The dual responsibility of employed family carers and how detrimental outcomes can be prevented

Dear Editor,

We write to underline the complexity of balancing caregiving work with employment, laying emphasis on the resulting health, socio-economic and personal effects of these roles. In response to this, we offer evidence-based strategies on how undesirable outcomes can be prevented or alleviated among this cohort.

It has been asserted that caregiving work –the unpaid support of people with chronic disease, disability, or frailty –will impact everyone at some juncture; individuals will either actively engage in caregiving work or will need a carer [1]. We consciously refer to the act of caregiving as ‘work’ because mental and physical resources are exerted; however, it is regrettable that the corresponding financial and social recompense that is societally associated with labor is not awarded [2].

Caregiving is often undertaken alongside employment; evidence from Europe (2017) [3], America (2015–17) [4] and Australia (2019) [5] indicates that at least 50% of those who engage in unpaid care work also participate in employment. Concerningly, caregiving work is not appreciated for its direct economic value, therefore, the rights of those who engage in caregiving work alongside employment are likely to be marginalized; this is despite the additional effort, extended hours, financial pressures, mental and physical health detriments that often result [6, 7]. The day-to-day tasks that caregivers undertake as an adjunct to their employment include, medical advocacy, medication management, providing support with activities of daily living including personal hygiene, nutrition, mobility, transport, home maintenance, financial management, companionship, and health monitoring [8]. These responsibilities are often undertaken without the necessary support services, training, recognition, and financial recompense [8]. Many are ill-prepared for the drawbacks associated with caregiving, which is further compounded by the fact that caregiving may not synchronize harmoniously with employment [8].

