Organizational configurations in a crisis context: what archetypes in times of COVID-19 crisis?

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

We only believe the components of our study, namely: the subject (the organizational configuration), the circumstance (COVID-19), and the context (Tunisia) together constitute the originality of our research. Indeed, to our knowledge, no study has been carried out so far on the typical configurations for managing the COVID-19 crisis in a Tunisian context. We think, therefore, that we are the first to do so.

OBJECTIVE:

In a context of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis which is currently affecting our planet and which has had a huge impact on all levels (health, economic and social), our research seeks make a further contribution to the study of organizational configurations or archetypes in the field of crisis management. More specifically, our research principally aims, on the one hand, to describe the forms taken by organizations when they are facing a crisis of great magnitude such as - the COVID-19 crisis - and on the other hand, to identify a taxonomy making it possible to highlight the recurring axes of action on which the actors rely to manage a crisis.

METHODS:

Our methodological framework is based on the phenomenological paradigm in the human sciences which integrates the meaning given by man to the world around him [1] and which takes into account the subjectivity of the actors. Our positioning in favor of the phenomenological paradigm leads to the adoption of a qualitative research method. At this level, we carried out twenty-four semi-structured interviews in twenty Tunisian companies that were able to resist during the pandemic COVID-19 crisis and have managed to last at least until the present day.

RESULTS:

We identified three archetypes on the basis of five organizational factors that we inspired from the onion model of [2] and qualified it as configuration “determinants”, namely: strategy, structure, culture, leadership, and people. These archetypes are: the humanist communitarian, the perfectionist mobilizer, and the incrementalist pragmatic.

CONCLUSIONS:

We therefore believe that our research has enriched the configurational perspective by defining archetypes capable of managing a major crisis such as the COVID-19 crisis. The archetypes thus identified in our study may constitute typical models to be followed by companies wishing to resist the health crisis that is not yet over and whose repercussions can last for a long time.

Bechir Mokline has a PHD in Management. Currently, he is an assistant professor at the private Ibn Khaldoun University in Tunisia. He has several publications, the most important of which are: Mokline B, Ben Abdallah MA. The Mechanisms of Collective Resilience in a Crisis Context: the Case of the ‘COVID-19’ Crisis. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. 2021. DOI: 10.1007/s40171-021-00293-7. Mokline B, Ben Abdallah MA. Individual Resilience in the Organization in the Face of Crisis: Study of the Concept in the Context of COVID-19. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. 2021;22(3):219-231. DOI: 10.1007/s40171-021-00273-x

Bechir Mokline has a PHD in Management. Currently, he is an assistant professor at the private Ibn Khaldoun University in Tunisia. He has several publications, the most important of which are: Mokline B, Ben Abdallah MA. The Mechanisms of Collective Resilience in a Crisis Context: the Case of the ‘COVID-19’ Crisis. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. 2021. DOI: 10.1007/s40171-021-00293-7. Mokline B, Ben Abdallah MA. Individual Resilience in the Organization in the Face of Crisis: Study of the Concept in the Context of COVID-19. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. 2021;22(3):219-231. DOI: 10.1007/s40171-021-00273-x

1Introduction

The pandemic COVID-19 crisis that is currently affecting our world has had a huge impact at all levels (health, economic and social) beyond the simple spread of the disease and containment measures. The consequences of this crisis could have a lasting impact on companies and pushed them to reconsider the foundations of their organizations [3].

The COVID-19 pandemic has revived more debates and reflections on the need to overhaul managerial practices and organizational models in times of crisis in order to ensure the survival of companies in a context of adversity [4].

All these structures, to varying degrees, are impacted by a crisis that was not considered in their strategic analyses. Are we entering unknown territories? Should we rethink our certainties and benchmarks relating to management methods? This crisis revealed managerial deficits; it was the revelation of it, which necessitates a revision of the approaches. Is it therefore appropriate to erect a new model?

Several authors in the literature consider that crises, given their destabilizing nature, constitute well-defined episodes [5] allowing a new configuration to be defined [6, 7].

Moreover, few of them have, described the configurations adopted by organizations when they face a crisis [8, 9]. Our research thus aims to contribute to enriching knowledge on this point.

In addition, the research on configuration that has been carried out so far has focused on the organizations that cause or provoke crises [2, 7]. However, the particular contribution that we wish to make in our research relates to organizations which have suffered (in a forced way) a global crisis of great magnitude - such as the COVID-19 crisis - and have been able to survive during these first three waves of the Coronavirus pandemic.

The thrust of this study is to know, how or in what way, these organizations were able to manage this health crisis and, as a corollary, to examine what effects their strategic choices have on crisis management, in particular, on maintaining or exceeding the routines already established. Therefore, we want to circumscribe the way of proceeding at the base of strategic choices in an environment of crisis characterized by strong turbulence and a high degree of uncertainty.

Therefore, our research aims to study the organizational configurations or archetypes in the field of crisis management on the basis of determinants or organizational factors inspired by the onion model of [2] and identified in our conceptual model, that is, strategy, structure, culture, leadership, and individuals. Hence, our main concern is, on the one hand, to describe the forms taken by organizations when they are facing a crisis of a great magnitude such as - the COVID-19 crisis - and on the other hand, to identify a taxonomy allowing highlighting the recurring axes of action on which the actors rely to manage a crisis.

More precisely, our research aims to provide answers to the following questions: what are the most favorable “typical” configurations for managing the crisis, more specifically the Covid- 19 crisis? What taxonomy can we derive from the experiences and accounts of the actors involved in this context of health crisis?

Our methodological framework is based on the phenomenological paradigm in the human sciences which integrates the meaning given by man to the world around him [1] while taking into account the subjectivity of the actors. Our positioning in favor of the latter paradigm leads to the adoption of a qualitative research method. At this level, we carried out twenty- four semi-structured interviews in twenty Tunisian companies that were able to resist during the pandemic COVID-19 crisis and have managed to last at least until the present day.

The methodology consists in establishing a content analysis of the actors operating in multiple cases. The latter was based on the search for common dimensions between the cases and on the dynamic interrelation of these dimensions between them.

This research has four sections. In the first section, we expose the two main structuring approaches during a crisis, namely the contingency approach and the configurational approach. We also explain our positioning based on the configurational perspective. In the second section, we explain our conceptual framework. In the third and fourth sections, we present respectively the methodological framework of the research as well as the data collection protocol. In the fifth section, we present our research results. At this level, we present the three archetypes of crisis management that we have been able to identify through our empirical study. These archetypes are: the humanist communitarian, the perfectionist mobilizer, and the incrementalist pragmatic. We conclude this work by discussion the various contributions and implications on the research level, the limits, and finally future avenues of research.

2Structuring of organizations during a crisis

defines an organization as “a collection of people who seek to make sense of what is going on around them”. During a crisis, individuals with various functions, structures and jurisdictions will interact according to common interests [10] and this, towards a common goal: to limit and manage the crisis, thus generating what sociologists call “Organized action” [11].

