Decent work and the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic: A two-wave study1

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The world is going through a challenging historical moment, with the COVID-19 pandemic affecting billions of lives and communities worldwide.

OBJECTIVE:

Building on the widespread negative impact of the pandemic on the socio-economic context, and consequently on the labour market, the aim of this study was to analyse the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on workers’ perception of decent work.

METHODS:

The Decent Work Questionnaire was administered to 243 workers from seven Portuguese organisations at two-time points (before and during the pandemic).

RESULTS:

Results revealed a positive and significant effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on six of seven dimensions of decent work, particularly those related to Meaningful Remuneration for the Exercise of Citizenship and Health and Safety.

CONCLUSION:

The positive effects of social comparison processes are stronger than the negative effects of the adverse socio-economic context. Faced with the COVID-19 pandemic, workers may have compared their work situation with the condition of other workers, activating an increase in their subjective perception of the value of their current reality.

1Introduction

The new pandemic reality was widespread worldwide and caused drastic and dramatic changes in the economic, social and work areas [1]. Several factors such as social distancing, prophylactic self-isolation, travel restrictions, and quarantine have led to a reduction in the workforce across most economic sectors and, consequently, increased unemployment [2, 3, 4]. The reports by the ILO and other international organisations highlighted the pandemic’s impact on the labour domain. This impact can result in extreme operating environments due to organisations’ difficulty operating in high levels of uncertainty [5]. From an organisational perspective, keeping adequate working conditions to promote and sustain workers’ motivation and well-being can be highly demanding. Such an endeavour requires workers’ confidence in organisations through protective measures [6]. In this broad context, the concept of decent work is of utmost prominence.

The ILO first defined the concept of decent work as the sum of people’s “aspirations for opportunity and income; rights, voice and recognition; family stability and personal development; and fairness and gender equality” [7 p3]. This concept expresses the Human Rights Declaration in the labour sphere, and its integrative characteristics highlight the strength of this concept for intervention [8]. According to the conceptualization of the ILO, 11 substantive elements are integrated into that concept [9]. These 11 components are structured in seven psychological dimensions in workers’ minds [10]. The proposition of the concept of decent work is aligned with other United Nations (UN) initiatives, such as the UN Global Compact [20] and the Millennium Goals [11], being the eighth objective of the UN 17 Sustainable Development Goals [12]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) became the Agenda 2030, which addresses various dimensions of sustainable development, and promotes peace and justice to be achieved by developed and developing countries [12, 13]. Therefore, decent work is an aspirational concept that must be used as an ideal to pursue.

A compelling body of evidence suggested that decent work contributes significantly to improving employees’ lives and experiences in their workplaces and plays an essential role in human behaviour related to well-being and performance [14]. Strengthening decent work will improve employees’ psychological capital and life and job satisfaction [15, 16]. Recent studies evidenced that the more decent work conditions are achieved, the more employees are intrinsically motivated by their jobs [14, 16]. Although the current theoretical and empirical knowledge about decent work provided a comprehensible roadmap of employees’ experiences regarding their work under typical circumstances, these changes have not been examined under pandemic context.

The pandemic context objectively affected the last substantive element of decent work (economic and social context). This element influences the way workers perceive their level of decent work since it establishes comparison terms adjusted to that specific context. Additionally, the socio-economic context can objectively affect the working conditions [17], mainly when events affect the entire population. Consequently, the social-economic context affects how decent work can be put into practice [18, 19] and probably how workers assess their work’s content, conditions and context. The socio-economic impact needs to be assessed to cope with the pandemic [20]. However, the macro contextual aspects of the pandemic do not apply to all workers. Many Portuguese organisations remained open during the pandemic and did not implement lay-offs [21]. As such, the perception of decent work by Portuguese workers who maintained the same job and employment conditions does not correspond to the perception of those who lost their jobs or saw working conditions undermined by the pandemic. Some organisational approaches may be important to understand the impact of the pandemic in those organisations.

As work activity and jobs in many organisations remained in previously existing conditions during the crisis, it is likely that social comparison processes could be triggered by workers. According to the social comparison theory [22], people use social reality to adapt their behaviours or opinions and assess themselves through comparison with others. Consequently, by comparing their employment conditions with those who lost their jobs (temporarily or permanently), workers may evaluate their work situation more positively. The equity theory [23] proposes that workers observe what they own in the organisation (e.g., benefits) with their skills, compare themselves with workers who perform the same or similar function, and evaluate through this comparison if they consider it fair. As such, the balance between contribution and remuneration could became more favourable to those who maintained their employment conditions. The social identity theory [24] states that identification translates a perception of uniqueness within the organisation to a point where the individual experiences its success or failure as his own success or failure. Considering that within a reality that caused drastic changes in the economic and work context, many Portuguese organisations ensure the same objective work situation, employees may have recognised and valued the organisational efforts, increasing their emotional belonging. Furthermore, workers are also driven by reciprocity as found by Davlembayeva et al. [25] concerning circular economy. With this background, we hypothesised that in Portuguese organisations that maintained regular activity during the pandemic, the pandemic context would have a positive effect on the workers’ assessment of the level of the decent work dimensions.

