Documentation of Just in Case (JiC) medication for end of life patients in care homes looked after by a general practice

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

This project was undertaken to improve the documentation of Just in Case (JiC) medication in a general practice. The outcome of a Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis highlighted this as an area where awareness within the practice could be improved.

OBJECTIVE:

A Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) approach was taken to the project and involved collaborative working and data collection from the general practice and relevant care homes.

METHOD:

JiC medications are used to promptly manage symptoms experienced at the end of a patient’s life and are part of the Gold Standard Framework (2006).

RESULTS:

Of the patients registered at the practice with JiC medication, 37.5% were incorrectly documented. This included errors/ inaccuracy with the clinical coding, or the medication. Three patients on practice generated searches had no JiC medication in the care homes, and 4 patients had JiC boxes in the care home that was not identified by the search.

CONCLUSION:

This evaluation has identified documentation errors and discrepancies between practice and community records of JiC medication. A newly generated practice specific flowchart was created, with an aim of reducing the discrepancies. A guide of how to carry out a QI project like this was created for the RCGP and can be found on their website. A seminar at Bristol, North Somerset, and South Gloucestershire (BNSSG) CCG to present this project took place in 2021.

1.Background

Just in Case (JiC) medications are used to manage end of life care in the community and enable prompt responses to escalations in symptoms [1]. The boxes contain medication to help control common symptoms experienced at the end of life: anxiety, pain, nausea, and respiratory secretions [2] Commonly prescribed are Midazolam, Morphine, Metoclopramide and Hyoscine. The medications are indicated when the patient is entering the last two weeks of life [1]. Having this medication in a care home, or the patient’s home (not reviewed in this evaluation), means that medication is available as soon as it is needed [3] JiC medications support proactive symptom control in palliative patients and their use is part of the Gold Standard Framework (2006) [4].

Research into JiC medication and the use in the community is limited [5] and there is great complexity in this care pathway due to the diversity in environments of prescribing and use [2]. There is also a wide variety of professionals involved [2]. Good communication between all the members of the team, across organisations, is required [2]. The aims of this project are also in line with standards four and six of the Marie Curie Daffodil Care Standards [6] and the Local Enhanced Services 19/20 [7]. For example, it is required that anticipatory (JiC) medications be reviewed regularly, and this is documented in the care plan [7]. Also, a practice should be able to generate a list of care home patients who have been prescribed JiC medications [7].

2.Methods

The project was registered with the BNSSG CCG evidence and evaluation team and a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) approach was used. The relevant care homes were contacted before the start of the evaluation to get consent for their involvement. Gold Standard Framework, Examples of good practice resource guide [4] was used as a reference point used.

2.1.Plan

A SWOT analysis, including the GP, practice pharmacist and care home perspectives, was undertaken. The main issues raised were that the practice has never audited JIC medications, so there is little awareness of the process around JiC medications within the practice or community care. Also, there were concerns about potential misuse of (controlled) medications where there is no check of usage or disposal.

Alongside a practice generated search of the coding and prescribing, care homes were visited to assess whether the practice records currently match the care home records. This project was undertaken by a medical student and had no cost implications, there was no direct patient contact and no ethical approval was required.

2.2.Do

Project 1: A search generating the number of people who have JiC medications prescribed as acute medication, and the number of people with the JiC code documented within the notes.

Project 2: The care homes of all the patients who appeared in project 1 report were visited and a manual comparison was done between the practice and care home documentation.

3.Results

3.1.Study

3.1.1.Project 1

62.5% of currently active patients had the correct documentation for the JiC medication. Of the patients who had medication prescribed, but no code for JiC medication entered, all had comments documented in free text. While this means that the information is available, it is not auditable. Of the five patients who had the code documented, but the medication was not picked up by the search criteria, one patient had a free text entry stating that it had been cancelled, one had an attached community prescription chart, and the other three had no medication recorded despite the code having been documented.

3.1.2.Project 2

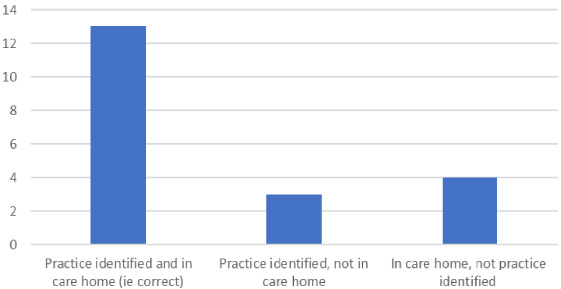

There were discrepancies between the search results and care home records (see Fig. 1). Care homes did not have JiC medication for patients identified in the search, and had JiC medication for patients not identified by the search.

Fig. 1.

Project 2 results.

The reasons for this include: the medication being cancelled and the practice coding not reflecting this, and the pharmacy holding the medication rather than the care home. For patients with medication at the care home and identified by the search, reasons included: a different combination of medication not identified in the search, and the medication being started by the Out of Hours team. It was not possible to identify the reason for every discrepancy. In addition to these figures, two patients were excluded. This was because there was an exclusion criterion in the searches so that only medication/codes dated within 12 months of the search date were included. This result highlighted that some patients have medication, which is meant for short term use, for long time periods and demonstrates the need for more robust review processes.

