Pathways to paid work for youth with severe disabilities: Perspectives on strategies for success

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Paid work during high school serves as a steppingstone to postsecondary employment for young adults with severe disabilities. Yet, youth with significant cognitive impairments rarely have the opportunity to experience paid work during high school.

OBJECTIVE:

The purpose of this study was to identify the range of facilitators that promote paid employment for youth with severe disabilities during high school.

METHODS:

We conducted individual and focus group interviews with 74 special educators, adult agency providers, school district leaders, parents of youth with severe disabilities, and local employers.

RESULTS:

Participants discussed 36 facilitators spanning nine major categories: collaboration, training and information, attitudes and mindsets, supports for youth, youth work experiences, knowledge and skill instruction, staffing, individualization, and transportation. We identified similarities and differences in the factors emphasized by each of the five stakeholder groups.

CONCLUSION:

Renewed attention should be focused on key practices and partnerships needed to facilitate community-based work experiences for youth with severe disabilities prior to graduation.

1Introduction

Employment is critical for all youth in preparing for the transition from secondary education to adulthood, as work will likely occupy the bulk of their adult lives (Fussel & Furstenburg, 2005). Early work experiences provide youth with meaningful opportunities to learn essential skills towards supporting themselves and contributing to society. For youth with intellectual disability, autism, or multiple disabilities who have significant cognitive impairments (i.e., severe disabilities), obtaining work experience prior to graduation is considered effective practice ( Mazzotti et al., 2021). When youth with severe disabilities are connected to paid work experiences during high school, they are significantly more likely to attain paid employment following their graduation ( Carter et al., 2012). Unfortunately, less than one quarter of youth with severe disabilities access these influential experiences before graduation ( Lipscomb et al., 2017), and those who do attain employment are frequently limited to entry-level positions with minimal wages ( Almalky, 2020).

Several intervention studies have focused on preparing youth with severe disabilities for work. Many of these studies have sought to improve particular vocational skills, such as work-related social skills (e.g., Baker-Ericzen et al., 2018) or specific job tasks (e.g., Alexander et al., 2013). These studies have demonstrated that individuals with severe disabilities can improve their vocational skillset when interventions target specific skills and tasks. Yet, focusing narrowly on skill instruction is likely to be insufficient for changing employment outcomes for youth with extensive support needs related to complex communication challenges, cognitive impairments, or challenging behaviors (Shattuck & Roux, 2014). Employment interventions must also address the multiple factors that extend beyond what youth can or cannot do (i.e., school, family, systems, and community factors; Awsumb et al., 2022; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al., 2020). Two intervention studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of more comprehensive approaches for connecting youth with severe disabilities to paid work experiences. Carter and colleagues (2009)evaluated a multicomponent intervention comprised of (a) community conversation events to identify new approaches to connecting youth to work, (b) community resource mapping to identify local supports, (c) summer employment planning meetings, and preparing school staff as (d) community connectors and (e) employer liaisons. This combination of strategies resulted in 66% of intervention participants obtaining summer work experiences, compared to 18% of comparison group participants. Wehman and colleagues (2019) combined the Project SEARCH intervention model (i.e., customized internship experiences with local businesses, job coaching, and adult agency supports) with individualized behavioral and autism-specific supports. This approach connected 73% of intervention group participants to paid employment, compared to 17% of comparison group participants.

Developing comprehensive interventions that connect transition-age youth (ages 14–21) with severe disabilities to paid work experiences requires solutions to persistent challenges. For example, previous studies have identified barriers related to –but not limited to –navigating collaborations between special education and disability service system providers, involvement and support from parents, reliable and accessible transportation, access to employment supports (e.g., job coaching), partnerships with local employers, and the preparation and motivation of youth (e.g., Carter et al., 2021; Trainor et al., 2008). As these barriers are likely to vary across communities, capturing the perspectives of multiple stakeholders who are part of the same community can bring much-needed insights into how prevailing barriers can be addressed locally and which strategies might be most successful. Two previous studies used qualitative approaches to engage multiple stakeholder groups in addressing employment-related challenges. Snell-Rood and colleagues (2020) held focus groups with 40 stakeholders (i.e., policymakers, parents, and teachers) to improve transition planning implementation in schools. Participants identified a variety of strategies, such as holding planning sessions prior to transition planning meetings to better prepare attendees, adopting more collaborative and accessible language, and facilitating direct and ongoing communication between “key players” in the transition planning process (e.g., individuals and their families, school staff, disability services providers, employers). Likewise, Khayatzadeh-Mahani and colleagues (2020) held focus groups with 31 stakeholders (i.e., individuals with developmental disabilities, caregivers, employers, vocational training professionals, disability services providers, policymakers, and researchers) to generate policy solutions that address employment barriers for individuals with developmental disabilities. Among the 28 stakeholder-identified solutions, the five garnering the greatest agreement addressed: (a) promoting employer training and knowledge; (b) promoting better education in high school to enable smooth transition to postsecondary education or employment; (c) changing policies around social security income; (d) increasing employment opportunities; and (e) teaching about inclusion, acceptance, and human difference in schools and workplaces.

Although these studies demonstrate the value of inviting input from key stakeholders on overcoming employment-related barriers, they did not focus specifically on ways to connect youth with severe disabilities to paid work experiences before high school graduation. The purpose of our study was to generate new ideas in this area. We conducted interviews with five different groups of stakeholders who play key roles in connecting youth with severe disabilities to paid employment— high school special educators, school district leaders, parents, employers, and adult disability agency providers. We addressed two research questions:

RQ1: What factors facilitate access to paid work for youth with severe disabilities during high school?

RQ2: To what extent do views vary within and across stakeholder groups?

2Method

2.1Participants and recruitment

We designed this study to inform the development of a school-based intervention to connect youth with severe disabilities to paid work before high school graduation. We recruited knowledgeable stakeholders from three diverse counties whose school districts agreed to participate in the subsequent intervention pilot. Each district’s enrollment ranged from nearly 30,000 to 85,000 diverse students: 27.4% to 74.9% were White, 5.2% to 40.0% were Black, 6.1% to 28.1% were Hispanic, 2.3% to 8.4% were Asian American, and 0.4% to 0.8% were other races/ethnicities. The percentage of students who were economically disadvantaged ranged from 1.0% to 38.3% across districts.

The 74 study participants included 24 parents, 17 agency providers, 15 educators, 13 employers, and five school district leaders (see Table 1 for demographics). To recruit parents, we asked special educators and local disability organizations to send invitations to parents and guardians of youth with severe disabilities. Parents had at least one youth aged 14–24 with an intellectual disability, autism (with a cognitive impairment), or multiple disabilities. The average age of their youth was 18.0 (SD = 1.9); 29% had an intellectual disability, 42% had autism with a cognitive impairment, and 29% had multiple disabilities. To recruit providers, we asked state Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) leaders to send invitations to Pre-Employment Transition Services (Pre-ETS) specialists, VR counselors, and community rehabilitation providers. We invited educators and district leaders in the three districts to participate using contact information available on our state’s online transition portal and through school leaders. Educators were required to serve transition-age youth (ages 14–21) with severe disabilities. District leaders had responsibilities related to transition or career development programming and included three deans of special education, one special education director, and one transition coordinator. Employers were recruited through existing partnerships with the three participating school districts and had experiences hiring youth with or without disabilities. We offered participants a $50 VISA gift card for participating. This study was approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board.

