Effectiveness of spiritual care training for rehabilitation professionals: An exploratory controlled trial

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Spirituality may play an important role in neurorehabilitation, however research findings indicate that rehabilitation professionals do not feel well equipped to deliver spiritual care.

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate a spiritual care training program for rehabilitation professionals.

METHODS:

An exploratory controlled trial was conducted. Participants enrolled in a two-module spiritual care training program. Spiritual care competency was measured with the Spiritual Care Competency Scale. Confidence and comfort levels were measured using the Spiritual Care Competency Scale domains. The Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale assessed participant attitudes and knowledge. Measures were administered three times: pre-program, post-program and six weeks follow-up.

RESULTS:

The training (n = 41) and control (n = 32) groups comprised rehabilitation professionals working in spinal cord or traumatic brain injury units. No between-group differences were observed on the study variables at the pre-program time point. Multilevel models found that levels of spiritual care competency, confidence, comfort, and ratings on existential spirituality increased significantly for the training group (versus control) post-program (p < 0.05) and these significant differences were maintained at follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS:

A brief spiritual care training program can be effective in increasing levels of self-reported competency, confidence and comfort in delivery of spiritual care for rehabilitation professionals.

1Introduction

Traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury are life changing injuries which can impact upon a person’s physical, psychological, emotional or spiritual well-being. While much research has focused upon the negative impacts of neurotrauma, a growing body of literature is emphasising the strengths and resilience of injured people and their family members (White, Driver, & Warren, 2008). One factor increasingly thought to contribute to resilience is spirituality (Fricchione & Nejad, 2012; Smith, Ortiz, Wiggins, Bernard, & Dalen, 2012; Walsh, 2003).

Spirituality has been described as ‘the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose, and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature and to the significant or sacred’(Puchalski et al., 2009). Spirituality and religion have generally been described as distinct but overlapping constructs, with religion considered to encapsulate “an institutionalised (i.e. systematic) pattern of values, beliefs, symbols, behaviours, and experiences that are oriented toward spiritual concerns, shared by a community, and transmitted over time in traditions” (Canda & Furman, 2009, p. 59). This positions spirituality as the broader of the two constructs, encompassing a range of different sources of meaning and connection, including but not limited to religious faith (Davis et al., 2015; Jones, Dorsett, Simpson, & Briggs, 2018).

The role of spirituality in promoting whole-of-person care is becoming evident within healthcare (Cobb, Puchalski, & Rumbold, 2012; Koenig, 2012). The results of two recent scoping reviews demonstrate that spirituality has been positively associated with quality of life, life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and resilience after both spinal cord injury (SCI) (Jones, Simpson, Briggs, & Dorsett, 2016) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Jones, Pryor, Care-Unger, & Simpson, 2018). Johnstone, Glass and Oliver (2007) have argued that addressing the spiritual needs of people affected by chronic disabilities, such as TBI and SCI, may be equally as important as addressing those needs in people with end-of-life conditions or illnesses. They suggested spirituality (or religion) may help such people “cope with their disability, give new meaning to their lives based on their newly acquired disabilities, and help them to establish new life goals” (p.1155).

Spiritual care has been described as “person centred care which seeks to help people (re)discover hope, resilience and inner strength in times of illness, injury, transition and loss” (NHS Education for Scotland, 2013). Despite the increasing awareness of the importance of spirituality after neurotrauma, existing research suggests spirituality is not well incorporated in neurorehabilitation practice (Jones, Dorsett, Briggs, & Simpson, 2018; Jones, Pryor, Care-Unger, & Simpson, 2020). A recent study revealed that while rehabilitation health professionals acknowledged the importance of spirituality for patients, several barriers to addressing patients’ spiritual needs were identified; these included a need for more training (80%), not enough time (74%) and personal discomfort (61%) (Jones et al., 2020). These findings are consistent with results from other healthcare areas and disciplines, including palliative care doctors (Best, Butow, & Olver, 2016), acute care nurses (Gallison, Xu, Jurgens, & Boyle, 2012), social workers (Oxhandler, Parrish, Torres, & Achenbaum, 2015) and physiotherapists (Oakley, Katz, Sauer, Dent, & Millar, 2010). These studies have also demonstrated that overcoming these barriers in the delivery of spiritual care is important for healthcare professionals from a range of disciplines.

A number of spiritual care training programs and resources have been developed and trialled within healthcare settings to assist healthcare professionals to better address the spiritual needs of clients (NHS Education for Scotland, 2009; Paal, Helo and Frick, 2015). In a systematic review of the literature, Paal et al. (2015) found that spiritual care training assisted participants to increase their awareness of personal spirituality and spiritual needs, clarify the role of spirituality and importance of spiritual care, and prepare trainees for spiritual encounters. However, Paal and colleagues also noted that few studies were well evaluated, and seldom involved a control group. Much of the training was conducted within the field of palliative care.

Professional development training in the contemporary health context has to compete with a broad range of other demands that health staff juggle in carrying out their daily duties. Within this context, multimodal presentation formats (online, face-to-face) employing brief training interventions are highly desirable. A few spiritual care programs have indicated that brief training in spiritual care can be effective in improving confidence and comfort levels in healthcare professionals. Cerra and Fitzpatrick (2008) observed that changes in healthcare professionals’ perceptions of spirituality were achieved after a two hour didactic lecture, while Meredith and colleagues (2012) reported changes in spiritual care and confidence after healthcare professionals attended a single workshop. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a brief spiritual care training program to expand attitudes and knowledge regarding spirituality and spiritual care, and to increase rehabilitation professionals’ levels of competency, confidence and comfort in the delivery of spiritual care. An underlying assumption of the program was that spiritual care is relevant to all healthcare disciplines, and therefore training should be provided to all members of the multidisciplinary team.

