains –work and personal life –on the one hand, and as the frequency and intensity with which work interferes with family or, on the other hand, family interferes with work. Work-life balance/imbalance can positively or negatively affect employees’ performance [15]. Also, research indicates that a lack of work-life balance, typically defined as increased work-family conflict, can negatively impact both individual health and well-being [16] and organizational performance [17]. During the last decades the ability to balance work and personal life is considered the major social challenge of our age [18]. This issue became especially evident during the period of the COVID-19 crisis, calling for focus on the innovative strategies needed to manage and support human capital [19, 20]. Apart from being a key topic of interest, WLB also emerged as a primary interest during the period of pandemic restrictions. Both institutional and national, and international reports, have discussed the effect of pandemic on WLB. Subsequently, the post-Covid situation and its implications have been the focus of many researchers in the field.

Herein below, we have briefly commented on some studies conducted prior and during the pandemic and their findings which are relevant to our research hypotheses.

Telework during pandemic was not a matter of personal choice, but forced upon people by the imposed restrictions. Therefore, it would be quite natural to expect differences in the reported advantages and disadvantages of remote work and home office-based work before, during and after the pandemic times. One survey conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic reports, on the one hand, on the negative outcomes of raised work demands, long working hours and on the other hand, on the positive outcomes of job autonomy, supervisor support, and co-worker help and support on WLB. However, the effect of family demands and number of children living together and learning remotely on adults’ WLB, has not been verified [21]. The new arrangements, especially flexible working patterns, have challenged traditional relationships of workers and employers, as well as their working hours, work-life balance and people’s attitudes to work. Employers should find ways to boost employee motivation and improve their WLB [22].

Increased levels of stress and burnout are accounted during the pandemic [23]. Work-life disharmony increases psychological distress (emotional exhaustion, emotional malaise, anxiety, irritability and hostility, depression) and family stress, as well as the manifestation of disease symptoms [24]. Reported burnout rate among university teachers prior to the pandemic was high in 8% of the participants, more in women and respondents, aged 40–59, as well as in those who taught social and technical sciences [25]. Emotional exhaustion is viewed upon not only as a consequence of excessive workload but also in relation to emotional burden, and depersonalization as a coping strategy in crisis situations. The general uncertainty felt by many teachers proved to be a predictor of their stress and burnout levels. This uncertainty was largely due to the insufficient resources available to teachers to use when they were expected to make a quick shift to teleworking [26]. ‘The new normal’ was the new-coined phrase, commonly used during the COVID-19 pandemic in numerous publications, including a special report on the mental health risks of remote working [27]. Work-life studies conducted during the pandemic consistently highlight the blurring of work-life boundaries and the increased work-life conflicts based on time and behaviour concerns, leading to psychological distress, emotional exhaustion, and burnout [28]. A good WLB is related to low levels of emotional exhaustion and better health [29]. A lot of studies confirm the experienced burnout and perceived stress during the pandemic [30, 31]. Consequently, our first research hypothesis is:

H1: We expect perceived stress and burnout to be antecedents of WLB

There is evidence that just as job satisfaction can affect employees’ personal lives, a lack of work-life balance can affect their performance [32]. We can assume that the challenges which a person faces in relation to taking on different roles in life are also related to these two main life domains, i.e. how to best perform and behave at the workplace and at home. A large body of research supports the significant relationship between job satisfaction and WLB [33, 34]. The role which organizations can play in supporting the WLB of their employees in relation to their efficient and fluent performance is also largely discussed [35]. Accordingly, job satisfaction is sometimes positioned in-between burnout and commitment to the company [36].

Surveys during COVID-19 pandemic confirmed decreased job satisfaction, including consideration of a career change among teachers [31]. Telework setting and work from home during the pandemic significantly increased job satisfaction for some employees but the path is not straightforward and univocal. Hence, the need of further research on the relationship between WLB and job satisfaction in telework settings has been discussed and accounted for [37]. Employees with a favourable work-life balance report low levels of emotional exhaustion and feel satisfied at work [29]. Furthermore, the workplace role for employees’ job satisfaction and performance is well documented [38–40]. Accordingly, our second research hypothesis is:

H2: We expect strong relation between job satisfaction and WLB

WLB is generally seen as a characteristic feature of the quality of life and is often related to key areas such as health, family life, social relations, security and life satisfaction [41]; and vice-versa, lack of balance in ones’ work and private life can lead to a number of negative effects, such as an increased level of experienced stress, insufficient commitment to the work process or a reduced quality of life [42]. Research studies, at the beginning and over the course of pandemic adaptation, equally account for decreased physical and mental health, fears and anxiety and high decrease of psychosomatic symptoms. Overall, the pandemic has been reported to affect the mental health of people worldwide [43–46]; attention has been drawn to health behaviours [47], psychological health and performance [48], perceived stress, physical and mental health, eating and sleeping disorders, and increased alcohol use [30, 31]. Accordingly, our third research hypothesis is:

H3: We expect physical health, psychosomatic symptoms, and experienced fears and anxiety, typical for the COVID-19 pandemic, to be related to the experienced WLB

The quality of communication and relationships between employees and their supervisors is reported to be critical to maintaining normal stress levels [49]. The more emotional (caring, sharing, and accessibility) and instrumental (frequency and quality of feedback) support employees receive from their immediate supervisors, the fewer work-related burnout episodes they will experience [50]. The importance of carefully designed and implemented human resource management strategies nowadays is the key to the employees’ well-being, satisfaction, productivity, motivation, and occupational safety and health at the workplace [51]. Opportunities for employees to talk to their managers and colleagues, develop personal relationships and work skills, and express their opinions also lead to increased engagement and well-being [52]. Accordingly, our fourth research hypothesis is:

H4: Relations with others will be associated with perceived WLB of university teachers

