The Challenge of Political Will, Global Democracy and Environmentalism

Abstract

In 2024, around the world nearly 60 national elections will be held involving billions of people. Many commentators see this as a make-or-break moment in terms of re-establishing democracy and pushing back against rising authoritarian regimes that have been increasing in recent years. This essay explores why –despite worldwide scientific consensus that we are facing ecological collapse –there is little discussion about the climate crisis among the upcoming wave of national elections. This silence around the climate emergency raises several pressing questions: Why is there limited political will on behalf of national leaders when it comes to mitigating the climate crisis? What does this suggest about the state of democracy when political leaders can sidestep and ignore the escalating demands of their constituencies? Finally, what actions can be taken by ordinary people who are increasingly subject to repressive anti-protest laws that prevent them from speaking out against antidemocratic leaders and their political collusion with the fossil fuel sector?

1Introduction: 2024 A Make-or-Break Year

The year 2024 can be understood as a watershed moment in terms of democracy and its sustainability as a political ideology around the world. Throughout the year, nearly 60 national elections will be held to determine new presidents, prime ministers, and national leaders in countries such as India, Mexico and the UK. In addition, the entire 27 countries of the European Union will be involved in electing 720 members to the European Parliament. These elections involve billions of people –nearly half the global population –in every part of the world including the United States. According to some commentators, this year will experience “one of the largest and most consequential democratic exercises in living memory. The results will affect how the world is run for decades to come”.1

Already in the early months of 2024 national elections have taken place in Indonesia and Pakistan. Notably, political campaigning in both countries rarely referred to the climate emergency as a central electoral issue, despite citizens’ respective fears of rising oceans and devastating droughts and floods related to planetary warming. Similarly, as political campaigning steps up in the UK, US, and India, there is little discourse to the climate emergency as a central pillar of any political party. Across the global political landscape there appears to be a lack of interest in discussing, let alone suggesting possible solutions, to the climate crisis beyond vague references to quasi-scientific techno-fixes such as CO2 capture, storage and conversion, as well as vague promises of transitioning to renewable energy. Canada is a notable case in this regard. Its dependence on oil sands and fracking, which requires more energy for extraction than conventional drilling, has ushered in a quagmire of confusing policies that in the end have done very little to bring the country towards fulfilling its greenhouse gas reduction pledges.

This essay explores why –despite worldwide climate science consensus that we are facing ecological collapse and increasing weather catastrophes –there is little discussion about the climate as a central priority of political parties among the upcoming wave of elections. This silence around the climate emergency raises several pressing questions: Why is there limited political will on behalf of national leaders when it comes to mitigating the climate crisis? What does this suggest about the state of democracy when political leaders can sidestep and ignore the escalating demands of their constituencies? Where does this apathy at the national level leave the world’s population facing a climate emergency, and what possible actions can be taken by ordinary people experiencing in their everyday lives the impacts of planetary warming?

In thinking about these complex questions, I argue that we need to examine the lack of national political will to address environmental degradation against a global geopolitical backdrop of rising antidemocracy and authoritarianism. By highlighting the clear connection between climate inaction and far-right politics, the pathway forward becomes clear. Connecting two global trends –rising antidemocracy and escalating climate crises –sheds light on what is the biggest hurdle in mitigating ecological collapse. This is the collusion between extremist politicians and international energy and banking sectors upon which a growing number of these national leaders depend to finance their political campaigns.2 This connection underscores the message presented in the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report titled “Mitigation of Climate Change” (2022). According to the report, the scientific expertise and know-how to slow planetary warming is already available. Missing, however, is what the report states as “the lack of political will”.

In the context of many national governments procrastinating around the climate emergency, this essay is an urgent call for all efforts–particularly in major polluting nations in the global north such as the United States, Canada and Australia–to press political leaders on their environmental policies and to use the electoral process to demand immediate action. Putting this differently, the environmental crisis must become part of national political conversation and a central issue in upcoming national elections. Concurrently, these efforts will also require fighting back against far-right efforts to suppress voting and censoring journalists and independent media, which is proving very challenging in the United States and elsewhere. Despite these uphill battles presented by a global lean toward antidemocracy, the stakes could not be higher. Given the extraordinary number of national elections taking place throughout 2024, this year presents a make-or-break moment in terms of stalling planetary warming and planning for viable collective futures.

