Challenges in teleworking management related to accommodations, inclusion, and the health of workers: A qualitative study through the lens of social exchanges

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Telework is increasingly prevalent and holds the potential to serve as an accommodation, facilitating inclusion and promoting healthy participation among various segments of the workforce, such as aging employees, individuals with chronic illnesses or those living alone with one or more dependents. Nevertheless, this promising avenue presents management challenges that remain underexplored in the literature.

OBJECTIVE:

This study aimed to identify the challenges in telework management related to accommodations, inclusion and the health of workers with life situations entailing specific needs.

METHODS:

We conducted a descriptive interpretative study grounded in Social Exchange Theory, by collecting data through interviews with 9 managers and conducting focus groups involving 16 workers. We used a thematic-analysis approach to analyze the data.

RESULTS:

We identified seven overarching themes encapsulating management challenges that relate to accommodation (e.g., maintaining a balance between the benefits for the worker and the impacts on the organization) inclusion (e.g., maintaining team cohesion) and health (e.g., managing teleworkers’ emotions).

CONCLUSIONS:

The findings underscore the significance of fostering robust social exchanges across hierarchical levels, and they highlight the necessity of equipping managers with the requisite tools to navigate the ethical quandaries arising from accommodation requests.

1Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly transformed ways of working for many individuals, notably by precipitating a forced shift toward digitalization and telework [1, 2]. Despite its emerging from a crisis, telework is a work-delivery modality that appears to endure over time [3]. Previously considered an exceptional accommodation for certain individuals, such as workers with physical disabilities [4], it now has wide recognition and acceptance, allowing those who benefit from it to be less marginalized. Thus, telework represents an option that can be advantageous for certain populations of workers with needs that differ from those of the majority.

Indeed, for different groups of individuals, conventional work performed at the physical place of employment can pose significant daily challenges. The literature demonstrates that certain life situations generate specific employment needs [5–7]. This is notably the case for aging workers, i.e. aged 55 and over [8], workers living with a chronic illness [5] and those living alone with one or more dependents [6]. Studies suggest that these individuals tend to experience work differently. For example, as retirement age approaches, aging workers who wish to continue working tend to disengage from traditional forms of scheduling or employment; as a result, managers may attempt to implement alternative work modalities [9]. On the other hand, workers with a chronic illness may require more regular breaks or specific furniture [5]. Individuals living alone with one or more dependents may require schedule flexibility to accommodate their reality [6]. For groups of such workers, the possibility of another work-delivery modality, such as telework, can promote their social participation and contribution to the economy, particularly in the context of labour shortages. However, despite the benefits of telework that may align with the needs of these worker populations, such as schedule flexibility [10] or control over the work environment [7], not overlooking the challenges associated with this work-delivery modality is important. These can relate to accommodations, e.g. technological difficulties [11], inclusion, e.g. difficulty maintaining relationships at a distance [12], or health, e.g. difficulty disconnecting from work [13]. “Best practices,” such as setting up a dedicated telework space and establishing a telework policy, support ensuring healthy telework use by individuals and organizations [14]. However, recent work that our team conducted suggests that the adaptation to telework by workers with specific needs differs from that of the general worker population, particularly because telework may exacerbate the feeling of isolation, and workers may tend to overinvest in their work time [15]. Thus, precautions are necessary to promote accommodations, inclusion and the health of these teleworkers, which can create daily management challenges. Current scientific literature discusses the challenges managers experience that relate to telework, such as challenges in supervising teleworkers’ tasks [16] or difficulty monitoring their performance [17]. However, literature regarding the challenges that managers experience concerning accommodations, inclusion and the health of populations with specific needs is rare. Nevertheless, the current state of knowledge indicates that these challenges do exist [15]. Indeed, organizations are open to hiring individuals with diverse profiles, including aging workers, those with a chronic illness or those living alone with one or more dependents, to maintain their activities and achieve their objectives. Moreover, the diversity of worker profiles and promoting inclusion represent assets to organizations. These practices allow expanding the available workforce, fostering worker engagement with an organization sensitive to diversity and enhancing creativity and innovation through various personnel perspectives [18]. However, once hired, organizations may not straightforwardly act to promote accommodation, inclusion and health for a heterogeneous pool of workers with disparate needs, especially in the context of telework. Authors have suggested that managers’ skills represent a lever on which to focus [19], particularly in the context of telework [16]. However, obstacles complicate their task, including the lack of tools to support them in this aspect of their functions and the fact that they must usually mobilize their personal resources to act in favour of the inclusion and health of the diverse workforce for which they are responsible [19]. Thus, it is important to focus on the challenges managers experience.

The objective of this study was to identify the challenges in telework management that relate to accommodations, inclusion and the health of workers with life situations entailing specific needs.

2State of knowledge

The groups of workers with life situations entailing specific needs regarding work, of interest to our study, represent a significant portion of the working-age population.

The number of workers aged 55 and over is increasing worldwide. In Canada, their number almost tripled from 1996 to 2018 [20], and nearly 70% of the Canadian population between 55 and 64 years old were employed in 2021 [21]. In the United States, this is the only group of workers showing an increase over the past 30 years [22], and it will experience the greatest increase by 2030 [23]. Similarly, the European Union reports a steady increase in the employment rate of 55-to-64-year-olds since 2009 [24]. These workers tend to perceive the disadvantages of telework more strongly (e.g. lack of interactions and teamwork, less feedback, fear that the manager may not perceive the quality of work done) than the benefits [12, 25], possibly due to a lower level of confidence in using technology as the main work tool [11, 25]. However, schedule flexibility that telework generally increases represents an interesting contribution for aging workers, especially as retirement approaches, for those with additional personal obligations (e.g. caring for parents, spouses or grandchildren) or who experience a decrease in energy [5, 9]. These teleworkers would have an easier time creating a work-life balance than their counterparts working at physical locations or their younger colleagues. This could be due to accumulated experience, better social and family support or the higher level of autonomy they tend to enjoy in their employment [26].

Workers with chronic illnesses also demonstrate an increased presence in the labour market. They represent nearly one in four working-age individuals across the European Union [27]. In the United States, one in five adults lives with multiple chronic illnesses [28]. The most common chronic diseases worldwide are cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, cancer and diabetes [29]. Regarding their telework experience, schedule flexibility and the choice of break times are the most important advantages the literature reports for these workers [7]. Whether to conserve energy [7] or manage pain [5], workers generally appreciate the freedom that telework grants them. Moreover, control over the physical environment (e.g. noise limitation or lighting adjustment) is a significant asset for completing work while meeting their needs [7].

