Support factors contributing to successful start-up businesses by young entrepreneurs in South Africa

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Unemployment and restricted work opportunities for youth are enduring social challenges that affect health, well-being, and quality of life, especially in low- to middle-income countries. When considering the advantages associated with work as a determinant of health, unemployment is understood to contribute to occupational injustice. However, self-employment, hailed the solution to youth unemployment, is often necessity-driven, precarious in nature and restricted by the low success rate of business start-ups.

OBJECTIVE:

Research was undertaken to explore factors perceived to contribute to the success of start-up businesses in an informal settlement in the Western Cape of South Africa. The importance of support in the success of business start-ups will be the focus of this article.

METHODS:

A collective case study, using narrative interviewing and - analysis, was undertaken in South Africa. Two narrative interviews were conducted with each of the five participants who were youth entrepreneurs and founders of start-up businesses. Data analysis comprised the use of narrative analysis and paradigmatic type narrative analysis.

RESULTS:

Three themes captured factors deemed to have contributed to the success of start-up businesses. The vital role of support systems and networks in business success was demonstrated.

CONCLUSIONS:

Support systems included family, friends, role models, mentors, team members and business partners. Identification, utilization, and ongoing development of support structures available in the social networks of young entrepreneurs were perceived to have contributed to the success of start-ups.

1Introduction

Youth unemployment is a serious and enduring problem recognized by the International Labor Organization (ILO) as an international crisis requiring a multi-pronged approach that includes measures to support youth entrepreneurship [1]. However, progress has been slow in meeting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 8, pertaining to inclusive economic growth and decent work. One of the targets, to “substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training” by 2020 has remained a significant problem [2]. Support for youth entrepreneurship is one of the guiding principles adopted by the ILO to address youth unemployment. Youth entrepreneurship was recognized as a pathway to decent work [1].

Negative factors associated with unemployment include ill-health, poverty and restricted access to social determinants of health [2]. When unemployment affects young people, the associated problems are prolonged and the impact intensified [3]. In developing countries, the pace of poverty reduction has been too slow to keep up with a growing workforce [4]. While wages earned through work provides access to much needed commodities and might offer an escape from poverty, this is not the case in countries where the legal minimum wage is below the basic cost-of-living, leaving a large proportion of employed workers classified as ‘working poor’ [4, 5].

High unemployment reduces work opportunities in the formal economy thus pressing for self-employment, which might only be available in the informal economy. Entrepreneurs who start up new businesses thus face a high possibility of failure and have to overcome significant barriers in order to achieve success or sustainability. Very few business ventures reach a stage at which income generated significantly contributes to subsistence income and when they do, concerns about the quality of work prevail [6]. In fact, Burchell and Coutts question the suitability of self-employment as a favorable form of employment considering the limitations in economic and social benefits [6].

The high start-up business failure rate has been ascribed to the complex and diverse sets of competencies required for the broad range of tasks that have to be mastered in order to succeed [7]. Poverty and limited start-up capital contribute significantly to failure of new businesses, however, fear of failure and the absence of kinship networks have been identified with particular emphasis on young entrepreneurs [6, 8]. Environmental factors found to prevent the success of young entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe (n = 200) include a lack of experience and the openness in the job market [9].

In South Africa, Botman proposed entrepreneurship as a strategy with which to achieve economic justice and national unity in order to bridge the divide between rich and poor, black and white, underdeveloped and developed [10]. Botman called for systemic entrepreneurship, a concept further elaborated by Sautet [11] who explained that it “involves complex impersonal networks through multiple linkages among firms” (p.393) and that “it is not about the size of entrepreneurial opportunities per se, but rather about the scope of the opportunities exploited” (p.393). By adoption of a systemic entrepreneurship perspective, the need for linkages and opportunities in contexts within which entrepreneurs operate become clear. We follow Preisendörfer, Bitz and Bezuidenhout [12] in drawing on previous research that extract factors that affect success of business start-ups in three groups “(1) the characteristics of the founder; (2) the attributes of the new business itself, and (3) the conditions characterizing the environment” (p.7).

Factors related to business owners shown to contribute to successful start-ups include personal characteristics, passion, dedication, perseverance, initiative, need for achievement, creativity and innovation. However, proactivity and risk propensity were singled out as featuring most strongly in the literature [12]. The need for an entrepreneurial mindset and the ability to identify the benefits of taking risks were highlighted [13] and demonstrated an increased performance in aspects such as creativity, risk taking, and growth in mindset, which were considered essential factors in business success [14]. Skills in communication and conflict management were linked to success [15] and found to be a “great personal asset which facilitated business expansion” [16] (p.70). Additionally, the manner in which entrepreneurs handled conflict positively influenced social reputation and overall business success [15]. The ability to reflect was shown to assist entrepreneurs with problem-solving [17], dealing with challenges, developing leadership and the creation of new ventures [18].

