What inhibits the progress of early-career women in Karachi? Studying the effects of socio-spatial mobility barriers on women’s employment

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

There is a widespread acceptance and shift towards sustainable, inclusive and smart mobility solutions around the world. However, in Karachi, poorly coordinated urban planning, lack of effective governance structure and investment in transport, has allowed the growth of an almost unregulated and ungovernable informal transport sector. Women are more severely affected by the poor service since men not only have more space allocated to them on public transport but also have the freedom to use alternative and cheaper private vehicles such as motorbikes and cycles. Poor representation of women in the transport sector further aggravates the situation.

OBJECTIVE:

The paper aims to highlight the gender-disaggregated effects of poor transport design, provision and lack of personal agency on mobility, for emphasising the social and cultural attitudes faced by female employees. It argues that not integrating the gender-based disadvantages faced by women into planning, reinforces their disadvantaged position and force them to take complex trips.

METHODS:

Scenario-based questions were designed for focus group discussion which covered not only the everyday mobility challenges but also their reactions to the potential solutions. For a gender-based comparative analysis, two separate focus group discussions were organised.

RESULTS:

Adopting a sector-based mapping approach of the issues discussed in the groups helped understand the complexity of female user experience at various levels, starting from planning or discussing the trips with families, to making modal choices. It also helped to tease out the impact of these issues on their employment opportunities as early-career women.

CONCLUSION:

The model proposed in this paper can help illustrate where changes can be made in the system considering the social aspects of transport.

1Introduction

Women’s representation in Pakistan’s formal employment sector is extremely poor as evident in the labour force participation rates (2017) with only 79% of men and 26% of women formally employed [1]. Although half of the country’s population is female [2], women are generally underrepresented in all sectors except agriculture. Rural women dominate this field since a large majority of them work as cotton pickers in the fields [3]. According to an estimate, 40% of women in Pakistan do not enter into paid employment due to restrictions imposed by their families [4]. Male dominance of all employment fields compromises the career advancement of women as most of the influential positions are occupied by men, and no one discusses or champions the needs of women. Likewise, the transport sector is heavily male-dominated [5] across Pakistan, including Karachi. This paper considers the relationship between gender transport poverty and the employment of young women in Karachi.

The paper argues that integrating the socio-cultural issues faced by women in all areas of transport can help women increase their socio-economic capital. Studies in the transport domain have examined social factors before, but little attention has been paid to the unique gender-based dynamics in the global South. The current study tries to fill this gap by focusing on the barriers faced by employed women advancing their careers in Karachi using a feminist phenomenological approach, which empowers respondents’ voices and offers a critical understanding of their lived experiences.

1.1Aims and objectives

The paper aims to understand the concept and impact of transport poverty to help towards achieving these development goals. The key objective is to contribute insights into the effects of poor transport design, provision, and lack of agency on mobility, for emphasising the social and cultural attitudes faced by female employees.

1.2Literature review

The paper is a part of wider research to address Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Goals 1, 5, and 11 which focused on poverty, gender, and sustainable urban development are of key interest. The progress in achieving various goals is not substantial, and it is particularly lagging behind in achieving gender equality and poverty [9]. Another key area of development, where Pakistan has displayed poor progress is with regard to fostering gender equality, in line with SDG 5. As a result, the country scored 48.9 on the 2019 SDG Gender Index, and it stood at the lowest position among other Asian Countries [10]. This was despite the fact that Pakistan is a signatory of many of the international treaties to safeguard human rights and to minimise gender discrimination [11], including the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Conventions, but there have been no attempts to overcome the gender wage gap in the country [12], which requires substantial legislative backing and institutional implementation. Thus, there is a need to unlock the debate on the bottlenecks to achieve the UN goals, particularly 1 and 5, as well as make policy changes accordingly. The discussion here will allow looking at the ways transport poverty could be studied and mitigated for achieving SDGs in the context of the global south.

Likewise, in present-day Karachi, a multi-dimensional, gender-inclusive approach to understanding and translating women’s travel patterns in policymaking is largely missing [13]. This is because the body of literature on transport in the context of Pakistan does not bring into focus the gender-based needs of transport users, which therefore fails to tap the potential of improved mobility in achieving SDGs. Khan argues that it is important to understand that a significant obstacle to women’s participation in the workforce is the enforcement of ‘purdah’ (i.e. veil and gender segregation) which ‘is linked more closely with male domination over women’ [14]. Purdah is used to not only seclude women and redefine the use of public space but also to shape the ‘underlying attitudes of society’ [15]. It symbolically displays the rigidity of gender norms that try to make women invisible in the public arena since their freedom or empowerment is considered a negative trait and is linked with shamelessness [16]. Studies on the impact of social norms on women’s use of space as well their mobility have shown that their seclusion or physical confinement can cause their exclusion since their mobility is severely affected by an ideological connection between their purity and immobility, making them additionally vulnerable to poverty [5].

A few recent studies have focused on the politics of mobility in the context of gender-based seclusion too. Inflicting immobility on women is considered a way to ‘keep women in a subordinate position’ or ‘sustain gender traditional gender relations’ [13]. However, such social behaviors constructing gender are mostly overlooked in the existing literature on transport, as a result, a very narrow understanding is displayed in ill-guided assumptions made after a household study conducted by JICA (2012). It has thus attributed women’s lower mobility in Karachi with religion [17] without recognising the complex set of disadvantages faced by them. Recognising the mobility challenges faced by women that make them additionally disadvantaged and understanding the complex relationship between gender and mobility remains under-theorised [8]. For example, although vehicle ownership is lower among women in Pakistan and therefore, the lack of public transport can automatically disadvantage more women than men, however, there are gaps in the literature to highlight these relationships. Uteng and Turner have also reported the additional complexity of theorising gender issues with regard to development and transport in the global South, ‘which does not have a strong quantitative data collection and analysis tradition’ [18].

1.2.1Background

The transport system does not support the spatial distribution and spread of livelihood opportunities for such an ever-expanding city like Karachi. There are a limited number of buses, most employees in Karachi are subjected to some form of transport poverty even if they own a private car or can use private forms of transport approximately 8000 buses serve a city of 23 million people [13]. This is because the road-based public transport system forms 4.5% percentage of the total vehicle fleet in Karachi, with a small number of buses/minibuses serving 42% of passenger demand [19], with paratransit vehicles such as qingqi and rickshaws making up some of the shortfalls.

Typically, buses accommodate 50 passengers with 10 seats allocated to women (Saleem 2019). The fares for large buses in Karachi are Rs.10 for 5 km, Rs.15 for 10 km and Rs.17 for 15 km distances [5]. Rickshaws are hired privately from the roadsides and can accommodate up to 3– 5 passengers, depending on size [4] and are more open in design. Fares are arbitrarily decided while additionally, Careem is a locally run Uber-like ride-hailing car service, enabling customers to use smartphones to book a ride [20]. The charge is Rs. 13 to Rs. 25 per kilometre depending on the car, along with a minimum base fare of Rs. 80 (ibid). Private cars and motorcycles, form roughly 84% of all vehicles and, provide transport for 40% of the total passengers [20], where men significantly outnumbering women in terms of vehicle ownership in both cases. According to Adeel [13], compared with men, Pakistani women make 1.6 fewer socio-cultural trips (0.8 vs. 2.4) and 1.2 fewer work trips (0.7 vs. 1.9). The total daily travel duration of women is also 31 minutes shorter for socio-cultural travel (17 minutes vs. 48 minutes) and 25 minutes shorter for work travel (19 minutes vs. 44 minutes) [13]. For women, not only is the frequency of their work and non-work trips, but the duration of their journeys is also lesser than men. Women’s movements outside the homes, are not only subject to familial and socio/cultural restrictions but also impeded by poor transport provision and gender bias which, as argued in this paper, impacts their career trajectories. This meant that for a typical man, his commute might be comparably much simpler, whereas women had to consider their safety, social acceptability, and temporal restrictions. As a consequence, they may remain dependent on male family members for their trips and have little autonomy [19]. The layers of disadvantages caused by their intersecting identities display the struggles faced by educated and capable early-career women.

