Contextual barriers to implementing pandemic HRM in Indian manufacturing SMEs: A comprehensive analysis

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Existing literature lacks in-depth analyses and identification of barriers to implementing HR practices that affect employee health and well-being, especially during and after the pandemic. Moreover, existing studies primarily focus on large organizations with generic HR contexts. Therefore, this research contributes by evaluating the contextual relationship between barriers to implementing pandemic Human Resource Management (HRM) practices in Indian manufacturing SMEs.

OBJECTIVE:

The post-pandemic landscape has necessitated a reevaluation of Human Resource (HR) practices, particularly in terms of employee health and well-being while balancing organizational performance goals. This study seeks to identify and evaluate the significant barriers hindering the implementation of re-designed HR policies, focusing on Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) in the manufacturing sector in developing countries during and after the pandemic transition.

METHODS:

The study initially identified ten barriers through a thorough literature review, which was then validated by experts. Subsequently, the interrelationships among these barriers were explored, and their structural hierarchy was established using the Total Interpretive Structural Modelling (TISM) approach. Additionally, a MICMAC (Matriced Impact Croises Multiplication Applique) analysis was performed to assess the driving-dependence power of each barrier.

RESULTS:

“Manager’s resistance to change” and “employee’s resistance to change” were found to be highly dependent on the other identified barriers. Among these, “lack of skilled managers at affordable costs” and “implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices” emerged as the most critical barriers, with the potential to impact all other barriers in the implementation of re-designed policies.

CONCLUSIONS:

The study helps owners of manufacturing SMEs and managers to understand the significant barriers to implementing HR policies, particularly in frequent pandemic situations for enhancing employees’ health and well-being while ensuring organizational performance. The planned framework might make it easier for practitioners and decision-makers to comprehend how the various implementation barriers relate to one another. The study’s focus on Indian manufacturing SMEs limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts. Reliance on expert opinions introduces bias, and further validation through empirical research is needed.

Nagamani Subramanian is an Assistant Professor at REVA Business School, REVA University, Bengaluru. She holds a Ph.D. in Management from Amrita School of Business, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Coimbatore, and a Master’s degree in Business Administration from Bharathiyar University, India. She has also qualified in UGC-NET in both Management and Human Resource Management. Additionally, she was awarded the NFOBC fellowship by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, which supported her research efforts. Her field of study is Sustainable HRM, with research interests that include Agile HRM and Lean-Sustainable HRM.

Suresh M. is a Professor at Amrita School of Business, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Coimbatore, India. He holds a PhD in Project Management from the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, India, and a Master’s in Industrial Engineering from PSG College of Technology, Coimbatore, India. His research interests include issues related to lean and agile operations and performance management. He has authored several papers in Operations Management and currently working on lean and agile Healthcare Operations Management. He is also a member of the International Society on Multiple Criteria Decision Making.

Dr. Bhavin Shah holds a Ph.D (Fellow) and Masters (PGDIE) degree in Industrial Engineering from the National Institute of Industrial Engineering (NITIE), Mumbai, India. He is a Bachelor in Computer Engineering from Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat. Bhavin has research and teaching experience of more than 15 years in interdisciplinary domains such as Lean thinking in warehousing and logistics, Information Systems and Data Analytics applications to Supply Chain; IT-enabled operations management, Optimization using computer algorithms and, Simulation and Modelling of Operations-Marketing Interfaces. His research has featured in internationally acknowledged Journals and Conferences. He is on-board of multiple journals in the capacity of editorial member and reviewer.

1Introduction

The pandemic transformation has prompted organizations of all sizes to reassess their operational strategies and swiftly adapt to new work policies. This global crisis has underscored the need for businesses to revamp their long-term strategies to remain competitive in an evolving market while ensuring the well-being of their employees [1]. The sudden shift to remote work has altered traditional work environments and conditions, emphasizing the importance of technology, knowledge-based work, reduced physical interactions, and employee well-being [2]. However, existing Human Resource Management (HRM) practices were predominantly designed for on-site work, posing challenges for remote work arrangements, especially in sectors like manufacturing [3–5]. As organizations navigate these changes, there is a growing recognition among HRM practitioners of the need to align HR policies with digitalization trends to enhance employees’ technological skills and organizational competitiveness [6, 7].

While existing literature has extensively studied HRM practices, there remains a gap in understanding the challenges and barriers faced in implementing HRM practices, particularly in manufacturing settings, and more so in the context of post-pandemic work policies [8, 9]. The dearth of research in this area is notable, especially regarding Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the manufacturing sector, where dedicated HR managers are rare, and HR functions are often handled by owners or managers with limited resources [10]. This study aims to address this gap by focusing on Indian manufacturing SMEs, which play a crucial role in the country’s economy, particularly in reducing social inequalities and unemployment [11]. By identifying barriers to implementing re-designed HRM practices in Indian SMEs, this study seeks to contribute to the understanding of HRM challenges in the post-pandemic era, particularly in developing countries like India.

Despite efforts by developing-country researchers to establish the HRM framework [11], their contributions are minimal in terms of identifying challenges and barriers to implementing HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. In developing countries like India, SMEs are considered the backbone of the country’s economy, and they have been a determining sector in eradicating social inequalities, and unemployment, and improving economies. Further, the literature body state proves that there is a dearth of studies analyzing the redesigned HRM hurdles in the post-pandemic Indian scenario. As a result of this discussion, this current study is intended to focus on manufacturing SMEs in India. Also, it intends to identify the barriers to the implementation of newer HRM practices in Indian SMEs and aims to accomplish identified literature gaps with the following research objectives:

i) To identify the barriers to implementing re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic era in manufacturing SMEs with the context of employee well-being.

ii) To establish hierarchical relationships among each barrier and to analyze the driving and dependence power of the barriers related to re-designed HRM practices.

To address our research objectives, Total Interpretive Structural Modelling (TISM) is considered the most appropriate methodology. The robustness of TISM lies in its ability to uncover intricate relationships among variables and structure their interdependence [12], aligning precisely with our objective to understand these relationships and their hierarchical structuring. TISM’s holistic approach ensures a comprehensive analysis of the multidimensional aspects of Lean HRM implementation, while its prior empirical success in analogous contexts, as evidenced by previous studies [13, 14], further reinforces the appropriateness of this methodology for our specific research objectives.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review focusing on the barriers to implementing re-designed HRM across different contexts, with a specific emphasis on the Indian manufacturing sector. Section 3 details the TISM methodology and the development of the model, highlighting the intricate relationships among various factors. In Section 4, the research findings are unfolded, while Section 5 discusses how these results contribute to existing theories. Section 6 outlines the managerial and policymaking implications of the findings, providing practical insights. Section 7 discusses policy recommendations, and Section 8 encapsulates the study’s conclusions, exploring the research’s limitations and charting directions for future investigations.

2.Literature review

2.1Theoretical background

The study adopts the Resource-Based View (RBV) [15, 16] theory to identify the barriers to implementing re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic era, specifically focusing on SMEs within the context of employee well-being. RBV posits that organizations must effectively manage their resources and capabilities to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. In the context of HRM practices in SMEs post-pandemic, RBV provides a framework to understand how the lack of certain resources, such as skilled HR managers, knowledge, infrastructure, and financial resources, can hinder the successful implementation of re-designed HRM practices. This perspective sheds light on how organizations can leverage their resources and capabilities to overcome these challenges and drive successful post-pandemic HRM policy re-design. Additionally, RBV helps to elucidate how organizational factors, including culture, leadership quality, and agility, can influence employee and manager attitudes toward change, thereby impacting the implementation of new HRM practices and ultimately, employee well-being [17, 18].

In our examination of barriers to implementing re-designed HRM practices in post-pandemic manufacturing SMEs, with a focus on employees’ well-being, we underscore our commitment to theoretical rigor by strategically incorporating the Resource-Based View (RBV) theory. Guided by [19] and [20], these foundational frameworks inform our analysis by emphasizing the value, rarity, and difficulty of imitating attributes crucial for sustaining a competitive advantage. To enhance the integration of RBV, each identified barrier is intricately linked to these foundational principles. We establish explicit connections between the theoretical foundations of our analysis and the core tenets of RBV, ensuring that these principles underpin our understanding of the barriers to re-designed HRM practices. Furthermore, recognizing the need for robust theory development to advance knowledge in the field, our adoption of TISM is not merely a methodological choice but a deliberate strategy to facilitate theory development [21–24]. TISM, with its unique ability to comprehensively elucidate causal relationships among factors [25] serves as a powerful tool in our effort to advance theoretical understanding of the implementation of re-designed HRM practices in post-pandemic manufacturing SMEs.

