What matters: Lessons learned from the implementation of PROMISE model demonstration projects

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

PROMISE Model Demonstration Projects (MDPs) are on the front line of innovative, comprehensive supports for transition-aged youth and their families. Investments made through PROMISE can inform future policy and practice in youth transition, family engagement, and systems collaboration. This paper gives an overview of emerging lessons learned throughout the implementation of PROMISE MDPs.

DOCUMENTS REVIEWED:

This paper provides a comprehensive overview of documents from key stages of project implementation, including technical assistance plans, briefing books, mid-course and annual progress reports, and comprehensive process reports. These documents were reviewed regarding five core areas around which PROMISE was developed: collaboration models, professional development, leadership, service delivery, and family engagement.

FINDINGS:

The most salient emerging themes concern service delivery, leadership, interagency collaboration, professional development, and family engagement.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS:

This document review provides the foundation and directions for a further evaluation of lessons learned in PROMISE MDPs. These lessons can inform recommendations for sustainability, the use of best practices, and the integration of policies that support employment and post-secondary education for youth with disabilities and their families. It is essential that future research continues to develop a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of these emerging themes.

1Introduction

Since the rollout of PROMISE in 2012, six Model Demonstration Projects (MDPs) throughout the United States have connected with more than 13,000 youth with disabilities who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits and their families. The youth included in this program were living with a disability in a family with income at or below the federal poverty line. Youth were randomly assigned to the PROMISE intervention group, or a control (service-as-usual) group. The MDP interventions were designed to meet PROMISE’s goals, for both the youth and their families, which included: 1) increased educational attainment for the youth SSI recipients and their parents; 2) improved rates of employment, wages/earnings, and job retention for the youth SSI recipients and their parents; 3) increased total household income; and 4) long-term reduction in SSI payments. The core services provided to the youth in the intervention group included (1) case management, (2) benefits counseling, (3) career and work-based learning experiences, (4) self-determination training for youth, and (5) parent/guardian training and information. Collectively, these services aimed to improve employment and post-secondary educational outcomes resulting in long-term reductions in the child’s reliance on SSI (Fraker, Carter, Honeycutt, Kauff, Livermore, & Mamun, 2014). Over the course of the implementation of these MDPs, a unique view has begun to emerge regarding the experiences of youth and families in this population and the socioeconomic landscape in which services and supports are delivered to this population.

PROMISE MDPs were uniquely situated to connect with families who live at the intersection of disability and poverty. Throughout these efforts, MDP staff were able to witness, first-hand, the facilitators and barriers these youth and families experience in their pursuit of employment and post-secondary education. By design, PROMISE MDPs were centered around cross-agency collaboration to provide comprehensive supports for youth and families while maximizing coordination of these services.

PROMISE represents a collaborative effort among four federal agencies: Social Security Administration, U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs and Rehabilitation Services Administration. The MDPs were granted to five individual states (Arkansas, California, Maryland, New York, & Wisconsin) and one consortium of six states (APSIRE: Arizona, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Colorado, Montana).

Funds were also awarded to a national technical assistance center (PROMISE TA Center), at the Association of University Centers on Disability (AUCD). The purpose of the PROMISE TA Center is to provide technical assistance to assist MDPs in the implementation of their projects and to increase their capacity to improve services and supports to child SSI recipients and their families (U.S. Department of Education, CFDA 84.418T, 2014). The PROMISE TA Center was designed to support MDPs by developing: (a) improved skills of State and local personnel to support partnerships among agencies that provide services; (b) improved implementation of interventions for MDP SSI recipients and their families; (c) increased knowledge that supports training to the families of participating children; (d) improved methods to develop and implement a plan for conducting a formative evaluation; (e) improved methods for collecting data and the capacity to track and manage MDP information (U.S. Department of Education, 2014, p. A-10).

A targeted activity for the PROMISE TA Center included gathering lessons learned over the course of PROMISE, based on the experiences of the MDPs to provide valuable insights regarding system strengths, challenges, opportunities, and practices that support employment and post-secondary education opportunities for youth recipients of SSI. While each MDP has specific state and local context contributing to the lessons learned, there remain a number of key lessons that resonate across projects, regardless of location or MDP state context.

