Work–life balance: Does age matter?

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Work-life balance is a priority of EU policies but at the same time demographic change affects the labour market. Employers have to deal with the ageing of their employees and adjust human resource management to maintain their competitiveness.

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of the article is to answer research questions: whether the age of workers determines their assessment of the work-life balance, and whether there is a relationship between the worker’s age and their assessment of the activities undertaken by their employer to provide them with work-life balance.

METHODS: The article is based on the results of surveys conducted among 500 employees of the SME sector from Finland, Lithuania and Sweden.

RESULTS: The results identified a statistically significant difference: employees representing older age groups are more likely to indicate the maintenance of WLB; older workers more frequently do not agree that all workers have equal opportunities to benefit from flexible solutions aimed at ensuring the maintenance of WLB.

CONCLUSIONS: The results can be the inspiration for the decisions and actions of employers in the field of personnel management and for creating workplace conditions encouraging senior workers to continue working, even upon becoming entitled to old-age pension.

1Introduction

People change with age: their physicality, behaviour as well as perception and evaluation of certain phenomena change. Due to the progressive ageing of the global population and the increasing proportion of older people in the total population [1], more and more attention is paid to the analysis and description of the specific characteristics, attitudes and behaviours of older people in the literature [2–5]. Issues particularly interesting for researchers include questions concerning the sense of happiness, life satisfaction and self-esteem of welfare as a result of the work-life balance achieved by the individual [6–8].

In economic terms, the ageing population is primarily a real threat to the stability and sustainability of the labour market and the competitiveness and innovativeness of the economies of individual countries. The economists’, social scientists’ and politicians’ interest in issues related to motivation and behaviour of seniors is therefore closely connected with the search for new opportunities of extending the period of economic activity of this group [9] and using the potential of knowledge and experience held by older people in enterprises [10]. The results of research on the factors influencing the decisions of people of non-mobile and old age to continue work (despite obtaining pension rights) or withdraw from the labour market point to three main groups of such factors [11]: a) individual, resulting from motivation, family situation, economic situation etc., b) depending on the conditions prevailing in the workplace, as well as c) related to the general legal, economic and social environment of a given country. Fraser et al. [12] supplement the list of factors that influence the seniors’ decisions about the future career with individual psycho-physical conditions (age-related decline in health, physical and cognitive functions, perception of stress) or the level of adaptation of their knowledge and experience to the current labour market conditions.

The authors of this article analysed the work-life balance perceived by the employees at the individual level and how it affects job satisfaction and its continuation in old age. The purpose of the analysis was to decide whether the age of workers influences their assessment of the work-life balance level reached by them, and whether there is a relationship between the worker’s age and their assessment of the activities undertaken by their employer to provide them with work-life balance. The intention of the authors was that the results be the inspiration for the decisions and actions of employers in the field of personnel management and for creating workplace conditions encouraging senior workers to continue working, even upon becoming entitled to old-age pension.

2Work-life balance – overview of the basic issues

Work-life balance (WLB) constitutes a development of some earlier theories – i.e. work-family conflict [13] and work-family balance [14] associated with reconciling the different social roles that a human plays during their lifetime. In a broader sense, the notion reflects the issue of preserving the balance between work and the rest of the spheres of human activity [15–17]. Kirchmeyer [18] defines the WLB as the ability to simultaneously achieve one’s goals and feel satisfaction in all spheres of life. In turn, according to Greenblatt [19], it is an acceptable level of conflict between the work-related needs and non-professional spheres.

Issues related to achieving WLB are examined in the subject-matter literature on three levels: individual, organizational, and on the level of the society as a whole.

On the individual level, the WLB means the ability to join work with other dimensions of human life: home, family, health, social activity, private interests, etc. [20, 21]. From this perspective, WLB provides psychological well-being, high self-esteem, satisfaction, and overall sense of harmony in life of an individual [22, 23]. Individuals keeping the balance between work and personal life are happier, healthier and more creative [24] – they satisfy their desire for prosperity and the feeling of accomplishment and satisfaction [25]. Arott [26] adds that only successful dealing with three areas of life at the same time (in the family, in the workplace and in local communities) provides an individual with appropriate development and psychological balance. It should be emphasized at this point, however, that the equilibrium point is not the same for everyone, and the reconciliation of professional and non-professional life is made possible by the appropriate organization of time and support from family [27] and colleagues [28].

At the level of organization, the work-life balance means appropriate management system and personnel policy [29] conducive to maintaining the balance by the employees. It is also the organization’s use of solutions aimed at improving the quality of work and life [30]. From the point of view of the organization, the employees’ WLB means more opportunities for its development, also through an increase in productivity and innovation [31]. The instruments most commonly offered by employers to help employees maintain work-life balance include [32]:

– more flexible forms of work and working time organization, as well as some non-standard forms of employment (outsourcing and contracting work, temporary work, task-based working time, on-call work, equivalent working time, substitution or job-sharing),

– various types of leaves and allowances and exemptions from obligations of work, provided to the employee because of their need to fulfil family responsibilities,

– benefits realized in various forms by the employer for employees who use alternative forms of care for dependents (e.g. a company kindergarten),

– bonuses (financial and non-financial) to the employees who are forced to reconcile work and caring responsibilities.

