Pre-employment transition services for students with disabilities: A scoping review

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Students with disabilities often experience numerous challenges in terms of finding employment. Given the important role of vocational rehabilitation counselors in supporting employment activities for these students, a need exists for identifying effective strategies that increase employment outcomes for this population.

OBJECTIVE:

The objective of this scoping review is to examine and describe successful research- based interventions on pre-employment transition services for students with disabilities that can be used by vocational rehabilitation counselors.

METHODS:

The search strategy examined literature from 1998 through 2017 focused on vocational rehabilitation counselors, students with disabilities, and elements related to pre-employment transition services. Articles included American, European, and Australian literature published in English.

RESULTS:

This review identified a number of research-based interventions that support employment outcomes for students with disabilities.

CONCLUSIONS:

The research-based interventions identified in this scoping review can help vocational rehabilitation counselors consider effective strategies for increasing employment outcomes for students with disabilities.

1Introduction

People with disabilities experience substantial ch-allenges in terms of employment rates, wages, adv-ancement, workplace barriers, accommodations and supports (Bouck & Joshi, 2015; Crudden, 2012; Dong, Fabian & Leucking, 2016). The National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) found that among youth with disabilities who had been out of high school 1 to 4 years, 58 percent worked full time at their current or most recent job (Newman et al., 2009). In contrast, almost 80 percent of transition-aged youth without a disability and not enrolled in high school were employed (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017).

For people with a disability, typical targeted outcomes for employment include finding a position in the competitive labor market, job stability, wages and benefits on a par with other employees who do not have a disability, hours worked, and job satisfaction. While most of these are common to any job seeker or employee, the degree of success in achieving any one of the outcomes can be impacted by the type and severity of the disability. According to the NLTS2 study, individuals diagnosed with disabilities related to learning, speech/language, hearing, or mental health were significantly more likely to be employed after high school than individuals diagnosed with disabilities related to intellectual, visual, orthopedic or orthopedic functions, autism spectrum disorder, traumatic brain injury, or who had multiple disabilities or deaf-blindness (Newman et al., 2009).

To improve employment outcomes for people with disabilities, vocational rehabilitation (VR) counseling has been identified as a key component to support transition-aged youth in obtaining employment. The U.S. Department of Education found that among persons who achieved an employment outcome because of VR services, 76 percent were still working three years after exit compared to 37 percent of people who were eligible for VR services but did not receive them (Hayward & Schmidt-Davis, 2003).

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), which amended the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, now requires VR agencies to set aside at least 15 percent of their federal funds to provide “pre-emp-loyment transition services [to] students with disabilities who are eligible or potentially eligible for VR services” (Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014). These five required pre-employment transition services (Pre-ETS) comprise five service elements.

1.1Job exploration counseling

Job exploration counseling includes activities to foster career awareness, to help a person understand how personal work-related values apply to emp-loyment options. It can focus on building a person’s understanding of the skills and qualifications necessary for specific careers. It may also include attending talks given by speakers who discuss specific careers, or participating in career organizations. Job exploration counseling excludes assessments that evaluate whether someone can receive VR. In general, job exploration counseling includes helping students with disabilities discover:

• Vocational interests (often through an inventory)

• Potential careers and career pathways of interest to the students

• Activities to recognize the relevance of a high school and post-school education to their futures, both in college and/or the workplace

• The labor market, particularly industries and occupations in high demand, and non-traditional employment options (Interwork Institute, 2016a).

1.2Work-based learning

Work-based learning experiences include the following types of activities:

• Informational interviews

• Career-related competitions

• Learning about careers through simulated workplace experiences or workplace tours/field trips

• Apprenticeships (which combine in-school and work-based learning)

• Job shadowing or career mentoring (when a peer or experienced person provides guidance about a job)

• Paid work experiences, including internships or employment

• Unpaid work experiences including internships, volunteering, and service learning (Interwork Institute, 2016b).

While practicums and student-led enterprises are included in work-based learning, they are excluded from this scoping review since they are performed in a school setting.

1.3Counseling on opportunities for enrollment in comprehensive transition or postsecondary educational programs

Counseling on these specific opportunities may include providing information on: course offerings; career options; the types of academic and occupational training needed to succeed in the workplace; postsecondary opportunities associated with career fields or pathways; academic curricula; and college and financial aid process and forms (Jamieson et al., 1998).

The goal of this scoping review was to focus on employment outcomes for students with disabilities. Since this category focuses on post-secondary outcomes, it was omitted from this review so as to focus the review on studies targeting youth prior to exiting secondary school.

1.4Workplace readiness training to develop social skills and independent living

Workplace readiness training refers to common social skills used in employment. These skills support appropriate interactions with managers and colleagues and are common across all workplace environments (Interwork Institute, 2016c). This scoping review focuses on those skills necessary to succeed in employment, and excludes those specific to independent living. Examples of social skills relevant to employment may include but are not limited to:

• Engaging in effective and professional communication skills—including timely, respectful and professional listening and self-expression

• Understanding employer expectations for punctuality and performance

• Cooperating with and supporting others as part of teamwork

• Maintaining a positive attitude

• Making decisions and problem solving (Interwork Institute, 2016c).

Independent living skills, such as having a healthy lifestyle, developing friendships, and knowing how to prepare meals are not included in this scoping review because they are not necessarily prerequisites to success in workplace settings.

1.5Instruction in self-advocacy

Self-advocacy refers to a person’s capacity to communicate and negotiate his or her interests (Interwork Institute, 2016b). Self-determination refers to a person’s ability to determine and plan for the future based on those personal interests and values. In the case of this scoping review, we focus on self-advocacy and self-determination as related specifically to the ability to seek accommodations in the workplace. These skills include: understanding oneself, one’s disability; the capacity to know when and how to disclose about one’s disability; decision-making; being able to identify necessary accommodations in the workplace; knowing how to request and use accommodations and any necessary assistance; and understanding one’s rights and responsibilities.

These five-pre-employment transition (pre-ETS) service components guided our organization for sum-marizing research literature, with the goal of informing the state of literature regarding employment of students with disabilities.

2Objective

Since VR counselors are required to provide pre-ETS to eligible students with disabilities, it is important that they are aware of research-based practices respective to each of the five required areas. The objective of this scoping review is to examine and describe successful interventions related to the five required pre-ETS areas.

3Method

3.1Data sources and searches

The search strategy examined literature from 1998 through 2017 focused on VR counselors, students with disabilities, and elements related to pre-ETS. The start date of 1998 was selected because the Workforce Investment Act was authorized that year. It supported local activities to increase employment rates, including reauthorizing the 1973 Rehabilitation Act; thus, the research, strategies, and tools found post-1998 would likely be more relevant to VR professionals.