Workers living alone with one or more dependents, whether a child, spouse or parent requiring assistance, represent a group that has become considerably more prominent in recent years. In 2021, 16.4% of Canadian families were single-parent families, with women heading over 75% of them [30]. In these families, the responsible adult is active in the labour market in most of cases [31]. Regarding caregivers, one in four Canadians mentioned providing care or assistance to someone in the past year [32]. Schedule flexibility is once again the major reported advantage, allowing workers to be present for their loved ones at important times of the day [6, 33]. Though drawing a line between professional and family roles may challenge some workers, the freedom telework grants and the possibility of concurrently performing household tasks reduce the daily stress level, positively impacting other areas of life [6].

Although telework may promote accommodations, inclusion and the health of workers with life situations entailing specific needs, it is not without impact on the roles of managers. However, little information is available in the literature regarding the challenges experienced in managing telework. Moreover, most articles on this topic date back to the early 2000s. Conceivably, management challenges have evolved, particularly due to technological advancements in recent years and the development of telecommunication tools. Available studies note that managers face challenges regarding the supervision of teleworkers’ tasks [16, 17, 34, 35]. Participants in Beno’s (2018) study mentioned the need to adopt other management techniques (e.g., favouring results-based management rather than observation). Moreover, they emphasized the importance of adopting a facilitating rather than a controlling role with teleworkers [17]. Cascio’s (2000) study provides interesting insights into this topic [36]. The author highlights that telework requires redefining performance. Indeed, the manager can develop specific objectives for each worker and regularly monitor progress. Each worker must understand his or her responsibilities well and have no doubt about management’s expectations and means of evaluating their work [36]. Furthermore, the author identifies the two major responsibilities of the telework manager as eliminating obstacles to worker performance and offering adequate resources. To achieve this, the manager must rely on workers’ feedback and inquire about the difficulties they encounter [36].

The literature has also raised challenges that relate to technology use [16, 35]. Remote communications can be an obstacle to team collaboration [16]; the lack of spontaneity could weaken relationships [35]. Moreover, distance can create a challenge regarding feedback, according to some managers [17]. Furthermore, finding the right opportunity to provide feedback in telework might be challenging since managers would see fewer opportunities. Some managers consider that delivering feedback via telephone sometimes generates conflicts, arising from neither side having access to nonverbal expression. Thus, video conferencing is preferable, especially since, unlike email, it promotes bidirectional communication [36]. Other managers believe in the necessity of providing negative feedback in person rather than through the screen; others mention that sometimes this feedback cannot wait until the next in-personopportunity [17].

Finally, recent studies conducted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate that managers have had to assume a new role, namely, that of providing psychological support to teleworkers experiencing difficulties in adapting to telework and managing anxiety [16]. However, these benevolent attitudes primarily stem from the managers’ own initiative; they do not receive directives from their organization or additional support or resources for this purpose [16]. Thus, these managers must rely on their own resources, examining a particular situation and judging for themselves the actions to take, according to the context.

Although the literature has highlighted some challenges managers experience, these mainly concern task management and performance, seldom considering the subject of accommodations, inclusion and the health of populations of workers with life situations entailing specific needs. We know that these populations tend to experience telework differently from the general population [15]. Addressing the management challenges that intervene in their sustainable employment maintenance is necessary to promote all interested and available individuals participating in work.

3Definition of concepts and theoretical framework

3.1Definition of the four main concepts

This study mobilizes four central concepts, namely, telework, accommodations, inclusion and health. Despite some authors proposing variants [37], telework generally means employment by an organization and predominantly providing work outside its physical premises. Thus, it requires the use of communication and information technologies (e.g. computer, internet networking, web platforms for storing and sharing information) [38]. Accommodations are adjustments to provide differential treatment to a person whom the prevailing norms in the environment would otherwise penalize [39]. In the context of employment, this obligation falls on the employer, who can minimize discrimination and assess the feasible accommodation options [39]. Inclusion refers to creating an environment, physical or virtual, where everyone is respected equitably and has access to the same opportunities. Thus, this concept represents strategies for removing obstacles that hinder participation and contribution [40], enabling everyone to express their full potential at work. Finally, the World Health Organization defines the concept of health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [41].

3.2Social Exchange Theory

The definition of these concepts and the current state of knowledge lead to an understanding that measures promoting accommodation, inclusion and health of teleworkers with life situations entailing specific needs involve an exchange of resources among individuals operating within an organization. In this regard, Social Exchange Theory [42] appears relevant to addressing this topic, as one of the most influential theories for studying interactions among different social actors and organizational behaviours [43, 44]. In the organizational context, Social Exchange Theory considers interactions and the sharing of non-monetary resources, such as time, attitudes or behaviours [45]. Although many authors have contributed to it, two basic principles support Social Exchange Theory: the individual who acts positively toward an interlocutor places the latter in a position of indebtedness, and in response to this sense of indebtedness, this interlocutor tends to offer that individual a benefit [46]. The opposite is also true: A negative action toward a person will attract one in return. Both sides have a mutual interest in maintaining a balance between investment and benefits. These reciprocal exchanges can target different resources that relate to accommodations, inclusion and health and well-being. For example, according to this theory, a positive action by the manager toward the worker, such as granting an accommodation, will generate in return a positive action from the worker toward the organization, such as increased availability for work. These social exchanges can occur at different hierarchical levels within the organization [46]. Other studies have drawn on Social Exchange Theory to document interactions aiming at mental health in the workplace [47] as well as workplace health and safety [48]. To our knowledge, no documented study has used this theory to understand telework and accommodations, inclusion and health, enhancing this research’s innovative aspect.

4Methods

4.1Design

Considering the study’s objective of identifying the challenges in telework management related to accommodations, inclusion and the health of workers with life situations entailing specific needs, we conducted this study using a descriptive interpretive design [49, 50]. Indeed, we chose this design because it allows for a contextualized and in-depth understanding of a lived phenomenon.