Thus, the socio-economic and cultural milieu of the city suggests that there is a need to adopt a holistic model for understanding transport-related difficulties faced by women in Karachi. there is thus a need to conceptualise transport in a holistic way that can help recognise its role in achieving the UN goals. The phenomenon of transport poverty can help to bring a new perspective that may be considered a holistic concept, including the financial, spatial, personal and temporal constraints [21]. For Lucas, transport poverty is a combination of social and transport disadvantages, and a blend of social norms and practices, economic and political structures, governance and decision frameworks work together to create an enduring cycle of transport poverty [22]. This can be relevant in the context of Karachi where gender and other inequalities may exist, which differentially affect levels of social disadvantage [23]. This disadvantage can thus be unevenly distributed and can account for other inequities [24] while poor transport can worsen these conditions.

2Materials and methods

2.1Research design and methods

With this in mind, the research has adopted a phenomenological approach guided by interpretive inquiry to study the phenomenon of transport poverty experienced by middle-income women in Karachi. Phenomenology allows understanding lived experiences and can challenge the objectivity in the existing theoretical assumptions surrounding a phenomenon [25]. In particular, interpretive phenomenology recognises that knowledge is contained within the perspectives of people [26]. The use of interpretative phenomenology has thus allowed giving a voice to the participants and their individual experiences to inform the current research. It also allowed the mutual construction of reality, shared by both the researcher and the researchparticipants.

Phenomenological focus groups were organised which not only enrich the data but can also be used to validate responses as participants reflect on their experiences while sharing them with the group. Twenty-two scenario-based questions were designed around issues that could arise during part of work or non-work trips, were used to understand decision-making in relation to various situations and real-life dilemmas. These questions were used in the group discussion to help participants think about and verbalise how they would respond in different potentially sensitive situations [27]. They were designed to understand the lived experiences of participants by asking them to react to a hypothetical situation designed to reflect real-life dilemmas [28]. The scenarios were related to typical travel issues that could occur as part of work or social activities and were used to understand mobility-related decision-making. For example, coming back from work at night or walking alone from the bus stop to home.

Each scenario was designed in a way that the participants could relate to the situations and were as realistic as possible. However, apart from understanding their preferences/attitudes regarding existing modes of transport, a few questions were also asked to understand their perceptions regarding possible alternatives or improvements such as the installation of surveillance cameras on bus stops. These scenarios helped to understand the importance of such improvements on participants’ perceptions of safety and hence see the effects of changes on their modal choices.

Single-sex focus group discussions were conducted to further draw out the gender-based comparison. Homogenous gender groups can help with the free exchange of ideas and experiences since they afford a sense of safety to the participants [29]. This grouping approach allowed them to feel more comfortable talking about the issues that they face since they were accompanied by those who might be facing similar mobility constraints as them based on their affiliation with middle-income groups and gender. The number of participants was set, keeping in mind both the need to acknowledge individual voices as well as to allow the exploration of themes in a group setting. The ideal size of a focus group is between five and eight [30]. Since there were more than 20 scenarios, the number of participants were kept to 6 to control the duration of the discussion [31].

The FGD respondents shed light on the scenarios by relating them to their real-life experiences and making connections with the context. Thus, this approach allowed an understanding of the social construction behind mobility-related aspects. The discussion with female participants was moderated by the researcher while a male colleague conducted the one with men ensuring a balanced power relationship between researchers and participants. He was suitably trained in research methods and aware of the aims and objectives of the research.

Sampling and Recruitment: Purposive sampling was used to recruit, six early-career women and men (aged between 21 and 35) with current or prior experience of using public transport. They belonged to different professions but shared similar gender and socio-economic status. Background information was collected for each participant relating to age, profession, location, and transport usage (see Tables 6.2 and 6.3). The sample was composed of early-career men and women in Karachi from middle-income families, which is justified in light of the unique challenges faced by them. The middle-class in Pakistan thrives at their utmost for upward social mobility through good education and striving hard with job opportunities [6]. Nevertheless, women in this group are also subjected to additional restrictions due to class-based norms around their presence in public spaces. Women’s lack of visibility and work outside the house is considered a matter of pride for these families [7]. As a result, they tend to work part-time or engage in employment that does not require a full-day time commitment, in occupations that are considered ‘suitable’ for example, teaching [8].

2.2Ethical approval

The research was submitted for the medium-high risk category of the Coventry University Research Ethics Approval System. It was by the ethics committee after a careful evaluation of all the risks involved with researching in Pakistan. To be General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant, the research participants were informed about the research prior to the FGD and were asked for written consent. Participant Information Sheets were also distributed for the same purpose in English and Urdu.

2.3Analysis

Thematic analysis was performed using NVIVO (version 12.1.1) not only to see the spread of codes/ values in a group/case but also to compare these across the two groups. Apart from developing a codebook, there were some features of NVIVO that also helped in understanding the most evident differences in perspectives of men and women. For example, the matrix coding query in NVIVO helped in understanding the extent and frequency of a certain code across the data. Thus gender-based comparisons could be made using the crosstab query, which is a quick way of checking the spread of coding across the different cases using NVIVO. The comparative analysis highlighted the gender-based differences in attitudes, preferences and behaviours especially in relation to journeys made for employment and education. The analysis revealed that the options/choices at the disposal of female participants were more limited than those of male participants. Therefore, this paper focuses on understanding the barriers faced by women, and how these impact their employment.

2.3.1Participants characteristics

The participants belonged to a variety of professions and were living in different parts of Karachi. Their ages ranged from 22– 37 years, as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1

Profiles of female participants (FGD1)

| Name | Age | Profession | Mode of transport | Duration of commute to work |

| A1 | 30 | Lecturer | Vans | 2 hrs |

| A2 | 28 | Event planner | Public transport | 2 hrs |

| A3 | 22 | Nurse | Bus | 1 hr |

| A4 | 29 | Textile designer | Careem1 | 2.5 hrs |

| A5 | 37 | Career counsellor | Rickshaw2 | 1.5 hrs |

| A6 | 35 | Project manager (DHA) | Personal car | 50 mins |

1Local version of Uber. 2A three-wheeler paratransit vehicle famous in South Asian countries.

Table 2

Profiles of male participants (FGD2)

| Name | Age | Profession | Mode of transport | Duration of commute |

| to work | ||||

| B1 | 28 | Chef | Bus | 1 hr 45 mins |

| B2 | 27 | IT professional | Bikes through ride-hailing apps | 1 hr |

| B3 | 35 | Teacher | Rickshaw | 50 mins |

| B4 | 30 | Banker | Coach | 1 hr |

| B5 | 24 | Sales executive | Bus and Qingqi | 2.5 hrs |

| B6 | 30 | Administrative secretary | Personal bike | 45 mins |

The profiles of participants show that more men than women were dependent on public transport and that women could not use bikes; their average length of commute was longer. The average length of distance travelled by women was slightly higher for women than men. The literature also suggests that women and men in Pakistan have different mobility patterns and modal choices [13]. The findings from the online survey concurred with those of Hasan and Raza [20] regarding the modal split between genders with women’s journeys being more reliant on the on-demand hired services (42%) than men’s (12%), who were more dependent on motorbikes. Although motorbikes served as an affordable option for middle-income men [32], women were discouraged from using transport modes that can expose their bodies or require them to sit astride motorbikes, which is considered immodest [33].

