An epidemiological study of mental health problems related to climate change: A procedural framework for mental health system workers

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The Arab region has witnessed different biological hazards, including cholera, yellow fever, and the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, changes in rainfall and increased vegetation cover led to locust outbreaks in Tunisia, Libya, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia. This problem still exists and affects more than 20 countries and concerns indicate food shortages and food insecurity for more than 20 million people.

OBJECTIVE:

This study aimed to detect mental health problems related to climate change in the Arab world.

METHODS:

A cross-sectional descriptive survey was applied to determine the prevalence of mental health problems related to climate change (MHPCC). A random sample consisted of 1080 participants (523 male and 557 female), residents in 18 Arab countries; their ages ranged from 25 to 60 years. The Mental Health Problems related to Climate Change Questionnaire (MHPCCQ) was completed online.

RESULTS:

The results indicated average levels of MHPCC prevalence. The results also revealed no significant statistical differences in the MHPCC due to gender, educational class, and marital status except in climate anxiety; there were statistical differences in favor of married subgroup individuals. At the same time, there are statistically significant differences in the MHPCC due to the residing country variable in favor of Syria, Yemen, Algeria, Libya, and Oman regarding fears, anxiety, alienation, and somatic symptoms. In addition, Tunisia, Bahrain, Sudan, and Iraq were higher in climate depression than the other countries.

CONCLUSION:

The findings shed light on the prevalence of MHPCC in the Arab world and oblige mental health system workers, including policymakers, mental health providers, and departments of psychology in Arab universities, to take urgent action to assess and develop the system for mental health to manage the risks of extreme climate change on the human mental health.

1Background

1.1The problem of climate change

The world has faced unprecedented climatic changes over the past 50 years, resulting in significant human and economic losses. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicated that global warming is approximately (0.08) degrees and is expected to increase in the coming years. This global warming is amplified by physical systems such as high sea-levels, glaciers, significant drops in the extent of sea ice thickness in the Arctic, and changes in precipitation patterns. Global warming also affects biological systems; as a result, growing international concern about the current growth rate of greenhouse gas emissions and observed climate effects suggests that climate change occurs more strongly than the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [36]. Therefore, studies on the impact of climate change on mental health were rapidly developing and considered a recent field [35, 69].

By surveying the studies conducted on the impact of climate on human mental health, we found many studies on the effects of climate change on human mental health [4, 24, 35, 40, 58]. Hwong et al. [35] noted that most studies about the effects of climate change on mental health were conducted in high-income countries, especially the United States of America (USA) and Australia. The results of these studies cannot be generalized to low-income countries. At the same time, no studies were conducted on low-lying countries to clarify the prevalence of psychological problems associated with climate change.

1.2Climate change in the Arab world

The Regional Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction in the Arab Region of 2021 [48] declared Arab countries at risk. In 2018, Hurricane Sagar landed in Somalia, causing significant economic losses, damaging crops and livestock, and killing thousands of people. 2019 saw a stronger storm recorded in the last 12 years with Hurricane Cyar. The waves have disrupted the Emirates’ road network, underscoring the need to address emergency damage and malfunctions in infrastructure systems. Bahrain and Comoros are small islands and developing countries and face significant challenges related to disaster risk management and reduction as climate change, exceptionally high sea-levels, and drought threatens their residents. For the past five years, the region has suffered from a drought that affected climate variability on its unit frequency, leading to significant losses among rural poor in Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Morocco. In addition to forest fires posing a threat, Lebanon has recorded more than 1,200 forests since 1981.

Consequently, there have been instances of the massive destruction caused by earthquakes in Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon over the past millennia. In the last 60 years, medium and large earthquakes have also caused several urban areas in Algeria, Egypt, and Morocco (Agadir earthquake in Morocco in 1960, an earthquake in Egypt in 1992). The Arab region is also at risk from biological hazards such as earthquakes, landslides, and tsunamis, as more than 30% of the Arab population lives in medium and high-risk areas. Arab countries have also faced various biological threats, including cholera, yellow fever, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, changes in rainfall and increased vegetation have led to locust outbreaks in Tunisia, Libya, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia; this problem remains a list, affecting more than 20 countries, indicating food shortages and insecurity for more than 20 million people.

For example, Algeria is one of the 24 hot spots and most vulnerable to climate change due to its location in the Mediterranean. It has been affected by many extreme weather phenomena such as floods, high temperatures, drought, desertification, forest fires, and others. It has caused human losses, many casualties, and significant damage to infrastructure in recent years. The State of Morocco is suffering from severe climatic changes such as drought, changes in the amount of rain, floods, and others, which had severe repercussions, and led to the deterioration of the ecosystem, the increase of epidemic diseases, environmental and food insecurity and the forced migration of populations from some affected areas [7].

Iraq is also ranked fifth among the countries most affected by climate changes, high temperatures, severe drought, declining rainfall, desertification and salinization, and the increase in the spread of dust storms and others, which have led to severe environmental, security, political, and economic repercussions on Iraq that will continue for years to come. Likewise, Yemen is one of the countries most affected by frequent climatic changes, including floods, droughts, and unconventional temperature changes, which have caused severe threats to water, food security, and livelihoods. Lebanon has faced significant climatic changes in temperature, rainfall, drought, and forest fires, affecting the agricultural sector, the economy, and water wealth. In recent decades, Egypt has also faced climatic changes that have had severe repercussions for many sectors, most notably the agriculture and tourism sectors, which have led to enormous impacts on the Egyptian economy and damaged infrastructure, such as sudden changes in temperature, the quantity, and quality of rain, drought, desertification, earthquakes, sea-level rise and the possibility of the disappearance of some coastal cities and other climatic changes [7].

1.3Physical and mental health issues related to climate change

Studies about the effects of climate change on physical health [27, 61, 65] showed a direct health impact of climate, including death and infection. Extreme weather phenomena such as increased maximum temperatures, the spread of infectious diseases, air quality and respiratory diseases, and changes in food and water quality, climate change impacts are increasingly affecting low-income and marginalized people in societies or living conditions from the war in tents and other cruel conditions [11, 27].

Therefore, a wide range of studies continues to enhance knowledge on the impact of climate change on physical health, including, for example, increasing infectious diseases, water, and food increasing chronic and severe respiratory cases, including asthma and sensitivity, and the deaths associated with marine and extreme weather [41]. In 2017, Lancet published the first report on climate change and health and included a recommendation for further research on the effects of climate change on health, particularly mental health.

Human mental health has environmental, social, economic, and political determinants. Literature indicates the impact of climate change on human health, so climate change causes psychological stress and anxiety for human beings today [5, 18, 36,70].

In 2016, Lancet’s report about sustainable development and global mental health emphasized that mental health is “more health conditions for man to neglect” and launched the term “failure of humanity”. The World Health Organization (WHO) [66] defined mental health as physical, mental, psychological, and social, not just the absence of disease or disability. For this, Hayes et al. [32] referred that mental health does not indicate disease, problems, and mental disorders but mental health, resilience, and psychological well-being (PWB). Watts et al. [61] mentioned a continuous expansion and rapid health and climate change research.

1.4Direct and indirect effects of climate change on mental health

Berry, Bowen and Kjellstrom [10] developed a conceptual framework for climate change and mental health. The risk of climate change is divided into three categories: acute (floods, hurricanes, etc.), semi-sharp hazards (bottled drought), and chronic risks (sea-level rise and temperatures). Eventually, the risks associated with climate change led to various direct and indirect psychological and social consequences that are now sponsoring and affecting the most marginalized community. Executive climate change’s direct psychosocial and social consequences include floods, hurricanes, forest fires, and severe free waves. The consequences of indirect climate change on mental health are also spoken through social and economic factors and environmental disorders (famine, civil conflict, displacement, and migration) associated with climate change.

Extreme climatic phenomena lead to psychological and mental results associated with loss and displacement [13]. The results of previous studies [4, 8, 20, 24, 61] revealed that public fears, post-traumatic disorder, and psychological stress have emerged after severe, cruel weather situations. Willox et al. [63] showed that post-traumatic disorder is the most common response to individuals after a disaster. The symptoms of this disorder are recovered once the conditions are restored from security, safety, and community support. Whereas, Willox et al. [63] pointed out some individuals will continue suffering from post-traumatic disorder and several other mental health problems such as sorrow or complex sadness, depression, anxiety disorders, and drug and alcohol abuse.

As a result, climate change leads to various psychological and social consequences. In the same context, Hayes et al. [32] mentioned that climate change’s overall psychological and social impacts are linked to long-term psychological stress resulting from climate change on current and future mental health. Climate change has three main effects on mental health: first, climate change directly increases mental health problems’ spread and severity and significantly impacts mental health systems. Second, weak societies began with disorders of social, economic, and environmental determinants that promote mental health. Finally, there is an emerging understanding of the methods through which global climate change may cause fears and anxiety about the future.

In the same way, Doherty and Clayton [23] said that the psychological effects of global climate change, there are three types of effects: direct effects (for example, acute or painful effects of extreme weather events and changing environment), indirect effects (e.g., threats on mental health based on the observation of the impact, anxiety, uncertainty about future risks), social monuments (e.g., social and chronic social effects of heat, drought or desertification, migration, climate disputes, and after disaster adjustment).

