Servant leadership, work engagement and affective commitment in social exchange perspective: A mediation-moderation framework

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Servant leadership plays a crucial role in fostering employees’ affective commitment within organizations. However, understanding the underlying mechanism through which servant leadership influences affective commitment is important to provide valuable insights into organizational research and practice.

OBJECTIVE:

This study aims to examine the mediating and moderating role of work engagement on the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment in social exchange theory (SET).

METHODS:

Using the quantitative data via the completion of an online survey derived from employees in Indonesian public health institution, 154 useful data were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Additionally, SmartPLS version 3.2 was utilized for testing the proposed hypotheses.

RESULTS:

The results of the study show that servant leadership has no significant effect on affective commitment, but significant on work engagement. Also, the finding confirmed that work engagement has a significant effect on affective commitment. Furthermore, the empirical findings highlighted that work engagement fully mediates the link between servant leadership and affective commitment. However, regarding the moderation effect, work engagement does not moderate the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment.

CONCLUSION:

Servant leadership, rooted in the philosophy of serving others first, is theorized to have a significant impact on work engagement through the lens of SET. Servant leaders, by prioritizing the needs and development of their employees, foster a supportive work environment characterized by trust and empowerment. In return, employees reciprocate by investing more effort and energy into their work, leading to higher levels of work engagement.

Udin Udin is an assistant professor in Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He completed his Doctoral degree (PhD) in Human Resource Management at Diponegoro University, Indonesia. He has published many papers in reputable international journal. His research interest includes leadership, knowledge management, Islamic business ethics, and positive human behavior. He can be contacted at: E-mail:

Suteera Chanthes is an assistant professor of Economics, Mahasarakham University, Thailand. Her research area includes triple helix model, knowledge-based entrepreneurship, university engagement, and regional development. She can be contacted at: E-mail:

Radyan Dananjoyo is an assistant professor in Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia. His research area focuses on marketing management including retail marketing, service quality, and sustainable housing. He can be contacted at: E-mail:

1Introduction

Public sector hospitals, also known as government hospitals, are healthcare institutions that receive their funding and ownership from governmental entities, including federal, state, or local governments. These hospitals play a crucial role in providing healthcare services [1, 2] to the public. However, public sector hospitals often face tight budgets, and leaders must find ways to allocate limited resources effectively while maintaining the quality of patient care. Also, public sector hospitals can be burdened by bureaucratic processes, which can slow decision-making and hinder innovation. Leaders need to find ways to streamline operations and reduce administrative inefficiencies. Therefore, strong leadership, efficient management practices, and a commitment to continuous improvement in healthcare delivery are required in public sector hospitals.

Among various leadership styles, servant leadership is considered effective in healthcare, promoting openness, transparency, and empowerment [3]. The servant leader focuses on serving the needs of others and nurturing the growth of employees to create positive work environments [4]. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration has adopted servant leadership as their model, demonstrating its relevance in the largest US healthcare system [5]. Additionally, Mostafa and El-Motalib [6] found that servant leadership positively relates to proactive behaviors among employees.

Bai, Zheng [7] acknowledged that servant leadership for hospitals promotes higher and better employee affective commitment. Similar to the previous studies, Aboramadan, Dahleez [8], Dahleez, Aboramadan [9], Ghasemy and Frömbling [10], Ngah, Abdullah [11] found that servant leadership has a positive effect on affective commitment. Franco and Antunes [12] further revealed that servant leadership strongly boosts affective commitment, inducing higher levels of organizational commitment. However, other studies demonstrate that servant leadership has no significant effect on affective commitment [13] and overall organizational commitment [14, 15]. Servant leadership fails to encourage volunteer satisfaction to contribute positively to the organization because they find it too difficult to meet their needs and work experience [16].

This study, therefore, endeavours to address the gaps in existing studies by presenting a fresh perspective derived from the social exchange theory (SET). Additionally, this study aims to investigate the role of work engagement as a possible intermediary factor in the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment.

2Literature review

2.1Social exchange theory

The social exchange theory (SET) is a theoretical framework used in organizational psychology and sociology to improve organizations by understanding the relationships between individuals within the organization [17]. SET is based on the idea that individuals engage in social interactions with others with the expectation of receiving certain profits, benefits and rewards in return [18] for their contributions. SET emphasizes the well-being of individuals within the organization. Supporting employee well-being through initiatives like work-life balance programs, mental health support, and a positive work environment can enhance the overall exchange of resources. Additionally, organizations should ensure that exchanges are transparent, impartial, fair, and aligned with ethical standards. By applying SET, organizations can create a more productive work environment [19], enhance employee engagement, and ultimately achieve better organizational outcomes.

2.2Affective commitment

Affective commitment, a concept primarily used in the context of organizational psychology, refers to the emotional attachment and a strong sense of identification that employees feel toward their organization. This type of commitment is one of the components of organizational commitment, with the other two being continuance commitment (based on perceived costs of leaving the organization) and normative commitment (based on a sense of moral obligation to stay with the organization) [20]. Affective commitment is particularly important for creating a better organization because it is associated with higher job performance [21] and increased willingness to go beyond [22] in one’s role. When employees have a high level of affective commitment, they feel a strong sense of belonging [23], loyalty, and enthusiasm toward their organization.