2.2Challenges and adaptations in HRM practices amidst pandemic

The pandemic has posed numerous obstacles to organizational performance regardless of their ownership and operating nature and also heightened employees’ mental stress. Further, the uncertain crisis leads to alterations in the workplace, working conditions and workloads, fewer job options for employees, wage cuts, feelings of insecurity, and a decline in well-being [26, 38]. Further, a wide range of changes in HRM techniques occurred as businesses altered operating procedures in response to this crisis [1, 27]. The theoretical basis for emphasizing the impact of HRM in normal times will also support effectively connecting with employees even in the scenario of a pandemic. The inherent role of HR managers for organizations in times of disaster and post-pandemic [16, 28] and their responsibility concerning employees [39] are well-researched in literature. These theories suggest the importance of HRM on complementary sequences and from a systemic perspective (at the macro level), but they do not address the specific actions of HR managers in individual scenarios (at the micro level), especially in the post-pandemic era. Therefore, the subsequent section explores the challenges of implementing re-designed HRM practices in this post-pandemic era.

Earlier, HRM practices were developed to shape the performance, attitude, and behavior of employees in the workplace [40], however, its significance shifted during the outbreak of coronavirus with travel restrictions and social distancing at workplaces. The HR department has a greater obligation to adopt digitalization allowing employees to update their skills [7, 29]. Subsequently, HR needs to understand the feelings of employees and respond proactively in terms of protecting employees’ health and well-being [30, 3, 38]. Also, existing literature offers various recommendations to firms’ HR managers concerning employees and work management: showing compassion and empathy [31, 41]; perceived organizational support [32, 42]; continuous interaction with employees [14]; training on technology, updates in terms of new developments, changes in procedures [43, 44] giving employees trust and hope to enhance their well-being [33, 42]; creating a caring culture; providing an atmosphere of coordination and collaboration [34, 2]. However, these traditional HRM practices are meant for managing employees at the workplace, not at home (a “Work from Home” atmosphere) [3]. Therefore, this gap motivated the researchers to explore several barriers and discover their potential in improving HRM implementation in manufacturing SMEs’ post-pandemic environment.

Several scholars [35–37] have looked at several HRM aspects that can help an organization achieve improved organizational performance for long-term sustainability. However, identifying HRM barriers is difficult as the literature body lacks it under given situations. So, initially, a thorough literature analysis was conducted to identify a set of barriers to the implementation of a re-designed HRM. These barriers were then given to experts for finalization. These barriers are supported by literature as follows.

2.3Barriers to re-designed HRM

In this section, we have identified ten barriers that influence the implementation of re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. These barriers, detailed in Table 1, will be further discussed in subsequent sections. Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) has gained attention in human resource research for its ability to provide a comprehensive understanding of how systems work and how different factors interact [45–47]. However, [48] and [25] have highlighted limitations in ISM, prompting us to explore alternative approaches. To address these limitations and contribute to existing literature, we propose using Total Interpretive Structural Modelling (TISM) as an extension [21, 25]. In integrating insights from the Resource-Based View (RBV), we strengthen our theoretical foundation. The application of TISM to construct theoretical models related to re-designed HRM is underrepresented in current literature. Therefore, our decision to use the TISM model, informed by RBV theory, aims to fill this research gap and provide a nuanced perspective on factors related to re-designed HRM in the post-pandemic environment.

Table 1

Barriers influencing re-designed HRM implementation

| S.No. | Barriers | Description | References |

| 1 | Lack of knowledge and skills in handling online tools/techniques (B1) | Lack of knowledge and skills in handling online tools/techniques refers to the absence or inadequacy of expertise among employees in using digital tools and technologies necessary for implementing re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. | [49]; [50]; [107]; [44]; Expert opinion |

| 2 | Lack of skilled HR managers at affordable costs (B2) | The lack of skilled HR managers at affordable costs refers to the challenge faced by organizations in hiring or retaining HR professionals with the necessary expertise and experience at a cost that is manageable for the organization. This challenge hinders the effective implementation of re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. | [51]; [52]; [58]; Expert opinion |

| 3 | Implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices (B3) | Implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices refer to the costs associated with adopting and implementing new HRM practices that are necessary in the post-pandemic environment. These expenses include costs related to training, technology, and infrastructure required for the successful implementation of re-designed HRM practices. | [53]; [54]; [1]; [108]; Expert opinion |

| 4 | Lack of culture and favorable work environment (B4) | Lack of culture and favorable work environment refers to the absence of a supportive organizational culture and conducive work environment that encourages the successful implementation of re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. | [55]; [56]; [91]; [57]; Expert opinion |

| 5 | Lack of agility, creativity, and flexibility (B5) | Lack of agility, creativity, and flexibility refers to the organization’s inability to adapt quickly, think innovatively, and adjust to changing circumstances when implementing re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. | [59]; [60]; [106]; [63]; Expert opinion |

| 6 | Lack of Managers/owner commitment and poor leadership quality (B6) | Lack of Managers/owner support and poor leadership quality refers to insufficient backing and ineffective leadership from managers and owners, which hinders the successful implementation of re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. | [61]; [62]; [7]; [40], Expert opinion |

| 7 | Managers’ resistance (B7) | Manager’s resistance to change refers to the reluctance or opposition shown by managers towards adopting and implementing re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. | [64]; [65]; [95]; Expert opinion |

| 8 | Employees’ resistance (B8) | Employee’s resistance to change refers to the unwillingness or opposition displayed by employees towards adopting and implementing re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. | [66]; [67]; [110]; [107]; Expert opinion |

| 9 | Lack of HR infrastructure (B9) | Lack of HRM infrastructure refers to the absence or inadequacy of the necessary systems, processes, and technology required for implementing re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment. | [68]; [69], [112]; Expert opinion |

| 10 | Lack of comprehensive plan to implement new normal HRM practices (B10) | The lack of a comprehensive plan to implement new normal HRM practices refers to the absence of a detailed and thorough strategy for adopting and integrating new HRM practices that are suitable for the post-pandemic environment. | [70]; [71]; [111]; Expert opinion |

2.3.1Lack of knowledge and skills in handling online tools/techniques

The protective measures of the pandemic have forced organizations to intensify digital transition for business continuity. Innovation, social media, and internet use have been pivotal in this transition, enabling effective work performance and HR functions such as resource recruitment, selection, and performance management [72, 75]. The pandemic and technology have underscored the importance of allowing employees to work from home, necessitating them to acquire relevant technical knowledge and skills to ensure their employability in remote work settings. However, existing HR practices may not fully consider the nuances of online arrangements and the desired level of automation in manufacturing SMEs’ workplaces [73, 76], highlighting the need for further integration of innovation, social media, and internet use into HRM practices for successful post-pandemic adaptation.

2.3.2Lack of skilled HR managers at affordable costs

The lack of skilled HR managers at affordable costs presents a significant challenge for manufacturing SMEs, particularly in the current scenario where HR managers play a crucial role in keeping employees engaged, motivated, productive, and connected. HR managers are essential for supporting organizations and driving workplace modifications through forward-thinking HR strategies [74; 106]. They are also required to be proficient in the digital transition of HR activities and collaborate closely to implement various HRM functions such as recruitment, workforce development, compensation policies, and employee relations management [80, 81]. However, the utilization of HRM practices is comparatively lower in manufacturing SMEs than in larger organizations due to the lack of competent HR expertise and the unaffordability of hiring trained HR experts on a full-time basis [82, 57]. As a result, HRM practices often fall under the responsibility of managers/owners in SMEs [83]. In the context of the pandemic, HR managers of manufacturing SMEs play a crucial role in addressing challenges such as high employee turnover and fostering innovation for business survival. Therefore, the absence of skilled HR managers significantly impacts the implementation of effective HRM practices in manufacturing SMEs.

2.3.3Implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices

The implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices pose a significant challenge for SMEs, particularly due to their limited resources in terms of manpower, money, and materials [84]. SMEs often have less structured and planned HRM practices compared to larger organizations [85, 89]. Traditional HRM practices incurred various human resources costs, including high employee turnover expenses and training costs for skill development. However, the pandemic has accelerated the digital transformation of HRM practices, with recruitment, selection, and training being conducted through technology. Despite the benefits of digitalization, the cost of utilizing social networking sites for HRM activities in SMEs is high [86, 96]. Additionally, there are limitations in financial resources and budgeting, which hinder the effective implementation of digital HRM practices in SMEs. The significant expenses associated with implementing new digital technologies for HRM practices often influence HR managers’ decisions to avoid budget constraints [87,88], thereby restricting SMEs from adopting new normal HRM practices.

2.3.4Lack of culture and favorable work environment

The lack of a culture and favourable work environment poses a significant challenge to the effective implementation of HRM practices. The adoption of HRM practices is often influenced by managers’ beliefs and conventions regarding tasks and workforces [90]. Therefore, creating a supportive organizational culture is essential for the successful enactment of HRM practices. Managers play a crucial role in making employees aware of the organization’s objectives and vision for anticipated changes, which is achieved through a suitable organizational culture [91]. A favourable work environment is also crucial, as it allows both managers and employees to coordinate and share their work, leading to a win–win situation. However, the pandemic has disrupted these cultural linkages, and current HR practices are lacking in this favorable work environment.