[12, p.20] define the crisis as “Consecutive to a proven disruption of the balance of the fundamentals of one or more organizational systems. A crisis situation is observed by a state of profound disorders of its actors and / or organizational disintegration, involving damage and generating the necessary immediate decision-making and different actions in a context of ambiguities and uncertainties. All influenced by a constrained temporal mesh “.

Thus, organizations that are projected into a crisis are generally led to adopt different routines and structure themselves according to the situation. The theory of contingency, on the one hand, and the configurational approach of organizations on the other hand, provide some answers to understand how organizations are structured during a crisis.

2.1The contingent approach

Understanding the response of organizations during a crisis requires a convergence of organizational theories and behavioral theories [13].

The organizations affected by the crisis differ in terms of their missions, responsibilities, structural configurations and skills [14]. Theorists summarize this position with the slogan “it all depends” [14].

The responses of organizations are conditioned both by the antecedents to crises but also by contingency factors relating to the triggering event and to the structures [8].

Table 1 summarizes these responses.

Table 1

Parameters influencing the behavior of organizations before and during the onset of the crisis

| Crisis antecedents | Behavior during crises |

| 1. Missions (routine activities or no) | 1. Development of coalition strategies: |

| 2. The context of action: factors of vulnerability: | - Struggle to have the resources; |

| - Previous experience; | - Responsive behavior |

| - Skill levels; | - Development of structures specific to crisis management (crisis unit, centralization of decision-making, etc.) |

| - Levels of employee involvement and motivation; | 2. The structure: |

| - The degree of complexity of the network organizational; | - Age; |

| - The resources available. | - The size; |

| - The technical system; | |

| - The environment; | |

| - Power relations. |

([22]).

The contingency approach obviously allows us to fully understand the factors that intervene during a crisis. However, this approach excludes the role of the manager and the notion of strategic choice and decisions [15]. As a result, this approach corresponds to a certain environmental determinism which removes the human construct from our understanding of the functioning of organizations, and which tends to conceive the company as a passive reactor in the face of an environment that dictates tasks and a single well-defined structure [6].

In short, the literature on organizational contingencies is often too focused on contextual variables that can vary organizations’ responses to a crisis but fail to identify the most adequate structures allowing organizations to survive in a context of adversity.

2.2The configurational approach

Contingency theories do not take into account that there appears to be a limited number of organizational structures in nature [6]. However, they deny the principle of equifinality, namely that several models or configurations can be viable for the same context, a principle that is found at the heart of the configuration school [16, 17]. Thus [6] ask: how it is that two companies can operate successfully in a similar environment by applying different strategies? Consequently, unlike the contingency approach, the configurational perspective considers rather that the organizational structure, its environment, its production system, its strategy, its information processing procedures and its decision-making processes influence each other to form, in nature, only a limited number of configurations, gestalts, or archetypes.

The slogan associated with this perspective is “it all comes together” [18]. The number of configurations is limited by the tendency of the attributes of an organization to organize itself according to coherent patterns [5]. These patterns exist because the attributes of organizations are interdependent and they only change by “quantum leap”. Consequently, there is only a limited number of types of organization that are viable and can be observed empirically [5].

The configurations can take the form of either a typology or taxonomy. Typologies are not based on an empirical but conceptual basis, i.e. they are a priori constructions that the researcher constructs on the basis of his personal experiences or his intuitions [19]. This is how the typology is deduced from a qualitative or theoretical basis [20]. The second approach, induced from empiricism on the basis of the application of quantitative analytical techniques, seeks to discover taxonomies from the observation of a population of organizations [19].

Using empirical and inductive data, researchers who adopt this approach attempt to find groupings of organizations using factor analyzes of variables that characterize their structure [20].

The configuration approach, by its synthetic nature [6], seems particularly appropriate to produce or generate these organizational archetypes in crisis management. We believe, in fact, that it is an integrative approach that would allow us to take into account the organizational factors, most essential to crisis management.

2.3Defining elements

In configurational theory, the concepts of configuration, archetypes, or gestalts are often used in a relatively undifferentiated way to translate “constellations of coherent and strongly interrelated elements” [16]. These configurations tend to become stable over time, unless changes are drastic enough to force them to change [6]. In our research, we opt rather for the term ‘archetype’.

[21, p.264] define the archetype as a set of relationships between several characteristics of the firm in a temporary state of equilibrium:

⪡ Archetypes synthesize the relationship between several characteristics of the business that are in a state of temporary equilibrium. The temporal element plays a vital role in the constitution of these archetypes (...) Concrete instances and administrative situations are also used to describe structural attributes and concrete events. ⪢.

2.4Conditions favorable to the development of organizational configurations adapted to the crisis context

We note from the literature three conditions that must be met to successfully reconfigure organizations when they face crisis situations: the destabilizing aspect of the crisis as a lever for change, adaptation and transformation of the organization, and resilience and learning capacity.

2.5The destabilizing aspect of the crisis as a lever for change

Crisis events are characterized by unforeseeable circumstances; moments of disruption and uncertainty which can act as an indicator of latent elements in the daily life of organizations or even as an exogenous “effector", due to its power of change [22].

There is a consensus that a certain imbalance is necessary for an organization to modify the normal course of its actions [23–25].

Fluctuations introduced by the organization’s interaction with the environment can generate “creative chaos” [3, 23]. Creative chaos generates tension in order to envision new solutions to new problems. But for chaos to remain creative and not to become destructive, certain reflexivity must prevail over actions [26].

2.6Adaptation and transformation of the organization

There is a debate in the literature on the transformations that take place within organizations when a crisis occurs. Thus, some authors like [27] and [28] assert, on the basis of a hundred studies conducted with numerous organizations corresponding to the Weberian model of bureaucracy, that these organizations become debureaucratized in a crisis situation by setting up new structures and rules of operation.

[29] note that important changes occur in bureaucratic-type organizations in times of crisis: decision-making becomes more centralized, informal rules and improvisation become the manual, games policies abound, with policy-makers preferring to rely on sources in which they have personal confidence. Finally, the speed and volume of communications are increasing at a phenomenal rate.

[30] identify four structural adaptation processes likely to be adopted by bureaucratic-type organizations during crises. We present them in the following table (Table 2).

Table 2

The four structural adaptation processes adopted by bureaucratic-type organizations during crises

| Model type | Adaptation process |

| Incremental model | - An adaptation that reveals more continuity than change. |

| - The objective is to ensure the continuity of the usual activities of the organization but with little change in decision-making methods. | |

| Restructuring model | - The organization tends to adjust its positioning to the context. |

| - It establishes a change in the structure of these functional units only, but not a change in the tasks and responsibilities of individuals. | |

| Reassignment model | - Adaptation refers to a change in tasks but not to a change in the general structure of operation. |

| - The organization asks people to perform tasks or activities that they are not used to doing normally. | |

| Reconsideration model | - Adaptation involves a change both in structure and in tasks. |

| - This is a major repositioning. |

([7]).

