Partnerships in Employment: Building strong coalitions to facilitate systems change for youth and young adults

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In response to continuing disparity in the employment outcomes of young adults, the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities established an initiative to support state consortia to implement systems change with an explicit focus on policies, infrastructure, and collaboration across state agencies and other stakeholders. Eight states received 5 year grants under the Partnerships in Employment project.

OBJECTIVE:

This manuscript provides an overview of the initiative, and key lessons learned including the importance of a backbone organization, the need for a long term approach to change and capacity building, the role of data as a communication mechanism, integration across initiatives, linking local implementation and state policy, and intentional investment in communication.

CONCLUSION:

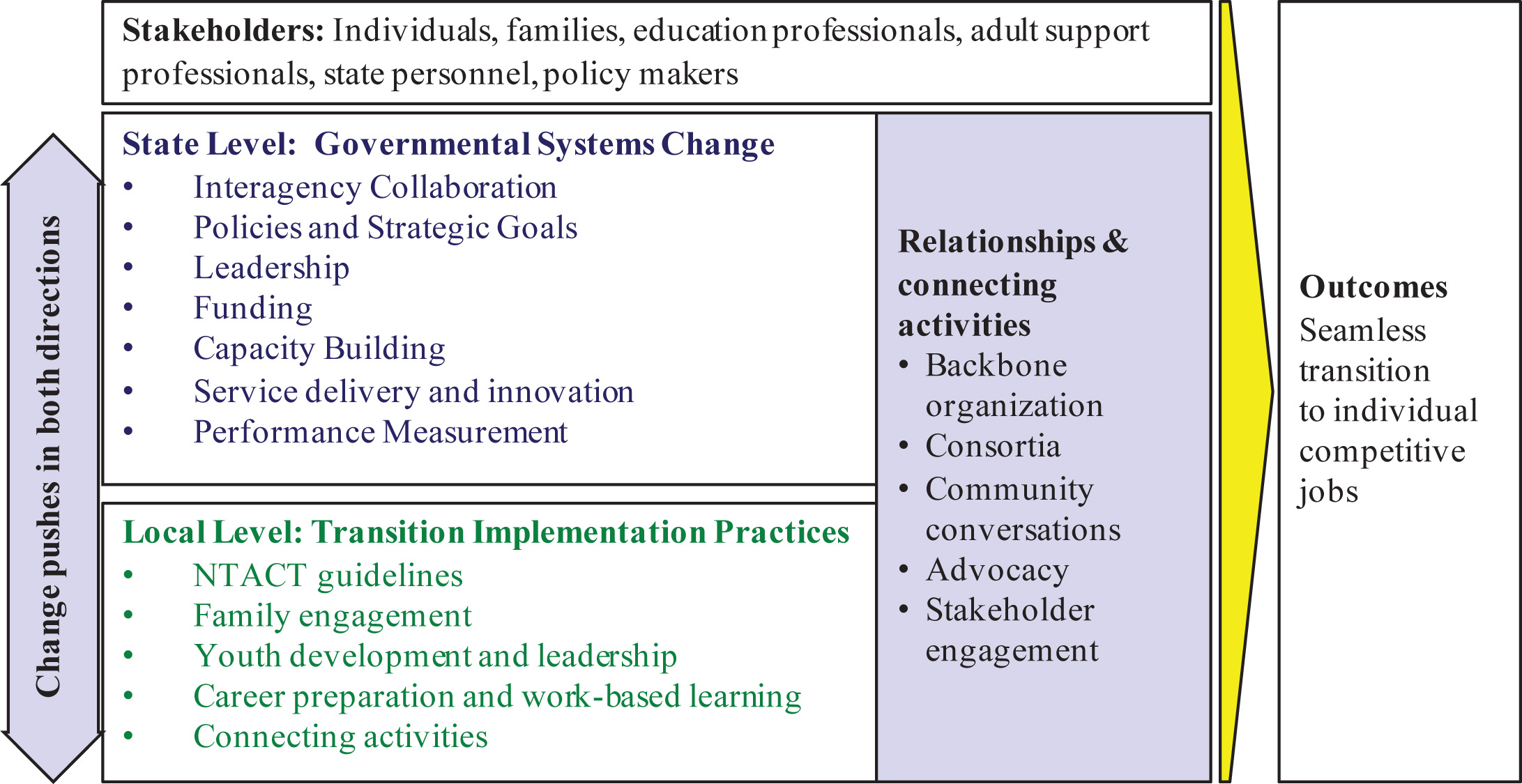

A holistic model for addressing systems change is offered that reflects the importance of intentional investment in relationships and connecting activities that link stakeholders across state governmental systems change, local implementation, and advocacy.

1Introduction

Employment is a primary pathway to independence and autonomy, yet research shows continuing disparity between the employment outcomes of youth with and without disabilities. American Community Survey data show that in 2014 the employment rate for young adults without a disability aged 16–21 was 41%, compared to 20% percent for youth with a cognitive disability. For young adults between the ages of 22 and 30 the employment gap widens, with 76% of youth without a disability employed, compared to 41% of youth with a cognitive disability. Young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) have even lower employment participation. Data from the National Core Indicators Project suggest that in 2014 only 4% of youth supported by state IDD agencies aged 18–21 were employed in individual integrated jobs, and only 9% of those aged 22–30, and despite a growing policy focus on improving outcomes these percentages declined between 2010 and 2014. Youth supported by IDD agencies also experience low wages and hours, averaging 12 hours and $92/week for 22–30 year olds (Butterworth & Migliore, 2015). Employment outcomes for young adults with IDD are far below those of peers with and without disabilities.

