Employment and gender inequalities: Towards a more cohesive and gender-neutral transport sector in Portugal1

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Historically, the transport sector has been male-dominated in all countries, including Portugal. In recent years, Portugal has struggled to balance the proportion of men and women working in the transport sector through policies, programs, and awareness campaigns. In most cases, the overall impact has been rather unsatisfactory, questioning the necessity of introducing other methods and strategies.

OBJECTIVE:

The main objectives were to assess the existing gender inequalities in the Portuguese transport sector labour market, identify the causes, and propose guidelines and possible solutions towards a more inclusive and gender-neutral society.

METHODS:

Using both qualitative and quantitative methods, the methodological background of this research is divided into three main parts: (i) a literature review of academic publications, reports, and laws in the European and Portuguese context, (ii) semi-structured interviews with representatives of two Portuguese transport companies, and (iii) statistical analysis compiling data from European and national official sources.

RESULTS:

There is evidence of differences in opportunities between women and men, starting with lower mobility and access to the labour market. Some companies in the sector have already recognised the existence of asymmetries and have introduced policies and measures to reduce them. Nonetheless, the actions already implemented have not led to the expected results.

CONCLUSION:

More governmental and institutional attention should be provided to develop gender-neutral employment policies for the transport sector and more accurate gender equality measures and instruments to change the status quo are needed. This paper presents a series of recommendations for better governance of gender inequalities in the Portuguese transport labour market.

1Introduction

Over the years, women’s employment especially in male-dominated sectors has been the subject of a wide variety of studies and analyses, particularly examining gender-related issues in health and working conditions [1–4]. Gender inequalities are noteworthy in most countries [5] and consequently reflected in the world of work, for example through gender pay gaps [6–8].

Mobility is an essential human activity and plays an important role in the citizens’ quality of life [9–12] contributing to territorial and social cohesion. Additionally, this sector is a powerful engine of business and economic development, both in terms of transporting people and goods [13].

At the European level, the transport sector directly employs around 10 million people and accounts for about 5% of GDP [14]. Many European companies operating in this sector are world leaders in infrastructure, logistics, traffic management systems and the manufacture of transport equipment. Specifically, in Portugal, the transport and storage sector represented, in 2017, around 4% of companies (16,000), 3% of the national trading volume (12 billion euros), and 4% of the total number of persons employed [13], however, this value is not equal in gender.

Currently, despite advances in gender equality, the labour market of the Portuguese transport sector still presents discrepancies. Achieving gender equality is both an individual and a collective commitment. Struggles to make this sector more appealing to women include considerations of training, learning and professional development, adaptable working conditions, workplace safety, and the possibility of balancing professional, personal, and family life. Nevertheless, the advances achieved are unsatisfactory and unequal among the transport sector companies.

Against this background, the main objectives of this research were to assess the existing gender inequalities in the Portuguese transport sector labour market, identify and research their causes, and propose guidelines and possible solutions towards a more inclusive and gender-neutral society.

In the first part of the paper, the research has been framed against the European and Portuguese contexts regarding gender inequalities in the employment labour force, and in the transport sector in particular. This has helped to understand the factors that led to the current situation, not only at the European level, but also in Portugal.

The second part highlights the existing policies and measures that have been implemented in Portugal in order to reduce gender inequalities, women’s position within the Portuguese transport sector, as well as empirical evidence regarding how Portuguese transport companies have been fighting to reduce the segregation of jobs and gender inequalities.

The third part emphasizes the main barriers to women’s career progression and a set of recommendations aiming at reducing gender inequalities in the transport sector, while the conclusions suggest that more governmental and institutional attention should be paid to develop better gender-neutral employment policies and measures.

2Materials and methods

The research material consisted of national policies and European and national statistical analyses, information from Portuguese companies in the sector, and both international and national literature. European open-access statistical data were obtained from Eurostat, while national statistics were obtained from the National Statistics Institute (INE) [15] and PORDATA [16]. Data related to the Portuguese transport companies were obtained through semi-structured interviews conducted by telephone in December 2020 and January 2021 with two national rail companies, namely Fertagus (a commuter rail operator in Lisbon Metropolitan Area) and MTS – Metro Transportes do Sul (a light rail network that operates in the suburban of Lisbon), and sustainability reports from other companies of interest for the topic. It is worth noting that other national transport companies were contacted without success.

In order to obtain a reference of the current situation of this sector in relation to gender inclusion, to illustrate the problems women have experienced and highlight good practices, the semi-structured interview included four main topics: (i) evolution of employees by gender and professional category, (ii) absenteeism by gender and professional category, (iii) policies/measures implemented to promote equal opportunities and women’s response to professional categories traditionally occupied by men, and (iv) measures and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by gender.

3Employment and gender inequalities

3.1A European perspective

The transport sector is a traditionally male-dominated one, both from an employment point of view and for the values it embodies. It has the stigma of being dominated by a “macho” culture and it has been regarded as “no place for women” [17]. In global terms, on average, less than 20% of the transport workers are women [18].

According to the European Commission, the transport sector in Europe is not gender-balanced. Female employees represent only 22% of the workforce [19]. In addition, according to the European Institute for Gender Equality [20], men earn more than women in every occupation. On average, in Europe, women are paid 16.4% less than men per hour of work.

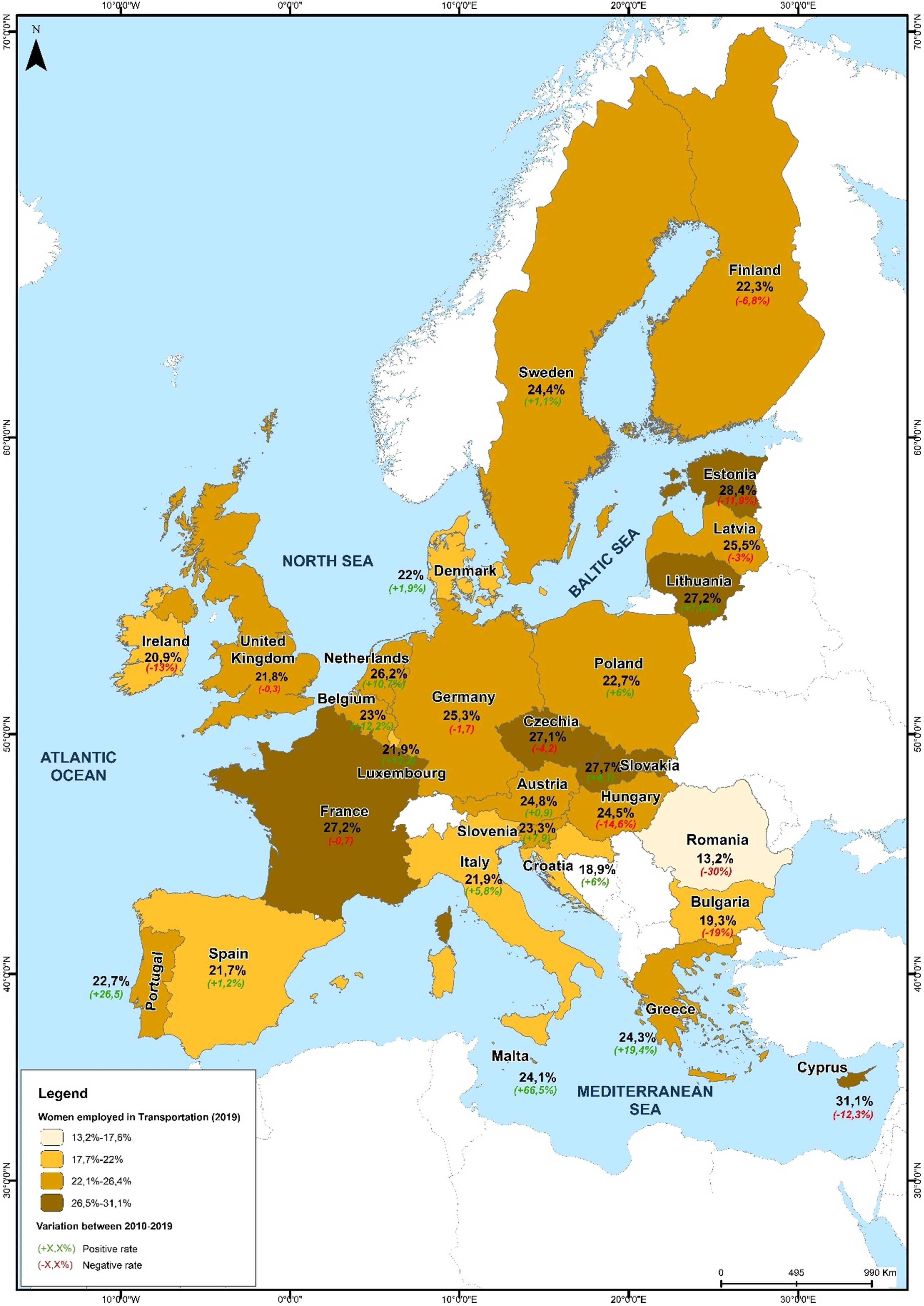

Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of women employed in the transport and storage sector compared to the total employment in this sector in all European Union countries in 2019. Within this context, Cyprus (31.1%), Estonia (28.4%), Slovakia (27.7%), France (27.2%), Lithuania (27.2%) and Czech Republic (27.1%) emerge as the countries with the highest female participation in the transport labour market. On the contrary, Romania (13.2%), Croatia (18.9%) and Bulgaria (19.3%) are the countries with the lowest percentages of women employed in the transport and storage sector at the end of 2019. In the same year, Portugal is ranked 17th among the European Union countries, with 22.7% of women working in the transport and storage sector.

Fig. 1

Percentage of female workers within the transport sector in the European Union countries. Data source: Eurostat, 2019.

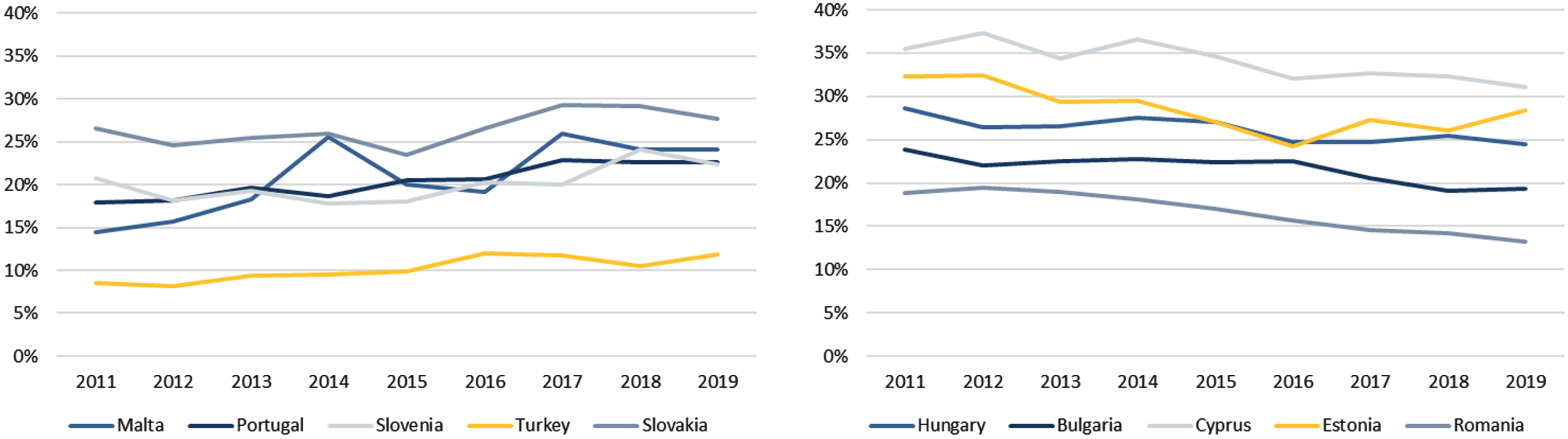

Figure 2 presents the top five countries with upward (left) and downward (right) trends regarding the participation of female workers in the transport sector. We analysed data from 2010 to 2019 and countries were ranked by the slope of the time series regression.