4.2Participants

To be included in the study, all participants had to be at least 18 years old and able to participate in an interview via the Zoom platform. They also had to meet the following inclusion criteria: holding a management position for at least two years in Quebec and working with teleworkers who identify with one or more of the situations of interest to the study, namely being 55 years old or older, having a chronic illness or living alone with one or more dependents. These three populations of workers reflect different situations in terms of accommodation, inclusion and health. Since this study draws on Social Exchange Theory to fully understand the dynamics of exchanges that influence managers’ work and challenges, we also sought the participation of workers. Inclusion criteria for these participants were having been employed for at least 5 years in Quebec, teleworked for at least 2 years and experienced one of the three situations of interest to the study. We recruited participants using a convenience non-probabilistic sampling strategy [51] through advertisements on various social media platforms (e.g. LinkedIn, Facebook). Additionally, managers’ associations agreed to disseminate recruitment posters through their member networks. Following recommendations in the literature, the study aimed for between 9 [52] and 12 [53] manager participants and an equal number of worker participants. In fact, the number of participants to be recruited is based on the criterion of saturation, the point at which no new ideas about the study subject are put forward by participants [54, 55]. In doing so, we reached the final number of participants when we observed redundancy in the ideas they expressed, indicating saturation [51]. Ultimately, 9 managers and 16 workers participated. All individuals who responded to our invitation and met the inclusion criteria were included in the study; no one dropped out.

4.3Procedure

Initially, we conducted individual semi-structured videoconference interviews with manager participants (one interview per participant), to document their managerial experience with the populations of interest in the study regarding telework, accommodation, inclusion and health. All study participants first had to complete a questionnaire to collect such sociodemographic data as age, gender and years of experience. Subsequently, we conducted interviews using a guide previously pre-tested with two individuals who had the same characteristics as the participants. The interview addressed various themes, namely, accommodation (e.g., What management challenges relate to accommodating teleworkers under your responsibility?), inclusion (e.g. What practices do you use to promote the inclusion of teleworkers under your responsibility?) and health (e.g. What pitfalls should be avoided to preserve the health of teleworkers under your responsibility?). The interviews with the managers were all conducted by the same interviewer, a research professional of more than four years of experience in qualitative research. The interviews were digitally recorded and lasted an average of 62 minutes.

Subsequently, two focus-group discussions [56] composed of 7 worker participants, using an interview guide like that used with managers. This number was sufficient to cover at least 80% of the themes that related to the studied phenomenon [57]. Each participant participated in one focus group. The two focus groups were conducted by the same interviewers, a researcher of more than 15 years of experience in qualitative research and a research professional of more than four years of experience in qualitative research. The group discussions were digitally recorded and lasted an average of 111 minutes. For two worker participants, schedule compatibility issues made it impossible to participate in the focus groups. These participants were met in individual interviews using the same interview guide.

During the data collection process, team meetings were held to discuss potential biases, defuse them, and ensure the most rigorous data collection process possible. Interviewers also used a research diary to record their experiences between debriefing meetings [51].

4.4Analysis

The recordings were first transcribed, then analyzed using a five-step thematic-analysis strategy [58]: 1) repeated reading of verbatim transcripts to allow researchers to immerse themselves in the data; 2) descriptive codes assigned to units of meaning in the data to form an initial coding; 3) units of meaning transformed into expressions representative of participants’ experiences; 4) expressions synthesized to organize the data into a general structure (i.e. codes grouped into categories and/or themes); 5) iterative cycles between raw data and analyzed data, to refine the generated structure.

We used the QDA Miner Lite software to support the analysis. Under the supervision of the lead researcher, two research team members independently analyzed each interview and met between each interview to compare and improve coding, creating an enhanced common version [59]. Between interviews, the study’s lead researcher reviewed the coding. The implication of three team members and their agreement on the coding process ensured the validity of the analysis process. In fact, the analysis process that different individuals carried out multiple times until it resulted in a product representing the data as faithfully as possible [60].

4.5Validation with participants

To ensure that the results emerging from the analyses reflects the ideas put forward by the participants, a summary document was sent to them. This document included a written summary of the results, as well as a short video presenting these results. Participants were given the opportunity to comment on the form and content of the results. This final validation step enhanced the validity of the results and improved the scientificity of the study.

To improve the rigour of this manuscript, we followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [61].

5Results

5.1Participant descriptions

Manager participants were predominantly female (89%). The average age was 40 years, and most participants held a university degree. All of these managers (100%) worked with teleworkers aged 55 and over; 78% worked with teleworkers living with a chronic illness; 33% worked with teleworkers living alone with dependents. Thus, the same manager could work with more than one category of teleworkers with life situations entailing specific needs.

Worker participants were predominantly female (81%). The average age was 46 years, and most participants held a university degree. Among these participants, 44% mentioned being at least 55 years old, and 56% identified as workers with a chronic illness. Finally, 19% reported living alone with one or more dependents (i.e., minor children, spouses or sick parents). Some participants identified with multiple categories simultaneously. Nearly 95% of worker participants mentioned spending at least half of their working time teleworking. Over 80% of worker participants worked in a public or para-public workplace. A little over one-third (37.5%) held a unionized position. Participants worked in various sectors, including intervention, education, administration, research and information technology.

5.2Telework management challenges related to accommodations, inclusion and health