Poor employment outcomes have persisted despite the desire to work in the community. Individuals with IDD have clearly expressed both a desire to be full participants in the typical labor force and an expectation that they would be employed after graduation (Barrows et al., 2015; Migliore, Mank, Grossi, & Rogan, 2007; Timmons, Hall, Bose, Wolfe, & Winsor, 2011, Nonnemacher & Bambara, 2011; Walker, 2011), and 86% of transition age young adults with an intellectual disability state that they expect to be employed after graduation (NLTS2, n.d.). However, Timmons et al. (2011) found that individuals with IDD are often routed away from community employment during the transition from school to adulthood.

Grigal, Hart and Migliore (2011) found that students with IDD were less likely to have competitive employment goals and outcomes and more likely to have sheltered employment goals and outcomes compared to students with other disabilities. NLTS2 data on high school students’ transition plans show that 20% of students with intellectual disabilities had primary goals related to sheltered employment, despite the national focus on integrated employment (Shogren and Plotner, 2012). Poor employment outcomes for youth with IDD are a result of a confluence of issues including: inadequate collaboration between the adult disability and education systems (Certo et al., 2008, Plotner & Marshall, 2015); limited emphasis on integrated employment as a priority outcome across state systems (Butterworth, Smith, Winsor, Ciulla Timmons, Migliore, & Domin, 2016); insufficient family engagement in transition and employment planning (Altumairi, 2016); limited vocational experiences while in school (Wehman, 2006; Carter, Austin, & Trainor, 2011) and an education and adult workforce that does not consistently implement evidence based or best practice despite clearly defined evidence based practices that support post-secondary outcomes (Mazzotti & Plotner, 2016; Migliore et al., 2012).

1.1Lack of collaboration between key players

Interagency collaboration is well established as a predictor of employment outcomes during transition (Haber et al., 2016). Despite mandates for collaboration in legislation such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004) and the Workforce Innovation and Opportunities Act (2014), insufficient linkages between the education, rehabilitation, and adult IDD systems are a primary factor in the employment outcomes of youth with IDD (Certo et al., 2008; Martinez et al., 2010; NCD, 2008, Plotner & Marshall, 2015, Haber et al., 2016). Research reveals a need for defined collaboration models and roles between education and rehabilitation professionals (Stevenson & Fowler, 2016; Oertle & Seader, 2015). Hart, Zimbrich, and Whelley (2002) identify five major barriers to increased coordination: Partnerships are seldom effective both at the state and local levels; mechanisms for information-sharing and shared service delivery are uncoordinated; there is a lack of resource mapping at the state and local level; gaps in service delivery exist; and there is a lack of student and family-professional partnerships.

1.2Inadequate emphasis on community employment

Adult systems continue to make limited investments in employment outcomes. The number of overall VR agency closures into employment for individuals with ID declined slightly but steadily over the past decade (Butterworth et al., 2016). In FY2014 state IDD agencies reported that 19.1% of adults who participated in a day service received integrated employment supports, and only 11% of funds for day and employment services were directed to integrated employment (Butterworth et al., 2016). Data for 2014-2015 from the National Core Indicators Project suggest that only 14.8% of working age adults work in integrated employment (Human Services Research Institute & Institute for Community Inclusion, 2016). At the same time, participation in non-work services has grown steadily, suggesting that employment continues to be viewed as an add-on service rather than a systemic change (Mank, Cioffi, & Yavanoff, 2003; Butterworth, et al., 2015).

1.3Family factors

Family engagement is a key component in successful transition planning, with a focus on building relationships and information sharing between families and professionals. However, parents report that they do not receive adequate information to support their children in the transition process, that programs are a poor fit for student needs, and that they have insufficient information about the interaction of work and benefits (Hetherington et al., 2010; Almutairi, 2016; Winsor, Butterworth, Lugas, & Hall, 2010; Hall & Kramer, 2009; Luecking & Wittenburg, 2009). Carter et al. (2011) found that the family factor most predictive of paid work experiences in school was parental expectations, but families frequently experience low expectations and support from school programs (Blustein, et al., 2016; Henninger & Taylor, 2014; Almutairi, 2016).

1.4Education system factors

Confirming findings from previous research, Carter et al. (2011) found that many students with severe disabilities lack early vocational experiences. Other education system factors include: teacher expectations of students working (Carter et al., 2010), limited professional development related to transition practices (Mazzotti & Plotner, 2016; Winsor et al., 2010), lack of long term follow-up of graduates following transition to employment (Rusch & Braddock, 2004; Callahan et al., 2014) and limited diffusion of evidence based transition practices in schools (Mazzotti & Plotner, 2016).