Fig. 2

Top five countries with most upward and downward trends. Data source: Eurostat, 2019.

Malta is the country with the fastest growth rate of women in the transport sector (approximately 1.21% per year), followed by Portugal, Slovenia, Turkey, and Slovakia. On the contrary, the participation of women in the transport sector is decreasing in Romania (approximately –0.83% per year).

Turnbull [18] summarises and explains the low participation of female workers in the transport sector by two factors: (i) working conditions (including the time, timing, and place of work), and (ii) gender stereotyping. In some European countries, for instance, legislation prohibits women from working in specific jobs in the rail industry. These gender-based attitudes are deeply entrenched in many countries and make it difficult for women to progress their careers. In comparison, other transport sectors such as air, maritime, road and postal are viewed as more ‘female-friendly’, according to Fraszczyk and Piip [17].

Mejia-Dorantes [21] analysed the gender gap in the European context regarding transport-related companies. It was concluded that the lack of programs that foster women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) academic disciplines, notably reduce the possibilities to attain higher female shares in the transport sector. The lack of female students in STEM academic disciplines limits the number of future specialists that may later work in a transport company.

The socioeconomic and political situation of each European Union country plays a role in promoting gender equality. As stated by Mejia-Dorantes [21], it is easier for countries with lower unemployment levels to promote more measures to reduce gender gaps. According to the author, transport companies in countries with a worse economic situation may have fewer resources to promote gender equality measures. Therefore, low-cost measures and ideas are important to reduce it.

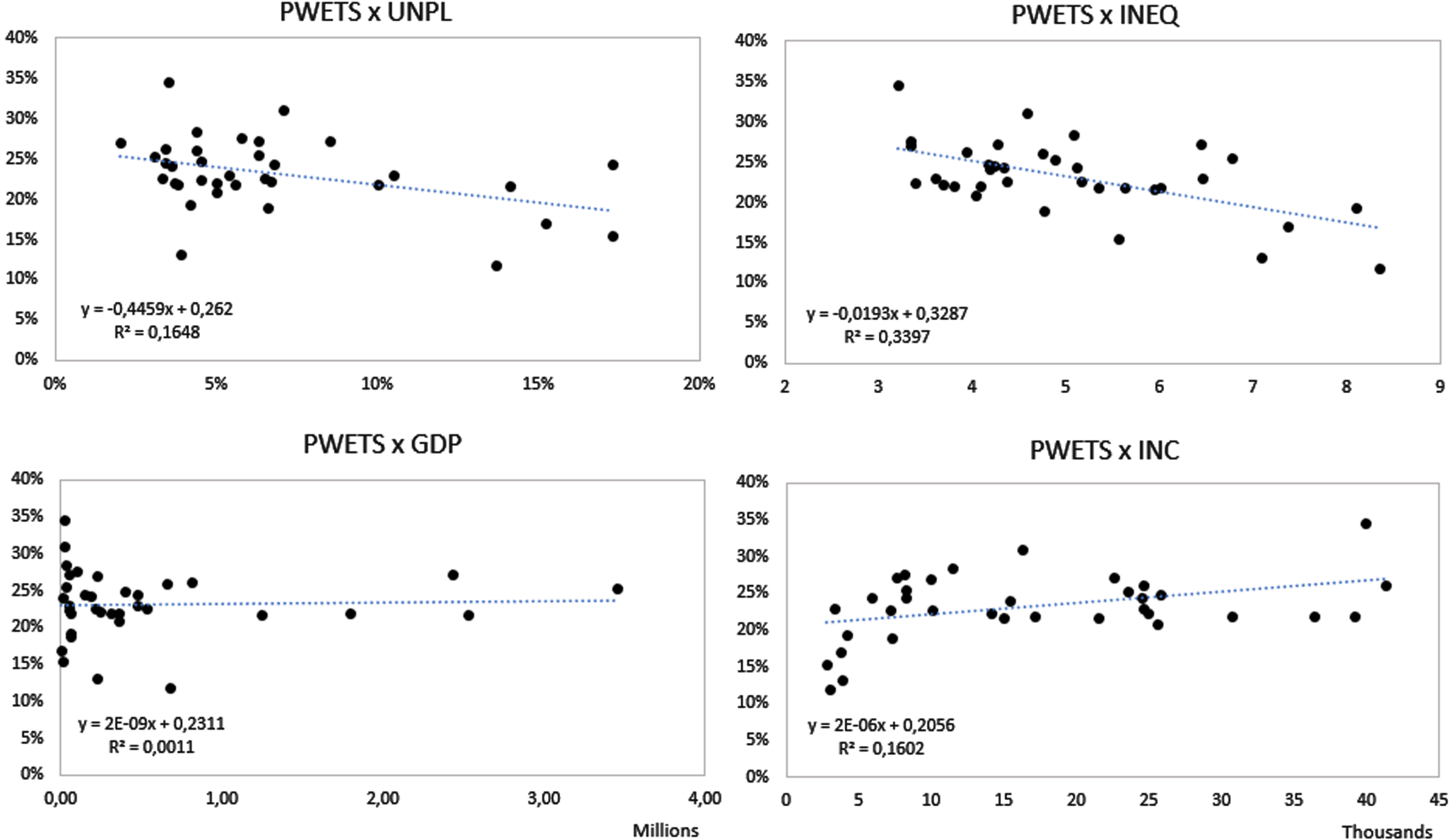

We further investigated the relationship among socioeconomic variables with the employment participation of women in the transport sector (PWETS) in 35 European countries using four independent variables: unemployment rate (UNPL), gross domestic product (GDP), median income (INC), and income quintile share ratio S80/S20 as a variable to measure the inequality (INEQ). Unfortunately, these variables in the multivariate linear regression were not statistically significant (high p-values), except for the income quintile share ratio S80/S20.

Figure 3 presents the simple linear regression among the percentage of women employed in the transport and storage sector (PWETS) and these four variables. As illustrated, European countries with higher income inequalities tend to have less participation of women in the transport sector jobs.

Fig. 3

Linear regressions. Data source: Eurostat, 2019.

3.2A Portuguese perspective

Until the 1950 s women were found in exclusively female traditional occupations [22, 23] characterised by precarious legal status, high rates of illiteracy, poverty, and lack of health services [24]. The existence of gender inequalities has led societies to create different gender social positions. In its turn, the segregation of jobs has created a stereotype that has been easily accepted and replicated in all societies [18, 25].

During its history, transport has been associated with technology and male dominance and control, while women have been relegated to the passive position of passengers [15, 22, 26] or service/administrative roles. Transport has been considered gender-neutral, as it should benefit both men and women. Accordingly, a series of studies have shown that the transport sector, in terms of employment, education, access to facilities and leisure is often gender blind [12, 27, 28].

Amaral et al. [29] highlight that The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) is considered a starting point for the framework of policies for gender equality. Since 1950, the United Nations (UN) started to promote measures sensitive to gender inequalities. Initially, the Portuguese public policies had at their base international guidelines such as the International Decade for Women (1975–1985), the establishment of International Women’s Day and the World Conferences on Women [29, 30]. Within this context, awareness about gender inequalities in Portugal was raised and national plans for gender equality developed.

According to Ferreira [31] and Schouten [24], the current situation of Portuguese women is a direct consequence of a legal framework based on gender equality introduced on the 25th April 1974, reflecting the end of subordination to the traditional male rules. Specifically, the end of the dictatorial regime translated into social processes occurring later than in other European Union countries, including in this category the workforce feminisation and the gender mobility patterns [32].

Nowadays, in Portugal women can be found in almost every activity sector, meaning that societal restricted gender positions in the labour market have dramatically changed [22]. Despite such efforts, gaps remain in some engineering areas, including the transport sector. Researchers affirm that female participation in the national context comes from historical, cultural, and economic peculiarities [24, 33, 34].

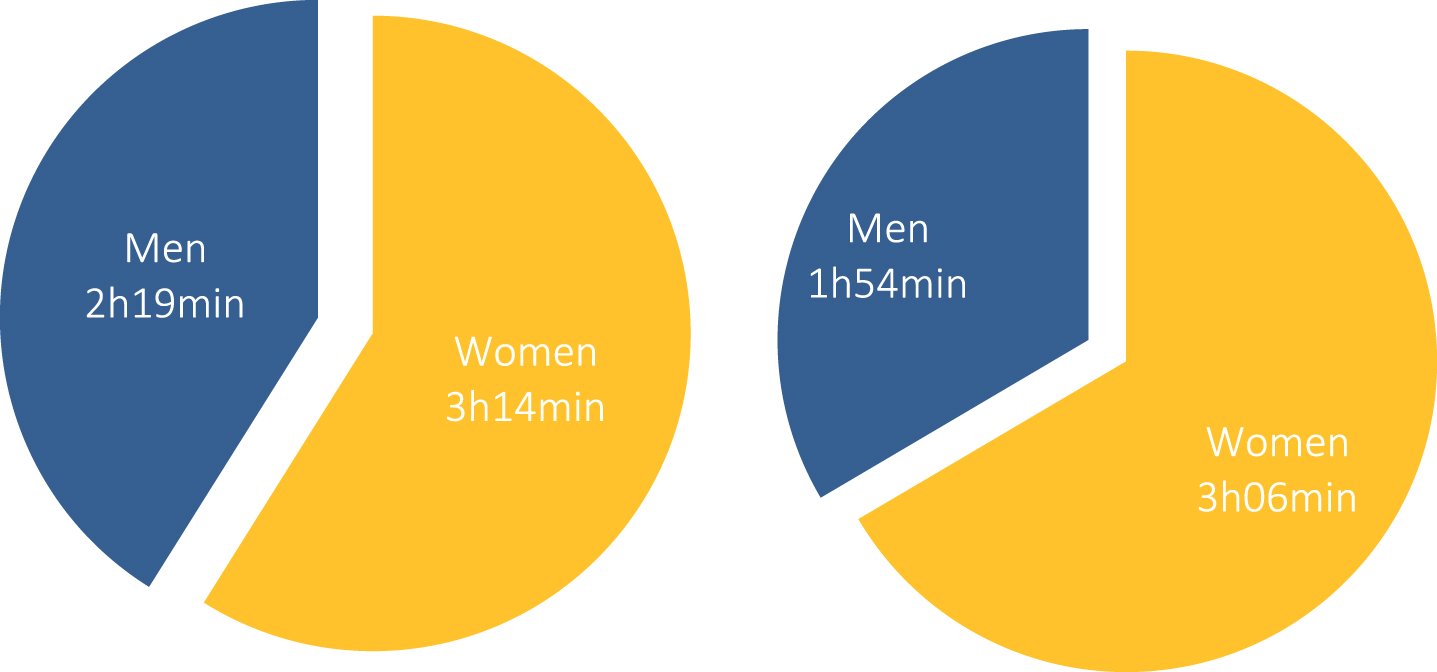

As stated by González [34], the Portuguese labour market is considered a particular case from a gender perspective due to not only the high female participation rate, low gender gaps and employment rates, but the high gender segregation of jobs, both horizontal and vertical. In this sense, female workers are more common in the service sector, while men are more represented in manufacturing and construction [34, 35]. Moreover, women are overrepresented in human health and social support activities, while men are overrepresented in sectors such as extractive industries and transport and storage sectors [35]. As stated by Matias et al. [36] and Oliveira [32], Portugal does not fit into any traditional model. According to these authors, Portuguese women bear mostly all domestic and care chores. Perista et al. [37] researched the distribution of time spent in domestic tasks by men and women in Portugal and identified that men spend on average 2h38 min a day in such activities, while women spend 4h23 min (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Average time of unpaid work on the last working day by gender concerning care work and household chores. Data source: Perista et al., 2016.