2.3.2Theoretical framework

Creswell defines mobility as ‘a socially produced fact of life’ and also emphasises the importance of mobility to enhance social capital and freedom [34]. This view is also held by Woodcock [35] for whom the use of transport should also be considered a social act or exercise. Apart from recognising the social aspects of mobility, a social constructionist view in mobility supports intersectionality, by identifying how gendered experiences are also shaped by age, sexuality, class, and ability of women [36]. Thus, an intersectional approach can help in embracing not only its social dimension but also helping to conceptualise mobility as a subjective or disproportionally distributed resource. Since mobility and gender can influence power relations in society, there is a need to understand gendered meanings and power relations embedded in various forms of mobility and immobility, that varies with different social and geographical contexts [23].

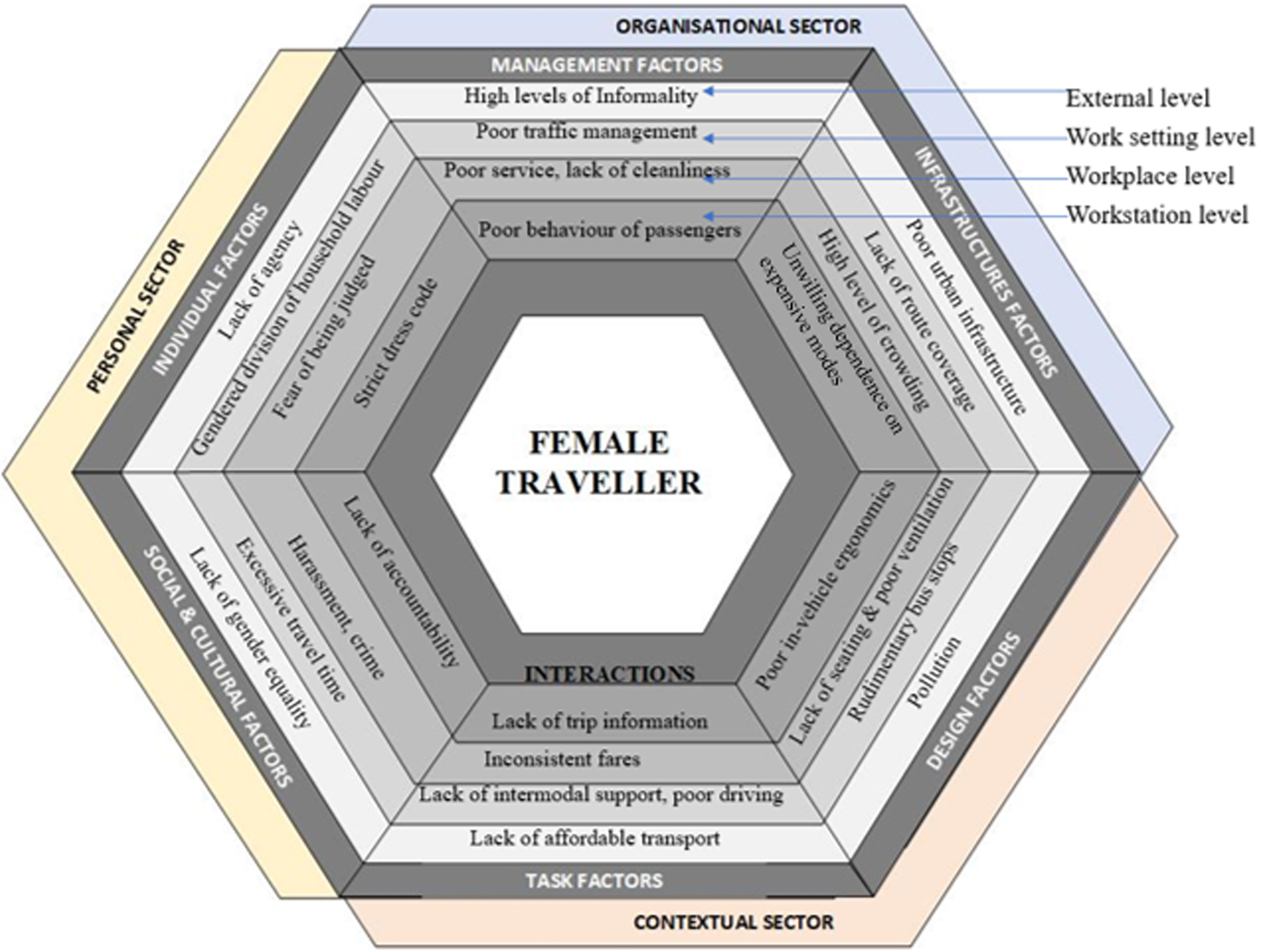

With this understanding, the Hexagon-Spindle (H-S) model is based on the ergonomic principle of making design and systems better for the group who face the most complex challenges so that everyone can benefit from them [37]. In terms of its application to transport, the overarching task for travellers may be considered to be getting from their origin to destination as efficiently and safely as possible, with obvious sub-tasks such as getting a ticket, boarding a vehicle. Woodcock [35] has used the H-S model to provide a framework for the development of person-centred approaches to transport design, both vehicular as well as system. The model can provide a systematic division of factors that influence travel experience for transport users. This holistic perspective covers all parts of multi-modal journeys from planning to arrival at destination [38]. Adapted from the concentric rings model, the model distinguishes between factors at the;

• External or Transport environment level-Culture

• Work setting level- Design of stops and station

• Workplace level- Quality of ride

• Workstation level- In-vehicle ergonomics and

• Traveller interaction level [38].

Woodcock [39] applied the model to the whole journey end to end experiences of passengers in the Measurement Tool to determine the quality of Passenger experience (METPEX) project. She argues that an issue occurring at any stage of the journey will lead a passenger to abandon or rethink their journey [38]. Thus, focusing on the key stages of a person’s trip, this model can also help to understand the role of individual, social and cultural, task and design factors [38:60].

The model also allows space for the consideration of personal factors (individual and social and cultural factors) that can influence the user’s experience and cause transport poverty. This sector has not been fully explored, as the model has only been applied in an EU transport context where these issues were not singled out as a high priority issue [38]. Clearly understanding the effects of these factors would broaden and deepen the model. It will also allow looking at the ways transport poverty could be studied and mitigated for achieving SDGs in the context of the global South. In the context of this research, the model can help illustrate where changes can be made in the system considering the social aspects of transport and broader context to reduce transport poverty. It classifies and maps the issues during different stages of user experience from workstation to the wider external environment in three key sectors namely: personal (socio-cultural and individual factors), contextual (task and design factors) and organisational (management and infrastructure factors).

This classification makes it possible to integrate the impact of socio-cultural factors on the mobility of people. The model thus allows space for the consideration of personal factors (individual and social and cultural factors) that can influence the user’s experience and cause inaccessibility. This sector has not been fully explored, as the model has only been applied in an EU transport context where these issues were not singled out as a high priority issue [38]. Clearly understanding the effects of these factors would broaden and deepen the model.

The model also supports the intersectional approach in working on the people with the most challenging needs. In this case, solutions put forward to help women’s (mobility) needs can benefit all transport users. The model starts in the centre, emphasizing the user’s interaction with different parts of the system, for transport this could be the design of seats, bus stops, transport infrastructure, fellow passengers etc [39]. The female traveller is placed at the center of a model and their interactions with different parts of the system, such as the bus stops, vehicles, passengers are documented. This allows representation of all possible factors from micro-interactions through to wider societal and external factors governing transport operation.

Since the focus of the study is on early-career women, adopting a sector-based mapping approach of the issues can help understand the complexity of female user experience at various levels, starting from planning or discussing the trips with families, to making choices to reduce social stigma associated with public transport usage. In Fig. 1, the end-to-end journey experiences of the female traveller have been mapped onto different sections of the transport system to cover factors from the workstation level to macro-level issues as well as to unpick the relationships between various factors. The diagram shows that many factors can affect the usage of the system – these are represented in the different layers and segments of the model. This way it helps to include less-discussed aspects of women’s mobility and integrate these in the discourses on transportpoverty.

Fig. 1

Mapping the issues faced by a female traveller onto the H-S model.

