Wisdom-oriented coping capacities at work in challenging times

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Critical life events affect personal and professional lives, change working conditions, and require specific coping strategies. Wisdom is a multidimensional capacity for coping with life problems. Since wisdom can best be investigated in relation to concrete settings and problems, we investigated research employees during a pandemic. Research employees are constantly occupied with uncertainty and problem-solving in their everyday work. Thus, they develop capacities for factual and problem-solving knowledge which can be applied in different situations.

OBJECTIVE:

This study examines to what extent which wisdom capacities are applied by research personnel when dealing with changed working conditions.

METHOD:

During the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in 2021, researchers were asked about work-related coping capacities in an online survey. The qualitative content analysis of the free-text responses of 131 research employees was based on a multidimensional wisdom model with 12 wisdom capacities.

RESULTS:

50% of the reported coping strategies referred to factual and problem-solving capacities, 40% to interpersonal or emotional capacities, 10% did not reflect any wisdom capacity. Associations between wise coping capacities, social behavior at work, and eudaimonic well-being emerged.

CONCLUSION:

The study provides concrete qualitative examples of specific behavioral capacities in which wisdom may be applied in a work setting.

1Introduction

Critical life events and stress are normal, and people have to cope with them [1, 2]. But, in recent years, mankind has been more and more confronted with global challenges: migration, war, pandemic, climate change. Such events are unpredictable and threatening events that can occur at any time; the world is an “uncertain place” [3–5]. Coping with uncertainty, factual and problem-solving capacities, and social skills are therefore needed, and people must choose appropriate capacities in different in challenging life situations. This is what we may call wisdom [2, 3].

Wisdom is needed more than ever now in private life and work. Most people spend major day time at their workplaces. Until now, there is broad theoretical conceptualization of wisdom in developmental [6–9], organizational [10–12] and clinical research [13, 14]. But there have not been naturalistic qualitative investigations on the use of wisdom strategies in concrete work settings in times of a global crisis, when working people all face similar challenges and barriers in their working life.

This present study is one of the first to investigate qualitatively whether and which wisdom strategies employees from the field of research and development have applied for work coping during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Results inform about which wisdom strategies are predominantly and which are less often used in situations which require adjustment to suddenly changed work conditions.

1.1Wisdom capacities for coping with life challenges

Wisdom is required for not getting discouraged or embittered under life problems, but looking forward in a solution-oriented way, and making appropriate decisions in dilemma situations. Wisdom is a coping capacity for everyday as well as major life problems [7].

Wisdom is conceptualized as a trainable capacity, or a kind of personality dimension that can be developed. Behavior-oriented wisdom researchers refer to wisdom as an individual’s capacity to cope with complex demands and life stresses [13].

A current multidimensional model of wisdom integrates different wisdom capacities [3]. Wisdom capacities can be grouped to different topics (a) looking at the world (with factual and problem-solving knowledge, contextualism, value relativism), (b) looking at other people (ability to change perspective, empathy), (c) looking at oneself (problem relativism, self-relativism, self-distance), (d) looking at one’s own experience (emotion perception and emotion acceptance, emotional serenity and humor), and (e) looking at the future (uncertainty tolerance, sustainability). The multidimensional wisdom model describes capacities that help people cope with complex problems in life. These capacities are trainable [3, 13, 14].

Wisdom trainings have been developed in clinical and non-clinical settings [14–16]. In a university context, so-called “growth courses” provided instructional content on spirituality and health. Students who participated in these courses had significantly increased wisdom and well-being compared to the control group [15]. One common idea of wisdom concepts is to develop eudaimonic well-being in the sense of “doing good” - rather than simply “feeling good” [2, 3, 8].

1.2Wisdom at work –the example of research employees during pandemic

Applied wisdom can only be investigated in relation to a concrete social context [6]. Organizational wisdom and wisdom in organizations has a research tradition about 20 years now. Wisdom has been regarded in association with firm strategies, (international) joint ventures and company clusters, design of public institutions and national policies, product innovativeness and firm financial performance, but also leadership behavior and employee motivation [10–12]. Wisdom has been detected as one crucial factor underlying servant leadership, which is composed of a combination of awareness and foresight [10]. Wisdom has been argued important for keeping legitimacy and successful crisis management in organizations [10].

