The TennesseeWorks Partnership: Elevating employment outcomes for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The TennesseeWorks Partnership is an innovative and coordinated effort to ensure youth and young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) across the state have the aspirations, preparation, opportunities, and supports to access competitive and integrated work that contributes to their flourishing. Launched in 2012, our systems change project has made a deep and sustained investment in equipping: (a) young people with IDD to aspire toward competitive work from an early age; (b) families to pursue competitive work for their members with disabilities; (c) educators to prepare students for competitive work throughout their schooling; (d) service systems to support competitive work in every corner of the state; and (e) communities to receive the gifts and contributions of people with disabilities.

OBJECTIVE:

In this article, we describe the origins and organization of our collaborative, present central components of our approach to systems change, highlight progress and outcomes in each area, and share our investment in sustainability.

CONCLUSION:

We offer reflections on the complexities of spurring statewide change and recommendations for other research and practice in this area.

1Introduction

Adolescents with disabilities hold high aspirations for adulthood. Their visions for a good life after high school often revolve around themes like landing a great job, finding a good place to live, spending time with friends, participating in community life, enrolling in postsecondary education, and contributing in ways that make life better for others. Each of these aspirations is an important aspect of living an enjoyable and enviable life (Buntinx & Schalock, 2010; Kraemer, McIntyre, & Blacher, 2003). Yet these same experiences have remained out-of-reach for far too many young people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) in Tennessee and across the country (Butterworth et al., 2015; Henderson & Baird, 2014). When young people with IDD are connected to meaningful work experiences in their communities, achieving their other aspirations becomes much more likely. In addition to a paycheck, a good job contributes to a sense of accomplishment, self-worth, and independence; it gives young people a place to share their strengths and gifts in valued ways; it fosters new friendships and access to social supports; and it provides resources and connections that increase community involvement and contributions.

2The Tennessee context

In a state as varied and vast as Tennessee, changing the employment landscape for people with IDD is not without substantial challenges. Our state stretches 495 miles in length and includes more than 6.5 million culturally and ethnically diverse residents living in rural, suburban, and urban communities. Unemployment and underemployment among the nearly one million residents with disabilities were both persistent over time and pervasive throughout the state (Butterworth et al., 2015; Tennessee Department of Education, 2012). In the year of our launch, only one in five (19.5% ) of people with cognitive impairments were employed, many in segregated settings or jobs that did not match their interests. As we examined the myriad barriers that prevented people’s aspirations from meeting opportunities, we identified a number of salient issues to address. Expectations for employment were uneven among families, educators, and other professionals; existing policies inconsistently aimed toward integrated employment; the availability of strong professional development was limited; accessible resources and information were difficult to find; pursuit of integrated employment was not incentivized; our commitment to employment first did not always penetrate practice; silos were more common than sustained collaboration; and stories of struggles were more common than stories of success. These barriers emerged as recurring themes in our conversations with stakeholders, in the community gatherings we held across the state (Bumble, Carter, McMillan, & Manikas, in press; Carter et al., 2016), and in our surveys of parents and educators (Bethune, Carter, & O’Quinn, 2016; Blustein, Carter, & McMillan, 2016).

At the same time, the state was primed for movement. Tennessee had received two other federal grants focused on building the capacity of employers to hire youth with disabilities and the competencies of service providers to support integrated employment. Several key state agency leaders were eager to establish more coordinated efforts to expand employment opportunities. And early efforts were underway to promote awareness, evaluate existing services, and compile available data. It also became clear that Tennessee was a state rich with untapped assets and new allies that could be invited into this work. As we looked from Memphis to Bristol, we saw communities filled with citizens who could be invited and equipped to make movements that would expand local employment opportunities and supports (Harvey & Carter, 2014; Kidd, 2014).

3Statewide goals

We launched the TennesseeWorks Partnership as an innovative and coordinated statewide effort to ensure every youth and young adult with IDD would have the aspirations, preparation, opportunities, and supports to access competitive and integrated work. Although our goals have evolved throughout this initiative, our efforts presently focus on the following areas:

• Aligning service delivery systems and strengthening coordination to increase employment opportunities for Tennesseans with disabilities;

• Building shared community commitment to “Employment First” for individuals with disabilities;

• Increasing the number of businesses and employers throughout the state who actively seek out and hire individuals with disabilities;

• Making Tennessee a model public sector employer though actions to employ more people with disabilities and through policy and regulatory change; and

• Preparing students in Tennessee schools for employment throughout their education and connecting them to essential services and supports.

These goals reflect our recognition of the need for systemic changes that are ambitious, span service systems, and engage natural partners from every corner of our state.

4Our organizational structure

As we developed our application for the Partnership in Employment (PIE) Systems Change grant from the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AIDD), considerable interest was evident across Tennessee in improving the quality of transition services and increasing employment opportunities for youth. However, existing efforts were scattered across different groups and lacked a common focus. We recall multiple planning meetings in which key state leaders learned about existing initiatives about which they had not been aware. From the initial planning for the grant application, the PIE grant provided the impetus to (a) stitch together this work under a single umbrella, and (b) focus efforts on both the private and public sector.

In crafting our grant proposal, our grant-required Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was signed by both required and non-mandatory partners, including the Commissioner of the Department of Education, the Commissioner of the Department of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, the Commissioner of the Department of Labor and Workforce Development, the Commissioner of the Department of Human Services (administering agency for the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation), and the Executive Director of the Tennessee Council on Developmental Disabilities. Additionally, we received signed support from the Tennessee Developmental Disabilities Network and 16 agencies and organizations wanting to collaborate on this partnership. This collaboration has since grown to more than 50 private and public partners, with Vanderbilt serving as the backbone organization (Kania & Kramer, 2011).