Marketing skills were identified by business owners in Hong Kong (n = 52) as the most important managerial factor for success in small businesses; assisting them to gain access to new suppliers who were able to provide production materials at lower costs, broaden their target market and create further trading opportunities [16]. The role of previous work experience was emphasized in a quantitative study conducted in South Africa with final year business management students (n = 155). It was found that students with previous work experience had a slightly higher level of entrepreneurial intention than those without [19]. Previous experience seemed to promote the development of skills and competencies required to become an entrepreneur, and therefore may assist in the success of a business [19]. Several studies demonstrated a relationship between level of education and business skills and efficiency [12, 20–26]. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) consistently reported the importance of education; in 2010 individuals who completed secondary education had 11 times greater potential for success than those who did not [27]; in 2022 the level of early stage entrepreneurial activity for graduates exceeded non-graduates in 45 of 49 economies [28]. Entrepreneurial education was found to improve the entrepreneurial spirit and orientation of individuals, thus improving their chances of business success [29].

The attributes of the new business itself require consideration. A study comprising a standardized population survey (n = 310) followed by in-depth qualitative interviews with current and former entrepreneurs operating in a South African township (n = 49), revealed that trade businesses and service providers were more prone to failure than start-up businesses in the manufacturing, handicraft and construction sectors [12]. Therefore, the type of business may influence the success of the business. Furthermore, it was reported that there were limited prospects for growth from a small to a medium sized business in Kenya due to either an oversupply of similar goods in the market place or a low-quality product [30].

Conditions characterizing the business environment that were found to contribute to business success were varied. Multiple forms of capital have been shown as essential for start-ups to succeed, including economic, human, and social capital. Hikido [31] reminded that cultural and symbolic capital are vital forms of support for small ethnic enterprises and argued for the potential of inter-racial social capital [31]. Access to start-up capital, infrastructure and marketing were deemed necessary to start a business [12, 32].

One of the types of social capital that was highlighted in a quasi-experimental study done in Gauteng, was having a role model. Regardless of the age of the business, number of employees or demographics of the entrepreneur, role models were considered important for business success, because business owners could identify with them [31]. Successful entrepreneurs (n = 90) within the tourism sector were found to benefit from local and international networks [12].

Access to financial capital, an obvious requirement for new and existing entrepreneurs, is strongly determined by contextual factors, especially in low-income to upper-middle-income countries. South Africa is one example where access to formal finance was identified as a major challenge for new entrepreneurs [23]. Obtaining financial support, such as business loans, was shown to be more difficult for South African entrepreneurs who were financially disadvantaged; as such, they were less likely to successfully set up and maintain their own businesses [33]. In Zimbabwe, limited finances were associated with secondary challenges, such as affordability of transport costs, high registration fees and operating licenses, which required sufficient start-up capital [9]. Limited finance was stated as one of the reasons why youth in Nigeria were less likely to experience success with start-up businesses [34].

Physical resources, the environment and the location of the business (rural or urban) were found to influence the success of start-up businesses [35]. Physical resources, including buildings, equipment, raw materials and general supplies, are required for small businesses to succeed [35]. Interestingly, a survey (n = 449) across eight provinces in South Africa, found that within urban locations, businesses located close to other shops experienced greater profit and success than those located further away [23].

Government policies have an obvious influence on the overall success of businesses, for example strict tax reinforcement, registration fees and requirements imposed by policies and laws make it challenging for emerging entrepreneurs [22]. Despite the existing National Youth Policy in South Africa, which focuses on alleviating unemployment, many young adults continue to struggle within the labor market, particularly women [36]. An unpredictable and unstable political environment, together with unreliable and insufficient government support, was found to negatively affect the success of businesses [9].

Shava and Rungani reported the impact of culture on entrepreneurs’ behaviors, including their occupational choices. They further highlighted the dominant cultural norm across Africa, that men fulfil career related roles while women that of domestic roles [37]. A survey conducted with SME’s (n = 174) in the Free State Province of South Africa, found that male ownership was overwhelmingly dominant in all types of businesses. Furthermore, it was reported that male ownership specifically dominated in the manufacturing and construction industries, whereas female ownership was the highest in the retailing, hair salon and urban farming industries [38].

O’Halloran, Franworth and Thomacos confirm our own view that unemployment is an occupational issue, despite attracting “surprisingly little attention to date within occupation-focused literature” (p. 298) [39]. Although the role of occupational therapists in facilitating work-related transitions has been well established [40], the focus tends to be on return to work or placement in existing work opportunities. However, in LMICs with high unemployment, obtaining work is not a realistic option for many occupational therapy service users. In such cases occupational therapists require competencies to facilitate work creation initiatives [41–43], including entrepreneurship [44]. The need for a broader range of competencies in facilitating work-related transitions has been identified, for example job seeking skills, training, and counselling to facilitate return to work or acquiring employment. This was deemed important for inclusion in occupational therapy curricula, both at an undergraduate and postgraduate level [45]. In doing this, occupational therapists would be better equipped to make a valuable contribution to the team of role players and sectors, to ensure that the necessary support is provided for entrepreneurs [42].

A collective case study, utilizing narrative interviewing and analysis, was undertaken with the aim to explore factors perceived to contribute to the success of start-up businesses by young business founders in Kayamandi, a suburb comprising of predominantly low-cost housing, on the outskirts of Stellenbosch in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. The study objectives were to elicit narratives in which participants talk about establishing their businesses and to identify factors deemed to have contributed to the participants’ business success. One of the categories that emerged from the research, namely external support, will be presented here.

