Wisconsin PROMISE cost-benefit analysis and sustainability framework

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Promoting the Readiness of Minors in Supplemental Security Income (PROMISE) is a federal demonstration grant funded by the U.S. Department of Education in collaboration with Health and Human Services, Labor, and the Social Security Administration. Wisconsin PROMISE is one of six model demonstration sites.

OBJECTIVE:

This analysis was conducted to help illustrate the estimated costs and potential savings associated with supporting transition-age youth receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) achieve competitive, integrated employment.

RESULTS:

While not all youth achieve earnings at substantial levels, the research clearly indicates that providing opportunities for employment during the transition age years increases the likelihood of employment in adulthood. Additionally, youth with access to coordinated services and supports are more likely to be employed at higher rates, preparing them for improved employment and earnings trajectories into adulthood.

CONCLUSION:

Two options are presented, and the integration of employment-focused targeted outreach and case management and/or family navigator advocates is recommended for all transition-age youth receiving SSI and their families.

1Introduction

Research suggests that providing higher levels of employment-focused services to transition-age Supplemental Security Income (SSI) recipients can have positive impacts on earnings and employment that last beyond the period of service delivery (Fraker, Mamun, & Timmins, 2015). Youth with disabilities who have at least one paid work experience during high school are more than twice as likely to be employed after high school (Carter, Austin, & Trainor, 2011). Despite this data, employment rates among transition-age youth receiving SSIbenefits have remained low. Prior to PROMISE and implementation of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), only 13 percent of individuals ages 19 to 23 receiving SSI payments had received services from a state vocational rehabilitation agency, and only 22 percent were employed, compared with 69 percent for all young adults ages 20 to 24 (Rangarajan, Reed, Mamun, Martinez, & Fraker, 2009).

Regardless of the measure used, individuals with disabilities are significantly more likely to experience poverty than those without disabilities (Brucker, Mitra, Chaitoo, & Mauro, 2015). Scholarship regarding the intersection of disability, poverty, employment, and health is relatively recent although considerable interest is beginning to center on this growing population. Rehabilitation and disability researchers have noted the importance of contextualizing disability and integrating key constructs such as social determinants of health and other important elements into the employment discussion, particularly as they relate to the youth population (Anderson et al., 2018; Chan, Gelman, Ditchman, Kim, & Chiu, 2009; Edin & Kissane, 2010; Krahn, Walker, & Correa-De-Araujo, 2015). Researchers have also noted that annual income disparities of a few thousand dollars are associated with differences in cognitive function and increases in household income are associated with the greatest gains among the poorest children (Noble & Sowell, 2015). This underscores the critical importance of employment as an early intervention priority with youth populations, with a specific on those living with a disability.

Estimates from U.S. studies of publicly-funded vocational and on-the-job training programs show earnings increases ranging from $320-$887 per quarter (5–26% of earnings) and employment increases from 2–29 percentage points (Heinrich, 2018). And in terms of health correlations, aligned with social determinants of health criterion, individuals with disabilities receiving Medicaid benefits who are employed at any level have significantly lower rates of smoking, better quality of life, significantly higher self-reported health status, and lower Medicaid expenditures (Hall, Kurth, & Hunt, 2012).

The disparity in early employment experiences between youth with and without disabilities persists, and must be addressed using innovative approaches, particularly with youth and families living in low-income environments. Once youth are disconnected, there is no cheap and effective way to re-engage them in education, training and the workforce (Heinrich, 2018). Therefore, it is imperative for federal- and state-level policy makers, funders, researchers, and administrators to prioritize identification and services to this population as an early intervention strategy to improve employment, earnings, and health outcomes into adulthood. The national PROMISE demonstration was explicitly designed to test the implementation of evidence-based practices to help youth and families increase employment activity and ultimately increase overall household income and earnings, and reduce reliance on public benefit programs in a proactive and supportive manner. The analysis presented in this paper was designed to provide information regarding the estimated costs aligned with sustaining specific outreach and coordinated service options similar to those implemented during PROMISE based on the experience of one site, Wisconsin PROMISE.

2Methods

This analysis is intended to provide foundational information based on current administrative data and computations and was not designed as a comprehensive return on investment study grounded in advanced economic theory and methods. It is intended to provide applied information highlighting the annual costs (public benefits and services) associated with transition-age youth receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and the estimated benefits or cost savings that can be achieved by investing in varying levels of employment-focused service delivery, as demonstrated through Wisconsin PROMISE. The information may be useful to policy makers and program directors as they prepare to serve this population.

Using the base population of approximately 10,000 Wisconsin youth ages 14 to 181 receiving SSI, researchers first calculated (a) the expense of doing nothing. The cost of doing nothing was estimated by combining the average costs of (a) the federal SSI benefit using the annual amount of $9,007.46 per recipient in 2018, (b) SSI state supplement2 using the Wisconsin 2018 state supplement amount of $1,005.36 per recipient, and (c) Medicaid costs estimated at $14,521, 2018 average Wisconsin Medicaid payment, multiplied across the estimated number of transition-age youth in Wisconsin receiving SSI benefits. This calculation does not take into account other benefits the youth and/or their family may have been receiving due to low income, such as food, energy and housing assistance. Therefore, this is a conservative calculation and likely under-represents the actual cost of doing nothing.