In this present investigation, the focus is not on organizational [10–12], but on individuals’ wisdom, i.e. concrete behavior of cognitive working employees in a global pandemic crisis which affected all work domains. The aim is to get insight which concrete wisdom behaviors have been chosen by research employees to come along with suddenly changed work situations. The work context of research employees is a work context in which applied wisdom capacities could be observed concretely during the challenging phase of pandemic.

Taking the recent pandemic as a timely example of life challenge and need for wisdom strategies, many people were affected from loss of social contacts, interpersonal disputes, grief for loved ones who died, loneliness and stigma associated with illness, financial losses, and unemployment [17, 18]. Researchers expected [17] and observed [19] an increase in embitterment during the pandemic, in response to a perceived injustice, humiliation, or a breach of trust [20]; pandemic management mistakes made it hard for some people to cope wisely [19]. Nevertheless, there are large interindividual differences in coping with life events, and not all people feel similarly burdened although facing the same life challenges [21]. Coping by using wisdom capacities may make a difference.

Researchers are a professional group who are constantly occupied with uncertainty and problem-solving in their everyday work. They are trained in analytical thinking, factual knowledge, practical problem solving, coping with uncertainty, and hitting deadlines. During the pandemic, surveys on researchers found that for example 50% of respondents perceived collegial interactions as difficult, or 61% found their scientific progress impaired [22]. A third of younger researchers experienced a decline in their publication activity [23].

The present qualitative exploratory study investigates which wisdom capacities can be inferred from researchers’ self-reported coping behavior at work during the pandemic.

2Method

In spring 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, research employees from a technical university were investigated about their work-related coping strategies during the pandemic [23]. The research protocol for this cross-sectional self-report survey was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Life Sciences of the Technische Universität Braunschweig, approval number FV 2021-09.

2.1Setting and procedure

In 2021, a pandemic largely impacted daily and working life of people worldwide. Pandemic-related nation-wide protective measures represented a potential burden for employees: employees had to stay away from their offices and laboratories, physically meeting of colleagues was not allowed, and work was done in home office over long time periods. Only one single person was allowed to be in an office. Therefore, meetings, project work, teaching, and all works including interaction with colleagues and collaborators had to be done by video conferences. Many employees were not well equipped with technical resources and especially space for working adequately in home office: Employees with care responsibilities (children, parents) often had the problem not to find enough space and time for working at home (beside household duties, caring about children, home schooling, and increased organizational and logistic requirements over all life domains).

Invitation for participation in the study on coping with challenges during the pandemic was distributed via a technological university’s mailing list to 2280 scientific employees. Quantitative data from the survey have already been reported [23]. The survey included a qualitative question on work coping strategies: “Which coping strategies have you applied during the coronavirus pandemic, both at work and in private life?” Answers to this question are content of this present qualitative analysis. The researchers’ free-text responses on this qualitative question have been classified according to the 12 wisdom capacities of the multidimensional wisdom model [3] using a content-structuring qualitative analysis [24]. For a quantitative descriptive overview, frequencies, and distributions of the reported strategies according to the wisdom capacities have been calculated with SPSS 26.

2.2Sample

Of 504 researchers who responded to the survey, 373 answered any of seven qualitative questions (six of the questions were not related to work coping), and 131 (26% of survey participants) answered the specific qualitative question about work-related coping strategies. The qualitative reports given to the coping question were analyzed.

The sample consisted of 63 women, 65 men, one person who identified as diverse, and two people who did not provide gender information. The average age of the participants was 34.97 years (SD = 7.18), with the youngest participant being 24 years old and the oldest 57 years. Among the 131 individuals who had responded to the question about coping strategies were doctoral students (n = 77), postdoctoral fellows and assistant professors (n = 39), and other research assistants (n = 15). The structure of this convenience sample speaks for a valid selection of the broad variety (age, gender, status) of research employees from a state technological university.

2.3Qualitative analysis

Twelve categories of wisdom capacities were deductively derived [24] from the 12 wisdom capacities of the multidimensional wisdom model [3]. Participants’ text statements (N = 131) were divided into 284 text segments, so that each text segment included one self-reported coping behavior. Several participants (n = 61) reported more than one coping strategy.

In the first coding process, one third of all text segments was assigned to one wisdom capacity. Since subcategories allow for better differentiation, three subcategories were derived inductively [24] for the capacity “factual and problem-solving knowledge”. These subcategories were “structuring”, “cooperation”, and “resources”.

