Lessons from the Diversity Partners Project: Using knowledge translation to strengthen business engagement strategies and improve employment outcomes for job seekers with disabilities

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Effective employer engagement strategies are critical to the provision of high quality employment supports for individuals with disabilities. There is a gap in both relevant research and knowledge surrounding these strategies. This article describes the knowledge translation (KT) activities of the Diversity Partners Project, which are designed to promote and contextualize a set of promising employer engagement practices to improve outcomes for job seekers with disabilities.

OBJECTIVE:

KT is an emerging area of study in the field of disability and employment. This article explores the role of capacity building in a knowledge translation intervention for employment service providers.

CONCLUSIONS:

Ongoing efforts on the Diversity Partners Project have involved KT principles as an integral part of the process. The target audience of the intervention has been actively engaged in the process from development to implementation to evaluation. Overall, frontline staff have been receptive and even eager for the on-demand, business-focused tools made available to them on the website, though broad adoption has been hindered by a number of factors.

1.Background

Effective employer engagement strategies are critical to the provision of high quality employment supports for individuals with disabilities. Despite this fact, there is a paucity of research-based strategies in the literature, which when applied by employment service professionals and their organizational leaders, could be effective in improving the quality and scope of business relationships (Lueking, et al., 2004). In a 2016 review of the literature regarding demand-side factors and their impact on improving competitive employment rates for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, only six studies were found which specifically sought to capture employer perspectives as the study population (Ellenkamp, et al., 2016). Those findings are consistent with the literature scan conducted during the 2015 development phase of the Diversity Partners Project, which uncovered nine articles directly relating to effective business engagement practices, most of which were descriptive in nature (Harris, et al., 2017). The challenge remains not only to identify promising and evidence-based employer engagement practices, but to develop effective methods of encouraging the adoption and use of those practices in community-based organization settings (Gilbride & Sensrud, 2008). This article describes the knowledge translation activities of the Diversity Partners Project, which are designed to promote and contextualize a set of promising employer engagement practices to improve outcomes for job seekers with disabilities.