Table 1

Participant demographics by stakeholder group

| Variable | Parents | Special | Adult | Employers | School |

| educators | agency staff | district | |||

| leaders | |||||

| Focus groups | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Individual interviews | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Agea | 53.0 (7.0) | 40.7 (11.5) | 44.6 (8.5) | 45.5 (10.7) | 48.2 (13.9) |

| Sexb | |||||

| Female | 83.3 | 93.3 | 47.1 | 38.5 | 80.0 |

| Male | 16.7 | 6.7 | 52.9 | 61.5 | 20.0 |

| Race/ethnicityb | |||||

| White | 79.2 | 73.3 | 70.6 | 69.2 | 100 |

| Black/African American | 12.5 | 26.7 | 17.7 | 15.4 | 0.0 |

| Hispanic | 4.2 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Asian American | 4.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| American Indian, | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Alaskan, or Pacific | |||||

| Islander | |||||

| Multiple races/ethnicities | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 15.4 | 0.0 |

| Highest degreeb | |||||

| Bachelor’s degree | N/A | 6.7 | 58.8 | N/A | 0.0 |

| Master’s degree | N/A | 66.7 | 11.8 | N/A | 60.0 |

| More advanced degree | N/A | 26.7 | 17.7 | N/A | 40.0 |

| Associates degree or less | N/A | 0.0 | 11.8 | N/A | 0.0 |

| Years of work experiencea | N/A | 13.8 (8.6) | 12.5 (7.3) | N/A | 21.0 (11.0) |

Note: N/A = information not collected from stakeholder group. aMean (standard deviation). bPercentage.

2.2Procedures

We conducted sixteen focus group interviews and eight individual interviews. Nine focus groups took place in community spaces (e.g., churches, disability organizations, university rooms) within participating district areas. Due to the pandemic, we held seven focus groups and eight individual interviews through a virtual platform (Zoom). We organized each focus group around a single stakeholder group (e.g., families, educators, providers). Focus group interviews ranged from 60 to 111 min (M = 94); individual interviews lasted 46–83 min (M = 64).

The project team was comprised of three research staff, one special education faculty member, and one special education doctoral student. At least two team members attended each interview— one serving as the facilitator and the other as the notetaker. We audio recorded all interviews, and one staff member took notes on participants’ nonverbal behaviors. The facilitator asked participants to select pseudonyms, explained the study purpose, and addressed conversation etiquette (e.g., allowing everyone to speak, respecting confidentiality).

We developed a semi-structured interview protocol (available by request) based upon our team’s extensive transition experience and youth employment literature. It addressed five primary topics: (1) conceptions of meaningful work for youth with severe disabilities, (2) prevailing barriers to paid employment, (3) potential facilitators for paid employment, (4) views of community partnerships, and (5) feedback on the initial intervention model. For the current paper, the most salient interview questions were: What do you think would have to be in place to support youth with severe disabilities to have paid employment during high school? Which of these factors do you consider to be most important? Why? However, participants often addressed facilitators throughout the interviews. As participants shared their insights, we listed each facilitator they named on large post-it notes (for in person interviews) or in a shared document (for virtual interviews). We used probing questions to prompt participants to elaborate, provide additional examples, or offer additional perspectives.

2.3Data analysis

Our team used a constant-comparative approach to develop themes and codes (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Guest et al., 2013). Each interview was transcribed verbatim, checked for accuracy, and deidentified prior to analysis. After reviewing each research question and the coding process, four team members utilized soft coding to create a list of preliminary facilitators. Two team members then met and reached consensus on each of the identified soft coded facilitators. We developed a working codebook by defining each of the facilitators that emerged and creating theme categories. We developed names of themes and codes based on the transition literature (e.g., promote youth self-determination), the words of participants (e.g., focus on youth strengths), and our team’s transition expertise (e.g., provide access to natural supports).

The entire project team then met to review the working codebook until consensus was achieved. We used open coding to incorporate additional themes and categories that were not apparent during soft coding but emerged later through coding ( Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Team members then independently coded transcripts, with each transcript coded by at least two team members. Each transcript was given an initial code for pertinent units (e.g., phrases, short paragraphs), and we updated, deleted, or developed new codes as necessary. Team members coding the same transcripts met regularly to review any segments that required coders to come to consensus and make necessary codebook changes. The entire team met weekly to discuss iterative changes to the codebook until all transcripts were coded.