Examining factors that contributed to the success of PROMISE MDPs can yield important information and advance current knowledge on practices potentially useful in supporting youth in achieving post-secondary education and employment goals. As MDP implementation is finishing, researchers will begin to be able to comprehensively evaluate the lessons learned over the course of PROMISE that can inform future systems change. This paper aims to provide a foundation and direction for those future comprehensive evaluations through a comprehensive overview of documents developed at key points over the course of project implementation.

This paper provides a preliminary summary of lessons learned in the five core components through which PROMISE MDPs were charged to initiate systems change: (1) interagency collaboration models, (2) professional development, (3) leadership, (4) service delivery, and (5) family engagement. These emerging lessons learned come from a robust and comprehensive document review, spanning the course of PROMISE implementation and seeks to answer the following: What are connections among the lessons learned from the implementation of PROMISE across MDPs?

2Documents reviewed

This paper is the result of a comprehensive, longitudinal document review of key documents developed during project implementation from 2014–2018. This overview provides preliminary themes of lessons learned over the course of implementation of the PROMISE intervention. These emerging themes will be useful for future researchers to comprehensively evaluate PROMISE lessons learned regarding systems change in the coming years after PROMISE activities are completed. This paper is intended to provide a broad overview of lessons learned through the lens of project objectives outlined for each MDP.

2.1Document categories

A total of 86 documents were gathered for this overview. These documents included any summary or process documents created over the course of project and intervention implementation from 2014–2018. These documents fell into eight categories which include:

2.1.1Technical assistance plans

All six MDP project directors received ongoing technical assistance (TA) from the PROMISE TA Center, including the development of customized TA plans during the initial years of the PROMISE TA Center. In addition, each MDP also had individualized professional development and training plans created within their projects. PROMISE TA Center support focused on providing additional support (individually, or collectively across projects) that would allow MDPs to efficiently and effectively implement the PROMISE services. As such, MDP TA plans varied somewhat across states, but primarily focused on strategies for achieving project goals and an embedded evaluation to document progress, successes, and challenges experienced.

2.1.2Project review reports

Midway through the PROMISE project, each MDP wrote a comprehensive briefing book that contained a project model overview; detailed information about project activities; progress related to performance measures; formative evaluation process and findings; initial lessons learned; ongoing challenges, barriers, and potential solutions; and proposed activities for the remaining years in the project.

Each MDP received a project review midway through project implementation. MDPs were requested to prepare and submit a written summary of progress and accomplishments which was then reviewed by a panel of two external reviewers, MDP representatives, and the project officer and other Office of Special Education (OSEP) staff. These project reports included reviewer comments, OSEP recommendations, and information regarding follow-up discussions with MDP representatives.

2.1.3Annual Performance Reports (APRs)

APRs included information on project progress toward identified goals, performance measures, as well as highlights of project accomplishments over the previous year. The project accomplishments included successes in the areas of interagency partnerships, service intervention, recruitment and retention, and training and technical assistance. APRs also included results of formative and summative evaluations over the previous year.

2.1.4Project director reports

In January, 2018, MDP directors reported on various aspects of project activities. These reports included the total numbers of youth enrolled in PROMISE (in both the intervention and control groups), career- and work-based learning opportunities, youth employment, youth education, benefits counseling and financial capability services, finances, and agencies or organizations involved in the collaboration efforts.

2.1.5Social Security Administration (SSA) Request for Information (RFI)

In 2018, SSA released an RFI regarding the implementation of PROMISE and how that implementation could inform transition services. Several projects responded to this RFI. These responses were included in the current overview.

2.1.6No-cost extension requests

PROMISE grants officially ended September 30, 2018; however, all six MDPs and the TA Center requested and received no-cost extensions. Each project proposed different activities during the no-cost extension year (October 1, 2018-September 30, 2019). These proposals indicated progress to that point as well as proposed activities to be implemented in the no-cost extension year that would enable the project to further meet its goals.