Researchers then used cost and benefit data from serving just over 1,000 youth and their families in Wisconsin PROMISE to estimate the cost and savings of (b) targeted outreach to SSI youth and families, and (c) targeted outreach plus the addition of case management or family navigators who serve as advocates, multiplying these costs and savings to provide an estimate of the costs and savings for the full population of the approximately 10,000 age 14 to 18 receiving SSI in Wisconsin.

The first sustainability option involves targeted outreach to youth receiving SSI benefits and their families. This cost was estimated by adding the components required to conduct the targeted outreach including: (a) the cost to maintain interdepartmental state-level data sharing, (b) produce and mail 40,000 postcards annually, (c) staff time to administer postcard mailings, and (d) SMS text messaging. The second sustainability option presented includes the targeted outreach actions noted in the first option, plus the addition of case managers or family advocates who help teenagers receiving SSI and their families increase employment expectations and navigate transition services and supports. This cost was estimated by taking the total expense calculated for Option One and further adding the estimated targeted case management or family navigator staffing expenses, including: (a) salary, (b) fringe benefits, (c) travel costs, (d) overhead such as office space and supplies, and (e) staff training.

Benefits were calculated by first measuring the impact PROMISE outreach, case management, and family advocacy had on employment rates and wages. These employment rates, wages, and earnings above Substantial Gainful Activity (SGA) were then used to calculate both public benefits savings and tax revenue. Anticipated outcomes for sustainability option one, targeted outreach only, is analogous to the Wisconsin PROMISE control participants because of the consistent and persistent targeted outreach needed to recruit and enroll all participants (treatment and control) into Wisconsin PROMISE. Upon enrollment, youth and families assigned to the control group were provided with a list of transition resources PROMISE Intake Coordinators that were generally available in the community.

In comparison, anticipated outcomes for sustainability option two, targeted case management and family navigation, is analogous to the Wisconsin PROMISE treatment participants. These participants received the same targeted outreach as control group members however, once enrolled in Wisconsin PROMISE the youth and families were enrolled in Wisconsin’s Division of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR) and were automatically assigned a Wisconsin PROMISE DVR case manager. This case manager connected PROMISE youth and families to a local resource team, including a PROMISE family advocate. The PROMISE case manager and family advocate provided targeted case management and family advocacy, with the aim of raising expectations and supporting navigation of transition, disability, and poverty related services and supports across agencies (school, VR, job center services, long term care, mental health, foster care, juvenile justice, housing, transportation, energy, food, local community supports). Case managers and family advocates helped youth and families navigate systems and supports with the specific aim of connecting to services and supports that would help them reach their employment goals. Given that Wisconsin PROMISE was designed to automatically connect PROMISE youth and families to DVR, case management was employment-focused, and youth and family members could receive DVR and PROMISE-funded services to help obtain their employment outcomes through their Individual Plans for Employment (IPEs) or Family Service Plans (FSPs).

Based on the Wisconsin PROMISE enrollment rate of 33% of the eligible population after targeted outreach, and the 80% engagement rate of PROMISE youth and families in the treatment group, researchers estimated 2,640 Wisconsin teenage transition age youth receiving SSI and their families would engage in targeted case management annually. The cost of targeted case management was calculated based on a caseload size of 60 as this was the average caseload in Wisconsin PROMISE and Medicaid caseload sizes in Wisconsin are 50 to 75 on average. Smaller caseload sizes would be ideal, but smaller caseload size would increase the cost of this service. The cost of targeted case management was calculated by adding the cost of the salary and fringe benefits of a project director, regional case managers, case managers, travel, training, and an estimated overhead rate (office space, computers, smart phones, etc.) of 12%. Salaries and fringe rates were based on 2017 Wisconsin state employee salaries available to the public through Milwaukee’s Journal Sentinel.3 Based on Wisconsin PROMISE case manager travel, it is estimated that each of these employees would travel approximately 12,000 miles annually as a key part of their role in working with families in locations. The 12% overhead rate is consistent with the overhead rate used for Wisconsin PROMISE case managers, supervisors, and director. To ensure case management and/or family navigation is implemented with fidelity and efficiently, a training regimen similar to the one implemented in Wisconsin PROMISE is recommended. Trainings for Wisconsin PROMISE staff focused on employment focused youth and family centered case management, rapid engagement, motivational interviewing, trauma informed care, poverty, disability, and financial self-sufficiency. Training costs were estimated based on the Association for Talent Development’s 2014 State of Industry Report’s estimated training costs for less than 500 employees of $1,888 per employee (Association for Talent Development, 2014).

3Results

3.1The cost of doing nothing

Using 2018, it is estimated that the combined SSI, Wisconsin SSI state supplement, and Medicaid costs per individual average $24,534 annually. When multiplied across the approximately 10,000 transition-age teenagers in Wisconsin receiving SSI benefits, the total estimate is $245,340,000 annually.