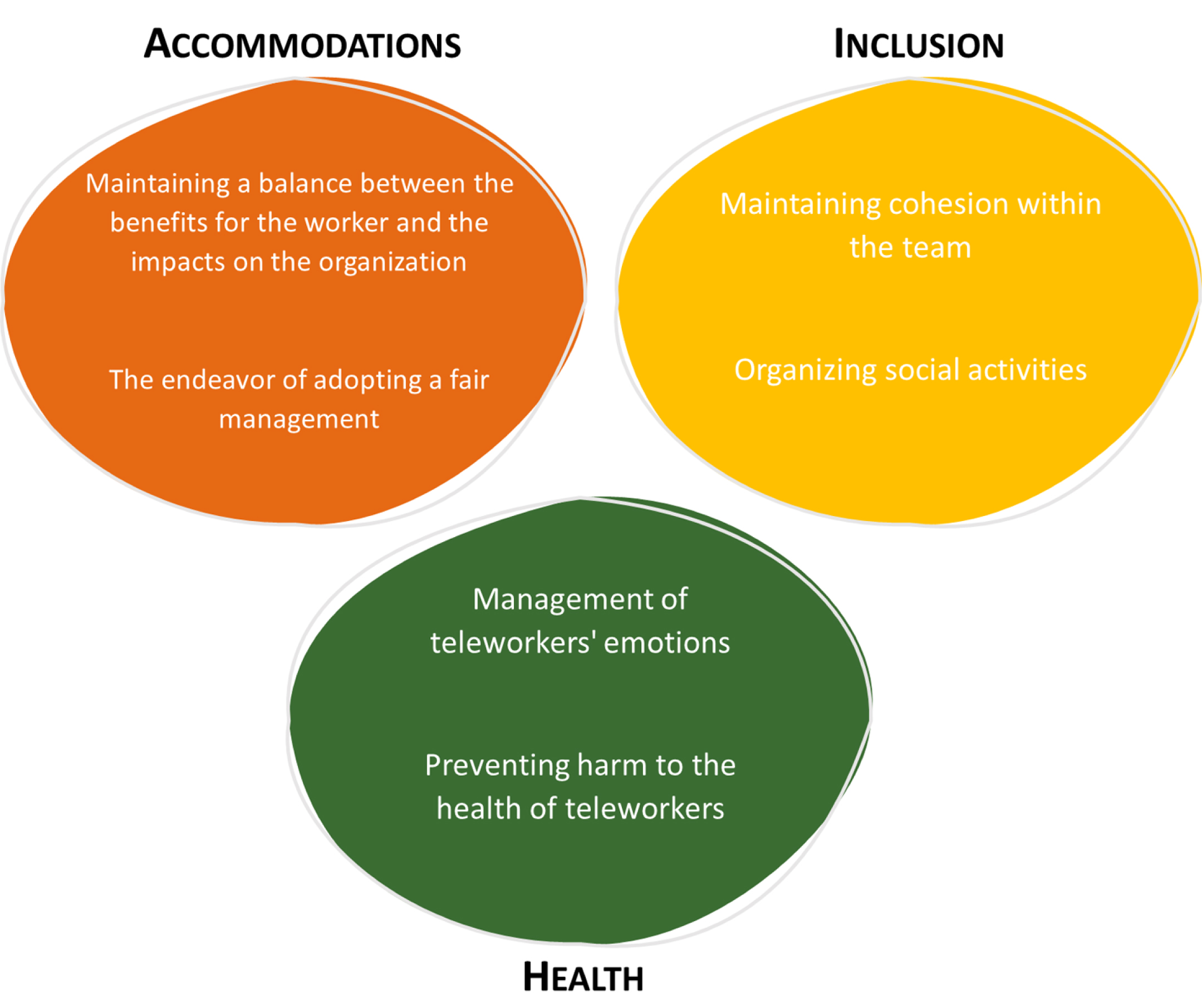

The analysis of data collected from participants identified seven themes characteristic of management challenges related to accommodations, inclusion and the health of individuals aged 55 and over, those with chronic illnesses or living alone with dependents. Figure 1 illustrates these results. The detailed coding tree is presented in Annex 1.

Fig. 1

Illustration of Study Results.

5.2.1Challenges related to accommodations

Among the challenges encountered in managing accommodations, participants repeatedly emphasized the importance of maintaining a balance between the benefits for the worker and the impacts on the organization since it involves a “cost-benefit challenge” (M05)1. Participants addressed a recurring challenge related to accommodation requests, namely, ensuring that the measure does not negatively affect the work of a colleague by adding extra pressure: “[...] if we accommodate someone, it shouldn’t overload the colleague next to them” (M07). Some mentioned that this aimed to ensure the long-term effectiveness of the team. In response to this challenge, some participants added the possibility within an organization of having workers who take on the role of ensuring completion of tasks for colleagues receiving temporary accommodations, being “willing to take over if necessary”(W13).

It appeared that the root of this concern was the endeavour to adopt fair management, always aiming to foster positive relationships and collaboration among team members. Indeed, managers mentioned the distinction they make daily between the concepts of equality and equity. Their statements demonstrate that they consider it appropriate for a worker not to have the same work accommodations as a colleague, depending on their situations. Thus, they have the concern of offering equitable working conditions to their team. However, this concern for equity entails the challenge for the manager of having to deal with “exceptions management” (W20), which implies having to justify their accommodation decisions to other employees of the organization if necessary: “[...] Equality among colleagues [is important]. If I allow something for someone else, for me, it’s normal that it’s not equal, that everyone is different. [I need to clarify] the rationale behind my decision so that I can give meaning to the team” (M05).

Furthermore, managers mentioned the necessity of demonstrating increased adaptability to promote accommodations: “[...] We need to have more understanding... When we hired them, these people told us about their health condition and their age. We knew we would need to be more understanding [and offer] a few more breaks, a few fewer hours, etc.” (M06). On this subject, other participants emphasized the need to base accommodation management on carefully listening to workers, especially those with different mobility or chronic illnesses: “If the manager does it with empathy, meaning she genuinely listens to the person’s needs, I think the job market will be much more open to people who currently cannot work due to different mobility or chronic illnesses” (W21). The manager’s overall appreciation of the worker seems to influence this adaptability. One participant mentioned being willing to accept a particular employee’s situation and implement special accommodations, due to the high level of availability that employee demonstrated:

“[...] With her [the worker], we had to adapt. Sometimes, there are delays in response because she’s not always sitting, not in front of her computer 24/7, she goes to the bathroom, etc. [...] We were ready to grant that because she’s super available. We can count on her to replace people. We’re also open on Saturdays, well, she’s always available. Because she has this [availability], we have a higher threshold of tolerance” (M09).

Finally, participants mentioned the challenge of clarifying the responsibility for accommodations when managing them. Although many organizations have a telework policy that sets guidelines for its implementation, managers still face challenges that accommodation requests may pose, especially concerning the accountability for telework-related expenses:

“In the past, there have been examples where the person had to download several large files [at home]. Then, she came to us saying, ‘My [internet service] bill is fifty dollars higher than usual.’ We need to have a discussion with the employee to find out what we can agree on. Our policy does not cover paying personal internet expenses. So, we asked her to do this kind of file transfer by sending them to someone internally to do it or to come and do it physically here. So, that solves the problem. We still had to have some discussions about it” (M02).

Additionally, several participants mentioned the challenge of drawing the line between telework, sick leave and vacation. Indeed, teleworking outside one’s usual workplace can appear to be ineffective— for example, when it occurs during a trip or vacation, notably due to the possibility of a poor internet connection:

“[...] So yes, she went [to work outside] and she didn’t tell us. She went to a cabin deep in [the woods] and we realized because she had problems using the phone. We’re [a company that operates in the] telecommunications industry! The internet wasn’t strong enough there. So, basically, we told her: ‘Have a good vacation, and you’ll come back later.’ She had already left, and we didn’t know” (M06).