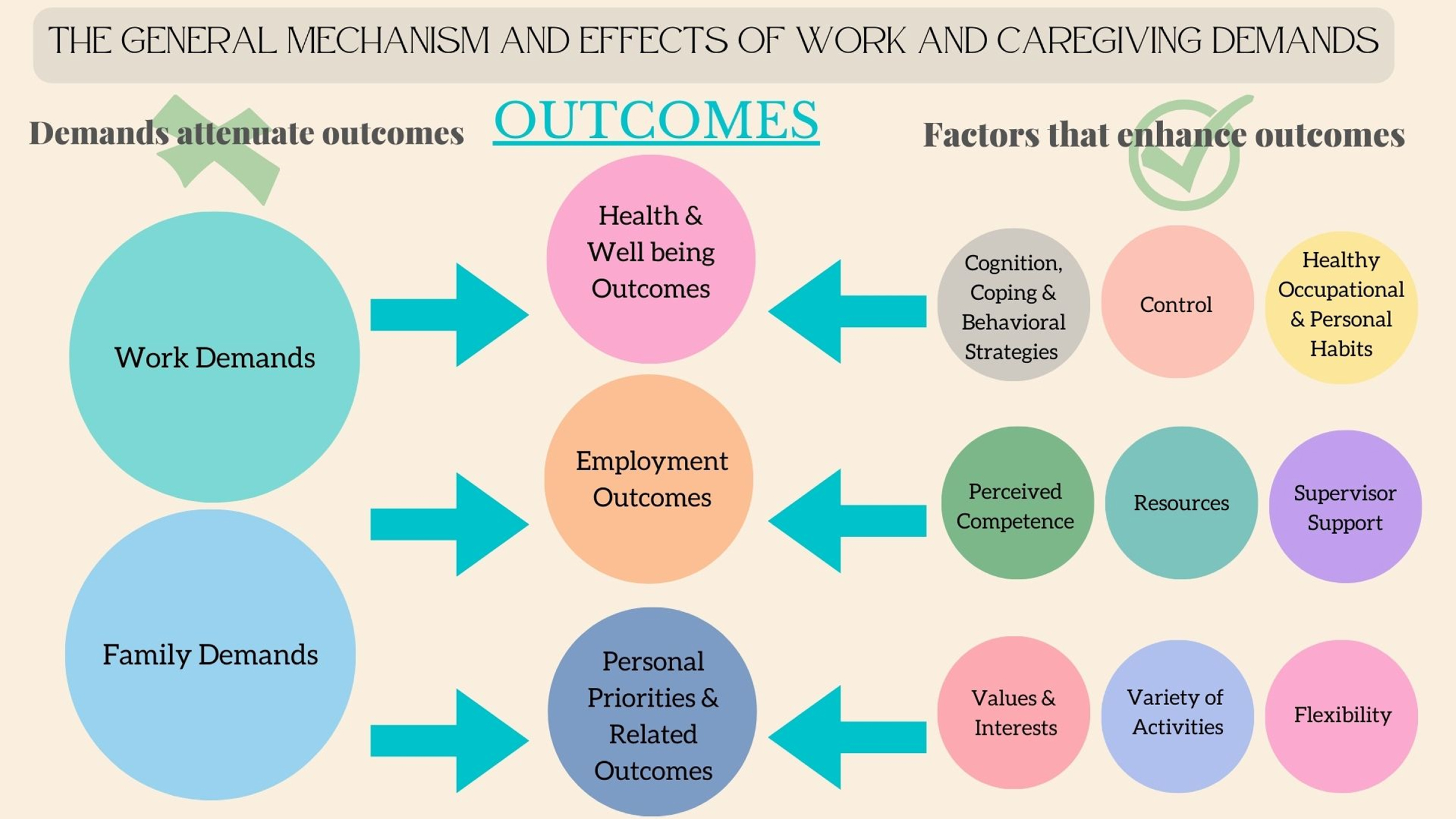

Theoretical frameworks pertaining to the experience of employed carers such as ‘work-family conflict’ postulate that employed family carers experience incompatibility between the work and family domains of their lives [9]. The dimensions of work and family exist in a dynamic state of balance and imbalance because there is constant tension between the time, energy, demands, stressors, responsibilities, and resources required for each of these domains [9]. This conflict exists because individuals have limited capacity and there is continual withdrawal from the resource ‘pool’ of time and energy [9]. This tension gives rise to adverse outcomes related to mental health, physical health, employment, and other personal priorities [9, 10]. Mental health consequences of contention between work and family comprise decreased satisfaction with work and family roles, poor self-image, decreased coping ability, stress, strain, and spillover of emotions between the work and family domains; conversely, physical health drawbacks comprise strain owing to over-exertion, exhaustion, and susceptibility to ailments and illnesses such as heart disease, and cancer [11, 12]. Employed family carers are less adept at managing their own health due to various competing demands, which may inhibit their ability to care for others [13].

Moreover, employment is also adversely affected, and this is evidenced by employment turnover, changes to time spent at work, job discrimination, decreased income, career regression, and early retirement –some of these drawbacks represent the opportunity costs associated with caregiving [12]. Negative employment outcomes are exacerbated by the increased cost of living and higher household costs incurred during caregiving [14]. Socially, employed family carers are likely to experience loneliness and social exclusion from society due to the duality of their responsibilities [14]. Other more general outcomes related to the dissention of work and family domains are role overload, marital or relationship strain, and changes to the distribution of time across caregiving and leisure [12].

Successful work-life integration would be the ultimate ideal for working family carers; however, even when this cannot be attained, enhanced accord between the domains of work and family can be realized and thus should be sought [9]. Empowering working family carers with knowledge on strategies related to coping, cognition, and behavior when dealing with a stressful work or family situation can augment this sense of work-life integration, along with establishing a perceived sense of competence by providing training related to the workplace or caregiving role, and the personal habits of the family carer in question; training offered in the workplace should give consideration to scheduling of caring responsibilities [15]. On a more personal front, work-life integration is strengthened if working family carers participate in activities other than those that pertain to the caring responsibility, uphold their own values and interests, and negotiate between the domains of work and family with the aim of gaining flexibility in either of these areas [15]. Other factors that may heighten the sense of work-life integration among working family carers include taking on fewer demands and stressors, heightened control in their work or family life domains, and accessing necessary resources and supervisory support in the workplace [11]. Signs of increased accord in the lives of working family carers may include synergy between the work and family domains, enrichment of work or family roles due to participating in the alternate role, good health and wellbeing, and productivity at work [16, 17].