3.2Option 1: Sustainability of youth employment services through targeted outreach only

Targeted outreach is critical in identifying and connecting transition-age youth receiving SSI benefits with employment supports using coordinated and systematic processes. All youth receiving SSI are eligible to receive Medicaid benefits in the state of Wisconsin. For this reason, Wisconsin Medicaid receives and maintains contact information for all Wisconsin youth receiving Medicaid because they are eligible through their federal SSI benefits. Targeted outreach regarding transition services and competitive integrated employment using postcards, emails, and text messaging to transition-age SSI youth in Wisconsin served as effective engagement techniques during PROMISE and are therefore recommended on an ongoing basis. The targeted population consists of youth age 14 to 18 receiving SSI benefits, and the postcards, text messaging, and emails should: (a) be designed in a youth-friendly manner, (b) provide a simple, positive message that employment is possible, and (c) provide web and phone contact information if further information is desired. Targeted outreach efforts should begin at age 14 to ensure youth are connected to Academic Career Planning at school and Post-Secondary Transition (PTP) planning services if youth has an Individual Education Program (IEP). At least two years prior to high school graduation, additional outreach efforts to better connect youth with the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR) and pre-employment transition services (services designed to prepare youth with disabilities for work) and/or other youth employment programs available through job centers, WIOA, local workforce boards, youth apprenticeships, schools, foster care, and local community employment programs is recommended. In addition, some postcards should provide information on other local services and supports that can help youth obtain their employment goals, including, but not limited to work incentive benefits counseling, financial coaching, transportation, assistive technology, self- and family advocacy, work-related social or soft skills, and health promotion. Each postcard should focus on one resource and/or message, so as not to overwhelm youth and families with too much information at once and to allow youth and families time to follow-up on the service. Table 1 identifies the costs associated with targeted outreach to transition-age youth receiving SSI and their families, including total cost for all transition-age youth as well as cost per individual youth. The estimated annual expense for Option 1 is $48,216 total or $4.82 per individual.

Table 1

Sustainability Option 1-Targeted Outreach

| Annual Estimated Costs: | |

| $18,000 | Maintain interdepartmental data sharing agreement between DPI, DVR and DHS |

| $18,298 | Produce and mail 40,000 postcards to SSI Youth ages 14 to 18 years old |

| $3,955 | Staff time to administer postcard mailings |

| $7,963 | SMS Text Messaging |

| $48,216 | Total Annual Estimated Cost (or $4.82 per individual) |

3.3Option 2: Sustainability of youth employment services through targeted outreach and case management or family navigator service coordination

In addition to targeted outreach efforts, this option also includes targeted case management or family navigators to help coordinate services and navigate systems. Again, based on the enrollment rate of 33% and engagement rate of 80% with PROMISE, we estimate that 2,640 youth will receive targeted case management and/or family navigation around transition from school to work. The focus of targeted case management or family navigators is to increase employment expectations and help with the navigation of transition services and supports to aid them in successfully obtaining their educational, employment, and financial self-sufficiency goals.

To provide targeted case management and/or family navigation to 2,640 teenagers receiving SSI and their families with an estimated caseload of at least 60 youth, 44 case managers or family navigators would need to be hired with a salary of $42,000 and an average fringe benefit rate of 1.4281. The project director’s salary is estimated at $78,000, and three regional supervisors would each have salary of $55,000 with the same fringe rate of 1.4281. Travel was estimated at 12,000 miles per employee with a state mileage rate of.535 per mile and the overhead indirect rate at 12% based on travel miles and overhead costs in Wisconsin PROMISE. Training costs at $1,188 per employee were also added to the cost estimate. Table 2 provides details on the costs associated with adding either targeted case managers or family navigators to the targeted outreach option and includes estimates on the total anticipated annual cost for the 2,640 transition-age youth as well as a cost per individual youth. The cost includes the cost of targeted outreach ($48,216), targeted case management project director ($111,392), three regional supervisors ($235,637), 44 case managers ($2,639,129), travel ($308,160), 12% overhead indirect ($395,318), and training cost ($57,984), totaling $3,795,836, a cost of $1,438 annually per participant. By setting up case management analogous to Wisconsin PROMISE, it is anticipated that outcomes from sustainability Option Two are similar to Wisconsin PROMISE Treatment group participants with 90% of youth engaging in at least one Wisconsin PROMISE or DVR Service, and 67% reporting wages in UI from April 2014 to September 2018.

Table 2

Sustainability Option 2-Targeted Outreach and Case Management or Family Navigator

| Annual Estimated Costs: | |

| $48,216 | Targeted outreach expenses (see Option 1) |

| $3,689,636 | Targeted case management or family navigator staffing (salary, fringe, travel, overhead) |

| $57,984 | Staff training |

| $3,795,836 | Total Annual Estimated Cost (or $1,438 per individual) |

It is important to note these costs are for targeted case management and/or family navigation only. This service can help increase expectations and connect youth and families to transition services and supports already available to transition age youth with disabilities. Estimates regarding the cost of these education, employment and financial self-sufficiency services and supports provided through VR, job centers, child welfare or poverty programs, schools, or community programs are not included in these cost estimates, as these are already being paid for through local, state or federal programs. For example, Pre-Employment Transition Services and employment services such as career exploration, paid work experiences, work incentives benefits counseling, soft skills training, self-advocacy training, and on-the-job supports are not included in the cost estimate as these are already budgeted for and offered through the Wisconsin’s DVR. With the advent of WIOA, public VR programs must prioritize a minimum of 15% of their annual service budget for serving youth and Wisconsin has consistently met or exceeded this requirement. In addition, state youth employment and training programs are required to serve out-of-school youth to ensure they are better connected to the workforce, and foster care programs are increasingly providing more employment supports to help youth in foster care, including those with disabilities, as they transition to adulthood.

