The power of the employment specialist: Skills that impact outcomes

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Employment specialists have the power to facilitate and change the course of a person’s life. Challenged with juggling sizeable caseloads, changing schedules, administrative tasks, and implementing a diverse set of skills and competencies, it can be difficult for the professional to provide the best supports for each supported employee. In an attempt to bridge the gap between research and practice, this article presents accessible, easily understood concepts to consider when facilitating positive outcomes for supported employees.

OBJECTIVE:

Identify relatable, teachable, and usable concepts that guide employment specialist actions for optimal outcomes.

METHODS:

Strategies, interventions, and competencies were compiled for employment specialists to consider when supporting a job seeker to secure employment. Guidelines were identified through research and experience in the field.

RESULTS:

Best practices are presented in four ‘rules’ to guide employment specialists and managers in evaluating and monitoring their actions while working with supported employees.

CONCLUSIONS:

Employment specialists may use these relatable ‘rules’ to evaluate their actions and incorporate best practices that support optimal outcomes.

1.Introduction

Employment specialists are professionals who support people with disabilities with finding and succeeding in work by providing a complex spectrum of individualized services from strength assessments to on-site job training. Cimera (2007) indicates that programs providing employment services significantly increase employment rates of people with disabilities. While those without work impairments or disabilities experience a poverty rate of approximately 12%, individuals with work impairments or disabilities experience a considerably higher rate of poverty of 31% (VonSchrader & Lee, 2017). Amongst many reasons, effective employment specialists are critical in disrupting the cycle of poverty and marginalization of individuals with disabilities.

Luecking et al. (2004) indicates that the success of the supported employee “rides on the competence and commitment” of the person supporting them. Low unemployment rates, minimum hiring requirements, and difficulty in maintaining competitive wages make it difficult for employment agencies to hire and retain quality professionals (Hewitt & Larson, 2007). Once hired, agencies are often responsible for providing necessary training to ensure employment specialists have the skills needed to support people with disabilities seeking employment. In addition to the numerous technical competencies required to support people with disabilities in successful employment, the professional must be a chameleon, adapting teaching practices, and acquiring skills unique to different fields (Training Resource Network & Association for Persons in Supported Employment, 2010). The employment specialist must acclimate to the norms of any field in which a supported employee will work. Even if the employment specialist has the knowledge of how to provide quality services, implementation of these practices is not guaranteed as many trainings stay in a binder on a shelf (Fixsen et al., 2005).

Often spread thin, employment specialists juggle sizeable caseloads, changing schedules, administrative tasks, and cumbersome documentation requirements to meet the needs of the people they support (Hall et al., 2018). Given the large volume of factors to consider for each person, in addition to the diverse competencies required to support people with disabilities, it may be challenging to keep all of these balls in the air. In an attempt to condense the volume of information and bridge the gap between research and practice, this article presents accessible, easily understood concepts to consider when facilitating positive outcomes for supported employees. These guidelines, offered as ‘rules,’ include:

1. Do no harm: An employment specialist’s actions, or lack of action, should never harm the supported employee, their relationships or reputation.

2. Don’t be weird: An employment specialist’s soft skills and approach to providing services can impact co-workers’ perception and subsequent relationships with the supported employee.

3. Provide enough, but not too much support: As a facilitator and consultant, knowing that ‘sweet spot’ ensures a person is included into a worksite as typically as possible, while receiving the supports he or she needs to be successful.

4. Do right by the supported employee: An Employment Specialist should use tried and tested practices.

These concepts provide a framework for the employment specialist to use and assess their own actions and skills, feeling confident that they have the power to change the course of employment for the supported employee.

2.The rules

2.1.Do no harm

Never take an action, or omit action, that could cause detriment to the supported employee. Beyond physical or emotional harm, the reputation and perception of the supported employee within the workplace and community should be considered. Employment specialists must think on their feet, assess each situation, and intervene if necessary or step back if possible. Conscientiously taking a step back before making a phone call to a supervisor, or pausing to reflect before providing hand over hand prompts may ensure preservation of the supported employee’s reputation in the workplace. Professionals may ask themselves,

• Will this action make the employee stand out?

• Could this negatively affect the employee’s relationship with coworkers?