In the broadest sense – at the level of society – the realization of the idea of work-life balance means such an organization of the labour market that improves the ease of finding work and increases the sense of security of employment [30]. The development of WLB at the society level may be associated with the introduction of specific formal solutions by the state and its agencies (within the broader labour market policies or the so-called ‘pro-family policy’) or based on the initiatives undertaken by the institutions forming the labour market (including the entrepreneurs themselves), resulting from the managers’ high awareness of work-life-balance subject. The first case relates to the so-called European model, of a social and obligatory nature, the functioning of which is based on legal regulations and social dialogue. It is focused on ‘pro-family’ policy and the development of atypical employment and work organization. The second perspective is, in turn, dominated by employers’ voluntary actions aimed at shaping the WLB, known as work-life programmes – this approach is referred to as ‘the American model’ in the subject-matter literature. This model is focused on attracting employees who are valuable for the company, retaining them, as well as creating conditions conducive to achieving the best working conditions and development [33].

Lack of or insufficient level of WLB at the individual, organization and society levels has several negative consequences in each of these dimensions (cf. Fig. 1). The persistent deficits of WLB can lead in the long term to [34]:

– at the individual level – the individual’s permanent withdrawal from the labour market, and even social exclusion,

– in the perspective of the organization – limited access to skilled workers, increased labour costs, as well as reduced production capacity and competitiveness of the sector,

– for society – a threat to public finance sustainability, slowing the pace of development and reducing the competitiveness of the economy.

2.1Work-life balance at the individual level

Striking a balance between work and private life is a challenge for any economically active individual, and the level of such equilibrium is determined on an individual basis. Based on the results of research it can be stated that the subject-matter literature provides list of the most commonly mentioned determinants shaping the WLB of individuals. These include: family situation, working conditions and economic aspects (cf. Fig. 2). The most exposed to the WLB disorders include those with children, as well as caring for the elderly and disabled [35]. In addition, the following groups are listed as being at risk: women, individuals at serious risk of losing their job and remote chances of finding comparable work, the disabled, the low-qualified, the self-employed.

Also some personality traits of individuals influence the balance between work and family life. These include, among others: high neuroticism, low level of tolerance and the ability to compromise, as well as low self-perception of own effectiveness. It was also showed that the work-personal life conflict is exacerbated by workaholism [36].

The literature of the subject, as well as expertise and statistical statements drawn up by international organizations [37, 38] relatively rarely take into account the individual’s age as a factor that generates conflict between work and family life. Crompton and Lyonette [39] prove, however, that younger people (due to parental responsibilities, the initial phase of career development, etc.) are more likely than the older ones to report the occurrence of WLB disruptions. This is also confirmed by the results of the Quality of Life Survey [40]. From a study carried out among New Zealanders in 2008, it appears that the working people aged 55–64 years and 65 years or more belong to the most satisfied with the achieved WLB among all age groups.

According to Yeandle [8] and Phillipson [41], the achievement (or failure to achieve) a desired level of WLB by older workers is influenced by a rather broadly based public policy determining the position of individuals of non-mobile and retirement age than their age itself. Penner et al. [42] links the possibility of WLB growth among the seniors with activities related to increasing the labour market flexibility and its better adaptation to the needs of this group. In turn, Auer and Speckesser [43] point out that the problems with achieving proper WLB by older people most often stem from the stereotypical perception and discrimination of this group in society and in the workplace.

3The methodology of research

The article is based on the results of a survey conducted within the framework of the “Best Agers Lighthouses – Strategic Age Management for SME in the Baltic Sea Region” international project1.

The achievement of the main goal of the project, i.e. the implementation of specific activities in the field of age management in selected SMEs and public organizations (Lighthouse Organizations) was preceded by a series of scientific studies designed by the scientific partners of the project: Aalto University (FI) and Gdansk University of Technology (PL).

One of the stages of the implementation of the project was conducting questionnaire research among the employees of the Lighthouse Organizations. On the one hand, the purpose of the questionnaire was to study the employees’ work engagement, health and ability to function. On the other hand, the questionnaire served to analyse the employees’ opinions about age management in their organizations, as well as their views of themselves and their attitude towards work and retirement. There were altogether 67 questions in the questionnaire divided into six different categories related to the above-mentioned themes of the study. The questionnaire was translated into national languages, so that all the respondents could answer the questions in their mother tongue and for example terminological confusion could be avoided. All answers to the questionnaire were collected in one database and analysed by the ScientificPartners.

The study was carried out from June to November 2013 and covered all the employees of the Lighthouse Organizations, a total of 509 individuals. Upon verification of the completeness and correctness of responses 440 questionnaires were enrolled to further analysis, of which 253 (57%) were from women and 187 (43%) from men. Among the questionnaire survey participants, 113 (26%) came from Lighthouse Organizations from Finland (FI), 265 (60%) from Lithuania (LT) and 62 (14%) from Sweden (SE). The characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The age of respondents ranged from 21 to 70 years, the mean age was 44.3 years and the median 43 years (cf. Table 2).

