When good is no longer good enough: Transitioning to greatness

Abstract

BACKGROUND: More than 50 years after the Civil Rights Bill banned racial segregation in the workplace, people with disabilities continue to face a culture that largely accepts their segregation and discrimination as a matter of course. Many organizations are challenged by the status quo today: Isn’t providing employment services to people with disabilities the way we always have good enough? The answer: Absolutely not! Jim Collins (2001) proposes that good is the enemy of great. Fortunately, moving from good to great is not a function of circumstance; it doesn’t take a revolutionary process. “Greatness, it turns out, is largely a matter of conscious choice” (Collins, 2001, p. 11). Making a commitment to community-based services and Employment First practices is also a matter of choice and discipline.

OBJECTIVE: This article will explore the principles of Good to Great and apply them to the transition from traditional day services to community-based employment services.

CONCLUSION: Making a cultural change from good to great requires a lot of effort, but everyone should have the opportunity to have a great, meaningful life, and meaningful work.

1Introduction

More than 50 years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned racial segregation in the workplace, people with disabilities continue to face a culture that largely accepts their segregation and discrimination as a matter of course (Matson, 1990; National Disability Rights Network, 2011). Although there is a pervasive belief that traditional day services, which are largely segregated services, are “good enough”, there is a growing perspective that suggests that denying people with disabilities the opportunities that real work at fair wages would afford them is really a civil rights issue (Wohl, 2014). Despite an expressed desire to support people with disabilities in integrated employment, however, many disability service providers continue to struggle with making the conversion from traditional, center-based day services to community-based approaches that offer supported and customized employment options at businesses within various communities. But there are organizations and communities who have made the commitment to such journeys, thereby initiating a journey from good to great.

Transitioning from traditional day service models for people with disabilities to integrated, community-based supports that allow people to participate in their communities rather than simply be present has the potential for far-reaching impact, beyond the disability services industry, as well. An important implication of changes such as this is that we may begin to see a positive shift in the public’s perception of disability, such as what to “do with” people with disabilities, in a way that will further support the full participation of people with disabilities in their communities. Beginning with Collins’ (2001) notion of “first who ... then what” (p. 41), we hope to get the right people on the bus (i.e. into disability service organizations), putting the industry on a path toward greatness (community-based, individualized, employment-focused services). Finally, in the long-term, we hope to reshape existing paternalistic or negative attitudes and beliefs about people with disabilities and to dissolve the stigma that surrounds them.

2Historical perspectives: Why they matter

In 1990, Dr. Floyd Matson published an historical overview of the “Organized Blind Movement in the U.S.” that described the development of sheltered workshops, as they have appeared for at least the last 125 years in the U.S. Despite the fact that the intended goal of the original sheltered workshops was to teach blind adults basic vocational skills that might afford them the opportunity to become contributing members of their communities, from their well-intentioned outset, sheltered workshops fell short of the expectations of those who originally conceived of them as institutions where people with many types of disabilities (as they later became more widespread) could learn skills that would result in greater integration within their communities and less dependence on others. Despite even these early observations, however, the proliferation of sheltered workshops was marked: In 1979, the Department of Labor reported that sheltered workshops, which numbered a mere 85 in 1948, had increased 35-fold by 1976 to 3,000 (Migliore, 2010).

As far back as the 1960s, there is evidence of a shift in perception of what life could be like for people with disabilities. Ed Roberts, disability advocate and founder of the Independent Living Movement shared his view that it was time for society to develop high expectations for people with disabilities, allowing them to have control over their lives and to engage in meaningful aspects of life and participating in their communities by working. Roberts went on to say that in order to change the old attitudes about people with disabilities, disability would need to be seen as a natural part of the human condition; that people with disabilities would need to participate in their communities, not just be present (MGCDD, 2015). Yet as recently as 2014 it was estimated that “about 450,000 people nationwide work in sheltered workshops or participate in segregated day programs” (Campbell, 2014, para. 28), where they interact primarily, if not exclusively, with others with disabilities. Whether intentional or not, these centers have served to largely exclude people with disabilities from their communities, justified in the name of “job training”.