Despite the increasing research on decent work, the employees’ perceptions regarding their work have not been examined under pandemic conditions. This study intends to contribute to the existing literature in two ways. First, it makes a unique and valuable contribution towards understanding the role of the objective changes in the context of the employees’ subjective perception. Second, considering that the COVID-19 pandemic is the greatest challenge of this era [26], this study addresses a historical moment and a more refined understanding of these changes will be a timely and unique challenge to the existing knowledge. We hope the results will help organisational leaders to understand contextual factors’ role in the workers’ perception of decent work and contribute to new research in the field. Therefore, in the present study we examined the effect of the pandemic context on workers’ perception of decent work in a sample of employees of seven Portuguese organisations, considering that the objective work conditions and content remained equal to those employees. In addition, we explore if there were differences across time considering some background variables (age, gender, education, and seniority in the organization and job function).

2Method

2.1Participants and procedure

This study is part of a broader research project to promote the alignment of seven small or medium-sized Portuguese organisations with values through organisational values-based interventions. After conducting seminars with Portuguese organisational leaders, in the north and centre of Portugal, seven Portuguese organisations met the eligibility criteria defined by the research team for participating in the project. The seven Portuguese organisations belonged to the construction industry (n = 16 participants), manufacture and selling of handmade chocolates (n = 7 participants), the industry of manufacturing plastic packaging (n = 80 participants), wine production (n = 29 participants), production, trade, import and export of horticultural plants (n = 49 participants), production and wholesale of dietary and medicinal products (n = 52 participants), and the manufacture of metallic products (n = 10 participants). Therefore, all of them belong to the primary or secondary economic sectors.

The pandemic context unexpectedly implied an additional moment of data collection. We report here the differences between the workers’ perception of decent work at the first assessment (Time 1, September–October 2019) and the second assessment (Time 2), which took place one year later (September–October 2020). Both data collection moments occurred before the change intervention started since the pandemic led to the postponement. A quantitative descriptive two-wave study was carried out. This two-wave design allowed comparing workers’ perceptions in a pre-pandemic context with the current pandemic context. Only the 243 participants who responded to both assessment moments were included in this study. Therefore, all of them kept their jobs despite the uncertainty that crossed all economic and social dimensions of society.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the hosting institution. The study was also approved by the seven organisations involved in data collection. An exhaustive sampling technique was applied to guarantee the participation of all workers of the seven Portuguese organisations involved in the project. Participants were fully informed about the investigation and provided signed informed consent (243), which included detailed information about the project’s aim, participants’ rights, voluntariness, the anonymity of individual responses, and the roles and obligations of the research team. The survey was administered by a member of the research team (first author). The organisations provided a room exclusive for the period of data collection to assure the employees’ physical distance as determined by health authorities.

2.2Measures

Decent Work Questionnaire. The Decent Work Questionnaire (DWQ) is a 31-item questionnaire developed to measure decent work conditions from workers’ perceptions [10]. The DWQ consists of a global decent work score and seven subscales: (1) Fundamental Principles and Values at Work (6 items; e.g., ‘I am free to think and express my opinions about my work’); (2) Adequate Working Time and Workload (4 items; e.g., ‘I consider adequate / appropriate the average number of hours that I work per day’); (3) Fulfilling and Productive Work (5 items; e.g., ‘I consider the work I do as dignifying’); (4) Meaningful Remuneration for the Exercise of Citizenship (4 items; e.g., ‘What I get through my work allows me to live with dignity and autonomy’); (5) Social Protection (4 items; e.g., ‘I feel that I am protected if I become unemployed (social benefits, social programs, etc)’); (6) Opportunities (4 items; e.g., ‘Currently, I think there are work/job opportunities for a professional like me’); and (7) Health and Safety (4 items; e.g., ‘In general, I have safe environmental conditions in my work (temperature, noise, humidity, etc.)’). Each item is answered on a 5-point response scale, ranging from 1 = “I do not agree at all” to 5 = “I completely agree”. In the present study, the Cronbach alpha of the total score was.96 at Time 1 and.95 at Time 2. Reliabilities of the subscales ranged between.79 (Opportunities, Time 1) and.93 (Meaningful Remuneration for the Exercise of Citizenship, Time 1).