3Results

The research generated many findings relating to gender transport poverty as experienced by early-career women in Karachi, as reported in [40]. In this paper, those results which relate to the way in which transport affects women’s employment choices are prioritised. In general, it was seen that the opportunity to take up employment is not a guaranteed right or expectation for women in Karachi. Permission to work has to be negotiated within the family and may come with certain caveats regarding what occupations can be undertaken, where, when and how to travel to preserve honour and safety.

3.1Level-based division of issues

In the following sections, the results will be discussed in terms of levels (going from the outside in) and then using sectors. The discussion is divided into four parts starting with macro-level issues first followed by work setting, workplace and work station:

3.1.1External

The informal sector currently dominates transport governance and operation in Karachi. In most cases, public buses are owned by individual financers, transport staff and operators who are untrained and use their personal links to gain permits for bus routes [5]. As a result, most drivers are untrained and enjoy unchecked rights. These private bus owners can create services on their own terms, being given exclusive rights to schedule the bus timings [41]. Apart from the issues around the organisation of transport in Karachi, other external factors include extreme poverty and pollution.

3.1.2Work setting

Transport management and regulation is a significant issue [42]. The overlapping and segmented governance structure in Karachi [43], has invited corruption due to the lack of accountability [44]. The different transport agencies operate in silos with no coordination amongst themselves. Although these bodies are operating at different levels, there is no coordination between them, which has weakened the institutions, allowing corruption [45]. Corruption is therefore rampant in the transport sector and is negatively correlated with economic growth [44]. In this environment, the informal transport economy in Karachi uses bureaucratic corruption to get things done and often ‘bribes in money and kind are used to bypass or bend government rules’ [46].

The lack of regulations, the poor concern of drivers for passenger safety and lack of traffic management combined create conditions where people put themselves at risk. From the FGD, all of the women and 33% of men were affected by the poor safety caused by the ineffective enforcement of traffic regulations.

3.1.3Workplace

With little planning and few transport-related policies, there has been a growth in informal bus services; individual financers own each bus, which has crippled technological advances [47]. Apart from inadequate vehicles, the road infrastructure is also poor. Uneven and damaged road surfaces are common, with open potholes posing a safety risk for both pedestrians as well as other road users [42]. Pedestrian infrastructure in the form of crossings and signals are also missing, and most of the pavements are also unmaintained [47]. This causes extreme difficulties for older people who cannot access the raised walkways and stepped bridges [48].

Other infrastructure problems are related to non-functional or missing traffic signals, and lack of bus stops, terminals and rickshaw/qingqi depots [49]. Ilyas [50] concluded that flawed road designs led to risky U-turns, which were responsible for about 35% of the total road accidents each year. From the FGD, 77% of women and 83% of men shared that the existing public transport has very limited network coverage which does not allow them to reach their destinations easily. Women interviewees reported taking extended, unsafe and tiring journeys due to the lack of intermodal support when travelling on multiple modes.

3.1.4Work station

Without checks for vehicle roadworthiness, bus drivers do not have to maintain their buses [20] which run without ‘proper seats, with deformed bodywork (and) no windowpanes’. Although the required protocol of allocating a separate compartment for women was upheld, this was done without any attention to their needs. They were given the worst seats and women’s section was located close to the driver, with some seats situated over or near to the bus engine making them too hot to be occupied. Those seated on the engine had no room for their legs. This led to discomfort which together with the overcrowding and high temperatures was both fatiguing and biomechanically hazardous. There is no specification of how seats should be allocated to women. This is indicative of the belief that their place on public transport was barely tolerated and they are unwelcome in the public realm.

Additionally, no provision was made for the fact that women are more likely to have luggage or be accompanied by small children when they fulfil their cultural duties as caretakers. In the absence of luggage space and comfortable seats, they had to hold on to everything firmly or place children/shopping on their laps to prevent injuries caused by bad driving. They reported reaching offices with clothes/shoes crumpled and occasionally damaged. Although working women shared during the FGD that they needed to arrive at work looking presentable, but this was also about peer pressure. If they used public transport, their clothes and appearance were spoilt, and they would be ridiculed and censured by their colleagues for not being able to afford a better way of commuting.

Summarising the overall picture, regardless of gender, traffic delays through poor planning, inadequate service provision and traffic infringements create commutes that are stressful, uncomfortable, unsafe, long and unpredictable (in terms of time and route). This means that employees may be worn out or ill-prepared to start their work. Repeating the same journey after work may severely impact on leisure time – or for women, their ability to perform household duties. It is essential to recognise the gender-related effects of transport on women’s employment. In the most general terms, women are more affected by inadequate and unsafe transport than men. For example, their most trips required modal shifts which were more resource-intensive, in terms of cognitive and affective overloads (planning and anxiety), cost and time of family members. This means that a highly educated woman who has gained permission to work from her family will be disadvantaged by restrictions in her mode of transport, choice of employment, cost and length of travel and personal safety. These are explained in further detail by looking more detail at the gender-related issues raised in the focus groups, in each sector.

3.2Sector-based division of issues and their impacts

Sector-based issues are discussed here to synthesise the effects of poor design, task-based factors, personal sector issues and organisational sector issues:

3.2.1Contextual sector-design issues

The problem of poor bus design was raised by all of the women in the FGD as opposed to 50% of men. They were wary of several issues including the lack of designated seating for handicapped or elderly people, lack of storage space, the height of entry steps and absence of hold rails which pose additional problems for women wearing a traditional dress, carrying shopping or young children:

‘I already had an accident once while entering a bus since the entrance step was feeble, and I stepped on it in a hurry. As a result, it broke, causing me leg injury’ (A3).

Design failures were exacerbated by the age and poor maintenance of the vehicles and overcrowding. Space and seating were segregated by genders, with a smaller compartment allocated to women, reflecting their lower place in society. when the decisions around seating were further debated, gender-based differences were visible. 50% of men considered it acceptable to sit or stand in the women’s compartments if there were spare seats. In contrast, 2/3rd of women would not occupy seats in the male section even if they had to stand for long durations as they would feel unsafe: faced a lack of sufficient seat situation.

‘I do not even feel comfortable in our compartment and feel that something bad is going to happen. So, I will avoid sitting in their section at all costs as then they will be even closer, and I can easily be harmed’ (B2).

Men would occupy the women’s compartment as well as sit on the bus roof. Women would not do either-even if there was space. Crowding not only compromised women’s comfort but also their safety. It brought them into proximity to men and enabled men to harass women while remaining anonymous. However, the partition was done in a way that did not benefit women while women also identified specific features of the seat design which made them more conscious and vulnerable to harassment, as ‘there is a gap between the seat and its back. Men try to touch women through that gap and keep murmuring filthy stuff’ (A3).

50% of women and 17% of men from the FGD also raised concerns about undesignated or rudimentary stops at most locations. Some of the female participants from FGD also highlighted that the lack of bus stops gave bus drivers the freedom to stop in the middle of the road, risking the lives of passengers. Women expressed more concerns regarding the quality and provision of public transport. Women walking along the side of roads were mostly subjected to high levels of traffic and environmental pollution (with garbage dumped or burnt on the side of roads). This together with high temperatures and humidity had a greater effect on women. It is noteworthy that the problem of rudimentary bus stops and poorly managed public spaces was highlighted only by females. As a result, they had to accept the poor design and service of buses and rickshaws while a few of these were unwilling dependency on vans or other hired transport service limits their mobility to scheduled hours which cannot be useful for unpredicted travel, e.g. if they have to work over-time or require building their social capital. Private vans also take longer, with journey times doubled or tripled for those who are picked up first. This not only meant spending more money but also more time.

3.2.2Contextual sector-task related issues

Looking at the end-to-end journey, from leaving the house to arrive at the place of work, at each stage women faced more barriers to their travel, which together added to commuting stress. Due to the lack of key information, they faced difficulties in getting to the bus stop, knowing the timetable, getting safely to their destination and paying the fare. Further, the uncertainty attached to transport, such as the lack of regular service made women feel unsafe since long waits on the roadside for buses left them vulnerable to harassment and wasted their time.