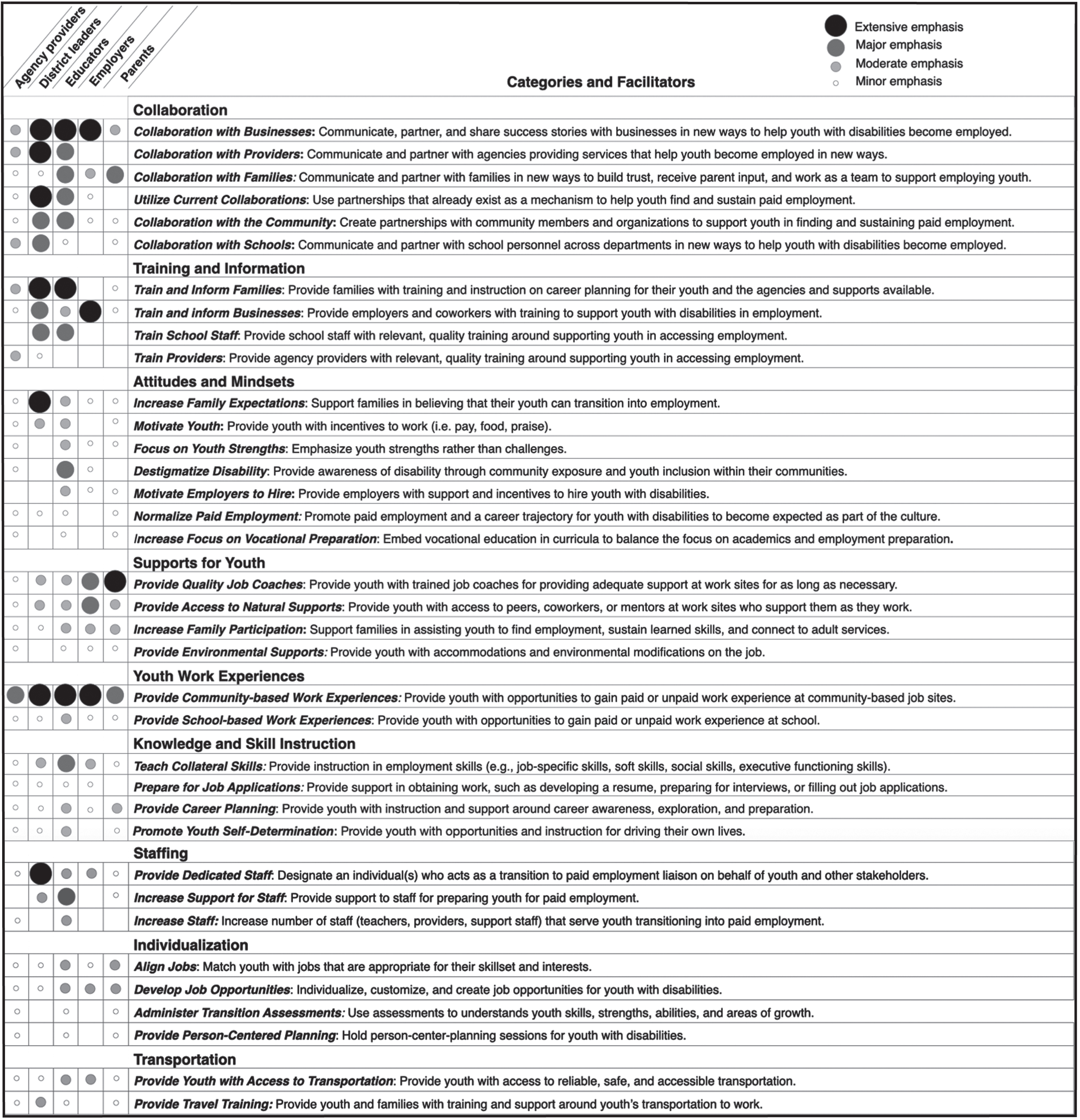

The team used Dedoose ® to manage transcripts and ensure that identified themes and codes reflected the data. We organized facilitators to paid employment by stakeholder group and determined the amount of emphasis placed on each facilitator based on (a) the proportion of references to participants in the stakeholder group and (b) the significance and attention stakeholders expressed in the coded segment. We identified five levels of emphasis: none, minor emphasis, moderate emphasis, major emphasis, and extensive emphasis (see Fig. 1). While some facilitators were mentioned and/or discussed by nearly all stakeholders (i.e., extensive emphasis), other facilitators were mentioned in passing without being expanded upon or mentioned only a handful of times (i.e., minor emphasis).

We increased the credibility and trustworthiness of our qualitative findings in several ways ( Brantlinger et al., 2005; Lincoln & Guba, 1985). We used purposive sampling to ensure all participants had in-depth knowledge of youth with severe disabilities, transition services, and/or youth employment within local communities. We maintained an audit trail throughout data collection and analysis. We adopted a team-based approach to mitigate individual biases through investigator triangulation and consensus. Within identified themes and codes, we identified disconfirming evidence, which led to the finalization, changing, or removal of necessary categories. We conducted member checking by sharing a summary of the themes and codes with each stakeholder, asking for feedback on needed changes or missing facilitators.

3Results

Participants identified a wide array of 36 facilitators that could help promote paid employment for youth with severe disabilities. Figure 1 organizes facilitators within nine categories, from most emphasis to least emphasis across the five stakeholder groups. Although some facilitators were raised within multiple stakeholder groups, others were unique to only two or three groups. For example, all stakeholders emphasized providing community-based work experiences to youth, but only agency providers and district leaders discussed training providers to help youth access jobs. In the following sections, we organize facilitators (italicized) within each category, beginning with those that were most emphasized.

Fig. 1

Facilitators to employment organized by category and emphasis.

3.1Collaboration

Participants identified six areas in which collaborations should be pursued or strengthened to promote employment. Collaboration with businesses garnered the most attention and was considered especially critical. As one parent said, “I think the number one organization or set of organizations that needs to be involved are the businesses.” Likewise, one provider asserted that they needed much “stronger connections in the community with business leaders and business owners and more time to build those relationships.” Employers affirmed this sentiment and noted their eagerness to become involved at the front end: “the earlier on you get employers involved in a long-term commitment throughout this whole thing, the better it is.” Engaging businesses was said to require marketing of the benefits of hiring youth with severe disabilities. As one employer explained, “Every company wants to do things that are good for the community, but they also want to do things that are going to benefit them.” Maintaining employer collaborations was also said to require strong communication. Employers wanted to know about the needs of the youth they hired: “it might be helpful to an employer to already know what kind of accommodations are made [for the youth] at school, so you can allow for those same accommodations to be made in the workplace.” Employers were also willing to share recommendations with schools: “I think that getting [employer] feedback would be really good and probably on a regular basis. Because they’ll probably give you more information than the student will as far as how they’re doing and what they need to work on.”

Collaboration with families was also discussed at length. Parents said they wanted to know how their youth were doing on the job (“I would need a weekly report of what he’s doing, how his day went;” “I don’t need daily phone call, but a frequent follow up”). One employer suggested that this communication schedule could be thinned over time, “Maybe if they start out, there’s weekly communication just to kind of make sure everything is going smooth with it. And then kind of release that as time goes on.” Parents wanted to know what their child was learning and how they could support these endeavors (“How are you teaching at school? So, that way, I can emulate that at home”). A few parents also said they found it helpful when they could collaborate with other families. One mother explained:

Maybe for groups of parents whose children are working to share that support system [could facilitate employment for youth]. “Hey, I’m sick today. Are you free to drive my child to work?” Or, “Hey, I can’t function today. I’m overwhelmed with life.” “I’ll help you out. I’m free.”

Participants also asserted that collaboration with providers was also needed to promote youth employment. Educators identified Pre-ETS providers as much-needed partners in this pursuit, “[Pre-ETS providers] help us make those connections and help us talk with businesses.” They also discussed how adult providers could establish the supports and continuity that youth with severe disabilities would need for long-term employment success (“making sure there’s a seamless line going from Pre-ETS to [Vocational] Rehab,” “getting a case open with vocational rehabilitation as soon as the youth is ready to leave school”). As one district leader explained:

In all this collaboration, we still have to bring in the Pre-ETS people and the VR people because ultimately these are the people that are going to be working that last year and years to come. All need to understand what’s everyone’s role . . . and focus.

Collaboration with the community was also raised as key to paid employment. A district leader described gaining community buy-in by “not only going out into the community, but also inviting them to come to us and see a little bit about what our population is like.” One educator acknowledged the importance of local supports, saying “there are so many other organizations and groups out there that are beneficial for our students that can lead to employment or support employment.” Likewise, a provider shared, “[the community] is vital because, number one, they’re a network; our teachers, our principals are all networks to things outside. So, they may not be working in the school system, but they may know people who have jobs.” Participants also emphasized the need to utilize current collaborations, or greater engagement with partners already involved in other educational endeavors. These existing collaborations took place within the school (“as a county, our teachers collaborate a lot . . . we collaborate a ton, which is helpful because we partner at our job sites”) and beyond the school (“the only way we were able to do what we do is because we have a partnership with a Pre-ETS contractor who does a lot of our stuff for us”). Collaboration with schools was a focus area for district leaders and providers. Providers anchored their discussion to the importance of partnering with schools, “you’re in there and you’re working with a teacher...[then] when you’re gone, that teacher can continue on what you’re working on.” One provider expressed their desire for educators to reach out for support: “call me up and say, I have this young person who wants to do this in the future...What should I be working on for this position? How can I help them get ready to pursue this position?” District leaders provided suggestions for collaboration within the school system: “work-based learning [staff] would like for people to have an advisory group, but it [should] be a local advisory group that would consist of your [career technical education] teachers, your work-based learning staff, your transition teachers, everybody who’s interested in getting kids connected with a business.”