2Methods

2.1Study design

A collective case study, using narrative interviewing and analysis, was undertaken within an interpretive ontology. The design was chosen for its potential to inductively explore the experience-based insights of a small and underrepresented group.

2.2Study population and sampling

The study population comprised of young entrepreneurs, between 25 and 35, who successfully started their own businesses in the Kayamandi area; for the purpose of this study business start-ups were deemed successful if these yielded sufficient income for (at least) the founder to be self-sustainable in terms of livelihood needs. Purposive, maximum variation, type sampling was used to select five participants; variation was sought in terms of:

1. Type of business or service rendered. Varied factors may influence success, such as the demand for the product or service, competition, or target market.

2. Gender: Men and women may have differing views, roles and opportunities influencing their approach to starting a business that might influence success.

3. Ownership type: Start-up processes and types of ownership may yield different influences shaping business success.

4. Duration: We anticipated that varied factors might shape success over time.

2.3Recruitment

Recruitment commenced with an email to the owners of a start-up business in Kayamandi who had profiles on social media. A meeting followed during which the research was discussed, rapport was established and questions pertaining to the research and researchers were answered. Snowballing [46] was then used to recruit additional participants; criteria for maximum variation were incorporated in the process.

2.4Data collection

Narrative interviews were undertaken to explore decisions, motivations and actions of participants pertaining to the development of their businesses [47]. Two interviews, approximately 90 minutes on average, were conducted with each participant. Interviews commenced by asking participants to share their narrative in terms of what factors contributed to the establishment and success of their businesses. Prompting questions were then used; these included questions about success factors and challenges experienced, financial and social support received, the influence of gender on their business success and availability of resources. Time was allowed for transcription and analysis of the first interview before the second interview was done. The second interview was used to discuss analysis and interpretation of the first interview and to clarify any questions that arose. Interviews were conducted at a central coffee shop in Kayamandi and were audio recorded.

2.5Data analysis

Two forms of narrative analysis, namely narrative analysis and paradigmatic-type narrative analysis were combined [48]. For paradigmatic-type analysis all interviews conducted with participants were transcribed by one of the authors, then analyzed using Weft QDA following a three-phased process: 1) Selecting meaning units, 2) condensing and coding, and 3) creating categories. Meaning units were instances in which participants were narrating factors deemed to have contributed to business success. These were coded and grouped to form categories. Narrative analysis involved the development of a biography for each participant. These were developed to illuminate each participants’ unique, context-informed experience, and to synthesize how the factors collectively contributed to success in establishing his/her start-up business [48]. The two forms of narrative analysis were used in combination to identify success factors perceived by the participants to have contributed to their success. These processes were followed for each participant, thus constituting a within-case analysis. Similarities and differences were then identified between the participants to create a synthesized interpretation; this took the form of a cross-case analysis.

2.6Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Stellenbosch University Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences’ Health Research Ethics Committee (Ref: U18/12/040) which adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments. Participants’ autonomy was protected by obtaining informed consent; after explaining the aim and nature of the study to them. The participants were informed that the research was being conducted in partial fulfilment of a Bachelors in Occupational Therapy qualification. Confidentiality was upheld by using pseudonyms and removing identifiable particulars.

2.7Trustworthiness

Credibility of findings were established with the use of triangulation. Investigator triangulation pertained to the involvement of a minimum of two researchers in data capturing and the participation of all authors in data analysis. Data triangulation pertained to time; each participant was interviewed twice. Credibility was further enhanced by discussing interpretations of narratives with the participants during follow-up interviews as a form of member checking. Peer debriefing involved the first author’s oversight at each stage of the research. Insights and challenges were discussed amongst the researchers and through debriefing with an unbiased and more experienced researcher.

3Results

For this study, a successful business was defined as a business that yields sufficient income to allow the founder to be self-sustainable in terms of livelihood, and/or to employ others.

3.1Participants

Short biographies were developed to capture the factors identified by each of the five participants to have been key to their business success.

Fig. 1

The Coffee Shop.

Two friends, Onele, aged 31, and Mike, aged 34 dreamed big when they started their coffee shop in 2014. Onele, born and raised in Kayamandi, had a background in filming and creative arts. His passion for creative arts and uplifting his community meant him and his wife invested a lot of time into the youth and single mothers of Kayamandi. Mike studied accounting and came from a business background. The two partners were persistent in searching for a venue for their coffee shop; through networking they identified the opportunity to take over an entertainment center, which they ran as a coffee shop during the day. Onele and Mike explicitly set out to create a safe and welcoming environment for all people (local residents and visitors) to “come together and celebrate life”. Mike explained their vision for the coffee shop as follows:

“It can play a role in tackling economic inequality and if it is always from a place of reconciliation and positive change, it can have a massive effect on the separation that we still see in our country.”

Fig. 2

The Hair Salon.

