Menopause and work: A narrative literature review about menopause, work and health

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Menopause is part of working women’s lives. In Western countries, labour market patterns are changing rapidly: women’s labour participation has increased, the percentage of full-time working women is rising, and retirement age is increasing.

OBJECTIVE:

This narrative literature study aims to provide an insight in the state of the art in the literature about the relationship between menopause, work and health and to identify knowledge gaps as input for further research.

METHODS:

The search was conducted in PubMed, CINAHL, MEDLINE and ScienceDirect. The final set includes 36 academic articles, 27 additional articles related to the topic and 6 additional sources.

RESULTS:

Research on menopause, work and health is scarce. Results are grouped thematically as follows: Menopause and (1) a lack of recognising; (2) sickness absence and costs; (3) work ability; (4) job characteristics; (5) psychosocial and cultural factors; (6) health; (7) mental health, and (8) coping and interventions. Work ability of women with severe menopausal complaints may be negatively affected.

CONCLUSIONS:

Due to taboo, menopause remains unrecognised and unaddressed within an organisational context. New theoretical and methodological approaches towards research on menopause, work and health are required in order to match the variety of the work contexts world-wide.

1Introduction

In Western countries, women make up half of the labour force in full- and part-time jobs [1–3]. Furthermore, labour market patterns are changing rapidly: women’s participation in the labour market has increased, the percentage of full-time working women is rising, and retirement age is increasing in many countries. As a result, a growing number of women aged 45 years and older participates in the labour market, hence, menopause is part of working women’s lives. Aim of this narrative literature study is to provide an insight in the state of the art in the literature about the relationship between menopause, work and health and to identify knowledge gaps as input for further research.

Virtually all women will go through menopause and, often, experience menopausal symptoms and complaints [4]. Given their high prevalence, symptoms can impact on women’s working lives. In a large representative Dutch study, older (> 45 yrs) and in particular highly educated female employees, reported high work-related fatigue [5]. The authors state that menopause may partly account for the unexplained differences in work-related fatigue between older highly educated men and women. To date, only few studies directly relate menopause to work, for instance to lower work ability [6–9], and show that both women and employers possess little knowledge about menopause. Employers are therefore unaware of how to contribute to a healthy working environment for female employees in this life phase, and women do not recognise their bodily signals or do not dare to ask for help [2].

1.1Menopause and menopausal complaints

In this review, we approach menopause as a physiological process and a female-specific transitional life phase in women’s natural ageing process [10]. Menopause, perimenopause and postmenopause are stages in a woman’s life when her monthly period stops. Perimenopause is the first stage in this process and can start eight to 10 years before menopause. Menopause is the point when a woman no longer has menstrual periods for at least 12 months. Postmenopause is the stage after menopause. Already in perimenopause women can have menopausal symptoms.

There is large variation of the age, as well as dur-ation and symptoms of menopause [11, 12]. Current definitions estimate the average duration of the menopause from five to 10 years, and the average age at which the menopause occurs, is 51 years [3, 13, 14]. Furthermore, no particular set of symptoms is unquestionably ‘menopausal’, except for biomedically defined physiological symptoms which are associated with fluctuating and declining hormone levels finally resulting in the end of the menstrual cycle. Often from the mid–40s onwards, the protective effect of estrogen is lost and changes occur that lead to an increased risk of heart disease in the ensuing years. Consequently, traditional cardiovascular riskfactors are becoming more important; for instance, more than half of the postmenopausal women will develop hypertension. Furthermore, increase in cholesterol, body weight and diabetes play an important role and can be positively influenced by healthy lifestyle [15, 16]. The most commonly reported symptoms related to the hormonal changes during perimenopause are hot flashes, night sweats and vaginal dryness [e.g. 17]. Non-specific complaints related to menopause such as sleeping problems, headache, fatigue, mood changes and loss of concentration are hard to distinguish from other health problems such as stress, hypertension and burnout [9, 14, 18, 19]. Hence, complaints may be related to menopause but not recognized as such, while vice versa, non-specific complaints may be attributed to menopause while having a different cause. Confusion among women themselves as well as their health professionals can be the result [20].

1.2Menopause as a life phase

Health complaints can occur during the menopausal transition which can last for 10 to 15 years, and changes can influence the quality of women’s lives [21–23]. Not only women themselves, but also society at large attaches meaning to menopause. Perceptions of menopause are embedded in gender ideologies, lack of understanding and stereotypes about ageing women [24]. Furthermore, different understandings of menopause are found across cultural groups. Menopause is more often viewed positively in cultures where ageing in general is valued [25]. Women’s interpretations of their symptoms depend on how ‘natural’ they are, or what their final period means to them [26, 27]. For some women, an end of physical fertility may be difficult, especially when fertility plays an important role in their identity as a woman. Ayers et al. conducted a systematic review to study the cultural, social and psychological context surrounding menopause, and reported that women who perceive menopause negatively, experience more complaints [24]. However, cause and effect remain unclear. Menopause and midlife can be problematic for women, but they can also be a turning point, after which women experience more focus and room for careers and self-development [26]. Dennerstein et al. showed that life events, daily activities, family life and job satisfaction all affect the mood of women during menopause [28]. Besides midlife is often characterised by age-related health problems and complaints, having adolescent children or becoming empty nesters, suffering from bereavement after the loss of parents, or providing informal care, a task still mostly assigned to women [2, 20, 29]. Disentangling menopause from other phenomena related to the life course, is challenging for women themselves, but also for occupational health physicians and other specialists and professionals, and for supervisors at work.

1.3Complex interconnections

Women’s bodily experiences and biological changes interact with the social and cultural context, such as work, in which women’s lives are embedded. This complicates the study of the biological phenomenon of menopause from a psychological or sociological perspective [9]. According to Dillaway, a holistic view of menopause is important for adequate treatment of menopausal complaints [11, 30]. She illustrates how women, doctors and researchers define and describe menopause mainly in terms of chronological age. However, age- and time-bound characterisations are insufficient. When health care professionals and women themselves do not recognize menopause as a life phase, for instance because they confine themselves to a certain age category to indicate menopause, negative consequences may occur: it may limit recognition and treatment options, influence complaints that women experience and undermine women’s confidence in their own bodies, which in turn can lead to a feeling of insecurity, to suboptimal treatment or delay in adequate treatment and influence quality of life. This leads us to the following research questions:

1. What is the state of the art in the literature about the relationship between menopause, work and health?

2. Which knowledge gaps can be identified?

2Methods

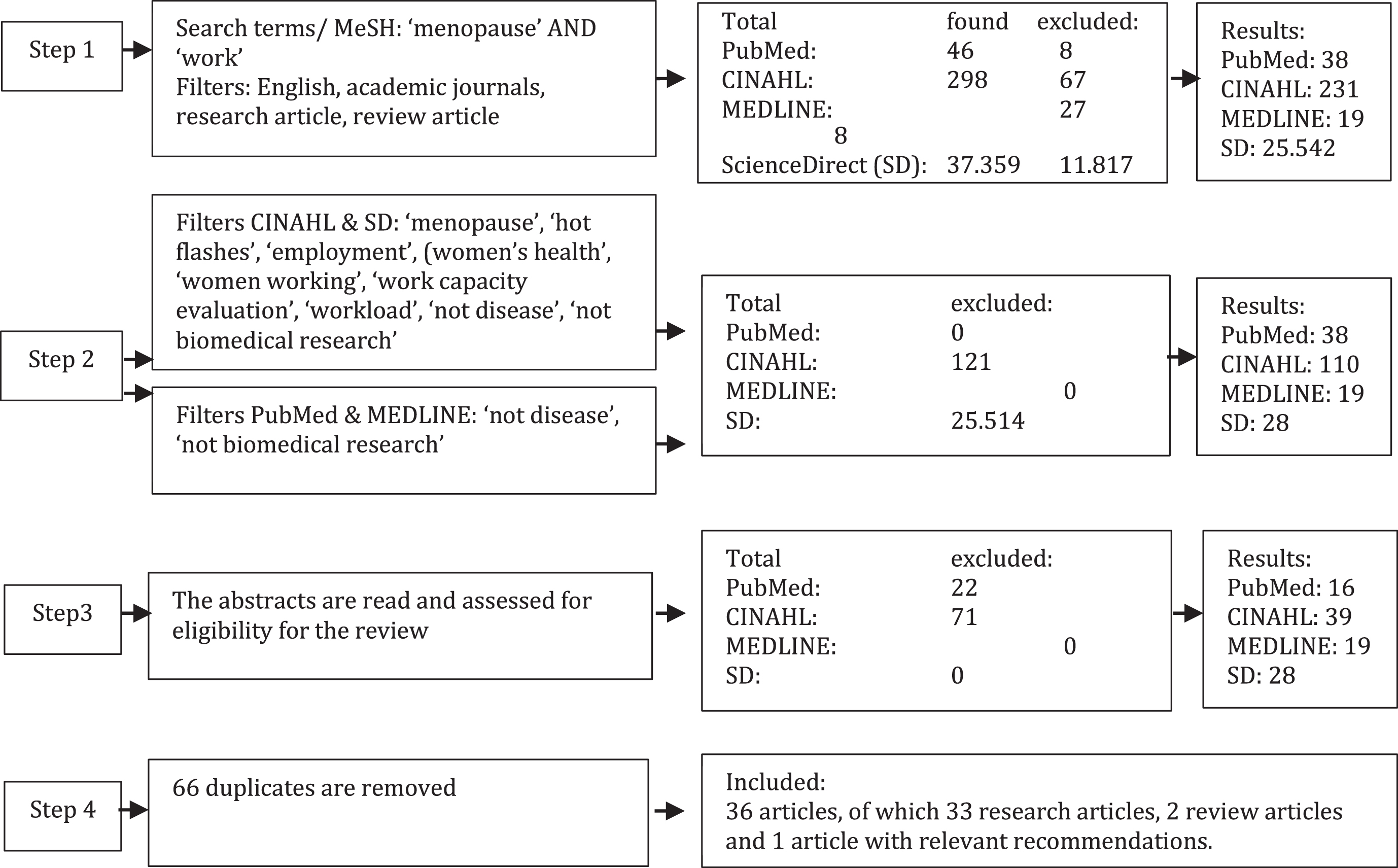

In this literature review, we conducted a narrative analysis and covered a broad range of topics by using studies of various complexity and design [31]. Our search was conducted between December 2018 and February 2019 in the databases PubMed, CINAHL, MEDLINE and ScienceDirect, originally using the MeSH terms ‘menopause AND work’. Our choice for the MeSH terms instead of the author’s key words was deliberate, because MeSH terms are assigned by the database specialists and function as stronger identifiers of the content. MEDLINE is a subset of PubMed, but given the low rate of the search hits found in PubMed we decided to include the searches in both databases as MEDLINE (1946) is older than PubMed (1996). This strategy resulted in many doubles, which were deleted during the fourth step of the search process. Inclusion criteria were the English language, empirical research and review articles to contextualise our findings. We screened articles and excluded those with an exclusionary medical content (see Fig. 1 Flowchart).

Fig. 1

Flowchart of empirical studies and reviews.

We excluded articles based on our selection criteria. We deleted doubles, after which two researchers checked abstracts of remaining articles. Finally, we analysed the subset of 36 articles (see Appendix). Selected articles have been read by at least two researchers. Notes have been compared and arranged thematically.

Besides these 36 selected articles, we used another 27 articles in our results section to contextualise and interpret our findings. Additional articles were found through snowballing, including in selected articles’ references, and were included when they helped to contextualise the findings. In these studies, the relationship between menopause and work was often secondary or marginal. A few sources were found via Google, e.g. union surveys.

3Results

3.1Not recognizing menopause

Both women and employers hardly receive information or training on menopause and thus, lack the knowledge about menopause-related health complaints and their impact on work [25, 32]. According to Fenton and Panay, this is out of balance when compared to the attention and support for pregnancy (leave) [33]. Female workers report a need to discuss menopause and break taboos surrounding menopause in the workplace. Often, women either do not see the opportunity or fear to discuss menopausal complaints and how they may affect their job performance [8, 25]. They fear speaking of menopause, in particular women in higher positions, for being ridiculed, stereotyped and stigmatised [2, 33]. Hammam et al. found that adverse (physical) working conditions (e.g. no ventilation, inflexible working hours, no possibility to change workload or tasks) were related to increased health complaints among postmenopausal women [34]. Discussing this with supervisors was uncommon, because of a lack of opportunity or time, or social and cultural barriers. According to Hardy et al., an open culture and a supervisor with basic knowledge about menopause facilitated the conversation about menopause and work, while supervisors’ gender (male), male dominance in the workplace, stigmatisation, fear, discrimination and shame were mentioned as barriers [35]. In the communication itself, being understanding, jointly looking for solutions and an empathic sense of humour were important, whereas not being taken seriously was felt as a barrier. Education and training programmes for women themselves are important and may help to diminish menopausal complaints [36].

3.2Menopause and sickness absence and costs

A few studies focused on the relationship between menopause, absenteeism and productivity loss and costs. Geukes et al. state that three quarters of symptomatic menopausal Dutch women looking for professional help because of health complaints, has an increased risk for sickness absence, and possibly even for early withdrawal from the labour market [1]. Other studies report that menopause is associated with lower work productivity and short-term sick leave, and hence, with increased (indirect) costs for employers and for health care (direct costs) [23, 37–39]. In particular, insomnia and depression among women with menopausal complaints were associated with productivity loss and higher costs [40, 41]. Possibly, not all women report the ‘real’ reasons for sickness absence or taking a day off [8]. The evidence is however inconclusive. In Hardy et al.’s electronic survey no significant association was found between menopausal status and work-related outcomes such as sickness absence, job performance and turnover intention [42]. Further research is warranted.