Sociodemographic and work-related questionnaire. Sociodemographic and work-related variables were collected using a self-reported questionnaire developed by the authors consisting of 7 questions in Time 1 and 9 questions in Time 2. The responses to the questions were organised categorically. In Time 1 and 2, the sociodemographic variables assessed were age, sex, marital status, and educational level. Regarding work-related variables, in Times 1 and 2, the questionnaire included questions about the type of contract, seniority in the organisation, and seniority in the job function. In addition, the questionnaire in Time 2 also included questions related to the professional situation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically the contract situation and the job function.

2.3Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for the demographic and work-related characteristics of the sample. Repeated-measures univariate and multivariate analyses of variance (ANOVA and MANOVA) were used to examine differences in decent work between Time 1 and Time 2 scores. ANOVAs and MANOVAs were also used to test for time and background variables differences (as between-subject’s factors) in the dimensions of decent work. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 25). For all analyses, a p-value<.05 (two-sided) was set as a criterion of statistically significant difference.

3Results

Of the 243 employees who completed the questionnaires at Time 1 and Time 2, 50.2% were of the female gender, 59.2% were aged between 36 and 55 years, 44.9% were married, 39.9% had a secondary school, and 83.5% reported a permanent job contract. Most participants worked in the organisation and the current job function for under five years (see Table 1). During the pandemic, the contract situation in the organisation remained equal for 236 participants (97.1%) and the job function for 224 participants (92.2%). Thirteen employees (5.2%) reported working from home in Time 2.

Table 1

Demographic and work-related characteristics of the sample

| n | % | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 122 | 50.2 |

| Male | 121 | 49.8 |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 24 | 9.9 |

| 26–35 | 49 | 20.2 |

| 36–45 | 79 | 32.5 |

| 46–55 | 65 | 26.7 |

| +55 | 26 | 10.7 |

| Education | ||

| Basic school | 45 | 18.5 |

| Secondary school | 97 | 39.9 |

| Professional studies | 29 | 11.9 |

| University studies | 72 | 29.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 77 | 31.7 |

| Married | 109 | 44.9 |

| De facto union | 24 | 9.9 |

| Divorced | 25 | 10.3 |

| Widowed | 8 | 3.3 |

| Type of contract | ||

| Permanent | 203 | 83.5 |

| Fixed-term | 38 | 15.6 |

| Training | 2 | 0.8 |

| Seniority in the organisation (years) | ||

| 0–5 | 105 | 43.2 |

| 6–10 | 29 | 11.9 |

| 11–15 | 41 | 16.9 |

| 16–20 | 28 | 11.5 |

| +21 | 40 | 16.5 |

| Seniority in the job function (years) | ||

| 0–5 | 119 | 49.0 |

| 6–10 | 31 | 12.8 |

| 11–15 | 30 | 12.3 |

| 16–20 | 32 | 13.2 |

| +21 | 31 | 12.8 |

In Time 1 and Time 2, the decent work dimension that presented the highest score was Fulfilling and Productive Work. The dimension that presented the lowest score was Meaningful Remuneration for the Exercise of Citizenship. Table 2 shows mean differences (and standard deviations) over time in the seven decent work dimensions and the total score.

Table 2

Comparison of decent work dimensions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | F | ηp2 | |

| Fundamental Principles and Values at Work | 3.42 (0.86) | 3.55 (0.93) | 5.31* | .02 |

| Working Time and Workload | 3.16 (0.88) | 3.35 (0.86) | 8.98** | .04 |

| Fulfilling and Productive Work | 3.59 (0.83) | 3.77 (0.72) | 11.65** | .05 |

| Meaningful Remuneration for the Exercise of Citizenship | 2.74 (1.04) | 2.97 (1.01) | 14.39*** | .06 |

| Social Protection | 2.91 (0.94) | 3.04 (0.88) | 4.18* | .02 |

| Opportunities | 3.29 (0.92) | 3.37 (0.91) | 2.11 | .01 |

| Health and Safety | 3.46 (1.08) | 3.65 (0.94) | 10.89** | .04 |

| Total Decent Work | 3.24 (0.76) | 3.41 (0.73) | 12.84*** | .05 |

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

The results showed a significant multivariate effect of time [Pillai’s Trace = .09, F(7,236) = 3.17; p = .003, ηp2 = .09]. Subsequent univariate tests indicated significant increases in all dimensions of decent work, apart from the dimension Opportunities. Results also revealed a significant increase in the overall score of decent work.

