Understanding work inclusion: Analysis of the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities on employment in the Icelandic labor market

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

People with intellectual disabilities experience persistent marginalization in relation to work and employment. The concept of work inclusion provides a way of generating a more specific understanding of the meaning of employment participation. Work inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities focuses not on mere presence, but instead emphasizes relational aspects and potential for meaningful participation.

OBJECTIVE:

In this paper we report on an empirical study into the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities of employment participation in the Icelandic labor market. We considered their experiences in relation to four key components of work inclusion, placing emphasis on how they perceived opportunities for inclusion related to social relations, belonging, valued contributions and trust.

METHODS:

This study used a qualitative research design. Data was collected with semi-structured interviews with 9 participants with intellectual disabilities who all had experience of being employed in the Icelandic labor market.

RESULTS:

Our findings show the role of the work environment in participants’ experiences of opportunities for having good relations at work, having a sense of belonging to the organization, being able to make a contribution to the goals of the organization, and receiving trust in one’s professional role and responsibility. When participants experienced opportunities in relation to these basic components of work inclusion, they felt more positively about their employment participation. Lack of opportunities was reported as a reason for segregation and withdrawal.

CONCLUSION:

This study shows the importance for work organizations and other actors in the labor market of paying attention to components of work inclusion and their relation with corporate culture.

1Introduction

1.1People with disabilities, work and employment

In this paper we report on an empirical study into the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities of employment participation in the Icelandic labor market. More specifically, we considered their experiences in relation to four key components of work inclusion, placing emphasis on how they perceived opportunities for inclusion related to social relations, belonging, valued contribution and trust.

People with disabilities constitute a marginalized and excluded group in relation to different domains of society, including in work and employment. When it comes to marginalization in the labor market, reports by the OECD [1] and the European Union [2] demonstrate that compared to people without disabilities, people with disabilities are more likely to be outside the labor market or unemployed. Also in Iceland there is a gap in employment rates between persons with and without disabilities, estimated by Eurostat at around 20 percentage points [2] and by Statistics Iceland [3] at around 50 percentage points. Although there is a general lack of statistical data, there is a consensus that employment participation is even more challenging for people with intellectual disabilities compared to people with disabilities in general [4].

1.2Work inclusion

Besides a large body of research concerned with identifying barriers in the labor market, for example disability-related prejudice in society [5] and bias in employers’ hiring decisions [6], scholars have emphasized work inclusion as a conceptual point of departure for understanding processes that lead to marginalization as well as opportunities for participation [7]. The concept of work inclusion has been developed in relation to the more general concept of social inclusion and considers individuals’ opportunities to participate in society on a basis of respect for difference. To be included is more than physical presence and it does not mean that a person needs to accept the norms and views of the dominant groups in society, i.e. people without disabilities [7]. From a disability-related work inclusion perspective, people with disabilities cannot be expected to adjust to dominant work-related norms which reflect, for example, standard performance expectations and preconditions for employment participation. Instead, work inclusion rests on a recognition of human diversity and refers to a situation in which people have full access to valued professional roles, and opportunities are available for meaningful participation. This involves recognition of professional competence and contribution, perceptions of belonging to a larger social entity, and relationships of good quality with others in the workplace characterized by mutual trust and support [8, 9]. In empirical studies into work participation of people with disabilities in general and people with intellectual disabilities in particular, the main focus has been on social integration, i.e. work participation based on mere presence and/or existing norms about work [9]. This has led to calls for developing and applying the concept of ‘work inclusion’ within theoretical, empirical and policy perspectives.

Indeed, work inclusion has been proposed as a key concept by scholars in disability studies [e.g. 10, 11] to develop an understanding of employment participation of people with disabilities as part of an effort to fundamentally rethink what work means and how it can be organized to take diversity into account. As Abberley [12] has pointed out, the reversal of exclusion from employment is not merely employment participation, but inclusion in work in a broad sense.

Work inclusion has been the focus of empirical studies into aspects of work such as recognition of people with disabilities’ skills and competence [13] and access to roles of leadership for workers with intellectual disabilities [14], and more generally organizational culture [15, 16].

1.3Work inclusion and support in the workplace

The social environment of the workplace is important for the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities in terms of being successful, valuable and accepted as employees [4, 9]. Lysaght et al. [17] applied the concept of work inclusion in their study about the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities with regard to inclusion in diverse work settings, including paid employment in the labor market. Their study shows the general importance of work for social inclusion and identifies social relations and opportunities to develop a sense of contribution and belonging as key components.

Interestingly, in relation to organizing work, Lysaght et al. [17] show the importance of a work environment that considers employees with disabilities’ characteristics such as preference and skills. The importance of a supportive work environment has also been addressed in a study by Gustafsson et al. [18] about the role of supported employment in supporting employees with disabilities’ feelings of being in valued roles and their sense of social belonging. From their study, the authors concluded that specific attention should be given to job-matching and establishment of natural supports in the workplace. Another example is a study by Jahoda et al. [19], which suggests that supported employment has a potential to offer more opportunities for work inclusion and social interaction with other co-workers without disabilities. Recent research by Hardonk et al. [20] provides indications that this potential is not always realized, as job counsellors in supported employment experience difficulties in supporting work inclusion, notwithstanding their recognition of its importance.

1.4Inclusive work environments

Approaches based on work inclusion have also found their way into policy and legal frameworks, as illustrated by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [21], which describes state actors’ responsibility for promoting and protecting people with disabilities’ right to work within the context of a ‘work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities’ [21].