• Could this action negatively affect the perception and reputation of the employee?

In addition to these questions, there may be other facets to consider based on the needs of the person being supported. Beyond the way supports are provided, the employment specialist must also consider whether he or she should intervene. To support inclusion in the workplace and become a valuable team member, the supported employee must appear competent and successful. A critical piece of providing supports in a workplace is facilitating opportunities for independence. If a person is unable to complete a task, the professional should step in and provide support through appropriate and effective ways to ensure the supported employee continues to appear as a valuable team member, competently completing tasks. For example, if during conversation, the supported employee struggles to find an answer to her colleague’s question, the employment specialist provides a prompt to facilitate the supported employee’s answer rather than answering for him or her.

2.2.Don’t be weird

Within this conversation, being weird means being ‘atypical’ or ‘unusual’ from the norms of a workplace. Given the diverse fields an employment specialist enters, there are times when a person may unintentionally operate in a different way than typical for a given workplace. This may happen because an employment specialist is unfamiliar with norms of a workplace, or perhaps he or she operates within the customs of the human services field (Callahan & Garner, 1997; Hagner & DiLeo, 1993). When reflecting, an employment specialist may remember that he was a peppy, enthusiastic person in colorful clothes, in a sea of serious khaki-wearing IT professionals. An employment specialist may recall standing right next to Tony each day, even though Tony works successfully with the support of a colleague. An employment specialist may use human services lingo at a business: she tells a business owner, “Lydia is in Discovery through Vocational Rehabilitation (VR), but will receive extended services through Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) funding.” Unless the employment specialist is in tune with what is considered typical within a given business, it is unlikely he or she will effectively support inclusion and relationship development for the supported employee (Hagner & DiLeo, 1993; Rogan, Hagner, & Murphy, 1993). Thus, professionals should be conscientious and observant to incorporate typical practices when entering a new workplace to ensure effective supports are provided.

When determining whether an action might be considered ‘weird,’ focus should be brought to what is typical for that particular workplace. Contemplate the following questions: “If I were helping my brother, would this be weird?” and “What is a typical way this would be done in this workplace?” Researchers tell us that it is best when a supported employee learns in typical ways that any other employee would learn the job, and rely on whoever would typically teach the job. When professionals facilitate and support ways that are more typical, supported employees have higher levels of social interactions and higher wages (Mank, Cioffi, & Yovanoff, 1997). In other words, if a person can learn from the typical orientation and new employee procedures, the employment specialist has no need to provide auxiliary support. When evaluating whether an action is weird or not, consider the following factors:

• Physical proximity: Consider ways to physically distance yourself when possible.

• Time present onsite: Be present only when necessary. If someone needs support at the beginning of a shift, but can get through the rest of the shift with natural supports, excuse yourself when appropriate.

• Where and when instruction and/or support takes place: Think about the typical culture of instruction and support. If an employee does not typically receive feedback on hygiene at work, the person you are supporting should not receive that feedback at work either.

These factors affect how other people, such as colleagues and supervisors, perceive the supported employee. Whether or not an employment specialist is ‘weird’ can shape and impact how the supported employee will be viewed, how they will bond with their colleagues and natural supports, and ultimately can impact their success at work. Consider the following situations in Table 1.

Table 1

Considering Context of Support. In different situations, the way the employment specialist provides supports affects the supported employee. The following provide examples

| Potentially Harmful | Supporting Competence |

| •Give feedback on hygiene at the work | •Give feedback on hygiene at home |

| •When a coworker asks a question, answering for the supported employee | •When a coworker asks a question, support or prompt the employee to answer |

| •Create a poster board visual support where you post cartoon character stickers for reaching productivity | •Create a pocket sized visual support where the employee can check off an item when completed |