1.1.A knowledge translation project

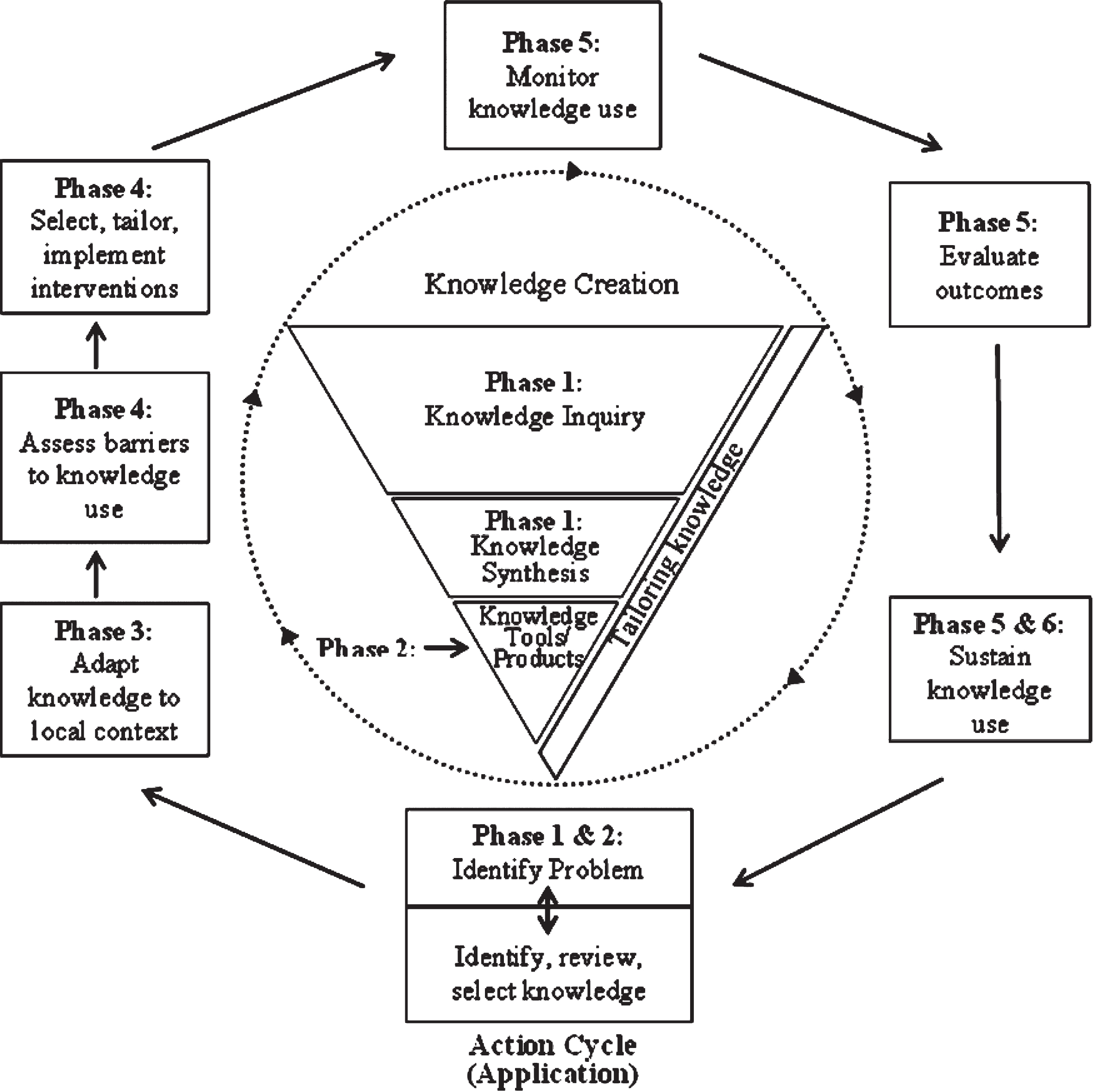

The Diversity Partners Project is an intervention designed to improve the relationships between employment service professionals and employers. It is an ongoing effort, funded to Cornell University by the US Department of Human Services Administration on Community Living, to curate a set of promising demand-side strategies that can be applied at both the practitioner and organizational level to improve employer engagement on behalf of job seekers with disabilities. A secondary aim of the project is to increase representation of people with disabilities in career-driven training and supports within the public workforce development system, as well as secondary and post-secondary education and training programs. Diversity Partners utilized a knowledge translation (KT) framework to design a multi-faceted intervention, as described in Harris, Switzer, and Gower (2017). The National Institute on Disability Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research defines KT as the “multidimensional, active process of ensuring that new knowledge gained through the course of research ultimately improves the lives of people with disabilities, and furthers their participation in society” (NIDRR, 2005). The knowledge translation effort described in the 2017 paper outlined the efforts undertaken to understand the everyday context of employment service professionals and the related needs of the employers whom they seek to support. The first phase of the Diversity Partners Project, (Knowledge Inquiry and Knowledge Synthesis) is outlined in Fig. 1. The resulting intervention was designed based on the knowledge gained during those initial phases of the project, and specifically considered the context, the barriers, and the existing skills of the community of employment professionals. Leadership groups were introduced to materials created for them to share within their organizations, in order to begin to create a culture of excellence when serving employers on behalf of job seekers with disabilities.

Fig.1

The Diversity Partners Knowledge Translation Process.

1.2.Supporting capacity building

The Diversity Partners intervention demonstrated that placement professionals share common challenges, and overcoming those challenges requires the input and creativity of organizational leaders. One of the objectives of Diversity Partners is to serve as a capacity building intervention to support on-going growth and change initiatives within employment services organizations. As described by Wilén (2009), capacity building is an evolving term that supports local ownership of problems and solutions to issues that impact communities. Chaskin (2001) defined community capacity building as “the interaction of human capital, organizational resources, and social capital existing within a given community that can be leveraged to solve collective problems and improve or maintain the well-being of a given community” (2001, 295).

While organizational efforts are critical, so are the efforts of individual members of the organization. The Diversity Partners intervention borrows a term provided by Lipsky (2010) to label these actors, referring to the front-line staff who implement organizational practices as “street-level bureaucrats”— those individuals whose daily decision-making processes have perhaps the greatest impact on the nature of business relationships. In order to ensure organizational success in employer engagement, the work of these street-level bureaucrats must be given context and direction. Another objective of Diversity Partners is to provide this context and aid in the promotion of organizational planning and strategies that support and enhance the work of frontline employment staff. To support this organizational planning, one of the products of the Diversity Partners initiative is a Leadership Toolbox, which includes facilitator’s guides, conversation guides to utilize when planning with staff, and action planning tools. The Leadership Toolbox also includes an introduction to materials created for frontline staff, which are described below.

