Cultural heritage re-search: Reimagining the collective memory of Copándaro de Galeana, Michoacán

Abstract

The author reconnects with the ongoing struggles of her parents’ hometown, Copándaro de Galeana, located in Michoacán, Mexico, in this ethnographic critical research. Employing critical survey methods and analyzing the community’s identity reclamation through two festivals, El Carnaval and El Festival de las Almas y las Flores, the author collaborates with family members and friends to create a collective memory of Copándaro de Galeana’s intangible cultural heritage, underscoring the community’s self-expressed Resistant Knowledges.

As a critical cultural heritage study, this article addresses the dichotomy of exploitation vs empowerment present in archival aspects of cultural heritage preservation methods. It also examines how the author’s position as a Chicana/Mestiza, attempting to reconnect with her indigenous roots and the duality of Indigenismo, aids or counters the empowerment of Copándaro de Galeana.

Situated within the broader theme of “Resistant Knowledges: Unmasking Coloniality through the re-search of local to global communities,” the study addresses specific subtopics, emphasizing autonomous movements, identity and representation, and community resilience. Recognizing the important role that oral history has played in recording Copándaro de Galeana’s memory, the author similarly includes community members’ recollections and personal experiences to form a decolonized re-search article.

1.Introduction

This research is grounded in Critical Race Theory (CRT), utilizing its seminal tool of counterstories to center Mexican Resistant Knowledges within broader cultural heritage archival theoretical and methodological debates. As Dunbar (2006) notes, “Both CRT (through legal studies) and archival discourse are rich with various definitions of what can be evidence. CRT’s usefulness to archival discourse can also be examined through three of its methodological concepts: (i) counterstories, (ii) microaggressions, and (iii) social justice” (p. 114). Resistant Knowledges are processes of thinking and acting against the grain of coloniality to build collective consciousness and calls to action for racial justice and social change. Resistant Knowledges often develop within communities as shared, coordinated efforts (collective rhythms) to challenge and resist dominant ways of knowing (epistemic disobedience). These efforts can start at a very local level but have the potential to spread and influence larger, even global, communities, highlighting how grassroots, community-based knowledge can impact broader societal understandings and actions (Critical Race Theory collective, 2023; Gago, 2020; Fuh, 2022).

This study directly and intimately counters the colonizing legacy of 16th c. Augustianian friars by advocating for cultural heritage self-expression and empowerment within the Copándaro de Galeana, Michoacán community. Through Dunbar’s (2006) concept of counterstories, this re-search aims to develop a narrative that competes with or challenges the lack of representation and voice of Copandarenses in the recorded history of the community. Solorzano and Yosso (2002) and Delgado (1989) emphasize the significance of storytelling as a means of empowerment, noting how dominant narratives strip a community’s cultural richness, narrative, perspective, and emotions.

CRT has expanded to include broader scopes beyond race, encompassing archives and research methodologies. To interweave CRT and cultural heritage archival discourse, this research utilizes counter storytelling, focusing on the CRT tenet of the permanence of racism, particularly within the context of colonialism. Additionally, Dunbar’s (2023) Information tenets are employed to include a broader scope of CRT that expands into the archival aspect of cultural heritage:

CRiT as a framework also aligns well as an instrument for analysis and assessment of informatics as components of research, activism and theory building. CRiT establishes “information” to be understood as phenomena that influence academic disciplines, sociocultural context, economic circumstances, health outcomes, and within everyday human interactions; thus, CRiT also exists as an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary framework. Simply stated, CRiT as a process of theory building can (and should) lead to the open dialogue, in essence, the describing of new critical race theories, terminologies and forms of praxis, which ultimately leads to the construction of (additional) tools and frameworks when utilized form paths of resistance as well as routes for socially and culturally detours for the roads of techno-determinism that point toward the fatalistic destinations within the information industrial complex (pp. 364–366).

Dunbar’s (2023) Information tenets emphasize:

(i) Every aspect of information, including its form, use, structure, and infrastructure can be analyzed in order to understand the ways in which it reflects and represents the beliefs, values, practices, and politics of our society; and how in turn such dynamics affect individuals and groups that are traditionally positioned in society as marginalized or disenfranchised (ii) Every information context is an opportunity for a critical race discussion or analysis. Everywhere information engages society: CRiT is a viable lens to assess the engagement through (p. 365).

As forms of information, cultural archival records fall under Critical Race Information Theory (CRiT). This theoretical framework sets the stage for the re-search methodology employed in this study, which seeks to uncover and amplify the cultural narratives and resistant knowledges of Copándaro de Galeana through a detailed and immersive ethnographic approach.

2.Methodology

The interconnected nature of the theoretical framework extends into the methodological approach. By integrating CRT and cultural heritage archival discourse, this research cultivates two key methodological conversations: cultural heritage and re-search.