During the pandemic, surveys on teleworking account for advantages and disadvantages, resulting from the remote work in respect to WLB. Some of the reported advantages are: flexible organization, absence of office distractions, autonomy, comfortable environment, saving time and money. On the other hand, the negatives, commonly accounted for, relate to: distraction by family members and household chores, uncomfortable environment, lack of control, communication barriers, lack of social interaction, lack of hardware support, blurred line between work and personal life, and unhealthy lifestyle [53]. Thus, one conclusion is that teleworking may not be beneficial for everyone. A deeper understanding of how teleworking may affect employees’ different personal and private spheres of life is needed [48]. Different family circumstances, occupations and professional settings should be accounted for. One survey of university teachers describes four areas of discrepancies between desired expectations and undesired realities of telecommuting based on pre-pandemic conclusions and pandemic reports. These areas are flexible work hours versus work intensity, flexible space versus limited space, technologically convenient work arrangements versus technostress and isolation, and family-friendly work arrangements versus intensity of household chores and caregiving. All this emphasizes the important role which HR management professionals can play in helping employees achieve congruence between their expectations and experiences [54]. The survey summarizes further that 58% of the university teachers reported that work-life balance had worsened since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic; 16% reported no change in work-life balance and 27% reported improved work-life balance [54]. Forty per cent of the respondents during the pandemic have not used any tools, aimed at maintaining work-life balance [55]. Worsened WLB of university teachers is reported in respect to ICT resources, preparation and curricula not adapted for online delivery, lack of skills and competences of teachers and students to shift to online work [56–59] Accordingly, our next research hypothesis is:

H5: We expect worsened WLB of university teachers during the pandemic period of telework

Gender and “care for small children” are two factors often studied in relation to WLB. Surveys from different countries [55, 60–62] generally support that women and respondents with underage children in the household are more likely to have difficulty balancing work and personal life. Caregivers of dependants aged 5–8 years reported a significantly greater negative impact on work-life balance [54]. Likewise, in our survey, we focused on a number of factors, related to university teachers’ WLB, which we consider important, i.e. gender, age, university location, teachers’ academic area of expertise and their involvement in different types of classes. Accordingly, our last research hypothesis is:

H6: Gender, age, location (country/capital), academic area and involvement (in lectures / seminars / practical exercises/) will have effect on university teachers’ WLB

2Methodology

2.1Research design

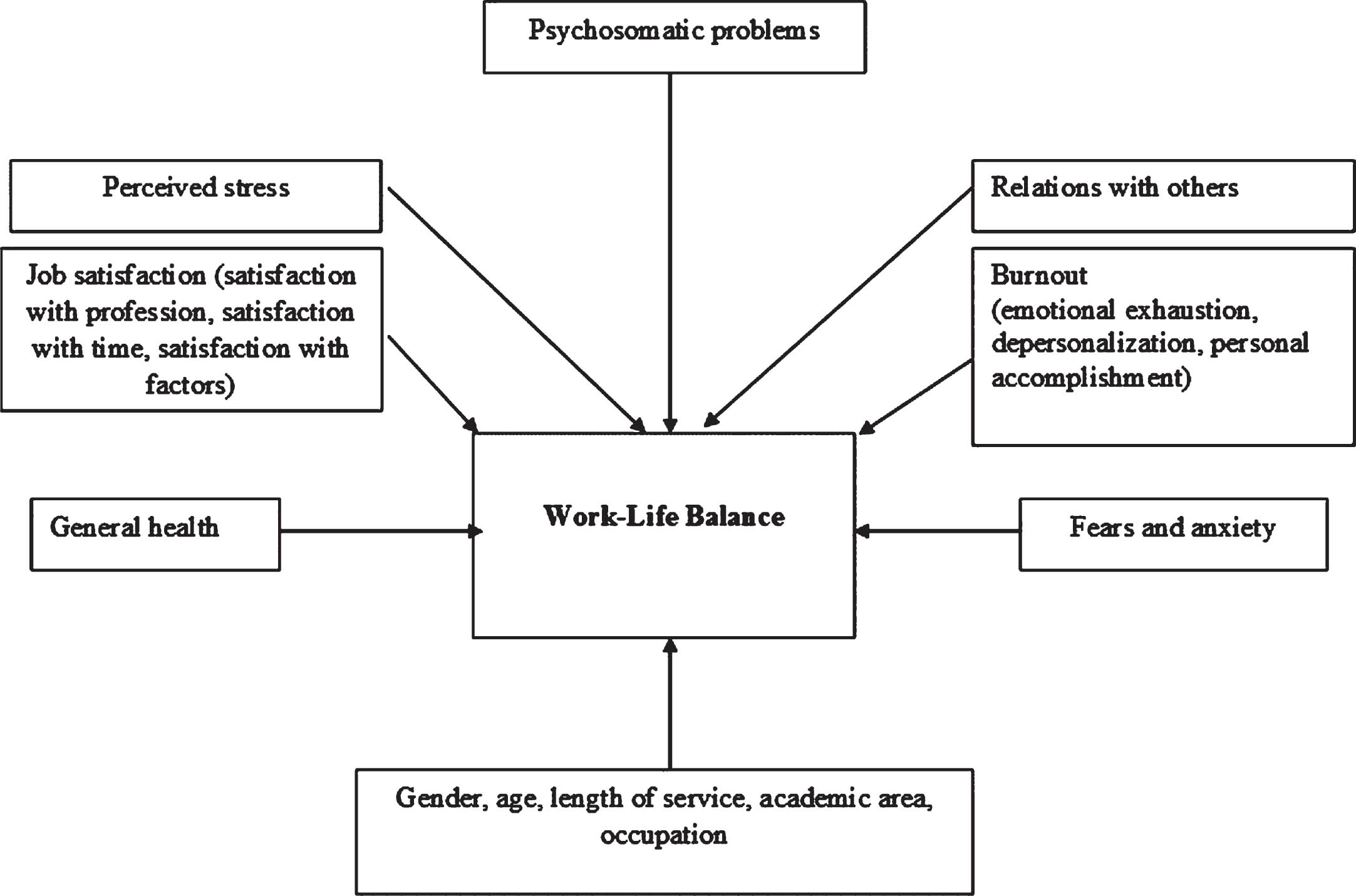

Telework can have both positive and negative effects on WLB, especially when it is not the result of personal choice but of coercion. The aim of the study is to outline the antecedents of WLB for university teachers and their perceived stress, burnout, psychosomatic symptoms, satisfaction with work and relations with others, as well as their general fears and anxiety. The individual variables of gender, age, employment, academic field, length of experience and location of the university are also included. The model is described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

Model of the study –WLB antecedents.