2.3Work engagement

Work engagement refers to the fulfilling and enthusiastic state of mind that employees experience when they are fully absorbed in their work. Work engagement is characterized by three key components [24]: (a) dedication refers to a sense of significance and pride in one’s work. Employees who are dedicated to their work feel a deep sense of meaning to their job and the organization. They are emotionally committed to their work and are willing to go the extra mile; (b) vigor represents high levels of energy and mental resilience while working. Employees who experience vigor are strongly willing to invest effort in their tasks and can persist even in the face of challenges; (c) absorption reflects a state of being fully concentrated and happily engrossed in one’s work. When employees are absorbed in their tasks, they lose track of time and are completely immersed in what they are doing. Thus, highly engaged employees are deeply involved in their tasks, passionate about their jobs, and feel a strong connection to their organization [25]. Additionally, cultivating work engagement is essential for creating a productive and better organization, as engaged employees are more committed and satisfied [26].

2.4Servant leadership

In contemporary organizations, servant leadership is growing in significance and being increasingly appreciated. Servant leadership, as popularized by Greenleaf [27] in his essay “The Servant as Leader,” is a leadership style that leaders prioritize the well-being and development of their employees. Servant leadership, at its core, is a values-based approach that prioritizes the needs of others, such as team members or employees, above the leader’s self-interest. Servant leaders are deeply committed to the personal and professional growth of those they lead and are driven by a genuine desire to serve others [28]. This ultimately philosophy is rooted in a culture of ethics, humility, and empathy within the organization.

Servant leaders focus on serving others first and create organizations characterized by inclusivity, engagement, innovation, and ethical conduct [29]. Servant leadership stands out from other leadership styles due to a unique set of principles that define its distinctive nature. These principles, according to van Dierendonck [30], include: (a) self-awareness i.e., leaders have a profound grasp of their strengths, weaknesses, and values. This self-awareness enables them to make ethical decisions and to be authentic in their interactions with employees; (b) empathy i.e., leaders possess a deep sense of empathy and compassionate, which enables them to understand their employees’ emotions, thoughts and experiences. This profound empathy informs their decision-making process, leading to choices that take into account the individual impact; (c) service i.e., leaders giving precedence to the needs of others and proactively searching for chances to support their employees. This unselfish dedication is not a mere strategy but a sincere commitment to fostering the well-being of others; (d) humility i.e., leaders openly acknowledge their own limitations and show appreciation for the contributions of others. They are not driven by the pursuit of personal glory but are content in their role as enablers of their employees’ success; (e) commitment to growth i.e., leaders are dedicated to fostering the growth and progress of their employees. They actively create avenues for learning, skill enhancement, and career advancement; (f) stewardship i.e., leaders are entrusted with the responsibility to develop the potential of their employees. This stewardship extends to the organization as a whole, as servant leaders seek to ensure the long-term well-being of the organization.

Servant leaders further promote a culture of continuous improvement [31, 32]. They encourage their employees to seek ways to enhance processes, innovate, and adapt to changing circumstances. Also, servant leaders empower their employees by giving them autonomy and decision-making authority. This helps employees feel more engaged in their work, leading to increased commitment and a supportive work environment.

3Hypotheses development

3.1Impact of servant leadership on affective commitment and work engagement

Servant leaders often prioritize building trust [33] and showing respect for their employees. Also, servant leaders focus on sustainable organizational growth and the well-being of employees. In SET, this behavior fosters a positive exchange relationship. When employees perceive that their leader genuinely cares about their well-being, they are more likely to reciprocate with increased affective commitment to the organization [9, 34]. Thus,

H1: Servant leadership a direct and significant effect on affective commitment.

Servant leaders are known for providing support, mentorship, and development opportunities to their employees [35]. This support can lead to increased work engagement because employees feel valued and appreciated [36]. In return, they may invest more of their energy and effort into their roles. In SET, when employees feel they can trust their leaders and openly share their concerns without fear of retribution, they are more likely to engage fully in their work [37]. Thus,

H2: Servant leadership has a direct and significant effect on work engagement.

3.2Impact of work engagement on affective commitment

Work engagement involves employees investing their physical, emotional, and cognitive energy into their work roles [38]. When employees are engaged and give their best effort, they often experience positive outcomes such as recognition and personal growth. In SET, individuals tend to reciprocate positive actions with favorable treatments [39]. When employees experience high levels of work engagement, they often perceive that the organization is investing in their well-being by providing them with a fulfilling work experience. In response, they may reciprocate by developing a strong affective commitment to the organization [40]. Thus,

H3: Work engagement has a direct and significant effect on affective commitment.

3.3Work engagement as a mediator and moderator variable

Work engagement refers to the level of enthusiasm, dedication, and energy employees invest in their work [41]. When employees experience servant leadership, it often leads to higher levels of work engagement, which, in turn, fosters higher levels of affective commitment among employees [42]. Servant leaders prioritize the well-being and growth of their employees. They lead by serving, showing empathy, providing support, and empowering their employees [43]. These leadership behaviors create a positive work environment. In SET, employees may feel a sense of reciprocity when they experience servant leadership. They reciprocate the leader’s supportive behaviors by fully engaging in their work and becoming emotionally committed to the organization. Therefore, organizations that promote servant leadership behaviors can indirectly enhance employee commitment by fostering higher levels of work engagement [44, 45]. Employees who are highly engaged are more likely to perceive servant leadership positively, which in turn strengthens their affective commitment. Conversely, if engagement is low, the positive effects of servant leadership might not translate into increased affective commitment as effectively. Therefore,

H4: Work engagement mediates the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment.