2Methods

2.1Participants

This study was an exploratory controlled trial. Ethical approval was obtained from Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (LNR AU/1/5688313). Recruitment took place between February and December 2019. The trial was conducted across four specialised neurorehabilitation units in Sydney Australia (2 TBI, 2 SCI). To limit the possibility of contamination, two units (1 TBI, 1 SCI) were targeted for the training, with staff from the other two units acting as controls. Invitations to participate were distributed via email, or through direct contact with study investigators, to all members of the respective multidisciplinary teams. Written consent was obtained from all participants, who participated as volunteers.

2.2Intervention

The Spiritual Care Training Program consisted of two modules (see Table 1). Module 1 is a one flehour computer-based self-study unit which includes written information and video footage. Participants are introduced to the concept of spirituality and provided with examples of how people with a TBI or SCI, and their family members, have drawn upon different sources of spirituality in their adjustment. All participants completed Module 1 before Module 2.

Table 1

Program outline

| Module | Session Aims | Key Content | Format |

| 1 | To introduce the concept of spirituality, highlight its important role in rehabilitation, and present a range of different sources of spiritual strength that clients might draw upon | Spirituality and healthcare | Self-study online |

| The importance of spirituality after traumatic injury | Written content Videoed interviews of former clients | ||

| What is spirituality? | |||

| Sources of spiritual strength | |||

| 2 | To build skills in spiritual care practice. | Understanding spirituality | Workshop face-to-face |

| Introduction to spiritual care | Didactic content | ||

| Introduction to spiritual care tools | Videoed interviews | ||

| Role plays | Role plays | ||

| Looking after ourselves | Individual exercises |

Module 2 is a 1.5 hour face-to-face workshop. It includes didactic input, videoed interviews with former patients, the introduction of spiritual care tools, and the opportunity to practise skills via role plays. This content draws upon existing literature and approaches to spiritual care training (Hodge, 2013; Puchalski & Romer, 2000). Program materials emphasise that clients may draw upon a range of sources of spiritual strength, including but not limited to religious faith (Davis et al., 2015). In the role plays, participants break into pairs and are provided with case scenarios which depict conversations which may arise with patients. They have opportunity to practise taking the role of health professional or patient. Role play practice incorporates exploration of the patient’s source of spiritual strength, the meaning this source of spiritual strength currently holds for them, connections and relationships that are important to them, and how the patient would like their health professional to assist them to access their sources of spiritual strength. Participants are provided with the opportunity to reflect upon their own sources of spiritual strength, and resources to use should they wish to refer a patient for further support.

2.3Measures

Spiritual care competency was the primary outcome of interest. The Spiritual Care Competency Scale (SCCS) (van Leeuwen, Tiesinga, Middel, Post, & Jochemsen, 2009) is a valid and reliable 27 item measure which rates participant perceptions of competency in providing spiritual care. The 27 items are scored on a five-point scale from “completely disagree” to “completely agree” with total possible scores ranging from 27 to 135. The scale consists of six domains which measure: 1) assessment and implementation of spiritual care; 2) professionalisation and improving the quality of spiritual care; 3) personal support and patient counselling; 4) referral to professionals; 5) attitude towards patients’ spirituality; and 6) communication. Scores are measured on a five-point scale from 1 “completely disagree” to 5 “fully agree”. Cronbach’s alpha for the six domains ranged from 0.56 to 0.82. The scale has good homogeneity, average inter-item correlations, and good test-retest reliability (van Leeuwen et al., 2009). It was originally designed for nursing staff, so minor adjustments were made to the wording to ensure its suitability for a wider range of professions.

Secondary outcomes of interest comprised participant levels of confidence and comfort, and attitudes and knowledge regarding spirituality and spiritual care. Participants were invited to rate their confidence and comfort levels from 0 to 10 based on the six Spiritual Care Competency Scale domains (van Leeuwen et al., 2009) listed above, with higher scores indicating higher levels of confidence or comfort. Participants’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care were measured using the Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS) (McSherry, Draper, & Kendrick, 2002). The 17-item measure of spirituality and spiritual care uses a five-point scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. A four factor model of the SSCRS (Ross et al., 2014) was used: Existential Spirituality (view that spirituality is concerned with people’s sense of meaning, purpose, value, peace and creativity; 5 items); Religiosity (view that spirituality is only about religious beliefs; 3 items); Spiritual Care (view of spiritual care in its broadest sense including religious and existential elements, for example facilitating religious rituals and showing kindness; 5 items); and Personal Care (taking account of people’s beliefs, values and dignity; 3 items), with one item contributing to the score of two of the subscales. Scores (total and subscale scores) are calculated by averaging the mean for the relevant items (all scores therefore range from 1–5). A broader view of spirituality and spiritual care is indicated by higher scores (Ross et al., 2014). The SSCRS has a modest level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.64) (McSherry, 1997) and has been used in a range of health settings, including rehabilitation (Austin, Macleod, Siddall, McSherry, & Egan, 2016).

2.4Procedures

After signing the consent form, participants in the intervention group were provided with access to the online component (Module 1). They were then provided with details to attend the program workshop (Module 2), which was scheduled approximately two weeks later. The scales were administered at three timepoints (pre-program, post-program, follow-up). The first timepoint (pre-program) occurred two weeks prior to Module 1, the second timepoint (post-program) immediately after Module 2, and the third timepoint (follow-up) four to six weeks after completing the training. The same measures were administered to the control group participants at the same time intervals. Data about demographic, discipline and work experience variables for both groups were collected at the pre-program timepoint. The question “Do you consider yourself a spiritual person? Please rank on a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 is ‘not spiritual at all’ and 10 is ‘very spiritual” was included to determine each participant’s perceived level of spirituality.

