Effect of company-driven disability diversity initiatives: A multi-case study across industries

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Employers are increasingly seeking a competitive advantage through targeted hiring of people with disabilities. We conducted several case studies to learn more about companies that led in creating their own disability diversity initiatives.

OBJECTIVE:

In this article, we share insights emerging from case studies conducted across seven companies. We illustrate the motives, processes, and outcomes of these initiatives.

METHODS:

This study is built on the previously published case studies conducted across seven companies. We applied elements of consensual qualitative research (CQR) for the data collection and analyses before performing an in-depth qualitative content analysis using the data coded for each company, looking for commonalities and differences.

RESULTS:

Although practices differed, all companies experienced noted benefits. Committed leadership and complementary company values facilitated successful outcomes for initiatives. The strength or salience of disability-inclusive actions and practices appeared to moderate outcomes related to company performance, employee perceptions of the company, and cohesiveness.

CONCLUSION:

Company disability initiatives can yield positive impacts on company performance and culture. The practices we identified and their positive outcomes serve as beacons to other organizations that recognize disability as a valued part of company diversity.

1Introduction

Disability is commonplace in society but not in the U.S. labor market, where the participation rate of people with disabilities (PWD) in 2023 is nearly half that experienced by people without disabilities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023; U.S. Department of Labor, 2023). Many employers value diverse teams, but disability is too often missing from the discourse (Byrd, 2009; Chan et al., 2010; Gould et al., 2020; Kendall & Karns, 2018; Procknow & Rocco, 2016; Ross-Gordon & Brooks, 2004; Theodorakopoulous & Budhwar, 2015). A report generated by the Return on Disability Group (2014) indicated that 90% of surveyed companies prioritize diversity, yet only 4% included disability among their diversity initiatives (as cited in Casey, 2020). This aligns with recent findings from the National Organization on Disability showing a continued lack of commitment or investment towards disability-inclusive practices and cultures across the U.S. labor market (Donovan, 2020). Many stakeholders have made efforts to close this longstanding employment gap, however, reducing the disparity will require greater commitment from company leaders who make the hiring and policy decisions (Chan et al., 2010, 2021; Fraser et al., 2011).

Historically, interest in employing PWD has waxed and waned within the labor market. In times of growth and prosperity, employers were more willing to hire PWD as a means to replenish their workforce, while in times of decline and difficulty, employers tended to overlook this willing and qualified pool of workers (Allegis Group, 2018; Fry, 2018; Kaye, 2011; Rynes & Barber, 1990). More recently, there is an increasing trend in which companies employ PWD as part of a strategic business plan rather than a forced backup plan. Employers are beginning to realize that hiring PWD is an enriching and advantageous form of workplace diversity (Gould et al., 2020; Kalargyrou, 2014; Lindsay et al., 2018). Rather than legal compliance, charity, or public relations, companies are more frequently describing their primary reason for recruiting job candidates with disabilities as a way to gain a competitive advantage (Donovan, 2020; Miethlich & Šlahor, 2018; Shattuck, 2019). Research on the benefits of employing PWD strongly supports employers in this trend (Accenture, 2018; Fraser et al., 2011; Hindle, 2010; Lindsay et al., 2018). For instance, an employer study conducted by Accenture (a Fortune Global 500 company specializing in information technology services and consulting), showed American businesses that hired and supported workers with disabilities observed 28% higher revenue and 30% higher profit margins (Disability:IN, 2019).

In this changing landscape where disability is becoming a valued aspect of company diversity, employers are more frequently creating their own initiatives to hire and retain PWD (e.g., Frank et al., 2018; Hedley et al., 2017; Howlin, 2013; Huang & Chen, 2015; Hurley-Hanson et al., 2020; Lindsay et al., 2018). Companies are rapidly increasing their diversity investments to support these efforts (Holmes et al., 2021). These company-driven, disability diversity initiatives have been shown to lead to several positive business outcomes, including greater loyalty from customers and employees, as well as increased company reputation, profits, cost-effectiveness, and innovation (Kalargyrou, 2014; Lindsay et al., 2018). These initiatives, although growing, are still underresearched and have yet to become common practice in the labor market (Bernick, 2021; Granat, 2020; Nicholas & Klag, 2020). More research examining the impact of applied diversity inclusion practices in the employment of PWD is necessary to identify and develop best practices in company-driven disability initiatives (Cavanagh et al., 2017; Griffiths et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2021; Miethlich & Oldenburg, 2019).

The purpose of this project was to integrate and interpret findings from seven company-driven disability initiatives previously published as six separate articles. The previously studied case studies include a large biotechnology company (Ochrach et al., 2021), a medium-sized men’s apparel manufacturer (Grenawalt et al., 2020), a small software company focused on the inclusion of people with disabilities in their communities (Thomas, Ochrach, Phillips, & Tansey, 2021), a medium-sized global business management consulting firm (Kesselmayer et al., 2022), a small manufacturer of garden products (Thomas, Ochrach, Phillips, Anderson et al., 2021), a medium-sized industrial manufacturer (Phillips et al., 2023), and a small company selling environmentally conscious products (Thomas, Ochrach, Phillips, Anderson et al., 2021). By pulling together insights from across these separate case studies, we are better able to identify patterns and best practices in employer-initiated disability diversity initiatives. The small to medium-sized companies that make up 99.7% of U.S. employers (U.S. Small Business Administration, 2012) have largely been neglected from the public discourse on disability initiatives. Our inclusion of small to medium-sized businesses helps to correct for previous research that has focused primarily on large companies like Walgreens and Marriott (e.g., Childs, 2005; Donovan & Tilson, 1998; IBM, n.d.).

1.1Theoretical framework

Multiple theoretical frameworks and models guide diversity practices in the business sector. Two of the primary frameworks are Yang and Konrad’s model, based on a combination of resource-based and institutional theory, and the closely related Interactional Model of Cultural Diversity (IMCD).

1.1.1Yang and Konrad model

Yang and Konrad (2011) utilize resource-based theory and institutional theory to create a research model asserting, at its most basic level, that the presence of effective diversity management is key to the success of diverse companies. Consistent with this theory, the approach and emphasis employers give to diversity has been shown to have a significant impact on the diversity of an organization (Besler & Sezerel, 2012; Black et al., 2019; Brooke et al., 2018; Hayes et al., 2020; Ng & Sears, 2018; Markel & Elia, 2016; Rashid et al., 2017). A meta-analysis considering 25 years of company climate research suggests a strong commitment to a pro-diversity climate, combined with general support for the well-being of employees, produces greater job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and performance (Holmes et al., 2021). Research has also suggested that all employees in a company, not just those from a diverse or marginalized population, benefit from well-implemented diversity management practices (Ashikali & Goeneveld, 2015).

