Worker roles in the open labor market: The challenges faced by people with intellectual disabilities in the Western Cape, South Africa

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Work holds great meaning and benefits beyond just monetary gain for people with intellectual disabilities. It gives these individuals the opportunity to engage in meaningful occupation.

OBJECTIVE:

The purpose of the study was to explore challenges that people with intellectual disabilities (PWID) experience when adapting to their worker roles in the open labor market.

METHODS:

The study used grounded theory as the research design. Five male participants and two key informants participated in the study. Two semi structured interviews were conducted with each one of the seven participants (five PWID and two key informants).

RESULTS:

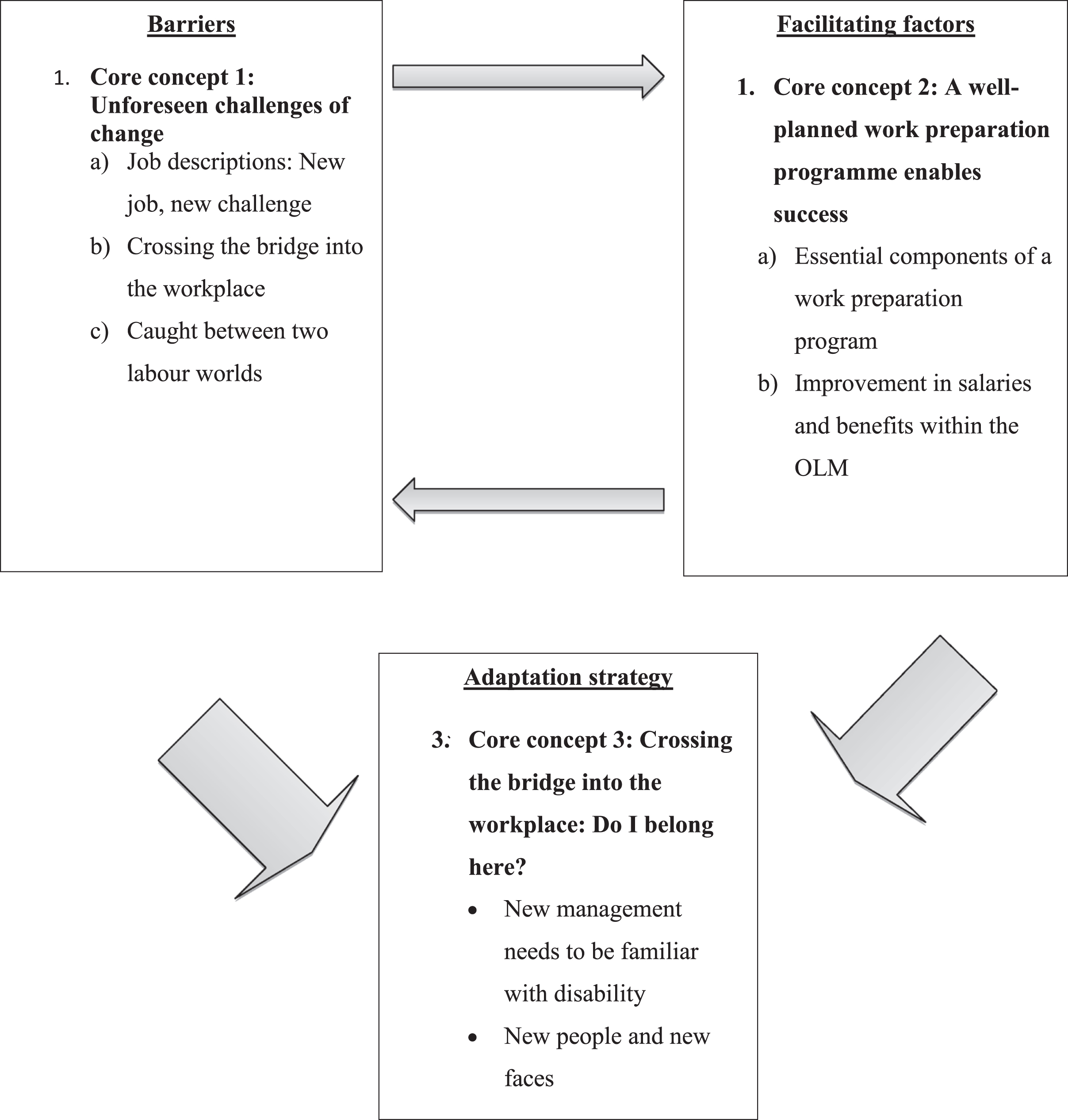

Three core concepts emerged: 1) Unforeseen challenges of change; 2) A well-planned work preparation program enables success and 3) Crossing the bridge into the workplace: “Do I belong here?”