2.5Data analysis

Descriptive data were generated, and between-groups analysis at baseline on demographic variables was conducted. Multilevel models with piecewise slopes using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) were used to analyse each outcome measure over time. Each participant was considered level-2 in the models and the individual visits were level-1. A level-2 predictor representing whether the person was in the intervention or control group was added to each model. Two piecewise variables that indicate time from 1) pre intervention to post intervention and from 2) post intervention to follow-up were added to the model as level-1 variables. Interaction terms between group and each of the piecewise variables were added to assess differences in the outcomes between groups over time. Random intercepts were included in each model, and random slopes based on the piecewise variables were considered. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data analysis was generated using SAS Enterprise Guide software, Version 7.15 of the SAS System for Windows.

A satisfaction questionnaire measuring participant ratings of program content and usefulness was administered at the post-program timepoint. An open-ended question inviting participants to comment on the ‘most significant change’ they had observed since the training was added at the follow-up evaluation timepoint. A thematic analysis of this qualitative data was conducted according to guidelines provided by Braun and Clarke (2006) including familiarisation with the data; generating initial codes; searching for themes; reviewing themes; defining and naming themes; and producing a report.

3Results

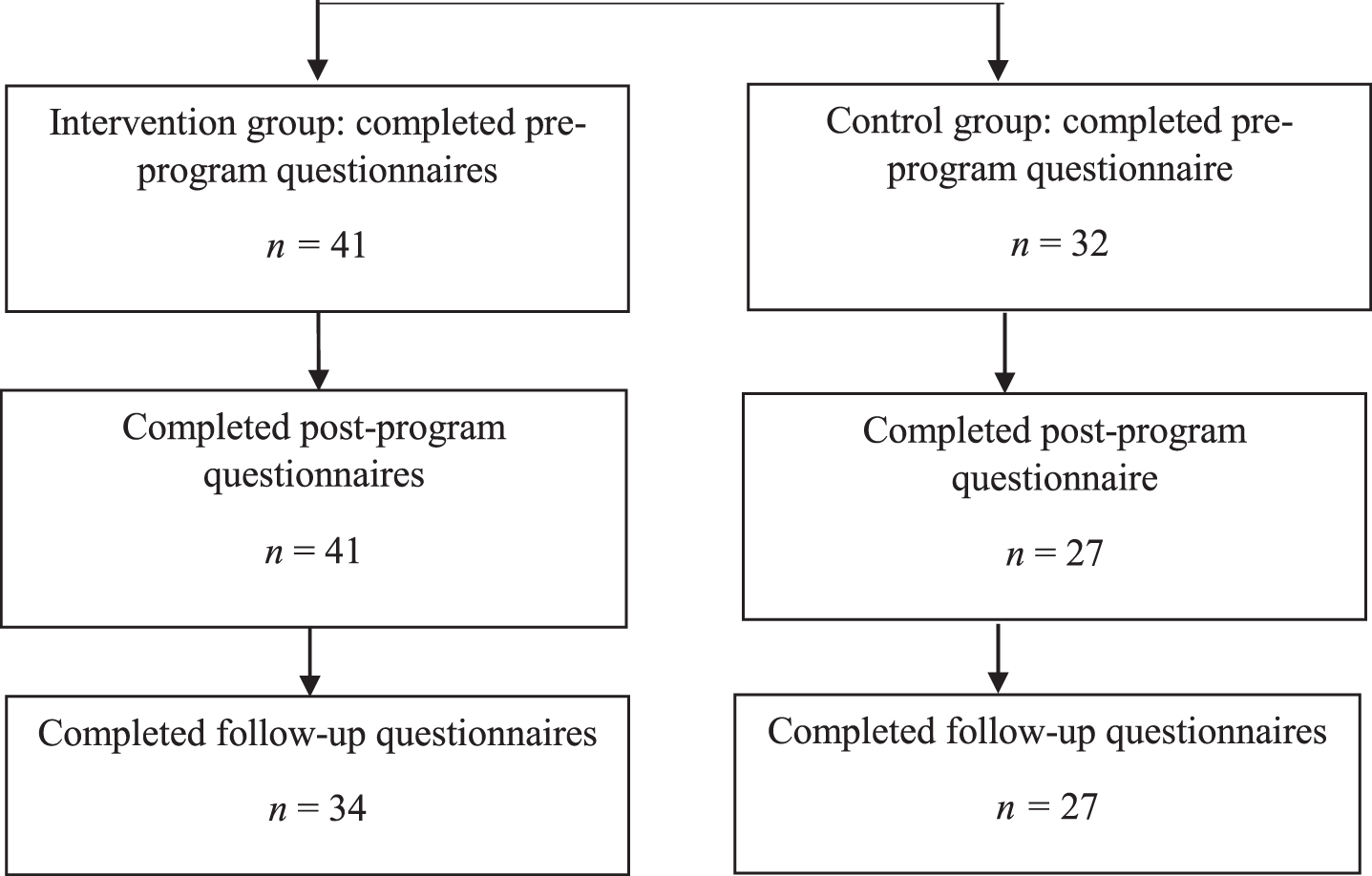

In relation to the intervention group, 47 rehabilitation professionals expressed initial interest in participating in the training and provided consent. Six of the 47 withdrew from the study prior to the training due to sickness, work commitments or other unexpected events, resulting in 41 rehabilitation professionals who completed the training. A further 32 rehabilitation professionals were recruited to the control groups. See Fig. 1 for details of the numbers of questionnaires completed at each time point by the two groups.

