Preclinical model of transcorneal alternating current stimulation in freely moving rats

Abstract

Purpose: Transcorneal alternating current stimulation (tACS) has become a promising tool to modulate brain functions and treat visual diseases. To understand the mechanisms of action a suitable animal model is required. However, because existing animal models employ narcosis, which interferes with brain oscillations and stimulation effects, we developed an experimental setup where current stimulation via the eye and flicker light stimulation can be applied while simultaneously recording local field potentials in awake rats.

Method: tACS was applied in freely-moving rats (N = 24) which had wires implanted under their upper eye lids. Field potential recordings were made in visual cortex and superior colliculus. To measure visual evoked responses, rats were exposed to flicker-light using LEDs positioned in headset spectacles.

Results: Corneal electrodes and recording assemblies were reliably operating and well tolerated for at least 4 weeks. Transcorneal stimulation without narcosis did not induce any adverse reactions. Stable head stages allowed repetitive and long-lasting recordings of visual and electrically evoked potentials in freely moving animals. Shape and latencies of electrically evoked responses measured in the superior colliculus and visual cortex indicate that specific physiological responses could be recorded after tACS.

Conclusions: Our setup allows the stimulation of the visual system in unanaesthetised rodents with flicker light and transcorneally applied current travelling along the physiological signalling pathway. This methodology provides the experimental basis for further studies of recovery and restoration of vision.

Abbreviations

LED | light emitting diode |

ACS | alternating current stimulation |

tACS | transcorneal alternating current stimulation |

EER | electrically evoked response |

LFP | local field potentials |

VEP | visual evoked potentials |

1Introduction

Transcranial alternating current stimulation (ACS) interferes directly with ongoing brain oscillations, modulating them and, as a consequence, influencing cognitive processes (Zaehle et al., 2010; Antal & Paulus, 2013; Hermann et al., 2013; Neuling et al., 2013). Moreover, such non-invasive stimulation may also improve aberrant brain functions (Kirson et al., 2007; Gonzales-Burgos & Lewis, 2008; Burns et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012; Brittain et al., 2013; Laczo et al., 2014).

Another variant of ACS – transorbital alternating current – was used as a treatment for patients with vision loss (Bechtereva et al., 1985; Shandurina et al., 1996; Chibisova et al., 2001). But it was not until recently that systematic, randomized clinical studies were conducted showing therapeutic efficacy of non-invasive brain stimulation to restore (recover) vision in patients with visual system damage (Gall et al., 2011, 2013; Fedorov et al., 2011; Sabel et al., 2011).

While transcranially applied current is known to modulate cortical networks in a top-down manner (Chang et al., 2012; Turi et al., 2013; Cancelli et al., 2015), current injected through the eye stimulates the visual system via the retina and optic nerve, as evidenced by induction of phosphenes in patients (Sabel et al., 2011), where cortical networks may be modulated throughout the brain (Bola et al., 2014), which was also shown in animal studies (Foik at al., 2015). Electrophysiological evidence suggests that transorbital stimulation acts in a more physiological mode because it can induce responses in visual structures similar to visual evoked potential (Potts & Inoue 1968, 1969).

This opens new opportunities to modulate activity in subcortical and cortical visual structures via the eye. However, to understand the underlying mechanisms requires appropriate and meaningful preclinical animal models because only here neuromodulation of oscillations in subcortical structures can be measured. This is of significant interest and there have been even attempts to analyse such current-induced changes in cortico-subcortical connectivity in humans (Polania et al., 2012). However, such clinical studies clearly face methodological limitations.

Besides such functional modulatory action, transorbital ACS has also been shown to protect retinal cells from death, probably by influencing gene expression and release of growth factors (Morimoto et al., 2005, 2007; Ni et al., 2009; Miyake et al., 2007; Henrich-Noack et al., 2013).

However, when using animal models two essential problems arise: Firstly, almost all existing preclinical models of noninvasive brain stimulation use anaesthetized animals (Morimoto et al., 2005, 2007; Ni et al., 2009; Henrich-Noack et al., 2013; Sergeeva et al., 2012). But the very purpose of anaesthesia is to alter brain oscillations to reduce consciousness; hence, if the mechanisms of ACS action is to modulate oscillatory activity (Hermann et al., 2013; Neuling et al., 2013; Antal & Paulus, 2013), anaesthesia will interfere with stimulation effects, which are state-dependent(Silvanto et al., 2008; Sergeeva et al., 2012, 2014; Neuling et al., 2013).

Second, when manipulating the visual system in humans (both normal subjects and patients), stimulation-induced phosphenes are used as a correlate of visual processing and success of stimulation, and phosphene threshold changes are interpreted as excitability changes of visual cortex (Antal et al., 2004, 2011; Paulus, 2011; Kanai et al., 2010). Studies in animals, obviously, can not use phospene perception thresholds as a measure, and the reporting of phosphene intensities in patients is highly subjective and somewhat unreliable. Therefore, we need an objective electrophysiological correlate of electrical stimulation such as the electrically evoked response (EER) which is induced by current and which can be recorded from visual structures (Potts & Inoue 1968, 1969; Shimazu et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2006).

