COVID-19 and decent work: A bibliometric analysis

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Among these impacts, those related to the SDG 8 can be highlighted. Consequently, the literature has addressed aspects related to economic growth and decent work.

OBJECTIVE:

This article aimed to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on decent work according to the literature.

METHODS:

For this, a bibliometric analysis was conducted. Data from Web of Science were collected, and VOSviewer software was used to perform the analysis.

RESULTS:

Regarding the results, four main clusters that govern the subject were identified. A first cluster (identified in red) evidenced the consequences of the pandemic to the generation of informal work, increasing poverty and the impacts on gender issues. A second cluster (identified in blue) addresses mental health and stress issues, especially for nurses professionals who experience a situation in the COVID-19 pandemic. The green cluster focused on unemployment, precarious employment, and work conditions, which were highly related to coronavirus contagion. Finally, the yellow cluster evidenced the final consequences when there is a substantial public health problem.

CONCLUSIONS:

The results presented here can be helpful to researchers interested in the, as it allows a broad and condensed view of important information about a relevant topic for sustainable economic development.

1Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have become a global agenda to be achieved by developed and developing countries. This agenda incorporates several issues that address the economic, social and environmental dimensions [1]. In other words, they are goals and targets that seek to address and solve the root causes of poverty, climate change and the need for economic development considering all countries [2, 3]. In an interconnected way, the SDGs continue the Millennium Development Goals. However, SDGs are broader and present a more detailed scope than the Millennium Development Goals. In addition, the SDGs highlight the possibility that different actors establish partnerships allowing greater mobilisation of data, resources and capacity development and technologies, aiming to achieve the mentioned goals [4, 5].

Among the issues addressed in the SDGs agenda and which is characterised as a global concern refers to the promotion of economic growth combined with the guarantee of decent and dignified work (SDG 8). This goal focus on the economic growth that happens without neglecting the promotion of safe work environments, the affirmation and protection of labour rights, the eradication of forced or slave-like labour, among other characteristics [5]. Although different countries have embraced the concerns related to SDG 8, the specificities of each national context, inherent to the socio-political and economic arrangements, become challenges to achieving the goals of SDG8. While in some nation-states, labour legislation is very protective and guarantees decent working conditions, with equal access to women and minorities, in other conditions are poorly institutionalised. This inequality of contexts puts as a starting point some difficulties and discrepancies in the capacity for minimum and equal fulfilment of these goals. The battle against child labour, in favour of minimum conditions of healthy work, with rest periods and with social security contributions for retirement, and in favour of equal access and with the same conditions for men, women and minorities, is still a reality for several countries [6–10].

In addition to these challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic has considerably aggravated the global economic, social and sanitary situation and increased the uncertainty of SDGs achievement, including those related to SDG 8 [3]. It is worth remembering that the labour market, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, was strongly affected by measures of social distancing and by reducing people’s displacement, actions taken to contain the virus. However, because of these actions, there was an economic downturn, the closing of companies, and a reduced number of jobs in different world regions. Workers accumulated debts while the prices of essential products increased and reduced exports and imports [11, 12]. Rocha et al. [13] argued that informal work was an alternative for families income and survival in several regions.

Nevertheless, this kind of job is generally developed in precarious conditions, without guarantees of labour rights, welfare benefits and, sometimes, without regulation. Concerns related to the financial situation of families, which generates significant problems of anxiety and depression, as exemplified in some recent studies [14–17]. Recent studies such as those by Alonzo et al. [18] show the remarkable impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of vulnerable families. Due to financial insecurity and constant fear of unemployment, parental stress is a problem that, if left unresolved, can result in even more significant psychological distress and maltreatment of the children in the family. The pandemic affected individuals and entire families/communities and poses a more significant burden for families with children. The results indicate that the stress level for parents is significantly higher than for families and individuals without children. As the authors show, this is especially important given the relationship between parental stress and child abuse, neglect and family violence.

According to Sprague et al. [12], different world regions were affected by the consequences of the pandemic. The most significant impact in crises always affects the most marginalised workers, who do not have access to labour rights. The pandemic consequences for work concerning gender inequalities should also be highlighted [19]. Although the target 8.5 focuses on full and decent employment for all women and men, women, in general, are being the most affected workers by the pandemic negative consequences. For example, the study of Seck et al. [19] compared the pandemic impact on work carried out by men and women in 11 Asia-Pacific countries. In general, women lost their livelihoods more quickly and were more affected by mental illness due to the consequences of the pandemic.

Taking the Latin America and Caribbean region as an example, the COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated existing problems. According to the report produced by Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe [20] (in English, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean), before 2020, the region was affected by slow economic growth, increased unemployment and reduction of industrial production. During the pandemic, there was an increase in unemployment in the search for informal work and, consequently, an increase in poverty and lack of basic rights guarantee [21]. The SGDs agenda is further away from being achieved, especially regarding the targets related to decent work and economic growth. In some countries, public indebtedness will compromise programs that focus on SDG 8 targets, as in Brazil, according to Anholon et al. [22]. A similar situation occurs in other regions and countries of the world.