In their model of effective diversity management, Yang and Konrad (2011) list multiple antecedents to effective diversity management. These antecedents include management’s ability to set social and professional norms of inclusivity and to recognize the value of diversity within the workplace. Implementation of diversity management practices is associated with greater perceived legitimacy from external entities (e.g., government, advocacy groups, and customers) and greater perceptions of fairness internally. The realization of a more diverse organization is believed, in this model, to drive the development and implementation of effective business strategy and sustained competitive advantage (Yang & Konrad, 2011).

1.2Interactional model of cultural diversity

The IMCD focuses on four primary organizational contexts for influencing the success of a diversity initiative, namely (a) organizational culture and acculturation processes; (b) structural integration, or the level of heterogeneity in the formal structure of an organization; (c) informal integration, or the level of access to social networks and mentoring activities; and (d) institutional bias, including the policies, procedures, and patterns of work that may favor the majority population (Cox, 1993). These organizational factors, along with individual and group-level factors, predict overall success in creating a diverse company culture. Another tenet associated with IMCD is focused on climate strength, or the degree to which employees perceive a strong company priority for an element of company climate (Holmes et al., 2021; Schneider et al., 2002). Schneider et al. (2002) argue that more intensive situations lead to better climates. Applied to disability diversity, it can be hypothesized that the strength of a situation could be captured by the uniqueness or intensity of the inclusion efforts. It seems possible that a novel or intense effort to be inclusive would produce greater benefit to the work climate compared to a routine or less intense effort to include diverse workers. Because the companies we studied included a range of intensities, we considered this tenet as strength of action in the synthesis of the data.

Notably, neither of these two frameworks emphasize disability as an element of diversity. While we reviewed models of disability diversity in the workplace (e.g., Stone & Colella, 1996), unlike the models of Yang and Konrad (2011) and the IMCD, these disability-specific models tend to overshadow the assumption of disability as a valued form of diversity with questions related to person-environment fit, employee competency, and employer stereotypes and discrimination. Fit and competency are factors in any employment decision, but in using the diversity models selected, we emphasize the largely untapped potential of viewing disability as a valued form of diversity.

2Methods

We conducted in-depth case studies for each of the companies studied, using elements of consensual qualitative research (CQR) for aspects of the design, data collection, and analysis (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Hill et al., 2012; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016; Yin, 2018). In-depth case studies provided an ideal approach for the exploration of events or phenomena from multiple sources and with a consideration of the company and the broader environment where the events occurred (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Corbin & Strauss, 2015; Crowe et al., 2011; Miles & Huberman, 1994). Case studies are a useful tool for understanding the impact of specific business practices and supportive management in the employment of diverse populations (Cavanagh et al., 2017; Maxwell, 1996; Miles & Huberman, 1994). Similar case study designs have been successfully implemented to identify and assess best practices in companies and agencies serving people with disabilities (e.g., Anderson et al., 2014; Phillips et al., 2016). This manuscript represents a continuation of the analysis carried out across the previously described individual case studies to identify converging themes across the companies studied.

2.1Companies

A total of seven companies are included in this multi-case study analysis. As briefly described in the previous section, these companies varied across industries and sizes. Most of the companies recruited were in the Midwest. Researchers worked with their own networks and state employment agencies to identify companies with a reputation for inclusive disability hiring practices. Among the companies identified, we contacted companies that conveyed a strong belief in the benefits of employing PWD and held an expressed commitment to inclusive hiring and retention practices. Members of the research team reached out to company leadership to ascertain their level of interest in being part of a case study focused on their disability initiative. After agreeing to participate, members of the research team worked closely with company leadership to initiate data collection, organize a site visit, and conduct interviews and focus groups.

2.2Data collection procedures

We collected data from each company through a combination of on-site observations, individual interviews, focus groups, evaluation of company policies and written materials, and the company websites. The multiple research teams completing the data collection consisted of rehabilitation psychology and rehabilitation counseling faculty and doctoral students representing multiple U.S. universities. To maintain consistency across multiple case studies, lead researchers developed a procedural document for the teams of each case study to reference and follow. As part of this procedure, team members discussed potential biases before engaging in data collection and again before completing the analysis to reduce the potential for biases to influence the results. Members of the research team consistently shared the belief that employment of PWD had the potential to improve company performance and offer a competitive advantage over competitors who do not employ PWD. They also tended to hold positive views of companies that were inclusive of PWD in their workforce. That said, none of the research team had experience running a company with more than a small number of employees and none held strong notions regarding the inclusive practices that employers should or should not engage in before the study. The discussion and documentation of team biases were accompanied with a conversation of how these biases could be minimized in affecting the research team’s interpretation of the data.

2.3Measures

Researchers conducted focus groups and interviews using semi-structured interviews. In accordance with CQR, the interview consisted of open-ended questions that were constructed to encourage responses without limiting them to a predetermined point of view (Burkard et al., 2012). Optional probing questions were included in the semi-structured interview to facilitate the elaboration of ideas while minimizing interviewer influence on the response. The semi-structured nature of the interview protocol provided consistency across interviews while still allowing for the flexibility to pursue the unique knowledge and perspectives of each group or individual stemming from their different roles in the organization. For more details about the interview protocol, see Grenawalt et al. (2020).

2.4Data analyses

Data analysis and coding were initially performed by one to three researchers using the transcribed interviews, original audio recordings, and other data sources to provide important context. The number of initial coders varied by the amount of data collected from each company and by the complexity and subjectivity of the information. Researchers reviewed and coded audio files and transcripts. This involved identifying objective efforts (i.e., policies, and statements about employer policies and practices) in addition to subjective information about how those efforts affected the people and outcomes of the company’s disability efforts. This was an iterative process that involved creating domains and categories from the coded information. Initially, the coding team (one to three individuals) independently engaged in an iterative process of identifying and extracting meaningful data units (i.e., phrases, sentences, paragraphs) and assigning them to domains. In the case of multiple coders, individual coding of domains was then combined through a consensus seeking process across coders to obtain a working version of the domains. After obtaining consensus, coders independently coded the remaining interviews prior to meeting again to achieve final consensus across all interviews.

Researchers created categories in the next phase of the analysis; this was accomplished by having one to three coders take a subset of the interviews and individually develop categories within the domains. In the case of more than one coder, consensus was achieved for each category through an iterative process involving multiple meetings to complete the coding of categories for the remaining interviews. After consensus was achieved, the analysis was sent to an auditor who was familiar with the project but had not assisted with any aspect of the coding. The auditor individually reviewed the domains and categories and provided suggested changes, additions, and deletions to the coding team. The coding team then arrived at a consensus in determining whether to accept or reject each of the suggested changes offered by the auditor. Once created, the coding and narrative of the case study were brought to the larger research team for a community-based approach to refining and improving the accuracy of the case study. This coding process was aided by the use of NVivo 12 software in some cases and Microsoft Excel for others. Once data analysis was complete, the results were sent to each company for member checking to ensure that the information drawn from interviews and written materials was clear and accurate.