2.7Capacity for resilience and learning

The sustainability of the organization depends crucially on its ability to withstand sudden changes and crises. Here we are getting closer to the concept of resilience which, in management, is extremely recent [28]. Originally, resilience is the ability of a material to be both elastic and resistant to impact. In our analysis, it is the organization that will deform during the shock to return to a new stable state by behaving like an adaptive system enriching its internal complexity to cope with the increasing complexity of the environment [4].

[31] assert that the notions of resilience and learning are inseparable when they are developed at the organizational level. We therefore find the concept of “learning organization” developed for the company by [32]. The organization has no choice but to be resilient facing a crisis [4]. This resilience process includes a learning phase that allows the organization to reshape itself during the crisis phase, a phase during which the organization will acquire and implement new skills [31]. It will emerge a winner from this experience since it should have acquired new knowledge that will allow it, among other things, to distinguish future signals of a new crisis [32].

3The determinants of the onion model in crisis management at the base of our conceptual model

The organizational analysis model illustrated by the metaphor of the “onion model” of [1] corresponds to a complex system because on the one hand, etymologically speaking, “complexity” means “woven of folds”, referring to the onion case. We are therefore talking about a system “woven of folds", that represents the complexity of a system which is effectively composed of several overlapping levels, of which we do not necessarily see the starting line of that of the thin ones and whose access is difficult to identify, like an onion [1]. This onion model is therefore composed of four levels namely: culture, structure, strategy, and individuals.

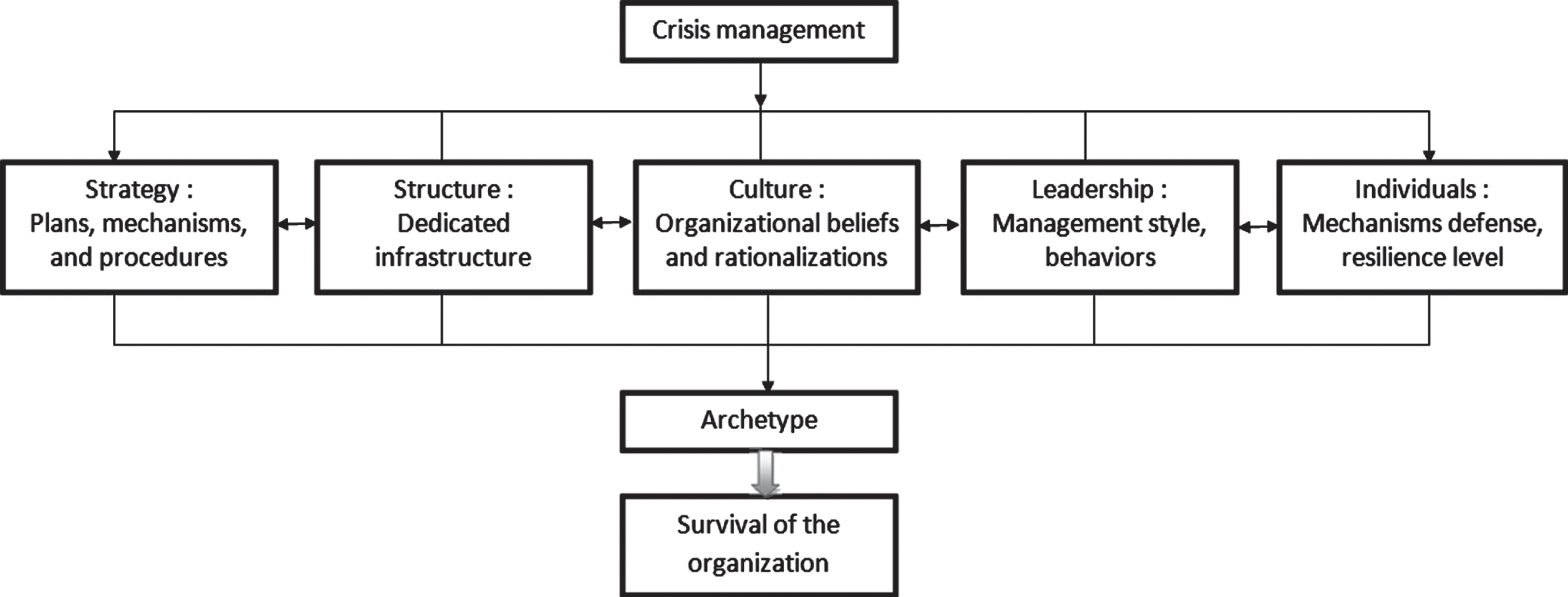

These levels are considered as organizational factors or driving forces, each of which has a managerial assessment instrument for managers in order to set up a crisis management plan. The Fig. 1 shows this onion model.

We use these four forces to build our conceptual model. However, we add a fifth such as leadership which we consider, like [19], to be an essential factor in defining a configuration.

Figure 2 shows the conceptual framework based on the success factors of crisis management that we qualify as configuration determinants. The main idea is that the crisis management process is a system made up of interrelated variables. Thus, the five determinants of crisis management such as culture, structure, strategy, leadership and individuals inspired by the onion model and which condition the definition of a configuration could influence each other and create an effective archetype which would have for result the survival of the organization in times of crisis.

Fig. 2

Conceptual model of organizational configuration in crisis management.

4Research methodology

4.1Research design and setting

Our research methodology is based on the phenomenological paradigm which integrates the meaning given by man to what surrounds him is right in the human world [1]. This paradigm has allowed us to adopt an interpretive approach in the sense that we rely on the representations and points of view of the actors most directly involved in crisis intervention. We were therefore led to opt for the qualitative approach. It is a methodology that allows us to understand social processes by looking at how people and social groups experience them [33]. The semi-structured interview was the main data collection technique used in our research protocol. This technique allows more direct access to the perceptual representation systems specific to each of the subjects interviewed. “Interviews provide access to the conscious or unconscious mental universe of individuals” [34, p. 235].

We have chosen to interview people belonging to all hierarchical levels (executives, managers - executives, and non-executive employees) who have experienced the COVID-19 crisis in the companies where they work, in order to have access to a diversity of viewpoints [35] and also avoid elite bias [36].

Twenty-four interviews were conducted over a period of more than four months from April 2021 to July 2021 with an average duration of 45 minutes with each. We believe that the number of interviews carried out satisfies the theoretical saturation principle recommended by [37]. The interview guide themes were oriented around five determinants of the configuration of our conceptual model and also on the presentation of the company and the profile of the interviewees. These interviews were carried out in twelve large and medium-sized companies listed on the stock exchange, which were able to last in the first three waves of the COVID-19 crisis and managed to ensure their survival at least until today. The choice of these companies is explained by a requirement of transparency and representativeness. Indeed, Tunisian law requires listed companies to disclose monthly reports on their activity. For example, the companies in our sample stated that they carried out crisis plans and disseminated their pandemic crisis management policies in their reports. We believe, therefore, that these companies represent “typical” models that are potentially worthy of study.