Applying separate MANOVAs with time and background variables [age (≤45 years vs. >45); gender (female vs. male), education (with vs. without higher education), seniority in the organisation (≤5 years vs. >5 years) and seniority in the job function (≤5 years vs. >5 years) as the between-subject factors and the different dimensions of decent work as dependent variables, the results showed did not identify any significant interaction effect between time and the background variables age [Pillai’s Trace = .02, F(7,235) = 0.66; p = .702, ηp2 = .02], gender [Pillai’s Trace = .04, F(7,235) = 1.25; p = .276, ηp2 = .04], education [Pillai’s Trace = .05, F(7,235) = 1.65; p = .122, ηp2 = .05], seniority in the organisation [Pillai’s Trace = .04, F(7,235) = 1.38; p = .213, ηp2 = .04] and seniority in the job function [Pillai’s Trace = .03, F(7,235) = 0.85; p = .547, ηp2 = .03].

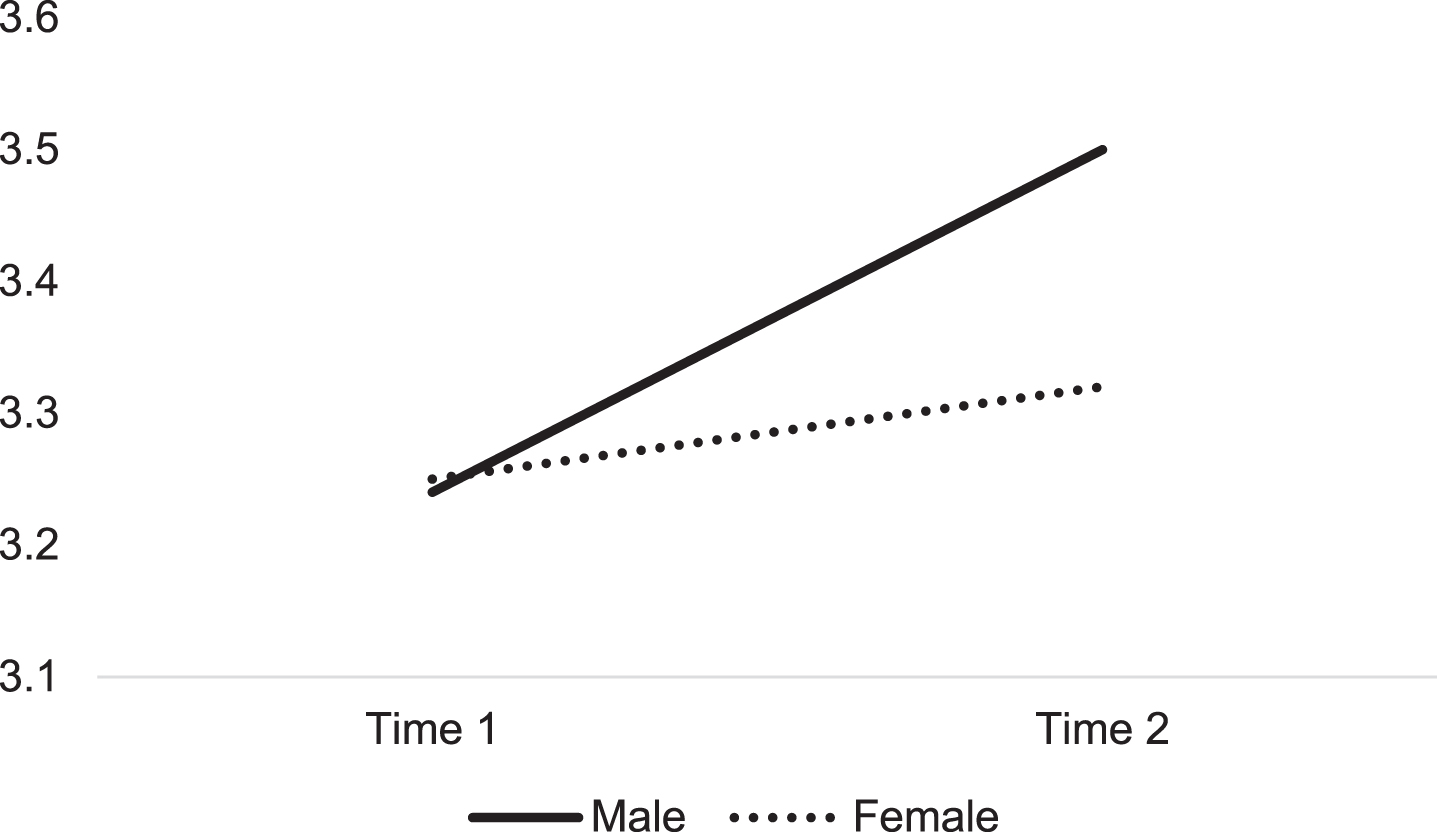

When examining the total score of decent work as dependent variable and time and the background variables as independent variables, the results revealed significant interaction effects only for gender, F(1,241) = 4.28; p = .040, ηp2 = .02. The interaction effect showed that the increase in decent work from Time 1 to Time 2 was statistically significant for men (p < .001), but not for women (p = .264; see Fig. 1). The interaction effect with age [F(1,241)=0.18; p = .669, ηp2 = .001], education [F(1,235) = 1.27; p = .262, ηp2 = .01], seniority in the organisation [F(1,241) = 1.82; p = .178, ηp2 = .01] and seniority in the job function [F(1,241) = 1.68; p = .196, ηp2 = .01] was not significant.