CONCLUSIONS:

This indicated that with sufficient external support, PWID are able to gain a sense of social belonging and develop the necessary skills to cope with challenges that arise in the workplace when PWID transition from protective/sheltered workshops to the open labor market. The findings of the study also indicated that work preparation programs and supportive employment approaches helped PWID transition to the open labor market.

1.Introduction

The persistent high unemployment rate for persons with disabilities is a world-wide concern [1]. A study done in Sweden looking at the living conditions of people with intellectual disabilities (PWID) showed that only 2 out of 110 people with intellectual disabilities (PWID) had some form of paid work [2]. Even greater numbers of unemployed people with disabilities occur in low and middle-income countries, such as South Africa [3]. This is as a result of underdeveloped infrastructure, limited access to high quality education, and a high rate of unemployment of a poorly skilled workforce. Furthermore, few PWID are gainfully employed in the open labor market in South Africa as employers are fearful about employing PWID, possibly due to the stigma related to intellectual disability [4]. Employment of PWID offers the opportunity for social inclusion and a sense of belonging and purpose in their lives [5]. According to the Institute for Research and Development on Inclusion and Society [6], an estimated 99% of people with disabilities are not employed in the open labor market in South Africa. In the South African context there is no research that particularly focuses on the experiences of PWID about adapting to their work role in the open labor market.

2.Literature review

2.1.Facilitators for PWID related to adapting to the open labor market

Facilitating factors such as reasonable work conditions, adjustments, and accommodations in the workplace facilitate an increase in performance and job retention in the open labor market for PWID [7]. Social participation through employment leads to social recognition and the feeling of citizenship among PWID as they interact and build relationships with their co-workers [8]. On a social level, PWID are known as individuals that form a culture that humanize the workplace and contribute to the social connectedness of workers [9]. The findings of the study conducted by Lin [9] revealed that co-workers had feelings of affection and care for the workers with disability. It is evident that social connectedness and support from employers and co-workers are a major facilitating factor in the lives of PWID when adapting to the open labor market.

2.2.Work as an occupation and the meaning it brings to a person with intellectual disability

Current occupational therapy theory states that occupation could be defined as everything that people do in order to occupy themselves [10]. This includes an individual’s self-care, their leisure pursuits, as well as contributing to the social and economic fabric of their communities through work or employment endeavours [10]. According to Bloom [11], researchers have observed a connection between engagement in meaningful occupations and perceptions of being “competent, capable and valuable.” Work also holds great meaning and benefits for people with intellectual disabilities beyond just monetary gain. The study conducted by Conroy, Ferris and Irvine [12] revealed that for a sample of people with intellectual disabilities and developmental disabilities and their support workers their quality of work life improved for both groups. The above authors further stated that their study’s analysis showed that participants experienced an overall increase in quality of working life of about 27%. Some of the facilitators that contributed to the employment of PWID consisted of support from their families, job coaches, work environments with necessary accommodations, employers appreciating the work of PWID, support from an employer and a supportive work organization [13]. Typical barriers that identified could relate to the fact that many PWID may not have any vocational experience after leaving school or may lack work experience [13]. It could be argued that employers may view the latter as barriers especially when employing PWID in the open labor market (OLM) or competitive employment. The results of the latter study provided moderate support to the notion that employment in the open labor market does offer a viable alternative to adult day programs and sheltered workshops for adults with intellectual and developmental disability.

2.3.Laws supporting the rights of people with disabilities

Historically, persons with intellectual disabilities have been denied the right to live in the community, marry, procreate, work, receive an education, and, in some cases, to receive life-saving medical treatment. They have been subjected to incarceration, sterilization, overmedication, and cruel or unusual punishment [14]. Contrary to many African countries, numerous South African policies now address disabilities, including intellectual disability [15]. The South African Constitution makes provision for PWID including policies making provision for social security (disability) grants for children and adults, health security in the form of free primary healthcare for grant recipients as well as tax benefits. People with IDs are entitled to supported decision making where a support in the workplace such as a job coach enables someone with a disability to take and communicate decisions with respect to personal and legal matters [16]. When a legal representation is given to people with ID, namely substitute decision making, the court has the authorized power to make decisions for the PWID. One form of concern remains that despite the employment equity practices having improved in the workplace, employment levels for PWID are very low. Similarly there is minimal research that focuses on the experiences of PWID about transitioning to the open labor market.