Kuhle, a 33-year-old woman, owned a hair salon which she operated from her home. Her brother gave her money to start the business ten years ago. During her business journey she discovered that she needed training in order to enhance the quality of her service. Three years ago, she found a mentor and obtained a bursary which enabled her to enroll for a formal course in hairdressing at a local college. At the time of the interview Kuhle, a single mother of three, also performed roles of daughter, business owner, student, and mentee. She spent most of her time studying and gaining experience, while working in her mentor’s hair salon. In addition to working and studying, she took care of her children, while also running her own hair salon.

Fig. 3

The Beauty Salon.

Sanele, 26 years old, was the proud owner of the first beauty salon and spa in Kayamandi. Her desire “to make others feel beautiful in their own skin” had been her driving force. Sanele’s journey started with studying tourism in 2012, however she soon dropped out as she fell pregnant, and she did not have a passion to work in that field. In 2015, her mother received her pension money which she gifted to Sanele to use for studying towards her dream. After graduating in 2017, Sanele started working at a spa in order to save money to open her own business. In November 2018 her dream became a reality. Sanele continued to work at the spa for extra income and was saving money for a car, in order to offer her services at client’s homes. Her focus remained on the community, as seen in her statement below:

“I wanted to teach them - sometimes you think you are sick, but you are not... your body is just tired, and you need a massage, but because you don’t have money you can’t afford it, so you end up staying at home doing nothing about it and drinking pills that won’t help cause it’s just your body. So, I started a business because of that, and I made sure that my prices and that... will accommodate everyone from my community”.

Fig. 4

The Distribution Business.

3.1.1Bongani

Bongani, a 29-year-old owner of a distribution business, supplied vegetables to individuals and organizations in Kayamandi and surrounding areas. Bongani displayed an entrepreneurial spirit from primary school when he washed people’s shoes for money. Despite lack of formal business training, he started his own events business after school. He used his networking skills to build the business, as seen in his statement, “I’m a very outspoken person, I am very well-known, without necessarily blowing my own horn . . . I am good at marketing”. Even though the events company was successful, Bongani decided to shift his focus because of the moral impact of the business on his faith. He successfully distributed energy drinks for a while but terminated the business due to conflict with the production company. He then started to supply vegetables, and later focused on supplying potatoes to restaurants. Once again, his business was thriving to such an extent that he expanded to farming his own vegetables, thereby cutting out the middleman. Bongani faced several challenges, such as losing funding, dealing with debt, and splitting with his business partner. Nonetheless, he persevered and overcame challenges by focusing on marketing and networking, thus increasing his clients, and growing his business. Bongani’s focus was now on food security through supplying ‘veggie parcels’ in Kayamandi. His vision is to support local non-profit organizations (NGO’s) as seen in his statement:

“I want to employ people and I wanted to give money back to the NGOs, but not to any project. I want to give specifically back to salaries, that is what I want to pay”.

Fig. 5

The Printing Business.

3.1.2Sipho

Sipho, aged 25, had a diploma in marketing. He took over a small t-shirt printing business in 2014 together with his friend, who studied filming. They started by printing t-shirts for the community of Kayamandi, then their business grew, and they started printing for clients in the Eastern Cape, Johannesburg, and Durban. Additionally, their business expanded from only supplying individuals to supplying schools, businesses, churches, and tourists. By securing funding through various organizations, Sipho and his business partner were able to afford their own machines and increase their stock, rather than relying on suppliers. They printed personalized designs on multiple clothing items, including beanies, caps, tracksuits, and jackets. Sipho has always had a strong work ethic and valued client satisfaction above all. He believed in networking and collaborated with friends, designers, and photographers to market his products. Sipho and his partner were working towards having their own clothing line, which they would print. Their commitment to their community was portrayed in the name of their company “I love my community”.