Concerning the direct effects of climate change on mental health, many studies were conducted, including studies on the impact of high temperatures on mental health; previous studies [12, 59] found that extreme humidity increases the hospital’s entry due to mood and behavioral disorders including schizophrenia, mania, and neurological disorders. Other studies [21, 22, 46, 61] found that heat-related mental illness often occurs in persons with poor thermal regulation, any pre-existing problems and psychosocial diseases, and those with drug abuseproblems.

As for the impact of drought on mental health, previous studies [56, 67] showed that drought increases tension and social isolation, protects social relations, and suicide rates in individuals living in rural areas are affected by drought or desertification in Australia. Links [37] also pointed out that climate change will likely tear and communicate community networks by increasing the displacement of coercive societies and migration and economics.

Albrecht [3], McMichael [40], and Ramsay and Manderson [49] refereed those overall threats to the changing climate led to despair. The National Academies of Sciences [42] and Stone and Allen [52] expected that cruel climatic events such as high surface levels, domestic economies, scarcity of resources, and the associated conflict due to climate change cause millions of people around the world during the next century. Also, as mentioned in previous studies [1, 16, 44, 61, 63–65], the growing climatic changes, such as high surface and accidental drought, can change the landscape and water, agricultural conditions, land use, housing, weaken the infrastructure, lead to financial and relationships pressures, and increase the risk of violence and aggression.

Migration causes a loss of sense of opportunity and loss of place, which leads to devastating psychological effects on the mental health of the displaced. In addition, displacement and migration due to extremist climatic conditions directly impact human mental health. In this context, previous studies [47, 52] showed that displacement and migration raised psychological whether the cause of migration is an escape from violence and wars, destroying livelihoods, extreme poverty, and natural disasters.

Forestry, floods, and hurricanes are the other environmental disasters resulting from climate change, and many studies were conducted on their effects on mental health [9] found that the most vulnerable societies to forest fires increase the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, psychological distress, and depression associated with fires. The study conducted by Tunstall et al. [54] also revealed high mental health problems among flood-affected populations. Previous studies [22, 29] confirmed the spread of anxiety and mood disorders among survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Dodgen et al. [22] found high levels of anxiety and suicide after Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Also, previous studies [16, 19] showed an increase in depression, domestic violence, suicide attempts, and post-traumatic trouble in the USA after being subjected to Katrina. Coyle and van Susteren [19] also explained high abuse rates for children in the wake of Cyclone Florida, USA.

In addition to these direct effects of climate change on mental health, the indirect results of climate change can also occur on mental health through damage to physical and social infrastructure and its influences on physical health, food, and water. In a systematic review, Vins et al. [55] noted that the economic impact of land degradation is the most prominent causal path connecting drought and mental health. It is also suggested [11, 25] that insecurity in the income associated with drought increases the risk of suicide among farmers. OBrien et al. [45] and Vins et al. [55] found drought or desertification indirectly affects mental health. Long-term food and water supply can later affect land workers’ economic and psychological well-being, often affecting those living in rural and remote communities. Also, the study by [31] found that long-term drought leads to conflict and forced migration, resulting in post-traumatic disorder, anxiety, andtrauma.

1.5The need for climate psychology

As psychology is concerned with studying human behavior in both crises and natural conditions, climate psychology is one of the modern branches of psychology that originated during the world’s many catastrophic climate changes. Hogget and Robertson [33] referred to climate psychology, aims to understand further the psychological processes that occur in response to climate change, loss of biological diversity and their consequences, and search for creative communication with individuals on climate change; contribute to the creation of personal, societal, cultural, political changes; support policymakers to make effective change; enhance the ability to adapt to the devastating effects of climate change now and future and take cognitive and behavioral procedures based on scientific evidence to address the escalating threat to climate change.

Because of the increasing exposure of society to climate change risk, there was greater interest in understanding the psychological processes behind the resistance to appropriate action, particularly the climate change phenomenon. The assets of climate psychology returned the psychologist “Harold Sears” from the amazing factors that affect people and isolate them from things in nature. Ecological psychology also severely affected climate psychology and emphasized the principle of people’s relationships in the natural world. More recently, the literary base for the same climate scientists began to focus on the intense emotions associated with climate change [7, 33, 43].

Thus, everyone understood that climate change’s global effects threaten human health. The WHO [67, 68] report refers to an increase of 250,000 excess deaths annually between 2030 and 2050 due to the effects of climate change. It is well known for climate change. Deaths associated with heat rise increased infectious diseases such as dengue and malaria fever, increased respiratory diseases, and deaths from extreme weather phenomena. The least known effects of climate change are mental health. Through the above, we can say that last century, studies did not directly discuss the impact of climate change on human mental health. Recently, studies have emerged to detect climate change on mental health.

As long as the reality of the Arab world and what is happening in natural disasters - as part of the World Climate System - human and economic losses incurred by some Arab countries due to extremist climatic changes, as well as the absence of disaster risk management plans and weak mental health systems, as well as the lack of epidemiological studies on the effects of climate change on the mental health. Based on the current literature, we can test the hypothesis that climate change results in psychological problems. Therefore, this study seeks to determine the prevalence of mental health symptoms related to climate change in the Arab world and to detect the differences in mental health symptoms associated with climate change due to gender, educational class, marital status, and residing country [7].

2Methods

2.1Design and participants

This quantitative study featured a cross-sectional survey descriptive to determine the prevalence of mental health problems related to climate change in Arab countries and a comparative design to detect the differences in the mental health problems related to climate change due to demographic variables. The online Raosoft sample size calculation methodology [50] was used to calculate the sample size. According to this method a minimum of 643 participants is needed; given that the margin of error alpha (α) = 0.01, the confidence level is = 99%, total population = 430,753,333, and the response of distribution = 50%. The number of responses to the online questionnaire was 1080 replies.

2.2Data collection instrument

The Mental Health Problems related to Climate Change Questionnaire (MHPCCQ) was developed online using Google Forms. The online link was sent to many individuals in several Arab countries. This questionnaire consists of 40 items divided into eight sub-questionnaires: climate fears, climate anxiety, climate depression, climate obsessive-compulsive, climate grief, climate anger, climate alienation, and climate somatic symptoms. Answers are given using a 5-point Likert questionnaire (never = 1 to very much = 5).

2.3Data analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS Statistics, version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics such as percentage, frequencies, mean and standard deviation were calculated for sociodemographic variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test examined the normality of the MHPCCQ subscales. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to calculate the correlations between scale items and subscales. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were used to verify the internal consistency of the Mental Health Problems related to Climate Change Questionnaire (MHPCCQ). Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was used to examine the factor structure of MHPCCQ. A one-sample t-test, independent samples T-test, and one-way ANOVA between-groups comparisons were used to detect the differences, and the p < 0.05 statistical significance level was approved. A Scheffe test was used to identify the direction of the differences because the number of individuals in the subgroups is not equal, and compound comparisons are what the researcher wants to make. Also, the Scheffe test is one of the most flexible and statistically powerful ways to test the post-hoc multiple comparisons.

3Results

3.1Questionnaire validity

Before conducting the EFA analysis on the MHPCCQ, Bartlett’s test of Sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measurement of sampling adequacy (KMO) were conducted to verify that the sample was adequate for conducting this analysis. The Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was significant (χ2 = 32341.106, df = 780, p < .001) and the KMO value was acceptable at 0.907. MHPCCQ item component loads ranged from 0.358 to 0.7279. The EFA results suggest that MHPCCQ consisted of the 8-dimensional construct (Table 1).

Table 1

Saturations of the items of the MHPCCQ scale by factors after the rotated component matrix

| Items | Fears | Anxiety | Depression | Obsessive-compulsive | Grief | Anger | Alienation | Somatic symptoms |

| 1 | 0.659 | |||||||

| 2 | 0.812 | |||||||

| 3 | 0.637 | |||||||

| 4 | 0.727 | |||||||

| 5 | 0.665 | |||||||

| 6 | 0.429 | |||||||

| 7 | 0.522 | |||||||

| 8 | 0.619 | |||||||

| 9 | 0.358 | |||||||

| 10 | 0.384 | |||||||

| 11 | 0.597 | |||||||

| 12 | 0.406 | |||||||

| 13 | 0.649 | |||||||

| 14 | 0.512 | |||||||

| 15 | 0.658 | |||||||

| 16 | 0.498 | |||||||

| 17 | 0.455 | |||||||

| 18 | 0.479 | |||||||

| 19 | 0.592 | |||||||

| 20 | 0.554 | |||||||

| 21 | 0.605 | |||||||

| 22 | 0.710 | |||||||

| 23 | 0.660 | |||||||

| 24 | 0.701 | |||||||

| 25 | 0.596 | |||||||

| 26 | 0.636 | |||||||

| 27 | 0.524 | |||||||

| 28 | 0.510 | |||||||

| 29 | 0.611 | |||||||

| 30 | 0.637 | |||||||

| 31 | 0.630 | |||||||

| 32 | 0.583 | |||||||

| 33 | 0.611 | |||||||

| 34 | 0.643 | |||||||

| 35 | 0.504 | |||||||

| 36 | 0.591 | |||||||

| 37 | 0.692 | |||||||

| 38 | 0.504 | |||||||

| 39 | 0.542 | |||||||

| 40 | 0.670 |

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

The MHPCCQ also exhibits good reliability since the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the eight subscales were (0.90, 0.870, 0.819, 0.776, 0.858, 0.730, 0.720, 0.802, respectively) high. Also, the correlations between the items and the total score of the subscales were high, ranging between 0.493 to 0.846 (Table 2).

