Youth and civic participation in Côte d’Ivoire

Abstract

This article analyses civic participation in general and particularly that of young people in Côte d’Ivoire using data from the Governance, Peace and Security survey, conducted within the framework of the Integrated Regional Survey on Employment and the Informal Sector of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) in 2017 The findings confirm the low level of involvement of the population in general, and of young people in particular, in civic activities, both political and social. This can pose serious threats to the peace, democratisation and development process, as the involvement of citizens in political and social activities is the hallmark of a democratic society and ensures social cohesion and development. Institutional variables (presence of corruption, growing insecurity and mistrust) reduce civic participation, including in political and social life. Young people’s involvement in public activities increases in a controlled, less corrupt environment of public safety in which they have greater trust in the state. The living environment (urban and other rural), professional situation (unemployed, inactive) and standard of living of young people (middle class and wealthy) increase their involvement in public activities. Political and social participation influence one another and civic participation is more marked by political participation.

1.Introduction

In the words of Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations and 2001 Nobel Peace Prize winner: “No one is born a good citizen; no nation is born a democracy. Rather, both are processes that continue to evolve over a lifetime. Young people must be included from birth. A society that cuts itself off from its youth severs its lifeline; it is condemned to bleed to death,” thus placing the youth issue at the heart of the development of any country.11 While it is true that young people are increasingly perceived as a positive force for transformative social change, it should be recognised that one of the problems that young people face in general remains that of their civic participation.

Defined as the activity of citizens in public life, taking various forms (political and social), in a wide variety of places (associations, groups, institutions and commissions), at different levels (local, regional and national), civic participation is a factor of sustainable democracy and assures peace and social cohesion.

In Côte d’Ivoire, as is the case in most African countries, young people are considered to be disinterested in politics and the activities of associations or are seen as troublemakers. Indeed, according to the statistics of the Governance, Peace and Security survey carried out by the National Statistical Institute [14], the participation rate of young people (aged 18–34) in the most recent presidential elections in 2015 remains low (33.7%), compared to 66.3% among those over 35 years old, although it is up by 9 percentage points compared to 2010. This figure is 20.3% among young people under the age of 25 and is combined with low participation in associations and political parties (2.3%). Added to this is a lack of interest in religious associations (13% membership), local associations (15%) and family associations (18.6%).

The participation of young people in public, political and social life therefore remains a matter of increasing concern to the authorities. This is especially the case given that young people represent over 70% of the population, according to the general population and housing census [12], are an important driver of growth and are a key workforce for the future management of public and state affairs. Their low level of involvement in current affairs is perceived as a potential risk to democracy, given that, if they are not informed and are insufficiently involved in political and social affairs, they will face real difficulties when it comes to taking positions of responsibility. Furthermore, paying less attention to elections and having a marginal level of participation in the civic process mean that young people are poorly represented in decision-making bodies, which has the consequences of underestimating or even overlooking their points of view.

The literature on citizen engagement models is dominated by several factors, in particular: historical, social, cultural and economic characteristics. Increased attention has been paid to research on civic participation over the past two decades by academics and practitioners in the field of public administration and political science [1, 17, 26, 30]. From the perspective of the search for factors that could explain civic participation, some authors such as [32] or [8] argue that there is no general model that explains electoral participation and, to a greater extent, civic participation, although others have developed models highlighting the importance of certain specific variables [7].

A recent article [18] highlights two types of participation: political and civic, and classifies them into two forms of participation: conventional and unconventional.22 The article also highlights the new ways in which civic participation manifests amongst young people, who express themselves through social media. For these authors, young people are no longer following traditional approaches (whether conventional or unconventional), but are instead following modern approaches to participation via the Internet and are increasingly oriented toward the subjects of “megatrends”33 that are close to their hearts.

By applying this reality to Côte d’Ivoire, it appears that the participation (political and social) of young people still takes traditional forms, not using the Internet. Indeed, Internet access is still poor. According to the enquête sur la mesure de la société de l’information[15], the digital society measurement survey, only 29.7% of people have access to the Internet. Furthermore, when we look at the way in which young people use the Internet, we see that it is used more for telephone calls (56.5%) and for purchases and sales (19.8%), than for publishing opinions on social and political subjects (1.3%) or formulating political or civic orientations (0.9%).