2.Process

2.1.Capacity building around employer engagement

To determine how the information on effective employer engagement contained in the Diversity Partners intervention could be contextualized and applied to the capacity building efforts of individual organizations, it was necessary to create a framework for consideration of critical elements. These capacity building activities may include internal and external training opportunities, on-boarding activities focused on the importance of employer partnerships to the organization, engagement with more knowledgeable others within the organization who can model business engagement practices, and guidance on business partnerships from organizational leadership. The Diversity Partners project team carried out pilot testing of the Diversity Partners Leadership Toolbox with organizations from across the United States by conducting two-day strategic planning sessions with two leadership groups from each of the Diversity Partners target audiences: workforce development personnel and disability service providers. Organizations were asked to identify leaders to participate in the planning sessions and to invite other key personnel who have employer contact: employment service professionals, agency marketing and development personnel, those who manage contracts with businesses, etc. Organizations were often uncertain about whom to invite to the sessions, or inadvertently left out key staff members, which required guidance from the project team. The participating organizations were told that the goal of the planning sessions was to facilitate conversation, decision making, and action planning that will support employer-focused, demand-side practices that lead to maximized relationships with businesses and, ultimately, improved employment outcomes for job seekers with disabilities.

2.2.Supporting implementation of employer engagement

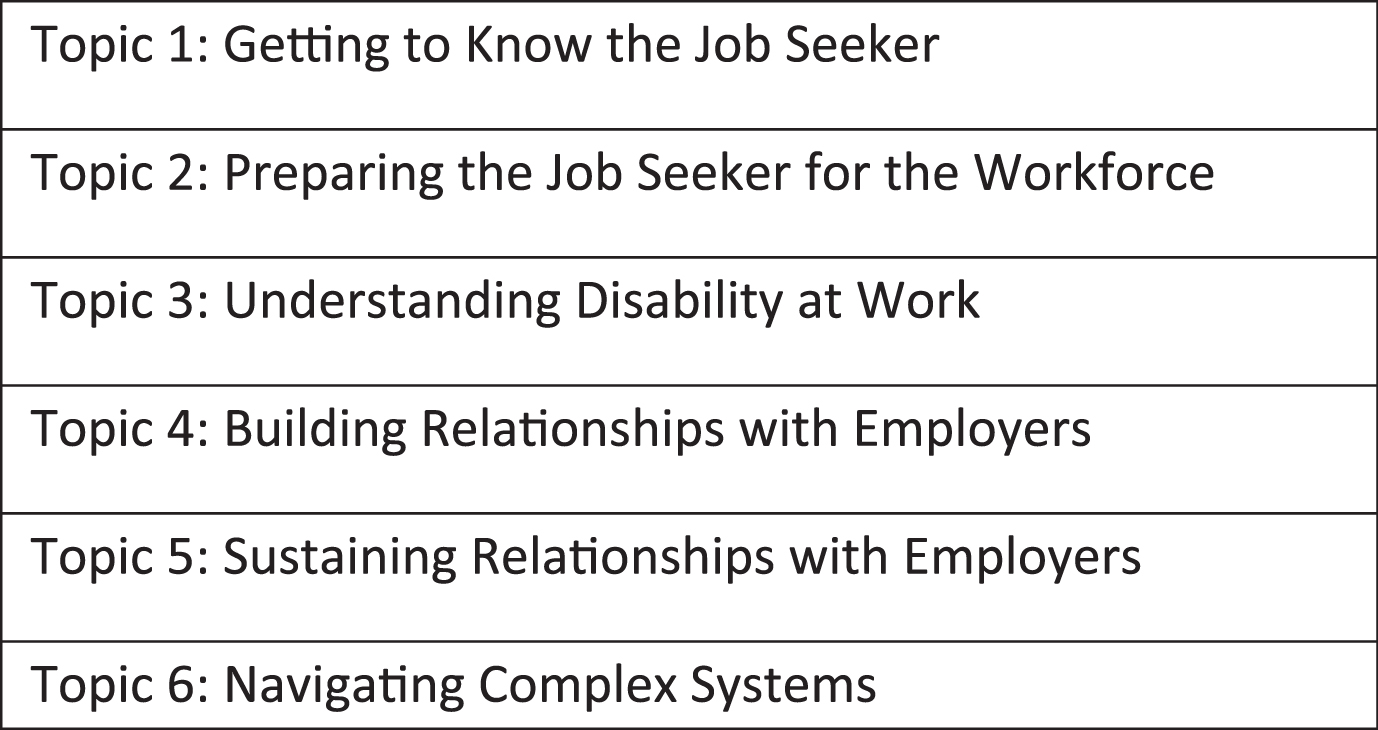

Organizational change requires the introduction and maintenance of a knowledge base for frontline staff who will be expected to approach their work differently as a result of the change efforts (Raynor, 2014). As a result, one objective of the leadership sessions was to introduce the Diversity Partners Frontline Toolbox, designed as an online learning tool for frontline employment services staff, which supports the application of critical employer engagement principles. During the pilot phase, the introduction of the Frontline Toolbox allowed the project team to contextualize and refine the content with information gathered from the field. The Frontline Toolbox consists of a series of 21 online learning modules covering six topical areas. The modules are designed to provide employment service professionals with the knowledge and skills they need to develop strong, effective relationships with employers. During the pilot testing phase with organizational leaders, organizations were introduced to the Frontline Toolbox with the intention that their frontline staff would utilize the modules to implement agreed-upon changes after the organization completed the leadership session. Frontline staff were asked to provide feedback to the development team regarding the relevance of the content, and also regarding the effectiveness of the delivery method of the Frontline Toolbox. (See Fig. 2 for a list of the topical areas included in the Frontline Toolbox.)