Corporate culture emerges from the literature as an important aspect related to work inclusion as it affects co-workers and supervisors’ attitudes as well as the structure and practices of the organization, for example in relation to reasonable accommodations. Several studies have described ways in which corporate culture ultimately affects employment experiences of people with disabilities [e.g. 22]. Corporate cultures that rest upon stereotypical notions of workers with disabilities may create barriers to inclusion [23], while inclusive cultures may create opportunities. The impact of corporate culture however, is not straightforward, as illustrated in a study by Mik-Meyer [24] which shows how even in organizations that place emphasis on being inclusive, people with disabilities are in some cases discursively positioned as ‘different’ by their co-workers and managers.

Research has also shown that people with disabilities are often aware of their marginalization or the risk thereof. When affirming their competence, establishing meaningful social relations or pursuing opportunities to make a valued contribution, employees with disabilities often have to engage with stereotypical expectations rooted in corporate culture. Examples are the traditional notion of the ‘ideal employee’ [25], who is constructed as a person who does not have a disability, or the ‘norm to be kind’, which replaces co-workers’ and supervisor’s professional expectations with pity and a charitable gaze [26]. Empirical studies have described how employees with disabilities are reflexive of their position within the work organization and develop strategies to resist and counteract stereotypical norms and assumptions that impact on their jobs and careers, for example in relation to performance evaluation and assessments for potential promotion [27, 28]. The potential for employees with disabilities to develop their professional identities has also been shown to be influenced by stereotypical expectations of disability [29] and prevailing discourses about disability in the organization [30]. Along with people with psychological disabilities, people with intellectual disabilities have been demonstrated to be in a particularly difficult position when it comes to stereotypical expectations and opportunities for developing their careers [31], relying often on active support from family members to get jobs and often not getting opportunities for promotion [32].

1.5Aim of the study

From the previously mentioned research about employment participation of people with intellectual disabilities it becomes clear that its outcome can be more or less successful inclusion, but also marginalization within the workplace [14] and even permanent withdrawal from the labor market, sometimes termed ‘self-segregation’ [33]. It is therefore important to generate more insight into how work inclusion is reflected in the dynamic process of employment participation of people with intellectual disabilities and the conditions in which it takes place. Consequently, this study aimed to analyze the experiences of employment participation of people with intellectual disabilities in the Icelandic labor market with a focus on opportunities for good social relations, belonging, valued contributions to the organization, and trust. Although there is no consensus in the literature on a precise definition of social inclusion in general or work inclusion in particular, these components are commonly described as basic components in relation to work inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities [7–9], thus providing a conceptual basis for generating knowledge about employment participation of people with intellectual disabilities.

This study was conducted in Iceland as part of a larger research project about work inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities. Following calls by critical disability studies scholars [34], we placed emphasis in this study on bringing forward the voices of people with intellectual disabilities themselves, as they have historically been and continue to be marginalized in debates about what constitutes work and who deserves opportunities for employment and career development. On this basis, our study aims to contribute to the growing body of empirical research that seeks to increase understanding about the meaning of work inclusion in day-to-day work experiences of people with intellectual disabilities, which has the potential to inform labor market policy and practices in work organizations.

2Methods

2.1Participants and methods

This study used a qualitative research design. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 9 participants with intellectual disabilities (four women and five men). For recruitment purposes we collaborated with organizations of people with disabilities and self-advocacy groups, who distributed invitations and information sheets about the study among their members and networks. Sampling was based on a combination of purposive and snowballing approaches. Through purposive sampling diversity was achieved in the sample in terms of gender, age, type of intellectual disability, working experience, and job type. While all participants had intellectual disabilities, their specific impairments were diverse, including Down syndrome, developmental disability and autism. None of the participants had additional physical, sensory or other impairments. Participants were aged 22–40 and most were working in the regular labor market at the time of interview. Two participants were working in a segregated setting but had experience of fulltime and part-time work in the labor market. Participants‘ work experience in the regular labor market ranged from 2 to 25 years in for example retail, entertainment, food production, providing services at municipalities (e.g. health care and well-being), and cleaning services. Most participants worked on a day-to-day basis without support from specific labor market programs and in that sense were employed in similar conditions as their colleagues without disabilities. However, all participants were entitled to such support, which is coordinated by the supported employment program at the ‘Directorate of Labor’ (Icelandic: Vinnumálastofnun) should there be a specific need. It should be noted that this type of support is limited in scope in Iceland. One participant received support from professionals at a segregated workplace, where he worked part-time. These professionals also followed him in his part-time job in the regular labor market.

We discussed with participants their experiences of work in the labor market and they were given ample opportunity and encouragement to express their views and explanations for their experiences. This means that issues related to their characteristics in general, and their impairments in particular could be mentioned by participants as being of relevance. In line with our theoretical and methodological approach, we did not develop explanations based on participants’ impairments outside of their own experiences.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants by the first author over the period September 2020 – January 2021. The purpose of the interviews was to gain rich information about participants’ experiences and views of working in the labor market. The interviews were guided by a list of topics and themes which was developed through study of literature and consisted of the following main components: participants’ background; general experience in the current job and previous jobs; experiences related to skills, responsibility, trust, and professional development; social relations at work; and expectations regarding work inclusion. Emphasis was placed on providing participants with the opportunity to discuss experiences in which they felt included in the workplace, as well as experiences that reveal barriers to inclusion.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the majority of interviews was held online through video meetings. Interviews lasted from 25 minutes to 70 minutes and were audio-recorded. All interviews were conducted and transcribed verbatim in Icelandic. At the stage of interview transcription, names and locations that could be traced back to participants were replaced by pseudonyms to ensure confidentiality. Data analysis was conducted on anonymized transcripts and descriptive quotations selected for publication were translated to English. The completion of data collection was decided upon when it emerged that participants discussed experiences of work inclusion that resonated with recurring themes and patterns in the data, which is often referred to as ‘saturation’ in data collection [35].