Table 2

Correlations of the MHPCCQ items

| Subscales | Items | Correlations | Subscales | Items | Correlations |

| Fears | 1 | 0.833** | Obsessive-compulsive | 14 | 0.768** |

| 3 | 0.759** | 17 | 0.756** | ||

| 4 | 0.846** | 22 | 0.802** | ||

| 7 | 0755** | 23 | 0.769** | ||

| 11 | 0.754** | Grief | 9 | 0.795** | |

| 19 | 0.674** | 16 | 0.811** | ||

| 25 | 0.7147** | 30 | 0.794** | ||

| 26 | 0.792** | 31 | 0.774** | ||

| Anxiety | 20 | 0.807** | 35 | 0.817** | |

| 21 | 0.811** | Anger | 8 | 0.8210** | |

| 27 | 0.780** | 15 | 0.493** | ||

| 28 | 0.824** | 24 | 0.798** | ||

| 32 | 0.793** | Alienation | 6 | 0.799** | |

| 37 | 0.658** | 12 | 0.827** | ||

| Depression | 2 | 0.736** | 33 | 0.776** | |

| 5 | 0.763** | Somatic symptoms | 13 | 0.774** | |

| 10 | 0.658** | 18 | 0.806** | ||

| 34 | 0.700** | 29 | 0.698** | ||

| 36 | 0.745** | 38 | 0.713** | ||

| 40 | 0.753** | 39 | 0.743** |

**Significant at 0.001 level.

3.2Sample descriptive

The sample was constituted by 1080 subjects (n = 557, 51.57% female and n = 523, 48.43% male), mostly graduated (n = 207, 19.17% pre-university; n = 644, 59.63% graduate; and n = 229, 59.53% postgraduate) and married (n = 499, 46.20% married; n = 310, 28.70% widower; n = 140, 12.96% divorced; and n = 131, 12.13% single) coming from 18 Arab countries (Table 3).

Table 3

Frequency table according to the sample residing country

| Country | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

| Saudi Arabia | 51 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.7 |

| Egypt | 99 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 13.9 |

| Sudan | 52 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 18.7 |

| Syria | 35 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 21.9 |

| Iraq | 51 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 26.7 |

| Kuwait | 50 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 31.3 |

| Yemen | 82 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 38.9 |

| Lebanon | 82 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 46.5 |

| Jordan | 58 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 51.9 |

| Oman | 94 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 60.6 |

| Tunisia | 25 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 62.9 |

| Algeria | 62 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 68.6 |

| Libya | 47 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 73.0 |

| Palestine | 61 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 78.6 |

| Mauritania | 50 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 83.2 |

| UAE | 60 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 88.8 |

| Qatar | 61 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 94.4 |

| Bahrain | 60 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 100.0 |

| Total | 1080 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

3.3MHPCCQ scores

To determine the level of psychological problems related to climate change, the individuals were classified into three levels of MHPCC, as follows: low level from (1 to 2.33), medium level from (2.34 to 3.66), and high level from (3.67 to 5). In the same way, the individuals were classified into three levels of subscales (for example, climate fears: low level from (8–18.16); medium from (18.67 to 29.33); and high level from (29.34 to 40). The results in Table 4 indicated an average level of mental health associated with climate change in all MHPCCQ subscales and their items except item number 40.

Table 4

Means and standard deviation of the MHPCCQ items and their level

| Items | M | St. deviation | Level | Items | M | St. deviation | Level |

| 1 | 3.418 | 1.536 | Average | 21 | 3.238 | 1.148 | Average |

| 2 | 3.584 | 1.070 | Average | 22 | 3.267 | 1.141 | Average |

| 3 | 3.517 | 1.168 | Average | 23 | 2.956 | 1.271 | Average |

| 4 | 3.277 | 1.292 | Average | 24 | 3.217 | 1.136 | Average |

| 5 | 3.572 | 1.082 | Average | 25 | 3.239 | 1.126 | Average |

| 6 | 3.349 | 1.153 | Average | 26 | 3.175 | 1.268 | Average |

| 7 | 3.287 | 1.210 | Average | 27 | 3.276 | 1.164 | Average |

| 8 | 3.322 | 1.239 | Average | 28 | 3.247 | 1.128 | Average |

| 9 | 3.221 | 1.218 | Average | 29 | 3.146 | 1.099 | Average |

| 10 | 3.289 | 1.135 | Average | 30 | 3.133 | 1.226 | Average |

| 11 | 3.284 | 1.289 | Average | 31 | 3.279 | 1.189 | Average |

| 12 | 3.242 | 1.288 | Average | 32 | 3.033 | 1.305 | Average |

| 13 | 3.189 | 1.361 | Average | 33 | 3.259 | 1.191 | Average |

| 14 | 3.100 | 1.293 | Average | 34 | 3.529 | 1.156 | Average |

| 15 | 3.282 | 1.174 | Average | 35 | 3.256 | 1.265 | Average |

| 16 | 3.165 | 1.256 | Average | 36 | 3.559 | 1.053 | Average |

| 17 | 3.133 | 1.186 | Average | 37 | 3.228 | 1.086 | Average |

| 18 | 3.222 | 1.265 | Average | 38 | 3.323 | 1.119 | Average |

| 19 | 3.113 | 1.196 | Average | 39 | 3.319 | 1.183 | Average |

| 20 | 3.168 | 1.232 | Average | 40 | 3.813 | 1.175 | High |

| Climate fears | 26.311 | 7.762 | Average | Climate grief | 16.054 | 4.916 | Average |

| Climate anxiety | 19.191 | 5.513 | Average | Climate anger | 9.821 | 2.862 | Average |

| Climate depression | 21.347 | 4.840 | Average | Climate alienation | 9.850 | 2.911 | Average |

| Climate obsessive-compulsive | 12.456 | 3.786 | Average | Climate somatic symptoms | 16.201 | 4.517 | Average |

3.4Differences in MHPCCQ due to demographic variables

The statistical analysis findings of differences in MHPCC due to gender, educational class, marital status, and the residing country are asfollows:

3.4.1No difference in MHPCC due to gender

The results of the t-test shown in Table 5 indicated no significant statistical differences between males and females in MHPCC: climate fears (t = 0.318, p > 0.05), climate anxiety (t = 0.543, p > 0.05), climate depression (t = 1.803, p > 0.05), climate obsessive-compulsive (t = 1.491, p > 0.05), climate grief (t = 1.009, p > 0.05), climate anger (t = 0.435, p > 0.05), climate alienation (t = 0.116, p > 0.05), and climate somatic symptoms (t = 0.012, p > 0.05).

Table 5

Differences in mental MHPCC due to gender (male/female) variable

| Variables | Gender | N | Mean | Std. deviation | t-test | Sig. (2-tailed) |

| Climate fears | Male | 523 | 26.2333 | 8.08522 | 0.318 | 0.750 |

| Female | 557 | 26.3842 | 7.45198 | |||

| Climate anxiety | Male | 523 | 19.2849 | 5.66811 | 0.543 | 0.587 |

| Female | 557 | 19.1023 | 5.36696 | |||

| Climate depression | Male | 523 | 21.6214 | 4.94046 | 1.803 | 0.071 |

| Female | 557 | 21.0898 | 4.73421 | |||

| Climate obsessive-compulsive | Male | 523 | 12.6329 | 3.83059 | 1.491 | 0.136 |

| Female | 557 | 12.2890 | 3.74033 | |||

| Climate grief | Male | 523 | 16.2103 | 4.91983 | 1.009 | 0.313 |

| Female | 557 | 15.9084 | 4.91224 | |||

| Climate anger | Male | 523 | 9.8604 | 2.85163 | 0.435 | 0.664 |

| Female | 557 | 9.7846 | 2.87327 | |||

| Climate alienation | Male | 523 | 9.8394 | 2.87028 | 0.116 | 0.908 |

| Female | 557 | 9.8600 | 2.95198 | |||

| Climate somatic symptoms | Male | 523 | 16.2027 | 4.60811 | 0.012 | 0.990 |

| Female | 557 | 16.1993 | 4.43475 |

3.4.2No difference in MHPCC due to education class

One-way ANOVA was calculated to detect the differences between educational class subgroups. The findings in Tables 6 and 7 indicated no significant statistical differences due to educational class in mental health problems related to climate change: climate fears (F = 1.947, p > .05), climate anxiety (F = 0.497, p < 0.05), climate depression (F = 0.770, p > 0.05), climate obsessive-compulsive (F = 0.145, p > 0.05), climate grief (F = 0.468, p > 0.05), climate anger (F = 0.270, p > 0.05), climate alienation (F = 0.233, p > 0.05), and climate somatic symptoms (F = 0.646, p > 0.05).