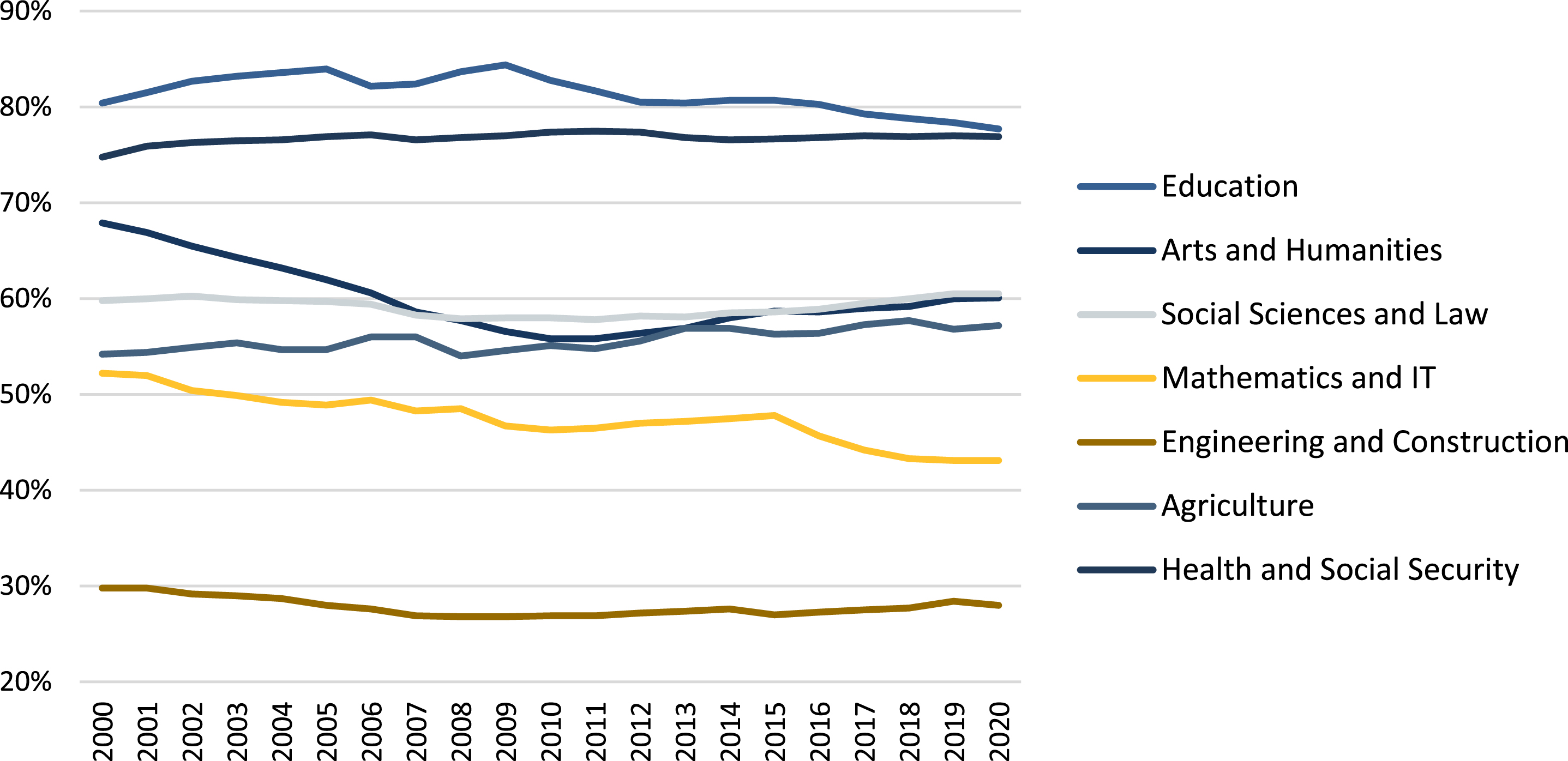

Another important issue remains, at an earlier stage, in education [21, 34, 38]. Although education levels do not differ significantly between genders, the distribution among professions is remarkable. As Fig. 5 illustrates, engineering and construction are the fields where women are less present. The stereotypes rooted in society may explain the gender representation among the different fields of activity.

Fig. 5

Percentage of women in university education per area of knowledge. Data source: PORDATA, 2020.

In a study focused on gender inequalities in the university environment in Lisbon, it has been shown that, although women are found to have higher levels of education, they occupy fewer top places, coping with major difficulties in career progress [38].

Despite legislation that encourages gender equality in decision-making positions adopted at national level across the country, female participation is still marginal, with a predominance of men in the high-level positions in public and private companies. As an example, the company Infraestruturas de Portugal (Infrastructures of Portugal - IP) reported to have 76% of men against 24% of women employed by the end of 2018, with only 36% of women belonging to decision-making positions [39–41].

4Gender equality in the transport sector: An underexplored territory in Portugal?

4.1Existing policies and measures for gender equal opportunities

Gender equality means equal rights and opportunities, visibility, valorisation, power, and participation of both women and men, in all spheres of public and private life. In recent years there has been an increase in European and national policies related to gender equality issues, leading to a clear improvement of women’s inclusion in the labour market in all sectors. These policies emerged mainly due to the adoption of national plans for equality, which are part of the European Strategy for the Employment [42].

The involvement and commitment of several Portuguese public and private companies have contributed significantly to achieve more positive and equitable results in a shorter period. Despite notable improvements in women’s participation in the labour market, asymmetries still exist and must be corrected. In this sense, in the last two decades, Portugal adopted five national plans to promote gender equality (1st Global Plan for Equality of Opportunities 1997–1999, 2nd National Plan for Equality 2003–2006, 3rd National Plan for Equality - Citizenship and Gender 2007–2010, 4th National Plan for Equality, Gender, Citizenship and Non-Discrimination 2011–2013, and 5th National Plan for Equality: Citizenship, Gender and Non-Discrimination 2014–2017) [43].

Additionally, the National Strategy for Equality and Non-Discrimination 2018–2030 - Portugal + Equal has been approved recently. As a direct result, an official institution was created in 1977 - currently CIG – Comissão para a Cidadania e a Igualdade de Género (Committee for Citizenship and Gender Equality). It has made significant positive progress in several fields, such as expansion and democratisation of educational and healthcare structures and social services, leading to the creation of jobs dedicated mainly to women [24, 35, 44].

Intending to promote talented women with leadership potential at top management functions in Portuguese companies, the Confederação Empresarial de Portugal (Confederation of Portuguese Business - CIP) launched in November 2019 the Promova Project. In December 2018, the Portuguese Government launched a work-life balance program “Programa para a Conciliação da Vida Profissional, Pessoal e Familiar 2018-2019” (2018-2019 Professional, Personal and Family Life Reconciliation Program), with a set of best practices to promote well-being in public and private companies [45–47].

Within the National Strategy for Equality and Non-Discrimination 2018–2030 - Portugal + Equal, several significant laws were approved to foster gender equality [47]. In top management positions by introducing the Law 62/2017 August 1st that defines gender quotas in the boards of public and listed corporations, in the last four years the number of female executives has raised significantly in listed firms from 12% to 18%, in state-owned companies from 28% to 32%, and in local public institutions from 20% to 32%.

In the political panorama, changes have also been impressive, with the implementation of the Law 1/2019 March 29th that also defines minimum thresholds for women in electoral lists to national and European parliament, elective bodies of municipalities, and members of the Parish Councils. Lastly, Law 26/2019 March 28th sets a minimum of 40% for women’s representation in the public administration, public higher education institutions and associations [45, 47].

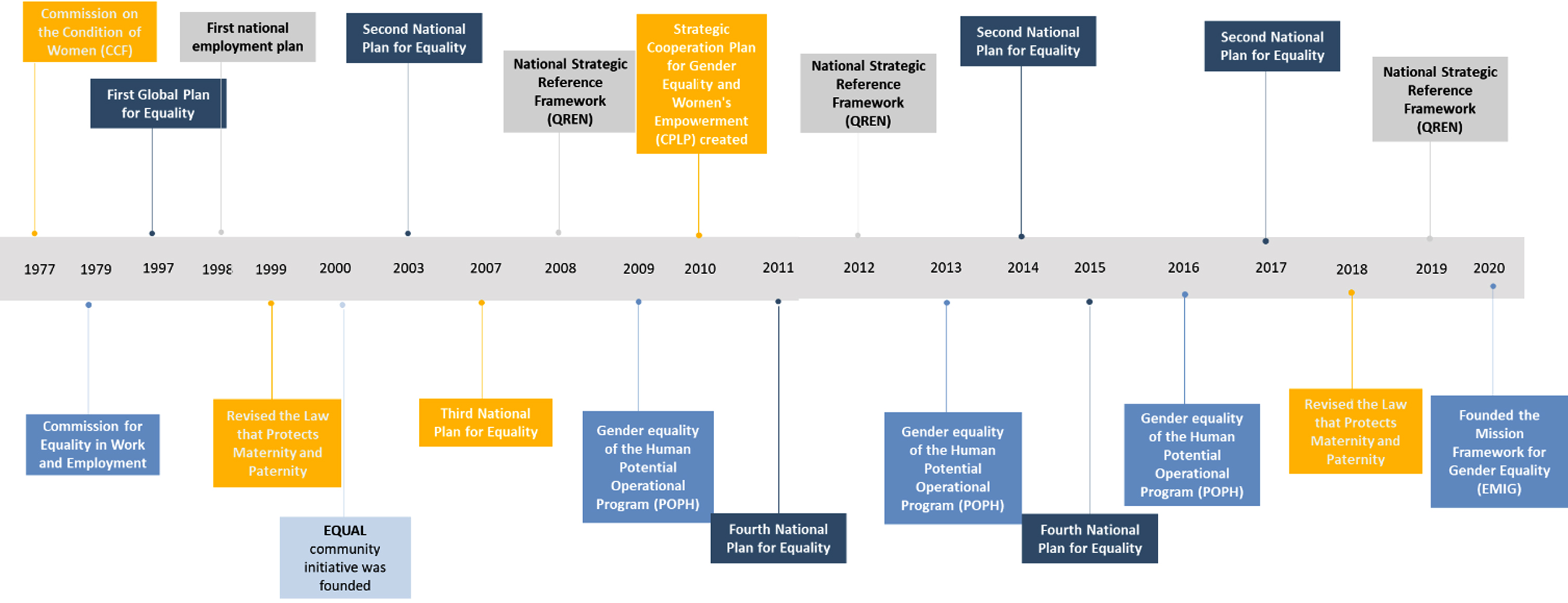

Alongside the above-mentioned main equality plans introduced in Portugal during the last years (see Fig. 6), and in line with the progress seen in the European Union in terms of gender inequalities reduction, there has also been observed a growth in the number of policies related to the gender equality topic that guides the inclusion of women in the labour market and, consequently, a review of the conditions that allow and facilitate the combination of professional activity with family and personal life.

Fig. 6

Chronological line of gender policies and measures implemented in Portugal between 1997 and 2020.

4.2Women in the Portuguese transport sector

In 2018, the active population in Portugal was estimated at 5,232,600, of which 50.8% were men and 49.2% women. Compared to the previous year, there was an increase of 13,200 people, resulting from the increase in the number of active women (+19,200) and the decrease in the number of active men (–6,000) [35].