Because an animal model is needed without the interfering effects of anaesthetic agents and with EER as a functional read-out, we developed a new preclinical model of freely-moving rats which has several advantages as it allows long-term, chronic experiments with (i) transcorneal alterning current stimulation (tACS), (ii) recording of local field potentials, (iii) eliciting and recording of visual evoked field potentials, (iv) recording of EER as an oscillation correlate of stimulation, and (v) behavioural testing.

2Methods

Adult Lister hooded rats (N = 24) were kept on a 12-h light – 12-h dark cycle at an ambient temperature of 24– 26 °C and humidity of 50– 60% . Food and water access was ad libitum. All procedures conformed with the requirements of the German National Act on the use of Experimental Animals and local ethics committee approval was obtained.

2.1Surgery

Rats were anaesthetised with ketamine (75 mg/kg, i.p.) and medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) in saline and fixed in a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting, USA). After applying local anaesthetic proparacaine, a scalp incision was made, the periosteum scraped off and the skull surface cleaned with 3% hydrogen peroxide.

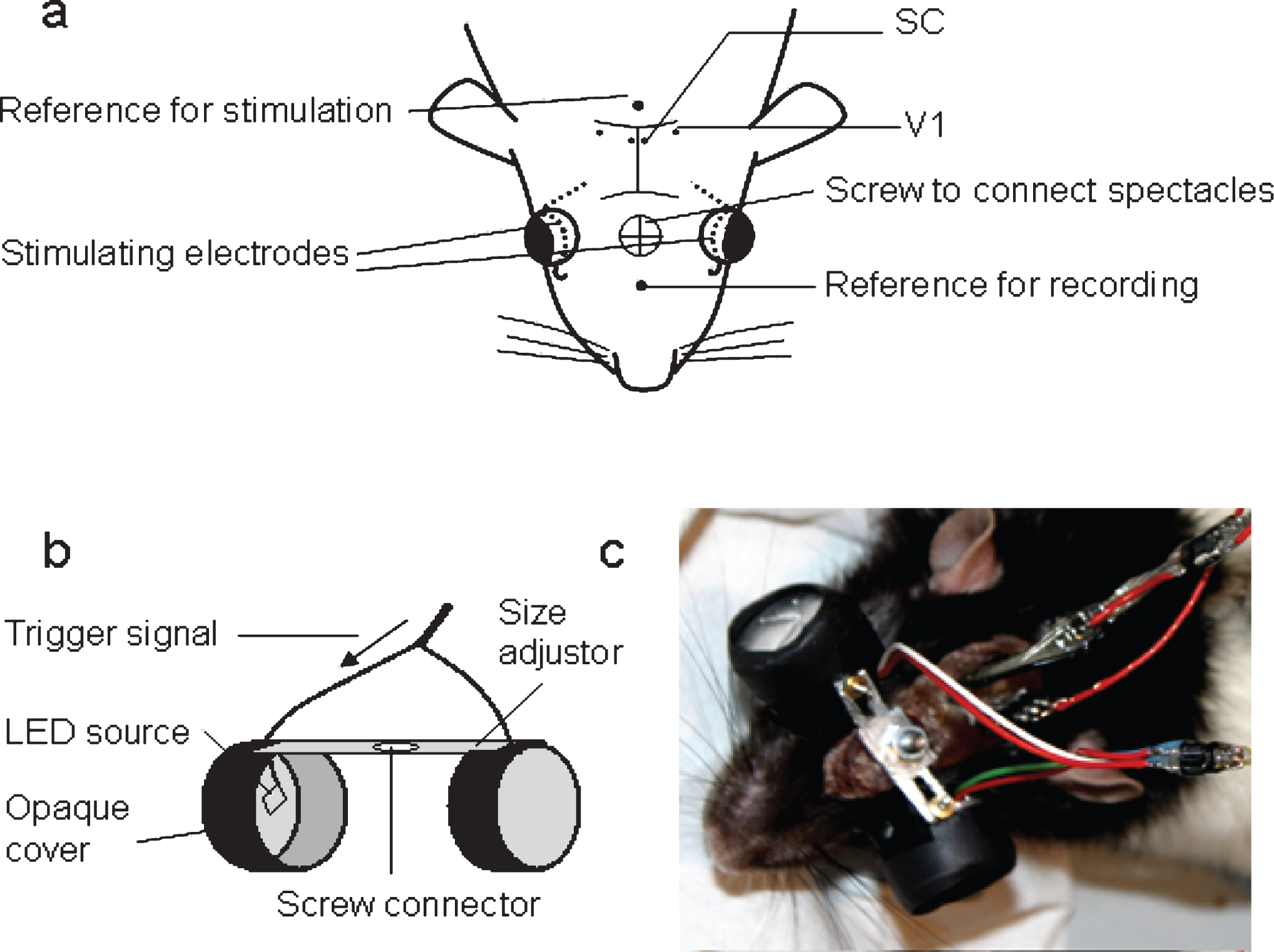

Recording electrodes were custom-made with stainless steel teflon-coated wires 75μm uncoated diameter and 140μm coated (SS-3T/HH; Science products GmbH), impedance range about 100– 500 kohm. They were stereotaxically inserted through a drill-hole in the skull into the brain (after piercing the dura) and implanted bilaterally into the primary visual cortex (7 mm posterior to bregma, 3 mm lateral from midline) and the superficial superior colliculus (6.8 mm posterior to bregma, 1 mm lateral from midline, 3 mm deep) according to Paxinos and Watson (1998). The reference electrode was implanted into the nose bone (Fig. 1(a)).