The search strategy followed the three-step method described in the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI’s) methodology of scoping reviews: 1) a search using the terms ‘youth’ or ‘students’, ‘disability’, and ‘employment’; 2) using all identified keywords and index terms (see Appendix A.1.) in all included library databases; and 3) searching the reference lists of all identified reports and research articles for additional studies. The review focused solely on literature and toolkits written in English. The literature and the toolkits primarily came from the United States, and included those from Canada, Europe, Australia as potential articles because these other geographic areas are thought to have similar issues and supports.

The sources of the included studies were drawn from the following databases: Education Resource Information Center (ERIC), Education Source, Psy-chINFO, Soc INDEX, Academic Search Premier, PubMed, and National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, Research and Rehabilitation (NID-ILRR) project websites identified by searching the database of NIDILRR awards maintained by the Nat-ional Rehabilitation Information Center (NARIC). The gray literature search was conducted through a broad google search using the same inputs selected for the research articles (youth’ or ‘students’, ‘disability’, and ‘employment’). Rehabilitation Services Administration technical assistance websites, such as the Workforce Innovation Technical Assistance Center (WINTAC) that the Rehabilitation Services Administration funds, were also searched for additional gray literature.

3.2Eligibility criteria for review

From the articles gathered, only research, research-based tools, and gray literature that support VR counselors with at least one of the four elements of Pre-ETS covered in this review. Any article that did not meet the eligibility criteria was excluded from this review.

3.3Data extraction

Two independent reviewers assessed all abstracts and titles for relevance using the same inclusion criteria. Screening results from reviewers were compared for interrater reliability and all discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third and senior coder. If the reviewers were unsure about the title and abstract description, the citation was advanced to the full text stage, retrieved, and the inclusion decision determined reviewing the full text. Once the list of included studies was determined, a full text of each study was retrieved, and the team extracted relevant data using a predetermined data charting form to guide the process (see Appendix A.2.).

4Results

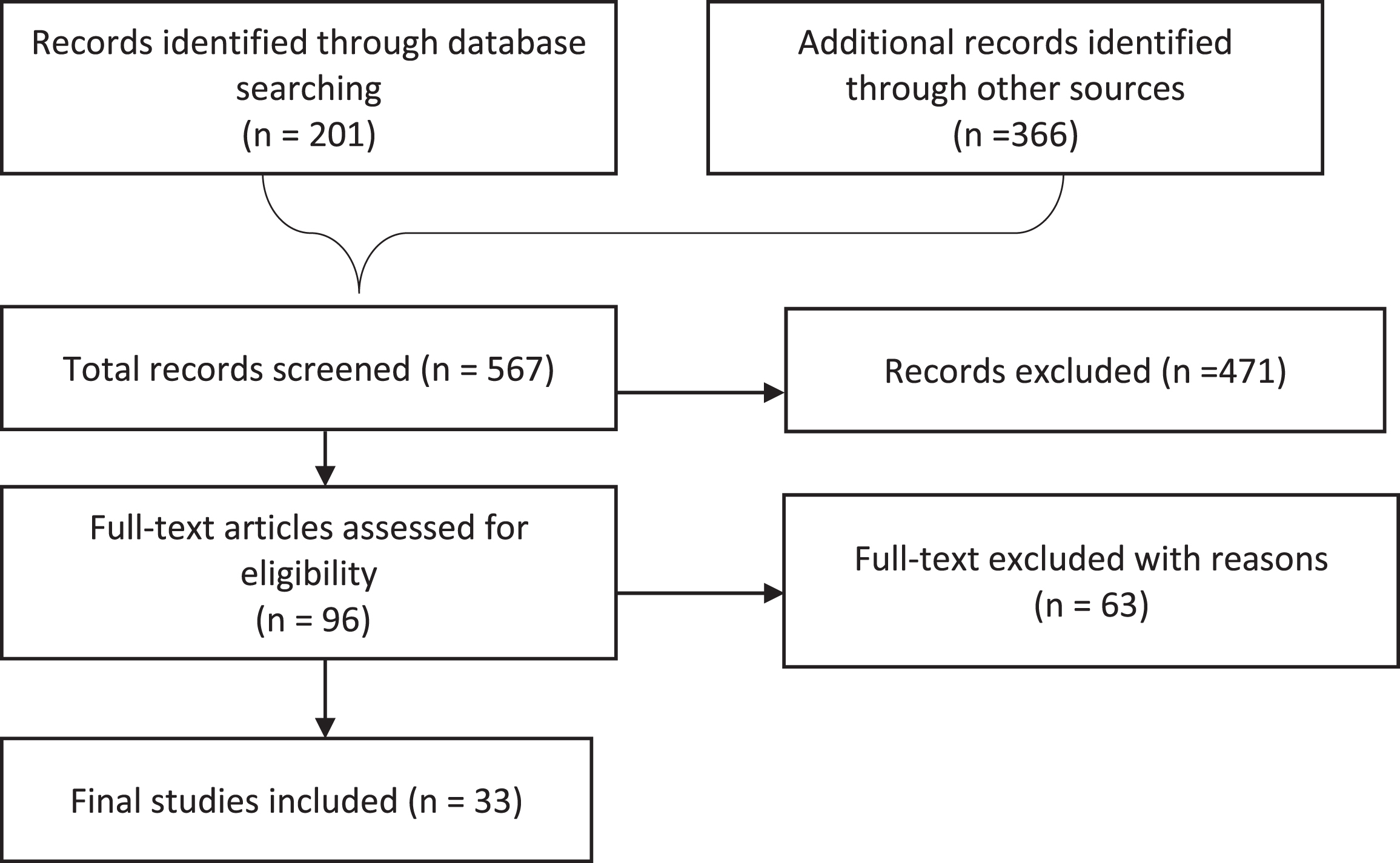

Two reviewers, independent of each other, charted two to three studies to become familiar with the source results and to trial the data. This process ensured that all relevant information was extracted. After the two reviewers familiarized themselves with the charting form, they extracted the data independently from each other. After screening 567 records and excluding 471 of them, 96 full text articles were extracted and assessed for eligibility. Of these 96 articles, 63 of them did not meet the eligibility criteria and were excluded, for a final total of 33 articles. Figure 1 illustrates the results of the decision process for the selection of the included studies; (for more information on included studies by year, country, and design please see Appendix A.3).