1.5History of the Partnerships in Employment project

The Administration on Developmental Disabilities, now the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AIDD) in the Administration on Community Living, issued an announcement in 2011 soliciting proposals from state consortia to support systems change with an explicit focus on policies, infrastructure, and collaboration across state agencies and other stakeholders. Responding to concerns about inadequate collaboration and systems commitment to competitive integrated employment, the request for proposals stated that, “The purpose of this effort is to enhance collaboration across existing State systems, including programs administered by State Developmental Disabilities agencies, State Vocational Rehabilitation agencies, State Educational agencies and other entities to increase competitive employment outcomes for youth and young adults with DD, including ID.” Specific objectives were,

1) the development of policies that support competitive employment in integrated settings as the first and desired outcome for youth and young adults with DD including ID; 2) the removal of systemic barriers to competitive employment in integrated settings; 3) the implementation of strategies and best practices that improve employment outcomes for youth and young adults with DD including ID; and 4) enhanced statewide collaborations that can facilitate the transition process from secondary and post-secondary school, or other pre-vocational training settings, to competitive employment in integrated settings. (HHS-2-11-ACF-ADD-DN-02016)

The project was unique because of its focus on policy change, resolving systemic barriers, and enhancing collaboration. States were required to form a consortium that included at minimum (but not limited to) the state Developmental Disabilities Council, Vocational Rehabilitation agency, Developmental Disabilities agency, and Education agency, and to implement a memorandum of understanding prior to application. Six states were funded in 2011, and two were funded in 2012 (see Table 1). In all states either the AIDD funded Developmental Disabilities Council or University Center for Excellence served as the grantee and manager for the initiative.

Table 1

Partnerships in employment state projects

| State | Lead partner | Start date | 2011 State population |

| Alaska | Governor’s Council on Disabilities and Special Education | 2012 | 722,718 |

| California | Tarjan Center at UCLA | 2011 | 37,619,912 |

| Iowa | Iowa Developmental Disabilities Council | 2011 | 3,062,309 |

| Mississippi | Mississippi Council on Developmental Disabilities | 2011 | 2,978,512 |

| Missouri | Institute for Human Development, University of Missouri Kansas City | 2011 | 6,010,688 |

| New York | Strong Center for Developmental Disabilities, University of Rochester | 2011 | 19,465,197 |

| Tennessee | Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities | 2012 | 6,403,353 |

| Wisconsin | The Wisconsin Board for People with Developmental Disabilities | 2011 | 5,711,767 |

1.5.1Defining systems change

State systems change, as communicated by AIDD as the projects began, refers to sustainable changes in policy or infrastructure that support employment as the priority outcome for youth and young adults and continue beyond project funding. Policy includes high level statements of intent such as legislation, regulations, executive orders, and state agency policy but also operational policy such as the way services are defined in state HCBS waivers, provider qualification standards, funding structure and rates, or inclusion of employment in the annual service plan. Infrastructure includes interagency managing committees, sustained support for training and technical assistance resources, or employment data systems.

1.5.2Conceptual framework

There is growing emphasis on the need for a comprehensive policy-driven approach at the state and federal levels to drive the transition process (Antosh et al., 2013). The large variation in employment participation across state IDD agencies suggests that examining state agency policy and practice is vital for understanding employment outcomes. Research with state IDD agencies identified 7 elements of state agency policy and practice as drivers of employment outcomes: leadership, interagency collaboration, strategic goals and operating policies, financing and contracting, performance measurement, training and technical assistance, and service innovation (Hall et al., 2007; State Employment Leadership Network, 2016). Known as the Higher Performing States Framework, states with stronger employment outcomes for individuals with IDD communicate employment as a priority in each of these elements. Data from Washington’s Jobs by 21 Partnership Project (Winsor, Butterworth, & Boone, 2011) demonstrated that specific elements of higher performing states including clear and concrete goals, outcome data collection, collaboration at the state and local levels, finding policy, and capacity building provide a foundation upon which transition models can be developed on a statewide level.

1.5.3Partnerships in Employment national systems change initiative

AIDD conceived the systems change initiative with several components: state projects, external evaluation and technical assistance (TA). As with the state projects, RFP’s were issued for an evaluation contractor and TA provider. The Lewin Group was awarded the evaluation contract and the Training and Technical Assistance Center (PIE TA Center), was awarded to the Institute for Community Inclusion, University of Massachusetts Boston in partnership with the National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities’ Services (NASDDDS). The PIE TA Center provided training and technical assistance based upon an adaption of the Higher Performing States Model. This adapted model focused on the transition and young adult population and incorporated elements from Certo et al. (2003) that highlight collaboration between Education, VR, and IDD systems and evidence based practices identified by the National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center (Test et al., 2013). PIE TA Center support emphasized regular collaboration and communication between and with states and included:

A comprehensive initial state assessment including document review, key informant interviews, onsite meetings with stakeholders and project consortia, and a stakeholder survey. A report of findings and recommendations was organized by the high performing states model.

• Monthly network meetings supported community collaboration and addressed emerging topics on transition, post-secondary education and competitive employment.

• Topical communities of practice were defined by participating states, and supported through in-depth discussion and problem solving on topics that ranged from family awareness about transition to transportation.

• PIE TA Center staff met by phone or webinar every 4 to 6 weeks with leadership from each state project and addressed work plan goals and emerging questions and issues. TA Center staff provided support onsite annually with project staff and Consortium members.

• An annual meeting supported topical discussion between states, AIDD, and the evaluation project; supported sharing of experiences, and featured conversations with AIDD, RSA, ODEP and OSERS leadership.

• Topical webinars provided targeted training on identified priority topics.

• The PIE TA Center website provided a resource library of project and related materials including publications on topics requested by state projects, briefs written with state project staff, and documents that reported on project findings.

1.6Evolution of project expectations

A significant challenge during the first year of the project was clarifying AIDD’s goals. For the first 6 states, substantial commitments were made in the proposed work plans to focus on local demonstration and pilot initiatives aimed at increasing employment outcomes for youth and young adults with IDD. However, AIDD clarified in year one that the anticipated outcomes were changes in policy and infrastructure at the systems level that would support high quality employment outcomes, rather than increasing individual job outcomes. While the pilot initiatives continued in states, state projects were asked to shift emphasis toward developing or adapting state policies. Due to this shift in focus, the two states that were awarded 2nd round funding were not required to include pilot demonstration projects as part of their work plans.