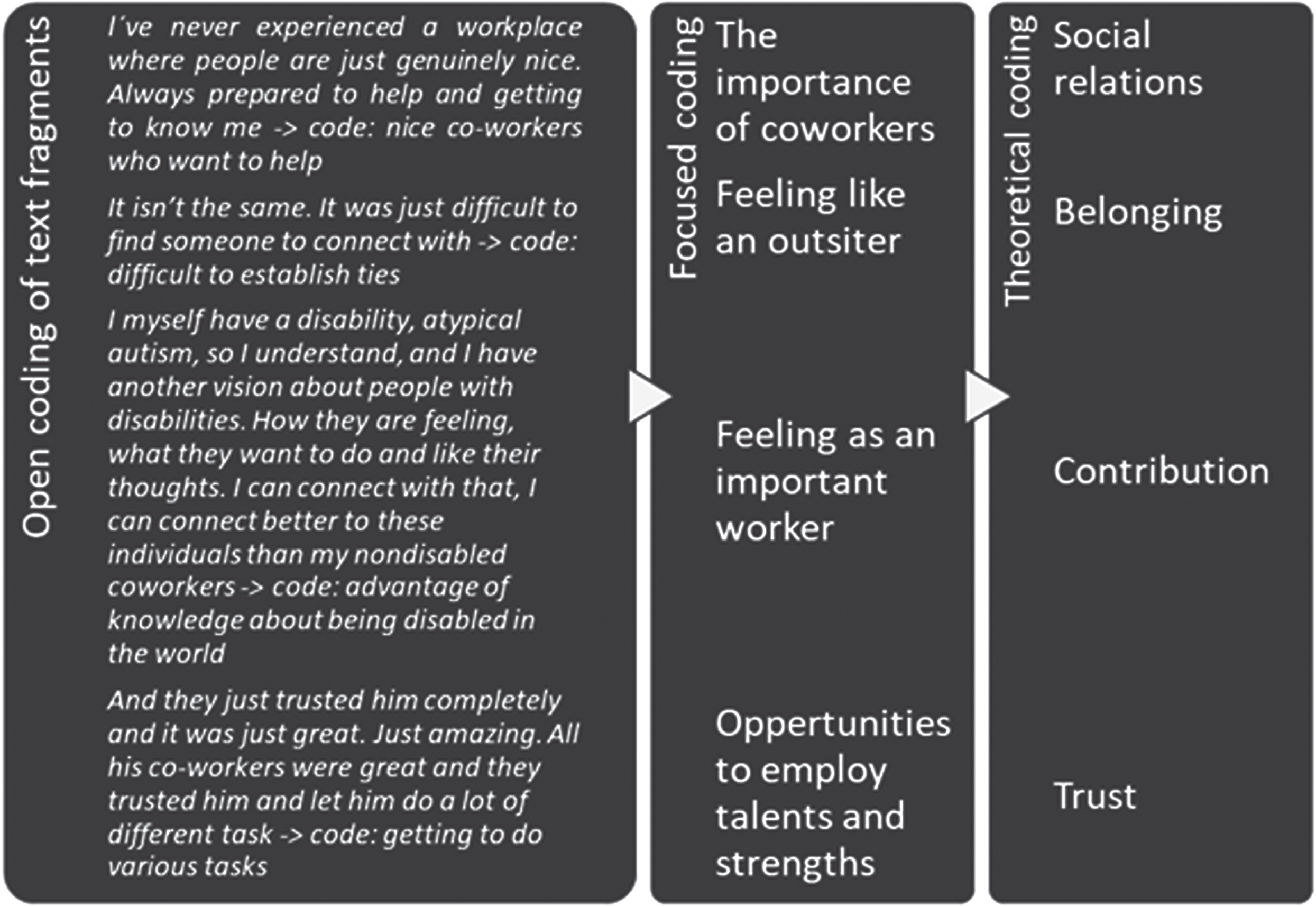

The analytical process of this study is consistent with grounded theory proposed by Charmaz [36] as it focuses both on developing in-depth understanding of individuals‘ experiences within their contexts, and theory development. In line with the principles of grounded theory, data analysis was started during the process of data collection and rested upon constant comparison and theoretical sampling. The first step of the analysis consisted of initial line-by-line coding, followed by focused coding aimed at synthesizing and categorizing the initial codes into themes that were used to revise the interview guide. In the next step basic components of work inclusion [9] were introduced as sensitizing concepts to guide theoretical coding within a grounded theory approach. The goal of introducing sensitizing concepts is not to limit the analytical process to preconceived notions, but instead to develop and deepen description and understanding of the themes and relations that emerge from the data through the process of coding and interpretation [37]. Particularly in the case of broad concepts such as the basic components of work inclusion, the combination of inductive analysis and sensitizing concepts creates opportunities for deepening our understanding of themes and patterns in participants‘ experiences in relation to work inclusion. Figure 1 shows the analytical process with code examples.

Fig. 1

Overview of the coding process.

Both researchers participated in an intersubjective dialogue to support trustworthiness of the study. This means that the researchers compared codes and interpretations in direct relation to the data, aimed at understanding how they moved through the analytical process in the direction of understanding participants’ experiences in relation to basic components of work inclusion.

2.2Ethics and consent

Given that this study is aimed at the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities, we were particularly aware of ethical challenges and considerations. One ethical aspect in relation to this study is the potentially imbalanced power relationship between researchers and participants, which may place participants at risk [38]. At no point in this study was personal information made accessible to other parties. To ensure that participants were aware of the aim of the study, their role in it, and measures to ensure anonymity and confidentiality, the researchers developed not only a standard document for information and informed consent, but also an equivalent in accessible language. Participants got the opportunity to ask questions and written consent was obtained. Emphasis was also placed on participants’ right to consult with and be assisted by another person. One participant chose to bring an assistant to the interview.