3.2.Act

The recommendations put forward were to use a newly created practice specific flowchart and review proforma, to provide training on the palliative care template and encourage use of the JiC code within the template. Thus, enabling a more auditable process and helping to achieve LES 19/20 targets [7]. The review proforma contains additional questions that will facilitate more nuanced audits regarding prescribing appropriateness, quantifying waste, and monitoring controlled drugs in future cycles of the QI project. All of the mentioned recommendations could be implemented by discussing the findings and recommendations at the practice palliative care meeting.

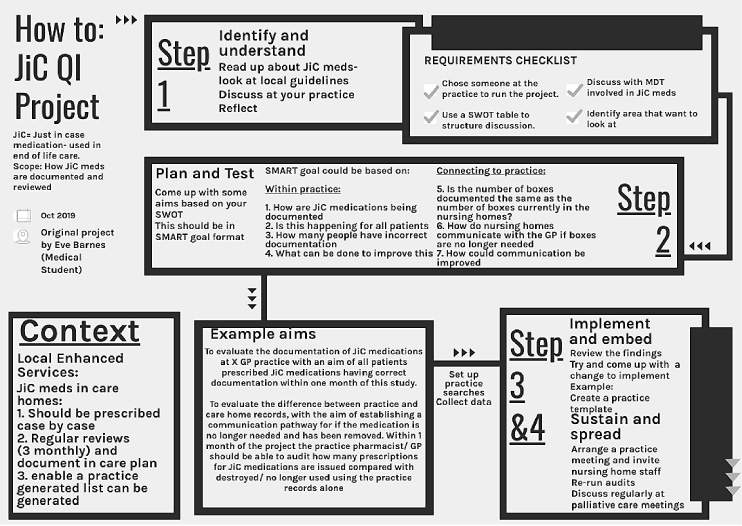

Another outcome of the project was the creation of a flowchart guide that can be used by GP practices to initiate similar projects (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flowchart created for RCGP Marie Curie Daffodil Standards.

4.Discussion

Being undertaken by a medical student could be a limitation of this project because of being a short placement, perhaps limiting the possibility of future cycles of the QI PDSA process. Visiting the care homes was a relatively time intensive process, which may also act as a barrier to continuing with future cycles. The results for project 2 may in fact be an underestimation of the true value, because only care homes of patients with JiC medication identified by project 1 were visited.

The strengths of this project are that it has had practice, regional and national reach. The lack of research in the area [5], the drive for more auditable JiC processes, and desired organisational shifts towards more collaborative working between health and care systems, it is clear that this project is evidence that practical, system improvement work is required, and QI projects are an ideal way of achieving this. The wider outcomes of this project have been the guide created is available to all GPs via the Marie Curie Daffodil Care Standards [8] website and was signposted to on the national newsletter to GPs. Finally, a presentation to the BNSSG CCG is planned for 2021, having been delayed due to COVID-19.

5.Conclusion

This evaluation shows that the practice documentation of JiC medication is inaccurate. The main finding being that 37.5% of JiC medications were incorrectly documented. There are also discrepancies between practice documented JiC boxes and the number of boxes in the care homes. Practice level improvements could be seen by implementation of the recommendations of this report. The wider reach of this projects includes through the Daffodil Care Standards and the local CCG.

Conflict of interest

Role funded by Marie Curie and hosted by RCGP.

References

[1] | Wowchuk SM, Wilson EA, Embleton L, Garcia M, Harlos M, Chochinov HM. The palliative medication kit: An effective way of extending care in the home for patients nearing death. Journal of Palliative Medicine. (2009) ;12: (9):797–803. |

[2] | Faull C, Windridge K, Ockleford E, Hudson M. Anticipatory prescribing in terminal care at home: What challenges do community health professionals encounter? BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. (2013) ;3: (1):91–7. |

[3] | Wilson E, Morbey H, Brown J, Payne S, Seale C, Seymour J. Administering anticipatory medications in end-of-life care: A qualitative study of nursing practice in the community and in nursing homes. Palliative Medicine. (2015) ;29: (1):60–70. |

[4] | GSF [internet]. Examples of good practice resource guide. 2006. Just in case boxes. Available from: http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/Library%2C%20Tools. Accessed 16.7.2019. |

[5] | Thomas K. Out-of-hours palliative care in the community. Continuing care for the dying at home Macmillan Cancer Relief. London, (2001) . |

[6] | Royal College of General Practitioners. Daffodil Standards [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/resources/a-to-z-clinical-resources/daffodil-standards.aspx. Accessed on 26.4.2021. |

[7] | Bristol, North Somerset, South Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group. Local Enhanced Services (LES) Review Update [internet]. 2019. Available from: https://bnssgccg-media.ams3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/attachments/primary_care_commissioning_committee_paper_29january2019_item7.pdf. Accessed on 17.7.2019. |

[8] | Barnes E , How to: JiC QI Project [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/CIRC/Daffodil-Standards/Useful-documents/JIC-QIP-how-to.ashx?la=en. Accessed 26.4.2021. |