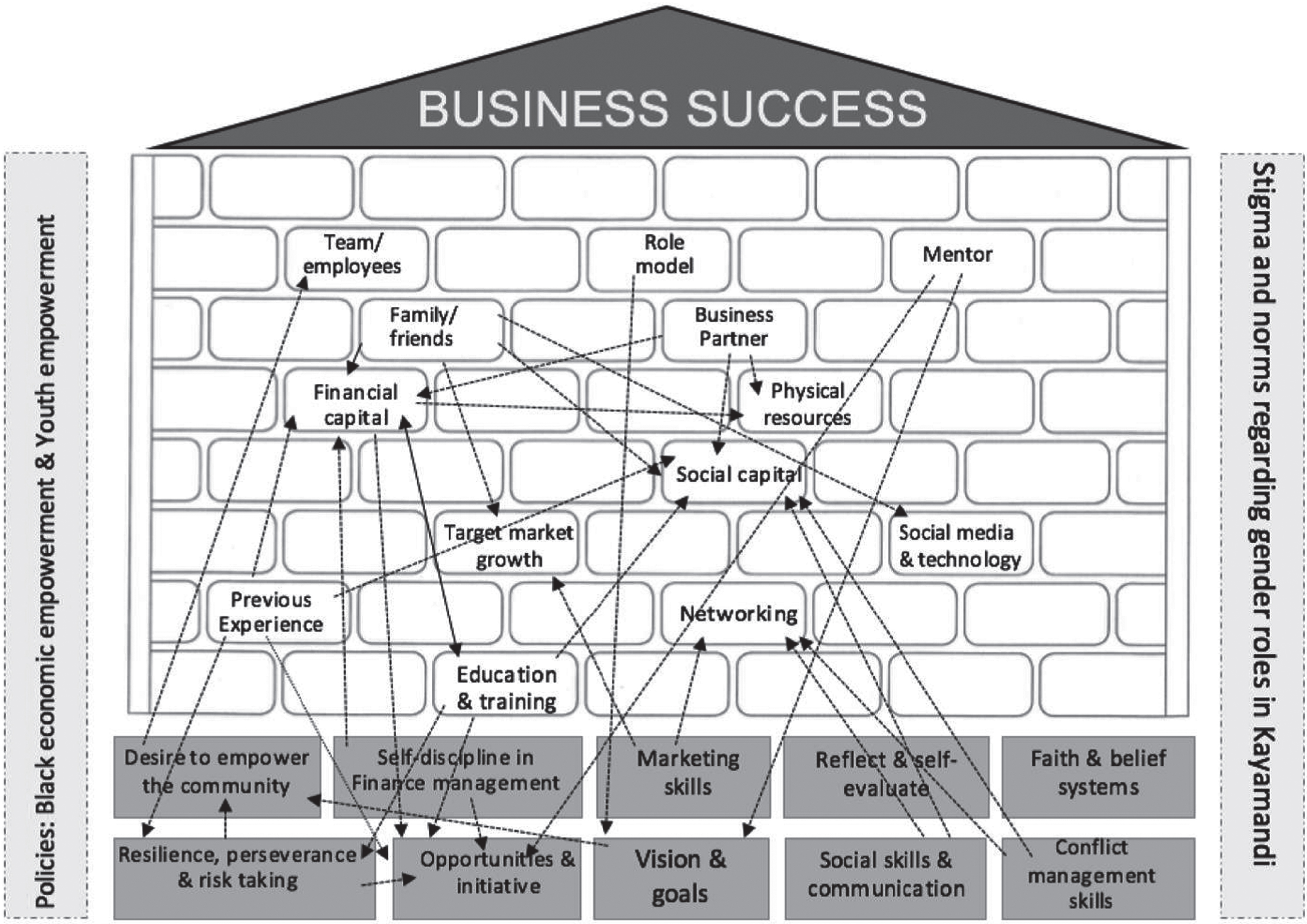

3.2Perceived success factors

Drawing on the value placed on the community by participants in the establishment and maintenance of their businesses, the analogy of constructing a building, shown in Fig. 6, was used to delineate the factors identified as contributing to business success. Three themes, capturing the participants’ views on factors that contributed to achieving business success, are shown.

Fig. 6

Interrelated themes and categories.

The grey foundation blocks at the bottom show the factors internal to business owners and their immediate social environments which were deemed foundational to business success and thus grouped into categories that comprised Theme 1: ‘Building blocks and foundations’. These included personal characteristics and competencies, faith and belief systems, and entrepreneurial competencies. The white construction blocks in the middle represent categories that made up Theme 2: ‘Construction and finishes’. These were forms of capital that were obtained through networking and thus bolstered the availability of financial and physical resources. These factors were operationalized in a process of running a business supported by others; the process was likened to constructing a building together with other people and attending to its finishes. The two adjacent pillars represent Theme 3: ‘Maintenance and alterations’. This theme demonstrated the need for responsiveness to factors that were out of the business owners’ control and required alterations or adaptations to withstand environmental forces. The categories that formed the themes are depicted in Table 1. The category ‘Support’ will be discussed in more detail because of the emphasis placed on this aspect by participants.

Table 1

Three Themes Including Categories of Factors Perceived to Contribute to Achieving Business Success

| Themes | Categories |

| Theme 1: Building blocks and foundations –personal and community capabilities. | Inherent personal characteristics |

| Entrepreneurial competencies | |

| Faith and belief systems | |

| Theme 2: Construction and finishes –forms of capital. | Support |

| Technology and social media | |

| Education and training | |

| Previous entrepreneurial or work experience | |

| Capital acquired or provided | |

| Theme 3: Maintenance and alterations –response to change | Structures |

| Systems | |

| Policies |

All five participants considered the support they received from friends and family as a vital factor in achieving business success. Mike mentioned:

“We were very fortunate to almost have it as a community project on front because we had people buying into the vision, I had a friend who helped us build this coffee shop counter”.

The support they received included physical support, for example being able to borrow a friend’s car or camera, and financial support, which was mostly start-up capital provided by family or friends. Kuhle received financial assistance from her brother:

“He gave me some money to start the business, because I told him I would love to open the business and he really supported me on that, and I started from there”.

Additionally, people provided support in terms of time and labor, such as assistance with administrative tasks, cleaning, and painting or they offered expertise. This was the case with Bongani who reported:

“I called a friend of mine, a chartered accountant, so he does my books, and he helps me to keep accountable”.