H5: Work engagement moderates the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment.

4Research methods

4.1Sample and procedure

This empirical study was conducted in Indonesian public health institution in Central Java from March to June 2023. Using purposive sampling for collecting the quantitative data of 255 employees (e.g. nurses and administrative staff), 154 filled-in questionnaires are returned (with a 60.4% response rate). Among the validly returned questionnaires, 68.8% respondents are women and 31.2% are men. In addition, the survey data shows that the work experience of 1–3 years, 4–6 years, and over 7 years are 29.9%, 37%, and 33.1% of respondents, respectively.

4.2Measurement

Servant leadership. Servant leadership is assessed using a 13-item scale adapted from Jaramillo, Grisaffe [46], Choudhary, Akhtar [47]. An illustrative item from this scale is: “I experience a sense of ‘responsibility’ towards my supervisor”.

Work engagement. Work engagement is evaluated through a set of 6 items, which have been adjusted from Fletcher [48], Udin, Dananjoyo [49]. One of the items as an illustration reads: “I experience a robust and energetic demeanor in my job”.

Affective commitment. Affective commitment is gauged via a series of 5 items, adapted from the works of Vandenberghe, Bentein [50], Astuty and Udin [51]. One of the sample items reads as follows: “I take pride in being a meaningful contributor to the organization”.

The questionnaire employs a 5-point Likert scale for respondents to provide their ratings. This scale encompasses a spectrum from 1, signifying “strongly disagree”, to 5, denoting “strongly agree”.

4.3Technique for data analysis

Partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) is a statistical technique used for modeling and analyzing relationships between observed variables and latent in social sciences, business research, and other fields. PLS-SEM is employed for data analysis in this research, utilizing SmartPLS 3.2 software. The selection of SmartPLS software aligns with the recommendations of Sarstedt, Ringle [52] for effective PLS-SEM implementation. PLS-SEM is a widely accepted approach in the field of business management research [53] for examining intricate relationships. Hair, Sarstedt [54] recommend using power analysis for determining sample size. For the medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) at the significance level of 0.05, G*Power suggest that around 80–100 samples are sufficient. By satisfying this criteria, 154 employees involved in the present study not only meet the heuristic guidelines but also the rigorous statistical standards.

5Results and discussion

PLS-SEM was used in this study to test and validate theoretical model by examining both the direct and indirect effects among investigated variables. SmartPLS, specifically, is known for its user-friendly interface and its ability to handle complex models with latent variables [53], making it a valuable tool for researchers in understanding intricate relationships within the data.

Table 1 showed the results of assessing the reliability and validity of constructs in the proposed model, particularly in the context of SEM including factor loading, variance inflation factor (VIF), Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). All of the constructs, as shown in Table 1, had loading values higher than 0.5 [55] and VIF values lower than 5. Additionally, the values of CA and CR were higher than 0.7 [53]. Moreover, the value of AVE for all of the constructs was higher than 0.3. Fornell and Larcker [56] noted that even if the AVE for a construct is below the commonly recommended threshold of 0.5, it can still be considered acceptable if the CR for the construct is greater than 0.6. Therefore, these findings support the validity and reliability of the measurement model in this study.

Table 1

Construct reliability and validity

| Constructs | Items | Loading | VIF | CA | CR | AVE |

| Servant leadership | SL1 | 0.555 | 1.345 | 0.809 | 0.851 | 0.344 |

| SL4 | 0.532 | 1.337 | ||||

| SL5 | 0.524 | 1.421 | ||||

| SL6 | 0.606 | 1.567 | ||||

| SL7 | 0.574 | 1.298 | ||||

| SL8 | 0.634 | 1.388 | ||||

| SL9 | 0.670 | 1.754 | ||||

| SL10 | 0.542 | 1.471 | ||||

| SL11 | 0.549 | 1.340 | ||||

| SL12 | 0.702 | 1.596 | ||||

| SL13 | 0.532 | 1.283 | ||||

| Work engagement | WE1 | 0.627 | 1.432 | 0.741 | 0.819 | 0.393 |

| WE2 | 0.710 | 1.562 | ||||

| WE3 | 0.619 | 1.366 | ||||

| WE5 | 0.613 | 1.518 | ||||

| WE6 | 0.577 | 1.482 | ||||

| WE8 | 0.587 | 1.292 | ||||

| WE9 | 0.646 | 1.355 | ||||

| Affective commitment | AC1 | 0.591 | 1.201 | 0.724 | 0.820 | 0.479 |

| AC2 | 0.727 | 1.483 | ||||

| AC3 | 0.794 | 1.571 | ||||

| AC4 | 0.722 | 1.478 | ||||

| AC5 | 0.605 | 1.273 |

Note: CA = Cronbach’s Alpha; CR = Composite Reliability; AVE = Average Variance Extracted.

To assess discriminant validity in this study, Fornell-Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) were used. The square root of the AVE for each construct, as shown in Table 2, was greater than the correlation between that construct and any other construct in the model. Additionally, the HTMT ratio for all of the constructs in the same column and row was less than 1, demonstrating discriminant validity.