The role of the existing pilot projects shifted to using them as a platform for identifying and prioritizing systems change outcomes. Instead of focusing on demonstrating success at the local/regional level, states prioritized scaling up sustainable models for transition-to-work which could then be leveraged to inform systems collaboration and policy at a state level. This required bringing state agency representatives together at both the local/regional and statewide levels.

Additionally, the emphasis on policy change created challenges for some states, who did not initially have state agency representatives with that level of decision making authority participating in Consortium meetings. Although VR, IDD and Education state agencies signed a Memorandum of Understanding, which was a requirement for a state to apply for a PIE grant, some of the state agencies were not totally supportive when their Consortium began to recommend changes that would impact their agencies’ operations. Larger states with more complex governmental infrastructures, such as California and New York, were at a disadvantage due to a lack of existing mechanisms for statewide interagency collaboration and an enhanced need to focus on relationship building and trust between partners. Other states, such as Alaska, Wisconsin and Tennessee, entered the project with existing coalitions and long-standing relationships among a variety of stakeholders making the shift towards systems change easier to navigate. Still other states, such as Mississippi, Missouri and Iowa, had developed work plans that were grounded in grass roots involvement and local capacity building and needed to explore ways to connect local coalitions with the work of systems change at the state level.

As the PIE project progressed, states had opportunities to explore ways to collaborate across multiple and simultaneous systems-level initiatives. The Office of Disability Employment Policy’s Employment First State Leadership Mentor Program (EFSLMP) began the same year as PIE, with Iowa and Tennessee selected as prot

Having multiple systems change initiatives operating in parallel created an environment in which state agencies, regardless of their initial intent or willingness to focus on addressing policy and infrastructure barriers, had no choice but to look at systems change from both a top-down and bottom-up approach. This allowed for great flexibility for PIE states to adapt approaches to pilot demonstrations and larger systems change deliverables to move states towards Employment First policies. Individual state projects also embedded or collaborated with national initiatives including Cincinnati Children’s Hospital’s Project SEARCH and the U.S. Department of Education’s Transition and Postsecondary Programs for Students with Intellectual Disabilities (TPSID) projects.

1.7Policy context/timeline

Attention to state policy development was heightened due to swift and far-reaching federal policy actions that occurred simultaneously with the first PIE project phase, 2011–2016. On September 16, 2011, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued an Informational Bulletin providing guidance for employment and day services (CMS, 2011). This bulletin updated core service definitions, created new services to better reflect best practices, and emphasized the importance that employment plays in the lives of individuals with disabilities. Included in the bulletin were statements that underscored person centered planning as a component in employment services, and the important clarification of pre-vocational services as a time-limited service which can be used toward competitive employment. Most importantly, the bulletin defined the employment outcome as individual competitive integrated employment.

Three years later, CMS issued a Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) Settings Rule which has had substantial impact upon individuals, state agencies, and provider organizations. CMS was clear in its intentions: those receiving HCBS services under a Medicaid Waiver would have “full access to the benefits of community living and the opportunity to receive services in the most integrated setting appropriate” (2014). States were required to submit a transition plan by March 2015 that detailed how they would address compliance with the new rules, and to be in full compliance by March 2019.

Also in 2014, President Barack Obama signed the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). The legislation included amendments to the Rehabilitation Act and contained language that underscores the importance of transition to employment for youth with intellectual disabilities. WIOA addresses many of the challenges that the PIE projects were learning about and recommended some of the same policy changes that PIE states were attempting to resolve within their states with their state legislators, schools, VR agencies and service providers. However, the WIOA codified these changes, placing PIE projects in the position to advocate for its implementation. WIOA recognizes that youth with disabilities should have opportunities to learn and practice marketable skills by exploring real-work environments that will pave their way towards careers. It specifies state VR’s responsibility to support pre-employment transition services; it allows State VR agencies to prioritize serving students with disabilities, and it dedicates half of the Federal Supported Employment program funds to provide youth with the most significant disabilities with the supports they need, including extended services, to enable them to obtain competitive integrated employment (DOE 2014). WIOA clarifies the definition of competitive integrated employment as the desired outcome of VR and workforce services, and establishes rules under Section 511 that address participation in subminimum wage employment.

Olmstead cases in Rhode Island and Oregon drew considerable state attention. The State of Rhode Island agreed to a Settlement and Consent Decree with the United States Department of Justice in 2013 and 2014 after an investigation found that the State had violated the Americans with Disabilities Act by failing to serve individuals with IDD in integrated settings and placing youth with IDD at serious risk of segregation. The agreement binds Rhode Island to transform its service system over a 10-year time and includes annual benchmarks, and serves as precedent for other states. Meanwhile, another employment case between the State of Oregon and the Department of Justice was settled in December 2015. A class of individuals with IDD sued the state (Lane v. Brown) stating that it failed to provide supported employment services for those who were segregated in sheltered workshops, in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act. The agreement stated that the state would continue to reform its system including closing the “front door” or ending new admissions to workshops, certifying service providers, closer coordination between schools and post-secondary education or services, and increasing services resulting in competitive employment.