2.1Cultural heritage methodology

The cultural heritage methodology aims to understand Copándaro de Galeana’s culture, the community’s assets, and address the dichotomy of exploitation vs empowerment through a critical cultural heritage approach. Salvatore & Lizama (2018) state:

In that regard, UNESCO defines cultural heritage as both tangible and intangible …tangible cultural heritage is easy to detect and discern; on the other hand, intangible cultural heritage is more complex …These five major domains include: (1) oral traditions and expressions; (2) performing arts, widely defined; (3) social practices, rituals, and festive events; (4) knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; and (5) traditional craftsmanship.” (pp. 3–5)

This study re-connects the ongoing struggles and legacy of Copándaro de Galeana, Michoacán to the evolving concept of identity through the analysis of its tangible and intangible cultural heritage – iconic structures, performing arts, rituals and festive events, and traditional craftsmanship. Additionally, this study aims to address gaps in current research on preventative critical archival discourse focusing on communities who are expanding their cultural heritage preservation methods while navigating the complexities of such task nearly 500 years since its cultural genocide (Dorval, 2023).

More specifically, this critical cultural heritage methodology analyzes the complexities and effects of preservation methods on/in Copándaro de Galeana, examining the power that archived records have on historical scholarship, collective memory, national identity, knowledge of self, knowledge as a group, and knowledge as a society. This methodology addresses the hegemonic power of 16th century records and the resulting stripping of pride in this community, leading to apathy towards historical knowledge within the community and a disconnect and displacement from Purépecha indigeneity felt by its people. It counters the hegemonic power of archives within cultural heritage preservation by using oral histories and an ethnographic approach, centering Mexican storytelling and the inclusion of self in research as forms of Resistant Knowledges (Critical Race Theory Collective, 2023).

2.2Re-search methodology

Building on the use of oral histories and an ethnographic approach, the re-search methodology aims to cultivate critical research that challenges colonial narratives from the 16th century to the present day. It addresses how archival and research methodologies, which have historically excluded certain people, non-Western methods, and experiential knowledge, remain largely unchanged (Smith, 2021; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2017).

Employing survey methods such as interviews and focus groups, this study counters and decolonizes traditional research methodologies through testimonios to collectively reimagine and reclaim the memory and identity of Copándaro de Galeana with community members. As Rodriguez-Campo (2021) states, “testimonios are more than interviews or conversations. They challenge researchers to reconceptualize their role in the research process and their relationship with participants, emphasizing a collaborative and empowering approach to knowledge production.” This ethnographic re-search grounds the opportunity for an authentic and decolonized reconstruction of Copándaro de Galeana’s identity and collective memory, empowering rather than exploiting the community in the process of record creation.

3.Indigenismo

Furthermore, this re-search addresses the duality of indigenismo present in the reconstruction of Copándaro de Galeana, which ties back to the dichotomy of exploitation vs empowerment. According to Wikipedia (2024), indigenismo is “an expression of freedom for an imagined, reclaimed identity that was stripped during the Spanish colonization of Mexico.” This aspect of indigenismo is reflected in the community’s efforts to reclaim and celebrate their Purépecha indigenous roots through their reimagining of established and contemporary forms of intangible cultural heritage.

However, while indigenismo has helped to revive and celebrate indigenous cultures, it has also been criticized for reinforcing stereotypes or being co-opted by political agendas. Spears-Rico (2015) explores this in her work titled Consuming the Native Other: Mestiza/o Melancholia and the Performance of Indigeneity in Michoacan, stating, “people living in the moment were framed and read as from the past, with an unequivocal presentation of the inhabitants of Janitzio as an idyllic and romantic Other, an idea that was subsequently disseminated widely through ethnographic, popular, and tourist publications.” Her insights during Dia de los Muertos in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán and Janitzio, Michoacán challenged me to question and reflect on the ways that I, as a Mestiza/Chicana was viewing, researching, and reconnecting with my family’s community of Copándaro de Galeana and its Purépecha roots.

The re-search methodology in this study not only challenges the deeply embedded colonial narratives but also addresses the dichotomy of exploitation vs empowerment within the community of Copándaro de Galeana. By employing testimonios and focusing on oral histories, this approach seeks to counter traditional archival and research methodologies that have long marginalized non-Western methods and experiential knowledge. The emphasis on oral histories not only validates these forms of knowledge but also empowers the community by preserving and celebrating their rich cultural heritage. This re-search methodology, therefore, serves as a transformative tool to cultivate Resistant Knowledges, creating a more inclusive and equitable process of knowledge production. It aims to sow the seeds for a deeper understanding and appreciation of Copándaro de Galeana’s unique identity and history.

4.Background of Copándaro de Galeana

Located in the state of Michoacán, Mexico, Copándaro de Galeana is a community whose name, Cupanda-ro, translates to “place of avocados” in the Purépecha language, reflecting its rich natural resources and indigenous history. Originally inhabited by the Matlatzinca people and later part of the Chupícuaro Territory, Copándaro was one of the final conquests of the Purépecha kingdom.

Officially established as a municipality in 1949, Copándaro de Galeana plays a vital role in the agricultural landscape of Michoacán. Renowned for its diverse cultivation – including onions, tomatoes, corn, and cempasúchil (marigold) – the community contributes significantly to the state’s agricultural economy.