To give an idea of possible employment supports that local programs may cover, the following information illustrates the fiscal contributions, including both DVR and PROMISE grant funds, spent on employment supports for Wisconsin PROMISE youth and their family members. The timeframe covers enrollment in Wisconsin PROMISE which started April 2014, through June 2019. Even following the end of PROMISE services on September 30, 2018, Wisconsin PROMISE youth continued to receive services through DVR, and PROMISE financial services continued through June 2019. Overall, service costs during this six-year period were $8,130,699 for 916 youth and their families or $8,876 per participant.4 These costs were divided by six to provide an annual service cost estimate of $1,479 per youth and their family. Types of services included work experiences (22% of the cost), training (14%), assistive technology (13%), job development including supported and customized employment (13%), financial coaching (10%), on the job supports (10%), pre-employment transition services including soft skills, self-advocacy and peer supports (6%), transportation (5%), work incentive benefits counseling (4%), assessment (3%), maintenance (1%), and other supports (1%).

Wisconsin PROMISE assistive technology and financial coaching costs were higher than typical because all Wisconsin PROMISE youth received an iPad, which accounted for the majority of the assistive technology costs, and Wisconsin PROMISE youth and family members could receive $1,000 of matched savings if they saved at least $250 in a PROMISE Individual Development Account (IDA) aimed to purchase an item to help them achieve their education, employment or financial self-sufficiency goals. In contrast, employment maintenance costs were less than typical because PROMISE youth were very early in their careers, and the focus was more on early work experiences than maintaining a career.

3.4Employment rates

With these targeted outreach and resource sharing efforts, 33% of control group youth applied for and received DVR services during the project, and their employment outcomes mirrored treatment group outcomes. When looking at the control group as a whole, 57% of control group youth had at least one quarter of employer reported wages in Wisconsin’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) data system from April 2014 to September 2018. In comparison, 51% of control youth who did not connect to DVR had a at least one quarter of wages reported during the same period, whereas targeted case management and family navigation helped to increase the percentage of youth with one quarter of reported wages to 67% of PROMISE youth in the treatment group.

