Exploring social networks, employment and self-determination outcomes of graduates from a postsecondary program for young adults with an intellectual disability

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Data on graduates’ development and employment outcomes from postsecondary programs for young adults with an Intellectual Disability (ID) continue to increase and provide information on program efficacy and areas for growth.

OBJECTIVE:

This study explored the development of graduates’ social networks, employment outcomes, and self-determination a year after graduating from an inclusive postsecondary program.

METHODS:

The social networks, employment outcomes, and evidence of self-determination in a combined cohort of graduates (n = 6) were analyzed using social network analysis.

RESULTS:

All graduates except one were employed a year later. Half displayed smaller networks consisting of family members and new work ties. Only two graduates displayed large networks because of opportunities for socialization. In the absence of employment, students also fall back on familiar supports. Most parents were involved in graduates’ employment decisions, thereby curbing graduates’ expression of self-determination.

CONCLUSIONS:

Family supports are prominent in graduates’ networks and play a crucial role in employment choices. They act as constant protective and social-emotional supports ensuring graduates’ access to benefits and maintenance of well-being. Employment skills valued by employers and further opportunities to develop students’ social networks while in the PSE program needs to be a focus going forward.

1Introduction

Since its introduction, the Model Comprehensive Transition and Postsecondary Programs for Students with Intellectual Disabilities (TPSID) have funded 52 postsecondary (PSE) programs in higher learning institutions in the United States. These PSE programs offer students with an Intellectual Disability (ID) academic enrichment and the opportunity to have an inclusive college experience to prepare them for eventual gainful employment and independent living (U. S. Department of Education, n.d.). Work and independent living are “important factors” for “increasing the quality of life for individuals with an ID” (Ryan et al., 2019). TPSID programs focus on helping students increase their chances of securing fulfilling paid employment in their communities through outreach and engagement, strong partnerships, increased student visibility on campus, and career services connections (Domin et al., 2020). Additionally, these programs focus on developing skills such as self-determination and self-advocacy as requirements for independent living. Wehmeyer (2005) stressed that individuals with disabilities who learn and apply self-determination skills are more apt to live independently than those with fewer self-determination skills.

Another crucial aspect that TPSID programs focus on is socialization, an area that students with an ID typically need more support as they often have limited social circles compared to individuals without disabilities (Wilson et al., 2016). Social networks of those with an ID are generally composed of family members, service providers, and peers with disabilities (Amado et al., 2013; Gilmore & Cuskelly, 2014; Eisenman et al., 2013). Factors contributing to these limited circles include beliefs about the person and the individual’s self-perception (Devlieger & Trach, 1999), fewer opportunities to interact with others (Asselt-Goverts et al., 2015; Bigby, 2008), and protective family circles (Llewellyn & McConnell, 2002). Behavior and communication difficulties also limit individuals’ social circles (Forrester-Jones et al., 2006), which is why programs also focus on developing students’ social skills as these contribute to better socialization and employment outcomes (Eisenman et al., 2013; Bouck, 2014; Agran et al., 2016). Collaborations and partnerships developed through PSE programs provide an avenue for students to build their social circles and facilitate changed mindsets about inclusion, ultimately leading to new opportunities and improved transition outcomes for students with an ID (Folk et al., 2012).

1.1Social Network Analysis (SNA) studies in PSE programs

Eisenman et al. (2013) explored how students’ relationships could be employment connectors as they developed networks that included possible strong ties and weak ties. Strong ties or bonding ties are defined as family, close friends, or individuals who belong to the same social circle. In contrast, weak ties or bridging ties are made up of informal relationships or connections established with individuals in other social circles who may provide access to “new resources and social positions” (McCarty et al., 2019). A network in Eisenman et al. (2013) was defined as relationships made up of family, caregivers, authority figures such as teachers or healthcare professionals, peers, and incidental/group. Incidental/group was further defined as those individuals that students met in passing or with whom they had some affiliation.

Two data collection forms were used to collect information from students. The Network Activity Form asked students to identify the different activities they had been involved in and were coded according to location (high school, community, home, campus, other), frequency in which the activity occurred (weekly, monthly, occasionally, annually), purpose of the activity (social recreational, academic, work), and the level of integration within the activity (integrated, hybrid, specialized). An integrated activity was one that included those with and without disabilities. A hybrid activity was defined as one specifically designed for an individual such as a job shadowing opportunity. A specialized activity was one that only included individuals with disabilities. The purpose of the Network Activity Form was to first identify a list of activities that would eventually correspond to a list of names generated using a Network People Form. The Network People Form, as a second data collection form, asked students to identify individuals within those activities that was noted earlier. People identified were coded according to relation, sex, time known (a year, few years or less than four years, longtime or more than five years, or just met in the PSE program), the level of closeness (very close, sort of close or not close, mix, unable to decide), and direction in terms of support (student gives help, equal help, student receives help, mix, unable to decide). Students were asked prompts such as: You listed activity A in your application form as something you did before starting this program. Tell me a little bit more about Activity A. Where did you do Activity A? How often did you do it? Do you still do Activity A? Why do you do Activity A? Is this activity especially for people with disabilities? Who does Activity A with you? How is this person connected to you? How long have you known this person? Do you help this person or does this person help you? How do you help him/her, or how are you helped? Or is it more like you help each other about the same?

Student networks observed by Eisenman et al. (2013) over two timepoints found that although students came into the program with large family networks, most of these were replaced by peer networks by the second time point. The PSE program experience became an opportunity for students to connect with various individuals outside their usual circles who could also be employment connectors. Eisenman et al. (2013) made recommendations for further research that included the longitudinal analysis of students’ social networks to observe network growth and employment outcomes post-program to determine program success.

Based on this recommendation, the present PSE program conducted a mixed methods longitudinal SNA study that followed a cohort of students before starting the program to the end of the program, observing students’ network development (Spencer et al., 2021). Spencer et al. (2021) also found that students started off the program with small and limited networks made up of family, close friends, and caregiver ties. However, by the end of one year in the program, these networks grew to include a large number of peers that outnumbered family ties. Most former peer and caregiver ties were also replaced by new peer and authority ties formed during the PSE experience. Some of these PSE program peer ties remained a part of students’ networks by the end of their second/last year in the program. These were considered close friendships formed while in the PSE program. Family ties also re-emerged to be a prominent part of students’ networks as they prepared to graduate. Although student networks in the final year were smaller than what they were at the end of their first year in the program, these continued to represent ties formed in the program as significant connections that came into existence through activities that students were involved on campus and in the PSE program.

A further observation from the Spencer study was the distinct clusters that were obvious in most students’ networks. These distinct clusters were either made up of family ties or PSE program ties consisting of peers and authority figure connections formed in the program. These were distinct because they were not connected to each other or other isolated ties in the networks. Prompts such as those that were used in Eisenman et al. (2013) were also used in the present program to generate responses. For example: You said that you spend a lot of time doing Activity B. Who do you do Activity B with? How do you know this person or these people? How often does this person or these people do Activity B with you?

The formation of clusters was attributed to the limited opportunities available to this population locally to interact and socialize. This situation led to students doing activities with connections in each distinct cluster but not having shared activities between clusters. The most prominent clusters in each student’s network were the PSE and family. Uncertainty of what students’ networks would look like after graduation and how these networks will reflect employment outcomes resulted in the decision by Spencer et al. (2021) to extend the longitudinal study assessing graduates’ social networks a year post-program.

1.2Employment outcome studies in PSE programs

Employment outcomes for those with an ID have historically remained low (Siperstein et al., 2013; Butterworth et al., 2013). However, the employment outcomes for individuals with an ID who have PSE education appear to be better than those without a PSE education. A growing number of studies explore the employment outcomes and the personal development of graduates from a PSE program (Migliore et al., 2009; Moore & Shelling, 2015; Miller et al., 2016; Green et al., 2016; Southward & Kyzar, 2017; Ryan et al., 2019). PSE graduates’ had competitive employment rates with wages at or above minimum wage (Grigal et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2013; Carnevale & Derochers, 2003). Papay et al. (2017) found that 61% of TPSID graduates from 2015-2016 were employed a year post-program. Smith et al. (2018) report that youth who received PSE services as part of their Individualized Plan of Employment (IPE) through their state’s Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) agency had higher employment rates and earned 51% more than those who did not receive PSE services. Additionally, those who did access PSE services but did not increase their educational attainment also acquired 44% higher wages than those who did not access PSE services. In comparison, those who made educational attainment gains were 14% more likely to exit PSE services with an integrated employment opportunity.