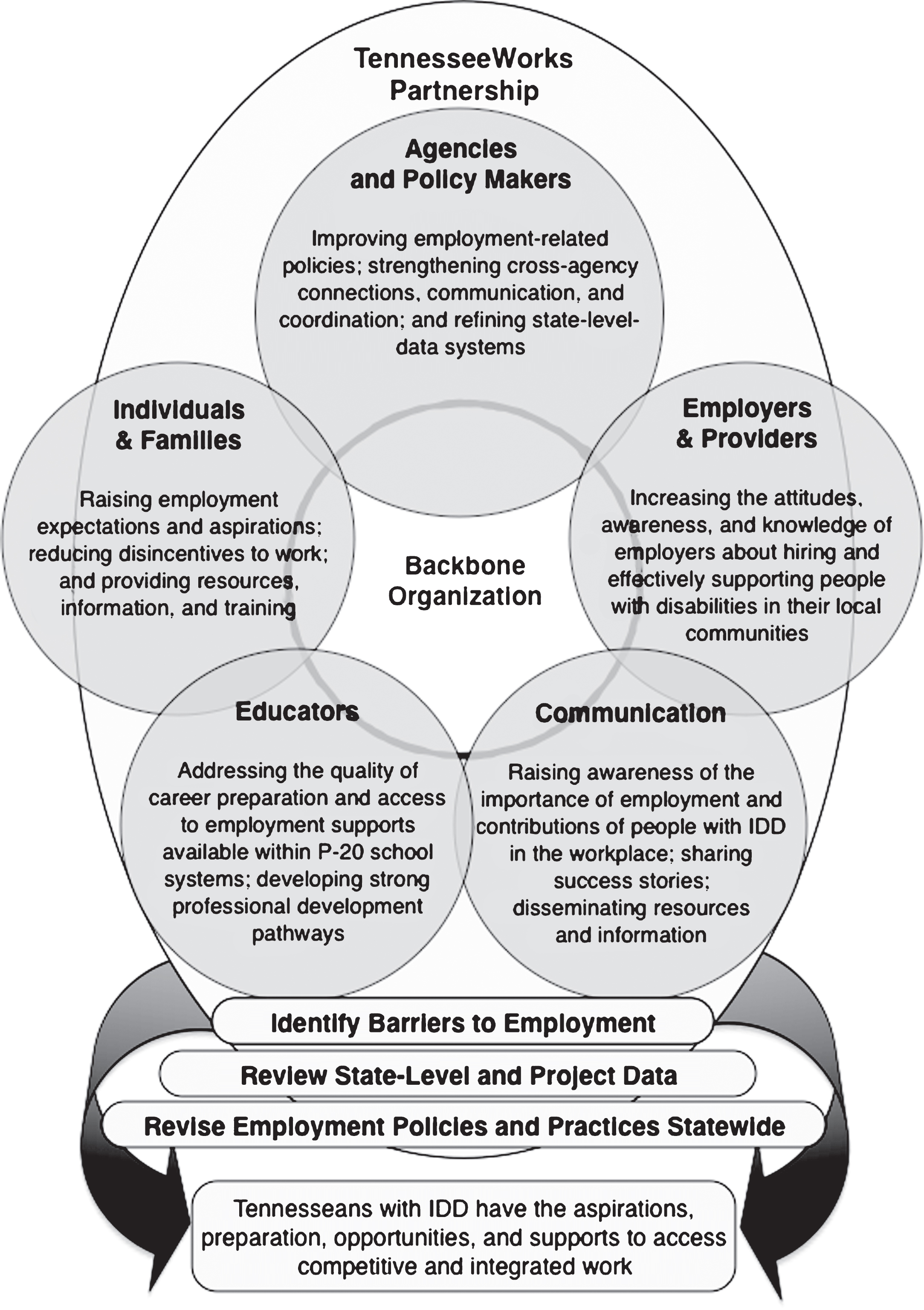

We meet quarterly as a Partnership to carry out our proposed plan. These full-day, working meetings have continued for five years and average 35– 60 attendees. A typical agenda includes policy and program updates; short presentations on current initiatives, emerging issues, and available data by members and invited guests; workgroup time; highlights of upcoming events and success stories; and time for networking. The Partnership also reviews and revises our state’s Employment First Strategic Plan, ensuring it is both a living document and a visible roadmap for all of our work. During and between these meetings, most activities are carried out by five stakeholder-focused workgroups addressing the areas of: (a) policy, (b) individuals and families, (c) education, (d) employers and providers, and (e) communication (see Fig. 1). These workgroups identify and act on needed areas of influence to accomplish our overarching goal.

Fig.1

Organization of Workgroups within the TennesseeWorks Partnership.

Early on, we all agreed the TennesseeWorks Partnership should serve as the overarching framework for every effort in the state aimed toward improving employment outcomes for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. This framing brought every employment-related activity under a single umbrella, helped brand TennesseeWorks as a movement much broader than a single grant, and ensures progress will continue even after grant funding ends. It also required we foster an atmosphere of collaboration, shared credit, and regular celebration of joint accomplishments. We take seriously Ralph Waldo Emerson’s observation that, “There is no limit to what can be accomplished if it doesn’t matter who gets the credit.”

With multiple federal employment grants and a constellation of initiatives underway among numerous partnership members, we wanted to avoid resources being poorly coordinated or inefficiently integrated. One vehicle used to facilitate this is the Employment Roundtable established by the Tennessee Council on Developmental Disabilities. The Council convenes the Roundtable on a monthly basis. Members include representatives from the Tennessee Departments of Education, Labor and Workforce Development, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, TennCare (the state’s Medicaid Agency), Health, Children’s Services, Human Services/Division of Vocational Rehabilitation, Mental Health and Substance Abuse and the State Treasurer’s Office (administers the ABLE Act program). Roundtable members share program updates and develop strategies to facilitate services for individuals who have fallen between the cracks in the service system. The group discusses ideas to improve cross-system program efficiency and effectiveness, updates the state’s Employment First Strategic Plan, develops an annual report to the Governor on accomplishments toward objectives in the Strategic Plan, and keeps our state’s Youth MOU updated. The Employment Roundtable members comprise the Public Policy workgroup for TennesseeWorks so we are able to perfectly coordinate the work of the two groups and avoid duplication of effort. Although its accent is on policy and state-level movements, the Roundtable also attends to key areas of concern in employment that are better addressed by multiple, rather than by single, state agencies. Most importantly, this group spearheads our efforts to establish and enact a shared commitment across agencies to integrated and competitive employment.

5Our approach and outcomes

Reflecting on the first five years of our efforts to elevate employment outcomes for Tennesseans with IDD, we identified eight areas in which we have made substantial investments and seen promising progress. Although most of these areas were outlined in our original application, some emerged along the way and all were addressed in somewhat different or deeper ways than we originally anticipated. We describe each area below by highlighting its importance and illustrating some of the ways it has been addressed within our work.