In addition, the main category “no wise coping strategy” was formed for text segments that could not be assigned to any category of wisdom capacities. This was the case when the content of the text segments did not indicate any wisdom-related coping.

In the second coding process, all text segments were coded using the category system developed consisting of 13 main categories (12 wisdom capacities and 1 category named no wise coping).

Finally, an advanced psychology student checked the result for plausibility. In seven of the total 284 assignments, the coding seemed incomprehensible to her. In consequence, five text segments were recoded, and a consensual decision was made for two text segments. Subsequently, both raters declared the text segments being plausibly arranged in the coding system with 12 wisdom capacities, and one category “no wise coping strategy” (Table 1).

Table 1

Wisdom capacities according to the multidimensional wisdom model [4] and their definitions, context-specific wise coping strategies derived from the text segments, example quotes from the interviewed research employees (N = 131)

| Wisdom capacities | Definition of the wisdom capacities according to Linden et al. (2019) | Definition of wise coping strategies in the work context | Typical statements given by research employees |

| Factual and problem-solving knowledge | General and specific knowledge of problems and problem constellations, knowledge about what constitutes problems and which possibilities there are for solving them | Structuring:Decrease of personal stress factorsCooperation:Building reliable communicationResources:Use of support services | “drawing clear boundaries between work and leisure by putting the laptop away in the bag after working time finished”“time planning with partner, who has to work when”.“strengthen [the children’s] self-management and independence”. |

| Contextualism | Knowledge of the temporal and situational embeddedness of problems and the numerous circumstances in which a life is embedded | Attention to the interaction between situational factors and individual abilities | “within flexible working hours and home office I can find some individual advantages” |

| Value relativism | Knowing the diversity of values and life goals and the need to look at each person within their value system, without losing sight of a small number of universal values | Make decisions and respect the decisions of others | “setting clear priorities; some things which normally get priority have to be valued new under changed conditions” |

| Change of perspective | Ability to describe a problem from the point of view of different people involved in it | Coordinate one’s own work actions with others | “support each other, do ut des” |

| Empathy | Ability to empathy with the emotional experience of another person | Experience the joy and chances through communication and exchange | “talking to friends and family and understanding their situations is important” |

| Relativism of problems and aspirations | Ability to be humble and to accept that one’s own problems may not be taken so seriously in comparison with many problems in the world | Efforts to see one’s own stresses in a larger context | “reduce one’s own achievement entitlements according to the frame the situation allows” |

| Self relativism | Ability to accept that one’s self is not always most important and that many things do not align with one’s own interests | Willingness to balance interests and needs in cooperation | “flexibility” |

| Self distance | Ability to recognize and understand perceptions and evaluations of oneself from the point of view of other people | * | * |

| Emotion perception and emotion acceptance | Ability to perceive and accept own feelings | Realistic assessment of one’s own moods, needs and abilities | “Plan working hours according to the mood and fitness of the day” |

| Emotional serenity and humor | Ability to be emotionally balanced, to control one’s own emotions according to the requirements of the situation, as well as the ability to look with humour at oneself and one’s own difficulties | Take time for what is good for you and also have fun sometimes | “consciously set rest breaks”“inner serenity:D” |

| Uncertainty tolerance | Knowledge of the inherent uncertainty of life regarding past, present and future | Have confidence to do the best possible under conditions of uncertainty | “In the meantime, colleagues have been vaccinated. That does not mean [the colleague with a chronic illness] is completely safe, but it reduces the danger for her.” |

| Sustainability | Knowledge of negative and positive aspects of every event and behavior, as well as short- and long-term consequences, which can also contradict each other | Reflect on one’s own actions and be clear about consequences | “Enduring home office priority endangers outcome for many practical experiments”. |

| No wise coping strategy | Coping behavior which does not contain any aspect of the 12 wisdom dimensions, but rather ideas which are hardly helpful | “I did not get any support” |

Notes. * The analysis of the text material did not reveal an assignment of a self-reported coping strategy to the category self-distancing. Therefore, no corresponding context-specific definition could be formulated.

3Results

3.1Categories of context-specific wise coping strategies

Twelve categories of wisdom capacities were based on the multidimensional wisdom model [3]. One category “no wise coping strategy” was added (Table 1).

The 131 researchers described various work-related coping behaviors. 89.3% of the researchers reported at least one wisdom-oriented coping behavior. 10.7% of the researchers did not mention any wisdom-related coping.