One participant also mentioned a presenteeism challenge in the context of telework. She argued that the accessibility of telework can lead to exhaustion for workers who continue to work despite signs of fatigue, which can be challenging for managers to discern at a distance. To avoid exhaustion, it appears important to her to clearly distinguish between working days and days off:

“[...] When you have a strong sense of belonging [to the employer], often you’ll end up more exhausted. [Even if you’re tired], you’ll keep wanting to work because you’re at home... you’ll tell yourself that you can rest a little more. Before, people might have been more inclined to take sick leave, etc., when they were exhausted and not feeling well. But with telework, it seems like we almost feel guilty about taking a day off because we’re at home, so as a result, we end up more exhausted on a daily basis” (W17).

Last, the shared responsibility for accommodations also involves managing abuses regarding accommodations. Managers highlighted that being confronted with abuse from some teleworkers poses management challenges, particularly regarding the trust placed in workers:

“Just last week, I was alerted that there might be someone abusing [the system]. It’s something we’ll have to monitor more closely. I wouldn’t want to come to the point of imposing fixed break times because I find it unnatural, and it’s not helpful for everyone who needs a little more and doesn’t abuse it” (M06).

5.2.2Challenges related to inclusion

The analysis of the results demonstrated challenges encountered regarding teleworkers’ inclusion. Several participants mentioned challenges related to maintaining cohesion within the team. Indeed, doing so while one or more workers do telework requires managers to integrate new creative methods. They mentioned encountering difficulties in incorporating informal exchanges among colleagues into telework contexts. Distance seems to leave little room for exchanges that do not directly relate to work tasks: “We are mostly in a formal setting; there are fewer connections that foster mutual appreciation of people, who they are as individuals” (M05). Similarly, participants highlighted the difficulty of maintaining a sense of belonging within the team as a significant challenge for managers to overcome. Once again, participants mentioned that this new reality requires initiative: “I think we need to find a kind of balance between telework and the sense of community found in the workplace. It’s a challenge for which we haven’t found the magic recipe yet” (M02). Indeed, the statements of worker participants reinforced this difficulty, expressing their feeling a different connection with their colleagues, due to their absence from events that allow for informal discussions:

“On Wednesday, there was a little cocktail lunch because we just found a new location. Well, I wasn’t at the cocktail lunch. I wasn’t there. [...] Sooner or later, it will come back to me because I won’t have done any relational or interpersonal work. Bonds will have been formed among my colleagues, but I won’t be part of them” (W19).

Moreover, managers reported feeling the need to prioritize productivity at the expense of social exchanges with the team. For some, their heavy workload occupies most of their time, limiting exchanges and follow-up with the team: “We want to satisfy the client so much, we want to tick off everything on the checklist, so it puts the team in second place, and we mustn’t forget that it’s thanks to the team that we can tick off that checklist” (M03). Many perceive this situation as a challenge, especially due to the limited time in their schedule. The statements of worker participants demonstrate that they perceive their managers experiencing this challenge. Similarly, they assert the necessity of prioritizing exchanges and listening to workers to achieve the organization’s growth objectives: “I know that now there are many managers who are overloaded, but we still need to find time for the employees because it’s teamwork that will move the company forward” (W24). One participant argued that to address this situation, the organization providing explicit support to managers would be appropriate, so they feel more comfortable allocating time to maintaining good relationships among individuals:

“Our schedule is overloaded all the time, so we end up not prioritizing that [aspect of team cohesion]. [There should be] an organizational willingness that is declared to manage [human] resources in telework so that it doesn’t cause future problems. [There should be] a clear position from the organization; I think it could help if we were told that it’s okay to reserve time slots on the agenda specifically for that, to ensure that this follow-up [related to interpersonal relationships] is done” (M08).

In line with the challenge of maintaining cohesion within the team, managers mentioned the challenge of organizing social activities. Participants mentioned the difficulty of mobilizing members of their teams for social gatherings in person: “Every time we try to plan something in person, it’s a total flop. [...] Some [employees] don’t want to come because it’s a social activity and it can be difficult for them [given their circumstances]” (M06).

Another challenge that adds to the complexity of organizing in-person social activities is the need to pay attention to the accessibility of the venues. Indeed, the physical condition of some workers with special needs may limit access to different establishments: “And sometimes, when there’s a particular physical condition, there are challenges related to that” (M02).

5.2.3Challenges related to health

Participants mentioned various challenges related to teleworkers’ health. Many highlighted a sense of helplessness regarding the management of teleworkers’ emotions. The physical distance that telework imposes complicates the provision of support that a manager can offer or, at the very least, the impression of offering support. Establishing a connection with the worker to offer support during difficult times seems more difficult and can lead to a sense of manager helplessness or questioning regarding the right actionsto take:

“I think managing emotions on screen [is a challenge]. Not being able to be present to touch or provide support, moral support. It’s different being at a distance and not being able to do anything, feeling powerless about it. Because I know that once she [the worker] burst into tears, and I couldn’t [support her]. I was uncomfortable because I wasn’t physically able to do anything. Verbally, we don’t want to be indelicate, and we don’t necessarily know what to say. I think that’s the kind of situation that was hardest for me” (M03).

Next, participants emphasized the need to adapt to new obligations regarding preventing harm to teleworkers’ health. The gradual introduction of new rules and laws regulating telework requires adjustments from organizations and managers. Indeed, they have the responsibility to be attentive to the risks that work poses for the employee, even remotely. This generates various reflections among participants on ways to ensure healthy work involvement, particularly regarding the context of private life that accompanies telework:

“I think isolation and psychological disorders are more likely to occur. I think we need to show greater understanding. And there’s also the aspect of family life that can be affected, such as domestic violence” (M08).

6Discussion

This study identified seven themes regarding challenges that managers experience in managing telework, related to accommodations, inclusion and the health of workers with life situations entailing specific needs. It contributes to the advancement of knowledge based on two main ideas: 1) the importance of social exchanges at various hierarchical levels and 2) the need to provide tools for managing the ethical dilemmas that accommodation requests generate.

6.1The importance of social exchanges at various hierarchical levels

To support managers in their role regarding accommodations, inclusion and teleworkers’ health, emphasizing social exchanges not only with employees but also with employers appears to be a favoured solution. Concerning exchanges with employees, our results suggest that a positive relationship with an employee encourages the manager to grant more accommodations. For example, an employee who offers the organization considerable flexibility will more easily be granted accommodations, such as the leisure to adjust one’s work schedule according to one’s needs. Conversely, our results also suggest that if employees abuse the accommodations offered to them (e.g., not respecting the established framework), the manager will be less inclined to offer accommodations. Social Exchange Theory supports the idea that behaviour that one party initiates leads to a similar response from the other party [62]. Our results align with this; positive (or negative) behaviours from the worker toward the organization encourage a positive (or negative) response from the manager, which can manifest in granting an accommodation (or not). Relying on positive and quality social relationships regarding accommodations would thus benefit both the manager and the teleworker. Indeed, if the manager acts benevolently toward the teleworker by granting accommodations, the latter will feel indebted and act positively toward the manager. Study results suggest that this process may encourage the worker to adopt behaviours favourable to the health of the manager, such as offering support or recognition [63]. Thus, our results align with studies recognizing the benefits of the quality of manager-employee relationships [e.g., 64–66].

