Employment First and transition: Utah school-to-work initiative

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Utah’s School-to-Work Initiative is funded by a Partnerships in Integrated Employment Systems Change grant. Our project focuses on building school-level collaborative teams to support transitioning students with the most significant disabilities. Participating students complete work experiences and paid internships leading to permanent competitive integrated employment prior to exit.

OBJECTIVE:

By integrating two predictors for post-secondary employment, our framework implements customized employment to demonstrate Employment First for students with the most significant disabilities.

METHODS:

An advisory board evaluated applications and selected Utah secondary schools representing urban, suburban, and rural areas. We provide professional development on transition during biannual community of practice meetings. Subject matter experts provide technical assistance to collaborative teams on implementing customized employment.

RESULTS:

Eight school districts have collaborative teams that serve nine secondary schools. We braid funding from VR, Medicaid Waiver, and WIOA to support students with significant disabilities obtain competitive integrated employment. Students’ outcomes have been challenged by the lack of employment providers for customized employment, the turnover of staff in agencies, and the limited resources for English language learners.

CONCLUSIONS:

We have successfully braided funding and collaboratively support 82 students with significant disabilities and families to navigate the adult agency process.

1Introduction

Successful outcomes in competitive integrated employment for transition-aged adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities continue to be low throughout the United States, despite promising practices and policies, such as supported and customized employment, the Rehabilitation Act, the Workforce Innovations and Opportunity Act, Employment First, and most recently, the Home and Community-Based Final Settings Rule. In fact, the American Community Survey estimates only 22.6 percent of youth aged 16–20 with a cognitive disability are employed (Cornell University, 2018). Prior to receiving the Partnership in Employment System’s Change grant (PIE) in 2016, interagency collaboration in Utah did not prioritize employment for students with the most significant disabilities. However, student outcomes indicated we needed to improve the employment outcomes of students with disabilities. The Utah Statewide Post High Outcomes Survey (2013-14) gathered data one year after the youth exited the secondary education with 82 young adults with ID (or their families) responding. Of those responding, 40% were not engaged in postsecondary education or employment, 11% worked less than 90 days, and only 2% of the respondents completed at least one term of postsecondary education. An overwhelming majority (77%) of respondents with multiple disabilities indicated they were not engaged in postsecondary education or employment. Of these respondents who were employed, 13% were working in a sheltered setting.

In 2016, The Utah Division of Services for People with Disabilities (DSPD) received a 5-year Partnerships in Integrated Employment Systems Change (PIE) grant from the Administration for Community Living to focus on competitive integrated employment for youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD). The goal of the Utah School-to-Work Initiative (USWI) is to ensure that students with the most significant disabilities access the full range of supports necessary to work, live, and be active in their communities before they exit secondary education.

The first guiding principle of the USWI model is establishing meaningful, community-based secondary employment experiences. Researchers have consistently found that having one or more paid jobs during secondary education is one of the strongest predictors of post-secondary employment of young adults with disabilities (Carter et al., 2012; Mazzotti et al., 2014, 2020; Test et al., 2009). Although Utah schools often provide work-based learning (WBL) experiences during secondary education to their students with disabilities, the WBL experiences tend to be unpaid and are often with the same employers year after year. In addition, WBL experiences are often not based on the student’s strengths, interests, preferences and needs. Based on our experience, when a student exits secondary education, the job does not continue and rarely results in a permanent, paid position. This work experience dynamic makes it vital that students are connected with and receive VR employment services prior to exiting secondary education.

The second guiding principle incorporated into our model, interagency collaboration of transition stakeholders, is another predictor of post-school success (Haber et al., 2016; Mazzotti et al., 2020; Test et al., 2009). We sustain interagency collaboration among key agencies including: local education agencies (LEAs/school districts), Vocational Rehabilitation (VR), Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Youth Counselors, Community Rehabilitation Providers (CRPs/employment service providers), the Division of Services for People with Disabilities (DSPD/state waiver agency), and Centers for Independent Living. Our collaborative teams focus on employment for transition-aged students with the most significant disabilities exiting post-high programs (18–22 yr old programs) in Utah. Through our local interagency teams, all partners brainstorm and collaborate to determine how the various agencies can integrate services and braid funding to support students with significant disabilities.