3Integrated results

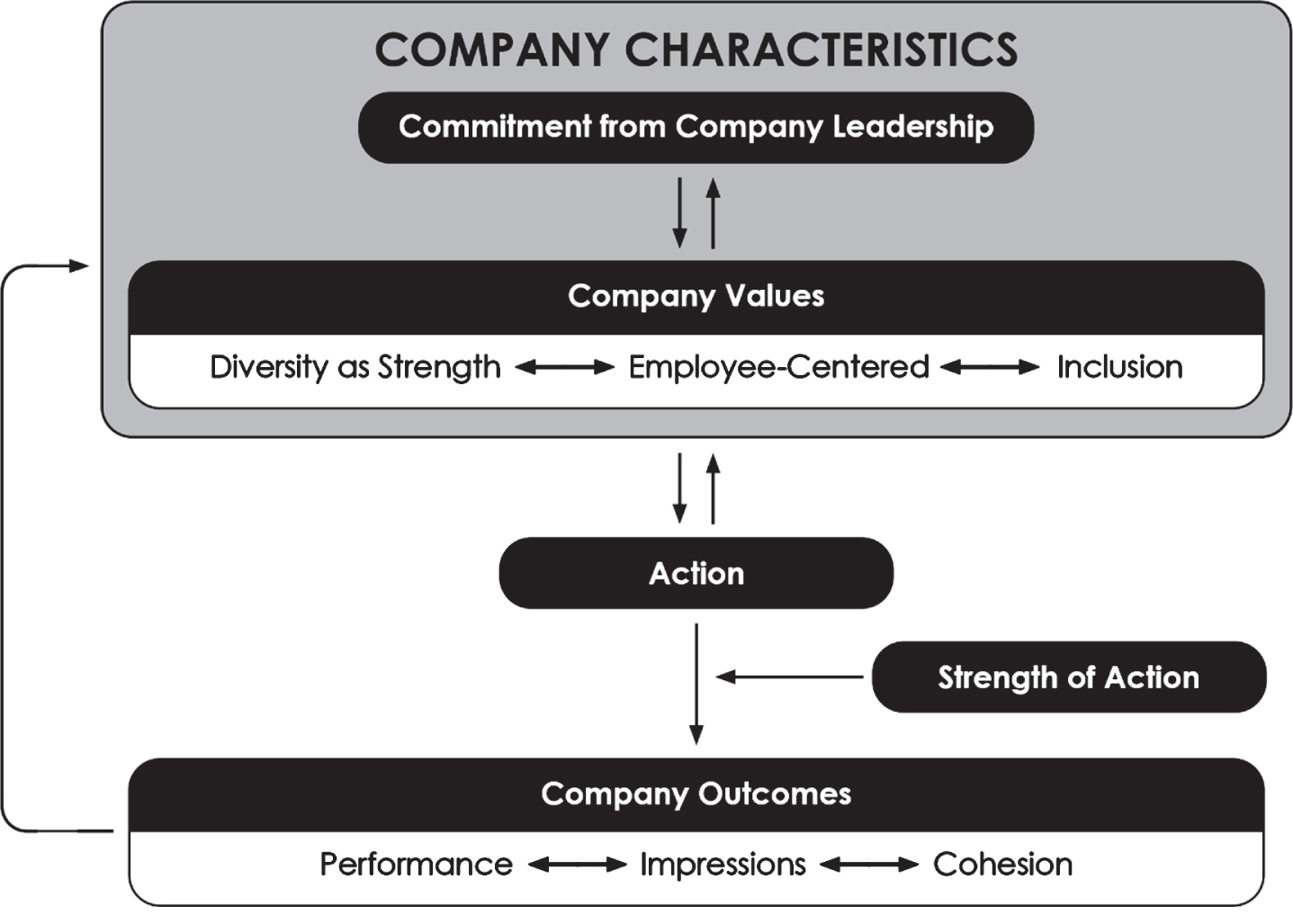

Disability initiatives varied between companies. Four of the companies targeted employees with disabilities generally, while three focused more specifically on employing employees with autism. Among the companies studied, those that were inclusive of all disability populations put greater emphasis on their company mission, values, and policies. For example, the large biotechnology company placed the greatest emphasis on maintaining an organizational structure that prioritized resources for inclusive practices and infused company values throughout each work team. Among the three companies with programs designed for employees with autism, initiatives were much more focused on addressing the specific needs of this population in all the steps of employment ranging from completing an application, to onboarding, to job retention. Initiatives for all the medium and large companies included awareness training for company employees without disabilities as an important element of the program. A description of the specific policies and practices of each company can be found in the corresponding peer-reviewed articles (Grenawalt et al., 2020; Kesselmayer et al., 2022; Ochrach et al., 2021; Phillips et al., 2023; Thomas, Ochrach, Phillips, Anderson, et al., 2021; Thomas, Ochrach, Phillips, & Tansey, 2021). For our purpose, we focus on converging themes across these case studies. We identified salient commonalities across multiple case studies and discuss these commonalities below, broken down by company characteristics and outcomes. Figure 1 provides a visual summary of findings through a model of company disability diversity initiatives.

Fig. 1

A model of company-driven disability diversity.

3.1Common company characteristics

The two most prominent themes among the company-driven disability initiatives were a commitment from company leadership and a company embodiment of key values. These two common themes were inseparable in the companies studied. Company leadership was consistently credited with having a significant influence on what was valued, and company leadership looked to those same values to guide company operations. Without exception, employees viewed the expressed and observed commitment of company leadership as key to the successful hiring and retention of employees with disabilities. Of note, the most salient comments about commitment among company leadership came from the frontline workers who conveyed that they looked to the CEO and other leaders in the company for signals of whether the company’s disability efforts were to be prioritized or merely talked about. For instance, in the global business management consulting firm, a frontline employee shared that strong support from senior leadership was an essential indicator that they should use their time and resources for the disability initiative, making it easier for everyone involved. An employee of the company frankly shared their opinion that, without unwavering support from “everyone higher up,” their company efforts would not be successful. The leadership, appreciating the importance of messaging, stated that they prioritized informing all employees that leadership was highly involved and supportive of the effort. Employees at the large biotechnology company confirmed that the message was received and served as a critical endorsement of the company’s disability initiative.