In this context, it is interesting to map the scientific production generated during 2020 and 2021 on “decent work” in the COVID-19 pandemic context to identify thematic groupings, co-occurrence relationships of words between other aspects, as this type of study can significantly contribute to the evolution of debates on this important topic. Since no similar study was found in the literature, we defined our research gap. We selected the Web of Science base as a source for data collection and VOSviewer software as the analysis tool. These choices provided a better research scope.

Besides this introduction, which also presents the theoretical background on the topic, this article presents three more sections. Section 2 is dedicated to presenting the methodological procedures, enabling other researchers to replicate the study. In section 3, the results are shown as well as the related debates. Section 4, for its turn, finalises the presented discussions, mentioning the study’s main conclusions.

2Methodological procedures

As presented in Fig. 1, the first step of this research was to conduct a bibliographic analysis of the literature related to decent work, SDG 8 and the effects of COVID-19 on them to establish a theoretical background on the subject.

Fig. 1

Steps performed in this research.

In the second step, data search was performed using the string: (“SDG8” OR “SDG 8” OR “decent work” OR “decent job” OR “decent employment” OR “informal job” OR “informal work” OR “informal employment” OR “precarious employment” OR “precarious work” OR “precarious job” OR “employment conditions” OR “work conditions” OR “job conditions”) AND (“COVID-19” OR” COVID” OR” Coronavirus” OR “pandemic”), as topics, in the Web of Science database. This search resulted in a total of 108 documents. The search was conducted on May 20, 2021, without restrictions on publication data. An initial screening of these 108 documents resulted in the exclusion of 36 items out of the scope of this research. From the selected 72 documents (Appendix), there were 62 articles, five editorials, and five reviews. All these documents were considered in the analysis.

Besides data provided by the Web of Science database, the software VOSviewer was used. VOSviewer is a useful software for bibliometric analysis, presenting maps for network visualisation van Eck and Waltman [23]. The software is used in several studies to obtain an overview of specific themes [24]. The inputs can be done from Scopus and Web of Science; alternatively, data can be imported. RIS files, RefWorks, EndNote and via APIs van Eck and Waltman [25]. In this research, data were imported to VOSviewer from the Web of Science database.

In this research, the data was imported from the Web of Science database. After an initial screening of data in VOSviewer to list the words to be considered in the analysis, a “Thesaurus” file was created to group similar terms, as explained by van Eck and Waltman [25], such as synonyms, plural and singular, spelling differences, among others. As an example, it can be mentioned the unification of “COVID-19 pandemic”, “COVID-19”, and “19 pandemic” to “COVID-19”. Using this “Thesaurus” file (in the “full counting” method), the following analyses were performed, through the analysis options presented by the software: 1) Co-occurrence network of the publications; 2) Co-occurrence network, considering publication data average; 3) Co-occurrence network, considering density analysis; 4) Countries network. It should be highlighted that the terms co-occurrence analyses considered at least four occurrences to be accounted for. Based on these maps generated in VOSviewer, several interesting themes related to SDG 8 emerged and allowed us to better understand the subject during the COVID-19 pandemic context.

3Results

Before presenting the analyses performed, an interesting fact should be observed. Although data collection was conducted on May 20, 2021, the number of 2021 (57%) publications was higher than the number of publications in 2020 (43%), which shows the increasing relevance and concern of the discussion.

Considering the publications analysed, the journals that present the highest number of documents are the “International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health” (4 publications), “Feminist Economics” (4 publications), and “Revista Pegada” (3 publications). The journals “World Development”, “BMC Public Health”, “Ciencia & Saude Coletiva”, “Journal of Vocational Behavior”, “International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy”, “Frontiers in Psychology”, “International Journal of Health Planning and Management”, and “Frontiers in Public Health” presented two publications each. All the other journals have just one publication.