5.1Chasing (and raising) aspirations

Since the beginning, we have remained convinced that all of our work must be aimed toward the aspirations of young people with disabilities. There is no separate set of dreams for these young people; no parallel paths they plan to pursue. Our own conversations with Tennesseans with IDD affirm what research elsewhere confirms: the presence of a disability label does not reliably predict people’s aspirations for their own lives (Carter, 2015). Nationally, more than three fourths (79% ) of all high school students with an intellectual disability have a transition goal aimed toward work in the community (Wagner, Newman, Cameto, Garza, & Levine, 2005). They do not have dreams of underemployment, they do not aspire to piece-rate wages, and they do not say they anticipate for themselves a lifetime of exclusion from the workforce. More than half (53% ) of students with an intellectual disability nationally have a transition goal to live independently in the community. They do not have dreams of living in congregate settings and they envision much more than a life on the couch. And more than one fourth (26% ) of all high school students with an intellectual disability nationally have a transition goal to attend some type of post-secondary educational program. They do not want to miss out on lifelong learning opportunities, challenging coursework, and a real career pathway.

To this end, we strived to keep the aspirations of young people with IDD at the forefront of our work by engaging them in experiences to further elevate their aspirations and involving them actively in all aspects of this work. Although people with disabilities contributed to all of our workgroups, we established a designated workgroup focused on self-advocates (i.e., Individuals and Families). We designed our annual employment summit (called ThinkEmployment!) with youth and young adults with IDD as a primary audience. Area high schools and inclusive postsecondary programs bring scores of students for a day of vision casting, learning about career pathways, preparing for the workplace, and networking with employers. At our last two conferences, more than 250 young people with IDD were in attendance. In addition, we have supported the presence of students with disabilities at our annual Disability Day on the Hill events. Students learn about recent policy developments, meet individually with their legislators, and advocate for issues that impact their career and community aspirations.

5.2Elevating expectations

The expectations families, educators, other professionals, and others hold can have a direct impact on the employment outcomes of youth with IDD. More than almost any other factor, expectations shape outcomes (Carter, Austin, & Trainor, 2011; Doren, Grau, & Lindstrom, 2012). Nationally, high school students with severe disabilities whose parents expected them to work were 5 times as likely to have paid, community employment in the early years after graduation (Carter, Austin, & Trainor, 2012). Similarly, the expectations of educators and service providers significantly influence the employment opportunities available to students during adolescence and beyond. High school students with severe disabilities who have teachers who expect them to obtain a summer job are 15 times more likely to obtain that paid job in the community (Carter, Austin, et al., 2010). Yet, too many parents struggle to envision a future for their child that involves integrated employment in the community. Furthermore, secondary transition programs inconsistently embed a strong commitment to preparing students for competitive work. We recognized the importance of working toward ensuring every child with IDD in Tennessee hears the message— from a very early age and from multiple people— that they have something of value to contribute in the workplace.

We have undertaken myriad efforts to help individuals across our state develop a vision for and commitment to integrated, competitive employment as the first and desired option for young people with IDD. Early in our project, we launched a study aimed at understanding the views of more than 2,400 parents across our state on employment for their daughters and sons with IDD: their post-school expectations, the factors that shape those expectations, and the concerns they hold (Blustein et al., 2016; Gilson, Bethune, Carter, & McMillan, in press). We learned that a large proportion of parents (83% ) placed considerable importance on part- or full-time employment in the community for their child in the early years after leaving high school. Indeed, more than twice as many parents in our state considered community employment to be important relative to sheltered employment. Moreover, these parents prioritized more qualitative dimensions of work life (e.g., having a job that brings personal satisfaction, matches their child’s interests, provides opportunities for interaction, allows for friendship development) over elements we more often tend to measure (e.g., rate of pay, number of hours). Understanding these priorities provide us with important insight into the kinds of experiences that might matter most for these families.

We also have taken steps to raise expectations among educators charged with preparing transition-age youth with IDD for college and career pathways after high school. We completed three large-scale surveys involving more than 1,500 middle and high school special educators (e.g., Bethune et al., 2016; TennesseeWorks, 2013-2014). Each helped us identify and develop resources teachers would need to strengthen their commitment toward improving post-school employment outcomes. This information has been incorporated into multiple live and online trainings designed to equip teachers throughout the state.

The expectations of employers have also garnered our attention. Deficit-based views of people with disability still dominate in many corners of our communities— statewide and nationally (Burke et al., 2013). For many employers, invitations to hire a person with IDD are accompanied more by impressions of what such a person cannot do or might struggle to do than by the contributions they have to make. To introduce a counterpoint to prevailing societal attitudes, we launched an annual statewide employment awareness campaign called “Hire my Strengths” (www.hiremystrengths.org). This coordinated and collaborative effort is highlighting the strengths, talents, and gifts people with disabilities have to offer within the workplace (Carter et al., 2015), as well as helping more employers see the “business case” for integrated employment (TennesseeWorks, 2014).

5.3Adopting a data-driven approach

Decisions about policy and practice should draw upon the best available data. In their conceptual model of variables marking states making the most movements on integrated employment, Hall, Butterworth, Winsor, Gilmore, and Metzel (2007) stressed the role of data both in communicating the importance of employment and to introduce accountability. Likewise, calls throughout the fields of transition and special education have emphasized data-based decision making and the contributions research has made to spurring noticeable improvements in outcomes of transition-age youth (Carter et al., 2013). To this end, we embedded research and other data collection throughout all of our activities to ensure we could make wise decisions about what we should do, how we should do it, and whether it worked.

One aspect of this approach has involved identifying and sharing already available and newly acquired data. We mapped existing data sources across agencies and other sources (e.g., education, labor, higher education, vocational rehabilitation), creating a publicly available dashboard. The purpose of the dashboard (www.tennesseeworks.org/data-dashboard) has been to describe the Tennessee landscape on issues related to transition and employment, to make accessible data that were previously difficult to find or interpret, and to identify gaps in available information that the Partnership could work to fill. Moreover, we are drawing upon these data to identify benchmarks as we continually refine our state’s Employment First Strategic Plan. As we continue this work, we plan to draw more heavily upon the state’s integrated, longitudinal data system. This dataset combines and integrates data from multiple agencies, enabling a long-term look at the experiences and outcomes of young people with and without disabilities in our state.