Table 2

Discriminant validity

| Constructs | Affective commitment | Moderating effect (SL * WE) | Servant leadership | Work engagement |

| Fornell-Larcker criterion | ||||

| Affective commitment | 0.692 | |||

| Moderating effect (SL * WE) | 0.211 | 1.000 | ||

| Servant leadership | 0.330 | 0.409 | 0.587 | |

| Work engagement | 0.649 | 0.254 | 0.341 | 0.627 |

| Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) | ||||

| Affective commitment | ||||

| Moderating effect (SL * WE) | 0.243 | |||

| Servant leadership | 0.435 | 0.441 | ||

| Work engagement | 0.883 | 0.295 | 0.432 |

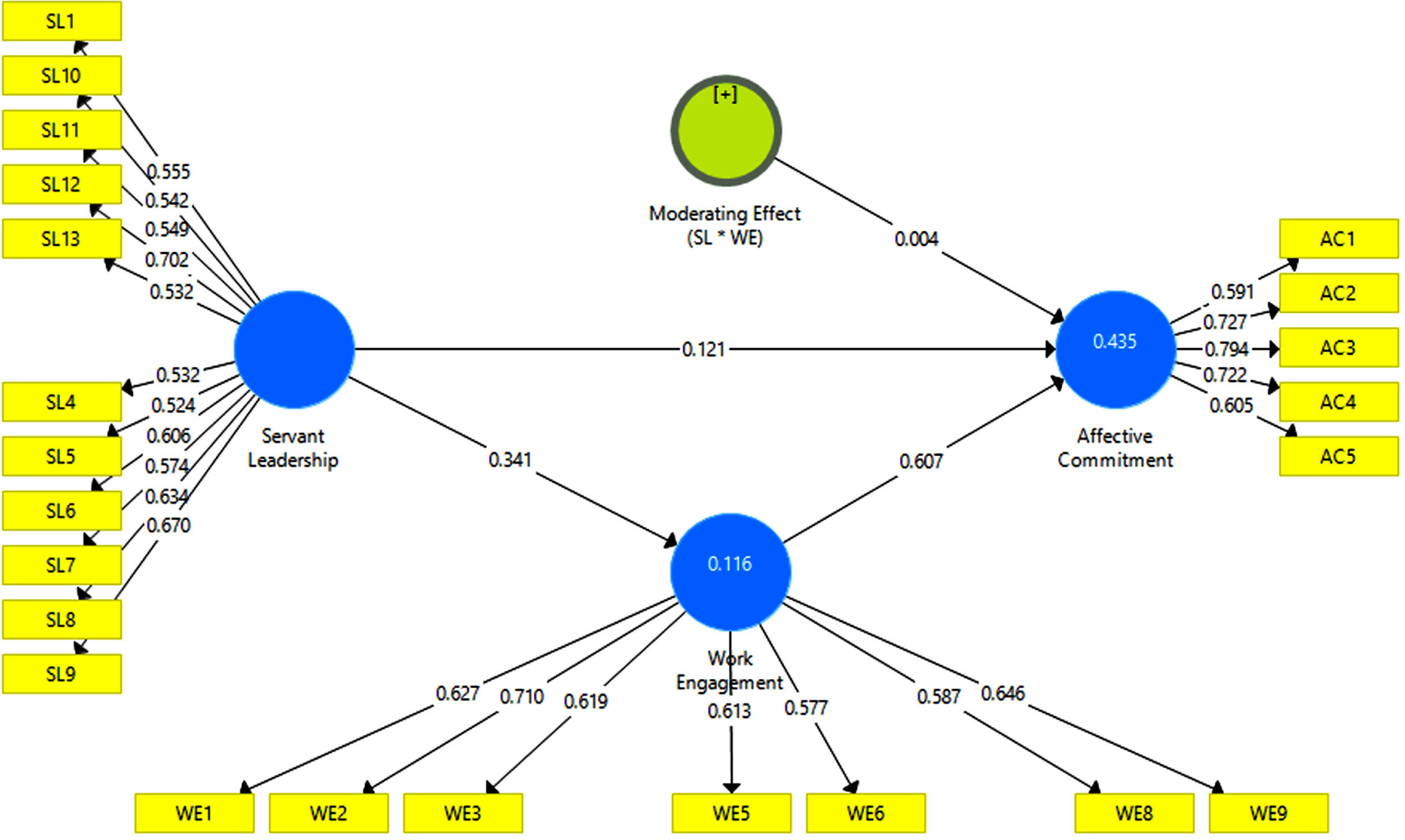

The results of the study in Table 3 and Fig. 1 show that the direct effect of servant leadership on affective commitment is not significant (β= 0.121; SD = 0.099; t-statistics = 1.222; ρ> 0.05), failing to support H1. However, the statistical analysis revealed that servant leadership positively and significantly affects work engagement (β= 0.341; SD = 0.108; t-statistics = 3.157; ρ< 0.05); consequently, H2 is accepted. Additionally, the finding confirmed that work engagement has a positive and significant effect on affective commitment (β= 0.607; SD = 0.069; t-statistics = 8.804; ρ< 0.05); therefore, H3 is supported.

Table 3

Path coefficients

| Hypothesis | β | SD | T Statistics | P Values |

| Direct effects | ||||

| Servant leadership → affective commitment | 0.121 | 0.099 | 1.222 | 0.223 |

| Servant leadership → work engagement | 0.341 | 0.108 | 3.157 | 0.002 |

| Work engagement → affective commitment | 0.607 | 0.069 | 8.804 | 0.000 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Servant leadership → work engagement → affective commitment | 0.207 | 0.072 | 2.874 | 0.004 |

| Moderating effect (SL * WE) → affective commitment | 0.004 | 0.038 | 0.097 | 0.923 |

Note: β= Original Sample; SD = Standard Deviation.