Fig. 1

Mean difference in the total score of decent work by gender and time.

4Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the different dimensions of decent work among Portuguese workers.

Consistent with our hypothesis, our main findings demonstrate a significant improvement in the workers’ perception of decent work from Time 1 to Time 2. This significant increase is only in men. One possible explanation is that during the pandemic, women took on unpaid care for older family members (due to the reduced availability of social services) and children (support for distance learning) [21]. In addition, we verified that the pandemic context had a positive effect on six of seven dimensions of decent work, particularly those related to values, equal opportunities, personal and professional development, work/life balance, improve, and physical and mental health. Opportunities is the only dimension that had no changes from Time 1 to Time 2. Therefore, our hypothesis was partially supported, since Opportunities did not show a statistically significant increase overtime.

A possible explanation for the significant increase in five out of six dimensions of decent work may be grounded on the theories of social comparison [22] and equity [23]. The central explanatory idea of these theories is that individuals assess their work by comparing their jobs with others’ jobs. The societal context six months after the onset of the pandemic was stressful, with many job losses, numerous organisations stopped activity, fear of contamination from a little-known disease, and mobility restraints. However, because our sample includes only Portuguese organisations where the work activity remained the same, and the great majority of employees maintained their jobs in previously existing conditions, it is plausible that their perceptions of decent work may be positively impacted. Furthermore, equity-based reciprocity can influence the perception workers have regarding their work conditions, content and context. Reciprocity was also proposed to explain behaviour in the circular economy context [25].

The social comparison theory argues that people use social reality to adapt their behaviours or opinions and assess themselves through comparison with others [22]. Consequently, by comparing their employment conditions with those who lost their jobs (temporarily or permanently), our workers evaluate their work situation more positively. The equity theory proposes that workers observe what they own in the organisation (e.g., benefits) with their skills, compare themselves with workers who perform the same or similar function, and evaluate through this comparison if they consider it fair [23]. Therefore, considering that our participants may have seen many workers around them as financially fragile, the balance between contribution and remuneration became more favourable to those who maintained their employment conditions. Overall, considering that the work conditions, content, and context remained the same for most of our sample, the workers’ assessment of their decent work significantly increased during the pandemic. That result is not considered a specificity of our sample since equity and reciprocity apply to all human beings. The results can be viewed as a response to the maintenance of the work situation within an overall general decrease in economic and risk conditions. Such a decrease can lead workers to see their same work conditions as better than before since they reframed the evaluation.

Regarding the dimension Fundamental Principles and Values at Work, we observe a significant increase from Time 1 to Time 2. A possible explanation can be that people joined forces to fight the pandemic, as they share the same common goal. This union allowed, on the one hand, the creation of bonds of trust [27, 28] and, on the other, a sense of social identity, having in view its defence against the invisible enemy [24, 29]. This union makes people assess more positively the essential values in the work context (e.g., justice, dignity, freedom, non-discrimination). Thus, when the implemented organisational measures increase the worker’s trust [6], they may perceive work as an expression of their personal values and beliefs [30], having a feeling of justice and dignity, and at the same time, the feeling of safety at work. This feeling of safety also applies to health issues. Indeed, in the present study, the significant increase in the dimension of Health and Safety may be explained by the rapid Portuguese government responses in managing the COVID-19 pandemic [31], which may have predisposed the rapid and appropriate implementation of organisational protective measures. Additionally, the worker’s compliance with health and safety procedures underpins the safety actions and organisational crisis policies [32] by increasing their perception of protection against the additional objective risk.