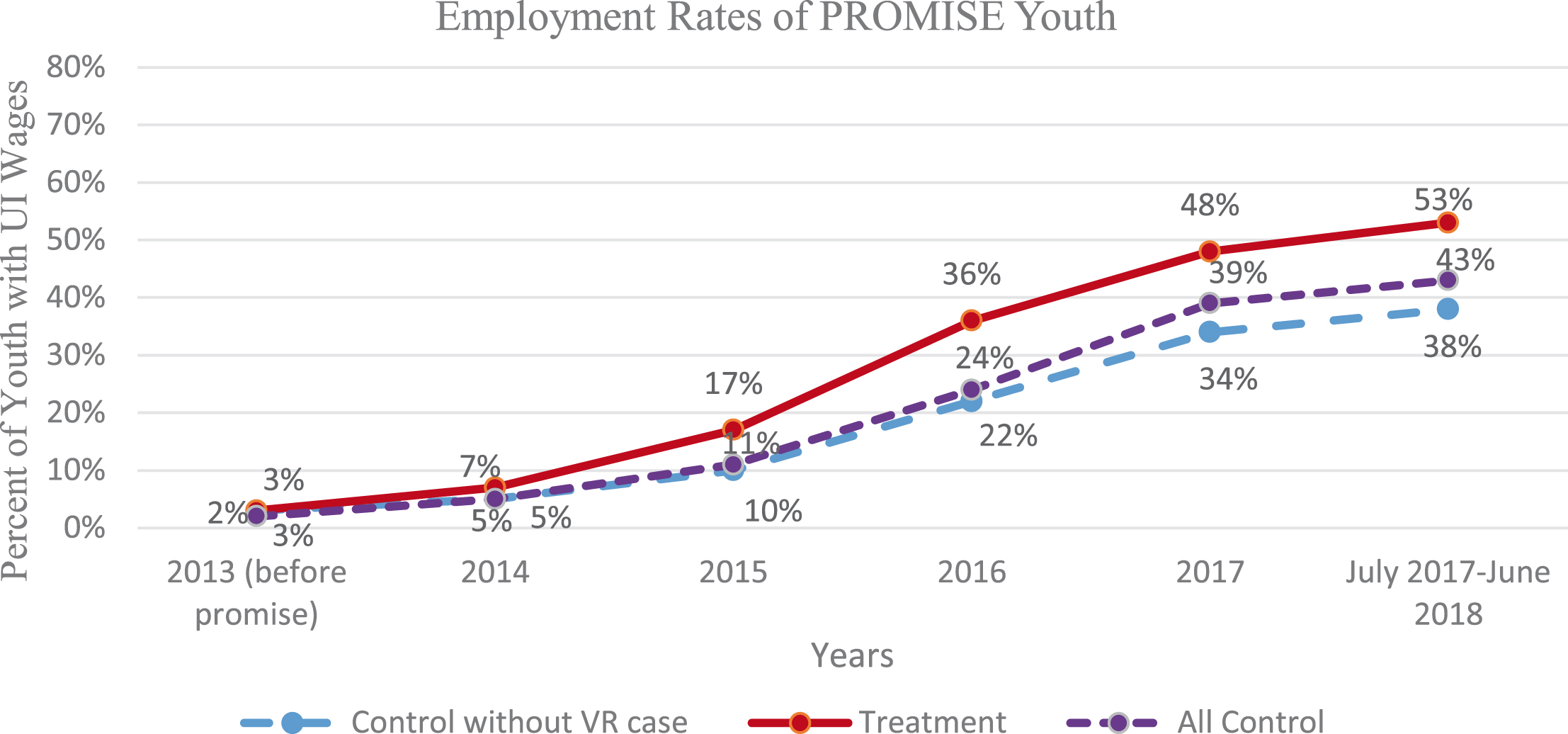

The earnings of the PROMISE Services (Treatment Group) youth participants averaged $3,313 annually. If earnings with the PROMISE Services youth population continue into adulthood at rates and levels comparable to the current DVR population (2017 Wisconsin Rehabilitation Council Annual Report), it is estimated that individuals will be working an average of 26 hours per week and earning an average of $12.94 per hour, or $16,822 annually. Figure 1 illustrates employment rates for youth in PROMISE, starting before the demonstration project was implemented through June 2018. Youth in the Treatment group had higher employment rates compared to all youth in the Control group and even higher employment rates when looking at youth in the control group without a DVR case.

Fig.1

Employment Rates of Wisconsin PROMISE Youth Between July 2017 and June 2018.