The article gives the conclusions of the analysis of some of the results of the questionnaire survey, narrowed to the issue of evaluation of the degree of satisfaction with the WLB achieved by the employees of the Lighthouse Organizations. The aim of this part of the study was to obtain answers to two basic research questions:

– whether the age of employees has an impact on their evaluation of achieved level of WLB,

– whether there is a relationship between age and the assessment of activities undertaken by employers to provide workers with work-life balance.

In the statistical analysis of the results, theKruskal-Wallis test was employed. This is a non-parametric alternative for the one-factor analysis of variance in the inter-group set-up used to compare three or more samples. The Spearman’s R correlation analysis was used to express the co-dependency (statistical significance) between the examinedvariables.

4The survey results

In order to obtain answers to the research questions formulated above, respondents were asked to comment on the following statements:

– Q 46: “I maintain well a balance between my work and private life”,

– Q 28: “In our organization all employees have equal opportunities for flexible solutions to the work-life balance”.

In regard to the first statement: “I maintain well a balance between my work and private life” the subjects could indicate one of the five answers: “I agree”, “I somewhat agree”, “I somewhat disagree”, “I disagree” and “I do not wish to answer”. The vast majority, 83% of surveyed employees, agreed with the statement suggesting that they maintain a balance between professional and private life (the aggregated answers “I agree” (46%) and “I somewhat agree” (37%)). Only 15% of all respondents felt that they do not maintain such balance (aggregated answers “I somewhat disagree” (10%) and “I disagree” (5%)). In addition, 2% of respondents expressed no willingness to respond.