2.2Sample and data collection

To address the research aims, data were collected by targeting a representative sample. A questionnaire was designed and distributed online among all universities in the country with the support of the Bulgarian Ministry of Education. Research data were collected in the period between 7 February –15 March, 2022 (after almost two years of teleworking). The cross-sectional survey comprised a randomized convenient sample of 708 university teachers (Table 1).

Table 1

Profile of the survey respondents

| Response categories | N | % | |

| Gender | male | 269 | 38 |

| female | 420 | 59 | |

| prefer not to answer | 19 | 3 | |

| Age | under 30 | 17 | 2 |

| 30 to 40 | 168 | 24 | |

| 40 to 50 | 240 | 35 | |

| 50 to 60 | 195 | 28 | |

| over 60 | 88 | 13 | |

| Area | social sciences | 175 | 25 |

| humanities | 182 | 26 | |

| biological sciences | 13 | 2 | |

| mathematical and computer sciences | 56 | 8 | |

| medical sciences | 68 | 10 | |

| earth sciences | 20 | 3 | |

| agricultural sciences | 23 | 2 | |

| technical sciences | 139 | 29 | |

| physical sciences | 14 | 2 | |

| chemical sciences | 18 | 2 | |

| Work | up to 5 years | 88 | 12 |

| experience | from 5 to 10 years | 124 | 17 |

| from 10 years to 15 years | 116 | 17 | |

| from 15 years to 20 years | 92 | 13 | |

| from 20 years to 25 years | 81 | 11 | |

| from 25 years to 30 years | 85 | 12 | |

| . | more than 30 years | 122 | 18 |

| Occupation | lectures only | 79 | 11 |

| seminars only | 92 | 13 | |

| conduct both lectures and seminars | 512 | 72 | |

| practical trainings only | 25 | 4 | |

| Location | sofia | 233 | 33 |

| countryside | 452 | 64 | |

| did not responded | 21 | 3 | |

| Total | 708 | 100 |

2.3Measurement scales

The instrument comprises 85 items, grouped in scales, adapted in our previous studies for Bulgaria [2–4] and author scales, piloted for the university teachers survey [6].

The Perceived Stress Scale comprises 10 items with a 5-point response scale: from 1 - never to 5 - very often. It is a classical stress measurement instrument, with exemplary items: In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way? In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them? In the last month, how often have you been able to control irritations in your life?

Health Status Scale (PROMIS Global Health Short) [64] is a 9-item scale for measuring subjective assessment of different health components - physical and mental health, fatigue and pain for the previous period with a 5-point response scale: from 1 - poor to 5 - excellent. It is intended to measure the overall physical and mental health, fatigue and perceived pain. Exemplary items: In the past 7 days, how often have you been bothered by emotional problems such as feeling anxious, depressed or irritable? In general, how would you rate your satisfaction with your social activities and relationships? In general, would you say your quality of life is (poor to excellent).

Psychosomatic Symptoms Scale is a 6-item scale created for the purpose of the university teachers survey [6] with a 5-point response scale: from 1 - never to 5 - very often. Items: I could not sleep well, I was experiencing anxiety, I had headaches, My appetite changed, I was feeling irritable for no reason, I was experiencing apathy.

The Professional Burnout Scale [65] is aimed specifically at teachers and adapted to Bulgarian conditions [6]. It contains 22 items that form three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment. The response scale is 7-point: from 1 - never to 7 - every day. Exemplary items: I feel discouraged by my work; I put too much effort into my work; I don’t care what happens to some of the students; Working with people all day really stresses me out; I easily create a relaxed atmosphere for my students; I feel excited after working with my students closely.

The Job Satisfaction Scale is an adaptation from the Burnout Self-Test [66], Measurement of human service staff satisfaction [67], Job Satisfaction Survey [68] and Teacher Job Satisfaction Scale, Eighth Grade [69] and covers 15 items with a 5-point response scale: from 1 - never to 5 - very often. There are three subscales on the job satisfaction scale, which comprise assessments of overall satisfaction with pay and relationships with colleagues and management, work load, and job satisfaction in respect to occupation. Exemplary items: I worry about the expectation of others that I should succeed in everything in my job; I feel I am not getting what I want out of my job; I feel that I am in the wrong institution or profession; I feel that there are not enough career development opportunities; I feel that my work is meaningful and has a clear purpose.

Fears and anxiety scale [6] comprises 6 items, measuring health and financially related fears and concerns and general insecurity with a 5-point response scale: from 1 - never to 5 - very often. Items: How often in a pandemic have you experienced fear about your financial situation / fear about your job / general uncertainty and anxiety / fear about the future / fear about your health / fear about the health of your loved ones?

Work-Life balance scale [6] comprises 7 items with a 5-point response scale: from 1 - never to 5 - very often. Items: Please indicate how working in an electronic environment affects your personal life (never - rarely - sometimes - often - very often). Exemplary items: I have difficulty balancing family responsibilities / I have difficulty organizing personal space / I feel more relaxed at home.

Relations scale [6] measures the evaluation of relations with supervisors, colleagues, and personal relations; it is a 4 item scale with 5-point response scale: from 1 –severely deteriorated to 5 –significantly improved (Please, specify in the context of pandemic and teleworking what your relationship has been (severely deteriorated - somewhat deteriorated - stayed the same - improved - significantly improved) with: colleagues / management / students / personal relations).

Data processing was done using SPSS v.25 for the reliability analysis, component analysis, correlation analysis, regression analyses, ANOVA and T-test.