2Rising Antidemocracy and the Global Lean Toward Authoritarianism

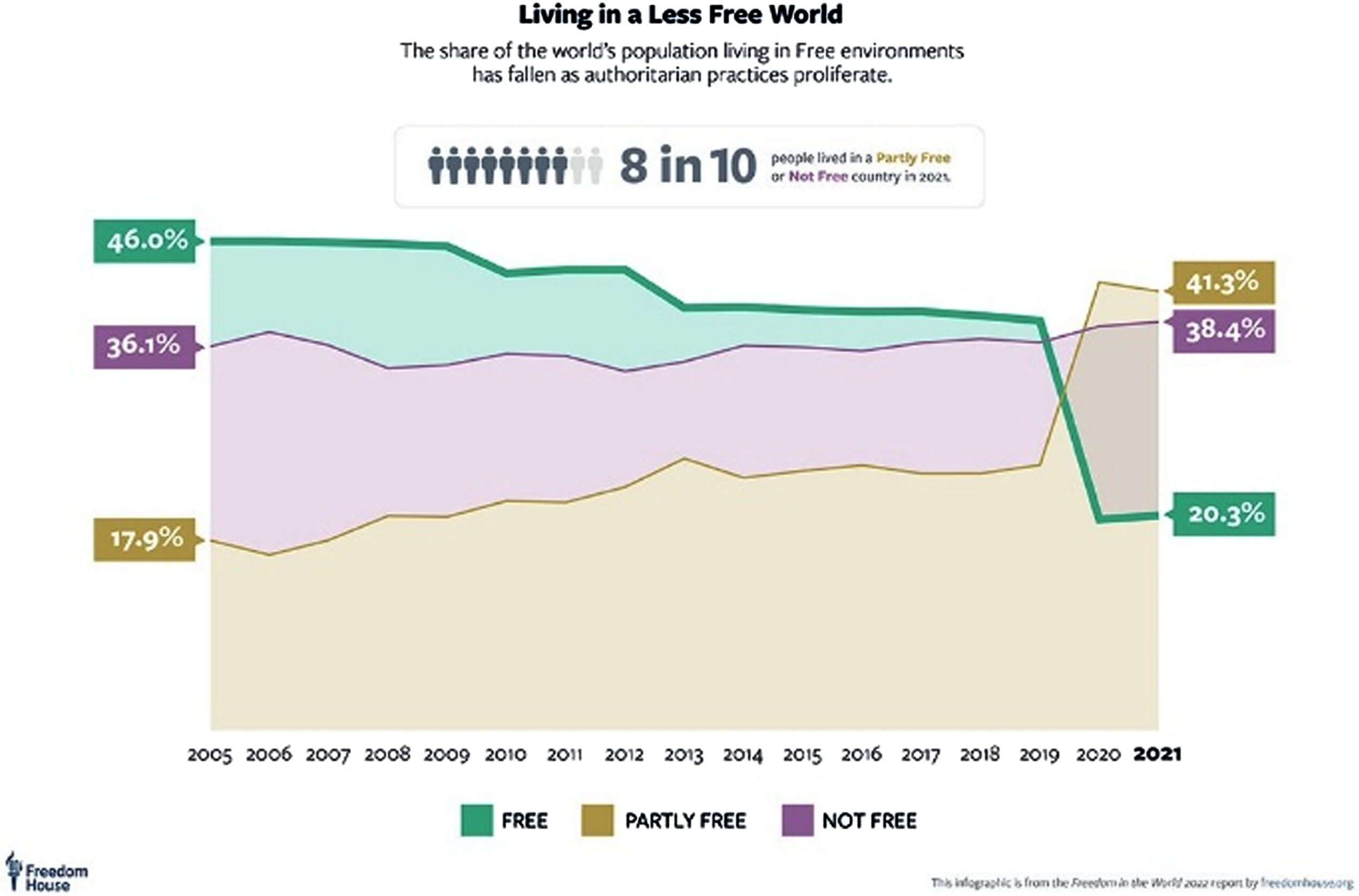

Around the world watchdog organizations such as Freedom House and V-Dem, as well as the Economist and other international organizations, have shown a decline in democratic societies around the world.3 Charting metrics such as the right to vote, access the law, free media and an independent judiciary, these organizations show that basic democratic principles have declined over the past decade with a particularly quick drop during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Living a Less Free World. Freedom House Freedom in the World Report 2022, page 4.