Fig. 1

Flow diagram of the study.

Demographic details for all the participants are reported in Table 2. Between group analyses (t-test, chi square) revealed no significant differences between the intervention and control groups on age, gender, religious affiliation, patient group (TBI, SCI), years of experience, or whether they considered themselves to be a spiritual person.

Table 2

Demographic and professional details (N = 73)

| Demographic items | Category | Intervention Group | Control Group |

| N = 41 | N = 32 | ||

| Gender (n,%) | Female | 33 (80.5) | 25 (78.1) |

| Male | 8 (19.5) | 7 (21.9) | |

| Age (n,%) | 21–29 | 8 (19.5) | 9 (28.1) |

| 30–39 | 10 (24.4) | 12 (37.5) | |

| 40–49 | 13 (31.7) | 9 (28.1) | |

| 50 and over | 10 (24.4) | 2 (6.3) | |

| Type of patient group (n,%) | Spinal cord injury | 27 (65.9) | 20 (62.5) |

| Traumatic brain injury | 14 (34.1) | 12 (37.5) | |

| Setting (n, %) | Inpatient | 33 (80.5) | 32 (100.0) |

| Community | 8 (19.5) | ||

| Area of expertise (discipline) (n,%) | Nursing | 12 (29.3) | 5 (15.6) |

| Social work, psychology, case management | 12 (29.3) | 7 (21.9) | |

| Medical/other allied health | 17 (41.5) | 20 (62.5) | |

| Work experience (years) (M,SD) | 13.1 (9.85) | 11.13 (9.77) | |

| Qualification (n,%) | No bachelor degree | 3 (7.3) | 1 (3.1) |

| Bachelor degree | 24 (58.5) | 20 (62.5) | |

| Master degree and above | 14 (34.1) | 11 (34.4) | |

| Ethnicity (n,%) | Australian/New Zealander | 27 (65.9) | 19 (59.4) |

| Asian | 4 (9.8) | 6 (18.8) | |

| European | 5 (12.2) | 7 (21.9) | |

| Other* | 5 (12.2) | – | |

| Born in Australia (n,%) | Yes | 26 (63.4) | 18 (56.3) |

| Religious affiliation (n,%) | None | 11 (26.8) | 10 (31.3) |

| Christian | 26 (63.4) | 17 (53.1) | |

| Hindu | 1 (2.4) | 3 (9.4) | |

| Muslim | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Jewish | 2 (4.9) | – | |

| Previous spiritual care training (n,%) | Yes | 3 (7.3) | 2 (6.3) |

| Spiritual person 0–10 (M, SD) | 6.2 (2.5) | 5.4 (2.7) |

Other included: South African, Pacific Islander, North African/Middle Eastern, Central American, and preferred not to respond.