Other results lead us to understand that managers would need to receive resource exchanges from the organization to better support the implementation of actions with workers. Indeed, participants in our study mentioned that managers have difficulty finding time to address topics with teleworking employees, other than those that are task-related (e.g., little time to inquire about their health) or feeling powerless when it comes to emotionally supporting a teleworker. Therefore, the organization caring about having quality exchanges with managers and providing them with the resources to better equip them in their work regarding accommodation, inclusion and health would be judicious. The social exchanges that managers have with employees could subsequently reflect such exchanges. Indeed, evidence suggests a hierarchical cascade of social exchanges, a chain of behaviours that reverberate between hierarchical levels of an organization, from the senior manager to the manager and then to the employees [46]. Other works also support the behaviours of senior management cascading down to several hierarchical levels of the organization and influencing attitudes and behaviours, such as those of managers toward employees [67]. Those attitudes and behaviours of managers toward their employees react to organizational variables, such as the characteristics or leadership style of the top manager [67]. Thus, reflecting on the quality of social exchanges at various hierarchical levels of an organization to support accommodation, inclusion and the health of workers with life situations entailing specific needs is important.

6.2Accommodations raise ethical dilemmas

The interpretation of our results suggests that managing accommodations entails particularly difficult challenges that can even represent ethical dilemmas for managers. This may be due to the ambiguity that accommodation requests create and the perpetual questioning of the manager about the path to follow to favour the interests of different actors (e.g., workers, colleagues, organization) while respecting their own values. Our results demonstrate a real willingness on the part of managers to distribute the burden of accommodations so that the organization’s norms do not penalize a worker due to his or her particular needs. However, the value of equity seemed to be central for them, which raises several ethical reflections. Drawing on Social Exchange Theory enables assuming that this strategy aims to foster a positive balance in exchanges with other worker members of the team. Indeed, by adopting the value of equity to guide managing accommodations, workers may perceive ethical leadership that promotes their engagement with the manager and the organization [68].

We can distinguish two main branches in the study of ethics, namely, normative ethics and descriptive ethics. Normative ethics represents critical reflection to determine the behaviour to favour on the part of both institutions and individuals [69]. Descriptive ethics represents the description of judgments and the practices and policies that social actors and organizations generate [70]. This type of ethics can shed light on our research results, which demonstrate that for managers, one of the central questions in managing accommodations relates to identifying the individuals whom their decisions will affect and the repercussions of these decisions for those individuals. Their goal seems to be to promote benefits and reduce negative impacts on the greatest number of people. Furthermore, our results suggest that after making a decision, managers should remain vigilant about the repercussions for team members and, if necessary, correct course. Our results suggest that one element difficult for managers to experience is the uncertainty associated with the decision, a possible source of anxiety. This situation is consistent with writings on ethical dilemmas that suggest no single right decision is possible; rather, multiple possibilities could resolve a situation [70]. Thus, it would be pertinent to provide managers with support to help them resolve the ethical dilemmas they face, especially regarding decision-making steps or the criteria on which to rely. The literature suggests several models of ethical decision-making for managers in a work context, such as that of Toren and Wagner [71]. This model suggests that after defining the challenges of the ethical dilemma, clarifying the personal and professional values at play as well as the legal and ethical obligations related to them is important. Then, it is necessary to identify all possible avenues, beyond those generally used, and choose the one that best fits the stages of reflection. Finally, the authors of the model advocate opening the discussion on the decisions that have been made, to make them guidelines for the organization in the future by generalizing the decisions to similar cases, when applicable [71].

6.3Research implications

We hope that the results of this study will open up the discussion on the important subject of accommodation, inclusion and health, and generate possible solutions to encourage the healthy participation at work for workers and managers. It is hoped that the identified themes will foster the research to develop new tools to face the challenges of managing accommodation and its impact on inclusion and health for workers with life situations entailing specific needs. In addition to these practical implications, this project also has research implications, in terms of methodology. The inclusion of participants from two populations with complementary experiential expertise in relation to the study subject is relevant when conducting research in the field of work. The triangulation of the different perspectives gathered during this study makes it possible to refine the subject studied and obtain a more representative and realistic vision of it [72, 73].

6.4Strengths and limitations

Although this study has several methodological strengths, such as a rigorous analysis strategy, we must consider some limitations. On one hand, both among managers and workers, the majority of the study participants were women. Gender may influence the different challenges participants encountered, the experiences they lived and the reflections they reported. In particular, authors identified management styles and attitudes associated with gender, which can influence transmission dynamics [74]. Furthermore, the level of education of the sample was high (mostly university level) for all participants. Although this situation reduces the variability sought in the profile of participants, notably, a telework or management position often requires a high level of education, due to the tasks it requires. This study included three types of populations with special needs. Thus, transferability to other populations requires caution.

7Conclusion

In this study, we identified seven themes regarding challenges in managing accommodations, inclusion and the health of teleworkers with special needs. The main contributions of these results lie in the importance of social exchanges at different hierarchical levels and the need to provide support tools for managing the ethical dilemmas that accommodation requests generate. Given the aging demographic profile and the heightened emphasis on principles of equity, diversity and inclusion in organizational contexts, intensifying efforts aimed at preparing managers to adeptly manage accommodation, foster inclusion and safeguard the health of individuals grappling with unique circumstances necessitating tailored support is imperative.

Ethics approval

This study obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Centre intégré universitaire en santé et services sociaux de la Capitale-Nationale (project 2023-2805) and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (project CER-23-298-10.01).

Informed consent

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were per the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Valérie Marcotte, research assistant, for her help during data collection and analysis. The authors also thank Lauriane Drolet, postdoctoral fellow, for her reading of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out with the help of research grants from the Quebec Network for Research on Aging (a Thematic Network funded by Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (grant 892-2022-2010).

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, AL, upon reasonable request.