To prevent that rats could damage or remove the stimulation electrodes we did not use the normally employed technique for transcorneal stimulation in anaesthetised animals, i.e. contact lens- or ring- electrodes, but we rather applied a modified technical concept used for electroretinograms, i.e. a DTL fiber (Dawson et al., 1979) as employed in chronic electroretinogram recordings in rodents (Szabo-Salfay et al., 2001; Guarino et al., 2004). We implanted teflon-coated Platinum-Iridium wires, 50μm uncoated diameter and 114μm coated (101R-2T; Science products GmbH) in each eye, with one end peeled to achieve a 10 mm tip placed onto the cornea-sclera’s surface immediately beneath the upper eyelid. The other end was passed through under the skin to the skull surface (Fig. 1(a)). The eyeball was not pierced and the retina and optic nerve were left intact. A stainless-steel screw with a shaft diameter of 1.17 mm (Fine Science Tools, Heidelberg, Germany) was inserted as a reference electrode into the occipital bone. An additional screw was implanted into the parietal bone to strengthen the fixation of the head stage. All electrodes were connected with pin-sockets (separate for recording and stimulation) and fixed with dental cement.

The eyes and skin around the head stage were treated with Aureomycin antibiotic ointment and the animals were allowed to recover for at least one week before handling procedures started. Bepanthen eye ointment was applied daily during recovery.

2.2Flicker light stimulation

For flicker light stimulation self-constructed metal spectacles with embedded white light LED sources of 2.5 mm diameter (Fig. 1(b)) were fixed on the rat’s head to cover the eyes completely. The spectacles were coated with opaque soft plastic tissue to prevent interference with ambient light, damage of the rat’s skin with sharp edges as well as the static electricity due to scratching off of metal particles. Spectacles were provided with adjustors of the distance for rats of different size so that the light source was about 10 mm from the eye, illuminating the whole visual field. The screw for fixation of the spectacles was mounted into the dental head stage over the nose bone during implantation surgery. Trigger signal to induce flickers was created with isolated pulse stimulator (A-M Systems, USA). Flicker parameters were regulated with those of the pulse. During the experiment the intensity of the light was set to a maximum level corresponding to 1300 mcd. The trigger signal was also sent to the amplifier of the acquisition system as a marker of events for further analysis of visual evoked potentials (Fig. 1(b)). The spectacles were removed after the stimulation so that the rats could be kept under normal visual conditions in their cages between experiments.

2.3Electrophysiology

Data acquisition: The pin-sockets were connected with flexible cables to allow the rat to move around within the box. For recording a preamplifier was connected to the head stage to prevent artefacts from movements. Local field potentials (LFP) recordings were performed under dark room conditions. The signal was bandpass filtered between 0.1 Hz– 2 kHz using an 8-channels Porti system by Twente Medical Systems International B.V. (Netherlands) and digitized with a 2 kHz sampling rate.

For the evoked potentials stimuli were delivered 1 per second. To minimize the artefact after the electrical pulse, the average reference montage for recording of electrically evoked response (EER) was used. Visual evoked potentials (VEP) were recorded using a reference electrode in the nose bone.

Analysis of the LFP data was carried out in Matlab and EEGlab. Evoked responses were averaged over 100 stimulus repetitions. Peak-to-peak amplitude was calculated and monitored in a group of rats (N = 24) during two weeks starting from the 14th day after the surgery to evaluate the stability of implantation and suitability of setup for long-term chronic experiments.

2.4Transcorneal alternating current stimulation (tACS)

To measure EER we used square wave biphasic 2 msec pulses of 300μA intensity, 1 per sec which were generated by an isolated pulse stimulator (A-M Systems, USA). To test tACS tolerance rats were stimulated for 20 min according to the protocol described by Sergeeva et al. (2012).

2.5Handling and observation

After about one week of recovery from surgery rats were placed daily into the experimental box (transparent plastic box 60×60×60 cm) for one week of adaptation to the experimenter and environmental conditions. From the third day on the spectacles were fixed for 30 min daily for habituation and from the fifth day on the cables were connected with the head stage. The condition of the rat was considered as adapted when the animal was not demonstrating any signs of anxiety and tolerated spectacles and cables well.