2.3.5Lack of agility, creativity, and flexibility

Organizations face a significant barrier in implementing HRM practices due to their lack of agility, creativity, and flexibility, particularly during crises [92]. The ability to engage the workforce, manage performance, mentor and motivate employees, recruit and select, and ensure employee well-being is hindered when organizations are not agile, creative, or flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances [93]. With the current socioeconomic crisis prompting a shift to virtual workplaces, it is essential for organizations, especially SMEs, to enhance their agility, creativity, and flexibility to successfully implement HRM practices in such challenging situations.

2.3.6Lack of managers/owner commitment and poor leadership quality

Managers and owners play a crucial role in introducing and executing new HRM policies, with their support and commitment being key factors in the success of HRM transition processes [39, 94]. Effective implementation of HRM practices relies heavily on involving HR managers in strategic planning and investing in human resources [95]. A true digital HRM transition requires strong leadership, not only in terms of knowledgeable support but also active involvement in the process [7]. However, many owner-managers of SMEs lack thoughtful administrative know-how, making SMEs strategically vulnerable due to a lack of quality leadership traits. Therefore, SMES must prioritize having quality leaders at the helm to enhance the skills and knowledge of their employees.

2.3.7Managers’ resistance

The pandemic has underscored the importance of business continuity, prompting organizations to adapt their processes and initiate transformational changes with new business models [82]. This transformational change involves restructuring organizational structures, work procedures, and even culture [97]. The pandemic has disrupted traditional workflows and shifted roles and responsibilities, necessitating changes in working methods, employee interactions, and digital transitions. Research indicates that top managers play a crucial role in change efforts, primarily by influencing and encouraging employees through providing vital information and opportunities for involvement, thereby shaping employees’ behavior toward change [98, 99]. However, if managers are resistant to change, they are less likely to actively facilitate change. Therefore, SMEs need to understand the reasons behind managers’ resistance to change and take proactive measures to mitigate its detrimental effects, such as lack of clarity, pressure, challenges in learning new things, and uncertainty about the change [100].

2.3.8Employees’ resistance

Existing literature emphasizes that employees’ resistance to change is a significant issue when implementing new changes [101]. Change initiatives within an organization can evoke emotional responses in employees, impacting their attitudes towards change. Employees’ determination, confidence, and belief in organizational change influence their support behavior and efforts towards change [99]. Often, employees misinterpret or overlook the implications of change on their specific roles within the organization. Employee resistance to change is not necessarily due to disagreement but can stem from a lack of knowledge and skills or ineffective communication about the change [102]. The pandemic has further highlighted the need for employees to acquire technological skills for remote work, which may lead to fears about their ability to adapt or misunderstandings due to lack of communication [103]. Therefore, SME owner-managers need to motivate and communicate with employees effectively, ensuring that they believe in, understand, and are committed to change for successful HRM implementation.

2.3.9Lack of HR infrastructure

HR infrastructure encompasses HR policies, procedures, and practices considered best in the industry, as well as processes for accessing management and HR support, and systems for recruitment, selection, training, compensation, and reward and recognition [104]. Particularly during the pandemic, HR infrastructure is crucial and should align with the organization’s mission, values, strategies, and objectives, especially regarding employee safety. It is recommended that HRM practices be planned to support a safe workplace by adhering to COVID-19 protocols and ensuring employee safety [80]. The presence of HR infrastructure enables organizations to implement HRM effectively, while its absence can lead to confusion regarding employee safety and well-being.

2.3.10Lack of comprehensive plan to implement new normal HRM practices

During the pandemic, many organizations are striving to restore their full functionality. However, implementing new normal HRM practices can be ineffective if not properly designed and managed [105]. Therefore, organizations are urged to integrate comprehensive pandemic planning considerations into their resilience management strategies for business continuity. Successful implementation of HRM practices hinges on coordinated and comprehensive planning, especially regarding the formulation of HR policies and systems.

3Methodology

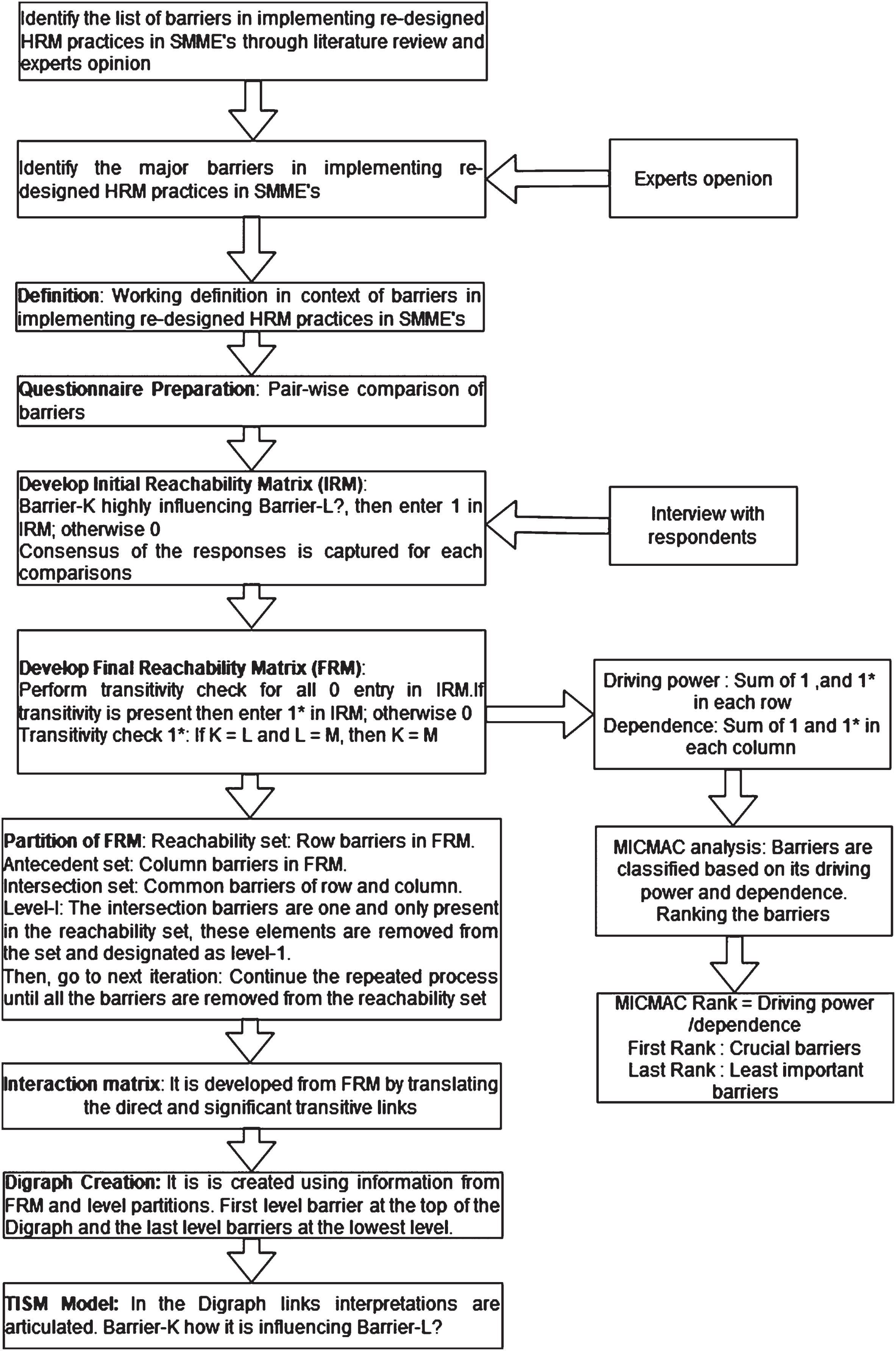

This study aims to investigate the barriers influencing the implementation of re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic environment in Indian manufacturing SMEs. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed research approach, which consists of three main phases with subsections. The initial phase focuses on identifying the barriers influencing re-designed HRM implementation. Barriers were systematically gathered using reputable databases such as Scopus, EBSCO, and Google Scholar. The second phase employs the TISM technique to analyze the relationships between these identified barriers. The third phase involves categorizing these barriers using the MICMAC technique. Experts with expertise in human resource management were selected for their relevant knowledge. To compile a distinct list of Indian manufacturing SMEs, various sources, including the Manufacturers’ Association and the Manufacturers’ Expo list, were utilized. The survey included thirty professionals with a minimum of three years of experience, randomly selected from this list. The selection of TISM as the preferred methodology was driven by its ability to establish a hierarchy and interconnections among these factors, providing a comprehensive understanding. The subsequent section delves into the applicability and suitability of TISM for this specific study.

Fig. 1

The flow of the TISM approach for barriers in implementing re-designed HRM practices.

TISM is an approach utilized to comprehend the interrelatedness between the barriers that influence HRM practice in SMEs. Various investigators have utilized the TISM methodology to evaluate the relationships between factors in the manufacturing and service industries [113, 114]. This paper employs the TISM approach for evaluating the interrelations between the HRM barriers in SMEs. To address our two study objectives, a method based on Total Interpretive Structural Modelling (TISM) could be investigated. To create a redesigned HRM framework, our research uses qualitative interpretive logic. By presenting interlinks, TISM is one of the methodologies that aim to solve the three fundamental questions of theory development, “what,” “why,” and “how.” [105, 41]. As a result, the TISM technique has gained traction as a viable alternative. The flow of the TISM approach is shown in Fig. 1 [115, 116].