For each of the four Pre-ETS service elements covered in this review, the research team identified themes to capture the various strategies that fall under each element. These themes were established during the full text review after the reviewers observed distinct groups of strategies being referenced across articles. After grouping the strategies into themes across articles, each reviewer was assigned two or more themes to assess whether they corresponded to the Pre-ETS service elements. Afterwards, a group discussion took place where each reviewer explained how each of their assigned themes related or did not relate to the service categories. Any disagreement among potential themes were discussed and resolved by a third reviewer.

Fig. 1

PRISMA flowchart of data extracted.

The following were the themes established for each of the WIOA categories covered in this review along with the rationale for their inclusion:

Job exploration counseling

• Career goal development –the development of career goals may help individuals with disabilities discover their ideal work life and is an activity that VR professionals may help guide and direct.

• Family outreach –family members of students with disabilities can provide unique perspectives and insights, which may help VR professionals facilitate the job exploration process.

• Cultural competence –the cultural context of students with disabilities may influence their career aspirations. Because of this, understanding a stu-dent’s cultural context may allow VR professionals to better assist with job exploration.

• Interagency collaboration –working with stakeholders (i.e., school personnel) to direct career activities may help students explore careers (Fa-bian, 2007).

• Previous or early work experience –early work experience is a significant predictor of employment. Helping students find work-based learning opportunities while in school may increase employment opportunities.

• Supplemental Security Income (SSI) payments –SSI payments may act as barriers to employment for students with disabilities. Being aware of these barriers may help VR professionals navigate employment issues related to SSI.

• Work-based social supports –providing social supports such as work-based mentoring may lead to higher employment outcomes for students with disabilities.

• Communication/interview skills –developing the skills necessary to communicate and perform well in interviews is an important factor for work place readiness.

• Social skills support –these are skills that allow for productive social interactions with colleagues and customers and are important to develop before entering the workforce.

• Transportation –helping students with disabilities overcome barriers to transportation may lead to higher workplace outcomes.

• Disclosure and disability awareness –helping students with disabilities understand the risks and benefits of disclosure is an important aspect of self-advocacy.

• Workplace accommodations and rights –helping students how to identify needed accommodations to support gainful employment is a skill related to self-advocacy.

• Self-determination –these skills include self-esteem, decision-making, problem-solving, and job-seeking skills and can help students with disabilities find employment.

4.1Job exploration counseling

A total of 15 studies addressed job exploration counseling and evidence-based interventions that can improve employment outcomes for students with disabilities. These topics and their implications were categorized across four themes: (1) development of career goals (n = 5), (2) family outreach (n = 5), (3) cultural competence (n = 4), and (4) interagency collaboration (n = 11). In the studies included many of the themes appear concurrently. As a result, the total number of studies in each of these thematic categories are greater than the total number of studies included.

4.1.1Career goal development

Career goal development involves setting clearly defined, measurable goals that depict a vision for one’s ideal work life. Five studies indicated that the development of career goals can help students with disabilities find employment after high school (Brewer et al., 2011; Fabian, 2007; Luecking & Lu-ecking, 2015; Jamieson et al., 1998; Rothman & Maldonado, 2008). Each of the five studies examined a program intervention that included goal development for students with disabilities as a component. One of the studies, which used a multivariate analysis, found that 68 percent of students with disabilities participating in the intervention secured jobs after finishing the career counseling and career assessment components of the program (Fabian, 2007). Though this specific study found no significant relationship between career goals and work outcomes, it did note that a substantial body of literature exists supporting the importance of concrete career goals and workplace efficiency (Fabian, 2007). Based on this study’s outcomes, Fabian (2007) recommended that VR counselors begin early in students’ educations to develop vocational goals.

Thresholds is an intervention that aimed to help students with disabilities make career decisions. In their evaluation of Thresholds, Jamieson et al. (1998) found that the program increased the vocational decision-making abilities of participants. A major component of the program included developing action plans to achieve career goals (Jamieson et al., 1998).

The Maryland Seamless Transition Collaborative (MSTC), an intervention designed to address key barriers to employment faced by students with disabilities, showed that a plurality of participating students had achieved key outcomes from the model’s framework at the point of transition (Luecking & Luecking, 2015). The MSTC model includes a component in which students work to together with pro-fessionals, family members, and friends to identify their employment interests and goals, which are subsequently documented in a personal profile (Luecking & Luecking, 2015).

The Model Transition Program from New York, which seeks to increase employment among students with disabilities at the point of transition, revealed a positive relationship between measurable postschool goals and postschool outcomes for students with disabilities (Brewer et al., 2011). Noticing a communication gap between high school counselors and VR counselors after evaluating a pre-college transition program in upstate New York, this study recommended a stronger collaboration between VR and high school counselors with a focus on developing students’ long-term career goals (Rothman & Maldonado, 2008).

4.1.2Family outreach

Family members play an essential role in the lives of students with disabilities and often want to be included in discussions involving employment. Learning from the unique perspective of family members may help VR professionals facilitate the job exploration process. Five studies emphasized the importance of family outreach regarding students with disabilities and the career exploration process (Crudden, 2012; Greene, 2014; Luecking & Luecking, 2015; Stone et al., 2015; Tilson & Simonsen, 2013). Three of the studies used a qualitative design, one used mixed methods, and one was a literature review. Researchers for two of the qualitative studies conducted interviews (Stone et al., 2015; Tilson & Simonsen, 2013). Stone et al. (2015) held interviews with 57 non-Hispanic and Hispanic students with disabilities and found that families are often underequipped to handle all the needs of their child, suggesting that family members should “work in conjunction with vocational staff members to facilitate the job process” (p. 462). Tilson and Simonsen held interviews with employment specialists and found that effective family communication strategies are an important component of their practice (2013). Similarly, in the third qualitative study (Crudden, 2012), researchers led focus groups with VR agency personnel to examine beliefs about effective service delivery practices. Focus group participants identified parental involvement as a positive factor in the transition and career planning process (Crudden, 2012). Another component of the MSTC intervention, as described in Luecking and Luecking’s mixed methods study in the section above (2015), involves early VR case initiation in which VR counselors work with the student and family to develop the Individualized Plan of Employment. The literature review (Greene, 2014) included in this theme explored transition outcomes for culturally and linguistically diverse students with disabilities and found that high numbers of these students will continue to be part of VR personnel caseloads for the foreseeable future. Because of this observed trend, Greene (2014) argued that transition personnel should work with the “broader cultural community of the family” (p. 243) when developing a comprehensive transition program for culturally and linguistically diverse students with disabilities.