3.2Training and information

Providing training and information was widely emphasized for building the capacity and commitment of various stakeholders to support the employment of youth with severe disabilities. All five stakeholder groups identified the value of providing training and information to businesses related to best practices in integrated employment. They offered suggestions for providing disability awareness training focused on “how to interact” and “positively engage” with employees with disabilities, creating “a comfortable workspace,” identifying the “type of accommodations that they may need,” determining who “they could reach out to for help,” and promoting awareness of available “resources” and “reference guides.” Parents and educators felt such efforts could “show employers possibilities” so “they’re more willing and accepting of our students.” Some employers described how previous trainings had “alleviated a lot of [their own] hesitations and fears.” They suggested that trainings incorporate “real life examples” and involve employers “who [have] the experience and [have] successfully worked with students with disabilities in the work environment that can truly speak to and answer any questions.”

Efforts to train and inform families were also said to encourage their pursuit of employment. Each stakeholder group stressed the importance of “starting early” when providing information to parents. As one parent explained, knowing “whether this is a trajectory somebody wanted to go on shouldn’t be something that they’re deciding going into their senior year.” Instead, one educator suggested that “having those resources and really thinking about [the youth’s] plan early on is the best.” A district leader explained that early conversations could “help break down some of those fears and ensure that the systems and supports are in place by the time the student is . . . set up to be in paid employment.” Participants also recommended different ways of connecting parents with needed employment information, such as school-sponsored parent transition nights that could link parents to “representatives from different programs” and provide parents a forum to “ask questions and [be] around other parents whose children are similar to theirs.” Other suggestions for information sharing included “an online portal,” “some kind of a roadmap or a directory,” a “manual,” or a “video [parents] could watch.” Relevant topics were said to include “accommodations,” “social security,” “benefits counseling,” “what to expect when your child [gets] a job,” and “how to communicate with an employer to advocate for your child.” One educator focused on supporting “parents on being, not the job coach, but being kind of that liaison between their child and the employer because . . . they’re the expert on their child.”

District leaders and educators recommended training school staff to facilitate paid employment for youth with disabilities. They described special educators as unaware of employment-related transition resources, such as managing government benefits, or unfamiliar with “the various agencies that are going to need to be involved.” Educators said they wanted to learn about real examples of successful employment partnerships “to learn exactly what work-based learning really is.” They also wanted to connect with other special educators to “talk about what other schools are doing.” One educator felt that having access to data on youths’ transition experiences and outcomes could spur change in this area:

They would need to be able to see the numbers, comparatively, of students that have received some type of pre-ETS training, or some type of employment training, compared to students that stay in a classroom and never get that type of work-based learning or anything of that nature. The outcome is what they would need to see [to realize] that the outcomes for long-term employment or for employment in general are much better for students who have had that opportunity to get that training and support that they need.

Agency providers and district leaders also recommended training agency providers on connecting youth with severe disabilities to the workplace. As with educators, providers desired training on “real-life situations” because, as one provider stated, “until you’re actually in this situation, you’re not sure how you would react.” Others suggested developing a “certification in pre-ETS” or a “job coach certification, so “businesses would be much more open knowing that the person [working with youth] really had a good handle on how to teach someone to do a job.” One agency provider suggested training focused on how to work “more hand in hand with the instructors [in] the classroom” towards the shared goal of helping youth attain paid employment.

3.3Attitudes and mindsets

Participants suggested that the views people hold about employment and youth with severe disabilities can shape the opportunities, instruction, and supports they provide. Participants urged the adoption of various attitudes or mindsets that could impact the pursuit of paid work. Increasing family expectations received attention across all five groups. Participants— including parents themselves— addressed the importance of families presuming their child can and should work in the community. Such a mindset would likely lead to their “investing” of time and energy in supporting employment through providing transportation, advocating for their child’s employment needs, teaching their child job-related skills, or accommodating their child’s work schedules. As one district leader stated, “Parents need to be invested in [youth working] before we can really do anything.” Others agreed that “getting parents on board” should happen “early” in their children’s lives. One educator described an encounter in which a grandparent caught a first glimpse of how work might be possible for her grandchild with severe disabilities:

A few years ago, we had one of our students— we do dining room assistance— and a grandmother came up to us and said, “I’m so thankful to see this young person working here, because my grandson is three, and I didn’t think he had any opportunities. And now I see this happening!” So, it gave them hope as a grandparent that felt powerless, that there might be some future that they had already maybe written off.

Parents echoed these sentiments. One mother explained that envisioning her son working was “hard for me to imagine” because of his disabilities. However, she said, “show me something my kid can do and I’m in.” Indeed, all the parents in this study agreed that they would be supportive of employment if they could see the supports that would be in place.

Many agency providers, educators, and employers spoke of destigmatizing disability by increasing community awareness of and exposure to youth with severe disabilities. Educators recommended “spreading awareness of different learning abilities” in their communities and helping businesses “accept our students and their accommodations.” Multiple participants maintained that eliminating stigmas around youth with severe disabilities could lead to normalizing paid employment so that it became “just part of our culture.” One agency provider, who is also the father of a youth with disabilities, emphasized this mindset:

I think about my son. When he left school, I just presented him with he would have a job. And because I just said, well, you’re going to have a job, then he just also said that he would have a job and went right out and found a job . . . . So, I think we just have to presume competence and always expect that the people we serve are going to be looking for jobs just like everyone else.

Several educators and agency providers raised the importance of motivating youth to value work: “I have a real job and the work I’m doing is worth making money just like everybody else.” This was said to be a challenge for some youth who lacked enthusiasm for working. Participants suggested emphasizing the value of wages (e.g., “to make the connection that, ‘if I work, I get money”’) as means to buy items of interest. An educator said,

To know that they are valued members in this society and in this community, we want to pay you for that. We want to pay you for the work, we want to pay you for your expertise. We want to pay you for the work that you do. It’s going to be a game-changer and I think it’s going to be something that’s going to be motivating for our kids to do.

A few participants, however, indicated that it may take more effort to spur motivation among youth with significant cognitive impairments. One district leader described how her teachers collaborated with employers to recognize and celebrate youths’ obtainment of jobs:

We started something called “A Signing Day,” where we really tried to get students hooked up with jobs...students would interview for the job, and if they got the job . . . we had a big banquet where the employer would come out and present them a uniform or something. Much like a college athlete when they get accepted to a college to play football.