2.1.7Process analysis reports from Mathematica Policy Research (MPR)

MPR leads the national evaluation of PROMISE (Fraker et al., 2014). Throughout the life of the project, MPR has been responsible for collecting and analyzing all data from youth in intervention and control groups as a part of the randomized control trial (RCT) design. MPR also conducted thorough analyses of the processes of each individual MDP. The process analyses reports represent an examination of internal and external factors of PROMISE implementation within an MDP, including relationships among the partner organizations, program implementation, and features of programs that impact youth and families (Fraker et al., 2014).

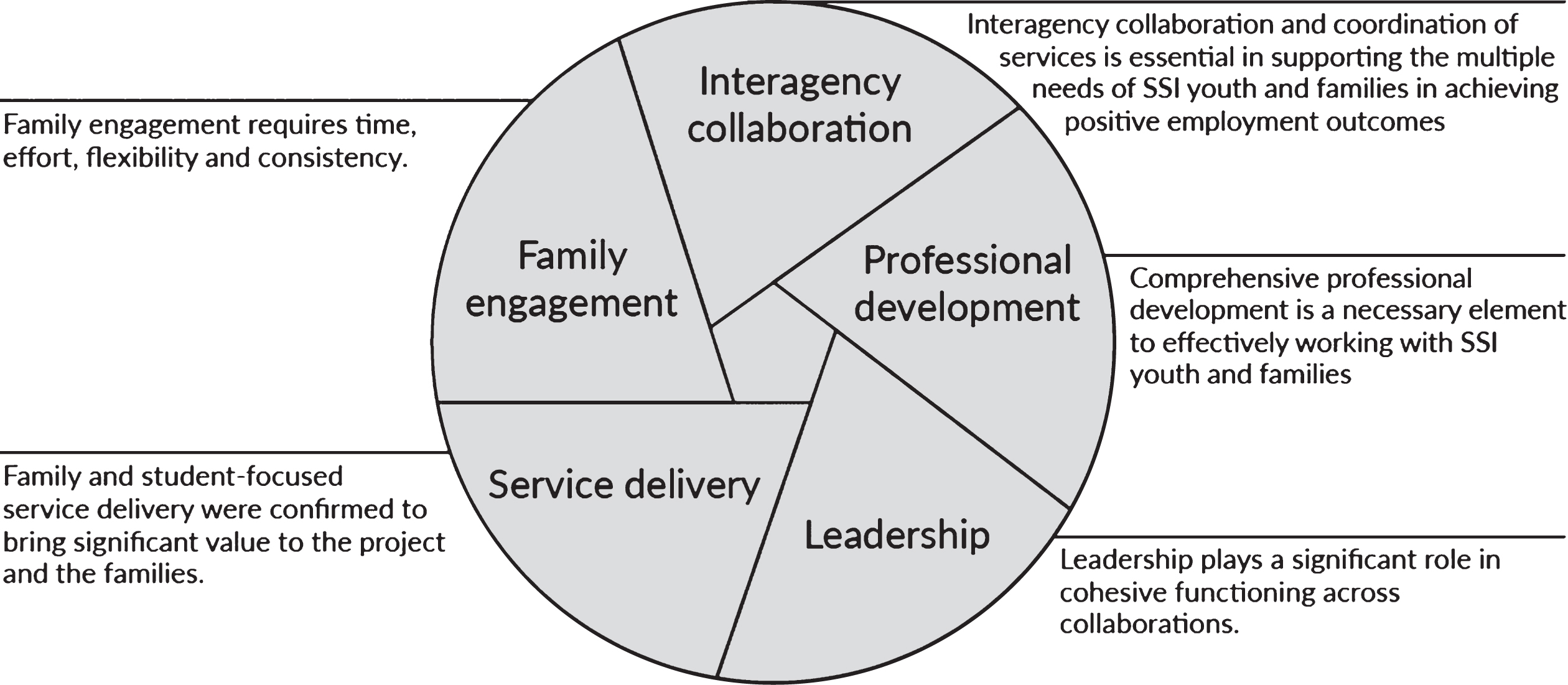

Fig.1

Lessons learned for systems change.