Fig. 1

Research framework.

To verify if work engagement really becomes a mediator and moderator between servant leadership and affective commitment, this study relied on Hayes’ recommendation Hayes [57]. The findings confirmed that the indirect effect of servant leadership on affective commitment through work engagement is significant (β= 0.207; SD = 0.072; t-statistics = 2.874; ρ< 0.05); consequently, H4 is supported. This result indicated that work engagement fully mediates the link between servant leadership and affective commitment. However, the study found no significant effect regarding the moderation effect of work engagement (β= 0.004; SD = 0.038; t-statistics = 0.097; ρ> 0.05). Thus, H5 is unsupported, indicating that work engagement does not moderate the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment.

The results of this study indicated that servant leadership, often praised for its emphasis on serving others, may only sometimes significantly impact affective commitment within an organization. While servant leaders prioritize the needs of their employees and aim to build trust, individual differences, job characteristics and organizational dynamics, also play pivotal roles in shaping affective commitment. In certain organizational cultures where hierarchy and authority are deeply entrenched, servant leadership may face challenges in gaining traction and impacting commitment levels [58]. Additionally, employees’ perceptions of servant leadership behaviors and their alignment with organizational goals can vary, affecting the degree to which affective commitment is influenced [13, 59]. Furthermore, while servant leadership may promote work engagement and employee well-being, these outcomes do not always translate directly into affective commitment. Employees may appreciate servant leadership but still lack a strong emotional connection to the organization, especially if they perceive limited opportunities for recognition, career advancement, or alignment with personal values.

The result also depicted the significant influence of work engagement on affective commitment. Work engagement, characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption in one’s work, plays a crucial role in fostering affective commitment within an organization. In SET, employees who are highly engaged in their work are more likely to experience a sense of fulfillment, purpose, and satisfaction from their roles. This positive emotional state forms the foundation for affective commitment, as employees develop a strong emotional attachment to the organization based on their enjoyment and enthusiasm for their work [39]. Furthermore, engaged employees are more resilient in the face of challenges, maintaining their commitment to the organization even during periods of adversity. Moreover, empirical research consistently demonstrates a positive association between work engagement and affective commitment [40, 60], highlighting the significant impact of work engagement on emotional attachment towards the organization.

The result further demonstrated that work engagement serves as a mechanism through which the positive effects of servant leadership are transmitted to affective commitment. Engaged employees are more likely to experience a strong emotional attachment to the organization, driven by their enthusiasm, dedication, and absorption in their work. Furthermore, servant leaders exemplify values such as empathy and humility, which are conducive to building strong interpersonal relationships and fostering a positive work engagement [37, 61]. In SET, employees who perceive their leaders as caring and authentic are more likely to feel emotionally connected to the organization [4] and committed to its goals. Moreover, empirical research supports the mediating role of work engagement [62, 63] in the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment, highlighting the importance of fostering employee engagement as a pathway to enhancing organizational commitment.

The result also revealed that while work engagement undoubtedly plays a crucial role in influencing affective commitment, it may not always be a moderator in the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment. For these reasons, firstly, work engagement is not solely determined by servant leadership but is also influenced by various individual and organizational factors, such as job characteristics, personal values, and organizational dynamics. While servant leadership may create a conducive environment for fostering work engagement [37], other factors may mitigate or enhance its effects on affective commitment independently of work engagement. Secondly, servant leaders, by virtue of their empathetic and supportive behaviors, foster employees to invest cognitively and emotionally in their tasks [64], leading to high levels of work engagement irrespective of individual differences in affective commitment.

6Conclusion

The results of the study show that servant leadership has no significant effect on affective commitment, but significant on work engagement. Additionally, the finding confirmed that work engagement has a significant effect on affective commitment. Furthermore, the findings indicated that work engagement fully mediates the link between servant leadership and affective commitment. However, regarding the moderation effect, work engagement does not moderate the relationship between servant leadership and affective commitment.

Servant leadership, rooted in the philosophy of serving others first, is theorized to have a significant impact on work engagement through the lens of SET. According to SET, employees engage in reciprocal relationships where they exchange resources [18], such as support, trust, and respect, with their leaders. Servant leaders, by prioritizing the needs and development of their employees, foster a supportive work environment characterized by trust and empowerment. In return, employees reciprocate by investing more effort and energy into their work, leading to higher levels of work engagement.

The theoretical and practical implications of this relationship are profound. Firstly, servant leadership can be seen as a facilitator of positive social exchanges within the workplace. By emphasizing altruism and empathy, servant leaders cultivate a culture of reciprocity and mutual trust [17], which are fundamental to the exchange of resources among employees. Moreover, servant leaders inspire their employees by empowering them, providing meaningful work, and fostering personal growth and development. As a result, employees feel a stronger sense of fulfillment in their roles, leading to heightened levels of work engagement. Therefore, this highlights the importance of servant leadership in shaping the social dynamics of the workplace and influencing employee attitudes and behaviors.