Participants also suggested that creating a “cultural shift” in which communities expect youth with severe disabilities to work could be advanced by collectively focusing on youth strengths. Finding jobs that “fit” the strengths of youth with severe disabilities and capitalize upon their skills could help shift how communities view them. One educator described this wish:

I’ve had so many businesses say they love our students coming, and it impacts their business so much, and the people that they work with. And I think that the world needs to see that.

Indeed, one employer exclaimed that “it just gives me chills” to realize that a young man with severe disabilities he hired was “just as capable of doing the job and earning the same wage as the person next to him without that disability.”

Some educators and families insisted that additional incentives were needed to motivate employers to hire youth with severe disabilities. They suggested recognizing employers who hired youth with disabilities through “word of mouth” and “public service announcements.” Others suggested publicizing “tax breaks” as incentives for employers. Yet, no employers mentioned monetary incentives or recognition to increase their interest in hiring youth.

Agency providers, educators, and families expressed that increasing focus on vocational preparation in school curricular aims was necessary for improving the employability of youth with severe disabilities. Participants discussed the need for staff and administrators to shift focus from solely academic requirements to also helping youth develop practical skills needed for work. Examples included (a) offering an occupational-focused diploma pathway for youth, balancing core content requirements (e.g., “algebra”) with more work-based learning experiences and “functional academics” and (b) “dual-enrollment” college classes, and “internships that could lead to paid employment.” Multiple parents expressed that preparing youth for the workplace was “much more valuable” to them than their youth learning advanced academic skills in high school and felt that their youth would see more “benefit” in learning job skills than academic coursework. Some educators and agency providers, alike, discussed the need for “special segments” of time to be carved out within packed student schedules to provide Pre-ETS during the school day.

3.4Support for youth

Participants identified four areas of support that would enable youth with severe disabilities to experience success in the workplace. Increasing access to quality job coaches was discussed most extensively. Each of the five groups described a myriad of ways that job coaching could be tailored to address the individual needs of youth. Employers emphasized the importance of having a job coach who could act as “a resource if a question comes up.” One employer said this could entail “just a 10-minute conversation, if nothing else, so we each see what the issue is and that person may be able to help the employer resolve the issue.” Many parents felt a job coach ensured there was one consistent person who they and their child could trust because, as one parent explained, “the safety [of the youth] depends every day on that person.” At the same time, an educator emphasized that job coaching must fade over time:

When our students do get paid employment, they still need that person to go in and help support them for a few weeks, a few months, a few days, whatever it may be; teach them and make sure they have ways and have the skills to stand up for what they need at work, and they know what’s expected of them, and then back off and let them do their thing.

In addition to formal job coaching, each stakeholder group advocated that access to natural supports be built into work experiences. This could entail identifying supportive co-workers or establishing mentorship relationships. Parents said their child would benefit from having a coworker who “could keep an eye and maybe see that they’re getting frustrated . . . and just go, ‘Hey, what’s going on?’ or do something that they know works to calm them down.” Employers also described creative ways of incorporating natural supports, such as through an “orientation dinner” during which new employees were paired with mentoring employees or establishing a regular check-in time with each employee. Identifying natural supports was believed to decrease the reliance of youth on formal job coaching and promote greater independence. As an agency provider explained, “finding those natural supports is really, really important . . . so that when [the youth] leaves us, they are not relying on [a job coach]. They all have those natural supports in place and they develop those relationships . . . like every other employee would.”

Increasing family participation was also considered a critical support. Participants described the varied roles families could play in providing work-related support. One educator emphasized the noticeable difference this avenue of support can make in obviating barriers:

Once you get the family on board, and you tell them why this is important...when I say on board, they’re going to be supportive, they’re going to get the adult [services] that they need. Then you can get around the transportation, you can get around all the other stuff.

Parents also recognized the necessity of their own support. One mother shared, “after they graduate, parents most likely are going to be the person who’s going to keep it going.” Another mother noted that parents are “the only people who are going to be involved with them the rest of their lives.” One provider suggested that family participation in Pre-ETS will increase if families are shown the benefits from the beginning, “making [families] vested from the get go, pre-employment transition, and let them see the importance of it.” Moreover, one employer noted the impact a relationship can have on improving family participation:

I would think for me as a parent, I would feel a little bit more comfortable and secure putting my child into an environment if I had the opportunity to meet those individuals that they were going to be working with and interacting with, whether it’s a manager, general manager or HR director.

Environmental supports, such as workplace accommodations and modifications, could also be instrumental for youth with severe disabilities. Agency providers and parents both identified assistive technology that could assist youth, such as using smartphone applications for work task “reminders or checklists.” Employers expressed their willingness to make accommodations based on youth’s needs by addressing “any kind of restrictions that they might have in certain areas,” “focusing on their skillset and making sure that the company knows that they are able to do that work,” and “accommodating them in any way, within reason.”

3.5Youth work experiences

The value of hands-on experiences was emphasized by all stakeholder groups as a pathway to employment. One recommended avenue involved providing school-based work experiences. Establishing on-campus experiences was shared as a way to prepare youth with disabilities for subsequent employment in the community. For example, one district leader described how schools used work simulation labs to teach job-related skills in the classroom. Likewise, an educator described how youth learned to “order supplies, check inventory, and take orders” while working at the school’s café. For parents, these experiences allowed their children to “work on tasks in a controlled environment” before they eventually “shifted to an unfamiliar environment.” One parent explained:

I think it’s really important, especially if there’s a way for those 19 to 22-year-olds to be able to fail in a controlled situation. And not only be coached about the performance issues related to the job, but the hard issues related to getting through it. I mean all of us probably went through that early in our careers. We had those moments where we face planted. And, there was the, okay, we got to get back on the horse and do that report again, or do whatever again . . . if those kids are given a chance to fail in a controlled environment, I think they’ll be better set for actual employment after transition.

All stakeholder groups heavily recommended providing community-based work experiences. Involvement in authentic workplaces was said to help youth learn the “soft skills of having a job” while “socially interacting with bosses and co-workers.” An employer described how he saw youths’ “social skills develop and confidence build” within a community business. An agency provider echoed this value of hands-on experiences in the community:

Just having the hands-on skills is just so important. And seeing that the progress that my students have made . . . that was just so evident and it’s really exciting and fun to see just them working together. We came up to these job sites and they actually get to physically do the work and really train alongside other employees and it’s just, they learn so much faster that way.

Several district leaders described how community-based experiences could support the generalization of new skills. For example, one leader shared that “a student may perform one way in the school building with staff they are familiar with, in an environment they are familiar with. And then things feel very different when you are exposed to the real thing.”

3.6Knowledge and skill instruction

Participants identified several areas in which work-related instruction should be provided to youth with severe disabilities. Many recommended providing career planning focused on helping youth engage in career awareness and exploration. One agency provider described the questions every youth should be ready to answer:

What are different careers? What are they interested in? What does it take to get the job you want? Then, what are some jobs you can get along the way to get to that maybe “fancy” job you want to do some day?