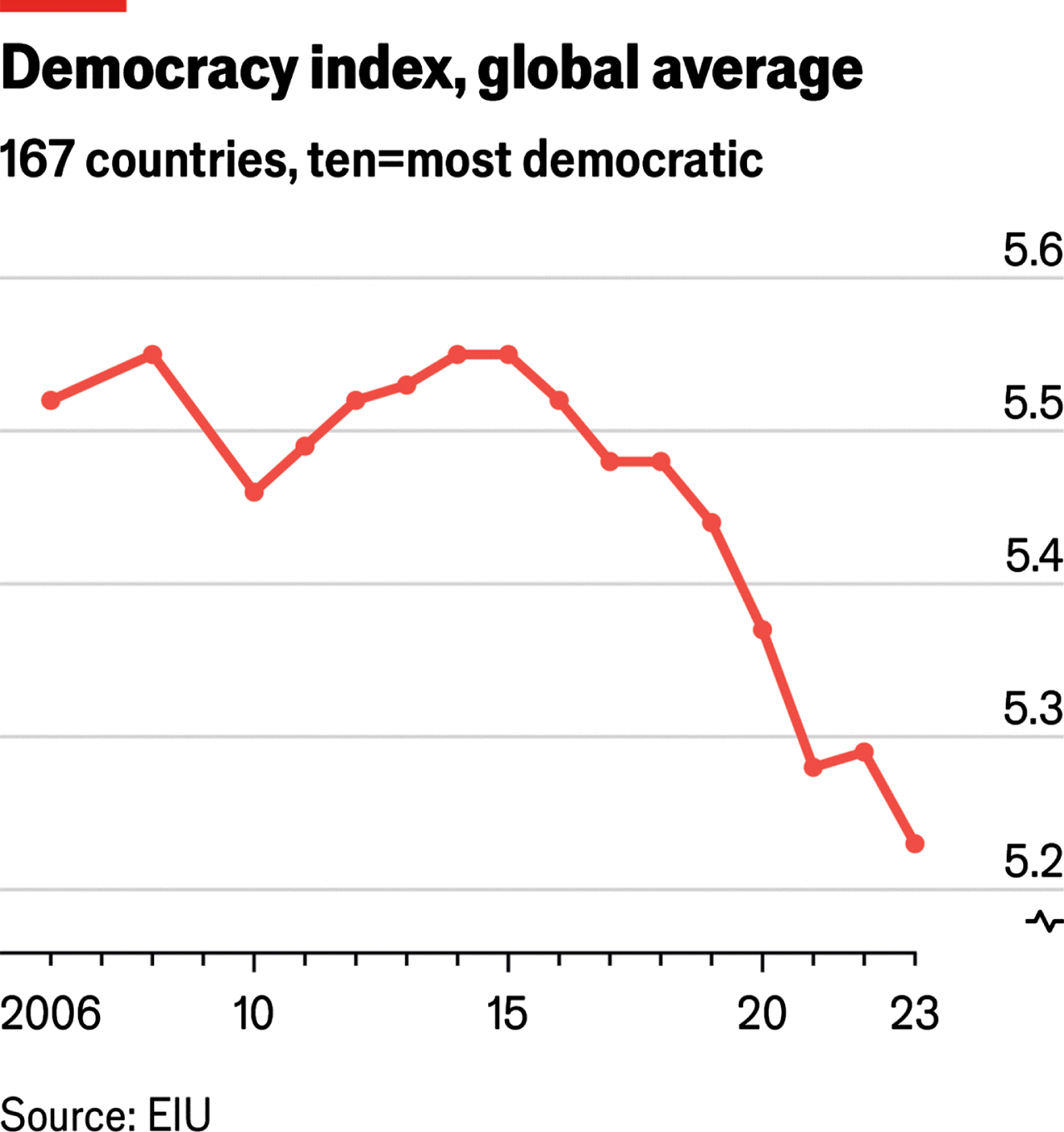

According to the Economist’s EIU report (which charts a broader set of 60 indicators to measure political democracy than that used by Freedom House) there has been a rather dramatic decline in democratic governance since 2015 (See Fig. 2). The report notes that across the world’s population “Only 7.8% reside in a ‘full democracy’, down from 8.9% in 2015; this percentage fell after the US was demoted from a ‘full democracy’ to a ‘flawed democracy’ in 2016”. The report goes on, “More than one-third of the world’s population live under authoritarian rule (39.4%), a share that has been creeping up in recent years”.4 These gloomy statistics are confirmed by the holocaust historian Dan Stone who sees echoes in today’s antidemocratic politics with past fascist regimes. Ominously, he argues that with the rise of the radical right across Europe, the United States and elsewhere, “fascism is not yet in power. But it is knocking on the door”.5

Fig. 2

The Economist: Democracy Index 2023: Age of Conflict, page 3.

Analysts of the global antidemocratic trend tend to focus on issues such as stricter border security, draconian anti-immigration laws, unilateral trade agreements, and white racist ideology that involves Islamophobia and antisemitism. I argue that less noticed, but arguably even more important, is the far-right’s weaponization of the environment in recent years. In my work I show additional factors that should be considered as symptomatic of the global antidemocratic trend. These include the withdrawal of many countries’ commitment to multilateral cooperation to reduce greenhouse gases as pledged in the Paris Agreement in 2015, as well as the rolling back of national environmental policies that protect lands from mining, environments and rainforests from pollution, and animals from potential extinction. Importantly, these policies and practices are occurring in global north and global south countries across a wide range of antidemocratic regimes including those that claim to be liberal democracies.

