The use of digital solutions in alleviating the burden of IAPT’s waiting times

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Previous reports have shown that there are long waiting times to commence therapy in the community-based mental health programme, IAPT (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies).

OBJECTIVE:

This study aimed to explore both causes and potential solutions to alleviate the burden of these waits.

METHODS:

A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) and Semi-Structured Interviews (SSIs) were conducted to identify causes and effects of these waits. Consequently, meaningful recommendations were made and tested with the aim of improving IAPT’s waiting times.

RESULTS:

SLR and SSIs revealed high ‘Did Not Attend’ (DNA) rates and a lack of support between initial appointments as being both a cause and effect of long waits. The identified issues were tackled with the development of an app design. Expert interviews and a mass survey fuelled the iterative process leading to a final prototype. Notable features included: therapist profile page, smart appointment reminders and patient timeline. Positive feedback was received from university students and ICS Digital, with scope to trial the app within Manchester CCG.

CONCLUSIONS:

In the long run, the app aims to indirectly shorten waiting times by addressing treatment expectations and serving as an IAPT companion along the patient journey, thus reducing anxiety and consequently DNAs.

1.Background

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) is a primary care mental health service, which provides evidence-based talking therapies for patients with depression and/or anxiety. Patients can either be referred to IAPT from their GP or self-refer directly, from which they enter the waiting list for assessment and treatment. Although the waiting times reported by IAPT show that 89.4% wait less than 6 weeks for their first appointment and 99% wait less than 18 weeks [1], these figures do not consider the wait between the 1st and 2nd appointment. This is especially relevant as the first appointment is often an introductory assessment, and the second appointment is when the therapy commences. A report has shown that waiting times for the second appointment was more than double the waiting times for the introductory assessment in two-thirds of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) [2]. The ‘We need to talk’ coalition reports that one in ten people have been waiting over a year to receive treatment, and these long waits for psychological therapies may be exacerbating patients’ mental health problems [3]. Unfortunately, there is limited support available for such patients during their wait. Although the mental health application (app) market is saturated, an app which increases engagement and provides support for patients during their wait may be beneficial.

2.Method

A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was performed to assess the causes and effects of long waiting times in IAPT. Following this, qualitative data collection in the form of Semi-Structured Interviews (SSIs) were carried out with 8 Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (PWPs) from 8 IAPT sites across London. These interviews aimed to gain further insight into the source and impact of the long waiting times. Thematic analysis was carried out on the SSI transcripts, using latent and semantic approaches to establish the main concepts within the data. Due to the flexible nature of thematic analysis, Clarke and Braun’s six-step model enabled a structured approach to generating themes [4].

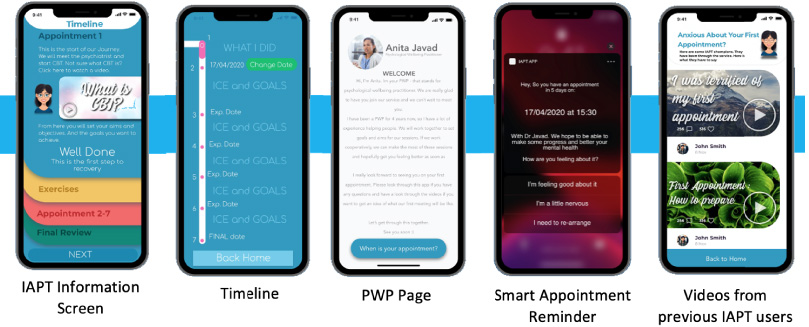

Consequently, meaningful recommendations were made and tested with the aim of improving IAPT’s waiting times. The primary intervention was a digital app, designed to tackle both causes and effects of the long waits. The initial prototype was outlined and explored iteratively in 7 psychiatry expert interviews and a survey of 102 university students who were recruited through a targeted social media advertising drive. The survey was carried out in 3 phases using the design thinking model [5]. After surveying each subset of 34 students, their feedback was reviewed, and the app was fine-tuned accordingly before gathering further feedback from the next subset. These improvement cycles were key for highlighting which features to focus on for optimum patient support. This collaborative, patient-focused process ultimately facilitated the development of the final prototype (Fig. 1). Moreover, an important consideration was the immense financial pressure on the NHS, with limited resources for the increasing demands of mental health [6]. Hence, the app’s features were also aligned to a goal of financial sustainability, in which the upfront costs would be recovered by increasing engagement and reducing “Did Not Attend” (DNAs) within IAPT.