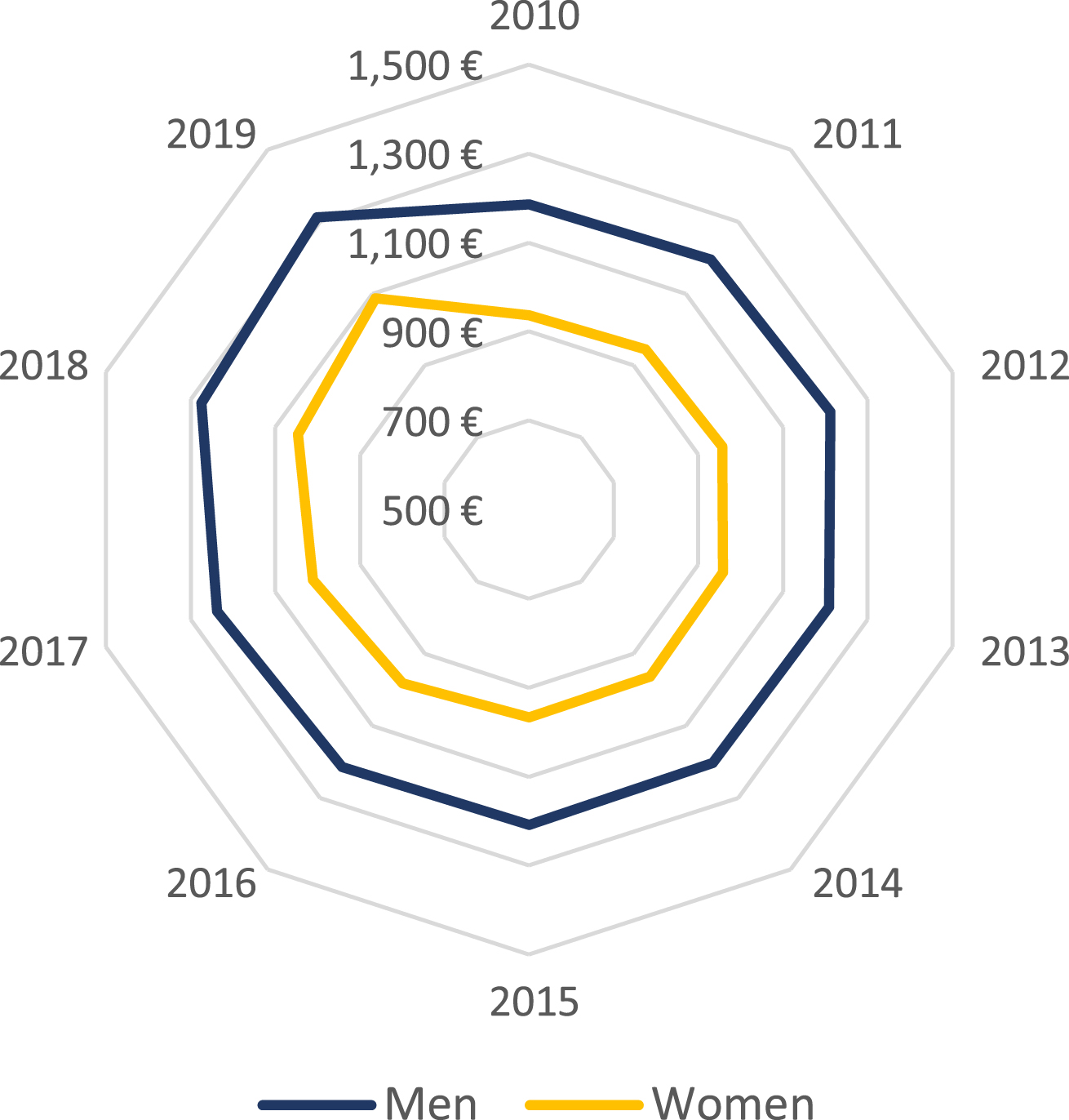

Figure 7 illustrates the wage evolution by gender in Portugal between 2010 and 2019. Although women work more hours per day, men earn more. By 2019, men were earning on average €1,312.4 monthly, while women around €1,087 per month, resulting in a difference of 17.2%. The evolution of monthly income between 2010 and 2019 shows a constant positive trend in the case of women, while men’s income has decreased until 2014, and since that year it has grown steadily. However, the wage gap between men and women, despite its constant decrease between 2010 and 2019, was reduced by only 3.8% during the last decade.

Fig. 7

Gender pay gap in Portugal between 2010 and 2019. Data source: INE and PORDATA, 2020.

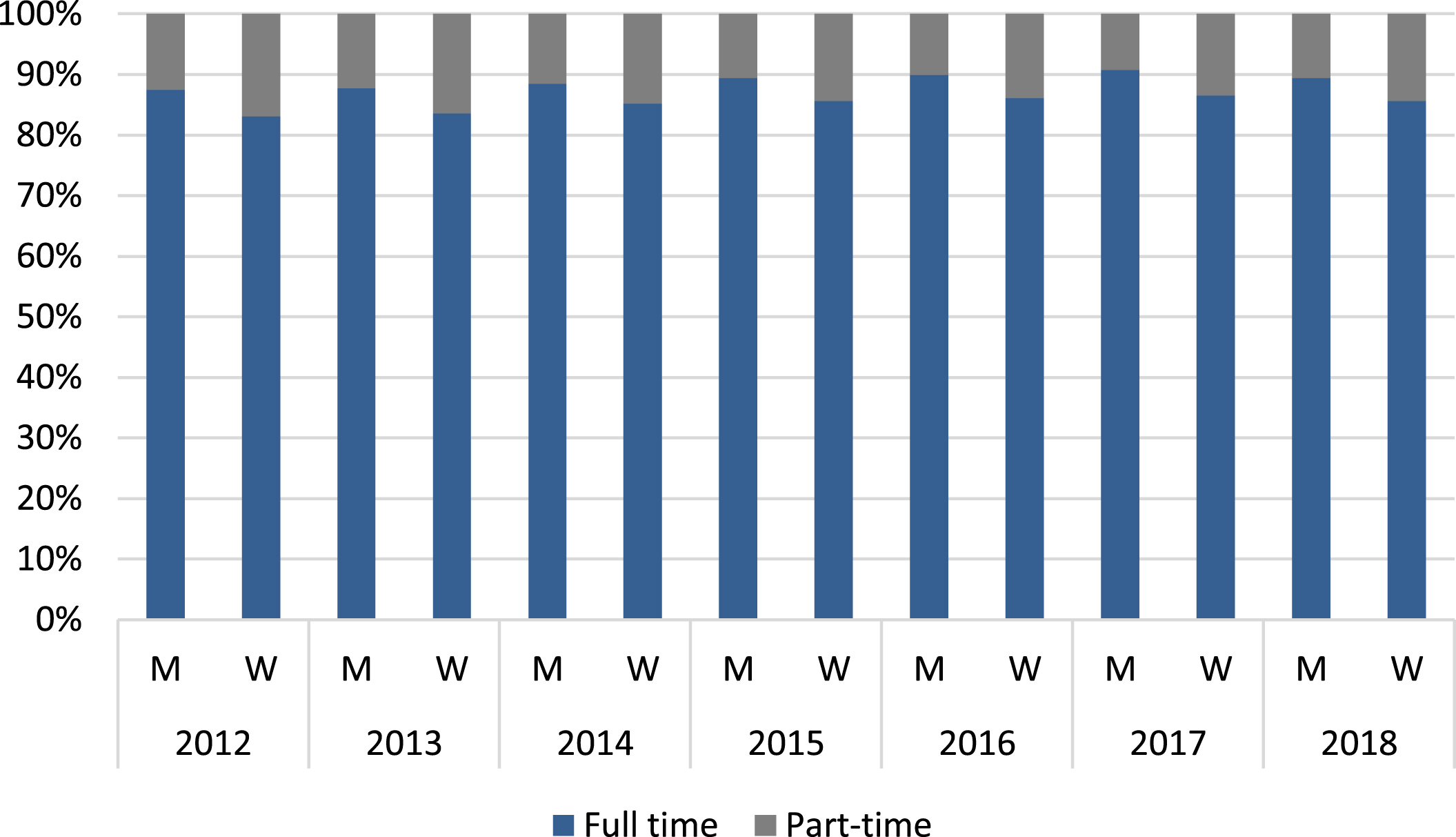

As shown in Fig. 8, Portuguese women are more prone to opt for a part-time job than men. In 2018, 14.4% of women and only 10.6% of men were working part-time, while no stable trend could be observed in the evolution between 2012 and 2018. This is partially explained by the fact that Portuguese men spend 1h36 min a day cooking, cleaning, and taking care of children, which is less than 1/3 of the time used by Portuguese women, who spend on average 5h28 min a day doing domestic tasks [44].

Fig. 8

Employed population by working time arrangements by gender between 2012 and 2018 (%). Data source: CITE, 2019.

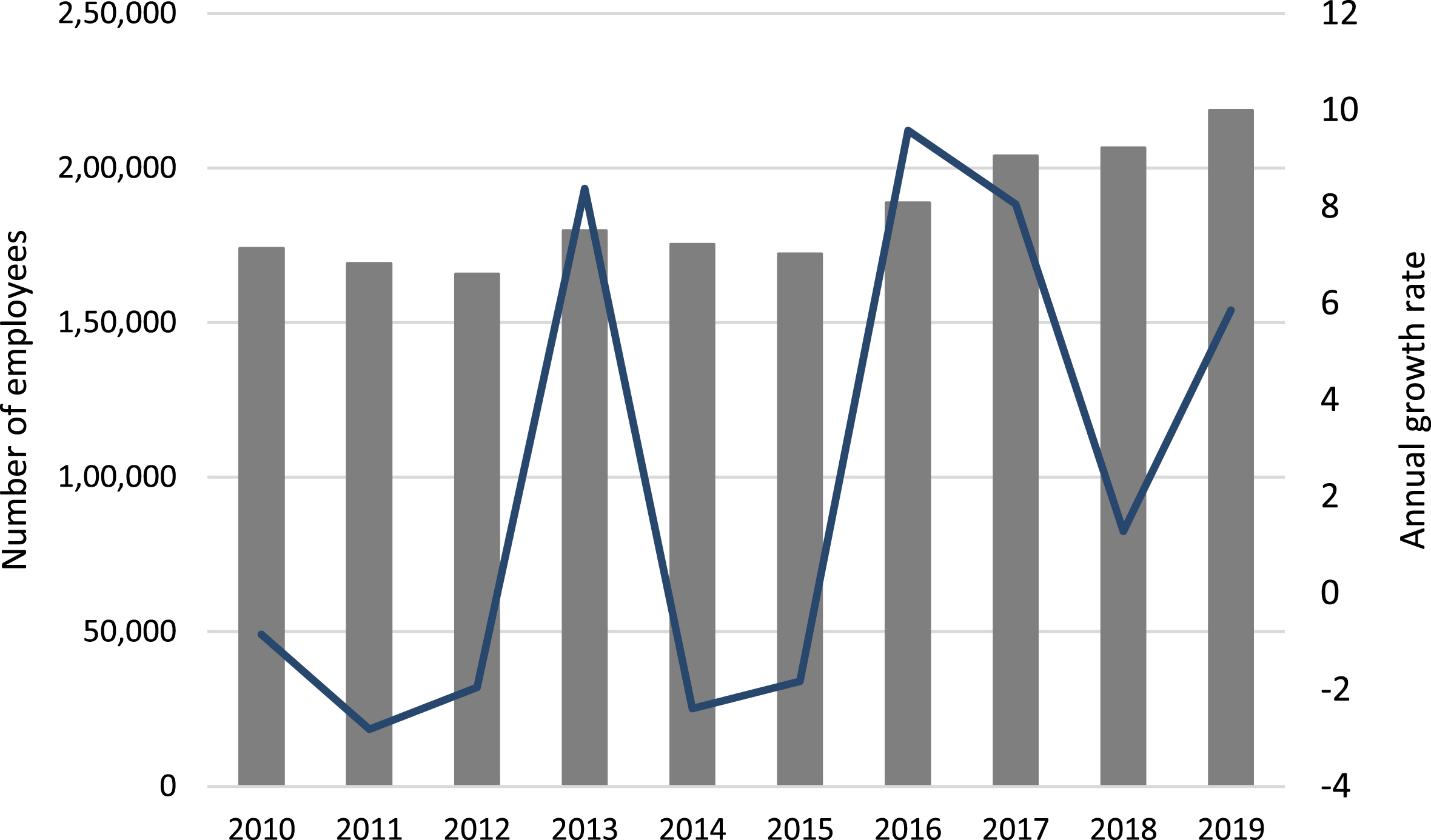

Regarding the Portuguese transport and storage sector, after oscillatory variations, in most cases positive, in 2019 there were 218,600 people working in the sector (see Fig. 9), of which approximately 49,600 were women. On the contrary, according to the 2020 World Report on Gender Inequality, carried out by the World Economic Forum, in Portugal, only 16.2% of women held management positions in companies [50]. Additionally, women continue to use more hours of maternity leaves than men [51].