Table 3 summarizes our sample.

Table 3

The characteristics of the sample

| Cases | Activity | Work-force | Interviewed | Duration of the interview | |

| C1 | Agribusiness | 920 | General Manager | I1 | 38 min |

| Sustainable Development Manager | I2 | 40 min | |||

| Chief Operating Officer | I3 | 49 min | |||

| C2 | Pharmaceutical | 680 | Deputy General Director | I4 | 45 min |

| Quality, Safety and Environment Manager | I5 | 46 min | |||

| Sales agent | I6 | 60 min | |||

| C3 | Cosmetic | 600 | CSR Manager | I7 | 52 min |

| Laboratory Technician | I8 | 45 min | |||

| C4 | Insurance | 550 | Chairman and CEO | I9 | 41 min |

| Communication Manager | I10 | 55 min | |||

| C5 | Tourism and hotel | 500 | Hygiene and environment Manager | I11 | 36 min |

| Worker | I12 | 35 min | |||

| C6 | Metallic construction | 440 | General Manager | I13 | 49 min |

| Research and Development Manager | I14 | 41 min | |||

| C7 | Chemical | 370 | Health and Safety Manager | I15 | 59 min |

| Production Manager | I16 | 52 min | |||

| General Manager | I17 | 45 min | |||

| C8 | Electronic | 300 | Accounting Manager | I18 | 43 min |

| 270 | Sales Manager | I19 | 40 min | ||

| C9 | Mechanical | Quality Technician | I20 | 51 min | |

| Marketing Manager | I21 | 46 min | |||

| C10 | Finance | 210 | Information System Manager | I22 | 40 min |

| C11 | Paramedical | 120 | Financial Manager | I23 | 42 min |

| C12 | Textile | 90 | Supply chain Manager | I24 | 39 min |

4.2Data collection protocol

The interviews were digitally recorded, instantly transcribed in their entirety through the use of suitable software (Nvivo 12). Each of the speakers is identified by a different character color. This made it easier for us to recognize the people interviewed during the reading and proofreading required for the analysis in order to understand as accurately as possible the content of the exchanges with the people questioned.

The anonymity of those interviewed was guaranteed upstream of each interview. First, a thematic analysis allowed us to identify the strong ideas, highlighting them to facilitate our analysis. In a second step, we carried out a lexical analysis, by extracting the main keywords present in the various answers in order to count their frequency of citation. They are identified in bold in the verbatim whose content we present. Finally, we conducted a content analysis from the elements already collected by carrying out a double coding carried out with iterations between, on the one hand the collection of data and their analysis, and on the other hand between the analytical components themselves [38].

The analysis of the content is carried out on the processing of the words of the actors individually, and whose data are, then, condensed in order to identify archetypes (building theory process).

5Results

Tunisia is one of the countries most seriously affected by the COVID-19 crisis. Indeed, the forced shutdown of activities, following lockdowns, is resulting in an unrelenting wave of business failures. Despite government supportive measures, many of them private or public are disappearing or are in dire straits, but others are holding out with incredible resilience. They have had to reinvent their managerial practices and reconfigure themselves to be on the lookout for this new context of adversity. However, the organizational reconfiguration of the latter has manifested itself in different ways because it is correlated with the specificities of each company, whether sectoral, institutional or union. However, we managed to classify the different organizational configurations identified in our study into three main archetypes, namely: the humanist communitarian, the perfectionist mobilizer, and the incrementalist pragmatic. We will discuss the characteristics of these three archetypes in detail in the following sections.

5.1The humanist communitarian

The way of proceeding of humanist communitarian is “to humanize the organization and the organization will be saved by its stakeholders in the most difficult times.” The strategy of this archetype is based on a participatory approach, founded on the common best interest and based on mutual trust between all stakeholders. It is a strategy that aims to strengthen the commitment of the whole team, easy and intensive cross-functional participation and rapid decision-making.

“I1: We have immersed ourselves in the logic of ‘reciprocal care giving’. Our company will have to take care of their employees and the employees will have to take care of their company”.

It is a culture based on environmental and social values. It seeks to establish a continuum between, on the one hand, Tunisian communitarian values based on altruism, public interest and solidarity, on the other hand, on human values based on participation, relational proximity and the collaboration. The decisions thus taken in the midst of a health crisis are anchored to its cultures and consistent with its values. This reminds us of the study by [39] who believe that the behavior of individuals at work is based on the notion of “value” which refers to implicit and internalized beliefs.

“I2: New culture or new value? No. New implementation of values, that’s for sure. It is in times of crisis that they emerge: COVID-19 first invited us to identify what is revealed there”. “I3: By placing man, collaborator or client, leader or employee, at the center of the social- economy-environment triangle, with his humanity, his strength and his weaknesses, COVID-19 has acted as a revealer and catalyst - with an understanding perhaps more sensitive to our existing values"

This archetype features the mission-oriented or socially responsible company model that was driven by a sense of civic duty by making enormous contributions during the health emergency to the benefit of society.

Specific examples are: the free distribution of medical equipment and hygiene products (such as oxygen concentrators, screening devices, bibs, disinfectant gel, etc.); helping families in difficulty (by taking care of those infected with viruses and also spending on funerals for victims of corona); the contribution to the disinfection of public spaces; adapting the sales policy to meet new customer needs during containment (by implementing online sales and home delivery).

These actions provide feedback on the basic principles of corporate social responsibility (CSR). This made it possible to earn the support of all the stakeholders.

“I4: This has guaranteed us the support of all: our customers, civil society and our external partners have supported us by all means to get us out of this pandemic crisis”.

This result is consistent with the [40] study which showed the importance of CSR in enhancing the immunity of the company by making its stakeholders like true defenders who react collectively to ensure its survival in the context of COVID-19.

On a managerial level, this archetype tends to “humanize” the organization through a bet on the individual and collective intelligence potential of men. It is opposed to the classic bureaucratic model, even often autocratic, focused on productivity and the maximization of short-term profitability and considers employees as the real capital of the company and not mere means since they are the main (if not the only one) source of value creation.

One of the most important characteristics of the leadership model of this archetype relates to its humanism and the quality of its managerial ethics. It is based on the priority principle of serving line managers with regard to their employees so that they can perform their tasks under the best possible conditions. Its management methods are collegial and are characterized by: the systematic practice of listening and dialogue, the creation of a climate of trust, the practice of delegation and empowerment of people, encouragement to take initiative and creative ideas, facilitation, sharing and participation...