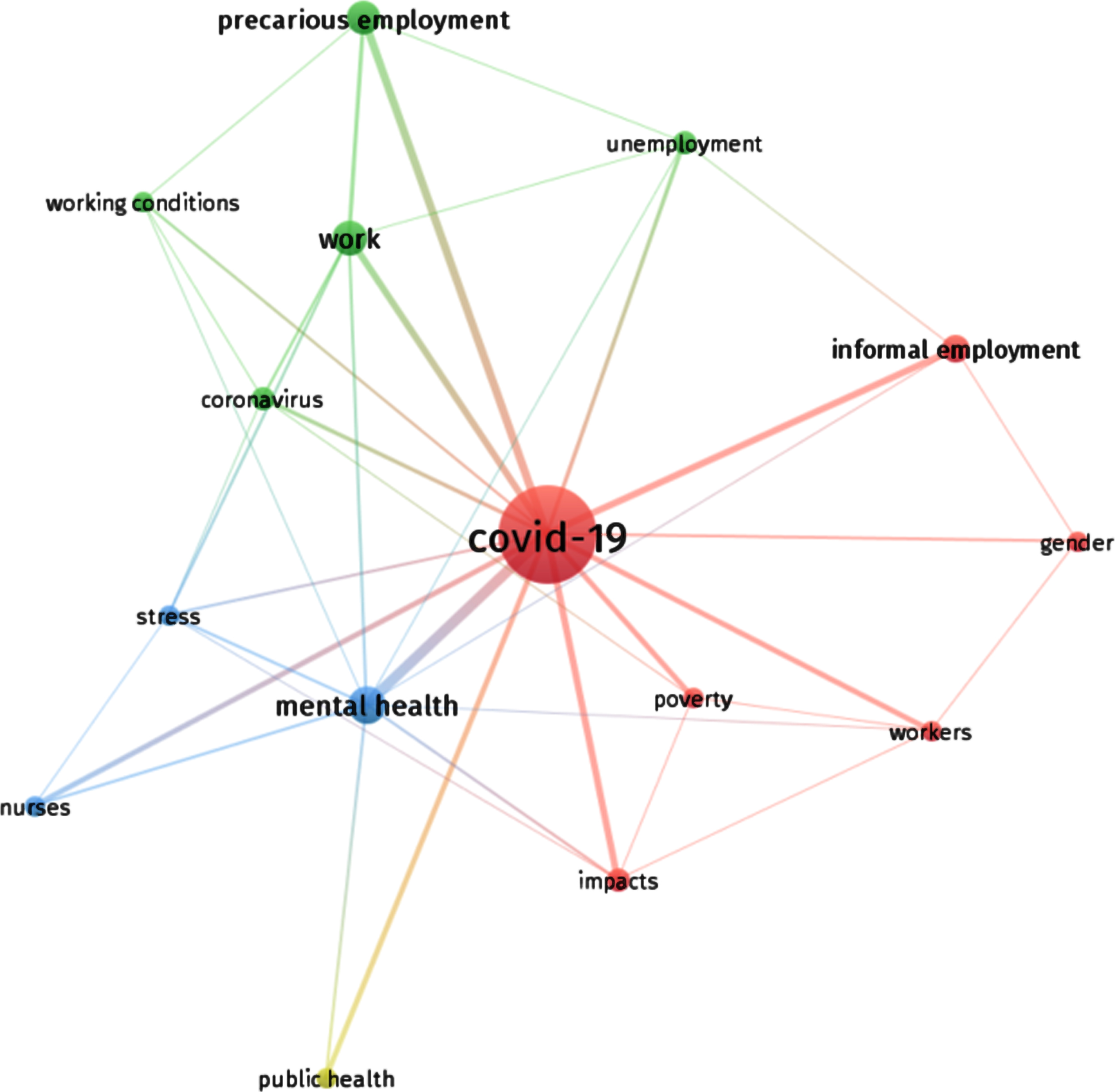

As previously mentioned, the minimum occurrence for terms analysis was 4. At first, the co-occurrence network of words in the sample was analysed. The output of this analysis from VOSviewer software is shown in Fig. 2. As expected, the term “COVID-19” was a central word, connected with all other words present in the figure. It is possible to verify four clusters of words. The visualisation of the clusters becomes easier through the thermal map presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2

Co-occurrence network. Source: Data generated from Vosviewer.

