Tracking metrics that matter for scaling up employment outcomes

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Supporting employment consultants in their work with job seekers is critical for increasing the employment outcomes of people with disabilities.

OBJECTIVE:

To better understand how to leverage data for supporting employment consultants, including what metrics to track, what to do with the data, and what can be improved.

METHODS:

A panel of three directors of employment programs addressed these questions as part of the Association of People Supporting Employment First (APSE) 2020 conference.

RESULTS:

Most employment service providers collect data for billing and compliance reporting. Innovative providers leverage data for quality improvement.

CONCLUSIONS:

Tracking metrics designed specifically for monitoring the implementation of effective employment supports is key for leveraging data for continuous quality improvement and thus improving job seekers’ employment outcomes.

1Introduction

Despite decades of system change initiatives for increasing employment of people with disabilities, the majority of this population remains unemployed or earn wages that are considered inadequate for achieving economic self-sufficiency (Wehman et al., 2018; Winsor et al., 2019). Clearly, if the employment outcomes of this population are to increase, new strategies must be identified (Harkin, 2012; Mank, 2016; NIDILRR, 2019). One intervention that has not received much attention yet is to leverage data and technology to maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of employment support services (Graham et al., 2013; Migliore et al., 2020). This approach would reflect a national trend of federal, state, and local agencies across sectors who are increasingly investing in technology that uses data to transform their businesses and achieve better outcomes (Allard et al., 2018; Results for America, 2019; Weigensberg et al., 2012). Employment service providers who assist job seekers with disabilities could benefit from technology to track the implementation of effective employment supports including, for example, the APSE Universal Employment Competencies (APSE, 2020). Providers could leverage the data to reflect on the implementation of these national standards, set goals, and take actions as part of a continuous quality improvement cycle aimed at increasing job seekers’ employment outcomes.