For regular journeys, the unreliability of transport (e.g., lack of frequency of buses, ad hoc route changes and pricing), changes of personal circumstances (such as the need to work late) and the need to reduce the potential for harassment, makes the provision of travel information important. The effects of poor information were more severe for women leading to increased travel expenditure, lesser free time and riskier trips. The lack of regulated and visible tariffs and meters, as well as the lack of reliability of buses, requires extra cash to be carried, which increases the chance of a lot of money being lost if there is theft. Fare negotiation was challenging for both genders, but less so for men, for two reasons; firstly, women are more easily intimidated and are powerless in the public realm and for this reason, young women were particularly overcharged. Secondly, women sometimes have no viable alternative but to use rickshaws, allowing the drivers to manipulate this group by charging them more. As a result, their lack of transport alternatives was exploited by the driver’s fare inflation.

Talking about introducing improvements in the existing public transport, the respondents were asked about their opinions of having buses that are equipped with an electronic payment system with fixed fares, and if it would make them prefer using buses more than other modes after this change. Most of the males i.e. 66.67% were sceptical about the electronic payment system and shared that it will not create any significant impact and might even not be a contextually feasible option. For females, it will be preferable as it will help regulate the payment system and they seemed to be more positive about such an improvement as compared to men. A5 mentioned,

‘Yes, the payment system needs to be improved for buses as well as for rickshaws as it leads to a lot of confusion. Usually, the conductor forgets that I have already paid my fare and keep asking for it. In such a situation I get quite annoyed’ (A5).

Replacing the manual fare collection in public buses with fare payment technology was also suggested by the respondents. Transport does not support the safe door-to-door journey as shown by the lack of integration and smooth connectivity between the various modes. While men could shift to motorbikes, women faced various challenges and barriers which inhibit their career progression. Women could not drive motorbikes, as they are culturally discouraged from doing so. Their responses displayed that they had limited travel options available and mostly had to depend on their family members for their unplanned travel. Their dependency on male counterparts allows retaining the cycle of disadvantages and silencing of women, thus making them second-class citizens. They also had to consider the duration of their trips. Due to the lack of modal integration, their mobility choices varied during the day depending on the design, predictability and reliability of transport service, while for men, journeys remained less complicated and involved much lesser planning. Their unscheduled trips (such as having to stay till late at work) required modal shifts which were more resource-intensive, in terms of cognitive and affective overloads (planning and anxiety), cost and time of family members.

Most women have a limited geographical scope, which poses barriers to their career advancement. Where they are permitted to work, they were compelled to seek local employment and perhaps settle for lower-paid jobs despite their high qualifications. One of them shared that she has been looking for jobs for about a year, and managed to convince her family to allow her to work by ensuring proximity to the home:

‘I was not permitted to work although I was being offered a better job in Clifton. They (parents) said that it’s very hard and expensive for a girl to work far from home and cannot allow me to travel so far on my own every day’ (A2).

Many men used motorbikes to allow them access to parts of the city that are difficult or impossible to reach by public transport. Participants from the FGD cited many instances of having missed opportunities to work or socialise due to the lack of route coverage or the cost of alternative forms of transport. Women are not only paid 34% less than men for similar work because of the gender wage gap [51] but if their expenditure on transport is too high, their mobility will be severely questioned. This is because their need to travel is weighed against the preferred division of household labour. Thus, poor transport route coverage and lack of reliable and affordable transport become additional reasons (apart from gendered household duties) for not allowing educated and able women to seek employment outside thehome.

Extended journey time due to the lack of information had a more significant effect on women’s engagement with paid and unpaid work. Women reported longer waiting times which significantly reduced the time they have at their disposal. As a result, most women had limited accessibility to jobs as well as leisure time. As a result, women had to take employment which is in close proximity to their homes. Otherwise, they had to make multiple stops for a range of different reasons or depend on hired transport service to avoid walking to and waiting at bus stops where they face frequent harassment.

3.2.3Personal sector issues- individual and socio-cultural factors

For women who participated in the discussion, household duties have to take precedence over other tasks. This means that they need to carefully balance and schedule their household chores, paid employment and commuting time to make sure all can be accommodated in a day. As can be seen from Tables 1 and 2, commuting times are long, and can be longer for women as they do not have private means of transport. Their work-life balance is further skewed because of their household responsibilities which have to be undertaken before and/or after work. Men do not share this burden. This added burden may double the hours a day a woman spends working and reducing the among of leisure and rest time available to them. Quality of life may be further compromised for women by the reluctance of families to grant permission for them to make leisure, social or health-related journeys. there was a strong consensus among male participants in the FGD that non-work-related journeys were only questioned for women. In reality, it was unlikely that families would let a woman go out with friends for recreational purposes. In contrast, men did not report the need to ask for permission for any trips.

Commuting times for everyone could be reduced if there was a better public transport serviced (more routes, more vehicles), enforcement of traffic legislation and better transport management to reduce congestions and accidents. and gender harassment. For example, women avoided walking across lanes of traffic (jaywalking) or using pedestrian bridges due to harassment and fears for their safety. Commuting times for women could be reduced and made cheaper if they were allowed to use private firms of transport, most notably, motorbikes. Female motorbike ridership is relatively rare in Pakistan and is socially/culturally unacceptable – although women can ride side saddle as passengers. The female participants were enthusiastic about this opportunity and appreciated the efforts of women who had started riding motorbikes and were breaking gender stereotypes too:

‘I think it will be very encouraging to see females riding motorbikes as they can be independent easily. Males still consider females their pair ki jooti (translate: shoe) and this is visible in public transport too. Such an attitude needs to be changed, and females need to start taking drastic steps now’ (A3).

On the other hand, half the males had reservations and were more guarded in their comments.

‘Riding a bike means a lot of outside exposure, I think females who ride motorbikes invite trouble for themselves’ (B2).

It was clear that the men wanted to adhere to the gender stereotypes prevalent in society, which promotes the dependence of women on their male counterparts and prevents them from being independent under the guise of safety. showed little concern over the fact that social taboos ‘forbid’ women to sit astride on motorbikes with only a third of the male FGD participants supporting women’s solo ridership and independent travel. Most of them did not consider it a breach of women’s rights or unfair that they could not enjoy the same freedom as men.

At a personal level, women reported that their families did not encourage mingling with male colleagues or coming home during late hours (i.e. after 7 pm). As transport is less frequent and more dangerous at night, if a female employee was required to work late, she would have to gain the permission of her family and make arrangements to travel home in safety (e.g. using a Qingqi or uber), and arrange for a male chaperone from the family. This inability to work flexibly may decrease chances of career progression and job satisfaction and increase tensions within the family.

At a societal level, women’s career advancement was linked with moral corruption and it was considered exploitation of their morality:

‘We often hear comments like respectable girls don’t get jobs or don’t get promoted.’

Apart from severe design and task-related issues, women shared issues related to their poor agency in choosing the mode of transport, time of the trip and its purpose. Networking chances are minimised due to the lack of transport accessibility and social stigma around non-work trips being considered purposeless. Furthermore, women were afraid of being judged by work colleagues for using public transport increasing their dependence on expensive modes of transport. that overcrowded buses make passengers’ clothes/shoes crumpled and occasionally damaged. In all studies, working women reported that they needed to arrive at work looking presentable, but this was also about peer-pressure. If they used public transport, their clothes and appearance were spoilt, and they would be ridiculed and censured by their colleagues for not being able to afford a better way of commuting. Men were either not subject to the same social stigma or did not feel its effects. Women shared that they wanted to appear professional and one admitted that she would lie about her use of public transport to her colleagues so she would not be judged. Early career women cared more about their reputation and did not want to be judged for not looking appropriate. One of them shared that she might stop using public buses because of the effects of crowding on buses had on her appearance,

‘I look really different when I reach work as all my preparations go to waste due to the crowding on the buses. So, I think eventually I will have to stop using public transport so that I can reach my workplace on time without looking like a mess’ (A1).