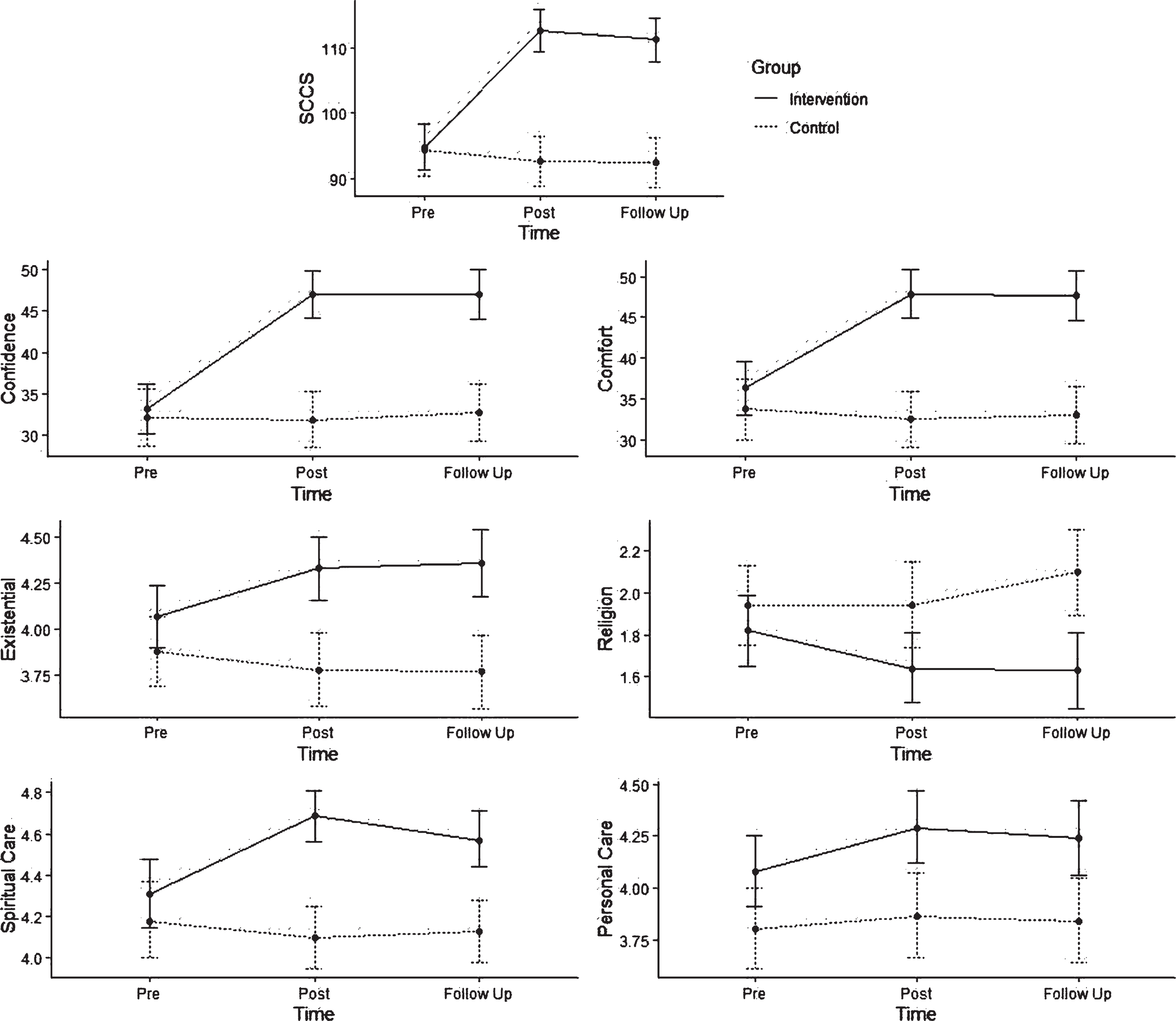

For spiritual care competency, confidence, comfort, and the “existential factor” of the SSCRS, pre intervention scores were not significantly different between the two groups (p > 0.05), however, increased significantly in the intervention group at post intervention (p < 0.05). The observed differences between the groups at post intervention were maintained at follow-up. A similar trajectory was observed for the SSCRS “spiritual care” factor, with the exception of the score decreasing in the intervention group between post intervention and follow-up (p < 0.05), however, remaining significantly higher than the control group (p < 0.001). For the SSCRS factor “religion”, control group scores were significantly higher at post intervention (p < 0.05) and follow-up (p < 0.001). For the SSCRS factor “personal care”, intervention group scores were higher at pre intervention (p < 0.05), with differences increasing at post intervention (p < 0.05) and maintained at follow-up (p < 0.05) (see Table 3, Fig. 2).

Table 3

Comparison of outcomes between intervention and control groups over time

| Pre-program | Post-program | Follow-up | ||||||||

| Outcome | Group | Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper |

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

| SCCS | Intervention | 94.88 | 91.38 | 98.38 | 112.56c | 109.35 | 115.77 | 111.15c | 107.78 | 114.52 |

| Control | 94.50 | 90.54 | 98.46 | 92.71 | 88.9 | 96.53 | 92.57 | 88.75 | 96.39 | |

| Confidence | Intervention | 33.22 | 30.18 | 36.25 | 46.95c | 44.08 | 49.82 | 46.97c | 44.02 | 49.93 |

| Control | 32.22 | 28.78 | 35.65 | 31.90 | 28.52 | 35.28 | 32.76 | 29.38 | 36.13 | |

| Comfort | Intervention | 36.32 | 33.03 | 39.61 | 47.83c | 44.83 | 50.83 | 47.72c | 44.67 | 50.77 |

| Control | 33.72 | 30.00 | 37.44 | 32.46 | 28.96 | 35.96 | 32.96 | 29.46 | 36.46 | |

| Exist | Intervention | 4.07 | 3.90 | 4.24 | 4.33c | 4.16 | 4.50 | 4.36c | 4.18 | 4.54 |

| Control | 3.88 | 3.69 | 4.07 | 3.78 | 3.58 | 3.98 | 3.77 | 3.57 | 3.97 | |

| Religion | Intervention | 1.82 | 1.65 | 1.99 | 1.64a | 1.48 | 1.81 | 1.63c | 1.45 | 1.81 |

| Control | 1.94 | 1.75 | 2.13 | 1.94 | 1.74 | 2.15 | 2.10 | 1.89 | 2.30 | |

| Spiritual care | Intervention | 4.31 | 4.15 | 4.48 | 4.69c | 4.56 | 4.81 | 4.57c | 4.44 | 4.71 |

| Control | 4.18 | 4.00 | 4.37 | 4.10 | 3.95 | 4.25 | 4.13 | 3.98 | 4.28 | |

| Personal Care | Intervention | 4.08a | 3.91 | 4.25 | 4.29b | 4.12 | 4.47 | 4.24b | 4.06 | 4.42 |

| Control | 3.80 | 3.61 | 4.00 | 3.86 | 3.66 | 4.07 | 3.84 | 3.64 | 405 | |

Note. CI, Confidence Interval; SCCS, Spiritual Care Competency Scale. A multilevel model was used to model the outcomes over time and compare the intervention and control groups at each time point. aIndicates mean is significantly different compared with the control group for that outcome at the same time point with 0.01 < p < 0.05. bIndicates mean is significantly different compared with the control group for that outcome at the same time point with 0.001 < p < 0.01. cIndicates mean is significantly different compared with the control group for that outcome at the same time point with p < 0.001.

Fig. 2

Comparison of intervention and control groups’ scores on SCCS, and SSCRS factors. Estimated means and their 95% confidence intervals based on piecewise multilevel models are shown in the plots.

The post-program questionnaire invited participants to rate and provide comments about workshop content and usefulness (see Table 4). Across all aspects of the workshop, the majority of participants rated the training as ‘good’ or ‘very good’. The ‘program overall’ was rated as ‘very good’ by the majority of participants. The lowest ranked aspect of the program was ‘the usefulness of the program in increasing my comfort levels’, however, most participants considered the program to be ‘good’ or ‘very good’ in raising confidence levels and in increasing knowledge and skills. Positive feedback was received regarding the introduction of a tool, the use of role plays and videos, as well as the time provided for reflection. Some participants also mentioned that the program confirmed that they were already incorporating spiritual care into their practice.