Fig. 9

Portuguese employees in the transport and storage sector between 2011 and 2020. Data source: PORDATA, 2020.

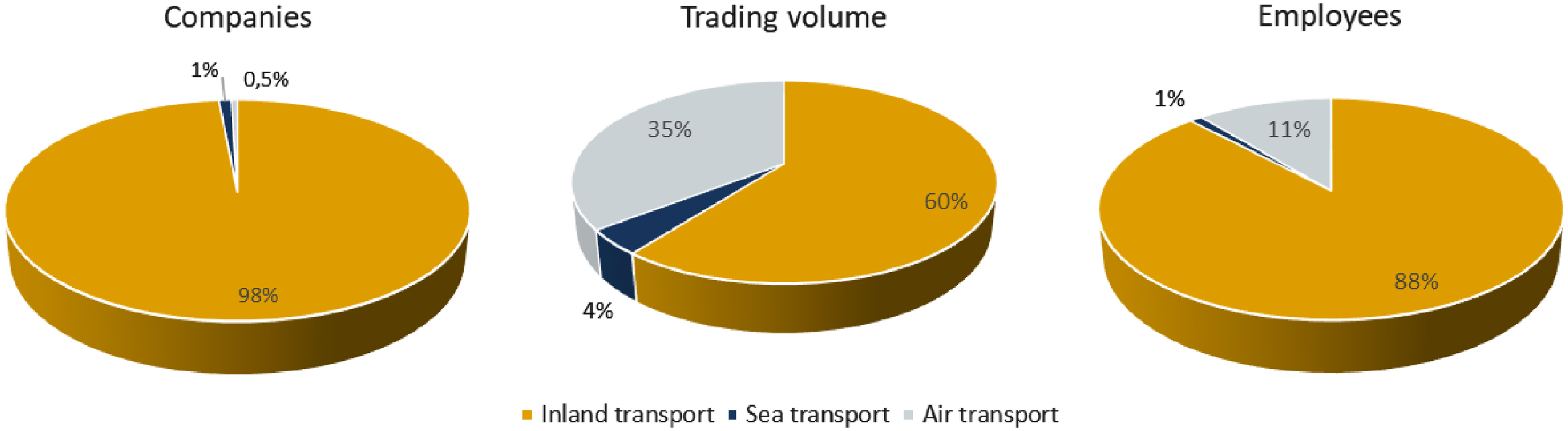

As stated before, the Portuguese transport sector has around 16,000 companies, 91% of them being small companies. The sector is mainly composed by inland transport companies (98%), while air (1%) and maritime (0.5%) subsectors have a very scarce presence. Inland transport companies have a contribution of 60% in the trading volume of the sector and employ around 88% of its total workforce. The air transport subsector has a weight of 35% in the trading volume and 11% in the workforce, while the maritime transport subsector is less represented, with only 4% of the trading volume and 1% of the workforce (see Fig. 10).

Fig. 10

Portuguese transport sector by segments of economic activity – Number of companies, trading volume and number of employees. Data source: Banco de Portugal, 2017.

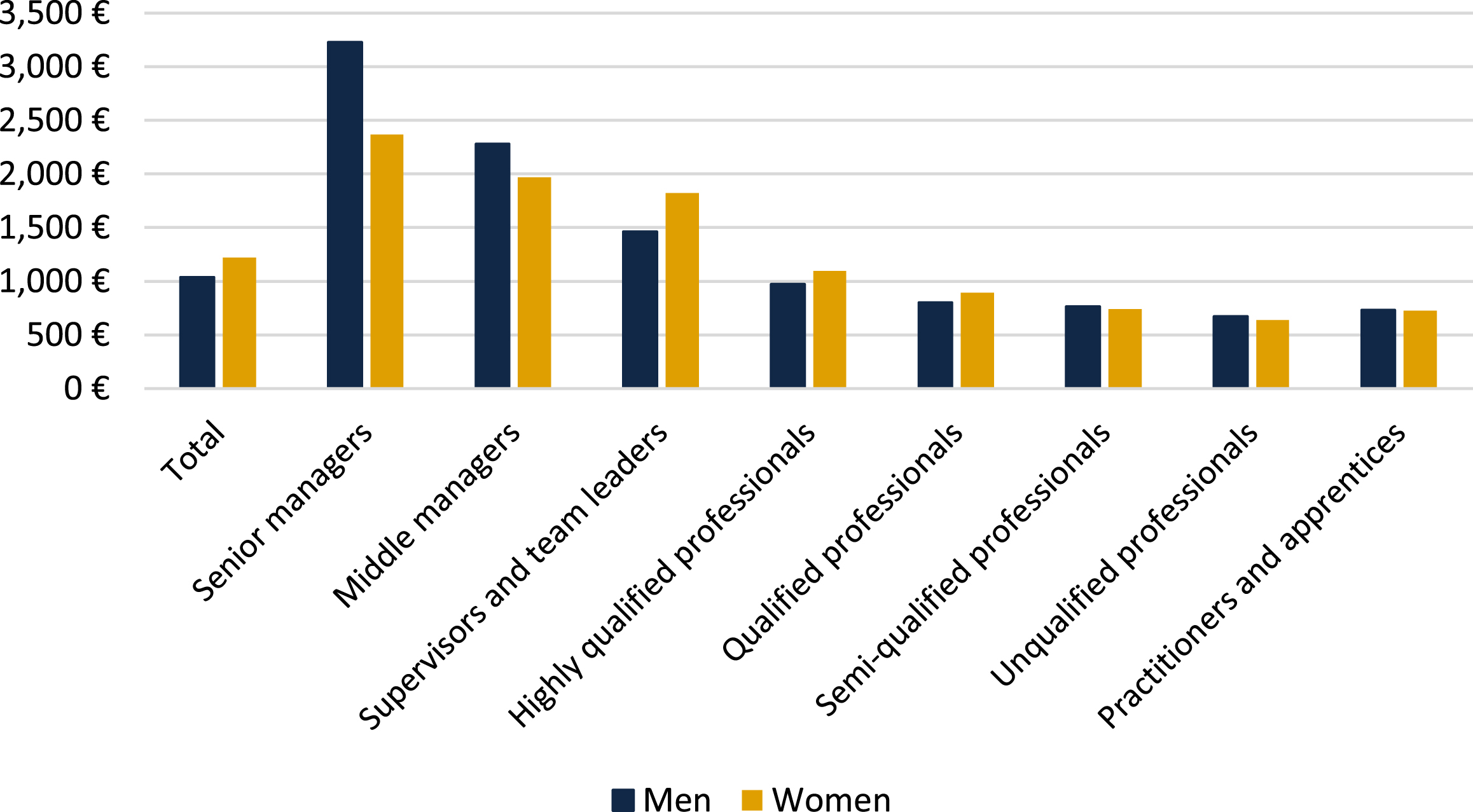

Interestingly, despite the large wage gap between men and women in Portugal and, more specifically, in spite of the unequal distribution among the different professional categories, in the transport sector the distribution of average wages by gender is more balanced. Women’s average monthly income is 17.5% higher than men’s. Nonetheless, the gender pay gap varies among the different professional categories of this sector (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 11

Gender pay gap in the Portuguese transport and storage sector by professional categories in 2019. Data source: PORDATA, 2020.

Hence, women earn less than men in top positions, such as senior managers (–26.7%) and managers (–13.6%). Likewise, men earn less than women in middle positions – supervisors and team leaders (–24.5%), qualified (–11.5%) and highly qualified professionals (–12.5%). On the contrary, in bottom positions (semi-qualified and unqualified professionals, practitioners and apprentices), a balanced distribution can be noticed, with a difference in favour of men of less than 5% in each case.

4.3An insider and close-up approach: How do Portuguese transport companies fight against gender inequalities?

Aiming at providing a general overview of how Portuguese transport companies have been fighting against gender inequalities, this section presents the case studies of two specific large transport companies in Portugal, namely Fertagus and MTS - Metro Transportes do Sul. For this purpose, we used information obtained through semi-structured interviews and statistical data provided by both Fertagus and MTS, as well as the public reports and accounts of these companies, available on their official webpages.

Fertagus is a Portuguese private railway operator. Its railway line serves 14 stations over a length of approximately 54 km spread between the southern and northern banks of Tagus River, connecting the city of Setúbal and Roma-Areeiro station in Lisbon, and is responsible for approximately 98,000 daily commutes [52].