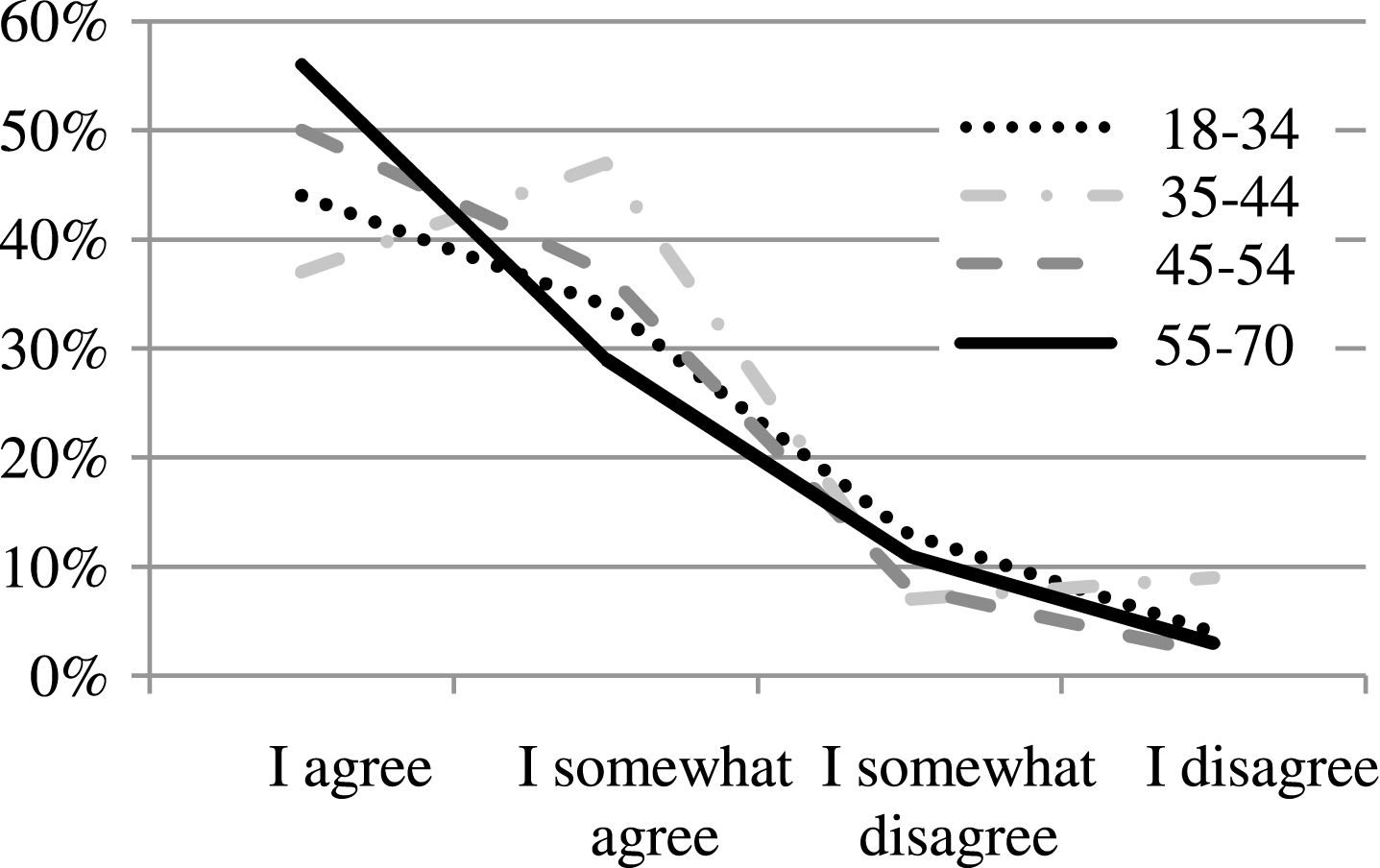

To verify the first research question, “Does the age of employees influence their assessment of the achieved level of WLB?”, the obtained results were analysed in terms of respondent age (cf. Table 3). While the main trend of the distribution of results has been preserved, i.e. the vast majority of respondents agree with the statement that they keep a balance between work and private life, there are, however, some variations in the frequency of indications “I agree” and “I somewhat agree” depending on the age of the respondents. The respondents from the 35–44 years age group indicate the answer “I agree” less frequently (37%) than respondents from the 55–70 years age group (56%). This means that in the oldest group of workers proportionally more respondents than in the case of workers aged 35–44 years believe that they achieve a balance between work and private life. In addition, workers aged 35–44 years more often (9%) than the others indicate the answer ”I disagree”, denoting the lack of WLB in their lives. Moreover, the aggregated results of the youngest respondents aged 18–34 years in this group indicate that the positive answers are less frequent (78% of aggregate results "I agree” and “I agree somewhat”) than among respondents aged 45–54 years (88%). The above-mentioned dependencies are illustrated in Fig 3.

To determine whether the above-discussed differences in the results are statistically significant, a statistical analysis based on the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed. The test results indicate a statistically significant difference in the way respondents answer according to their age (H (3, N = 440) = 7.82, p = 0.05), with particular emphasis on the differences between the respondents in the 55–70 years and 35–44 years, as well as 55–70 years and 21–34 years age groups.

In addition, the Spearman R correlation analysis showed the statistical significance of a weak positive linear relationship between the age of respondents and their claims related to maintaining WLB (R Spearman = 0.13; p < 0.01). This means that ingeneral, the positive assessment of the balance achieved between work and private life varies depending on the age of the workers. Older workers tend to express more positive assessments.