2.2Document review process

Documents were examined to identify lessons learned that were consistent across the six MDPs in the five core areas in which MDPs were required to deliver services in, as mentioned above. As such, document reviewers sought to identify the major lesson learned in each category as well as emerging sub-themes within each category. In order to verify the authenticity of the identified themes and sub-themes associated with the lessons learned, researchers engaged in member checking at a group level. Identified preliminary themes and emerging sub-themes were presented to all MDP directors as well as key staff from each project (project directors chose key staff; their positions within the project varied among MDPs). This presentation occurred in-person in a group setting. The group was then given the opportunity to comment on the identified preliminary themes and emerging sub-themes. There was consensus that the preliminary themes and emerging sub-themes were relevant and important and that they provided a significant foundation for a more thorough investigation of the many of the lessons learned about systems change over the implementation of PROMISE. This iterative process with MDP leadership and staff was essential in determining the preliminary themes and emerging sub-themes presented here. Based upon the feedback obtained during this presentation, wording was slightly altered on a few preliminary themes and emerging sub-themes. Overall, however, they remained unchanged.

3Findings

Within each of the five core areas of systems change guiding this overview, one primary, preliminary lesson learned was identified along with other emerging sub-themes within each of the systems impact areas. The primary preliminary lesson learned was repeated consistently throughout many documents and across projects. Emerging sub-themes were found across projects, but not as consistently throughout documents over time. It is important to note that the five areas guiding the overview are not independent from one another. Rather, they are highly interrelated. For example, family engagement informs service delivery which, in turn, informs professional development, which then has implications for leadership and interagency collaborations. No one category is independent of the other, and lessons learned in one category necessarily influence each of the other categories.

3.1Lesson learned #1. Interagency collaboration: Interagency collaboration and coordination of services is essential in supporting the multiple needs of SSI youth and families in achieving positive employment outcomes.

Interagency collaboration and the coordination of services, based on strong partnerships with multiple stakeholders, served as the foundation on which the PROMISE program was established and continued to be central to each project’s implementation. Investments and commitments by multiple federal and state agencies, schools and community service agencies, and families were central to improving the education and employment outcomes of SSI youth. The youth and families who were a part of the PROMISE project lived at the intersection of disability and poverty. Youth and families living with disability are often supported by one system, while youth and families living in poverty are supported by another system. These families, living concurrently in both worlds, faced unique circumstances that did not belong to either the disability or the poverty world alone. As such, the diverse and complex needs of these youth and families required coordinated partnerships, consistent messaging, and cross agency communication. PROMISE MDPs provided critical linkages across systems to prioritize education and employment for youth. Each PROMISE MDP devoted significant time, energy and resources to engage agency and family stakeholders in achieving project goals. To further understand the challenges and complexity of interagency collaboration five sub-themes were identified.

3.1.1Interagency collaboration sub-themes

First, data sharing on the youth and families across multiple agencies is essential. Examples include integrated Medicaid and Vocational Rehabilitation data, cross agency access to school records and individualized education plans (IEPs), and coordinated assessment data. This included methods of ensuring data collected in different agencies was stored in similar ways with unique identifiers that enabled all data for individual participants to be connected with that individual. This data sharing was essential for monitoring both progress and engagement.

The second and third emerging subthemes in this area were connected to one another. Systems change requires that agency stakeholder roles and responsibilities must be clearly defined. The ability to provide comprehensive support for these youth and families necessitated engagement of a wide variety of agencies with clearly define responsibilities. Examples include coordinated team meetings and or IEP meetings, inviting other support team to participate, and ensuring that parents or family members were informed of and could participate in planning and meetings. This allowed supports to be delivered in a robust and efficient manner. Engaged support teams were better able to meet the needs of youth and family and build the necessary trust to maintain engagement in PROMISE activities over time.

The fourth subtheme addressed strategies for maintaining communication among stakeholders. In order to ensure consistent engagement with clearly defined roles among agencies, clear communication strategies had to be developed and used. This allowed all agencies to be on the same page as one another. Examples including sharing assessment, IEP, and IPE (individualized plan for employment) between team members, and ensuring that case managers and coaches had up-to-date and accurate information to share with youth and families. In addition, PROMISE staff who had direct access to families could also share information directly with support team members to maximize support and engagement.

The fifth subtheme related directly to the youth and families PROMISE served: aligning IEPs (education) and IPEs (Vocational Rehabilitation) promotes a seamless transition from school to employment opportunities. This alignment allowed for the student to move from the education system to the adult service system without having to create an entirely new plan. Furthermore, it ensured that the youth’s school goals were contributing to the attainment of their employment goals after finishing high school.