4.1.3Cultural competence

Students with disabilities come from an array of diverse backgrounds with different cultural needs. The cultural needs of students with disabilities may influence their career goals. Because of this, it is important for VR counselors to understand the cultural context of the students they serve when facilitating the job exploration process. Four studies cited cultural competence as an important attribute for VR counselors (Awsumb, Balcazar & Maldonado, 2016; Greene, 2014; Stone et al., 2015; Tilson & Simonsen, 2013). Three of the studies used a qualitative design, and one used a quantitative design. Of these three qualitative studies, researchers in one study conducted interviews with employment specialists and found that cultural competence was an important attribute in their line of work: “The employment specialists in our study seemed committed to learning about the youth as individuals and understanding the cultural context in which the youth lived. They demonstrated cultural competence by considering the interconnectedness of environmental and situational factors that would influence the job placement and retention process” (Tilson & Simonsen, 2013, p.131). The two other qualitative studies we identified (Greene, 2014; Stone et al., 2015) cited cultural competence as an important factor when communicating with families of culturally and linguistically diverse students with disabilities. The one quantitative study included in this theme (Awsumb et al., 2016) used an observational analysis to examine the outcomes of students with disabilities participating in a transition program. This study stated that poverty and oppression, especially for minority students, creates barriers to emp-loyment opportunities and that “without the help of dedicated, knowledgeable, and effective counselors (either from VR or their high schools), these students will not be able to succeed” (p. 63).

4.1.4Interagency collaboration

Interagency collaboration focuses on getting stakeholders to solve problems together across multiple systems. Working together with stakeholders to direct career activities may help VR counselors facilitate the career exploration process. Eleven studies cited interagency collaboration between VR counselors and other stakeholders as a key factor in helping students with disabilities obtain employment (Awsumb et al., 2016; Dong et al., 2016; Fabian, 2007; Giesen & Cavenaugh, 2012; Izzo, 1999; Luecking & Luecking, 2015; Plotner et al., 2012, 2013; Povenmire-Kirk et al., 2015; Rothman et al., 2008; Tilson & Simonsen, 2013). The design of these studies ranged from quantitative (7), to qualitative (2), to mixed (2). One of the quantitative studies (Giesen & Cavenaugh, 2012) used a multiple logistic regression model to examine competitive employment outcomes for students with disabilities. It found that interagency agreements between VR agencies and local education agencies can be used as a framework to get students with disabilities involved early in transition planning (Giesen & Cavenaugh, 2012). Another quantitative study (Fabian, 2007) used a multivariate analysis to determine factors affecting transition employment in urban students with disabilities. One implication from the study’s findings is that VR counselors seeking to assist in the formulation of career-related activities and interventions work with special education and related personnel as early as possible. Similar findings were outlined in the other five quantitative studies included in this theme. For instance, Plotner et al. (2013) argue that stronger partnerships between schools and VR systems can positively impact counselor perceptions of transition activities. Dong, Fabian, and Luecking (2015) state that local school agencies and VR agencies working collaboratively can help address the employment gap students with disabilities face as they exit high school. Izzo (1999) maintains that for students with disabilities to experience smooth transitions into adult life, VR services must be coordinated with other educational services. Awsumb et al. (2016) concur that a working relationship between VR professionals, students with disabilities, the family, and the school is essential for a successful transition to adulthood. Plotner and colleagues (2012) similarly consider knowledge sharing and frequent communication as essential for VR professionals to perform the full scope of their duties.

As reported in the two qualitative studies, one team of researchers interviewed seventeen employment specialists and identified four personal attributes that support effective practices (Tilson & Simonsen, 2013). One of these attributes identified was ‘networking savvy’, which is the ability to connect with people and resources to create opportunities for students with disabilities (Tilson & Simonsen, 2013). Researchers involved in the second qualitative study (Povenmire-Kirk et al., 2015) conducted focus groups with key members of CIRCLES, which is a service delivery model that aims to improve interagency collaboration for transitioning students with disabilities. Members of the focus group felt that the CIRCLES’ framework improved the sense of collaboration and awareness of services available in their districts (Povenmire-Kirk et al., 2015). One of the mixed methods studies (Rothman et al., 2008) found that high school counselors should collaborate with VR counselors to match career goals to student strengths and abilities. The second mixed methods study (Luecking & Luecking, 2015) described system linkages and collaboration as a primary component of the MSTC intervention.

4.2Work-based learning

Twelve studies identified work-based learning as generally beneficial for future work, and that participation in it could affect outcomes in future work. Findings could be further broken down into three themes: (1) the importance of previous or early work experience (n = 8), (2) challenges surrounding Supplemental Security Income (SSI) payments (n = 4), and (3) the importance of mentoring and other social supports (n = 5).

4.2.1Previous or early work experience

Eight studies reported the value of previous or early work experience in supporting employment post-transition (Crudden, 2012; Giesen & Cavenaugh 2012; Fabian, Lent & Willis, 1998; Luecking & Wittenburg, 2009; Madaus, 2006; McDonnall, 2011; Simonsen & Neubert, 2012; Wehman et al., 2015). Of these, five studies were secondary data analyses and identified previous employment as strongly significant. Three studies reported that paid work during secondary school predicted employment following graduation (Giesen & Cavenaugh 2012; Simonsen & Neubert, 2012; Wehman et al., 2015).

Simonsen and Neubert (2012) note that students with disabilities who participated in paid work during school were 4.53 times more likely to participate in integrated employment. Likewise, Wehman et al. reported that employment in high school was the most significant predictor of post-high school employment (p = 0.0004) (2015). In addition, career awareness training (p = 0.0216) and attending a vocational school (p = 0.0151) is associated with post-high school employment (Wehman et al., 2015). McDonnall (2011) also finds early work experience to be a significant predictor of employment (p = .002) and, in addition, offers data showing that the number of jobs held to be an additional predictor. In her study, students with disabilities who held two jobs over the past two years were between 1.6 to 2.1 times more likely to be employed than those who held no jobs in the two years before the survey (McDonnall, 2011). Finally, in an analysis of the Marriott Foundation’s “Bridges from school to work” program, students’ work-related behaviors were the best predictors of paid employment following internship completion (Fabian et al., 1998).

The three qualitative studies each identified the skills learned in “practical on-the-job situations” as the primary benefit of work-based learning (Mad-aus, 2006). One article offers three case studies that demonstrate how on-the-job experience can translate into employment following the end of a school-based employment intervention (Luecking & Wittenburg, 2009). While participants in all these studies cited internships or other time-limited transitional employment as a good way to gain this experience, VR counselors who participated in a series of focus groups recommended developing and practicing interviewing, communication, and job readiness skills in a variety of different ways (Crudden, 2012). These included: camps, summer jobs, school-sponsored work activities, after-school employment, volunteer work, job shadowing, supported employment, on-the-job trainings, and internships (Crudden, 2012).