Another important accent has been on designing new studies that answer questions of importance to the TennesseeWorks Partnership. The involvement of a research-intensive university like Vanderbilt introduces both interest in and capacity to embed rigorous studies throughout our systems-change work. As referenced elsewhere in this article, we have undertaken studies addressing how “community conversation” events can inform and spur local changes in employment opportunities (Bumble et al., in press; Carter et al., 2016; Bumble, Carter, McMillan, Manikas, & Bethune, in press), parental expectations and resource needs related to employment and other post-school outcomes (Blustein et al., 2016; Gilson et al., in press), transition-related professional development needs and pathways among special educators (Bethune et al., 2016), family perspectives on the conversion of sheltered workshops (Carter, Bendetson, & Guiden, 2016), and employer attitudes and recommendations regarding hiring people with disabilities (currently underway). In addition, we are undertaking secondary analyses of employment and transition data available within selected state-level data sources (e.g., National Core Indicators, Tennessee Longitudinal Data Systems). This complementary investment in scholarship recognizes that the answers and approaches we discover in Tennessee likely have relevance to other states that also are striving to expand employment opportunities for their residents with IDD. At the same time, we have been conscious of the importance of first sharing study findings back within the Partnership before disseminating them in professional journals beyond our state.

5.4Building capacity and competence

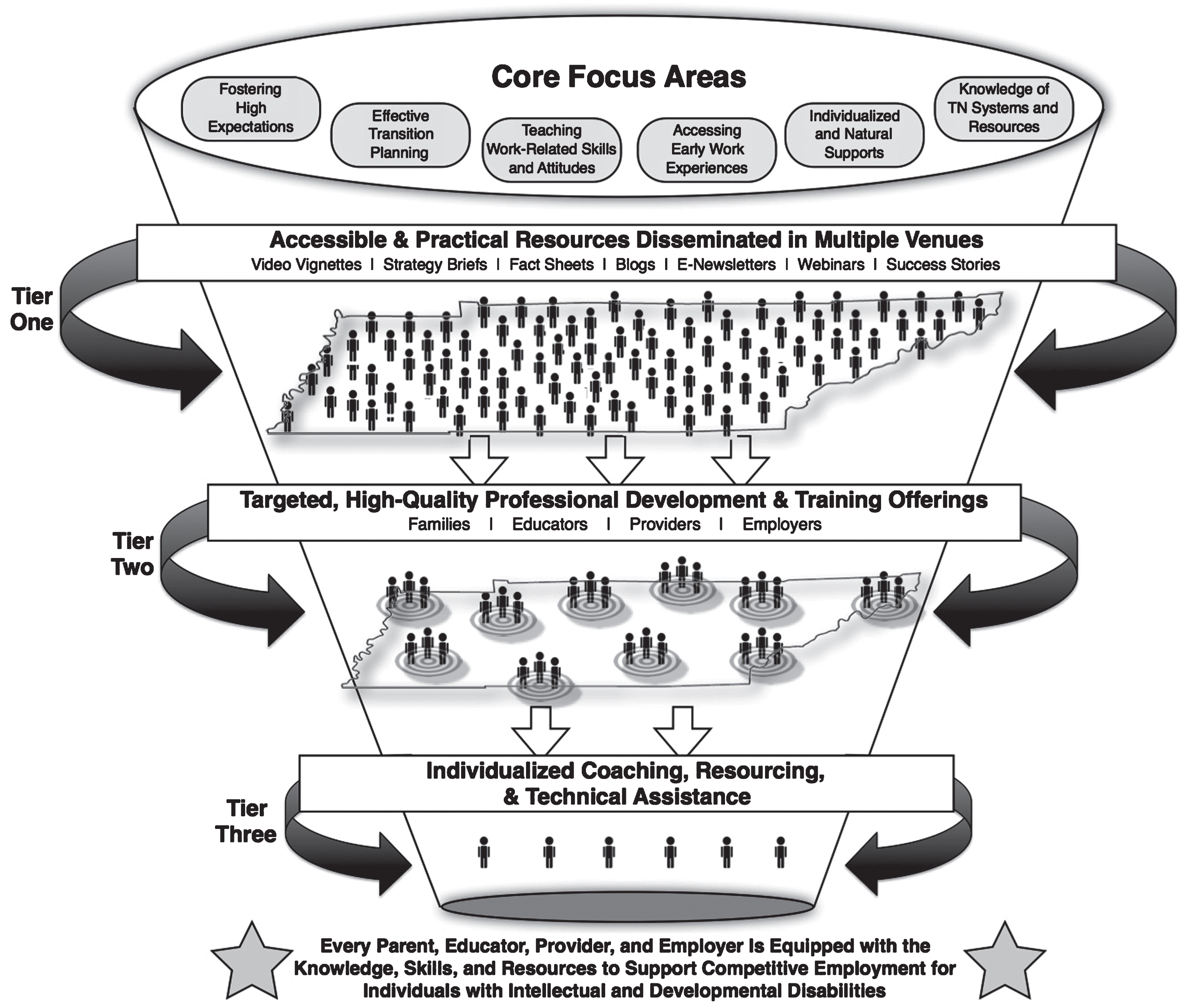

To shift employment outcomes in substantive ways, we knew that educators, service providers, families, employers, and others across our state would need to be fluent in those strategies and supports shown to have the very best chance of making an impact. As is true elsewhere across the country, these stakeholders often report difficulty finding effective training and practical resources addressing best practices related to transition and integrated employment (Brock, Huber, Carter, Juarez, & Warren, 2014; Gilson et al., in press; Morningstar & Benitez, 2013). The more pressing challenge lies not in the absence of research-based practices, but rather in the extent to which the best of what we know works is actually penetrating practice in widespread ways. Therefore, we have taken considerable efforts to design and implement professional development and training for educators, families, employers, providers, and others so their efforts are steeped in and marked by best practices. Through a review of relevant research and policy— as well as consideration of those barriers mentioned previously in this article— we initially identified six areas of emphasis: high expectations for competitive work, effective transition planning, enhancing work-related skills and attitudes, access to early work experiences, individualized and natural supports, and knowledge of Tennessee systems and resources.