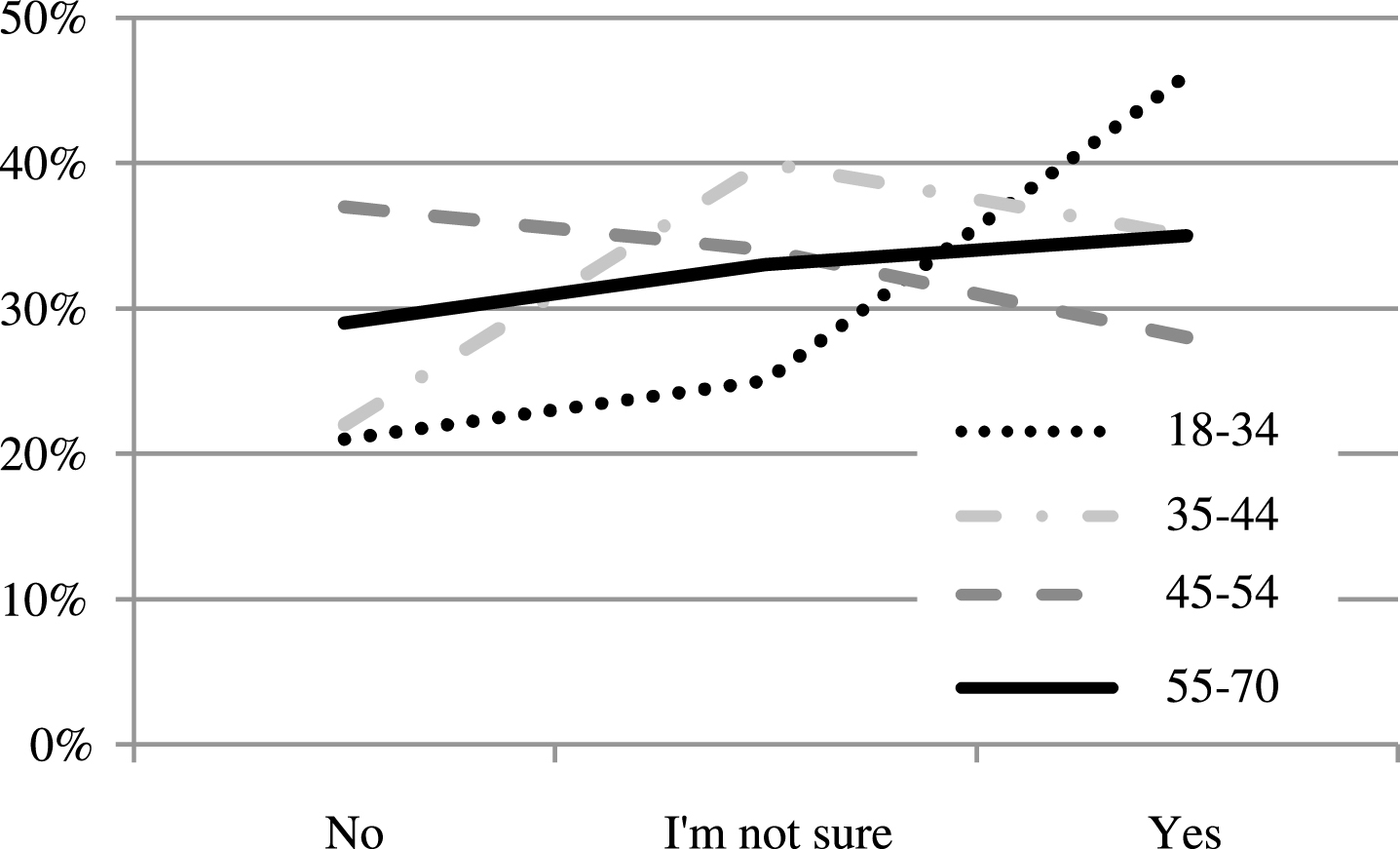

To verify the answer to the second research question, “Is there a relationship between the employee age and their assessment of the actions taken by the employer to provide WLB in the workplace?”, the employees participating in the study were asked to react to the statement: “In our organization all employees have equal opportunities for flexible solutions to the work-life balance”. The respondents marked their responses on the scale: “No”, "Not sure”, “Yes”, “I do not wish to answer”. Of all the answers, 27% were negative assessments related to the statement that at the surveyed employees’ workplace all the workers are provided with equal opportunities to use flexible solutions to maintain a balance between work and private life. 34% of respondents indicated the answer “I’m not sure”, while only 36% the answer “Yes”. In addition, 4% of respondents have decided not to answer. Only one-third of the answers obtained in the context of the statement concerning the working conditions enabling the maintenance of WLB are positive.

The respondent answers were also analysed in relation to the criterion of their age. The Table 4 shows the quantitative and percentage distribution of responses broken down by age groups of the survey participants.

The conducted analysis shows that the age of respondents influences their answers. The youngest workers by far most frequently (46% of respondents in this age group) agreed with the statement that their organisation provides all workers with equal opportunities to benefit from flexible solutions aimed at ensuring the maintenance of a balance between professional and private life. Workers in the older, 35–44 years age group, on the other hand, chose the answers “I’m not sure” (40%) and “Yes” (35%) most often. The workers from the 45–54 years age group, in turn, frequently selected the answers “No” (37%) and “I’m not sure” (34%). In addition, in the oldest group of workers aged 55–70 years the diversity of responses was the smallest and amounted to approximately 6%. The above-mentioned differences are illustrated in Fig 4. To determine whether the above-indicated differences in the results are statistically significant, a statistical analysis based on the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed. The test results confirm a statistically significant difference in the way respondents answer according to their age (H (3, N = 440) = 14.1, p = 0.01), with particular emphasis on the differences between the respondents in the 18–34 years and 35–44 years, as well as 18–34 years and 45–54 years age groups.

In addition, an analysis of the Spearman’s R correlation showed statistical significance of weak negative linear dependence between the age of the respondents and the statement that their organization provides all workers with equal opportunities to benefit from flexible solutions aimed at ensuring the maintenance of WLB. Spearman’s R = –0.13; p < 0.01. This means that this assessment varies depending on the age of the workers and younger workers tend to express more positive assessments.

5Conclusion

In this article, an attempt has been made to answer two research questions: whether the age of workers determines their assessment of the WLB level reached by them, and whether there is a relationship between the worker’s age and their assessment of the activities undertaken by their employer to provide them with WLB. To verify both questions, the results of the research carried out among more than 500 employees of the Lighthouse Organizations (SMEs and public organisations sector enterprises), participating in the “Agers Lighthouses – strategic age management for SME in the Baltic Sea Region” project.

The use of non-parametric methods of statistical analysis made it possible to draw some general conclusions related to the surveyed population:

– the vast majority of staff of the Lighthouse Organizations (83% of the aggregated responses “I agree” and “I somewhat agree”) agrees with the claim that they manage to maintain the WLB;

– employees representing older age groups are more likely than workers from younger age groups to indicate the maintenance of WLB;

– a statistically significant difference in the way respondents answer according to their age, with particular emphasis on the differences between the respondents in the 55–70 years and 35–44 years, as well as 55–70 years and 21–34 years age groups, was shown;

– the surveyed employees assessed the conditions to ensure the WLB in their workplace as worse than their own sense of WLB – only 36% of respondents agreed with the statement that in their organization all workers have equal opportunities to benefit from flexible solutions aimed at ensuring the maintenance of WLB;

– in the case of employees’ assessment of the WLB conditions created by the organization the impact of age was also demonstrated – older workers more frequently than the younger ones do not agree that all workers have equal opportunities to benefit from flexible solutions aimed at ensuring the maintenance of WLB.

The responses received for both of research questions analyzed in the article (due to the questionnaire design) do not exhaust authors’ scientific interests. They believe the further research is required. Among the outstanding issues are:

– why only one third of respondents agreed with the statement that in their organization all workers have equal opportunities to benefit from flexible solutions aimed at ensuring the maintenance of WLB,

– why older workers are more likely than younger ones to not agree that all workers have equal opportunities to benefit from flexible solutions aimed at ensuring the maintenance of WLB,

– who, in employees opinion (including the age criteria), benefits more and who benefits less from flexible solutions aimed at ensuring the maintenance of WLB,

– what solutions should be developed to ensure WLB in the workplace for all employees (regardless their age).

The analysis presented in the article did not take into account the diversity of the answers given by the respondents according to the type of organization in which the surveyed employees worked and the state in which the organization functioned.