3.Aim

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences and perceptions of individuals with intellectual disabilities with regard to adapting to their worker roles in the open labor market.

3.1.Objectives

1. To explore the barriers and facilitating factors experienced by individuals with intellectual disabilities in adapting to and/or working in the open labor market.

2. To explore individuals with intellectual disabilities’ experiences of social belonging and acceptance within the work environment.

4.Research design

The researchers chose to utilize a grounded theory (GT) approach for the research project. Grounded theory is typically used to build theory from qualitative data, whereby data are compared with data i.e. constant comparison [17, 18]. Grounded theory is often conducted for a problem that has not been clearly defined, hence it was utilized by the researcher to explore the challenges PWID experience in the open labor market.

4.1.Study setting and the sampling strategy

This study was conducted at various retail industries. The researchers’ intentions were to get consent from all the research participants; including PWID and their employers who are working in the open labor market. Each participant, including the key informants, were interviewed at their place of work to avoid individuals having to spend time and money on travelling. The five participants came from three different retail industries and were either interviewed during their lunch breaks or during working hours as approved by their respective employers (See Table 1). The two key informants were occupational therapists who were deemed as being knowledgeable in the provision of work related training and the placement of PWID in the OLM. After the initial two interviews with PWID, the data that were generated indicated that occupational therapists would also be able to provide valuable information specifically related to how PWID adapt to their worker roles in the open labor market. The latter contributed to theoretical sampling.

Table 1

Description of the participants

| Participants (P) | Gender (age) | Relationship | Race | Job title | Years of employment in the OLM |

| P 1 | Male (26) | Married | Black | Customer service | 3 years |

| P 2 | Female (23) | Single | Coloured | Packaging | 4 years |

| P 3 | Male (48) | Married | Coloured | Kitchen staff assistant | 10 years |

| P 4 | Male (28) | Single | Black | Maintenance work | 5 years |

| P 5 | Female (22) | Married | Black | Cleaning | 2 years |

| Key informants | |||||

| Name | Gender | Age | Qualification | Years of experience | Place of employment |

| K1 | Female | 59 | BSc (Occupational therapy) | 20 years | Protective workshop |

| K2 | Female | 57 | B Comm degree | 35 years | Sheltered workshop |

The researchers used purposive sampling as a means of recruiting the research participants. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the current study were as follows: PWID had to be employed in protective and sheltered employment before being referred to the open labor market. They needed to be 18 years of age and over, able to communicate in English, Afrikaans or IsiXhosa and to have been employed for at least six months in the open labor market. The exclusion criteria included workers who had dual diagnoses, such psychiatric conditions that would compromise their work ability.

4.2.Data collection

The researchers used semi structured interviews for data collection. Newton [19] states that semi structured interviews allow individuals to disclose thoughts and feeling which are clearly private. The interviewer asked the participants open-ended questions which allowed them to elaborate on their various experiences (please see interview guide). The interviews were audio-taped to make sure an accurate account of the interview could be recorded for analytic purposes. Two interviews were conducted with each research participant inclusive of the key informants. The interviews were continued until saturation of data was achieved.

4.3.Data analysis and rigour

The data were collected and analysed in tandem, the data from the existing interviews were then used to guide subsequent interviews. The data were analysed using the steps outlined by Charmaz [20] and Corbin and Strauss [17]. First the data were analysed into discrete segments (also known as indicators) that were classified under conceptual headings (e.g., this segment is about the barriers that PWID experience when RTW). The researchers coded for similarities and differences in the data, which involved constantly comparing the indicators and concepts with new data that in turn led to new concepts (i.e. open coding). The researcher coded the data in terms of psycho social processes, with an emphasis on what the participants describe themselves as doing and their feelings related to their behaviour. Many lower level codes were labelled using gerunds i.e. whereby the verb form of the code would function as a noun (e.g., Training). The researchers coded for process, i.e. the researcher wanted to determine how the participants would react in different contexts [17]. The researcher then made tentative propositions about the relationships between various emerging categories, specifically focusing on how the variation in context shaped the participants’ experiences (i.e. axial coding). Axial coding enabled the sub categories to explain the categories in more detail. During the coding process the researcher wrote reflexive and theoretical memos (written records of analysis). Memoing enabled the researcher to capture methodological insights and theoretical comparisons about the data that guided theory building. The final aspect of the coding process is known as selective coding, which involves the identification of a core category that incorporates existing categories or supersedes them in explanatory importance. At this stage the relationships between the various categories became evident, this ultimately constituted substantive theory (i.e. theory about how PWID adapt to their worker roles in the OLM). Inductive and deductive approaches to analysis were used in this study.