3.5Public benefits savings

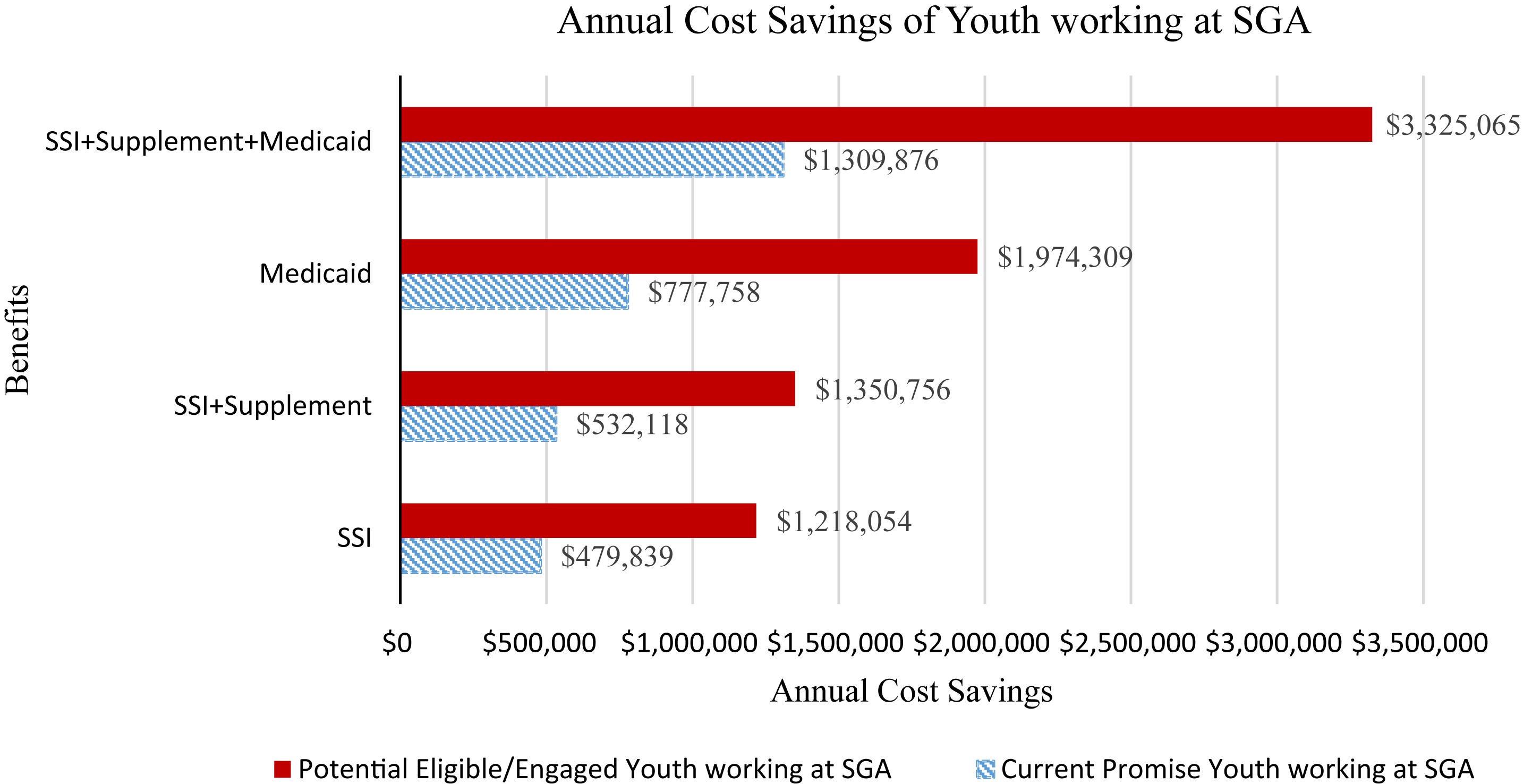

By September 30, 2018, five percent (52%) of the PROMISE Services population was earning at the Substantial Gainful Activity (SGA) level of at least $1,180 per month (https://www.ssa.gov/oact/COLA/sga.html). Even when earning SGA, youth can use work incentives to continue to receive their SSI and remain eligible for Medicaid. This is especially true for youth still in school (secondary or post-secondary), as they can use the student earned income exclusion (SEIE) to continue to receive SSI. That said, youth who earn SGA as a student are more likely to continue to earn this much or more as they age into adulthood and their training and work experience will increase their earning potential. Therefore, this five percent rate of SGA earnings was used as a projection to predict enough work and earnings to eventually work off benefits. Basic calculations highlighting potential cost savings are substantial. Figure 2 illustrates the annual combined cost savings of SSI, SSI+Supplement, and Medicaid if only 5% of youth are earning over SGA and no longer needing access to these public benefit programs. These savings are highlighted both as the 5% of the 1,012 PROMISE treatment youth and the potential 5% of the full 10,000 youth who could receive targeted outreach and targeted case management. These overall savings for SSI, state supplement, and Medicaid are $1,309,876/year for the 5% PROMISE youth currently earning SGA, and a projection of savings of $3,325,065 for the 5% of the approximately 10,000 Wisconsin SSI youth ages 14 to 18.

Fig.2

Youth Annual Cost Savings to Benefits.

3.6Tax revenue

The August 2018 Opportunities for People with Disabilities report from the National Governors Association noted that unemployment and underemployment, resulting in pay and income disparities for people with disabilities, is costly to states. Nearly $6.5 billion per year is forgone in state tax revenue nationally and the ongoing public supports provided to unemployed working-age people with disabilities costs at least $71 billion annually (National Governors Association, 2018).