Stakeholders also recommended providing employment instruction, such as teaching collateral skills. Examples included “soft” skills, executive functioning skills, and social skills that have relevance across career fields. Participants suggested teaching youth to use eye contact in the workplace, follow workplace rules (e.g., cell phone etiquette, arriving to work on time, maintaining a professional appearance), get along with coworkers and supervisors, and persist through difficult tasks. Recognizing that becoming “a good value employee” does not “happen naturally,” stakeholders suggested instruction begin as early as possible. Moreover, several participants spoke of the importance of supporting youth in preparing for job applications by developing a resume, practicing interview skills, completing applications, developing computer skills, or obtaining necessary identification documents. A few participants suggested that career technical education (CTE) or science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) courses could serve as contexts for teaching these skills. However, an educator noted that gaining access to these courses was difficult for youth with severe disabilities and required considerable advocacy.

With the exception of employers, all stakeholder groups recommended promoting youth self-determination through ongoing instruction and opportunities for practice. A few educators discussed teaching youth to set goals and monitor progress; yet, most examples focused on equipping youth to identify and self-advocate for needed supports. One educator framed teaching self-advocacy skills as a primary focus of her work with youth:

Regardless of what happens in the community . . . if I have equipped you with what you need to go and advocate for you . . . then you know “I need to be my own voice or find someone who can be a voice for me when my voice doesn’t seem to be heard.”

3.7Staffing

The need for new staffing models to implement many of the previously mentioned strategies was also addressed. All stakeholder groups recommended providing dedicated staff who could serve as a transition services liaison for youth, their families, educators, agencies, businesses, and other stakeholders in the community. One educator identified a need for a “designated person at the school system” who “identified businesses they thought would be disability friendly.” Having a point person freed up other educators to focus on day-to-day teaching. Likewise, an employer recommended having “a dedicated point of contact” that employers “can turn to if we’re having any kind of issues.” Parents also saw value in having a single person in charge of “coordinating all of the resources” and “grabbing research from other areas to see if it works for us.” For district leaders, having a designated “navigator to sit down with families” could keep families from feeling “overwhelmed or buried in all the resources.” Finally, agency providers echoed the need for “one go-to person” to ensure strong collaboration.

Participants also raised the need to increase staff who serve youth in a transition role (i.e., teachers, providers, support staff). An agency provider highlighted how “having support staff” allows for participation in “IEP meetings, job fairs, and resource fairs.” Similarly, an educator punctuated the need for more staff to support youth in community work experiences:

In my classroom, I have 10 [students]. I have two assistants. But in terms of work-based learning, when you have 30 kids who are going out to work-based learning, six adults doesn’t cut it especially when you have [youth with more significant support needs] who do need more of that support as well. And if you’re wanting to get them into more advanced positions, that’s something that we’ll definitely have to look at is increasing those numbers and saying how important it is for there to be more staff.

Finally, educators, district leaders, and parents all advocated for increasing support for staff around employment. This could involve ensuring “major support from the administration” is available or that educators can partner with “Pre-ETS in every school.” Educators reported, “I think you have to have the support of the admin team as well. I think you really have to have your principal on board and backing [paid employment during high school] in order to make it successful.” Educators also discussed the need to increase visibility of special educators in leadership roles to better support youth seeking paid employment:

We don’t have a lot of presence from our leaders in our district because there’s so many schools, so maybe if there was more funding, we could have that, so that way those students can get as much support as they can. Right now, they’re just depending on their teacher, but a lot of times, we don’t really have everything, so if [special education] has more presence as far as leadership goes in the school, then maybe I think we would have more resources and more support.

3.8Individualization

Recognizing the importance of individualization in the pathway to employment, participants discussed ways in which transition experiences should be personalized for each individual youth. One area involved developing job opportunities. Some participants expressed concern with schools or agencies “just taking the whole group [of youth]” to workplaces for work-based learning. Instead, they recommended “trying to figure out what works for each child.” The input of parents was more varied. For example, several parents pointed to the growing number of “special needs businesses that are popping up” to employ individuals with disabilities. One of these mothers maintained that “my child would be perfectly fine in a special needs community for the rest of her life.” Other parents emphasized inclusive work settings:

Special needs coffee shops...I kind of think are awesome because you’ve got your staff and the community’s expectations...they know going in that this is run by people with special needs. But it keeps them out of the other workplaces. So, I don’t know. We need a balance.

Agency providers, educators, families, and district leaders all suggested aligning jobs with the skillsets and interests of each youth. Several providers highlighted the importance of supporting youth in “identifying long-term employment goals” and utilizing backwards planning to determine “what are the education requirements, where are we starting at and where are we trying to get to?” They discussed the need to consider youths’ “strengths,” “abilities,” “choice,” “support needs,” and the “barriers there are going to be to meeting these goals” when developing jobs for youth. Several educators agreed that “working in food service for someone who’s really passionate about physical fitness doesn’t make a lot of sense.” One educator spoke of the benefits of matching youth with jobs that reflect a healthy balance of interest and challenge:

I love, love placing students at job sites where they’re actually interested and where they don’t really know what they’re doing quite yet. Because then you do get to see the growth and you know they’re continuing to learn.

Some parents pointed out that this task is “the toughest part” of the process. However, finding jobs that are “meeting the kid’s heart...so there is some type of pleasure” remained a priority.

To develop jobs aligned to the interests and preferences of youth, participants recommended administering transition assessments that identify existing skills, strengths, and areas of growth. They agreed that youth should participate in career assessments early and often to identify jobs of interest. Strengths-based assessments were considered far more valuable than traditional assessments focused on academic and behavioral domains. Yet, multiple educators and providers lamented the limited availability of such assessments for youth with severe disabilities. Some participants also proposed providing person-centered planning meetings that ensured youth “have control and have some say in what’s going on.” One educator suggested holding an initial person-centered planning meeting when you are in “late middle school,” followed by an additional meeting in 10th or 11th grade because youth tend to “like different stuff” as they get older. Yet, multiple stakeholders voiced a desire for more support in this area. One parent explained, “I feel there are some great services and support around [this] area, but I feel like not everybody knows about them.” An agency provider agreed, “I really don’t know much about person-centered planning” but “we would love to have some help in that area.”

3.9Transportation

Lastly, all stakeholder groups acknowledged that providing youth with access to transportation is a requisite to successful employment. Youth were said to need a variety of safe and reliable transportation options. As one employer explained, “if we want to hire this person –whether it be the parents committing or a transportation on demand, public transportation system, a bus system –that would help as well as far as getting students employed.” An educator also affirmed the need for more inclusive and accessible transportation for youth with severe disabilities:

Those students definitely will need transportation and also accommodations made where there’s pictures and visual print that they can see. Because some of my students have visual disparities as well. So, like I said, a lot of the transportation is not conducive to students that have special needs. There’s some where there’s pictures, and they have guides. But if they can’t read, who’s going to read it to them? There’s no audio or anything like that that can help them, so I just feel like we have to do better.