To ensure individuals across the state were equipped and supported to implement these core practices with every young person with IDD, we have been building a tiered and multi-faceted approach to training and resource dissemination (see Fig. 2). Specifically, this involves developing:

• Accessible and practical resources in each of the six core focus areas that are made available in multiple formats and disseminated widely to everyone in the state (Tier 1);

• More targeted professional development and training offerings for families, educators, professionals, and employers who need more in-depth information on implementing practices in the six core areas (Tier 2); and

• Avenues for individuals who need one-to-one coaching or more individualized support to have access to intensive resources or assistance (Tier 3).

Fig.2

Multi-Faceted Approach to Training and Resource Dissemination.

Fully developed, all three tiers will operate concurrently and serve to build capacity and commitment throughout every region across the state.

One primary example of work in this area has been our development of Transition Tennessee, the state’s new online portal for high-quality, on-demand professional development (www.transitiontn.org). This funded partnership with the Tennessee Department of Education ensures comprehensive and free training on best practices in transition is available to educators working in all of the state’s 142 school districts. Courses address multiple topics (e.g., guiding principles in transition, transition assessment, transition planning, pathways to employment, pathways to community living, pathways to postsecondary education, supports and partnerships) and incorporate engaging presentations, practical resources, reflection tools, illustrative videos, success stories, searchable databases, and case examples. For employers, we have held more than 50 employer outreach presentations (involving more than 1,600 employers) addressing why businesses should hire Tennesseans with disabilities, as well as delivered shared trainings with agencies and American Job Centers in the state. For parents, we have supported the launch of new family coalitions in multiple cities addressing topics such our state’s new waivers, the ABLE Act, advocating among state legislators, and futures planning. Finally, as a venue for joint training across stakeholder groups, we host an annual summit (called “Think Employment!”) and integrate employment- and transition-focused training into existing professional development events (e.g., local, regional, and state conferences and workshops).

5.5Making information accessible

Within academic circles, peer-reviewed journals, policy documents, and conference gatherings are the primary pathways through which research-based practices are shared. Yet, our surveys of parents and educators found they prioritized alternative pathways for accessing needed information, such as practice guides, downloadable resources, websites, videos, and apps (Bethune et al., 2016; Gilson et al., in press). Likewise, employers and community leaders were unlikely to be part of formal groups focused on disability issues. We knew we would have to provide multiple pathways for getting timely, accessible, and actionable information into the hands of professionals, employers, and families across the state. Moreover, this information could not be locked behind journal subscriptions, organizational memberships, or technical jargon.

We began by creating a one-stop online clearinghouse for information and resources related to promoting employment and successful transitions for individuals with disabilities (www.tennesseeworks.org). The website provides an overview of the TennesseeWorks Partnership and organizes targeted content by stakeholder group (i.e., self-advocates, families, educators, employers, agencies). It also features upcoming events, our data dashboard, success stories, a video library, and searchable resource databases. Although the website is maintained by our backbone organization, resources and events are contributed by all of our partners. The site draws thousands of unique visitors per month. In addition, we push out news and information to our growing number of subscribers through social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), weekly blogs, a monthly newsletter, and other just-in-time avenues. Each of the workgroups suggests content for these dissemination pathways to ensure their relevance and completeness.

5.6Refining policies

Meaningful policy change is a primary purpose of AIDD’s investment in states through PIE. Through the work of our Employment Roundtable policy workgroup (described previously), we have strived to align state policies in ways that more strongly prioritize and support integrated and competitive employment. These monthly meetings of key agency and organization representatives provide the consistency, focus, and leadership required to carefully identify state polices that need to be recommended, reviewed, revised, or repealed. Numerous examples of the effectiveness of working in a coordinated manner have been evident throughout the short history of this Partnership.

Among the earliest successes of our project was the signing of the Employment First Executive Order by Gov. Bill Haslam in 2013. The order established the Governor’s Employment First Taskforce and requested an annual report to the governor. Another early success was retaining age 14 as the beginning of transition planning in Tennessee. Although the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act had increased the age to 16, Tennessee had not followed suit. When a proposal went to the State Board of Education to increase the age to 16, the TennesseeWorks Partnership organized individuals with disabilities, families, educators, and policymakers to articulate the significance of retaining this earlier starting point for planning. Through written and oral testimony at a public hearing, we were successful in convincing the State Board not to make this change.

Recognizing college as an important pathway to future careers, we also worked to develop inclusive higher education programs in Tennessee through the Tennessee Alliance for Inclusive Higher Education. When The Arc Tennessee and the Tennessee Disability Coalition proposed legislation to provide students with IDD in inclusive higher education programs the same lottery-funded scholarship that other Tennessee students receive, our Partnership encouraged stakeholders to let members of the Tennessee Legislature know about the elevated employment outcomes graduates of these programs experienced. Tennessee’s STEP UP law now supports college students with IDD for up to 4 years of scholarship funding.

Our involvement in shaping policies cuts across multiple agencies. For example, the Tennessee Department of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities’ provider manual, so key to systems change, has been amended multiple times. Throughout this process, the department has shared information about these changes with the Partnership and invited the employer and provider workgroup to provide comments and suggest revisions as it was being updated. Likewise, we have contributed substantively to developments related to Tennessee’s implementation of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). Although we had originally planned to create a new MOU related to serving adults with disabilities, we decided that involvement in the new comprehensive state plan would be more effective. As the state plan was developed by the Tennessee Department of Labor (the lead agency), the Partnership received updates, offered feedback, and provided many of the working relationships required by the law. We also worked closely with TennCare— our state’s Medicaid agency— to develop and introduce Tennessee’s Employment and Community First choices programs. From the beginning of the Partnership, we knew long-term services and supports provided by Medicaid would be key to finding and keeping integrated, competitive employment for Tennesseans with the most significant needs. In 2012, more than 7,000 Tennesseans with disabilities were on the waiting list and waiver services were offered only to individuals with an intellectual disability. Managed care programs now have several priority categories, including transitioning youth who want to work, and services have also been expanded to include those with developmental disabilities.