Literature suggests the following steps for the effective implementation of the TISM model: [117].

• Identification of the barriers: The initial step in implementing redesigned HRM practices in SMEs in the post-pandemic era was to identify the barriers. This was discovered through a survey of the literature and expert opinion. Table 2 lists the major barriers that have been discovered.

• Establish interconnectedness between barriers: Contextual linkages between the barriers must be built to arrive at the Initial Reachability Matrix (IRM). Owners, general managers, HR managers, managers, manager in-charges, supervisors, and floor in-charges from various SMEs in India participated in this survey as respondents. To enhance SME’s revised HRM practices in the post-pandemic age, respondents were chosen based on their knowledge and capacity for observation. Table 3 has a list of the IRM.

• Interpretation of the relationship between barriers: This stage in the TISM technique aims to understand how barrier K impacts barrier L by answering the question “how”.

• Developing the final reachability matrix (FRM) after checking for transitivity: Before arriving at the FRM, a transitivity check is required. In the IRM, all items with the value “0” must be transitively checked [118]. The FRM is displayed in Table 4.

• Partition of the barriers from FRM into levels: The partition reachability matrix has arrived from FRM [56].

• Designing the interaction matrix: Direct and substantial transitive relationships are used to generate the interaction matrix [60]. Table 5 depicts the condition.

• Creating the digraph and the TISM model: The digraph, also known as a directed graph, is created using data from the interaction matrix and level partitions [114]. First-level barriers are those at the top of the model, and subsequent levels are mentioned in ascending order in the digraph. The digraph and the interpretive interaction matrix are also used to create the TISM model. The TISM model is depicted in Fig. 2, and the justification for the direct and substantial transitive relationships is discussed in Section 4.1.

Table 2

Identified barriers in implementing re-designed HRM practices in manufacturing SMEs

| Sl. No. | Barriers |

| 1 | Lack of knowledge and skills in handling online tools/techniques (B1). |

| 2 | Lack of skilled HR managers at affordable costs (B2). |

| 3 | Implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices (B3). |

| 4 | Lack of culture and favorable work environment (B4). |

| 5 | Lack of agility, creativity, and flexibility (B5). |

| 6 | Lack of Managers/owner commitment and poor leadership quality (B6). |

| 7 | Managers’ resistance (B7). |

| 8 | Employees’ resistance (B8). |

| 9 | Lack of HR infrastructure (B9). |

| 10 | Lack of comprehensive plan to implement new normal HRM practices (B10). |

Table 3

IRM for barriers in implementing re-designed HRM practices in manufacturing SMEs

| B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | B8 | B9 | B10 | |

| B1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| B3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| B5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| B6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| B7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| B8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| B9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Table 4

FRM for barriers in implementing re-designed HRM practices in manufacturing SMEs

| B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | B8 | B9 | B10 | Driving power | |

| B1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| B2 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 10 |

| B3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1* | 10 |

| B4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 7 |

| B5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| B6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| B7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| B8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| B9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 5 |

| B10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Dependence | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 8 |

**Represents transitive links.

Table 5

Interaction matrix

| B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | B8 | B9 | B10 | |

| B1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B2 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1* |

| B3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| B5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| B6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| B7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| B8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| B9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

*Represents significant transitive links.

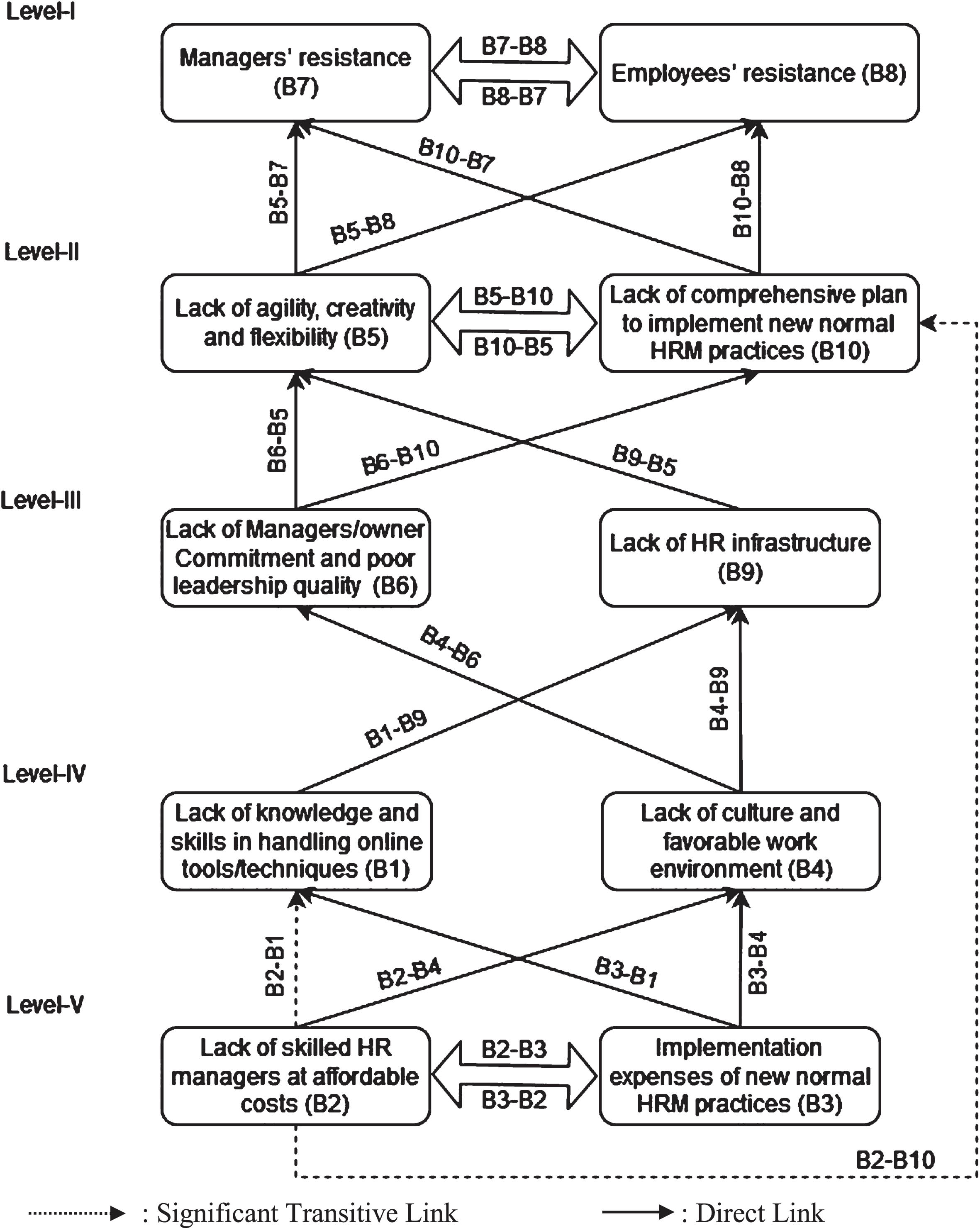

Fig. 2

TISM model for barriers in implementing re-designed HRM practices in manufacturing SMEs.

4Discussion

4.1Interpretation of TISM Di-graph

Figure 2 is a graphical illustration of the TISM analysis of the barriers preventing SMEs from implementing redesigned HRM practices in the post-pandemic era.

Level V: Level five has two barriers, lack of skilled HR managers at affordable costs and implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices.

The absence of proficient HR managers at affordable rates profoundly impacts the knowledge and skills necessary to handle online tools and techniques. These managers often need to travel to assist their workforce in adapting to the sweeping changes brought about by the pandemic [119]. They are pivotal in ensuring that remote workers have the resources they need to complete their tasks [120]. Additionally, remote working requires technological solutions that facilitate communication between employees and management [58]. Ensuring that employees are well-trained in using online tools and techniques is crucial. Furthermore, HR managers must support other department heads overseeing remote teams for the first time [111]. Consequently, SMEs need qualified HR managers to enhance employee skills in handling online tools, improve work quality, identify talent, and boost morale.

The scarcity of skilled HR managers also significantly impacts the expenses associated with implementing new HRM practices, organizational culture, agility, creativity, flexibility, and leadership commitment. Strategic HRM literature highlights the role of HR and top executives in developing and executing HRM practices [121, 122]. Remote working isn’t feasible for all manufacturing enterprises [5] and can’t extend to every position [6]. HR managers must identify roles suitable for remote work while ensuring physical distancing and protective measures for on-site roles. The drastic changes brought by the pandemic come with costs that can only be managed by highly skilled HR managers. Additionally, the lack of skilled HR managers influences the development of a favorable work culture, as they are critical in maintaining trust and providing employees with the freedom to manage their tasks effectively [125]. They also help the organization emphasize agility, innovation, and flexibility [126, 127], and their absence impacts manager commitment and leadership, as experienced HR professionals can develop successful processes and counsel management on employee issues [128]. Skilled HR managers play a crucial role in managing change, assisting with the implementation and tracking of large intervention strategies, and ensuring employee buy-in and support for change initiatives [85, 86]. Therefore, their scarcity affects employees’ resistance to change and the overall plan for implementing new normal HRM practices, as they are required to handle evolving workforce trends and organizational agility [132].