Despite having used some simplifications and incomplete picture of employees’ assessment of benefiting from flexible solutions aimed at ensuring the maintenance of WLB, the results obtained in the course of the investigation correspond to the those referred to in the theoretical considerations [39, 40]. They confirm that older individuals represent a higher level of satisfaction with the achieved work-life balance than the younger ones.

In the context of the ongoing exploration of methods and tools that would encourage older workers to continue employment (conducted within both the theoretical and the practical dimension of enterprise operation [44–48]), the results also have practical value. They show employers that conditions created in the workplace have a significant impact (greater than in the case of young people) on the maintenance of balance between work and personal life of older workers. Through actions aimed at increasing the availability of flexible solutions allowing for the maintenance of work-life balance employers gain the opportunity to influence their close-to-retirement-age employees’ decisions about delaying the end of their professional activity. In addition, the obtained results reflect the age-related variation of assessments formulated by the workers, related to activities undertaken in the organization by its management. Such variation is associated with the different needs and expectations of employees representing different age groups. Replies related to methods of managing an organization employing workers of different ages – having different needs – are provided by the concepts of age management [49–51] and diversity management [52, 53]. In view of the results presented in this article, the employers managing employee teams having diverse age structure should consider the implementation of the instruments proposed by researchers in both fields of management: age and diversity.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Notes

[1] 1Best Agers Lighthouses - Strategic Age Management for SME in the Baltic Sea Region, a project co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund within the framework of the Baltic Sea Region Programme 2007–2013. A project implemented by a consortium of 12 partners from 6 countries of the Baltic Sea Region; http://www.best-agers-lighthouses.eu/

Acknowledgments

This paper was written as part of the project Best Agers Lighthouses – Strategic Age Management for SME in Baltic Sea Region, part-financed by the European Union (European Regional Development Fund) – Baltic Sea Region Programme 2007–2013. Research paper financed by Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education from the funds for science 2013-2014 for co-financed international projects.

REFERENCES

[1] | World Population Ageing 2013. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, United Nations. [cited 2014 Sep 12] Available from http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf |

[2] | Fealy G , McNamara M , Pearl M , Lyons T , Lyons I . Constructing ageing and age identities: A case study of newspaper discourses. Aging and Society (2012) ;32: (01):85–102. |

[3] | Lyons I , editor. Public Perceptions of Older People and Ageing: A literature review. Dublin: National Centre for Protection of Older People; (2009) . |

[4] | Montepare JM , Lachman ME . You’re only as old as you feel. Self-perceptions of age, fears of aging, and life satisfaction from adolescence to old age. Psychology and Aging (1989) ;4: :73–8. |

[5] | Schafer MH , Shippee TP . Age identity, gender, and perceptions of decline: Does feeling older lead to pessimistic dispositions about cognitive aging? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences (2010) ;65B: :91–6. |

[6] | Gardiner J , Stuart M , Forde Ch , Greenwood I , MacKenzie R , Perrett R . Work–life balance and older workers: Employees’ perspectives on retirement transitions following redundancy. The International Journal of Human Resource Management (2007) ;18: (3):476–89. |

[7] | MacInnes J . Work–life balance in Europe: A response to the baby bust or reward for the baby boomers? European Societies (2006) ;8: (2):223–49. |

[8] | Yeandle S . Older workers and work-life balance. Sheffield Hallam University: Sheffield; (2005) . |

[9] | Mott V . Working Late: Exploring the Workplaces, Motivations, and Barriers of Working Seniors. In: Rocco T , Thijssen J , editors. Older workers, new directions. Employment and development in an ageing labour market Miami: Florida International University, Center for Labor research and Studies; (2006) :158–67. |

[10] | Richert-Kaźmierska A . Międzypokoleniowy transfer wiedzy w przedsiębiorstwach. Uwarunkowania rynkowe rozwoju mikro, małych i średnich przedsiębiorstw. Mikrofirma. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego (2012) ;695: :79–88. |

[11] | Richert-Kaźmierska A , Stankiewicz K . Czynniki motywujące osoby w wieku okołoemerytalnym do wydłużonej aktywności zawodowej. In: Witkowski S , Stor M , editors. Sukces w zarządzaniu kadrami. Elastyczność w zarządzaniu kapitałem ludzkim. Problemy zarządczo-psychologiczne. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu; (2012) ;236–46. |

[12] | Fraser L , McKenna K , Turpin M , Allen S , Liddle J . Older workers: An exploration of the benefits, barriers and adaptations for older people in the workforce. WORK: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation (2009) ;33: :261–72. |

[13] | Kahn RL , Wolfe DM , Quinn RP , Snoek JD , Rosenthal RA . Organizational Stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. New York: Wiley; (1964) . |

[14] | Hill EJ , Hawkins AJ , Ferris M , Weitzman M . Finding an extra day a week: The positive influence of perceived job flexibility on work and family life balance. Family Relations (2001) ;50: (1):49–65. |

[15] | Fisher GG . Work/personal life balance: A construct development study. Doctoral Dissertation. Bowling Green State University, USA ((UMI No 3038411); (2001) . |

[16] | Hobson CJ , Delunas L , Kesic D . Compelling evidence of the need for corporate work/life balance initiatives: Results from a national survey of stressful life events. Journal of Employment Counseling (2001) ;30: :38–44. |