We believe that this type of leadership is very close to the servant leadership model that Greenleaf, a human resources practitioner, had intuition and vision for as early as the late 1970 s [41]. Greenleaf describes him as a “servant” to his organization and troops who shows humility and always tends to develop a spirit of participation within the team [41]. In short, “servant leadership places the manager at the service of his teams: employees take precedence over the mission.

“I5: During the first crisis meeting, I said, ‘I’m not sure what to do now. I have no response. Go ahead I listen to you: how do you see the solutions? In fact, no one has all the answers needed to lead in times of crisis. This is why it helps to approach leadership with humility. We must take advantage of the contributions of people and their collective intelligence”.

The organizational structure in times of COVID-19 crisis is lightened as much as possible to become almost flat. The latter has been debureaucratized by reducing the weight and power of the hierarchy. In this sense, the organization of work is implemented around agile concepts, like collaborative work, remote or teleworking and collective intelligence.

As a result, phygital culture, a logical crossbreeding of the physical and digital worlds, has imposed itself and has been adopted. This hybridization of work made it possible to have more flexibility where the autonomy of employees would be based on trust and accountability. Indeed, some employees can choose the working method that suits them, either remotely or face-to-face. Some companies have involved their employees in the definition and design of their own missions by implementing a new concept, that of ‘job crafting’. It consists of giving the employee the opportunity to shape their position so that it is in line with their own desires and passions. “I9: Only then will he put all his individual talent at the service of the collective”. “I10: The exercise of a professional activity should no longer be based exclusively on a pyramid hierarchy and on a job description with tasks to be performed, but on work experience that fits into a collective”.

Employees demonstrate strong resilience. They recognize that they are very motivated by their work environment, because they enjoy a great atmosphere and are particularly loyal to the company despite the wages and benefits that have come down in times of crisis! They also express their feeling of safety and security because their employers have made moral decisions in their favor, namely: safety at work, health care, extension of social protection, sick pay, sickness benefits, job retention programs, family helpers, work flexibility (the hybrid model, the flexible office...), etc.

“I6: Our company has shown a great sense of ethics on issues of worker well-being. It focused on concerns related to health, safety and well-being, medical care and work-life balance. We appreciated the efforts of our leaders who were willing to sacrifice profitability before people’s health and financial security. In return, we have ensured the survival of our company”.

5.2The perfectionist mobilizer

The way of proceeding of perfectionist mobilizer is “Maximize all available resources, whether material or human, by giving them the space they need". Its strategies are dominated by the optimal mobilization of distinctive organizational skills and also of other strategic resources. We could define perfectionist mobilizers by their rigor, their perfection and their concern to find the best positioning, the best organizational fit and the rational use of their professional resources.

Perfectionist mobilizers are always ready to rethink their organizational designs in order to improve their agility in the face of uncertainty and in the face of social and societal trends.

In times of the pandemic crisis, their action plans consisted of working at all strategic levels to ensure the resilience of its organizations and guarantee their sustainability.

Indeed, they relied on professional values of quality and customer satisfaction to reassure its customers. They used innovation to adapt to a COVID-19 context that demands it even more.

They improved relational values such as respect and especially proximity. They returned to strong moral values such as integrity and loyalty and also societal values relating to social responsibility, health and respect for the environment. They reconciled the company’s discourse (its corporate and marketing communication). They established the routine rules of hygiene and safety. They ensured the proximity of supply chains and production departments. They used the power of technology, digital, and e-commerce capabilities...In short, in times of pandemic, this reconciliation between the different types of resources was the key word in crisis management.

“I7: In times of the COVID-19 crisis, we have ensured synergy on the one hand of societal ethics and managerial practices favoring the health, safety and well-being of employees, and on the other hand of economic performance focused on the reinvention of technical and technological capacities ”.

“I11: We used the right expertise in the right places to do the right manners with the best resources”.

The culture of this archetype is characterized by its capacity for transformation, agility and adaptation to change. The health crisis was an opportunity for this archetype to revisit the values that form the basis of their cultures in order to support the engagement of internal (especially staff) and external (customers, suppliers) interested parties. This coincides with the study by [42] who believes that the corporate culture is part of the ways of reacting to common situations in the life of the company.

“I13: It is obvious that large-scale earthquakes in the environment, such as those caused by COVID-19, force us to readjust our culture to adapt to the new realities of the environment”. “I14: Lots of values have shifted: from team spirit, integrity, respect, responsibility, quality and customer satisfaction to safety and health, solidarity, ‘empathy, fairness, justice, trust, autonomy, agility, collaboration, partnership, and resilience”.

The structure used by this archetype in times of Covid is the network structure. It is a structure that organizes the company’s ecosystem: its internal network and its network of partners. This network is made up of autonomous poles (operational units or supports) and of connections between these poles (collaboration between units). Its ability to innovate, its flexible coordination, its search for overall cohesion, make it a structure adapted to a turbulent environment. Its implementation is facilitated by digital technologies. New practices have therefore emerged in an ATAWADAC logic (Any Time, Anywhere, Any Device, Any Content). “I16: The pandemic has obviously changed our structure and our working methods. We have moved from a matrix structure to a network structure. This has forced us to focus more and more on technology, which manifests itself in: the digitization of rapid exchanges, teleworking and tele-meetings, use of online collaboration platforms, generalization of e- learning, private networks virtual, cloud computing, etc”.

In terms of management strategies, a more pronounced orientation towards the implementation of management by objectives and remote management has become essential in these circumstances, which has led to greater decision-making autonomy at work.

“I15: Some people talk about autonomy or trust. I’m talking about ‘liberation’, in the sense of a ‘liberated’ individual: freed from public transport, freed from rigid schedules, freed from the ‘flow state’ which hinders their concentration due to constant phone calls or emails, freed from certain normative shackles (eg clothing). A new acronym has thus appeared in this health crisis: ICR ‘Individual Corporate Responsibility’. This means that everyone can choose his own contribution to the company”.

The complexity of this archetype and the change in the environment on technological, economic, environmental, and social levels with ever more uncertainty have led to the emergence of a leadership capable of adapting to adversity and to all sometimes antagonistic situations. The latter has shown this evidence to manage the contexts of space (face-to-face / distance) and time (synchronous / asynchronous), adopt sometimes opposing coordination methods (autonomy / control), mobilize resources (human / material), etc.

It is the leadership that has the capacity to work on several fronts at the same time. We believe this is a typical multimodal leadership model, a concept of leadership advocated by [43].

“I23: The pandemic presents all the characteristics of a generalized crisis known as“ landscape scale ”: that is to say a chain of unexpected and unknown events which generates a new context, itself leading to the redefinition of our organizational postures and managerial practices. Coworking, mixed management, a new more decentralized and cross-functional structure, new coordination... This has led us to adapt to all situations and work on several fronts “.

As for the employees, they have shown strong resilience by demonstrating actions of commitment, involvement and resistance in the face of disruptive events. The reason for these reactions stems from a great confidence in the organization and in the decisions taken by it to circumvent the crisis and absorb its negative repercussions which could harm the interests of the employees.