Fig.2

The Diversity Partners Frontline Toolbox.

During the leadership pilot session, the project team engaged organizations in a capacity-building discussion. In small work groups, participants were asked to reflect upon and discuss the five topics included in the Leadership Toolbox. The project team posed questions, such as: How does your organization define meaningful work for people with disabilities? What is the current pathway to employment for a job seeker with a disability who enters the door of your one-stop career center? How do you ensure accessibility of services to individuals with disabilities? and What is your organization doing to engage employer partners?

Leadership from disability service provider organizations participating in the pilot sessions were asked to think about the resources they offer to staff, including time to focus on employer partnerships, promotional materials, labor market data, and industry information. Small group discussion questions included: What do staff need to have the capacity to create mutually beneficial employer partnerships?; and What skills should be developed or learned?

Workforce development organizations were asked to contemplate the current pathway through their system for customers with disabilities, and conduct a gap analysis in comparison to “the ideal pathway” for job seekers with disabilities seeking services from an American Job Center (AJC). Participants were asked to create visual representations of what an ideal path might look like for a person with a disability who is seeking services from an AJC. Prompts included questions such as: If everything went smoothly and one had all of the resources necessary, what would the ideal path look like? Participants drew upon the visioning exercise to form the basis for an action planning process. For each of the participating organizations, the final afternoon of the second day culminated in in a facilitated group action planning process.

This pilot process with organizational leaders enabled the development team to refine and troubleshoot the content of both the Leadership and Frontline Toolboxes, as well as the instructional design and delivery of the content. The resulting product is a set of no-cost, asynchronous learning modules that can be accessed as often as needed, with a goal of increasing the likelihood of use and adoption of promising practices for employer engagement. Additional features were added to the design of the intervention as the result of feedback from the pilot participants, such as a “supervisor dashboard,” which gives organizational leaders and managers the ability to assign modules from the Toolbox to frontline staff, and monitor completion of those modules.