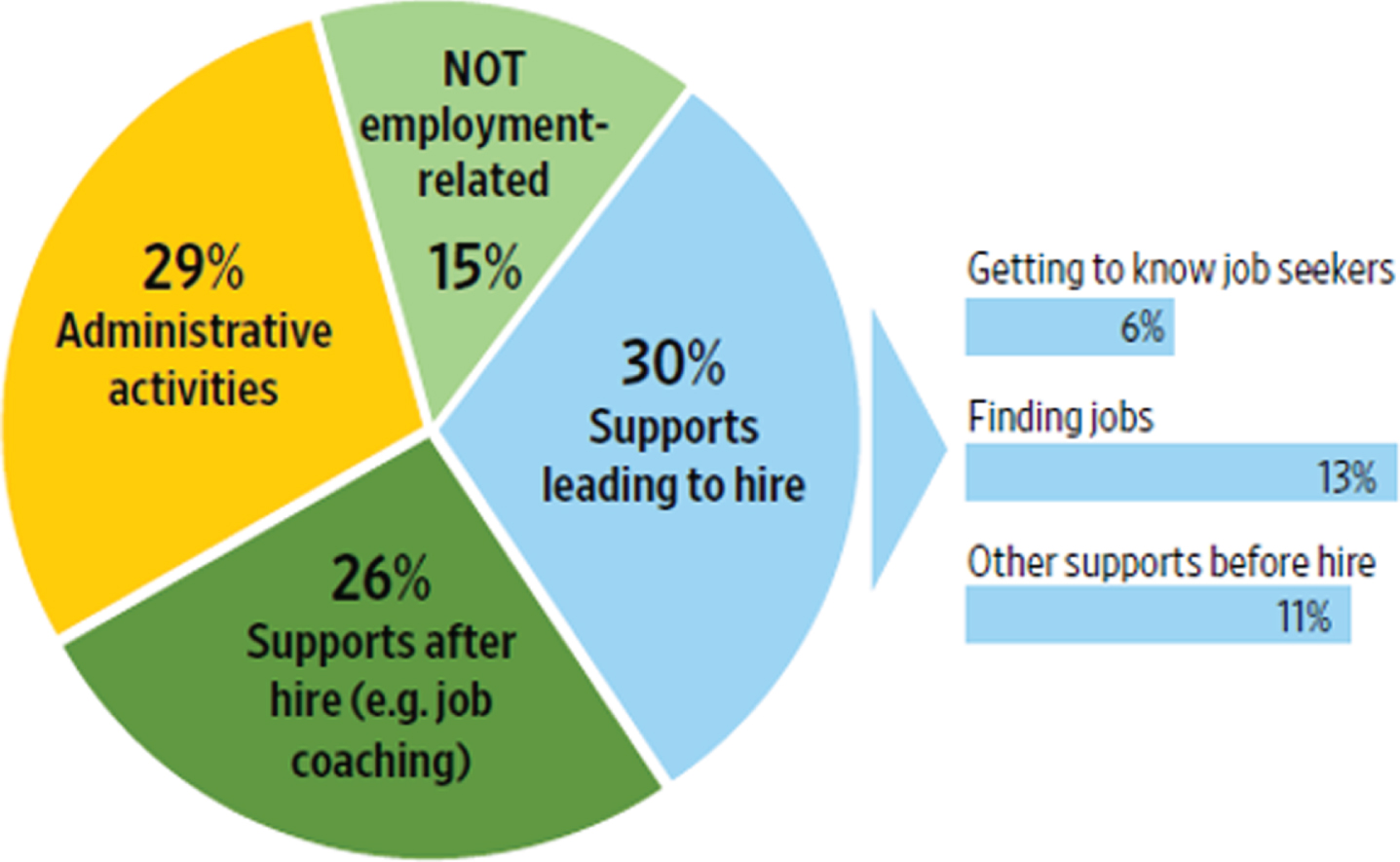

Research shows a need to improve the implementation of national standards of effective employment supports. For example, a recent study found that employment consultants invest on average only about 30% of their time delivering services that lead to hire (i.e., 2 hours and 24 minutes per day) including getting to know job seekers, finding jobs, and other supports before hire (Fig. 1; Butterworth et al., 2020; Migliore et al., 2018).

Fig. 1

Distribution of employment consultants’ time (N = 61 employment consultants). Adapted from Migliore et al., 2018.