3.2Lesson learned #2. Professional development: Comprehensive professional development is a necessary element to effectively working with SSI youth and families

A diverse (i.e. cultural, linguistic, racial, economic) staff was essential to serve PROMISE youth and families, meet project goals, and enhance youth and family outcomes. Staff from a variety of backgrounds had to be able to reach out, connect to, and engage PROMISE youth and families throughout the project: from recruitment through service delivery. As noted above, these youth and families were living in a very unique world, and many families were completely disconnected from any support agencies. Thus, staff working to recruit, engage, and support these families needed to develop a distinct set of skills situated within a foundation of cultural competency that involved recognizing the particular experiences of youth with disabilities and families. Respectful and engaging strategies to work with families and youth who live in deep poverty are vital, but they are not necessarily the skills traditional human service professionals, case managers, or coaches had been trained for. A significant investment in staff training, mentoring, professional development, and supervision were required to ensure that staff in each project connected with families within the appropriate cultural context, while also providing interventions with fidelity. In addition, training on recruitment, engagement, and case management were necessary to ensure contractors were adequately prepared to respectfully and effectively support diverse youth and families with complex needs.

3.2.1Professional development emerging subthemes

Within the area of professional development, four subthemes were also identified. Staff need specific knowledge on the services and supports that are directly relevant to meeting the needs of SSI youth and families. First and foremost, it was clear that staff development needs to be an ongoing process given that new needs continued to emerge over the course of implementation of the projects. PROMISE staff and leadership moved through infrastructure and project kickoff, through recruitment, engagement, and service delivery. The skills and priorities required for through the different states of the project required that staff be flexible, open, and supported in developing new skills and knowledge to work with youth and families. Working with this population involved consistently gauging the participants’ needs and responding to those needs. This required ongoing training for front-line staff. This is related to the second identified subtheme: The need for well-trained and diverse staff who are able to meet families and youth where they are (literally by meeting families in their homes at times that worked best for them and figuratively by making sure information was appropriate for the families). Staff also needed to provide supports in an individualized way that maintains fidelity of implementation while meeting the unique the needs of the youth and family.

The third and fourth subthemes were both about situating professional development within the broader context of the project. The third subtheme goes beyond the scope of the PROMISE project to identify how the PROMISE project can sustainably influence the way services are provided to this population. When building staff training, it is important to consider where there are currently gaps or needs in the community outside of the project. For example, assisting staff in obtaining Benefits & Work Training Certification or ACRE (Association of Community Rehabilitation Educators) or CESP (Certificate for Employment Service Professionals) certification will allow those staff to fulfill a needed role in the community even after the end of the project.

The fourth subtheme is about leveraging local context to build the PROMISE workforce: employing interns from local universities is a useful strategy in supporting positive outcomes. Each MDP existed within state and local service systems. The model of PROMISE allowed for MDPs to customize their approach to draw on exceptional features or partnerships within their service systems to meet the needs of youth and families in creative ways.

3.3Lesson learned #3. Leadership: Leadership plays a significant role in cohesive functioning across collaborations

Each PROMISE MDP was led by the PROMISE project director with additional designed project leaders. Directors also engaged research, evaluation, and support staff to ensure the fulfillment of administrative and service-related functions. Each MDP was charged with ensuring delivery of a new intervention to a population not commonly reached with traditional service approaches. Because PROMISE interventions required a significant number of front-line staff (e.g. connectors, case managers, etc.) and contractors, budgets and program design accounted for this. However, adequate numbers of middle managers and project leaders were also necessary to ensure accountability, fidelity, contractual operations, as well as provide supervision and leadership to staff. This required that project directors be flexible, direct, proactive, and highly engaged in their work.

Furthermore, they had to be able to find the right team to support the intervention activities. In order to adequately support, train, and supervise the large numbers of staff (see professional development lesson learned) needed to deliver intensive and comprehensive interventions, directors needed to work with other project staff to create robust management structures. In addition, the federal, state, and local interagency collaborations required that, at all levels, leadership understood the purpose of the project and were able to work with one another to see that purpose realized. The PROMISE director within an MDP fostered improved collaboration, communication, and motivation within the project.