In the United States, the politicization of the environment was very apparent under the former Trump administration that rolled back 50 years of environmental laws, opened up national parks to drilling and mining, withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement, and stacked the Supreme Court with a conservative 6–3 supermajority that decided to gut the powers of the Environmental Protection Agency (West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency (2022). While current Democratic President Joe Biden has tried to reverse this course of action underscored by his pro-climate Inflation Reduction Act (2022), the harm caused by Trump is long-term and runs deep. Apart from the difficulty of reinstating environmental legislation, it is legally challenging to withdraw mining leases and federal contracts. At the international level, even though the United States has under Biden rejoined the Paris Agreement, the possibility of returning to the global pro-climate momentum of ten years ago that led to the landmark Paris Agreement in 2015 now seems very remote and rather quaint. Notably, 2015 was a high point in the terms of the global democratic index (Fig. 2). The rapid decline in the index since then is a telling reflection of how fast the world has shifted politically toward authoritarianism and away from pro-climate mobilization within less than a decade.

3Environmental Impacts and Public Demands for Climate Action

Every country around the world has been impacted to varying degrees by the accelerating climate crisis in recent years. Devastating heat domes and torrential rains have caused enormous swathes of land to burn and drown, and hundreds of thousands of people to flee and be dispossessed of their homelands. Unfortunately, these environmental impacts disproportionately affect those living in less wealthy countries of the global south, particularly people in marginalized socioeconomic positions. Putting this differently, the poor and impoverished have most immediately and consequentially experienced the adverse impacts of the climate emergency. However, with climate scientists predicting 2024 to be the hottest in recorded history, even the wealthy are now feeling the effects. In other words, nobody can pretend that we are not facing a real and imminent climate emergency. While climate science denialism continues to have sway among some far-right political groups and their constituencies, beyond such extreme communities (i.e. Trump’s core MAGA base) there is global recognition that humankind must act immediately to mitigate a climate catastrophe.

Not surprisingly, climate anxiety is real, widespread and accelerating, particularly among younger generations.6 This helps explain pro-climate demonstrations around the world throughout 2019 before political momentum was disrupted by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Spearheaded by then high school student Greta Thunberg who started the “School Strike for Climate” social movement in 2018,7 the Global Climate Strike fostered massive demonstrations for a week in September 2019 that coincided with the United Nations Climate Action Summit.8 The September protests saw over 4,500 mass mobilizations in 150 countries with an estimated participation of over six million people.

These public protests, in tandem with real life experiences of millions of people on the frontlines of the climate crisis, underscore growing alarm around the climate emergency. This alarm is evidenced in numerous polls showing that most of the world’s population considers the climate crisis a threat requiring urgent political action. For instance, a group of European economists have conducted a survey across 125 countries, interviewing nearly 130,000 people. According to the authors there is “an almost universal global demand for intensifying political action. Across the globe, 89% of respondents state that their national governments should do more to fight global warming. In more than half the countries in our sample, the demand for more government action exceeds 90% ”.9

4Antidemocracy and Anti-environmentalism

Despite political demands by huge majorities of ordinary people around the world, political leaders are failing to listen and respond to their citizens. In my book Global Burning: Rising Antidemocracy and the Climate Crisis (2022),10 I examine why this is the case and conclude that the world is experiencing two interrelated global phenomena –rising authoritarianism and escalating planetary warming. These interrelated global trends point to the collusion between a wave of far-right political strongmen over the past decade and their increasing reliance on Big Oil and global banks to finance their electoral campaigns and keep them in office. The book compares catastrophic wildfires in Australia, Brazil and the United States that broke out in 2019-2020 under the far-right leadership of Scott Morrison, Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump respectively. I show that each leader came to power on several promises that included the deregulation of environmental laws and promotion of anti-environmental policies that explicitly appealed to mining corporations, agribusiness, and their global financiers.

Unfortunately, I could have chosen any number of countries with a similar turn toward far-right extremism and political pandering to the fossil fuel industry. For instance, in September 2022 Sweden, Britain and Italy elected to office far-right leaders. Sweden voted in Jimmie ringAkesson, leader of the far-right party the Sweden Democrats. The party has a deep association with white supremacy and was the only Swedish party to push a climate-skeptic position and oppose the ratification of the Paris Agreement. Again, in September 2022, Britain’s conservative party voted in Liz Truss, a former Shell executive, who quickly overturned a ban on fracking and increased investments in North Sea oil and gas. Truss lasted less than two months in office before being ousted by current Prime Minister Rishi Sunak who has continued to pursue a pro-extraction energy agenda and roll back environmental regulations.