1.8Project outcomes

1.8.1State policy and infrastructure

Participating sites achieved a wide range of outcomes, including legislation, policy change, infrastructure change, and individual employment outcomes (Tucker, Feng, Gruman & Crossen, in press). Several of the project’s Consortia included Employment Policy Work Groups whose purpose was to bring policy ideas for consideration by the state’s full Consortium. Policy changes represented both high level state policy change, and significant operational changes including waiver changes, memorandums of understanding, funding restructuring, outcome-based management infrastructures, and provider manual changes. Initially, some of the states concentrated on Employment First policy, and over the span of the projects 5 of the 8 states enacted Employment First policies, either through legislation (Mississippi-2015, California-2013, and Alaska-2014) or a Governor’s Executive Order (Tennessee-2013 and New York-2014). Tennessee enacted legislation that makes scholarship support available to students with IDD who are participating in postsecondary education. An analysis of outcomes across state projects is presented by Tucker et al., and state outcomes are discussed in detail in individual state manuscripts.

1.8.2Impact on policy systems change and guidance

A few of the PIE state projects prepared written analyses of current state policies and systemic barriers that hampered youth with IDD receiving work based learning opportunities in high school or exiting high school with a job or receiving post-secondary education or training. These analyses were shared with their Consortium members and were constructive for shaping policy goals. Policy analyses helped to direct advocacy efforts particularly when states had passed legislation but the laws were not being followed in practice in whole or in part. As the state projects became more embedded into policy development and enactment, several PIE project staff determined that federal policies or regulations required attention concurrent with state systems change.

1.8.3Impact on services

Sustainable systems change occurs over a long timeframe, and requires change that is embedded in each of the primary systems elements defined in the higher performing states model (Hall et al., 2007). While the AIDD expectation was for observable change in policy and infrastructure, the project defined a framework for outcome and process measures for states (see Table 2), and where available tracked change in outcomes using nationally available data. Data that represents the experiences of individuals with IDD across states is limited, and includes the National Survey of State IDD Agency Day and Employment Services, and the Rehabilitation Services Administration 911 database. The National Core Indicators project provides rich data on employment and other outcomes, but did not have enough states enrolled at the start of the PIE initiative to compare states. Finally, there is a significant need for reliable data on outcomes of education services. Currently, most states do not make IDEA indicators available by disability, limiting the usefulness of those data.

Table 2

Framework for outcome and process measures

| Outcome measures | Process measures |

| State IDD Agency | State IDD agency |

| ❖ Percent in employment services (ICI) | ❖ Has goal in ISP (NCI, state MIS) |

| ❖ Percent employed (State outcome data, NCI) | State VR Agency |

| ❖ Wages, hours worked | ❖ Percent of VR caseload |

| State VR Agency | ❖ Referrals from education |

| ❖ Closures into employment (RSA 911) | ❖ # in pre-employment transition services |

| ❖ Wages, hours worked | Education |

| Education | ❖ # in paid employment experiences |

| ❖ Number employed (Indicator 14) |

National data suggest that participation in integrated employment services supported by state IDD agencies in PIE states grew slightly, from 16.4% to 16.7%, between FY2010 and FY2014, while participation in integrated employment services declined for other states from 25.9% to 25.5%. Similar trends were observed for state VR agencies, with PIE states outperforming non-PIE states for the number closed into employment, the percent of closures successfully closed into employment, and the percent of persons with ID compared to all VR closures for both 16 to 21 year olds and 22 to 30 year olds (see Table 3).

Table 3

Vocational rehabilitation closures for persons with an intellectual disability: comparison of PIE states and non-PIE states. Source: RSA 911

| 16–21 | 22–30 | ||||||

| 2010 | 2014 | Percent change | 2010 | 2014 | Percent change | ||

| Number closed into employment | PIE | 5254 | 5471 | 8% | 1115 | 1373 | 23% |

| Not PIE | 1747 | 1892 | 4% | 2443 | 2911 | 19% | |

| Percent closed into employment | PIE | 26.2% | 36.2% | 38.2% | 33.9% | 43.4% | 28.0% |

| Not PIE | 29.6% | 34.5% | 16.6% | 33.8% | 38.8% | 14.8% | |

| Percent of persons with ID compared to all closures | PIE | 18.2% | 16.8% | –7.7% | 14.0% | 15.8% | 12.9% |

| Not PIE | 15.3% | 12.9% | –15.7% | 10.1% | 10.6% | 5.0% | |

1.8.4Federal policy recommendations and advocacy

The PIE initiative community as a collective engaged in considerable advocacy at the federal level, including soliciting guidance on application of least restrictive environment to transition and employment experiences, meetings with leadership staff of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Rehabilitation Services Administration, Office of Special Education Programs, Administration for Community Living, Social Security Administration, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, and the Office of Disability Employment Programs at the Department of Labor, state project representation on the WIOA Advisory Committee on Increasing Competitive Integrated Employment for Individuals with Disabilities, and consultation to the WIOA committee. In response to Senator Tom Harkin’s (D-IA) Six by Fifteen campaign to improve the lives of people with disabilities across the country, the PIE community developed specific recommendations drawn from their project experience (see Table 4), which directed the project’s federal advocacy in the final two years of the project.