We monitored the dynamics of eyes’ recovery after implantation of stimulating electrodes, as well as the integrity of wires in the eyes using a microscope.

Figure 1(c) shows the experimental setup for flicker light and current stimulation via the eye with recording of local field potentials in freely moving rats.

3Results

During the post-operative period we observed a decreasing reaction/inflammation around the head stages and in the eyes: 40 out of 48 operated eyes were completely recovered within one week, and the cornea proved not to be damaged by the electrode. After one week of handling, rats were habituated to the experimental conditions and tolerated cables and spectacles without signs of stress or aggravation. Recording was found to be reliable during the 4 weeks of testing. In 41 eyes the implanted electrodes were unbroken.

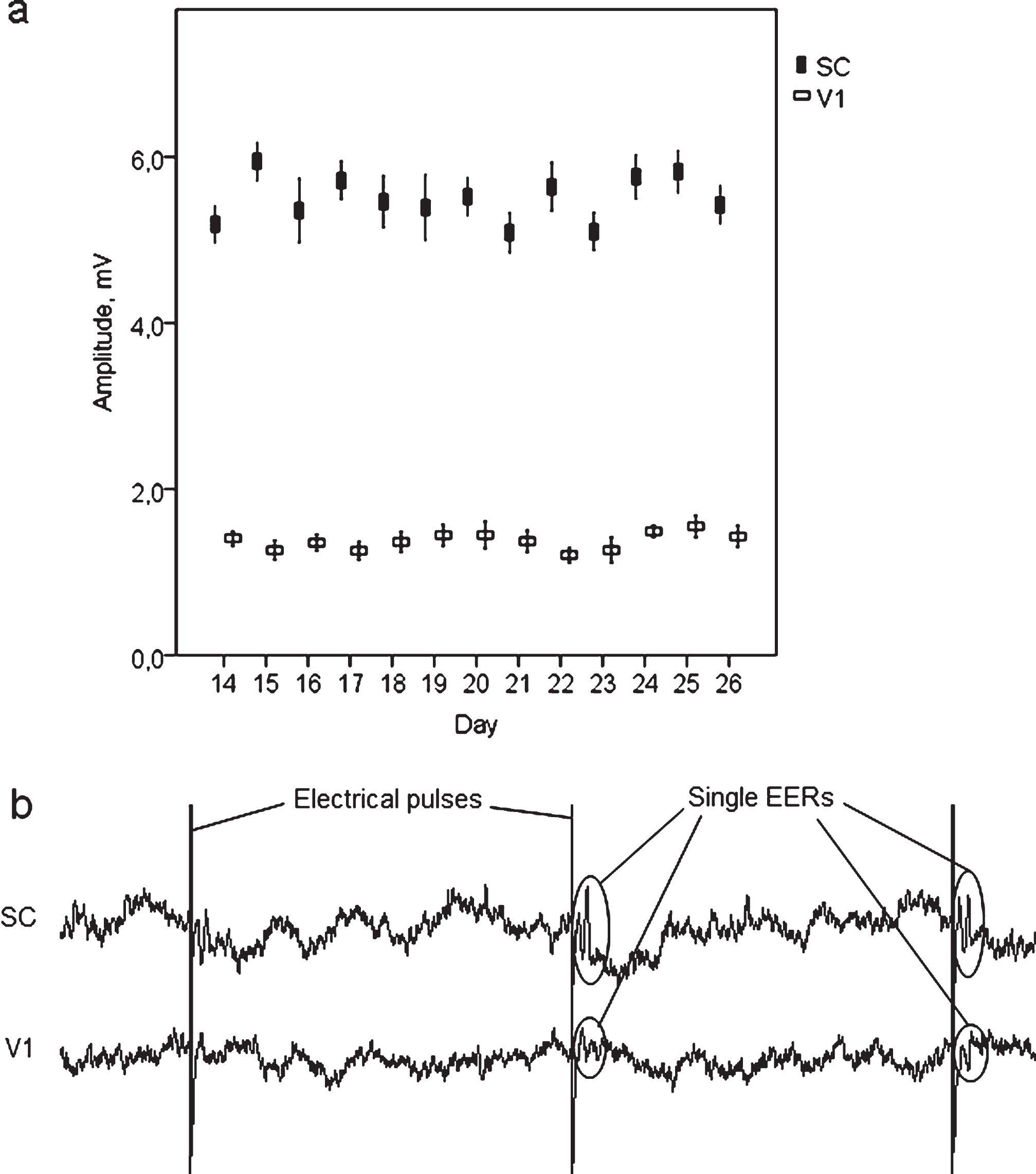

Head stages were stable and stayed intact for at least 3 months after the surgery. Analysis of VEP peak-to-peak amplitudes measured on 14– 26 days after the electrodes implantation revealed relative steadiness of the values, with no trends of reduced amplitude during the following experimental days (Fig. 2(a)). This confirmed the stability of the electrodes and implantation and demonstrated our set-up to be stable and reliable for long-term chronic studies.