3.Results

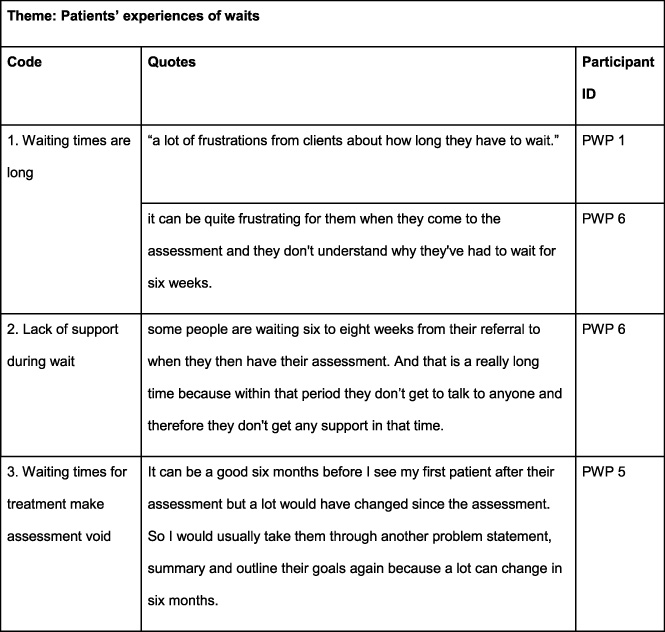

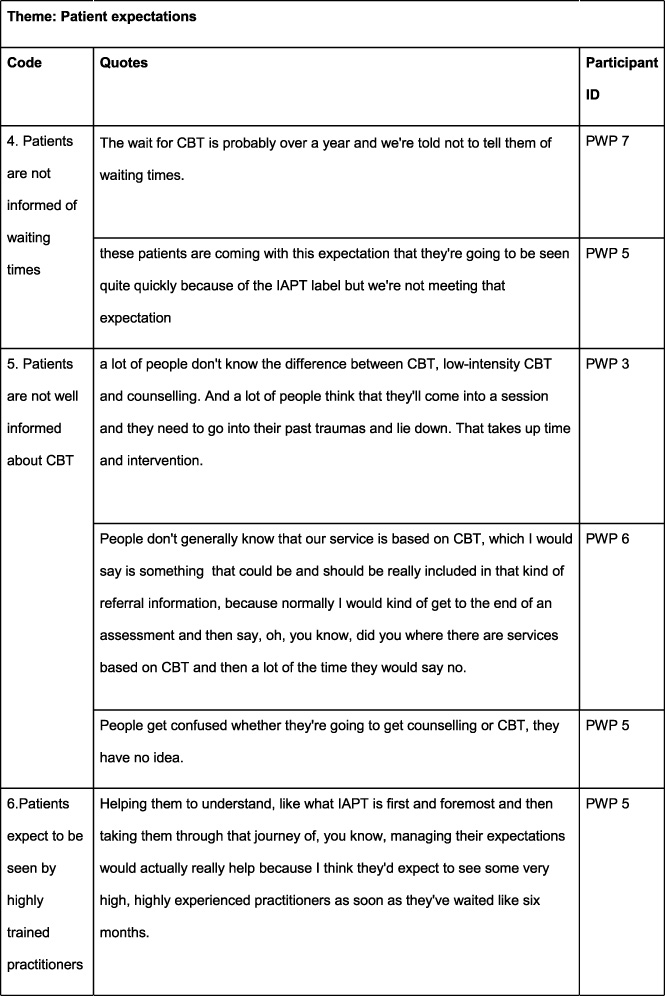

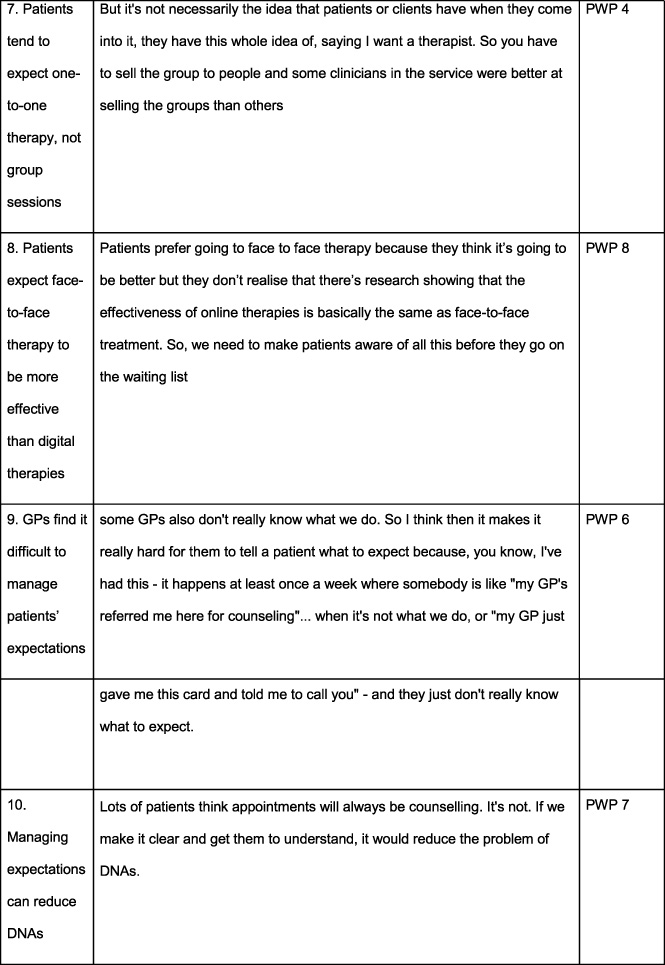

The SLR and SSIs highlighted two main issues; high DNAs are both a cause and effect of long waiting times, and patients are not well-supported whilst waiting for their appointments (Fig. 2). The app was designed to tackle these issues, functioning as a therapy adjunct that accompanies the patient throughout their IAPT journey.

Fig. 1.

Selected screenshots of the application.

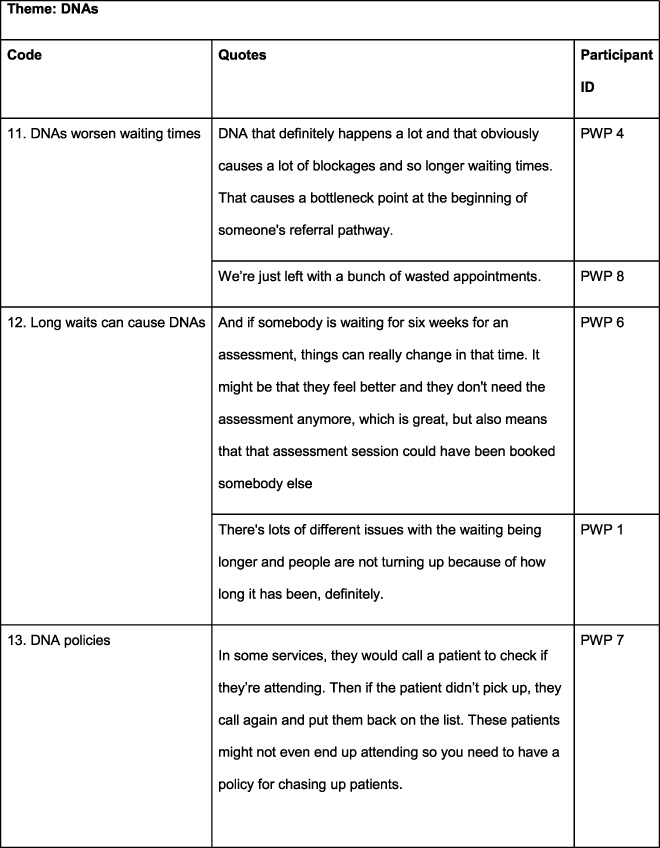

Fig. 2.

Excerpt from full thematic analysis of PWP interviews focussing on core themes of patients’ experiences of waits, patient expectations and DNAs.

Fig. 2 (Continued).

(Continued).

Fig. 2 (Continued).

(Continued).

Fig. 2 (Continued).

(Continued).

3.1.Addressing DNA rates

Three main causes of DNAs were also identified:

Patients referred to IAPT have unrealistic expectations of the treatment they will receive due to poorly established understanding.

Patients often feel apprehensive leading up to their first appointment.

Patients may simply forget to attend appointments.

Firstly, interviews revealed that many patients fall victim to misconceptions about IAPT and expect counselling over cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), leading to some dropping out of treatment. To address this, the initial set-up of the app includes a comprehensive explanation of CBT using videos and text. Having been educated on what CBT entails, if patients do not want CBT, the app enables them to explore other treatment modalities or cancel the appointment. Once the app has been set up, patients are shown a series of screens outlining the timeline of their IAPT journey. Informing patients will reduce the chances of disappointment from unmet expectations and subsequent DNAs.