4.2.2Supplemental security income payments

Supplemental Security Income payments may act as barriers to employment for students with disabilities. Being aware of these barriers may allow VR professionals to more effectively assist students with disabilities in exploring careers. Four studies discussed the role that SSI plays in encouraging or discouraging employment among students with disabilities (Giesen & Cavenaugh, 2012; Hemmeter, 2014; Luecking & Wittenburg, 2009; McDonnall, 2011). Of these, one was a randomized controlled trial (RCT), one was a series of case studies, and two were secondary data analyses. The RCT and the case studies were both part of the same program evaluation of the Social Security Administration’s “Youth Transition Demonstration” project (Hemmeter, 2014; Luecking & Wittenburg, 2009). The Youth Transition Demonstration recognized the limits on earning potential that accompany SSI payments as a fundamental barrier to participant employment, and so structured the program around this recognition. Because the purpose of the project was to identify interventions that would improve the educational and vocational outcomes with youth who qualify for SSI payments, or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) payments, Youth Transition Demonstration supplied participants with waivers of certain SSI and SSDI rules that limit SSI eligibility for those over a certain threshold of income. In the RCT, “the program waivers allow the treatment group youths to keep more of their income and remain in the program longer than the control group youths. Combined with the earnings results, the waivers may indicate better employment outcomes for treatment group youths” (Hemmeter, 2014, p. 21). However, because the intervention is still underway, it is too early to determine the overall effectiveness of the Youth Transition Demonstration. The case studies support this conclusion by illustrating three successful examples of the Youth Transition Demonstration (Luecking & Wittenburg, 2009).

Of the two studies that were secondary data analyses, the first found that receipt of SSI income payments at the time of application was a significant negative predictor of employment (Giesen & Cavenaugh, 2012). However, Giesen and Cavenaugh (2012) also note that the receipt of SSDI, which is available only to persons who have worked for a cer-tain amount of time, does not have a negative association with employment. Likewise, the second study examined predictors of employment in students with disabilities with visual impairments (McDonnall, 2011). While this study found the receipt of SSI benefits to be a significant negative predictor on its own, the recent receipt of SSI benefits was much less significant when considered in combination with other variables. Because the receipt of SSI benefits is a major barrier to employment for people with visual impairments, the author suggests that these barriers may be more significant to older adults with visual impairments. McDonnall (2011) suggests that this discrepancy could be indirectly caused by persons with visual impairments being prevented from gaining early work experience when they were younger because of receiving SSI payments.

4.2.3Mentoring and other work-based social supports

Five studies, four of which were qualitative, cited the importance of work-based social supports—including mentoring, role models, or other work-based advocates—as a factor that supports successful employment (Crudden, 2012; Lindsay et al., 2012; Madaus, 2006; Stone et al., 2015; Verhoef et al., 2014). Two qualitative studies identified mentoring as beneficial to transitioning into employment (Lindsay et al., 2012; Madaus, 2006). When asked how transition services could be improved, survey respondents suggested that their colleges establish mentoring programs between current students and graduates with disabilities, which they felt would allow students to see what can be achieved (Madaus, 2006). Likewise, participants in the study conducted by Lindsay et al. (2012) reported increased self-confidence following an employment-training program, which some youth attributed to their contact with peer-mentors. Furthermore, both parents and youth in the study expressed that they would have liked to continue with a mentor or buddy system after the program ended. One study conducted focus groups with VR counselors (Crudden, 2012). Participants in these focus groups suggested providing visually impaired youth with role models who are both blind and sighted as a means of developing positive social skills (Crudden, 2012). Another study (Verhoef et al., 2014), while it did not evaluate for mentoring specifically, included mentoring as a component in an intervention that was ultimately found to result in improved occupational performance, self-care, and satisfaction with performance. Finally, most participants in Stone et al. (2015) believed that it would be beneficial for their supervisors to be aware of their disability, as they felt that this would result in more access to workplace supports and accommodations, social or otherwise.

4.3Instruction in self-advocacy

A total of 15 included studies addressed topics related to self-advocacy and self-determination. Specifically, the content, findings, and implications related to this topic were categorized across three themes: disclosure (n = 5), workplace accommodations (n = 5) and self-determination (n = 10).

4.3.1Disclosure and disability awareness

Five studies support the importance and training of students with disabilities in the process, risks, and benefits of disclosure (Lindsay & DePape, 2015; Lindsay et al., 2012; Lindsay, McDougall & Sanford, 2013; Newman et al., 2016; Rothman & Maldonado, 2008). One of the studies (Newman et al., 2016) used data from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS-2), which represents thousands of students with disabilities, to examine if transition planning in high school later helps students request accommodations in a postsecondary setting. The authors note that transition plans need to reflect reasonable accommodations that students with disabilities can request and control in educational settings, which VR counselors can help inform (Newman et al., 2016). A survey of 27 students with disabilities attending a pre-college summer transition program found that students with disabilities are often reluctant to disclose their disability due to fear of stigma and bias (Rothman et al., 2008). At the same time, Rothman and Maldonado (2008) reported that participants reported that self-advocacy as the most important contributor to their success in future employment.

The team led by Lindsay et al. (2012) conducted semi-structured interviews with eighteen students with disabilities that participated in a skills development training program, which included practicing how and when to disclose a disability. Some of the participants concluded that working helped them practice explaining their condition and need for accommodations (Lindsay et al., 2012). Similarly, in another study Lindsay et al. conducted interviews to determine if students with disabilities disclose their disability (2013). Fourteen of the 18 participants who had participated in a 2-year employment training program reported difficulty in knowing how to disclose their condition prior to taking the job. The authors suggest that their study reveals the importance and need for disclosure skills in students with disabilities. Another study conducted interviews to explore how answers given during job interviews differ between students with disabilities and their peers without disabilities (Lindsay & DePape, 2015). The authors state some research has shown that students with disabilities are rated more favorably by potential employers when they disclose their condition early during job interviews. However, Lindsay and DePape (2015) also warn that disclosing disabilities can harm potential job prospects if the employer has negative attitudes toward people with disabilities.