Table 4

Partnerships Project recommendations by Six by 15 goal

| Goal | Recommendations |

| Transition | 1. Early connection to developmental disabilities and vocational rehabilitation agencies should be formalized and required. Federal agencies should jointly issue guidance on best practices for collaboration in serving youth. |

| 2. Interagency coordination between the State Education Agency, State Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, and the state Medicaid Agency or Long-Term Care Developmental Disabilities Agency must be mandated. Federal agencies must provide implementation guidance. | |

| 3. Redefine “Highly Qualified Special Education Teacher” to reflect the unique skills necessary to effectively provide and plan for required transition services that lead to employment outcomes. Require states to adopt transition competencies as part of teacher certification. | |

| Employment | 4. Require independent living goals in transition planning for all youth that address understanding of benefits, work incentives and asset development. Develop interagency guidance on how to access work incentives benefits counseling services at the earliest possible stages of transition planning. Incentivize and require benefits counseling across publicly funded programs as a mandated service prior to accessing other benefits. |

| 5. Require RSA to develop standards and indicators for VR in serving transition-age youth, including youth with significant disabilities. | |

| 6. Promote and fund pre-service training for professionals emphasizing parent engagement strategies and focusing on building high expectations related to employment. Tie professional certifications and Medicaid provider qualifications to specific competencies related to understanding employment opportunities for Medicaid beneficiaries. | |

| 7. Incentivize development and scale-up of youth-targeted promising practices, like On-The-Job Training (Youth-OJT) initiatives across all states. | |

| Education | 8. Issue additional guidance and clarification related to least restrictive environment (LRE) in work placements for transition-age youth. |

| 9. Issue guidance on data collection and analysis related to postsecondary outcomes (Indicator 14). Make Indicator 14 data collection annual and mandatory. | |

| 10. Issue guidance to promote inclusive education settings in high school and align instruction with Common Core Standards. | |

| 11. Issue guidance and update regulation where necessary to clarify how Extended School Year (ESY) policies and FAPE apply to use of ESY services to sustain youth employment and maintain progress in acquisition of employment skills. | |

| 12. Change RSA Metrics and Performance Indicators Relating to Transition. | |

| Health Living | 13. Change and clarify Medicaid policy to allow for personal care on the job, for personal care workers to simultaneously serve as job coaches, and for job coaches to be allowed to provide and be paid for personal care. Core competencies and Medicaid provider qualifications must include understanding of how non-work services support employment. Issue related guidance to inform state policies and practice. |

| Community Lives | 14. Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRCs) and other federally funded “No Wrong Door” options must extend their focus to be available as one-stop information centers and provide reliable information to youth and families about long-term supports and community living options that can inform choices at earlier stages. |

| 15. Provide clear guidance on how states must develop a full range of community-based supports in all service categories: non-work day services, pre-vocational services, and vocational services to build a full day of community-integrated activities for individuals using long-term supports. | |

| Early Childhood | 16. Update pre-service curriculum, core competencies and standards for the early childhood and other pediatric medical and social service professions to emphasize inclusive education and the goal of competitive employment as the preferred option for individuals with disabilities including methods for communicating these options to families. |

1.9Lessons learned

1.9.1Importance of a backbone organization

State projects universally demonstrated the power of relationships and communication as a platform for change, and as the first six PIE projects finished their fifth year we began to integrate the concept of a backbone organization as developed by the collective impact movement. One of the five conditions for collective impact states that, “Creating and managing collective impact requires a separate organization(s) with staff and a specific set of skills to serve as the backbone for the entire initiative ... The expectation that collaboration can occur without a supporting infrastructure is one of the most frequent reasons it fails” (Kania & Kramer, 2011, p. 40). The role of a backbone organization in the collective impact movement recognizes that collaboration requires real work and supports. The managing organization for the PIE projects served this role as a convener, manager, and facilitator for their consortia. Tucker, Feng, Gruman & Crossen in this issue note that “all states acknowledged the PIE grant has resulted in strong cross-agency relationships that did not exist before the project.”

1.9.2A long-term view on opportunity

Systems change is a long process, extending well beyond the scope of a 5-year project. State consortia built shared commitment and goals that in some cases led to immediate action, and in other cases prepared the ground for action when an opportunity emerged as leadership and state priorities evolved. States all focused on the key elements of the high performing states model, but took different paths in how they placed emphasis based on state priorities and opportunities.

This lesson also indicates the importance of a long-term commitment to collaboration, support for a backbone organization, and key elements such as capacity building investments and data collection.

1.9.3The need to address capacity building policy

While a key part of achieving systems change is providing training and technical assistance to build the capacity of the direct support workforce and community provider infrastructure, project’s work illustrated the difference between committing short term resources to training and developing a long term strategy for training infrastructure. State projects addressed policy by establishing long term investments in training and amending policy such as the provider qualification requirements for state services.

1.9.4Data as a communication mechanism

States both harnessed existing data to illustrate priorities and progress, and worked to implement robust data collection on individual outcomes. These efforts played an important role not just in describing challenges and progress, but in supporting conversations within the state consortia to develop common definitions and understanding of employment outcomes.

1.9.5Integration of initiatives

The collaborative nature of the PIE projects allowed states to integrate and coordinate multiple initiatives including PIE, membership in the State Employment Leadership Network, participation in the ODEP EFSLMP, and related initiatives such as PROMISE grants and Disability Employment Initiative projects.

1.9.6Linking local implementation and state policy

A strong communication link between local practice and state policy was an important tool in understanding the impact of policy and infrastructure on local implementation. State projects were effective at engaging pilot projects and local stakeholders to inform change at a state policy and infrastructure level.

1.9.7Communication requires investment

State consortia used clear intentional strategies to engage stakeholders, including using independent facilitators for meetings, coaching self advocates to be full participants in consortia events, and implementing community conversations as a strategy for informing their work and engaging stakeholders.