Supplementary material

{ label (or @symbol) needed for fn } The Annex is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/WOR-240208.

References

[1] | Jauvin N , Stock S , Laforest J , Roberge MC , Melançon A . Le télétravail en contexte de pandémie: Mesures de prévention de la COVID-19 en milieu de travail – recommandations intérimaires. Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2020. |

[2] | Zossou C . Partage des tâches domestiques: Faire équipe pendant la pandémie. Statistique Canada; 2021. |

[3] | Institut de la statistique du Québec. Marché du travail et rémunération. 2024. |

[4] | Moon NW , Linden MA , Bricout JC , Baker PM . Telework rationale and implementation for people with disabilities: Considerations for employer policymaking. Work. (2014) ;48: (1):105–15. |

[5] | Skamagki G , Carpenter C , King A , Wåhlin C . Management of Chronic Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Workplace from the Perspective of Older Employees: A Mixed Methods Research Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. (2022) ;19: (15):9348. |

[6] | Andrada-Poa MRJ , Jabal RF , Cleofas JV . Single mothering during the COVID-19 pandemic: A remote photovoice project among Filipino single mothers working from home. Community, Work & Family. (2022) ;25: (2):260–78. |

[7] | Das M , Tang J , Ringland KE , Piper AM . Towards accessible remote work: Understanding Work-from-Home practices of neurodivergent professionals. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. (2021) ;5: (CSCW1):1–30. |

[8] | Statistiques Canada. Census in Brief: Working seniors in Canada. Ottawa. (2017) . p. 14. |

[9] | Johnson RW . Phased Retirement and Workplace Flexibility for Older Adults: Opportunities and Challenges. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. (2011) ;638: :68–85. |

[10] | Ipsen C , van Veldhoven M , Kirchner K , Hansen JP Six key advantages and disadvantages of working from home in Europe during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. (2021) ;18: (4):1826–. |

[11] | Toscano F , Bigliardi E , Polevaya MV , Kamneva EV , Zappalà S Working Remotely During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Work-Related Psychosocial Factors, Work Satisfaction, and Job Performance Among Russian Employees. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art. (2022) ;15: (1):3–19. |

[12] | Raišienėq AG , Rapuano V , Varkulevičiūtėq K , Stachová K . Working from Home— Who Is Happy? A Survey of Lithuania’s Employees during the COVID-19 Quarantine Period. Sustainability. (2020) ;12: (13):5332. |

[13] | Magnavita N , Tripepi G , Chiorri C . Telecommuting, off-time work, and intrusive leadership in workers’ well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. (2021) ;18: (7):3330. |

[14] | Labrecque C , Lecours A , Gilbert M-H , Boucher F . Workers’ perspectives on the effects of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic on their well-being: A qualitative study in Canada. Work. (2023) ;74: (3):785. |

[15] | Lecours A , Gilbert M-H , Boucher N , Vincent C . The Effects of Teleworking in a Pandemic Context on the Well-Being of People with Disabilities: A Canadian Qualitative Study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2022. |

[16] | Dandalt E . Managers and telework in public sector organizations during a crisis. Journal of Management & Organization. (2021) ;27: (6):1169–82. |

[17] | Beno M , editor Managing telework from an Austrian manager’s perspective. Trends and Advances in Information Systems and Technologies: Volume1 6: ; (2018) : Springer. |

[18] | O’Donovan D . Diversity and Inclusion in the Workplace. Springer International Publishing; (2018) . p. 73–108. |

[19] | Maclure J , Therriault P-Y . Contribution de gestionnaires intermédiaires au maintien en emploi de travailleurs vivant avec une maladie chronique. Enjeux et société. (2022) ;9: (1):154–82. |

[20] | Ouellet-Léveillé B , Milan A . Résultats du Recensement de 2016: Les professions comptant des travailleurs âagés: Statistique Canada=Statistics Canada; 2019. |

[21] | Statistique Canada. Enquête sur la population active. 2021. |

[22] | Toossi M , Torpey E . Older workers: Labor force trends and career options. In: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, editor. :Career Outlook; 2017. |

[23] | Bureau of Labor Statistics. Number of people 75 and older in the labor force is expected to grow 96.5 percent by 2030. In: Labor USDo, editor.: The Economics Daily; 2021. |

[24] | Eurostat. Taux d’emploi des personnes agées, tranche d’âge 55–64 ans. In: Européenne C, editor. 2022. |

[25] | Tahlyan D , Said M , Mahmassani H , Stathopoulos A , Walker J , Shaheen S . For whom did telework not work during the Pandemic? understanding the factors impacting telework satisfaction in the US using a multiple indicator multiple cause (MIMIC) model. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. (2022) ;155: :387–402. |

[26] | Wu H , Song Q , Proctor RW , Chen Y . Family relationships under work from home: Exploring the role of adaptive processes. Frontiers in Public Health. (2022) ;10: :307. |

[27] | European Chronic Diseases Alliance. Joint Statement on “Improving the Employment of People with Chronic Diseases in Europe”. 2017. |

[28] | Ward B , Schiller J . Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among us adults: Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey. Preventing Chronic Disease. (2013) ;10: :E65. |

[29] | OMS. Noncommunicable diseases 2022 Available from: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. |

[30] | Statistique Canada. Profil du recensement, Recensement de la population de 2021. 2023. |

[31] | Statistique Canada. Caractéristiques de la population active selon la composition familiale et l’âge, données annuelles, inactif. 2023. |

[32] | Hango D . Soutien reçu par les aidants au Canada. In: Sociales Cdredied, editor.: Statistique Canada; 2020. |

[33] | Marsh K , Musson G . Men at Work and at Home: Managing Emotion in Telework. Gender, Work & Organization. (2008) ;15: (1):31–48. |

[34] | Greer TW , Payne SC . Overcoming telework challenges: Outcomes of successful telework strategies. The Psychologist-Manager Journal. (2014) ;17: (2):87. |

[35] | Scholefield G , Peel S . Managers’ attitudes to teleworking. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations. (2009) ;34: (3):1–13. |

[36] | Cascio WF . Managing a virtual workplace. Academy of Management Perspectives. (2000) ;14: (3):81–90. |

[37] | Haddon L , Brynin M . The character of telework and the characteristics of teleworkers. New Technology, Work and Employment. (2005) ;20: (1):34–46. |

[38] | Garrett RK , Danziger JN . Which telework? Defining and testing a taxonomy of technology-mediated work at a distance. Social Science Computer Review. (2007) ;25: (1):27–47. |