Upon completion of the pilot site action planning sessions, a Cornell University program evaluator conducted focus groups with: 1) staff (both frontline and leadership) who participated in the on-site leadership sessions, and 2) frontline and leadership staff who used the Frontline Toolbox post-intervention. The goal of the interviews was to gather information on participants’ interactions with the Diversity Partners intervention within the context of their organizations. Specifically, these interviews served to inform the refinement of the Diversity Partners Toolbox for frontline staff by eliciting input from staff at the pilot sites related to their use of the Frontline Toolbox, their perceptions of its usefulness and applicability of the content, and strategies used by their organization to support frontline staff in capacity building efforts. The interviews were intended to assess the potential impact of the Leadership and Frontline Toolboxes by gauging the actions and changes that emerged as a result of the pilot leadership session, and the impact of subsequent staff access to the Frontline Toolbox. Phone interviews were conducted one to four months after the leadership session. The evaluation process resulted in some key observations and an analysis of user feedback, which revealed common themes and lessons from the field, along with implications for future research.

3.Results/conclusion

3.1.Active engagement with employment service professionals

One of the primary lessons from the Diversity Partners intervention is that employment service professionals are looking for more than theoretical frameworks and discussions of best practices for employer engagement as a part of their learning experience. They seek information and training that is cutting edge, engaging, interactive, and immediately available — tools they can utilize both in their offices and on-the-go. One respondent noted: “Presentations on research and best practices are very interesting, but I need something I can use with my staff today.”

Frontline staff have been receptive, even eager, for the business-focused tools made available to them at the Diversity Partners website. For many employment service professionals, access to quality training that promotes promising practices around employer engagement is limited or non-existent. Frontline employment professionals typically come to the field with limited experience providing job placement for job seekers with disabilities, and even more frequently, with a limited understanding of how to implement effective employer engagement strategies. Nevertheless, they are the primary point of contact in most employer interactions and must be prepared to present a business case for hiring people with disabilities that will be relevant to business necessity (Henry, et al., 2014). During the action planning sessions, many frontline staff expressed the value of having a readily-accessible, relevant, online intervention like Diversity Partners available to provide them with critical knowledge, tips and strategies for employer engagement.

3.2.A value proposition

Participants stated that they appreciated the discussion of the value proposition their organizations bring to employers: What services do you have to offer employers? What is the benefit to business? Historically, employment service professionals have been challenged to effectively articulate to employers the value of hiring job seekers with disabilities, while maintaining a capacity-based focus upon the strengths of the job seeker. The project development team often observed employment service professionals utilizing a “charity model” approach to businesses that focuses upon hiring a job seeker because “it’s the right thing to do” or because the employer receives a tax credit. This process of developing an organizational value proposition — what an organization can offer a business that will help them to address business needs – resonated with the employment professionals who participated in the Diversity Partners pilot testing. One respondent stated that: “ … we realized we have a lot to offer the business community, such as disability awareness [education].” Another participant in the pilot evaluation expressed the importance of “looking at yourself as being valuable to employers. There are so many ways!” and “Thinking outside the box – about ourselves and our role in the community...” These comments indicate a critical shift that occurred in the mindset of the participants as a result of the pilot intervention, and in how organizations market their services to businesses. The Diversity Partners pilot training and facilitated action planning sessions led to some “light bulb moments” for employment service professionals and their organizational leaders.

3.3.Capacity building: Devoted space for collaboration and action planning

Staff stated that they found the leadership sessions to be very relevant, thought provoking and educational. One of the elements of the session that was perceived by interviewees to be most valuable was the facilitated action planning sessions. Many participants stated that having this opportunity to take part in conversations with others from their organizations and learn what they do, where they excel, and about areas of opportunity and improvement, was a valuable learning and collaborative experience. One person stated that “the most useful part of the training was when we broke out into small groups and could plan together.” Yet another: “In the break-out groups, the most important thing was connecting with people. Splitting up in groups – it was a really great experience!” Finally, one participant sums up the value of having a dedicated time and space for thought and planning on business engagement: “For me, the two days really pulled things together. I went from understanding bits and pieces to a more cohesive picture; both around content and knowledge and our different services and units.”