4.3.2Workplace accommodations and rights

Three studies identified workplace accommodations as a factor that supports successful employment for students with disabilities (Crudden, 2012; Lindsay et al., 2013; Rothman & Maldonado (2008)). Two of these studies (Crudden, 2012; Lindsay et al., 2013) used a qualitative design. Both studies found that students with disabilities needed to be engaged in self-ad-vocacy activities sufficiently to identify needed acc-ommodations to support gainful employment and/or to understand their rights with respect to possible on the job discrimination actions. Another study (Rothman & Maldonado, 2008) addressed students with disabilities’ transition to college life and assessed the effects of a one-week program that addressed issues related to advocacy skills and seeking accommodations. Exit interviews with the students indicate that they found the one-week program to be beneficial (Rothman & Maldonado, 2008).

4.3.3Self-determination

Eleven studies examined the importance of self-determination for students with disabilities in obtaining employment (Bal et al., 2017; Brewer et al., 2011; Carter, Austin & Trainor, 2011; Crudden, 2012; Greene, 2014; Foley et al., 2012; Luecking & Wittenburg, 2009; McDonnall, 2011; McDonnall & Crudden, 2009; Newman, et al., 2016; Simonsen & Neubert, 2012). 1Six of the studies (Brewer et al., 2011; Carter et al., 2011; McDonnall, 2011; McDonnall & Crudden, 2009; Newman et al., 2016; Simonsen & Neubert, 2012) were quantitative and used data drawn from state and national databases to analyze the impact of self-determination training such as goal setting, job seeking and choices, decision-making, problem-solving, job seeking/readiness skills and job choices on successful employment. Each of these six studies highlight the link between self-determination training/skills and successful employment for students with disabilities. For example, Brewer et al. (2011) found that the more students were involved with career development activities, which include self-determination training, the more likely they were to participate in work-related experiences. Similarly, McDonnall and Crudden (2009) found that self-determination skills were associated with greater employment outcomes for visually impaired students upon transition. Three of the studies (Bal et al., 2017; Crudden, 2012; Luecking & Wittenburg, 2009) were qualitative in design. Each three of these studies acknowledge that self-determination factors such as self-esteem, decision-making, problem-solving, and job-seeking skills can help students with disabilities find employment. The last two studies were literature reviews. The first literature review (Foley et al., 2012) found evidence that students with disabilities who exhibited more self-determination demonstrated more advanced outcomes in many employment categories. The study’s authors concluded that more service models are needed to promote the success of students with disabilities (Foley et al., 2012). Finally, Greene (2014) summarized the literature on cultural/linguistic sensitivity in relation to self-advocacy and self-determination. Greene (2014) concluded that students with disabilities from minority cultures/languages face unique challenges (i.e., racial and cultural stereotypes, immigration issues, lack of language proficiency) with respect to self-advocacy and self-determination and that special attention should be given to the development of these skills in the context of the student’s cultural/linguistic identity.

4.4Workplace readiness

Nine studies present results relating to work read-iness social skills and independent living. Multiple outcomes were identified and classified according the following three themes: (1) communication/interview skills (n = 7), (2) social skills (n = 6), (3) and transportation (n = 6).

4.4.1Communication/interview skills

Seven studies found that communication/interview skills can help students with disabilities obtain emp-loyment (Carter et al., 2011; Crudden, 2012; Lindsay & DePape, 2015; Lindsay et al., 2012; McDonnall, 2011; Stone et al., 2015; Verhoef et al., 2014). Of the seven studies, two used a quantitative analysis of the NLTS2 database (Carter et al., 2011; McDonnall, 2011). Carter et al. (2011) found that students with disabilities who communicated well with others and were independent in self-care had nearly three times the odds of having paid work than students who had trouble communicating. McDonall (2011) states that previous research has identified communication skills as a key factor for successful employment. Another study (Verhoef et al., 2014) used a pre-post design to evaluate how participants’ occupational performance changed over time in a multidisciplinary VR intervention, which used job interview training as a component. The study found that students with disabilities who participated in the intervention showed improved occupational performance at work (Verhoef et al., 2014).

Four studies using a qualitative design including interviews (Lindsay & DePape, 2015; Lindsay et al., 2012; Stone et al., 2015) and focus groups (Crudden, 2012) also identified the need for communication and interview skills for successful employment. Stone et al. (2015) interviewed Hispanic and non-Hispanic students with disabilities and found that these students emphasized needing more assistance with job interview skills. Lindsay et al. (2012) interviewed students with disabilities participating in an employment training program that used practice interviews as a component. The majority of participants stated that the practice interviews were a helpful feature of the program (Lindsay et al., 2012). Lindsay and DePape (2015) performed a content analysis of mock interview responses from both students with disabilities and their typically developing peers. The authors (Lindsay & DePape, 2015) found that students with disabilities often faced more challenges during the interview process, such as responding to scenario-based problem-solving questions. Crudden (2012) conducted focus groups with rehabilitation state agency personnel regarding best service delivery practices. Focus group participants recommended that VR personnel conduct a situational assessment of interviewing, communication, and job readiness skills (Crudden, 2012).

4.4.2Social skills support

A total of six studies were identified as addressing the topic of social skills in terms of development, need, or barrier to successful transition programming for students with disabilities (Crudden, 2012; Lindsay et al., 2012; Luft, 2012; McDonnall, 2011; Noel et al., 2017; Verhoef et al., 2014). Interestingly, few of the studies indicated what specific behaviors were associated with social skill development or programming. Inclusion of social skills training for students with disabilities is typically related to work performance and success with co-workers, employers, and customers. The most common reference given was to ‘social skills’, ‘social contact’, or ’social interactions’ but without example, illustration or definition. In some instances, social skills were demonstrated in the context of the interview or career training (Lindsay et al., 2012; Noel et al., 2017), peer activity (Verhoef et al., 2014), or interpersonal interaction (Crudden, 2012; Luft, 2012). Only two of the studies provided a quantifiable result of training for social skill measurement (McDonnall, 2011; Verhoef et al., 2014). A large national observational study (McDonnall, 2011) found that social activities related to peer interactions were significantly related to post-school employment. Similarly, a pre-post single group study (Verhoef et al., 2014) found a positive effect on employment for students with disabilities that understood the nature of social skill use at work, home and in social life.