One limitation of this study is the potential for common method bias and response bias due to the reliance on self-reported data. The study’s narrow focus on a specific industry and region may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader contexts. Additionally, the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to establish causal relationships between servant leadership, affective commitment, and work engagement. Therefore, future research could benefit from longitudinal studies to establish causality between servant leadership, affective commitment, and work engagement. Exploring the moderating role of contextual factors, such as organizational ambidexterity or industry type, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of these relationships. Moreover, investigating the influence of individual differences, such as personality traits, on the effectiveness of servant leadership in promoting affective commitment and work engagement would offer valuable insights. Additionally, exploring the impact of alternative leadership styles such as agile, authentic, and inclusive leadership on affective commitment and work engagement could provide a comparative perspective on the effectiveness of servant leadership.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the Mahasarakham University for financially supporting this research project. Additionally, we are immensely grateful to Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta for co-sponsoring our paper and providing the encouragement needed to complete this project.

Author contributions

CONCEPTION: Udin Udin and Suteera Chantes.

DATA COLLECTION: Udin Udin and Radyan Dananjoyo.

INTERPRETATION OR ANALYSIS OF DATA: Udin Udin and Radyan Dananjoyo.

PREPARATION OF THE MANUSCRIPT: Udin Udin and Radyan Dananjoyo.

REVISION FOR IMPORTANT INTELLECTUAL CONTENT: Udin Udin and Suteera Chantes.

SUPERVISION: Radyan Dananjoyo and Suteera Chantes.

References

[1] | Hussain A , Asif M , Jameel A , Hwang J , Sahito N , Kanwel S . Promoting OPD Patient Satisfaction through Different Healthcare Determinants: A Study of Public Sector Hospitals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [Internet]. (2019) ;16: (19). DOI: 10.3390/ijerph16193719. |

[2] | Bel G , Esteve M . Is Private Production of Hospital Services Cheaper than Public Production? A Meta-Regression of Public Versus Private Costs and Efficiency for Hospitals. International Public Management Journal. (2020) ;23: (1):1–24. DOI: 10.1080/10967494.2019.1622613. |

[3] | Simon E , Mathew AN , Thomas VV . Demonstrating Servant Leadership During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Christian nursing: a quarterly publication of Nurses Christian Fellowship. (2022) ;39: (4):258–62. DOI: 10.1097/CNJ.0000000000001002. |

[4] | Udin U , Rakasiwi G , Dananjoyo R . Servant leadership and work engagement: Exploring the mediation role of affective commitment and job satisfaction. International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management. (2024) ;9: (2):205–16. DOI: 10.22034/ijhcum.2024.02.01. |

[5] | Mustard RW . Servant Leadership in the Veterans Health Administration. Nurse Leader. (2020) ;18: (2):178–80. DOI: 10.1016/j.mnl.2019.03.019. |

[6] | Mostafa AMS , El-Motalib EAA . Servant Leadership, Leader– Member Exchange and Proactive Behavior in the Public Health Sector. Public Personnel Management. (2019) ;48: (3):309–24. DOI: 10.1177/0091026018816340. |

[7] | Bai M , Zheng X , Huang X , Jing T , Yu C , Li S , Zhang Z . How serving helps leading: mediators between servant leadership and affective commitment. Front Psychol. (2023) ;14: :1170490. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1170490. |

[8] | Aboramadan M , Dahleez K , Hamad MH . Servant leadership and academics outcomes in higher education: the role of job satisfaction. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. (2021) ;29: (3):562–84. DOI: 10.1108/IJOA-11-2019-1923. |

[9] | Dahleez KA , Aboramadan M , Bansal A . Servant leadership and affective commitment: the role of psychological ownership and person– organization fit. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. (2021) ;29: (2):493–511. DOI: 10.1108/IJOA-03-2020-2105. |

[10] | Ghasemy M , Frömbling L . A conditional time-varying multivariate latent growth curve model for therelationships between academics’ servant leadership behavior, affective commitment, and job performance duringthe Covid-19 pandemic. Quality & Quantity. (2022) . DOI: 10.1007/s11135-022-01568-6. |

[11] | Ngah NS , Abdullah NL , Mohd Suki N , Kasim MA Does servant leadership affect organisational citizenship behaviour? Mediating role of affective commitment and moderating role of role identity of young volunteers in non-profit organisations. Leadersh Organ Dev J. (2023) ;44: (6):681–701. DOI: 10.1108/LODJ-11-2022-0484. |

[12] | Franco M , Antunes A . Understanding servant leadership dimensions. Nankai Business Review International. (2020) ;11: (3):345–69. DOI: 10.1108/NBRI-08-2019-0038. |

[13] | Clarence M , Devassy VP , Jena LK , George TS . The effect of servant leadership on ad hoc schoolteachers’ affective commitment and psychological well-being: The mediating role of psychological capital. International Review of Education. (2021) ;67: (3):305–31. DOI: 10.1007/s11159-020-09856-9. |

[14] | Sadikin F , Tecualu M , Desy E , editors The Effect of Servant Leadership and Work Engagement on Organizational Citizenship Behavior Mediated by Organizational Commitment on Volunteers in Abbalove Ministries Church. 8th International Conference of Entrepreneurship and Business Management Untar (ICEBM 2019); (2020) : Atlantis Press. |

[15] | Joo B-KB , Byun S , Jang S , Lee I . Servant leadership, commitment, and participatory behaviors in Korean Catholic church. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion. (2018) ;15: (4):325–48. DOI: 10.1080/14766086.2018.1479654. |