This history provides a backdrop for the future of services for people with disabilities, a future in which better outcomes are a driving force behind making a shift from sheltered workshops to customized employment supports: higher wages, increased social benefits (friendships with people without disabilities, cultural identity, and integration outside of work), and diminished stigma as a result of emphasis on abilities and productivity (Gottlieb, Myhill, & Blanck, 2010).

3Employment First philosophy: Defining employment today

Employment in this presentation is defined as regular or customized employment where the employee is on the payroll of a company, earning the minimum or prevailing wages, and where inclusion and interaction with co-workers who don’t have disabilities is assured; it may also include self-employment (MN EFC, 2010). In a position paper published by the Association for People Supporting Employment First (APSE), Niemiec, Lavin and Owens (n.d.) describe the fundamental philosophy behind employment first as “expecting, encouraging, providing, creating, and rewarding integrated employment in the workforce as the first and preferred option of youth and adults with disabilities” (p. 2). Proponents of employment first repeatedly emphasize that as a philosophy employment first is not about eliminating service options that already exist, but rather it is about improving typical employment outcomes for people with disabilities. But at its core, employment first has a primary focus of raising expectations.

4Good to Great

In 2001, business consultant, Jim Collins, published Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap ... and Others Don’t. His research included comparisons between several notable companies that made the leap to greatness and similar businesses that did not (most of which are now out of business altogether) and identified the key characteristics that set the two types of companies apart. Although disability service providers may not seem to have much in common with these large, for-profit businesses, the lessons that can be gleaned from Collins’ work are remarkably applicable in this field as well. Collins also provides a definition of greatness that applies well to social sector companies and nonprofit organizations in the monograph, Good to Great and the Social Sectors (2005), encompassing three fundamental characteristics: superior performance, distinctive impact, and lasting endurance. In spite of the fact that superior performance relative to mission may be difficult to quantify in some social sectors, the key is “settling upon a consistent and intelligent method of assessing your output results, and then tracking your trajectory with rigor” (Collins, 2005, p. 8).