Participants also acknowledged the importance of providing travel training and support to youth and families. They recognized that each youth would have unique needs in this area. and one agency provider acknowledged that providing travel training could “be its own course or lesson depending on the student’s needs.” One district leader noted that travel training needed to occur “before securing the job, so that you know that they can travel to and from [the job] safely.” An employer emphasized the importance of having transportation in place before getting out into employment to “have that foundation set.” Most stakeholders in the parent group discussed how travel training taught their child that “safety [is] not just about the workplace”.

4Discussion

In this qualitative study, we examined how various stakeholders (i.e. parents, educators, district leaders, providers, and employers) viewed key factors needed to facilitate early work experiences for youth with severe disabilities. Stakeholders created a broad list of factors that may address a wide spectrum of barriers currently encountered by youth with severe disabilities in connecting to paid employment.

Promoting early work experiences for youth with severe disabilities requires a comprehensive approach. Previous studies have identified important practices and experiences that can increase the likelihood of youth with disabilities working, such as community-based internships, school-business partnerships, and staff training for meeting the disability-related needs of youth (e.g., Carter et al., 2009; Wehman et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the wide spectrum of 36 facilitators identified across nine different categories in this study illustrates the necessity of a broader support paradigm that addresses (a) instruction, experiences, and supports for youth and (b) the capacity of those who support them. Stakeholders placed extensive emphasis on items across all themes, suggesting that a great deal of concurrent efforts must be made if paid employment is to happen for youth who have multifaceted needs and require extensive supports. The wide-ranging approach to intervention that emerged from our conversations is not altogether surprising. Yet, schools may find it challenging to address all these areas concurrently in the absence of guidance.

Implementing such a comprehensive approach requires coordination and cooperation. In this study, collaboration emerged among the most emphasized areas across stakeholder groups. Participants repeatedly asserted the importance of developing strong and sustained partnerships among schools, employers, agency providers, families, and their communities. Such collaboration is necessary to address the breadth of essential areas and aligns with findings from other studies addressing employment outcomes for individuals with severe disabilities (e.g., Carter et al., 2009; Carter et al., 2016). Nonetheless, the variations across stakeholder groups in this study could be readily addressed through collaboration. For example, educators and district leaders placed extensive emphasis on providing families with training and information on career planning, while employers stressed the need for businesses to receive training and information on supporting employees with disabilities. Collaboration amongst these groups can lead to far-reaching plans of action that address each of these important facilitators.

Several facilitators emphasized by stakeholders focused on the opportunities and assistance youth with severe disabilities would need to access work experiences. For example, all stakeholder groups placed major or extensive emphasis on providing youth with community-based work experiences. Likewise, families and employers emphasized the need for youth to access quality job coaches, and employers highlighted the importance of natural supports in the workplace. This emphasis is consistent with prevailing support paradigms that recognizes that transition outcomes do not depend wholly on the skills and knowledge that youth currently possess (Shattuck & Roux, 2014). Instead, youth with severe disabilities must be provided with a collection of individualized supports that help bridge distance between their strengths and the demands of their preferred workplace. At the same time, participants emphasized the importance of providing youth with strong instruction in the areas of career planning, job skills, and self-determination. Nonetheless, the facilitators emphasized by stakeholders call for schools and agencies to extend their efforts beyond merely increasing youth skills and towards building capacity for educators, families, and employers to provide youth with the experiences and supports needed to work for pay (e.g., training families, employers, and school staff; providing dedicated staff; utilizing current collaborations as a mechanism to connect youth to work).

Mindsets may be among the most challenging areas to address, but they are likely pre-requisites of changes to practices and policies. District leaders emphasized the importance of increasing family expectations for youth to work, while educators discussed the importance of destigmatizing disability within their communities. Although stakeholders discussed the challenges in changing these mindsets, doing so may be imperative for implementing the other areas of facilitators emphasized. For example, expectations and attitudes related to work can have a strong influence on whether youth, parents, professionals, and employers will pursue or support integrated employment (Carter et al., 2012; Wehman et al., 2015). Indeed, beliefs about youth with severe disabilities and their employability are likely to impact whether any of the practices or partnerships described are even pursued. Training and information for families, businesses, school staff, and providers that addresses the importance of employment for youth during high school may provide one pathway for improving attitudes and raising expectations.

4.1Implications for practice

Our findings have several implications for practice. Participants recommended multiple partnerships that schools should pursue when connecting youth with severe disabilities to paid work. Fortunately, while youth skills and stakeholder mindsets may be more complicated for schools and providers to change quickly, several strategies can be employed for intentionally developing and deepening partnerships that can result in increased employment opportunities and connections. Establishing a community-level transition team is one avenue through which new collaborations can be forged (e.g., Flowers et al., 2018). Moreover, designating educators, providers, or others as information liaisons between schools, agencies, and employers (e.g., Carter et al., 2009) may facilitate collaboration between these groups and result in the community-based work experiences that all stakeholder groups in this study agreed were important. These individuals should also provide families with access to digestible information and resources for supporting efforts to connect youth to work.

Nonetheless, every community is distinct in the opportunities available and challenges that are to be tackled for youth with disabilities to access employment. Therefore, approaches that consider the unique characteristics of school systems and communities are warranted. School districts could convene representatives of each of the stakeholder groups involved in this study to ask for their input on any changes needed locally. Additional stakeholder groups to consider could include CTE teachers, school counselors, and representatives of job programs (e.g., American Jobs Centers, small business associations, local chambers of commerce). Likewise, districts could host their own “community conversation” events as way of inviting the input of additional community members (e.g., Schutz et al., 2021).

4.2Limitations and implications for future research

Limitations of this study suggest areas for future research. We limited our recruitment to three school districts with varied makeups (e.g., demographics, disability status, size); however, the results of this study cannot be generalized to all of the school districts across the country. The facilitators needed or prioritized in other locales may vary from those voiced by our sample. Future studies should focus on rural districts and those that serve larger proportions of youth from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Moreover, although we sought the perspectives of parents and professionals, we did not invite the input of youth with severe disabilities. Identifying what youth themselves would find most helpful in their pursuit of employment could enrich our understanding of how best to support this transition. While a handful of studies have qualitatively captured the perspectives of young people with IDD (e.g., Griffin et al., 2019), future researchers should identify ways of soliciting the input of transitioning youth with severe disabilities –including those with complex communication challenges –around their own views and experiences related to work.

Lastly, our study examined perspectives, rather than actual practices. Although numerous recommendations were made for promoting early work experiences, the extent to which those recommendations had been tried or found successful varied across the participants. Although many of the facilitators aligned with research-supported practices and predictors (Mazzotti et al., 2021), others have yet to be studied formally (e.g., establishing a local network of families with youth working, bringing employers into schools to work with students with severe disabilities). Future studies should examine those facilitators that have been unaddressed in the literature.