3.2.4Organisational sector issues

Participants shared that there were no direct buses to key centres of production, business or education. Buses were less frequent after 7 pm and almost non-existent after 9 pm [52]. It was evident that although more men reported having suffered at the hands of poor coverage, women faced more difficulties in dealing with the lack of route coverage since they had little or no options otherwise:

‘I would prefer using my motorbike as I know all the shortcuts and can easily get home even if it is late’ (B5).

A female participant commented, ‘I will call a family member to pick me up as travelling alone during dark is not appreciated by my family’ (A2).

While respondents from both genders commented on the lack of routes, for women, the situation was more complex. For example, women travelling at night not only struggled with poor route coverage but felt unsafe and stigmatised since those travelling after 7 pm are considered to be of ill-repute. Their vulnerability to harassment further deprives them of their agency and increases their dependence on male family members, especially at night.

The lack of route coverage was further exacerbated by poor traffic management and lack of accountability, A2 highlighted the lack of infrastructure which allows the drivers to get away with breaking laws: ‘There are no bus stops, people can stand anywhere, and even bus drivers stop in the middle of the road’ (A2).

High levels of crowding in buses, were tolerated as a necessity – as buses were so infrequent. Installing cameras inside the buses, may not be realistic given the cost and overall decrepitude of the fleet but it was seen as a positive step as narrated by respondent A4:

‘Cameras can bring a lot of improvement, but only if they stay functional, I will prefer to travel on buses. Buses will not only become safer but also cleaner as whoever spits in the bus or throw trash, can then be fined’ (A4).

Additionally, it was reported that the bus drivers tended to ignore female passengers when waiting for a bus because they required more time to get on and off the bus (e.g. due to the design of the steps and females’ clothing). For a female respondent, this was a hurdle apart from the crowd in the buses.

‘The drivers do not stop the bus and have to jump off when it’s still moving. They behave without considering women and use very abusive language’ (A1).

Although currently there is zero representation of women in transport operations, women from FGD were not only more hopeful than their male counterparts about the positive impact of female representation but they shared that having a female conductor would make them feel more comfortable to travel even after dusk. They considered it critical in not only fostering personal safety but also encouraging passengers to be more disciplined. For them, it can lead to mainstreaming their gender-based concerns in transport policy and operation.

Men found it difficult to accept such a change:

‘I can only expect more problems such as the lady being harassed. Even lady constables get harassed, so this lady conductor will also be vulnerable’ (B3).

Thus, this showed a deeply embedded cultural perception that discouraged women to have challenging roles assuming that such independent women are from badly reputed families. Apart from the perceptions regarding female employment, there is a poor provision of child-care services at most workplaces [52]. Many of the female participants agreed that when they are working, they are worried about their children’s diet in their absence.

Street crime is also widely prevalent in that it makes it difficult to walk even for short distances. A3 shared, ‘I have been robbed many times while walking, so I would take a Qingqi or rickshaw.’

A few of the male participants also shared the helplessness in such a situation,

‘I take a bus every day and make sure to keep all the belongings in a zipped pocket inside my bag, that is all I can do, but I have still been robbed twice’ (B1).

The impact of crime made it difficult for them to undertake trips at night specially since there was no reporting mechanism. One of the situations discussed was about dealing with a deadline at work, requiring respondents to work in the evening. In this case, half the women would call on family members for lifts because of reduced public transport services at night and safety issues. None of the men mentioned that they would call family members to pick them up if they had to work late. This may indicate that they felt more empowered, had alternative forms of transport, or did not experience problems, as one male participant shared, ‘I would prefer using my own motorbike as I know all the shortcuts and can easily get home even if it is late’ (B6). A3 reported that after she had been robbed on a bus, she went to the police station with her father to make a complaint, but they did not even consider it worth reporting since there are so many mobile phone snatching crimes each day. The introduction of a Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) for surveillance inside buses was perceived positively by 100% of women and 50% of men during the FGD. Most felt it would be an encouraging step and might increase bus ridership.

Street crime not only leads to riskier trips but could also entail gender-based violence. Nearly 80% of women as opposed to 35% of men felt unsafe on buses and are afraid to be raped. There was a sense of acceptance among respondents about the need to be cautious for women about their safety while travelling on public transport. Women have also accepted that they have to curtail some opportunities for reasons beyond the lack of transport, such as the risks induced by their gendered identities, and this makes them seek permission or remain indoor. From the FGD, half the women would not react to any form of harassment, and they found it difficult to protest against such behaviour because of social conditioning and the fear of escalating the incident. Thus, a female participant shared that the reason behind staying silent,

‘I will stay silent as the harassment blame always comes on the women as if she initiated it. They are considered open and of loose character, inviting harassment’ (A4).

This made them more vulnerable to accepting harassment, and many cases are not reported. Such responses also indicated that it was considered more important that women stay mentally vigilant all the time. In such cases, the need to expose the perpetrators or to teach them a lesson would not arise. What is more, gender norms impacted the way that women can make decisions about their mobility, which translates into their use of transport. Their decisions about participation are bound with the need to feel safe during their trips. Therefore, they prefer privately hired and door-to-door service. The understanding of these safety perceptions helped to see how women viewed themselves and how they are viewed in society.

4Discussion

Access to reliable, safe, comfortable and affordable transport is essential for entry into employment. In Karachi and other cities in the global south, transport poverty affects both genders and curtails life chances. The disproportionate effects of poor transport on women are well known [42]. Apart from poor accessibility, socio-cultural factors significantly restrict early-career women’s mobility, limiting access to jobs, lengthening journeys, and exposing them to harassment. Transport is a male-dominated industry, run by men with traditional values who do not believe women should be in the public space or work outside of the home. Transport problems caused by poor organisation and investment are made worse for women as what transport there is, is subject to gender inequalities such as poor and unequal partitioning of bus interiors, freedom to harass and overcharge women, restrictions on the use of alternative forms of transport.

As such, women were facing more issues than men. The key reason for this difference was that the personal sector issues were seen to exaggerate the effects of issues from other sectors for women. These interlinks can be understood in Table 3. The lack of independent decision-making regarding the mode, purpose, duration and nature of their trips was evident in all the sectors. For example, lack of adequate ventilation in buses, when temperatures are in the mid-30s or 40s was further exacerbated for women by cultural issues which required them to cover themselves completely. Additionally, women are required to act modestly and not draw attention to themselves, e.g. through fanning movements.

Table 3

Cross-overs between the various sectors

| Levels | Contextual sector (design and task) | Effects on employment |

| Workstation level factors | Poor in vehicle ergonomics | Inability to look professional at work, |

| Poor noise control and ventilation | poor body posture due to seat design, harassment, poor passenger safety | |

| Exaggerated for women due to | No consideration for hot and humid weather making women suffer due to the strict dress code | |

| Workplace level factors | Lack of seating and storage space and lack of cleanliness | Longer waiting/standing time, having to carry shopping and children, tiresome trips |

| Exaggerated for women due to | Social stigma, division of labour | |

| Work setting level factors | Rudimentary bus stops, unwarranted changes to routes or failing to stop when requested | Poor safety, poor punctuality, women more vulnerable if there are changes in routes |

| Lack of trip information and lack of integration | Need to get permission for non-work trips | |

| Exaggerated for women due to | Less time for leisure since household duties have to be prioritised and their vulnerability to sexual harassment | |

| External factors | Overcharging/changing fare costs | Women pay more and still have uncertainty, being questioned about the cost |

| Exaggerated for women due to | Cultural restrictions on modal choices | |

| Levels | Organisation sector | Effects on employment |

| Workstation level factors | Poor behaviour of passengers | Poor hygiene, fear of harassment |

| Exaggerated for women due to | The attitudes of men | |

| Workplace level factors | Poor behaviour of transport staff | Poor accountability of drivers who can cause health and safety risks |

| Exaggerated for women due to | Bus staff not allowing women enough time to egress or ingress despite the clothing of women | |

| Work setting level factors | Lack of route coverage and lack of traffic management | Increase travel time/ poor predictability |

| Exaggerated for women due to | Perception regarding late-hour and non-work trips, cultural restrictions on modal choices | Women not being supported by their families when they get harassed |

| External factors | Lack of female representation | Tiring and multi-modal trips |

| Poor road infrastructure | Time delays | |

| Informal transport service | ||

| Exaggerated for women due to | Lack of agency, crime and lack of gender equality | Unsafe travel conditions avoiding deserted spaces |