“I8: the last two years have ended with an unprecedented level of uncertainty: the pandemic not yet under control, new Covid strain in Great Britain, successive confinements.... At the beginning, this caused us fear about our health and uncertainty responsible for our jobs and our finances. But our company helps us transcend those feelings”.

“I12 . . . It has supported us in overcoming the temptation to withdraw, to fear, to go beyond habits of prudence to, on the contrary, invest, innovate and find new balances more respectful of the environment and the well-being of employees”.

5.3The incrementalist pragmatic

The way of proceeding of incrementalist pragmatic is “the priority is to ensure the survival of our organization in times of change but with too little modification in our basic policies."

Its strategy is to survive at all costs in times of crisis by reacting with pragmatic actions. In times of crisis, and in the face of complex problems, the incrementalist pragmatic does not tend to systematically reconsider the main lines of his policies, the reasoning and the values which represent his fundamental pillars.

Thus, the decisions taken do not correspond to a radical change or a substantial reform but rather provoke small marginal or incremental adjustments, which just meet a requirement of responsiveness and sustainability in a context of adversity.

Decisions in times of pandemic crisis have often been centralized by a single hierarchical structure, called in most of the studied cases ‘crisis unit’, thus forming a solar structure. The crisis unit took over the management of all of the company’s units. Its main task is to prepare the business continuity plan, take the measures, and take the necessary actions to maintain control of the crisis and guarantee the continuity of the organization. It is made up of members of staff designated and deemed to be the most competent by the general management. In some companies, it is also made up of outside experts in a wide range of fields, including technology, artificial intelligence, occupational health, workforce planning and skills identification, recruitment and risk management...

“I17: In the case of COVID-19, we had to think about the health, economic, and social consequences of the crisis. To manage a complex system, we can apply two methods. Either we make radical choices imposed by an emergency situation - as in the event of war or disaster - by centralizing power and forcing everyone to obey, or we apply incremental decisions, which allow learning, correct the shot and adapt. Our company has opted for a combination of these two approaches”.

The decisions taken are certainly formalized but they are pragmatic and are characterized by their immediate and reactive nature. The decisions were not always social but considered by some managers to be necessary to ensure the sustainability and continuity of their companies. In this sense, apart from the remote work of employees who remained functional during the health crisis, some employers were faced with the heartbreaking decision to reassign some employees, or to give them unpaid or partially paid leave or postpone job vacancies to save costs.

In extreme cases, they have decided to postpone the payment of wages and other forms of remuneration, or even to lay off workers.

“I18: Since mid-March 2020, we have been experiencing a big bang linked to the health crisis. It is a war without t bombs that threatens our existence. In this circumstance survival is a priority in the sense that the reason for being and to continue to be. So instead of immersing yourself in a utopian humanism you have to be pragmatic and determined”.

“I19: Better to fire a few people than to disappear and all people lose their jobs and the entire country a productive business on the other. The important thing is that we were able to survive by reactivity as brutal and spontaneous as the change itself; this is the very definition of improvisation”.

The actions that have been put in place are based on two approaches: one is basic (e.g. government aid, conduct of rigorous financial stress tests through an austerity policy, staggering of loans, rotation of resources between different positions, short-term contracts, cross training, etc.); the other is more innovative (e.g. hybridizing remote and face-to-face work, digitization, use of social networks and online sales to better contact the customer, etc.).

“I21: The classical solutions linked above all to the financial balance and the stability of our supply chain were necessary to maintain efficiency. But that does not prevent us from adopting innovative solutions adapted to the context of a pandemic crisis. At this level, we have opted for online collaboration tools, we have taken up e-commerce, we have invested in digital channels to keep in touch with our customers”.

However, even with the innovative solutions carried out by this archetype, its actions always remain predominant by considerations of effectiveness and efficiency, by the design of structures and forms of work organization that will allow it to create the optimal fit with his culture. This seems consistent with the observations of [44] that organizational responses to crises by models of professional bureaucracy are always focused on professionalism, expertise and specialization.

“I22: Innovation does not mean breaking with our culture. Moreover, in Japanese culture the notion of change is defined through the couple “tradition / innovation. This means that in order to end this health crisis, we must ask ourselves what we want to keep at all costs and what needs to be innovated”.

The leadership that characterizes this archetype is indeed faithful to the culture of its organization. It introduces organization into the way things are done by respecting the structure as it is and applying the procedures and systems in force, while developing the skills / competencies required by the hierarchical top. This leadership is not very emotional but determined and more focused on efficiency and achieving goals. Even in times of adversity, it seeks to maximize employee productivity by making the most of company resources. This coincides with Drucker’s (2006) executive leadership model. It still remains imbued with “neo-Taylorist” beliefs in the exercise of power and the management of men. It can be an organizer, authentic or autocrat-paternalistic [45].

“I24: In the midst of a health crisis, I identified myself with a sports coach who coordinates and directs the actions of individual players so that they fit into the overall game plan, by giving instructions and then monitoring the actions of each player to make sure he’s in the right place or doing the right thing”.

Employees have shown low resilience in complaining about their organizations’ policies in times of crisis. They say their employers have done everything to save their business, but they have done nothing to alleviate the psychosocial risks they are facing in the midst of the pandemic period. They thus relied on an individual defense mechanism such as cognitive normalization. It’s about stimulating yourself into an intense defense activity designed to allay anxieties and make the disruptive event emotionally manageable. It reminds us of the concept of ‘Enacted Sensemaking’ advocated by [26] which consists in seeking meaning by the collective work following a traumatic phase.

“I20: We are put at a distance. Our professional, family, social and emotional life is profoundly modified. Some continue to work 100% in a company full or part time, while others do it remotely. Still others can no longer work at all. Work schedules, relationships with the hierarchy and the spatio-temporal boundaries of the company are disrupted. Our employers were preoccupied with saving their business at the expense of their employees as if we were not one of them. We were forced to accept the situation and adapt to it by finding individual solutions to get out of it”.

The following table reveals our empirical model by synthesizing the main characteristics of three archetypes identified in our empirical study.

6Conclusion

The COVID-19 health pandemic is an unprecedented generalized crisis that has simultaneously caused an economic and social crisis of unprecedented magnitude and is revealing its own vulnerabilities to the world. As a result, some of the companies have had to reconfigure themselves by forming archetypes intended to manage and cope with the crisis.

In this sense, our research objective consists of identifying a taxonomy of the main archetypes of management of the COVID-19 health crisis. To do this, we studied twelve Tunisian companies that were able to successfully cross the three waves of the health crisis in question and have managed to resist and ensure their sustainability, at least until now. We only believe the components of our study, namely: the subject (the organizational configuration), the circumstance (COVID-19), and the context (Tunisia) together constitute the originality of our research. Indeed, to our knowledge, no study has been carried out so far on the typical configurations for managing the COVID-19 crisis in a Tunisian context.