Several company values were mentioned as being important to disability diversity efforts, with most shared by leaders across each of the companies. Among these, a few stood out as universal across companies and essential to their diversity efforts. These were (a) viewing diversity as a strength, (b) being employee-centered, and (c) emphasizing inclusion. Nearly all companies spoke of a value for diversity that was not exclusively disability-focused. Companies tended to describe disability as being another element of diversity that deserved as much priority as other forms of diversity rather than as something unique or separate from the company’s broader diversity efforts. The disability initiatives of each company seemed to emanate from this broader value while also helping strengthen the company’s value for diversity in the process. Employees frequently stated that their company’s disability initiative demonstrated that their organization was serious about their stated values regarding diversity. Multiple interviewees across different companies stated that the level of commitment their company showed for increasing diversity extended well beyond compliance with disability employment laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA, 1990, 2008). Companies reported that the value they placed on a diverse workplace was not based solely on principle but also on profits. In other words, the companies valued diversity while also holding strongly that diversity was valuable to company performance and outcomes.

Companies in the study also shared a value of being employee-centered. For the companies, being employee-centered meant acknowledging that employees did not exist solely to help the company but that the company also existed to help and support employees. Leadership in the large biotechnology company, for example, noted that, while most companies have a mission statement, they had placed a great deal of effort on living their mission statement, including treating employees as their most valuable resource. Companies demonstrated their value for employees in several ways, including by supporting their upward mobility within the company or paying for them to pursue additional schooling. Some companies had a department or individual within the company dedicated to the health and wellness of employees. One company encouraged employees to provide meaningful volunteer efforts by compensating them for time and expertise spent supporting a cause in the community.

Companies with an employee-centered orientation anticipated unforeseeable employee needs and demonstrated flexibility when needs arose. This flexibility was often tied to the success of their disability initiative but was also equally applied to employees experiencing a variety of non-disability disruptions to their work (e.g., short-term injuries, helping an aging parent through a health crisis, managing a child’s problem behavior at school, car problems). Framed as a commitment to flexibility, leaders in a medium-sized industrial manufacturer stated that they commonly go beyond the written policy to meet the needs of employees. Leadership in the small manufacturer of garden products argued that maintaining a high level of flexibility was much more important to operations than written policies or procedures for their company. Multiple companies emphasized that building a culture of flexibility requires more than a simple change of mindset. They noted that willingness to be flexible must be coupled with a plan and, at times, accompanying resources to ensure that flexibility can be offered to employees without jeopardizing the company. Among the companies interviewed, all had processes in place to manage unforeseen employee needs. Several had dedicated financial resources for meeting employee needs so that providing flexibility to employees was not experienced as a strain on supervisors and a drain on the company.

The third value shared across companies was inclusion. Across case studies, company leadership demonstrated a sensitivity to, and awareness of, employee needs for community and belonging. These considerations were not always easy or straightforward. For instance, in the medium-sized industrial manufacturer, an employee with autism was initially situated in an office that was a bit removed from other offices and from the production taking place in the company. This was done initially at the request of the autistic employee. However, with time, this same employee became more comfortable in the new environment and desired a more central office space. At the time of the site visit, the company was preparing this new space. A medium-sized men’s apparel company made efforts to incorporate employees with autism into the formal and informal socializing taking place within the workplace. Some companies found that disability awareness training helped those who worked alongside employees with disabilities to appreciate differences in individual social preferences and behaviors.

3.2Common outcomes

Three common outcomes emerged from across the case studies. These were (a) company performance, (b) employee impressions of the company and of their work, and (c) employee cohesiveness within the company. Each of the outcomes were consistently mentioned as producing benefits to company and employees alike. Changes in company performance were frequently discussed in terms of financial gains for the company. Employee impressions of the company were often expressed as an increased desire to remain with the company. Employee cohesiveness as the result of initiatives was most often described as a greater shared sense of belonging and purpose.

We begin with a discussion of performance. All but one of the companies reported improved company performance from employing people with disabilities, with one company expressing more mixed perceptions. A lead at one company summarized the general statements about company performance saying, “It’s not charity. It’s a positive impact to your company.” Within the companies reporting the greatest gains in performance, multiple people spoke of greater efficiencies, increased productivity, and decreased overtime. In many of these companies, the disability initiative employed strategic hiring to address neglected tasks or processes. For instance, one company noted that the disability initiative reduced the amount of time other employees spent doing tasks that were unrelated to their positions. Interviewees across companies reported a greater ability to focus on their primary tasks. Some also reported higher customer satisfaction associated with the increased timeliness of employees’ work. In other cases, the improved performance contributed to companies’ abilities to recruit and retain a better workforce by strategically including people with disabilities in the recruitment pool.

Disability diversity efforts had even more salient impacts on employees’ impressions of the company they worked for. This was most pronounced in the companies that had not targeted employing people with disabilities prior to their disability initiative. Several employees noted that the disability initiative helped them to see their company and leadership in a more positive and humane light. Across organizations, employees shared about their increased sense of purpose and pride in their company because of its efforts to create a disability-diverse work environment. One long-term employee in the men’s apparel clothier stated that she was, for the first time, excited to tell people where she worked because her company prioritized employing PWD. Some newer employees reported that the disability initiative factored into their decision to work for the company. Multiple people, from leadership to the frontline, stated that being part of their company’s disability initiative had made them feel better about themselves.

Finally, companies reported a shared sense of pride and purpose stemming from disability initiatives along with increased cohesion within the organization. For instance, a manager with the men’s apparel clothier stated that their disability diversity efforts brought people together in a way that other aspects of the job had not. Another employee with the industrial manufacturing company stated that they were amazed by the improved culture resulting from their disability diversity efforts. These case studies support that disability initiatives across different sectors can fulfill employees’ desire for additional meaning to the work that they do, beyond the tasks of their job. While producing a product or sharing knowledge has its rewards, employees in these organizations experienced an increased sense of purpose and meaning at work through efforts to make their workplace more representative of the people living in their communities.

Based on the results of these case studies, a well-executed disability initiative has the power to enliven a company’s mission and values. Leadership within our study stated that company values drove the initial establishment of a disability initiative. Based on our observations, disability diversity efforts provided an effective mechanism for infusing company values throughout the company. Frontline workers across companies emphasized that the actions their organization had taken to demonstrate its values conveyed the company’s priorities and value for its employees. Multiple interviewees reported feeling more heard and understood since company initiatives began and more satisfied with their employment. Figure 1 describes how outcomes solidify company values. The final major element of the model is action.