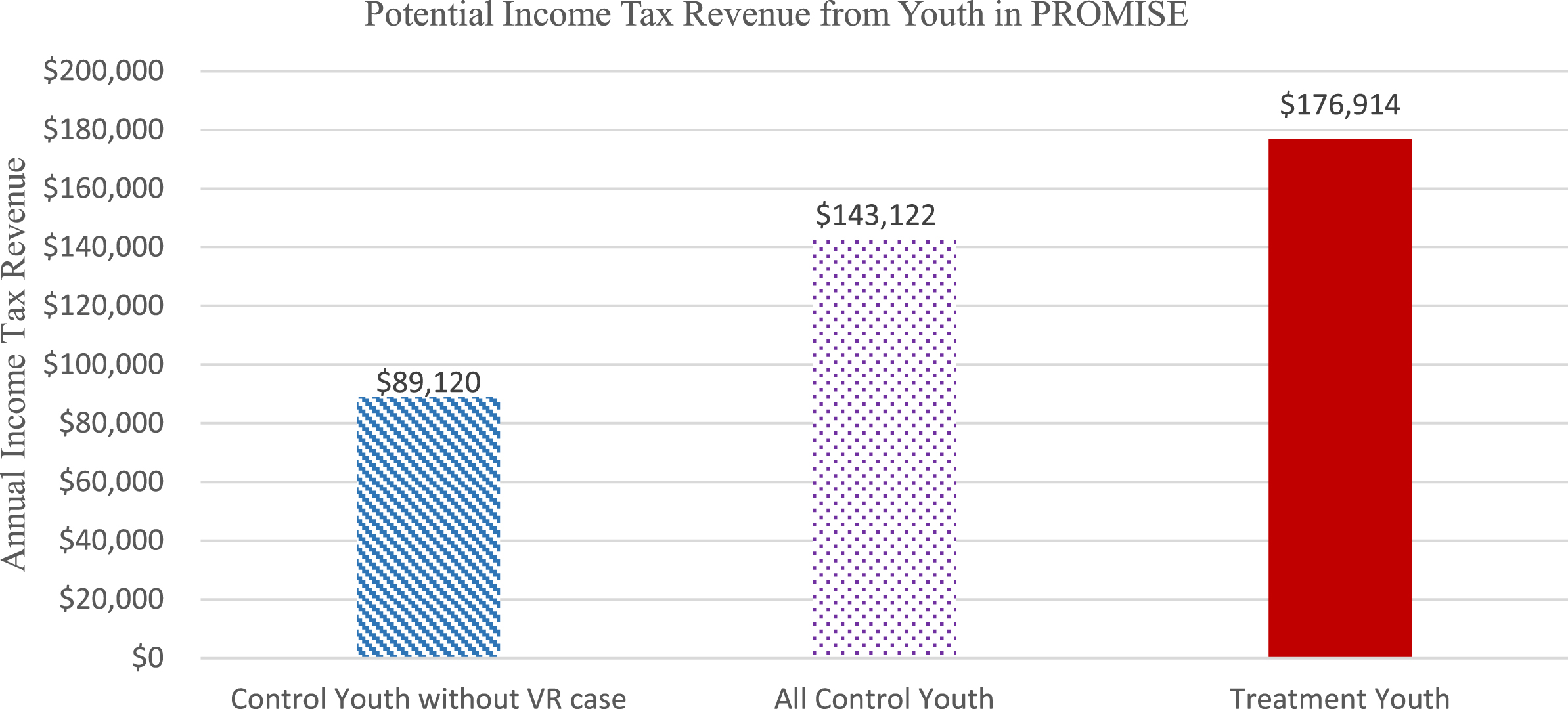

Between July 2017 and June 2018, 534 PROMISE Services youth (53%) who received targeted case management and family navigation were working at some point, earning an average of $3,313 annually. At a 10% federal income tax rate this equates to approximately $176,914 generated in federal income taxes. In comparison, during the same timeframe, 269 (38%) of PROMISE control youth without a VR case were working at some point. Assuming similar earnings of $3,313 annually and a 10% tax rate, this equates to approximately $89,120 generated in income taxes. Based on this logic, the PROMISE services youth generate approximately twice as much in tax revenue as those in the control group youth who never connected to DVR. Of note, targeted outreach to the control group did help connect 33% of control youth to DVR, so this targeted outreach did increase their annual tax revenue to $143,122, higher than the control group members who did not connect to VR, but lower than the treatment group who received targeted case management. Figure 3 demonstrates the potential income tax revenue from SSI youth working for doing nothing, providing targeted outreach, and providing targeted case management and/or family navigation.

Fig.3

Potential Youth Income Tax Revenue.

3.7Current engagement in services

Medicaid. All youth were receiving Medicaid because of their SSI when they first enrolled in Wisconsin PROMISE, but not all were receiving case management services. More specifically, at enrollment 10% received Children’s Long Term Care Services (CLTS), 3% received Mental Health Wraparound Services (Wraparound Milwaukee or Children Come First), 3% received Comprehensive Community Services (CCS) or Community Support Programs (CSP), 4% received crisis intervention, 11% were receiving other mental health services, and 2% were receiving Medicaid Targeted Case Management. Wisconsin PROMISE case management and family navigation helped connect more youth to long term care services, so that by the end of PROMISE services, long term case management increased from 10% at enrollment to 22% at the end of the service period.

Schools. Most, but not all Wisconsin PROMISE youth had an IEP. At enrollment, 84% of Wisconsin PROMISE youth had an IEP. Even when youth had IEPs, they sometimes still had trouble connecting with school due to truancy or discipline related issues. School attendance at initial enrollment was lower than originally anticipated, with 65% of PROMISE youth attending school at least 90% of the time. Just as attendance was lower than anticipated, suspension (39%) and expulsion (1%) rates were higher than anticipated. In addition, 20% of PROMISE youth and families specifically asked their PROMISE Family Advocate for help with IEP related issues. With targeted case management, 67% of PROMISE youth had a school person identified as part of their resource team. This inter-agency collaboration improved services, and youth had a higher employment rate when a school person was identified as part of the Wisconsin PROMISE resource team.

Division of Vocational Rehabilitation. Prior to PROMISE, only 1% of youth 18 and younger receiving SSI and 13% of youth 19 to 23 receiving SSI had received services from a state vocational rehabilitation agency (Rangarajan, Fraker, et al., 2009; US GAO, 2017). In contrast, 33% of youth in the Wisconsin PROMISE control group (targeted outreach) and 100% of the youth in the Wisconsin PROMISE treatment group (targeted case management and family navigation) received services through DVR. It is important to note that it may not be possible to connect all youth to VR services in every state, especially in states with a waitlist. That said, targeted case management or family navigation could connect youth to other employment services available through job centers, workforce boards, school, apprenticeships, internships, child welfare, or other local programs.

4Discussion

While public benefits provide important income and resource supports, it is critical that youth with disabilities also have the opportunity to increase their financial independence by reducing reliance on these benefits through meaningful work and earnings. Targeted outreach is critical in ensuring all youth have this opportunity by identifying and connecting to transition-age youth receiving SSI benefits with employment supports using coordinated processes. Targeted outreach through postcards, emails, and text messaging to transition-age SSI youth in on a quarterly basis starting at age 14 is recommended to promote connections to Academic Career Planning at school and Post-Secondary Transition Planning (PTP) if youth has an IEP. At least two years prior to high school graduation, additional outreach to better connect youth with the DVR and pre-employment transition services (services designed to prepare youth with disabilities for work) is recommended.

In addition to targeted outreach efforts, use of targeted case management or family navigators for those receiving SSI benefits is a crucial component to ensure youth and family engagement and success in VR or other available local employment services and employment. The focus of targeted case management or family navigators is to increase expectations around employment, connect youth and families with services and supports, and help families navigate the systems designed to aid them in achieving their education, employment, and financial self-sufficiency goals.