2Customized employment

The USWI incorporates customized employment (CE) as a strategy to meet the employment needs of students with the most significant disabilities. The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA, 2014) defines customized employment as: “competitive integrated employment, for an individual with a significant disability that is based on an individualized determination of the strengths, needs, and interests of the individual with a significant disability, and is designed to meet the specific abilities of the individual with a significant disability and the business needs of the employer.” (p. 1634). In other words, CE is not a job you would typically find in the job-market but is created to fit the skills and interests of the individual as well as the needs of the employer. CE is a promising practice for individuals with disabilities with positive outcomes including: (a) increased quality of life, (b) wages higher than minimum wage, and (c) attainment of part-time or full-time employment (Inge et al., 2018, p. 156). By combining CE services with WBL experiences and interagency collaboration, our goal is to produce positive employment outcomes for students with significant disabilities.

2.1Essential elements of discovery

Discovery is an important piece in carrying-out the USWI vision. “Discovery is an alternative to a traditional assessment or evaluation to determine employability” (Hall et al., 2018, p. 5). Unlike traditional assessments or evaluations, discovery presumes employability and is meant to uncover skills, strengths, interests, environmental preferences, support needs, and other factors which may affect employment. The employment specialist initiates discovery by engaging with the jobseeker, family, friends, and community. The employment specialist writes discovery observations objectively and in a positive manner, ensuring to keep up the philosophy that everyone can work with the right supports. As the first step in the CE process, discovery may require 5–9-weeks to complete because time to get to know the jobseeker and begin planning for job development (Hall et al., 2018). By incorporating the discovery process into the community-based work experiences, expanding internship opportunities, and building upon existing secondary transition programs, the USWI strengthens the connection and collaboration with employment service agencies.