4.1Colonial impact and indigenous resilience

Amidst the 16th-century wave of new religious dominance by settlers, Copándaro de Galeana, like many communities in Michoacán, experienced the intense pressures of cultural assimilation. Families were torn apart, adults were separated from children, and women from men, enforced through the establishment of convents. The Augustinian missionaries introduced coercive practices such as monogamy, catechism, and the administration of sacraments, which disrupted traditional social structures and attempted to suppress indigenous customs (The University of Texas, n.d.).

Despite these challenges, Michoacán’s Purépecha historical narrative is preserved through Spanish records, notably the illustrated manuscript “Relación de Michoacán” (1539–1541) by Fray Jerónimo Alcalá. This manuscript, contributed by indigenous priests and community members, offers invaluable insights into their cultural practices, including celebrations honoring gods and goddesses and the life of Tariacuri, a legendary figure in Purépecha history (El Colegio de Michoacán, 2008). However, it’s important to emphasize that this manuscript is a master narrative, and as Solorzano and Yosso (2002) and Delgado (1989) note, it strips the community’s cultural richness, narrative, perspective, and emotions.

The injustices endured by the Purépecha people inflicted deep wounds on a community devoid of written language to preserve its heritage and customs. While many communities in Michoacán retained essential aspects of their indigenous culture, Copándaro de Galeana did so to a lesser degree. However, through a strategy of resilience and survival (Paredes, 1968; as cited in Seriff & Limón, 1986), oral traditions became crucial for transmitting knowledge, stories, and histories across generations, ensuring the survival of some cultural practices and resisting complete assimilation efforts.

4.2Legacy of colonization and modern identity

Today, Copándaro de Galeana’s Purépecha cultural genocide is felt by its people and is visible in data. During my visit to Copándaro last summer, I connected with Javier Alvarez Garcia, the Director of Culture, Education, and Tourism. He shared stories about the history of Copándaro that I had not found in my online research, emphasizing the struggle in forming a culturally relevant identity for the people of Copándaro:

We do not have something that we can touch, that we can see, that we can perceive as something of our antiquity. It can be said that we are a people to a certain extent without history, because you ask people and people don’t know how to tell you much about what Copándaro once was (J. A. García, personal communication, July 27, 2023).

This testimonio highlights the extent and impact of 16th-century colonization and forced conversion of the indigenous community in Copándaro under the Order of Saint Augustine. Copándaro’s historical identity was captured and recorded through the Spanish perspective, with structures such as the Templo de Santiago Apóstol, exconvento and its fresco artwork painted by the Augustinians being the oldest tangible identifiers of this community’s “antiguedad” (antiquity). Despite its population of roughly 9,500 residents, only 13 out of 9,500 inhabitants of Copándaro de Galeana speak an indigenous language (Data México, 2020).

This ethnographic research bears the fruits of my family’s labor, as they actively participated in the research process by sharing countless photographs from our family albums, offering their testimonios, and even taking on the role of researchers themselves to investigate their hometown and its history. Exploring my parents’ hometown has motivated me to delve deeper into and illuminate the broader cultural significance of this community. By uncovering its rich traditions and ongoing struggles, my aim is to emphasize the power of storytelling as a tool for empowerment, thereby highlighting Copándaro’s collective memory in this critical analysis of its cultural richness, narrative, perspectives, and emotions.

This conclusion reconnects with the overarching theme of cultural resilience and historical context explored throughout the Background of Copándaro de Galeana section, emphasizing the community’s endurance, the preservation of its cultural heritage, and the significance of personal and collective narratives in reclaiming and understanding its history.

5.Cultural narratives of Copándaro: Insights and reflections

In exploring the intangible cultural heritage of Copándaro de Galeana through on-site observations and testimonios, I witnessed a resilient and creative community. Seriff and Limón’s (1986) analysis of Mexican American folklife and identity provides a striking resonance with Copándaro de Galeana’s cultural heritage today:

Traditional objects produced and displayed are created with bits and pieces of material and formed into images which shape the look and feel of the neighborhoods …maintaining a Mexican American culture depends on the residents’ abilities to creatively use the materials at hand as resources for expression. It is important to stress that these materials are often neither complete nor traditional in and of themselves; they are bits and pieces cast off from a world largely defined by the dominant Anglo society, purchased from the counters of modern department stores, salvaged from the baggage of recent Mexican immigrants, or literally scavenged among the nooks and crannies of city life. Once incorporated into the folk aesthetic or barrio life, these bits and pieces are transformed into objects and expressions of beauty and meaning (p. 6).

This excerpt vividly illustrates how Copándaro de Galeana has employed revitalizing indigenismo – an act of reclaiming identity lost during the Spanish colonization of Mexico (Wikipedia, 2024). Copándaro exemplifies this identity reclamation through its well-established performing arts, rituals and festive events, and traditional craftsmanship, transforming these elements into expressions of beauty and meaning since their 16th-century origins.