A key premise of the Diversity Partners initiative is that in order for frontline employment staff to employ effective business engagement strategies, their organizational leadership must strategically plan for employer engagement and be on board to support staff efforts. The facilitated action planning pilot sessions offered organizations and communities a space in which to learn, reflect and engage in proactive activity around business engagement practices and strategies, by including both organizational leadership and key frontline employment staff as a part of the planning process. Nonetheless, organizations often are reactive, rather than proactive, to changing conditions and circumstances in their communities. Kendrick (2001) speaks of the reluctance of organizations to take a thoughtful look at their own beliefs, values and practices, which can lead to organizations becoming “stuck” or stagnant in ineffective and outdated services and practices: “The tendency of organizations to revert to a kind of ‘regression to the mean’ tends to blunt the kinds of penetrating truths that are needed for progress” (p. 2). In other words, if an organization is not willing to put the time, thought and effort into engaging with 21st-century employers differently, by supporting staff to obtain the skills and tools needed to meet business needs, nothing will change, and outcomes for job seekers with disabilities will remain the same.

3.4.Use and adoption of the diversity partners intervention

Upon completion of the face-to-face pilot testing sessions, each participating organization was charged with introducing the Frontline Toolbox (the 21 on-line learning modules) to their staff. Both frontline staff and organizational leaders were then encouraged to utilize the learning modules, and provide feedback on the modules to the Diversity Partners team. The intent was to demonstrate how employment service professionals would utilize the modules to support their work with employers and job seekers with disabilities.

For those who engaged with the Frontline Toolbox after the pilot testing phase, users considered it to be useful. Strengths noted on its overall functionality included its flexibility and adaptability to the varying skill levels and learning needs of the user: “I liked that you had the freedom to start where you wanted, that it took into account what I might already know;” “I liked the variety in presentation and that it was trying to appease different learning styles.”; and “It’s like a living entity, very fluid.” The intent of the learning intervention is to allow the user the opportunity to pick and choose from the 21 modules and develop their own personalized plan for learning.

Users also noted strengths related to the quality and usefulness of the training content offered in the Frontline Toolbox. Users stated that they liked the many resources available, and that the intervention is grounded in research and best practices. Multiple users indicated that the Frontline Toolbox and its 21 learning modules are valuable for staff of all experience levels, from the beginner (“It felt like it would be useful for beginners for background information, for learning how to do the job.”) to the more seasoned staff (“It would also be useful for people who have been involved [in the field] for a while: for resources, new ideas.”) Other users commented on how one learning module taught them about the importance of aligning both the skills and learning needs of the job candidate to the workplace culture and environment best suited to the job seeker. One user said that “it was refreshing to think that it’s ok to stop and think like that. It was a new perspective.” Similarly, another user spoke of “that time when you just need to look for that light bulb moment.” Thus, when frontline employment staff took the time to engage with the Frontline Toolbox, it provided them with the ideas, energy, and motivation to innovate and to implement new ideas into their work.

3.5.An internal champion

Organizationally, agency leadership noted benefits to using a learning tool like Diversity Partners, though one critical caveat related to organizational readiness for capacity building should be noted. A number of key factors should be considered when determining whether an organization is ready and willing to establish a partnership with a business. One of these factors is the ability to identify a champion within the organization. Partnership initiatives are more likely to survive if they have a champion, one who ensures that momentum is maintained, and that the goals of the partnership are achieved (Bryson, 2006). With the Diversity Partners intervention, having this organizational champion — someone open to reflecting upon the need to make changes to the way employer engagement activities traditionally have been done — was imperative to the success of the change effort. For example, one key leader from a disability service provider organization maintained an active involvement in the process and took steps to change organizational practices regarding business engagement. Specific actions included creating an internal work group that meets monthly to share job leads and employer connections, being more mindful of creating a single point of contact for employers, and placing a greater emphasis on developing long-term employment relationships, rather than a “one-off” approach to job development. Tilson and Simonsen (2012) specify that highly successful employment service professionals must possess networking savvy, “characterized as having the ability to connect with people and resources to create and access opportunities” (p. 133) for job seekers. Networking savvy involves utilizing “creative strategies for identifying new opportunities … negotiating mutually-beneficial relationships, and collaborating with colleagues” (p. 133). Having an internal champion who is willing to be nimble in their approach to programs, services and practices for effective business engagement can make a difference in the successful implementation of a change initiative like Diversity Partners. Frontline staff also noted the benefits of engaging with the Frontline Toolbox as being like a two-way street to improving communication with their own supervisors and managers: “It can lead to more interactions with managers: discussing, asking questions … instead of being told what to do.” Another frontline professional stated that “it makes us think differently of how we do our jobs, gives us new perspectives.”