2.3.Provide enough, but not too much support

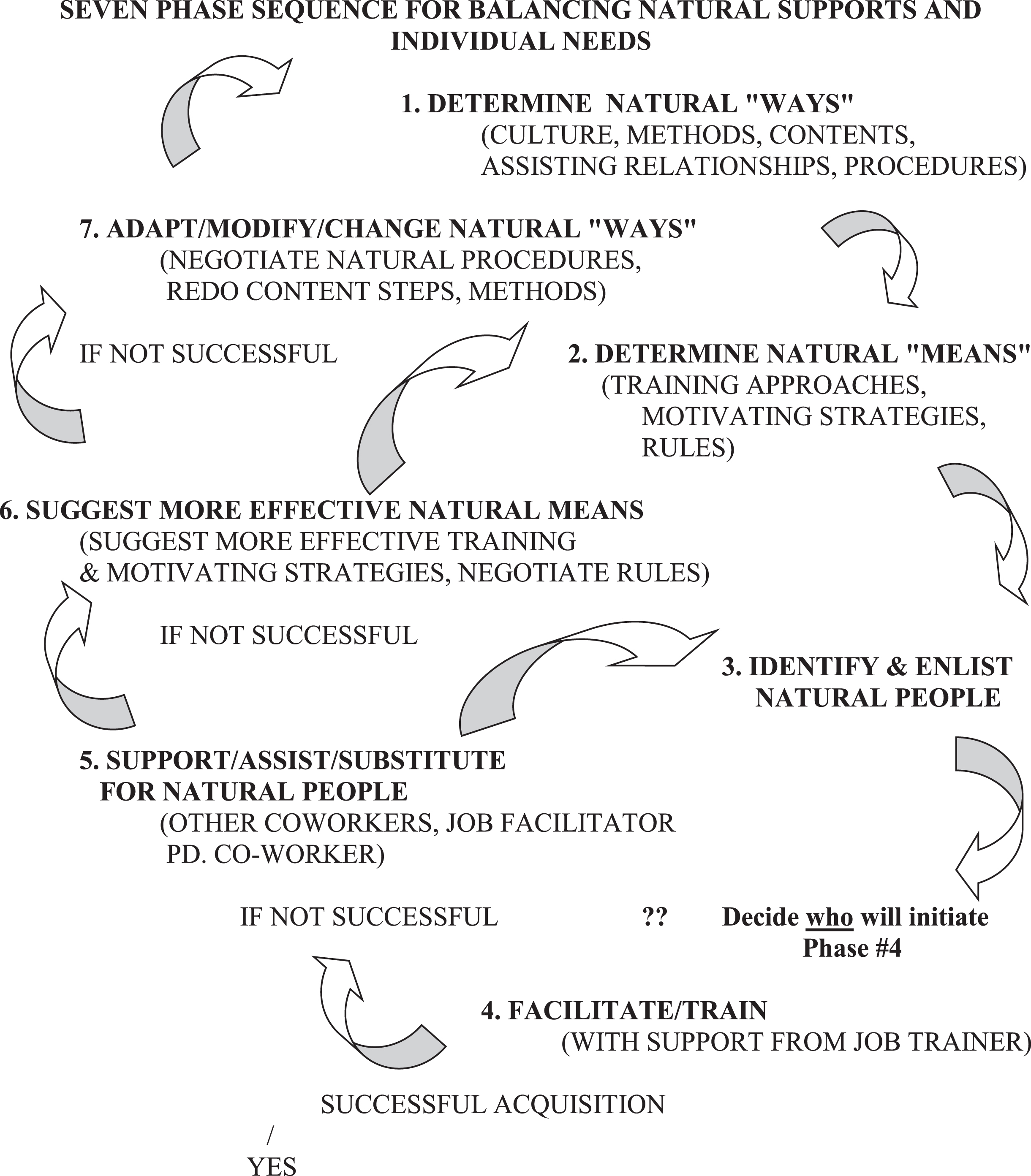

In some cases, typical ways of training may not be effective, or a supported employee may be unable to complete the steps prescribed for a given task. Sometimes a person may need some extra help from a coworker or the employment specialist, or an accommodation or modification is needed. Whatever the change or support, it is the role of the employment specialist to facilitate a different way of learning or doing. Figure 1 outlines the Seven Phase Sequence (Callahan, 2011; Callahan & Garner, 1997). This sequence guides the employment specialist to determine how best to intervene while retaining as much typical support as possible and at the same time minimizing artificial supports.

Fig.1

The Seven Phase Sequence (provided with permission from Callahan, 2011). The Seven Phase Sequence guides an employment specialist in providing enough, but not too much support.

