Creating an Employment Collaborative

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

With the passage of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014 (WIOA), and its explicit emphasis on Federal, State, and local collaboration, a need for innovative and effective strategies for effectuating efficacious collaborative methodologies seems apropos. This APSE presentation briefly discusses both old and new methodologies for job development, and displays one collaborative approach that can be utilized in holding fidelity to a dual-customer approach for employment services for individuals with disabilities, and meeting WIOA requirements.

OBJECTIVE:

Identify the unique ways in which a collaborative network of employment service providers and other key stakeholders servicing the Northeast Ohio Area developed and improved employment outcomes for both businesses, community partners, and job seekers with disabilities, and identify how the implementation of this type of collaborative partnership can better support a demand-side approach to the business engagement component of job development, and the supply-side matching efficiency of job seekers for the person-centered components of job development.

CONCLUSIONS:

The collaborative model expressed, and the associated guiding principles, have shown promise and effectiveness in bringing stakeholders from a variety of perspectives together. Further, it has displayed an increase in successful employment outcomes for people with disabilities. Lastly, while the examples put forth have been tailored to serve the unique population and geography of the region identified, the authors assert that implementing a collaborative strategy similar and in congruence with the model would be beneficial to any.

1.Introduction

Since the late 1970s, the broad field of services for Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IWIDD) has progressively and more formally implemented the concept of person centered planning (O’Brien & O’Brien, 2000; 42 U.S.C. §441, 540). While the funding for employment services has followed along such a person centered approach, being both structured around and tied to the individual being served, far less focus has been placed on meaningfully serving the business community as an equal customer. Add to that the consideration that for almost three decades now, national estimates of the number of IWIDD working in integrated employment settings has observed little growth, and the fact that IWIDD continue to experience under-employment and unemployment rates higher than their non-disabled peers, and one begins to wonder if the connection between the disability services field and the business community is being sufficiently addressed (Butterworth et al., 2015; Francis, Gross, Turnbull, & Turnbull, 2014).

From a planning perspective, Person-Centered Planning seems prudent, even essential in supporting individuals to live meaningful lives in ways that are both important to and important for them. Yet, with an emphasis placed on more community integrated services; this value orientation, coupled with a funding structure derived from it, seems to give way to unintended consequences. The byproduct of the heightened emphasis placed on helping the individual to access their community is an oversight in helping the community to be accessible to the individual. Both seem prudent, yet the unequal distribution placed on the former over the latter gives little time to service providers, and others directly supporting individuals, to actually engage the community. Moreover, it incentivizes providers of service to work against one another rather than in collaboration with one another. Nowhere is this more problematic than in the employment services arena, where academic evidence clearly articulates that inadequate/poor collaboration acts as a barrier to employment (Francis, Gross, Turnbull, & Turnbull, 2014), substantive business/employer engagement leads to successful employment outcomes (Haines, et al., 2017), approaching the community as an equal customer is best practice and critical in supporting job seekers towards successful employment (Del Valle et al., 2014; Wehman, Revell, & Brooke, 2003), interagency collaboration is an evidence based best practice that leads to successful outcomes (Test, Mazzotti, Mustian, Fowler, Kortering, & Kohler, 2009), and defined collaborative models and roles are needed (Butterworth, Christensen, & Flippo, 2017).

It then seems self-evident that by failing to sufficiently represent a customer either equally or equitably, that customer will not only feel neglected but poorly served. To underscore this, businesses and employers have identified challenges related to finding qualified candidates, and accessing services from Employment Service Providers (ESPs) (Domzal, Houtenville, & Sharma, 2008; Kessler Foundation, 2017). Additionally, while employers have noted the importance of establishing trust and credibility in developing and maintaining effective working relationships with ESPs, the field of employment services has inconsistently trained and implemented established best practices (Butterworth et al., 2015; Simonsen, Fabian, Buchanan, & Luecking, 2011). For trust and credibility to be achieved, a single ESP connecting with a business must not only be capable of spending the appropriate amount of time and energy necessary to cultivate an effective relationship, they must also be capable of providing an authentic attempt toward meeting the business need. In a pragmatic sense, ESPs must have access to enough job seekers to properly supply qualified and interested job seekers to businesses, find the time to cultivate and maintain both current and new business relationships, and continue to address the day to day needs of a full caseload.