3.6.Barriers to adoption and implementation

Despite the noted usefulness of these web-based learning modules that make up the Diversity Partners Frontline Toolbox, broader adoption has been hindered by a number of factors. A lack of support from organizational leadership, high staff turnover, entrenched organizational systems that struggle to do things differently, funding concerns, and organizations not devoting sufficient time and resources to move to a relationship-building model when developing employment opportunities were among the barriers noted.

When asked to identify barriers to adoption of the Diversity Partners Frontline Toolbox as a tool for staff development and training, organizational leaders spoke of a number of factors. Some mentioned barriers related to managing time and high workloads, as evidenced by comments such as “Unfortunately, after it was wrapped up, it got buried under all the day-to-day work”; and “The day-to-day work takes priority.” Another leader commented that staff “think this is great information, but we’re so strapped for time. When are we going to do all of this?” Another barrier noted not only the lack of time to implement staff training, but also the pressure to only provide billable services: “Honestly, I felt bad putting this work on staff … .Completing the modules for this process … will be difficult when we cannot bill for services during the time the modules are being completed.” Future knowledge translation efforts may focus on overcoming this barrier of perceived lack of time for professional development, which points to the need for a more effective “call to action” around employer engagement aimed at service providers, in order to better engage them in the content.

3.7.A growth mindset

For some organizations, a lack of support for professional development activities for frontline staff comes from competing priorities within the organization. Frontline staff must engage only in billable activities, and professional development is not supported because it takes away from work in the field. The mindset of frontline personnel and leaders can have a lot to do with whether or not an organization is adaptable to the changes that are necessary to operate successfully in an ever-changing environment. Maintaining a fixed vs. a growth mindset can impact the way one approaches challenges, and can impact an organization’s ability to tackle challenges and to improve over time (Dweck, 2008).

In the context of the Diversity Partners intervention, organizational leaders were under similar pressures of high caseloads, staff turnover, busy schedules, and a perceived lack of time for training. Conversely, some leaders – those internal champions for growth and change – were driven to focus upon how they might do things differently in order to develop stronger and more effective business partnerships. This exemplifies a growth mindset. Organizations that sustain a growth mindset and support frontline employment staff in their efforts to obtain professional development that leads to enhanced business engagement strategies are better positioned to adapt to the rapid change that is ever-present in their work and systems.

Pure Challenge is a characteristic identified by Edgar Schein (1996) in his theories of organizational development and change management. Practitioners anchored in this concept of pure challenge are adaptable to growing challenges presented to them and serve as active learners during the process of change. The ability to embrace a growth mindset, and a spirit of pure challenge, may serve frontline staff and organizational leaders well as they face a tumultuous professional landscape.

3.8.Promising practices

Pockets of promising practices exist and deserve further exploration. Many disability service providers, including both frontline staff and leadership, were enthusiastic about having the Diversity Partners resource available “at their fingertips,” particularly for programs that often have limited or no access to quality training for new personnel. Moreover, disability service provider leadership reacted positively to the supervisor dashboard feature of the Diversity Partners website, a tool to support managers in their efforts to offer a professional development plan for frontline staff. One employment services manager who participated in user testing of the Diversity Partners Frontline Toolbox spoke of his best intentions to provide staff with a quality plan for training on effective employer engagement strategies, but as was the case with many leaders who participated in the pilot testing phase, competing demands often make use and adoption difficult in everyday practice. Further research on practices that support capacity building for organizational managers, and methods to foster and support organizational champions for change related to adopting improved business engagement strategies, may be useful.

It is difficult to draw long-term conclusions on the use and adoption of the Diversity Partners intervention beyond the pilot testing phase. Obtaining input from both frontline staff and organizational leadership in the months following the pilot sessions was challenging. For example, in two states where pilot testing was conducted, the program evaluator was unsuccessful in establishing contact with frontline staff. Thus, only organizational leadership was interviewed at those sites.