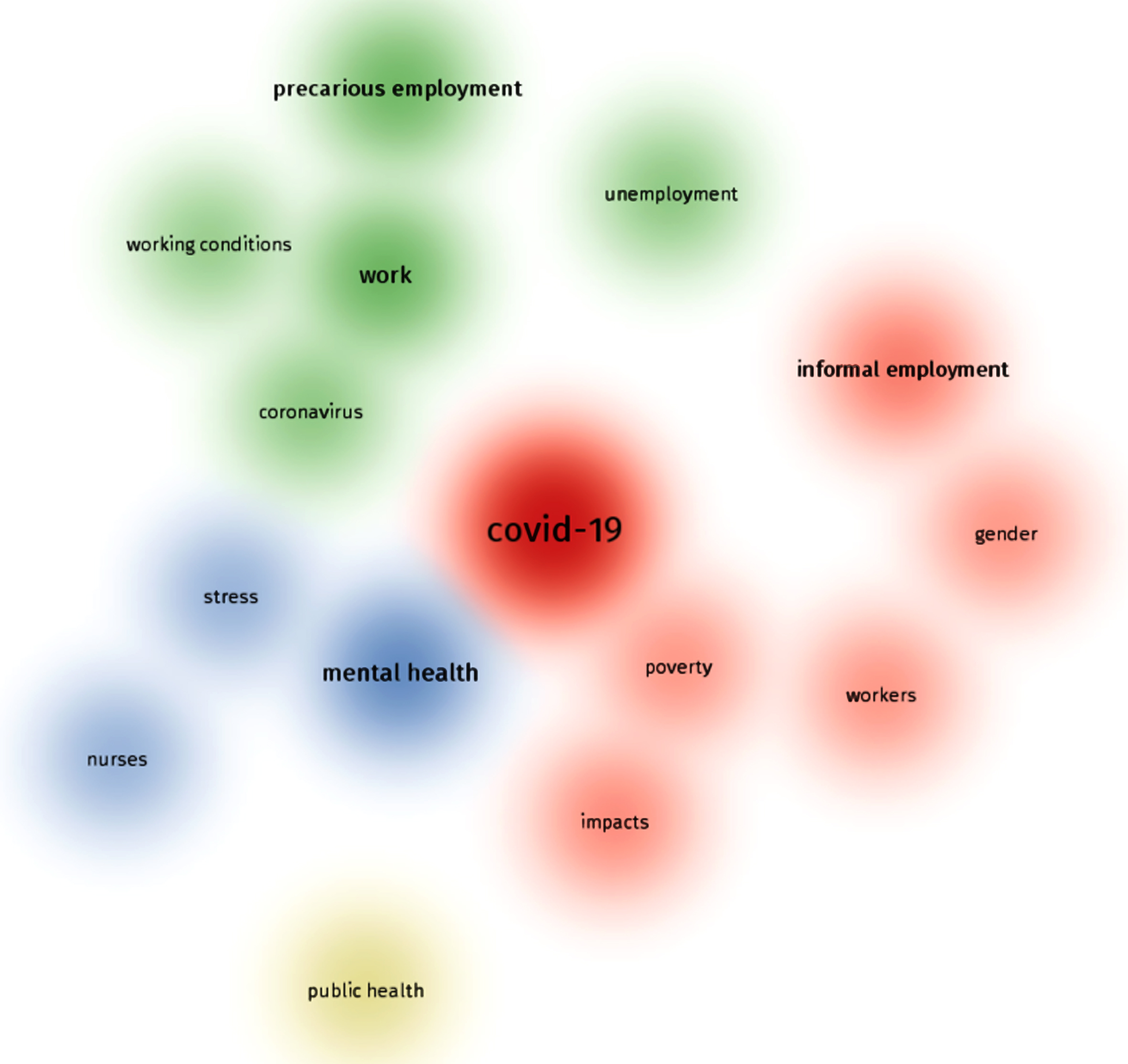

Fig. 3

Co-occurrence network, considering density analysis. Source: Data generated from Vosviewer.

The red cluster “COVID-19” is connected with “informal employment”, “gender”, “workers”, “poverty”, and “impacts”. Although there are some connections between these other words, the most relevant links are those between these words and “COVID-19”, showing a clear connection between these themes. The cluster content follows the authors’ statement [11, 12]. Throughout the pandemic, many companies’ bankruptcies, job reductions, layoffs, and, consequently, people started to glimpse informal employment as a form of survival [13]. Furthermore, from some articles analysed in this cluster [19, 26, 27], women suffer much more from the impacts of this situation. Working women experienced more unemployment and leaves than men. On the other hand, married workers had more adverse results than single workers. Another impact is the concentration of women in paid and unpaid care duties as the main explanation for the gender disparities.

The cluster highlighted in blue has the words “stress”, “mental health”, and “nurses”. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people became afraid to be infected with the virus, causing a stressful situation for everyone. Additionally, the labour instabilities, possibility of job loss and, in some cases, difficulties in honouring financial debts aggravated anxiety and depression crises. These situations of great uncertainty and low degree of governability increased anxiety, depression and other mental illnesses, as mentioned by some studies [14–16]. Specifically, regarding nurses professionals, the pression suffered by this group of workers during the COVID-19 pandemic should be emphasized; not necessarily regrading to informal work, but related to stressful situations (unideal conditions to exercise the profession, high risk of coronavirus infections, daily high-level of stress). The health of nurses throughout the COVID-19 pandemic is discussed in the Bitencourt and Andrade [14] study.

In the green cluster, it is observed the terms “working conditions”, “precarious employment”, “work”, “coronavirus”, and “unemployment”. In addition to the precarious working conditions, no guarantees of labour rights, welfare benefits and regulations, as pointed out by Rocha et al. [13], the chances of contracting the coronavirus in such situations end up being higher. The COVID-19 pandemic caused changes in working arrangements (e.g., short-term work, location and flexible hours) for workers in a formal employment relationship. However, it is undeniable that the most significant impact was caused to self-employed workers; that is, the conditions of these workers became even more evident. These workers were not officially laid off nor received paid sick leave, unemployment insurance or other financial aid programs, leaving them even more unprotected during the COVID-19 pandemic [28].