Grigal et al. (2019) report that the employment outcomes for those with an ID who attend TPSIDs were better than the national data, with 36.7% of those exiting a PSE program having paid employment. Natural partnerships with key strategic partners such as VR agencies and existing institutional supports also resulted in better employment outcomes for students with an ID (Raynor et al., 2016). Although, there were also VR agencies in some states that continue to be barriers to students enrolled in TPSIDs by regarding them ineligible for services (Lee et al., 2019; Grigal et al., 2018). With increasing evidence that a PSE experience can lead to better employment outcomes for those with an ID, Grigal et al. (2019) stress that more students may consider these options a pathway to employment opportunities over time.

1.3The importance of self-determination in the lives of individuals with an ID

Given the success of PSE programs, examination of elements of such programs that support employment and independent living are important. One such aspect is the development of a sense of self-determination. The PSE program where this work was done, as well as many others, makes strong use of peer mentors and focuses on inclusive experiences that connect students to contexts where they have choices and can make decisions. Spencer et al. (2021) observed that social supports in the form of peer mentors especially, in students’ networks while they were in the program, aided them in building confidence, social skills and learning how to interact with others. This was reflected in the larger number of relationships they developed in the program and their openness to participate in various new activities on campus. The availability or lack of such supports outside of family members’ post-program, therefore, could determine how graduates respond to new situations and experiences. Studying social networks post program could help determine whether the sense of support for self-determination that was facilitated in the program continues as program completers move out into new contexts or return to their family home.

The importance of self-determination in the lives of individuals with an ID is well studied. Wehmeyer and Metzler (1995) argue for the need to focus on self-determination in these individuals precisely because they lack opportunities to make decisions and choices independently and assume control over their lives. An individual with an ID displays self-determination through “choice and decision making, problem-solving, goal-setting, and attainment of skills; internal locus of control orientations; positive self-efficacy and outcome efficacy; and self-knowledge and understanding” (Wehmeyer et al., 1996). However, autonomy to act according to one’s desires or preferences, independent of external influences such as family, continues to be a barrier for individuals with an ID (Sullivan et al., 2016; Frielink et al., 2017). At the same time, families continue to be essential mediators in the lives of those with an ID as they provide supports needed to obtain and maintain employment (Donnelly et al., 2010).

Curryer et al. (2015) contend that although some families understand the need to support self-determination in their young person with an ID, others view their role as protective, believing that only they can make the best decisions. Employment for individuals with an ID fulfills “a socially valuable role” and is more than just a means to an income. Akkerman et al. (2016), therefore, advocate for greater insight and involvement of individuals with an ID in employment or career-related matters, as an expression of their self-determination.

Deci and Ryan (2000) argue that the support of three basic psychological needs can help facilitate self-determination. They postulate that autonomy (the ability to make choices), competence (the ability to succeed with optimally challenging activities), and relatedness impact peoples’ sense of self-determination. Social networks that support these basic needs provide students with ID opportunities to develop a better sense of self-determination. Building and maintaining social networks that go beyond core family and segregated contexts is a sign of self-determination and we believe is likely to play a role in maintaining gainful integrated employment. For example, Deci and Ryan’s model predicts that building relationships in the workplace that support a sense of relatedness and competence should increase self-determination. While there is no guarantee that the networks formed will necessarily provide such support, the opportunity for such supportive networks is greater once a student has moved out of a more sheltered life where there is sometimes less opportunity to make choices and demonstrate competence.

1.4Exploring social networks and employment outcomes of graduates in the present PSE

This present PSE program was one of 25 programs that received TPSID funding for the period 2015–2020. It is located in the Southeast region of the United States on the main campus of a mid-sized public university in a suburban area of a midsize city with an undergraduate student population of 10,988. It was recently designated a Comprehensive Transition and Postsecondary (CTP) program, a designation that allows students to apply for federal financial aid. This two-year non-degree certificate program is designed for students who need extra support to succeed in the community. It is currently serving its fourth cohort of students and has graduated three cohorts. Targeted skills to help students meet their future goals include independent living, social, employment, and self-determination. Students predominantly attend inclusive classes with other college students, as well as a few specialized courses. Peer mentors are an essential component of the program and act as natural supports on and off-campus to help foster independence and learning, and increase students’ sense of belonging (Kern et al., 2018). Mentors support students during employment opportunities on and off-campus by modeling appropriate actions and scaffolding them in various tasks. Mentors also help students develop their social skills by including them in opportunities to socialize on and off campus. They introduce students to their circle of friends and activities that they are involved in, such as Greek Life, sports, and various campus organizations.

PSE programs continue to collect follow-up data on their graduates’ employment and developmental outcomes to determine the efficacy of such programs in helping students with an ID achieve gainful employment and independent living. This study aims to add to existing data by using social network analysis as a window into graduates’ lives to provide insights into their social networks, working experience, and degree of self-determination. The following research questions guided this study:

1) What do the social networks of students who graduate from a PSE program look like a year post-program?

2) What aspects of graduates’ social networks post-program contribute to positive employment outcomes and do graduates’ networks post-program encourage them to express self-determination in employment choice and decision making?

2Method

2.1Participants

The demographic information for graduates and their parents’/guardians’ are provided in Table 1. All parent and graduate pairs were assigned matching letters to represent participants in this study. For example, Graduate A and Parent A, Graduate B and Parent B, etc.

Table 1

Demographics of graduates’ and parents/guardians at T4

| Demographics | Graduates | Parents/guardians |

| n = 6 | n = 6 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4 | |

| Female | 2 | 6 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 5 | 5 |

| African American | 1 | 1 |

2.2Design

A mixed methods design within a personal network research design (PNRD) was used in this study. A PNRD defines an ego’s network from their perspective; hence it is called ego network analysis. Ego network analysis focuses on an ego or individual’s network from their perspective. In this case, each graduate is an ego. An ego’s connection is known as an alter (McCarty et al., 2019; Borgatti et al., 2018). McCarty et al. (2019) state that the goal of PNRD is “to study the effects of the set of relationships that surround an individual, regardless of the context from which they are drawn.” A limitation of PNRD is the inability to check the accuracy of the data reported by an ego. The mere identification of a tie or relationship may not necessarily mean that it is reciprocal (Halgin & Borgatti, 2012). The level of closeness with others is mostly an issue for young people with an ID. They are often unable to discern the depth of closeness in their relationships (Eisenman et al., 2013). Therefore, in this PSE, the study was modified to include parents/guardians’ perspectives of their student’s network. A comparison of network data perspectives would give a better picture of students’ networks and help with a more accurate representation of networks.

Although SNA is often considered a quantitative technique, it has gained recognition as mixed methods that allow for the combination of quantitative and qualitative data to generate meaningful research (Froeh, in press; Onwuegbuzie & Hitchcock, 2015). Onwuegbuzie and Hitchcock (2015) refer to this as a quantitative dominant crossover analysis. Hollstein (2011) argues that qualitative data and analysis facilitates SNA by “explicating the problem of agency, linkages between network structures and network actors, as well as questions relating to the constitution and dynamics of social networks.” Therefore, in the context of this study, a quantitative dominant concurrent mixed methods design for triangulation is used to “seek convergence, correspondence and corroboration of results from different methods” (Johnson & Christensen, 2020). We merge participants’ responses with quantitative data to better picture students/graduates’ experiences pre, during, and post-PSE from both groups’ perspectives.

At the end of the PSE program at T3, students and parents were asked if they would be willing to continue this study a year later. All indicated that they would be willing to participate. Approximately ten months later, graduates and their families were contacted to remind them of the continuation of the SNA study. Participants were emailed consent forms that were signed and returned the same way. All interviews were scheduled to be held on campus. However, due to COVID-19, it was only possible to conduct two interviews with graduates and their parents. All remaining interviews with graduates and their parents/guardians were conducted over the phone. All participants also provided permission to have interviews audio recorded. All interviews were timed to not exceed an hour. While the campus interviews took almost an hour, the phone interviews averaged around 40 minutes although the same questions were asked of participants.