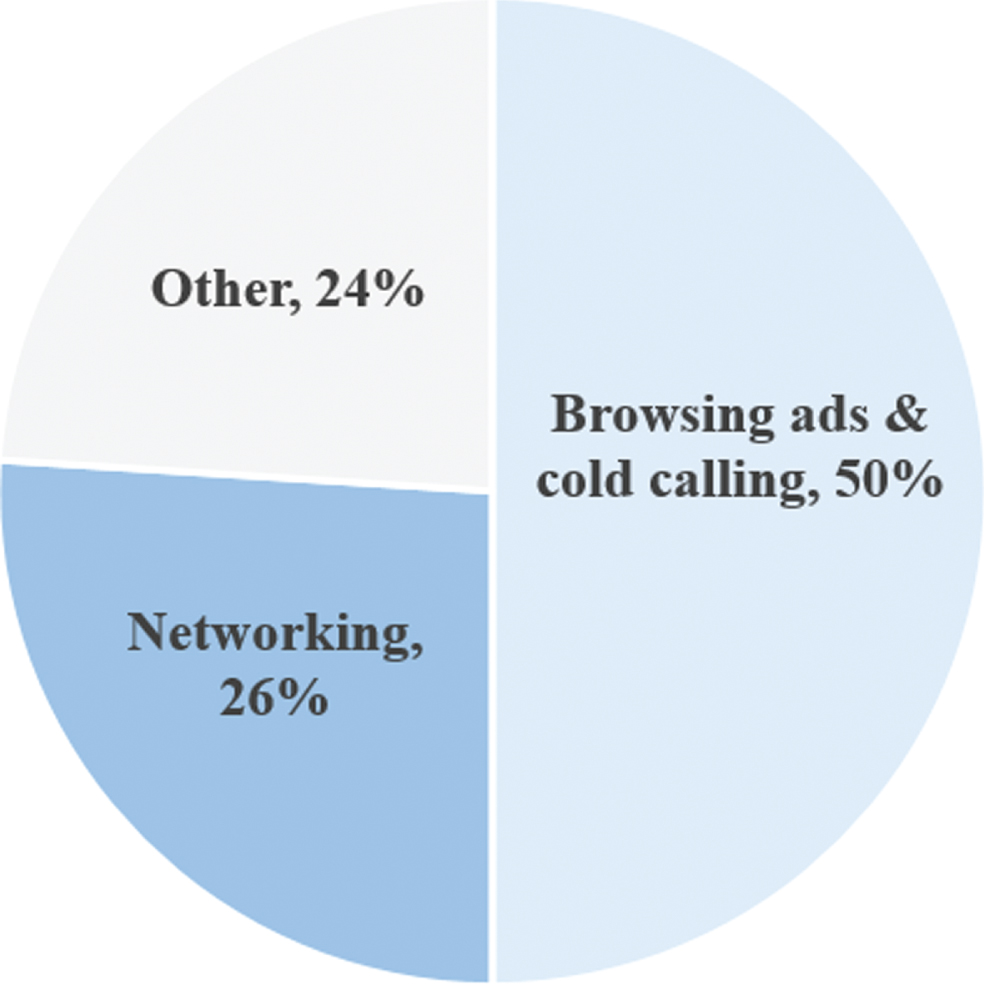

Moreover, research shows that about 50% of the time spent for finding jobs was invested in browsing classified ads or cold calling— not recommended practices— rather than networking, which is a recommended practice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Distribution of time for finding jobs (N = 61 employment consultants). Adapted from Migliore & Lengerman, 2019.

These findings illustrate the value of tracking support activities delivered to job seekers as a first step for reflecting on the extent to which these supports align with the standards of effective employment supports, and setting goals for improvement. A participant in the study stated:

I find that it [the data] causes me to pause for a moment and reflect on how I am spending my time, energy and resources.

Fortunately, the technology for leveraging data is increasingly more accessible thanks to recent innovation in cloud-based computing power and access to the Internet via mobile devices (Schmit & Rosenberg, 2017; Valacich & Schneider, 2018). As a result, employment service providers are increasingly adopting software technology to track and process data about their services and outcomes. However, providers tend to use this technology for automating billing and compliance reporting— a legitimate need for ensuring financial sustainability— but not necessarily for tracking the implementation of effective employment supports as part of continuous quality improvement (Attaliades, 2019; Olshansky, 2019).

The purpose of this article is to bring the attention of employment providers and other key stakeholders to the importance of leveraging technology and data for tracking the implementation of effective employment supports as a first step toward continuous quality improvement aimed at increasing job seekers’ employment outcomes. This article is based on a panel presentation at the 2020 Association of People Supporting Employment First (APSE) conference involving three directors of innovative employment programs (Butterworth et al., 2020). This paper addresses these two questions:

1. What metrics do employment providers track and why?

2. What could be improved?

2What metrics do employment providers track and why?

The metrics described during the panel presentation could be characterized as either (a) addressing primarily billing and compliance reporting, or (b) designed primarily for promoting quality improvement.

2.1Billing and compliance reporting

Metrics tracked for billing are designed to capture either the amount of services delivered or the achievement of specific milestones. In both cases the primary purpose is to bill a funding agency and receive a payment for the services provided. For example, providers may track billable hours to document the delivery of authorized services described as broad categories, such as assessment, job development, or job coaching. This is typical for services funded through Medicaid waivers. In the case of outcome-based funding systems (e.g. Vocational Rehabilitation funding), providers track the achievement of milestones, rather than the amount of time invested in service delivery. Typical milestones include submitting an individualized plan of employment, the hire date, or achieving job stabilization after a certain number of days on the job. Providers track and use these data to bill their funding agencies for reimbursement, thus ensuring financial sustainability of their operations.