Strategies such as credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability were used in order to ensure the trustworthiness of the data [21]. Credibility was ensured by the dense description of the lived experience of the research participants and member checking. In the context of this study member checking was conducted as at the end of the two interviews. However at the end of each interview the interviewer provided a summary of the main findings and a final presentation of the study findings were presented to all the research participants individually. The participants agreed with the findings, however also provided some positive suggestions (e.g., the participants felt that there should be a strong emphasis on the utilisation of work preparation programs in order to enhance the work skills of the participants). Transferability was ensured by the detailed description of the research methods, contexts and the lived experience of the participants. Dependability was ensured by means of dense descriptions, peer examination and triangulation. Confirmability was ensured by the process of reflexivity whereby the researcher’s own biases or assumptions were made apparent by means of a reflexive journal.

5.Ethics

Ethics approval was provided by the University of the Western Cape. The research participants were contacted by telephone to explain the aim, purpose and process of the study. The details with regard to the study together with the consent forms were fully disclosed to the participants on arrival at the interview session. All the participants gave written consent to participate in the study, as well as to have the findings of the study published in journals.

6.Findings

6.1.Core concept one: Unforeseen challenges of change

According to the participants, transitioning from a sheltered or a protected workshop into the open labor market calls for change and many adaptations in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities. These changes were viewed as being an unforeseen challenge.

6.1.1.Category one: Job descriptions: New job, new challenge

Any transition to a new job and a new environment is a challenge; however, for people with intellectual disabilities this can be especially challenging given the nature of their diagnosis and working potential.

6.1.1.1. Sub category: New job, new faces. Many of the participants’ most challenging tasks of transitioning into a new work environment were the ‘new job’ and ‘new faces’ [P1] to which they had to adjust. Some participants described it as follows:

“When I got here it was too much difficult. New job, new people you see.” [P1]

“See when you change your job there are more different faces.” [P1]

“In the beginning I was too scared, different people I don’t know I am working with.” [P1]

“I felt a little nervous, because of how the people were going to be like with whom I’ll work with and who they were.” [P2]

6.1.1.2. Sub category: General public’s lack of awareness towards disability. Many of the participants who previously worked with other PWID now had to work with the general public, assisting and selling goods to customers who were not always compliant or patient with them. One participant shared this:

“Sometimes they tell me the customers are always right. They tell you, you must talk with the customers first - whereas the customer is sometimes swearing at me. It’s not alright.” [P1]

6.1.2.Category two: Crossing the bridge into the workplace

Once individuals with intellectual disabilities have been successfully placed in the open labor market, they have to adapt to being exposed to an environment which is no longer designed to cater for their specific needs. This new environment requires longer working hours and different or extra working days such as weekends and/or public holidays.

6.1.2.1. Sub category: Adjusting to longer working hours. The longer working hours required by jobs in the open labor market is a great challenge to people with intellectual disabilities. One participant indicated:

“I used to get up at 7am and now I must get up extra early at 5:45am. This was difficult for me.” [P3]

6.1.3.Category three: Caught in the middle of two worlds

Often people with intellectual disabilities found themselves caught in the middle of a protective world where they are not challenged enough; and the open labor world where they are not skilled enough or fast enough for the job as compared to their respective co-workers.

6.1.3.1. Sub category: Competition amongst co-workers in protective employment. One particular area where participants felt caught in between worlds was that of their previous co-workers and those they currently work with in the open labor market. Although many of the participants experienced job satisfaction, on the other hand, they struggled with co-workers in the open labor market. They were comfortable with people who were more accepting of their disabilities. One participant indicated:

“I like my job but I don’t like some of the ways the workers treat me. They actually want me to work like how some of the other workers work. Fast.” [P3]

6.1.4.Category four: Disability grant (social grants) as an advantage and disadvantage for working in the OLM