The financial constraints associated with implementing new HRM practices during a pandemic ripple across various critical dimensions of organizational management. Firstly, the lack of knowledge and skills in utilizing online tools and techniques is exacerbated by the substantial costs involved in adopting conventional HRM practices [112]. Businesses often struggle with limited budgets, hindering their ability to adequately train employees in digital tools essential for remote work. This shortfall not only jeopardizes operational efficiency but also underscores the risk of inadequate training investments that could ultimately cost more than they save. Consequently, many firms are unable to equip their workforce with the necessary skills to navigate online tools and procedures effectively, thereby compromising both employee retention and organizational development.

Secondly, the implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices profoundly impact the availability and affordability of skilled HR managers [133]. Amid economic uncertainties, the costs associated with upgrading HRM methods pose significant barriers to hiring experienced professionals who are crucial for enhancing employee performance and organizational resilience[134,135]. The financial burden often leads to strategic decisions such as adjusting pay structures to variable compensations tied to productivity, rather than investing in robust HR leadership [105]. This situation not only affects managerial commitment and leadership quality but also hampers efforts to foster a conducive workplace culture that adapts to new norms of remote and blended work models [136, 139]. Without sufficient financial resources allocated to HRM practices, businesses struggle to sustain their organizational culture and establish necessary HR infrastructures essential for operational continuity and employee well-being [57].

Level IV: Level four has two barriers, lack of knowledge and skills in handling online tools and techniques and lack of culture and favourable work environment.

The landscape of organizational agility, creativity, and flexibility is intricately tied to proficiency in utilizing online tools and techniques, which has emerged as a pivotal skill set amid the ongoing pandemic [140]. The rapid evolution in business operations necessitated swift transitions to remote work and digital integration across industries. However, the lack of adequate knowledge and skills in handling these tools hinders organizational agility and creativity, impeding the ability to adapt swiftly to dynamic market conditions. Effective utilization of online tools not only enhances operational efficiency but also fosters a culture of innovation and adaptability within teams, thereby enabling organizations to navigate uncertainties with resilience and responsiveness.

Resistance to change among managers and employees alike is profoundly influenced by their proficiency in utilizing online tools and techniques [141, 142]. Managers, in particular, face heightened scrutiny and pressure to lead digital transformations effectively. Without comprehensive training and support in digital tools, managerial resistance can stall organizational progress and innovation initiatives. Similarly, employees’ reluctance to adopt new practices stems from uncertainties about their ability to perform effectively with these tools [143]. This resistance underscores the critical need for organizations to invest in enhancing digital literacy across all levels, facilitating smoother transitions and greater acceptance of transformative HRM practices[144, 57]. Moreover, the absence of robust HR infrastructure during the pandemic underscores the importance of equipping HR managers with the necessary skills to leverage online technologies effectively for data management, employee engagement, and performance evaluation [145]. Without adequate knowledge and abilities in utilizing these tools, HR functions may falter, compromising organizational efficiency and strategic workforce management.

Organizational agility, creativity, and flexibility are profoundly shaped by the presence of a strong organizational culture and a supportive work environment [146]. These elements not only define operational norms and processes but also imbue employees with a sense of purpose and alignment with organizational goals. During the pandemic, the importance of a cohesive culture has been underscored, as it enables employees to navigate uncertainty and adapt swiftly to changing circumstances. Research emphasizes that organizations fostering an agile culture, grounded in shared values and bolstered by positive work environments, are better equipped to harness employee creativity and discretionary effort [146, 147]. This cultural foundation not only enhances resilience but also empowers employees to innovate and contribute meaningfully to organizational success.

Additionally, organizational culture significantly influences managerial commitment and leadership quality [148, 149]. A supportive work environment that cultivates trust and transparency enables managers to lead effectively through crises like the pandemic, fostering employee engagement and performance. Conversely, deficiencies in organizational culture can undermine managerial effectiveness and lead to resistance among employees and leaders alike [150]. By promoting a culture that values employee well-being and encourages open communication, organizations can mitigate resistance to change and build a resilient framework for sustained success. Moreover, nurturing a robust HR infrastructure aligned with ethical standards and organizational values is crucial for effectively managing human resources during turbulent times [151, 152]. Thus, organizations that prioritize cultivating a positive culture and fostering supportive work environments not only enhance agility and creativity but also fortify their ability to navigate challenges and capitalize on opportunities in an evolving landscape.

Level III: Level three has two barriers, Lack of manager/owner commitment and poor leadership quality, and Lack of HR infrastructure.

The lack of commitment from managers and owners, alongside poor leadership, significantly impacts organizational agility, innovation, and flexibility during crises such as the pandemic [153]. Strong managerial commitment fosters alignment with organizational goals, enhances employee engagement, and correlates with improved business performance, profitability, creativity, and productivity. Conversely, inadequate commitment and leadership quality contribute to managerial resistance to change, hindering the effective implementation of strategic HRM practices across organizational functions. This resistance, coupled with employees’ reluctance stemming from perceived threats and inadequate support, underscores the critical role of managerial commitment in navigating organizational change and fostering a resilient workplace culture that supports continuous improvement and operational stability.

The strength and resilience of a company heavily depend on the robustness of its HR infrastructure, which plays a critical role in managing administrative tasks and ensuring operational efficiency [154]. A well-established HR infrastructure not only supports daily business operations but also mitigates potential financial, productivity, and legal risks that could otherwise jeopardize organizational stability. Conversely, the absence or fragility of HR infrastructure significantly impacts managerial resistance to change, particularly during crises like the pandemic [155]. Effective HR practices communicated clearly and implemented strategically, can positively influence managers’ attitudes and behaviors, fostering a supportive environment for organizational initiatives and enhancing overall business outcomes. Thus, investing in a strong HR infrastructure is crucial for businesses to navigate challenges, maintain compliance, and sustain long-term success.

Level II: Level two has two barriers, lack of agility, creativity, and flexibility and lack of a comprehensive plan to implement new normal HRM practices.

Managers’ and employees’ resistance to change is profoundly influenced by their lack of agility, innovation, and flexibility [156]. Agile managers adeptly adjust their leadership styles and strategies in response to unforeseen circumstances, demonstrating a personalized approach that accommodates individual needs and preferences. Conversely, leaders who struggle with creativity and flexibility may resist change due to their inability to envision and implement novel solutions. Similarly, employees thrive in environments that foster agility, creativity, and flexibility, where they feel secure and motivated to embrace transitions [157]. In contrast, resistance emerges when organizational cultures fail to cultivate an innovative mindset, hindering employees from adapting to new practices and processes. Furthermore, the absence of agility, creativity, and flexibility compounds challenges in devising comprehensive plans to implement new normal HRM practices during crises like the pandemic. Effectively managing change demands a mindset that embraces alternative perspectives, breaks away from outdated norms, and swiftly adjusts to evolving circumstances, underscoring the critical role of these traits in navigating organizational transitions.

The lack of a comprehensive plan to implement new normal HRM practices significantly undermines agility, creativity, and flexibility within organizations, impacting their ability to swiftly adapt and innovate. Successful firms are distinguished by their agility and ability to foresee and respond to changes effectively, which necessitates meticulous planning and strategic controls [158]. Without a clear and detailed plan, managers struggle to enact necessary changes, leading to resistance as they grapple with tactical or logistical uncertainties that can derail the implementation process. Similarly, employees in disorganized environments experience heightened stress and frustration, contributing to their resistance to new practices due to the perceived lack of structure and support. Thus, the absence of a well-defined plan not only hampers organizational adaptability and innovation but also fosters resistance at both managerial and employee levels, highlighting the critical importance of strategic planning in navigating transitions.

Level I: Level one has two barriers, Managers’ resistance and Employees’ resistance.

Managers’ reluctance to change significantly influences employees’ resistance, shaping how employees interpret and respond to organizational transformations. Employees’ perceptions of change often mirror their managers’ attitudes and behaviors towards innovation versus stability, influencing their willingness to embrace new initiatives [159]. Conversely, employees’ resistance can also impact managers’ stance on change initiatives, as organizational transformations aimed at improving business outcomes can falter in the face of widespread employee opposition. This resistance can lead to project delays, financial setbacks, and reduced morale, ultimately affecting the organization’s ability to fully adopt new practices or procedures [160]. Managers, seeking to avoid negative feedback or disruptions, may revert to traditional methods, illustrating the interconnectedness between employees’ and managers’ attitudes towards change and its impact on organizational adaptation and innovation efforts. Thus, understanding and managing resistance at both levels is crucial for successful organizational change management.