This reinforces our idea of researching the determining factors of civic participation among young people in Côte d’Ivoire, based on conventional approaches not using the Internet, namely participation in elections, political engagement and membership of a political party, as well as social participation. Most studies highlight only one aspect of civic participation, namely participation in the electoral process, while civic participation is a multifaceted concept that takes into account several aspects (political, democratic, civic and social; [22]). Our research has the advantage of modelling the phenomenon of civic participation, by constructing a civic participation index comprising both political participation and social participation. It is based on data from the Governance, Peace and Security (GPS) survey carried out by the INS in Côte d’Ivoire in 2017 and attached to the Integrated Regional Survey on Employment and the Informal Sector of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU).

Civic participation among young people remains a concern for Côte d’Ivoire. Despite the various awareness campaigns directed toward them and the establishment by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) of the platform for the empowerment of youth organisations, it is clear that young people struggle to organise themselves and to influence decision-making, even for decisions that concern them directly. Given the low level of interest among young people in civic actions, it is important to identify the factors that would succeed in bringing about behavioural changes, allowing them to better fulfil their role as engaged and active citizens. With this in mind, what are the determining factors in relation to civic participation among young people in Côte d’Ivoire?

The aim of this article is to analyse the state of civic participation among the populations in Côte d’Ivoire, with a particular focus on the involvement of young people in political and social life. In the rest of this article, after a literature review, we will present the various descriptive statistics and conclude with an econometric analysis.

2.Literature review

The literature on civic participation among young people most often focuses on one aspect of civic participation, in particular participation in elections. This literature reveals two main trends:

1. Those who believe that there is no general model that explains electoral participation [8, 32]

2. Those who believe that there is one and have, therefore, developed models that highlight the effect of certain variables of interest [7, 29]. These variables can be subdivided into two major groups, from individual characteristics to institutional and environmental variables.

In the rest of our review, after defining the concept of civic participation, which is understood in various ways in the literature, we will present the different determining factors of civic participation.

2.1Civic participation: A multifaceted concept

Participation, in the general sense, is a relatively simple concept that puts forward the idea of concrete action. It means taking part in something and is used interchangeably with engagement, involvement, partnership and co-production. As for citizenship, it means that one belongs to a common space, to a political community.

The concepts generally used are those of active citizenship, civic engagement, public participation, civic participation and political participation, which are related concepts, with different and multiple meanings for researchers or for the population. It is embedded in different areas of intervention, including political dialogue, programmes, projects and advisory and analytical services. These interactions allow citizens to participate in decision-making processes with the aim of improving development outcomes.

Some authors highlight the effects of civic participation in their approaches [20]. For them, it is a channel for the exchange of information between the government and citizens. Through civic participation programmes, governments provide information on their activities, whether in terms of new public policies, budget proposals or changes in public services. The supply of relevant information by the government helps citizens to better understand the issues of interest to them (for example, budgetary priorities and their evolution). For [31], citizens are social stakeholders who want to give their time and energy to participate in collective projects, in order to live better in their environment. This approach therefore connects citizens with the skills they need to acquire for better participation in their environment (political, democratic and social).

Active citizenship is a process whereby a citizen integrates into the community, develops their identity and contributes to the development of the community [16]. “Civic engagement” refers to the set of practices through which a person becomes involved and develops links within the community.

Martyn and Dimitra [18] differentiate between participatory and non-participatory engagement. For them, commitments are not always manifested through participatory behaviour. It is quite possible to be interested in political or civic issues, to have knowledge, opinions or feelings about them, without taking action. In other words, individuals may be cognitively or emotionally engaged without being behaviourally engaged.

In this study, our definition of the notion of political and social engagement (civic participation) involves concrete, physical and active actions in the political and social sphere. All studies converge on a two-level definition of the concept of civic participation: political participation and social participation. The definition of the concept that we will use here is based on this approach, highlighting these two aspects. It will be used to build our synthetic index of civic participation.

Generally, the relationship that citizens have with politics is analysed looking at three main dimensions: political participation, understood as engagement in concrete action; politicisation, i.e. discussing politics; and political orientation, i.e. stating one’s opinion or one’s political preferences. In our study, the first dimension of civic participation, perceived in terms of engagement and involvement, was used. Political participation will therefore be analysed in terms of the following three criteria, which have enabled the construction of the political participation index:

• participation in elections;

• membership of a political party or political association;

• political engagement (participation in a strike or petition).