In addition to tracking billing hours or milestones, employment providers track qualitative data in the form of case notes as part of compliance. These notes consist of text that qualitatively describes the nature of the services delivered and any other useful information, including successes, challenges, or incidents while supporting a person. Supervisors use these notes to evaluate the progression of services, evaluate team members who share a role in supporting the same person, and for auditing and compliance purposes. Case notes vary in length and level of detail depending on the providers’ guidelines or the employment consultant’s writing skills.

Finally, the panelists talked about tracking descriptive information, including demographic information at intake, the number of job seekers who gain employment annually, earnings, work hours of job seekers who are hired, and employers’ characteristics.

2.2Quality improvement

This group of metrics aims more specifically to gather information to use for improving quality of services, but they are not consistently tracked. For example, while data for billing purposes may track how much time is invested in a job search, metrics designed for quality improvement would track whether networking— a recommended practice for job searching— was implemented versus cold calling— not an effective practice. Providers can then use the data to provide feedback and support to employment consultants to improve consistent implementation of recommended support practices. An attendee stated:

I really think providing employment staff feedback is essential. Hopefully we can add this piece (Attendee).

Data can also be used to tell stories that may help job seekers or their families make informed decisions around employment. For example, a panelist emphasized the importance of data that document the advantages of income from employment versus disability benefits:

we have lots of stories we can share about what we’ve physically seen or what we’ve heard about, but we haven’t found ... the right data ... as a way to advocate and to really kind of demonstrate those targets (Panelist).

Providers can also use data to inspire and boost employment consultants’ motivation. A panelist talked about employment consultants at her organization who set annual goals, including the number of job seekers who get jobs, time from intake to hire, hourly earnings, and work hours. At their monthly meetings, the employment consultants compare their statistics, discuss the differences, and brainstorm ideas about how to improve.

Those teams ... they’re looking at those statistics that come right out of our database. And so we can have fun with it and say, Oh, well, you know, this team has higher outcomes. What are they doing?(A panelist).

The panelists also talked about the potential of comparing data across states so providers can learn from the differences. For example, a panelist shared that job seekers in Connecticut got jobs that entailed an average of 30 hours per week. In contrast, job seekers in Massachusetts— served by the same provider— tended to get jobs that entailed only 17 hours per week. The provider reflected on the differences across states and concluded that different state policies could have different impacts on disability benefits. As a result, the provider hired an in-house disability benefits counselor to better leverage work incentives and support job seekers to maximize their public benefits and still retain their earned income.

3What could be improved?

A key recommendation that emerged from the panel was to reach consensus on standard metrics. Currently, each employment provider is required to track a variety of different metrics to address the different billing requirements from different funding sources, including Medicaid, Vocational Rehabilitation, and other federal, state, or county agencies. The fact that each funding agency may change their data requests over time adds complexity. One panelist highlighted that the constant need to tweak the data collection protocols, software, and databases to meet the needs of their varied funding agencies is a major cause of unnecessary disruption. Every change requires that employment consultants and managers learn new data fields and data collection protocols, and handle increasingly complex databases. Agreeing on a set of standard metrics would make data tracking easier and also more accurate. Moreover, standard metrics would allow for better use of the data, including data comparison across employment providers and states, which could provide additional opportunities to reflect on quality improvement and outcomes.

In regard to outcome measures, the panelists highlighted the importance of tracking metrics currently not often measured, including time from intake to hire, job satisfaction after hire, changes in earnings overtime, changes in work hours overtime, job retention, and career advancement. A panelist highlighted the need of tracking the impact of employment also on other areas of the job seeker’s personal life, such as social inclusion, health and well-being, and independence from social security benefits. This information would be useful when advocating for employment with potential job seekers, families, or other key stakeholders.