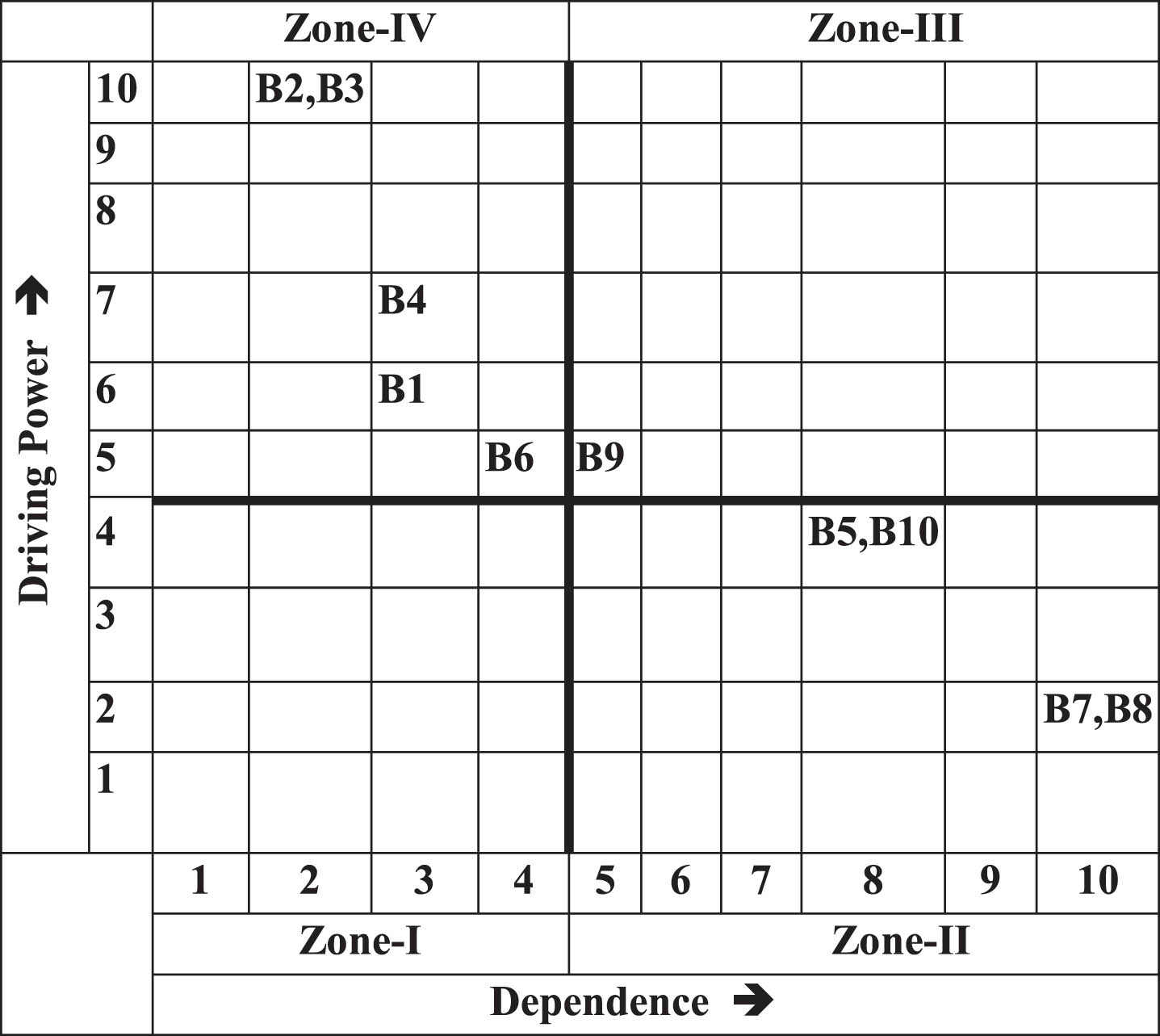

4.2MICMAC analysis

The MICMAC method divides barriers into four categories: driving barriers, autonomous barriers, dependent barriers, and linkage barriers [161, 162]. The following are some of the obstacles:

1. Autonomous barriers (Zone-I): Autonomous barriers are those that have little reliance and little driving power. In this study, no factors fall into the autonomous zone.

2. Dependent barriers (Zone-II): Dependence barriers are those that are more reliant on other barriers yet have less driving strength. In this study, Lack of agility, creativity, and flexibility (B5), Lack of a comprehensive plan to implement new normal HRM practices (B10), Manager’s resistance to change (B7), and Employee’s resistance to change (B8) are the dependent barriers. This barrier gets influenced when there is a change in the other barriers.

3. Linkage barriers (Zone-III): Linkage barriers are those that have a high degree of reliance and driving force. They establish a link between dependency and driving barriers. In this study, the lack of HRM infrastructure (B9) is the linkage barrier.

4. Driving or Independent barriers (Zone-IV): Driving or independent barriers are those that have a high driving power but little reliance. In this study, lack of skilled HR managers at affordable costs (B2), implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices (B3), lack of culture and favorable work environment (B4), lack of knowledge and skills in handling online tools/techniques (B1), lack of managers/owner support and poor leadership quality (B6) are the driving or key barriers.

As per the MICMAC analysis, the barriers impacting implementing re-designed HRM practices in manufacturing SMEs are ranked in Table 6.

Table 6

MICMAC ranks for barriers in implementing re-designed HRM practices in manufacturing SMEs

| Barrier | Driving power | Dependence | Driving power/dependence | MICMAC rank |

| B1 | 6 | 3 | 2.000 | 3 |

| B2 | 10 | 2 | 5.000 | 1 |

| B3 | 10 | 2 | 5.000 | 1 |

| B4 | 7 | 3 | 2.333 | 2 |

| B5 | 4 | 8 | 0.500 | 6 |

| B6 | 5 | 4 | 1.250 | 4 |

| B7 | 2 | 10 | 0.200 | 7 |

| B8 | 2 | 10 | 0.200 | 7 |

| B9 | 5 | 5 | 1.000 | 5 |

| B10 | 4 | 8 | 0.500 | 6 |

The MICMAC graph is depicted in Fig. 3. Based on the MICMAC study in Table 6, which depicts the driving power-dependence diagram. Table 6 shows the ranking of the barriers impacting the implementation of re-designed HRM practices in SMEs based on their driving power and dependence. According to the ranking, the lack of skilled HR managers at affordable costs (B2) and implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices (B3) are ranked 1. Managers’ resistance to change (B7) and employees’ resistance to change (B8) are ranked seventh in the MICMAC analysis ranking. It means that it has a higher dependence on other factors.

Fig. 3

MICMAC graph.

5Implications

5.1Theoretical implications

The adoption of the Resource-Based View (RBV) theory in this study provides significant theoretical insights into the barriers to implementing re-designed HRM practices in the post-pandemic era, particularly within the context of SMEs and employee well-being. RBV emphasizes the strategic management of resources and capabilities to secure a sustainable competitive advantage [16, 163]. In the realm of post-pandemic HRM practices in SMEs, RBV serves as a framework to understand how deficiencies in resources—such as skilled HR managers, knowledge, infrastructure, and financial capital—can obstruct the effective implementation of re-designed HRM practices. This perspective underscores the essential role of resource management in surmounting these obstacles and driving successful HRM policy re-design post-pandemic. Moreover, RBV illuminates the impact of organizational factors, including culture, leadership quality, and agility, on the attitudes of employees and managers toward change, thereby affecting the implementation of new HRM practices and, ultimately, employee well-being.

The study’s findings, particularly regarding the identified barriers and their interdependencies, hold substantial theoretical implications. Utilizing the TISM approach allowed for the construction of a hierarchy of barriers, revealing that certain barriers are more critical and influential than others in hindering the implementation of re-designed HRM practices in Indian manufacturing SMEs. Notably, “Lack of skilled HR managers at affordable costs” and “Implementation expenses of new normal HRM practices” emerged as the most pivotal barriers, exerting influence over all other barriers. This highlights the crucial importance of human resource management capabilities and financial considerations in the successful adoption of re-designed HRM practices. Additionally, the identification of “Manager’s resistance to change” and “Employee’s resistance to change” as highly dependent on other barriers emphasizes the necessity for organizations to address these dependencies to effectively implement re-designed HRM practices post-pandemic.

5.2Managerial implications

The results of the study have important implications that will be useful for owners of manufacturing SMEs, HR managers, and academics working on new normal HRM practices, especially in this post-pandemic. To improve the implementation process for manufacturing SMEs, the study identified a set of barriers to applying new conventional HRM practices. The findings of the analysis of the aforementioned barriers will allow manufacturing SMEs to determine which ones are the most and least important, as well as how they relate to one another. Additionally, recognizing these obstacles will assist owner-managers of SMEs in enhancing and improving HRM policies and systems by making the proper decisions that facilitate employees’ efficient usage of such systems. It also helps managers and practitioners become more aware of the new norms in HRM. Because these barriers might interact with one another, the current study advises eradication tactics and assists in identifying important HRM barriers.