We identified three archetypes on the basis of five organizational factors that we inspired from the onion model of [2] and qualified it as configuration “determinants”, namely: strategy, structure, culture, leadership, and people.

These archetypes are: the humanist communitarian, the perfectionist mobilizer, and the incrementalist pragmatic. A summary of the characteristics of these three main archetypes is presented in Table 4 (page 34).

This variety of archetypes is consistent with the proposition advanced by [46, p.30] who assert that ⪡... Of course, multiple forms are produced from taxonomies and organizational typologies. Variety is also found when looking for the existence of archetypes empirically ⪢.

Table 4

Empirical model: summary of the main characteristics of three archetypes of crisis management according to five determinants of organizational configuration

| Determinants / Archetypes | The humanist communitarian | The perfectionist mobilizer | The incrementalist pragmatic |

| Strategy | Participatory approach with all stakeholders | Optimal mobilization of organizational skills and other strategic resources | Survival of the organization based on pragmatic actions |

| Culture | Stable based on the humanization of the organization (environmental and social values) | Transformative based on agility and adaptation to change | Slightly adaptive with the change of the environment and based on effectiveness and efficiency |

| Structure | Plate: participation, empowerment and flexibility (hybrid work, job crafting) | Networked: innovation, flexibility of coordination, autonomy, digitization | Solar: formalized and centralized decisions |

| Leadership | Servant: humility and spirit of participation | Multimodal: ability to work on several fronts and adapt to all situations | Executive: autocracy and respect for procedures and systems in force |

| Individuals | Strong resilience: recognition and feeling of safety and security | Strong resilience: standardization and confidence in the company | Low resilience: frustration and cognitive normalization |

We wish to highlight the contributions that this research brings in the field of configurations and crisis management.

As a result, we believe that our research stands out from many of the works documented in the literature on two levels: the magnitude of the crisis and the methodology.

First, in the field of crisis management, a predominant place is given, either to internal crises caused by organizations, or to local or even national crises suffered by organizations [2, 9, 47]. For example, [21] studied crisis-provoking companies and differentiated among the ten archetypes of his study, six archetypes of success (including the dominant firm, the entrepreneurial conglomerate, the innovator) and four archetypes of failure (including the stagnant bureaucracy, the headless giant, the revival). In addition, in his doctoral thesis, [8] studied nine public organizations with a social and civic intervention role and which were located in the ‘Montérégie’ region of Canada during the ice storm of 1998.

However, this research focused on organizations that have suffered a generalized global crisis of unprecedented magnitude, such as the pandemic COVID-19 crisis, which has influenced the internal operating methods of the latter, pushing them to configure their structures and their strategies to survive in a context of adversity. We therefore believe that our research has enriched the configurational perspective by defining archetypes capable of managing a major crisis such as the COVID-19 crisis.

The archetypes thus identified in our study may constitute typical models to be followed by companies wishing to resist the health crisis that is not yet over and whose repercussions can last for a long time.

Secondly, our research is an extension of this initial work on the configirational approach, but it also stands out above all on the methodological level. Indeed, we have defined archetypes not on the basis of statistical correlations between various variables like the majority of previous studies on configurations in times of crisis [7, 19, 20], but by relying on the interpretation and the reflexivity of the actors on their own experience on the basis of a qualitative methodology.

Our research results allow us to identify two managerial implications that could arouse the interest of practitioners, researchers, and companies. These implications are linked at two levels: the crisis management plan and the organizational response of bureaucratic organizations.

First, our results stand out from the “prescriptive” and normative foundations of the theories on crisis management planning [2, 24]. Indeed, among the twelve cases we studied, none limited to the application of a formal plan, previously designed and developed. It is therefore necessary to study the fundamental pillars of a contingent crisis plan that makes it possible to adapt to unforeseen, uncertain and disruptive circumstances.

Second, few studies claim that bureaucratic organizations tend to abandon their routines to develop new organizational responses [25, 30]. In this research, we found that some bureaucratic organizations (belonging to the incrementalist pragmatic archetype) were able to innovate some of its policies (for example towards digitization, teleworking, e-commerce) by modifying (even slightly) the normal course of their organizational routines.

It is therefore recommended to study the best practices for debureaucratizing bureaucratic organizations in times of crisis.

Note at the end that the results presented in our research should not, however, be considered beyond their context (COVID-19 crisis) and their theme (organizational configuration). Indeed, some later work such as that carried out by [18] noted the limits of the archetype manifested by ‘quantum leaps’. It thus happens that a configuration is no longer synchronous with its environment. This might make our study too contextual and therefore might not be generalized to other types of crises.

In addition, our research allows us to establish how organizations configure themselves, but it does not allow us to establish what they have learned and how this learning can allow them to increase their robustness in the face of future crises. This could make the archetypes identified in our study too abstract and from which organizations cannot learn.

Therefore, we recommend that future research could focus on the best organizational practices to transcend the quantum leaps of an archetype to make it flexible and adaptable to all types of crises. Moreover, the necessary conditions that must be present so that the learning acquired during crises can be profitable in the long term.

Acknowledgments

The author has no acknowledgments.

References

[1] | Berg BL Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. 3rd Edition. Allyn and Bacon; (1998) . |

[2] | Pauchant TC , Mitroff II La gestion des crises et des paradoxes - Prévenir les effets destructeurs de nosorganisations Éditions Québec/Amérique - Presse HEC 2001. |

[3] | Mokline B , Ben Abdallah MA , Organizational resilience as response to a crisis: case of COVID-19 crisis, Continuity & Resilience Review (2021) ;3: (3):232–47. DOI: 10.1108/CRR-03-2021-0008. |

[4] | Bryce C , Ring P , Ashby S , Wardman JK , Resilience in the face of uncertainty: early lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, Journal of Risk Research (2020) ;23: (7):880–7. DOI: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1756379. |

[5] | Meyer A , Tsui A , Hinings CR , Configurational Approaches to Organizational Analysis, Academy of Management Journal (1993) ;36: (6):1175–95. DOI: 10.2307/256809. |

[6] | Mintzberg H , Ahlstrand B , Lampel J , Safari en pays stratégie: L’exploration des grands courants de la penséestratégique. Paris: Éditions Village Mondial; 1999. |

[7] | Abdel-Latif A , Saad-Eldien A , Marzouk M , Applying system archetypesin real estate development crises, Systems Research and BehavioralScience (2020) ;38: (6):911–22. DOI: 10.1002/sres.2721. |

[8] | Lalonde C Configurations organisationnelles et gestion de crise, Doctoral thesis, Graduate School of Business Studies, University of Montreal. 2003. |

[9] | Lang B , Dolan R , Kemper J , Northey G . Prosumers in times of crisis: definition, archetypes and implications, Journal of Service Management (2021) ;32: (2):176–89. DOI: 10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0155. |