As part of our state’s three-year Employment First Strategic Plan, we have identified a number of needed emphases. For example, we continue working to address subminimum wages by identifying policy changes and developing practice briefs with Alaska and the Institute for Community Inclusion. At the request of almost every partner, we launched a working committee on supported decision making. Our plans include developing a white paper, educating key groups, and introducing new legislation. And we are outlining additional policy and practice movements spanning the areas of education, family supports, vocational rehabilitation, and workforce. The full strategic plan, updated annually, is available at http://www.tn.gov/didd/article/employment-first-task-force.

5.7Engaging communities

A central thrust of AIDD’s Partnerships in Employment grant mechanism is to enhance collaborations across existing state systems and to improve statewide policies and practices. Although improving formal services and supports is essential to this endeavor, it is at the local level that polices and practices are carried out to improve the outcomes of individual citizens. Yet many communities are uncertain about how to move in coordinated ways that lead to expanded employment opportunities for their residents with IDD. And rarely are the ideas of local communities seen as an essential source of input for systems change efforts. A hallmark of our project has been our efforts to hear from, engage, and raise awareness among community members who are outside of the service system, but still comprise critical allies and advocates for employment (e.g., businesses, civic leaders, community groups, congregations, families).

Community conversations have been our primary approach for listening to and learning from Tennesseans about promoting pathways to employment and other aspects of community life. These creative and engaging gatherings invite a cross-section of diverse stakeholders into an asset-based dialogue on practical ways of addressing local employment barriers (Carter & Bumble, in press; Carter et al., 2016). Individuals from within and beyond the disability service system come together for a two-hour conversation in which they share their best ideas for expanding opportunities locally (e.g., What can we do as a community to increase meaningful employment opportunities for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities? How might we work together in compelling ways to make these ideas happen here in this community?). Across the multiple rounds of conversation, several hundred ideas are generated that reflect the community’s commitments, culture, and capacity. To date, we have hosted or supported more than 25 community conversation events across the state involving more than 1500 citizens. Examining themes emerging within and across events held across geographically diverse locales enabled us to identify a common set of needs around which to focus our statewide change efforts (i.e., developing employment opportunities, undertaking community-wide efforts, strengthening school and transition services, equipping people with IDD to be competitive applicants, enhancing inclusive workplaces, supporting families in transition). Examples of follow-up actions have included developing new resources for families and employers, creation of the new professional development portal for educators, and the sharing of success stories of individuals and employers.

Other efforts also reflect our commitment to exploring possibilities beyond the service system. For example, we held 15 listening forums for parents whose sons and daughters with IDD were served within sheltered workshops. These events— which involved an adaption of the community conversation approach— focused on what supports or assurances would need to be in place for parents to consider pursuing integrated employment in the community (Carter, Bendetson, & Guiden, 2016). We developed a host of online resources, toolkits, and videos to encourage and equip employers to hire people with IDD. These materials responded to a recurring theme from community conversations that potential employers would remain reluctant without successful examples and practical guidance. And we assisted congregations in implementing the Putting Faith to Work model, which empowers faith communities to support people with disabilities as they find and maintain employment aligned with their gifts, passions, and skills (Carter, Endress, et al., 2016). Congregations assembled small teams who personally learned about a member’s passions and gifts, drew upon their social networks (within and beyond the congregation) to identify employers who might need exactly those assets, and provided the support and encouragement needed to obtain and maintain that job.

5.8Telling compelling stories

From the outset, we knew it would be important to tell Tennessee stories about the importance of integrated employment in Tennessee; the pathways for making it happen in Tennessee; and the impact on Tennesseans with IDD, their families, and their communities. In other words, our partners and allies wanted local examples illustrating how meaningful employment experiences could happen here. We also recognized these stories needed to be shared in multiple venues and using diverse modes of communication. Therefore, we undertook extensive efforts to craft and communicate these stories throughout the state. For example, our Partnership has collaborated on more than 50 short videos illustrating promising practices, core principles, stakeholder perspectives, and successful employment experiences (see www.tennesseeworks.org/videos). We gathered and shared the employment stories of individuals, families, employers, educators, (Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, 2014; www.tennesseeworks.org/success-stories). We have encouraged and equipped individuals with IDD and their families to tell their stories in person to legislators at our annual Disability Day on the Hill event.

6Sustaining our efforts

Our sights have been set on sustainability since the inception of our Partnership. We emphasized that TennesseeWorks was broader than any one grant. We had all seen too many grants and other special initiatives created, do great work, and then end when the time-limited funding went away. Because several initiatives already existed in Tennessee, we worked across projects to outline shared, overarching goals aimed toward improving employment outcomes.

One way we did this was by embedding grant activities into the work of individual agencies. This was especially true of work being done by the state’s Department of Education, TennCare (the state’s Medicaid agency), the Department of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, and the Department of Human Services/Vocational Rehabilitation. For example, the Tennessee Department of Education recently contracted with Vanderbilt University to create their online portal for high-quality, on-demand professional development around transition. Likewise, the state’s Vocational Rehabilitation began exploring a contract for training and technical assistance for vocational rehabilitation counselors, particularly those now working with students beginning at age 14.

Tennessee has an especially strong Tennessee Developmental Disabilities network, including the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center UCEDD, the UT Boling Center UCEDD, the Tennessee Council on Developmental Disabilities, and Disability Rights Tennessee, that meets monthly to work on joint initiatives. Drawing upon this network for key coordination of continuing work has already been very effective. After our AIDD funding has ended, we know the Council will continue to convene the Employment Roundtable, Disability Rights Tennessee will continue with work in both education/employment policy and supported decision making, and the two UCEDDs will continue to support the state’s focused employment agenda. We also are discussing avenues for continuing to support the quarterly meetings of the TennesseeWorks Partnership, the expansion of the TennesseeWorks website, and other aspects of the project.

7Critical challenges

This AIDD-funded systems change grant has taught us much about maintaining momentum amidst frequent changes in key leadership and staff in every department of state government. Since the signing of the original MOU required for the AIDD grant, every commissioner has changed, as has key leadership in every department. However, having an MOU in place— which laid out agreement by each state agency— has proved essential as names and faces have changed. Our Employment Roundtable— with planned meeting times and structured agendas— has also helped maintain our momentum. Before this Partnership, we would be lucky to hear about a key department change and even luckier to be able to partner with new staff coming onto the projects. Now, when departments know they will have key personnel changes, we are notified in advance and key staff are briefed on the importance of participating within the TennesseWorks Partnership, Employment Roundtable, and Governor’s Employment First Taskforce.