Table 6

Differences in MHPCC due to educational class variable

| Variables | Groups | N | Mean | Std. deviation |

| Climate fears | Pre-university | 207 | 26.295 | 7.367 |

| Graduate | 644 | 26.006 | 7.889 | |

| Postgraduate | 229 | 27.183 | 7.7165 | |

| Total | 1080 | 26.311 | 7.762 | |

| Climate anxiety | Pre-university | 207 | 19.237 | 5.159 |

| Graduate | 644 | 19.069 | 5.525 | |

| Postgraduate | 229 | 19.489 | 5.793 | |

| Total | 1080 | 19.191 | 5.513 | |

| Climate depression | Pre-university | 207 | 20.985 | 4.644 |

| Graduate | 644 | 21.401 | 4.835 | |

| Postgraduate | 229 | 21.524 | 5.028 | |

| Total | 1080 | 21.347 | 4.840 | |

| Climate obsessive-compulsive | Pre-university | 207 | 12.343 | 3.735 |

| Graduate | 644 | 12.502 | 3.763 | |

| Postgraduate | 229 | 12.428 | 3.909 | |

| Total | 1080 | 12.456 | 3.786 | |

| Climate grief | Pre-university | 207 | 16.270 | 4.879 |

| Graduate | 644 | 15.935 | 4.871 | |

| Postgraduate | 229 | 16.196 | 5.084 | |

| Total | 1080 | 16.055 | 4.915 | |

| Climate anger | Pre-university | 207 | 9.719 | 3.100 |

| Graduate | 644 | 9.818 | 2.800 | |

| Postgraduate | 229 | 9.921 | 2.818 | |

| Total | 1080 | 9.821 | 2.862 | |

| Climate alienation | Pre-university | 207 | 9.739 | 2.851 |

| Graduate | 644 | 9.894 | 2.906 | |

| Postgraduate | 229 | 9.825 | 2.990 | |

| Total | 1080 | 9.850 | 2.911 | |

| Climate somatic symptoms | Pre-university | 207 | 16.000 | 4.466 |

| Graduate | 644 | 17.149 | 4.251 | |

| Postgraduate | 229 | 17.511 | 4.399 | |

| Total | 1080 | 17.243 | 4.257 |

Table 7

Results of group differences in MHPCC due to an educational class variable

| Variables | Groups | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. |

| Climate fears | Between groups | 234.170 | 2 | 117.085 | 1.947 | .143 |

| Within groups | 64771.296 | 1077 | 60.140 | |||

| Total | 65005.467 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate anxiety | Between groups | 30.228 | 2 | 15.114 | .497 | .609 |

| Within groups | 32764.479 | 1077 | 30.422 | |||

| Total | 32794.707 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate depression | Between groups | 36.077 | 2 | 18.039 | .770 | .463 |

| Within groups | 25242.714 | 1077 | 23.438 | |||

| Total | 25278.792 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate obsessive-compulsive | Between groups | 4.160 | 2 | 2.080 | .145 | .865 |

| Within groups | 15465.707 | 1077 | 14.360 | |||

| Total | 15469.867 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate grief | Between groups | 23.509 | 2 | 11.754 | .486 | .615 |

| Within groups | 26052.268 | 1077 | 24.190 | |||

| Total | 26075.777 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate anger | Between groups | 4.432 | 2 | 2.216 | .270 | .763 |

| Within groups | 8832.078 | 1077 | 8.201 | |||

| Total | 8836.510 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate alienation | Between groups | 3.954 | 2 | 1.977 | .233 | .792 |

| Within groups | 9141.746 | 1077 | 8.488 | |||

| Total | 9145.700 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate somatic symptoms | Between groups | 26.393 | 2 | 13.196 | .646 | .524 |

| Within groups | 21993.006 | 1077 | 20.421 | |||

| Total | 22019.399 | 1079 |

3.4.3No differences in MHPCC due to marital status

One-way ANOVA was calculated to detect the differences between marital status subgroups. Tables 8 and 9 indicated no significant statistical differences between marital status subgroups in MHPCC except for climate anxiety. To determine the direction of these differences, a Scheffe test was applied. The results showed the differences in climate anxiety favor the married subgroup compared to the widower subgroup (MD = 1.165). The results as follow: climate fears (F = 1.307, p > 0.05), climate anxiety (F = 3.008, p < 0.05), climate depression (F = 0.737, p > 0.05), climate obsessive-compulsive (F = 0.342, p > 0.05), climate grief (F = 0.714, p > .05), climate anger (F = 1.207, p > 0.05), climate alienation (F = 0.183, p > 0.05), and climate somatic symptoms (F = 0.821, p > 0.05).

Table 8

Differences in MHPCC due to marital status variable

| Variables | Groups | N | Mean | Std. deviation |

| Climate fears | Single | 131 | 26.969 | 7.092 |

| Married | 499 | 26.559 | 7.744 | |

| Widower | 310 | 25.619 | 8.092 | |

| Divorced | 140 | 26.343 | 7.650 | |

| Total | 1080 | 26.311 | 7.762 | |

| Climate anxiety | Single | 131 | 19.488 | 5.208 |

| Married | 499 | 19.597 | 5.470 | |

| Widower | 310 | 18.432 | 5.636 | |

| Divorced | 140 | 19.143 | 5.548 | |

| Total | 1080 | 19.191 | 5.513 | |

| Climate depression | Single | 131 | 21.343 | 4.596 |

| Married | 499 | 21.136 | 5.036 | |

| Widower | 310 | 21.513 | 4.735 | |

| Divorced | 140 | 21.736 | 4.588 | |

| Total | 1080 | 21.347 | 4.840 | |

| Climate obsessive-compulsive | Single | 131 | 12.351 | 3.495 |

| Married | 499 | 12.577 | 3.777 | |

| Widower | 310 | 12.319 | 3.769 | |

| Divorced | 140 | 12.421 | 4.131 | |

| Total | 1080 | 12.456 | 3.786 | |

| Climate grief | Single | 131 | 16.030 | 4.633 |

| Married | 499 | 16.252 | 4.865 | |

| Widower | 310 | 15.952 | 5.035 | |

| Divorced | 140 | 15.600 | 5.097 | |

| Total | 1080 | 16.055 | 4.916 | |

| Climate anger | Single | 131 | 9.702 | 2.747 |

| Married | 499 | 9.990 | 2.905 | |

| Widower | 310 | 9.613 | 2.845 | |

| Divorced | 140 | 9.792 | 2.839 | |

| Total | 1080 | 9.821 | 2.862 | |

| Climate alienation | Single | 131 | 10.015 | 2.820 |

| Married | 499 | 9.804 | 2.896 | |

| Widower | 310 | 9.852 | 2.902 | |

| Divorced | 140 | 9.857 | 3.089 | |

| Total | 1080 | 9.850 | 2.911 | |

| Climate somatic symptoms | Single | 131 | 16.305 | 4.362 |

| Married | 499 | 16.375 | 4.386 | |

| Widower | 310 | 15.871 | 4.711 | |

| Divorced | 140 | 16.214 | 4.690 | |

| Total | 1080 | 16.201 | 4.517 |

Table 9

Results of group differences in MHPCC due to the marital status variable

| Variables | Groups | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. |

| Climate fears | Between groups | 235.956 | 3 | 78.652 | 1.307 | .271 |

| Within groups | 64769.511 | 1076 | 60.195 | |||

| Total | 65005.467 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate anxiety | Between groups | 272.718 | 3 | 90.906 | 3.008 | .029 |

| Within groups | 32521.989 | 1076 | 30.225 | |||

| Total | 32794.707 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate depression | Between groups | 51.846 | 3 | 17.282 | .737 | .530 |

| Within groups | 25226.945 | 1076 | 23.445 | |||

| Total | 25278.792 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate obsessive-compulsive | Between groups | 14.720 | 3 | 4.907 | .342 | .795 |

| Within groups | 15455.146 | 1076 | 14.364 | |||

| Total | 15469.867 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate grief | Between groups | 51.840 | 3 | 17.280 | .714 | .543 |

| Within groups | 26023.936 | 1076 | 24.186 | |||

| Total | 26075.777 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate anger | Between groups | 29.630 | 3 | 9.877 | 1.207 | .306 |

| Within groups | 8806.880 | 1076 | 8.185 | |||

| Total | 8836.510 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate alienation | Between groups | 4.660 | 3 | 1.553 | .183 | .908 |

| Within groups | 9141.040 | 1076 | 8.495 | |||

| Total | 9145.700 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate somatic symptoms | Between groups | 50.281 | 3 | 16.760 | .821 | .482 |

| Within groups | 21969.118 | 1076 | 20.417 | |||

| Total | 22019.399 | 1079 |

3.4.4Differences in MHPCC due to residing country

One-way ANOVA was calculated to detect the differences between country-living subgroups. The results shown in Tables 10, 11 indicated that there are significant statistical differences between residing country subgroups in MHPCC related to climate changes: climate fears (F = 15.098, p < .05), climate anxiety (F = 13.494, p < .05), climate depression (F = 21.414, p < .05), climate obsessive-compulsive (F = 7.104, p < .05), climate grief (F = 11.911, p < .05), climate anger (F = 10.105, p < .05), climate alienation (F = 11.413, p < .05), and climate somatic symptoms (F = 12.675, p < .05).