3Project design and implementation

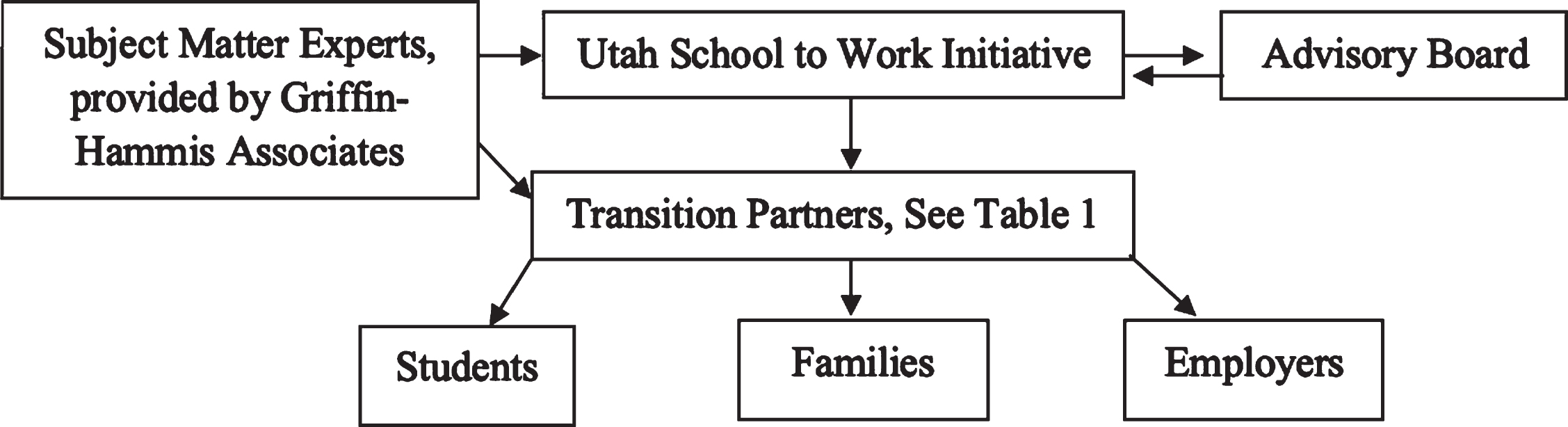

The first step in the project was creating an advisory board consisting of state-level administrators from each of the transition partners (see Fig. 1). The board also include a representative from the Utah Parent Center, a self-advocate, and a family member. Initially, the advisory board assisted with the development of the memorandum of understanding between their agencies for this project. Today, they provide ongoing guidance on achieving the project’s objectives and addressing systems change within their organizations. The advisory board continues to support the participation of their agency’s local representative by (a) encouraging buy-in; (b) requiring increased participation; (c) resolving challenges; and (d) clarifying agency policies.

Fig. 1

Utah School-to-Work Initiative’s Framework.

3.1Site selection

The second step in the project was selecting LEAs for the project. A request for application was distributed to all of Utah’s LEAs which outlined the expectations and requirements for the Utah School-to-Work Initiative. Schools were required to describe their current employment/transition programs and their visions for enhancement. USWI staff and advisory board members evaluated each school districts’ application using the following criteria: (a) does the district show a commitment for participation in training, phone calls, and events regarding this project; (b) does the district show a commitment to collect data and regular reporting for students and families participating in this project; (c) does the district show a commitment to technical assistance and consultation could improve transition practices and outcomes for students with the most significant disabilities; (d) does the district demonstrate readiness to support students with significant barriers who historically have been considered unemployable. Schools were also required to have: (a) a teacher who could serve as a lead team member; (b) support from the special education director; (c) supportive school leadership; (d) willingness to support students through the Vocational Rehabilitation process; (e) willingness to work with employment provider agencies and allow these agencies to work with students during the school day; and (f) the philosophy that regardless of disability, everyone can be competitively employed.

During the first three years of the project, the USWI was implemented in eight Utah LEAs, representing urban, suburban and rural areas. During the 1st year, three school districts participated. In the 2nd year, two additional districts implemented the project at three sites. In the 3rd year, three additional districts were added for a total of nine project sites in 8 school districts. The goal of the project was to have 10 sites by continuing to add districts in years four and five. However, by the 4th year, the existing teams were struggling to find customized employment providers with the caseload capacity to work on the project. Therefore, with the guidance of the advisory board, we decided to focus on building provider capacity and strengthening the nine existing sites before developing new sites. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we decided it was best to focus on the existing sites rather than expanding during the final year.

3.2Collaborative partnerships

The next step in developing the project was identifying transition partners for local interagency collaboration teams. We identified transition stakeholders that shared our goal for transitioning students and young adults with the most significant disabilities to achieve competitive integrated employment. The local interagency teams are led by the transition educator(s) at each site. A full list of transition partners and their roles and responsibilities can be found on Table 1.

Table 1

Transition Partners’ Roles and Responsibilities on Collaborative Teams

| Partner Agency | Role | Responsibilities |

| LEA | Team Lead | Leads monthly team meetings |

| (Special Educator) | Provides information and updates to students and families | |

| Completes the VR application process | ||

| Coordinates activities with partners | ||

| Provides WBL experiences | ||

| Collects, enters and analyzes student tracking sheets | ||

| VR | VR Counselor | Guides VR eligibility process and writes IPE with students |

| Provides pick list of CRPs for students and families | ||

| Authorizes employment with a CRP | ||

| Provides teachers guidance on Pre-Employment Transition Services | ||

| Coordinates benefits planning | ||

| DWS | WIOA Youth Counselor | Assists with eligibility for DWS |

| Provides coordination for paid internships and on-the-job training | ||

| CRP | Employment Specialist | Provides supported and customized employment services |

| Coordinates the discovery process | ||

| Provides Pre-Employment Transition Services | ||

| Collaborates with other team members to problem-solve | ||

| Coordinates transportation needs | ||

| DSPD | Support Coordinators | Provides information and support on competitive integrated employment to students |

| (Case Managers) | Coordinates DD services to support customized employment | |

| Coordinates transportation needs | ||

| Independent | Pre-Employment Transition | Provides Pre-Employment Transition Services |

| Living Centers | Services Provider | Coordinates activities for building life-skills, learning advocacy, and accessing recreation |