Another challenge has been our commitment to spur movements in all corners of the state. Many of Tennessee’s 95 counties are rural, where systems change can look quite different from systems changes in our urban areas. Maintaining broad representation in the TennesseeWorks Partnership and our workgroups has helped us keep this commitment at the forefront of all we do. Moreover, the youth MOU addresses systems changes at both the state and the local level. Among the best examples of activities at the local level was Vocational Rehabilitation’s pilot to implement the pre-employment transition services central to WIOA. Vocational Rehabilitation piloted a program in the Jackson area and replicated all the agencies that had signed on to our youth MOU. From there, the local buy-in expanded to be a very effective local replication.

Another challenge involves ensuring we are serving all youth and young adults, including those from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. We are working toward making more of the materials on the TennesseeWorks website available in multiple languages. We partner with projects at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center (UCEDD) that serve diverse families (e.g., Multicultural Disability Outreach Program, Tennessee Disability Pathfinder). We also hosted a community conversation event entirely in Spanish and focused on the Latin American community. Expanding opportunities and improving outcomes for every Tennesseans demands that we be even more strategic in exploring new pathways for equipping and supporting the diversity of young people with IDD across our state.

8Lessons learned

The Partnerships in Employment systems change grant from AIDD has provided a powerful catalyst for changing the employment landscape in Tennessee. As we reflect back on the commitment, capacity, and community partners that now exist in our state, we are reminded of how critical this type of seed funding can be to supporting systems change. Much of our work would not have been accomplished within the scope of a one- or three-year grant. Spurring systemic change takes time (Hall et al., 2007; Ryndak, Reardon, Benner, & Ward, 2007). Having five years of funding allowed us to both pace our efforts (by avoiding having to accomplish everything in the first year) and push our efforts (by providing a clear deadline when major movements had to have been underway).

This project reaffirmed for us the power of personal relationships. Key relationships have developed among project leadership and state agencies and also among agencies even as personnel changed. By working closely together over time, we came to know the needs, interests, and capabilities of our partners. We also invested time getting to know one another in more personal ways, developing both trust and friendships that enabled us to navigate sometimes difficult conversations and challenging movements.

We also learned of the necessity of engaging partners beyond the traditional disability system. Communities across our state are rich in people and programs that have much to bring to— and gain from— involvement in employment change efforts. Our community conversations events introduced us to employers, civic leaders, community groups, congregational leaders, families, neighbors, and many others who could see this issue with a fresh lens and a local perspective. Many of the most practical and powerful ideas we heard came from corners of our state that might not have otherwise had a voice— an employer who had not previously considered hiring a person with a disability, a mayor who cared deeply about helping all of his city flourish, a parent who had the ear of his entire community, a pastor who suggested her congregation could be part of helping its members with disabilities find employment, or a state leader who called on his fellow legislators to strengthen supports available to students with disabilities.

While there is still much work to be done, the value of good data has been demonstrated throughout our project. When we initially shared the idea of surveying at least 2,000 families in Tennessee, some members were skeptical it could be done. However, by sharing recruitment responsibilities and expenses across the Partnership, we far exceeded that recruitment goal. Moreover, we reached many families on Tennessee’s waiting list for long-term supports and services. Hearing from these families about their high expectations for employment and desire for resources has had considerable impact on state policy makers and state leadership. We can say the same about our study of the practices and professional development needs of special educators and transition staff across the state. These data have directly informed our design of new resources and trainings to ensure they meet the needs of Tennessee teachers.

Systems change can be a slow process and rarely proceeds on predictable pathways. The importance of patience and persistence also comes to mind in thinking about the powerful youth MOU that was signed by six state agencies. From early drafts to later drafts, across many meetings, and through multiple rejections by departmental attorneys, we remained committed to having the youth MOU as the framework for our operating agenda. The MOU is now a living document, referred to at our Employment Roundtable meetings and is revised on a regular basis under the leadership of the Tennessee Council on Developmental Disabilities. But it required a long-view perspective on this work and diligence to bring it to fruition.

Finally, we are reminded of the importance of celebrating successes. Change efforts like this can at times be discouraging; at other times overwhelming. Several times we have taken a step back to highlight and celebrate the successes. Those include the youth MOU, the expanded STEPUP legislation, the data dashboard, the Employment Roundtable, the new Employment and Community First Choices Program, and the list goes on. As a Partnership, we benefited from periodic refreshers of why this work matters and reminders of how it is making a difference in the lives of Tennesseans with disabilities.

9Conclusion

The aspirations of young people with IDD drive the work of the TennesseeWorks Partnership. We are striving to expand opportunities and supports so that every person in our state is able to share their talents, passions, gifts, and friendship within the workplace. For young people with disabilities, a satisfying job can have a profound impact on their well-being and quality of life. But we also affirm that our communities have much to gain by supporting the contributions of people with disabilities in the workplace. Recognition of this reciprocity pushes us to pursue this work further in the years ahead.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work came through a Projects of National Significance grant from the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, Administration for Community Living, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and Grant 90DN0294 to the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities. We are grateful for the contributions of Lauren Bethune, Jennifer Bumble, Shimul Gajjar, Alison Gauld, Carly Gilson, Amy Gonzalez, Carrie Guiden, Michelle Halman, Sarah Harvey, Lynette Henderson, Rachael Jenkins, Yovancha Lewis-Brown, Bob Nicolas, Jeremy Norden-Paul, Lauren Pearcy, Blake Shearer, Janet Shouse, Kelly Wendel, and the more than 40 organizations and agencies comprising the TennesseeWorks Partnership.

