Improving the documentation of chaperones during intimate examinations in a surgical admissions unit: A four-stage approach

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The General Medical Council (GMC) states that all intimate examinations should have a chaperone offered. Documentation of chaperone identity, or patient’s refusal, is essential.

OBJECTIVE:

This project aimed to improve documentation of chaperones during intimate examination of patients based in a Surgical Admissions Unit (SAU) within a large tertiary hospital in the Southwest of the UK.

METHODS:

A Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle structure was used. Initial data collection and planning occurred in December 2019. Intervention implementation and analysis occurred from January 2020 to March 2021. Intervention 1 involved presenting results at a clinical governance meeting. Intervention 2 was information posters in the SAU and intervention 3 involved training sessions for nursing staff. Intervention 4 was editing the surgical clerking proforma.

RESULTS:

Prior to interventions, chaperone identity or patient’s refusal was correctly documented only 9.7% (N = 7 out of 72) of the time. Intervention 1 increased this to 34.6%. Following interventions 3 and 4, correct documentation was 25.0% and 28.6% respectively. After intervention 4 correct documentation was at 59.1%.

CONCLUSIONS:

Initial documentation of chaperones was poor. Interventions 1 to 3 were successful in educating clinicians how to document accurately, but engaging individuals in person was more successful than passive education through posters. Changing the proforma structure was the most successful intervention. This suggests a visual reminder for clinicians at the point of contact with the patient is the most effective way to encourage correct documentation of chaperones, improving patient care and clinical practice.

1.Background

A medical chaperone is an impartial observer of a consultation. They act as an advocate for the patient and provide support where needed. Chaperones are also important medicolegally for the clinician. Therefore, documentation of the chaperone, or patient’s refusal, is essential.

The General Medical Council guidance states that all intimate examinations should have a chaperone offered, advising “this is likely to include examinations of breasts, genitalia and rectum, but could also include any examination where it is necessary to touch or even be close to the patient [1]”. The NHS Clinical Governance Support Team has published similar guidance regarding chaperone use aimed at medical, nursing and allied healthcare professionals [2].

Despite such clear guidance, evidence suggests that this is often not followed [3–5]. Recent studies in other organisations suggest that interventions, such as posters, stamps or stickers in notes, can help improve this [4,6].

The aim of this project was to establish adequacy of current documentation within a large surgical admissions unit. Four interventions were then implemented, to improve adherence to the official guidance regarding chaperones, enhancing patient safety and clinical practice.

2.Methods

This single-centre quality improvement project was based in the SAU at the North Bristol NHS Trust in the Southwest of the UK. It looked at documentation of chaperones during clerking of surgical patients. An initial audit (n = 72) was performed in December 2019 prior to interventions. Following a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle structure, re-audits (n = 21–28) were performed after each intervention between March 2020 and April 2021.

Following suggestions from existing literature [3,6], a change to the clerking proformas was a planned intervention from the beginning of the project. Within the time required to execute this, other interventions were implemented, influenced by each PDSA cycle.

Intervention 1 was presenting initial audit results at a clinical governance meeting. This increased awareness but only reached the doctors and senior nursing staff who attended the meeting. The intervention did not provide longevity or ongoing reminders.

Intervention 2 aimed to maintain project awareness by putting up information posters in the SAU. These acted as visual reminders but could often be overlooked by busy staff.

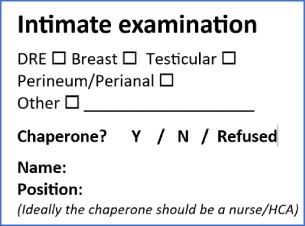

To further educate staff who often act as chaperones, intervention 3 involved training sessions for nurses and healthcare assistants. This involved them as stakeholders, creating a multi-disciplinary approach to improving documentation. The allocation of two nurses as ‘chaperone champions’ ensured ongoing teaching and sustainable change. Intervention 4 was an addition of a chaperone section within the surgical clerking proforma (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Clerking proforma edit for chaperone documentation.

‘Correct documentation’ was defined as either refusal of chaperone or written chaperone identity (full name and position). This was based on General Medical Council (GMC) guidance that the gold standard for chaperone documentation must include either of these criteria [1]. ‘Attempted documentation’ was any other evidence of chaperone documentation, such as incomplete or missing name. This has been coded in results as ‘other’. Data was collected over several weeks for each PDSA cycle to ensure adequate representation of staff.

3.Results

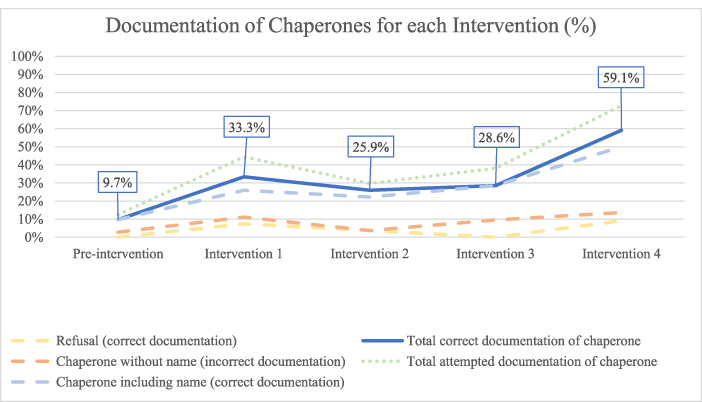

An initial audit in December 2019 examined clerking proformas of 72 patients (36 male (M): 36 female (F)). Chaperones were correctly documented 9.7% of the time (n = 7). Overall attempted documented was 12.5% (n = 9).