The supported employee should receive supports as typically as possible, with the employment specialist augmenting only when necessary and only as much as needed. As Fig. 1 demonstrates, typical ways and means are first used and considered. When a supported employee learns through typical ways and means, this helps him or her become integrated and stable in a job while building relationships that will support him or her throughout their tenure at the business. If steps 1 through 3, the typical ways or teaching methods, are not effective, the employment specialist puts on a consultant hat to determine the most appropriate intervention by following the next steps of the sequence.

The following steps describe deviations from the norm. Step 4 suggests that after natural ways and means, the employment specialist assists through observation, feedback, and suggestions to natural supports. These suggestions offer more effective ways of teaching and working with the supported employee. Employment specialists facilitate natural supports within the workplace, focusing on building the internal training capacity within the business. Examples of this step might include slowing down instruction, explaining a step in a different way, or modeling a prompting delay that ensures a person has sufficient time to respond.

In Step 5, the employment specialist facilitates the use of a substitute teacher. In this situation, the employment specialist will first ask who would typically step in if the trainer were unavailable. Preferably, the substitute comes from the business. Alternatively, the employment specialist or someone similar steps in. Step 6 examines how the employer typically teaches and motivates employees. Perhaps the employment specialist supplements verbal instructions with visual supports to teach the multi-step process of ironing a shirt. In a different situation, the employment specialist may model clocking out, in addition to the written instructions next to the time clock. Lastly, the employment specialist may consider adapting, modifying, or negotiating the way work tasks are typically performed. As the employment specialist tries to retain as many of the typical features as possible, this is the last option considered.

2.4.Do right by the supported employee

Employment specialists should use strategies and supports that have the greatest likelihood of success, which may include supports already known to be successful with the particular supported employee, and practices that researchers have proven to be effective. While employment specialists must spend more upfront time planning and developing strategic supports, this time is well spent when weighed against failure, time reacting to unanticipated challenges, and wasting limited funding.

From the initial intake meeting through the job development process, the professional learns what works for the person they are supporting, including effective teaching strategies and optimal environmental conditions. This may occur from talking with people who know the job seeker well, observation, and engaging in activities that identify strengths (Callahan et al., 2009). In other words, from the beginning, the employment specialist should be thinking about and verifying what strategies and supports are most effective for the supported employee.

Employment specialists can proactively identify win-win strategies for the supported employee and business by completing a job analysis prior to a person beginning work. A job analysis provides a thorough, in-depth look at multiple facets of a workplace and job, including workplace culture, job tasks, as well as tasks needed to operate successfully within the workplace (Callahan & Mast, 2004). While many people secure jobs because they have the skills to complete the primary tasks in their jobs, a number of tasks and cultural aspects may not be readily apparent, but are critical for inclusion and long-term retention. By completing a job analysis, the employment specialist confirms that the workplace will be a good fit for the person they support, and proactively identifies areas for additional supports. Being preemptive ensures that the supported employee receives the training they need starting from the first day. In other words, the employment specialist can be prepared to support the trainer during orientation, and be proactive in facilitating the supported employee participating in happy hour after work too. The job analysis provides a process for identifying potential skill gaps and support needs, and proactively identify solutions.

There is a wide body of research outlining a number of programs and practices that are effective in teaching and supporting people with disabilities. However, implementation of these practices is often limited (Fixsen et al. 2005). If employment specialists incorporate these practices into their repertoire, they will likely have the skills to teach adults with complex learning needs effectively. In contrast, employment specialists who are not trained often focus on task completion and may resort to completing the job themselves (Parsons, Reid, Green, & Browning, 2001; Towery, Parsons, & Reid, 2014). Providing quality services that are effective for the supported employee is both most efficient for the employment specialist’s time, and comes with the greatest likelihood for supported employee success.

3.Conclusion

This article presents four ‘rules’ to guide employment specialists to quality service delivery. With so many expectations, processes, and points to remember, the hope is these ‘rules’ are easy to digest and remember. Employment specialists can use these concepts to monitor their actions while working with supported employees.

Although directed toward employment specialists, program managers and leaders may use these concepts as teaching strategies, and an opportunity to evaluate the supports and training offered to staff. Leaders should support employment specialists by providing both opportunities for training, as well as supports and strategies to ensure that these trainings do not end up as binders on a shelf. Finally, managers should consider policies and procedures within the agency that align with providing quality services, and maximize employment specialists’ opportunity to provide quality work.

