Improving Quality Improvement: 4 years of international medical QI conferences

1.Introduction

Quality Improvement (QI) is a key agenda for change item recognised as fundamental to the success of healthcare systems by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. QI can be defined as the systematic process to identify problems, evoke change, and improve standards. The outcomes of any QI process should be improved safety, better co-ordination of care and improved satisfaction amongst patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs) [1]. There are methodologies such as the ‘Plan-Do-Study-Act PDSA cycle’ and ‘Lean processing’, that help identify areas requiring improvement and allow for trials of potential solutions [2]. However, awareness of these processes is not absolute for HCPs, it is therefore imperative that fundamental QI principles are taught and encouraged and that HCPs have a means of collaborating.

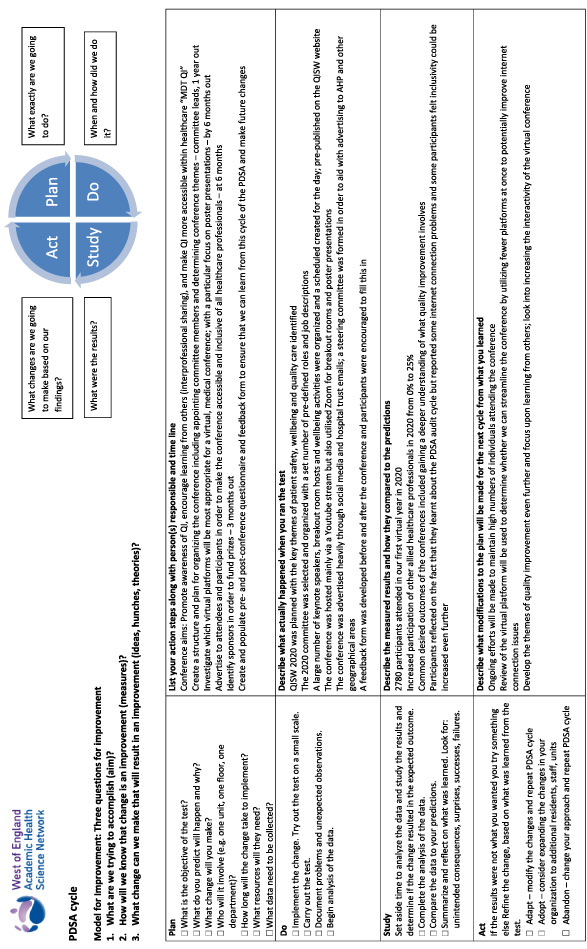

Medical conferences remain the main mechanism for continuing professional development and educating healthcare professionals on updates and innovation [3]. Combinations of lectures, workshops, presentations and informal interactions with peers allows for the development of standards within healthcare [4]. The Quality Improvement South West (QISW) international conference was created in order to promote awareness of QI, encourage learning from others, and make QI more accessible within healthcare. It ran face-to-face in 2019 and then virtual in subsequent years (2020, 2021 and 2022). Utilising multiple PDSA cycles (see Appendix A) and our conference checklist (see Appendix B) we have not only produced a high quality and open access conference for thousands of attendees but also improved year to year in terms of quality and learning efficiency.

The aim of this paper is to review the results from the application of a PDSA cycle process to QI conferences. The secondary aim is to demonstrate non inferiority of virtual QI conferences to in person conferences in terms of learning outcomes.

2.Methods

Review of conference participant data, comparisons of pre and post conference questionnaires, assessment of common themes throughout the conference and year to year comparisons of confidence in QI methodology.

3.Results

3.1.Number and specialism of participants, pre-conference and post-conference feedback completion