Table 4

Workshop satisfaction ratings (N = 41)

| Aspect of program | Very Poor | Poor | Okay | Good | Very Good |

| (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Overall, I found the program today was | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (21.9) | 32 (78.0) |

| The time allocated to cover each section | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 15 (36.6) | 25 (61.0) |

| The balance between theoretical and practical content | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 14 (34.1) | 26 (63.4) |

| The usefulness of the content in relation to my workplace situation | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 11 (26.8) | 29 (70.7) |

| The program content | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 14 (34.1) | 26 (63.4) |

| The role play exercise | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.9) | 21 (51.2) | 18 (43.9) |

| The level of interaction encouraged by the facilitator | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 11 (26.8) | 30 (73.2) |

| The use of relevant language and case examples by the facilitator | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 7 (17.1) | 33 (80.5) |

| The usefulness of the program in increasing my knowledge and skills | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.3) | 10 (23.4) | 28 (68.3) |

| The usefulness of the program in increasing my confidence | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.9) | 13 (31.7) | 26 (63.4) |

| The usefulness of the program in increasing my comfort levels | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.8) | 14 (34.1) | 23 (56.1) |

Suggestions for improving the program included extending the duration of the program, providing information for referral to chaplaincy and other faith services, and advice on documentation in the medical record. When invited to comment on something they hoped to do better as a result of the program, many reported incorporating more meaningful questions into their practice and following clients up regarding their spiritual needs.

As part of the four to six-week follow-up, intervention group participants were invited to describe the most significant change they had noticed in their thinking or practice since the training (see Table 5). The 31 responses could be summarised by two key themes: increased awareness and understanding of spirituality as a broad concept, and increased confidence to provide spiritual care.

Table 5

Most significant change (N = 31)

| Increased awareness and understanding of spirituality | Increased confidence to provide spiritual care |

| •Greater awareness of the broad definition of what spirituality can look like when dealing with clients | •Making a conscious effort to implement spiritual care holistically in my practice |

| •Being more open and aware of clients’ spiritual needs | •I am more comfortable to acknowledge spiritual needs of clients in the context of their recovery from injury |

| •Identifying strategies for exploring spirituality during dietetic consult. Increased awareness of spiritual practices and its influence on food practices when consulting with patients. | •Being able to support clients with normalising their reflections on spiritual care post SCI and allowing time for them to explore this |

| •More aware about spirituality and used the SICA model | •Being cognisant and supportive of a client’s spiritual care needs. |

| •I am more aware of asking clients about their spiritual needs and what gives them strength | •Therapy is increasingly focused on choice and control of clients |

| •Being aware of what I say and do with clients and colleagues | •Actively listen to clients |

| •Increased awareness of the supports that I provide can be related to an individual spirituality and assisting my clients to consider these more actively. | •Discussing spiritual needs to a greater extent. Asking more questions about what we can do to assist. If they discuss one aspect of spirituality (e.g. religion) and continue to enquire about other aspect (e.g. outside/nature). |

| •It has helped me to be more aware of the breadth and depth of the term ‘spirituality’. To recognise in others that whilst they may not have a religious faith they still have a sense of well-being and connectedness that requires care, nurture and support and that we as health professionals can provide directly, support or facilitate. I appreciate more the concept of the ‘whole person’. | •Realising the depth and breadth of what spirituality can involve has provided me with more confidence discussing this topic |

| •Being more aware of the breadth of spirituality, and looking for opportunities to assist. | •Providing opportunity for client to talk about spirituality in an informal way (e.g. what uplifts the client) |

| •Increased awareness and confidence | •Discussing spirituality during initial assessment |

| •Has made me more aware of one spiritual needs in rehabilitation as little or as big as it may be. | •Being better able to recognise a person’s spiritual needs |

| •Greater knowledge and understanding | •Actively listening to patients about spirituality |

| •I have a better understanding of what spirituality is. | •Open discussions with work colleagues regarding concept of spirituality &supporting our clients |

| •Better understanding what spirituality is and how it can be addressed in the inpatient setting | |

| •Understanding the different aspects of spirituality and seeing how important it was to client’s that it was addressed. Using a framework to assess spiritual needs, and how to assist client’s during their rehab. | |

| •Increasing my understanding of the different ways clients use spirituality as a form of hope and resilience | |

| •Being more alert to clients expressing their spiritual needs in a variety of ways (ie language such as hope, worry) | |

| •An important reminder to focus on the source of people’s important life roles and areas of satisfaction or quality of life including spiritual beliefs. |

i) Increased awareness and understanding of spirituality as a broad concept

Participants reported that following the program they were more aware about clients having spiritual needs, alert to the expression of spiritual needs, and more aware of the support they could provide. One participant explained:

It has helped me to be more aware of the breadth and depth of the term ‘spirituality’. To recognise in others that whilst they may not have a religious faith they still have a sense of well-being and connectedness that requires care, nurture and support, and that we as health professionals can provide directly, support or facilitate. I appreciate more the concept of the ‘whole person’.

Another participant expressed that the training had increased their understanding of “the different ways clients use spirituality as a form of hope and resilience”. Another mentioned how understanding different aspects of spirituality had helped them to realise how important spirituality is to clients.

ii) Increased confidence to provide spiritual care

The second identified theme was participants feeling more confident to provide spiritual care. One participant reported that the training had helped them to support clients by “normalising their reflections on spiritual care post SCI and allowing them to explore this”. Another mentioned that they felt more comfortable acknowledging the spiritual needs of clients within the context of their recovery. Two participants reported that they were actively making a conscious effort to implement spiritual care or identify strategies for exploring spirituality in their work. One mentioned that they were “asking more questions about what we can do to assist” and exploring more than one source of spirituality with clients (for example, the natural word as well as religious beliefs).