When the current was applied via the corneal electrodes, the rats’ behavior showed increased alertness, sniffing and grooming. Stimulation induced a short initial involuntary tremor of the cheek ipsilateral to the side of stimulation and eye blinking, which is interpreted as a benign muscle twitching elicited by the current pulses. Rats did not show any signs of stress or pain reactions like freezing, hunchback postures, piloerection or thigmotaxis.

Current pulses applied transcorneally with parameters similar to those used for restorative treatment (Morimoto et al., 2005, 2007; Sergeeva et al., 2012; Henrich-Noack et al., 2013), produced tolerable artefacts in the recordings, allowing assessment of brain activity during stimulation (Fig. 2(b)).

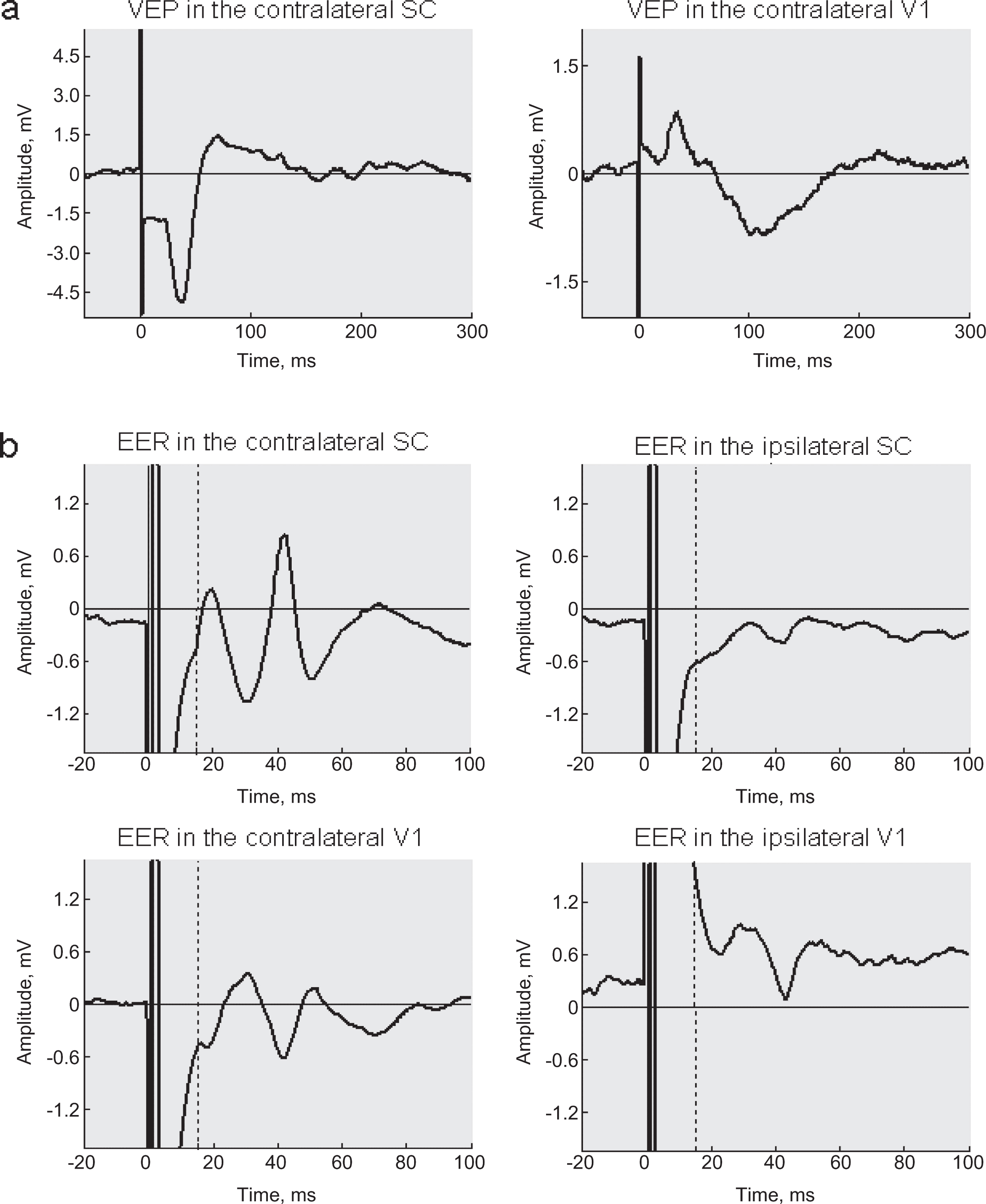

Figure 3(a) shows a typical VEP contalateral to the stimulated eye and Fig. 3(b) a typical EER. For a given stimulation parameter peaks of EER were available for analysis starting at about 15 ms after the electrical pulse was delivered. The presence of a multi-peak complex similar to visual evoked potentials is in line with the assumption that tACS induces physiological neuronal signalling and that we do not measure only passive current flow through the brain. This conclusion is supported by the fact that we registered amplitude differences between EERs ipsilateral versus contralateral to the stimulated eye. The inversion of the response in the visual cortices as compared to those in the superior colliculus may suggest current flow and stimulation of the tectum.