5Conclusion

Paid work experiences during high school can foster employment skills, provide resume-building experiences, and facilitate linkages to employers that increase the likelihood that youth with severe disabilities will become employed following high school. This study highlights the constellation of factors related to youth themselves and the stakeholders who support them in accessing paid jobs prior to graduation. While several of the individual facilitators raised in this study are not new, addressing each of these areas will require collective efforts across stakeholder groups. This study should prompt researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to comprehensively address each of these factors in feasible, sustainable ways.

Acknowledgements

None to report.

Informed consent

Participants completed and submitted a paper or online consent form.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest reported.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University IRB (#192469).

Funding

Support for this research was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (#90RTEM0002), a center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS); and with support from the Vocational Rehabilitation Technical Assistance Center for Quality Employment (Grant Number: H264K200003) from the U.S. Department of Education. However, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal government.

References

1 | Alexander, J. L. , Ayres, K. M. , Smith, K. A. , Shepley, S. B. , Mataras, T. K. ((2013) ). Using video modeling on an iPad to teach generalized matching on a sorting mail task to adolescents with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7: (11), 1346–1357. https://doi.org/10.1016/jrasd.2013.07.021 |

2 | Almalky, H. A. ((2020) ). Employment outcomes for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a literature review. Children and Youth Services Review, 109: , 104656. |

3 | Awsumb,J., Schutz,M., Carter,E., Schwartzman,B., Burgess,L., & Lounds Taylor,J. ((2022) ). Pursuing paid employment for youth with severe disabilities: Multiple perspectives on pressing challenges. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 47: (1), 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/15407969221075629. |

4 | Baker-Ericzén, M. J. , Fitch, M. A. , Kinnear, M. , Jenkins, M. M. , Twamley, E. W. , Smith, L. , Montano, G. , Feder, J. , Crooke, P. J. , Winner, M. G. , Leon, J. ((2018) ). Development of the supported employment, comprehensive cognitive enhancement, and social skills program for adults on the autism: Results of initial study. Autism, 22: (1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317724294 |

5 | Brantlinger, E. , Jimenez, R. , Klingner, J. , Pugach, M. , Richardson, V. ((2005) ). Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional Children, 71: (2), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290507100205 |

6 | Bush, K. L. , Tassé, M. J. ((2017) ). Employment and choice-making for adults with intellectual disability, autism, and Down syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 65: (1), 23–34 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.04.004 |

7 | Carter, E. W. , Austin, D. , Trainor, A. A. ((2012) ). Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23: (1), 50–63 https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207311414680 |

8 | Carter, E. W. , Trainor, A. A. , Ditchman, N. , Swedeen, B. , Owens, L. ((2009) ). Evaluation of a multi-component intervention package to increase summer work experiences for transition-age youth with severe disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 34: , 1–12 https://doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.34.2.1 |

9 | Carter, E. W. , Blustein, C. L. , Bumble, J. L. , Harvey, S. , Henderson, L. , McMillan, E. ((2016) ). Engaging communities in identifying local strategies for expanding integrated employment during and after high school. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121: (5), 398–418 https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-121.5.398 |

10 | Chan, W. , Smith, L. E. , Hong, J. , Greenberg, J. S. , Lounds Taylor J. , Mailick, M. R. ((2018) ). Factors associated with sustained community employment among adults with autism and co-occurring intellectual disability. Autism, 22: (7), 794–803 https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362361317703760 |

11 | Corbin, J. , Strauss, A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed). Sage. |

12 | Flowers, C. , Test, D. , Povenmire-Kirk, T. C. ((2017) ). A demonstration model of interagency collaboration for students with disabilities: A multilevel approach. The Journal of Special Education, 51: (4), 211–221 https://doi.org/10.10.1177%2F0022466917720764 |

13 | Fussell, E. , Furstenberg, F. F. ((2005) ) The transition to adulthood during the twentieth century. In R. A. Settersten, F. F. Furstenberg,&R. G. Rumbaut (Eds.), On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy (pp. 29–75). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. |

14 | Griffin, M. M. , Fisher, M. H. , Lane, L. A. , Morin, L. ((2019) ). In their own words: Perceptions and experiences of bullying among individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 57: (1), 66–74 https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-57.1.66. |

15 | Guest, G. , Namey, E. E. , Mitchell, M. L. ((2013) ) Collecting qualitative data: A field manual for applied research. Sage. |

16 | Khayatzadeh-Mahani, A. , Wittevrongel, K. , Nicholas, D. B. , Zwicker, J. D. ((2020) ). Prioritizing barriers and solutions to improve employment for persons with developmental disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42: (19), 2696–2706 https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1570356 |

17 | Lincoln, Y. S. , Guba, E. G. ((1985) ) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage. |

18 | Lipscomb, S. , Haimson, J. , Liu, A. Y. , Burghardt, J. , Johnson, D. R. , Thurlow, M. L. ((2017) ) Preparing for life after high school: The characteristics and experiences of youth in special education (Vol. 2). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. |

19 | Mazzotti, V. L. , Rowe, D. A. , Kwiatek, S. , Voggt, A. , Chang, W.-H. , Fowler, C. H. , Poppen, M. , Sinclair, J. , Test, D. W. ((2021) ). Secondary transition predictors of postschool success: An update to the research base. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 44: (1), 47–64 https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143420959793 |

20 | Schutz,M. A., Carter,E. W., Maves,E. M., Gajjar,S. A., & Mcmillan,E. D. ((2021) ). Examining school-community transition partnerships using community conversations. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 55: (2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-211152 |

21 | Shattuck, P. T. , Roux, A. M. ((2015) ). Commentary on employment supports research. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 19: (2), 246–247 https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313518996 |

22 | Sinclair, J. , Poteat, V. P. ((2020) ). Aspirational differences between students with and without IEPs: Grades earned matter. Remedial and Special Education, 41: (1), 40–49 https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0741932518795475 |

23 | Snell-Rood, C. , Ruble, L. , Kleinert, H. , McGrew, J. H. , Adams, M. , Rodgers, A. , Odom, J. , Hang Wong W. , Yu, Y. ((2020) ). Stakeholder perspectives on transition planning, implementation, and outcomes for students with autism disorder. Autism, 24: (5), 1164–1176https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362361319894827 |

24 | Trainor, A. A. , Carter, E. W. , Swedeen, B. , Owens, L. , Cole, O. , Smith, S. ((2008) ). Perspectives of adolescents with disabilities on summer employment and community experiences. The Journal of Special Education, 45: (3), 157–170 https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022466909359424 |

25 | Wehman, P. , Schall, C. , McDonough, J. , Sima, A. , Brooke, A. , Ham, W. , Whittenburg, H. , Brooke, V. , Avellone, L. , Riehle, E. ((2019) ). Competitive employment for transition-aged youth with significant impact from autism: A multi-site randomized clinical trial. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 50: (6) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03940-2 |

26 | Wehman, P. , Sima, A. P. , Ketchum, J. , West, M. D. , Chan, F. , Luecking, R. ((2015) ). Predictors of successful transition from school to employment for youth with disabilities. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 25: (2), 232–334 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9541-6 |