There were some differences in the distribution of wisdom coping strategies mentioned by women and men, and younger (doctoral students) versus more experienced researchers (post docs and professors):

Regarding gender, the factual and problem-solving strategies were more often mentioned by women (62% of the strategies were given by women) than by men (38%). All other wisdom strategies (including perspective change, and strategies with self- and problem relativization were given to 45% by women and 55% by men). Concerning the few statements without any wise coping content, 63% of these were given by women, 34% by men.

Regarding job experience stage, wisdom coping statements were similarly given by early career (doctoral) and senior (post doc, professor) researchers, according to the distribution of doctoral (59%) and senior researchers (41%) in the sample. The proportion of doctoral researchers in strategies of no wise coping was 73%, in factual and problem solving 56%, in all other wisdom strategies 70%).

3.2Wise coping behaviors

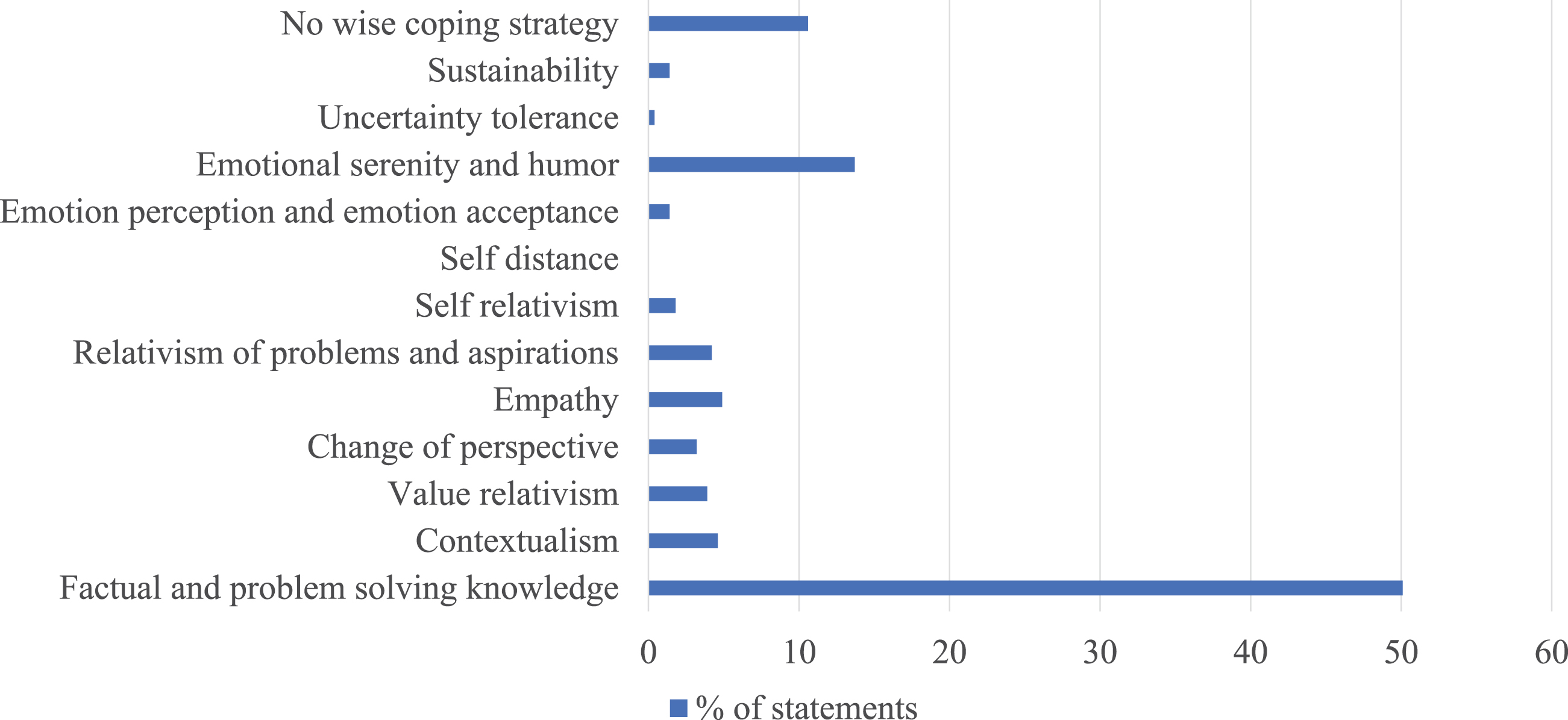

Each text segment given by the interviewed research employees contains a self-reported coping behavior. The most frequently mentioned coping strategies (142 out of a total of 284 text segments, Table 1) were in the category “factual and problem-solving knowledge”. This category comprises 50.1% of all text segments (Fig. 1). The distribution of text segments within this category is balanced on the topics resources (n = 49), structuring (n = 49), cooperation (n = 44).