4Discussion

We successfully established a new technique for transcorneal electrical current stimulation and flicker light stimulation in freely moving rats as well as a chronic setup to record field potentials from visual cortex and subcortical structures (superior colliculus).

A substantial advantage of this new animal model is that we can now stimulate non-anaesthetized rats, which was not described in any of the previous studies (Sergeeva et al., 2012; Henrich-Noack et al., 2013; Morimoto et al., 2005, 2007). Our preclinical model is a critical step for further experimentation because, as Silvanto (2008) already noted, behavioural effects of non-invasive brain stimulation (in the Silvanto publication: transcranial magnetic stimulation; TMS) are determined by the initial neuronal activation state. Neuling and co-authors (2013) showed with EEG recordings that sustained effects of transcranial ACS depend on the brain state at the time of stimulation. Moreover, it is well-known that narcosis strongly influences brain oscillations and thus interferes with stimulation effects which, in turn, critically depend on inducing or modifying such oscillations. Therefore, it is especially important to consider the initial brain state when evaluating stimulation-induced changes in brain activity. This argument has been corroborated by the recent demonstration that tACS induced EEG “after-effects” can only be achieved when stimulating during a “shallow” (late) narcosis stage but not in a “deep” (early) slow-wave sleep stage (Sergeeva et al., 2012).

Another advantage of our new animal model is that rats are not restrained, i.e. they can move around freely (Luft et al., 2001). This opens the possibility of simultaneously stimulating and recording in freely moving rats, and it permits behavioural testing in parallel to investigating electrophysiological effects of stimulation. In fact, animal models such as the one we have developed are a prerequisite for discovering causal relationships between brain oscillations altered by electrical stimulation and behavioural functions (Herrmann et al., 2013; Neuling et al., 2013).

There was one concern during the development of our new technique of tACS: whether the electrodes are stable over time. But implantation proved to be appropriate for long-term chronic experiments as demonstrated by VEP which was stable for several weeks (Fig. 2(a)).

We were also able to register EERs in different visual structures which suggests that electrical pulses may induce visual processing. Evaluation of amplitudes and latencies of components – particularly when comparing EER and VEP – can help to identify the target sites of the treatment and clarify optimal parameter settings for stimulation to achieve maximal responses in the visual system (Potts & Inoue, 1968, 1969; Shimazu et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2006).

We found that the stability of head stages depends directly on the animal’s adaptation to the experimental setup: if rats are handled properly for adaptation to cables and spectacles mounted on the head, they will not try to scratch them and damage their integrity; one week of daily handling was found to be sufficient to habituate the rats.

Another concern addressed by our study was whether unanaesthetized, freely moving animals tolerate tACS and electrodes. But we found that stimulation – with the parameters applied – did not induce any adverse reaction. This is in line with our studies in humans where also no pain or discomfort is reported by the volunteers or patients. Furthermore, our rats tolerated the stimulating electrodes well as we found no indication of them scratching at the closed eye lid. Though in 8 out of 48 eyes the inflammation lasted quite long – which was probably caused by the implanted wire – we believe that this may be due to suboptimal surgery rather than due to intrinsic intolerance to electrodes. This can be minimized with increasing surgical experience.

We conclude that our new preclinical technique for brain stimulation and recording in freely moving laboratory animals is suited to study non-invasive brain stimulation effects on brain physiology. It is a crucial step forward as it avoids narcosis-induced alterations in neuronal responses. It opens up new possibilities for animal studies in the field of experimental neuromodulation with the goal to achieve restoration of vision.

Grants

Supported by a grant from the Federal German Education and Research Ministry grant ERA-net Neuron (BMBF 01EW1210). Dr. E. Sergeeva was supported by fellowship of the Otto-von-Guericke University of Magdeburg, and Dr. A. Gorkin was supported by funding from the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service).

References

1 | Antal A, Kincses TZ, Nitsche MA, Bartfai O, Paulus W(2004) Excitability changes induced in the human primary visual cortex by transcranial direct current stimulation: Direct electrophysiological evidenceInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci45: 2702707 |

2 | Antal A, Paulus W, Nitsche MA(2011) Electrical stimulation and visual network plasticityRestor Neurol Neurosci29: 6365374 |

3 | Antal A, Paulus WTranscranial alternating current stimulation (tACS)(2013) Front Hum Neurosci7: 317 |

4 | Bechtereva NP, Shandurina AN, Khilko VA, Lyskov EB, Matveev YK, Panin AV, Nikolsky AV(1985) Clinical and physiological basis for a new method underlying rehabilitation of the damaged visual nerve function by direct electric stimulationInt J Psychophysiol2: 4257272 |

5 | Bola M, Gall C, Moewes C, Fedorov A, Hinrichs H, Sabel BA(2014) Functional connectivity network breakdown and restoration in blindnessNeurology83: 6542551 |