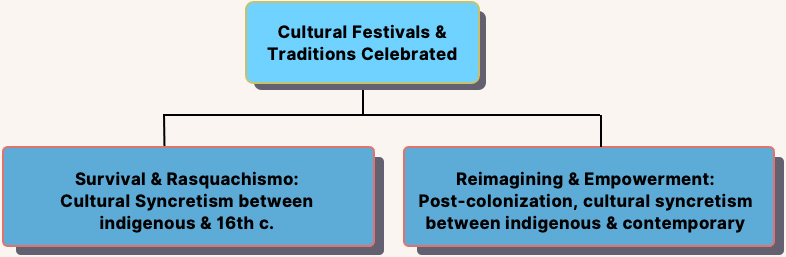

Before delving into the specifics of Copándaro’s 500-year-old festival, El Carnaval, it is crucial to categorize different aspects of its intangible cultural heritage. Figure 1 provides an overview of how the festival’s elements, including performing arts and traditional craftsmanship, reflect the revitalizing indigenismo at varying levels.

Figure 1.

Chart categorizing the intangible cultural heritage of Copándaro de Galeana.

I’ve categorized the 500-year-old festival’s aspects into two main themes:

1. Survival and Rasquachismo: This theme highlights the cultural syncretism between the 16th-century colonial influences and indigenous practices. It reflects how indigenous people preserved their ways of knowing amidst colonization, including oral traditions and spirituality. This cultural survival is characterized by resourcefulness and creativity, embodied by the concept of Rasquachismo – an attitude rooted in resourcefulness and adaptability yet mindful of stance and style (Seriff & Limón, 1986).

2. Reimagining and Empowerment: Focused on the post-colonization period, this theme continues the cultural syncretism between contemporary practices and indigenous heritage. It encompasses reimaginings of well-established elements and the creation of new ones by current residents, who creatively reconnect with and reclaim their indigenous history while addressing their current identity and needs. This process involves repurposing materials from dominant Anglo society, transforming them into artful expressions within the community (Seriff & Limón, 1986).

This framework illuminates the layers of cultural significance embedded in Copándaro’s intangible cultural heritage, demonstrating how these elements contribute to the ongoing process of cultural reclamation and identity formation. El Carnaval de Copándaro de Galeana, a 500-year-old festival, vividly exemplifies the themes of survival, rasquachismo, and empowerment.

5.1El Carnaval de Copándaro de Galeana

Copándaro de Galeana has long embraced the tradition of El Carnaval, a multi-day festivity held during Lent, a period typically spanning late winter to early spring. As reported by La Voz de Michoacán (2022), there are three main theories about its origins: it was brought by Africans from the Bantu tribe in Angola, introduced by Spanish colonizers, or initiated by Vasco de Quiroga to evangelize the Purépecha people. Despite its unknown origins, it is crucial to recognize that the practice of El Carnaval and its elements extend beyond this community to several others within the state. This widespread festivity underscores the deep-rooted influence of colonization in Michoacán on the dissemination and evolution of the tradition across the region.

El Carnaval in Copándaro de Galeana exemplifies the theme of survival and rasquachismo, highlighting the cultural syncretism between 16th-century colonial influences and indigenous practices. The survey methods employed in this ethnographic re-search, uncovered Copándaro de Galeana’s unique narrative on El Carnaval. The testimonios gathered, on-site observations, and online research collectively create a counterstory that centers this community’s cultural richness, narrative, perspective, and emotions regarding El Carnaval. This counterstory highlights the unique qualities that distinguish Copándaro’s Carnaval from how the festivity is practiced elsewhere in Michoacán.

As the Secretaría de Turismo del Estado de Michoacán (2023) emphasizes, carnavales serve as platforms for showcasing the unique elements of each celebrating town. El Carnaval in Copándaro de Galeana is not just a celebration but a multimedia display of intangible cultural heritage elements, prominently featuring El Baile del Torito de Petate (the dance of the little bull). This performance is characterized by three main forms of traditional craftsmanship:

1. Torito de Petate: Among the most iconic elements of El Carnaval, the Torito de Petate, which translates to “little bull of” (torito de) and “woven mat made from palm fibers” (petate) is a large, mixed media bull that is paraded and “danced” through the streets by men in the community. It has a table-like structured base with an embellished tablecloth that hides the performer underneath. A crafted bull head is attached to one end of the structure and its table-like body is vividly and overly embellished with flowers, glitter, and streamers (Fig. 2). It’s been the responsibility of La Familia Romero in Copándaro for generations to craft this performance object.

Figure 2.

Close up of Torito de Petate. A man is underneath this object’s table-like structured base with an embellished tablecloth that hides the performer underneath. A crafted bull head is attached to one end of the structure and its table-like body is vividly and overly embellished with flowers, glitter, and streamers.1

2. Mascaras de Carnaval: translates to “carnival masks” are wooden masks of the three supporting characters for el Torito de Petate during the performance. These characters are: El Caporal, symbolizing a courageous lead man who dances with the La Maringuia (the woman) and tries to help her onto the Jinete’s caballito. The Jinete, representing a cowboy riding a horse (caballito), typically dances around and evades the woman. All characters are played by male volunteers from the community (Fig. 3).