Sustaining these collaborative partnerships continues to be an important focus of the USWI because Utah agencies’ staff, transition educators, advocacy groups, and CRPs tend to work independently of each other and are siloed based on their agencies funding streams. USWI aligns transition stakeholders to provide a substantive provision of employment supports to students with disabilities. The collaborative framework provides an opportunity to identify ways braided services and funding can provide comprehensive services to students with the most significant disabilities. This framework is also important because in Utah, secondary transition educators historically do not work with the adult agency transition stakeholders. The USWI therefore enabled educators within the project to feel comfortable and confident that students will receive quality services from CRPs when student referrals are made.

One strategy for developing and sustain the interagency teams has been contracting with subject-matter-experts (SMEs) to provide technical assistance and support to maintain the project’s momentum. During the local team meetings, each partner reports on students’ progress and the other team members assist by brainstorming and problem-solving as needed. The team meetings create peer-support to remain engaged with the students between meetings and ensure students continue to progress towards employment.

In addition to attending team meetings, the SMEs provide training on benefits planning, creating positive personal profiles, engaging families, strengthening and individualizing work-based learning experiences, and using technology (high and low-tech). The USWI has offered quarterly webinars based on the team’s interest and needs identified during onsite visits, surveys and regular project evaluation.

3.3Students recruitment and selection

Student recruitment for the project is an ongoing activity on the USWI. Students are primarily recruited by special education teachers from the 18–21 year old post high transition programs. Students and families are given project information at various events, including individual meetings (i.e., case conferences or parent-teacher conferences), parent nights, or open houses. Recruitment occurs primarily during the spring semester, which allows students and families the summer months to complete the application and eligibility determination for services. The USWI service coordination begins in the fall during the third year prior to their exit from secondary education. Students are required to be receiving Medicaid waiver Home and Community-Based Services or to be on the waiting list for waiver services in order to participate. All students participating in the project must be significantly disabled as defined by the Utah State Office of Rehabilitation (2020), which is that eligible individuals must have two serious functional limitations which require multiple services over an extended period of time. We did not reject any student from USWI due to the severity of their disability.

During the 1st year of the project, each site was asked to recruit 3–5 students who were three years from exiting secondary education. We believe that 3 years were needed to adequately connect students with services, explore employment through customized employment, and raise students’ and families’ expectations for competitive integrated employment. The three-year time frame gives students and families the time to develop a clear vision and expectation for competitive integrated employment while accessing a full range of available services including work experiences and paid employment.

All accepted students and parents attend an orientation with presentations on the USWI’s purpose of providing each student has multiple opportunities to explore employment. During orientation interagency team members describe their services and their roles on the project. After orientation, all students are required to apply and be eligible for services from DWS and VR. Each team member works with students and families to ensure that students are enrolled and actively engaged in services from VR, DWS, and DSPD. In addition, VR funds benefits planning from the benefits information network for all students. The benefits plan demonstrates the financial benefit of competitive integrated employment for the student. In total, 82 students have participated in the USWI.

3.3.1Families

The USWI collaborative teams ensure families of students with disabilities understand Utah’s Employment First initiative and the expectation that students will obtain community integrated employment of the student’s choice prior to exiting secondary school. USWI focuses on students and families understanding the roles of each transition stakeholder and how the agency assists in the employment process (e.g. transportation to job, communicating with employers, finding internships/jobs, etc.). USWI also provides information on employment services and the providers of customized employment in their communities. We believe that by talking frequently with students and parents about vocational expectations builds their interest in and expectation for competitive integrated employment. By helping parents understand a customized employment approach, we expand their ideas about what employment means. Many parents we met did not have a vision for their child working a typical job or working 40 hours a week. By sharing customized employment examples of students working, we help parents raise their expectations and develop buy-in from families in the project.