3.3Action

Companies varied in their approach to hiring and retaining employees with disabilities, and it is beyond the scope of this project to identify best practices among the actions we observed. That said, the actions companies took reflected strong values for diversity, being employee-centered, and for inclusion. These three values, in unison, often appeared to dictate the actions of the companies studied. For example, companies hiring workers with autism found that it was crucial to take an employee-centered approach when determining how an employee with autism desired to be included. Company leadership did not leave the meaning of the disability initiative to the interpretation of supervisors or frontline workers. Besides expressing broad support for initiatives, leadership often emphasized personal and company values motivating the effort as well as the expectation that such efforts would produce benefits to the company and, often, to the broader community.

As previously noted, climate strength and situation strength are assumed to moderate disability diversity outcomes. Although much more research is needed to test this hypothesis, observed differences in the strength of actions taken across the seven companies provided strong initial support. The greater intensity and novelty of inclusion efforts appeared to be positively associated with company outcomes. Multiple factors may be at work in this relationship between intensity and outcomes. As hypothesized by Schneider et al. (2002), case study data suggested that stronger action (Schneider referred to this as strength of situation) created a stronger and more cohesive climate of support. Regarding novelty, we observed that accommodating more intensive inclusion needs often led to greater innovations within a company. Such efforts were reported to produce improved processes for hiring, onboarding, and retaining employees. For example, a senior manager in the medium-sized men’s apparel clothier stated that the task analysis completed to support new hires with autism significantly improved information sharing across departments and improved production. Employees in another company reported that the intensive onboarding process they engaged in to train an employee with a disability led to major improvements in the onboarding process for other employees, thereby reducing the time needed to fully train new hires and reducing the amount of follow-up training that was required.

Companies that adopted a more limited approach to disability diversity described fewer positive outcomes. In a company with an inclusion initiative resulting in the hire of only one disabled employee on a part-time trial basis, employees noted that the effort conveyed mixed messaging about whether or not disability diversity was a priority of the company. Of note, multiple frontline workers shared that the employee with a disability in this company was being underutilized. Based on these findings, strength of action (captured here by the novelty or intensity of the inclusion practices) is included in the model as a moderator of the relationship between action and company outcomes, where strength of action is predicted to produce differing levels of benefit to the company.

4Discussion and implications

The findings from this multi-case study data are aligned with the current literature that supports a business case for employing PWD. We found both personal and organizational benefits at every level of the organizations participating in this research. We consistently observed company characteristics as key influences on how initiatives were implemented and their outcomes. Findings aligned with and added to quantitative findings from Chan et al. (2021) in suggesting that having committed company leadership and strongly held company values for diversity; having an employee-centered organization; and supporting inclusivity are all highly important to the success of disability initiatives. Companies in the studies experienced many benefits from their initiatives. We found these benefits fit into categories of enhanced performance, improved impressions of the company and employee’s role in the company, and increased employee cohesion. These benefits emanated to most every part and person connected to the disability initiative. The degree of benefit from the disability initiatives appeared to be positively associated with the level of intensity and adaptation involved in carrying it out, as predicted in the tenets of the IMCD.

Although it is possible that a company could create a successful disability initiative without leadership support, our case studies suggest the involvement of leadership is critical to the long-term success of these initiatives. In line with the present study and theoretical tenets of the IMCD and Yang and Konrad’s model described previously, research has pointed to the critical influence of CEOs when human resource departments seek to implement new practices through line managers (Trullen et al., 2016). Direct support and participation from leadership legitimize efforts and serve as a model for other employees (Trullen et al., 2016). The included companies viewed disability as a valued element of diversity, but they did not restrict their focus to disability when acting on values of inclusion and being employee-centered. The fact that employees without disabilities reported they were offered the same flexibility afforded to employees with disabilities when a need arose likely contributed to the increases in cohesion and camaraderie reported with the implementation of the disability initiatives. This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that accommodating the needs of all employees, those with and without disabilities, is important to company success (Kulkarni, 2016).

Company climate plays an important role in workplace inclusion and creating an environment in which individuals with disabilities thrive (Gilbride et al., 2003; Stone & Colella, 1996). A theme captured by this research that has received scant attention in the broader literature is the personal influence disability initiatives have on frontline workers and leadership. Across all case studies, employees spoke of having a more positive perception of their company and their role in it. These results mirror the findings of other studies in which respondents felt having co-workers with autism contributed to the workplace culture and improved workplace morale (Scott et al., 2017). These results suggest that disability inclusive environments improve the work climate for all employees (Hartnett et al., 2011; Travis, 2009). In a labor market in which organizations are constantly seeking ways to increase commitment and longevity, employee statements that they feel better about what they do at work and their expressions of pride in their company’s focus on inclusivity are noteworthy.

4.1Future directions

Conducting this descriptive case study research has produced several insights about processes that affect company-driven disability diversity efforts and their outcomes. However, several gaps still exist in our knowledge of how companies can successfully implement diversity strategies within organizations (Holmes et al., 2021; Yang & Konrad, 2011). Many companies heavily invest in programs to increase employee commitment and satisfaction to prevent costly employee turnover. Our study suggests that programs including disability diversity may be powerful mechanisms for accomplishing these goals while maximizing long-term performance. Additional quantitative research is needed to determine the degree to which qualitative observations of improved company performance and culture influence employee commitment and satisfaction. We hypothesize, based on our findings, that companies that are not directly focused on providing a socially valued product or service may stand to gain the greatest benefit from such an endeavor. Interestingly, several participants stated that they were drawn to work for their current company because of its disability diversity efforts and the sense of purpose they imagined themselves experiencing as part of the organization. In more than half of the case studies conducted, at least one employee reported being drawn to the company because of the disability initiative. This was the case even for companies that had only recently begun their efforts to employ PWD. With additional research, we may someday be able to quantify the benefits of disability diversity efforts on employee recruitment and retention and compare them with the myriad of other efforts companies make to maintain a strong and dedicated workforce. In doing so, we will continue to distance ourselves from the erroneous motive of employing PWD based on charity alone.

Researchers have suggested that when a company implements a diversity initiative, it becomes a part of the company’s identity (Cole & Salimath, 2013). Although we observed many signs of this occurring in the companies studied, longitudinal research is needed to better understand how this process unfolds over time. Cole and Salimath (2013) caution that a half-hearted effort to infuse a company with diversity may reduce the perceived legitimacy of these efforts, which can deteriorate corporate unity and climate. Our data supports this idea that commitment and strength of action influence perceived legitimacy, but more research is needed to test the relationship between strength of action and company outcomes over time.