[16] | Irawanto D , Mu’ammal I . The Effect of Volunteer and Servant Leadership Motivation on Organizational Commitments Mediated by Volunteer Satisfaction: Evidence from Indonesian Sports Student Activity Unit. International Journal of Intellectual Human Resource Management. (2020) ;1: (2):1–8. DOI: 10.46988/IJIHRM.01.02.2020.001. |

[17] | Cropanzano R , Anthony EL , Daniels SR , Hall AV . Social Exchange Theory: A Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Academy of Management Annals. (2017) ;11: (1):479–516. DOI: 10.5465/annals.2015.0099. |

[18] | Blau P . Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley; 1964. |

[19] | Cook KS , Cheshire C , Rice ERW , Nakagawa S . Social Exchange Theory. In: DeLamater J, Ward A, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; (2013) . p. 61–88. DOI: 10.1007/978-94-007-6772-0_3. |

[20] | Meyer JP , Allen NJ , Smith CA . Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology. (1993) ;78: (4):538–51. DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538. |

[21] | Udin U , Dananjoyo R , Shaikh M , Vio Linarta D . Islamic Work Ethics, Affective Commitment, and Employee’s Performance in Family Business: Testing Their Relationships. SAGE Open. (2022) ;12: (1): DOI: 10.1177/21582440221085263. |

[22] | Chernyak-Hai L , Bareket-Bojmel L , Margalit M . A matter of hope: Perceived support, hope, affective commitment, and citizenship behavior in organizations. European Management Journal. (2023) . DOI: 10.1016/j.emj.2023.03.003. |

[23] | Yuniawan A , Udin U . The Influence of Knowledge Sharing, Affective Commitment, and Meaningful Work on Employee‘s Performance. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration. (2020) ;8: (3):72–82. DOI: 10.35808/ijeba/487. |

[24] | Schaufeli WB , Bakker AB . Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior. (2004) ;25: (3):293–315. DOI: 10.1002/job.248. |

[25] | Abualigah A , Darwish TK , Davies J , Haq M , Ahmad SZ . Supervisor support, religiosity, work engagement, and affective commitment: evidence from a Middle Eastern emerging market. Journal of Asia Business Studies. (2023) ;ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). DOI: 10.1108/JABS-11-2022-0394. |

[26] | Mazzetti G , Robledo E , Vignoli M , Topa G , Guglielmi D , Schaufeli WB . Work Engagement: A meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands-Resources Model. Psychological Reports. (2023) ;126: (3):1069–107. DOI: 10.1177/00332941211051988. |

[27] | Greenleaf RK . The servant as leader. Indianapolis: The Robert Greenleaf Center; 1970. |

[28] | D’Ascoli S , Piro JS . Educational Servant-Leaders and Personal Growth. Journal of School Leadership. (2023) ;33: (1):26–49. DOI: 10.1177/10526846221134001. |

[29] | Jaramillo F , Bande B , Varela J . Servant leadership and ethics: a dyadic examination of supervisor behaviors and salesperson perceptions. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management. (2015) ;35: (2):108–24. DOI: 10.1080/08853134.2015.1010539. |

[30] | van Dierendonck D . Servant Leadership: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of Management. (2011) ;37: (4):1228–61. DOI: 10.1177/0149206310380462. |

[31] | Andrade MS . Servant leadership: developing others and addressing gender inequities. Strategic HR Review. (2023) ;22: (2):52–7. DOI: 10.1108/SHR-06-2022-0032. |

[32] | Amah OE , Oyetunde K . The effect of servant leadership on employee turnover in SMEs: the role of career growth potential and employee voice. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business. (2023) ;48: (4):432–53. DOI: 10.1504/ijesb.2023.130830. |

[33] | Miao Q , Newman A , Schwarz G , Xu L . Servant Leadership, Trust, And The Organizational Commitment Of Public Sector Employees In China. Public Administration. (2014) ;92: (3):727–43. DOI: 10.1111/padm.12091. |

[34] | Newman A , Neesham C , Manville G , Tse HHM . Examining the influence of servant and entrepreneurial leadership on the work outcomes of employees in social enterprises. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. (2018) ;29: (20):2905–26. DOI: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1359792. |

[35] | Parris DL , Peachey JW . A Systematic Literature Review of Servant Leadership Theory in Organizational Contexts. Journal of Business Ethics. (2013) ;113: (3):377–93. DOI: 10.1007/s10551-012-1322-6. |

[36] | Bao Y , Li C , Zhao H . Servant leadership and engagement: a dual mediation model. Journal of Managerial Psychology. (2018) ;33: (6):406–17. DOI: 10.1108/JMP-12-2017-0435. |

[37] | Zhou G , Gul R , Tufail M . Does servant leadership stimulate work engagement? The moderating role of trust in the leader. Frontiers in Psychology. (2022) ;13: :925732. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.925732. |

[38] | Hakanen JJ , Seppälä P , Peeters MCW . High Job Demands, Still Engaged and Not Burned Out? The Role of Job Crafting. International journal of behavioral medicine. (2017) ;24: (4):619–27. DOI: 10.1007/s12529-017-9638-3. |

[39] | Ampofo ET . Mediation effects of job satisfaction and work engagement on the relationship between organisational embeddedness and affective commitment among frontline employees of star– rated hotels in Accra. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. (2020) ;44: :253–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.06.002. |