Due to the lack of acceptance for their mobility, women selected more expensive modes of transport to save time, keep safe, maintain their reputation and reduce the burden they place on their families (who will be worried for their safety and might have to pick them up after sunset – both of which may remove liberties of females). The attitudes faced by them at the household level also affected their career choices and advancement. Although employment offers relatively more agency to women than being financially dependent on male family members, women still have to abide by strict spatial and temporal restrictions, which hinder their growth. They had to seek permission to work; this may be conditional on the location of the place of work and assurances that household responsibilities will not be compromised. They had to prioritise their household work and have had to undertake complicated journeys, because of the nature of their responsibilities. Not only did women’s dependency on men to facilitate their travel result in accepting their authority, but they related their poor agency and representation in transport to their lack of voice and position at homes. This was also reflected in the indecent behaviour of drivers and conductors towards women.

Many times, womanhood constituted a risk due to the disrespect shown by people to working women and resulted in women having to curtail their mobility due to the potential annoyances and dangers incurred during travel. The meanings constructed by women and men regarding the everyday episodes of harassment displayed narrow-minded attitudes of men regarding harassment who blamed women for walking on roads, taking public buses and waiting at bus stops, since they invite trouble for themselves through these actions. A few of them even tried to normalise harassment and disguise it as a form of flattery, but for women, these are not harmless acts of casual gestures, but ways of displaying power over the weakest in the absence of the rule of law. The overpowering attitudes of male drivers were considered as yet another example of male dominance, while the subordinate position of women in public and private spaces was likened to a shoe (A3), which has the lowest value and can be treated poorly.

Not only do women have limited opportunities at their end due to the socially accepted gendered professions, but men did not experience problems with managing to stay till late at work and were not so dependent on family or needed to shift to alternative modes. This may indicate that they feel more empowered or less unsafe. Most women had the added concern that crime would lead to sex-based violence. If they appeared lost and confused when trying to find a bus stop or route, they feared they would be kidnapped or raped. They avoided overhead walkways since these are frequented by men, who search out poorly lit or deserted spaces to prey on women

Overall, gender has a profound impact on women’s decision-making regarding their modal choices, time allocation and journey purposes. Men have the liberty to choose a mode of transport and had the right to mobility, while women were restrained from independent decision-making. In sum, gender roles and expectations from women to keep themselves safe not only hampered their right to work but also caused their loss of agency. Focusing on the personal sector issues faced by a female traveller added more depth to the range of issues (such as lack of modal choice, cultured division of labour and vulnerability to harassment) that could have an impact on a user’s travel decision-making at various stages of travel. This work, therefore, makes a significant contribution to further use of the H-S model to understand the relationship between these factors, mobility and the transport system.

5Conclusion and recommendations

The H-S model is useful for analysing and discussing the results because women were not only affected by operational factors but socio-cultural barriers such as exclusionary cultural norms regarding taking permission. It thus helped to integrate the gender-based socio-cultural factors in the theoretical model, which were more influential in depriving women of opportunities to grow. The inability of women to move around freely due to the social context was exaggerating the effects of all other sectors. They cannot move around as freely as their male counterparts which substantially reduce their access to social capital. The FGD helped to see the gender-based comparison, and women were seen to suffer not only due to poor transport but also the perceptions and attitudes of people regarding their mobility and employment.

Although they were employed, they had to limit their commute to fixed hours and were not encouraged for non-work trips that could increase their employability. As such, their career progression was stigmatised and they were required to limit their opportunities so that these do not conflict with their gender roles at home. The complexity of issues faced by women requires devising policy initiatives that can affect both the operation of transport as well as create more acceptance for women at the social level.

As argued in this paper, not integrating the gender-based disadvantages faced by women into planning, reinforces their disadvantaged position and force them to take complex trips. There is thus a need to go beyond the conventional measures of understanding social exclusion related to transport and investigate the barriers that exert power on women’ independence for retaining the traditional gender roles. In the context of this research, the model can help illustrate where changes can be made in the system considering the social aspects of transport. An initial set of recommendations are proposed based on the findings in Table 4. The focus is mainly on areas that require tractable improvements, for example, the need to regulate the behaviour of transport operators as well as users.

Table 4

KPIs for different journey phases

| User group | Proposed suggestions | Journey phase |

| All travellers | Priority seating for pregnant women | On trip |

| All travellers | Quality of timetable information/ Real-time information about the service | Pre-trip |

| All travellers | Appropriate seating (design, space allocation, well-maintained vehicles etc.) | On-trip |

| All travellers | Comfort on board (ventilation, noise blockage etc). | On-trip |

| All travellers | Accessible travel timing information | Pre-trip |

| All travellers | Adequate luggage space for storing bags | On-trip |

| All travellers | Integrated or seamless service with standardised fares | Pre-trip and on-trip |

| All travellers | User-friendly staff behaviour | On-trip |

| All travellers | Periodic and regular transport service and more bus routes especially during late hours | On-trip |

| All travellers | Easier ticketing system for fares with adequate information | Pre-trip |

| Women | Safety from harassment (CCTV surveillance, female bus conductors, enforcement of reserved seats for female) | Pre-trip, on-trip and post-trip |

| All travellers | Installation of road signage. traffic lights and pedestrian crossings | On-trip |

| All travellers | Provision of cleaner travel conditions (e.g. placing dustbins inside the buses) | On-trip |

| All travellers | Well-lit and sheltered bus stops for ensuring safety and reporting mechanism for crime | On-trip |

Conflict of interest

None to report.

References

[1] | Khan F . Barriers to pay equality in Pakistan: The gender pay gap in the garment sector. (2017) :International Labour Organization. |

[2] | Batool SA , Batool SS , Ahmed HK . Socio-Demographic Determinants of Economic Empowerment of Women. Pakistan Journal of Women’s Studies: Alam-e-Niswan. (2017) ;24: (1):55–69. |

[3] | Drucza K , Peveri V . Literature on gendered agriculture in Pakistan: Neglect of women’s contributions. Women’s Studies International Forum. (2018) ;69: , 180–9. |

[4] | Asian Development Bank. Pakistan Country Gender Assessment Volume 1 of 2: Overall Gender Analysis, Mandaluyong. 2016. Available from: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/21/pak-gender-assessment-vol1.pdf. |

[5] | Heraa N . Transportation system of Karachi, Pakistan. Unpublished Research Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Asia Pacific Studies. Japan: Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University 2013. |

[6] | Ghani JA. The Emerging Middle Class in Pakistan: How it Consumes, Earns, and Saves. International Conference on Marketing. [online] IBA: Karachi; 2014. available from: http://iba.edu.pk/testibaicm/parallel_sessions/ConsumerBehaviorCulture/TheEmergingMiddleClassPakistan.pdf [18 Oct 2017]. |

[7] | Hussain I . Problems of Working Women in Karachi, Pakistan. Newcastle upon Tyne.: Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2008. |

[8] | Sadaquat M , Sheikh Q . Employment situation of women in Pakistan. International Journal of Social Economics. (2011) ;38: (2):98–113. |

[9] | Azcona G, Staab S. Opinion: Available from: How to make progress on the SDGs? Prioritize gender equality [online] Devex; 2018. https://www.devex.com/news/opinion-how-to-make-progress-on-the-sdgs-prioritize-gender-equality-8[9 May 2019]. |