Fig. 1

Distribution of work-related coping strategies (N = 284 text segments) according to categories of 12 wisdom capacities and the additional category “no wise coping strategy”.

Emotional serenity and humor appear as the second strongest category with 39 text segments. With 13.7% of the text segments, it directly follows the problem-solving subcategory cooperation. No text segment was assigned to the self-distance category. The category no wise coping strategy contains 30 text segments, which is 10.6% of all 284 text segments.

4Discussion

This qualitative study is one of the first to investigate wisdom-oriented coping behaviors at work in a real-life situation, using research employees in the pandemic as an example. By categorizing [24] spontaneous reports on work coping during the pandemic, it was found that eleven out of twelve wisdom-oriented coping strategies were used by researchers to cope with pandemic-related work stress.

The first important result is that almost 90% of the researchers’ reports included coping behavior that could be assigned to any of the twelve wisdom capacities. This may be a hint that the majority of investigated employees were successful in coping with the daily challenges during the pandemic.

However, about 10% of the researchers (and also of the text segments) reflected no wisdom-related coping. This result matches a population-representative study [25], where 90% of Germans rated themselves as moderately “wise” (operationalized with quantitative agreements to general wisdom ideas [3]), and 6% very wise. Yet, 4% of these general population people showed very low agreement with wise coping ideas. It is possible that the rate of “no wise coping” is higher in our qualitative study (10%) because here coping strategies had to be stated free and actively, whereas the representative study asked for agreement to given strategies, which makes it easier to score positively for wisdom [26].

Among the research employees investigated here, a lack of wise coping strategies may indicate a lower level of stress coping capacities, or frustrated overload [23]. Some reports point in this direction, e.g. “[I don’t know] what coping strategies there are in case of pandemic”, “I try to stay calm and function, but with so much pressure at work, the patience is very low”, or “There are no real relief strategies, because the expectations from all sides - project sponsors, supervisors, students - have remained the same, but the way of working has become more difficult.”, or even “I did not receive any support”.

The second important result is that most of the coping behaviors targeted problem solving: half of all reported coping strategies were categorized as factual and problem-solving knowledge (50.1%). The many ideas in this category allowed for inductive differentiation within the category. The identified coping behaviors - structuring, cooperation, and trying to use available resources - could be a reflection of the analytical, practical, and creative skills [27] researchers develop during their training, and which have been applied in work-coping during the pandemic: Thanks to analytical intelligence, the investigated researchers might have recognized the advantages and disadvantages of the new work situation (“flexible working from home, positive experiences for care work”, “unnecessary travel has been eliminated.”, “it is hard to declare working time “finished” in home office”). Thanks to creative intelligence, researchers might have found ways of adapting to the changed working conditions and activated resources (“taking advantage of opportunities to talk and initiating them themselves,” “support in teaching from staff in project positions,” “external part-time childcare can help concentration”). Practical intelligence may have enabled them to communicate with others in ways that led to the implementation of the individual solution or to a shared solution path (“Co-working online,” “Clearly dividing work and other zones in the home,” “Delegation/stronger transfer of responsibility to co-workers”). Such practical and creative intelligence can have a high impact on people’s ability to adapt in stressful life situations [28, 29].

As a third result, wise coping behaviors seem to affect not only the individual, but also interpersonal and context level, as about 40% of coping strategies were about emotional serenity and humor, different types of relativism, and empathy and perspective change. This is in line with the empirical literature which suggests that the degree of wisdom is not only a predictor for ethical attitudes, but also affects work behavior [30]. Corporate practices that had a negative impact on others or the environment were more likely to be rejected. Also, some aspects of the behavior of the researchers studied here were targeted at the social work environment, e.g. “I took on more tasks to relieve colleagues with children”, “We became clearer in communication”, or “I tried to reduce own performance demands”.