Quantitative data analysis in SNA examined graduates’ network size, composition, and density. Network size is simply the number of alters in an ego’s network. Network composition identifies the nature of the relationship between ego and alters, i.e., peer, family, authority, caregiver, or incidental/group. Density is defined as the percentage of all possible ties in the network, or “the extent to which alters are connected” (Eisenman et al., 2013). An ego with 0 density only has connections with each alter, but the alters themselves are not connected. An ego with a density closer to 1 has shared activities with alters from different groups. Additionally, sociograms or network diagrams that reflect each graduate’s network was generated to provide a visual representation of the ego’s social network. All quantitative SNA data was organized, analyzed, and produced using Excel and SNA software (E-Net, UCINET, and NetDraw) from Analytic Technologies (Borgatti, 2006; Borgatti, 2002; Borgatti et al., 2002).

Qualitative data comprise participant quotes reported verbatim or paraphrased where necessary to reflect both groups’ emic or insider perspectives, thereby allowing the “consideration of questions and issues” important to participants (Johnson & Christensen, 2020). All qualitative data were transcribed by the first author and sorted using a role-ordered matrix that distinguished between graduates and their parents’ responses. Data were coded for emotions that provided insights into participants’ perspectives, values, attitudes, and beliefs that reflected graduates’ personal network development, employment outcomes, and growth in self-determination post-program (Miles et al., 2014). From this data, broad themes that addressed the research questions were identified using a general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006). These themes were reviewed by the second author and further developed through discussions to confirm findings.

2.3Instrument and data collection

Permission was obtained from Eisenman et al. (2013) to adopt the interview protocol and data collection forms used in their study and adapt it to our purpose. The adopted semi-structured interview protocol was modified to reflect this PSE’s specifics, and local activities and locations familiar to participants. A further modification was the inclusion of a beginning open-ended interview question at each stage of the SNA study (T1, T2, T3, and T4), to facilitate qualitative responses on participants expectations of the PSE, experiences in the PSE, realizations from the PSE, and post-PSE observations and experiences. Prompts used to collect SNA data were the same as those used in Eisenman et al. (2013), as described earlier. This modified protocol was used as a pilot in this program. We hope that its continued use with future cohorts in the program will only strengthen its validity and reliability.

T1 network data was collected before the participants began the program and reflected their network ties in the one year preceding the PSE program. Network data at T2 revealed participants’ ties during their first year in the PSE program, and interviews were conducted at the end of their first year in the program. Network data at T3 reflected participants’ ties in the second/final year of the PSE program, and interviews were conducted at the end of the program. Data collected a year post graduation was termed Time 4 (T4) data and was compared, where necessary, against previously collected data at baseline/Time 1 (T1), Time 2 (T2), and Time 3 (T3) as reported in Spencer et al. (2020). Time 4 data is also the subject of this article.

This protocol was also replicated for use with parents/guardians to identify what type of activities the former PSE students were involved in one year after graduating. All interviews with graduates and their parents/guardians’ were conducted separately to avoid participants influencing each other’s responses. All interviews were also conducted by the first author.

Activity data was recorded on a Network Activities form. The activity’s location, frequency, purpose, and type of integration were recorded on the same form. Integration was coded as Specialized, Inclusive, and Hybrid. The coding used for activity’s location, frequency, purpose and type of integration was the same as that used in Eisenman et al. (2013). A modification to the Network Activities form introduced at T4 for graduates and parents included identifying who introduced the graduate to any new activity, with a specific interest in any new employment activity that graduates participated in one-year post-PSE. The identification of the introduction source was to specifically explore the expression of self-determination in graduates’ employment choices. At T4, we included prompts such as: Who introduced you (your adult child) to this job? How did you (he/she get) this job? Did anyone help you (him/her) to get this job? By including these prompts as part of the SNA protocol, we were also able to generate a conversation with graduates and their parents about graduates’ employment choices. Individuals who introduced the activity to the graduate were coded as Self/ego, Family, Peer, or Other. At T4, an Alter Matrix Form was also included to provide the researchers with the ability to confirm if alters identified in a particular activity knew each other and truly belonged to that social circle. Participants were asked to provide a confirmation of alter connections after identifying the alters within each activity. If they were uncertain, the interviewer made a note of this on the form.

Graduates’ and parents/guardians’ identified individuals or alters within those activities that the graduates had connections to, and these were recorded on a Network People form. Alters identified were coded as Family, Authority, Peer, Caregiver, or Incidental/group. Additionally, alters’ sex, length of the relationship, closeness with the alters, and participants’ perception of the direction of support in the relationship were identified.

3Results

SNA quantitative data that addresses the development of graduates’ social networks is presented along with the theme of familiar supports derived from the interviews to answer our first research question. We also included a question in our SNA protocol to answer our second research question. This question on who introduced graduates to a job, together with qualitative data generated from asking this question, helped us explore what aspects of social network development contributes to positive or negative employment outcomes. Through these qualitative responses, we also look to see if social network development can inform us of graduates’ ability to assert self-determination in employment choice and decision making.

3.1Research question one: Addressing the social networks of graduates post-PSE

The quantitative data presented here best addresses our first research question on what graduates’ social networks look like from their perspective and their parents’ perspective at T4. Table 2 provides information on network size, density, and relationship composition from both perspectives. A year post-PSE, this cohort of graduates had an average of 15 people in their network with family members comprising 40% of their network. It should be noted here that the higher average in terms of network size is as a result of Graduate A, Graduate D, and Graduate F’s reporting of large networks. Peers constituting co-workers and new and old friends made up an average of 47% of graduates’ network. Authority figures such as supervisors and managers at job sites made up an average of 13% of graduates’ network. An individual observation of graduates’ relationship composition from both perspectives shows that family ties overwhelm peer ties in Graduate B, Graduate C, and Graduate E’s network representation. These graduates also had smaller networks than Graduates A, D, and F. In contrast, an individual observation of Graduates A, D, and F’s representation from both perspectives show that peer ties overwhelm family ties. Therefore, smaller networks from both perspectives were associated with more family ties than larger networks that consisted of more peer ties.

Table 2

Characteristics of graduates’ network size, density and relationships at T4 from graduates’ and parents perspective

| Basic | Relationship | |||||||||||

| Size | Density | Family (%) | Authority (%) | Peer (%) | Incidental (%) | |||||||

| ID | Graduate | Parent | Graduate | Parent | Graduate | Parent | Graduate | Parent | Graduate | Parent | Graduate | Parent |

| A | 20 | 17 | 0.15 | 0.191 | 15 | 5.9 | 10 | 23.5 | 75 | 70.6 | 0 | 0 |

| B | 10 | 6 | 0.23 | 0.5 | 50 | 83.3 | 10 | 0 | 40 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 8 | 7 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 62.5 | 71.4 | 12.5 | 0 | 25 | 28.6 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 21 | 23 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 33.3 | 26.1 | 9.5 | 17.4 | 57.1 | 47.8 | 0 | 8.7 |

| E | 9 | 9 | 0.24 | 0.278 | 66.7 | 55.6 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 24 | 13 | 0.20 | 0.192 | 12.5 | 23.1 | 25 | 15.4 | 62.5 | 53.8 | 0 | 7.7 |

| Mean | 15.3 | 12.5 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 40 | 44.2 | 13 | 11.2 | 47 | 41.8 | 0 | 2.7 |

Parents reported an average network size of 12 people in their graduates’ network. Of these, 44% comprised family ties, and 11% made up authority ties. On average, peers, old and new, made up less than half of their graduates’ network. As Eisenman et al. (2013) point out, the size, density, and composition of networks can vary independently. Graduate A and Graduate D appear to have more extensive networks from both perspectives. However, they also have lower density scores than Graduates B, C, and E. The former had lower density scores because of many different activities that they were involved in with individuals who were not all connected. The latter reported higher density scores because of smaller networks with ties who knew each other and connected in some of the same activities. Graduate F appeared to have the largest network size in this combined cohort. Graduate F’s network representation was also larger than Parent F’s representation. A closer look at Graduate F’s network, however, indicates that a large number of peer ties (62.5%) and authority ties (25%) are from a long involvement in an organization for individuals with an ID, as was reported in the PSE program at previous timepoints, and past connections made in the PSE (Spencer et al., 2021). Although Parent F reported a smaller network than Graduate F, some of the same peer ties (53.3%) and authority ties (15.4%) from Graduate F’s current involvement in the same organization for individuals with an ID and the past PSE experience were identified.