The significant increase during the pandemic in the dimension Adequate Working Time and Workload may suggest that workers’ flexibilisation of time management during this period was appropriate. A possible explanation is that workers’ perception of their flexibility at work facilitates the work-life balance [33] and helps strengthen trust within the organisations [34]. Despite the restrictions of the coronavirus context, the social isolation in Portugal possibly helped workers rediscover family values and relationships by valuing more unity and time with family [35]. In addition, family closeness increases emotional and psychological well-being among people [36], generating a better reconstruction of their intrinsic resources, which can help to deal with work demands, such as workload [37]. Under the adverse effect of the pandemic on the labour market, our Portuguese organisations ensure their balanced dynamics and work structure. The workers may have perceived that their ability to work at total capacity was not affected. Regardless of the practical job characteristics, workers may derive a meaningful value from their job [38]. The workplace is seen as a community, providing psychological support and a sense of meaning to workers [39], especially in a pandemic context. Additionally, during COVID-19, the social support of the Portuguese Government played a significant role in workers’ resilience and dynamic protective behaviours [40]. Work is a source of motivation and values reflection [30]. As such, Portuguese workers who keep working may perceive more clearly the importance of their work and contribute to the health of the social-economic system and, consequently, of future generations. This may explain the workers’ increased perception of having Fulfilling and Productive Work.

Concerning the significant increase in the dimension of Meaningful Remuneration for the Exercise of Citizenship, a possible explanation may also rely on the theory of social comparison [22], particularly the notion that workers tend to compare their work situation with other workers who are unemployed and lost income. Comparing their job situation with those who experienced a strong diminish in earnings may have positively assessed their work situation. Furthermore, the guarantees of having socially protected employment include remuneration and a social protection system. Indeed, the significant increase in the dimension of Social Protection may be explained by the implementation of a set of exceptional measures by the Portuguese government to support workers and families affected by the pandemic [21]. In this study, the pandemic context did not significantly affect the workers’ assessment of the dimension of Opportunities. These results differ from our expectations, which could be explained by the fact that despite the pandemic context in Portugal affected most sectors of activity, with a substantial reduction in consumption (due to high uncertainty and destruction of jobs) [21], the work activity remained the same in this sample. Thus, the worker’s perception of the availability of alternative job choices was not affected.

Despite the negative changes in the socio-economic context, our subjective measure shows that the positive effect of the social comparison processes [22, 23] and common social identity [24] is stronger than the negative effect of the adverse socio-economic context. Faced with the COVID-19 pandemic, Portuguese workers may have compared their work situation with the situation of other workers, activating an increase in their subjective perception of the value of their current reality. Although workers are officially at higher risk of infection, if organisational efforts to assure workers’ health and safety are recognised, the result of this recognition outweighs the additional risk derived from the virus. Consequently, workers feel better able to protect themselves than they were before. Additionally, being part of a community that experiences the same threatening pandemic context makes salient a common identity that improves workers’ perception of their work. Our findings also reinforce the idea that a component of decent work depends on the socioeconomic context and must be understood in the framework of universal interdependence regarding social and economic issues. While Human Rights and ILO standards of decent work can be considered linked to universal values, our results reinforce the idea that decent work perception (at least in some dimensions) also depends on the socioeconomic context. This study contributes to the literature by extending the research of the interdependence between events that affect the entire population and their different impacts on decent work. As the decent work concept is evolving [41], the assessment made by workers regarding their decent work in a pandemic context brings new knowledge that allows the reinterpretation of the decent work dimensions.

As with all research, this study has limitations that should be considered. First, despite decent work is a global concern, as underlined within the SDG, the specificities of each socio-political and economic country make the comparison between different cultures problematic. For example, while in some countries labour legislation protects and guarantees decent work conditions, in other countries, they are poorly institutionalised [13]. As such, the interpretation of our findings should be done with caution. Second, using an intentional sample of organisations adhering to a change process guided by values, in which almost all workers maintained the same job conditions, limits the findings’ generalizability. Future studies should verify to what extent similar or different results would be obtained with diverse samples in various national contexts. Third, the macro contextual aspects of the pandemic were expected to influence the results more than they did. In future studies it would be valuable to address workers from different sectors of activity as they could express different perceptions. Fourth, although our sample consisted of participants identified as full-time workers, the DWQ covers all employment relationships. Therefore, future studies must consider the diversity of employment situations, both formal and informal work. This study took place in a unique historical moment, and, as such, the possibility of replication is nil. Notwithstanding the preceding limitation, our findings deepen our understanding of this topic by underlining that in adverse moments, the decent work concept may be the key to enabling recovery from and building resilience to crises [3, 42].

5Conclusion

The pandemic is a challenge that mobilises workers to find resources to cope with the stressor context since unexpected changes occurred. Workers seem to reframe how they see their work’s conditions, context and content. The positive effect on workers’ perception of decent work in Portuguese organisations where the work activity remained equal highlights the importance of the rapid government response to manage the pandemic through a robust national plan for crisis management. This reinforces the perspective that the quick and effective government action was positive [43]. The COVID-19 context demonstrates the need for design policies to rapidly allocate resources to the most affected organisations to ensure workers’ jobs [3]. This study suggests the need for further research to analyse the level of access to state-controlled resources and financing to the activity sectors affected by the pandemic. Furthermore, after approving the government’s financial support, politicians must control if organisations maintain the commitments to create jobs and prevent workers’ health risks.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT –Portugal) through the Ph.D. Grant SFRH/BD/130894/2017.