As pointed out by Webb et al. [29], another aspect worth mentioning refers to the impacts of informal economic activities. The negative consequences of actions and informal work considering the individual implications (with precarious work without rest time without guaranteed minimum rights, among others), the reduction of taxes and fees collection process of the activities (that are not accounted for and therefore reduce public revenues), and a decrease in the state’s capacity to provide public goods and services, including social protection, as a result of the non-collection of public revenues.

The pandemic situation has considerable implications for the informal employment and the informal economy, accentuating the existing tensions arising from concerns of informal workers more job security. Although extremely painful in many areas of life in society, the current context can force new solutions to better protect basic worker safety while also should help organisations to remain competitive. It is necessary to advance the implementation of SDG 8, which deals with work decent. In this sense, it is urgent to discuss and implement government policies to support job security, income, formalisation of employment and justice for informal employees [29–31].

Finally, the term “public health” should be mentioned in the yellow cluster (considering the cutoff frequency is the core of the cluster). The degradation of decent work conditions leads to many other problems of different orders for the population. Ultimately, this generates severe consequences for public health, such as an increase in the number of cases of anxiety and depression among workers, as highlighted [14–16]. As we have seen in previous clusters, the performance of the public health system was highly affected not only because of the health crisis, but also the COVID-19 pandemic leveraged an economic and social crisis without precedent [28, 31].

The economic downturn has brought severe damage both from an individual and institutional point of view. From the individual point of view, much research indicates that the most significant impact of the pandemic and the loss of lives is the mental health of citizens. Workers exposed to severe stressors and dramatic life changes are inserted into “diseases of despair” [31–33]. Some stressors can lead to an increase in the abuse of alcohol and other substances and also suicide attempts [32, 33].

In turn, from an institutional point of view, considering the public health system, rising unemployment and informal work, as well as reducing the work hours of the self-employed, reduce the injection of resources into the economy and the capacity of public revenues, affecting public services and more directly the public health services [29, 30]. This scenario points to the importance of research, scientific evidence and government measures to handle these situations swiftly. Therefore, it is important to recognize public health, which is collapsing, as an embedded social problem in a broader protection system. Thus, understanding that pandemic consequences will have to be addressed comprehensively and cross-sectorally, aligning the precepts of human and integral health and decent work [28–31].