[40] | Nagpal P . Organizational commitment as an outcome of employee engagement: A social exchange perceptive using a SEM model. International Journal of Biology, Pharmacy and Allied Sciences. (2022) ;11: (1):72–86. DOI: 10.31032/IJBPAS/2022/11.1.1008. |

[41] | Bakker AB , Leiter MP . Where to go from here: Integration and future research on work engagement. In: Bakker AB, Leiter MP, editors. Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research. New York, NY: Psychology Press; (2010) . p. 181–96. |

[42] | Aseanty D , Andreas A , Lutfiyani I , editors. The Effect of Servant Leadership on Work Engagement and Affective Commitment Mediated by Job Satisfaction on Education Staff at Private Universities in West Jakarta. First Lekantara Annual Conference on Public Administration, Literature, Social Sciences, Humanities, and Education; (2022) : European Alliance for Innovation. |

[43] | Liden RC , Wayne SJ , Liao C , Meuser JD . Servant Leadership and Serving Culture: Influence on Individual and Unit Performance. Academy of Management Journal. (2014) ;57: (5):1434–52. DOI: 10.5465/amj.2013.0034. |

[44] | Aboramadan M , Hamid Z , Kundi YM , El Hamalawi E . The effect of servant leadership on employees’ extra-role behaviors in NPOs: The role of work engagement. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. (2022) ;33: (1):109–29. DOI: 10.1002/nml.21505. |

[45] | Carter D , Baghurst T . The Influence of Servant Leadership on Restaurant Employee Engagement. Journal of Business Ethics. (2014) ;124: (3):453–64. DOI: 10.1007/s10551-013-1882-0. |

[46] | Jaramillo F , Grisaffe DB , Chonko LB , Roberts JA . Examining the Impact of Servant Leadership on Sales Force Performance. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management. (2009) ;29: (3):257–75. DOI: 10.2753/PSS0885-3134290304. |

[47] | Choudhary AI , Akhtar SA , Zaheer A . Impact of Transformational and Servant Leadership on Organizational Performance: A Comparative Analysis. Journal of Business Ethics. (2013) ;116: (2):433–40. DOI: 10.1007/s10551-012-1470-8. |

[48] | Fletcher L . Training perceptions, engagement, and performance: comparing work engagement and personal role engagement. Human Resource Development International. (2016) ;19: (1):4–26. DOI: 10.1080/13678868.2015.1067855. |

[49] | Udin U , Dananjoyo R , Isalman I . The Effect of Transactional Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior: Testing the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Work Engagement as Mediation Variables. International Journal of Sustainable Development & Planning. (2022) ;17: (3):727–36. DOI: 10.18280/ijsd170303. |

[50] | Vandenberghe C , Bentein K , Stinglhamber F . Affective commitment to the organization, supervisor, and work group: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior. (2004) ;64: (1):47–71. DOI: 10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00029-0. |

[51] | Astuty I , Udin U . The Effect of Perceived Organizational Support and Transformational Leadership on Affective Commitment and Employee Performance. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business. (2020) ;7: (10):401–11. DOI: 10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no10.401. |

[52] | Sarstedt M , Ringle CM , Smith D , Reams R , Hair JF . Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy. (2014) ;5: (1):105–15. DOI: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.01.002. |

[53] | Hair JF , Risher JJ , Sarstedt M , Ringle CM . When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review. (2019) ;31: (1):2–24. DOI: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203. |

[54] | Hair JF , Sarstedt M , Hopkins L , G Kuppelwieser V . Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European Business Review. (2014) ;26: (2):106–21. DOI: 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128. |

[55] | Chin WW . Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Quarterly. (1998) ;22: (1), 7–16. |

[56] | Fornell C , Larcker DF . Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research. (1981) ;18: (3):382–8. DOI: 10.1177/002224378101800313. |

[57] | Hayes AF . Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis a regression-based approach. New York City Guilford Press; 2013. |

[58] | Miao Q , Newman A , Schwarz G , Xu LIN . Servant Leadership, Trust, And The Organizational Commitment Of Public Sector Employees In China. Public Administration. (2014) ;92: (3):727–43. DOI: 10.1111/padm.12091. |

[59] | McCune Stein A , Ai Min Y . The dynamic interaction between high-commitment HRM and servant leadership. Manage Res Rev. (2019) ;42: (10):1169–86.. DOI: 10.1108/MRR-02-2018-0083. |

[60] | Orgambídez A , Benítez M . Understanding the link between work engagement and affective organisationalcommitment: The moderating effect of role stress. International Journal of Psychology. (2021) ;56: (5):791–800. DOI: 10.1002/ijo12741. |

[61] | Eva N , Robin M , Sendjaya S , van Dierendonck D , Liden RC . Servant Leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly. (2019) ;30: (1):111–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004. |

[62] | Ozturk A , Karatepe OM , Okumus F . The effect of servant leadership on hotel employees’ behavioral consequences: Work engagement versus job satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management. (2021) ;97: :102994. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102994. |

[63] | Kaya B , Karatepe OM . Does servant leadership better explain work engagement, career satisfaction and adaptive performance than authentic leadership? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. (2020) ;32: (6):2075–95. DOI: 10.1108/IJCHM-05-2019-0438. |

[64] | Nauman S , Musawir AU , Malik SZ , Munir H . Servant Leadership and Project Success: Unleashing the Missing Links of Work Engagement, Project Work Withdrawal, and Project Identification. Project Management Journal. (2022) ;53: (3):257–76. DOI: 10.1177/87569728221087161. |