3.3Menopause and work ability

High and Marcellino reported that menopausal symptoms, in particular irritability and mood changes, negatively impacted on the job performance of older female employees, although less so for women in managerial positions [43]. In their early studies, Ilmarinen et al. en Tuomi et al. have developed the ‘Work Ability Index’ (WAI), an instrument to assess work demands in relation to the worker’s health and resources [44–46]. They concluded that for older employees, men and women, work adaptations should balance physical and mental job demands, and advocated for research on the potential influence of menopause on work ability. This has been done recently by Geukes et al., who studied healthy working women, representative of the Dutch female population, and showed that women’s physical and psychological menopausal complaints were associated with lower work ability, which increased the possibility of sickness absence [7]. The authors concluded that the women had a relatively low level of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and that these complaints did not negatively impact on their work ability (see also [47]). More recently however, other researchers reported that VMS were the most frequently reported complaints with a negative effect on work [6]. In Jack et al.’s study, women reported that menopausal complaints negatively affected their motivation and commitment to work and increased turnover intention or intention to leave the labour market altogether [32]. In another study, women themselves directly related lower job performance to their menopausal symptoms. They tried to hide their health complaints from colleagues and supervisors by working harder to compensate for lower performance [8]. More recently, Geukes et al. concluded that the risk of reporting low work ability is eight times higher among women who report severe menopausal complaints (including VMS, physical and psychological symptoms), than women who do not report menopausal complaints [1].

3.4Menopause and job characteristics

Generally, work improves women’s mental well-being, since it positively affects self-esteem, health and diminishes psychological stress [1, 14, 48]. Work contributes to women’s quality of life, in particular during midlife: the task of ‘raising children’ is (almost) fulfilled, so there is more room for work and self-development [3]. Job characteristics play an important role in health, in particular autonomy and support. For instance, Bariola et al. found that support from the supervisor, fulltime work, the possibility to regulate temperature in the workplace and autonomy were associated with fewer symptoms [49].

Some studies associate women’s job characteristics with cardiovascular disease, sleeping problems, VMS and depressive symptoms [14, 50–52]. In a Lithuanian case-control study with women who had suffered from myocard infarction, Malinauskiene and Tamosiunas (2010) studied the relationship between menopause, cardiovascular risk and job characteristics [53]. Controlled for socioeconomic position, menopausal women with the lowest autonomy at work had the highest cardiovascular risk, while those in the second and third quartile had a step increased risk. Evolahti et al.’s longitudinal study on the effects of psychosocial job characteristics on menopausal women’s cholesterol levels found that autonomy at work was an important predictor of healthy cholesterol levels [54]. Such results challenge us to take a broader view on the relationship between menopause and work ability, job performance and sickness absence.

3.5Menopause and psychosocial and cultural factors

Sarrel reported a relationship between menopausal health complaints and mental well-being, since menopausal complaints can be experienced as a source of insecurity, anxiety and shame [9]. Hot flashes in particular are experienced as problematic in the workplace, because they have an impact on women’s self-confidence, harming a desired professional image, especially for women with demanding jobs and responsibilities [8, 33, 55]. Besides the association between VMS and work ability, Gartoulla and colleagues found that other factors such as overweight, financial insecurity, being single and having informal care responsibilities are associated with work ability and well-being [6]. According to Griffiths et al., having to hide menopausal complaints can become a stressor in itself [8]. Studies show that experienced stress can increase menopausal complaints [9]. Smith and colleagues suggest that the menopausal women’s assumptions about others’ reactions to hot flashes, may be more negative than is actually the case [56]. The respondents explained visible hot flashes and sweating among menopausal women by other factors, such as health problems, emotions, physical exercise, temperature, etcetera. Hence, the women’s own mindsets and convictions about menopause deserve more attention in research.

Jack et al. analysed the embodied experiences of women in relation to their work at Australian universities and identified three time-related themes [57]. First, some women described menopause as a ‘period of time’: menopause could be a time for reflection, a time for a second chance and renewed ambitions, or a time when women put the organisation where they work in ‘its place’ and put themselves central. Second, some women described menopause rather as a ‘spiral’, since their bodily experiences during menopause were not in line with time, as required by the organisation: unpredictable hot flashes or severe menstruations that require regular toilet visits create confusion and discomfort during travels, planned meetings, or education activities that were planned months in advance. Small tokens of appreciation and recognition, such as access to ventilated places, make women feel more relaxed at work, while denial of their experiences aggravate physical symptoms. And third, new alliances developed around menopause –with mothers, colleagues, supervisors, the organisation itself. New meanings were created about relations among women, in which silence about menopause was loudly heard in the realisation of shared physical experiences. The women reflected on the past, looked back at their mothers’ lives, but also at their future: how to maintain one’s position in the labour market until the retirement age, and what they need to achieve it.

3.6Menopause and health in relation to work

A vast amount of research focuses on menopause and health problems, such as the relationship between depression and VMS [e.g. 22]or sleeping problems, which can affect women’s work [e.g. 58]. Malinauskiene and Tamosiunas studied the association between menopause and cardiovascular risk profiles among working Lithuanian women [53]. They concluded that smoking, alcohol consumption and other psychosocial factors must be incorporated when developing cardiovascular risk profiles for menopausal women. Some evidence exists about a relationship between depression, sleeping problems and night sweats, but the mechanisms behind this relationship are unclear [14, 52]. Worsley et studied the association between moderate to severe VMS and moderate to severe depressive symptoms, using data collected by Gartoulla et al. [6, 59]. Moderate to severe VMS were independently associated with depressive symptoms, after controlling for age, BMI, relationship status, education, job status, informal care, the financial and living situation and the use of Hormone Suppletion Therapie (HST).

One of the few longitudinal studies by Woods and Mitchell describes women’s experiences over the course of 18 years regarding interference at work and interference in social relations in relation to age, menopausal status, experienced stress, cortisol levels, self-reported health, as well as variety of menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, sleeping problems, depressive mood and memory loss [19]. The influence of the symptoms on work (experienced interference) and on relations, was assessed by analysing observations collected in menstrual calendars, annual health reports, morning urine samples and symptom ratings from diaries. First, Woods and Mitchell conclude that good self-reported health is associated with less interference of menopausal symptoms at work [19]. This is also the case for self-reported stress, but not for cortisol levels. Concentration problems and a depressive mood influence both work and social relations at work, even when self-reported health and self-reported stress are accounted for. The main symptoms that interfered with work and social relations were a depressed mood and difficulties with concentrating. Menopause itself does not interfere heavily with daily life, according to the researchers.

3.7Menopause and mental health: stress, fatigue, and burnout

In their longitudinal study, Mishra and Kuh pointed out that job stress is one of the main risk factors for lower quality of life among menopausal women [21]. Gujski et al. studied job stress in relation to cognitive functioning (aspects of memory, psychomotor speed, reaction time, complex attention, cognitive flexibility, processing speed etc.) among Polish peri- and postmenopausal female intellectual workers and found correlations between the cognitive functions and the stress-inducing factors at work [60]. The social contacts at work, a lack of rewards and support and the psychological load due to complexity of work were the main reasons for stress. Especially among women in postmenopausal period negative correlations were found between the majority of the cognitive functions and intensity of stress, and the majority of stress-inducing factors.

Matsuzaki et al. looked into the association between menopausal symptoms and job stress among Japanese nurses aged 45–60 years [61]. Most nurses reported less energy, irritability and concentration problems. Nurses in managerial positions felt unhappier and cried more often. They reported that the stress they experienced was related to overburdening at work. This indicates that differentiating between professions and functional levels is useful.