5Conclusion

Sustainability Option 2 (targeted outreach and case management and/or family navigation) is recommended for youth in transition receiving SSI and their families based on the lessons learned through Wisconsin PROMISE. The anticipated outcomes from the targeted outreach and case management include increased VR engagement, higher employment rates contributing to increased financial independence, and increased tax contributions and employment in adulthood. Federal and state SSI benefits and Medicaid serve as key financial, health, and service supports for many youth with disabilities and their families. This analysis is not intended to suggest that all youth must work off public benefits as many may need to retain access to these supports to reside and work in the community as adults. However, increased employment reduces dependence on public benefits overall and more can be done from a coordinated systems perspective to intentionally connect these youth with information and resources around competitive integrated employment and provide supports to both youth and their families. The costs associated with implementing either of the sustainability options presented here are relatively minor when considered against the potential costs of public benefits to individuals, families, communities, and systems longer-term without earned income to help offset the cost. A longitudinal study examining the impact of early youth employment interventions to costs in the state Medicaid system and the resulting health, well-being, and poverty data would serve as an interesting extension to this preliminary analysis.

Conflict of interest

None to report.

References

1 | Anderson, C.A. , Hergenrather, K. , Johnston, S.P. , Tansey, T. , Keegan, J. , & Estala-Gutierrez, V. ((2018) , April). Social determinants of health: Addressing inequities through informed rehabilitation research and practice. Presented at the 18th Annual National Rehabilitation Educators Conference, Anaheim, CA. |

2 | Association for Talent Development. ((2014) ). State of the industry report. Retrieved from https://www.td.org/research-reports/2014-state-of-the-industry. |

3 | Brucker, D.L. Mitra, S. , Chaitoo, N. , & Mauro, J. ((2015) ). Working-age persons with disabilities in the United States. Social Science Quarterly, 96: , 273–296. |

4 | Carter, E.W. , Austin, D. , & Trainor, A.A. ((2011) ). Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23: , 50–63. |

5 | Chan, F. , Gelman, J.S. , Ditchman, N. , Kim, J.-H. , & Chiu, C.-Y. ((2009) ). The World Health Organization ICF model as a conceptual framework of disability. In F. Chan , E. Da Silva Cardoso , & J.A. Chronister (Eds.), Understanding psychosocial adjustment to chronic illness and disability: A handbook for evidence-based practitioners in rehabilitation (pp. 23–50). New York, NY, US: Springer Publishing Co. |

6 | Edin, K. , & Kissane, R.J. ((2010) ). Poverty and the American family: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72: , 460–479. |

7 | Fraker, T. , Mamun, A. , & Timmins, L. ((2015) , April). Three-year impacts of services and work incentives on youth with disabilities. (Issue Brief). Retrieved from https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/threeyear-impacts-of-services-and-work-incentives-on-youth-with-disabilities. |

8 | Government Accountability Office ((2017) , May). Supplemental security income: SSA could strengthen its efforts to encourage employment for transition-age youth (GAO-17-485). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. |

9 | Hall, J. , Kurth, N. , & Hunt, S. ((2012) ). Employment as a health determinant for working-age, dually-eligible people with disabilities. Disability Health Journal, 6: (2), 100–106. |

10 | Heinrich, C. ((2018) , September). Increasing work participation and returns to work. Presented at the Annual Poverty Research and Policy Forum, Madison, WI. |

11 | Krahn, G.L. , Walker, D.K. , & Correa-De-Araujo, R. ((2015) ). Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. American Journal of Public Health, 105: , Supplement 2, S198–206. |

12 | National Governors Association. ((2018) ). States expand employment and training opportunities for people with disabilities. Madison, WI. Retrieved from https://www.nga.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/EO-Publication-Opportunites-for-People-with-Disabilities-August-2018.pdf. |

13 | Noble, K.G. , Houston, S.M. , Brito, N.H. , Bartsch, H. , Kan, E. , Kuperman, J.M. ,... Sowell, E.R. ((2015) ). Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nature Neuroscience, 18: (5), 773–778. |

14 | Rangarajan, A. , Reed, D. , Mamun, A. , Martinez, J. , & Fraker, T. ((2009) ). The Social Security Administration’s youth transition demonstration projects: Analysis plan for interim reports. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research. |

15 | Rangarajan, A. , Fraker, T. , Honeycutt, T. , Mamun, A. , Martinez, J. , O’Day, B. , & Wittenburg, D. ((2009) b). The Social Security Administration’s youth transition demonstration projects: Evaluation design report. Available from www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_576.pdf. |

Notes

1 This age range of 14 to 18 was targeted for this analysis because youth had to be 14 to 16 to enroll in PROMISE, and the enrollment period lasted two years, so some youth who enrolled at 16 were 18 by the end of the enrollment period.

2 Recipients of federal SSI benefits residing in Wisconsin also receive a supplemental state payment https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.NSF/lnx/0501730010CHI.

3 https://projects.jsonline.com/database/2018/2/Wisconsin-state-employee-salaries-2017.html

4 It is important to note that Wisconsin PROMISE could fund services that aided both youth and their family members to meet their employment goals, so while most costs covered employment services for the youth, some of the costs per youth were for employment services for their family members.