Interestingly, self-distance was the only wisdom capacity which was not represented within the reported coping strategies. One explanation could be that the interview question explicitly asked about work-related coping strategies. This question may have focused the researchers on their own experience and behaviors rather than on comparison with or reference to others. If other interview questions or reference frames would have been used, e.g., about resolution strategies for team or family problems, or about researchers’ roles concerning scientific communication in society, respondents might have mentioned self-distancing coping strategies as well.

Finally, the qualitative data illustrate some link between wisdom and mental health. People without mental health problems usually rate their wisdom and coping higher than people with mental health problems [25]. Statements from the researchers interviewed here indicated how they were able to regulate their well-being. Interestingly, these reports mainly focus on active behavior, rather than passive seeking of external help or care from others. Researchers said that they used to “meditate,” or engage in “exercise, gardening, playing the piano,” or having “time out in the fresh air”. Other statements indicated a lack of subjective well-being and rather passive status reports, e.g. “I did not receive support,” or “I got more work, less free time” and “little sleep”. This fits with the idea that wisdom is more closely associated with eudaimonic well-being than with passively waiting for help or well-being from external sources. Wisdom mainly contains ideas of eudaimonic wellbeing in the sense of doing good, instead of passively seeking for joy [31].

4.1Limitations

The first limitation is the self-selective sample: Only 131 out of 504 participants gave qualitative information on their work coping, thus we do not know which work coping capacities the majority of respondents applied.

A general important limitation is the methodological challenge in wisdom determination: Measuring wisdom is a complex methodological issue [8, 26]. In some research wisdom is understood as a dimensional characteristic [3, 9]. This present study used a qualitative categorical approach by assigning behavior self-reports to wisdom categories by two independent raters. Dimensional expressions of wise behavior (e.g. quantitative degree of wisdom [32]) are not possible in this way.

The choice of wisdom concept may be seen as a limitation: The results, i.e. the distribution of the participants’ work coping statements over the wisdom categories depend on the chosen wisdom concept: The definition of the wisdom categories was deductively derived from the multidimensional wisdom model [3]. A different wisdom model would result in a different category system and different distribution of the participants reports. We chose the multidimensional wisdom model [3], because it contains a broad variety of twelve capacities which are all potential strategies for coping with challenging life situations, problems and daily uncertainties, i.e. situations where there is no clear right or wrong.

Another limitation is the specific sample: In the present study, the text material consisted of self-reported work coping strategies of research employees at a technical university. Reports from other professional groups and work contexts, e.g., nurses, teachers, or unemployed people, would lead to a different category system, different definitions of context-related wise coping strategies, and different distributions.

5Conclusion and outlook

A “special feature” of this study is the investigation of wisdom coping strategies not only of a specific occupational group, but also in a specific naturalistic globally stressful context which affected all employees.

The qualitative investigation shows that self-reported coping strategies from a specific professional group can be classified according to established wisdom capacities.

This study provides examples of specific behavioral strategies that are associated with wisdom capacities in a particular work setting, such as employees who are project-based, problem-solving, and analytical.

Further research is needed to explore and compare wisdom capacities in different professions (e.g. social and service professions, versus crafts persons or industrial workers, versus office workers). Many modern work contexts bring about uncertainties and need for uncertainty tolerance and flexible adjustments, e.g. contexts of organizational restructuring, or personal job change situations, e.g. when entering a new job position, or a new occupational field. These are also fields for further investigations.

The question is whether different professions use and need similar wisdom capacities, or whether different context require different capacities. Accordingly, wisdom trainings can be conceptualized to specific needs (e.g. leadership, [33, 34]) or rather globally [14, 32].

Wisdom training [35] in the work context can enhance positive work behaviors [35], and thus support work ability, work productivity, and work satisfaction. Eudaimonic well-being at work [36] has been identified as an important aspect in modern working life. Wisdom-oriented reflections about work-related eudaimonic values may be further evaluated in naturalistic work settings, and thereby contribute to quality improvement of work outcomes [37]. Work-oriented wisdom trainings can target a broader range of relational, interactional, and context-oriented wisdom capacities, rather than focusing only on problem solving, as many work interventions have done to date [38]. Wisdom trainings seem to be valuable occupational health interventions, because they do not only support work efficiency and successful problem solving, but at the same time employees’ mental health.

Ethical approval

The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Life sciences of the Technische Universität Braunschweig, approval number FV 2021-09.