3Results

Component analyses confirms good construct validity [6]. The reliability value for each construct was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha. Accordingly, Cronbach’s alpha for WLB was α= 0.854; for Perceived Str ess Scale α= 0.901; for Health Status Scale α= 0.902 for Psychosomatic Symptoms Scale α= 0.881; for Professional Burnout Scale subscales: Emotional exhaustion α= 0.918; Personal accomplishment α= 0.811 and Depersonalization α= 0.776; for Job Satisfaction Scale subscales: Satisfaction with environment α= 0.871, Satisfaction with time management α= 0.838 and Satisfaction with profession α= 0.595; for Fears and anxiety scale α= 0.887 and for relations scale α= 0.669. As all Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceed 0.70, all measures were considered acceptable for the analysis.

The means, standard deviations, and correlation matrix are provided in Table 2. Correlations are with controlled gender, age, work experience, location of the university, academic field and profile. There are significant moderate to high correlations as expected. Burnout –emotional exhaustion, depersonalization as coping and personal accomplishment, perceived stress, worsened physical and mental health, worsened quality of relations, experienced fears and anxiety and dissatisfaction with profession, external factors and time management are all related to worsened WLB. At the same time, a positive general picture is observed –the levels of burnout, stress, and dissatisfaction are below the theoretical mean of the scale, but relations are evaluated above the mean –improved, but not worsened during the teleworking mode. The only burnout subscale with higher levels is emotional exhaustion and worsened general health status is registred with scores just above the mean of the scale.

Table 2

Means, standard deviations, and correlations matrix

| Mean | Std | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| 1. WLB | 3.06 | 0,950 | |||||||||||

| 2. Perceived stress | 2.58 | 0,782 | 0.493** | ||||||||||

| 3. General health | 3.22 | 0,856 | –0.439** | –0.685** | |||||||||

| 4. Fears and anxiety | 2.86 | 0,964 | 0.335** | 0.565** | –0.478** | ||||||||

| 5. Emotional exhaustion | 3.55 | 1,51 | 0.552** | 0.624** | –0.550** | 0.497** | |||||||

| 6. Depersonalization | 1.97 | 1,13 | 0.287** | 0.363** | –0.298** | 0.251** | 0.540** | ||||||

| 7. Personal accomplishment | 2.79 | 1,14 | 0.148* | 0.374** | –0.387** | 0.220** | 0.202** | 0.338** | |||||

| 8. Psychosomatic symptoms | 2.59 | 0.940 | 0.519** | 0.729** | –0.642** | 0.604** | 0.728** | 0.443** | 0.252** | ||||

| 9. Satisfaction with profession | 2.16 | 0.882 | 0.275** | 0.450** | –0.396** | 0.338** | 0.521** | 0.451** | 0.402** | 0.438** | |||

| 10. Satisfaction with time | 2.66 | 1.07 | 0.457** | 0.499** | –0.427** | 0.395** | 0.658** | 0.419** | 0.270** | 0.548** | 0.582** | ||

| 11. Satisfaction with external factors | 2.67 | 0.925 | 0.275** | 0.355** | –0.313** | 0.352** | 0.456** | 0.360** | 0.147** | 0.429** | 0.607** | 0.645** | |

| 12. Relations with others | 3.12 | 0.501 | 0.394** | 0.360** | –0.350** | 0.278** | 0.344** | 0.324** | 0.198** | 0.347** | 0.255** | 0.255** | 0.254** |

**Correlation is significant at 0.01 level (2-tailed). *Correlation is significant at 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Effects of the individual variables of gender, age, length of service, academic area, academic profile and location of the university are insignificant both as individual and aggregate effect, thus not supporting H6. There are just partial differences in some of the subscales. The partial effects are as follows: The WLB of women is lower compared to that of men, however with low effect size (men M = 2.91; women M = 3.16; t = 3.413; p = 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.265999). Thirty-to-forty-year-old teachers have lower WLB compared to teachers aged 40–50 and 50–60 (mean difference –0.26446 and 0.25557; p < 0.05), however there is no difference compared to teachers below 30 and above 60 years of age. Regarding academic field, the only difference exhibited is that of teachers in medical sciences, who have lower WLB compared to teachers in social sciences (0.47766, p = 0.000), humanities (0.37725; p = 0.005), mathematics and ICT (0.42062; p = 0.014), physical (0.61194; p = 0.028) and technical sciences (0.36051; p = 0.010). Those who work in the country have lower WLB compared to teachers from the capital city of Sofia, with small effect size (M = 3.15 and 2.90 respectively; t = 3.301; p = 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.262359). Individual effect has just partial contribution to WLB.

Further, to test the study hypotheses, multiple regression analyses have been conducted (Table 3). It can be seen (Tables 2 and 3) that all our other hypotheses have been confirmed. WLB mean of university teachers is registered to be above the theoretical mean of the scale. Emotional exhaustion as a component of the burnout is also high. Perceived stress, fears, and anxiety, depersonalization and personal accomplishment are moderate. Positively, the relations with superiors and colleagues and personal relations are evaluated as improved during the pandemic. Women have worse WLB compared to men, with small effect size. Our results support findings of other researchers –about challenged WLB during COVID-19 pandemic of academic staff [54, 56, 57].