4Discussion

This exploratory study evaluated the effectiveness of a brief spiritual care training program to expand attitudes and knowledge regarding spirituality and spiritual care, and to increase rehabilitation professionals’ perceived levels of competency, confidence and comfort in the delivery of spiritual care. To the best of our knowledge no other studies have trialled healthcare professional training in the area of spiritual care and neurorehabilitation. Significant increases in the primary outcome, spiritual care competency, were recorded for the intervention group at the post program timepoint and were not matched by the control group. These increases were maintained at follow-up. Similarly, in relation to the secondary outcomes the intervention group scored significantly higher scores on confidence and comfort, and demonstrated a greater understanding of spirituality and spiritual care at the post program timepoint than the control group. Participant satisfaction levels regarding the program content and usefulness were high. At follow-up participants in the intervention group could identify changes in both understanding and practice in their delivery of spiritual care.

Levels of spiritual care competency were significantly higher for the intervention group after attending the spiritual care training program. In-creases in spiritual care competency have been reported in other studies investigating the effects of spiritual care training. A recent study by Pearce, Pargarment, Oxhandler, Vieten and Wong (2019) with mental health providers (the majority of whom were psychologists, social workers, counsellors) found an online training program to be successful in improving spiritual care competencies. Spiritual care competencies improved at post-testing, after an eight-module online training program. Although the current program was much less time-intensive, similar results were achieved and maintained at follow-up, suggesting that even a small amount of training can bring about significant change.

Confidence and comfort levels in delivering spiritual care were also significantly higher for the intervention group at post and follow-up testing. Other spiritual care programs have indicated that brief training in spiritual care can be effective in improving confidence and comfort levels (Cerra & Fitzpatrick, 2008; Meredith et al., 2012). Perspectives on spirituality and spiritual care also changed for the intervention group, evident from participant scores on the SSCRS (McSherry et al., 2002). Compared with the control group, the factors most likely to indicate change were participant ratings on Existential Spirituality (view that spirituality is concerned with people’s sense of meaning, purpose, value, peace and creativity) and Spiritual Care (view of spiritual care in its broadest sense including religious and existential elements, for example facilitating religious rituals and showing kindness). These findings aligned well with the content of the program which encouraged participants to adopt broad definitions of spirituality and spiritual care in their practice. The factors which did not change were Religiosity (view that spirituality is only about religious beliefs) and Personal Care (taking account of people’s beliefs, values and dignity). In fact, the scores for the control group on Religiosity were higher than the intervention group at post and follow-up timepoints. High scores on this item suggest that participants are more likely to hold the view ‘that spirituality is only about religious beliefs’. Therefore, lower results for the intervention group around religiosity fit with the program content, which actively discouraged participants from considering spirituality as interchangeable with religion. Respecting people’s beliefs, values and dignity is well incorporated into most healthcare professional training, and therefore little difference between groups on this factor was not surprising.

The qualitative findings of this study enrich the quantitative findings. Answers to the question about “most significant change” at follow-up suggest that shifting perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care may be linked with levels of confidence or comfort. Such a finding reinforces the notion that a small change in attitude and understanding can bring about benefits that extend beyond knowledge alone. Participant satisfaction levels were high, suggesting that a two-module program had good levels of acceptability for staff, and the program was well attended. The majority of healthcare professionals undertaking the training completed both modules.

This study had a number of limitations. Although this was a controlled trial, participants were not randomised to the two conditions. The intervention was delivered at one site and the number of staff participating in the training was modest. Participant skills or behaviour change were only evaluated by self-report at the follow-up time point and we were unable to determine whether clients reported any changes as a result. Furthermore, due to the time constraints of the project, a six-week follow-up period was decided upon. This did not allow all the participants to apply what they had learnt from the program. Despite these limitations, the findings of this exploratory study would support larger, randomised controlled trials of spiritual care education programs in the field of rehabilitation.

5Conclusion

The program’s underlying principles were that spiritual care can be provided by all healthcare professionals and is relevant to staff in all areas of healthcare, including neurorehabilitation. Training which increases staff competency, comfort, confidence and understanding regarding the delivery of spiritual care will enhance the ability of healthcare services to embrace the needs of the whole person. That this training can be achieved over a brief period of time is promising and suggests that training need not be time-intensive or arduous for participants. Future research could expand the findings of this study by incorporating larger trials of the program and with rehabilitation professionals from a wider range of religious faith backgrounds. Intervention programs which address spirituality with rehabilitation clients and their family members directly would also be worthy of consideration. Such research will contribute to a growing acknowledgement that incorporating spiritual care into rehabilitation practice is both valuable and achievable.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the health professionals who participated in this study, and Royal Rehab, Liverpool Brain Injury Rehabilitation Unit, Prince of Wales Spinal Injuries Unit and Community of Christ for their support. We would also like to thank Jackie Francis for her assistance on this project.

References

1 | Austin, P. , Macleod, R. , Siddall, P. J. , McSherry, W. , & Egan, R. ((2016) ). The ability of hospital staff to recognise and meet patients’ spiritual needs: a pilot study. Journal for the Study of Spirituality, 6: (1), 20–37. |

2 | Best, M. , Butow, P. , & Olver, I. ((2016) ). Palliative care specialists’ beliefs about spiritual care. Support Care Cancer, 24: , 3295–3306. |

3 | Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. ((2006) ). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3: , 77–101. |

4 | Canda, E. R. , & Furman, L. D. ((2009) ). Spiritual diversity in social work practice: the heart of helping. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press. |

5 | Cerra, A. , & Fitzpatrick, K. ((2008) ). Can in-service education help prepare nurses for spiritual care? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25: (4), 204–209. |