[17] | Zulch G , Stock P , Schmidt D . Analysis of the strain on employees in the retail sector considering work-life balance. WORK: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment, and Rehabilitation (2012) ;4: :2675–82. |

[18] | Kirchmeyer C . Work-life initiatives: Greed or benevolence regarding workers’ time. Trends in organizational behaviuor (2000) ;7: :79–94. |

[19] | Greenblatt E . Work-life balance: Wisdom or whining. Organizational Dynamics (2002) ;31: (2):177–93. |

[20] | Daniels L . What does Work-Balance Mean? [cited 2014 Sep 12] Available from: www.W-LB.org.uk |

[21] | Reece KT , Davis JA , Polatajko HJ . The represenatations of work-life balance in Canadian newspapers. WORK: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation (2009) ;32: :431–42. |

[22] | Clarc SC . Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Journal of Human Relations (2000) ;53: :747–70. |

[23] | Clarke MC , Koch LC , Hill EJ . The work-family interface: Differentiating balance and fit. Family and Consumer Science Research Journal (2004) ;33: :121–40. |

[24] | McGee-Cooper A . Time Management for Unmanageable People. Dallas: Ann McGee-Cooper & Associates; (1983) . |

[25] | Robak E . Kształtowanie równowagi między pracą a życiem osobistym pracowników jako istotny cel współczesnego zarządzania zasobami ludzkimi. In: Lewicka D , Zbiegień-Maciąg L , editors. Wyzwania dla współczesnych organizacji w warunkach konkurencyjnej gospodarki. Kraków: Wydawnictwa AGH; (2010) :205–20. |

[26] | Arott D . Corporate Cults New York: Amacom; 2000. |

[27] | Arcimowicz K . Relacje partnerskie w rodzinie: Korzyści z nich płynące i konieczne działania w Polsce na rzecz ich poprawy. In: Sadowska-Snarska C , editor. Równowaga: Praca-życie-rodzina Białystok: Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Ekonomicznej w Białymstoku; (2008) :287–306. |

[28] | Połaska M , Berłowski P , Godlewska J , Rzewuska M . Równowaga praca – życie. Warszawa: Wolters Kluwer; (2013) . |

[29] | Tipping S , Chanfreau J , Perry J , Tait C . The fourth work-life balance employee survey. Employment Relations Research Series 122 London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills; (2012) . |

[30] | Borkowska S , editor. Przyszłość pracy w XXI wieku. Warszawa: IPiSS; (2004) . |

[31] | Naithani P . Overview of Work-Life Balance discourse and its relevance in current economic scenario. Asian Social Science (2010) ;6: (6):148–55. |

[32] | Skarzyński M . Work-life balance. Poradnictwo interdyscyplinarne Białystok: Białostocka Fundacja Kształcenia Kadr; (2007) . |

[33] | Borkowska S . Równowaga między pracą a życiem pozazawodowym. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Oeconomica (2010) ;240: :18–9. |

[34] | Gornick JC , Hegewish A . The Impact of Family-Friendly Policies on Women’s Employment, Outcomes and on the Costs and Benefits of Doing Business. Washington: A Commissioned Report for the World Bank; (2010) . |

[35] | Kotowska I , Matysiak A , Styrc M . Życie rodzinne i praca. Drugie europejskie badanie jakości życia. Luxembourg: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Publications Office of the European Union; (2010) . |

[36] | Greenhaus JH , Beutell NJ . Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review (1985) ;10: :76–88. |

[37] | Better Life Index, OECD. [cited 2014 Sep 12] Available from: http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/work-life-balance/ |

[38] | Eurofund. [cited 2014 Sep 12] Available from: https://eurofound.europa.eu/areas/worklifebalance/index.htm |

[39] | Crompton R , Lyonette C . Work-life balance in Europe. GeNet Working Paper. London: City University; (2005) ;10. |

[40] | Quality of Life Survey 2008. [cited 2014 Sep 12] Available from: http://socialreport.msd.govt.nz/paid-work/satisfaction-work-life-balance.html. |

[41] | Phillipson C . Older workers and retirement: Critical perspectives on the research literature and policy implications. Social Policy & Society (2004) ;3: (2):189–95. |

[42] | Penner RG , Perun P , Steuerle E . Letting older workers work. Washington Urban Institute Brief (2003) ;16. |

[43] | Auer P , Speckesser S . Labour Markets and Organisational Change. The Journal of Management and Governance (1998) ;1: (2):177–206. |

[44] | Age-friendly employment: Policies and practices, UNECE Policy Brief on Ageing No. 9 2011 [cited 2015 Sep 20]. Available from: http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/pau/_docs/age/2011/Policy-briefs/9-Policy-Brief-Age-Friendly-Employment.pdf. |

[45] | Karpinska K . Prolonged employment of older workers. Determinants of managers’ decisions regarding hiring, retention and training. Amsterdam: Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute; 2013. |

[46] | Oakman J , Howie L . How can organisations influence their older employees’ decision of when to retire. WORK: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment, and Rehabilitation (2013) ;45: :389–97. |

[47] | Tishman FM , van Looy S , Bruyère SM . Employer Strategies for Responding to an Aging Workforce. New Brunswick: NTAR Leadership Centre; (2012) . |