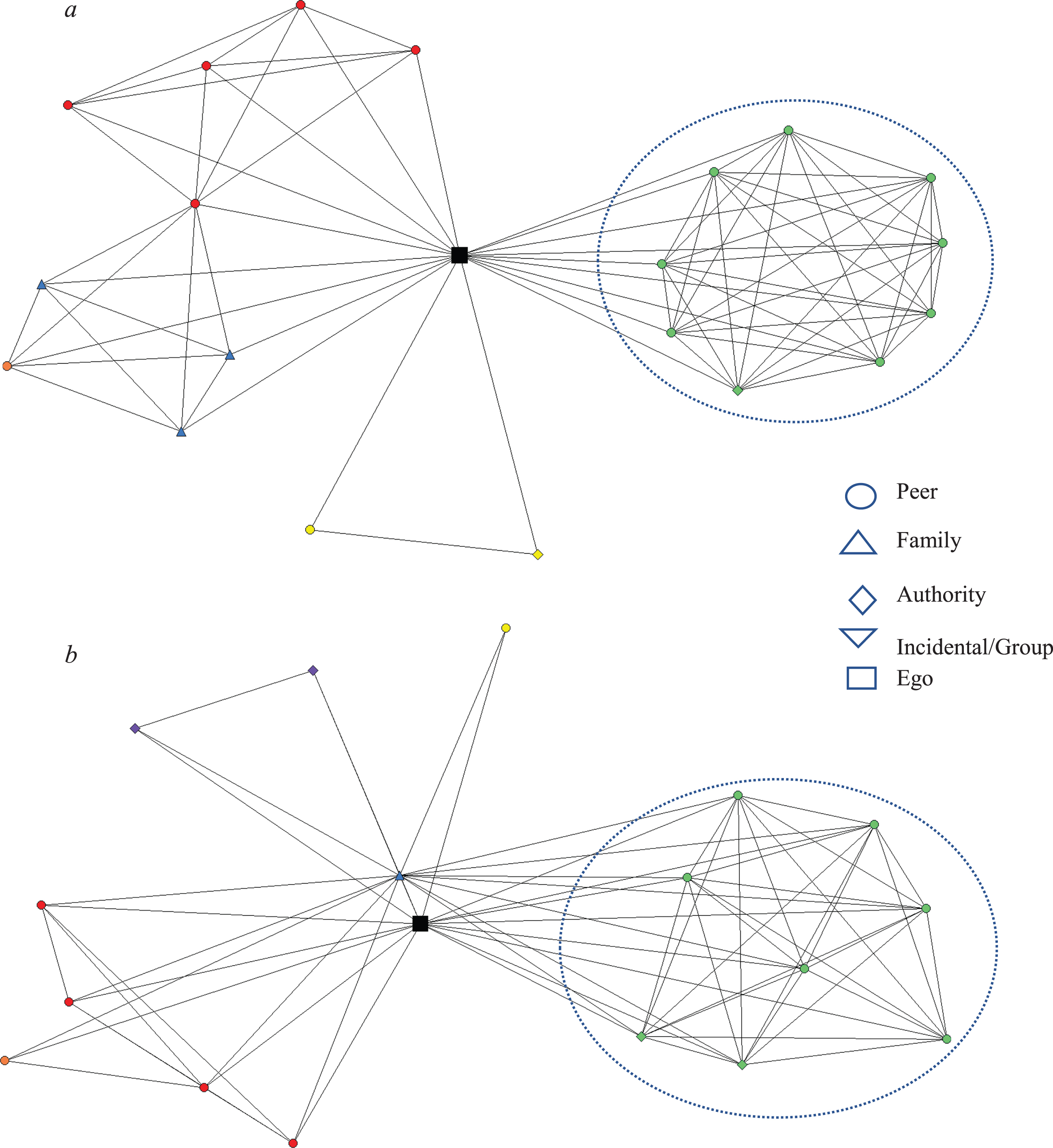

Figure 1 presents as an example, Graduate A’s network from both perspectives. The different shapes used in sociograms are called nodes, and these represent different roles. In these figures, the ego is represented in the center and appears as a black square node. Up triangles represent family nodes. Diamonds represent authority nodes. Circles represent peer nodes. Down triangles represent incidental/group nodes.

Fig. 1

a) Graduate A’s ego network from the graduate’s perspective. b) Graduate A’s ego network from the parent’s perspective.

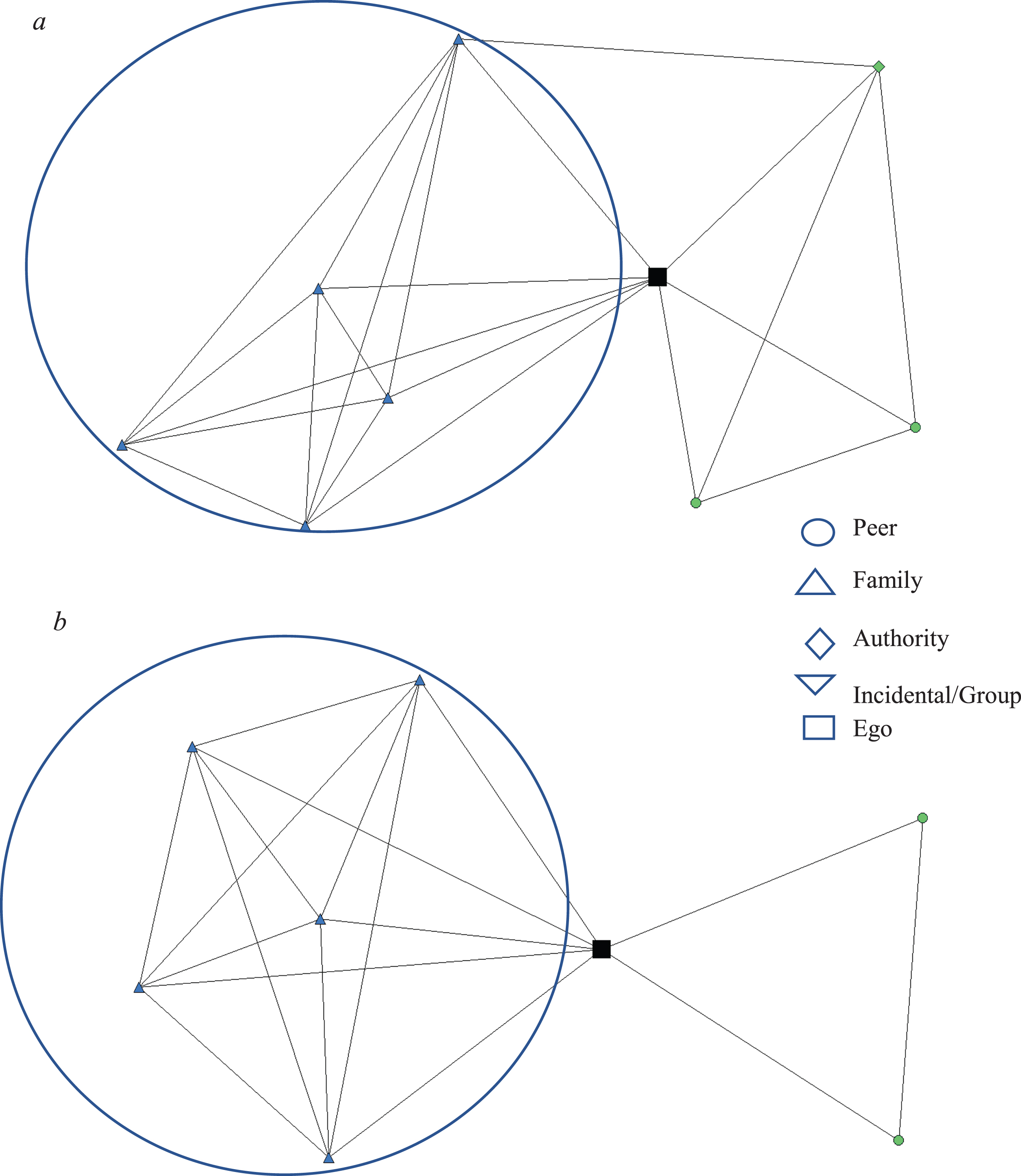

Additionally, the nodes are color-coded here to indicate different activities. Blue nodes indicate a family activity. Socio-recreational activities are represented by red and orange nodes. Green and yellow nodes indicate present and past workplace activities. Both Graduate A and Parent A represent present workplace ties (in green and within a dotted line circle) as the most dominant in the network in terms of size. Occasionally, parents do describe other activities that they consider an essential part of their graduate’s network. In Fig. 1b, the purple nodes indicate two authority figures the ego interacts with regularly in another frequent social-recreational activity. In contrast, Graduate C’s network presented in Fig. 2 from both perspectives shows a network dominated by family ties (in blue and within a solid line circle). Present workplace ties are fewer in comparison (in green).