6 | Cobb, M. , Puchalski, C. M. , Rumbold, B. (Eds.). ((2012) ).. Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

7 | Davis, D. E. , Rice, K. , Hook, J. N. , Van Tongeren, D. R. , DeBlaere, C. , Choe, E. , & Worthington, E. ((2015) ). Development of the sources of spirituality scale. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 62: (3), 503–513. |

8 | Fricchione, G. , & Nejad, S. ((2012) ). Resilience and coping. In Cobb, M. , Puchalski, C. , & Rumbold, B. (Eds.), Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare (pp. 367-373). Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

9 | Gallison, B. , Xu, Y. , Jurgens, C. , & Boyle, S. ((2012) ). Acute care nurses’ spiritual care practices. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 31: (2), 95–103. |

10 | Hodge, D. R. ((2013) ). Implicit spiritual assessment: an alternative approach for assessing client spirituality. Social Work, 58: (3), 223–230. |

11 | Johnstone, B. , Glass, B. A. , & Oliver, R. E. ((2007) ). Religion and disability: clinical, research and training considerations for rehabilitation professionals. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29: (15), 1153–1163. |

12 | Jones, K. F. , Dorsett, P. , Briggs, L. , & Simpson, G. ((2018) ). The role of spirituality in spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation: exploring health professional perspectives. Spinal Cord Series and Cases, 4: (1), 54. doi: 10.1038/s41394-018-0078-3 |

13 | Jones, K. F. , Dorsett, P. , Simpson, G. , & Briggs, L. ((2018) ). Moving forward on the journey: spirituality and family resilience after spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 63: (4), 521–531. doi: 10.1037/rep0000229 |

14 | Jones, K. F. , Pryor, J. , Care-Unger, C. , & Simpson, G. K. ((2018) ). Spirituality and its relationship with positive adjustment following traumatic brain injury: a scoping review. Brain Injury, 1-11. doi:10.1080/02699052.2018.1511066 |

15 | Jones, K. F. , Pryor, J. , Care-Unger, C. , & Simpson, G. K. ((2020) ). Rehabilitation health professionals’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care: the results of an online survey. NeuroRehabilitation, 46: (1), 17–30. doi: 10.3233/NRE-192857 |

16 | Jones, K. F. , Simpson, G. K. , Briggs, L. , & Dorsett, P. ((2016) ). Does spirituality facilitate adjustment and resilience among individuals and their families after SCI? Disability and Rehabilitation, 38: (10), 921–935. |

17 | Koenig, H. G. ((2012) ). Religion, spirituality, and health: the research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry, 2012: , 1–33. |

18 | McSherry, W. ((1997) ). A descriptive survey of nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. The University of Hull, Hull. |

19 | McSherry, W. , Draper, P. , & Kendrick, D. ((2002) ). The construct validity of a rating scale designed to assess spirituality and spiritual care. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 39: , 723–734. |

20 | Meredith, P. , Murray, J. , Wilson, T. , Mitchell, G. , & Hutch, R. ((2012) ). Can spirituality be taught to health care professionals? Journal of Religion and Health, 51: , 879–889. |

21 | NHS Education for Scotland. (2009). Spiritual Care Matters. Edinburgh, UK: NHS Education for Scotland. |

22 | NHS Education for Scotland. (2013). Spiritual Care. Retrieved from https://www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-training/by-discipline/spiritual-care.aspx |

23 | Oakley, E. T. , Katz, G. , Sauer, K. , Dent, B. , & Millar, A. ((2010) ). Physical therapists’ perception of spirituality and patient care: beliefs, practices, and perceived barriers. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 24: (2), 45–52. |

24 | Oxhandler, H. , Parrish, D. , Torres, L. , & Achenbaum, W. ((2015) ). The integration of clients’ religion and spirituality in social work practice: a national survey. Social Work, 60: (3), 228–237. |

25 | Paal, P. , Helo, Y. , & Frick, E. ((2015) ). Spiritual care training provided to healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Journal of Pastoral Care and Counselling, 69: (1), 19–30. |

26 | Pearce, M. J. , Pargament, K. , Oxhandler, H. , Vieten, C. , & Wong, S. ((2019) ). A novel training program for mental health providers in religious and spiritual competencies. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 6: (2), 73–82. doi: 10.1037/scp0000208 |

27 | Puchalski, C. , Ferrell, B. , Virani, R. , Otis-Green, S. , Baird, P. , Bull, J. , … Sulmasy, D. ((2009) ). Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12: , 885–904. |

28 | Puchalski, C. , & Romer, A. L. ((2000) ). Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 3: (1), 129–137. |

29 | Ross, L. , Leeuwen, R. , Baldacchino, D. , Giske, T. , McSherry, W. , Narayanasamy, A. , … Schep-Akkerman, A. ((2014) ). Student nurses perceptions of spirituality and competence in delivering spiritual care: a European pilot study. Nurse Education Today, 34: , 697–702. |

30 | Smith, W. B. , Ortiz, A. J. , Wiggins, K. T. , Bernard, J. F. , & Dalen, J. ((2012) ). Spirituality, resilience, and positive emotions. In Miller L. J. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Psychology and Spirituality (pp. 437-454). Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

31 | van Leeuwen, R. , Tiesinga, L. , Middel, B. , Post, D. , & Jochemsen, H. ((2009) ). The validity and reliability of an instrument to assess nursing competencies in spiritual care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18: , 2857–2869. |

32 | Walsh, F. ((2003) ). Family resilience: a framework for clinical practice. Family Process, 42: (1), 1–18. |

33 | White, B. , Driver, S. , & Warren, A. ((2008) ). Considering resilience in the rehabilitation of people with traumatic disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 53: (1), 9–17. |