6 | Brittain JS, Probert-Smith P, Aziz TZ, Brown P(2013) Tremor suppression by rhythmic transcranial current stimulationCurr Biol23: 5436440 |

7 | Burns SP, Xing D, Shapley RM(2011) Is gamma-band activity in the local field potential of V cortex a “clock” or filtered noise?J Neurosci31: 2696589664 |

8 | Cancelli A, Cottone C, Zito G, Di Giorgio M, Pasqualetti P, Tecchio F(2015) Cortical inhibition and excitation by bilateral transcranial alternating current stimulationRestor Neurol Neurosci33: 2105114 |

9 | Chang WH, Kim YH, Yoo WK, Goo KH, Park CH, Kim ST, Pascual-Leone A(2012) rTMS with motor training modulates cortico-basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits in stroke patientsRestor Neurol Neurosci30: 3179189 |

10 | Chen SJ, Mahadevappa M, Roizenblatt R, Weiland J, Humayun M(2006) Neural responses elicited by electrical stimulation of the retinaTrans Am Ophthalmol Soc104: 252259 |

11 | Chibisova AN, Fedorov AB, Fedorov NA(2001) Neurophysiological characteristics of compensation-recovery processes in the brain during rehabilitation of the neurosensory impairment of the visual and acoustic systemsFiziol Cheloveka27: 31421 |

12 | Dawson WW, Trick GL, Litzkow CA(1979) Improved electrode for electroretinographyInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci18: 9988991 |

13 | Fedorov A, Jobke S, Bersnev V, Chibisova A, Chibisova Y, Gall C, Sabel BA(2011) Restoration of vision after optic nerve lesions with noninvasive transorbital alternating current stimulation: A clinical observational studyBrain Stimul4: 4189201 |

14 | Foik AT, Kublik E, Sergeeva EG, Tatlisumak T, Sabel BA, Rossini PM, Waleszczyk WJ(2015) Retinal origin of electrically evoked potentials in response to transcorneal alternating current stimulation in the rat, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, epub ahead of printIOVS-14-15617 |

15 | Gall C, Antal A, Sabel BA(2013) Non-invasive electrical brain stimulation induces vision restoration in patients with visual pathway damageGraefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol251: 310411043 |

16 | Gall C, Sgorzaly S, Schmidt S, Brandt S, Fedorov A, Sabel BA(2011) Noninvasive transorbital alternating current stimulation improves subjective visual functioning and vision-related quality of life in optic neuropathyBrain Stimul4: 4175188 |

17 | Gonzalez-Burgos G, Lewis DA(2008) GABA neurons and the mechanisms of network oscillations: Implications for understanding cortical dysfunction in schizophreniaSchizophr Bull34: 5944961 |

18 | Guarino I, Loizzo S, Lopez L, Fadda A, Loizzo A(2004) A chronic implant to record electroretinogram, visual evoked potentials and oscillatory potentials in awake, freely moving rats for pharmacological studiesNeural Plast11: 3–4241250 |

19 | Henrich-Noack P, Lazik S, Sergeeva E, Wagner S, Voigt N, Prilloff S, Fedorov A, Sabel BA(2013) Transcorneal alternating current stimulation after severe axon damage in rats results in “long-term silent survivor” neuronsBrain Res Bull95: 714 |

20 | Herrmann CS, Rach S, Neuling T, Strüber D(2013) Transcranial alternating current stimulation: A review of the underlying mechanisms and modulation of cognitive processesFront Hum Neurosci7: 279 |

21 | Kanai R, Paulus W, Walsh V(2010) Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) modulates cortical excitability as assessed by TMS-induced phosphene thresholdsClin Neurophysiol121: 915511554 |

22 | Kirson ED, Dbalý V, Tovarys F, Vymazal J, Soustiel JF, Itzhaki A, Mordechovich D, Steinberg-Shapira S, Gurvich Z, Schneiderman R, Wasserman Y, Salzberg M, Ryffel B, Goldsher D, Dekel E, Palti Y(2007) Alternating electric fields arrest cell proliferation in animal tumor models and human brain tumorsProc Natl Acad Sci USA104: 241015210157 |

23 | Laczó B, Antal A, Rothkegel H, Paulus W(2014) Increasing human leg motor cortex excitability by transcranial high frequency random noise stimulationRestor Neurol Neurosci32: 3403410 |

24 | Luft AR, Kaelin-Lang A, Hauser TK, Cohen LG, Thakor NV, Hanley DF(2001) Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the ratExp Brain Res140: 1112121 |

25 | Miyake K, Yoshida M, Inoue Y, Hata Y(2007) Neuroprotective effect of transcorneal electrical stimulation on the acute phase of optic nerve injuryInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci48: 523562361 |

26 | Morimoto T, Miyoshi T, Matsuda S, Tano Y, Fujikado T, Fukuda Y(2005) Transcorneal electrical stimulation rescues axotomized retinal ganglion cells by activating endogenous retinal IGF-1 systemInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci46: 21472155 |