[39] | Bosset P . Les fondements juridiques et l’évolution de l’obligation d’accommodement raisonnable: Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse Québec...; 2007. |

[40] | CRSNG. Guide du candidat: Tenir compte de l’équité, de la diversité et de l’inclusion dans votre demande. (2017) . p. 12. |

[41] | OMS. Constitution de l’OMS. Genève: Organisation mondiale de la Santé; (1985) . Report No.: 9242602515. |

[42] | Blau PM . Social exchange theory. Retrieved September. (1964) ;3: (2007):62. |

[43] | Cropanzano R , Mitchell MS . Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J Manage. (2005) ;31: (6):874–900. |

[44] | Chernyak-Hai L , Rabenu E . The new era workplace relationships: Is social exchange theory still relevant? Industrial and Organizational Psychology (2018) ;11: (3):456–81. |

[45] | Cole MS , Schaninger WS Jr , Harris SG . The workplace social exchange network: A multilevel, conceptual examination. Group & Organization Management. (2002) ;27: (1):142–67. |

[46] | Cropanzano R , Anthony EL , Daniels SR , Hall AV . Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Academy of Management Annals. (2017) ;11: (1):479–516. |

[47] | Lecours A , St-Hilaire F , Daneau P . Fostering mental health at work: The butterfly effect of management behaviors. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. (2022) ;33: (13):2744–66. |

[48] | Hofmann DA , Morgeson FP . Safety-related behavior as a social exchange: The role of perceived organizational support and leader– member exchange. Journal of applied psychology. (1999) ;84: (2):286. |

[49] | Gallagher F , Marceau M . La recherche descriptive interprétative. In: Corbière M, Larivière N, editors. Méthodes qualitatives, quantitatives et mixtes: Dans la recherche en sciences humaines, sociales et de la santé. Dans la recherche en sciences humaines, sociales et de la santé. 2 ed: Presses de l’Université du Québec; (2020) . p. 5–32. |

[50] | Thorne S . Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice: Routledge; 2016. |

[51] | Fortin M-F , Gagnon J . Fondements et étapes du processus de recherche: Méthodes quantitatives et qualitatives. 4e ed. Montréal: Chenelière éducation; (2022) . 496p. |

[52] | Hennink MM , Kaiser BN , Marconi VC . Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qualitative health research (2017) ;27: (4):591–608. |

[53] | Guest G , Bunce A , Johnson L . How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods. (2006) ;18: (1):59–82. |

[54] | Bernard HR , Wutich A , Ryan GW . Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches: SAGE publications; 2015. |

[55] | Given LM . 100 questions (and answers) about qualitative research: SAGE publications; 2015. |

[56] | Desrosiers J , Larivière N . Le groupe de discussion focalisé. In: Corbière M, Larivières N, editors. Méthodes qualitatives, quantitatives et mixtes. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec; (2014) . p. 257–81. |

[57] | Guest G , Namey E , McKenna K . How Many Focus Groups Are Enough? Building an Evidence Base for Nonprobability Sample Sizes. Field Methods. (2017) ;29: (1):3–22. |

[58] | Paillé P , Mucchielli A . L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales. 5ed. Paris: Armand Colin; (2021) . 430p. |

[59] | Blais M , Martineau S . L’analyse inductive générale: Description d’une démarche visant à donner un sens à des données brutes. Recherches Qualitatives. (2006) ;26: (2):1–18. |

[60] | Drapeau M . Les critères de scientificité en recherche qualitative. Pratiques psychologiques. (2004) ;10: (1):79–86. |

[61] | O’Brien BC , Harris IB , Beckman TJ , Reed DA , Cook DA . Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic medicine. (2014) ;89: (9):1245–51. |

[62] | Cropanzano R , Mitchell MS . Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of management. (2005) ;31: (6):874–900. |

[63] | St-Hilaire F , Gilbert M-H , Brun J-P . What if subordinates took care of managers’ mental health at work? The International Journal of Human Resource Management. (2019) ;30: (2):337–59. |

[64] | Settoon RP , Bennett N , Liden RC . Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader-member exchange, and employee reciprocity. Journal of Applied Psychology. (1996) ;81: (3):219. |

[65] | Tan JX , Zawawi D , Aziz YA . Benevolent Leadership and Its Organisational Outcomes: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective. International Journal of Economics & Management. (2016) ;10: (2). |

[66] | Wang C-J . Do Social Exchange Relationships Influence Total-Quality-Management Involvement? Evidence from Frontline Employees of International Hotels. Behavioral Sciences. (2023) ;13: (12):1013–. |

[67] | Liden R , Fu P , Liu J , Song L . The influence of CEO values and leadership on middle manager exchange behaviors A longitudinal multilevel examination. Nankai Business Review International. (2016) ;7: (1):2–20. |

[68] | Hansen SD , Alge BJ , Brown ME , Jackson CL , Dunford BB . Ethical leadership: Assessing the value of a multifoci social exchange perspective. Journal of business ethics. (2013) ;115: :435–49. |

[69] | Drolet M-J . De l’éthique à l’ergothérapie: La philosophie au service de la pratique ergothérapique: PUQ; 2014. |

[70] | McCullough LB , Coverdale JH , Chervenak FA . Argument-based medical ethics: A formal tool for critically appraising the normative medical ethics literature. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. (2004) ;191: (4):1097–102. |

[71] | Toren O , Wagner N . Applying an ethical decision-making tool to a nurse management dilemma. Nursing Ethics. (2010) ;17: (3):393–402. |

[72] | Massé L . L’évaluation des besoins. In: Alain M, Dessureault D, editors. Élaborer et évaluer les programmes d’intervention psychosociale. 1ed: Presses de l’Université du Québec; (2009) . p. 73–100. |

[73] | Savoie-Zajc L . Les pratiques des chercheurs liées au soutien de la rigueur dans leur recherche: Une analyse d’articles de Recherches qualitatives parus entre 2010 et 2017. Recherches qualitatives. (2019) ;38: (1):32–52. |

[74] | Giguère É , Pelletier M , Bilodeau K , Avoine J , Sirois Gagné M , St-Arnaud L . De la proximité à la tyrannie: Dynamiques relationnelles et pratiques de gestion des femmes cadres. Ad machina. (2023) ;(7):61–79. |

Notes

1 Verbatim extracts from the participants’ interviews exemplify the challenges. The extracts are a free translation from the original French transcripts. 1 Letters in parentheses refer to the participants’ type: M = manager, W = worker. Numbers (1 to 25) refer to the participant’s number.