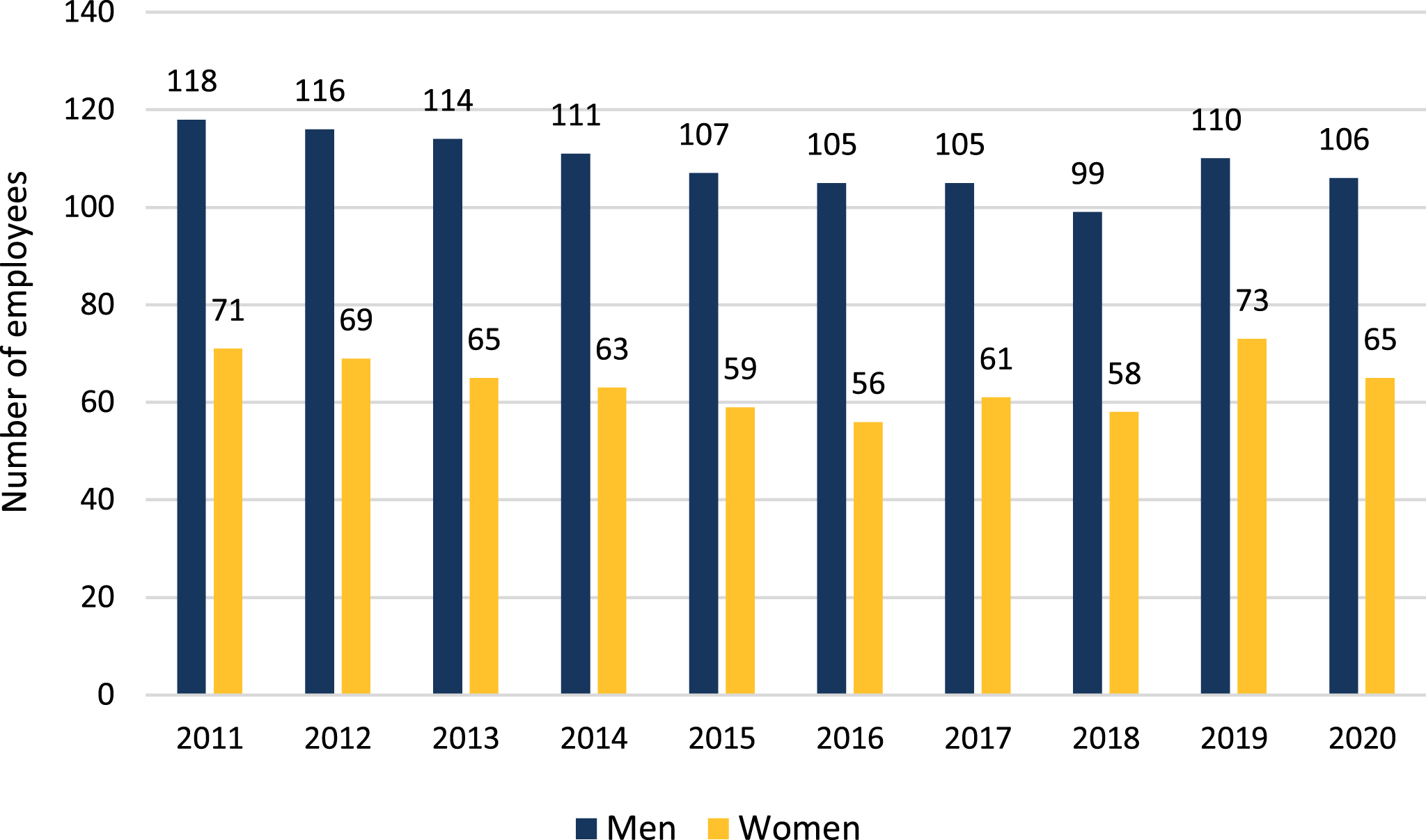

By 2020, the company’s workforce consisted of 183 employees spread across eight functions, with the commercial department having a 50% employee representation. From those 183 employees, 40% were women. The average age of the employees was around 40 years, and 60% of the employees had completed only secondary education [52].

Regarding the evolution in number of employees by gender in the last ten years, as illustrated in Fig. 12, the percentage of men increased between 2011 and 2016 (+4.5%), while the percentage of women decreased during the same period (–7.4%). On the contrary, from 2016 to 2020, the percentage of women increased considerably (+9.3%), whilst the percentage of men decreased by 5%. It is important to mention that the highest proportions of female employees were registered in 2019 (39.9%) and 2020 (38%), which is in accordance with the national gender policy framework timeline (Fig. 6).

Fig. 12

Fertagus employees’ evolution by gender between 2011 and 2020.

According to an internal satisfaction survey answered by 133 employees, it was possible to ascertain that the aspects with the worst scores on a scale varying from 1 to 5 were the equality of opportunity and working conditions with a score of 3.4, and the recognition with a 3.5 score [52]. Hence, the categories where there was a greater gender disparity were the technical professional categories, revealing that investment in the technical training of employees continues to be more applied to men.

MTS - Metro Transportes do Sul, SA is a Portuguese light surface metro operator. Its network is made up of three lines with a total of 14 km and 19 stations, and connects the municipalities of Almada and Seixal on the south bank of the Tagus River [53].

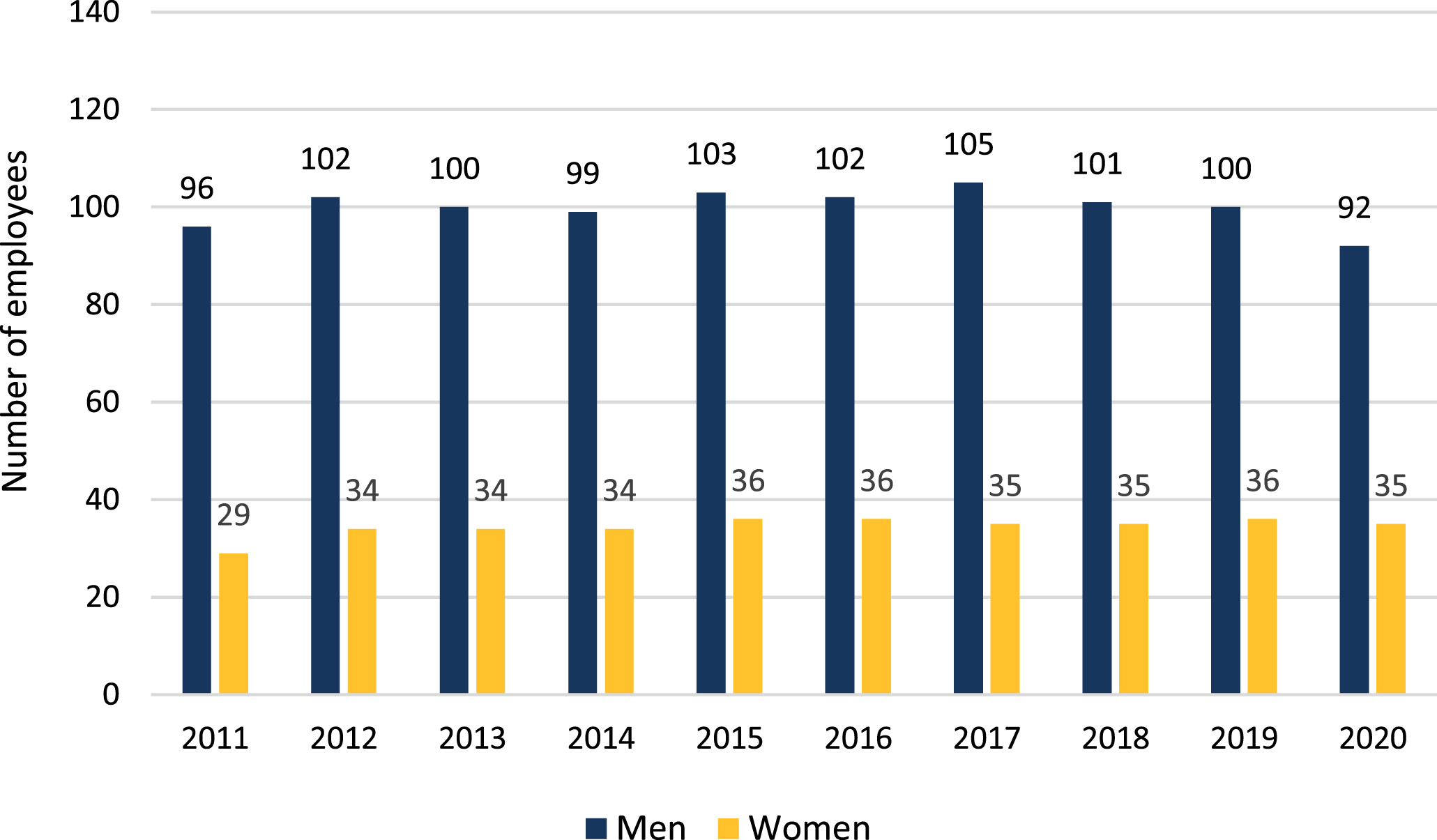

In 2020 the company had 127 employees, of which only 27.6% were women. The trend in employment between 2011 and 2020 shows a substantial increase in the percentage of women, with an overall growth rate around 18.8%, while men decreased by –5.7%. Nonetheless, MTS still presents a very high gender disparity (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13

MTS employees’ evolution by gender between 2011 and 2020.

Regarding the implementation of policies and measures aiming at promoting gender-equal opportunities, Fertagus and MTS affirmed the companies do not have, nor have implemented specific measures. They consider it unnecessary and claim they never discriminated a worker by gender.

“We do not have specific measures in place, as we believe it is not necessary. At Fertagus, we do not and never have made any discrimination regarding gender. When a recruitment process takes place, we only evaluate the candidates’ skills, and not whether they are men or women.”

Accordingly, both Fertagus and MTS state they have a balanced ratio of employees by gender in top positions.

“Fertagus was the first Portuguese railway company to hire female train drivers. Currently, the company has four intermediate managers in the Commercial Department, of which three are women. At the same time, the company has five directors, three of whom are women. Since 2019, the Board of Directors has three members, all women, while two women were hired for maintenance operators in the same period.”

“At MTS, since the 1st recruitment we have hired women for driver operators, a situation that has remained until today in the company. In our Commercial Department, we have one woman as intermediate manager from a total of two. Moreover, the company has two female employees as heads of two departments, from a total number of four such departments.”

Concerning absenteeism by gender and professional category, both companies affirmed they do not make public such data, while neither Fertagus, nor MTS assessed the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the employees’ professional activity performance, stating they did not see any added difficulties in female employees due to COVID-19 outbreak.

From these two case studies it is possible to affirm that women are starting to be important in transport companies, but are not yet recognized in the same way as men. In these two specific cases, no plans for equality and combating harassment at work were found. Although the companies do not discriminate based on gender, they do not make any positive differentiation to attract more women in the sector.

5Barriers and recommendations towards an ungendered transport sector in Portugal

5.1Barriers to women’s career progression

Potential employees reject jobs that have an unappealing image or less attractive characteristics [17] such as high accident rate at work, non-valuation, lack of career advancement opportunities, lack of inspection of safety at work by public entities [54], “dirty”, “difficult” and “dangerous” work, and unstable wages [55]. According to Hjelte et al. [25], women are looking for quality jobs that value aspects such as flexible hours, proximity to the workplace, learning opportunities, growth in the company, autonomy, and social interaction.

García-Jiménez et al. [56] identified four main groups of barriers that negatively influence women’s empowerment: (i) socioeconomic conditions, (ii) job characteristics, (iii) personal circumstances, and (iv) individual characteristics.

The socioeconomic conditions refer to segregation of jobs and unequal recruitment and legal framework factors. The second category of barriers that make women’s empowerment and career progression difficult is related to the characteristics of jobs, such as gender inequalities in recruitment, retention, and promotion processes, pay gaps and facilities, training provision, safety, and security.

The third category includes personal circumstances, such as caring/parenting responsibilities, social network and access to resources and information. Last but not least, the fourth category is defined by women’s individual characteristics, such as personal skills, adaptability, education level, health status, wellbeing, or demographic factors that most often interfere with women’s career progression.

In Portugal, the transformation of labour market has been accompanied by several national directives and movements, generally driven by European directives [35, 51, 57]. Although women have a consolidated presence in the labour market and in education, they are still underrepresented in high-level positions in companies because of the differences found in career progression opportunities [29, 32]. Hence, it is important to look more closely at the transport sector to understand the persistent imbalance in gender participation.

The approach of gender equality in the transport sector is a very recent phenomenon in Portugal [23, 28]. As stated by Cunha et al. [49], due to their latest entry in the sector, Portuguese women working in the transport sector are normally in the most unfavourable status and are obliged to do painful services [49]. Accordingly, the main barrier to women’s progression is a combination between the atypical working times, the professional status, low career development opportunities, the incompatibility of the working schedules with personal and family life [18, 49], and the impact of work on health, as several transport professional categories require physical and mental effort [25]. On the contrary, according to Monteiro et al. [48] the absence of a gender perspective in the diagnosis, planning, design and evaluation of mobility and transport systems is the first step to women’s career failure in the transport sector.

The discussion about employment in the transport sector should be made along with the discussion on how the Portuguese society works and what role men and women play in family care and domestic chores [35]. The remarkable difference in the distribution of family responsibilities and house care still present in Portuguese society may be the cause of the weak presence of women in a still male-dominated sector [37]. The existing discrimination at work results in limiting women’s pay, imposes barriers to career development and limits the potential in the workplace as a result of reduced motivation levels [44, 58].

The evolution of Portuguese society towards a more equitable sharing of family duties has not been accompanied either by an evolution in terms of legal framework, infrastructure, and mentality [24], or in terms of companies’ openness to gender issues [51]. Against this background, the analysis of the case studies also resulted in three barriers that most often hinder the women’s career progression.