The panelists agreed that providers should always answer two questions before they add a new metric to their data reporting systems: 1) Why is this data point collected? 2) What are we going to do with it? One of the biggest risks is collecting a lot of data and not using it.

my one tip is before people go out and create a spreadsheet that has data, that any statistics have a plan on how that’s going to fit into the larger picture of what you’re going to try and do. And that’s the number one way that’s going to make that day (Panelist)

Moreover, to ensure that the data tracked are useful and of high quality, providers should seamlessly integrate data collection and data use in the workflow of everyday work activities. Data dashboards should be easily accessible, simple, and straightforward to understand and use. For example, program managers meeting with their staff, funding agencies, or prospective job seekers and their families should be able to quickly access the system and get essential numbers in an easy format to share and understand.

This is so needed. It is a sorry state when a provider doesn’t know its own data. Primary consumers need to know what to ask each provider to make an informed choice (Attendee).

Whether providers leverage the data for billing and compliance reporting or for quality improvement, the amount of data collected can be overwhelming. Therefore, the panelists recommended that employment providers, especially large organizations, use electronic documentation software rather than relying on traditional paper or spreadsheets.

We do sooooooo much on paper still (Attendee).

Because it can be challenging to choose between so many vendors of electronic documentation software, the panelists shared some tips. First, make a plan about what data are needed and how they will be used. Second, find a vendor of electronic documentation software that meets your data plan. Third, prioritize software packages that can be easily customizable over time. Fourth, make sure that the software package comes with extensive technical support. Finally, to best leverage technology, it helps to have staff within the employment provider organization who understands both information technology and employment supports practices.

4Conclusions

This panel emphasized the importance of tracking metrics that matter for helping to improve the quality of employment support services and thus scaling up the employment outcomes of job seekers with disabilities. The main takeaways included:

• Funding agencies and other key stakeholders need to invest in identifying a set of standard metrics that can be used across employment providers and states. This would enable employment providers to better leverage their data for improving the effectiveness of their services and thus improving the employment outcomes of job seekers with disabilities.

• Each metric should be accompanied by the answer to why the metric is measured and what the employment provider or other key stakeholders are going to do with that data.

• Tracking data and using the data should be integrated seamlessly in the everyday workflow of employment consultants and their teams.

• Outcome metrics should include indicators of quality, such as time from intake to hire, job satisfaction, changes in earnings, changes in work hours, job retention, career advancement, and— when possible— overall impact of employment on other areas of the job seekers’ lives.

• To handle the large amount of information collected, employment providers may need to use electronic documentation software. Flexibility of the software and the availability of extensive technical support are key elements to consider when choosing a vendor.

Advancements in technology makes leveraging data for continuous quality improvement easier today compared to decades ago, when supported and customized employment were initially developed. It is up to policy makers, administrators, and other key stakeholders to enable employment service providers to take advantage of technology for improving their effectiveness, and thus improving the employment outcomes of people with disabilities.

Acknowledgments

The development of this manuscript was supported by Grant # 90IFDV0009 and grant # 90RT5019, National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The content of this presentation does not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL or HHS. The authors would like to thank APSE for organizing the conference and the participants in the audience who contributed to the panel conversation by sharing comments in the chat.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

References

1 | Allard, S. W , Wiegand, E. R , Schlecht, C , Datta, A. R , Goerge, R. M , & Weigensberg, E. ((2018) ). State agencies use of administrative data for improved practice: Needs, challenges, and opportunities. Public Administration Review, 78: (2), 240–250. |

2 | APSE. (2020). Certified Employment Support Professional: Certification handbook. https://apse.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Candidate-Handbook-Updated-January-2020.pdf |

3 | Association of Community Rehabilitation Educators [ACRE]. (2020). APSE/ACRE state guidelines for employment services personnel training certificates or certification. APSE Employment Support Professional Certification Council. https://apse.org/apse-acre-state-guidelines-for-employment-services-personnel-training-certificates-or-certification/ |