This pandemic crisis has made organizations and employees adapt to consistent changes in work and working conditions, procedures, and ways of communication. A huge response is placed on the HR managers to simultaneously satisfy organizational objectives and employees’ well-being. Thus, owner-managers of SMEs need to incorporate comprehensive pandemic planning considerations that support the firm’s interest in employees’ well-being. This pandemic has intensified the firm’s digital transition, which has forced employees to equip themselves with the necessary skills and technology. Owner-managers of SMEs should also consider hiring HR professionals for their organizations since they are responsible for designing and implementing HR strategies. Besides, only HR managers can keep employees motivated, productive, and engaged in this current scenario. The owner-managers of SMEs should start using social networking websites for carrying out HRM activities since they are more cost-effective than traditional HRM practices. Also, they need to create a favourable and supportive work environment in which employees and managers can coordinate to work together. Further, HRM practices like recruitment and selection, mentoring and encouraging employees, managing performance, and taking care of employees’ well-being can be effectively accomplished only if the organizations are agile, creative, and flexible. Thus, managers are expected to take the necessary initiatives so that organizations can become more agile, creative, and flexible to handle the challenges posed by the pandemic. Finally, whenever a change happens inside the organization, it is generally human nature to resist change and maintain the status quo. Thus, owner-managers of SMEs should understand the reasons for managers’ and employees’ resistance to change and take proactive actions. They should also motivate and communicate with employees regarding the benefits of change so that they can believe, understand, and facilitate effective HRM implementation. This study will be useful to managers and practitioners of SMEs in comprehending the challenges in HRM implementation, particularly during this pandemic. Policymakers and governments need to support SMEs during the digital transition by creating awareness, funding, training, and support.

Various employers encountered employment vacancies and recruitment issues as a result of the pandemic. Employee training programs are reduced as needed to guarantee that business runs smoothly and that employees remain safe in their workplace. Performance management has been scrutinized after seemingly impossible goals were not met, and monitoring staff who worked from home became prohibitively expensive. Several organizations were unable to pay their employees’ salaries or provide other essential services, such as financial benefits, as a result of the pandemic during economic downturns, HR departments must re-design existing HRM processes to improve operational efficiency while also supporting employee empowerment and well-being. This research contributes to the identification of numerous barriers by explaining how they interact with HRM practices, particularly in manufacturing SMEs.

5.3Policy recommendations

Based on the study’s findings, several policy recommendations can be proposed to address the identified barriers to implementing re-designed HRM practices in Indian manufacturing SMEs in the post-pandemic era. Firstly, policymakers need to focus on enhancing the availability and affordability of skilled HR managers. This can be achieved through initiatives such as government-sponsored training programs and collaborations with educational institutions to develop specialized HRM courses tailored for SMEs. Secondly, measures should be taken to reduce the implementation expenses of new HRM practices, such as providing financial incentives or subsidies to SMEs for investing in HRM technology and infrastructure. Additionally, fostering a culture of change and innovation within SMEs, supported by effective leadership and managerial practices, can help mitigate resistance to change among employees and managers. Moreover, enhancing the overall HRM infrastructure and promoting a favorable work environment that values employee well-being can contribute significantly to the successful implementation of re-designed HRM practices. Overall, these policy recommendations aim to create an enabling environment for SMEs to effectively implement re-designed HRM practices, thereby enhancing their competitiveness and sustainability in the post-pandemic landscape.

6Conclusions

This study has successfully addressed its research objectives by identifying and analyzing the barriers to implementing re-designed HRM practices in Indian manufacturing SMEs in the post-pandemic era. Through the application of the RBV theory and the TISM approach, the study has provided valuable insights into the factors influencing the implementation of HRM practices in SMEs, particularly focusing on employee well-being. The findings highlight the importance of addressing key barriers such as the lack of skilled HR managers, high implementation expenses, and resistance to change among managers and employees.

The study’s theoretical implications lie in its application of RBV and TISM to HRM practices, offering a novel perspective on how organizations can leverage their resources and capabilities to overcome barriers and drive successful HRM policy redesign. From a practical standpoint, the study provides actionable policy recommendations for policymakers and SMEs to enhance the availability of skilled HR managers, reduce implementation expenses, and foster a culture of change and innovation. These recommendations aim to create a conducive environment for SMEs to implement re-designed HRM practices effectively, thereby enhancing their competitiveness and sustainability in the post-pandemic landscape. Overall, this study contributes to the existing literature on HRM practices in SMEs and provides valuable insights for both academia and practitioners in the field.

Like other studies, the present study also has some limitations, which can be taken as agendas for future research. The results of this study cannot be generalized since the study considered small samples, focusing mainly on manufacturing SMEs in India. Thus, future research can be carried out with large samples focusing on different industries and countries. The study was intended to identify the interrelationships among the barriers and neglected the effects of individual factors. Hence, future studies may be carried out to analyze the influence of individual factors on the effective implementation of HRM. Also, the investigation highly depends on experts’ opinions which may be biased to the kind of experience and exposure they have. This study employed the TISM approach to find the interrelationships between barriers in HRM implementation, which may be utilized for decision-making. Future studies may be carried out using other decision-making tools like TOPSIS and DEMATEL to enhance the reliability of the results. Finally, the interrelations and dependency among factors could be empirically validated through hypothesis building.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgments.

Author contributions

CONCEPTION: Suresh and Bhavin

METHODOLOGY: Nagamani and Suresh

DATA COLLECTION: Nagamani

INTERPRETATION OR ANALYSIS OF DATA: Nagamani

PREPARATION OF THE MANUSCRIPT: Bhavin

REVISION FOR IMPORTANT INTELLECTUAL CONTENT: Bhavin

SUPERVISION: Suresh

References

[1] | Carnevale JB , Hatak I . Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research. (2020) ;116: :183–7. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037 |

[2] | Dissanayake K . Encountering COVID-19 Human resource management (HRM) practices in a pandemic crisis. Colombo Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Research. (2020) ;5: (1-2):1–22. |

[3] | Opatha HH . The coronavirus and the employees: a study from the point of human resource management. Sri Lankan Journal of Human Resource Management. (2020) ;10: (1). |

[4] | Gourinchas PO . Flattening the pandemic and recession curves. Mitigating the COVID economic crisis: Act fast and do whatever. (2020) ;31: (2):57–62. |

[5] | Koirala J , Acharya S . Dimensions of human resource management evolved with the outbreak of COVID-19. Available at SSRN 3584092. (2020) . |

[6] | Bartik AW , Cullen ZB , Glaeser EL , Luca M , Stanton CT . What jobs are being done at home during the COVID-19 crisis? Evidence from firm-level surveys. National Bureau of Economic Research; (2020) . 10.3386/w27422 |

[7] | Parry E , Battista V . The impact of emerging technologies on work: a review of the evidence and implications for the human resource function. Emerald Open Research. (2019) ;1: (5):5. 10.12688/emeraldopenres.12907.1 |

[8] | Harney B , Dundon T . Capturing complexity: developing an integrated approach to analysing HRM in SMEs. Human Resource Management Journal. (2006) ;16: (1):48–73. |

[9] | Tansky JW , Heneman R . Guest editor’s note: Introduction to the special issue on human resource management in SMEs: A call for more research. Human Resource Management. (2003) ;42: (4):299. |

[10] | Barrett R , Mayson S . Human resource management in growing small firms. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. (2007) ;14: (2):307–20. 10.1108/14626000710746727 |

[11] | Mahmoud M , Othman R . New public management in the developing countries: effects and implications on human resource management. Journal of Governance and Integrity. (2021) ;4: (2):73–87. 10.15282/jgi.4.2.2021.5573 |

[12] | Johnstone S . Employment practices, labour flexibility and the Great Recession: An automotive case study. Economic and Industrial Democracy. (2019) ;40: (3):537–59. |

[13] | Sushil , Dinesh KK . Structured literature review with TISM leading to an argumentation based conceptual model. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. (2022) ;23: (3):387–407. |

[14] | Dubey R , Gunasekaran A , Papadopoulos T , Childe SJ , Shibin KT , Wamba SF . Sustainable supply chain management: framework and further research directions. Journal of cleaner production. (2017) ;142: :1119–30. |

[15] | Barney J . Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of management. (1991) ;17: (1):99–120. |

[16] | Barney JB . Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. Journal of Management. (2001) ;27: (6):643–50. |

[17] | Acedo FJ , Barroso C , Galan JL . The resource-based theory: dissemination and main trends. Strategic Management Journal. (2006) ;27: (7):621–36. |

[18] | Shin J , Mollah MA , Choi J . Sustainability and organizational performance in South Korea: The effect of digital leadership on digital culture and employees’ digital capabilities. Sustainability. (2023) ;15: (3):2027. |

[19] | Collins CJ . Expanding the resource based view model of strategic human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. (2021) ;32: (2):331–58. |

[20] | Zhang JA , Edgar F . HRM systems, employee proactivity and capability in the SME context. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. (2022) ;33: (16):3298–323. |

[21] | Dubey R , Ali SS . Identification of flexible manufacturing system dimensions and their interrelationship using total interpretive structural modelling and fuzzy MICMAC analysis. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. (2014) ;15: :131–43. |