The first author, who conducted the interviews, has a background in social education and professional experience of providing support to people with intellectual disabilities. Her professional skills enabled her to engage in conversations with participants who expressed themselves in non-traditional ways. To avoid that previous experiences would influence the course of the interviews or the data analysis, the researchers placed much emphasis on collaborative development of the interview guide, and the implementation of an intersubjective procedure in the phases of analysis and writing. In addition, no interviews were held with individuals with whom the first author had any previous professional relation.

3Results

In this section the findings of our analysis are organized according to participants’ experiences of social relations, belonging, valued contribution and trust in the work environment. While these four basic components of work inclusion provided a good basis as sensitizing concepts in the analytical process, they emerged from our analysis as interrelated within the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities. Participants‘ accounts reflected aspects related to more than one basic component, offering insight into how the components were intertwined in shaping opportunities or creating barriers to inclusion. This was the case for all four components, however it was most pertinent for ‘social relations’, and ‘belonging’ on one hand, and ‘contribution’ and ‘trust’ on the other. To create space for describing how participants’ experiences relate to several components at once, the results are organized based on these two sets of closely related components.

3.1Social relations and belonging

Participants in our study explained how social relations with co-workers affected their opportunities for work inclusion and job satisfaction. They discussed their experiences of how good social relations could lead to better support from co-workers, which made them feel more secure and confident in their job performance. Julie, for example, had at the time of interview decades of experience working in the labor market. She had various jobs over the years, which she experienced as more or less successful. She explained the importance of good working relations to feel secure enough to express her needs and preferences:

Well, it's just, thanks to my co-workers, I feel like...now I just point that out to them myself. And I just told my boss: “hey, I can't just take instructions from ... ”For example, in my work unit there are two heads of department and I just can't ... if one of them tells me “do it [the task at hand] like this”and the other tells me “no, don't do it like this, do it like that”, then my head will just spin. [...]. But now there are clear instructions and I'm a part of everything, like I organize meetings and things like that. -Julie

In Julie’s example, social relations provided her with opportunities for dealing with conflicting or unclear information in her job. Because she experienced good social relations with her co-workers, she got the opportunity to address conflicting information while feeling comfortable and secure doing so. She also mentioned that her social relations at work gave her the opportunity to be a part of the things that are going on. At the time of interview, Julie felt included in every aspect of the workplace, such as staff meetings, something she had not experienced in her previous jobs.

Similar examples appeared in the accounts of other participants. At the time of interview, Josh had been working in the labor market for four years and he was an employee at a day service center for people with severe disabilities. Like Julie, Josh felt that his social relations with co-workers had been helpful and provided him with confidence to seek guidance when needed:

Yes, people are just nice. I've never experienced a workplace where people are just genuinely nice. Always prepared to help and interested in getting to know me –and because of that, when I want to, I'm more willing to ask for guidance when I'm not sure of something. -Josh

The quality of social relations and the opportunities they provide for good communication appeared as a key factor in participants’ job satisfaction and their well-being in the workplace. It also strengthened their confidence as illustrated in the accounts of Julie and Josh. They experienced being treated as equals by their co-workers without disabilities, resulting in feelings of security in the work environment and an inclination to seek guidance when needed.

However, other participants described different and more difficult experiences. These participants mentioned that when social relations were weak, this led to feelings of being an outsider, insecurity and even depression. Some participants described negative social relations in which they felt humiliated by co-workers and some experienced getting scolded for their work performance. Anne, for example, had been working as an assistant in a cafeteria, a job that she got after junior college and which she had held for 2 years at the time of interview. She mentioned that when she first started in her job, she felt pressured to master her work tasks in a short period of time. When something went wrong, instead of receiving support and guidance, Anne experienced being put in her place for making mistakes.

One of my co-workers in particular, when I just started, she said things like ‘I'm so weird’, ‘I can't do or know anything in the kitchen’. I have never worked in a kitchen before. She works very fast and she is always in a hurry, but I have never been that way. And on multiple occasions she has scolded me and things like that. And then I just feel awful afterwards. -Anne

In Anne's example, lack of understanding and of supportive social relations made her feel insecure and miserable. She experienced the support and time she got from her supervisors to learn new tasks as too limited to enable her to become competent in her job. In the absence of guidance and support that fulfilled her needs, Anne felt that her supervisor and co-workers viewed her as an incompetent worker.

In some cases, negative experiences with social relations or a complete lack of social relations led to participants’ deciding to quit their job. Emma, for example, had been working in the labor market for a decade when she decided to quit and move into sheltered work for people with disabilities. She explained that sheltered work gave her more opportunities for good social relationships in the workplace, as opposed to the labor market, where she felt it was difficult to establish social connections with her co-workers withoutdisabilities.

It is not the same. It was just difficult to find someone to connect with, because everyone else ... No one was at my age or had the same or similar background as I have. [...]. But then in [the sheltered workplace] I know a lot of people, and I've known them for a long time. -Emma

Emma’s account shows the effect co-workers lack of interest in diverse employees had on her relations with them. It should be noted that throughout the interview Emma mentioned difficulties in establishing social relations with co-workers in all jobs that she had held during a presence in the labor market of more than ten years. This explains her use of the term ‘background’ in this citation, which refers to Emma‘s experience as a person with an intellectual disability encountering barriers in the labor market.

David reported a similar experience. He had been working at a nursing home for a number of years and when it was closed, he was transferred to a similar workplace. During the interview, David described his years working at the first nursing home as a positive experience, characterized by good social relations with co-workers based on equality and trust, and work tasks and responsibilities similar to those of other employees without disabilities. David’s assistant paraphrased his account in the following way:

There he [David] was, he took care of the inventory, he had a key, they trusted him to do these tasks, and he received [responsibility over the entire] inventory and for putting everything in the right place. He was working in the kitchen, and, like I said, if somebody called in sick, he was the one to call [...] even early in the morning they would call and say “Hey someone called in sick, can you cover that?”, and it was just wonderful. –David’s assistant

When the nursing home was closed, he was transferred to a similar job at another nursing home. There, David felt alone and very few people interacted with him. When asked about his social relationships with co-workers, David and his assistant said:

David: Well, there were maybe one or two who chatted with me, but I don't know ...