[10] | Weick KE , The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Glush Disaster, Administrative Science Quaterly (1993) ;38: (4):628–52. DOI: 10.2307/2393339. |

[11] | Livian YF E . Introduction á l’Analyse des Organisations. Paris: Economica; 2000. |

[12] | Dufès E , Ratinaud C , Modélisation des crises: une démarche en trois dimensions, Préventique (2013) ;132: (201):27–9. |

[13] | Webb GR , Chevreau FR , Planning to improvise: The Importance of creativity and flexibility in crisis response, International Journal of Emergency Management (2006) ;3: (1):66–72. DOI: 10.1504/IJEM.2006.010282. |

[14] | Denis H La réponse aux catastrophes. Quand l’impossible survient, Presses Internationales Polytechnique; 2002. |

[15] | Crozier M , Freidberg E L’acteur et le système. Paris: Seuil; 1977. |

[16] | Miller D , Configurations of Strategy and Structure: Towards a Synthesis, Strategic Management Journal (1986) ;7: (3):233–49. DOI: 10.1002/smj.4250070305. |

[17] | Doty H , Glick WH , Huber CP , Fit, Equifinality and Organizational Effectiveness: A Test of Two Configurational Theories, Academy of Management Journal (1993) ;36: (6):1196–250. DOI: 10.5465/256810. |

[18] | Miller D , Friesen PH , Structural Change and Performance: Quantum versus Piecemeal- Incremental Approaches, Academy of Management Journal (2017) ;25: (4):867–92. DOI: 10.5465/256104. |

[19] | Miller D , The Genesis of Configuration, Academy of Management Review (1987) ;12: (4):686–701. DOI: 10.2307/258073. |

[20] | Rich P , The organizational taxonomy: Definition and design, Academy of Management Review (1992) ;17: (4):758–81. DOI: 10.5465/amr.1992.4279068. |

[21] | Miller D , Friesen PH . Strategy-Making in Context: Ten Empirical Archetypes, Journal of Management Studies (1977) ;14: (3):253–79. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.1977.tb00365.x. |

[22] | Morin E Sociologie. Paris: Seuil; 1994. |

[23] | Nonaka I , A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation, Organization Science (1994) ;5: (1):14–37. DOI: 10.1287/orsc.5.1.14. |

[24] | Bundy J , Pfarrer MD , Short CE , Coombs TW , Crises and crisis management: Integration, interpretation and research development, Journal of Management (2016) ;43: (6):1661–92. DOI: 10.1177/0149206316680030. |

[25] | Cefis E , Bartoloni E , Bonati M , Show me how to live: Firms’ financial conditions and innovation during the crisis, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics (2020) ;52: (C):63–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.strueco.2019.10.001. |

[26] | Weick KE , Enacted Sensemaking in Crisis Situations, Journal of Management Studies (1988) ;25: (4):305–17. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.1988.tb00039.x. |

[27] | Britton NR , Constraint or Effectiveness in Disaster Management, The Bureaucratic Imperative versus Organizational Mission. Canberra Bulletin of Public Administration (1991) ;64: (1):54–64. |

[28] | Branicki L , Steyer V , Sullivan-Taylor B , Why resilience managers aren’t resilient, and what human resource management can do about it, The International Journal of Human Resource Management (2019) ;30: (8):1261–86. DOI: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1244104. |

[29] | RosenthaL U , Charles MT , Hart PT Coping with Crises. The Management of Disasters, Riots and Terrorism, Charles C. Thomas Publisher; (1989) . |

[30] | Brouillette JR , Quarantelli EL , Types of Patterned Variation in Bureaucratie Adaptations to Organizational Stress, Sociological Inquiry, Winter (1971) ;41: (1):39–46. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.1971.tb01198.x. |

[31] | Altintas G , Royer I , Reinforcing resilience through post-crisis learning: a longitudinal study of two periods of turbulence, M@n@gement (2009) ;12: (4):266–93. DOI: 10.3917/mana.124.0266. |

[32] | Crozier M , Friedberg H L’Acteur et le système : les contraintes de l’action collective. Paris: Points Essais; 2014. |

[33] | Deslauriers JP , Recherche qualitative : guide pratique. Montréal: McGraw-Hill; 1991. |

[34] | Baumard P , Donada C , Ibert J , Xuerb JM , Data collection and the management of their sources. In Thiétart, R.A. (ed.) Management research methods. Paris: Dunod; 2003. pp. 224-256. |

[35] | Demers C The interview, in Y. Giordano (coord.), Lead a research project: a qualitative perspective. Caen, Management and Company Editions (EMS). 2003;173-210. |

[36] | Miles MB , Huberman AM , Analysis of qualitative data: A collection of new methods. Brussels: De Boeck. Translation of Analysing qualitative data: A source book for new methods, 1979, 1984. Beverly Hills: Wise; 1991. |

[37] | Yin RK Case study research: design and methods. 3rd ed. London: Sage; 2003. |

[38] | Mukamurera J , Lacourse F , Couturier Y , Des avancées en analyse qualitative: pour une transparence et unesystématisation des pratiques, Recherche Qualitative (2006) ;26: (1):110–38. |

[39] | O’Reilly CA , Chatman J , Caldwell DF , People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit, Academy of Management Journal (1991) ;34: (3):487–516. DOI: 10.2307/256404. |

[40] | Manuel T , Herron TL , An ethical perspective of business CSR and the COVID-19 pandemic, Society and Business Review (2020) ;15: (3):235–53. DOI: 10.1108/SBR-06-2020-0086. |

[41] | Frick DM Robert Greenleaf: A Life of Servant Leadership. San Francisco: Berrett Koehler; 2004. |

[42] | Thévenet M La culture d’entreprise, PUF collection Quesais-je? 7émeédition. Paris; 2015. |

[43] | Hooijberg R , Watkins M , The Future of Team Leadership Is Multimodal, MIT Sloan Management Review (2021) ;62: (3):1–4. |

[44] | Sylves RT , Pavlak TJ The Big Apple and Disaster Planning : HowNewYork City Manages Major Emergencies. in Sylves RT,Waugh WL (eds.), Cities and Disaster. North American Studies in Emergency Management, Charles C. Springfield, Illinois: Thomas Publisher; (1990) . pp. 185–219. |

[45] | Drucker PF The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things. New York: Harper Collins Publishers; (2006) . |

[46] | Greenwood R , Hinings CR Understanding Strategic Change: The Contribution of Archetypes, Academy of ManagementJournal (1993) ;35: (5):1052–81. DOI: 10.2307/256645. |

[47] | Lalonde C , In Search of Archetypes in Crisis Management, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management (2004) ;12: (2):76–88. DOI: 10.1111/j.0966-0879.2004.00437.x. |

![The onion model in crisis management ([39], p. 76).](https://content.iospress.com:443/media/hsm/2023/42-1/hsm-42-1-hsm211581/hsm-42-hsm211581-g001.jpg)