Another area for greater exploration is the optimal level of integration, specifically for neurodiverse employees. Management, supervisors, and co-workers all described struggling at times with the right amount of integration or involvement when working alongside employees with autism. In our qualitative studies, the answer appeared to vary across people and companies, with some finding that employees with autism seemed happier with more opportunities to interact than others. In another qualitative study, researchers showed that psychosocial support, social acceptance, and assistance with completing work tasks were among the most influential keys to integrating employees with disabilities (Kulkarni & Lengnick-Hall, 2011). These priorities were manifested in several of the case studies, which may help to explain how the companies developed and maintained unity through their initiative. More research is needed to better identify optimal levels of social integration for neurodiverse employees and others who may experience increased anxiety and other negative consequences from too much social interaction. Companies may benefit from more formalized processes to guide an employee-centered approach for including neurodiverse employees and others who have unique preferences and needs related to the social environment.

4.2Limitations

The results from these case studies should be considered within the context of a few important limitations. First, while providing valuable insights and increased understanding of the processes and characteristics associated with successful disability diversity efforts, this work represents the experience of only a small number of companies and work settings. As such, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results. Looking forward, it would be useful to evaluate company-led disability initiatives using quantitative approaches for testing the generalizability of findings. Regarding the interpretation of findings, several efforts were made to minimize the effect of researcher bias on the results, including a discussion of biases before the analysis and the involvement of multiple researchers in discerning themes in the data. Despite these efforts to adhere to a research method that would minimize bias, it is possible that another research team may have varied in what they chose to highlight in interpreting the data. Despite these limitations, we believe the present project provides important implications about how to successfully implement a company-driven disability diversity initiative within an organization.

5Conclusion

Employment disparities between people with and without disabilities continue to plague the U.S. economy. People with disabilities represent a pool of underutilized potential employees who can bring added capacity and competency to the workplace. Within this study, employees and supervisors repeatedly supported this idea, reporting positive perceptions toward the inclusion of people with disabilities in their workplace. These case studies support that it is beneficial for companies to view disability as a valued and valuable aspect of diversity in the workplace. Given the structure of the U.S. economy, any significant reductions in employment disparities will need to be driven largely by employers who come to view people with disabilities as providing an added benefit to their company. The purpose of this article has been to describe a series of case studies conducted with multiple medium- and small-sized companies that created or carried out their own disability diversity initiatives. Each case study provided perspectives of employees and leadership within organizations while also describing the practices that were most salient to their initiative’s success. Identifying employer practices implemented by companies with a successful record of hiring PWD can help employers see inclusion and integration of disability as a business opportunity rather than just a legal requirement (Casey, 2020).

The case studies generated several implications for businesses that are considering starting their own disability diversity effort. Companies should consider how their leadership will demonstrate commitment to a diversity program and how they can cultivate a mission and set of values that are conducive to a disability diversity initiative. This research also raises questions for future studies about how individuals with disabilities, particularly neurodiverse employees, can be optimally integrated into an organization. The results of this study support that companies can experience a range of benefits through developing an employer-led disability diversity initiative, such as improving company performance, increasing the sense of purpose among employees, and creating greater cohesion within the organization.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgments.

Funding

The contents of the journal publication were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RT5041) awarded to Paul Wehman. NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this journal article do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Ethics statement

This paper was conducted and written in compliance with APA ethical standards. The original studies this article was based on were conducted primarily under the Institutional Review Board approval of the University of Wisconsin-Madison (protocol #2019-0062).

Informed consent

As per the protocol, verbal consent was obtained after provision of an informed consent statement.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

1 | Accenture. (2018). Getting to equal: The disability inclusion advantage. The American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD) and Disability: IN. https://www.accenture.com/content/dam/accenture/final/a-com-migration/pdf/pdf-89/accenture-disability-inclusion-research-report.pdf |

2 | Allegis Group. (2018). Global workforce trends. Retrieved from www.allegisgroup.com |

3 | Americans with Disabilites Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. §12101 et seq. (1990). https://www.ada.gov/law-and-regs/ada/. |

4 | Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act, 42 U.S.C. Ch. 126 §12101 (2008). |

5 | Anderson, C. A. , Leahy, M. J. , DelValle, R. , Sherman, S. , Tansey, T. N. ((2014) ) Methodological application of multiple case study design using modified consensual qualitative research (CQR) analysis to identify best practices and organizational factors in the public rehabilitation program, Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 41: 87–98. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-140709 |

6 | Ashikali, T. , Groeneveld, S. ((2015) ) Diversity management for all? An empirical analysis of diversity management out-comes across groups, Personnel Review 44: (5), 757–780. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2014-0216 |

7 | Baxter, P. , Jack, S. ((2008) ) Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers, The Qualitative Report 13: (4), 544–559. |

8 | Bernick, M. (2021, January 12). The state of autism employment in 2021. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelbernick/2021/01/12/the-state-of-autism-employmentin-2021/?sh=2632cd0c59a4 |

9 | Besler, S. , Sezerel, H. ((2012) ) Strategic diversity management initiatives: A descriptive study, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 58: 624–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1040 |

10 | Black, M. H. , Mahdi, S. , Milbourn, B. , Thompson, C. , D’Angelo, A. , Ström, E. , Falkmer, M. , Falkmer, T. , Lerner, M. , Halladay, A. , Gerber, A. , Esposito, C. , Girdler, S. , Bölte, S. ((2019) ) Perspectives of key stakeholders on employment of autistic adults across the United States, Australia, and Sweden, Autism Research 12: (11), 1648–1662. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2167 |

11 | Brooke, V. , Brooke, A. M. , Schall, C. , Wehman, P. , McDonough, J. , Thompson, K. , Smith, J. ((2018) ) Employees with autism spectrum disorder achieving long-term employment success:A retrospective reviewof employment retention and intervention, Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 43: (3), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796918783202 |

12 | Burkard, A. W. , Knox, S. , Hill, C. E. (2012). Data collection. In C. E. Hill (Ed.), Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena (pp. 83-101). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. |

13 | Byrd, M. Y. (2009). Diversity training: What are we really talking about. In T. J. Chermack, J. Storberg-Walker&C. M. Graham (Eds.), Academy of Human Resource Development Conference Proceedings (pp. 203-208). Washington, DC: Academy of Human Resource Development. |

14 | Casey, C. (2020, March 19). Do your D&I efforts include people with disabilities? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/03/do-your-di-efforts-include-peoplewith-disabilities |

15 | Cavanagh, J. , Bartram, T. , Meacham, H. , Bigby, C. , Oakman, J. , Fossey, E. ((2017) ) Supporting workers with disabilities: A scoping review of the role of human resource management in contemporary organisations, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 55: 6–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12111 |

16 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023). “Disability Impacts All of Us.” https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html. |

17 | Chan, F. , Strauser, D. , Maher, P. , Lee, E. , Jones, R. , Johnson, E. T. ((2010) ) Demand-side factors related to employment of people with disabilities: A survey of employers in the Midwest region of the United States, Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 20: (4), 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-010-9252-6 |