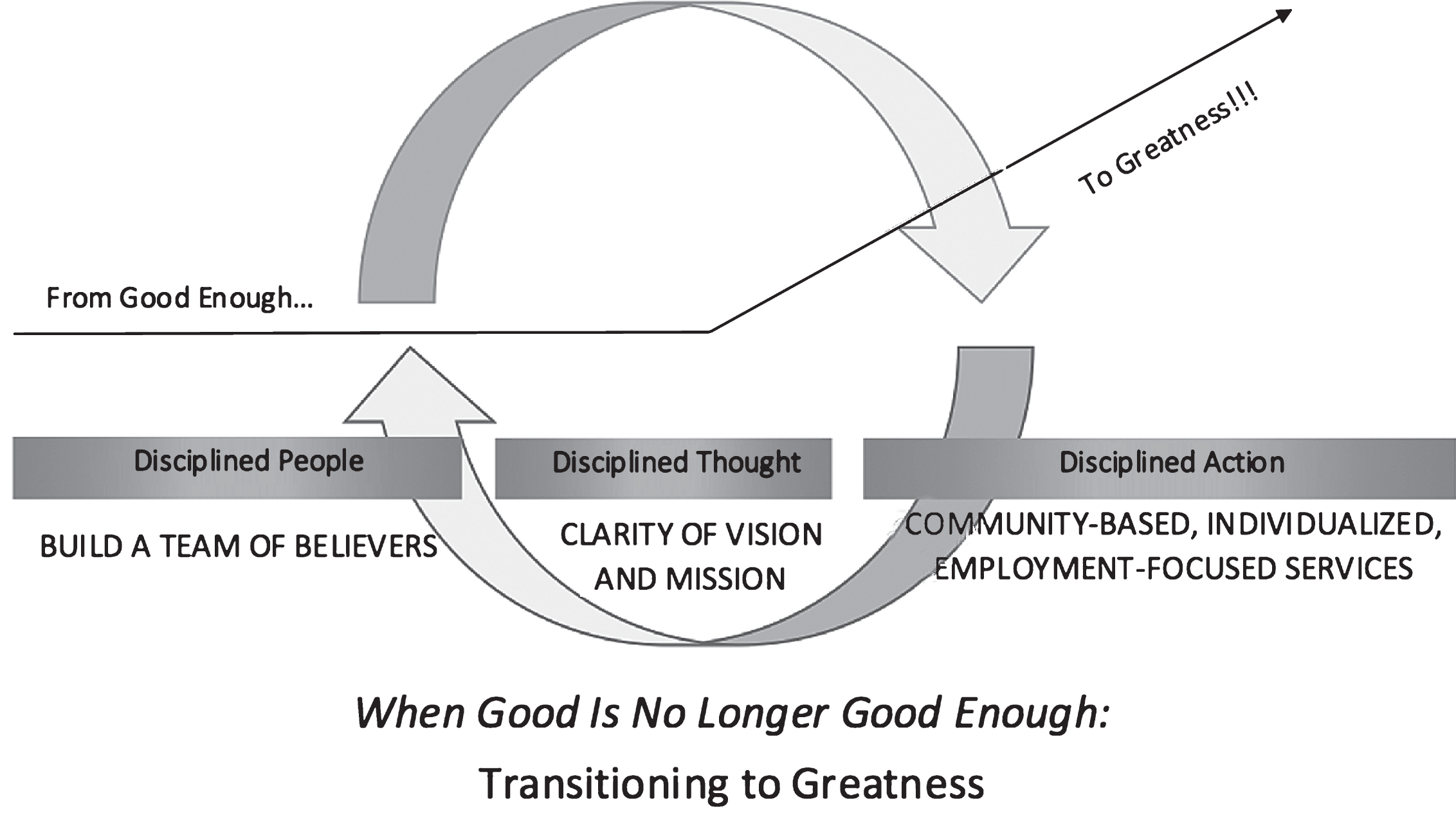

One of the first lessons delineated by Collins (2001) is that “good is the enemy of great” (p. 1). Indeed, being good turns out to be one of the most significant barriers to becoming great, largely because most good businesses assume they are good enough. Collins (2001) also described three areas where discipline is crucial to becoming a great organization: disciplined people, disciplined thought, and disciplined action. The concept of disciplined people includes both “Level 5 Leaders,” who embody an unusual combination of extreme personal humility with intense professional will (p. 21) and a commitment to “getting the right people on the bus” (p. 41) (see Appendix 1 and 2). Disciplined thought includes the practice of confronting the brutal facts, whereby leaders avail themselves of the truth no matter how painful it might be to face it, while simultaneously never losing faith that the organization will prevail in the end (Collins, 2001). Another vital component of disciplined thought is developing a “Hedgehog Concept”, a clear and focused guiding philosophy that comes from a deep understanding of what an organization is deeply passionate about, what it can be the best in the world at, and what drives its resource engine (Collins, 2001; Collins, 2005).

Finally, disciplined action starts with developing a culture of discipline, “the discipline to do whatever it takes to become the best within carefully selected arenas and to seek continual improvement from there. It’s really just that simple. And it’s really just that difficult” (Collins, 2001, p. 128). Collins (2001) emphasized that disciplined action can only come after an organization has disciplined people and practices disciplined thought: “Disciplined action without self-disciplined people is impossible to sustain, and disciplined action without disciplined thought is a recipe for disaster” (p. 126). Not surprisingly, a solid understanding of the concepts discussed in Collins’ publications requires a thorough reading and consideration of his works.

A diagram depicting good to great can be found in Fig. 1.

5Transitioning to community-based services: Beginning the journey from Good to Great

Henry Ford (n.d.) reportedly believed, “If you always do what you’ve always done, then you’ll always get what you’ve always got.” In business – the private, for-profit sectors – being just good enough rather than great can often make the difference between going out of business and enduring year after year. Yet in the social sectors, perhaps especially in public sector organizations and government agencies, this apparent self-correcting mechanism sometimes seems to be missing, or at least malfunctioning. These sectors seem more likely to be populated by organizations that have become complacent. For example, rewarding tenure to the exclusion of performance or funding expensive, traditional services at the expense of innovative – and often more cost-effective – approaches (Myatt, 2011). Making the transition from “good” center-based services to “great” community-based services takes the same type of conscious choice and discipline that Collins (2001) described. First, start small and clear the path – don’t get mired in planning, processing and waiting for the time to be right for change, because that right time will likely never become apparent. Instead, focus on actions by taking some initial steps, and they will lead to insight and the next steps. Making a culture shift like this requires a team to be successful – it is critical to get the right people on the bus. Make a shift to community-based employment one person at a time, a lot of times. Start with people who are on the bus and ready for action (and this includes employees, people with disabilities, and support teams alike). Don’t settle for focusing on people who seem “easy” forever (e.g. people with clearly observable skills and work histories, for example), but do secure some early wins. This will generate excitement and enthusiasm among employees and the people receiving services and will build momentum toward the guiding principles. Rest assured: as with anything, you’ll get better at what you’re doing as you do it.