Although the participants felt more independent and valuable when moving into the open labor market, the participants realised that they would no longer be given the disability grant they were used to each month. This too made them feel as if they are caught in between the two labor worlds, wondering which in fact would be more beneficial for them at the end of the day. Earning a salary in the open labor market and risking losing the disability grant caused anxiety. A participant said:

“The lady told me my disability grant is going to fall away, I thought what’s going to happen now (raise in anxiety about losing the disability grant)?” [P3]

6.2Core concept two: A well-planned work preparation program enables success

As part of the inclusion criteria, all the participants of this study had been through a work preparation program. This core concept discusses some of the benefits and essential components of the work preparation programs and the improvements in quality of life that came along with the transition into the OLM. One participant said:

“See the supervisor prepared us for it [working in the OLM].” [P3]

6.2.1.Category one: Essential components of a work preparation program

According to the participants and the key informant, the work preparation programs included various components such as work skills training specifically related to the work environment which enhanced work placement.

6.2.1.1. Sub category: Simulated tasks are essential for work placement. All the participants mentioned that they were given simulated tasks as part of their training program which enabled them to gain the necessary skills they needed to cope in the various worker roles. Two of the participants who had both been in the same work preparation program mentioned that they were given the opportunity to train weekends at the workplaces of prospective employers or performed similar tasks within the protective workshops which allowed them to transition into their new jobs. One participant said:

“When I first came I was prepared for this job because the time in [names workshops] I came to work every Saturday for these people [current employer]. I get a lot of advice.” [P1]

6.2.1.2. Sub category: Life skills training. Most of the participants indicated that the additional life skills such as coping skills and conflict management that they were exposed to in the work preparation programs were helpful. One participant said:

“Patience, like here sometimes when I get cross I just, when the people are getting cross I leave it you see. I don’t want to go further. I just come to tell the boss that somebody is making it hard for me.” [P1]

6.2.1.3. Sub category: Work skills training specifically relating to the work environment enhances work placement. The participants expressed their gratitude towards the work preparation programs. They mentioned that not only did the work preparation training provide them with valuable skills; they were also provided with a job that was relevant to their personality and level of functioning. One participantsaid:

“They give you lots of skills; they get you a new job.” [P1]

The participants in this study mentioned that they were able to obtain specific work skills such as punctuality, trustworthiness, concentration, comprehension and retention of instructions, use of material and equipment, initiative/planning of work and neatness. These skills the participants reported were helpful as they were able to receive positive affirmation from their employers and some even received bonuses and promotions for their outstanding work skills and attitudes. One participantsaid:

“He (referring to employer) encourages me, he tells me that I am a good worker and he looks well after me. I like it when he speaks like that to me . . . ” [P3]

6.2.2.Category two: Improvement in salaries and benefits within the OLM

The study’s participants mentioned that they all experienced improved quality of life as a result of the benefits and better salaries and wages. Being employed in the OLM also gave the participants a sense of confidence. The participant said:

“ They (family) are happy, I can now help out with my little girl and don’t have to wait on the grant all the time.” [P5]

6.2.2.1. Sub category: Disability grant is used as a buffer to facilitate the return to work of PWID. According to a key informant, the PWID is given a trial period to adjust to the new job before the disability grant is removed as they earn an increase in wages. He said:

“I remember when the lady told me my disability grant is going to fall away, I thought what’s going to happen now? This is the end of it? But they said no it’s not the end of it because you are going to earn more! And then when I got my wages, my mom was the one who said ‘come on don’t worry about that, look at all the money you have now’. But then I was happy that the money (disability grant) would fall away and I got excited.”[P4]

6.3.Core concept three: Crossing the bridge into the workplace: Do I belong here?

The participants demonstrated a sense of social belonging within their new work environments hence the name of the core concept. Social belonging in the context of the study was viewed as the PWID’s manner of adapting to their worker role in the OLM. Below is a quote from one of the participants who demonstrated how she felt a sense of social belonging in her new work environment. The participant said:

“He encourages me, he tells me that I am a good worker and he looks well after me. I like it when he speaks like that to me because then I feel like I belong here.” [P2]

6.3.1.Category one: New management needs to be familiar with disability

This category describes how most of the managers in the OLM do not understand intellectual impairment, hence they do not know the limitations of PWID. Below is a quote from the key informant explaining how managers lack the knowledge about their employee’s predicament of being intellectually disabled, she said:

“Ok I think employers don’t understand the umm... the way they, they don’t understand the diagnosis so they don’t understand why the intellectually disabled person is behaving the way they are behaving.” [KI]

Employers that are familiar with the functional ability of the PWID positively aided the PWID’s adaptation process. The participant said:

“She was placed with an employer who is one of our service providers so he knows what he has in us and he knows what to expect from our employees, so he has an open mind.”[KI]

6.3.1.1. Sub category: The manner in which the OT facilitates the transition of PWID into OLM. It is the role of the occupational therapists and job coaches to make sure that PWID in the open labor market are placed in the right work task areas for easy handling and staying motivated. Below is a quote from the key informant that demonstrated how vital the assistance from the occupational therapist and job coach is in the transition into open labor market.