Finally, again in September 2022, Italy elected Giorgia Meloni as Prime Minister and leader of the Brothers of Italy party which has deep fascist connections and historically opposed EU plans to reduce gas emissions. At the time of her election, fears that Meloni would open up gas and oil leasing was a major concern for environmental scientists and civil society organizations. That fear remains high. In early 2024, Meloni convened a summit in Rome with two dozen African and European leaders, announcing plans for Italy to become an “energy hub” and creating “a bridge between Europe and Africa” in the so-called Mattei Plan (named after Enrico Mattei and founder of the state oil and gas company Eni in the post-war II era).11 According to Silvia Francescon from the pro-climate Italian think tank Ecco, “There is no reference to the Paris Agreement or the COP decisions. Based on what we currently know, there is undoubtedly a risk that funds meant for climate and international development could be used for projects managed by companies like Eni”. She goes on, “The ambiguity is very worrying”.12

Turning to the more recent national elections in the Netherlands and Argentina in November 2023, and Pakistan and Indonesia in February 2024, the four countries have elected to office far-right political leaders. Argentina, Pakistan and Indonesia voted in Javier Milei, Imran Khan and Prabowo Subianto respectively –all men well-known for their human rights abuses and corruption. The three countries are now widely regarded by the international community to be on a downward trajectory of democratic backsliding. With respect to all four new governments’ policies on the environment, the future looks very bleak.

(1) In the Netherlands, far-right Geert Wilders won the Netherlands general election in November 2023 on campaign promises vowing to tear up European Union climate policies. It is not clear how he will be able to exert strong leadership over a coalition government, but Wilders has stated he plans to remove the Netherlands from the Paris Agreement, ramp up oil and gas drilling in the North Sea, and stop the transition to renewable solar and wind energy.13

(2) In Argentina, Javier Milei rose to presidency in November 2023 on a campaign that targeted what he called elite politicians who he denounced as lazy and immoral. Using rhetoric that echoed that of far-right Donald Trump (US) and Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil), Milei claimed to represent the ordinary worker and promised to clean up the economy and crime. Once in office, he added neo-Nazis to his administration and quickly set in motion aggressive polices for deregulating the economy that resulted in a sharp currency devaluation and widespread austerity measures. Attacks on public health, public education and workers’ rights led to massive protests and demonstrations in early 2024. With respect to the environment, Milei denounced climate change as a “socialist lie” that interfered with his free-market policies and called climate science “fake”.14 Given the widespread precarity of millions of people, the marginalized social groups championing the environment have considerable challenges ahead if they are going to turn government policies toward a pro-climate agenda.

(3) In Pakistan the major political parties running for government in February 2024 all included reference to the environment in their manifesto statements.15 But specific details about climate mitigation were lacking, and there appeared to be more rhetoric than actual policy and practical implementation. The election results startled everyone, with Imran Khan getting the most votes despite being held in jail. A new coalition government was formed that included the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), with both groups committed to blocking Imran Khan’s party (PTI) form assuming power. In the political jostling of multiparty leadership, climate action will probably not be prioritized despite the desperate urgency faced by the nation’s population still reeling from catastrophic floods in 2022.

(4) In Indonesia, the world’s third largest democracy, far-right Prabowo Subianto was voted in as the new president in February 2024. Indonesia is the world’s largest exporter of coal, primarily to China. In addition to expanding its export coal production in recent years, coal is needed to support the extraction of nickel for the development of the country’s domestic battery-making industry. Compounding Indonesia’s rapid escalation of carbon dioxide emissions through mining, the country is the world’s largest exporter of palm oil. Deforestation of palm trees and other biofuels is a major concern among environmental activists and has led to Indigenous communities being driven from their lands and forests. These groups are also very wary of Prabowo Subianto who was removed from the army a few years ago for kidnapping political dissenters. As the new president, there is every indication that Prabowo Subianto will continue the plans of outgoing president Joko Widodo who, despite promises to shift away from coal, in fact increasingly ramped up coal, nickel and palm oil production. Among environmental groups, there are widespread fears that Mr. Prabowo will return to his former style of kidnapping and silencing those associated with resistance to national anti-climate policies.

Upcoming national elections in South Africa, India, and across the EU will all probably return increased power to extremist –and in some cases explicitly neofascist –political figures and parties. In the United States, the November 2024 presidential election is already agitating environmental activists and climate scientists. Trump has indicated that if re-elected, his second term will be even more severe than the first and he will aggressively drive fossil fuel production, open national parks to mining and drilling leases, further diminish laws regulating greenhouse gas emissions, undermine and underfund the EPA, and again withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement.16 According to Andrew Rosenberg, a former National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration official, “A return of Trump would be, in a word, horrific”. He went on, “It would also be incredibly stupid. It would roll back progress made over decades to protect public health and safety, [and] there is no logic to it other than to destroy everything. People who support him may not realize it’s their lives at stake, too.”17

Political commentators anticipate that with the rise around the world of antidemocratic regimes there will be a correlative rise in anti-climate legislation and reduced political will at the national level to mitigate the climate emergency. National elections so far in 2024 illustrate that this is a likely scenario. These unfolding elections underscore the connection between antidemocratic politics, climate science skepticism and anti-environmentalism that together perpetrate harm on citizens and promote the degradation of environments. Future national elections throughout the year also bode badly for any aggressive pro-climate laws and policies. Globally, renewed enthusiasm among nations to either honor their respective greenhouse gas emissions pledges or build multilateral collective solutions to slowing the warming planet appears very remote.