As with the companies that Collins (2005) studied, “it doesn’t really matter whether you can quantify your results. What matters is that you rigorously assemble evidence – quantitative or qualitative – to track your progress” (p. 7). Another old adage states: “What gets measured gets done” (Peters, 1986, para. 2). Indeed, establishing outcomes and then regularly measuring progress toward them is one of the clearest indicators of leadership’s commitment to a new set of expectations. Share progress with your team with quarterly reports – make it a contest if the team is inspired by competition. For true accountability, make quarterly reports to the Board of Directors or other advisory groups. A few things that might be measured when making a transition to community-based employment services include: number of new jobs secured, job retention, employment rate for people who want to work, average hours per week, average wage per hour.

The brutal reality of making culture change is that it is never easy. In fact, “most companies who set out to make big culture changes fail” (Markidan, 2015). Significant changes such as a shift from traditional day services to community-based employment services can be understandably upsetting for many people. It is likely to lead to an exodus of employees and people receiving services, some by choice and others by suggestion (or even termination). The brutal facts of making this type of transition include countless logistics that may have been taken for granted when there was a “center” to go to, added transportation costs to support community engagement, and increased isolation and stress for employees who no longer have the opportunity to easily connect with co-workers during the course of a work day. Of course there are bright spots along the way, as well, such as newly hired staff who don’t know any other way and simply think the way they’re doing things makes sense.

With all of these challenges, though, why try to be great? If you have to ask the questions, “Why should we try to make our organization great? People seem to be happy, so isn’t the way we have always done things good enough?” then perhaps you’re engaged in the wrong line of work. Because good should never be good enough when great is possible! We should continually strive for what is great. Great for our organizations. Great for our employees. And most importantly, great for the people we support! As Jim Collins (2001) says in the closing paragraph of Good to Great, “It is impossible to have a great life unless it is a meaningful life. And it is very difficult to have a meaningful life without meaningful work” (p. 210), Shouldn’t everyone have the opportunity to have a great life, a meaningful life, and meaningfulwork?

Appendices

Appendix 1.

Who’s on your bus?

Image: © Education World. Used with permission. Retrieved from http://www.educationworld.com/tools_templates/template_SchoolBus-download.doc

Worksheet: All rights reserved © 2015 Cassy Davis and Jolene Thibedeau Boyd.

When Good Is No Longer Good Enough:

Transitioning to Greatness

Add the following to the seats on your bus:

1. Name

2. Seat/role in your organization

Who’s on your bus?

What is value are they adding?

What are the different types of seats on your bus?

Who should fill each of those seats?

Who needs to get off your bus?

Appendix 2.

How to find the “who’s”.

All rights reserved © 2015 Cassy Davis and Jolene Thibedeau Boyd

When Good is no Longer Good Enough: Transitioning to Greatness

How to Find the “Who’s”

Look for someone with...

• Limited or no experience in traditional disability services

∘ Family members can be good

• Social/community activism/connections

• Passion for a cause

∘ Specifics, not just “helping people”

• “Unusual” interests

• Knowledge about how to go about finding a job for themselves

∘ Pay attention to pre-interview research/post-interview follow-up

• Creativity, someone who is excited by possibility

• Ability to answer scenario questions

∘ Job support question, develop a resume/profile question

• Mindset of a champion, not a caretaker

∘ Caring about vs. caring for

• Ability to transition/change

∘ People who need to be told what to do won’t make it

∘ People who can’t “roll with” last minute changes in plans won’t make it

• Initiative, risk-taking, self-motivated

∘ The right people don’t need to be motivated

But also ... . (culture of discipline)

• Can they follow directions?

∘ Familiarity with projects/deadlines (semi-recent grads)

• Can they take accountability?

∘ “Tell me about a time when you made a mistake....”