Support from family and friends allowed the participants to start their businesses without having to obtain loans or pay for some of the labor required to start up their businesses. As such, the start-up expenses were lowered.

Having a mentor was identified as a significant support factor in three of the participants’ business success. Kuhle reported having a mentor who created opportunities for her to practice and refine her skills under guidance and with feedback. This allowed Kuhle to broaden her client base and the types of hair she was able to work with. Sanele similarly identified her lecturer as a mentor. Bongani explained the benefit of having a mentor as follows:

“Cause he’s walked the road that I want to walk. So, he knows when I meet this hurdle am I supposed to jump or go around it or go under it”.

Mentors provided opportunities, gave advice, and offered guidance while the participants established their businesses, which possibly led to fewer mistakes and therefore contributed to success.

Two of the participants had a business partner and found it beneficial to have someone to keep them accountable and bring a different set of skills and experience to the business, as explained by Mike:

“It’s definitely a complimenting factor, me having strings on business management side and him having strings on a more relational and PR side”.

Sipho agreed:

“There are always challenges but it is always good to have a partner. You don’t have stress alone. So, there’s someone else with whom you . . . say even if you’re short with R5000 you say: ‘can you [contribute] from our personal accounts and give to the business?”’

Two of the participants identified the support offered by employees and team members as a key factor. Bongani stated:

“I had a team with me, and they helped a lot”.

Likewise, Mike reported the vital role their events manager played in their business success:

“We wouldn’t have made it without her, she’s done an amazing job just managing day to day things”.

Sipho highlighted the impact of having role models explaining how the inspiration he drew from them inspired him to persevere despite facing challenges. He experienced his role models as a form or support and linked this to his business success. He said the following about his uncle:

“He has a business where he sells meat. He would make a profit like that and was able to beat the poverty.”

His mother was also a role model to him and an important example as he said:

“She never went to school, but she was able to sell chickens. So, it was always in her blood to run businesses, so I saw it from her and the way she did it”.

Having a role model was associated with the motivation for achievement of participants’ goals and visions, as role models were often a source of inspiration and someone from whom the participants could learn.

4Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore the factors perceived by young business owners to have been essential for business success. It became clear that support offered by business partners, team members and employees contributed to the range of skills or resources required during the initial phases and the later expansion of businesses. Supportive relationships helped the business owners to overcome environmental barriers, because it facilitated access to financial capital, resources, knowledge, labor, and marketing, which they did not have before. As such, networking into a broader community bolstered the social capital for participants. Varpio, Paradis, Uijtdehaage and Young aptly defined social capital as “the extent and nature of our connections with others and the collective attitudes and behaviors between people that support a well-functioning, close-knit society” (p.2) [49]. Having access to social capital has been found to contribute to business success as it assists an entrepreneur to gain direct or indirect resources that he or she might not otherwise have had access to [12, 49, 50].

Through supportive relationships the participants also broadened their access to clients in other communities, which then increased sales, profit, and financial capital. Therefore, a growing support network seemed to foster development of businesses - in keeping with the concept of systemic entrepreneurship [10]. Botman emphasized that systemic entrepreneurship should not solely focus on economic growth, but also on human development and having a social impact in individuals’ lives and communities [10]. Fulfilment of human rights such as political and civil rights, social and economic rights, and developmental and environmental rights could lead to dignity, justice, freedom, and equity. Individuals and institutions in society have to collaborate to fulfil these human rights, which includes the right to employment by supporting and creating a culture of entrepreneurship [51]. Therefore, support between individuals and support from the community, or systemic entrepreneurship, could not only enable successful business start-ups that lead to economic growth, but simultaneously contribute to economic justice and national unity in South Africa and similar low- and middle-income countries [10].

Occupational therapists who facilitate and/or support access to meaningful employment protect occupational rights, thus working towards the realization of occupational justice. For this reason, service provision should include facilitation into existing work, or exploration and creation of new opportunities for meaningful work. Towards this end, occupational therapists should recognize the contribution of relevant stakeholders from all sectors, including labor, education and health [52], in order to have a greater impact in addressing unemployment and supporting entrepreneurs.

Occupational therapists involved in supporting work-related transition need to broaden their focus to include guiding work-related transitions that fall outside traditional rehabilitation services provided in simulated environments. For occupational therapists practicing in LMICs this would include support in finding or creating new work. Because of limited formal work opportunities, the only viable option often would entail self-employment [43]. Occupational therapists who support self-employment initiatives could draw on the findings to enhance their services by recognizing, and educating on, the importance of support factors that could facilitate successful entrepreneurship and the social impact thereof. Our findings highlighted the role of the community and supportive relationships in achieving business success, suggesting a systematic entrepreneurship approach in which connections with the broader community are prioritized.

4.1Strengths and limitations

The use of narrative interviews, held in one of the businesses that other participants also visited frequently, contributed to an appreciation of the importance of connections and networks. Focusing on participants who conducted business in one community similarly facilitated identification of support factors.

Only one of the categories that emerged from the research is reported in-depth, which possibly leads to the findings being underrepresented. However, due to the nature of condensing information for a journal article, the researchers selected a category that was highlighted by the participants as important within their community, and the local and global research on support factors’ contribution to business success is limited.