Verdonk et al. studied the prevalence and determinants of the need for recovery after work among Dutch employees. In particular, highly educated women aged 50–64 reported a high need for recovery, which was associated with working conditions, including high job demands and low autonomy in combination with lower self-reported health [5]. Chronic stress or long-term work-related fatigue can result in stress or burnout [20]. Health complaints associated with burnout can be similar to health complaints associated with menopause: fatigue, sleeping problems, cognitive problems such as concentration problems and memory loss, rumination and emotional problems such as irritability and emotional instability. Such health complaints are non-specific, are associated with high job demands and problems related to work, whereby long-term fatigue or exhaustion are the main issue. Chronic fatigue is also associated with other (severe) health complaints. Menopause and burnout are easily confused, by women themselves and by health professionals, which delays adequate health care [11].

3.8Menopause and coping and interventions

3.8.1Individual coping strategies

Various individual coping strategies are described in the literature [2, 8, 33]. For sleeping problems and possible consequences, such as fatigue, solutions are not simple. Coping with hot flashes is often resolved by bringing extra clothes, dressing in ‘layers’, or bringing along a (mini) fan. Sometimes, windows can be opened, or women refresh themselves in bathrooms. Strategies for concentration problems or forgetfulness are for instance double checking one’s work or making to do lists. Adapting tasks or changing work schedules are also mentioned. Other coping strategies, more lifestyle-oriented, are changes in diet, (extra) exercise or sleeping extra hours [2, 8, 33].

The use of humour or talking about menopause with other people is mentioned least often by women themselves [8]. Less beneficial coping strategies that some women use, are for instance working extra hard in order to make up for the ‘shortcomings’ that result from menopausal complaints, compensating hours or hiding these ‘shortcomings’, taking sick leave or holidays without mentioning the real reasons [2, 33]. In short, strategies directed at adjustment in the workplace and openness seem to be used less often than strategies that focus on coping with or diminishing the complaints.

3.8.2Interventions aimed at women

HST is a contested issue, because it raises questions regarding contraindications or a lack of clarity about the long-term health effects [62–66]. More and more attention has been paid to non-hormonal treatment in order to diminish VMS or depression, such as lifestyle interventions e.g. diet or non-hormonal medication [for an overview see 67]. Cognitive and behavioural therapy and mindfulness-based therapy continue to play a role in the treatment of health complaints related to menopause, in particular to depressive symptoms [68, 69]. Few studies associate therapeutic support with women’s work ability. In 2016, Hunter et al. published a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial to study the effects of a self-help intervention based on cognitive behavioural therapy for menopausal complaints [70]. They expected that diminishing VMS and night sweats would lead to less sickness absence and presenteeism, lower job stress levels and turn over intention, and higher job satisfaction and productivity. The intervention consisted of a four-week programme based on psychoeducation, relaxation and breathing exercises, cognitive exercises and other suggestions. Results were published in Hardy et al.’s later study, which indeed showed a positive effect of cognitive behavioural therapy on VMS and night sweats as well as on job performance, and a negative effect on presenteeism [71].

In a retrospective cohort study, Geukes et al. stu-died the relationship between (improvement of) severe menopausal symptoms and work ability among working women [72]. The women, who visited a menopause clinic for the first time, were followed for 3–9 months. First, they were offered an intervention consisting of a 60-minute intake about menopausal symptoms and lifestyle with a specialist nurse, a consultation with a gynaecologist to support decision-making about treatment and a short follow-up consultation with the gynaecologist. In the following 3–9 months, a second consultation took place with the nurse. Most women reported improved work ability during follow-up, and all women reported fewer complaints. In the Finnish study, Rutanen et al. looked into physical exercise and its effects on i.a. women’s work ability [73]. After six months of aerobics training, the participating women showed improved mental health outcomes and decreased physical demands compared with the control group, but no differences in WAI scores. Studies of such interventions are scarce.

Ariyoshi conducted an evaluation study (survey and case study) among female journalists, administrative and sales representatives who worked or had worked for a Japanese media company [74]. Women’s menopausal complaints were the reason to participate in the study. Data about consultation with a nurse, three case studies, and the number of sick days related to menopause were collected and assessed. After the intervention, sick leave related to menopause had diminished, as well as turnover. The study showed that a specialist nurse and human resource management can play an important role by developing and offering tailored interventions for working women going through menopause.

3.8.3Interventions aimed at the workplace

The British UNISON’s (The Public Service Union) guide to menopause states that menopause is too often considered to be a private issue instead of an occupational health issue [75]. According to UNISON, employers should realise that women going through menopause may need special support to continue working and be productive [75]. Griffiths et al. state that at least four issues need to be addressed [8, 76]: (1) awareness among supervisors that menopause can cause problems at work, (2) flexible schedules, (3) access to information and resources, and (4) temperature and ventilation at work. According to Fenton and Panay, offering awareness training to supervisors can be useful [33]. They emphasise the importance of a positive attitude and organisational culture, which offers a safe environment for women to address menopausal complaints. There should be options to talk with a confidential advisor, preferably a female colleague with experience, because women feel uncomfortable addressing these issues with their (male) supervisor [2]. These authors advocate for flexible sick leave procedures in case of menopausal complaints, and warn against the negative consequences of sick leave. Policies directed at taking (extra) breaks or leaving early when menopausal complaints occur, are also suggested as improvements of a sustainable working environment that takes menopause as a phenomenon seriously [33].

Hickey et al. studied the relationship between menopausal symptoms as measured with the Menopause Rating Scale (MRC) and work-related outcomes such as job performance, frequency of mistakes, autonomy and turnover intention [14]. Symptomatic women received a number of suggestions for possible support. Addressing temperature control, flexible hours, seminars about healthy ageing, flexible work spaces, physical exercise programs and table fans were the most attractive to the participants. Organisations benefit from policies directed at healthy ageing, and the working environment must be designed to not exaggerate menopausal symptoms. Furthermore, specific needs of women in menopause deserve attention in risk-inventories and evaluations.

Studies show that menopausal complaints are affected by situational factors and can be aggravated by the work environment [8, 13, 42]. Hardy et al. studied female employees’ perspectives on their employers [13]. For some women it was difficult to deal with menopause in the workplace, partly due to aspects of the work environment such as lack of knowledge or awareness among colleagues, a lack of communication skills among employees and employers and the lack of organisational policies. This was in line with other studies, and organisational policies for women in this stage are helpful [2, 13, 14, 76–78].

Hardy et al.’s recent work describes a first attempt to address difficulties with talking about menopause [79]. In their study, the supervisors of three large British organisations (one public and two private) received a 30-minute online training with the aim to raise awareness, increase knowledge and improve attitudes towards menopause, and to develop their skills in communication about menopause with employees. Most of the trainees would recommend the training to colleagues.

4Discussion

4.1State of the art

Menopause in relation to work is hardly studied, but the number of studies is increasing [4, 77]. The first cautious conclusions from our findings are: (a) menopause can play a role in diminished work ability of women in this life stage but evidence is inconclusive; (b) menopausal complaints could be a likely explanation for older women’s higher sickness absence rates; (c) women with menopausal complaints continue to work (presenteeism), and (d) women remain silent about their menopausal complaints (taboo) and seek individual solutions to cope with work.