3. Flores de Carnaval: translates to “carnival flowers” are colorful tissue paper flowers with foil/metallic leaves and geometric ribbons that adorn the festivities, characters’ props, and Torito. Varying in sizes, they symbolize the arrival of El Carnaval and are only crafted by three families in Copándaro.

The traditional crafts produced and displayed during El Carnaval have been transformed into images that shape the look and feel of Copándaro de Galeana’s community. Artisan families infuse these objects with expressions of beauty and meaning, as seen in each year’s Torito de Petate, where craftsmen creatively arrange flowers, choose color schemes, and select fabrics to adorn the bull. Similarly, male residents who volunteer to wear the wooden masks infuse their personalities into their performances, dancing to the lively banda music and choosing outfits that complete their character.

Figure 3.

El Jinete with his caballito (left), La Maringuía (center), and El Caporal (right). All characters are played by men from the community.2

In an interview with Don Rigoberto Romero, head of the family known for crafting the Torito de Petate, featured in the local newspaper Acueducto Online, he shared insights into the origins of El Baile del Torito de Petate passed down through oral history in Copándaro. The article, titled “A Man of Character in the Copándaro Carnaval” (2020), explores Copándaro’s cultural heritage, particularly the origins of the Torito de Petate. Rigoberto’s remarks are translated as follows:

Don Rigoberto tells us that this tradition dates back many years, its beginnings with the Augustinian fathers who laid the foundations of the main church in Copándaro. There Were Tribes called Cheneques, which were very submissive, and in this way the tradition of the Torito de Petate emerged. The main instruments were a reed and a drum, which set the tone for the Torito. This tradition is 450 years old – when this temple was built. The Hacendados, as they were called, are the ones who started this tradition. The Torito is called Caporal de la Hacienda (paras. 3–5).

The Torito de Petate has evolved from humble beginnings with simple instruments like reeds and drums, transformed over centuries into a vibrant cultural symbol celebrated annually. Today, El Carnaval in Copándaro de Galeana embodies community pride and resilience, encapsulating the concept of rasquachismo – a cultural attitude rooted in resourcefulness and adaptability yet mindful of stance and style. This festivity is more than a historical reenactment; it is a testament to Copándaro’s ability to reimagine and reclaim its indigenous heritage through creative expression and communal celebration.

6.Reimagining and empowerment in El Carnaval

Furthermore, Copándarenses have transformed El Carnaval into a vibrant event that not only celebrates tradition but also cultivates community spirit and resilience. This multi-day festivity, embraced by generations of families both locally and abroad, showcases their resourcefulness, adaptability, and creativity in preserving and reimagining cultural practices.

Figure 4.

Santa Rita corn husks embroidered gown with traditional motifs.3

Families actively participate in all aspects of El Carnaval, from organizing the parade route to funding the craftsmanship of the iconic Torito de Petate. Local students, from kindergarten to high school, join a lively costume parade accompanied by live banda music, stopping (topas) at people’s homes along the route to engage with the community.

Central to the festivities is the Torito de Petate, inviting onlookers to join its dance beneath a table-like structure adorned with vibrant flowers and fabrics. This interactive element symbolizes community unity and participation. Supporting characters like El Caporal, La Maringuia, and El Jinete add depth to the performance, reflecting a blend of indigenous heritage and contemporary expression.

Figure 5.

Lago de Cuitzeo embroidered gown with traditional motifs.4

Beyond the modifications in stance and style of the Baile del Torito de Petate, Copándaro’s community has also added additional elements that reimagine and empower community members to feel a strong sense of communal identity during this 500-year-old festival. El Carnaval comes alive with bailes (dances), music, intricate pyrotechnics, and culinary delights from local businesses. Art exhibitions by schools and artists, along with a cultural pageant, highlight themes of agricultural heritage, local traditions, and modern-day challenges like environmental awareness. The pageant contestants, dressed in intricately embroidered gowns, proudly embody the community’s resilience and creativity (Figs 4–6).

Additionally, since its inception in 2019, the Expo Fiesta Carnaval Copándaro has boosted local businesses by showcasing traditional dishes, contributing to economic growth while preserving cultural heritage during El Carnaval.

6.1El Festival de las Almas y las Flores

Figure 6.

Monarch butterfly and Carnaval embroidered gown with traditional motifs.5

Building on this spirit of cultural celebration and community empowerment, El Festival de las Almas y las Flores (the Festival of Souls and Flowers) stands as a vibrant testament to Copándaro de Galeana’s ongoing cultural evolution, embodying the theme of Reimagining and Empowerment within the context of revitalizing indigenismo. The festival’s origins mark a resurgence similar to the Chicano Art Movement’s revival of Dia de los Muertos, aiming to reconnect the community with their roots and revitalize cultural practices. This festival is a revival of remembrance, prompting self-awareness and critical reflection on identity for the people of Copándaro through educational and spiritual gatherings. Taking place a week before the weekend of Dia de los Muertos, Copándaro kicks off this emblematic cultural ceremony for the region. The main plaza comes alive with large-scale altares and tapetes de asserín (sawdust carpets) designed by local schools, creating a spectacular display (Fig. 7). The festival features a diverse array of activities, including the traditional Purépecha fire ball game (Uárukua Ch’anakua), traditional Purépecha dances performed by groups from Tzintzuntzan’s K’uínchekua festival, an exposition of regional foods including the iconic pan de muertos, a photography expo that gives residents and visitors alike the rare opportunity of entering and seeing inside the exconvento, and cyclist tours leading to the mesmerizing cempasúchil fields.