Following intervention 1, a review of 27 patients (13M: 14F) demonstrated correct documentation of chaperones had increased to 33.3%. Overall attempted documentation was 44.5%.

After intervention 2, a review of 27 patients (15M: 12F) showed correct documentation and attempted documentation were 25.7% (n = 7) and 29.6% (n = 8) respectively - greater than the initial audit but less than intervention 1.

21 patients (9M: 12F) were audited following implementation of intervention 3. Chaperones were correctly documented in 28.6%. Overall attempted documentation was 38.1%.

After intervention 4, 22 patients were audited (13M: 9F). Correct and attempted documentation were 59.1% (n = 13) and 72.7% (n = 16) respectively.

A full breakdown of results from the initial audit and subsequent PDSA cycles are detailed in Table 1. A run chart can be seen in Fig. 2.

Table 1

Documentation observed for initial audit and interventions 1, 2, 3 and 4

| Documentation categories | Initial audit (n = 72) | Intervention 1 – clinical meeting (n = 27) | Intervention 2 – information posters (n = 27) | Intervention 3 – MDT education (n = 21) | Intervention 4 – surgical proforma (n = 22) |

| 1. Chaperone identification | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 11 |

| 2. Refusals | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 3. ‘Other’ | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Correct documentation (category 1 + 2) | 9.7% N = 7 | 33.3%N = 9 | 25.7%N = 7 | 28.6%N = 6 | 59.1%N = 13 |

| Attempted documentation (category 1 + 2 + 3) | 12.5%N = 9 | 44.5%N = 12 | 29.6%N = 8 | 38.1%N = 8 | 72.7%N = 16 |

Fig. 2.

Run chart demonstrating percentage documentation at each PDSA cycle stage.

This project involved the whole multi-disciplinary team (MDT), utilising different ways to deliver information; posters, presentations and face-to-face education. The poster alone did not improve compliance, supporting existing evidence that active learning is more efficacious than passive information provision [7].

Interactive teaching sessions (intervention 3) empowered nursing staff and healthcare assistants as stakeholders, demonstrated by improved documentation.

As the project was undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic, there were challenges in making change at pace. Furthermore, social distancing rules prevented large group gatherings; ad-hoc small group sessions had to be used instead. Whilst this allowed more discussion, only 25% of the SAU staff received direct teaching from project leads. Recruiting “chaperone champions” aimed to alleviate this and increase the sustainability of the project by ensuring ongoing educational supervision.

The largest improvement was seen once the clerking proforma was altered. This has been mirrored in other quality improvement projects using visual reminders [3,6].

Attempted documentation also improved from 12.5% to 72.7%. This demonstrates an increased awareness and provides evidence of increasing use of chaperones. It may, however, indicate knowledge gaps among staff regarding comprehensive documentation; an important next step for the project.

Despite no explicit financial savings seen at the time of data collection, we believe that there will be increased efficiency in identification of chaperones retrospectively. The change in practice may reduce complaints and better facilitate response to complaints and medicolegal action [8]. However, the main improvement is better patient support during intimate examinations leading to improved patient experience and protection for health professionals.

4.Conclusions

Continued quality improvement increased accurate documentation of chaperones from 9.7% to 59.1%. The interventions introduced through the project worked individually and cumulatively towards a significant improvement in documentation and patient experience.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

References

[1] | General Medical Council. Intimate examinations and chaperones [Internet]. Gmc-uk.org. 2013 [cited 15/04/2021]. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/intimate-examinations-and-chaperones/intimate-examinations-and-chaperones. |

[2] | Gerada C, Warner L. Guidance on the role and effective use of chaperones in primary and community care settings. London: NHS Clinical Governance Support Team; (2005) . |

[3] | Hussain Y, Lockwood S, Hussain A. Improving documentation of chaperones in intimate examinations: Perfecting the proforma. International Journal of Surgery. (2016) ;36: :S88–9. |

[4] | Sharma N, Kathleen Mary Walsh A, Rajagopalan S. An audit on the use of chaperones during intimate patient examinations. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. (2016) ;7: :58–60. |

[5] | Allberry C, Fernando I. An audit of chaperone use for intimate examinations in an integrated sexual health clinic. International Journal of STD & AIDS. (2012) ;23: (8):593–4, [cited 15 April 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22930299/. |

[6] | Rose K, Eshelby S, Thiruchelvam P, Khoo A, Hogben K. The importance of a medical chaperone: A quality improvement study exploring the use of a note stamp in a tertiary breast surgery unit. BMJ Open. (2015) ;5: (7):e007319. |

[7] | Salemi Michael K. An illustrated case for active learning. Southern Economic Journal. (2002) ;68: (3):721–31. doi:10.2307/1061730. |

[8] | MDU. Best Practice in Use of Chaperones [Internet]. MDU Journal April 2014 – The MDU. 2014. [Cited 25/4/2021]. Available from: https://www.themdu.com/guidance-and-advice/journals/mdu-journal-april-2014/best-practice-in-the-use-of-chaperones. |