References

1 | Bethune L. , Carter E. W. , & O’Quinn C. ((2016) ). The transition assessment practices, priorities, and partners of special educators in secondary schools. Manuscript in preparation. |

2 | Brock M. E. , Huber H. B. , Carter E. W. , Juarez A. P. , & Warren Z. E. ((2014) ). Statewide assessment of professional development needs related to educating students with autism spectrum disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29: , 67–79. doi: 10.1177/1088357614522290 |

3 | Bumble J. L. , Carter E. W. , McMillan E. , Manikas A. , & Bethune L. (in press). Community conversations on integrated employment: Individualization and impact. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. |

4 | Bumble J. L. , Carter E. W. , McMillan E. , & Manikas A. (in press). Using community conversations to expand employment opportunities for people with disabilities in rural and urban communities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. |

5 | Buntinx W. H. E. , & Schalock R. L. ((2010) ). Models of disability, quality of life, and individualized supports: Implications for professional practice in intellectual disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 7: , 283–294. |

6 | Burke J. , Bezyak J. , Fraser R. T. , Pete J. , Ditchman N. , & Chan F. ((2013) ). Employers’ attitudes towards hiring and retaining people with disabilities: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counseling, 19: , 21–38. doi: 10.1017/jrc.2013.2 |

7 | Butterworth J. , Winsor J. , Smith F. A. , Migliore A. , Domin D. , & Timmons J. , & Hall A. C. ((2015) ), StateData: The national report on employment services and outcomes. Boston, MA: Institute for Community Inclusion. |

8 | Carter E. W. ((2015) ). Ending segregation... in education and beyond. Invited presentation to the President’s Committee on People with Intellectual Disabilities. Washington, DC. |

9 | Carter E. W. , Austin D. , & Trainor A. A. ((2011) ). Factors associated with the early work experiences of adolescents with severe disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49: , 233–247. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-49.4.233 |

10 | Carter E. W. , Austin D. , & Trainor A. A. ((2012) ). Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23: , 50–63. doi: 10.1177/1044207311414680 |

11 | Carter E. W. , Bendetson S. , & Guiden C. ((2016) ). Conversations that matter: Parent perspectives on the pathway from sheltered employment. Manuscript in preparation. |

12 | Carter E. W. , Blustein C. L. , Bumble J. L. , Harvey S. , Henderson L. , & McMillan E. ((2016) ). Engaging communities in identifying local strategies for expanding integrated employment during and after high school. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121: , 398–418. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-121.5 |

13 | Carter E. W. , Boehm T. L. , Biggs E. E. , Annandale N. H. , Taylor C. , Logeman A. K. , & Liu R. Y. ((2015) ). Known for my strengths: Positive traits of transition-age youth with intellectual disability or autism. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40: , 101–119. doi: 10.1177/1540796915592158 |

14 | Carter E. W. , Brock M. E. , Bottema-Beutel K. , Bartholomew A. , Boehm T. L. , & Cease-Cook J. ((2013) ). Methodological trends in secondary education and transition research: Looking backward and moving forward. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 36: , 15–24. doi: 10.1177/2165143413475659 |

15 | Carter E. W. , & Bumble J. L. (in press). The promise and possibilities of community conversations: Expanding employment opportunities for people with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. |

16 | Carter E. W. , Ditchman N. , Sun Y. , Trainor A. A. , Swedeen B. , & Owens L. ((2010) ). Summer employment and community experiences of transition-age youth with severe disabilities. Exceptional Children, 76: , 194–212. doi: 10.1177/001440291007600204 |

17 | Carter E. W. , Endress T. , Gustafson J. , Shouse J. , Taylor C. , ... Allen W. ((2016) ). Putting faith to work: A guide for congregations and communities on connecting job seekers with disabilities to meaningful work. Nashville, TN: Collaborative on Faith and Disability. Available at https://www.puttingfaithtowork.org |

18 | Doren B. , Grau J. M. , & Lindstrom L. E. ((2012) ). The relationship between parent expectations and postschool outcomes of adolescents with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 79: , 7–23. doi: 10.1177/001440291207900101 |

19 | Employment First Taskforce. ((2016) ), Expect employment: Employment First Taskforce report to the Governor. Nashville, TN: Author. |

20 | Gilson C. B. , Bethune L. , Carter E. W. , & McMillan E. (in press). Informing and equipping parents of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. |

21 | Hall A. C. , Butterworth J. , Winsor J. , Gilmore D. , & Metzel D. ((2007) ). Pushing the employment agenda: Case study research of high performing states in integrated employment. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 45: , 182–198. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556(2007)45[182:PTEACS]2.0.CO;2 |

22 | Harvey S. , & Carter E. W. ((2014) ). Uncovering new pathways to employment through community conversations. Breaking Ground, 73: , 8–10. |

23 | Henderson L. , & Baird J. ((2014) ), Report on National Core Indicators: Tennessee data for 2013–14, Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities. |

24 | Institute for Corporate Productivity. ((2014) ), Employment people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Seattle, WA: Author. |

25 | Kania J. , & Kramer M. ((2011) ). Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9: (1), 36–41. |

26 | Kidd T. L. ((2014) ). Calling the community together in Lawrenceburg to talk about employment. Breaking Ground, 73: , 10. |

27 | Kraemer B. R. , McIntyre L. L. , & Blacher J. ((2003) ). Quality of life for young adults with mental retardation during transition. Mental Retardation, 41: , 250–262. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2003)41<250:QOLFYA>2.0.CO;2 |

28 | Morningstar M. E. , & Benitez D. ((2013) ). Teacher training matters: The results of a multistate survey of secondary special educators regarding transition from school to adulthood. Teacher Education and Special Education, 36: , 51–64. doi: 10.1177/0888406412474022 |

29 | Ryndak D. , Reardon R. , Benner S. , & Ward T. ((2007) ). Transitioning to and sustaining district-wide inclusive services: A -year study of a district’s ongoing journey and its accompanying complexities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 32: , 228–246. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.32.4.228 |

30 | Tennessee Department of Education. ((2012) ), Indicator 14 data. Nashville, TN: Author. |

31 | TennesseeWorks. ((2013) –(2014) ). Surveys of Tennessee transition teachers. Unpublished raw data. |

32 | TennesseeWorks. ((2014) ), Employer business case fact sheet. Nashville, TN: Author. |

33 | Vanderbilt Kennedy Center. ((2014) ). Tennessee kindred stories of disability: Special issue: Employment. Nashville, TN: Author. |

34 | Wagner M. , Newman L. , Cameto R. , Garza N. , & Levine P. ((2005) ). After high school: A first look at the postschool experiences of youth with disabilities. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. |