4.4.3Transportation

Six studies addressed transportation access, competency, or barriers as a significant factor in both school-based and post-school-based employment (Carter et al., 2011; Crudden, 2012; Lindsay et al., 2012; McDonnall, 2011; Noel et al., 2009; Verhoef et al., 2014). Two studies (Carter et al., 2011; McDonnall, 2011) analyzed data from the NLTS2 database. Carter et al. (2011) found that the availability of transportation for people with disabilities was positively associated with employment. McDonnall (2011) reported that difficulty with transportation was a significant predictor of post-school unemployment. Another study (Lindsay et al., 2012) interviewed eighteen students with disabilities that attended a school-based summer program. Participants in the program reported difficulty with transportation to be a substantial barrier to sustained employment and found the transportation skill training to be a valuable part of the program (Lindsay et al., 2012). Another study (Noel et al., 2017) conducted a survey of the Illinois Balancing Incentive Program and reported that 38%of participants in eight of the programs assessed indicated that difficulty with transportation was a major barrier to work. In a pre- post intervention study, Verhoef et al. (2014) concluded that interventions aimed at improving employment for students with disabilities not only should address issues at work, but also problems in self-care such as transportation to work.

5Discussion

This scoping review provided an overview of ex-isting literature that evaluates research-based interventions that can be applied to four of the required pre-employment transition service elements of WIOA. In doing so, it has identified several areas that can help inform strategies used by VR counselors for increasing employment for students with disabilities at the point of transition from secondary school to more divergent paths.

For job exploration counseling, strategies VR counselors may consider 1) working with schools to identify and create goals related to career exploration; 2) reaching out to families to gain new perspectives regarding the student’s career aspirations; 3) learning about the home life and cultural background of students with disabilities to better the situational factors that can affect the job exploration process; and 4) particularly for VR leadership, coming up with ways to identify interagency partners who can help students with disabilities explore career options.

For work-based learning, strategies VR counselors may consider include 1) helping students with disabilities identify internships, volunteer activities, and short-term jobs to prepare for working full-time; 2) weighing the positives and negatives of SSI payments and how these and related benefits affect employment to determine what would be best for the individual; and 3) increasing their awareness of the social supports that exist and develop ways to identify possible role models, mentors, and advocates to enhance their skills at work.

For workforce readiness, strategies VR counselors may consider 1) using communication exercises (for example, mock interviews) to help students with disabilities gain the skills they need for employment; 2) identifying which social skills need improvement and opportunities available to improve them; and 3) helping students with disabilities become familiar with different kinds of transportation.

For instruction in self-advocacy, strategies VR counselors may consider 1) helping plan activities that encourage self-determination; 2) making sure that students have a transition plan in place; and 3) helping students become aware of the accommodations that are available to them in the workplace.

Though these strategies may help VR counselors increase employment outcomes for students with disabilities, there is still the challenge of effectively instructing VR counselors to employ these strategies in the field. Most state VR services likely do not have the resources to design and implement training modules comprised of the strategies discussed in this review. One solution may be to continue to leverage technical assistance centers with expertise on disability and employment to both develop and lead the training. Since the development and implementation of such training modules would require these technical assistance centers to invest both time and resources, policy makers may consider providing additional funding to these centers.

6Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. The quality of each study (i.e., methodology, design) included in this review was not assessed. Determi-nations for inclusion were instead derived by assessing each study’s conclusions, implications, and recommendations as they related to four of the req-uired elements of pre-employment transition services. Another significant limitation concerns how several studies lacked detailed descriptions of the interventions they were evaluating. Though these studies noted that one or more of the components related to themes were utilized in the intervention, they offered little insight as to what degree. Because of this lack of detail, it was difficult at times to determine the emphasis that any one intervention component played in its overall results. Another limitation is that for this review, only articles written in English were used. Articles written on other languages may have been appropriate for this review’s objectives but were not considered. One more limitation is the omission of counseling on opportunities for enrollment in comprehensive transition or postsecondary educational programs from this review. As stated earlier, this WIOA service category did not fit this review’s focus. For a training module focused on the WIOA service categories to be comprehensive, it will also require strategies for this category. A future review may examine the literature regarding strategies for the counseling on opportunities for enrollment in comprehensive transition or postsecondary educational programs WIOA category.

7Conclusion

This scoping review has shown there are several interventions or components within interventions that support employment outcomes for students with disabilities as they relate to the WIOA service categories. To ensure that VR counselors are not only aware of these strategies, but can implement them effectively, technical assistance centers with expertise on disability and employment may consider leading the development of a training module incorporating components of these interventions.

Conflicts of interest

None to report.

Disclaimer

The contents of this article were developed under grant number 90DP0077 from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this newsletter do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the librarian at the American Institutes for Research, Elizabeth Scalia, who conducted the database searches for this review.

Supplementary material

{ label (or @symbol) needed for fn } The Appendix is available from https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JVR-201123.

References

1 | Amendment to the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. P. L. 93–112, title I, §113, as added P. L. 113–128, title IV, §422, July 22, 2014, 128 Stat. 1657. Available from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-113publ128/html/PLAW-113publ128.htm |

2 | Awsumb, J. M , Balcazar, F. E , Alvarado, F. ((2016) ). Vocational rehabilitation transition outcomes of youth with disabilities from a Midwestern state. Rehabilitation Research, Policy, and Education, 30: (1), 48–60. |

3 | Bal, M. I , Sattoe, J. N , Schaardenburgh, N. R , Floothuis, M. C , Roebroeck, M. E , Miedema, H. S. ((2017) ). A vocational rehabilitation intervention for young adults with physical disabilities: Participants perception of beneficial attributes. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43: (1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12407 |

4 | Bouck,E. C., Joshi,G. S. ((2012) ). Functional curriculum and students with mild intellectual disabilities: Exploring postschool outcomes through the NLTS2. Education and Training in Autism & Developmental Disabilities, 47: , 139–153. |

5 | Carter, E. W , Austin, D , Trainor, A. A. ((2011) ). Factors associated with the early work experiences of adolescents with severe disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49: (4), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-49.4.233 |

6 | Crudden, A. ((2012) ). Transition to employment for students with visual impairments: Components for success. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 106: (7), 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X1210600702 |

7 | Dong, S , Fabian, E , Luecking, R. G. ((2016) ). Impacts of school structural factors and student factors on employment outcomes for youth with disabilities in transition. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 59: (4), 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355215595515 |

8 | Fabian,E., Lent.,R.W., & Willis,S. P. ((1998) ). Predicting work transition outcomes for students with disabilities: Implications for counselors. Journal of Counseling and Development: JCD 76: (3). doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1998.tb02547.x |

9 | Fabian, E. S. ((2007) ). Urban youth with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 50: (3), 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/00343552070500030101 |

10 | Foley, K , Dyke, P , Girdler, S , Bourke, J , Leonard, H. ((2012) ). Young adults with intellectual disability transitioning from school to post-school: A literature review framed within the ICF. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34: (20), 1747–1764. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.660603 |