Fig. 2

a) Graduate C’s ego network from the graduate’s perspective. b) Graduate C’s ego network from the parent’s perspective.

To better understand the quality of graduates’ networks, a tie churn analysis was performed to capture the network change between T3 and T4 from both perspectives to show new ties, kept ties, and lost ties in a graduate’s network (Halgin & Borgatti, 2012). A tie churn analysis considers the actual number of new ties in an ego’s network compared to the last timepoint. The size of an ego’s network alone does not provide this picture. For example, a network at two timepoints may have ten alters in terms of size, but these alters may be completely different between both timepoints.

Table 3 provides data on the change in graduates’ network ties from their perspective. Graduates A, D, and F appear to have grown their networks since graduating from the program. In contrast, the networks of Graduates B, C, and E appear to have shrunk since graduation. However, a closer look at some of these networks shows that seemingly new ties sometimes included old ties evident in a graduate’s network from earlier timepoints in the PSE program, as reported in Spencer et al. (2021). These ties were not reported at T3, therefore, excluding them from the tie churn analysis. For example, two of Graduate D’s new ties were family ties reported at T1 and T2. A peer tie at T2 was not declared at T3 but reappeared at T4. Graduate F reported two new ties at T4 that were previously reported at T1 and T2. A closer analysis of graduates’ new ties by cross-checking data collected on T4 data collection forms revealed that 50% of Graduate A’s new ties were from work, and 100% of Graduate B and Graduate C’s new ties were work ties. Work ties that formed new ties for Graduate D and Graduate E were smaller at 7.1% and 20%. None of Graduate F’s new ties were work ties. In terms of kept ties, all reported that family members stayed a significant part of their network. In the case of Graduates B, C, and E, family ties formed more than half of their network’s kept ties. The tie churn analysis from graduates’ perspective showed that new ties post-program were mostly made up of work ties. In the absence of employment as a significant activity in a graduate’s network, such as in the case of Graduate F, old ties and activities may reappear in a graduate’s network.

Table 3

Graduates’ tie churn between T3 and T4 from their perspective

| ID | T3 size | T4 size | New ties | Lost ties | Kept ties |

| A | 9 | 20 | 18 | 7 | 2 |

| B | 23 | 10 | 1 | 14 | 9 |

| C | 16 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 5 |

| D | 18 | 21 | 14 | 11 | 7 |

| E | 17 | 9 | 5 | 13 | 4 |

| F | 22 | 24 | 11 | 9 | 13 |

Table 4 provides data from the tie churn analysis between T3 and T4 from the parents/guardians’ perspective. Graduates A and D appear to, again, have the largest number of new ties after graduation. Co-workers made up a significant part of Graduate A’s new ties, and many of Graduate A’s family and peers made up Graduate D’s new ties, apart from Graduate D’s own connections with co-workers. Parents B and C report that more than half of their graduate’s kept ties were family ties. Graduate B’s only new tie also appeared to be a family tie reported at T1 but not at T3.

Table 4

Graduates’ tie churn between T3 and T4 from parents’ perspective

| ID | T3 size | T4 size | New ties | Lost ties | Kept ties |

| A | 8 | 17 | 16 | 7 | 1 |

| B | 5 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| C | 16 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 4 |

| D | 14 | 23 | 20 | 11 | 3 |

| E | 27 | 9 | 4 | 22 | 5 |

| F | 13 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

Similarly, Graduate F’s new ties consisted of individuals with an ID that was reported at T1 but not at T3. Parent A, Parent C, and Parent E reported that many of their graduate’s new ties were from work at 56.25%, 66%, and 50%, respectively. Parent B and Parent F reported that none of their graduate’s new ties were from work. Parent B’s reporting was inconsistent with Graduate B’s reporting, where all new ties were identified as ties from work. In this instance, Parent B was not very familiar with Graduate B’s network, especially when it came to work-related ties. However, parent F’s reporting was consistent with Graduate F’s reporting, where none of the new ties were work-related ties. The tie churn analysis from the parents/guardians’ perspective also showed that new ties in graduates’ networks were associated with work. In the absence of work, family, and old ties from previous activities may reappear in the network.

3.1.1Familiar supports

The theme of familiar supports derived from the interviews bolsters the SNA quantitative data in addressing our first research question of what graduates’ networks look like post-PSE. Apart from Graduate A and Graduate D, who maintained large networks of friends because of their post-PSE activities, others continue to display smaller bonded networks made up of familiar social-emotional supports. Additionally, those who were employed identified co-workers as peer ties and authority ties as members of their network, replacing former PSE ties from the previous year.

Graduate A’s theatre passion ensured that he continued developing new friendships as he participated in his theatre group activities. He excitedly shared that everything “feels great ... right now. I am in a new play! I have gotten to know new people.” Parent A confirmed Graduate A’s “passion is theatre” and that although his involvement in theatre “at this level is grueling,” it was a meaningful and fulfilling experience. Graduate D’s long-term job experience at her place of employment, her extensive volunteer hours at her parent’s school, and her involvement in a church youth group ensured that she had an extensive network. Graduate A and Graduate D were also in a serious relationship, which led to more extensive networks from both perspectives as they shared common ties.

Graduate B, however, shared that he spent most of his time working. Apart from work, he spent time with his family or his girlfriend. Although he had always been interested in basketball, he could no longer play because of his schedule:

I have only been working. No time for anything else. Working at [the store]. Work there every day. I hang out with family for a bit. Might go out to eat, shopping, church. It depends on the mood ... I don’t do basketball anymore. I am retired. I am out of shape!

Parent B confirmed that Graduate B did not have much time for anything else other than work and family as his job took “anywhere between 20–28 hours a week.”

Graduate C and Parent C also reported that Graduate C had not had much time to do anything else because of his work schedule. Graduate C shared that apart from work, “I spend time at home. Haven’t been doing very much.” Parent C elaborated that Graduate C “has been hanging out with family most of the time. He has done a few things with friends [family friends]. No changes, to be honest. It is still kind of the same. I wish it were better.”

Graduate E reported continued involvement in his church youth group as he had “a lot of friends at [Youth group].” He was also immensely grateful for a friendship that he had cultivated with a former PSE mentor who would visit him every month to go out and have fun, saying, “I am very close to him.” Parent E shared that Graduate E was “very close” to this former mentor and that he “got a lot of help from him [mentor]” in terms of support. Friendships developed from strong mentor-mentee relationships in the PSE continued to take prominence in Graduate F’s life. She reported “text[ing] her friends every day” and occasionally meeting up with them. Graduate F also continued to find support in a group for others with an ID. Despite working at a restaurant for several months before termination, Graduate F did not identify co-workers during the interview. Parent F shared that although she worked there for a while, she did not form any close friendships with her co-workers and appeared to only get along with the customers.

3.2Research question two: Addressing the employment outcomes of graduates one year post-PSE and exploring assertions of self-determination

At the time of these interviews, five out of six graduates in this combined cohort were employed. One had recently become unemployed. The views shared from graduates’ and parents’ perspectives take into account employed and unemployed experiences post-graduation. In answering our second research question, we observed some supports and challenges that determined graduates’ employment outcomes. Here, we also explored expressions of self-determination among graduates by asking who introduced graduates to a job and using that question to further generate a conversation about graduates’ employment choices.