3.4Lesson learned #4. Service delivery: Family and student-focused service delivery were confirmed to bring significant value to the project and the families

Traditional service delivery structures at the federal, state, and local levels are not inherently person-centered enough to focus on individual youth and family needs, and that is particularly true with the population PROMISE aims to serve and support. Within the PROMISE project, it was necessary to find a balance between fidelity to the intervention design and allowances for innovation and flexibility in service delivery. Historically, employment and educational supports for youth with disabilities have not been provided in an individualized or person-centered way. Attempts to find this balance resulted in new service approaches to engage each youth and their family, meeting them where they were at (literally and figuratively) to deliver the interventions inherent to the PROMISE model. Prioritizing family- and youth-driven services and supports maximized engagement and participation in PROMISE and empowered families and youth to pursue post-secondary education and community employment. Additionally, specific approaches within MDPs assisted in maximizing and engaging youth and families.

3.4.1Service delivery emerging subthemes

There were four identified subthemes within service delivery. These subthemes indicated when, where, and how services needed to be delivered. First, intervention services must be delivered by someone the family trusts and delivered in a way that is highly relevant to the family. Second, it is important to continuously evaluate family/parent perceptions of actions taken on behalf of their child to maintain their active involvement and engagement. Third, families and SSI youth need access to information on community services and supports that helps them in future planning and decision making. Finally, developing programming that fits within existing service and support structures (e.g., embedding PROMISE services in the existing VR fee-for-service structure) can allow for sustainability embedded in the program from the start.

3.5Lesson learned #5. Family engagement: Family engagement requires time, effort, flexibility and consistency

Connecting with and engaging families within this population was critical throughout the project: engagement through service delivery. Family and youth engagement were constant, ongoing goals and activities for PROMISE staff. This required PROMISE staff to be purposeful, timely, and consistent with PROMISE messaging and support. Many families who were enrolled in the intervention had a distrust of service systems. Thus, not all families engaged immediately, nor did they engage in consistent ways; this resulted in the need to customize approaches to better connect with each youth and their family. Consistent and ongoing commitment to reaching out to families was critical, as a family that was disconnected at first sometimes engaged in the project at a later point in time. This also required a new way of thinking about and accepting family engagement. Current, or non-PROMISE models of service, may drop or disenroll youth or families who failed to participate or engage. In PROMISE MDPs did not drop our exclude families or youth who did not engage. Instead, over the life of the project they continued with outreach and touchpoints to encourage participation. In some cases, youth and families engaged after more than twelve months of being disengaged. Meeting families where they were also required significant time and commitment, but resulted in increased trust and, thus, deeper and stronger engagement.

3.5.1Family engagement emerging subthemes

Documents further indicated that through adaption, MDPs were able to reach and maintain a connection with families and youth. This was done through the consideration of several factors. Flexibility in recruitment and intervention activities was the key element to family engagement. First, family backgrounds, experiences, and needs vary widely and these aspects need to be thoroughly understood and addressed to fully engage. Second, families involved in PROMISE were typically not engaged with any other community agency service structures. PROMISE was able, in many cases, to help families become re-engaged in existing systems, including VR and the school (e.g., families began attending IEP meetings more consistently). Finally, intensive case management with frequent meeting options was useful in engaging families.

4Discussion

The PROMISE project set forth a model framework to test interventions and strategies that promote employment and post-secondary education for youth on SSI. Each of six PROMISE MDPs engaged five areas of system change to increase the employment and post-secondary education of youth with disabilities, while potentially decreasing dependence on SSI in the future, to increase employment and post-secondary education of youth with disabilities, while potentially decreasing dependence on SSI in the future.

National demonstration projects such as PROMISE represent federal cross-agency investments and coordination to test and improve services for youth with disabilities and their families. The lessons learned from PROMISE can be used to inform future policy and practices in the field and lessons learned can be extended beyond service delivery and application. The nature of PROMISE and MDP design provide lessons about system improvements, collaboration, development, engagement, and sustainability. These lessons and findings can be used to inform both federal and state policy makers in how to improve the quality and delivery of services, while also enhancing infrastructure that is critical in the provision of services to youth with disabilities and their families nationwide.