5The Global Wave of Anti-Protest Laws

A global wave of repressive laws against free speech and public peaceful dissent has emerged in recent years. These anti-protest laws correlate to increasing numbers of antidemocratic leaders determined to shut down challenges to their authority to govern. Civicus Monitor is a watchdog organization with global alliances around the world that has been tracking restrictions on public protests for over two decades.18 Its findings are that excessive force and detentions of people who have demonstrated in the streets is rapidly escalating. In 2022 it reported that the right to protest peacefully, which is protected under international law, had been violated in over 75% of countries where public protests took place. In 2023, it reported that “Among the most targeted and worst-affected groups in 2023 are those advocating for democracy, better governance and protecting the environment”.19

Disturbingly, in the United States the push for anti-protest laws has often been led by multinational fossil fuel companies such as ExxonMobil, Murray Energy Corporation, Chevron and TransCanada. Since 2016, energy companies have worked with law enforcement agencies, lobbyists, think tanks and Republican politicians to enact a range of sweeping anti-protest laws in 21 states that prosecute demonstrators for coming near “infrastructure” such as gas pipelines. These laws emerged as a direct response to Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock in 2016 which drew international attention for the violent response of police to peaceful climate protestors that included small farmers and Indigenous peoples on whose lands the pipes were laid (Fig. 3). Notably, many of these anti-protest laws drew their inspiration from model legislation drafted by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a conservative organization funded by Big Oil companies.

Fig. 3

Standing Rock solidarity march in San Francisco, November 2016. Photograph by Pax Ahimsa Gethen. (Wikimedia Commons).

In 2020, the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), an independent think tank based in Washington DC, issued a report titled Muzzling Dissent: How Corporate Influence over Politics Has Fueled Anti-Protest Laws. The report focused on three states –Louisiana, Minnesota and West Virginia –and explored a new legal tactic used by elected officials who are “under the thumb of powerful corporate lobby interests”. In its executive summary, the report stated:

Since 2017, so called “Critical Infrastructure Protection” laws targeting protests movement have sprung up in states around the country, in an effort to muzzle opposition to construction of oil and gas pipelines and other polluting chemical and fossil fuel facilities. Under the premise of protecting infrastructure projects, these laws mandate harsh charges and penalties for exercising constitutional rights to freely assemble and to protest.20

Importantly, the report commented on the implications of these laws for broader protests on a range of social justice issues.

Criminalization of protests elevates political and corporate interests above civil rights and civil liberties protected under the US Constitution. This report offers a particularly timely examination of a set of laws that carry implications not only for environmental and Indigenous activists and movements, but also for broader social justice movements that utilize protests as a means to effect change. These laws that aim to inflict harsh penalties for protesting oil and gas projects also impact ongoing national protests against police brutality and future protests that might result from the results of the presidential election. 21

A more recent report was published by Greenpeace titled Dollars vs Democracy 2023: Inside the Fossil Fuel Industry’s Playbook to Suppress Protest and Dissent in the United States.22 This report builds on the earlier IPS report, detailing the way fossil fuel companies have colluded with the far right to silence political dissent across 21 states. This has resulted in about 60 percent of US oil and gas operations being shielded from public demonstrations. In addition to the anti-protest laws, Greenpeace mapped a legal strategy whereby oil companies use civil lawsuits (called SLAPPS) to harass and intimidate climate activists and chill legitimate political dissent. Oil companies also provide subsidies to law enforcement agencies for their assistance in cracking down on protestors, as well as sometimes employing private security firms that include “off-duty” police officers. According to its executive summary:

In many cases, the fossil fuel industry has worked in lockstep with government allies: officials who may share in the industry’s ideology, but who have also benefited from its election spending, lobbying, targeted payments, and shared financial interests, or have passed through the “revolving door” from industry to government or vice versa.

Commenting on the Greenpeace report, Nicholas Robinson, at the International Center for Not-For-Profit Law, said “The fossil fuel industry has lobbied for these extreme anti-protest laws to shut down criticism of them. Climate change is an urgent challenge and all Americans, including the communities most impacted by these fossil fuel projects, have a right to have their voice heard, not silenced, at this critical moment for the planet”.23

Outside the United States, anti-protest laws are equally, if not more, oppressive. For instance, in Australia protestors face severe fines of $25,000 and up to five years in jail for non-violent acts such as blocking traffic, preventing logging in a forest, or remaining in a public place if asked to leave. Harsh new laws have often been rushed through state parliaments with little public debate or comment. The scholar Sophie McNeill argued, “This politically motivated crackdown on protest by successive Australian authorities appears designed to intimidate the climate movement and create a chilling effect on those thinking of taking to the streets.”24