1.9.8State policy framework for transition

These lessons led to an expansion of the high performing states model to reflect the importance of intentional investment in relationships and connecting activities that link stakeholders across state governmental systems change, local implementation, and advocacy (see Fig. 1).

Fig.1

State policy framework for transition.

1.10Overview of the issue

This issue reflects the investment of the members and stakeholders in the AIDD Partnerships in Employment initiative in systems change that creates sustainable and meaningful policy and infrastructure at the state level, and supports quality employment outcomes and implementation of effective practices at a local level. The initiative was remarkable for the level of commitment by participants not only to their own work plan, but to participating in and supporting a community of practice that openly shared challenges, strategies, and successes, and extended lessons learned to policy recommendations and advocacy at the federal level. Articles that follow address a cross state analysis of the project by the evaluation team and project officer, and a detailed description of the approach used by each participating state. States provide background and state context for their initiative, their project structure and goals, action plans, outcomes, how they addressed sustainability, and lessons learned. Collectively these represent a rich investment in true systems change.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

Acknowledgments

Development of this manuscript was funded in part by Grant Numbers 90DN0290 and 90DN0289 from the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, Administration on Community Living, US Department of Health and Human Services. The opinions contained in this manuscript are those of the grantees and do not necessarily reflect those of the funder. The authors thank the members of the Partnerships in Employment community for a unique collaborative effort, including partners in the 8 state projects, AIDD, the Lewin Group, and members of the technical assistance team at the Institute for Community Inclusion and National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services.

References

1 | Almutairi R. A. ((2016) ). Parent perceptions of transition services effectiveness for students with intellectual disabilities. International Interdisciplinary Journal of Education, 5: (6), 1–9. |

2 | Barrows M., Billehus J., Britton J., Hall A. C., Huereña J., LeBlanc N., & … Topper K. ((2015) ). The truth comes from us: Supporting workers with developmental disabilities. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=ici_pubs |

3 | Blustein C. L., Carter E. W., & McMillan E. D. ((2016) ). The voices of parents: Post-high school expectations, priorities, and concerns for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/0022466916641381 |

4 | Butterworth J., & Migliore A. ((2015) ). Trends in employment outcomes of young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, 2006-2013. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts, Institute for Community Inclusion. |

5 | Butterworth J., Smith F.A., Winsor J., Ciulla Timmons J., Migliore A., & Domin D. ((2016) ). StateData: The national report on employment services and outcomes. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion. |

6 | Callahan M., Butterworth J., Boone J., Condon E., & Luecking R. ((2014) ). Ensuring employment outcomes: Preparing students for a working life. In Agra M., Brown F., Hughes C., Quirk C., & Ryndak D. (Eds), Equity and full participation for individuals with severe disabilities: A vision for the Future, Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. |

7 | Carter E., Ditchman N., Sun Y., Trainor A., Swedeen B., & Owens L. ((2010) ). Summer employment and community experiences of transition-age youth with severe disabilities. Exceptional Children, 76: (2), 194–212. |

8 | Carter E., Austin D., & Trainor A. ((2011) ). Factors associated with the early work experiences of adolescents with severe disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49: (40), 233–247. |

9 | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. ((2011) ). CMCS Informational Bulletin: Updates to the §1915 (c) Waiver Instructions and Technical Guide regarding employment and employment related services. Retrieved from http://downloads.cms.gov/cmsgov/archived-downloads/CMCSBulletins/downloads/CIB-9-16-11.pdf |

10 | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. ((2014) ). Medicaid Program; State Plan Home and Community-Based Services, 5-Year Period for Waivers, Provider Payment Reassignment, and Home and Community-Based Setting Requirements for Community First Choice (Section 1915(k) of the Act) and Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Waivers (Section 1915(c) of the Act). Retrieved from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/long-term-services-and-supports/home-and-community-based-services/downloads/final-rule-slides-01292014.pdf |

11 | Certo N. J., Mautz D., Pumpian I., Sax C., Smalley T., Wade H., & Batterman N. ((2003) ). A review and discussion of a model for seamless transition to adulthood. Education & Training in Developmental Disabilities, 38: (1), 3–17. |

12 | Certo N. J., Luecking R. G., Murphy S., Brown L., Courey S., & Belanger D. ((2008) ). Seamless transition and long-term support for individuals with severe intellectual disabilities. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 33: (3), 85–95. |

13 | Grigal M., Hart D., & Migliore A. ((2011) ). Comparing the transition planning, postsecondary education, and employment outcomes of students with intellectual and other disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 34: (1), 4–17. |

14 | Haber M. G., Mazzotti V. L., Mustian A. L., Rowe D. A., Bartholomew A. L., Test D. W., & Fowler C. H. ((2016) ). What works, when, for whom, and with whom: A meta-analytic review of predictors of postsecondary success for students with disabilities. Review of Educational Research, 86: (1), 123–162. |

15 | Hall A. C., Butterworth J., Winsor J., Gilmore D., & Metzel D. ((2007) ). Pushing the employment agenda: Case study research of high performing states in integrated employment. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 43: (3), 182–198. |

16 | Hall A. C., & Kramer J. ((2009) ). Social capital through workplace connections: Opportunities for workers with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Social Work in Disability and Rehabilitation, 8: (3), 146–170. |