In particular, work ability among women with severe menopausal complaints may be negatively affected [1]. Negative consequences of diminished work ability are sickness absenteeism, turnover intention and other health related issues. At the same time less favourable working conditions, such as the lack of job autonomy or a lack of control over the physical working environment, seem to negatively affect menopausal complaints [42, 49]. Women use several individual strategies to cope with menopausal complaints at work which can be more (healthy lifestyle changes) or less adequate (working more hours to make up for lower productivity). Such interventions at an individual level (self-help interventions) and at the workplace (e.g. educating supervisors) could be successful. They are positively valued, by women themselves and also by supervisors [8, 71]. Menopause is hardly discussed in the workplace, which is related to the taboos surrounding menopause, as well as to the lack of knowledge by the women themselves, health care professionals and employers [35, 79].

Organisational policies about menopause and work are hardly described. Further stigmatization of (older) women needs to be avoided when menopause at work and its taboo are being addressed –a leap from women’s work-related health problems to women themselves being a problem is easily made. We conclude that menopause is rather seen as a woman’s individual problem than as an organisationally and societally relevant issue. The lack of knowledge about the relationship between menopause, work and health directly affects women’s health as well as their position in the labour market, since they are not offered workplace interventions or professional support. Individual solutions of women can (continue to) lead to diminished well-being at work and eventually to distancing from or leaving the labour market altogether [40]. However, work is essential not in the least for women’s economic independence also in midlife and in old age. For both men and women, work is a source of self-fulfilment, health, self-development, self-confidence, and empowerment [80]. However, the lack of attention for menopause in research and organisational policies gives the impression that older women’s work and health are taken less seriously and are found less important. We conclude that the resilience of working women in this life stage is very high, but it is put under pressure in times of increasing intensification of work, an ageing labour market population and labour market shortages. Good health is important for women’s sustainable employment and a dignified life during retirement, but also for the work organisation and society as a whole. Menopause in relation to work requires serious consideration, both in research and policy at all levels.

4.2Knowledge gaps and directions for new research

Based on this literature review we identified several knowledge gaps.

First, we need to understand why a topic that is relevant to (almost) all working women is systematically being ignored in research and in organisations. Women’s health issues such as menopause and reproductive health, breast cancer or endometriosis, but also sexual or intimate partner violence, are major public health matters [81]. Gender bias in medicine has been described for decades already and women’s health advocates have called for integration of women’s health in research agendas and curricula [81]. Our review indicates that epistemic injustice in organisational and health research is still effectively in place. The taboo on menopause that is referred to in studies is reinforced by women themselves, but this takes place in a context which values (women’s) youth over midlife, mind over body and productivity over reflection [82].

Second, menopause must be studied in relation to: (a) physical working conditions, such as temperature and ventilation, but also nightshifts, working with chemical substances and physical requirements such as heavy lifting, and (b) health issues later in life. In order to provide women with the opportunities to live up to their potential, we need to know how psychosocial working conditions, such as coping with menopausal complaints at work, or the relationship between menopausal complaints and job demands and job autonomy, or social support, are associated with menopausal complaints and with health problems such as cardiovascular conditions later in life. At organisational and policy level, it is important that we understand how organisations and work can be designed in ways that support sustainable employment of women in this life stage, including women with severe menopausal complaints.

Third, we need comparative studies about the relationship between menopause and work across professions and sectors, but also across cultures. Most of the incorporated studies concern women who work in education and health care, or conduct administrative work, which reflects gender segregation in the labour market [80]. However, specific studies are required on the health and experiences of women during menopause, not just in the ‘female-typed’ sectors, but also in sectors where women represent a minority such as the military, the police force and the industry [83]. Being member of a minority group may bring about even more complex issues regarding menopause and health. In this respect we point for instance towards Gnudi et al.’s work, in which the authors explore the relationship between lifelong physical job demands and retired women’s lower back pain [84]. The study was not included in this review, because the relationship between work and health is only indirectly related to menopause. However, the authors did address professions that were characterised by heavy physical job demands (carrying, pushing, lifting heavy weights) in sectors where women work, such as farming, ceramics and glass industry, paper production and steel industry. In our review, we only found few examples of studies that associated menopause with a particular profession, such as Ilmarinen et al.’s study [44]. In a small number of studies such as Ariyoshi’s study or Cau-Bareille’s study about the motivations of female kindergarten teachers for early retirement, attempts were made to connect experiences with menopause to (quitting) work [74, 85]. However, these were small studies. Chau et al. searched for studies on night shifts and women’s reproductive health in CINAHL, MEDLINE and other databases using the search terms ‘shift-work’ and ‘female/women’[86]. They identified 20 articles related to pregnancy, fertility and the menstrual cycle and zero results related to menopause and work. We support their urgent call to critically evaluate research agendas regarding changing labour market demographics and expected upcoming labour shortages. Breast cancer in women has been studied in relation to night shifts [87]. Other research could focus on wearing uniforms in relation to hot flashes, negative stereotypes that hamper women’s functioning and exclusion of women in ‘typical male’ environments, or the intersection of sexism and ageism towards working women during menopause. Comparative intercultural studies are lacking as well. In 1996, Kaufert already wrote that studies on menopause conducted outside of the United States or Europe, often use similar methodological research designs, whereas the cultural, economic and social context on other continents is very different, including the role of ageing women in societies [34, 88, 89]. Existing knowledge is to a large extent based on white, middle class, urban and mostly healthy women. Research methods and recommendations for practice require accommodation to multicultural societies.

Fourth, there is a need for innovative methodological and theoretical frameworks. Most available studies used instruments such as GCS, WAI, MENQOL, assessing both biomedical and psychosocial aspects of menopause. Since these domains cannot be separated, we need research instruments that do justice to the complexity of the relationship between work and menopause. Studying work and menopause is far from simple. As moving targets, menopause and menopausal complaints pose difficulties for researchers to demarcate menopause as a life stage during the life course, but also to demarcate menopausal complaints in relation to other health complaints. These complexities show the different layers of menopause as a phenomenon, the study of which requires further development of methodological and theoretical frameworks. Jack et al. address this gap and advocate for research from a feminist perspective [57]. Their study is an example of how the approach to studying menopause and work can be extended from a single biomedical endocrinological perspective (hormone fluctuations) or a psychological perspective (individual coping and self-management approaches) to a broader framework. We firmly believe that research on menopause and work will benefit from a transdisciplinary approach, preferably from an intersectional perspective [e.g. 81]. Therefore we advocate for a broader methodological framework, which incorporates the use of existing scales and instruments but also mixed-method research designs, as well as narrative, ethnographic and participatory action research designs with stakeholder and end-user approaches [90]. Participatory research is suitable to map multiple perspectives and bring about a dialogue between employers, employees and other stakeholders about experiences, problems and possibilities for support, for instance in the form of adapted HR-policies [91].

Given the many open endings, our recommendations for practice need to be taken with caution. Based on our literature review, we do recommend that: (a) awareness about menopause and work is raised among occupational health professionals, including physicians, by developing guidelines for menopause and work; (b) organisations map health problems, job characteristics and sickness absenteeism in relation to female-specific life stages, and (c) a broad awareness raising programme about menopause at work is developed for employers, employees and the public at large.