Adding to the concerns around effective business engagement is the problem of competition, and a Competition Over Collaboration Paradigm. The current employment services system has undoubtedly created a competitive culture among ESPs. Funding for ESPs being tied to only those individuals directly served, makes ESPs more inclined to focus on only those individuals that their organization is actually serving; and building a positive reputation among case managers planning for employment services to ensure future agency sustainability. Thus, ESPs have an inherent interest in getting their job seekers hired by employers at the expense of holding an interest in employers accessing the most qualified and appropriate candidates. ESPs may then be far more likely to push their candidates to businesses, as opposed to asking businesses what are their unique needs, and what types of applicants are they looking for. In the end, the silo service delivery model that a competition over collaboration paradigm creates, gives way to the inability of the very staff charged with engaging businesses, to access candidates beyond a single caseload and most effectively support businesses as a true customer.

So how are local stakeholders supposed to navigate these barriers and bridge the gap between the service paradigm, and the community? One method for better supporting the business community while still holding fidelity to person centered service delivery and funding limitations, is creating a more viable and efficacious collaborative model. By developing a tangible and pragmatic way to coalesce partners assisting job seekers with disabilities, and thereby aggregating all potential applicants into an easier accessible candidate pool, the county of Cuyahoga, located in Northeast Ohio, thru its development of the Employment Collaborative of Cuyahoga County (ECCC), has engendered a way to equally and equitably support: individuals seeking employment, ESPs supporting individuals, and the business community as a customer.

2The Employment Collaborative of Cuyahoga County

2.1Origin

In order to begin creating a positive collaborative with area employment service providers it was important to start with those regionally based providers that were more willing to connect and collaborate. We heavily considered the psychological principal of “Threshold Models for Collective Behavior” when beginning to form the group (Granovetter, 1978). The idea behind this theory is that people’s willingness to choose between one option and another, in this case the option to collaborate or compete, lies on a continuum. When attempting to initiate a collaborative it was important to start with providers and specifically provider staff that displayed a low threshold for change of habits and expressed interest in collaboration over competition. We identified those staff and providers by reaching out and asking if they would be interested in even discussing the possibility of working collaboratively. Providers that had more of a proclivity towards collaboration became early participants. Those providers that had a higher threshold for collaboration, and consequently, a stronger proclivity towards a competitive model were addressed once a more formalized group had been developed.

In 2014, with the intent to capitalize on sharing information and resources with outside entities capable of benefiting from said information and resources, the Cuyahoga County Board of Developmental Disabilities (CCBDD), initiated early conversations that gathered professionals for coffee, and facilitated open discussions and perspective sharing. As relationships began to develop, advancing conversations to more substantive topics such as: job lead and candidate sharing, employment services best practices, challenging cases, and staff training and professional development issues, became more approachable and apropos. The group developed into a democratic collaborative model where all changes and proposals were voted on by all members, which for pragmatic purposes, eventually further expanded into members voting in elected representatives that could make decisions on behalf of the group. The group further agreed upon bi-monthly meetings that rotated locations to accommodate partners from different area. The group also acknowledged the continued opportunity for any ESP to act as facilitator if the ESP formally expressed such a desire and could establish an ability to perform the functions of the facilitator.

By starting small with less than 5 members at informal and network orientated meetings, and including every participants input, a strategy centered on working cooperatively and sharing employer contacts and job leads emerged. Early collaboration efforts in 2014 yielded two successful placements in in which one partner shared a business connection that lead to an offer for employment to a job seeker served by a separate partner.

2.2Expanding the model

As partners began to experience success through working together, the desire to formalize the interactive process became necessary. The group worked together to establish a name, the mission, vision and values of the member, and the ways in which members would communicate and share resources (See appendix A). Concerns eventually started to arise around the problem of equal participation. Several partners started to recognize other partners’ involvement, or more directly, lack of involvement. In holding true to established values, all members that wished to address the issue were given the opportunity to develop policies and procedures that could be utilized to account for unequal or unequitable participation. Even at the expense of the effort, this type of more formal policy and consequence development, helped to further coalesce the group. This observation aligned directly with findings on altruistic punishment and engendered cooperation noted in behavioral economics research (Fehr, & Gächter, 2002).

