Improving communication at NHS Nightingale Hospital North West: Medical updates to next of kin

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The Nightingale North West (NNW) was a UK temporary field hospital set up during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policies and standard operating procedures were undeveloped. Visitors were permitted only in exceptional circumstances, resulting in heightened anxiety for patients and next of kin (NOK).

OBJECTIVE:

Recognising the importance of effective NOK communication, a quality improvement project (QIP) was undertaken to improve communication between doctors and NOK.

METHOD:

NOK satisfaction with communication received from doctors (scored 1–5) was the primary outcome measure and data was collected through standardised phone-calls.

A wide four point (1–5) variability in satisfaction was identified.

PDSA methodology was used to introduce interventions: (1) ‘Gold standard’ for frequency of NOK updates; (2) Record date of NOK update on the doctors’ list.

RESULTS:

Early post-intervention data showed reduced variability in satisfaction with 82% of NOK scoring ‘4’ or ‘5’. Process measures demonstrated excellent uptake of interventions.

CONCLUSION:

Conclusions are limited by the project’s short time-frame but there is a promising role for these interventions in enhancing doctor-NOK communication.

1.Background

The Nightingale North West (NNW) was a UK temporary field hospital established during the COVID-19 pandemic. This setting was unfamiliar to staff, patients and their families. Visitors were only permitted under exceptional circumstances; when a patient was ‘end of life,’ leading to heightened anxiety for patients and NOK. This reduced opportunity to gain collateral history and involve next of kin (NOK) in decision-making. This was pertinent in the patient cohort at NNW who were elderly, frail with multiple comorbidities. Given that most complaints can be attributed to poor communication [1], it was important to mitigate these barriers. NNW was relatively undeveloped in its policies and we recognised the importance of establishing high standards of communication with NOK.

Poor standards of doctor-NOK communication can negatively impact on holistic care, whereas effective communication often enables a greater shared understanding of a patients’ history and social situation [2]. In more vulnerable patients (akin to those at NNW), there is greater emphasis on collateral history in guiding safe and appropriate decision making [2,3]. Furthermore, clear communication with NOK is important in facilitating safe patient discharges [4]. Doctor-NOK communication has been recognised as an area for improvement in the care of end of life patients in hospital [5]. Causative factors are discussed, such as a culture within the NHS that encourages efficiency and does not, within the constraints of a normal working day, account for time spent talking to NOK [5].

The notion that enhanced communication corresponds with greater NOK satisfaction is well established [2,5]. The impact of structured systems for NOK communication on wider clinical outcomes is more debated. One study in intensive care did not demonstrate positive correlation with various clinical outcomes [6], whilst similar interventions in paediatrics led to a significant reduction in harmful medical errors [7].

Structured communication with NOK has been shown to enable exchange of information and shared decision-making [8]. These tools offer potential in non-visiting settings, to overcome challenges caused by mismatched perceptions of the situation [9]. Hospital admissions in non-visiting settings precipitate feelings of isolation for many patients, paradoxically leading to a greater reliance on NOK for emotional well-being [9]. ‘Family liaison teams’ (FLT), assigned to facilitate daily telephone or video contact between patients and families, have been implemented at the NNW and elsewhere to support this [10].

The objective of this quality improvement project (QIP) was to enhance communication with NOK. The refined aim was to reduce variability in NOK satisfaction specifically regarding communication with doctors. In the context of a ‘1-5 satisfaction scale’, this was to minimise variability to 2 points or less, such that scores were consistently between 3 and 5. With guidance from senior colleagues and consideration of various factors, including the generally robust staffing levels, our objectives were achievable and realistic. We sought to implement these improvements over the course of eight weeks whilst working at NNW.

2.Methods

A preliminary NOK survey was conducted to guide the objective of the main QIP.

The QIP outcome measure was NOK satisfaction with communication received from doctors, on a scale of 1-5; 1=‘very unsatisfied’, 2=‘unsatisfied’, 3=‘average’, 4=‘satisfied’, 5=‘very satisfied’. This scale was also used for collecting data on satisfaction with the FLT. Qualitative feedback was collected. Data was gathered via standardised phone-calls to NOK across June 2020.