The first barrier identified is the lack of gender equality plans in companies belonging to the national transport sector. Although there exist clear directives and guidelines that point to the need for companies to implement gender equality plans, this is not yet applied in all transport companies.

Additionally, the lack of measures aiming at mitigating gender inequalities in companies within this sector leads to an increase in the segregation of professional categories. On the other hand, the lack of satisfaction surveys within companies on a regular basis represents another barrier to women’s career development, as in the absence of such measures women’s perceptions and needs cannot be properly heard, thus affecting their professional path.

Based on the analyses presented above, the barriers to women’s career progression in the Portuguese transport sector can be grouped into three main categories: (i) societal barriers, (ii) company barriers and (iii) personal barriers.

The first category of barriers refers to cultural and societal norms and messages, most often unspoken, that women receive during their lifetime. These are frequently induced by gender stereotypes and societal traditions, which reinforce the way in which men and women are seen in the society [51]. The main factors that cause this type of barriers are the gender roles unconsciously assigned and assumed by women and men at a young age [48], including the segregation of academic fields in schools [21, 38], domestic responsibilities inherited from parents and grandparents, or even the lack of flexible working or the excessive childcare costs [44].

The second category of barriers relates to obstacles experienced in the workplace. This category includes elusive critical experiences that influence the women within the company, such as organisational cultures and norms which disadvantage women, unequal mentoring and sponsorship, lack of role models [43, 49], and absence of gender equality plans and measures [51].

The third category of barriers refer to the specific presence of women in the workplace, which is directly related to women’s attitudes. Besides specific negative situations women may experience in the workplace [29], it is worth mentioning the scepticism, the ambition gap, the confidence, not pushing to be heard during meetings, trying to replicate ‘male’ models, or reticence to instigate negotiations [44].

5.2Recommendations towards an ungendered transport sector in Portugal

Although there are already clear laws in the labour code on equality and non-discrimination principles, as well as entities that supervise these situations in companies, very little is applied. Additionally, the results of the measures and campaigns developed so far are rather unsatisfactory, meaning that there is still a long journey ahead to overcome this gap. Thus, it is still necessary to implement measures, not only across public and private companies, but also at governmental level and in the educational system (see Table 1).

Table 1

Recommendations to mitigate gender inequalities in the Portuguese transport sector

| Educational and scientific level | •Introduction of an optional transport and mobility discipline in the lower and upper secondary education curricula. |

| •Organization of annual study visits to transport companies, with the presentation of the work carried out. | |

| •Universities specialized in transport and mobility area should encourage researchers to conduct studies on gender inequalities in the transport sector. | |

| •National and European organizations of mobility programs and projects should support and encourage research on gender inequalities within the transport sector. | |

| Company level | •Adoption of a transparent remuneration policy. |

| •Implementation of regular internal surveys in order to assess employees’ biggest difficulties at work. | |

| •Annual reports containing nominative information, divided between genders. | |

| •Creation of involvement programs on returning to work after parental leave. | |

| •Creation of child day care centres and holiday camps to be used during Easter, Summer, and Christmas. | |

| •Creation of women’s development programs in transport companies. | |

| Governmental level | •The development of all transport systems must have at its base the life experiences of women and the specific needs at each stage of their life cycle. |

| •Local authorities should include specialists in gender within the transport planning sector. | |

| •Implementation of a law that allows women with children under 6 years old to work 6 hours a day or to have flexible work schedule. | |

| •Monitoring of equality plans elaboration and implementation within the companies and employees’ satisfaction surveys. | |

| •Annual national reports featuring successful women working in the Portuguese transport sector. |

At educational and scientific level, the Ministry of Education should propose the introduction of an optional transport and mobility discipline in lower and upper secondary education curricula. Thus, future students would have a better vision on what the transport sector involves, as well as what are the perspectives this sector may offer. Likewise, considering the differences that normally exist between theory and practice, annual study visits to transport companies should be organised, with the presentation of the work carried out. These two measures should be corroborated with inclusion programs that involve allocation of school hours dedicated to the theme of professional categories and career.

Moreover, the universities specialised not only in transport and mobility, but also in employment, should encourage researchers to conduct studies on gender inequalities in the transport sector, offering participants funds or prizes as an incentive, while the national and European organizations of mobility programs and projects should support and encourage research on gender inequalities within the transport sector as well.

At company level, companies should ensure the existence of a transparent remuneration policy applicable to their workers in order to avoid gender wage discrimination. This policy should be based on the evaluation of the components of the functions performed by the workers, merit, productivity, assiduousness, or absenteeism rate.

The elaboration of public annual reports by companies containing nominative information by gender would increase the companies’ level of transparency about its composition, professional categories, and differences in salaries, not only between men and women, but also among the different professional positions.

Furthermore, the implementation of regular internal surveys to employees in order to assess their difficulties at work would help to reduce the gender disparity within the sector. Based on surveys results, the measure should be complemented by training actions to fight against the gaps within a maximum period of six months after closing the survey.

Transitioning back to work after parental leave is always challenging [59]. Thus, the creation of involvement programs on returning to work after parental leave, based on career development or maternity-return coaching for example, may support women returning to work, give confidence, and help organise better their career progress. In addition, in order to care for the children of workers who cannot take holidays during Easter, Summer and Christmas, child day care centres and holiday camps should be created. This measure may involve not only the transport companies, but also local authorities, and other activity sectors.

On the other side, by creating development programs for women, such as leadership development programs, coaching, mentoring or acceleration programs, would help them to develop their own professional skills and identity. Indirectly, it would help companies to improve their human resources, productivity, and overall results.

Regarding the governmental level, as stipulated by existing legislation, the elaboration of gender equality plans is mandatory. In order to avoid non-compliance with legislation, the Government should monitor the elaboration and implementation of gender equality plans within companies. In addition, companies should be obliged to conduct an internal survey among employees to ascertain whether or not the framework of measures to implement in the respective year has been complied with.

In order to allow a better conciliation between professional and personal life, the Government should implement a law that allows women with children under 6 years old to work 6 hours a day and give them priority to choose their working hours in case shift work is permitted. Otherwise, the Government should encourage transport companies to offer flexible work schedules for women in thatsituation.

With the aim of inspiring female students and/or early career women, annual national reports featuring successful women working in the Portuguese transport sector should be elaborated, with the results to be disseminated in newspapers, on television and on the Internet.

6Conclusions

Following a global tendency adopted by almost each European Union country, in Portugal women still occupy a majority place in services, which somehow reflect the work done in the family environment over time. Despite all the profound changes as a result of a common effort of Government, public and private institutions, academia, and the society itself, equality between men and women presents paradoxes in each activity sector, including transport sector, where women are still underrepresented.

The lack of women’s facilities, the need for improved measures and strategies, and the need for better human resources policies which acknowledge women’s caring responsibilities are the main factors that should be improved in order to increase the participation of women in transport jobs, their empowerment and career progression. Nevertheless, although policies have been evolving regarding this topic, the lack of specific measures applied to each sector of work and regular checks to ensure their application proves that there is still a long way to go before this gap is closed.

Segregation between women and men within the transport sector starts early, as a result of traditions and stereotypes about gender positions that influence women’s and men’s career paths, with gender segregation crossing not only the labour market, but also the educational system. Therefore, it is important to continue the implementation of measures and laws to overcome socio-cultural stereotypes and build a new narrative. The dissemination of good practice examples and the further development of targeted laws are essential to reform the overview of the industry and its participants and should be conducted in such a way to include all stakeholders, especially companies.

6.1Limitations of the study

The main limitation of the study was the absence of academic studies that address the position of Portuguese women in the transport sector and the barriers they have to break for the sake of career advancement. Additionally, considering that gender equality is still a sensitive issue within the labour market, Portuguese transport companies still have misgivings when approached by researchers or specialists in the field. It was demonstrated by our several failed attempts to include more transport companies in this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their gratitude to VTM – Consultores em Engenharia e Planeamento, Lda. and TInnGO— Transport Innovation Gender Observatory project for supporting this work, and to Fertagus and MTS – Metro Transportes do Sul for collaborating with us and providing the case study data.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

References

[1] | Pinillos-Franco S , García-Prieto C . The Gender Gap in Self-rated Health and Education in Spain. A Multilevel Analysis. PLoS ONE. (2017) ;12: (12):1–12. |

[2] | Quinn MM , Smith PM . Gender, Work, and Health. Annals of Work Exposures and Health. (2018) ;62: (4):389–92. |

[3] | Kwon MJ . Occupational Health Inequalities by Issues on Gender and Social Class in Labour Market: Absenteeism and Presenteeism Across 26 OECD Countries. Frontiers in Public Health. (2020) ;8: , 84. |

[4] | Kippe K , Lagestad P . Physical Activity Level of Kindergarten Staff Working with Toddlers and Older Children in Norway. Work. (2020) ;66: :221–8. |

[5] | Ilovan OR , Muntean AD . Capitolul 1. Introducere. Geografia Dezvoltării: o Abordare Centrată pe Om (Chapter 1. Introduction. Geography of Development: a Human-centered Approach). In: Ilovan OR, Muntean AD. Geografia Dezvoltării. Abordări Centrate pe Om ın Contextul Românesc (Geography of Development. Human-centered Approaches in the Romanian Context). Cluj-Napoca, Romania: Presa Universitară Clujeană. (2021) ;9–14. |

[6] | Hedija M . Sector-specific Gender Pay Gap: Evidence from the European Union Countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja. (2017) ;30: (1):1804–19. |

[7] | Magda I , Sałach K . Gender Pay Gaps in Domestic and Foreign-owned Firms. Empir Econ [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Ago 25]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01950-z. |

[8] | Fuchs M , Rossen A , Weyh A , Wydra-Somaggio G . Where Do Women Earn More than Men? Explaining Regional Differences in the Gender Pay Gap. J Regional Sci. (2021) ;1–22. |

[9] | Hanson S . Gender and Mobility: New Approaches for Informing Sustainability. Gender, Place & Culture. (2010) ;17: (1):5–23. |

[10] | Lee RJ , Sener IN . Transportation Planning and Quality of Life: Where Do They Intersect? Transport Policy. (2016) ;48: :146–55. |

[11] | Singh YJ . Is Smart Mobility Also Gender-Smart? Journal of Gender Studies. (2019) ;29: (7):832–46. |

[12] | Harumain YAS , Nordin NA , Ching GH , Zaid NS , Woodcock A , Mcdonagh D , et al. The Urban Women Travelling Issue in the Twenty-first Century. Journal of Regional and City Planning. (2021) ;32: (1):1–14. |

[13] | Banco de Portugal [Internet]. Lisbon: Banco de Portugal; 2019 Jun 28. Nota de Informação Estatística - Análise das Empresas do Setor dos Transportes 2017 (Statistical Information Note - Analysis of Transport Sector Companies 2017); [cited 2021 Jan 26]. Available from: https://www.bPortugal.pt/comunicado/nota-de-informacao-estatistica-analise-das-empresas-do-setor-dos-transportes-2017. |

[14] | European Commission. Transport Sector Economic Analysis [Internet]. Brussels: European Commission; 2019 [updated 2021 Jun 23; cited Ago 25]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/research-topic/transport-sector-economic-analysis. |

[15] | National Statistics Institute of Portugal. Inquérito à Mobilidade nas Áreas Metropolitanas do Porto e de Lisboa (Survey on Mobility in the Metropolitan Areas of Porto and Lisbon). Lisbon: National Statistics Institute of Portugal; 2017. 205 p. Available from: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=349495406&PUBLICACOESmodo=2. |