Informed consent

Employees participated voluntarily and provided written informed consent.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

B.M. designed the study, A.S. and B.M. developed the research question, A.S. collected the data, and drafted the manuscript. B.M. wrote and revised the manuscript. Both authors contributed equally to this research.

References

[1] | Muschalla B , Kampczyk U . Coping with hard times is not a mental illness –About the normality of critical life events and psychosocial burdens which are normally not the cause of mental illness. Praxis Klinische Verhaltensmedizin und Rehabilitation. (2020) ;33: (2):219–222. |

[2] | Linden M . Euthymic Suffering and Wisdom Psychology. World Psychiatry. (2020) ;19: (1):55. |

[3] | Linden M , Lieberei B , Noack N . Weisheitseinstellungen und Lebensbewältigung bei psychosomatischen Patienten [Wisdom Attitudes and Coping In Life of Psychosomatic Patients]. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, medizinische Psychologie. (2019) ;69: (8):332–338. |

[4] | European Commission, Directorate-General for Communication [homepage on the internet]. Standard Eurobarometer 97 –Factsheet, European Commission; 2022 [cited 2022 dec 19]. Available from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/file?deliverableId=83445 |

[5] | Reddemann L Die Welt als unsicherer Ort. Psychotherapeutisches Handeln in Krisenzeiten [The world as an uncertain place. Psychotherapeutic action in times of crisis] (Leben lernen, Bd. 328). Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta; 2021. |

[6] | Grossmann I , Kung FYH , Santos HC Wisdom as State versus Trait. In Sternberg RJ, Glück J, editors. The Cambridge handbook of wisdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2019. pp. 294-273. |

[7] | Ardelt M , Jeste DV Wisdom as a Resiliency Factor for Subjective Well-Being in Later Life. In: Muschalla B, Meier-Credner A, editors. Weisheit und Belastungsbewaltigung [Wisdom and coping with stress]. Psychosoziale und Medizinische Rehabilitation. 35 (2), [Themenheft]. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 2022. pp. 13-28. |

[8] | Bangen KJ , Meeks TW , Jeste DV . Defining and Assessing Wisdom: A Review of the Literature. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. (2013) ;21: (12):1254–1266. |

[9] | Ardelt M . Empirical assessment of a three-dimensional wisdom scale. Research on Aging. (2003) ;25: (3):275–324. |

[10] | Kessler EH . Organizational Wisdom: Human, Managerial, And Strategic Implications. Group & Organization Management. (2006) ;31: (3):296–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601106286883 |

[11] | Pinheiro P , Raposo M , Hernández R . Measuring organizationalwisdom applying an innovative model of analysis. Management Decision. (2012) ;50: (8):296–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211262033 |

[12] | Akgün AE , Keskin H , Kírcovalí SY . OrganizationalWisdom Practices and Firm product Innovation. Review of Managerial Science. (2019) ;13: (1):57–91. |

[13] | Baumann K , Linden M Weisheitskompetenzen und Weisheitstherapie. Die Bewältigung von Lebensbelastungen und Anpassungsstörungen [Wisdom capacities and wisdom therapy. Coping with life’s adverities and adjustment disorders]. Lengerich, Berlin, Bremen, Viernheim, Wien: Pabst Science Publ; 2008. |

[14] | Linden M , Baumann K , Lieberei B , Lorenz C , Rotter M . Treatment of posttraumatic embitterment disorder with cognitive behaviour therapy based on wisdom psychology and hedonia strategies. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. (2011) ;80: (4):199–205. |

[15] | Ardelt M . Can wisdom and psychosocial growth be learned in university courses? Journal of Moral Education. (2020) ;49: (1):30–45. |

[16] | Schrader K , Muschalla B . Subjective Wisdom and Wisdom Attitudes over the Course of a Short Wisdom Training. Psychosoziale und Medizinische Rehabilitation. (2022) ;118: :29–36. |

[17] | De Sousa A , D’souza R . Embitterment: The Nature of the Construct and Critical Issues in the Light of COVID-19. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). (2020) ;8: (3):304. |

[18] | Kaur M , Goyal P , Goyal M . Individual, Interpersonal and Economic Challenges of Underemployment in the Wake of COVID-19. WORK. (2020) ;67: :21–28. |

[19] | Muschalla B , Vollborn C , Sondhof A . Embitterment as a specific mental health reaction during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychopathology. (2021) ;54: (5):232–241. |