Table 3

Regression analysis

| Dependent Variable: (Standardised β) | |||||||||||

| WLB | WLB | WLB | WLB | WLB | WLB | WLB | WLB | WLB | WLB | WLB | |

| H1a | H1b | H1c | H1d | H2a | H2b | H2c | H3a | H3b | H3c | H4 | |

| Constructs | |||||||||||

| Perceived stress | 0.495*** | ||||||||||

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.558*** | ||||||||||

| Depersonalization | 0.266*** | ||||||||||

| Personal accomplishment | 0.139*** | ||||||||||

| Satisfaction with profession | 0.267*** | ||||||||||

| Satisfaction with time | 0.455*** | ||||||||||

| Satisfaction with external factors | 0.275*** | ||||||||||

| General health | –0.440*** | ||||||||||

| Fears and anxiety | 0.340*** | ||||||||||

| Psychosomatic symptoms | 0.519*** | ||||||||||

| Relations with others | 0.384*** | ||||||||||

| R2 | 0,495 | 0.558 | 0.266 | 0.139 | 0.267 | 0.455 | 0.275 | 0.440 | 0.340 | 0.519 | 0.348 |

| Total F | 229.530 | 318.455 | 53.580 | 13.971 | 54.346 | 184.061 | 57.660 | 169.282 | 92.016 | 260.919 | 122.178 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0,244 | 0.310 | 0.069 | 0.018 | 0.070 | 0.206 | 0.074 | 0.192 | 0.114 | 0.269 | 0.149 |

***p < 0.01. **p < 0.05. *p < 0.1.

Job satisfaction is moderate, depersonalization and personal accomplishment as components of burnout are also moderate, and so are the perceived stress and psychosomatic symptoms. University teachers, however, report challenged work-life balance, high emotional exhaustion and worsened physical and psychic health.

Table 4 reveals the explanatory power of WLB antecedents. Depersonalization, personal accomplishment, satisfaction with profession and satisfaction with external job-related factors do not explain a large percent of WLB variation.

Most predictive for the WLB are: the emotional exhaustion (explaining 31% of the variation in WLB), psychosomatic symptoms (explaining 27% of the variation in WLB), perceived stress (explaining 24% of the variation in WLB), satisfaction with time management (explaining 21% of the variation in WLB), general health (explaining 20% of the variation in WLB), relations with others (explaining 15% of the variation in WLB), and perceived fears and anxiety (explaining 11% of the variation in WLB).

4Discussion

The aim of the present research was to outline and study some of the main antecedents of university teachers’ work-life balance. Generally, it will be fair to conclude that the research findings support our suppositions and replicate reported results of other studies. Primarily, it should be noted that the satisfactory balance is influenced by a number of economic, social and occupational factors [10]. Furthermore, WLB is related to emotional exhaustion and satisfaction at work [29] as well as to job satisfaction in general [38–40]. The role of interpersonal relation quality has also been verified [50]. Finally, WLB has been affected by the long period of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic [54].

We acknowledge the limitations of the study in terms of the number of respondents and cross-sectional design but we view the results, related to this particular occupational group of teachers, as indicative and contributing to literature in several aspects, discussed herein below.

There are two most note-worthy findings of the present research. The first one is the confirmed significance of the positive relations with managers and colleagues for maintaining a satisfying WLB. The study results show that university teachers view their interpersonal relations –both in the academic and in the personal domains - as vital during the pandemic. The second important finding, which indicates the relevance of occupational factors, pinpoints emotional exhaustion and externalized psychosomatic factors as specific antecedents of university teachers’ WLB. This can be attributed to the pressure for working in remote mode for two years without having previous experience in teleworking. These two findings are of practical value in terms of providing future support to academic staff, as well as of outlining areas of more detailed future research.

Furthermore, the specific dynamics of university teachers’ WLB is highlighted by other findings of this study. Teachers engaged in lectures, seminars, or students’ practice exhibited quite similar WLB. Thus, the particular type of academic engagements itself does not impact the respondents’ WLB. The length of service has had no effect on WLB, either, which shows that when there is a completely new situation, length of service can neither facilitate, nor impede employees’ adaptation. Similar to other studies, our survey confirmed that job satisfaction, time management, overwork, technical support and guidelines, quality of communications, and perceived stress are among the antecedents of teachers’ WLB. More general issues, like pay and professional reputation, that are not dependant on personal and organizational efforts, seem to have less effect on WLB in the case of university teachers.

We hope that this initial summary is the first step towards research and insights for a more flexible and effective management of the work processes not only in a particular instance but in a continuous development at the level of HR administration. In summary, the results show that flexibility and accounting for universal needs of employees could allow the development of general frameworks with distinct indicators, which can be easily adapted by HR professionals in stable conditions and in crisis. Preparedness and stability of employees when they are facing external challenges and enduring changes are the foundations of their security and a prerequisite for maintaining work-life balance.

In conclusion, global crises and the related health, financial and general uncertainty, fast technological development, AI deployment in all professional and life domains put increasing pressure on professional and personal performance and reveal even more the importance of a good WLB. Digital acceleration and digitisation characterise the post-pandemic environment and further highlight the need for a more robust ICT infrastructure and continuous digital literacy upskilling. Last but not least, programmes for personal support are viewed as important for promotion of the WLB.