David’s assistant: No, it was just very difficult. He only stayed there for a few months so he could finish work at the end of the summer, but he got very anxious about going to work. And I thought “when it has gone this bad, we just have to, well, [quit]”.

David attached much importance not only to the quality of his social relations but, interestingly, also to opportunities for making a valued contribution to the workplace and strengthening his position as an employee. In the next section we consider in more detail participants’ experiences in relation to opportunities for contributing to the goals of the organization.

3.2Valued contribution and trust

Our analysis sheds light on how the contributions our participants were able to make to their workplace played a role in their experience of work. When participants felt they had work tasks that constituted a significant contribution to the goals of the organization this made them feel like valuable and valued workers.

Participants’ had different experiences in relation to the opportunities they received for doing valued work and making a contribution to the organization. Some participants mentioned how they felt positive about being able to use their personal strengths and skills in their job. Josh, for example, worked as an instructor in a day service center for people with severe disabilities. He described how he got the opportunity to use his personal strengths and skills when providing support to clients of the center. This enabled him to bring support in line with clients’ views and experiences. Interestingly, Josh described his intellectual disability as a strength in performing his job. Josh’s experience as a person with a disability enabled him to better understand how clients feel and how they approach their environment. This gave him an advantage over his co-workers who do not possess experiences ofdisability:

I myself have a disability, atypical autism, so I understand, and I have another view on people with disabilities. How they are feeling, what they want to do ... and their thoughts. I can connect with that ... I am able to better connect to these individuals than my co-workers without disabilities who also work as instructors. -Josh

In this way, Josh was able to make a specific and valued contribution to the organization.

Other participants also mentioned their experience as a person with a disability as a strength when it came to performing their jobs and making a contribution. For example, Iris, who had been working in a library for many years at the time of interview, mentioned that being a person with a disability, she could easily establish connection and trust with children with disabilities who visit the library. She also raised attention among her supervisors to the lack of accessibility of the library for people with disabilities:

Iris: Yes, [I told them] how they could improve accessibility at the library where I was working. For the visitors.

Interviewer: And how did that go?

Iris: Very well.

Interviewer: And did they make any changes?

Iris: Yes, with an elevator [...] and now there is an elevator and [people with disabilities] can seek assistance if they need to. –Iris

These examples show how experiences of disability can be a foundation for competence and contribution. When recognized as a strength by the work environment, being able to employ disability-based knowledge and insight provided our participants with positive feelings about their position as employees within the organization and therefore a sense ofempowerment.

Receiving trust and responsibility emerged from our analysis as another important aspect of participants’ experiences in relation to making a contribution and feeling valuable as an employee. Julie, for example, explained that what she enjoys most at work is the confidence her co-workers have in her competence and the responsibility they give her. In relation to this, she also mentioned that she got opportunities for developing her professional skills.

I'm trusted with responsibility, and I'm trusted for ... like I am supervising a discussion group, we have these groups and I'm responsible for one. I get preparation time and my opinion matters. -Julie

Interestingly, Julie’s experience in her previous job was quite the opposite:

They [supervisors] didn’t trust me to do various tasks and my opinions didn’t matter. If I saw something that I disliked and I wanted to change things, it just didn’t matter [to them]. And, you know, the manager and the assistant manager were jerks. He would be constantly watching me and the clock during my coffee breaks. -Julie

Julie mentioned this to show how difficult it was for her in her previous job to make a contribution and how it negatively affected her feelings of being a valuable employee. A sense of distrust in the workplace due to their disability was also mentioned by other participants. For example, by Eric, who was working in a hardware store with employment support at the time of interview. One of the reasons for choosing this type of work was his interest in carpentry and he therefore asked for a job in the lumber department. He recalled how his supervisor did not approve of that and justified his decision by saying that it would be too dangerous for him, notwithstanding the support Eric gets on a full-time basis:

He didn’t want to send me to the lumber department, because of the traffic and stuff, cars and big work tools and stuff. He was just scared that I might get hit by a car or something. He's just making sure that won't happen, so... -Eric

Instead of an emphasis on accommodations and assistance, Eric’s experience suggests paternalism guiding his supervisor’s decision, which constituted a barrier for Eric to engage with work tasks in line with his field of interest.

These examples illustrate how access to relevant work tasks that fit with participants’ interests and competence promote feelings of being able to make a valued contribution. In relation to the content of work, participants also gave importance to being trusted to perform diverse – as opposed to a limited number of different – tasks. For example, David experienced entirely different approaches in relation to him as an employee with an intellectual disability. At the nursing home where he worked first, he had diverse work tasks and he felt that he was trusted by his co-workers. As his assistantparaphrased:

And they [co-workers and supervisors] just trusted him completely and it was just great. Just amazing. All his co-workers were great and they trusted him and let him do a lot of different tasks. –David's assistant

After the nursing home was closed and he got a similar job at another nursing home, David was trusted for few tasks:

It was like they were trying to find something for him to do, just because. Maybe, like, [impersonates supervisor] “wash this window”. And he just felt awful, because he likes having something to do, doing nothing makes him uncomfortable. -David's assistant

In what was supposed to be a similar job, David was only assigned one specific and very basic cleaning task. He was not given any of the other responsibilities that he had had before, as described under ‘social relations and belonging’. David felt he was not trusted and he no longer experience himself as an employee who actively makes a contribution to the workplace. In other words, his job had become rather empty and meaningless. The absence of trust which David experienced made him feel useless at his job, lacking any kind of meaningful or valued contribution. This ultimately led to David deciding to quit his job at the nursing home and to choose unemployment over employment.