18 | Chan, F. , Tansey, T. N. , Iwanaga, K. , Bezyak, J. , Wehman, P. , Phillips, B. , Strauser, D. , Anderson, C. ((2021) ) Company characteristics, disability inclusion practices, and employment of people with disabilities in the post COVID-19 job economy: A cross-sectional study, Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 31: 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09941-8. |

19 | Childs J.T. Jr ((2005) ) Managing workforce diversity at IBM: A global HR topic that has arrived, Human Resource Management 44: (1), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20042 |

20 | Cole, B. M. , Salimath, M. S. ((2013) ) Diversity identity management: An organizational perspective, Journal of Business Ethics 116: (1), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1466-4 |

21 | Corbin, J. , Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.), Sage Publications. |

22 | Cox, T. (1993). Cultural diversity in organizations: Theory, research and practices. Berrett-Koehler. |

23 | Creswell, J. W. , Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage. |

24 | Crowe, S. , Cresswell, K. , Robertson, A. , Huby, G. , Avery, A. , Sheikh, A. ((2011) ) The case study approach, BMC Medical Research Methodology 11: (100), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100 |

25 | Disability:IN. (2019). Why companies who hire people with disabilities outperformed their peers? https://disabilityin.org/disability-equality-index/why-companies-who-hire-people-with-disabilities-outperformed-their-peers/# |

26 | Donovan, R. (2020). Design delight from disability. Report summary: The global economics of disability. Return on Disability. https://www.rod-group.com/content/rodresearch/edit-research-design-delight-disability-2020-annualreport-global-economics |

27 | Donovan, M. R. , Tilson G.P. Jr ((1998) ) The Marriott Foundation’s Bridges. . . from school to work’ program—a framework for successful employment outcomes for people with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 10: 15–21. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-1998-10104 |

28 | Frank, F. , Jablotschkin, M. , Arthen, T. , Riedel, A. , Fangmeier, T. , Hölzel, L. P. , van Elst, L. T. ((2018) ) Education and employment status of adults with autism spectrum disorders in Germany –Across-sectional-survey, BMC Psychiatry 18: (75), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1645-7 |

29 | Fraser, R. , Ajzen, I. , Johnson, K. , Hebert, J. , Chan, F. (((2011) ) Understanding employers’ hiring intention in relation to qualified workers with disabilities, Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 35: (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-2011-0548 |

30 | Fry, R. (2018). Millennials are the largest generation in the U.S. labor force. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://pewrsr.ch/2GTG00o |

31 | Gilbride, D. , Stensrud, R. , Vandergoot, D. , Golden, K. ((2003) ) Identification of the characteristics of work environments and employers open to hiring and accommodating people with disabilities, Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 46: (3), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/00343552030460030101 |

32 | Gould, R. , Harris, S. P. , Mullin, C. , Jones, R. ((2020) ) Disability, diversity, and corporate social responsibility, Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 52: 29–42. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-191058 |

33 | Granat, W. L. ((2020) ) First race, then sex, now disability: The fight towards increased and equal employment of individuals with disabilities, Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development 2: (33), 183–216. |

34 | Grenawalt, T. A. , Brinck, E. A. , Friefeld Kesselmayer, R. , Phillips, B.N. , Geslak, D. , Strauser, D. R. , Chan, F. , Tansey, T. N. (2020). Autism in the workforce: A case study. Journal of Management and Organization, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2020.15 |

35 | Griffiths, A. J. , Hurley-Hanson, A. , Giannantonio, C. M. , Mathur, S. K. , Hyde, K. , Linstead, E. ((2020) ) Developing employment environments where individuals with ASD thrive: Using machine learning to explore employer policies and practices, Brain Sciences 10: (9), 632–655. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10090632 |

36 | Hartnett, H. P. , Stuart, H. , Thurman, H. , Loy, B. , Batiste, L. C. ((2011) ) Employers’ perceptions of the benefits of workplace accommodations: Reasons to hire, retain and promote people with disabilities, Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 34: (1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-2010-0530 |

37 | Hayes, T. L. , Oltman, K. A. , Kaylor, L. E. , Belgudri, A. ((2020) ) Howleaders can become more committed to diversity management, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 72: (4), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000171 |

38 | Hedley, D. , Uljarević, M. , Cameron, L. , Halder, S. , Richdale, A. , Dissanayake, C. ((2017) ) Employment programmes and interventions targeting adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature, Autism 21: (8), 929–941. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316661855 |

39 | Hindle, K. , Gibson, B. , David, A. ((2010) ) Optimising employee ability in small firms: Employing people with a disability, Small Enterprise Research 17: (2), 207–212. https://doi.org/10.5172/ser.17.2.207 |

40 | Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. |

41 | Holmes, O. , Jiang, K. , Avery, D. R. , McKay, P. F. , Oh, I. -S. , Tillman, C. J. ((2021) ) A meta-analysis integrating 25 years of diversity climate research, Journal of Management 47: (6), 1357–1382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320934547 |

42 | Howlin, P. ((2013) ) Social disadvantage and exclusion: Adults with autism lag far behind in employment prospects, Journal of the American Academy of Child&Adolescent Psychiatry 52: (9), 897–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.06.010 |

43 | Huang, I.-C. , Chen, R. K. ((2015) ) Employing people with disabilities in the Taiwanese workplace: Employers’ perceptions and considerations, Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 59: (1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355214558938 |

44 | Hurley-Hanson, A. E. , Giannantonia, C. M. , Griffiths, A-J. (2020). Autism in the workplace: Creating positive employment and career outcomes for Generation A. Palgrave Macmillan. |

45 | IBM (n.d.) The Accessible Workforce. https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/ibm100/us/en/icons/accessibleworkforce/ |

46 | Kaye, H. S. , Jans, L. H. , Jones, E. C. ((2011) ) Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 21: (4), 526–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9302-8 |

47 | Kalargyrou, V. ((2014) ) Gaining a competitive advantage with disability inclusion initiatives, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality&Tourism 13: (2), 120–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2014.847300 |

48 | Kendall, K. M. , Karns, G. L. ((2018) ) The business case for hiring people with disabilities, Social Business 8: (3), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1362/204440818X15434305418614 |

49 | Kesselmayer, R. F. , Ochrach, C. M. , Phillips, B. N. , Mpofu, N. , Chen, X. , Lee, B. , Geslak, D. , Tansey, T. N. ((2022) ) Case study of an autism employment initiative in a global management consulting firm, Rehabilitation Counselors and Educators Journal 11: (1). https://doi.org/10.52017/001c.32416 |