11 | Giesen, J. M , Cavenaugh, B. S. ((2012) ). Transition-age youths with visual impairments in vocational rehabilitation: A new look at competitive outcomes and services. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 106: (8), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X1210600804 |

12 | Greene, G. ((2014) ). Transition of culturally and linguistically diverse youth with disabilities: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 40: (3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-140689 |

13 | Hayward, B. J , Schmidt-Davis, H. (2003). Longitudinal study of the vocational rehabilitation services program. Rehabilitation Services Administration, U.S. Department of Education. |

14 | Hemmeter, J. ((2014) ). Earnings and disability program participation of youth transition demonstration participants after 24 months. Social Security Bulletin, 74: (1), 1–25. |

15 | Interwork Institute. (2016a). Job exploration counseling. San Diego, CA: Interwork Institute. http://www.wintac.org/topic-areas/pre-employment-transition-services/overview/job-exploration-counseling#overlay-context=topic-areas/pre-employment-transition-services/overview/job-exploration-counseling |

16 | Interwork Institute. (2016b). Self advocacy. San Diego, CA: Interwork Institute. http://www.wintac.org/topic-areas/pre-employment-transition-services/overview/instruction-self-advocacy |

17 | Interwork Institute. (2016c). Workplace readiness training to develop social skills and independent living. San Diego, CA: Interwork Institute. http://www.wintac.org/topic-areas/pre-employment-transition-services/overview/workplace-readiness-training |

18 | Izzo, M. V. ((1999) ). The effects of transition services on outcome measures of employment for vocational students with disabilities [dissertation]. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University. |

19 | Jamieson,M., Paterson,J., Krupa,T., & Topping,A. ((1998) ). Determining the effectiveness of thresholds, an intervention to enhance the career development of young people with physical disabilities. Work, 11: , 43–55. |

20 | Lindsay, S , Adams, T , McDougall, C , Sanford, R. ((2012) ). Skill development in an employment-training program for adolescents with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34: (3), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.603015 |

21 | Lindsay, S , DePape, A. ((2015) ). Exploring differences in the content of job interviews between youth with and without a physical disability. Plos One, 10: (3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122084 |

22 | Lindsay, S , McDougall, C , Sanford, R. ((2013) ). Disclosure, accommodations and self-care atwork among adolescents with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35: (26), 2227–2236. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.775356 |

23 | Luecking, D. M , Luecking, R. G. ((2015) ). Translating research into a seamless transition model. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 38: (1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143413508978 |

24 | Luecking, R. G , Wittenburg, D. ((2009) ). Providing supports to youth with disabilities transitioning to adulthood: Case descriptions from the youth transition demonstration. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 30: (3), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-2009-0464 |

25 | Luft, P. ((2012) ). Employment and independent living skills of public school high school deaf students: Analyses of the transition competence battery response patterns. Journal of the American Deafness and Rehabilitation Association (JADARA), 45: (3), 292–313. |

26 | Madaus, J. M. ((2006) ). Improving the transition to career for college students with learning disabilities: Suggestions from graduates. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19: (1), 85–93. |

27 | McDonnall, M. M. ((2011) ). Predictors of employment for youths with visual impairments: Findings from the second national longitudinal transition study. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 105: (8), 453–466. |

28 | McDonnall, M. C , Crudden, A. ((2009) ). Factors affecting the successful employment of transition-age youths with visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 103: (6), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482x0910300603 |

29 | Newman,L., Wagner,M., Cameto,R., and Knokey,A.-M. ((2009) ). The Post-High School Outcomes of Youth With Disabilities up to 4 Years After High School.AReport From the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) (NCSER 2009-3017). Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. |

30 | Newman, L. A , Madaus, J. W , Javitz, H. S. ((2016) ). Effect of transition planning on postsecondary support receipt by students with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 82: (4), 497–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402915615884 |

31 | Newman, L , Wagner, M , Knokey, A.-M , Marder, C , Nagle, K , Shaver, D , Wei, X , Cameto, R , Contreras, E , Ferguson, K , Greene, S , Schwarting, M. ((2011) ). The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school. A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) (NCSER 2011-3005). SRI International. |

32 | NJ Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Services. (2016). Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act pre employment transition services: Implementing VR program requirements. |

33 | Noel, V. A , Oulvey, E , Drake, R. E , Bond, G. R. ((2017) ). Barriers to employment for transition-age youth with developmental and psychiatric disabilities. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44: (3), 354–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0773-y |

34 | Plotner, A. J , Trach, J. S , Oertle, K. M , Fleming, A. R. ((2013) ). Differences in service delivery between transition VR counselors and general VR counselors. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 57: (2), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355213499075 |

35 | Plotner, A. J , Trach, J. S , Strauser, D. R. ((2012) ). Vocational rehabilitation counselors’ identified transition competencies. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 55: (3), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355211427950 |

36 | Povenmire-Kirk, T , Diegelmann, K , Crump, K , Schnorr, C , Test, D , Flowers, C , Aspel, N. ((2015) ). Implementing CIRCLES:Anewmodel for interagency collaboration in transition planning. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 42: (1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-140723 |

37 | Rothman, T , Maldonado, J. M. ((2008) ). Building self-confidence and future career success through a pre-college transition program for individuals with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 28: (2), 73–83. |

38 | Simonsen, M. L , Neubert, D. A. ((2012) ). Transitioning youth with intellectual and other developmental disabilities. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 36: (3), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143412469399 |

39 | Stone, R. A , Delman, J , McKay, C. E , Smith, L. M. ((2015) ). Appealing features of vocational support services for Hispanic and non-Hispanic transition age youth and young adults with serious mental health conditions. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 42: (4), 452–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-014-9402-2 |

40 | Tilson, G , Simonsen, M. ((2013) ). The personnel factor: Exploring the personal attributes of highly successful employment specialists who work with transition-age youth. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 38: (2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-130626 |

41 | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Labor Force Statistics. (2017). College enrollment and work activity of high school graduates news release. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/hsgec.htm |

42 | Verhoef, J. A , Roebroeck, M. E , Schaardenburgh, N. V , Flo-othuis, M. C , Miedema, H. S. ((2014) ). Improved occupational performance of young adults with a physical dis ability after a vocational rehabilitation intervention. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24: (1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-013-9446-9 |

43 | Wehman, P , Sima, A. P , Ketchum, J , West, M. D , Chan, F , Luecking, R. ((2015) ). Predictors of successful transition from school to employment for youth with disabilities. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 25: (2), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9541-6 |

Notes

1 Self-determination is the ability to plan, make decisions, and carry out the activities that one considers to be of personal worth.