4.3Strengths and limitations to the study

A main limitation to the review is the small number of available studies. That is why we incorporated studies of all qualities, which affects the robustness of our findings. Authors tend to refer to each other, which poses the risk that conclusions from a single study are generalised and exaggerated. Available studies are often based on known scales and instruments, often self-report, such as the WAI, and used in Western settings, but not necessarily validated for women in menopause and not validated cross-culturally. The results of the studies usually only indicate the possible negative effects of certain physical symptoms such as VSM and sleeping problems, and of certain psychological symptoms such as stress, anxiety and shame, on women’s work ability and their well-being. Positive aspects of menopause and ageing in relation to work are not studied. Furthermore, these instruments do not necessarily tap into women’s lived experiences. Other types of research may provide insight in women’s embodied experiences in this life stage within the context of women’s lives.

5Conclusion

Our review is one of few literature studies on menopause, work and health [77]. Even though the number of studies on the subject has been increasing during the past years, we still consider the scarcity of studies on menopause, health and work as an epistemic gap. Our critical stance does not diminish the relevance of the studies that were conducted during the past 20 years, and the outcomes of the pioneering studies incorporated in this review help us move forward and stimulate further research. The resilience of working women in this life stage is very high, but under pressure. Good health is important for women, for the work organisation, and for society as a whole. Menopause in relation to work requires serious consideration, both in research and policy at all levels.

Funding

This study was funded by WOMEN Inc. and Instituut GAK (2018-2019).

Conflict of interest

None to report.

Supplementary material

[1] The appendix is available from https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/WOR-205214.

References

[1] | Geukes M , Van Aalst MP , Robroek SJ , Laven JS , Oosterhof H . The impact of menopause on work ability in women with severe menopausal symptoms. Maturitas. (2016) ;90: :3–8. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.05.001. |

[2] | Kopenhager T , Guidozzi F . Working women and the menopause. Climacteric. (2015) ;18: :372–5. 10.3109/13697137.2015.1020483. |

[3] | Sarrel PM . Working women and the menopause. Climacteric. (2015) ;18: :372–5. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1020483. |

[4] | Griffiths A . Improving recognition in the UK for menopause-related challenges to women’s working life. Post Reprod Health. (2017) ;23: :165–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053369117734714. |

[5] | Verdonk P , Hooftman WE , Van Veldhoven MJPM , Boelens LRM , Koppes LLJ . Work-related fatigue: the specific case of highly educated women in the Netherlands. Int Arch Occup Environ Med. (2010) ;83: :309–21. doi-org.vunl.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s00420-009-0481-y. |

[6] | Gartoulla P , Bell RJ , Worsley R , DavisSR . Menopausal vasomotor symptoms are associated with poor self-assessed work ability. Maturitas. (2016) ;87: : 33–9. |

[7] | Geukes M , Van Aalst MP , Nauta MCE , Oosterhof H . The impact of menopausal symptoms on work ability. Menopause. (2012) ;19: :278–82. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31822ddc97. |

[8] | Griffiths A , MacLennan SJ , Hassard J . Menopause and work: An electronic survey of employees’ attitudes in the UK. Maturitas. (2013) ;76: :155–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.07.005. |

[9] | Sarrel P , Rousseau M , Mazure C , Glazer W . Ovarian steroids and the capacity to function at home and in the workplace. Ann NY Acad Sci. (1990) ;592: :156–61. doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb30323.x. |

[10] | Ballard KD , Kuh DJ , Wadsworth MEJ . The role of the menopause in women’s experiences of the “change of life”. Sociol Health Illness. (2001) ;23: :397–424. doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00258. |

[11] | Dillaway H . When does menopause occur, and how long does it last? Wrestling with age and time-based conceptualizations of reproductive aging. NWSA J. (2006) ;18: (1): 31–60. |

[12] | Craig BM , Mitchell SA . Examining the Value of Menopausal Symptom Relief Among US Women. Value Health. (2016) ;19: : 158–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.11.002. |

[13] | Hardy C , Griffiths A , Hunter MS . What do working menopausal women want? A qualitative investigation into women’s perspectives on employer and line manager support. Maturitas. (2017) ;101: :37–41. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.04.011. |

[14] | Hickey M , Riach K , Kachouie R , Jack G . No sweat: managing menopausal symptoms at work. J Psychosom Obst Gyn. (2017) ;38: :202–9. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2017.1327520. |

[15] | Currie H , Williams C . Menopause, cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. US Cardiol Rev. (2008) ;5: : 12–14. |

[16] | Zhu D , Chung HF , Dobson AJ , Pandeya N , Giles GG , Bruinsma F , Brunner EJ , Kuh D , Hardy R , Avis NE , Gold EB , Derby CA , Matthews KA , Cade JE , Greenwood DC , Demakakos P , Brown DE , Sievert LL , Anderson D , Hayashi K , Lee JS , Mizunima H , Tillin T , Simonsen MK , Adami H-O , Weiderpass E , Mishra G . Age at natural menopause and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Public Health. (2019) ;4: :e553–e564. doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30155-0. |

[17] | Rossmanith WG , Ruebberdt W . What causes hot flushes? The neuroendocrine origin of vasomotor symptoms in the menopause. Gynecol Endocrinol. (2009) ;25: :303–14. doi.org/10.1080/09513590802632514. |

[18] | Irni S . Cranky old women? Irritation, resistance and gendering practices in work organizations. Gender Work Org. (2009) ;16: :667–83. doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00455.x. |

[19] | Woods NF , Mitchell ES . Symptom interference with work and relationships during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause. (2011) ;18: :654–61. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e318205bd76. |

[20] | Verdonk P . Werkstress, overspannenheid en burn-out. In: Van Amelsvoort T, Bekker M, Van Mens-Verhulst J, Olff M, editors). Handboek Psychopathologie bij vrouwen en mannen. Amsterdam: BOOM; (2019) , pp. 379–390. |

[21] | Mishra G , Kuh D . Perceived change in quality of life during the menopause. Soc Sci Med. (2006) ;62: :93–102. http://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.015. |

[22] | Wariso BA , Guerrieri GM , Thompson K , Koziol DE , Haq N , Martinez PE , Rubinow DR , Schmidt PJ . Depression during the menopause transition: impact on quality of life, social adjustment, and disability. Arch Womens Mental Health. (2017) ;20: :273–82. doi.org/10.1007/s00737-1003016-0701-x. |

[23] | Whiteley J , Di Bonaventura M , Wagner JS , Alvir J , Shah S . The impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life, productivity, and economic outcomes.Womens Health. (2013) ;22: (11): 983–90. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3719. |

[24] | Ayers B , Forshaw M , Hunter MS . The impact of attitudes towards the menopause on women’s symptom experience: a systematic review. Maturitas. (2010) ;65: :28–36. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.10.016. |

[25] | TUC. The menopause: a workplace issue. A report of a Wales TUC survey investigating the menopause in the workplace. Cardiff: Wales Trade Union Congress Cymru, (2017) [cited 2019 May 17]. Available from https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Menopause%20survey%20report%20FINAL_0.pdf. |

[26] | Field-Springer K , Randall-Griffiths D , Reece C . From Menarche to Menopause: Understanding Multigenerational Reproductive Health Milestones. Health Comm. (2018) ;33: :733–42. doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1306910. |