• Can they use appropriate language?

∘ Do they pick upon the nuances for reference, etc.?

• Did they do their homework prior to the interview?

∘ Mission, values

• Do they know how to find themselves a job?

• Do they provide some balance to the team?

• Do they have a track record of dedication?

∘ Are they willing to work/check e-mails/respond to issues outside of typical day hours?

∘ Do they have the “WIT” (whatever it takes) mentality?

• Establish expectations from the very beginning

∘ Share how they will be measured at the end of introductory/probationary period

∘ Follow through if they don’t meet expectations!

And ... . (culture of creativity)

• Second interviews/opportunity to meet people receiving services & see how they interact

∘ How do they talk to people receiving services?

∘ What ideas do they bring to the table?

• Make this process FUN!

• Encourage new hires to tap into their own community-connections

• Cultivate a culture of creativity

∘ Encourage calculated risk-taking

∘ Allow people to try and fail, as long as they learn from mistakes

• Give people new responsibilities

∘ Plan a staff meeting

∘ Write an article for the employee newsletter

∘ Get involved with advocacy efforts

So what do you look for in an employee?

I look for someone with ... .

1. ____________________________________

2. ____________________________________

3. ____________________________________

4. ____________________________________

5. ____________________________________

References

1 | Campbell M. ((2014) ). New federal rules could close sheltered workshops for people with disabilities [Electronic version]. The Kansas City Star. Retrieved from http://www.kansascity.com/news/government-politics/article1297132.html. |

2 | Collins J. ((2001) ). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap ... and others don’t. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. |

3 | Collins J. ((2005) ), Good to great and the social s: A monograph to accompany good to great. Boulder, CO: Jim Collins. |

4 | Ford, H. (n.d.) Online quotation retrieved from http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/904186-if-you-always-do-what-you-ve-always-done-you-ll-always. |

5 | Gottlieb A. , Myhill W. N. , Blanck P. ((2010) ). Employment of people with disabilities. In Stone J.H., Blouin M. (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation. Retrieved from http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/encyclopedia/en/article/123/. |

6 | Markidan L. ((2015) ). How to make company culture changes that stick. Retrieved from https://www.groovehq.com/support/company-culture-change. |

7 | Matson F. ((1990) ). Walking alone and marching together [Electronic version]. National Federation of the Blind. Retrieved from https://nfb.org/images/nfb/publications/books/books1/wamtc.htm. |

8 | Migliore A. ((2010) ). Sheltered workshops. In Stone J.H., Blouin M. (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation. Retrieved from http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/encyclopedia/en/article/136/. |

9 | Minnesota Employment First Coalition (MN EFC). ((2010) ). The Minnesota third annual employment first summit report: A new hope [Electronic version]. Retrieved from http://www.mnapse.org/#!summit-iii/cj5l. |

10 | Minnesota Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities (MGCDD). ((2015) ). The independent living movement 1970-present: Ed Roberts: The birth of independent living [Online video]. Parallels in Time: A History of Developmental Disabilities. Available from http://mn.gov/mnddc//parallels/six/6b/6b_html/6b_13vid.html. |

11 | Myatt M. ((2011) ). Five reasons tenure kills culture [Web log]. Retrieved from http://www.n2growth.com/blog/loyalty-tenure/. |

12 | National Disability Rights Network ((2011) ). Segregated and Exploited: The Failure of the Disability Service System to Provide Quality Work. Washington DC: National Disability Rights Network. |

13 | Niemiec B., Lavin D., & Owens L. (n.d.). Establishing a National Employment First Agenda [Electronic version]. Retrieved from http://www.apse.org/wp-content/uploads/docs/Revised%20Employment%20First%20paper%20709%5B1%5D.pdf. |

14 | Peters T. ((1986) ). What gets measured gets done. Tribune Media Services, Inc. Retrieved from http://tompeters.com/columns/what-gets-measured-gets-done/. |

15 | Wohl A. ((2014) ). Poverty, employment, and disability: The next great civil rights battle. Human Rights Magazine, 40: (3). Retrieved from http://www.americanbar.org/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/2014_vol_40/vol_40_no_3_poverty/poverty_employment_disability.html. |

Figures and Tables

Fig.1

From good enough to greatness.