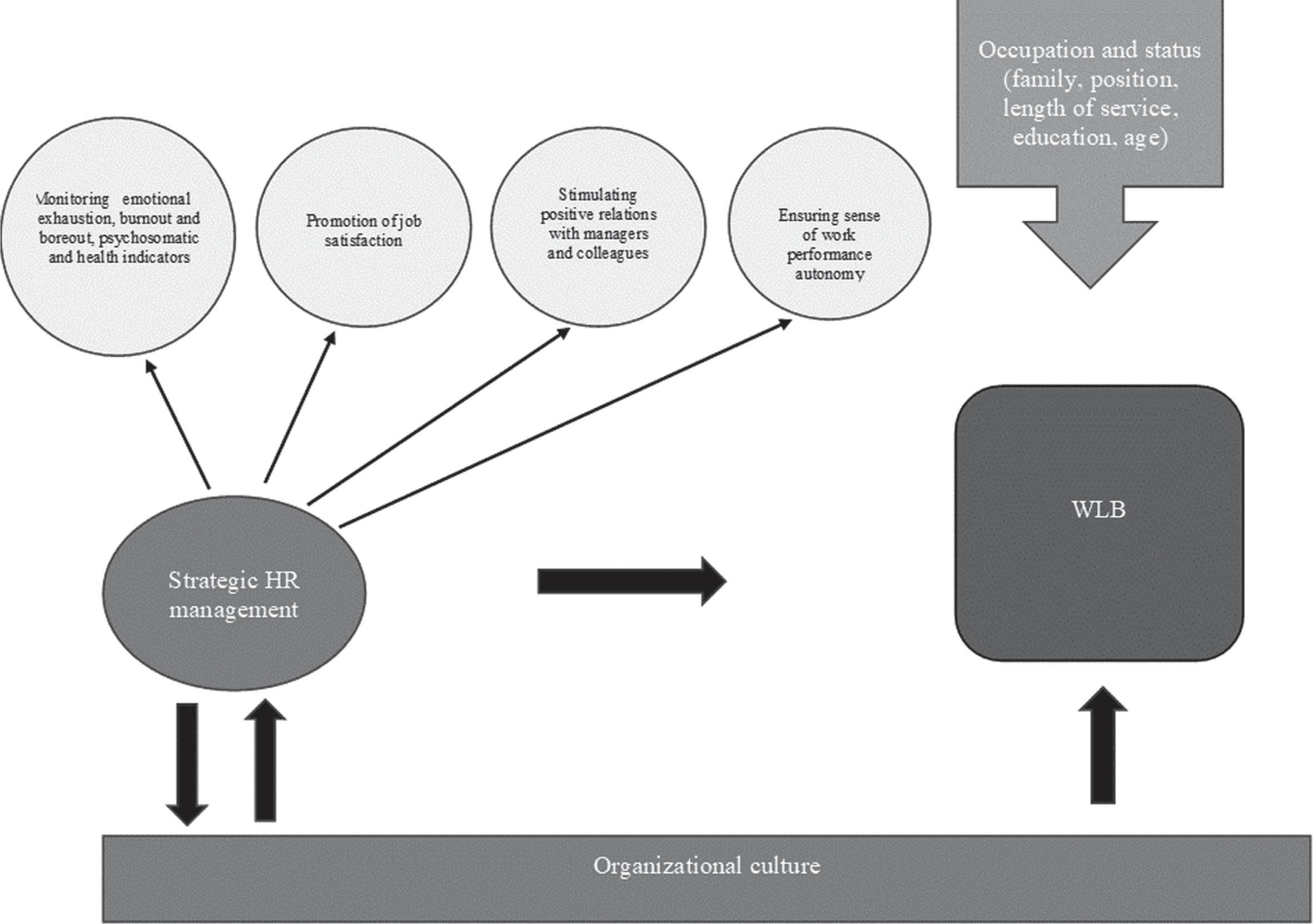

WLB is a complex construct, predicated by various factors. Future research can be based on the outlined explained variance in search for exhaustive groups of antecedents and their integration in a viable WLB model. The proposed WLB model, which integrates organizational culture, strategic HR management and personal variables, is outlined in Fig. 2. The acquis in the field of WLB research, apart from its vital importance for personal and organizational well-being, clearly indicates the place of organizational culture and HR management efforts in supporting employees and reveals the key role of the working environment. The inclusion of respondents from heterogeneous professions can validate this and contribute to the promotion of WLB, focusing on what organizations can provide and monitor.

Fig. 2

Suggested WLB model integrating organizational culture, strategic HR management and personal variables.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgements.

Author contributions

CONCEPTION: Margarita Bakracheva, Ekaterina Sofronieva, Martin Tsenov

METHODOLOGY: Margarita Bakracheva, Ekaterina Sofronieva, Martin Tsenov

DATA COLLECTION: Margarita Bakracheva, Ekaterina Sofronieva, Martin Tsenov

INTERPRETATION OR ANALYSIS OF DATA: Margarita Bakracheva, Ekaterina Sofronieva, Martin Tsenov

PREPARATION OF THE MANUSCRIPT: Margarita Bakracheva, Ekaterina Sofronieva, Martin Tsenov

REVISION FOR IMPORTANT INTELLECTUAL CONTENT: N/A

SUPERVISION: N/A

References

[1] | Totseva Y , Bakracheva M Pedagogical communication in the emergency situation. In: Pedagogical Communication: Verbal and Visual. Sofia: Faber; 2020, pp. 11–50. |

[2] | Bakracheva M , Zamfirov M , Kolarova T , Sofronieva E Living in pandemic times (COVID-19, 2020). Sofia, Colbis; 2020. |

[3] | Bakracheva M , Zamfirov M , Kolarova T , Sofronieva E Living in pandemic times (COVID-19, Wave 2). Sofia, Veda-Slovena; 2021. |

[4] | Zamfirov M , Bakracheva M , Kolarova T , Sofronieva E . Working and learning online during COVID-19. Education and Technologies. (2020) ;11: (1):91–8. DOI: 10.26883/2010.201.2212 |

[5] | Kirby LD , Qian W , Adiguzel Z , Afshar Jahanshahi A , Bakracheva M , Orejarena Ballestas MC , Cruz JFA , Dash A , Dias C , Ferreira MJ , Goosen JG , Kamble SV , Mihaylov NL , Pan F , Sofia R , Stallen M , Tamir M , van Dijk WW , Vittersø J , Smith CA . Appraisal and coping predict health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international approach. Int J Psychol. (2022) ;57: (1):49–62 DOI: 10.1002/ijop.12770. |

[6] | Bakracheva M , Zamfirov M , Kolarova T , Sofronieva E , Tsenov M M. University teachers’ adaptation to remote working. Sofia; 2022. |

[7] | Totseva Y , Bakracheva M The digital competences of kindergarten and school teachers in the context of the COVID pandemic crisis. In: Pedagogical Communication During Crises. Sofia: Faber; 2022, pp. 56–75. |

[8] | Bakracheva M , Totseva Y Pedagogical communication in times of crisis. In: Pedagogical Communication During Crises. Sofia: Faber; 2022a, pp. 11–55. |

[9] | Bakracheva M , Totseva Y . Burnout, boreout and mobbing experienced by teachers in kindergartens and schools in the conditions of COVID-19. Pedagogy. (2023) ;95: (2):190–204. DOI: 10.53656/ped2023-2.05. |

[10] | Sen C , Hooja H . Work-life balance: An overview. International Journal of Management and Social Sciences Research. (2018) ;7: (1):1–6. |