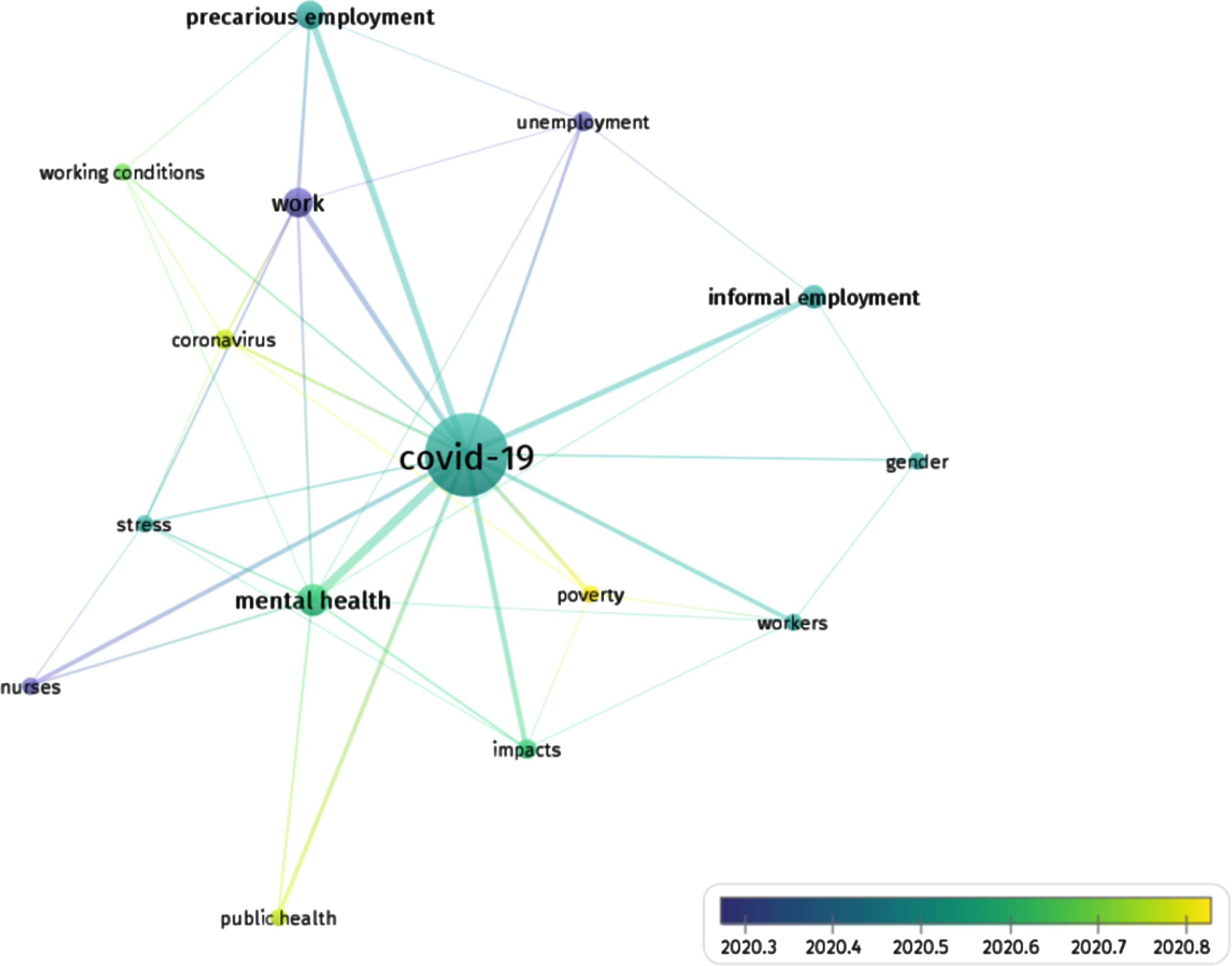

Figure 4 shows the average publication date of the documents in which the terms presented in Figure 2 appear. Thus, it is possible to verify that at the beginning of the pandemic, debates about decent work/SDG8 were directed towards work, unemployment, and the work of nursing professionals. During the pandemic, issues of gender, mental health, precarious employment, working conditions and stress started to be debated. Finally, in the last phase analysed in this research, poverty and public health conditions began to be focused.

Fig. 4

Average date of terms present in documents analyzed with the frequency of co-occurrence greater than 4. Source: Data generated from Vosviewer.