Positive feedback from supervisors and co-workers about task performance also appeared from our analysis as an important aspect of the opportunities that participants experienced for making a valued contribution to the organization. Not only did positive feedback make participants feel good about themselves as employees, they also interpreted it as a reassurance that they were contributing something valuable to the organization. Josh explained how appreciated he feels with regular feedback:

Yes, I usually get told that I'm doing a good job and I really appreciate that. I myself like to compliment people and welcome my co-workers to work and stuff like that. And when a co-worker has been working for a while [at the workplace], I tell them that they are doing good. -Josh

As seen in Josh’s example, regular feedback, in his case in the form of compliments about his work, affected how the participants felt about their role in the workplace and it made them more positive about their experiences in the labor market. Without exception, participants described how positive feedback gave them more self-confidence and a sense of contributing as full and valued employees.

4Discussion

The aim of this empirical study was to analyze the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities in the Icelandic labor market with regard to key components in relation to work inclusion; opportunities for good social relations, belonging, valued contributions to the organization, and trust [7–9]. This study builds on the accounts of a relatively small sample of people with intellectual disabilities with diverse backgrounds and experiences of work in the Icelandic labor market. Consistent with the aim of our study and its qualitative methodology, the findings presented here are not aimed at generalizability. However, our analysis has provided in-depth insight into work inclusion as a process that takes place in the context of the workplace. This helps to better understand the ways in which work inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities takes shape and how it relates to aspects of the work organization. Such knowledge has the potential to contribute to advancing the research field and offer pathways for policy and practice to address persistent exclusion of people with intellectual disabilities from work andemployment.

4.1Social relations as a central aspect of work inclusion

The quality of social relations with co-workers emerged throughout all interviews as an important aspect of work inclusion. Good social relations were described in terms of opportunities for support from colleagues to perform in a job and confidence to seek guidance when needed. Social relations with co-workers also appeared to be important for enabling a sense of belonging. These findings resonate with a recent study about work inclusion in the context of supported employment by Gustafsson et al. [18], who described how good social support among co-workers could lead to “natural supports” in the workplace, which positively influenced conditions of social inclusion. Their study also concluded [18] that through natural support, a sense of belonging can be developed.

While our findings indicate that good social relations with co-workers may lead to opportunities for experiencing work inclusion and job satisfaction, social relations experienced by our participants as negative created barriers to inclusion, because they create difficulties in understanding job tasks, expressing needs for accommodations, or receiving support. Difficult social relations also involved ‘othering’ of the person with a disability [24], and devaluation against the benchmark of the ‘ideal employee’ [25]. This in turn affected their experiences of developing a sense of belonging to the work organization. The potential impact of negative social relations can be summarized as a pathway to exclusion within the workplace and our findings further explain processes of exclusion that have previously been marked as important in empirical studies about employment participation of people with disabilities in general [e.g. 24] and people with intellectual disabilities in particular [e.g. 14]. This study also lends further support to the observation made by Kulkarni et al. [39] that when it comes to inclusion of people with disabilities in work, the role of co-workers is most influential. In order for people with disabilities to experience being ‘real employees’ who belong in the organization like all other employees, social relations with diverse employees need to be carefully considered.

While our study does not suggest any order of priority of basic components of work inclusion, social relations appeared as important in itself and in relation to other basic components. This is reflected in the observation that experiences of exclusion related to negative social relations in the workplace in some cases result in people with intellectual disabilities giving up on work inclusion in the regular labor market altogether and turning to segregated activities such as sheltered work. Our findings show that this could be explained by their experiences of emphasis on good social relations in segregated settings, making these settings more attractive in the face of barriers to social relations in the regular labor market.

4.2Valued contribution and trust

Valuation of work [9] – in combination with trust – emerged from our study as an important component of work inclusion that connected different aspects within participants’ experiences. Our findings show the importance for work inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities of being able to perform tasks which are relevant to the goals of the organization and which appeal to their interests. When, on the other hand, our participants experienced that their work tasks were pointless or well below their skill levels, they felt like useless employees who do not bear any value to the organization. In other words, having the opportunity to perform valued tasks with a large degree of autonomy [see also 40] and bear responsibility for one’s role in the organization was experienced as a key aspect of inclusion, leading to employees with intellectual disabilities being able to employ their skills and personal strengths. Interestingly, this included specific knowledge related to being disabled in the world, which in some cases enabled our participants to make unique contributions to the organization. In addition, valuation of their work roles and responsibility appeared to be related to empowerment, by creating opportunities for individuals with intellectual disabilities to consciously develop goals and ambitions in their careers. Valuation thus emerges as a key condition to enable people with intellectual disabilities to manage their jobs and careers through different strategies such as those described by Jammaers et al. [28] and Kulkarni et al. [27].

Closely related to responsibility was the importance of trust as a key aspect of participants’ experience of work in the labor market. Being trusted to perform work roles appeared to lead to feelings of being equal to co-workers without disabilities and gave our participants confidence to perform tasks and develop their work roles. As opposed to trust, paternalism and distrust regarding the ability to perform tasks was experienced as a barrier to feeling valued and making a relevant contribution to the work tasks, resulting in feelings of uselessness and exclusion.