4 | Attaliades E. , ((2019) , October 17). Remarks from ADDP President/CEO [Conference presentation]. ADDP Talking Tech, Newton, MA. https://www.addp.org/event/addp-dds-present-talking-tech-2019 |

5 | Butter J. , Migliore, A. , Pavlak, J. , Aalto, S. , & Petrick, M. , ((2020) , June 29). Tracking metrics that matter for scaling up employment outcomes [Conference session]. APSE, Online. |

6 | Butterworth, J , Migliore, A , Nye-Lengerman, K , Lyons, O , Gunty, A , Eastman, J , & Foos, P. ((2020) ). Using data-enabled performance feedback and guidance to assist employment consultants in their work with job seekers. An experimental study. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 53: (2), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-201096. |

7 | Graham, C , Inge, K , Wehman, P , Murphy, K , Revell, W. G , & West, M. ((2013) ). Moving employment research into practice: Knowledge and application of evidence-based practices by state vocational rehabilitation agency staff. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 39: (1), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-130643 |

8 | Harkin, T. ((2012) ). Unfinished business: Making employment of people with disabilities a national priority. U.S. Senate, Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions. http://www.harkin.senate.gov/documents/pdf/500469b49b364.pdf |

9 | Mank, D. ((2016) ). Advisory Committee on Increasing Competitive Integrated Employment for Individuals with Disabilities. Report to the US Secretary of Labor, September 15, 2016. https://www.dol.gov/odep/topics/pdf/ACICIEID_Final_Report_9-8-16.pdf |

10 | Migliore, A , Butterworth, J , & Nye-Lengerman, K. ((2020) ). Tracking metrics that matter for scaling up employment outcomes: Rethinking management information systems. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. Manuscript submitted for publication. |

11 | Migliore, A. , & Nye-Lengerman, K. ((2019) , June 19). Identifying key metrics for effective employment supports. APSE, St. Louis, KS. |

12 | Migliore, A , Butterworth, J , Lyons, O , Nye-Lengerman, K , & Foos, P. ((2018) ). Supporting employment consultants in their work with job seekers: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 49: (3), 273–286. http://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-180973 |

13 | Nidilrr ((2019) ). National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research 2018–2023 Long-Range Plan. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/about-acl/2019-01/NIDILRR%20LRP-2018-2023-Final.pdf |

14 | Olshansky, D ((2019) , October 17). Electronic health records (EHR): What can they do for you? [Conference session]. ADDP Talking Tech, Newton, MA. https://www.addp.org/event/addp-dds-present-talking-tech-2019 |

15 | Results for America. (2019). Invest in what works: State standard of excellence. https://2019state.results4america.org/2019-invest-in-what-works-state-standard-of-excellence.pdf |

16 | Schmidt, E , & Rosenberg, J. ((2017) ). How Google works. Grand Central Publishing. |

17 | Valacich, J , & Schneider, C. ((2018) ). Information systems today: Managing the digital world (8th ed.). Pearson Education Inc. |

18 | Wehman, P , Taylor, J , Brooke, V , Avellone, L , Whittenburg, H , Ham, W , Molinelli, A , & Carr, S. ((2018) ). Toward competitive employment for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities: What progress have we made and where do we need to go. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 43: (3), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796918777730 |

19 | Weigensberg, E , Schlecht, C , Laken, F , Goerge, R , Stagner, M , Ballard, P , & DeCoursey, J. ((2012) ). Inside the black box: What makes workforce development programs successful? Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. https://www.frbatlanta.org/-/media/Documents/podcasts/economicdevelopment/InsidetheBlackBox.pdf |

20 | Winsor, J , Timmons, J , Butterworth, J , Migliore, A , Domin, D , Zalewska, A , & Shepard, J. ((2019) ). StateData: The national report on employment services and outcomes. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion. |