“ and that’s where an Occupational therapist is probably one of the best qualified people to guage a person’s level of functioning with umm, align it with the type of job out there.” [KI]

6.3.1.2. Sub category: Work place culture. Every workplace has its own culture that they follow which is going to be different from other workplaces. Below is a quote from one of the participants about how she liked this culture of togetherness in her new workplace which was different from where she used to work. She said:

“At CS (name of the workshop) it’s the people yes, not everyone but just certain people. There is always a case of jealousy [competition] between the people. I don’t like that, I like to work where ladies understand and support each other, you understand ” [P2]

6.3.2.Category two: New people and new faces

This category explains how the transitioning from protective/sheltered workshops into the open labor market for PWID refers to leaving behind friends and other familiar faces. Below is a quote from the key informant, explaining her view on transitioning from a protective/sheltered workshop into the open labor market.

“It’s going to depend on, they could very well feel as outcasts if their co-workers don’t support and sort of marginalize them because they don’t understand them, they don’t want to associate with them.” [KI]

6.3.2.1. Sub category one: Coping with anxiety related to being accepted. In the protective/sheltered workshops PWID work with other people that have similar diagnoses that they have, but in the open labor market they meet people who might not understand their disability which might lead to stereotyping. Below is a quote from one of the participants about how she felt on her first day.

“I felt a little nervous, because of how the people were going to be like with whom I’ll work and who they were.” [P2]

Another participant indicated that the fact that her employer knew about her condition helped reduce her anxiety. She said:

“Yes my supervisor knows my situation and says I shouldn’t be scared to come and talk to her.” [P5]

“Yes they did make adaptations for me such as starting time at work especially when it rains or when there are strikes.” [P5]

7.Discussion

7.1.Barriers

According to the participants, they all experienced anxiety around changing to the new work environment as this required adjustment to a new work setting. There was consensus from the participants reflected that this transition was challenging as they had to adapt to the new physical environment, the work culture and the general public within the open labor market. Most of the participants experienced anxiety that stemmed from the uncertainties of fellow colleagues’ perception of their disability.

The perception from PWID about their colleague’s belief that PWID do not deserve disability grants once they are employed within the open labor market caused concern to them. The disability grant is then seen as an unfair advantage towards PWID as they are seen as people that get double payment as salary from two different sources while being employed. This perception by co-workers was inaccurate in that they did not understand that in the South African legal system, a grant is automatically stopped or reduced once the PWID can earn a market related income. This erroneous belief in turn leads to further discrimination of PWID within the workplace. Work discrimination can be defined as the unjust and negative treatment of workers based on personal attributes that are irrelevant to job performance [22]. The participants described varying degrees of discrimination such as being denied work opportunities or promotions, with no clear explanation; to obvious discrimination such as unfriendly remarks, by colleagues or clients. Another barrier that arose from the findings was based on the core concept entitled “Unforeseen challenges of change”. The main cause of people failing to understand the employability of PWID was noted as a lack of awareness within corporate worlds about the work potential of PWID.

7.2.Facilitators

Core concept three “A well-planned work preparation program enables success”, ‘referring to the essential components of a work preparation program’ as well as the category ‘positive influences that enhance employment opportunities of PWID’ were identified as factors that facilitate the transition of PWID into the open labor market. A work preparation program prepares the individual either to return to work after injury, or begin working in the open labor market for the first time. This program generally begins with profiling, so that the work-related goals of the individual are understood and their strengths and weaknesses are identified [23]. Many of the participants indicated that they were trained on weekends at their various prospective workplaces or performed simulated work tasks which allowed them to transition into their new jobs with ease. These findings corresponded with current literature. According to research conducted by Cramm et al. [24], work preparation programs promote self-development and have a positive effect on the individuals’ well-being, although in different ways for different individuals. According to a key informant of this study, 60% of persons with intellectual disability’s’ levels of functioning varies and needs stimulating activities. These types of activity need to be varied to ensure that they do not get bored with one activity, whereas others feel a sense of comfort in doing repetitive tasks. This suggests that although the task of the occupational therapist of finding the most compatible job for a PWID is not a quick or easy one, the participants in this study gave positive feedback.