3.2.1Supports and challenges that determine employment outcomes

Graduates and their parents were vocal about supports that encouraged them at the workplace and those factors that contributed to difficulties and dissatisfaction at the workplace. These were intertwined topics that had implications for workplace success for these graduates. Graduate A shared that although he had his present job on campus, there was one other job at a local restaurant that he had held on to for a few years intermittently until he decided to resign after a management change. Parent A elaborated on his decision to leave:

He was working at [restaurant], but they were no longer giving him the support he needed. Unfortunately, this happens with young men and women with ID. They [employers] do not take the time to support them. He was very close to [an employee], but when they changed management, she quit. Once she left, they hired a new manager. He [Graduate A] was not happy, and it was time to exit. These young adults, if they are not going to have the support, will not be a great experience for anybody ... the previous owner was very invested in him. He was good friends with him.

Parent A explained that even at Graduate A’s present place of employment, the best supports have come from those invested in seeing him succeed. However, as is often the case with workplace turnover, the departure of these supports leaves a gap in the individual’s life. She shared:

Two people he was close to, unfortunately, have left. He knew them since his [PSE] internship. He hated it because they were very invested in him. It made him sad, but he was told that it is how work goes. He worked with them directly.

Parent B also felt the need for those who are invested in a graduate’s success at the workplace, stating “some of the people who told him that he could advance have gone separate ways,” and because they left, “he felt that he would not be able to move up, be able to advance.”

An additional challenge that graduates face is the loss of disability insurance, such as Medicaid, if they work full-time. Parent E explained that while Graduate E was instrumental in securing his present job and could conceivably obtain more hours, she was reluctant for him to do so, stating, “I don’t want him to lose his benefits. He needs to keep his Medicaid so [he] cannot do more hours.” Graduate E understood this predicament as he also shared that he was “not looking for another job,” as it would be “too much.”

Employers’ ability to reduce employee hours or terminate them without explanation also added to graduates’ employment frustrations. Graduate E also had a previous job that continued from his PSE internship but quit when the management was changed. Parent E explained that under the new management, his hours were cut down “from four days a week to two days, then one day, and then one day every other week.” She added that no explanation was given to her or Graduate E for this cut in hours despite her repeated inquiries.

Graduate F who recently lost her job at a restaurant for reasons that remain unknown, shared that she had enjoyed the job, “I love [sic] the job at [restaurant]. Having fun [sic]. Got people drinks, folded pizza boxes, and cleaned tables, picked up trash, do refills. I was happy [about being there]. I miss [restaurant].” Parent F elaborated:

It was a big disappointment for her when she was laid off. I took her every day. She worked for three days for three hours. Every single evening when she was on the way to work, she would say, “I love my job.” It broke my heart when they laid her off and especially when they did not say why.

Parent F had reached out to program staff to intervene in this case to determine the reason for termination. Still, no explanation was given despite sustained inquiry efforts, leaving Graduate E and her parent frustrated.

The COVID-19 pandemic added to employment woes by forcing the closure of most businesses in the area. The pandemic led to furloughs for four out of the five graduates at the time of these interviews. Graduate F’s efforts to pursue a promising job opportunity had to be put on hold as the business closed because of the pandemic. Existing health concerns that could be made worse with a COVID-19 infection also led to an extended temporary suspension of Graduate C’s job at a hospital as his parent shared, “after today he won’t be able to work because of the virus. His dad will talk to his boss and tell him because it would be safer.” Only Graduate B was confident that his employment would not be disrupted because of safety measures in place.

3.2.2Limited expression of self-determination in employment choice

Although personal growth was evident in many forms, such as increased self-determination, self-esteem, and independence, the overall expression of self-determination in terms of employment choice appeared to be limited among the program’s graduates. One graduate continued in her job that she interned with while in the program until she was laid off. At the time of these interviews, she was unemployed. However, the remaining graduates who were employed, except for one, indicated that they were encouraged and helped in their job application process by a family member.

Graduate A, who secured a job on campus, shared that he had applied for the job with encouragement from his parent and a former mentor, “I applied for the job myself. I knew what it was. I knew where it was.” Parent A acknowledged that she encouraged him with the application because it “followed an internship, and I helped to follow through.” Additionally, Parent A shared that Graduate A was also communicating with another office on campus about a job possibility:

He did an internship with [the office] during [PSE] and has been so involved with campus events and kept in touch with the Director. He has been emailing and asking her for jobs because he loved that internship.

Graduate B’s father encouraged and helped him apply for his present job by assisting his graduate in filling out the job application form. Although the job took up all of his time, and he was satisfied with it, Graduate B stressed that he did not see himself retiring in this job. The desire to move beyond the present job experience and gain more success in life was evident as he shared that he would like to return to school sometime in the future, “I am trying my best to get my Work Keys test” because “I hope by next Fall to be in school. To get a degree is my goal. I want to be like my mom ... she has two or three degrees. I want a desk job.” He recalled an enjoyable internship experience he had while in high school that enabled him to work a desk job and wished he could have that experience again. Parent B concurred, adding, “one of these days he will take the test. He does practice tests, and they [the community college] can monitor when he gets on the system.” She shared that Graduate B was pursuing this goal on his own as “he has always wanted to get a diploma ... getting a diploma for him opens the door to college, so he really wants to get it because he has other things he would like to do.”

The theme of parental encouragement continued with Graduate C, who shared that although he applied for his present job, it was because “dad told me about it and found it for me.” Graduates who were able to secure employment in places that had people with whom they had a strong connection continued to thrive in those jobs, like Graduate D, who has known her employer since she was a child. Graduate D shared that she enjoyed her present position at a child daycare center and saw herself moving up the ladder to “be an assistant teacher, then move up ... right now, I work in the back as teacher’s aide.” Parent D agreed that her long connection with this employer helped her secure her present job.

In terms of employment choice, self-determination was most evident in Graduate E, who managed to secure a job at a recreation center on his own. He shared, “I went there to [place of employment]. I like cleaning the treadmills, vacuuming, and take the trash out. [I am] happy there.” Parent D shared:

He applied for the job himself. This [job] was his decision. He wanted to go work there ... he just kept on and on until I took him. They were impressed and told him which site to go [to apply]. This job was his doing.

4Discussion

Although the social networks of individuals with an ID are often limited to family, caregivers, and close friends, attending college contributes to young adults’ ability to expand their networks. Beyond developing networks solely for socialization, it is hopeful that these networks also provide access to jobs and valuable information and resources that can benefit them career-wise. A PSE experience develops students’ social skills and ability to connect confidently with others and contribute to expanding their networks as these skills grow.

Our study found that half of our program graduates reported increased network size from the graduates’ perspective compared to their network size at T3 (Spencer et al., 2021). However, a closer look at these networks reveals that only two graduates had actual network expansion due to more social and work activities that provided them with avenues to develop more connections. The other half displayed smaller networks compared to T3 (Spencer et al., 2020). These networks were also mostly composed of family ties. The few new ties to appear in these networks were work ties indicating that graduates were using their employment opportunities to build new connections, thereby replacing their former PSE ties with work ties. The presence of new ties in the form of co-workers despite network size was an indication that graduates who are employed do work on expanding their connections and growing their networks. However, the absence of a new experience such as an employment opportunity can also result in some graduates falling back to their established or older connections. Except for Parent A and Parent D, whose graduates had large networks, most parents also observed decreased network size post-program. They reported that although these smaller networks were mostly composed of family, a few work ties were reported as peers. Parents’ representation of smaller network for graduates also confirm that post-PSE employment is crucial to developing a graduate’s network, especially in terms of new ties. The absence of such an experience may result in a network made up of the same familiar supports, especially if there are not many opportunities to participate in different activities.

From the perspective of social networks as a contributor to social capital, our study’s findings suggest that most of our graduates can form ties with co-workers and authority figures with legitimate and reward power to help them advance. Coleman (1988) defines social capital as the access provided by bridging ties in one’s network to new resources or social positions. Legitimate power is ascribed to those who are officially in charge, while reward power is assigned to those in a position to reward subordinates with job advancement (Spector, 2012). Growth in areas such as self-determination, self-advocacy, and social skills help graduates make these connections. Although the exit of such supports may pose a problem in terms of motivation or progress in job advancement, Green et al., 2016 argues that there are lessons to be learned even in a less than ideal job situation. Ultimately though, “the self-determination of job seekers should be honored by enabling them with primary decision making about placement and services in order to achieve the highest level of job satisfaction” (Wehman et al., 2018).

However, in terms of network size and density and how they relate to social capital, graduates with more extensive and less dense networks can connect with individuals who can bridge new opportunities and resources. In contrast, those with smaller and more dense networks have limited opportunities to expand their social capital. Work responsibilities aside, this program’s graduates’ involvement in a limited number of activities that could help build networks remains a concern and speaks to the lack of support available locally for graduates and families post-program.