Table 10

Differences in MHPCC due to residing country variable

| Variable | Groups | N | Mean | Std. deviation |

| Climate fears | Saudi Arabia | 51 | 22.294 | 5.746 |

| Egypt | 99 | 22.767 | 5.514 | |

| Sudan | 52 | 28.211 | 6.1369 | |

| Syria | 35 | 33.429 | 3.492 | |

| Iraq | 51 | 21.765 | 8.578 | |

| Kuwait | 50 | 24.140 | 9.315 | |

| Yemen | 82 | 30.098 | 6.0156 | |

| Lebanon | 82 | 25.390 | 7.664 | |

| Jordan | 58 | 26.121 | 7.344 | |

| Oman | 94 | 28.383 | 6.241 | |

| Tunisia | 25 | 26.520 | 8.940 | |

| Algeria | 62 | 29.564 | 7.995 | |

| Libya | 47 | 33.425 | 3.838 | |

| Palestine | 61 | 28.032 | 7.567 | |

| Mauritania | 50 | 24.600 | 7.028 | |

| Emiratis | 60 | 22.700 | 6.416 | |

| Qatar | 61 | 27.607 | 6.333 | |

| Bahrain | 60 | 21.417 | 9.987 | |

| Total | 1080 | 26.311 | 7.762 | |

| Climate anxiety | Saudi Arabia | 51 | 16.686 | 3.712 |

| Egypt | 99 | 16.172 | 3.985 | |

| Sudan | 52 | 20.327 | 4.793 | |

| Syria | 35 | 24.71 | 2.619 | |

| Iraq | 51 | 16.216 | 5.088 | |

| Kuwait | 50 | 18.280 | 6.155 | |

| Yemen | 82 | 21.500 | 5.088 | |

| Lebanon | 82 | 18.622 | 5.369 | |

| Jordan | 58 | 19.276 | 5.184 | |

| Oman | 94 | 20.319 | 4.976 | |

| Tunisia | 25 | 18.800 | 6.500 | |

| Algeria | 62 | 21.693 | 5.416 | |

| Libya | 47 | 24.021 | 3.206 | |

| Palestine | 61 | 20.492 | 5.884 | |

| Mauritania | 50 | 18.140 | 4.940 | |

| Emiratis | 60 | 16.933 | 4.4259 | |

| Qatar | 61 | 19.443 | 5.512 | |

| Bahrain | 60 | 16.500 | 6.345 | |

| Total | 1080 | 19.191 | 5.513 | |

| Climate depression | Saudi Arabia | 51 | 17.588 | 3.623 |

| Egypt | 99 | 17.667 | 3.904 | |

| Sudan | 52 | 21.788 | 4.425 | |

| Syria | 35 | 25.314 | 1.659 | |

| Iraq | 51 | 21.667 | 5.141 | |

| Kuwait | 50 | 23.080 | 4.285 | |

| Yemen | 82 | 23.037 | 3.9673 | |

| Lebanon | 82 | 19.512 | 5.124 | |

| Jordan | 58 | 20.603 | 5.334 | |

| Oman | 94 | 21.872 | 4.333 | |

| Tunisia | 25 | 23.200 | 4.213 | |

| Algeria | 62 | 24.452 | 3.278 | |

| Libya | 47 | 25.340 | 1.959 | |

| Palestine | 61 | 22.590 | 4.444 | |

| Mauritania | 50 | 19.060 | 4.528 | |

| Emiratis | 60 | 17.717 | 4.654 | |

| Qatar | 61 | 20.607 | 4.200 | |

| Bahrain | 60 | 24.217 | 3.701 | |

| Total | 1080 | 21.347 | 4.840 | |

| Climate obsessive-compulsive | Saudi Arabia | 51 | 10.843 | 3.337 |

| Egypt | 99 | 11.444 | 3.101 | |

| Sudan | 52 | 12.692 | 3.562 | |

| Syria | 35 | 15.657 | 3.086 | |

| Iraq | 51 | 10.725 | 3.505 | |

| Kuwait | 50 | 11.700 | 3.965 | |

| Yemen | 82 | 13.866 | 3.851 | |

| Lebanon | 82 | 12.634 | 3.854 | |

| Jordan | 58 | 12.293 | 3.857 | |

| Oman | 94 | 12.872 | 3.608 | |

| Tunisia | 25 | 12.200 | 4.368 | |

| Algeria | 62 | 12.855 | 4.016 | |

| Libya | 47 | 14.659 | 3.466 | |

| Palestine | 61 | 13.492 | 3.749 | |

| Mauritania | 50 | 11.940 | 3.771 | |

| Emiratis | 60 | 11.150 | 3.214 | |

| Qatar | 61 | 13.164 | 2.973 | |

| Bahrain | 60 | 10.783 | 3.902 | |

| Total | 1080 | 12.456 | 3.786 | |

| Climate grief | Saudi Arabia | 51 | 13.941 | 3.489 |

| Egypt | 99 | 14.050 | 4.079 | |

| Sudan | 52 | 16.673 | 4.601 | |

| Syria | 35 | 21.000 | 2.314 | |

| Iraq | 51 | 13.039 | 4.749 | |

| Kuwait | 50 | 14.900 | 5.418 | |

| Yemen | 82 | 18.219 | 4.640 | |

| Lebanon | 82 | 15.415 | 5.096 | |

| Jordan | 58 | 16.431 | 4.305 | |

| Oman | 94 | 16.851 | 4.861 | |

| Tunisia | 25 | 15.800 | 5.447 | |

| Algeria | 62 | 17.452 | 4.587 | |

| Libya | 47 | 20.383 | 2.601 | |

| Palestine | 61 | 17.377 | 4.903 | |

| Mauritania | 50 | 15.320 | 4.666 | |

| Emiratis | 60 | 14.333 | 4.036 | |

| Qatar | 61 | 16.213 | 4.458 | |

| Bahrain | 60 | 13.667 | 5.464 | |

| Total | 1080 | 16.0546 | 4.916 | |

| Climate anger | Saudi Arabia | 51 | 8.412 | 2.578 |

| Egypt | 99 | 8.404 | 2.567 | |

| Sudan | 52 | 10.250 | 2.626 | |

| Syria | 35 | 12.286 | 1.872 | |

| Iraq | 51 | 8.647 | 2.591 | |

| Kuwait | 50 | 9.420 | 3.078 | |

| Yemen | 82 | 11.158 | 2.385 | |

| Lebanon | 82 | 9.598 | 2.998 | |

| Jordan | 58 | 9.724 | 2.745 | |

| Oman | 94 | 10.223 | 2.863 | |

| Tunisia | 25 | 10.080 | 2.783 | |

| Algeria | 62 | 10.871 | 2.512 | |

| Libya | 47 | 11.829 | 1.971 | |

| Palestine | 61 | 10.377 | 2.823 | |

| Mauritania | 50 | 9.220 | 2.992 | |

| Emiratis | 60 | 8.483 | 2.613 | |

| Qatar | 61 | 10.229 | 2.692 | |

| Bahrain | 60 | 8.917 | 2.830 | |

| Total | 1080 | 9.821 | 2.862 | |

| Climate alienation | Saudi Arabia | 51 | 8.745 | 2.348 |

| Egypt | 99 | 8.667 | 2.236 | |

| Sudan | 52 | 10.346 | 2.834 | |

| Syria | 35 | 12.143 | 1.517 | |

| Iraq | 51 | 8.216 | 3.009 | |

| Kuwait | 50 | 9.040 | 3.356 | |

| Yemen | 82 | 11.341 | 2.294 | |

| Lebanon | 82 | 9.988 | 2.512 | |

| Jordan | 58 | 9.689 | 2.729 | |

| Oman | 94 | 10.468 | 2.769 | |

| Tunisia | 25 | 10.200 | 3.214 | |

| Algeria | 62 | 10.839 | 3.074 | |

| Libya | 47 | 12.170 | 1.869 | |

| Palestine | 61 | 10.393 | 3.105 | |

| Mauritania | 50 | 9.540 | 2.509 | |

| Emiratis | 60 | 8.600 | 2.149 | |

| Qatar | 61 | 9.754 | 3.053 | |

| Bahrain | 60 | 8.067 | 3.434 | |

| Total | 1080 | 9.850 | 2.911 | |

| Climate somatic symptoms | Saudi Arabia | 51 | 13.882 | 3.096 |

| Egypt | 99 | 14.01 | 3.512 | |

| Sudan | 52 | 17.211 | 4.367 | |

| Syria | 35 | 20.029 | 2.319 | |

| Iraq | 51 | 13.980 | 4.851 | |

| Kuwait | 50 | 15.060 | 5.024 | |

| Yemen | 82 | 18.354 | 3.769 | |

| Lebanon | 82 | 16.098 | 4.253 | |

| Jordan | 58 | 16.2069 | 4.229 | |

| Oman | 94 | 17.4681 | 4.173 | |

| Tunisia | 25 | 16.000 | 4.958 | |

| Algeria | 62 | 18.016 | 4.575 | |

| Libya | 47 | 19.979 | 2.762 | |

| Palestine | 61 | 17.098 | 4.746 | |

| Mauritania | 50 | 15.020 | 4.123 | |

| Emiratis | 60 | 14.400 | 3.646 | |

| Qatar | 61 | 17.557 | 3.771 | |

| Bahrain | 60 | 16.967 | 3.439 | |

| Total | 1080 | 17.243 | 4.257 |

Table 11

Results of group differences in MHPCC due to residing country variable

| Variables | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. | |

| Climate fears | Between groups | 12653.035 | 17 | 744.296 | 15.098 | .000 |

| Within groups | 52352.432 | 1062 | 49.296 | |||

| Total | 65005.467 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate anxiety | Between groups | 5825.357 | 17 | 342.668 | 13.494 | .000 |