Employment specialists have the power to facilitate and change the course of a person’s life. Integrated employment can lead to an expanded social network, higher wages, a passion, and a career. While the employment specialist can make a positive impact, the professional must also take responsibility and acknowledge their role in unsuccessful ventures. If a job fails, or an employee struggles to learn a skill or fit into the culture of the business, the employment specialist and support team must claim responsibility and not blame the supported employee. If something does not go right, the team should ask, “What can we do differently next time?”

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors worked at the Indiana Institute on Disability and Community, at Indiana University, while developing this manuscript. The authors would like to thank Dr. Mary Held and Jackie Tijerina for their assistance and support in the development of this manuscript.

References

1 | Callahan, M. ((2011) ). Natural supports: A delicate balancing act. Retrieved October 29, 2018 from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57fa78cd6a496306c83a2ca7/t/5830f982d1758e26bb3ff82d/1479604611932/Natural+Supports.pdf |

2 | Callahan, M. , & Garner, B. ((1997) ). Keys to the workplace: Skills and supports. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. |

3 | Callahan, M. , & Mast, M. ((2004) ). Job analysis: A strategy for assessing and utilizing the culture of work places to support persons with disabilities. Retrieved October 29, 2018 from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57fa78cd6a496306c83a2ca7/t/58b456ec725e2511575250d5/1488213740992/Job+Analysis+Article+8-14-2015.pdf |

4 | Callahan, M. , Shumpert, N. , & Condon, E. ((2009) ). Discovery: Charting the course to employment. Gautier, MS: Marc Gold & Associates. |

5 | Cimera, R. E. ((2007) ). The cost-effectiveness of supported employment and sheltered workshops in Wisconsin: FY 2002-2005. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 26: (3), 153–158. |

6 | Fixsen, D. L. , Naoom, S. F. , Blase, K. A. , Friedman, R. M. & Wallace, F. ((2005) ). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network (FMHI Publication #231). |

7 | Hagner, D. , & DiLeo, D. ((1993) ). Working together: Workplace culture, supported employment, and persons with disabilities. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books. |

8 | Hall, A. , Butterworth, J. , Winsor, J. , Kramer, J. , Timmons, J. , & Nye-Lengerman, K. ((2018) ). Building an evidence-based, holistic approach to advancing integrated employment. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 43: (3), 207–218. |

9 | Hewitt, A. , & Larson, S. ((2007) ). The direct support workforce in community supports to individuals with developmental disabilities: Issues, implications, and promising practices. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13: , 178–187. |

10 | Luecking, R. G. , Fabian, E. S. , & Tilson, G. P. ((2004) ). Working relationships: Creating career opportunities for job seekers with disabilities through employer partnerships. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. |

11 | Mank, D. , Cioffi, A. , & Yovanoff, P. ((1997) ). Analysis of the typ-icalness of supported employment jobs, natural supports, and wage and integration outcomes. Mental Retardation, 35: (3), 185–197. |

12 | Parsons, M. B. , Reid, D. H. , Green, C. W. , & Browning, L. B. ((2001) ). Reducing job coach assistance for supported workers with severe multiple disabilities: An alternative off-site/on-site model. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22: , 151–164. |

13 | Rogan, P. M. , Hagner, D. , & Murphy, S. ((1993) ). Natural supports: Reconceptualizing job coach roles. Journal ofthe Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 18: , 275–281. |

14 | Towery, D. , Parsons, M. B. , & Reid, D. H. ((2014) ). Increasing independence within adult services: A program for reducing staff completion of daily routines for consumers with developmental disabilities. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 7: , 61–69. |

15 | Training Resource Network, Inc. and Association for Persons in Supported Employment ((2010) ). APSE supported employment competencies. Retrieved October 29, 2018 from https://www.apse.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/APSE-Supported-Employment-Competencies11.pdf |

16 | VonSchrader, S. , & Lee, C. G. ((2017) ). Disability statistics from the current population survey (CPS). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Yang Tan Institute (YTI). Retrieved from www.disabilitystatistics.org |