Similar to what is happening in Australia, across Europe in Britain, France, Italy, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands, harsh new anti-protest laws have been enacted resulting in mass arrests and the labeling of protestors as “eco-terrorists”, “rioters” and “hooligans”. For instance, in the Hague, Netherlands, water cannon was used to break up a large climate protest in May 2023. More than 1,500 people were arrested and seven activists convicted of sedition for encouraging people to attend a public protest. Britain has led the charge with the most repressive and wide-ranging laws introduced in recent years through the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act (2022) and the Public Order Act (2023). These laws have been pushed by the conservative government and energy lobbyists in direct response to a range of high-profile protests calling for the stop of gas and oil leases being issued and demanding a transition to renewable energy by activist groups such as Greenpeace, Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion (Fig. 4). According to Michael Frost, UN rapporteur on environmental defenders, what is unfolding in Britain is “terrifying” and providing a roadmap for other countries to pass similar legislation. Frost also noted that in crackdowns in Britain and across Europe, police agencies play a coordinated role.

Fig. 4

Just Stop Oil activists walking up Whitehall towards Trafalgar Square on Saturday 20 May 2023. Photograph by Alisdare Hickson. (Wikimedia Commons).

I’m sure that there is European cooperation among the police forces against these kinds of activities. My concern is that when [governments] are calling these people eco-terrorists, or are using new forms of vilification and defamation ... it has a huge impact on how the population may perceive them and the cause for which these people are fighting. It is a huge concern for me.25

Adds Catrinel Motoc, senior campaigner at Amnesty International, “People all around the world are bravely raising their voices to call for urgent actions on the climate crisis but many face dire consequences for their peaceful activism”.26

What the escalating anti-protest laws around the world highlight is that the “fight” against climate change is being redefined and imbued with new meaning. It is no longer only a fight by humans to mitigate a warming planet and defend the natural world and the human species from extinction. Increasingly, with the global rise of antidemocratic governments, the fight has morphed into a battlefront constructed by far-right leaders against their own citizens. This new battle line is driven by the need to prevent people from speaking up and peacefully demonstrating against pro-fossil fuel laws and policies. Given worldwide political demand by everyday citizens for their leaders to address the climate emergency, this reconfigured fight has become a lot more complicated. For the many millions of people taking to the streets to demand government action to avert ecological collapse, the stakes have skyrocketed in terms of monetary fines and threats of repression, incarceration, and violence.

6Conclusion

John Kerry, the United States climate chief, in announcing his stepping down in February 2024, urged political leaders around the world to stop delaying on climate mitigation. In pointing to the lack of political will, he said that some leaders have intentionally denied climate science and promoted disinformation, arguing that these leaders “are willing to put the whole world at risk for whatever political motivations may be behind their choices.” He went on to say that no country would be spared by the climate emergency: “This is a multilateral major challenge to the security of every nation on this planet, because we’re one planet, and we’re all linked”.27 Despite such dire warnings, Kerry’s words will likely have very little impact on national leadership, particularly going into a year of many national elections. As stated by Bharat Desai, professor of international law, “It remains to be seen as to how the UN member states earnestly walk-the-talk to stand by the planet Earth”.28

Given mounting geopolitical realities and lack of national political will, there is an urgent need to push for alterative political practices to address the climate emergency. Sub-states and cities are emerging as hubs of innovation and are now at the forefront of building new coalitions and networks at both translocal and transnational scales in implementing pro-climate strategies. These lower-level government initiatives are also increasingly working with grassroots climate activists, educators, farmers, property developers, infrastructure experts, labor representatives and other groups immediately impacted by a warming planet. There is a deep concern to counter widespread disinformation and communicate to wider populations the urgent need to address the climate crisis. It is increasingly clear that it will be up to local communities in cities, sub-states and regions to take the lead in mitigating the climate emergency and transcend the lack of political will among ethically and financially compromised antidemocratic national leaders.

Endnotes

1 Tiffany Hsu, Stuart A. Thompson and Steven Lee Myers (2024), “Elections and Disinformation Collide in Year Ripe for Chaos”, The New York Times, 23 January 2024.

2 Eve Darian-Smith (2023), “Deadly Global Alliance: Antidemocracy and Anti-environmentalism”, Third World Quarterly, 44(2): 284-299; See also J. Mayer (2016), Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right, New York: Anchor Books.

3 Freedom House (2022), “Freedom in the World: The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule”, available at: www.freedomhouse.org.

4 Economist Intelligence (2023), Democracy Index 2023: Age of Conflict, New York, pp. 3; available at: www.eiu.com.

5 Dan Stone (2023), The Holocaust: An Unfinished History, New York and Boston: Mariner Books.

6 General Comment No. 26 (2023) on Children’s Rights and the Environment, With a Special Focus on Climate Change, 22 August 2023, CRC/C/GC/26; available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/crccgc26-general-comment-no-26-2023-childrens-rights.