This newly established festivity not only reimagines age-old customs but also introduces innovative elements that creatively reconnect with Copándaro’s indigenous roots while addressing contemporary community aspirations and challenges. Through exhibitions and community celebrations, the festival serves as a platform to rediscover and reclaim the cultural significance and intangible cultural heritage of Dia de los Muertos in Copándaro, including ofrenda-making, designing tapetes de asserín, visiting loved ones at the cemetery, and the symbolism of the cempasúchil flower (Figs 8 and 9).

Figure 7.

The main plaza comes alive with large-scale altares and tapetes de asserín (sawdust carpets) designed by local schools, creating a spectacular display.6

Figure 8.

Close up of contestants running for best catrina costume during El Festival de las Almas y las Flores.7

During an in-person interview last summer, Javier Álvarez García, Director of Culture, Tourism, and Education, emphasized the struggle in forming a culturally relevant identity for the people of Copándaro. He highlighted the lack of information Copandarenses have about their Purépecha history and their apathy towards reconnecting to it. Javier provided a compelling explanation behind the festival’s creation, illustrating a notable example from neighboring towns like Cucuchucho, Santa Fe de la Laguna, and Tzintzuntzan, where Purépecha traditions, especially those associated with Day of the Dead, are still vibrant:

Figure 9.

Group of dancers dressed in traditional Purépecha outfits during El Festival de las Almas y las Flores.8

Around 2014–2015, I had the opportunity to visit them before the boom began with the movie Coco and even back then, you began to see people there at 3:00 in the morning who were from Italy, who were from the United States, who were from all over the world. So that impressed me, because you see the infrastructure of those towns and it is even smaller than that of Copándaro. So that’s when it occurred to me to start promoting the municipality through its flowers, because I thought, well that’s where the richness of what traditional tombs are, what the tradition of the Day of the Dead is. It is very beautiful to visit there, even when you arrive at 3:00 in the morning, they receive you with tamales, they receive you with atole; it is a cultural tradition that the inhabitants have well-established. And I think that at some point that was lost for Copándaro …I wanted to recover that, but more through a focus on the tradition of growing the flower (J.A. García, personal communication, July 27, 2023).

With this in mind, Javier aspired to reclaim Copándaro’s indigenous roots and empower his community, reimagining it as the “Municipality that fills the tradition of the Day of the Dead in Michoacán with life and color.” His research, observations, and passion for preserving Copándaro’s legacy are greatly reflected in the success of this new festivity.

As the Director of Culture, Tourism, and Education for the 2021–2024 governmental team of Copándaro, Javier aimed to create an empowering, resonating communal identity, centering on the cultivation and celebration of the cempasúchil flower. With an intimate understanding of the significance of cultivating cempasúchil as a tradition passed down through generations of local families, including his own, Javier initiated a festivity that strengthened ties with residents. According to El Sol de Morelia (2023), Copándaro has over 200 agricultural residents who cultivate cempasúchil. This emblematic flower has finally gained recognition, attracting international visitors who contribute to the local economy and raise awareness of the municipality’s cultural heritage. La Voz de Michoacán (2022) reported that the first Festival de las Almas y las Flores resulted in one of the leading cempasúchil cultivators, José Manuel, selling three thousand bunches to various buyers in Querétaro, Jalisco, Lázaro Cárdenas, and La Catedral de Morelia. The resurgence of Dia de los Muertos in Copándaro is not only an empowering and healing ceremony but also a vibrant celebration that ignites the community’s cultural renaissance.

Like the revival of Dia de los Muertos during the 70s in LA, this festival has brought family history and cultural beliefs together, reuniting families through altars. In the process of creating an altar in my own home, my parents also gained interest in doing the same in their home, learning about the significance of each altar element along the way. The creation of meaningful altares and ofrendas serves as a powerful manifestation of integrating fragments of the past with contemporary expressions in Copándaro’s identity journey. As Venegas (2000) highlights, “Beyond their functional yet spiritual purposes, altares and ofrendas can be read as a visual narration of cultural negotiation, whereby fragments of the past are integrated with contemporary political, spiritual, and creative statements about cultural survival and invention” (p. 52).

My abuelita Llellita also explained how Dia de los Muertos was before, highlighting the extent to which it had been diminished:

Before, only one or two people would come down from the ranches to carry a bunch of flowers, one of those shiny paper crowns …and now there are bunches of flowers and crowns and crosses and on the tombs there are many little roofs, there are many tombs in the cemetery that are very beautiful with flowers that day. Already a day before, when it Is Dia de los Angelitos …And now people eat. They make enchiladas outside on the street, tacos and ice cream and all the foods (L. Herrejón Martinez, personal communication, February 25, 2024).