Out of these discussions, another key construct materialized: the role of facilitating the group was essential to the groups operation. Consequently, the role of facilitator needed to be further clarified and spelled out (see appendix B). By 2015, with working agreements in place, and the CCBDD acting as facilitator, the group had pulled in additional partners and tripled in size. The majority of the areas ESPs were now willing to come together and discuss how to improve efficiency and efficacy, yet the outcomes attributable to collaborative sharing were still minimal at best with 5 total job placements observed at years end.

While the group continued to share information electronically the following year, the addition of a Hiring Event (HE) to the ECCCs sharing practices in 2016 changed the entire trajectory of the group. Calling them hiring events was purposely done to differentiate them from what most people refer to as a job fair, and the ways in which a job fair operates. Although there were some similarities between a HE and a traditional job fair, a HE required unique consideration in implementation (see appendix C), and in turn, uniquely brought businesses to the table ready to conduct on site interviews for specific positions. Area employers were directly targeted by ECCC partners and encouraged to attend with the goal of conducting interviews to fill open positions. When an employer stated that they would be interested in attending such an event, the ECCC partner staff began gathering information about the business and the openings they were seeking to fill. In gathering this information prior to the event, and sharing it amongst ECCC partners, the group was better positioned to match the appropriate job seekers to the most appropriate businesses in attendance, and streamline the process for both parties. Job seekers were now capable of meeting face-to-face with multiple businesses that match their interests, goals and skills. Concurrently, the businesses were afforded quicker access to a more manageable and qualified candidate pool.

The HE became a tangible example of how the ECCC views collaboration in concept. It provided partners in the ECCC a way to see the results that could be achieved with collective input. By hosting a HE and having participating partners contribute through either bringing a business or volunteering, it reinforced the notion that with just a little bit of input from a collection of partners, the overall opportunities for positive outcomes could increase substantially. Partners had the ability to directly observe how their minor contribution had granted them greater access to employers and meaningful business connections. The physical representation of collaboration also appeared to help assuage reservations held by other potential partners that had expressed skepticism and a reluctance to collaborate. Additionally, the events displayed ESPs efforts in supporting business needs, and presented a clear message of customer service to the business community. The term Hiring Event was even salient, messaging to the business community even in name, that the event is being put on for them. This type of marketing strategy not only aided in attendance, but afforded ESPs a more open dialogue with business not previously engaged. The impact and success of the first two HEs put on in 2016 contributed to a yearend total placement number of 57 job seekers, and led to decision to put on a total of four in 2017, with plans for even more in upcoming years.