Inclusion criteria: NOK of patients with a length of stay of at least seven days.

Exclusion criteria: End of life/bereaved cases. A randomised number generator selected NOK to be contacted. Staff collecting data were not those directly involved in the patients’ care to minimise bias.

Initial data was plotted on a run chart, highlighting wide variability in satisfaction.

Causes were illustrated through a process map. A reverse driver diagram identified potential interventions:

Set ‘gold standard’ for frequency of NOK medical updates

Update date of most recent NOK medical update on doctors list

Implement an MDT communication sheet

Run a teaching session on NOK communication

Set individualised standards for NOK updates.

Discussion was held with senior management to ensure new standards were appropriate and sustainable in view of staffing. Interventions were communicated at medical handover and in staff induction programmes.

Due to NNW’s temporary nature, rapid implementation of interventions was needed.

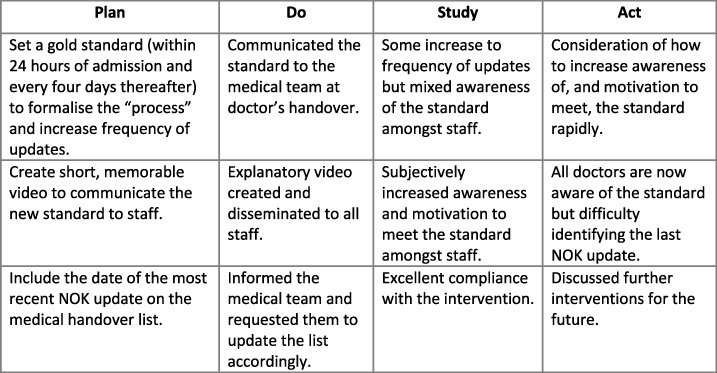

We implemented three interventions through PDSA cycles (Fig. 1). Intervention one was introduced, followed by a further intervention of disseminating a light-hearted, informative video to promote it. Intervention two was then introduced.

Fig. 1.

The PDSA cycles which we undertook.

Process measure one was adherence to the ‘gold standard’ of updating NOK every four days. This data was collected from medical notes in parallel with baseline data. Process measure two monitored compliance with accurately updating the doctor’s list; this was assessed daily from the intervention onwards.

Feedback was sought from 28 MDT members on non-trialled interventions with the majority advocating for an MDT communication sheet as the most effective potential future intervention.

3.Results

The initial survey highlighted substantial variability in NOK experience.

Inconsistent frequency of NOK medical updates was notable, with the proportion of days during patients’ stay where NOK received medical updates varying from 0–40%. 44% were not informed on the rationale for patients’ move to NNW. Conversely, 95% were communicating with their relatives via their preferred mode, facilitated by the FLT.

Main QIP: Initial 17 datasets identified 4 points of variability of NOK satisfaction (ranging 1–5). Qualitative data indicated that less satisfied NOK often reported lower frequency of communication. Another common theme was inconsistency in information received.

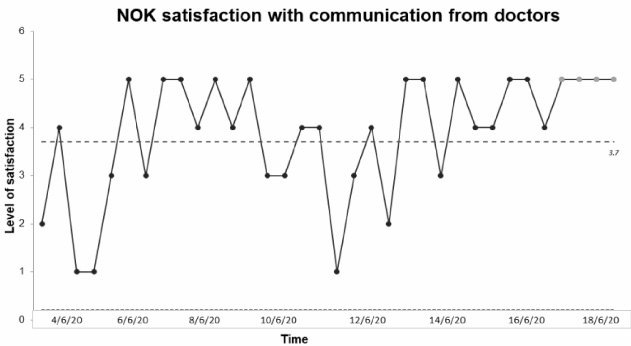

NOK satisfaction with FLT was consistently scored as ‘4’ or ‘5.’ A further 17 datasets were obtained following interventions. Early post-intervention data demonstrates reduced variability in NOK satisfaction to 2 points, with 82% of NOK reporting satisfaction as ‘4’ or ‘5’. This indicates improvement from baseline data (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

SPS chart illustrating variability of NOK satisfaction over continuous time period.