7.3Social belonging and acceptance within the work environment

As discussed in core concept three: Crossing the bridge into the workplace: Do I belong here? ‘I feel like I belong here’ there were a number of factors that contributed to the participants developing a sense of social belonging. The participants and the key informant indicated that supportive co-workers and employers who offered help and friendship made them feel wanted and accepted in the workplace. The Department of Labour of South Africa [24] supports these findings by indicating that a person with a disability develops into a well-adjusted, productive worker in an atmosphere of acceptance, co-operation and goodwill. Bates, Goodley and Runswick-Cole [25] argue that if people with learning disabilities are supported in creative ways in the work place then there is a greater chance that they will be productive and less dependent on social support.

7.4.Strategies to promote successful engagement in the workplace

Various strategies had been identified that promoted the successful engagement of PWID in the workplace. The findings of the study indicated that a work preparation program and a supportive employment approach helped PWID transition to the open labor market. Although the participants had created new relationships and trust with their new employers and/or supervisors, many of them confirmed that they would want to keep their existing relationships with the protective and sheltered employed sectors as this provided them with support and encouragement to strive and thrive within the OLM. The participants identified that their transition was made smoother when the occupational therapist orientated them to their new setting in advance and ensured that both the employers and the colleagues were aware of their abilities and limitations in order to provide the PWID with the relevant support in their new job environments. The latter finding is supported by research conducted by Kuznetsova and Yulcin [26], who argue that employers are creating and awareness of PWID by means of streamlining work related policies that enables PWID to be productive in the workplace. Finally it is imperative that PWID participate in a form or work preparation program or that schools or training centers provide PWID opportunities to gain exposure to working in the OLM or competitive employment. PWID and employers will then be able to realistically identify specific areas related to the PWID’s work skills that need improvement. Research conducted by Soeker [28] reinforces the finding that relates to the fact that participation in work test placement enhances the ability of individuals living with disability to adapt to their worker roles.

8.Limitations

A limitation of this study was that the majority of the participants could have been uncomfortable when answering questions, as these interviews took place in their places of employment. However it must be mentioned that the participants chose to meet at their workplaces as it was more convenient to them. Another limitation of the study was that due to the small sample size the findings of this study may not be transferable to similar settings, however this limitation is inherent in qualitative research.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

Appendices

Appendix: Interview guide

Interview guide: Participant

1. Describe what the most difficult part of changing to a new job was for you

2. Explain what you felt on the first day of your current job

3. What do you like most about working in the open labor market and why?

4. What do you dislike most about working in the open labor market and why?

5. When did you feel most supported during your current job and why?

6. Describe your relationship with your colleagues

7. Are there any parts of your current job that you did not feel prepared for when entering the workplace? Explain your answer

8. Are there any changes you would make to your current job right now if you could do so and why?

Interview guide: Key informant

1. Could you describe the challenges that PWID experience when returning to work in open labor market (OLM)?

2. Could you describe the factors that support PWID in returning to work?

3. In your experience and opinion, to what extent can PWID experience social belonging and acceptance within the work environment? In your opinion how do PWID adapt to the work place

4. If work preparation programs could be improved to enhance placement in the OLM, what would you suggest and why.

Fig. 1

Graphical representation of the research findings. Figure 5.1 represents the findings in relation to another as emerged from the core concepts and categories.The diagrammatical representation of the themes that link to each other described the relationship between the barriers and facilitators. The adaptation process of PWID in the OLM is described by a process of the PWID, firstly, being able to identify the barriers that prevents them from enhancing their work related skills and resuming the worker role, secondly, identifying and actively utilising the facilitating factors that supports them in the workplace. The presence of facilitating factors positively facilitated workplace adaptation and the absence of the facilitators negatively affected worker role adaptation. Similarly the presence of barriers negatively influenced workplace adaptation and its absence positively influenced worker role adaptation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants for their participation in the research project. The authors would like to thank the staff of the Department of Occupational Therapy for the support that was provided during this research project.