2.3A potentially promising approach

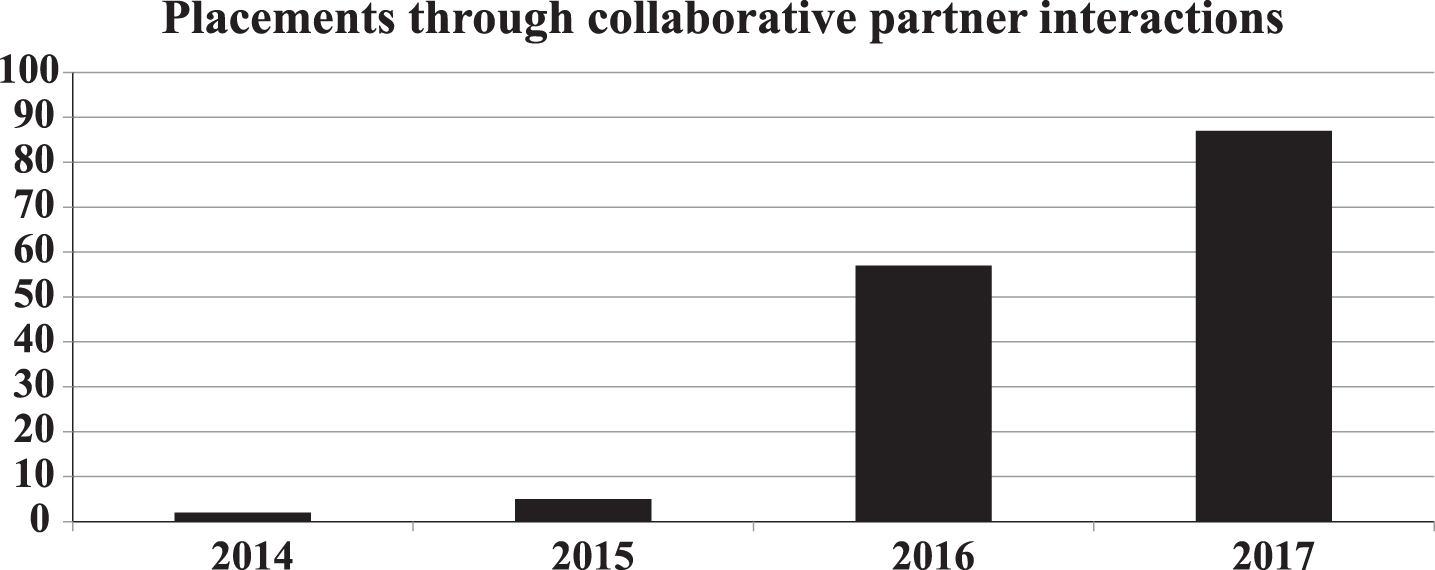

As the group continued to expand, so too did the challenges. However, with those challenges, came more opportunities, and more successful outcomes. Throughout 2017 the group continued to solidify its presence regionally. Four HE combined with periodic sharing of email distributed job leads resulted in 187 unique employment opportunities being disseminated amongst the group. Those 187 job leads led to 87 individuals finding competitive integrated employment (see Table 1, Fig. 1). Local TV and Radio news channels also took notice and reported multiple times on the HEs and the ECCC. As word of mouth spread the ECCC successes, more and more ESPs and other community organizations displayed an interest in joining the group. At the end of 2017 there were 38 community partners included in the ECCC. A little more than half of the partners were ESPs. The rest were made up of state, and local public entities involved with the workforce development system, local educations agencies, and other non-profit organizations that had identified a desire to participate. Partners that were not direct service providers began to contribute in other indirect ways such as volunteering at HEs, offering venue space, and participating with ECCC subcommittees.

Table 1

Placements through collaborative partner interactions

| Year | n | % of Grand Total |

| 2014 | 2 | 1% |

| 2015 | 5 | 3% |

| 2016 | 57 | 38% |

| 2017 | 87 | 58% |

| Total | 151 |

Fig.1

The growth of job placements by collaborative partners over the lifespan of the ECCC.

3Conclusions

The upfront work of creating a networked system of employment services providers in a collaborative format allows employment staff in the area to change the messaging to the business community. Typically, when ESP staff are working with an individual or even a small caseload of individuals, the conversation with a business tends to lead to requests being asked of the business. Such as asking the hiring manager to pull an application, interview a candidate, participate in a community based assessment or directly hire an applicant. By approaching businesses with this type of messaging the burden of action falls squarely on the business and the hiring manager. The ball is placed in their court with the request to action placed solely on their hiring department. Unfortunately, this type of interaction fails to support the business as a customer, and sets up the expectation that the business must support the job developer in their need to place a specific individual. In turn this can perpetuate a cycle of job developers consistently requesting assistance from businesses that have hired candidates in the past. This type of one sided relationship can be difficult to maintain over a long period of time. The end result becomes the unfortunate utilization of a business engagement strategy that is in direct opposition to the dual customer model of business engagement as defined in the literature (Dell Valle et al., 2014; Holland, 2016; Simonsen, Fabian, Buchanan, & Luecking, 2011; Wehman, Revell, & Brook, 2003).

When approaching businesses in this manner the scope of what staff can do in regards to assisting in the hiring process is limited. By requesting specific information on the status of certain job openings or of certain applicants, businesses can often get around your request with blanket statements about having no control over interview selections, corporate rules in hiring practices, positions being closed, etc. Most of these responses from businesses are to avoid what the business perceives as a more complicated process to their typical hiring. By aggregating the local talent pool employment services staff can approach businesses offering to assist in any aspect that would lighten the load for a hiring manager. Starting with open ended questions to businesses that inquire on which positions they currently have available, which positions frequently open, and the types of candidates they typically seek, allows ESPs to offer assistance to business in filling open positions and support in solving workforce needs. The responsibility and burden has now shifted from the hiring manager/business to the employment services staff. The business now has the potential to see ESPs as an asset and resource rather than a burden.