Process measures demonstrate an increase in NOK receiving medical updates every 4 days from a baseline of 35% to 74% (2 days following intervention one). Overall adherence by the end of our QIP was 81%; potentially boosted by the promotional video. Compliance to accurately updating the doctors’ list was 96%. Excellent uptake emphasises the role of these interventions in enhancing NOK satisfaction. We were unable to measure compliance to the ‘gold standard’ of updating NOK within 24 hours of admission, as no further patients were admitted to NNW due to its transition into standby mode.

Associated costs were time spent updating NOK which is difficult to quantify. Logistical challenges arose if NOK were harder to contact via telephone. Given the generally low patient to staff ratio, this was not a major issue during this project, but would warrant consideration in other settings.

4.Conclusion

Early data indicates encouraging improvement in doctor-NOK communication, with the specific aim of reducing variability in NOK satisfaction having been met. High uptake of interventions suggests a causal role of these interventions in improving NOK satisfaction with communication. The transition of NNW towards standby significantly shortened the timeline for change and limited assessment of the sustainability of interventions.

Differentiating between the impacts of trialled interventions was difficult due to the quick succession of introduction. We postulate that an exaggerated uptake of interventions could have occurred due to the concentrated promotion of NOK communication around this time. Without ongoing reminders of standards, adherence may have reduced over time.

This QIP builds upon previous work trialling structured NOK communication, and suggests that implementing this in a non-visiting field hospital setting, can mitigate communication barriers and enhance NOK experience. Our expectation was that standardising the frequency of NOK communication would improve NOK satisfaction. However, the importance of effectively conveying new standards to stake-holders (in this scenario the medical team) was illuminated. The use of technology and humour were successful in engaging staff with interventions. Whilst interventions would be transferable to other clinical settings, specific standards would require adaptation according to patient needs and resource availability.

There is scope for future work to improve quality of communication with NOK. Interventions such as MDT communication sheets could target reported inconsistencies in communication.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

References

[1] | Pincock S. Poor communication lies at heart of NHS complaints, says ombudsman. BMJ. (2004) ;328: :7430. |

[2] | Bélanger L, Bussiéres S, Rainville F, Coulombe M, Desmartis M. Hospital visiting policies impacts on patients, families and staff: A review of the literature to inform decision making. Journal of Hospital Administration. (2017) ;6: (6):51. |

[3] | Fitzpatrick D, Doyle K, Finn G, Gallagher P. The collateral history: An overlooked core clinical skill. European Geriatric Medicine. (2020) ;11: (6):1003–7. |

[4] | Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: A review of key issues for hospitalists. Journal of Hospital Medicine. (2007) ;2: (5):314–23. |

[5] | Caswell G, Pollock K, Harwood R, Porock D. Communication between family carers and health professionals about end-of-life care for older people in the acute hospital setting: A qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care. (2015) ;14: (1). |

[6] | Daly B, Douglas S, O’Toole E, Gordon N, Hejal R Effectiveness trial of an intensive communication structure for families of long-stay ICU patients. Chest. (2010) ;138: (6):1340–8. |

[7] | Khan A, Spector N, Baird J, Ashland M, Starmer A Patient safety after implementation of a coproduced family centered communication programme: Multicenter before and after intervention study. BMJ..k4764. |

[8] | Stanbridge R. Including families and carers: An evaluation of the family liaison service on inpatient psychiatric wards in Somerset, UK. Mental Health Review Journal. (2012) ;17: (2):70–80. |

[9] | Houchens N, Tipirneni R. Compassionate communication amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Hospital Medicine. (2020) ;15: (7):437–9. |

[10] | Gabbie S, Man K, Morgan G, Maity S. The development of a family liaison team to improve communication between intensive care unit patients and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Education & Practice Edition. (2021) ;106: (6):367–9. |