References

[1] | Wiggett-Barnard C , Swartz L . What facilitates the entry of persons with disabilities into South African companies? Disability Rehabilitation Journal. (2012) ;34: (12):1016–23. |

[2] | Umb-Carlsson O . Living conditions of people with intellectual disabilities: A Study of health, housing, work, leisure and social relations in a Swedish county population, Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 2005. |

[3] | Payne B , Payne B , Payne J . A profile of students receiving counselling services at a university in post-apartheid South Africa. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. (2011) ;23: (2):143–53. |

[4] | Disability Board of South Africa, personal communication, 22 March 2014. |

[5] | Banks P , Dagnan D , Jahoda A , Kemp J , Kerr W , Williams V . Starting a new job: The social and emotional experience of people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. (2009) ;22: (5):421–5. |

[6] | Institute for Research and Development on Inclusion and Society. Employment of People with Developmental Disabilities in Canada: Six Key Elements for an Inclusive Labour Market, Toronto: Institute for Research and Development on Inclusion and Society (IRIS) 2014. |

[7] | Bethesda M . National centre for biotechnology information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. 8600 Rockville Pike. 2013. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/gov/pubmed/23676332. |

[8] | Van Staden AD . A Strategy for the Employment of Persons with Disabilities, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences. University of Pretoria 2011. |

[9] | Lin CJ . Exploration of Social Integration of People with Intellectual Disabilities in the Workplace, Unpublished master’s thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada 2008. |

[10] | Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists Enabling occupation: An occupational therapy perspective Ottawa, ON: CAOT Publications ACE (2002) . |

[11] | Bloom FR . “New beginnings”: A case study in gay men’s changing perceptions of quality of life during the course of HIV infection. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. (2001) ;15: :38–57. |

[12] | Conroy J , Ferris C , Irvine R . Microenterprise options for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: an outcome evaluation. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities. (2010) ;7: (4):269–77. |

[13] | Nevala N , Pehkonen I , Teittinen A , et al. The Effectiveness of Rehabilitation Interventions on the Employment and Functioning of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review. J Occup Rehabil. (2019) ;29: 773–802.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09837-2. |

[14] | Ward T . Putting Human Rights into Practice with People with an Intellectual Disability. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. (2008) ;20: (3):297–311. |

[15] | World Health Organization Atlas global resources for persons with intellectual disabilities, Geneva: World Health Organization (2007) . |

[16] | Dhanda A . Legal capacity in the disability rights conven tion: stranglehold of the past or lodestar for the future? Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce. (2007) ;34: (2):438–56. |

[17] | Corbin J , Strauss A . Basics of Qualitative Research Tech niques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd Edition. London: SAGE. (2008) . |

[18] | Strauss A , Corbin J . Basics of Qualitative Research Tech niques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd Edition. ThousandOaks, CA:Sage.(1998) . |

[19] | Newton N . The use of semi- structured interviews in qua itative research: Strength&weaknesses. Academia. Edu, Share research. 2010. |

[20] | Charmaz K . Constructing Grounded Theory. A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: SAGE. (2006) . |

[21] | Krefting L . Rigour in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. (1991) ;45: :214–22. |

[22] | Chung WD , Williams W , Dispensa F . Validating work discrimination and coping strategy models for sexual minorities. Career Development Quarterly. (2009) ;58: (2):162–70. |

[23] | Jahoda A , Dagnan D , Stenfert Kroese B , Pert C , et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy: from face to face interaction to a broader contextual understanding of change. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. (2009) ;53: (9):759–71. |

[24] | Cramm JM , Finkenflugel H , Kuijsten R , Van Exel NJA . How employment support and social integration programmes are viewed by the intellectually disabled. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. (2009) ;53: (6):512–20. |

[25] | Department of Labour, South Africa2014. People with disabilities in the workplace. Retrieved from http://www.labour.gov.za/DOL/. |

[26] | Bates K , Goodley B , Runswick-Cole K . Precarious lives and resistant possibilities: the labour of people with learning disabilities in times of austerity people with learning disabilities in times of austerity. Disability and Society. (2017) ;32: (2):160–75. |

[27] | Kuznetsova Y , Yulcin Y . Inclusion of persons with disabilities in mainstream employment: is it really all about the money? A case study of four large companies in Norway and Sweden. Disability and Society. (2017) ;32: (2):233–53. |

[28] | Soeker MS . A pilot study on the operationalization of the Model of Occupational Self Efficacy: A model for the reintegration of persons with brain injuries to their worker roles Work. (2016) ;53: :523–34. |