Graduates’ employment outcomes in this study are varied, with the majority reporting that they were gainfully employed a year post-program. However, the challenges encountered by graduates highlighted here suggest that reasons for termination or graduates themselves leaving a job may need further exploration. Perspectives regarding why graduates were let go or why they chose to leave a job are only from parents’ perspective and highlight employer deficiencies. Graduates themselves were unable to explain why they decided to leave a job or why they were let go. Agran et al. (2016) report that long term efforts to determine factors that promote the employability of individuals with an ID found that most of these individuals lose their jobs because they do not fit in socially at the workplace, and rarely because they are unable to perform the job. Their “systematic and updated replication” of the Salzberg et al. (1986) study found that employers valued social skills such as seeking clarification for unclear instructions, refraining from touching others inappropriately, carrying out direct instructions, notifying supervisors when needed, and punctuality at work (Agran et al., 2016).

In contrast, skills frequently taught were focused on social amenities and not those considered top-rated employability skills that Salzberg et al. (1986) refer to as “production-related skills.” These production-related skills are associated with task performance and task efficiency. However, it is unclear if the lack of production-related skills were the reason for the termination or resignation of a few graduates from this program. The PSE program and employers were not connected in an official capacity that would have allowed the program to communicate with employers to exchange feedback on graduates’ work performance.

An observation of the types of jobs our graduates held also shows that these remain low skill jobs with fewer benefits such as folding boxes, taking out the trash, and wiping down equipment (Ross et al., 2013; Stodden and Dorwick, 2000). Ju et al. (2012) caution that employers’ expectations have changed since the 80 s and 90 s. A rethinking was, therefore, required as to what skills employers value. Because of 21st century advances with technology at the helm, students with an ID must develop some proficiency in these more complex skills and demonstrate these skills to gain access to more highly skilled and better-paying jobs. Green et al. (2016) highlight the need for job coaches and job developers that help students explore interests as they prepare for internships that offer authentic work experiences. Occasionally, students may choose to acquire challenging internships to build skills that they may not already possess.

Our study also highlights continued parental influence in graduates’ employment choices, an indication for the need to strengthen self-determination instruction to help students develop their sense of agency or at least the ability to express their interests. Although families were inspired by the gains that students had made post-program, parent responses post-program show that parents still had significant strides to make before they were ready to let go completely. Miller et al. (2016) argue for “life-changing” experiences such as students living apart from family as they attend the PSE program, to develop independent living skills among students, and help both parties in the “letting go” process. Although parents in the present study did not show any opposition to integrated employment, this remains an aspect that some families are concerned about even if their adult children or wards are enthusiastic about such opportunities (Migliore et al., 2007). However, families in this study did highlight the importance of workplace supports in an integrated setting for a successful workplace experience for their graduates. This finding is in line with the analysis from Gilson et al., 2018, which reports families prioritizing workplace dimensions such as personal satisfaction and social interaction above pay and benefits. However, in this study, there was some concern about benefits. Gilson et al., 2018, also stress that when considering the employment prospects of individuals with an ID, providers should tailor “resources, training, and services to address the needs and desires of individual families.” Dialogue between providers and families can lead to the provision of appropriate workplace supports. These, in turn, can result in more successful employment outcomes, the development of quality workplace networks, and, eventually, a greater ability on the part of graduates to assert self-determination in employment decisions.

We acknowledge that a more nuanced argument needs to be made when considering self-determination expressions, especially when it comes to major life decisions. Parents of young adults with an ID who have had to protect them from young will always be constant social-emotional supports and play an overarching role in their child’s life, especially in decision-making. Although one of the goals of a PSE experience is to develop self-determination, the process of PSE graduates expressing this skill will not happen overnight. It will require dialogue between PSEs, students, and families to raise awareness, create buy-in, and increase confidence. As some of our graduates’ experiences in this study indicate, families are immediate and necessary advocates to protect them in situations that could prove disadvantageous to them in many ways such as loss of benefits, unexplained reduction in work hours, and termination. Often, individuals with disabilities who are employed have to incur high out-of-pocket expenses to maintain access to the services and supports they need that are not covered by private or public health insurance plans or which employers also refuse to cover (Denny-Brown et al., 2015). Mann and Stapleton, 2011, argue for public policies that customize supports according to the needs of workers that would help these workers maintain employment with assured services and support. Family advocacy may also be necessary where wages are concerned, given the acknowledged wage-offer gap between those with and without disabilities which begins in early adulthood and may lead to differences in human capital, employment, and earnings between older adults in the same groups (Mann & Wittenberg, 2015). This wage gap is often most significant for those with cognitive limitations.

4.1Implications for policy and practice

Although the findings reported in this study are from a small sample, they illustrate a dilemma concerning the emphasis on independent living and work supported by PSE programs on the one hand and social safety net considerations for individuals with ID on the other. Individuals with an ID want to work full-time but families are concerned that full-time work may lead to the loss of Medicaid and other benefits. PSE programs aim to prepare students for gainful employment and independent living. Families often do not want to give up the security of Medicaid and other benefits, even though full time work might bring in more money. Given the economic uncertainties surrounding employment, especially during a time like the current COVID-19 pandemic, having essential benefits cushions the potential economic impact of job loss. Therefore, the reluctance of families to allow or encourage full-time employment during a time like this, especially, is unsurprising. Perhaps the development of policies that change this perception of some families would help give people with an ID greater opportunities for full time employment. Here, we echo the call for balanced conversations between practitioners, service providers and families, as proposed by Gilson et al. (2018), to navigate these varying perspectives.

Although this PSE program is still unable to provide on-campus residential housing, it facilitates off-campus housing in apartments shared by students and mentors. We believe that this is a step in the right direction to help students develop their independence and instill confidence in families to let go. The ability to use SNA data to generate meaningful conversations with families can help them realize that “student’s skills and sense of self may plateau at home,” so they would likely benefit from living away during their PSE experience (Miller et al., 2016). SNA data can also be utilized to promote conversations with institutional stakeholders to create buy-in for eventual on-campus residential and housing opportunities and help them understand the institution’s role in the community as an advocate for individuals with an ID. The visible presence and assimilation of students with an ID on campus can generate greater acceptance of these individuals in the community and develop a higher sense of advocacy for these individuals among the student body, some of whom will eventually hold prominent social positions that could benefit this population.

Partnerships formed with local companies can also provide graduates with employment opportunities beyond the PSE if they have not already secured employment. One strategy that PSEs could adopt, as highlighted by Reisen et al. (2019), is to use customized employment (CE) to develop an individualized relationship between employees and employers in ways that met the needs of both based on the interests and strengths of students, and the specific needs of employers. Particular strategies for implementing CE include exploring jobs with individuals with an ID, customizing a job description based on employer needs, developing a set of job duties and criteria for performance evaluation review, acting as an employment mediator, and providing supports to the individual at the job placement (WIOA, 2014). Such individualized work plans could also reduce unexplained termination incidences and create opportunities for PSE graduates to improve their work performance based on set criteria. PSE programs can also foster employment preparation by helping students build resumes, acquire necessary soft skills, career-specific skills and credentials, and develop a professional network (Domin et al., 2020).

As an extension, a determination of 21st-century employability skills from employers’ perspective would allow the PSE program to expand or modify its current social skills development curriculum. Some modifications to the special education high school curriculum to include social skills for employment and changes to high school students’ Individualized Education Plan (IEP) to include PSE options for those who want to go to college may also benefit students with an ID. Families who are aware of PSE options would be more apt to consider these options when they understand that time in a TPSID program, having a college credential, and experiencing paid employment before or during the program, increases their student’s chances of employment (Grigal et al., 2019).

Apart from internships that provide short-term exposure to jobs, paid apprenticeships offer a way to help students develop job experience or explore a career path more fully through hands-on and classroom experiences (Wilson et al., 2017). Internship or apprenticeship partnerships with local companies can ensure students’ jobs at least a year post-PSE program, and help programs monitor student employment outcomes. Presently, this PSE program has a unique partnership with its local VR agency, and more recently, a workforce development agency supporting PSE program students with employment. The collaboration with the former provides some students with limited funds to cover tuition and fees. The partnership with the latter gives employers the incentive to hire PSE students age 21 and younger to provide on-site job training at the expense of the agency as it covers training costs. This agency’s employment experience also provides students with an authentic working experience that extends beyond job functions and includes filling out important documents such as tax forms and timesheets. The development of three-way collaboration between the PSE and these agencies could result in additional supports that would help PSE students better prepare for competitive employment. PSEs hold an essential role in engaging with these agencies and bringing them to the table for dialogue and collaboration.