There are additional implications for future work in the area of knowledge translation and capacity building with employment service professionals from disability service provider and workforce development organizations. Under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) rules, workforce development is charged with making their services accessible to job seekers with disabilities. Although there have been barriers to adoption within workforce development, early evidence indicates that continued outreach and support is necessary to promote inclusive practices for job seekers with disabilities within the workforce development system. Moreover, building upon the Diversity Partners leadership planning sessions across the country, further engagement and evaluation of efforts promoting inter-and intra-agency strategic planning, and better aligned, more cohesive planning among community partners charged with building bridges between job seekers with disabilities and employers, offers the promise of improving demand-side practices utilized by employment service professionals, with the goal of moving the needle on employment outcomes for job seekers with disabilities in a post-WIOA environment.

Future efforts aimed at improving the ability of practitioners to develop mutually-beneficial relationships with employers should be focused on the limiting impacts of service design and delivery, which unintentionally create disincentives for providers to engage in activities that (though beneficial) may not be directly revenue-generating. Expanding options for community engagement and meaningful jobs through analysis of employer engagement practices should be encouraged, as should the relevance of interagency work, and public-private partnerships designed to improve the business relevance of employment support services for job seekers with disabilities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

1 | Bryson, J. , Crosby, B. , & Stone, M. ((2006) ). The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Administration Review, 66: , 44–55. |

2 | Chaskin, R. J. ((2001) ). Building community capacity: A definitional framework and case studies from a comprehensive community initiative. Urban Affairs Review, 36: (3), 291–323. doi: 10.1177/10780870122184876 |

3 | Dweck, C. S. ((2008) ). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Penguin Random House LLC. |

4 | Ellenkamp, J. J. , Brouwers, E. P. , Embregts, P. J. , Joosen, M. C. , & van Weeghel, J. ((2016) ). Work environment-related factors in obtaining and maintaining work in a competitive employment setting for employees with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 26: (1), 56–69. |

5 | Gilbride, D. , & Stensrud, R. ((2008) ). Why won’t they just do it? Rehabilitation Research, Policy, and Education, 22: (2), 125131. |

6 | Harris, C. , Switzer, E. , & Gower, W. S. ((2017) ). The Diversity Partners Project: Multi-systemic knowledge translation and business engagement strategies to improve employment of people with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 46: (3), 273–285. |

7 | Henry, A. D. , Petkauskos, K. , Stanislawzyk, J. , & Vogt, J. ((2014) ). Employer-recommended strategies to increase opportunities for people with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 41: (3), 237–248. |

8 | Kendrick, M. ((2001) ). The empowering value of “life giving” assumptions about people. Opening Keynote Presentation for the Congress “Crossing Boundaries”. Wageningen, Netherlands, September 12-15, (2001) . |

9 | Lipsky, M. ((2010) ). Street-level bureaucracy, 30th anniversary edition: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. |

10 | Lueking, R., Fabian, E., & Tilson, G.P. ((2004) ) Working Relationships. Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co. Baltimore, MD. |

11 | National Council of Nonprofits. (n.d.). What is capacity building? Retrieved October 26, 2018 from https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/tools-resources/what-capacity-building. |

12 | National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research. ((2005) ). Long-range plan for fiscal years 2005-2009. Retrieved September 23, 2006 from http://www.ed.gov/legislation/FedRegister/other/2006-1/021506d.pdf. |

13 | Raynor, J. ((2014) ). Capacity Building 3.0: How to strengthen the social ecosystem. Briefing Paper. Retrieved from https://www.tccgrp.com/resource/capacity-building-3-0-how-to-strengthen-the-social-ecosystem/. |

14 | Schein, E. H. ((1996) ). Career anchors revised: Implications for career development in the 21st century. The Academy of Management Executive, 10: (4), 80–88. |

15 | Simonsen, M. , & Fabian, E.S. , Buchanan, L. , & Luecking, R.G. ((2011) ). Strategies used by employment service providers in the job development process: Are they consistent with what employers want? Technical Report. |

16 | Tilson, G. , & Simonsen, M. ((2013) ). The personnel factor: Exploring the personal attributes of highly successful employment specialists who work with transition-age youth. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 38: (2), 125–137. |

17 | Wilén, N. ((2009) ). Capacity-building or capacity-taking? Legitimizing concepts in peace and development operations. “International Peacekeeping, 16: (3), 337–351. doi:10.1080/13533310903036392 |

18 | Wilson, G. , & Tanner, D. (2016, May 25). University of Georgia Vinson Institute of Government. Presentation at the National Association of Workforce Development Professionals: Building sector partnerships for regional success. |