17 | Hart D., Zimbrich K., & Whelley T. ((2002) ). Challenges in coordinating and managing services and supports in secondary and postsecondary options. Issue Brief, 1(6). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, Institute on Community Integration, National Center on Secondary Education and Transition. Retrieved from t: http://www.ncset.org/publications/viewdesc.asp?id=719 |

18 | Henninger N. A., & Taylor J. L. ((2014) ). Family perspectives on a successful transition to adulthood for individuals with disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 52: (2), 98–111. |

19 | Hetherington S. A., Durant-Jones L., Johnson K., Nolan K., Smith E., Taylor-Brown S., & Tuttle J. ((2010) ). The lived experiences of adolescents with disabilities and their parents in transition planning. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 25: (3), 163–172. |

20 | Human Services Research Institute & the Institute for Community Inclusion. ((2011) ). Participation in Integrated Employment: National Core Indicators Project, 2009-2010. Unpublished data. |

21 | Human Services Research Institute & the Institute for Community Inclusion. ((2016) ). Working in the Community: The Status and Outcomes of People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in Integrated Employment – Update 2. Retrieved from http://www.nationalcoreindicators.org/upload/core-indicators/NCI_DataBrief_Employment_Update_2014_2015edit_6_28_2016.pdf |

22 | Kania J., & Kramer M. ((2011) ). Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9: (1), 36–41. |

23 | Luecking R. G., & Wittenburg M. ((2009) ). Providing supports to youth with disabilities transitioning to adulthood: Case descriptions from the Youth Transition Demonstration. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 30: , 241–251. |

24 | Mank D., Cioffi A., & Yovanoff P. ((2003) ). Supported employment outcomes across a decade: Is there evidence of improvement in the quality of implementation? Mental Retardation, 41: (3), 188–197. |

25 | Martinez J., Fraker T., Manno M., Baird P., Mamun A., O’Day B., Rangarajan A., & Wittenburg D. ((2010) ). The Social Security Administration’s Youth Transition Demonstration Projects: Implementation lessons from the original projects. Washington, D.C.: Mathematica Policy Research. |

26 | Mazzotti V. L., & Plotner A. J. ((2016) ). Implementing secondary transition evidence-based practices: A multi-state survey of transition service providers. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 39: (1), 12–22. |

27 | Migliore A., Mank D., Grossi T., & Rogan P. ((2007) ). Integrated employment or sheltered workshops: Preferences of adults with intellectual disabilities, their families, and staff. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 26: (1), 5–19. |

28 | Migliore A., Butterworth J., Nord D., Cox M., & Gelb A. ((2012) ). Implementation of job development practices. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50: (3), 207–218. |

29 | National Council on Disability (NCD). ((2008) ). The Rehabilitation Act: Outcomes for transition age youth. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.ncd.gov/policy/education |

30 | National Longitudinal Transition Study-2. (n.d.). Data tables. Retrieved from http://www.nlts2.org/data_tables/index.html |

31 | Nonnemacher S. L., & Bambara L. M. ((2011) ). I’m supposed to be in charge”: Self-advocates’ perspectives on their self-determination support needs. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49: (5), 327–340. |

32 | Oertle K. M., & Seader K. J. ((2015) ). Research and practical considerations for rehabilitation transition collaboration. Journal of Rehabilitation, 81: (2), 3–18. |

33 | Partnerships in Employment Technical Assistance Center. ((2015) ). Building a transition agenda aligned with “Six by ‘15” goals. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion |

34 | Plotner A. J., & Marshall K. J. ((2015) ). Supporting postsecondary education programs for individuals with an intellectual disability: Role of the vocational rehabilitation counselor. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 1–18. |

35 | Rusch F. R., & Braddock D. ((2004) ). Adult day programs versus supported employment (1988-2002): Spending and service practices of mental retardation and developmental disabilities state agencies. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 29: , 237–242. |

36 | Shogren K. A., & Plotner A. J. ((2012) ). Transition planning for students with intellectual disability, autism, or other disabilities: Data from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50: (1), 16–30. |

37 | Stevenson B. S., & Fowler C. H. ((2016) ). Collaborative assessment for employment planning: Transition assessment and the discovery process. Career Developmental and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 39: (1), 57–62. |

38 | State Employment Leadership Network. ((2016) ). Accomplishments report membership year 2015-2016, Report of State Initiatives and Activities to Improve Integrated Employment Outcomes. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion. |

39 | Test D. W., Fowler C. H., & Kohler P. ((2013) ), Evidence-based practices and predictors in secondary transition: What we know and what we still need to know. Charlotte, NC: National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center. |

40 | Timmons J. C., Hall A. C., Bose J., Wolfe A., & Winsor J. ((2011) ). Choosing Employment: Factors that impact employment decisions for individuals with intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49: (4), 285–299. |

41 | Tucker K., Feng H., Gruman G., & Crossen L. ((2017) ). Improving competitive integrated employment for youth and young adults with disabilities: Findings from an evaluation of eight Partnerships in Employment Systems Change Projects. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 47: (3). |

42 | Walker A. ((2011) ). Checkmate! A self-advocate’s journey through the world of employment. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49: (4), 310–312. |

43 | Winsor J., Butterworth J., Lugas J., & Hall A. ((2010) ). Washington State Division of Developmental Disabilities Jobs by 21 Partnership Project Report for FY 2009. Boston, MA: Institute for Community Inclusion. |

44 | Winsor J., Butterworth J., & Boone J. ((2011) ). Jobs by 21 Partnership Project: Impact of cross-system collaboration on employment outcomes of young adults with developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49: (4), 274–284. |