4Products developed and events held

Since 2016 we have developed a number of tools and products to support the project implementation. The first tool is a student tracking form for team leads to maintain service and employment outcome data. Data collected includes linkage to each agency, progress in the CE process, number and length of internships and paid work experiences, and employment outcomes at exit (including employment status, job title, rate of pay, hours, and benefits). The USWI team uses this data to understand model’s challenges and identify areas for improvements. The second tool developed is the Continuous Quality Improvement Self-Evaluation. The interagency teams conduct quarterly self-evaluations to reflect on their key focus areas, highlight their strengths, identify areas for improvement and determine actionable steps and strategies to improve.

5Lessons learned

Through this project, we have gained insight into the barriers and challenges facing, students, parents, special educators, CRPs, and state agencies. The following sections highlight the lessons learned with each group.

5.1Families

Although we knew that many families would not have the expectation for competitive employment for their children, we were surprised the diversity of families’ opinions within a school. Many families would not consider integrated employment for their children. Yet, other families were excited and optimistic when they learned about Employment First and the available services to assist their child obtain competitive integrated employment. Unfortunately, we also learned that there was a lack of support, resources, and options for English language learners and non-citizens.

Another lesson learned with families is that with multiple funding agencies working together, it becomes logistically challenging for students and their family to navigate through the multiple moving parts. We found a large variation in the expectations for students and families within agencies. Families are easily confused if we do not clearly explain how the agencies are working together to pay for services.

5.2Community rehabilitation providers

One of the barriers in carrying-out the project included the limited number of providers who were trained and had the capacity to deliver CE to students with significant disabilities. The barrier was compounded by the fact that in Utah, CRPs believed that VR’s customized employment funding inhibited its feasibility. The second barrier was the high turnover of employment specialists. This turn-over caused significant delays in employment outcomes for students (Grossi et al., 2019). Over time, the need for more CRPs and/or employment specialists providing customized employment impacted the number of students we could serve. Recently, VR released increased rates for CE services. We are hopeful this increase in rates will result in more CRPs providing this service.

5.3Secondary special educators

Historically, special education teachers have not had a leadership role on collaborative teams (Plotner et al., 2017). We have found that transition coordinators are effective leaders because facilitating interagency teams is frequently in their job description. In addition transition coordinators often have established relationships with students and families and experience and knowledge of the transition process. However, secondary education teachers often struggle as team leaders and cannot proactively support their collaborative teams due to the multiple responsibilities. Often, secondary special educators have unexpected situations which demand their time such as student emergencies and staffing issues. As a result, special educators needed to adjust their daily plans and priorities to meet their students’ needs. Therefore, the added team lead roles can be challenging for special education teachers.

5.4VR Counselors

As the funder of customized employment services, it is essential that the VR counselor understand the project and has high employment expectations for students with significant disabilities. Without the local VR supervisor’s engagement and support of the project, it has been difficult for the student’s to move smoothly and efficiently through the VR system.

6Future direction

As the USWI moves into its fifth and last year of the PIE grant, we realize we have just begun to effectively support students with significant disabilities obtain competitive integrated employment. We have learned valuable lessons that will help improve interagency collaboration to support students obtaining employment prior to exiting school. Building upon our lessons learned, we are moving forward with multiple action steps for sustaining USWI. First, we are partnering with our National Technical Assistance Center, the YES! Center, and providing a webinar series and a community of practice for special educators and CRPs on building meaningful lives. These training opportunities will magnify the necessity of including competitive integrated employment and inclusive supports within secondary transition programs and adult services. Second, USWI staff will be partnering with VR to implement CE training to CRPs throughout Utah in order to make this training more affordable and accessible to CRPs. We hope that by bringing this training in-state, Utah can begin to build capacity for offering CE services. Third, we are developing a toolkit for educators to create collaborative teams within their LEA. We anticipate this toolkit will help sustain the project’s efforts and that additional LEAs will implement our model. We hope these actions will assist in addressing attitudinal barriers within our agencies, schools, businesses, and communities that people with significant disabilities can be successful in competitive integrated employment.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