4.3Implications for research, policy and practice

The concept of work inclusion being part of article 27 of the UNCRPD [21] provides a basis for development of new policy and practices which requires knowledge development about existing practices through research. Addressing different types of productivity in work inclusion, Hall et al. [41] and Lysaght et al. [17] have pointed out that work in the regular labor market as it is experienced by people with disabilities, in this day and age, may not always entail opportunities for inclusion. When work in the labor market induces feelings of uselessness and even being intimidated, as we found in our study and also discussed by Hall [14], people with intellectual disabilities may decide to self-exclude within their jobs, by quitting their jobs or leaving the labor market altogether [14]. This does however not constitute an argument for or against certain work settings. Indeed, the work inclusion lens applied in this study avoids such oversimplification in our understanding of the potential for work inclusion of regular and segregated settings. With regard to social relations, a study by Hall et al. [8] suggests that people with intellectual disabilities experience social relations within employment as conducive to opportunities for inclusion that are not available in segregated settings. Likewise, our study provides further illustrations of the interrelatedness of quality of social relations, belonging, valued contributions and trust in the work experiences of people with intellectual disabilities. These insights underline the merit of a work inclusion approach that involves multiple basic components for generating knowledge about the ways in which opportunities for work inclusion are created in different work environments. In doing so, a work inclusion approach contributes insight into inclusion as a process and lived experience that takes into account the context of the workplace.

Our study findings also have implications in terms of policy and practice in the labor market. Having a paid job does not guarantee work inclusion and social relations emerge from our study as a matter of priority. Therefore, it can be argued that labor market measures such as supported employment should emphasize supporting social relations of good quality in the workplace. This implies attention to relations that foster trust, feelings of belonging and valued contributions to the organization. In a recent study, Hardonk et al. [20] have demonstrated how high case load and a lack of available resources result in job counsellors in supported employment in Iceland not being able to provide follow-up support in such a way that it assists in making the organization more inclusive. A similar emphasis on placement has been suggested in other studies as well [9, 42] and is likely to limit the potential for work inclusion, especially knowing that social relations are not built in one conversation between support professionals, people with intellectual disabilities and their co-workers and supervisors. Our study provides further ground for developing and implementing labor market measures that target organizations as a whole – not only people with intellectual disabilities – and for longer periods of time to achieve the aim of facilitating work inclusion.

Based on our findings we argue that corporate culture needs to be considered in order to avoid barriers to inclusion and instead actively create opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities. As Schur et al. [23] have pointed out, corporate cultures that rest on expectations of able-bodiedness result in barriers in terms of hiring, work processes, social relations and the accessibility of the work environment. Our study shows how this is experienced by people with intellectual disabilities and suggests that to avoid these barriers organizations need to recognize the interrelatedness of different components of work inclusion [9] and their relation with corporate culture in the creation of barriers and opportunities for work inclusion. We argue that human resource managers, co-workers, supervisors and support professionals need to consider work inclusion not as a special project but rather an approach to be mainstreamed in corporate culture. Scholars have in this regard demonstrated the potential of practices such as ‘job crafting’, which takes diversity into account as a basic organizing principle and improves the position of workers with disabilities [43].

In terms of the consequences of expectations of able-bodiedness in corporate culture for work inclusion [23], our study findings show how corporate culture in which intellectual disability is approached from a perspective of pity and compassion may be detrimental to work inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities. Such approaches, while seemingly benign, reflect stereotypically low expectations and lack of trust in the skills and aspirations of people with intellectual disabilities. Our findings thus shed light on how people with intellectual disabilities experience barriers to being included as employees because of two aspects of corporate culture, on one hand the ‘norm to be kind’ [29] that limits expectations towards employees with disabilities and promotes tokenistic hiring, and on the other hand organizational discourses that limit opportunities of people with disabilities for developing their professional identities [30]. However, our findings also point towards ways in which the work environment can be supportive and achieve relations in which people with intellectual disabilities experience trust and recognition [see also 32].

5Conclusion

The work inclusion approach that underlies this study offers a constructive approach to better understand the perspectives on employment participation of people with intellectual disabilities themselves. Our findings encourage not only further research related to the basic components of work inclusion and their interrelatedness, but also – and not least – the development of labor market measures and human resource practices that rest on an active engagement with the work environments in which people with intellectual disabilities participate.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the University of Iceland Research Ethics Committee on 15 November 2018 (nr. 18-031).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of the research project ‘Rethinking work inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities’ funded by the Research Council of Norway (‘HELSEVEL’ 2018–2021, grant number 273259).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants in this study for their contributions. They also wish to thank the organizations for people with disabilities and self-advocacy groups that assisted in reaching out to potential participants.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed to study design, data collection, and analysis. Interviews were conducted by the first author. Both authors collaborated on data analysis and writing up of findings, and approved the final manuscript.

References

[1] | OECD. Sickness, Disability andWork: Breaking the Barriers: OECD; 2010. |

[2] | European Union. Employment of disabled people. Statistical analysis of the 2011 Labour Force Surveyad hoc module. Luxembourg: European Union; 2015. |

[3] | Statistics Iceland. Staða örorkulífeyrisbega á vinnumarkaði (2019) [Available from https://hagstofa.is/utgafur/frettasafn/vinnumarkadur/oryrkjar-a-islenskum-vinnumarkadi/ |

[4] | Lysaght R , Ouellette-Kuntz H , Lin CJ . Untapped potential: perspectives on the employment of people with intellectual disability. Work. (2012) ;41: (4):409–22. |

[5] | Friedman C . The relationship between disability prejudice and disability employment rates. Work. (2020) ;65: :591–8. |

[6] | Fyhn T , Sveinsdottir V , Reme SE , Sandal GM . A mixed methods study of employers’ and employees’ evaluations of job seekers with a mental illness, disability, or of a cultural minority. Work. (2021) ;70: :235–45. |

[7] | Cobigo V , Ouellette-Kuntz H , Lysaght R , Martin L . Shifting our conceptualization of social inclusion. Stigma research action. (2012) ;2: (2). |

[8] | Hall AC , Kramer J . Social Capital Through Workplace Connections: Opportunities for Workers With Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation. (2009) ;8: (3-4):146–70. |

[9] | Lysaght R , Cobigo V , Hamilton K . Inclusion as a focus of employment-related research in intellectual disability from to A scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation. (2012) ;34: (16):1339–50. |