Similarly, Javier expressed:

Why don’t we have that attachment for growing the flower, for appreciating what we have? If in other places they sell the flower at ten times the price than what it’s sold here …and here, we see it with a question of contempt, like that flower smells bad. There were even many comments before, but now, there are not as many as before, the cempasúchil flower is valued more and I think that is the value that sometimes …by appreciating more of what they have elsewhere, we do not value what we have and that is why we are becoming a town that is …disposable, for lack of better words (J.A. García, personal communication, July 27, 2023).

Reflecting on these testimonios uncovers the complexity of cultural heritage preservation and offers insights on the power of hegemonic archival practices and the detrimental effects they had on the community of Copándaro de Galeana. As expressed by my abuelita and Javier, the lack of stories on the historical and cultural significance of cempasúchil and practice of Dia de los Muertos ceremonies and rituals resulted in apathy, stripped pride of an agricultural community, and a disconnect and displacement from Purépecha indigeneity. The archived 16th-century manuscript deeply affected Copándaro’s historical scholarship, collective memory, national identity, knowledge of self, knowledge as a group, and knowledge as a society.

The act of altar making, highlighted during the Festival de las Almas y las Flores in Copándaro, serve as rasquache and creative tools, empowering and decolonizing spirituality and Catholicism. The festival embodies the transformation of altar- and ofrenda-making into not only familiar objects but also an art form, bringing people together and reigniting Copándaro’s cultural identity through resistant knowledges. The cempasúchil-focused nature of the altares and ofrendas serves as a visual narration of cultural negotiation, whereby fragments of the past are integrated with contemporary political, spiritual, and creative statements about cultural survival and invention.

Through the revival of Dia de Los Muertos practices, our families have reconnected with our heritage and cultural identity. As discussed by Ybarra-Fraustro (n.d.), Our rasquache altares – adorned with recuerdos (flowers or favors saved from a party), crucifixes, portraits of La Virgen de Guadalupe, saint prayer cards, rosaries, flowers, photographs, and candles – and family-made crafts have become personal expressions of devotion and aesthetic vocation, serving as a cumulative historical narrative for our families (p. 2). These altares and ofrendas, once forgotten through centuries of assimilation, now stand as symbols of multivocal exchange and mediators between traditions and change.

The Festival de las Almas y las Flores has become a platform for Copándaro to reclaim its intangible Dia de los Muertos cultural heritage, fostering a renewed sense of pride and community identity through the celebration of its traditions and the empowerment of its people.

7.Next steps

El Carnaval and El Festival de las Almas y las Flores are not merely celebrations; they are profound expressions of Copándaro’s rich intangible cultural heritage and resilience. These festivals embody the community’s ongoing journey of cultural reclamation, survival, and empowerment, extending to Copandarenses in the US. Through this process of re-search and family testimonios, my parents and I reclaimed the historical significance of our motherland and its ties to indigenous practices, a narrative that had been forgotten.

The positive impacts of these festivals are undeniable. They have stimulated economic revitalization, especially for local agricultural workers, and have fostered a sense of self-worth and value among the community members. These events have reconnected the people of Copándaro with their history and land, creating a collective identity that is recognized at both state and national levels. The documentation and use of modern technology ensure that these traditions will continue to thrive and reach future generations.

While celebrating these achievements, it’s important to be mindful of the potential challenges, particularly the detrimental side of indigenismo. As Copándaro gains recognition, it must navigate the fine line between cultural appreciation and commercialization, ensuring that community building remains the priority over capitalistic exploitation. The romanticization of indigeneity, the risk of indigenous appropriation, and the pressures of gentrification and non-sustainable tourism are real concerns. Maintaining a balance between cultural preservation and sustainable tourism is essential to safeguarding Copándaro’s unique identity and heritage for future generations. How can we avoid such a powerful and pivotal moment in Copándaro’s identity formation from becoming a catalyst to the municipality’s gentrification in the future? This question underscores the need for careful planning and thoughtful decision-making to preserve the authenticity and integrity of Copándaro amidst its growth and development. Looking ahead, fostering greater community involvement in planning festivities and cultural events is paramount. Establishing collaborative community groups dedicated to preserving and sharing cultural legacies will empower residents to shape Copándaro’s future while safeguarding its heritage. However, critical questions emerge regarding the balance between growth and identity preservation. How can Copándaro navigate recognition and growth without succumbing to gentrification or over-tourism? Addressing these challenges requires collective effort and thoughtful deliberation to chart a sustainable path forward while honoring the essence of Copándaro’s unique cultural identity.

In conclusion, the festivals of Copándaro illustrate the enduring spirit and adaptability of the community. They are a celebration of survival, creativity, and empowerment, honoring the past while forging a dynamic and inclusive future. Through these vibrant expressions, Copándaro continues to write its own story, one that is deeply rooted in tradition yet ever-evolving, resilient, and full of promise.