[22] | Prasad UC , Suri RK . Modeling of continuity and change forces in private higher technical education using total interpretive structural modeling (TISM). Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. (2011) ;12: :31–9. |

[23] | Sushil Srivastava A . Adapt: a critical pillar of strategy execution process. Organisational Flexibility and Competitiveness. (2014) :9–24. |

[24] | Yadav MS , Pavlou PA . Marketing in computer-mediated environments: Research synthesis and new directions. Journal of Marketing. (2014) . |

[25] | Sushil . Interpreting the interpretive structural model. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. (2012) ;13: :87–106. |

[26] | Dubey N , Bomzon SD , Murti AB , Roychoudhury B . Soft HRM bundles: a potential toolkit for future crisis management. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. (2024) . |

[27] | Rangaswamy E , Nawaz N , Lu E . Impact of COVID-19 on Singapore human resource practices. Cogent Business & Management. (2024) ;11: (1):2301791. |

[28] | Hamouche S . Human resource management and the COVID-19 crisis: Implications, challenges, opportunities, and future organizational directions. Journal of Management & Organization. (2023) ;29: (5):799–814. |

[29] | Ashour S . How COVID-19 is reshaping the role and modes of higher education whilst moving towards a knowledge society: The case of the UAE. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning. (2024) ;39: (1):52–67. |

[30] | Brown A , Leite AC . The effects of social and organizational connectedness on employee well-being and remote working experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. (2023) ;53: (2):134–52. |

[31] | Yue CA , Thelen PD , Walden J . How empathetic leadership communication mitigates employees’ turnover intention during COVID-19-related organizational change. Management Decision. (2023) ;61: (5):1413–33. |

[32] | Sumardjo M , Supriadi YN . Perceived Organizational Commitment Mediates the Effect of Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Culture on Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Calitatea. (2023) ;24: (192):376–84. |

[33] | Pradhan RK , Panda M , Hati L , Jandu K , Mallick M . Impact of COVID-19 stress on employee performance and well-being: role of trust in management and psychological capital. Journal of Asia Business Studies. (2024) ;18: (1):85–102. |

[34] | Yang L , Lou J , Zhou J , Zhao X , Jiang Z . Complex network-based research on organization collaboration and cooperation governance responding to COVID-19. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. (2023) ;30: (8):3749–79. |

[35] | Buller PF , McEvoy GM . A model for implementing a sustainability strategy through HRM practices. Business and Society Review. (2016) ;121: (4):465–95. |

[36] | Ehnert I . Paradox as a lens for theorizing sustainable HRM: Mapping and coping with paradoxes and tensions. In Sustainability and human resource management: Developing sustainable business organizations. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; (2013) , pp. 247–271. |

[37] | Malik SY , Cao Y , Mughal YH , Kundi GM , Mughal MH , Ramayah T . Pathways towards sustainability in organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management practices and green intellectual capital. Sustainability. (2020) ;12: (8):3228. 10.3390/su12083228 |

[38] | Johnstone S . Employment practices, labour flexibility and the Great Recession: An automotive case study. Economic and Industrial Democracy. (2019) ;40: (3):537–59. |

[39] | Guest D , Bos-Nehles A . Human resource management and performance: the role of effective implementation. In Human resource Management and Performance (5th ed): Achievements and Challenges. Wiley; (2013) , pp. 79–96. |

[40] | Armstrong M , Taylor S . Armstrong’s handbook of human resource management practice. Kogan Page Publishers; (2020) . |

[41] | Howlett E . How should HR support managers on staff wellbeing as the Covid crisis continues? [Internet]. Available from: https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/news/articles/how. [Accessed 12 July 2021]. |

[42] | Mariappanadar S . Do HRM systems impose restrictions on employee quality of life? Evidence from a sustainable HRM perspective. Journal of Business Research. (2020) ;118: :38–48. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.039 |

[43] | Fallon N . How to Support Your Employees in a Crisis. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.uschamber.com/co/run/human-resources/how-to-support-youremployees-in-a-crisis. [Accessed 15 May 2021]. |

[44] | Gigauri I . Challenges HR managers facing due to COVID-19 and overcoming strategies: perspectives from Georgia. Archives of Business Review. (2020) ;8: (11). |

[45] | Andalib Ardakani D , Soltanmohammadi A , Seuring S . The impact of customer and supplier collaboration on green supply chain performance. Benchmarking: An International Journal. (2023) ;30: (7):2248–74. |

[46] | Das D , Datta A , Kumar P . Exit Strategies for COVID 19: An ISM and MICMAC approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management. (2020) ;15: (3):94–109. |

[47] | Pandey P , Agrawal N , Saharan T , Raut RD . Impact of human resource management practices on TQM: An ISM-DEMATEL approach. The TQM Journal. (2021) ;34: (1):199–228. |

[48] | Attri R , Dev N , Sharma V . Interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach: an overview. Research Journal of Management Sciences. (2013) ) 2319: (2):1171. |

[49] | Abdalla W , Renukappa S , Suresh S , Algahtani K . Techniques and technologies for managing COVID-19 related Knowledge: A Systematic Review, In European Conference on Knowledge Management (2022) Aug 25 (Vol. 23, No. 1). |

[50] | Dolo JJ . Reimagining Tacit Knowledge Transfer in a Remote Work Era (Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland University College). (2023) . 30573314. |

[51] | Fraij J . E-HRM to overcome HRM challenges in the pandemic. SEA–Practical Application of Science. (2021) ;9: (25):41–9. |

[52] | Szeiner Z , Juhász T , Hevesi E , Poór J . HRM challenges in Slovakia generated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Central European Management Journal. (2023) . |

[53] | Charernnit K , Treruttanaset P . Strategic human resource management in aviation industry a new normal perspective after the COVID-19 crisis: a case study of Bangkok Airways. In E3S Web of Conferences 2023 (Vol. 389, p. 05015). EDP Sciences. |

[54] | Bergum S , Peters P , Vold T , editors. Virtual Management and the New Normal: New Perspectives on HRM and Leadership Since the COVID-19 Pandemic. Springer Nature; (2023) Jan 31. |

[55] | Piwowar-Sulej K , Malik S , Shobande OA , Singh S , Dagar V . A Contribution to Sustainable Human Resource Development in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Business Ethics. (2023) :1–9. |

[56] | Cai Y , Rowley C , Xu M . Workplaces during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: insights from strategic human resource management in Mainland China. Asia Pacific Business Review. (2023) ;29: (4):1170–91. |

[57] | Parent DJ . HR Infrastructure & Safety Performance: Considerations for Small Companies. Professional Safety. (2015) ;60: (8):48. |

[58] | Prasad KD , Vaidya RW . Association among Covid-19 parameters, occupational stress and employee performance: An empirical study with reference to Agricultural Research Sector in Hyderabad Metro. Sustainable Humanosphere. (2020) ;16: (2):235–53. |

[59] | Kim J , Lee HW , Chung GH . Organizational resilience: leadership, operational and individual responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Organizational Change Management. 2023. |

[60] | Heidt L , Gauger F , Pfnür A . Work from Home Success: Agile work characteristics and the Mediating Effect of supportive HRM. Review of Managerial Science. (2023) ;17: (6):2139–64. |

[61] | Jada U , Swain D , John T , Jena LK . Does leadership style and HRM Practices promote employee well-being post onset of the new normal? a mixed-method approach. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management. (2023) :23220937231186937. |

[62] | Malik A , Gupta J , Gugnani R , Shankar A , Budhwar P . Unlocking the relationship between ambidextrous leadership style and HRM practices in knowledge-intensive SMES. Journal of Knowledge Management. (2024) . |

[63] | Arthur D . Managing human resources in small and mid-size companies. New York: American Management Association; (1995) . |

[64] | De Clercq D , Pereira R . How human resource managers can prevent perceived pandemic threats from escalating into diminished change-oriented voluntarism. Personnel Review. (2023) ;52: (6):1654–76. |

[65] | Sutarman A , Nugroho AW , Anjani FK , Arthamevia AK . Employment Adjustment And Leadership Capability During A Pandemic Covid-19 And Its Implications For Human Resource Management In Industry In Jakarta. Jurnal Apresiasi Ekonomi. (2023) ;11: (3):610–9. |

[66] | Haffar M , Al-Karaghouli W , Djebarni R , Al-Hyari K , Gbadamosi G , Oster F , Alaya A , Ahmed A . Organizational culture and affective commitment to e-learning’changes during COVID-19 pandemic: The underlying effects of readiness for change. Journal of Business Research. (2023) ;155: :113396. |

[67] | Sa’ad Al Hyari H . Change Resistance Management And The Transition To Distamce Learning During COVID-19: Moderating Role Of Education Technology. International Journal of Professional Business Review: Int J Prof Bus Rev. (2023) ;8: (3):4. |

[68] | Maddox-Daines KL . Delivering well-being through the coronavirus pandemic: the role of human resources (HR) in managing a healthy workforce. Personnel Review. (2023) ;52: (6):1693–707. |

[69] | Aggarwal PJ , Khurana N , Shefali . Impact of HRM practices on employee productivity in times of COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management. (2023) ;38: (1):73–97. |