50 | Kulkarni, M. ((2016) ) Organizational career development initiatives for employees with a disability, The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27: (14), 1662–1679. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1137611 |

51 | Kulkarni, M. , Lengnick-Hall, M. L. ((2011) ) Socialization of people with disabilities in the workplace, Human Resource Management 50: (4), 521–540. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20436 |

52 | Lindsay, S. , Cagliostro, E. , Albarico, M. , Mortaji, N. , Karon, L. ((2018) ) A systematic review of the benefits of hiring people with disabilities, Journal or Occupational Rehabilitation 28: 634–655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9756-z |

53 | Markel, K. S. , Elia, B. ((2016) ) How human resource management can best support employees with autism: Future directions for research and practice, Journal of Business and Management 22: (1), 71–84. https://www.chapman.edu/business/%5C_files/journals-and-essays/jbm-editions/jbm-vol-22-no-1-autism-in-the-workplace.pdf#page=73 |

54 | Maxwell, J. A. (1996). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Sage Publications. |

55 | Merriam, S. B. , Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Designing your study and selecting a sample. In Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.) (pp. 73-104). . Jossey-Bass. |

56 | Miethlich B. , Oldenburg A. G. (2019, April). Employment of persons with disabilities as competitive advantage: An analysis of the competitive implications. In 33rd International Business Information Management Association Conference (IBIMA), Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020, Granada, Spain (pp. 7146-7158)., International Business Information Management Association. https://doi.org/10.33543/16002/71467158 |

57 | Miethlich, B. , Slahor, L. (2018). Employment of people with disabilities as a corporate social responsibility initiative: Necessity and variants of implementation. In Innovations in Science and Education, CBU International Conference, Prague, 21-23.03. 2019 (350-355). Prague: CBU Research Institute. |

58 | Miles, M. B. , Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.), Sage Publications. |

59 | Nicholas, D. B. , Klag, M. ((2020) ) Critical reflections on employment among autistic adults, Autism in Adulthood 2: (4), 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0006 |

60 | Ng, E. S. , Sears, G. J. ((2020) ) Walking the talk on diversity: CEO beliefs, moral values, and the implementation of workplace diversity practices, Journal of Business Ethics 164: (3), 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4051-7 |

61 | Ochrach, C. M. , Thomas, K. A. , Phillips, B. N. , Mpofu, N. , Tansey, T. N. , Castillo, S. ((2021) ) Case study on the effects of a disability inclusive mindset in a large biotechnology company, Journal of Work Applied Management 14: (1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWAM-06-2021-0045 |

62 | Phillips, B. N. , Morrison, B. , Deiches, J. , Yan, M. , Strauser, D. , Chan, F. , Kang, H. ((2016) ) Employer-driven disability services provided by a medium-sized information technology company:Aqualitative case study, Journal ofVocational Rehabilitation 45: 85–96. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-160813 |

63 | Phillips, B. N. , Tansey, T. N. , Lee, D. , Lee, B. , Chen, X. , FriefeldKesselmayer, R. , Reyes, A. , Geslak, D. S. ((2023) ) Autism initiative in the industrial sector: A case study, Rehabilitation Counselors and Educators Journal 12: (1). https://doi.org/10.52017/001c.37780 |

64 | Procknow, G. , Rocco, T. S. ((2016) ) The unheard, unseen, and often forgotten: An examination of disability in the human resource development literature, Human Resource Development Review 15: (4), 379–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484316671194 |

65 | Rashid, M. , Hodgetts, S. , Nicholas, D. ((2017) ) Building employer capacity to support meaningful employment for persons with developmental disabilities: A grounded theory study of employment support perspectives, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 47: (11), 3510–3519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3267-1 |

66 | Ross-Gordon, J. M. , Brooks, A. K. ((2004) ) Diversity in human resource development and continuing professional education: What does it mean for the workforce, clients, and professionals? Advances in Developing Human Resources 12: 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422303260418 |

67 | Rynes, S. L. , Barber, A. E. ((1990) ) Applicant attraction strategies: An organizational perspective, Academy of Management Review 15: 286–310. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1990.4308158 |

68 | Scott, M. , Jacob, A. , Hendrie, D. , Parsons, R. , Girdler, S. , Falkmer, T. , Falkmer, M. ((2017) ) Employers’ perception of the costs and the benefits of hiring individuals with autism spectrum disorder in open employment in Australia, PloS One 12: (5), e0177607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177607 |

69 | Shattuck, P. T. (2019, November 13). Drexel prof: Want to be part of a long-overdue adventure? Hire people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The Philadelphia Inquirer. https://www.inquirer.com/news/paul-shattuck-drexel-autismtransition-pathways-diane-malley-20191113.html |

70 | Stone, D. L. , Colella, A. ((1996) ) A model of factors affecting the treatment of disabled individuals in organizations, Academy of Management Review 21: (2), 352–401. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1996.9605060216 |

71 | Theodorakopoulos, N. , Budhwar, P. ((2015) ) Guest editors’ introduction: Diversity and inclusion in different work settings: Emerging patterns, challenges, and research agenda, Human Resource Management 54: (2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21715 |

72 | Thomas, K. A. , Ochrach, C. M. , Phillips, B. N. , Anderson, C. A. , Lee, B. , Lee, D. , Tansey, T. N. ((2021) ) Facilitating disability inclusive mindsets in two small business: A case study, Journal of Rehabilitation 87: (4), 12–18. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/facilitatingdisability-inclusive-mindsets-two/docview/2775780985/se-2 |

73 | Thomas, K. A. , Ochrach, C. M. , Phillips, B. N. , Tansey, T. N. ((2021) ) Social justice as an organizational identity: An inductive case study examining the role of diversity and inclusivity initiatives in corporate climate and productivity, Journal of Business Diversity 21: (4), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.33423/jbd.v21i4.4748 |

74 | Travis, M. ((2009) ) Lashing out at the ADA backlash: How the Americans with Disabilities Act benefits Americans without disabilities, Tennessee Law Review 76: (2), 311–377. |

75 | Trullen, J. , Stirpe, L. , Bonache, J. , Valverde, M. ((2016) ) The HR department’s contribution to line managers’ effective implementation of HR practices, Human Resource Management Journal 26: (4), 449–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12116 |

76 | U.S. Department of Labor. (2023). Employment Statistics—May 2023. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/odep/research-evaluation/statistics |

77 | U.S. Small Business Administration. (2012, September). Advocacy: The voice of small business in government. https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/FAQ_Sept_2012.pdf |

78 | Yang, Y. , Konrad, A. M. ((2011) ) Understanding diversity management practices: Implications of institutional theory and resource-based theory, Group&Organization Management 36: (1), 6–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601110390997 |

79 | Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage. |