To hold any sort of fidelity to a true dual customer approach to business engagement, ESPs must work to shift the burden from employers to themselves. Yet, without a mechanism in place to sufficiently address such a burden, ESPs may potentially be hard pressed to meet employer and business needs over the long term, and leave them feeling unsatisfied and poorly served. A collaborative network of ESPs and other appropriate community stakeholders intentionally and strategically engaging the business community may present a more viable methodology for effective business engagement than any single ESP can provide in isolation. The authors posit that a collaborative network focused on keeping lines of communication between partners open, cooperatively approaching shared goals/objective, and incorporating an authentic demand side approach to business engagement, can best support job seekers with disabilities obtain successful employment outcomes.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix ACollaborative group framework considerations

Logistics

If your informal meetings continue to head in a positive direction the next step is discuss with the collaborative partners about a forming a more formalized group. Below are a few areas of focus that can help provide early structure to the group. Things to try and assess would be:

• Identifying outcomes (see attachment 1)

∘ Mission / Vision / Values

∘ Goals and Objectives

• Partners

∘ What agencies in your region should we reach out to?

∘ Who should be assigned to reach out to those agencies?

∘ Are there agencies we want to target or avoid?

• Roles – what interests and expertise do certain partners have that they would be willing to take on? (See attachment 2)

∘ Facilitator

■ create meeting agendas

■ track leads

■ collect data (See attachment 2 for descriptions and examples)

■ facilitate communication internally and externally for group

∘ Membership

■ recruit new partners

■ onboard and orient new members to group as

■ track member input and output from group

∘ Events

■ schedule meeting space

■ plan and execute hiring events or fundraising events

∘ Training

■ take training interests from the collective group,

■ schedule speakers

■ create training sessions or conferences

• Logistics

∘ Meetings

■ Weekly/Monthly/Quarterly/Etc.?

■ Consistent meeting space or transition between partner spaces?

∘ How will job leads and information be shared?

■ Email/Database

∘ Information sharing

■ How to I bring a job lead to the group?

■ How to I submit a candidate for a job lead seen from the group?

∘ Decisions

■ How will disputes be handled?

■ How will we make decisions?

• Votes/Panel/Leadership

Appendix B

Appendix BECCC’s facilitator’s role includes:

• Manage all job leads and applicants submitted by ECCC Partners

• Track data from ECCC

∘ Leads submitted

∘ Applicants submitted

∘ Interviews + Hires from hiring events and leads

• Manage ECCC budget + accounts payable

• Organize and Facilitate bi-monthly meetings

• Report out minutes from all committee and bi-monthly meetings

• Oversee committees and roles to ensure functionality of the ECCC

The ECCC also created a streamlined model for sharing job leads in the area that follows:

• The partner that has a competitive community job lead sends information to the collaborative facilitator an email with details on the position such as:

∘ Business information – Name, Field, Address, Previous relationship

∘ Job type

∘ Job Duties

∘ Hours and schedule

∘ Pay

∘ Information on how to apply

• See attachment 5 – ECCC no longer uses this document but framework for emails

• Collaborative facilitator forwards email to all collaborative partners

• Each collaborative partner reviews job lead and assesses the job seekers within their agency for qualified applicants

• Collaborative partners that have a qualified applicant complete the application steps outlined in the email sent out by the collaborative facilitator

• The Collaborative facilitator holds all potential candidates and forwards them to the collaborative partner that submitted the job lead

• The partner that brought the lead reviews applicants from other partners and forwards those on to their business connection in efforts to secure interviews and placements

Appendix C

Appendix CHiring event considerations

1. Venue procurement – by collaborating with partners accessing potential sites can often be done for little to no cost

a. Does a partner in the collaborative have space in their own agency to host event

b. Government Buildings

i. Local County Board

ii. Local OOD Office

iii. Ohio Means Jobs Office

iv. Libraries

c. Business partner

i. Restaurant before they open that has meeting space

ii. Corporation with large or multiple meeting space(s)

iii. Chambers of Commerce

2. Business recruitment

a. Creating a flyer to invite employers (see attachment 6)

b. Create document or google document for staff to register businesses that have verbally/in writing agreed to attend and recruit candidates (see attachment 7)

i. Business name

ii. Location

iii. Positions they are recruiting for

iv. Instructions on how to apply prior to event for job seekers

c. Discussion with partners on targeted business outreach

i. Assign various providers to certain businesses or business regions to avoid overlap and business fatigue

d. Create google doc or registration form for participating partners to register job seekers for businesses attending