The lessons learned from PROMISE, gained through this comprehensive longitudinal document review reveal and affirm a number of messages that can be beneficial for future work and research in the field. It is important to use these preliminary lessons and emerging sub-themes to focus future work in understanding the lessons learned over the course of this significant project.

4.1What are connections among the lessons learned from the implementation of PROMISE across MDPs?

There are three emerging overarching themes that can be found across the five primary lessons learned. These themes are intertwined throughout the five preliminary lessons learned. As such, they create an additional narrative within the lessons. These overarching themes are trust, flexibility, and collaboration. These ingredients increase the impact and applicability of the preliminary lessons learned.

Building trust with the youth and family is critical at every stage, but often most impactful in the early stages of a relationship. Without a trusting relationship, where the youth and family know the support professional will be there, recruitment, engagement, service delivery cannot occur with intended impact. Trust leads to relationships, and relationships often lead to participation and commitment from youth and families. MDPs report that while trust-building is not a core service, it is a central feature and tenant of PROMISE to ensure that both youth with disabilities and their families are able to benefit from PROMISE services. Furthermore, trust is not limited to trust between the project and the families. It also applies to the development of the inter-agency collaborations. There must be trust among the agencies. It also applies especially to the relationship between the MDPs and communities, particularly since these projects were operating in often marginalized communities. It was essential that project directors and staff involved communities and community leaders in planning processes. Furthermore, project directors and staff had to demonstrate to communities that they would follow through on plans and promises.

The second cross-lesson theme was flexibility. This included flexibility in approach, flexibility within a system, and flexibility with services. This was a distinct challenge for MDPs as services needed to be delivered with fidelity for purposes of the broader research study. However, time and again MDP directors and staff reported that the youth with disabilities and their families are more likely to engage and benefit from services and supports (PROMISE and non-PROMISE related services) when those services and supports could meet the family’s individual needs, schedule, and preferences. Living lives at the intersection of disability and poverty often leads to unforeseeable circumstances and barriers for both youth with disabilities and their families that can make compliance with eligibility and participation extremely difficult. Services that were flexible and at-the-right time ensured that that youth with disabilities and their families had the supports they needed to pursue employment and post-secondary education. MDPs commitment to consistent and persistent engagement represented a shift from the more traditional or medical model of disability and public services, which is deficit focused. Whereas within PROMISE, MDPs embraced many aspects of the social model of disability, focusing on strengths of the persons and recognizing how environmental and social factors influence disability. In the PROMISE program, MDPs maintain a relationship with families and worked creatively to ensure engagement and maintain flexibility in order to augment likelihood of employment and post-secondary education success.

The third and final cross-lesson theme is collaboration. This theme is best described as complementary system integration. PROMISE youth and families may intersect with disability specific and public programs, beyond their participation in the SSI program, including housing, education, vocational rehabilitation, healthcare, child welfare, juvenile justice, food assistance, etc. These complex systems represent various eligibility, participation, and program requirements. Often times these programs do not coordinate or compliment with one another, leaving youth with disabilities and their families in a dizzying array of paperwork and expectations that can be impossible to translate. When survival is precarious, or when a youth or family is managing complex social, economic, or disability related challenges, complex public program requirements and rules can be a barrier to participation and engagement, thus youth and families can miss the benefits of a program or service due to a lack of coordination or system integration. The PROMISE design and MDP service delivery attempted to reconcile many of the system barriers that youth with disabilities and their families face by creating a more collaborative, integrated service model with employment, education and all services and supports working towards identified outcomes.

For long-term success to be achieved for both youth with disabilities and their families, service systems at the federal, state, and local level should be integrated and coordinated to support full participation, engagement, and benefits. The PROMISE model provides examples of how the systems can work collaboratively to support employment and education for youth with disabilities.

The document review also included important messages regarding the facilitators of good services, maximizing participation, the deep value of cross agency and federal and state partnerships, and committed leaders to guide systems change. In order to provide quality and coordinated services, a strong professional workforce is necessary, from case management to job coaching. Investments in these professionals provide the foundation for a strong service system. Individuals with disabilities can work and go to school with the right supports; a strong workforce can provide supports to enhance success and participation.