[27] | Morris ME , Symonds A . ‘We’ve been trained to put up with it’: Real women and the menopause. Crit Public Health. (2004) ;14: :311–23. doi:10.1080/09581590400004436. |

[28] | Dennerstein L , Leher P , Dudley E , Guthrie J . Factors Contributing to Positive Mood during the Menopausal Transition. J Ner Ment Dis. (2001) ;189: :84–9. |

[29] | Atwood JD , Mcelgun L , Celin Y , Mcgrath J . The Socially Constructed Meanings of Menopause: Another Case of Manufactured Madness? J Couple Rel Ther. (2008) ;7: :150–74. doi.org/10.1080/15332690802107156. |

[30] | Ulacia J , Paniagua R , Luengo J , Gutiérrez J , Melguizo P , Sánchez M . Models of intervention in menopause: Proposal of a holistic or integral model. Menopause. (1999) ;6: : 264–72. |

[31] | Grant MJ , Booth A . A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. (2008) ;26: :91–108. doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. |

[32] | Jack G , Pitts M , Riach K , Bariola E , Schapper J , Sarrel P . Women, work and the menopause: releasing the potential of older professional women. Melbourne: La Trobe University;2014 [cited 2019 May 17]. Available from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resourcefiles/2014-09/apo-nid41511.pdf. |

[33] | Fenton A , Panay N . Menopause and the workplace. Climacteric. (2014) ;17: : 317–8. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.932072. |

[34] | Hammam RAM , Abbas RA , Hunter MS . Menopause and work - The experience of middle-aged female teaching staff in an Egyptian governmental faculty of medicine. Maturitas. (2012) ;71: :294–300. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.012. |

[35] | Hardy C , Griffiths A , Thorne E , Hunter M . Tackling the taboo: talking menopause-related problems at work Claire. Int J Workplace Health Manag. (2019) ;12: :15–27. doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-03-2018-0035. |

[36] | Rindner L , Strömme G , Nordeman L , Hange D , Gunnarsson R , Rembeck G . Reducing menopausal symptoms for women during the menopause transition using group education in a primary health care setting-a randomized controlled trial. Maturitas. (2017) ;98: :14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.01.005. |

[37] | Fenton A , Panay N . Menopause—quantifying the cost of symptoms. Climacteric. (2013) ;16: :405–6. doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2013.809643. |

[38] | Kleinman NL , Rohrbacker NJ , Bushmakin AG , Whiteley J , Lynch WD , Shah SN . Direct and indirect costs of women diagnosed with menopause symptoms. J Occup Environ Med. (2013) :55: :465–70. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182820515. |

[39] | Sarrel P , Portman D , Lefebvre P , Lafeuille M , Grittner A , Fortier J , Gravel J , Duh MS , Aupperle P . Incremental direct and indirect costs of untreated vaso-motor symptoms. Menopause. (2015) ;22: :260–6. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000320. |

[40] | Bolge SC , Balkrishnan R , Kannan H , Seal B , Drake CL . Burden associated with chronic sleep maintenance insomnia characterized by nighttime awakenings among women with menopausal symptoms. Menopause. (2010) ;17: :80–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181b4c286. |

[41] | DiBonaventura MD , Wagner J-S , Alvir J , Whiteley J . Depression, quality of life, work productivity, resource use, and costs among women experiencing menopause and hot flashes: a cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion CNS. (2012) ;14: (6):PCC.12m01410. doi.org/10.4088/PCC.12m01410. |

[42] | Hardy C , Thorne E , Griffiths A , Hunter MS . Work outcomes in midlifewomen: the impact of menopause,work stress and working environment. Womens Midlife Health. (2018) ;4: :3. doi.org/10.1186/s40695-018-0036-z. |

[43] | High RV , Marcellino PA . Menopausal women and the work environment. Soc Behav Pers. (1994) ;22: :347–54. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.1994.22.4.347. |

[44] | Ilmarinen J , Tuomi K , Klockars M . Changes in the work ability of active employees over an 11-year period. Scand J Work Environ Health. (1997) ;23: (suppl 1):49–57. |

[45] | Tuomi K , Ilmarinen J , Martikainen R , Aalto L , Klockars M . Aging, work, life-style and work ability among Finnish municipal workers in 1981—1992. Scand J Work Environ Health. (1997) ;23: (suppl 1):58–65. |

[46] | Ilmarinen J . The work ability index (WAI). Occup Med. (2007) ;57: :160–160. doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm008. |

[47] | Park M , Sato N , Kumashiro M . Effects of menopausal hot flashes on mental workload. Ind Health. (2011) ;49: :566–74. doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.MS1222. |

[48] | Strauss J . Contextual influences on women’s health concerns and attitudes toward menopause. Health Soc Work. (2011) ;36: :121–7. doi.org/10.1093/hsw/36.2.121. |

[49] | Bariola E , Jack G , Pitts M , Riach K , Sarrel P . Employment conditions and work-related stressors are associated with menopausal symptom reporting among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopause. (2017) ;24: :247–51. |

[50] | Lee KA , Baker F C . Sleep and Women’s Health Across the Lifespan. Sleep Med Clin. (2018) ;13: :xv–xvi. doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.06.001. |

[51] | Sassarini J . Depression in midlife women. Maturitas. (2016) ;94: :149–54. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.09.004. |

[52] | Shaver JL , Woods NF . Sleep and menopause: a narrative review. Menopause. (2015) ;22: :899–915. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000499. |

[53] | Malinauskiene V , Tamosiunas A . Menopause and myocardial infarction risk among employed women in relation to work and family psychosocial factors in Lithuania. Maturitas. (2010) ;66: :94–8. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.02.014. |

[54] | Evolahti A , Hultcrantz M , Collins A . Psychosocial work environment and lifestyle as related to lipid profiles in perimenopausal women. Climacteric. (2009) :12: :131–45. doi.org/10.1080/13697130802521290. |

[55] | Stephens C . Women’s experience at the time of menopause: Accounting for biological, cultural and psychological embodiment. J Health Psychol. (2001) ;6: :651–63. doi.org/10.1177/135910530100600604. |

[56] | Smith MJ , Mann E , Mirza A , Hunter MS . Men and women’s perceptions of hot flushes within social situations: are menopausal women’s negative beliefs valid? Maturitas. (2011) ;69: :57–62. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.01.015. |

[57] | Jack G , Riach K , Bariola E . Temporality and gendered agency: Menopausal subjectivities in women’s work. Human Relat. (2019) ;72: :122–43. doi.org/10.1177/0018726718767739. |

[58] | Guidozzi F . Sleep and sleep disorders in menopausal women. Climacteric. (2013) ;16: :214–9. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.753873. |

[59] | Worsley R , Bell RJ , Gartoulla P , Robinson PJ , Davis SR . Moderate—severe vasomotor symptoms are associated with moderate—severe depressive symptoms. J Womens Health. (2017) ;26: :712–8. doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.6142. |

[60] | Gujski M , Pinkas J , Juńczyk T , Pawełczak-Barszczowska A , Raczkiewicz D , Owoc A , Bojar I . Stress at the place of work and cognitive functions among women performing intellectual work during peri- and post-menopausal period. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. (2017) :30: :943–61. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01119. |