Employers and co-workers are key stakeholders in the dualistic experience of working family carers [12]. Workplace strategies that aim to enhance the experience of working family carers ought to be undergirded by policies that formalize many of these efforts [12]. Workplace strategies that could be applied by employers to alleviate the burden on working family carers consist financial assistance, which could take the form of benefits, insurance schemes and subsidized care services [12]. Workplaces also ought to create an awareness culture around working family carers and this can be achieved by training line managers and employees on the challenges working family carers contend with and the various supports that are accessible to caregivers in the workplace [12]. This will empower line managers and coworkers to support family carers due to familiarity with the ideal course of action [12]; line managers are especially seminal as it pertains to the working family carer’s experience as they are the default link to organizational supports and information [12]. In some cases, working family carers are reliant on informal and flexible arrangements made with line-mangers in an effort to effectively manage workplace responsibilities alongside caregiving thus it is crucial that line-managers are sensitized and trained for this [12].

A core support which is central to enhanced work-life balance that should be made available to working carers is workplace flexibility in the form of adaptable work hours, remote working options and leave policy which suits various caring situations [12]. Organizations can adopt different models and policies such as paid or unpaid leave, emergency leave, different number of leave days based on the different caregiving circumstances and building up time in lieu [12]. Availability and awareness of these provisions creates a supportive workplace culture that enables working family carers to access the necessary resources [12]. Finally, work-place well-being initiatives in the form of support groups, counselling services, health promotion programs and occupational health services could help mitigate some of the negative health effects linked with caring [12]. The advantage of having these services in the workplace, and available at different times during the day is that working family carers who have over-stretched schedules and require such services, are in close proximity and can easily obtain access to them [12].

Family and friends play an integral role in supporting working family carers to attain a level of harmony in the integration of their work family roles [12]. They can assist working family carers by offering relief with care where practicable [12]. Relationships with friends and family can be a source of emotional support which can contribute to how much resilience working family carers have in their role [12]. When family and friends recognize the contributions of working family carers, then they inadvertently feel more positive about their circumstance [12].

Recent governmental policies have been introduced in the EU which make provision for the unique needs of carers. The Work Life Balance and Miscellaneous Provisions Act 2023 provides 5 days unpaid leave annually for carers to see to a serious medical condition, and prior employer notice is not a prerequisite for taking this leave [18]. In Ireland, employees can apply for carers’ leave under the Carer’s Leave Act 2001, which is afforded to care for a recipient in need of full-time attention, and is available for a maximum of 104 weeks, and a minimum of 13 weeks can be taken [19]. Paid carer’s leave does not exist as a national policy in Ireland but there are financial compensatory measures available for carers on low incomes, carers who have had to reduce their work hours due to caregiving and for full-time carers [20–23]. Workplaces can support employed carers by providing information on these national supports for employees [12].

As discussed here and illustrated in Fig. 1, elements which boost work-life integration are oftentimes within the control of employed family carers and stakeholders involved. Thus, the responsibility of mitigating the deleterious effects associated with the dual role of employed family carers is the collective responsibility of employers, workplace coworkers, policy makers, government representatives, family carers, as well as family and friends. Subsequently, consensus and consistent support strategies may be needed across all these levels by applying the principles highlighted here, including enhanced flexibility and control of work and family life, lessening demands or stressors in the lives of family carers, and providing them with the necessary resources and support at home and in the workplace.

Fig. 1

The General Mechanism and Effects of Work and Caregiving Demands.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Health Research Board for funding this research as part of the CAREWELL project.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Research Board Emerging Investigator Award [grant reference: EIA-2017-039].

References

[1] | Carter R And Thou Shalt Honor: The Caregiver’s Companion: Rodale Books; 2003. |

[2] | University of Michigan. Caring for Our Caregivers: The Unrecognized and Undervalued Family Caregiver 2020 [cited 2022 Aug 12]. |

[3] | EUROCARERS. EUROCARERS’ POLICY PAPER ON INFORMAL CARE AS A BARRIER TO EMPLOYMENT 2017 [cited 2022 May 31]. Available from: https://eurocarers.org/publications/informal-care-as-abarrier-to-employment/. |