[11] | Grzywacz JG , Carlson DS . Conceptualizing work-family balance: Implications for practice and research. Advances in Developing Human Resources. (2007) ;9: (4):455–71. DOI: 10.1177/1523422307305487 |

[12] | Greenhaus J , Collins K , Shaw J . The relation between work-family balance and Quality of Life. Journal of Vocational Behavior. (2003) ;63: , 510–31. 10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00042-8. |

[13] | Voydanoff P . Toward a conceptualization of perceived work-family fit and balance: A demands and resources approach. Journal of Marriage and Family. (2005) ;67: 822–36. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00178.x. |

[14] | Greenhaus JH , Allen TD , Spector PE Health consequences of work-family conflict: The dark side of the work-family interface. In Perrewe PL, Ganster DC, (Eds.), Employee health, coping and methodologies Elsevier Science/JAI Press, 2006, pp. 61–98. DOI: 10.1016/S1479-3555(05)05002-X |

[15] | Anwar J , Hasnu SAF , Yousaf S . Work-life balance: What organizations should do to create balance? World Applied Sciences Journal. (2013) ;24: :1348–54. 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.24.10.2593. |

[16] | Grzywacz J , Bass B . Work, family, and mental health: Testing different models of work-family fit. Journal of Marriage and Family. (2003) ;65: :248–61. DOI: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00248.x |

[17] | Allen TD , Herst DE , Bruck CS , Sutton M . Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. (2000) ;5: :278–308. 10.1037//1076-8998.5.2.278 |

[18] | Halpern DF . How time-flexible work policies can reduce stress, improve Health, and Save Money. Stress and Health. (2005) ;21: (3):157–68. |

[19] | Mala WA How COVID-19 changes the HRM practices (Adapting One HR Strategy May Not Fit to All). SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020. DOI:10.2139/ssrn.3736719. |

[20] | Janvee G , Anil Kumar S , Ashish G Human capital in knowledge-based firms: Re-creating value post-pandemic. Human Systems Management. 2023;Pre-press:1-15. DOI:10.3233/HSM-220062. |

[21] | Stankevičiūte Z , Kunskaja S . Strengthening of work-life balance while working remotely in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Human Systems Management. (2022) ;41: (2):221–35. 10.3233/HSM-211511 |

[22] | Lina V . “New normal” at work in a post-COVID world: Work–life balance and labor markets. Policy and Society. (2022) ;41: (1):155–67. DOI: 10.1093/polsoc/puab011. |

[23] | Soto-Rubio A , et al. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. (2020) ;17: (21):7998. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217998 |

[24] | Allen TD , Herst DE , Bruck CS , Sutton M . Consequences associated with work to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. (2000) ;5: :278–308. |

[25] | Teles R , Valle A , Rodriguez S . Burnout among teachers in higher education: An empirical study of higher education institutions in portugal. International Journal of Management Science and Business Administration. (2022) ;6: (5):7–15. |

[26] | Weißenfels M , Klopp E , Perels F . Changes in teacher burnout and self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic: Interrelations and e-learning variables related to change. Front Educ.92. (2022) ;6: :736992. DOI: 10.3389/feduc.2021.736992. |

[27] | Forte T , Santinha G , Carvalho SA . The COVID-19 pandemic strain: Teleworking and health behavior changes in the portuguese context. Healthcare (Basel). (2021) ;9: (9):1151. DOI: 10.3390/healthcare9091151. |

[28] | Chan XW , Shang S , Brough P , Wilkinson A , Lu C Work, life, and COVID-19: A rapid review and practical recommendations for the post-pandemic workplace. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources. 2022.10.1111/1744-7941.12355. |

[29] | Sirgy M , Lee DJ . Work-life balance: An integrative review. Applied Research Quality Life. (2018) ;13: , 229–54. |

[30] | Čopková R . The relationship between burnout syndrome and boreout syndrome of secondary school teachers during COVID-19. Journal of Pedagogical Research. (2021) ;5: (2):138–51. DOI: 10.33902/JPR.2021269824. |

[31] | Minihan E , Adamis D , Dunleavy M , Martin A , Gavin B , McNicholas F . COVID-19 related occupational stress in teachers in Ireland. International Journal of Educational Research Open. (2022) ;3: :100114. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100114. |

[32] | Edwards JR , Rothbard NP . Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Academy of Management Review. (2000) ;25: (1):178–99. |

[33] | Kelly M , Soles R , Garcia E , Kundu I . Job stress, burnout, work-life balance, well-being, and job satisfaction among pathology residents and fellows. American Society for Clinical Pathology. (2020) ;XX: 1–21. |

[34] | Gregory A , Milner S . Editorial: Work–life balance: A matter of choice? Gender, Work and Organization. (2009) ;16: (1):2–13. |

[35] | Kabir MN , Parvin MM . Factors affecting employee job satisfaction of pharmaceutical sector. Australian Journal Of Business And Management Research. (2011) ;1: (9):113–23. |

[36] | Auh S , Menguc B , Spyropoulou S , Wang F . Service employee burnout and engagement: The moderating role of power distance orientation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. (2015) ;44: (6):726–45. DOI: 10.1007/s11747-015-0463-4. |

[37] | Swathi M . Work-life balance during covid-19 pandemic and remote work. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Reseach. (2022) ;11: (4) DOI: 2022/11.01.67 |

[38] | Park S , Jae MM . Determinants of teleworkers’ job performance in the pre-COVID-19 period: Testing the mediation effect of the organisational impact of telework. Journal of General Management. (2022) :03063070221116510. DOI:10.1177/03063070221116510 |

[39] | De Vincenzi C , Pansini M , Ferrara B , Buonomo I , Benevene P . Consequences of COVID-19 on employees in remote working: Challenges, risks and opportunities an evidence-based literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) ;19: (18):11672. DOI:10.3390/ijerph191811672. |

[40] | Cheng SC , Kao YH . The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on job satisfaction: A mediated moderation model using job stress and organisational resilience in the hotel industry of Taiwan. Heliyon. (2022) ;8: (3):e09134 DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09134. |