[61] | Matsuzaki K , Uemura H , Yasui T . Associations of menopausal symptoms with job-related stress factors in nurses in Japan. Maturitas. (2014) ;79: :77–85. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.06.007. |

[62] | NICE. Guideline ‘Menopause: Diagnosis and management’. United Kingdom: The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence;(2015) [cited 2019 May 17]. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23. |

[63] | NVOG. Richtlijn ‘Management rondom menopauze’. Utrecht: Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecology; (2018) [cited 2019 May 17]. Available from https://www.nvog.nl/management-rondom-menopauze/. |

[64] | Rees M , Lambrinoudaki I , Cano A , Simoncini T . Menopause: women should not suffer in silence. Maturitas. (2019) ;124: :91–2. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.01.014. |

[65] | Schnatz PF . The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. (2017) ;24: :728–53. doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000921. |

[66] | Utian W , Woods N . Impact of hormone therapy on quality of life after menopause. Menopause.-105. (1098) ;20: –10.1097/GME.0b013e318298debe. |

[67] | Mintziori G , Lambrinoudaki I , Goulis DG , Ceausu I , Depypere H , Tamer Erel C , Perez-Lopez R , Schenck-Gustafsson K , Simoncini T , Tremolloeres F , Rees M . EMAS position statement: Non-hormonal management of menopausal vasomotor symptoms. Maturitas. (2015) ;81: :410–3. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.009. |

[68] | Hunter MS . Correspondence in relation to “EMAS position statement: Non-hormonal management of menopausal vasomotor symptoms.” Maturitas. (2015) ;82: :443. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.08.012. |

[69] | Norton S , Chilcot J , Hunter MS . Cognitive-behavior therapy for menopausal symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats). Menopause. (2014) ;21: :574–8. doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000095. |

[70] | Hunter MS , Hardy C , Norton S , Griffiths A . Study protocol of a multicentre randomised controlled trial of self-help cognitive behaviour therapy for working women with menopausal symptoms (MENOS@Work). Maturitas. (2016) ;92: :186–92. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.07.020. |

[71] | Hardy C , Griffiths A , Norton S , Hunter MS . Self-help cognitive behavior therapy for working women with problematic hot flushes and night sweats (MENOS@Work). Menopause. (2018) ;25: :508–19. doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001048. |

[72] | Geukes M , Anema JR , Van Aalst MP , De Menezes RX , Oosterhof H . Improvement of menopausal symptoms and the impact on work ability: A retrospective cohort pilot study. Maturitas. (2019) ;120: :23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.10.015. |

[73] | Rutanen R , Nygård CH , Moilanen J , Mikkola T , Raitanen J , Tomas E , Luoto R . Effect of physical exercise on work ability and daily strain in symptomatic menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial.Work. (2014) ;47: :281–6. doi:10.3233/WOR-121586. |

[74] | Ariyoshi H . Evaluation of menopausal interventions at a Japanese company. AAOHN J. (2009) ;57: :106–11. doi.org/10.1177/216507990905700305. |

[75] | UNISON The menopause and work. A guide for UNISON safety reps. London: UNISON; (2011) [cited 2019 May 17]. Available from https://southwest.unison.org.uk/content/uploads/sites/4/2018/08/The-menopause-and-work-A-UNISON-Guide.pdf. |

[76] | Griffiths A , Ceausu I , Depypere H , Lambrinoudaki I , Mueck A , Perez-Lopez FR , Van der Schouw Y , Senturk LM , Simoncini T , Stevenson JC , Stute P , Rees M . EMAS recommendations for conditions in the work-place for menopausal women. Maturitas. (2016) ;85: :79–81. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.12.005. |

[77] | Jack G , Riach K , Bariola E , Pitts M , Schapper J , Sarrel P . Menopause in the workplace: what employers should be doing. Maturitas. (2016) ;85: :88–95. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.12.006. |

[78] | Nachtigall LE . Work stress and menopausal symptoms. Menopause. (2017) ;24: :237. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000807. |

[79] | Hardy C , Griffiths A , Hunter MS . Development and evaluation of online menopause awareness training for line managers in UK organizations. Maturitas. (2019) ;120: :83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.12.001.. |

[80] | Verdonk P , De Rijk A . Loopbaansucces en welbevinden van Nederlandse werknemers M/V. Gedrag Organ. (2008) ;21: : 451–74. |

[81] | Verdonk P , Muntinga M , Leyerzapf H , Abma T . From Gender Sensitivity to an Intersectionality and Participatory Approach in Health Research and Public Policy in the Netherlands. In: Hankivsky O, Jordan-Zachery J, editors. The Palgrave Handbook of Intersectionality in Public Policy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; (2019) , pp. 413–432. |

[82] | Bendien E , Verdonk P. Embedded and embodied practices of silencing: looking for a voice for maternal bodies in the workplace. Forthcoming. |

[83] | Griffiths A , Cox S , Griffiths R . Women Police Officers: Ageing, Work and Health. Nottingham: University of Nottingham, Institute of Work, Health and Organisations; (2006) [cited 2019 May 17]. Available from https://www.bawp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Ageing-Police-Officers.pdf. |

[84] | Gnudi S , Sitta E , Gnudi F , Pignotti E . Relationship of a life-long physicalworkload with physical function and lowback pain in retired women. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2009) ;21: :55–61. doi.org/10.1007/BF03324899. |

[85] | Cau-Bareille D . Factors influencing early retirement in a female-dominated profession: Kindergarten teacher in France. Work. (2011) ;40: :15–30. doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2011-1265. |

[86] | Chau YM , West S , Mapedzahama V . Night Work and the Reproductive Health of Women: An Integrated Literature Review. J MidwiferyWomens Health. (2014) ;59: :113–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12052 |

[87] | Verdonk P , Klinge I . Framing cancer risk in women and men. Gender and the translation of genome-based risk factors for cancer to public health. In: Horstman K, Huijer M, Buchheim E, Bultheim S, Groot M, Jonker E, Müller- Schirmer M, Walhout E, Van der Zande H, Townend G, editors. Gender and Genes, Yearbook of Women’s History 33. Amsterdam/Hilversum: Verloren Publishers; (2013) , pp. 53–70. |

[88] | Kaufert PA . The social and cultural context of menopause. Maturitas. (1996) ;23: :169–80. doi.org/10.1016/0378-5122(95)00972-8. |

[89] | Olajubu AO , Olowokere AE , Amujo DO , Olajubu TO . Influence of menopausal symptoms on perceived work ability among women in a Nigerian University. Climacteric. (2017) ;20: :558–63. doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2017.1373336. |

[90] | ICPHR Position Paper 1: What is participatory health research? Version May 2013. Berlin: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research; (2013) [cited 2019 May 17]. Available from http://www.icphr.org/uploads/2/0/3/9/20399575/ichpr_position_paper_1_defintion_-_version_may_2013.pdf. |

[91] | Schofield T . Gender, health, research, and public policy. In: J.L. Oliffe JL, L. Greaves L, editors.) Designing and conducting gender, sex, health research. Los Angeles: SAGE; (2012) , pp. 203–214. |