1 | Carter, E. W. , Austin, D. , & Trainor, A. A. ((2012) ). Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23: (1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207311414680 |

2 | Cornell University. (2019). Disability statistics. Retrieved November 22, 2020 https://www.disabilitystatistics.org/reports/acs.cfm?statistic=2 |

3 | Disability Classification and Order of Selection Overview. (n.d.). Utah State Office of Rehabilitation. Retrieved November 24, 2020 https://jobs.utah.gov/usor/vr/about/factsheet.pdf |

4 | Grossi, T. , Thomas, F. , & Held, M. ((2019) ). Making a collective impact: A School-to-Work Collaborative model. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 51: (3), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-191054 |

5 | Haber, M. G. , Mazzotti, V. L. , Mustian, A. L. , Rowe, D. A. , Bartholomew, A. L. , Test, D. W. , & Fowler, C. H. ((2016) ). What works, when, for whom, and with whom. Review of Educational Research, 86: (1), 123–162. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315583135 |

6 | Hall, S. R. , Keeton, B. , Cassidy, P. , Iovannone, R. & Griffin, C. ((2018) , December). Discovery fidelity scale. Griffin-Hammis Associates. https://www.griffinhammis.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/DFS-December-2018-4-2.pdf |

7 | Inge, K. J. , Graham, C. W. , Brooks-Lane, N. , Wehman, P. , Griffin, C. , Inge, & Wehman. ((2018) ). Defining customized employment as an evidence-based practice: The results of a focus group study. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 48: (2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-180928 |

8 | Izzo, M. V. , & Lamb, P. ((2003) ). Developing self-determination through career development activities: Implications for vocational rehabilitation counselors. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 19: (2), 71–78. |

9 | Mazzotti, V. L. , Rowe, D. A. , Kwiatek, S. , Voggt, A. , Chang, W. H. , Fowler, C. H. , Poppen, M. , Sinclar, J. , & Test, D. W. ((2021) ). Secondary transition predictors of postschool success: An update to the research base. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 44: (1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143420959793 |

10 | Mazzotti, V. L. , Test, D. W. , & Mustian, A. L. ((2014) ). Secondary transition evidence-based practices and predictors: Implications for policymakers. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 25: (1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207312460888 |

11 | Oertle, K. M. , & Seader, K. J. ((2015) ). Research and practical considerations for rehabilitation transition collaboration. Journal of Rehabilitation, 81: (2), 3–18. |

12 | Plotner, A. J. , Mazzotti, V. L. , Rose, C. A. , & Teasley, K. ((2020) ). Perceptions of interagency collaboration: Relationships between secondary transition roles, communication, and collaboration. Remedial and Special Education, 41: (1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518778029 |

13 | Plotner, A. J. , Trach, J. S. , & Strauser, D. R. ((2012) ). Vocational rehabilitation counselors’ identified transition competencies: Perceived importance, frequency, and preparedness. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 55: (3), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355211427950 |

14 | Repetto, J. B. , Webb, K. W. , Garvan, C. W. , & Washington, T. ((2002) ). Connecting student outcomes with transition practices in Florida. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 25: (2), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/088572880202500203 |

15 | Test, D. W. , Mazzotti, V. L. , Mustian, A. L. , Fowler, C. H. , Kortering, L. , & Kohler, P. ((2009) ). Evidence-based secondary transition predictors for improving postschool outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 32: (3), 160–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885728809346960 |

16 | WINTACT. (2017). The essential elements of customized employment for universal application. http://www.leadcenter.org/system/files/resource/downloadable_version/WINTAC_Essential_Elements_of_Customized_Employment_for_Universal_Application_005_FInal.pdf |