5Conclusion

Support factors that were perceived by the participants to contribute to business success included family and friends, mentors, role models, business partners, and team members or employees.

All initiatives and role players that support the development of youth entrepreneurship, by providing funding, mentorship, education, or physical resources, should work together to develop young entrepreneurs and help them to form networks that could assist with job creation within areas characterized by low-socioeconomic circumstances. Occupational therapists equipped, with the knowledge from this study, could raise their client’s insight in terms of of the key role that support can play in achieving business success. The importance of community and business networks should be reflected in policies or guidelines developed to promote youth entrepreneurship, especially in lower income areas.

Acknowledgments

We developed deep respect for participants who meet day-to-day challenges with creativity and resilience; our sincere thanks for sharing your journeys, thus making this research possible.

Jenna Fish is acknowledged for the original drawings made to capture the businesses.

Declarations

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest.

Contributions of authors

Van Niekerk identified the topic, which was further refined by all authors who all contributed to all phases of the research. Data were collected and analyzed by Claassens, Fish, Foiret, Franckeiss and Thesnaar, who had successfully completed two modules in research methods at the time the interviews were done; Van Niekerk participated in peer debriefing. All authors contributed to authoring the article with Van Niekerk taking responsibility for final refinement and publication.

Funding

Funding was obtained from the Undergraduate and Honors Research Project Fund, Research Development and Support Division, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at Stellenbosch University.

References

[1] | Youth Employment Forum The Youth Employment Crisis: Highlights of the 2012 ILC report. 2012, International Labour Office: Geneva. p. 1-40. |

[2] | International Labour Organization World Employment Social Outlook: Trends 2019. 2019 [cited 2022 2022/11/08]; Available from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_670542.pdf |

[3] | Betcherman G , Khan T . Jobs for Africa’s expanding youth cohort: a stocktaking of employment prospects and policy interventions. IZA Journal of Development and Migration. (2018) ;8: (1). |

[4] | International Labour Organisation World Employment Social Outlook: Trends 2018. 2018, International Labour Office: Geneva. pp. 1-81. |

[5] | Carr SC , et al. How can wages sustain a living? By getting ahead of the curve. Sustainability Science. (2018) ;13: (4):901–17. |

[6] | Burchell BJ , Coutts AP . The Experience of Self-Employment Among Young People: An Exploratory Analysis of 28 Low-to Middle-Income Countries. American Behavioral Scientist. (2019) ;63: (2):147–65. |

[7] | Ahmad NH , Seet P-S . Dissecting Behaviours Associated with BusinessFailure: A Qualitative Study of SME Owners in Malaysia andAustralia. Asian Social Science.. (2009) ;5: (9):98–p98. |

[8] | Van Trang T , Do QH , Luong MH . Entrepreneurial human capital, role models, and fear of failure and start-up perception of feasibility among adults in Vietnam. International Journal of Engineering Business Management. (2019) ;11: , 184797901987326. |

[9] | Chimucheka T . Impediments to youth entrepreneurship in rural areas of Zimbabwe. African Journal of Business Management. (2012) ;6: (38):10389. |

[10] | Botman HR Opening Remarks by Prof H Russel Botman, in Colloquium on Systemic Entrepreneurship in a Dynamic Global Context. 2011: Coventry University, UK. |

[11] | Sautet F Local and Systemic Entrepreneurship: Solving the Puzzle of Entrepreneurship and Economic Development. 2011. |

[12] | Preisendörfer P , Bitz A , Bezuidenhout FJ Business Start-ups and Their Prospects of Success in South African Townships. (2012) ;43: (3):3–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2012.727542 |

[13] | Dhliwayo S , Van Vuuren JJ . The strategic entrepreneurial thinking imperative. Acta Commercii. (2007) ;7: (1):123–34. |

[14] | Neneh NB . An exploratory study on entrepreneurial mindset in the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector: A South African perspective on fostering small and medium enterprise (SME) success. African Journal of Business Management. (2012) ;6: (9):3364. |

[15] | Chen M-H , Chang Y-Y , Lo Y-H . Creativity cognitive style, conflict, and career success for creative entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Research. (2015) ;68: (4):906–10. |

[16] | Luk TK . Success in Hong Kong: Factors self-reported by successful small business owners. Journal of Small Business Management. (1996) ;34: (3):68. |

[17] | Gordon I , Hamilton EE , Jack SL A study of the regional economic development impact of a university led entrepreneurship education programme for small business owners. 2010. |

[18] | Khoury G , Elmuti D , Omran O Does entrepreneurship education have a role in developing entrepreneurial skills and ventures’ effectiveness? 2012. |

[19] | Fatoki O . The entrepreneurial intention of undergraduate students in South Africa: The influences of entrepreneurship education and previous work experience. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. (2014) ;5: (7):294. |

[20] | Abisuga-Oyekunle OA , Fillis IR . The role of handicraft micro-enterprises as a catalyst for youth employment. Creative Industries Journal. (2017) ;10: (1):59–74. |