Social participation, for its part, is analysed in terms of participation in various associations (local, religious, professional, family and neighbourhood associations and tontines), as a member or as a leader. These various associations have enabled the construction of the social participation index. As part of this research, we will provide descriptive statistics on social participation, highlighting the status of different people (member versus leader).

2.2The various determining factors of civic participation

The variables that have a determining impact on civic participation can be subdivided into two main groups: individual variables and institutional or environmental variables.

2.2.1Environmental or institutional determining factors

Several variables referred to as institutional determining factors of civic participation or environmental or psychological variables are used in the literature. They focus on population density and agglomeration effects, reading newspapers, school and the example set by parents.

Tavares and Carr [27] stress in particular the positive role that population density can play in respect of electoral participation. Population density is thought to create bonds between citizens and encourage them to come together for participation in the electoral process. For these authors, the higher the population density, the more bonds are created and the more individuals are informed and, therefore, the more they are interested in the process of civic participation. This view does not seem to be shared by [28] in respect of the effect of large cities on voting. This author demonstrates that the larger the size of a municipality, the lower the voter turnout. Her interpretation of this finding is that in a populous municipality, the voters have less of an impression that their vote will make a difference and they are therefore less interested in the electoral process.

The degree of social engagement of young people, such as group membership or membership of a student association, has a very strong impact on their subsequent level of political activity [8]. Howe [11] highlights the lack of political knowledge and political socialisation among young people. He confirms the findings of [6] and [7], according to which school is the ideal place to take action on these factors for two main reasons: it makes it possible to reach almost all young people and it occurs at the most important moment of psychological and social change, adolescence. Experiences during this period of life are thought to influence political behaviour. The institutional context, i.e. the organisation of elections, and/or the institutional environment and the lack of information also have an impact on the process of civic participation. Indeed, in their study on the city of Toronto in relation to elections, Rohner and Collier [25] point out that the particularly high turnout rate in 1997 was the result of a massive electoral campaign. The more informed people are about a process, the more they participate in it. Quality of information can be a determining factor of civic participation.

2.2.2Socio-demographic characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics, or individual variables, include variables such as education, age, income and gender. These variables regularly explain many variations in forms of political participation, such as voting or membership of volunteer organisations [19]. The strongest predictors of political participation are age and education [9]. Nakhaie [21] also demonstrates that age in particular is thought to have a significant impact on voter turnout. For [5], community roots and age are likely to play a determining role. Attitudes are psychological characteristics that could also affect political participation. Such attitudes are ascertained by various qualitative variables, such as political trust [10]; trust in parliament, trust in politicians and satisfaction with democracy [9]; and a sense of civic duty [4].

As their determining factors, studies on voting choice use explanatory variables of political participation and additional variables such as “race” (or ethnic group), characteristics of candidates, retrospective assessments of incumbents’ performance and national economic conditions [10]. These studies analyse voting choices using logit [10] or multinomial logit models, as is the case with studies on the decision to vote, which estimate the propensity to vote [9].

3.The data

In this section, we will present the various data and the descriptive statistics that provide the initial information on the phenomenon of civic participation.

3.1The sampling

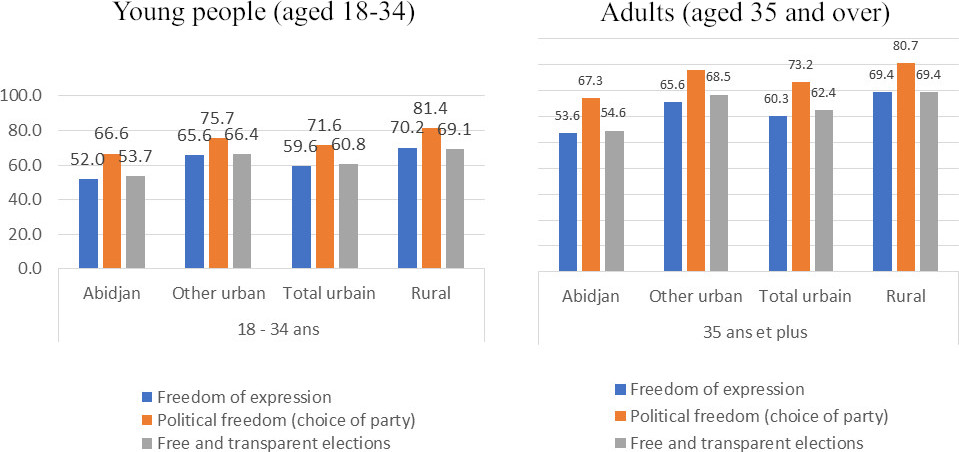

Figure 1.