[4] | Edwards VJ , Bouldin ED , Taylor CA , Olivari BS , McGuire LC Characteristics and health status of informal unpaid caregivers—44 States, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2015–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. (2020) ;69: (7):183. |

[5] | Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings Canberra Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019 [cited 2022 11 July ]. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release#::text=There%20were%202.65%20million%20carers,9.3%25%20of%20all%20males). |

[6] | Fu W , Li J , Fang F , Zhao D , Hao W , Li S Subjective burdens among informal caregivers of critically ill patients: a cross-sectional study in rural Shandong, China. BMC Palliative Care. (2021) ;20: (1):1–11. |

[7] | Lynch K Care and Capitalism. Newark, UNITED KINGDOM: Polity Press; 2022. |

[8] | Goldberg A , Rickler KS The role of family caregivers for people with chronic illness. Rhode Island Medical Journal. (2011) ;94: (2):41. |

[9] | Gaugler JE , Pestka DL , Davila H , Sales R , Owen G , Baumgartner SA , et al. The complexities of family caregiving at work: A mixed-methods study. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. (2018) ;87: (4):347–76. |

[10] | Boumans NPG , Dorant E Double-duty caregivers: healthcare professionals juggling employment and informal caregiving. A survey on personal health and work experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing. (2014) ;70: (7):1604–15. |

[11] | Halinski M , Duxbury L , Higgins C Working While Caring for Mom, Dad, and Junior Too: Exploring the Impact of Employees’ Caregiving Situation on Demands, Control, and Perceived Stress. Journal of Family Issues. (2018) ;39: (12):3248–75. |

[12] | Spann A , Vicente J , Allard C , Hawley M , Spreeuwenberg M , de Witte L Challenges of combining work and unpaid care, and solutions: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community. (2020) ;28: (3):699–715. |

[13] | Wieczorek E , Evers S , Kocot E , Sowada C , Pavlova M Assessing Policy Challenges and Strategies Supporting Informal Caregivers in the European Union. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. (2022) ;34: (1):145–60. |

[14] | Ireland FC State of Caring Ireland2022 [cited 2023 August 24th ]. Available from: https://familycarers.ie/media/2545/family-carers-ireland-state-of-caring-2022.pdf. |

[15] | Evans KL , Millsteed J , Richmond JE , Falkmer M , Falkmer T , Girdler SJ Working sandwich generation women utilize strategies within and between roles to achieve role balance. PloS One. (2016) ;11: (6):e0157469–e. |

[16] | Kossek EE , Thompson RJ , Lawson KM , Bodner T , Perrigino MB , Hammer LB , et al. Caring for the Elderly at Work and Home: Can a Randomized Organizational Intervention Improve Psychological Health?. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. (2019) ;24: (1):36–54. |

[17] | Depasquale N , Davis KD , Zarit SH , Moen P , Hammer LB , Almeida DM Combining formal and informal caregiving roles: The psychosocial implications of double- and triple-duty care. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. (2016) ;71: (2):201–11. |

[18] | Government of Ireland. New workers’ rights, including domestic violence leave, introduced under the Work Life Balance Bill passed by the Oireachtas Ireland: Government of Ireland; 2023 [cited 2023 August 25th]. Available from: https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/feae1-new-workers-rights-including-domestic-violence-leave-introduced-under-the-work-life-balance-bill-passed-by-the-oireachtas/. |

[19] | Citizen’s Information. Carer’s leave: Citizen’s Advice; 2022 [cited 2023 August 25]. Available from: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/employment/employment-rights-and-conditions/leave-and-holidays/carers-leave/. |

[20] | Government of Ireland. Carer’s Allowance 2019 [cited 2023 Aug 28th]. Available from: https://www.gov.ie/en/service/2432ba-carers-allowance/. |

[21] | Government of Ireland. Carer’s Benefit 2019 [cited 2023 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.gov.ie/en/service/455c16-carers-benefit/. |

[22] | Citizen’s Information. Domiciliary Care Allowance 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/social-welfare/social-welfare-payments/disability-and-illness/domiciliary-care-allowance/.. |

[23] | Government of Ireland. Carer’s Support Grant 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.gov.ie/en/service/16220307-carers-support-grant/. |