[20] | Linden M , Arnold C . Embitterment and Posttraumatic Embitterment Disorder (PTED): An Old, Frequent, and Still Underrecognized Problem. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. (2021) ;90: (2):73–80. |

[21] | Manchia M , Gathier AW , Yapici-Eser H , Schmidt MV , Quervain de D , van Amelsvoort T , et al. The impact of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. European Neuropsychopharmacology: The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. (2022) ;55: :22–83. |

[22] | Woolston C . Pandemic darkens postdocs’ work and career hopes. Nature. (2020) ;585: (7824):309–312. |

[23] | Muschalla B , Sondhof A , Wrobel U Children, care time, career priority - What matters for junior scientists’ productivity and career perspective during the COVID-19 pandemic? Work (Reading, Mass.). 2022:391-397. |

[24] | Kuckartz U , Rädiker S Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstutzung. Grundlagentexte Methoden [Qualitative content analysis. Methods, practice, computer support. Basic texts Methods]. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa; 2022. |

[25] | Muschalla B , Borchers P , Ohme S , Elster CC Chronische Erkrankungen und Belastungsbewältigung mittels Weisheitsfähigkeiten 2022. Eine Zusammenstellung von Repräsentativdaten. Abschlussbericht zum Forschungsprojekt im Bereich der Rehabilitation. REP Weisheit Abschlussbericht 220510 [Chronic disease and coping with stress using wisdom capacities in the general population. A representative study. Technical report]. Braunschweig: Technische Universitat Braunschweig, Psychotherapie und Diagnostik; 2022. |

[26] | Glück J . Measuring Wisdom: Existing Approaches, Continuing Challenges, and New Developments. The journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. (2018) ;73: (8):1393–1403. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx140 |

[27] | Sternberg RJ . A Broad View of Intelligence: The Theory of Successful Intelligence. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research. (2003) ;55: (3):139–154. |

[28] | Grigorenko EL , Sternberg RJ . Analytical, creative, and practical intelligence as predictors of self-reported adaptive functioning: a case study in Russia. Intelligence. (2001) ;29: (1):57–73. |

[29] | Sternberg RJ , Karami S . A 4W Model of Wisdom and Giftedness in Wisdom. Roeper Review. (2021) ;43: (3):153–160. |

[30] | Oden CD , Ardelt M , Ruppel CP . Wisdom and Its Relation to Ethical Attitude in Organizations. Business & Professional Ethics Journal. (2015) ;2: (34):141–164. |

[31] | Waterman AS . Reconsidering happiness: A eudaimonist’s perspective. Journal of Positive Psychology. (2008) ;3: (4):234–252. |

[32] | Meier-Credner A , Eberl-Kollmeier M , Muschalla B Similar Wisdom Capacities for Different Life Problems. Psychotherapie –Psychosomatik –Medizinische Psychologie, 2023; doi: 10.1055/a-2109-3512. Online ahead of print. |

[33] | Lehmann-Willenbrock N , Meinecke A L , Rowold J , Kauffeld S . How transformational leadership works during team interactions: A behavioral process analysis. The Leadership Quarterly. (2015) ;26: (6):1017–1033. |

[34] | Garad A , Yaya R , Pratolo P , Rahmawati A The relationship between transformational leadership, improving employee’s performance and the raising efficiency of organizations. Management and Production Engineering Review, 2022. DOI: 10.24425/mper.2022.142052 |

[35] | Muschalla B , Meier-Credner A editors Weisheit und Belastungsbewältigung [Wisdom and coping with stress]. Psychosoziale und Medizinische Rehabilitation, 35 (2). Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 2022. |

[36] | Fay D , Schwake C , Strauss K , Urbach T A Dual Pathway Model of Daily Proactive Work Behavior on Hedonic and EudaimonicWell-Being. In: Academy of Management Proceedings. Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management. 2020; 13912. |

[37] | Glück J . . . . and the Wisdom to Know the Difference: Scholarly Success From a Wisdom Perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science. (2017) ;12: (6):1148–1152. |

[38] | Arends I , Bruinvels DJ , Rebergen DS , Nieuwenhuijsen K , Madan I , Neumeyer-Gromen A , Bültmann U , Verbeek JH . Interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with adjustment disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2012) Dec 12;12: :CD006389 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006389.pub2. PMID: 23235630. |