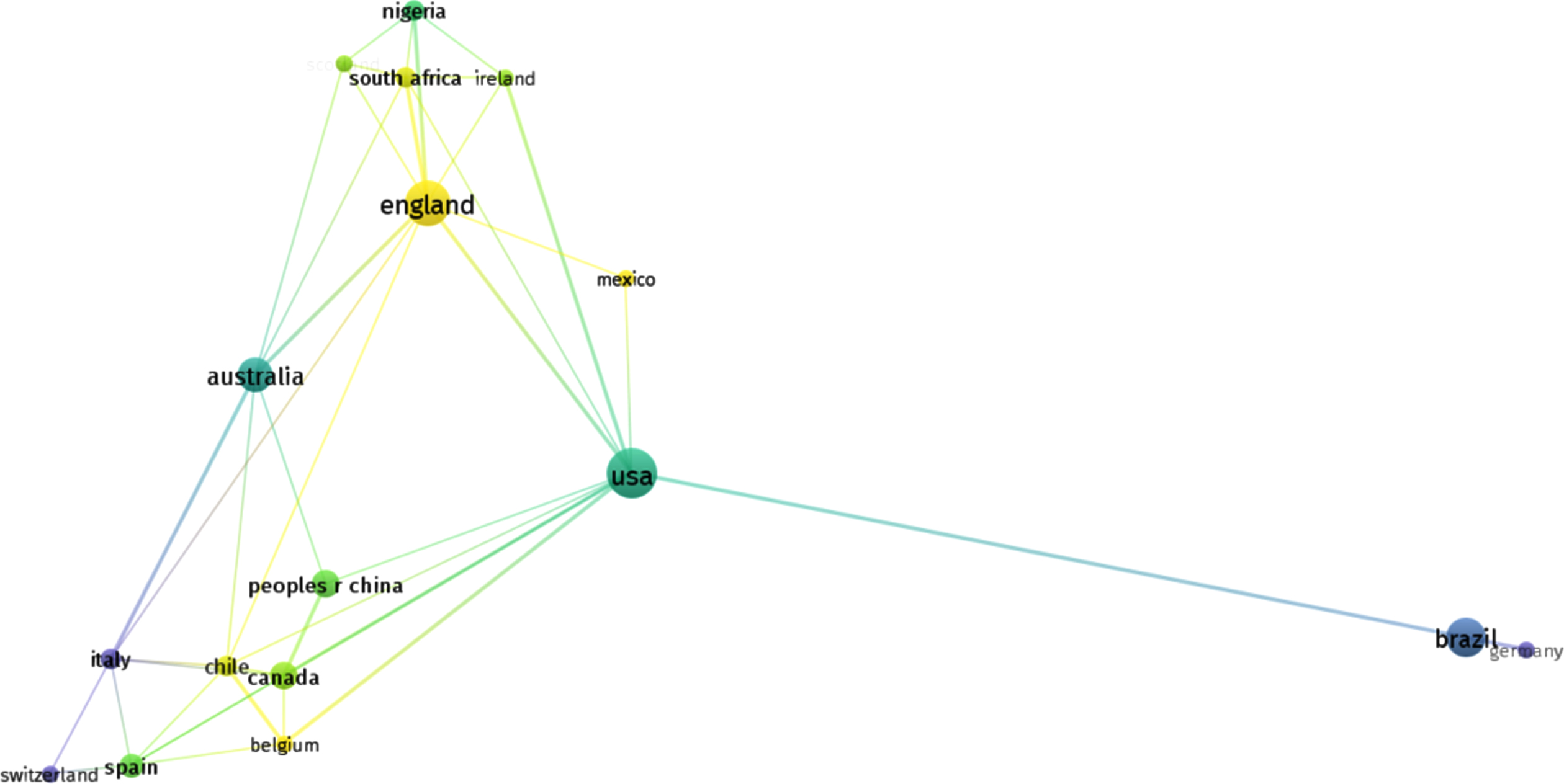

Finally, in Fig. 5, the co-authorship network is shown regarding countries in the analysed documents. The United States of America stands out as the centre of that network.

Fig. 5

Co-authorship for countries: Data generated from Vosviewer.

4Conclusions and final considerations

This study aimed to carry out a scientific mapping on theme decent work throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and, considering the results presented; the main objective was achieved.

The main conclusion is that four main clusters govern the subject. A first cluster (identified in red) evidenced the consequences of the pandemic to the generation of informal work, increasing poverty and the impacts on gender issues. A second cluster (identified in blue) addresses mental health and stress issues, highlighting exceptional nurses professionals who experience a problematic situation in the COVID-19 pandemic. The green cluster focused on unemployment, precarious employment and work conditions, which were highly related to the probability of coronavirus contagion. Finally, the yellow cluster evidenced the final consequences when there is a substantial public health problem.

The economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has brought severe damage from an individual and institutional point of view. Many studies indicate that the most significant impact of the pandemic, in addition to the loss of life, is the mental health of workers, unemployment, the precariousness of flexible work and the social, economic and health vulnerability of the most vulnerable families. Some of these stressors lead to many people experiencing the “diseases of despair” [31–33]. The increase in unemployment and informal work, in turn, reduces the injection of resources into the economy and the capacity for public collection, affecting not only the consumption capacity and the heating of industries and services, but also affects the financing capacity of public services, including health.

The current scenario points to the importance of research, scientific evidence and government measures to deal with these situations quickly. The SDGs must be strengthened and recognised as a comprehensive plan to “out” the consequences of the pandemic COVID-19, which will put us in a different scenario in which we found ourselves before 2020. Only reach heights of more humane and sustainable civilisation merger with Agenda 2030 as a window of opportunity to revisit our development trajectory.

Finally, every study has some limitations and we presented here the limitations of this study. The first is that the analysis was performed considering the Web of Science database; despite being considered one of the most important scientific bases globally, there are others. Also, different search terms can lead to different articles in the selection process phase. Regarding practical implications, we understand that the results presented here can be helpful to researchers interested in the theme since we presented condensed information about a relevant topic for sustainable economic development. As future research, we recommend conducting studies in each country to understand better how the COVID-19 pandemic influenced decent work issues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001; processes 88887.464433/2019-00 and 88887.339816/2019-00; Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) 307536/2018-1.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

Supplementary materials

[1] The appendix is available from https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/WOR-210966.

References

[1] | Sachs JD , Schmidt-Traub G , Mazzucato M , Messner D , Nakicenovic N , Rockström J . Six transformations to achieve the sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. (2019) ;2: :805–814. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0352-9. |

[2] | Leal Filho W , Tripathi SK , Andrade Guerra JBSOD , Giné-Garriga R , Orlovic Lovren V , Willats J . Using the sustainable development goalstowards a better understanding of sustainability challenges. Int. J.Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. (2019) ;26: :179–190. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2018.1505674. |

[3] | Fenner R , Cernev T . The implications of the Covid-19 pandemic fordelivering the Sustainable Development Goals. Futures. (2021) ;128: :102726. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2021.102726. |

[4] | Leal Filho W . Viewpoint: accelerating the implementation of the SDGs. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. (2020) ;21: :507–511. |

[5] | United Nations The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. |

[6] | Tur-Sinai A . Labor-market mobility among persons with disabilities. Work. (2019) ;64: ;323–340. doi: 10.3233/WOR-192995. |

[7] | Cavalcante SR , Vilela RAV . Children and teenagers working in artistic labor: Brazilian situation and international examples. Work. (2012) ;41: :933–940. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0266-933. |

[8] | Nair AG , Jain P , Agarwal A , Jain V . Work satisfaction, burnout and gender-based inequalities among ophthalmologists in India: A survey. Work. (2017) ;56: :221–228. doi: 10.3233/WOR-172488. |

[9] | Cronin S . Reflections on gender issues in work transitions in Chile. Work. (2013) ;44: :89–91. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-01567. |

[10] | Wang M-L , Hsieh Y-H . Do gender differences matter to workplacebullying? Work. (2016) ;53: :631–638. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152239. |

[11] | Bárcena AC . The global economy and development in times of pandemic: the challenges for Latin America and the Caribbean. CEPAL Rev. 2021:132. |