[10] | Rehman S , Azam Roomi M . Gender and work-life balance: a phenomenological study of women entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. (2012) ;19: (2):209–28. |

[11] | Tarar M , Pulla V . Patriarchy, Gender Violence and Poverty amongst Pakistani Women: A Social Work Inquiry. International Journal of Social Work and Human Services Practice. (2014) ;2: (2):56–63. |

[12] | Iqbal MJ . ILO Conventions and Gender Dimensions of Labour Laws in Pakistan. South Asian Studies. A Research Journal of South Asian Studies. (2015) ;30: (1):257–71. |

[13] | Adeel M , Yeh A , Zhang F . Gender inequality in mobility and mode choice in Pakistan. Transportation. (2016) ;44: (6):1519–34. |

[14] | Khan A . Women and Paid Work in Pakistan: Pathways of Women’s Empowerment. Collective for Social Science Research. (2007) ;1–32. |

[15] | Haque R . The Institution of Purdah: A Feminist Perspective. Pakistan Journal of Gender Studies. (2008) ;1: (1):47–71. |

[16] | Shah B. ‘Pakistan: Purdah.’. Secularism is a Women’s Issue [online]. 2017: http://siawi.org/spiphp?article14070[18 Dec 2019]. |

[17] | JICA. The study for Karachi transportation improvement project in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. [online] 2012 Available from: http://open_jicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12086369_01.pdf [14 January 2018]. |

[18] | Uteng TP , Turner J . Addressing the. Linkages between Gender and Transport in Low- and. Middle-Income Countries. Sustainability. (2019) ;11: (17):4555. |

[19] | Ahmed QI , Lu H , Ye S . Urban Transportation and Equity: A Case Study of Beijing and Karachi. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. (2008) ;42: (1):125–39. |

[20] | Hasan A , Raza M . Responding to the transport crisis in Karachi. IIED Working Paper. London: IIED. |

[21] | Kenyon S , Lyons G , Rafferty J . Transport and social exclusion: investigating the possibility of promoting inclusion through virtual mobility. Journal of Transport Geography. (2002) ;10: , 207–19. |

[22] | Lucas K . Transport and social exclusion: where are we now? Transport Policy. (2012) ;20: :105–13. |

[23] | Levy C . Travel choice reframed: “deep distribution” and gender in urban transport. Environment and Urbanization. (2013) ;25: (1):47–63. |

[24] | Litman T . The future isn’t what it used to be: changing trends and their Implications for transport planning. Victoria Transport Policy Institute. (2012) Available from:http://www.vtpi.org/future.pdf. |

[25] | Wilson A . A guide to Phenomenological Research. Nursing Standard. (2015) ;29: :38–43. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.34.38.e882. |

[26] | Scotland J . Exploring the Philosophical Underpinnings of Research: Relating Ontology and Epistemology to the Methodology and Methods of the Scientific. Interpretive, and Critical Research Paradigms. English Language Teaching. (2012) ;5: (9). |

[27] | Craig PA . Evaluating pilots using a scenario-based methodology. International Journal of Applied Aviation Studies. (2009) ;9: (2):155–70. |

[28] | Roufa T . Scenario- and Experience-Based Interview Questions. Balance Careers. 12th August. Available from: https://www.thebalancecareers.com/prepare-for-scenario-interview-questions-974768 [14 April 2020]. |

[29] | Robson C , McCartan K . Real World Research, 4th Edition. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. |

[30] | Krueger RA , Casey MA . Participants in a Focus Group. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. (2009) (4th ed). |

[31] | Tang K , Davis A . Critical factors in the determination of focus group size. Family Practice. (1995) ;12: (4):474–5. |

[32] | Hamza A. ‘7,500 new motorcycles hit roads daily in Pakistan’. Daily Times [online] 2018:13 Jan. Available from: https://dailytimes.com.pk/179824/7500-new-motorcycles-hit-roads-daily-pakistan/. |

[33] | Hoodbhoy P . Women on motorbikes-What the problem? The Express Tribune, [Online] 2013, 23 February. Available from: https://tribune.com.pk/story/511107/women-on-motorbikes-whats-the-problem/ [07 Jan 2018]. |

[34] | Cresswell T . Towards a Politics of Mobility. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. (2010) ;28: (1):17–31. |

[35] | Woodcock A . New insights, new challenges; person-centred transport design. Work. (2012) ;41: :4879–86. |

[36] | Kang M , Lessard D , Heston L , Nordmarken S . Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies. Sexuality Studies. Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies Educational Materials. (2017) ;1: , 1–101. |

[37] | Woodcock A . The Contribution of Ergonomics to The Design of More Inclusive Transport Services. 7th International Conference ‘Towards a humane city’ conference, Urban Transport 2030- Mastering Change. Held 5-6 November 2015 at University of Novi Sad, Serbia. 87–92. http://humanecityns.org/. |

[38] | Woodcock A . The whole journey experience through the lens of the Hexagon-Spindle model. In Designing Mobility and Transport Services. Developing traveller experience tools. Ed. By Tovey,M Woodcock,A, and Osmond,J. Oxon: Routledge. (2017) ;57–65. |

[39] | Woodcock A , Woolner A , Benedyk R . Applying the Hexagon-Spindle Model for Educational Ergonomics to the design of school environments for children with autistic spectrum disorders. Work. (2008) ;32: (3):249–60. |

[40] | Iqbal S . Mobility Justice, Phenomenology and Gender. Essays in Philosophy. (2019) ;20: (2):171–88. |

[41] | Haider M , Badami M . Public Transit for the Urban Poor in Pakistan: Balancing Efficiency and Equity. Regional Focus: Asia. 2004. |

[42] | Raza M . Exploring Karachi’s transport system problems: a diversity of stakeholder perspectives. (2016) . Working paper. IIED: London. |

[43] | Paracha NF . Prohibition and Sharab as political protest in Karachi. In Cityscapes of Violence in Karachi. Publics and Counterpublics, ed. by Khan,N. London and New York; (2017) Hurst and Co. |

[44] | Chêne M. Overview of corruption in Pakistan. Transparency International [online] 8 Aug. 2008 Available from: https://www.u4.no/publications/overview-of-corruption-in-pakistan.pdf. |

[45] | World Bank. Pakistan Infrastructure Implementation Capacity Assessment (PIICA). South Asia Sustainable Development Unit. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/129721468143696921/pdf/416300PK.pdf. |

[46] | Hasan A . Land ownership, control and contestation in Karachi and implications for low-income housing. Urbanization and Emerging Population Issues. (2013) ;(10). http://pubs.iied.org/search.php?s=UEP. |

[47] | Shehri-CBE/ Citizens for a Better Environment Strategic issues in urban transport: realities, policies and implementation issues in selected urban cities of Sindh. (2018) Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftungfür die Freiheit: Karachi . |

[48] | Klair A . A Roads in Pakistan remain dangerous for pedestrians. The Express Tribune [online] 7 April. (2017). Available from: https://tribune.com.pk/story/1377154/roads-pakistan-remain-dangerous-pedestrians/ [30 Jan 2018]. |

[49] | Hussain A . Urban Sprawl, Infrastructure Deficiency and Economic Inequalities in Karachi. Sci Int (Lahore). (2016) ;28: (2):1689–96. |

[50] | Ilyas F . Environmental concerns raised over $220m Red Line BRT project. DAWN [online]. Oct 17th. (2018) Available from. https://www.dawn.com/news/1439461. |

[51] | Ali L , Akhtar N . Gender earnings gap in urban Pakistan: evidence from ordinary least squares and quantile regressions. Pressacademia. (2016) ;5: (3):274–274. |

[52] | Roomi MA , Parrott G . Barriers to Development and Progression of Women Entrepreneurs in Pakistan. The Journal of Entrepreneurshi. (2008) ;17: (1):59–72. |