[10] | Barnes C . A working social model? Disability, work and disability politics in the 21st century. Critical social policy. (2000) ;20: (4):441–57. |

[11] | Oliver M , Barnes C . Disability studies, disabled people and the struggle for inclusion. British Journal of Sociology of Education. (2010) ;31: (5):547–60. |

[12] | Abberley P . Work, utopia and impairment. Disability and society: emerging issues and insights. Longman sociology series. Harlow, UK: Pearson education limited; (1996) . pp. 61–79. |

[13] | Shier M , Graham JR , Jones ME . Barriers to employment as experienced by disabled people: a qualitative analysis in Calgary and Regina, Canada. Disability & Society. (2009) ;24: (1):63–75. |

[14] | Hall E . Social geographies of learning disability: narratives of exclusion and inclusion. Area. (2004) ;36: (3):298–306. |

[15] | Stone DL , Colella A . A Model of Factors Affecting the Treatment of Disabled Individuals in Organizations. Academy of management review. (1996) ;21: (2):352–401. |

[16] | Williams J , Mavin S . Impairment effects as a career boundary: a case study of disabled academics. Studies in Higher Education. (2015) ;40: (1):123–41. |

[17] | Lysaght R , Petner-Arrey J , Howell-Moneta A , Cobigo V . Inclusion Through Work and Productivity for Persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. (2017) ;30: (5):922–35. |

[18] | Gustafsson J , Peralta J , Danermark B . Supported Employment and Social Inclusion – Experiences of Workers with Disabilities in Wage Subsidized Employment in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research. (2018) ;20: (1):26–36. |

[19] | Jahoda A , Kemp J , Riddell S , Banks P . Feelings about work: A review of the socio-emotional impact of supported employment on people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. (2008) ;21: (1):1–18. |

[20] | Hardonk S , Halldórsdóttir S . Work Inclusion through Supported Employment? Perspectives of Job Counsellors in Iceland. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research. (2021) ;23: (1):39–49. |

[21] | Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, (2007) . |

[22] | Gewurtz R , Kirsh B . Disruption, disbelief and resistance: A meta-synthesis of disability in the workplace. Work. (2009) ;34: (1):33–44. |

[23] | Schur L , Kruse D , Blanck P . Corporate culture and the employment of persons with disabilities. Behavioral sciences & the law. (2005) ;23: (1):3–20. |

[24] | Mik-Meyer N . Othering, ableism and disability: A discursive analysis of co-workers’ construction of colleagues with visible impairments. Human Relations. (2016) ;69: (6):1341–63. |

[25] | Foster D , Wass V . Disability in the Labour Market: An Exploration of Concepts of the Ideal Worker and Organisational Fit that Disadvantage Employees with Impairments. Sociology. (2012) ;47: (4):705–21. |

[26] | Colella A , DeNisi AS , Varma A . The impact of ratee’s disability on performance judgments and choice as partner: The role of disability–job fit stereotypes and interdependence of rewards. Journal of Applied Psychology. (1998) ;83: (1):102. |

[27] | Kulkarni M , Gopakumar KV . Career Management Strategies of People With Disabilities. Human Resource Management. (2014) ;53: (3):445–66. |

[28] | Jammaers E , Zanoni P , Hardonk S . Constructing positive identities in ableist workplaces: Disabled employees’ discursive practices engaging with the discourse of lower productivity. Human Relations. (2016) ;69: (6):1365–86. |

[29] | Colella A , Varma A . Disability-Job Fit Stereotypes and the Evaluation of Persons with Disabilities at Work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. (1999) ;9: (2):79–95. |

[30] | Jammaers E , Zanoni P . The Identity Regulation of Disabled Employees: Unveiling the ‘varieties of ableism’ in employers’ socio-ideological control. Organization Studies. (2021) ;42: (3):429–52. |

[31] | Nota L , Santili S , Ginevra MC , Soresi S . Employer Attitudes Towards the Work Inclusion of People With Disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. (2014) ;27: (6):511–20. |

[32] | Lindstrom L , Hirano KA , McCarthy C , Alverson CY . Just Having a Job” Career Advancement for Low-Wage Workers With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals. (2014) ;37: (1):40–9. |

[33] | Hall E . Spaces of social inclusion and belonging for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. (2010) ;54: (1):48–57. |

[34] | Meekosha H , Shuttleworth R . What’s so ‘critical’about critical disability studies? Australian Journal of Human Rights. (2009) ;15: (1):47–75. |

[35] | Hennink M , Hutter I , Bailey A . Qualitative research methods. London: Sage Publications Ltd.; (2009) . pp. 304. |

[36] | Charmaz K . Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage; (2014) . pp. 388. |

[37] | Charmaz K . Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In: DenzinNK, LincolnYS, editors Strategies of qualitative inquiry (2nd edition). Sage; (2003) . pp. 249–91. |

[38] | Cresswell JW , Poth CN . Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches (4th edition). London: Sage Publications; (2018) . |

[39] | Kulkarni M , Lengnick-Hall ML . Socialization of people with disabilities in the workplace. Human Resource Management. (2011) ;50: (4):521–40. |

[40] | Jones MK , Sloane PJ . Disability and Skill Mismatch. Economic Record. (2010) ;86: :101–14. |

[41] | Hall E , Wilton R . Alternative spaces of ‘work’ and inclusion for disabled people. Disability & Society. (2011) ;26: (7):867–80. |

[42] | Bonfils IS , Hansen H , Dalum HS , Eplov LF . Implementation of the individual placement and support approach–facilitators and barriers. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research. (2017) ;19: (4):318–33. |

[43] | Sundar V , Brucker D . “Today I felt like my work meant something”: A pilot study on job crafting, a coaching-based intervention for people with work limitations and disabilities. Work. (2021) ;69: :423–38. |