| Within groups | 26969.351 | 1062 | 25.395 | |||

| Total | 32794.707 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate depression | Between groups | 6453.078 | 17 | 379.593 | 21.414 | .000 |

| Within groups | 18825.714 | 1062 | 17.727 | |||

| Total | 25278.792 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate obsessive-compulsive | Between groups | 1579.517 | 17 | 92.913 | 7.104 | .000 |

| Within groups | 13890.350 | 1062 | 13.079 | |||

| Total | 15469.867 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate grief | Between groups | 4175.686 | 17 | 245.629 | 11.911 | .000 |

| Within groups | 21900.090 | 1062 | 20.622 | |||

| Total | 26075.777 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate anger | Between groups | 1230.338 | 17 | 72.373 | 10.105 | .000 |

| Within groups | 7606.172 | 1062 | 7.162 | |||

| Total | 8836.510 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate alienation | Between groups | 1412.719 | 17 | 83.101 | 11.413 | .000 |

| Within groups | 7732.981 | 1062 | 7.282 | |||

| Total | 9145.700 | 1079 | ||||

| Climate somatic symptoms | Between groups | 3714.094 | 17 | 218.476 | 12.675 | 0.000 |

| Within groups | 18305.305 | 1062 | 17.237 | |||

| Total | 22019.399 | 1079 |

The results shown in Table 12 about the direction of the differences between residing country subgroups indicated that:

Table 12

Multiple comparisons in mental health problems related to climate change due to residing country

| Variables | Country | Syria | Libya | Yemen | Algeria | Oman | ||||||

| Climate fears | Saudi Arabia | 11.134 | 11.131 | 7.807 | 7.270 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 10.661 | 10.658 | 7.329 | 6.797 | 5.615 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Iraq | 11.664 | 11.661 | 8.333 | 7.799 | 6.618 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lebanon | 8.038 | 8.035 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Kuwait | 9.288 | 9.285 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Mauritania | 8.828 | 8.825 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Jordan | – | 7.035 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bahrain | 12.012 | – | – | 8.148 | 6.966 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| UAE | 10.728 | – | 7.397 | 6.864 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Jordon | 7.305 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Variables | Country | Syria | Libya | Yemen | Algeria | Oman | ||||||

| Climate anxiety | Saudi Arabia | 8.208 | 7.335 | 4.814 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 8.543 | 7.849 | 5.328 | – | 4.147 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Iraq | 8.499 | 7.806 | 5.284 | 5.478 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Kuwait | 6.434 | 5.741 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lebanon | 6.092 | 5.399 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Mauritania | 6.574 | 5.881 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| UAE | 7.781 | 7.088 | 4.567 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bahrain | 8.214 | 7.521 | 5.00 | 5.193 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Variables | Country | Syria | Kuwait | Yemen | Algeria | Sudan | Oman | Palestine | Iraq | Bahrain | Libya | Tunisia |

| Climate depression | Saudi Arabia | 7.726 | 5.492 | 5.448 | 8.863 | – | – | 5.002 | – | 6.628 | – | – |

| Jordan | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4.737 | – | |

| Egypt | 7.648 | 7.674 | 5.369 | 6.785 | 4.122 | 4.206 | 4.923 | 4.00 | 6.550 | 7.674 | – | |

| UAE | 7.598 | 5.363 | 5.319 | 6.735 | – | 4.156 | 4.873 | – | 6.500 | – | 5.483 | |

| Lebanon | 5.802 | – | 3.524 | 4.939 | – | – | – | – | 4.704 | 5.828 | – | |

| Qatar | 4.708 | 4.734 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Mauritania | 6.254 | – | – | 5.392 | – | – | – | – | 5.157 | – | – | |

| Variables | Country | Syria | Libya | |||||||||

| Climate obsessive-compulsive | Saudi Arabia | 4.814 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 4.213 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Iraq | 4.932 | 3.876 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| UAE | 4.507 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bahrain | 4.874 | 3.876 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Variables | Country | Syria | Libya | Yemen | ||||||||

| Climate grief | Saudi Arabia | 7.059 | 6.442 | 4.278 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 6.949 | 6.332 | 4.169 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Iraq | 7.961 | 7.344 | 5.180 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Kuwait | 6.100 | 5.483 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lebanon | 5.585 | 4.968 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Mauritania | 5.680 | 5.063 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| UAE | 6.667 | 6.049 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bahrain | 7.333 | 6.720 | 4.552 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Variable | Country | Syria | Libya | Yemen | Algeria | |||||||

| Climate anger | Saudi Arabia | 3.874 | 3.418 | 2.747 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 3.882 | 3.426 | 2.754 | 2.467 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Iraq | 3.639 | 3.183 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| UAE | 3.802 | 3.346 | 2.675 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bahrain | 3.369 | 2.913 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Variables | Country | Syria | Libya | Yemen | Algeria | Oman | ||||||

| Climate alienation | Saudi Arabia | 2.596 | 3.425 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 3.476 | 3.504 | 2.675 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Iraq | 3.927 | 3.954 | 3.126 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Kuwait | – | 3.130 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| UAE | 3.543 | 3.570 | 2.741 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bahrain | 4.076 | – | 3.275 | 2.772 | 2.401 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Climate somatic symptoms | Saudi Arabia | 6.146 | 6.096 | 4.471 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 6.018 | 5.969 | 4.344 | 4.006 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Iraq | 6.048 | 4.373 | 4.036 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Kuwait | 4.969 | 4.919 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Mauritania | 5.009 | 4.959 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| UAE | 5.629 | 5.579 | 3.954 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Bahrain | 6.279 | 6.229 | 4.504 | 4.266 | 3.718 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Mean differences were significate (p-value <0.05).

1. Climate fears are higher in Syria, Yemen, Algeria, Libya, and Oman compared to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Jordan, UAE, Bahrain, and Mauritania. The mean differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Table 12).

2. Climate anxiety is higher in Syria, Yemen, Algeria, Libya, and Oman when compared to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, UAE, Mauritania, and Bahrain, where the mean differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Table 12).

3. Climate depression was higher in Syria, Yemen, Libya, Oman, Algeria, Palestine, Sudan, Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, and Tunisia when compared to Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, UAE, and Bahrain, where the averages between the differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Table 12).

4. Climate obsessive-compulsive was higher in Syria and Libya when compared with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, and UAE, where the values of the mean differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Table 12).

5. Grief was higher in Syria, Yemen, and Libya compared to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Mauritania, UAE, Lebanon, Kuwait, and Bahrain, and the mean differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05)(Table 12).

6. Anger was higher in Syria, Yemen, Libya, and Algeria when compared to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Palestine, UAE, and Bahrain; the mean differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Table 12).

7. Climate alienation is higher in Syria, Yemen, Libya, Algeria, and Oman when compared to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, UAE, and Bahrain; the mean differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Table 12).

8. The climatic somatic symptoms are higher in Syria, Yemen, Oman, Algeria, and Libya compared to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, UAE, Mauritania, and Bahrain, and the mean differences were statistically significant (Table 12).

4Discussion

The study findings showed average levels of mental health problems related to climate change. Many studies found a correlation between climate change and mental health problems [9, 12, 21, 22, 29, 31, 32, 46, 54, 59, 67]. Hayes et al. [32] mentioned that the individual’s perception of climate change as a global environmental threat also contributes to psychological stress, negatively affecting their psychological, social, emotional, and spiritual health. The environment is somewhat stable and gradually changes, causing a feeling of security, safety, and psychological reassurance for individuals. The individual realizes that climate change threatens his life and that the world has become frightening. A source of danger due to what is happening from climatic phenomena and violent environmental disasters, this leads to a permanent feeling of tension and anxiety about the future. Then, this negatively affects the individual’s psychological health, and what supports the individual’s realization that any climate change threatens his life and that the world has become frightening and disappearing is the existence of social structures and intense public perceptions of risks and disasters, which leads to feelings of fear, anxiety, frustration, despair, helplessness depression, complicated grief, and other mental health problems. Scragg, Jones and Fauvel [51] and Al Eid et al. [5] concluded that much psychological distress could arise from exposure to unexpected and severe traumatic events, such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Also, Fritze et al. [28] mentioned that people might face indirect threats when they receive weather warnings, future disaster seasons, or hear about the environmental stresses experienced by people in other parts of the world. Thus, individuals experience climate change not as an immediate threat - but as a global threat, often distant in time and space or as a threat to the way of life itself.

Recently, Clayton [15] found a relationship between climate change and adverse effects on mental health. In recent years there has been a growing interest in the possibility of indirect effects such as anxiety related to perceptions of climate change, even among people who have not been exposed to any direct climate change events.

Also, McMichael [39] pointed out that climate change represented “a threat” to health, doing the existing social injustice. According to [16, 19] the fact that exposure to natural disasters is not only the cause of mental health problems, but it may be due to displacement, unstable housing, difficulty accessing support services and employment, increased parental stress, low social support, deficiencies in the capacity of services provided to individuals during disasters, and the high level of pervasive distress, delayed the restoration of safety; all these events increases the number of individuals who suffer from mental health problems after natural disasters.