[41] | Fahey T , Whelan CT , Nolan B Monitoring quality of life in Europe (report). 2003. |

[42] | Barnett RC , Gareis KC “Role theory perspectives on work and family”, in PittCatsouphes M, Kossek EE, Sweet S. (Eds), The Work and Family Handbook: MultiDisciplinary Perspectives, Methods, and Approaches, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. 2006, pp. 209–21. |

[43] | Brooks SK , Webster RK , Smith LE , Woodland L , Wessely S , Greenberg N , Rubin GJ . The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. (2020) ;395: (10227):912–20. DOI: 10.0016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. |

[44] | González-Sanguino C , Ausín B , Castellanos MÁ , Saiz J , López-Gómez A , Ugidos C , Muñoz M . Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.. (2020) ;87: :172–6. doi: 10.0016/j.bbi.2020.05.040. |

[45] | Wang C , Pan R , Wan X , Tan Y , Xu L , McIntyre RS , Choo FN , Tran B , Ho R , Sharma VK , Ho C . A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. (2020) ;87: :40–8. doi: 10.0016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. |

[46] | Kirby L , Qian W , Adiguzel Z , Bakracheva M , Ballestas MCO , Cruz J , Dash A , Ferreria MJ , Goosen JG , Jahanshahi AA , Kamble SV , Mihaylov N , Pan F , Sofia R , Stallen M , Tamir M , Vitterso J , van Dijk WW , Smith SA Appraisal and coping predict health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international approach. International Journal of Psychology. 2021. DOI: 10,0002/ijo02770. |

[47] | Ruiz MC , Devonport TJ , Chen-Wilson CH , Nicholls W , Cagas JY , Montalvo JF , Choi Y , Robazza C . A cross-cultural exploratory study of health behaviours and wellbeing during Covid-19. Frontiers in Psychology. (2021) ;11: :608216. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608216. |

[48] | Elbaz S , Richards JB , Provost Savard Y Teleworking and work–life balance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne. 2022. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1037/cap0000330 |

[49] | Reijseger G , Wilmar B , Schaufeli MCW , Peeters TW , Taris IB , Ouweneel E , Watching the paint dry at work: Psychometric examination of the Dutch Boredom Scale. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. (2013) ;26: (5):508–25. DOI: 10.1080/10615806.2012.720676 |

[50] | Sand G , Miyazaki AD . The impact of social support on salesperson burnout components. Psychology and Marketing. (2000) ;17: (1):13–26. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200001)17:1<13::AID-MAR2>3.0.CO;2-S |

[51] | Azizi MR , Atlasi R , Ziapour A , Abbas J , Naemi R . Innovative human resource management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review approach. Heliyon. (2021) ;7: (6):e07233. DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07233. |

[52] | Parker S , Knight C , Keller A . Remote managers are having trust issues. Harvard Business Review. (2020) 30. |

[53] | Dd A . Impact of working from home on work life balance during Covid-19: Evidence from IT sector. 2022.10.13140/RG.2.2.11457.43362. |

[54] | Survey Report on Faculty and Staff COVID-19 Work-Life Balance Survey at Northern Illinois University https://www.niu.edu/president/pdf/covid-19-work-lifebalance-survey-report.pdf |

[55] | Bukowska U , Małgorzata T , Sylwia W . The workplace and work-life balance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business and Psychology. (2021) ;33: (6):727–40. DOI: 10.17951/h.2021.55.2.19-32. |

[56] | Aliyyah RR , Rachmadtullah R , Samsudin A , Syaodih E , Nurtanto M , Tambunan ARS . The perceptions of primary school teachers of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic period: A case study in Indonesia. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies. (2020) ;7: (2):90–109. |

[57] | Flores MA , Gago M Teacher education in times of COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal: National, institutional and pedagogical responses. Journal of Education for Teaching. 2020. DOI: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1799709 |

[58] | Bozkurt A , Sharma R . Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to CoronaVirus pandemic. (2020) 15: :i–vi. 10.5281/zenodo.3778083. |

[59] | Hodges C , Moore S , Lockee B , Trust T , Bond M The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. 2020. Available from: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning |

[60] | Bulinska-Stangrecka H , Bagieńska A , Iddagoda A Worklife balance during COVID-19 pandemic and remote work: A systematic literature review. 2021. DOI: 10.2478/9788366675391-009. |

[61] | Lonska J , Mietule I , Litavniece L , Arbidane I , Vanadzins I , Matisane L , Paegle L . Work–life balance of the employed population during the emergency situation of COVID-19 in Latvia. Front Psychol. (2021) ;12: 682459. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682459. |

[62] | Jaiswal A , Arun CJ . Working from home during COVID-19 and its impact on Indian employees’ stress and creativity. Asian Bus Manage. (2022) :1–25. DOI: 10.1057/s41291-022-00202-5. |

[63] | Cohen S , Williamson G Perceived Stress in a Probability Sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988, pp. 31–67. |

[64] | Hays RD , Bjorner JB , Revicki DA , Spritzer KL , Cella D . Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. (2009) ;18: (7):873–80. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. |

[65] | Maslach C , Jackson SE , Leiter MP MBI: Maslach burnout inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. |

[66] | Burnout Self-Test Adapted from MindTools: Essential skills for an excellent career. Burnout Self-Test. Available from:https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newTCS08.htm [Accessed 5 January 2022]. |

[67] | Spector PE . Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: Development of the Job Satisfaction Survey. Am J Community Psychol. (1985) ;13: (6):693–713. DOI:10.1007/BF00929796. |

[68] | Job Satisfaction Survey. Available from:https://scales.arabpsychology.com/s/job-satisfaction-survey/ [Accessed 5 January 2022]. |

[69] | Teacher Job Satisfaction Scale. Available from:https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/publications/timss/2015-methods/pdf/T15_MP_Chap15_AppxB_Teacher_Job_Satisfaction_EighthGrade.pdf |