[16] | PORDATA - Contemporary Portugal Database [Internet]. Lisbon: PORDATA - Contemporary Portugal Database; 2020. Salário Médio Mensal dos Trabalhadores por Conta de Outrem: Remuneração Base e Ganho por Sexo (Average Monthly Salary of Employees: Base Pay and Earnings by Gender); 2021 May 05 [2021 Ago 28]. Available from: https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Sal%C3%A1rio+m%C3%A9dio+mensal+dos+trabalhadores+por+conta+de+outrem+remunera%C3%A7%C3%A3o+base+e+ganho+por+sexo-894. |

[17] | Fraszczyk A , Piip J . A Review of Transport Organisations for Female Professionals and their Impacts on the Transport Sector Workforce. Research in Transport Business and Management. (2019) ;31: (100379). |

[18] | Turnbull P . Promoting the Employment of Women in the Transport Sector - Obstacles and Policy Options. Geneva: International Labour Office - Sectoral Activities Department; (2013) . 57 pp. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—sector/documents/publication/wcms_234880.pdf. |

[19] | Eurostat [homepage on the Internet]. Eurostat Labour Force Survey: Percentage of Women Employed in the Transport and Storage Sector (NACE H) Compared to the Total Employment in Transport [updated 2019, cited 2021 Jan 22]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/transport/facts-fundings/scoreboard/compare/people/women-public-transport_en. |

[20] | European Institute for Gender Equality [homepage on the Internet]. Gender Statistics Database [updated 2019 cited 2021 Jan 20] Available from: https://eige.europa.eu/. |

[21] | Mejia-Dorantes L . Discussing Measures to Reduce the Gender Gap in Transport Companies: A Qualitative Approach. Research in Transport Business and Management. (2019) ;31: (100416). |

[22] | Queirós M , da Costa NM . Knowledge on Gender Dimensions of Transport in Portugal. Dialogue and Universalism E. (2012) ;3: (1):47–69. |

[23] | Queirós M , da Costa NM , Morgado P , Vale M , Mileu N , André I , et al. GenMob - Género e Mobilidade. Desigualdade no Espaço-tempo. Informação para as Políticas (Gender and Mobility. Inequality in Space-time. Policy Brief).Lisbon, Portugal: Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território; (2017) . 66 pp. Available from: http://genmob.ceg.ulisboa.pt/publications/. |

[24] | Schouten MJ . Undoing Gender Inequalities: Insights from the Portuguese Perspective. Insights into Regional Development. (2019) ;1: (2):85–98. |

[25] | Hjelte J , Stenling A , Westerberg K . Youth Jobs: Young Peoples’ Experiences of Changes in Motivation Regarding Engagement in Occupations in the Swedish Public Sector. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. (2018) ;23: (1):36–51. |

[26] | Beirão G , Cabral JAS . Understanding Attitudes Towards Public Transport and Private Car: A Qualitative Study. Transport Policy. (2007) ; 14: , 478–89. |

[27] | Allen H . Approaches for Gender Responsive Urban Mobility - Module 7a: Sustainable Transport: A Sourcebook for Policymakers in Developing Cities. Eschborn; Germany Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development; (2018) ; 50 pp. |

[28] | Queirós M , da Costa NM . Planning Mobility in Portugal with a Gender Perspective. In: de MadariagaIS, NeumanM (Eds.). Engendering Cities: Designing Sustainable Urban Spaces for All. London: Routledge. (2020) ;71–89. |

[29] | Amaral I , Daniel F , Abreu SG . Policies for Gender Equality in Portugal: Contributions to a Framework for Older Women. Revista Prisma Social - La investigación en la Comunicación Organizacional a Debate. (2018) ;22: :346–63. |

[30] | Subtil F , Silveirinha MJ . Planos de Igualdade de Género nos Media: para uma (Re) Consideração do Caso Português (Gender Equality Plans in the Media: for a (Re)Consideration of the Portuguese Case). Media & Jornalismo. (2017) ;17: (30):43–61. |

[31] | Ferreira A . A Mulher no Setor dos Serviços: Percurso Histórico e Desigualdades (Women in the Services Sector: Historical Background and Inequalities). Campus Social – Revista Lusófona de Ciências Sociais. (2007) ;3: (4):259–68. |

[32] | Oliveira CS . Still Driven - Mobility Patterns and Gender Roles in Portugal. CIES e-Working Papers [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2021 Jan 15]; 185(ISSN -1647-0893). Available from: https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/handle/10071/9891. |

[33] | González P , Santos MC , Santos LD . The Gender Wage Gap in Portugal: Recent Evolution and Decomposition. CETE Discussion Paper. (2005) ;1–23. |

[34] | González P . Gender Issues of the Recent Crisis in Portugal. Revue de l’OFCE / Debates and policies. (2014) ;2: (133):241–75. |

[35] | Committee for Equality in Work and Employment (CITE) - Presidency of the Ministers’ Council. A Igualdade entre Mulheres e Homens no Mercado de Trabalho (Equality between Women and Men in the Labour Market). Lisbon, Portugal: Committee for Citizenship and Gender Equality (CITE); 2019. Available from: https://cite.gov.pt/documents/14333/193229/Relatorio+2018+Lei+10.pdf/6fca7155-97d0-48c6-9b7d-2d7b1a7d94b3. |

[36] | Matias M , Andrade C , Fontaine AM . The Interplay of Gender, Work and Family in Portuguese Families. Work Organisation, Labour & Globalisation. (2012) ; 6: (1):11–26. |

[37] | Perista H , Cardoso A , Brázia A , Abrantes M , Perista P . Os Usos do Tempo de Homens e de Mulheres em Portugal (The Use of Time by Men and Women in Portugal). Lisbon, Portugal: CESIS – Centro de Estudos para a Intervenção Social; (2016) . 186 pp. |

[38] | Cabrera A . Desigualdades de Género em Ambiente Universitário: Um Estudo de Caso sobre a Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade NOVA de Lisboa (Gender Inequalities in the University Environment: A Case Study of the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences at Universidade NOVA de Lisboa). Faces de Eva, Estudos sobre a Mulher. (2019) ;47–66. |

[39] | Infraestruturas de Portugal. Plan for Gender Equality 2018. Lisbon, Portugal: Infraestruturas de Portugal; 2017. 16 pp. Available from: https://www.infraestruturasdePortugal.pt/pt-pt/sobre-nos/governo-societario/plano-para-igualdade. |

[40] | Infraestruturas de Portugal. Plan for Gender Equality 2020. Lisbon, Portugal: Infraestruturas de Portugal; 2019. 28 pp. Available from: https://www.infraestruturasdePortugal.pt/pt-pt/sobre-nos/governo-societario/plano-para-igualdade. |

[41] | Infraestruturas de Portugal. Plan for Gender Equality 2021. Lisbon, Portugal: Infraestruturas de Portugal; 2020. 21 pp. Available from: https://www.infraestruturasdePortugal.pt/pt-pt/sobre-nos/governo-societario/plano-para-igualdade. |

[42] | Palpant C . European Employment Strategy: An Instrument of Convergence for the New Member States? Brussels, Belgium: Institut Jacques Delors; 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 10]. Available from: https://institutdelors.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/policypaper18-en-3.pdf. |

[43] | Portuguese Government. Gender Equality Plan 2014-2017. Lisbon, Portugal: Portuguese Government; 2014 Feb 28. 30 pp. Available from: https://www.Portugal.gov.pt/pt/gc21/area-de-governo/defesa-nacional/informacao-adicional/igualdade-de-genero.aspx. |

[44] | PwC Portugal . Mulheres em Portugal: Onde Estamos e para Onde Queremos Ir (Women in Portugal: Where We Are and Where We Want to Go). Lisbon, Portugal: PwC Portugal; (2015) . 64 pp. |

[45] | Committee for Citizenship and Gender Equality (CIG) - Presidency of the Ministers’ Council. Portugal Gender Equality Statistics and Key Indicators. Lisbon, Portugal: Committee for Citizenship and Gender Equality (CIG); 2019. 54 pp. Report No.: 37. Available from:https://www.cig.gov.pt/documentacao-de-referencia/doc/cidadania-e-igualdade-de-genero/igualdade-de-genero-em-Portugal/. |

[46] | Committee for Citizenship and Gender Equality (CIG) - Presidency of the Ministers’ Council. Desigualdade Salarial entre Homens e Mulheres em Portugal (Salary Inequality between Men and Women in Portugal). Lisbon, Portugal: Committee for Citizenship and Gender Equality (CIG); 2018. Available from: http://cite.gov.pt/pt/destaques/complementosDestqs2/Desigualdade_salarial.pdf. |

[47] | Committee for Citizenship and Gender Equality (CIG) - Presidency of the Ministers’ Council. National-level Reviews – Portugal, Twenty-fifth Anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women and Adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995). Lisbon, Portugal: Committee for Citizenship and Gender Equality (CIG); 2019; 118 pp. Available from: https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/Gender/Beijing_20/Portugal.pdf. |

[48] | Monteiro R , Ferreira V , Saleiro S , Lopes M , Múrias C . Local Gender Equality - Guia para a Integração a Nível Local da Perspetiva de Género na Mobilidade e Transportes (Guide for the Local Level Integration of the Gender Perspective in Mobility and Transport). (2016) ; pp. 44. Available from: https://lge.ces.uc.pt/files/LGE_mobilidade_e_transportes_digital.pdf. |

[49] | Cunha L , Nogueira S , Lacomblez M . Beyond a Man’s World: Contributions from Considering Gender in the Study of Bus Drivers’ Work Activity. Work. (2014) ;47: :431–40. |

[50] | World Economic Forum. 2020 Global Gender Gap Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum; (2019) . 371 pp. |

[51] | Lisbon Metro’s Human Capital Department. Plano de Ação para a Igualdade entre Mulheres e Homens 2018–2021 (2018–2021 Action Plan for Equality between Women and Men). Lisbon, Portugal: Lisbon Metro; (2018) . 10 pp. |

[52] | Fertagus. Reports and Accounts [Internet]. Almada, Portugal: Fertagus; 2019 [updated 2021; cited 2021 Ago 25]. Available from: https://www.fertagus.pt/pt/fertagus/relatorios-e-contas. |

[53] | MTS – Metro Transportes do Sul. About MTS [Internet]. Seixal, Portugal: MTS – Metro Transportes do Sul; 2021 [updated 2021; cited 2021 Ago 25]. Available from https://www.mts.pt/sobre-o-mts/. |

[54] | Pilipiec P . The Role of Time in the Relation between Perceived Job Insecurity and Perceived Job Performance. Work. (2020) ;66: :3–15. |

[55] | Zaki S , Mohamed S , Yusof Z . Construction Skilled Labour Shortage – The Challenges in Malaysan Construction Sector. International Journal of Sustainable Development. (2012) ;4: (5):99–107. |

[56] | García-Jiménez E , Poveda-Reyes S , Molero GD , Santarremigia FE , Gorrini A , Hail Y , et al. Methodology for Gender Analysis in Transport: Factors with Influence in Women’s Inclusion as Professionals and Users of Transport Infrastructures. Sustainability. (2020) ;12: (3656). |

[57] | Federation of Transport and Communications Unions. Laws for Equality and Non-discrimination [Internet]. Lisbon, Portugal: Federation of Transport and Communications Unions; 2017 [updated 2017 Jul 02; cited 2021 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.fectrans.pt/index.php/geral-12/1791-igualdade-e-nao-discriminacao. |

[58] | Sundar V , Brucker D . “Today I Felt Like my Work Meant Something”: A Pilot Study on Job Crafting, a Coaching-based Intervention for People with Work Limitations and Disabilities. Work. (2021) ; 69: , 423–38. |

[59] | Lancman S , de Lima Barroso BI . Mental Health: Professional Rehabilitation and the Return to Work - A Systematic Review. Work. (2021) ; 69: :439–48. |