References

[1] | Acueducto Online. ((2020) , February 26). Un hombre de carácter en el carnaval de Copándaro. Acueducto Noticias. https://acueductoonline.com/un-hombre-de-caracter-en-el-carnaval-de-copandaro/. |

[2] | Critical Race Theory Collective. ((2023) ). Call for papers 2024 special issue. Resistant Knowledges: Unmasking coloniality through the re-search of local to global communities. https://crtcollective.org/call-for-papers-2023-2024/. |

[3] | Data México. ((2020) ). Copándaro. Data México. https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/en/profile/geo/copandaro. |

[4] | Delgado, R. ((1989) ). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. Michigan Law Review, 87: (8), 2411-2441. doi: 10.2307/1289308. |

[5] | Dorval, A.R. ((2023) ). An introduction to Dr. Husam Khalaf’s ‘the Cultural genocide of the Iraqi archives and Iraqi Jewish archive and international responsibility’. Information & Culture, 58: , 8. |

[6] | Dunbar, A.W. ((2023) ). Every information context is a CRiTical race information theory opportunity: Informatic considerations for the information industrial complex. Digital Transformation and Society, 2: (4), 356-375. doi: 10.1108/DTS-02-2023-0013. |

[7] | Dunbar, A.W. ((2006) ). Introducing critical race theory to archival discourse: Getting the conversation started. Arch Sci, 6: , 109-129. doi: 10.1007/s10502-006-9022-6. |

[8] | El Colegio de Michoacán, A.C. ((2008) ). Relación de Michoacán: Instrumentos de consulta. http://etzakutarakua.colmich.edu.mx/proyectos/relaciondemichoacan/creditos/creditos.asp. |

[9] | Gobierno de Michoacán. ((2023) , February 14). Estos son los carnavales que puedes vivir en Michoacán. SECTUR. https://sectur.michoacan.gob.mx/estos-son-los-carnavales-que-puedes-vivir-en-michoacan/. |

[10] | Gobierno Municipal Copándaro 2021–2024 ((2024) , February 10). !‘Felicidades a Cintia González por convertirse en la nueva Reina de Carnaval! Acompañada por nuestras princesas Fernanda Barcenas, Vanessa Rico [Images attached][Post]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=pfbid0nCozcFzCryZyTYEJMtZgDDunmqyjNuwUxEAfb12mXrRiP48e3xXzmPJdvtsGmb31l&id=100067207543717. |

[11] | Indigenismo. ((2024) , February 29). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigenismo. |

[12] | La Voz de Michoacán. ((2022) , March 1). Los toritos de petate: conoce el origen de una de las festividades más tradicionales de Michoacán. La Voz de Michoacán. https://www.lavozdemichoacan.com.mx/michoacan/los-toritos-de-petate-conoce-el-origen-de-una-de-las-festividades-mas-tradicionales-de-michoacan/. |

[13] | Lizama, J.T. ((2018) ). Cultural Heritage Components. In Salvatore, C.L. Cultural Heritage Care and Management: Theory and Practice, Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 5-6. |

[14] | Mesa-Bains, A. ((1993) ). Art of the other Mexico: Sources and meanings |

[15] | Rodriguez-Campo, M. ((2021) ). Testimonio in education. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education.https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-1346. |

[16] | Secretaría de Turismo del Estado de Michoacán ((2023) , February 14). Estos son los carnavales que puedes vivir en Michoacán. Secretaría de Turismo: Gobierno de Michoacán. https://sectur.michoacan.gob.mx/estos-son-los-carnavales-que-puedes-vivir-en-michoacan/. |

[17] | Seriff, S., & Limón, J. ((1986) ). Bits and pieces: The Mexican American folk aesthetic. Art Among Us |

[18] | Solórzano, D.G., & Yosso, T.J. ((2002) ). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry, 8: (1), 23-44. doi: 10.1177/107780040200800103. |

[19] | Spears-Rico, G. ((2015) ). Consuming the Native Other: Mestiza/o Melancholia and the Performance of Indigeneity in Michoacán. |

[20] | The University of Texas at Austin: University of Texas Libraries (n.d). Spiritual conquest. A New Spain. https://exhibits.lib.utexas.edu/spotlight/a-new-spain/feature/spiritual-conquest. |

[21] | Venegas, S. ((2000) ). The day of the dead in Aztlan: Chicano variations on the theme of life, death and self-preservation. Chicanos en Mictlán: Día de los Muertos in California, 42-54. https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/809718#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-805%2C-1%2C4158%2C3300. |

[22] | Ybarra-Frausto, T. ((1989) ). Rasquachismo: a Chicano sensibility. Chicano aesthetics: Rasquachismo, 5-8. https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/845510#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-557%2C-1%2C2769%2C2198. |

[23] | Ybarra-Frausto, T. (n.d.) Sanctums of the spirit: The altars of Amalia Mesa-Bains. Unpublished Manuscript, 7. https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/1086152#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-576%2C543%2C3465%2C2750. |