i. Create guidelines for what participation is

1. Bring a business in order to bring job seekers

2. Recruit X number of businesses in order to bring job seekers

3. Volunteer day of event in order to bring job seekers

e. Those partners that have contributed to the planning and execution of each event can then register job seekers being served by their agency for appropriate businesses planning to attend

f. Event execution (See attachment 8)

i. Set up – 5 to 6 volunteers

1. Set up of table and chairs

2. Table tents identifying businesses in attendance

ii. Job Seeker registration – 2 to 4 volunteers

1. Signing in job seekers that have pre-registered to attend

2. Making name tags

3. Getting photo/consent forms signed

4. Directing job seekers to waiting room or employer room

iii. Business registration – 1 to 2 volunteers

1. Sign in businesses in attendance

2. Escort them to their table

3. Go over event process and procedures

4. Answer any questions

iv. Runners – 3 to 4 volunteers

1. Work with job seekers and escorting them to the businesses they have registered for

2. Assist job seekers with navigating event

3. Helping job seekers with interview questions

References

1 | Butterworth, J. , Winsor, J. , Smith, F. A. , Migliore, A. , Domin, D. , Ciulla Timmons, J. , & Hall, A. C. ((2015) ). State Data: The national report on employment services and outcomes. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion. |

2 | Del Valle, R. , Leahy, M. J. , Sherman, S. , Anderson, C. , Tansey, T. , & Schoen, B. ((2014) ). Promising best practices that lead to employment in vocational rehabilitation: Findings from a four state multiple case study. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 14: , 99–113. |

3 | Domzal, C. , Houtenville, A. , and Sharma, R. ((2008) ). Survey of Employer Perspectives on the Employment ofPeople with Disabilities: Technical Report. (Prepared under contract to the Office of Disability and Employment Policy, U.S. Department of Labor). McLean, VA: CESSI. |

4 | Fehr, E. , & Gachter, S. ((2002) ). Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature, 415: (6868), 137–140. |

5 | Francis, G. L. , Gross, J. M. , Turnbull, A. P. , & Turnbull, R. ((2014) ). Understanding Barriers to Competitive Employment: A Family Perspective. INCLUSION, 2: (1), 37–53. |

6 | Granovetter, M. ((1978) ), Threshold models of collective behavior. American Journal of Sociology, 83: , 489–515. |

7 | Haines, K. , Soldner, J.L. , Zhang, L. , Saint Laurent, M. , Knabe, B. , West-Evans, K. , Mock, L. , & Foley, S. , ((2018) ). Vocational rehabilitation and business relations: Preliminary indicators of state VR agency capacity. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 48: , 133–145. |

8 | Holland, B. ((2016) ). Both sides now: Toward the dual customer approach under the workforce innovation and opportunity act in the United States. Local Economy, 31: (3), 424–441. |

9 | Kessler Foundation ((2017) ). Report of Main Findings from the Kessler Foundation 2017 National Employment and Disability Survey: Supervisor Perspectives. East Hanover, NJ. |

10 | O’Brien, C.L. & O’Brien J. ((2000) ). The Origins of Person-Centered Planning: A Community of Practice Perspective. Responsive Systems Associates from the Center on Human Policy, Syracuse University for the Research and Training Center on Community Living. Distributed by ERIC Clearinghouse, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED456599 |

11 | Simonsen, Monica , Fabian, Ellen S. , Buchanan, LaVerne , & Luecking, Richard. ((2011) ). Strategies Used by Employment Service Providers in the Job Development Process: Are they consistent with what employers want? (Technical Report for TransCen, Inc.). |

12 | Social Security Act of 1935, as amended by Pub. L. 89-97 to be codified at 42 U.S.C. §§301-Suppl. 4 (1965). |

13 | Test, D. W. , Mazzotti, V. L. , Mustian, A. L. , Fowler, C. H. , Kortering, L. , & Kohler, P. ((2009) ). Evidence-based secondary transition predictors for improving post-school outcomes for students with disabilities. [Abstract]. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 1–22. Retrieved March 14, 2018 from http://proxy.library.vcu.edu/login?url=http://cde.sagepub.com/content/early/2009/10/21/0885728809346960. |

14 | short Wehman , P., Revell G. , & Brooke, V. ((2003) ). Competitive employment: Has it become the first choice yet? Journal ofDisability Policy Studies, 14: (3), 163–173. |

15 | Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014, as amended by Pub. L. 114-18, to be codified at 29 U.S.C. (2015). |