To expand youth and family participation in public programs that maximize outcomes (individual and system), services and supports at the federal, state, and local levels must maintain a youth/family focus centered on a youth’s individual needs and strengths. The face of disability will continue to change, and services can adapt to meet the changing needs of youth and families to incentivize employment and education with new and creative approaches.

Investments in cross-agency collaborations at the state and federal level can be fruitful and build more integrated and coordinated services to youth with disabilities and their families. Cross-system and agency partnerships are challenging, but can provide a significant benefit both at the individual and system level. The PROMISE model includes federal partners from Social Security, Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education. Additional partnerships with federal and state agencies were established and included: transportation, child welfare, juvenile justice, healthcare, housing, food assistance, mental health, and substance abuse. These partnerships were identified as adding value to youth with disabilities and their families to support securing employment, pursuing post-secondary education, and reducing the adverse impacts of poverty and disability. Committed leadership within federal, state, and local agencies provides the necessary structures and feedback loops to ensure services and systems are working together and making the most effective investments. Leadership and collaboration can go beyond budgets and memorandums of understanding to develop the long-term relationships needed to make system-wide improvements.

4.2Limitations

This manuscript was intended to provide an early and brief thematic introduction to lessons learned through the implementation of the PROMISE project. Future research and evaluation of PROMISE will continue to examine PROMISE activities and outcomes as they relate to system change and impact.

4.3Future directions

The PROMISE project ends on September 30, 2019, but the lessons learned and application of results and findings will have continued impact and relevance in the years to come. Future research, analysis, and evaluation findings will continue to be published from both federal and state agencies and provide new insights into evidenced-based best practices and strategies and significant elements of systems change. The overview in this paper will provide a foundation and focus for that future research. This will allow future analyses to delve deeply into the lessons that will have the most impact on future attempts at systems change.

4.4Conclusion

The PROMISE project was designed to test the impact and effectiveness of interventions to engage youth (ages 14–16) on SSI and their families to facilitate post-secondary education and employment. This large-scale model demonstration project will provide key evidence and information about evidence-based practices in the field for transition-age youth. The inclusion of lessons learned across the life the PROMISE project provide important factors and context about the structures, impact, and sustainability of PROMISE that can be used to inform future research, evidenced based practices, state-federal partnerships, and public policy.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

Acknowledgments

The contents of this paper were developed under a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, associated with PROMISE Award #H418P140002. Corinne Weidenthal served as the project officer. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the Department of Education or its federal partners. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any product, commodity, service or enterprise mentioned in this publication is intended or should be inferred.

References

1 | Blakely, C. H. , Mayer, J. P. , Gottschalk, R. G. , Schmitt, N. , Davidson, W. S. , Roitman, D. B. , & Emshoff, J. G. ((1987) ). The fidelity-adaptation debate: Implications for the implementation of public sector social programs. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15: (3), 253–268. |

2 | Breitenstein, S. M. , Gross, D. , Garvey, C. A. , Hill, C. , Fogg, L. , & Resnick, B. ((2010) ). Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Research in Nursing & Health, 33: (2), 164–173. |

3 | Brinkerhoff, R. ((2003) ). The success case method: Find out quickly what’s working and what’s not. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. |

4 | Fraker, T. , Carter, E. , Honeycutt, T. , Kauff, J. , Livermore, G. , & Mamun, A. ((2014) ). Promoting readiness of minors in SSI (PROMISE) evaluation design report. Center for Studying Disability Policy, Mathematica Policy Research. Washington: DC. |

5 | McLaughlin, J. A. , & Jordan, G. B. ((1999) ). Logic models: A tool for telling your programs performance story. Evaluation and Program Planning, 22: (1), 65–72. |

6 | Stockard, J. , & Wood, T. W. ((2017) ). The threshold and inclusive approaches to determining “Best Available Evidence:” An empirical analysis. American Journal of Evaluation, 38: (4), 471–492. |

7 | U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education Programs. ((2014) ). Application for new awards: Promoting the readiness of minors in supplemental security income (PROMISE) technical assistance center. CFDA 84.418T. |