4.2Future research

Given that SNA has the potential to generate quantitative and qualitative information that has several implications for PSEs, it should remain part of the evaluation activities of this PSE. Additional longitudinal studies of future cohorts can help determine impacts beyond the COVID-19 crisis and replicate the results. Including a fourth timepoint a year post-program will help determine the program’s effectiveness in improving students’ employment and independent living outcomes and provide essential feedback for the program’s continued improvement.

4.3Study limitations

This study was conducted at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic that resulted in a few participants furloughed and at least one having to put her job search on hold. The uncertainty of this frightening situation may have also caused participants to rely more on their family members and families to become more protective. Therefore, it is necessary to continue to observe network growth and employment outcomes a year post-program with remaining graduating cohorts to determine what changes occur in PSE graduates’ lives once this situation improves. From the perspective of methodology, the switch in the mode of interviews from in-person to phone interviews could have also impacted the quality of data collected. While participants engaged in longer conversations as they responded to questions in-person, this was not the case when the interviews were held over the phone, resulting in shorter interviews.

Lastly, the small sample size and the specific characteristics of this PSE program (e.g., its geographic location, and its relative newness), limit the generalizability of the findings. Although, potential policy implications of the findings can be seen as applicable to employment issues for graduates of many PSE programs.

4.4Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the findings provide insight into PSE program graduates’ development and employment outcomes, a year post-program. Graduates use the skills learned throughout their PSE experiences, such as self-determination, self-advocacy, independence, and social skills to negotiate life and employment and express these skills at different levels through their choices and behaviors. Though, major life decisions still require parental involvement as parents continue to provide social-emotional and protective support. The rules in place in the current system regarding benefits prevent graduates from fully exploring employment opportunities as graduates and their families fear losing these essential benefits. Therefore, the incompatibility of these rules with PSE goals forces families to be more involved in employment-related decision making, thereby curbing graduates’ expression of self-determination in this area.

PSE graduates’ social networks are also dependent on their opportunities, a major one being employment. New network connections are mostly associated with jobs in the form of co-workers and supervisors or managers in an authority role. These workplace connections not only offer work place support to program graduates but also replace former PSE program connections as graduates spend a significant portion of their time at work. The success of graduates in their workplace also depends on whether they possess the employability skills that employers value. Collaboration between local agencies and partnerships with local employers can help PSEs determine these employability skills and incorporate them into the program’s curriculum and work/internship opportunities. We believe that our findings also encourage institutional stakeholders to increase efforts that promote the inclusion of students with an ID to provide them with better independent living and employment outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The research reported here was supported, in part, by the Office of Post-Secondary Education, U.S. Department of Education, through grant #P407A150076 to the University of South Alabama. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Office of Post-Secondary Education or the U.S. Department of Education.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical declaration

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of South Alabama Institutional Review Board (Protocol number #17-146; Protocol #1059466-1 in IRBnet).

Funding

The work is funded by a grant from the US Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education Grant #P407A150076.

Informed consent

Written and oral consent was obtained from both the participants and their legally authorized representatives.

References

1 | Agran, M , Hughes, C , Thoma, C. A , & Scott, L. A. ((2016) ) Employment social skills: What skills are really valued? Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 39: (2), 111–120. |

2 | Akkerman, A , Janssen, C. G. C , Kef, S , & Meininger, H.P. ((2016) ) Job satisfaction of people with intellectual disabilities in integrated and sheltered employment: an exploration of the literature. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 13: (3), 205–216. |

3 | Amado, A. N , Stancliffe, R. J , McCarron, M , & McCallion, P. ((2013) ) Social inclusion and community participation of individuals with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51: (5), 360–375. |

4 | Asselt-Goverts, A. E , Embregts, P. J. C. M , & Hendriks, H. C. ((2015) ) Social networks of people with mild intellectual disabilities: characteristics, satisfaction, wishes and quality of life. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59: (5), 450–461. |

5 | Bigby, C. ((2008) ) Known well by no-one: trends in the informal social networks of middle-aged and older people with intellectual disability five years after moving to the community. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 33: (2), 148–157. |

6 | Borgatti, S. P. ((2002) ) NetDraw: Graph visualization software. Harvard: Analytic Technologies. |

7 | Borgatti, S. P. ((2006) ) E-NET software for the analysis of ego-network data. Needham, MA: Analytic Technologies. https://sites.google.com/site/enetsoftware1/ |

8 | Borgatti, S. P , Everett, M. G , & Freeman, L. C. ((2002) ) UCINet for windows: software for social network analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies. |

9 | Borgatti, S. P , Everett, M. G , & Johnson, J. C. ((2018) ) Analyzing social networks. SAGE. |

10 | Bouck, E.C. ((2014) ) The postschool outcomes of students with mild intellectual disability: does it get better with time? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58: , 534–548. |

11 | Butterworth, J , Hall, A. C , Smith, F. A , Migliore, A , Winsor J , Domin, D , & Sulewski, J. ((2013) ) State Data: The national report on employment services and outcomes. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion. |

12 | Carnevale, A. P , & Desrochers, D. M. ((2003) ) Preparing students for the knowledge economy: What school counselors need to know. Professional School Counseling, 6: , 228–236. |

13 | Coleman, J. S. ((1988) ) Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94: , 95–120. |

14 | Curryer, B , Stancliffe, R. J , R. B., Dew, A. ((2015) ) Self-determination: adults with intellectual disability and their family. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40: (4), 394–399. |

15 | Deci, E. L. , & Ryan, R. M. ((2000) ) The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11: , 227–268. |

16 | Denny-Brown, N , O’Day, Bonnie , & McLeod, S. ((2015) ) Staying employed: Services and supports for workers with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 26: (2), 124–131. |

17 | Devlieger, P , & Trach, J. ((1999) ) Mediation as a transition process: The impact on postschool employment outcomes. Exceptional Children, 65: (4), 507–523. |

18 | Domin, D , Taylor, A. B , Haines, K. A , Papay, C. K , & Grigal, M. ((2020) ) It’s not just about a paycheck”: Perspectives on employment preparation of students with intellectual disability in federally funded higher education programs. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 58: (4), 328–347. |

19 | Donnelly, M , Hillman, A , Stancliffe, R. J , M., Whitaker, L , & Parmenter, T. R. ((2010) ) The role of informal networks in providing effective work opportunities for people with an intellectual disability. Work, 36: , 227–237. |

20 | Eisenman, L. T , Farley-Ripple, E , Culnane, M , & Freedman, B. ((2013) ) Rethinking social network assessment for students with intellectual disabilities (ID) in postsecondary education. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 26: (4), 367–384. |

21 | Folk, E. D. R , Yamamoto, K. K , & Stodden, R. A. ((2012) ) Implementing inclusion and collaborative teaming in a model program of postsecondary education for young adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 9: (4), 257–269. |

22 | Forrestor-Jones, R , Carpenter, J , Coolen-Schrijner, P , Cambridge, P , Tate, A , Beecham, J. , Hallam, A , Knapp, M , & Wooff, D. ((2006) ) The social networks of people with intellectual disability living inthe community years after resettlement from long-stay hospitals. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19: , 285–295. |

23 | Frielink, N , Schuengel, C , & Embregts, P. J. C. M. ((2018) ) Autonomy support, need satisfaction, and motivation for support among adults with intellectual disability: testing a self-determination theory model. American Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 123: (1), 33–49. |

24 | Froeh, D , (in press). Social network analysis as mixed analysis. In A. J. Onwuegbuzie & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide for mixed methods research analysis. Routledge. |

25 | Gilson, C. B , Carter, E. W , Bumble, J. L , & McMillan, E. D. ((2018) ) Family perspectives on integrated employment for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 43: (1), 20–37. |

26 | Gilmore, L , & Cuskelly, M. ((2014) ) Vulnerability to loneliness in people with intellectual disability: An explanatory model. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11: (3), 192–199. |