[12] | Sprague A , Raub A , Heymann J . Providing a foundation for decent work and adequate income during health and economic crises: constitutional approaches in 193 countries. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy. (2020) ;40: :1087–1105, doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-07-2020-0358. |

[13] | Rocha R , Atun R , Massuda A , Rache B , Spinola P , Nunes L , Lago M , Castro MC . Effect of socioeconomic inequalities and vulnerabilities on health-system preparedness and response to COVID-19 in Brazil: a comprehensive analysis. Lancet Glob. Heal. (2021) ;9: :e782–e792. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00081-4. |

[14] | Bitencourt SM , Andrade CB . Trabalhadoras da saúde face àpandemia: por uma análise sociológica do trabalho decuidado. Cien. Saude Colet. (2021) ;26: :1013–1022, doi: 10.1590/1413-81232021263.42082020. |

[15] | Barello S , Falcó-Pegueroles A , Rosa D , Tolotti A , Graffigna G , Bonetti L . The psychosocial impact of flu influenza pandemics on healthcare workers and lessons learnt for the COVID-19 emergency: a rapid review. Int. J. Public Health. (2020) ;65: :1205–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01463-7. |

[16] | Babulal GM , Torres VL , Acosta D , Agüero C , Aguilar-Navarro S , Amariglio R , Ussui JA , Baena A , Bocanegra Y , Brucki SMD , et al. Theimpact of COVID-19 on the well-being and cognition of older adultsliving in the United States and Latin America. EClinicalMedicine48. (2021) ;35: :100848, doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100848. |

[17] | Dogru-Huzmeli E , Cam Y , Urfali S , Gokcek O , Bezgin S , Urfali B , Uysal H . Burnout and anxiety level of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Work 2021;1-9, doi:10.3233/WOR-210028. |

[18] | Alonzo D , Popescu M , Zubaroglu Ioannides P . Mental health impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on parents in high-risk, low income communities. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021;002076402199189, doi:10.1177/0020764021991896. |

[19] | Seck PA , Encarnacion JO , Tinonin C , Duerto-Valero S . Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 in Asia and the Pacific: Early Evidence on Deepening Socioeconomic Inequalities in Paid and Unpaid Work. Fem. Econ. (2021) ;27: :117–132. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2021.1876905. |

[20] | CEPAL La Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible en el nuevo contexto mundial y regional: escenarios y proyecciones en la presente crisis 2020. |

[21] | Foreignaffairs Latin America’s Lost Decades Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/southamerica/2020-12-08/latin-americas-lost-decades (accessed on Mar 23, 2021). |

[22] | Anholon R , Rampasso IS , Martins VWB , Serafim MP , Leal Filho W , Quelhas OLG . COVID-19 and the targets of SDG reflections on Brazilian scenario. Kybernetes. (2021) ;50: :1679–1686, doi: 10.1108/K-12-2020-0833. |

[23] | van Eck NJ , Waltman L . Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics. (2010) ;84: :523–538. doi: 10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3. |

[24] | Sharifi A . Urban resilience assessment: mapping knowledge structure and trends. Sustainability. (2020) ;12: :5918, doi: 10.3390/su12155918. |

[25] | Van Eck NJ , Waltman L . VOSviewer Manual –Manual for VOSviewer version 1.6.16; Leiden University: Leiden, 2020. |

[26] | Ham S . Explaining Gender Gaps in the South Korean Labor MarketDuring the COVID-19 Pandemic. Fem. Econ. (2021) ;27: :133–151. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2021.1876902. |

[27] | Yildirim TM , Eslen-Ziya H . The differential impact of COVID-19 on the work conditions of women and men academics during the lockdown. Gender, Work Organ. (2021) ;28: :243–249. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12529. |

[28] | Spurk D , Straub C . Flexible employment relationships and careers in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Vocat. Behav. (2020) ;119: :103435, doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103435. |

[29] | Webb A , McQuaid R , Rand S . Employment in the informal economy: implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy. (2020) ;40: :1005–1019, doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-08-2020-0371. |

[30] | ILO COVID-19 and the world of work. Seventh edition Updated estimates and analysis Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_767028.pdf (accessed on Sep 1, 2021). |

[31] | Matilla-Santander N , Ahonen E , Albin M , Baron S , Bolíbar M , Bosmans K , Burström B , Cuervo I , Davis L , Gunn V , et al. COVID-19 and Precarious Employment: Consequences of the EvolvingCrisis. Int. J. Heal. Serv. (2021) ;51: :226–228. doi: 10.1177/0020731420986694. |

[32] | Clay JM , Parker MO . Alcohol use and misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: a potential public health crisis? Lancet Public Heal. (2020) ;5: :e259, doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30088-8. |

[33] | Holmes EA , O’Connor RC , Perry VH , Tracey I , Wessely S , Arseneault L , Ballard C , Christensen H , Cohen Silver R , Everall I , et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) ;7: :547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. |