[21] | Mayombe C . Graduates’ views on the impact of adult education and training for poverty reduction in South Africa. International Social Science Journal. (2016) ;66: (219-220):109–21. |

[22] | Mensah SA , Benedict E Entrepreneurship training and poverty alleviation: Empowering the poor in the Eastern Free State of South Africa. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies. 2010. |

[23] | Woodward D , et al. The viability of informal microenterprise in South Africa. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurshi. (2011) ;16: (01):65–86. |

[24] | Koloba H . Is entrepreneurial orientation a predictor of entrepreneurial activity? Gender comparisons among Generation Y students in South Africa. Gender and Behaviour. (2017) ;15: (1):8265–83. |

[25] | Visser T , et al. An analysis of small business skills in the city of Tshwane, Gauteng province. African Journal of Business and Economic Research. (2016) ;11: (1):93–115. |

[26] | Urban B , Naidoo R Business sustainability: empirical evidence on operational skills in SMEs in South Africa. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. 2012. |

[27] | Bosma N , Levie J Global entrepreneurship monitor: 2009 global report. 2010. |

[28] | Hill S , et al. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2022/2023 Global Report: Adapting to a“ New Normal”. 2023, Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. |

[29] | Isaacs E , et al. Entrepreneurship education and training at the Further Education and Training (FET) level in South Africa. South African journal of education. (2007) ;27: (4):613–29. |

[30] | Nelson RE , Johnson SD . Entrepreneurship education as a strategic approach to economic growth in Kenya. Journal of Industrial Teacher Education. (1997) ;35: , 7–21. |

[31] | Hikido A . Entrepreneurship in South African township tourism: The impact of interracial social capital. Ethnic and Racial Studies. (2018) ;41: (14):2580–2598. |

[32] | Kadam A , Ayarekar S . Impact of Social Media on Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Performance: Special Reference to Small and Medium Scale Enterprises. SIES Journal of Management. (2014) ;10: (1). |

[33] | Goetz SJ , Fleming DA , Rupasingha A . The economic impacts of self-employment. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics. (2012) ;44: (3):315–21. |

[34] | Oyelola O , et al. Entrepreneurship education: Solution to youth unemployment in Nigeria. Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development. (2014) ;5: (0):149–57. |

[35] | Chimucheka T . Overview and performance of the SMMEs sector in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. (2013) ;4: (14):783. |

[36] | Langevang T , Gough KV . Diverging pathways: young female employment and entrepreneurship in sub-Saharan Africa. The Geographical Journal. (2012) ;178: (3):242–52. |

[37] | Shava H , Rungani EC . Gender differences in business related experience amongst smmes owners in King Williams Town, South Africa: A comparative analysis. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. (2014) ;5: (20):2687. |

[38] | Rogerson CM . Developing SMMEs in peripheral spaces: the experience of Free State province, South Africa. South African Geographical Journal. (2006) ;88: (1):66–78. |

[39] | O’Halloran D , et al. An occupational perspective on three solutions to unemployment. Journal of Occupational Science. (2018) ;25: (3):297–308. |

[40] | Shaw L , et al. Directions for advancing the study of work transitions in the 21st century. Work (Reading, Mass.). (2012) ;41: (4):369–77. |

[41] | Mavindidze E , Van Niekerk L , Cloete L . Professional competencies required by occupational therapists to facilitate the participation of persons with mental disability in work: A review of the literature. Work. (2020) ;66: (4):841–8. |

[42] | Uys ME , Van Niekerk L , Buchanan H . Work-related transitions following hand injury: occupational therapy scoping review. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. (2020) ;87: (4):331–45. |

[43] | Buchanan H , Niekerk L . Work transitions after serious hand injury: Current occupational therapy practice in a middle-income country. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. (2022) ;69: (2):151–64. |

[44] | Gamieldien F , Van Niekerk L . Street vending in South Africa: An entrepreneurial occupation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. (2017) ;47: (1):24–29. |

[45] | Mavindidze E , van Niekerk L , Cloete L . Inter-sectoral work practice in Zimbabwe: Professional competencies required by occupational therapists to facilitate work participation of persons with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. (2021) ;28: (7):520–30. |

[46] | Salkind N Sample. Encyclopedia of Research Design. 2012. |

[47] | Salkind N Narrative Research. Encyclopedia of Research Design. 2012. |

[48] | Polkinghorne DE Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis, in Life History and Narrative, J.A. Hatch and R. Wisniewski, Editors. 1995, The Falmer Press: London. |

[49] | Varpio L , et al. The Distinctions Between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework. Academic Medicine. (2020) ;95: (7):989–994. |

[50] | Muofhe NJ , Du Toit WF . Entrepreneurial education’s and entrepreneurial role models’ influence on career choice. SA Journal of Human Resource Management. (2011) ;9: (1). |

[51] | Koopman N Entrepreneurship in (South) Africa? Some ethical considerations, in Colloquium on Systemic Entrepreneurship in a Dynamic Global Context. 2011: Coventry University; Coventry. |

[52] | Coetzee Z , et al. Re-Conceptualising Vocational Rehabilitation Services Towards an Inter-sectoral Model. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. (2011) ;41: (2):32–36. |