Conflict of interest

The authors contributed equally and significantly to the study, and there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

On July 12, 2018, the Research Ethics and Deontology Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra confirmed that this study meets national and international guidelines for research on humans.

Data availability statement

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Informed consent

Participants were fully informed about the investigation and provided signed informed consent.

References

[1] | Pfefferbaum B , North CS . Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. (2020) ;383: :510–2. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2008017. |

[2] | International Labour Office. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Seventh Edition Updated Estimates and Analysis. 2021. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_767028.pdf |

[3] | International Labour Organization. The likely impact of COVID-19 on the achievement of SDG 8: A trade union opinion survey ILO-ACTRAV. 2021. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—actrav/documents/publication/wcms_770036.pdf |

[4] | Nicola M , Alsafi Z , Sohrabi C , Kerwan A , Al-Jabir A , Iosifidis C , Losifidis C , Agha M , Agha R . The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int J Surg. (2020) ;78: :185–93. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. |

[5] | Cruz LB , Delgado NA , Leca B , Gond JP . Institutional Resilience in Extreme Operating Environments: The Role of Institutional Work. Bus & Soc. (2016) ;55: (7):970–1016. doi:10.1177/0007650314567438. |

[6] | Preti E , Di Mattei V , Perego G , Ferrari F , Mazzetti M , Taranto P , Di Pierro R , Madeddu F , Calati R . The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2020) ;22: (8):43. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z. |

[7] | International Labour Organization. Decent Work. Report of the Director-General at 87th Session of International Labour Conference. International Labour Office. 1999. |

[8] | dos Santos NR . Decent work expressing universal values and respecting cultural diversity: propositions for intervention. Psychologica. (2019) ;62: (1):233–50. doi:10.14195/1647-8606_62-1_12. |

[9] | International Labour Organization. ILO Declaration on social justice for a fair globalisation. International Labour Office. 2008 June. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—cabinet/documents/genericdocument/wcms_371208.pdf |

[10] | Ferraro T , Pais L , dos Santos NR , Moreira JM . The Decent Work Questionnaire: Development and validation in two samples of knowledge workers. Inter Labour Rev. (2018) ;157: (2):243–65. doi:10.1111/ilr.12039. |

[11] | United Nations. United Nations Millennium Declaration: Resolution 55/2 adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 8 Sep. 2000. Declaration. 2000. http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.pdf |

[12] | International Labour Organization. World Employment and Social Outlook. 2015. Retrieved from: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/g |

[13] | Anholon R , Rampasso IS , Dibbern T , Serafim MP , Filho WL , Quelhas OLG . COVID-19 and decent work: A bibliometric analysis. Work. (2022) ;71: (4):833–41. doi:10.3233/WOR-210966. |

[14] | Ferraro T , Dos Santos NR , Moreira JM , Pais L . Decent Work, Work Motivation, Work Engagement and Burnout in Physicians. Int J Appl Posit Psychol. (2020) ;5: :13–35. doi:10.1007/s41042-019-00024-5. |

[15] | Chen SC , Jiang W , Ma Y . Decent work in a transition economy: An empirical study of employees in China. Tech Fore Soc Chang. (2020) ;153: :1–11. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119947. |

[16] | Ferraro T , Moreira JM , dos Santos NR , Pais L , Sedmak C . Decent work, work motivation and psychological capital: An empirical research. Work. (2018) ;60: (2):339–54. doi:10.3233/WOR-182732. |

[17] | Giménez-Espert Md C , Prado-Gascó V , Soto-Rubio A . Psychosocial risks, work engagement, and job satisfaction of nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. (2020) ;8: :566–896. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.566896. |

[18] | Pereira SA , dos Santos NR , Pais L . Decent work’s contribution to the economy for the common good. Int J Organiz Analys. (2019) ;28: (3):579–93. doi:10.1108/IJOA-07-2019-1840. |

[19] | Simonova MV , Sankova LV , Mirzabalaeva FI . Decent work during the pandemic: Indication and profiling matters. SHS Web of Conferences. (2021) ;91: (01020). doi:10.1051/shsconf/20219101020. |

[20] | Wang H , Farokhnia F , Sanchuli N . The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of workers and the associated social-economic aspects: A narrative review. Work. (2023) ;74: (1):31–45. doi:10.3233/WOR-220136. |