7 Available at: www.eastmoney.com.

8 The 2019 Climate Action Summit hosted by the UN Secretary General called for countries to develop concrete, realistic plans to enhance their nationally determined contributions by 2020, in line with reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 45 per cent over the next decade, and to net zero emissions by 2050; availbale at: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/2019-climate-action-summit.

9 Peter Andre, Teodora Boneva, Felix Chopra, and Armin Falk (2024), “Globally Representative Evidence on the Actual and Perceived Support for Climate Action”, Nature Climate Change, pp. 2; available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-01925-3.

10 Eve Darian-Smith (2022), Global Burning: Rising Antidemocracy and the Climate Crisis, Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

11 Italian Government, President Meloni’s Opening Address at the Italia and Africa Summit, 29 January 2024; available at: https://www.governo.it/en/articolo/italia-africa-bridge-common-growth/24853.

12 Matteo Civillini (2024), “Italy Launches ‘Ambiguous’ Africa Plan Fuelling Fears over Fossil Fuels Role”, Climate Home News, 1 January 2024. Available at: https://www.climatechangenews.com/2024/01/30/italy-launches-ambiguous-africa-plan-fuelling-fears-over-fossil-fuels-role/.

13 Ajit Niranjan (2023), “Success of Geert Wilders’ far-right PVV raises fears for Dutch climate policies”, The Guardian, 26 November 2023. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/26/geert-wilders-far-right-pvv-dutch-climate-policy.

14 Constanza Lambertucci (2023), “Climate Denier in the Casa Rosada: Milei’s arrival puts Argentina’s environmental agenda at risk”, El Pais, 1 December 2023. Available at:https://english.elpais.com/climate/2023-11-30/climate-denier-in-the-casa-rosada-mileis-arrival-puts-argentinas-environmental-agenda-at-risk.html.

15 P.M. Baigal (2024), “Analysis: How Green are Pakistan’s Political Manifestoes?”. The Third Pole, 3 February 2024; available at: https://www.thethirdpole.net/en/climate/pakistan-elections-how-green-are-manifestoes/.

16 Norman L. Eisen et al. (2024), “American Autocracy Threat Tracker”, Just Security, 26 February 2024; available at: https://www.justsecurity.org/92714/american-autocracy-threat-tracker/.

17 Oliver Milman and Dharna Noor (2024), “‘In a Word, Horrific’: Trump’s extreme anti-environment blueprint”, The Guardian, 6 February 2024, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/feb/06/trump-climate-change-fossil-fuels-second-term?utm_source=eml&utm_medium=emaq&utm_campaign=MK_CN_AcqPrimariesClimateUSFeb24Canvas&utm_term=Email_NLOnlyConsentProspectsUSA&utm_content=variantA.

18 Civicus, available at: https://monitor.civicus.org/globalfindings/.

19 Civicus, available at: https://monitor.civicus.org/globalfindings_2023/.

20 Gabrielle Colchete and Basav Sen (2020), Muzzling Dissent: How Corporate Influence over Politics Has Fueled Anti-Protest Laws, Institute for Policy Studies, pp. 5; available at: https://ips-dc.org/report-muzzling-dissent/.

21 Ibid, p. 35.

22 Greenpeace (2023), Dollars vs. Democracy 2023: Inside the Fossil Fuel Industry’s Playbook to Suppress Protest and Dissent in the United States, available at: https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/dollars-vs-dissent/.

23 Amanda J, Mason (2024), “New Report: 60% of US Oil & Gas Production and Local Infrastructure Protected by Draconian Anti-Protest Laws”, Greenpeace, 25 October 2024.

24 Sophie McNeill (2023), “Australia’s Crackdown on Climate Activists”, The Diplomat, 29 May 2023, available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/05/30/australias-crackdown-climate-activists.

25 Damien Gayle, Matthew Taylor and Ajit Niranjan (2023). “Human rights Experts Warn against European Crackdown on Climate Protesters”, The Guardian, 12 October 2023.

26 Damien Gayle, Matthew Taylor and Ajit Niranjan (2023), “Human Rights Experts Warn against European Crackdown on Climate Protesters”, The Guardian, 12 October 2023. See also Carolijn Terwindt (2020), When Protest Becomes Crime: Politics and Law in Liberal Democracies, London: Pluto Press; and Valerie Vegh Weis (ed.) (2022), Criminalization of Activism. Historical, Present and Future Perspectives, London: Routledge.

27 Fiona Harvey (2024), “Demagogues Imperiling Global Fight against Climate Breakdown, says Kerry”, The Guardian, 28 February 2024.

28 Bharat H.Desai (2023), “The 2023 New York SDG Summit Outcome: Rescue Plan for 2030 Agenda as a Wake-up Call for the Decision-makers”, Environmental Policy and Law, 53: 221-231; B.H. Desai (2023), “The 2023 New York SDG Summit Outcome”, Environmental Policy and Law, 53(4): 219; epl239006 (iospress.com).