Another reason for DNAs was that patients can feel too nervous about their appointment and not attend. This was reiterated in surveys conducted on students for feedback on the app, in which 75.2% of respondents cited that they would feel nervous before their appointment. Therefore, the app gauges how patients feel 2, 5 and 7 days before the appointment, helping them feel more mentally prepared. For example, if the patient was to feel nervous, then the app could put them at ease by suggesting videos from previous IAPT users. The feature was well-received, with 85.1% of survey respondents citing that the videos would help them attend their appointment if they felt nervous.

Lastly, patients may forget to attend their appointments. Although IAPT offers a simple text reminder, the app uses staggered and engaging reminders as research shows that this yields better attendance [7].

3.2.Provision of support whilst waiting for appointments

The SSIs also revealed that patients can feel forgotten whilst waiting, making them more likely to disengage [8]. Thus, the app has a timeline feature to track ideas, concerns, and expectations. It also fulfils the need for transparency by showing patients where they are on their journey and what will happen at each stage, which 77.2% of survey respondents found to be useful.

Interviews with therapists revealed that patients often have a fear of the unknown. Additionally, qualitative feedback within the student surveys suggested that there was a need for a positively framed welcome message from the PWPs. This gave rise to the design of a PWP introduction screen, to help patients put a face to their PWP and reassure them of their PWP’s expertise. Thus, this was incorporated into the app, with the aim of helping patients overcome motivational challenges and encourage attendance [9]. Furthermore, it allows for some PWP-patient interaction prior to the appointment which has been shown to increase attendance [8]. Overall, survey results were promising, with 79.2% of respondents citing that the PWP profile would make their first appointment easier to attend. Thus, patients may feel more motivated to attend their appointment having overcome this initial barrier.

Overall, surveying 102 students revealed that 85.3% would find the app useful whilst waiting. This is substantial, considering one in five students suffer from a mental health condition in the UK [10]. Due to COVID-19, active IAPT users could not be recruited for feedback on the app, limiting the representativeness of the results. For this quality improvement project, convenience sampling of university students allowed access to a sample of potential IAPT users for preliminary user feedback. This provided a foundation for the first phase of iterations of the prototype prior to receiving further user feedback from active IAPT users in the future. Another limitation is currently the app is appropriate for English-speaking people but to increase inclusion, we envisage in making the app available to read in different languages.

4.Conclusion

Overall, the app’s therapist profile page, smart appointment reminders and IAPT timeline were best received. Given the gap in the market for an app that increases patient engagement and patients’ understanding of IAPT, future scope is promising with ICS Digital expressing interest to partner on the development and Manchester CCG keen to trial the app, providing an opportunity for direct engagement with the service users. In the long run, the app’s main aim is to shorten waiting times through reducing DNAs, but in the meantime, feedback from students and experts instils confidence that it can serve as a reliable IAPT companion, making these waits a little more bearable.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

References

[1] | NHS Digital. Psychological Therapies, Annual report on the use of IAPT services 2018–19. [Online] 2019 [Accessed: 25th May 2020]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/psychological-therapies-annual-reports-on-the-use-of-iapt-services/annual-report-2018-19. |

[2] | Baker C Mental health statistics for England: prevalence,services and funding. 2020. |

[3] | Mind. We still need to talk. [Online] 2013. Available from: https://www.mind.org.uk/media-a/4248/we-still-need-to-talk_report.pdf. |

[4] | Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. (2006) . doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. |

[5] | Altman M, Huang TTK, Breland JY. Design Thinking in Health Care. Preventing Chronic Disease. (2018) ;15: :180128. doi:10.5888/pcd15.180128. |

[6] | KingsFund. Mental health funding squeeze has lengthened waiting times, say NHS finance leads. [Online] KingsFund. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/press/press-releases/mental-health-funding-squeeze-has-lengthened-waiting-times-say-nhs-finance. |

[7] | Junod Perron N, Dominicé Dao M, Kossovsky MP, Miserez V, Chuard C, Calmy A Reduction of missed appointments at an urban primary care clinic: A randomised controlled study. BMC Family Practice. (2010) ;11: (1):79. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-11-79. |

[8] | Marshall D, Quinn C, Child S, Shenton D, Pooler J, Forber S What IAPT services can learn from those who do not attend. Journal of Mental Health. (2016) ;25: (5):410–15. doi:10.3109/09638237.2015.1101057. |

[9] | Mavandadi S, Wright E, Klaus J, Oslin D. Message framing and engagement in specialty mental health care: A follow-up analysis. Psychiatric Services. (2018) ;69: (10):1109–1112. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201800056. |

[10] | Pereira S, Reay K, Bottell J, Walker L, Dzikiti C University Student Mental Health Survey 2018. 2019. |