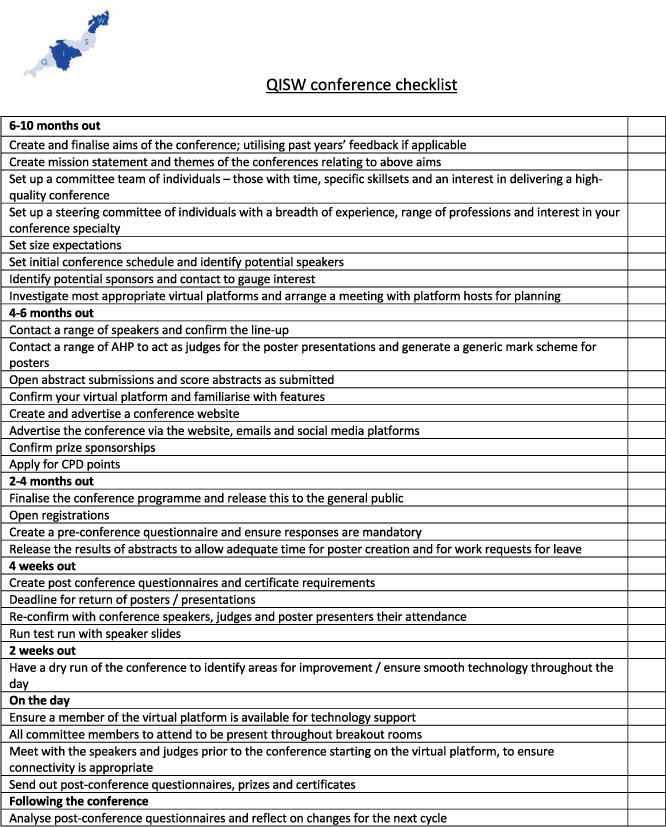

The first year (2019) of QISW had 153 participants of these 88% were doctors and 12% students. 2020 substantially increased in size with 2780 participants of which 33% were doctors, 10% nurses, 22% students, and 35% allied health professionals including physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, QI practitioners, and and senior managers. The following two years had 500 and 178 participants with 68% and 65% being doctors respectively (see Fig. 1). The pre- and post-conference feedback surveys were utilised to develop key themes and areas for improvement for subsequent years. In 2019, 101 individuals completed the pre-conference survey and 40 completed the post-conference survey. In the following years the pre-conference survey numbers were 639, 60 and 277 respectively. Post-conference survey figures were 361, 127 and 114 respectively.

Fig. 1.

Percentage breakdown of yearly attendance by healthcare profession.

3.2.Common themes

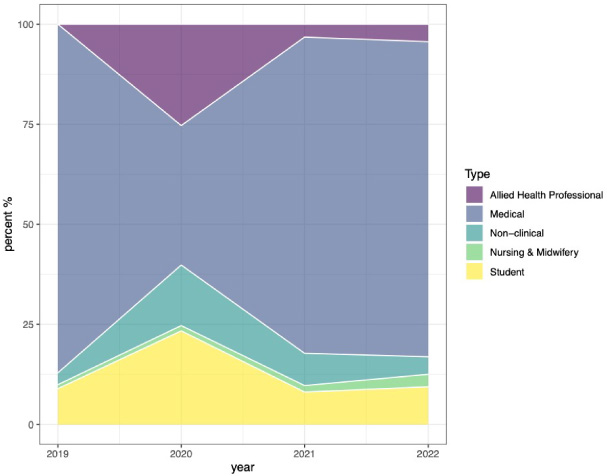

The results of the pre and post conference surveys were analysed for key themes. These were transferred into word cloud maps to represent what participants wanted to achieve by attending the conference (see Fig. 2 as an example) and how they thought the conference could improve. As the conference developed the aims changed as our participants’ understanding of QI principles improved.

In the pre-conference questionnaire, each year participants were asked demographic data, confidence in QI methodologies, level of experience with leading or participating in QI projects and what they hoped to achieve from the conference. Post conference questionnaires focused on self-scored improvement of their confidence in QI methodology, willingness to lead on a QI project, and how they thought the conference could improve as well as key messages they took away from the conference. Below we have highlighted the top three themes by year in response to ‘what do you hope to achieve from the conference’ and ‘how do you think the conference could improve’. We have also given an example of how we displayed these in word clouds for committee review (Fig. 2).

Pre-conference:

2019:

What is quality improvement

What makes up an effective quality improvement project

Ideas and examples of previous projects

2020:

Deepening the basic knowledge of QI

Understanding how to undertake better QI projects

How does quality improvement relate to patient safety

2021:

Learning from others

Ability to network with individuals

Opportunity to share research

2022:

How to present QI work

Hear inspirational QI projects

Learn how to create a good QI organisation

Fig. 2.

Word cloud of 2020 pre-conference expectations.

Post-conference:

2019:

Continue excellent quality of speakers

Improve opportunities for discussions surrounding QI

Improve networking amongst others

2020:

Greater understanding of the QI process including understanding of the PDSA cycle

Greater publicity of the conference

Improved inclusivity of the conference

2021:

Availability of more workshops

Technical issues with hosting platform

The lack of interaction available with the oral presentations

2022:

Importance of diversity for quality improvement

Request for the conference to return to a face-to-face or hybrid setting

Having specific time allocated for the poster hall

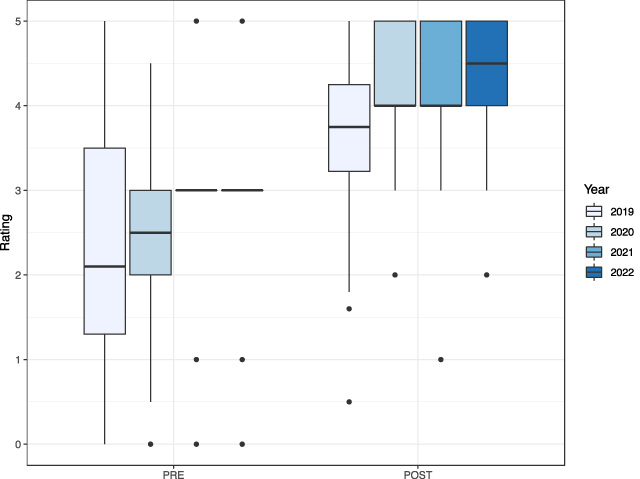

3.3.Pre- and post-conference QI methodology confidence scores

Each year conference participants were asked to self-score their pre- and post-conference confidence scores about understanding of QI methodologies. Across the four years the average pre-conference confidence increased from ‘2.1’ in 2019 to ‘2.5’ in 2020 and ‘3’ in 2021 and 2022. Each year confidence improved between the pre- and post-conference surveys. The post-conference survey also increased throughout the years from 3.75 in 2019 to 4.5 in 2022.

Fig. 3.

Box plot demonstrating yearly pre and post conference confidence in QI methodologies.

3.4.Comparison of virtual to face-to-face learning

When comparing pre-vs post 2019 (in person conference) to pre-vs post 2020-22 (virtual conferences) improvement factor, there was 1.23 (P < 0.001) improvement pre-and post 2019 and 1.57 (P < 0.001) for the virtual conferences (2 way ANOVA), but there was no significant statistical difference between the two values. There were no significant thematic variations when reviewing free word box statements from attendees, all included opportunities to network as an important aspect of the conference participation.

4.Discussion

4.1.PDSA cycle application to conferences

Our results demonstrate a continued improvement in the delivery and content of our conferences in keeping with our aim of teaching QI principles and improving understanding and confidence in QI methodologies. We have included our PDSA cycle (see Appendix A) and would encourage those who run annual conferences to implement regular Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles to improve the quality of their conference. We were able to demonstrate improvements in our pre-and post-conference QI methodology scores and our thematic analysis shows a shift from learning the principles of QI methodology to implementation. We have developed a conference checklist as part of the planning stage of any conference (Appendix B).

4.2.The demand for virtual conferences

The first Quality Improvement Southwest international conference was organised and run as a face-to-face conference in 2019. The COVID-19 pandemic required significant changes to the structure and delivery of educational material. The introduction of international travel restrictions further threatened the inclusion of international delegates and speakers. To overcome the associated safety risks, subsequent pressures on the NHS, and barriers to travel, virtual conferences were developed as a solution [5]. QISW has run its subsequent conferences virtually thus reducing carbon footprint, improving attendance, and removing barriers for Low- or Middle-Income Countries. This was largely supported by the use of a virtual conference platform MedAll (Medicinall Limited) with features such as the ‘virtual poster hall’ and the use of multiple broadcasting ‘virtual stages’. It has been demonstrated that effective and easily accessible audiovisual platforms are necessary to the development and delivery of virtual conferences [6].

5.Conclusion

We have demonstrated continued improvement with the delivery of our QI conferences. We have outlined the steps to apply PDSA cycles to annual conferences as well as step-by-step guidance on how to run and deliver a conference. We have proved non-inferiority of virtual conferences to face-to-face conferences as our data has demonstrated that it is possible to run virtual conferences to the same if not higher standard than face-to-face conferences with similar or superior attendance numbers and engagement with the learning process.

QISW remains a learning organisation and we will continue to work on expanding our inclusivity, especially on a global scale, with improved accessibility through virtual platforms.

Acknowledgements

Miss Anne Pullyblank, Medical Director, West of England Academic Health Science Network; Dr Seema Srivastava MBE, Deputy Medical Director, University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust; Mr Simon Sinek, Author and Speaker, Start with Why; Donna Paddon, Medical Education, North Bristol NHS Trust; Vardeep Deogan and the Quality Improvement Team, North Bristol NHS Trust; Phil McEnlay, CEO, MedAll global accessible healthcare platform.

References

[1] | Jones B, Vaux E, Olsson-Brown A. How to get started in quality improvement. BMJ [Internet]. (2019) ;364: , Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/364/bmj.k5437. |

[2] | Quality improvement made simple [Internet]. 3rd ed. The Health Foundation; 2021 Apr [cited 2022 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/quality-improvement-made-simple. |

[3] | Mishra S. Do medical conferences have a role to play? Sharpen the saw. Indian Heart J. (2016) ;68: (2):111–3. |

[4] | Kamal M, Bhargava S, Katyal S. Role of conferences and continuing medical education (CME) in post-graduate anaesthesia education. Indian J Anaesth. (2022) ;66: (1):82–4. |

[5] | Palethorpe MK. Time for face-to-face medical conferences and hybrid events. BMJ. (2022) ;24: :376, 761. |

[6] | Rundle CW, Husayn SS, Dellavalle RP. Orchestrating a virtual conference amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Online J. (2020) ;26: (7), 13030/qt5h19t1jx. |

Appendices

Appendix A.

Appendix A.Example PDSA cycle

Appendix B.

Appendix B.QISW conference checklist