Fritze et al. [28] pointed out that climate change significantly impacts mental health, referring to anxiety about the future. Also, Salcioglu et al. [cited in 7] pointed out that extreme weather events such as floods, forest fires, free waves, and hurricanes are associated with specific mental health problems, such as severe anxiety and post-trauma disorders. Ahern et al. [2] added that post-traumatic disorder, abuse of children, aggression among children, and suicide are linked to floods. Also, Coelho et al. [17] found a relationship between floods with loss and chronic failure, depression, disability, chronic psychological stress, and dedicated concern.

Since early 2007, “Albrecht,” an environmental philosopher, has noted that the psychological stress associated with global climate change leads to mental health problems, including eco-anxiety and eco-paralysis solastalgia. Eco-anxiety refers to the concern that people are persistently surrounded by evil and threatened problems associated with climate change. Eco-paralysis indicates behavior and isolation from the gradual removal of the house because of ecological climate changes, and the feelings associated with displacement after extreme weather conditions are related to climate change. Solastalgia is intended for complex feelings of lack of effective action to mitigate climate change risk significantly. This new vocabulary provides a language to explore some extensive mental health effects of escalating climate change [3, 15].

Clayton [15] emphasized that “climate change is not just an environmental, but also a psychological problem.” Therefore, when studying the relationship between climate change and mental health, Hayes et al. [32] pointed out that mental health problems alone have been complex for four reasons: the individual’s responses to environmental events may be transient and even more in non-environmental circumstances. Thus, they are not diagnosed that they have raised climate change on mental health. Therefore, it may be difficult to separate the exact impact of climate change on mental health on other social determinants due to the complex nature of mental health. Mental health, such as physical health, is formed through social and environmental factors that can affect - often increase - other health determinants, such as climate change. Therefore, there is a strong argument for continuing efforts of researchers to explore the relationship between climate change and mental health.

The average levels of MHPCC can be explained in light of Construal Level Theory (CLT), which states that objects, events, and structures (e.g., consequences of climate change) can be thought of in somewhat construal terms depending on the psychological distance [53]. The further away something is from the direct experience of individuals, the more abstract the event will be. An event geographically far from where we live is perceived in a more abstract and general way and is unlikely to occur in our city. On the contrary, an event geographically close to us leads to a concrete interpretation that depends on the context; thus, individuals perceive the imminence of its occurrence in their living space. People in the study sample thought about climate change abstractly and realized that it is more geographically remote than it is. This abstract thinking also made the sample members not realize the seriousness of climate change, and then the level of psychological problems of anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, grief, anger, and others came to a moderate degree.

Also, we can explain that the sample members reported an average level of MHPCC due to their lack of awareness of climate change. For example, in Lebanon, Hussein et al. [34] revealed that only a small percentage of citizens are highly aware of climate change and their intentions to reduce the carbon lifestyle. Also, Weber [63] postulated that perceptions of climate change or how humans perceive them are a critical factor in human adaptation to those changes.

The findings of the current study also found differences between married and widower subgroups in climate anxiety. Married individuals have many responsibilities and stress in a crisis; therefore, they are more anxious and worried about unexpected climate changes, especially when they hear about the risks of climate change in the overworld around them.

The results about differences in MHPCC due to the residing country are consistent with what Willox et al. [64, 65] said that there are risk factors that increase the psychological effects of disasters, including severity and suddenness, the social, historical, and cultural context in which they occurred as societies that do not have adequate means to respond to emergencies, vulnerability, and poverty increase the exposure of such communities to natural disasters.

Exposure to natural disasters is not only the cause of mental health problems but also due to displacement, unstable housing, difficulty accessing services, support and employment, increased parental pressure, low social support, palaces, restrictions in the capacity of individuals during disasters, high level of chaos and disorder, and delayed restoration of safety [19, 41]. In addition, the former diseased history of severe mental health problems such as psychosis or suicide attempts increases individuals in these extreme climatic disasters, increasing mental health problems following exposure to naturaldisasters.

The 2021 Arab Region Disaster Risk Reduction Regional Assessment Report [21–26, 48] states that less than 15% of the Middle East’s population was exposed to moderate and high-level floods, and examples of this flooding from Jeddah in Saudi Arabia in 2009, which killed about 150 people and damaged more than 8,000 homes in the south of the city, where the majority of the population were poor migrant workers. Tropical cyclones are also a catastrophic hazard in the region. About 20,000 people in Amman were affected by Hurricane Guno Orbital in 2007, which caused over $4 billion in damage.

Climate-related hazards are increasing in frequency and intensity, witnessing unsustainable consumption and production patterns that complicate these risks; in addition to the fact that the COVID-19 crisis is still widespread and threatening lives, among Arab countries that it is these various extreme phenomena that suffer the most, be it sea-level rise as in Bahrain and Comoros; Hurricanes like Somalia, the Emirates, and Oman. And drought like in Jordan, Syria, and Iraq. As well as earthquakes in Egypt, Algeria, Palestine, Syria, Morocco, Lebanon, forest fires, as Lebanon; and the dangers of heavy rain and the consequent emergence of the locust problem, as in Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen. There is no doubt that these countries, with the threat of these natural disasters to their populations as a result of climate change, are the Arab countries with the highest prevalence of mental health problems arising from the direct and indirect effects of unusual and extreme climate changes.

The difference in MHPCC can also be explained in light of what is happening in some Arab countries with wars and conflicts that intersect with the impacts of climate change and catastrophic natural phenomena such as earthquakes. Drought, sea-level rise, hurricanes, forest fires, and others increased the magnitude of these mental health problems in countries such as Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and Libya, and this was indicated by the results of statistical analysis of the differences between groups by government in where the members of the research sample live. Although the theoretical mental health literature indicates gender differences in mental health problems and disorders, the current study found no statistically significant differences between men and women in mental health problems related to climate change.

There is no doubt that such harsh environments, extreme climatic conditions, conflicts, wars, and the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic all this has negatively affected the physical and mental health of all the male and female members of the Arab world, as well as their family and educational status; and so the results of the current study conclude that the differences in mental health problems related to climate change based on gender, educational level, and marital status do not meet statistical significance. In his 1929 book (Civilization and Its Dissatisfaction), Freud pointed out an interrelationship between the mind’s inner world and the environment’s outer world. Freud stated a closer relationship between the ego and its world, which is the goal of contemporary ecopsychology, which seeks to expand and treat the emotional connection between people and the environment in which they live.

Because the world, including the Arab countries today, faces extreme and unprecedented climate changes that have caused enormous human, economic and social losses, we need the efforts of climate psychologists to conduct more research to mitigate the adverse effects of climate changes on humans and to enable members of the Arab community to adapt to these changes now and in the future, as there is no interest in psychology departments in Arab universities to study climate psychology at the undergraduate or postgraduate levels.

4.1Implications of the results

Climate change is a futuristic, past, and present problem. Therefore, it is better to think about climate change because it is a sophisticated process of long-term deterioration, which psychologists call the creeping problem. Because of this, it is necessary to face the consequences of climate change on human mental health [7, 30, 38].

Hayes et al. [32] mentioned that studying climate change’s effects on mental health helps the mental health community differentiate and predict the patterns of mental health problems, such as post-traumatic disorder, after cruel weather events. Understanding the unequal effects of climate change on marginalized groups supports public health prevention strategies to protect vulnerable persons from mental illness problems.

The Ottawa Charter in 1986 pointed out that to reach a state of physical, psychological, and social health, the person must identify and achieve ambition, fulfill his needs, and adapt to the environment. Thus, if the person loses the ability to adapt to the environment in which the outcome of climate change is failing, the ability to access the physical, psychological, and social situation, especially as economic and social services are inadequate, and sometimes the weak and absence of policies that support individuals and communities economically affected by climate change, increasing the harmful effects of climate changes on mental health [18].

In 2015, the WHO [67] developed a framework for building health systems that adapt to climate change. This framework provides guidelines for health professionals to prevent them from increasing health systems’ capacity to adapt, sustain, and strengthen in the wake of climate change. At the same time, this framework ignores the complications of mental health systems, such as the current lack of mental health infrastructure, finance, and resources [57].

The Regional Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction in the Arab region of 2021 mentioned that the Arab countries face an increasing range of complex risks that interact with assertive communication and rapid transformation, offering rich opportunities for further growth and development. However, this area is simultaneously vulnerable to the challenges caused by drought, conflict, rapid urbanization, internal displacement, and migration. Climate-related hazards are increasing in frequency and severity. They are experiencing unsustainable consumption and production patterns that increase these risks, and the COVID-19 crisis is still unfolding, indicating the global nature of its multidimensional manifestations. This requires new risk governance regulations for integrated and consistent limitations.

In 2015, the 22 Arab countries adopted a Disaster Risk Reduction Penalty Framework for all United Nations member states. This framework has acquired the character of the rapidly changing and interdependent change, the growing threat of natural hazards and hazards from human activities, and the relevant biological, ecological, and technological hazards and risks. It provides a syntactic framework for a logical link between risk reduction and capacity building to address the challenges of conflict, displacement, poverty, unsustainable production and consumption patterns, climate change, and sustainable development [48].

This disaster risk reduction framework, adopted by the 22 Arab countries, did not include measures to mitigate the impact of climate change on mental health due to insufficient attention paid to mental health systems.