27 | Morimoto T, Tomomitsu TF, Choi J, Miyoshi HK, Fukuda Y, Tano Y(2007) Transcorneal electrical stimulation promotes the survival of photoreceptors and preserves retinal function in royal college of surgeons ratsInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci48: 47254732 |

28 | Neuling T, Rach S, Herrmann CS(2013) Orchestrating neuronal networks: Sustained after-effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation depend upon brain statesFront Hum Neurosci7: 161 |

29 | Ni Y, Gan D, Xu H, Xu G, Da C(2009) Neuroprotective effect of transcorneal electrical stimulation on light-induced photoreceptor degenerationExp Neurol219: 439452 |

30 | Paulus W(2011) Transcranial electrical stimulation (tES - tDCS; tRNS, tACS) methodsNeuropsychol Rehabil21: 5602617 |

31 | Paxinos G, Watson C(1998) The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic CoordinatesAcademic PressNew York |

32 | Polanía R, Paulus W, Nitsche MA(2012) Modulating cortico-striatal and thalamo-cortical functional connectivity with transcranial direct current stimulationHum Brain Mapp33: 1024992508 |

33 | Potts AM, Inoue J, Buffum D(1968) The electrically evoked response of the visual system (EER)Invest Ophthalmol7: 3269278 |

34 | Potts AM, Inoue J(1969) The electrically evoked response (EER) of the visual system. II. Effect of adaptation and retinitis pigmentosaInvest Ophthalmol8: 6605612 |

35 | Sabel BA, Fedorov AB, Naue N, Borrmann A, Herrmann C, Gall C(2011) Noninvasive alternating current stimulation improves vision in optic neuropathyRestor Neurol Neurosci29: 6493505 |

36 | Sergeeva EG, Fedorov AB, Henrich-Noack P, Sabel BA(2012) Transcorneal alternating current stimulation induces EEG “aftereffects” only in rats with an intact visual system but not after severe optic nerve damageJ Neurophysiol108: 924942500 |

37 | Sergeeva EG, Henrich-Noack P, Bola M, Sabel BA(2014) Brain-state-dependent non-invasive brain stimulation and functional priming: A hypothesisFront Hum Neurosci8: 899 |

38 | Shandurina AN, Panin AV, Sologubova EK, Kolotov AV, Goncharenko OI, Nikol’skii AV, Logunov VY(1996) Results of the use of therapeutic periorbital electrostimulation in neurological patients with partial atrophy of the optic nervesNeurosci Behav Physiol26: 2137142 |

39 | Shimazu K, Miyake Y, Fukatsu Y, Watanabe S(1999) Neuronal origin of the transcorneal electrically evoked response in area 17 (primary visual cortex) of catsOphthalmic Res31: 3220228 |

40 | Silvanto J, Muggleton N, Walsh V(2008) State-dependency in brain stimulation studies of perception and cognitionTrends Cogn Sci12: 12447454 |

41 | Szabó-Salfay O, Pálhalmi J, Szatmári E, Barabás P, Szilágyi N, Juhász G(2001) The electroretinogram and visual evoked potential of freely moving ratsBrain Res Bull56: 1714 |

42 | Turi Z, Ambrus GG, Janacsek K, Emmert K, Hahn L, Paulus W, Antal A(2013) Both the cutaneous sensation and phosphene perception are modulated in a frequency-specific manner during transcranial alternating current stimulationRestor Neurol Neurosci31: 3275285 |

43 | Yang EJ, Baek SR, Shin J, Lim JY, Jang HJ, Kim YK, Paik NJ(2012) Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on post-stroke dysphagiaRestor Neurol Neurosci30: 4303311 |

44 | Zaehle T, Rach S, Herrmann CS(2010) Transcranial alternating current stimulation enhances individual alpha activity in human EEGPLoS One5: 11e13766 |

Figures and Tables

Fig.1

Experimental setup for recording of local field potentials and transcorneal current stimulation in freely moving rats. (a) Implantation scheme: the rats have electrodes implanted into the primary visual cortex (V1) and superior colliculus (SC); the reference electrode for recording was implanted into the nose bone; fine wires for current stimulation were inserted under the upper eye lids and passed through under the skin to the skull surface; the reference electrode for stimulation was implanted into occipital bone. (b) Spectacles construct. (c) a rat with connected preamplifier, stimulation conductor and embedded spectacles.

Fig.2

(a) Steadiness of peak-to-peak amplitude of visual evoked potentials recorded on 14– 26 days after the surgery demonstrates stability of the electrodes. (b) raw LFP data with pulse artefacts and single electrically evoked responses recorded from V1 and SC.

Fig.3

(a) Typical VEP from contralateral superior colliculus and visual cortex of rat averaged over 100 stimulus repetitions. (b) Typical EER from contralateral and ipsilateral superior colliculus and visual cortex of a rat, averaged over 100 stimulus repetitions. Stimuli: square biphasic 2 msec pulses of 300μA intensity, 1 per sec.