[48] | Working and ageing. Emerging theories and empirical perspectives. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; (2010) . |

[49] | Ilmarinen J . Towards a longer worklife: Ageing and the quality of worklife in the European Union. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health and Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Helsinki; (2006) . |

[50] | Nygård CH , Savinainen M , Kirsi T , Lumme-Sandt K , editors. Age Management during the Life Course. Proceedings of the 4th Symposium on Work Ability. Tampere: Tempere University Press; (2011) . |

[51] | Stachowska S . Zarządzanie wiekiem w organizacji. Zarządzanie Zasobami Ludzkimi (2012) ;3-4: :125–38. |

[52] | Klimkiewicz K . Zarządzanie różnorodnością jako element prospołecznej polityki przedsiębiorstwa. Współczesne Zarządzanie (2010) ;2: :91–101. |

[53] | Kumra S , Manfred S . Managing Equality and Diversity: Theory and Practice. New York: Oxford Press; (2012) . |

Figures and Tables

Fig.1

The consequences of an imbalance between work and personal life. Source: own work based on [33].

![The consequences of an imbalance between work and personal life. Source: own work based on [33].](https://content.iospress.com:443/media/wor/2016/55-3/wor-55-3-wor2435/wor-55-wor2435-g001.jpg)

Fig.2

Factors determining the maintenance of an individual’s WLB. Source: own elaboration based on [35].

![Factors determining the maintenance of an individual’s WLB. Source: own elaboration based on [35].](https://content.iospress.com:443/media/wor/2016/55-3/wor-55-3-wor2435/wor-55-wor2435-g002.jpg)

Fig.3

The respondents’ reactions to the statement “I maintain well a balance between my work and private life” according to their age (% of answers in given age groups). Source: own elaboration.

Fig.4

The respondents’ reactions to the statement “In our organization all employees have equal opportunities for flexible solutions to the work-life balance” according to their age (% of answers in given age groups). Source: own elaboration.

Table 1

Participants of the questionnaire survey, according to gender and the country of origin of the Lighthouse Organization

| N of | % of | Female | Male | |||

| respondents | respondents | N | % | N | % | |

| FI | 113 | 26% | 22 | 8% | 91 | 49% |

| LT | 265 | 60% | 174 | 69% | 91 | 49% |

| SE | 62 | 14% | 57 | 23% | 5 | 2% |

| TOTAL | 440 | 100% | 253 | 100% | 187 | 100% |

| % of column | 57% | 43% | ||||

Source: own elaboration. FI: Finland, LT: Lithuania, SE: Sweden.

Table 2

Participants of the questionnaire survey, according to age and the country of origin of the Lighthouse Organization

| Age group | Age group | Age group | Age group | ||||||

| 21–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–70 | ||||||

| N | % of line | N | % of line | N | % of line | N | % of line | ||

| FI | 25 | 22% | 25 | 22% | 31 | 27% | 32 | 29% | 100% |

| LT | 63 | 24% | 105 | 40% | 48 | 18% | 49 | 18% | 100% |

| SE | 10 | 16% | 9 | 14% | 14 | 23% | 29 | 47% | 100% |

| TOTAL | 98 | 139 | 93 | 110 | |||||

| % of column | 22% | 32% | 21% | 25% | |||||

Source: own elaboration. FI: Finland, LT: Lithuania, SE: Sweden.

Table 3

The respondents’ reactions to the statement “I maintain well a balance between my work and private life” according to their age

| Age (years) | I agree | I somewhat agree | I somewhat disagree | I disagree | I do not wish to answer | Line total | |

| 18–34 | N | 43 | 33 | 13 | 4 | 5 | 98 |

| % | 44% | 34% | 13% | 4% | 5% | 100% | |

| 35–44 | N | 52 | 65 | 10 | 12 | 0 | 139 |

| % | 37% | 47% | 7% | 9% | 0% | 100% | |

| 45–54 | N | 46 | 34 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 95 |

| % | 50% | 37% | 8% | 2% | 3% | 100% | |

| 55–70 | N | 62 | 32 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 105 |

| % | 56% | 29% | 11% | 3% | 1% | 100% | |

| TOTAL | N | 203 | 164 | 43 | 21 | 9 | 440 |

| % | 46% | 37% | 10% | 5% | 2% | 100% | |

Source: own elaboration.

Table 4

The respondents’ reactions to the statement “In our organization all employees have equal opportunities for flexible solutions to the work-life balance” according to their age

| Age (years) | No | I’m not | Yes | I do not wish | Line | |

| sure | to answer | total | ||||

| 18–34 | N | 21 | 24 | 45 | 8 | 98 |

| % | 21% | 25% | 46% | 8% | 100% | |

| 35–44 | N | 30 | 56 | 49 | 4 | 139 |

| % | 22% | 40% | 35% | 3% | 100% | |

| 45–54 | N | 34 | 32 | 26 | 1 | 95 |

| % | 37% | 34% | 28% | 1% | 100% | |

| 55–70 | N | 32 | 36 | 38 | 4 | 105 |

| % | 29% | 33% | 35% | 4% | 100% | |

| TOTAL | N | 117 | 148 | 158 | 17 | 440 |

| % | 27% | 34% | 36% | 4% | 100% | |

Source: own elaboration.