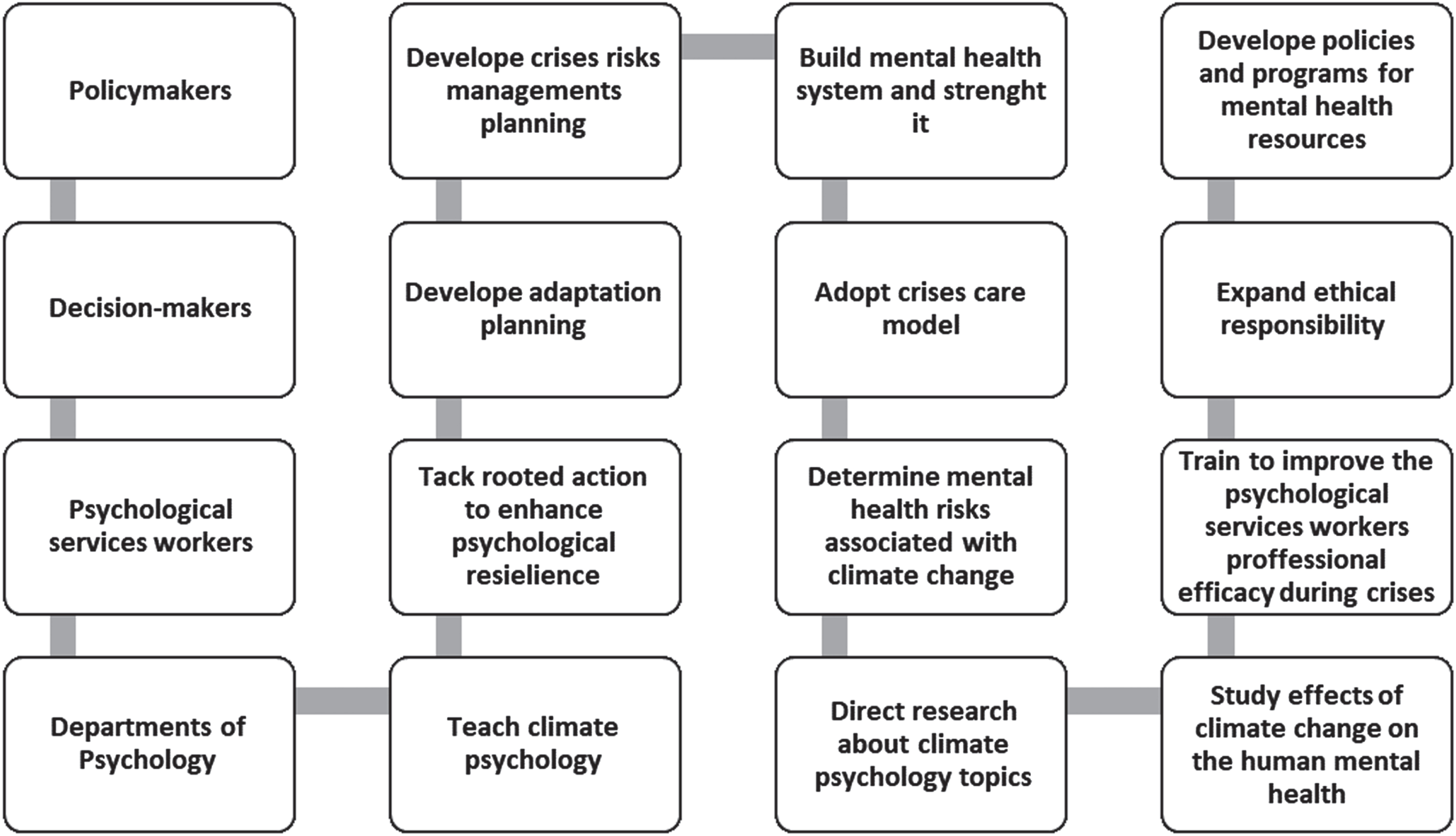

From the results of the current study, the following procedural framework was designed that will help mental health system workers, including policymakers, decision-makers, departments of psychology in Arab universities, as well as mental health service workers, to manage the mental health risks arising from extreme climatic changes in Arab countries:

1. Teach climate psychology in psychology departments in Arab universities and direct descriptive, quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research on climate psychology topics on the impact of climate change on mental health.

2. Identify and understand the direct and indirect risks that climate change poses to mental health, both direct and indirect, and provide a continuously updated database of them for disaster risk management planning.

3. Develop integrated strategies that include education, communication, surveillance, infrastructure development, and health interventions for mitigation and adaptation to climate change in terms of adaptation planning and involvement of individuals and organizations in developing a strategy by providing the necessary information on the scale of the impact of human local climate change: economy and health.

4. Take rooted actions, plan programs to enhance psychosocial resilience, empower individuals, and develop policies to address broad psychosocial impacts.

5. Adopt the crisis and disaster relief model to reform the primary psychological and social areas at risk of disasters, applying the principles of disaster and crisis risk management.

6. Take rapid and systematic action to combat the cross-reactivity of psychological, social, and social health. Environmental determinants of mental health may exacerbate mental health risks associated with climate change.

7. Improve environmental literacy, expand ethical accountability, enhance resources and training to improve the efficiency of counseling and psychotherapy workers during disasters and crises, and increase health systems’ resilience, sustainability, and strength during extreme climate change.

8. Interest in providing psychological services after disasters and crises, including educating community members and preparing before natural disasters, such as providing preventive and development counseling programs.

9. Paying attention to emergency psychological services, applying the health justice approach to all segments of society without discrimination or discrimination.

10. Assess existing mental health services and build mental health systems through developing mental health resource policies and programs to strengthen them to adapt to the extreme global climate changes.

11. Provide mental health professionals with guidelines that will enable them to predict mental health consequences of climate change at the individual and societal level to prevent and prepare for them, with the ultimate goal of protecting the health of individuals.

Fig. 1

A procedural framework for policymakers, decision-makers, psychological service workers, and psychology departments to manage the risks of climate change impacts on mental health.

4.2Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This study is an epidemiological study concerned with measuring the level of MHPCC among people in the Arab world. One of the strengths of this study is its large sample (1080 selected participants from 18 Arab countries). Another strength of this study is that it is considered one of the first Arabic studies. We noted the lack of interest by Arab researchers in studying the direct and indirect effects of climate on mental health, which is another strength. Also, the current study is a comparative study of the prevalence of MHPCC among individuals from 18 Arab countries by gender, educational level, marital status, and the country where they live.

These limitations of this study include a descriptive comparative survey design that did not analyze other psychological, social, economic, and personal determinants of mental health. Therefore, the results of this study failed to demonstrate the causal links between climate change, direct and indirect impacts, and the role of other mental health determinants as mediating factors for this association. Thus, future studies on this subject must also demonstrate the long-term effects of climate change on mental health, whether longitudinal or cross-sectional, with a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed research design. We also need more intervention studies to mitigate the impact of climate change on mental health and to improve the quality of life of those negatively affected by climate change, especially the most affected groups of children, the elderly, patients with chronic diseases, people with special needs and patients with cancer tumors, be it counseling, curative or palliative care interventions.

5Conclusion

The results showed an average level of MHPCC prevalence, such as climate fears, climate anxiety,climate somatic symptoms, climate depression, climate alienation, climate anger, climate grief, and climate stress from climate changes worldwide. There were statistically significant differences in the MHPCC due to the participants’ residing country. Also, the results found no statistically significant differences in the MHPCC due to gender, educational class, and marital status except in the climate anxiety (differences in favor of married subgroup compared to widower).

Ethics statement

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Conflict of interest

The author reports no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia, for providing administrative and technical support.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

References

[1] | Agnew R . Dire forecast: A theoretical model of the impact of climate change on crime. Theor Criminol. (2012) ;16: (1):21–42. |

[2] | Ahern MM , Kovats RS , Wilkinson P , Few R , Matthies F . Global health impacts of floods: Epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiol Rev. (2005) ;27: :36–46. |

[3] | Albrecht G . Chronic environmental change: Emerging ‘psychoterratic’ syndromes. In: Climate change and human well-being. New York: Springer; (2011) , pp. 43–56. |

[4] | Alderman K , Turner LR , Tong S . Assessment of the health impacts of the summer floods in Brisbane. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. (2013) ;7: (4):380–86. |

[5] | Al Eid N , Arnout B , Alqahtani M , Fadhel F , Abdelmotelab A . The mediating role of religiosity and hope for the effect of self-stigma on psychological well-being among COVID-19 patients. WORK. (2021) ;68: (3):525–41. |

[6] | Arnout B . Application of structural equation modeling to develop a conceptual model for entrepreneurship for psychological service workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. WORK. (2021) ;69: :1127–41. |

[7] | Arnout B . The scientific encyclopedia of the psychology of climate change. Takween for Publishing and Distribution: Riyadh, (2022) . |

[8] | Azuma K , Ikeda K , Kagi N , Yanagi U , Hasegawa K , Osawa H . Effects of water-damaged homes after flooding: Health status of the residents and the environmental risk factors. Int J Environ Health Res. (2014) ;24: (2):158–75. |

[9] | Bryant R , Waters E , Gibbs L , Gallagher C , Pattison P , Lusher D , MacDougall C , Harms L , Block K , Snowdon E , Sinnott V , Ireton G , Richardson J , Forbes D . Psychological outcomes following the Victorian Black Saturday bushfires. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. (2014) ;48: (7):634–43. |