[21] | International Labour Organization. Portugal: Uma anaálise raápida do impacto da COVID-19 na economia e no mercado de trabalho. 2020. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—europe/—ro-geneva/—ilo-lisbon/documents/publication/wcms_754606.pdf |

[22] | Festinger L . A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. (1954) ;7: :117–40. doi:10.1177/001872675400700202. |

[23] | Adams JS . Inequity in social exchange. Adv Experimental Psychology. (1965) ;2: :267–99. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60108-2. |

[24] | Tajfel H , Turner JC . An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In W.G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.). Social psychology inter-group relations. 1979;33-47. Brooks/Cole. |

[25] | Davlembayeva D , Papagiannidis S , Alamanos E . Sharing economy platforms: An equity theory perspective on reciprocity and commitment. Journal of Business Research. (2021) ;127: :151–66. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.039. |

[26] | ONUNews. Covid 19 éo maior desafio desta era, diz Guterres à assembleia da OMS [Covid 19 is the biggest challenge of this era, said Guterres to the WHO assembly]. 2020. https://news.un.org/pt/story/2020/05/1713872 |

[27] | Lewin K . Field theory in social science. 1951. Harper. |

[28] | Qian X , Ren R , Wang Y , Guo Y , Fang J , Wu Z , Liu P , Han T . Fighting against the common enemy of COVID- a practice of building a community with a shared future for mankind. Infect Dis Poverty. (2020) ;9: (34):1–6. doi:10.1186/s40249-020-00650-1. |

[29] | Toprakkiran S , Gordils J . The onset of COVID-19, common identity, and intergroup prejudice. J Soc Psychol. (2021) ;161: (4):435–51. doi:10.1080/00224545.2021.1918620. |

[30] | Crayne MP . The traumatic impact of job loss and job search in the aftermath of COVID-19. Psychol Trauma. (2020) ;12: (1):180–82. doi:10.1037/tra0000852. |

[31] | Fernandes N . Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy. IESE Business School Working Paper No. WP-1240-E. 2020 March 22. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3557504 |

[32] | Hu X , Yan H , Casey T , Wu CH . Creating a safe haven during the crisis: How organisations can achieve deep compliance with COVID-19 safety measures in the hospitality industry. Inter J Hospitality Management. (2021) ;92: :102662. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102662. |

[33] | Blair-Loy M . Work without end? Scheduling flexibility and work-to-family conflict among stockbrokers. Work and Occupations. (2009) ;36: (4):279–317. doi:10.1177/0730888409343912. |

[34] | Yunus S , Mostafa AMS . Flexible working practices and job-related anxiety: Examining the roles of trust in management and job autonomy. Econom Indust Democracy. (2021) ;43: (3):1–29. doi:10.1177/0143831X21995259. |

[35] | Adisa TA , Aiyenitaju O , Adekoya OD . The work-family balance of British working women during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Work-Applied Manag. (2021) ;13: (2):241–60. doi:10.1108/JWAM-07-2020-0036. |

[36] | Stieger S , Lewetz D . Parent-child proximity and personality: Basic human values and moving distance. BMC Psychology. (2016) ;4: (26):1–12. doi:10.1186/s40359-016-0132-5. |

[37] | Tussl M , Brauchli R , Kerksieck P , Bauer GF . Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work and private life, mental well-being and self-rated health in German and Swiss employees: a cross-sectional online survey. BMC Public Health. (2021) ;21: :741. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10788-8. |

[38] | Rosso BD , Dekas KH , Wrzesniewski A . On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research Organizational Behavior. (2010) ;30: :91–127. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001. |

[39] | Pratt MG , Ashforth BE . Fostering meaningfulness in working and meaningfulness at work: An identity perspective. In K. Cameron, J.E. Dutton, & R.E. Quinn (Eds.), An introduction to positive organisational scholarship. 2003;309-27. Berrett-Koehler. |

[40] | Fontes A , Pereira CR , Menezes S , Soares A , Almeida P , Carvalho G , Arriaga P . Predictors of Health-Protective and Helping Behaviors during the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Role of Social Support and Resilience. Psychol Rep. 2022; OnlineFirst. doi: 10.1177/00332941221123777. |

[41] | Ferraro T , Pais L , dos Santos NR . Decent work: An aim for all, made by all. Int J Social Sciences. (2015) ;IV: (3):30–42. doi:10.52950/SS.2015.4.3.003. |

[42] | International Labour Organization. Employment and decent work for peace and resilience recommendation (No. 205). 2017. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:R205 |

[43] | Correia P , Mendes I , Pereira S , Subtil I . The Combat against COVID-19 in Portugal: How state measures and data availability reinforce some organisational values and contribute to the sustainability of the national health system. Sustainability. (2020) ;12: :7513. doi:10.3390/su12187513. |