Percentage of individuals aged 18 to 34 and aged 35 and over who believe that the fundamental principles of democracy are respected, by place of residence, Côte d’Ivoire, 2017. Sources: 2017 ERI-ESI survey, GPS module, NSI; calculations by the author.

The data used in this study come from the Governance, Peace and Security (GPS) survey set up by the African Union Commission, which therefore included it in the Strategy for the Harmonization of Statistics in Africa (SHaSA; [3]). The GPS-SHaSA initiative44 was developed by the African Union Commission, the African Development Bank and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa to produce statistics in the area of governance, peace and security.

The GPS survey in Cote d’Ivoire was linked to the integrated regional survey on employment and the informal sector, conducted by the NSI [13] and funded by the Commission of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU). In addition to collecting information on the labour market and the informal sector, the survey gathered information on perceptions and experiences regarding:

• Democracy and human rights;

• Quality of institutions and corruption;

• Power-citizen relations;

• Crime;

• Peace and security.

An initial sample of 30,811 individuals, representative at national level, as well as of the city of Abidjan, other urban areas and rural areas, was selected. The sample was obtained by two-stage probabilistic sample drawing:

• In the first stage: sample drawing by proportional allocation of enumeration areas (EAs) in the strata of the study;

• In the second stage: systematic sample drawing of 12 households per EA after enumeration thereof.

Within the households surveyed, all individuals aged 18 and over were subsequently identified to respond to the GPS questionnaire. Finally, of the 30,811 individuals aged 18 and older initially targeted, 30,272 were successfully surveyed, which gives a response rate of 98.2%. The sample of this study is therefore a sub-sample of the 2017 ERI-ESI.

3.2The descriptive statistics

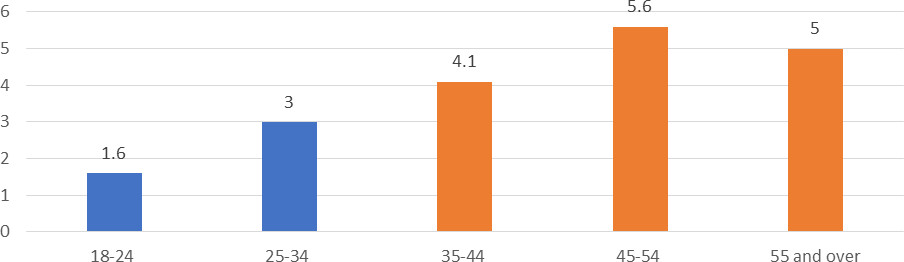

Figure 2.

Percentage of individuals belonging to a political party by age. Sources: 2017 ERI-ESI survey, GPS module, NSI; calculations by the author.

Our sample for descriptive statistics will be subdivided into two groups. A first group concerns individuals aged between 18 and 34 (young people) and the second group concerns those aged 35 and over (adults). In order to build our sample of young people and analyse their participation in citizenship, we used the age of 18 as a basis, since this is the age of majority in Côte d’Ivoire, which is why people aged 18 and over were interviewed in the survey.

3.2.1Perception of democracy

As democracy is a political system, we analyse the democratic participation of young people and adults. Figure 1 shows the assessment of respect for the fundamental values of democracy by age and place of residence. While young people and adults alike have a shared perception of respect for certain fundamental values of democracy, such as freedom of expression (60%), freedom of the press (62%) and equality before the law (56%), regardless of the different areas of residence (Abidjan, with the rest being urban and rural), there is a slight (not always significant) difference in perception between the two age groups regarding free and transparent elections and political freedom. Indeed, 71.6% of young people in urban areas believe that everyone is free to choose to join a political party, compared to 73.2% among those aged over 35. 53.7% of young people think that elections are free and transparent in Abidjan, while 54.6% of the adult population believe this.

3.2.2Political participation

Political engagement in Côte d’Ivoire generally focuses on participation in elections, one of the key aspects of which remains registration on the electoral rolls. However, the relationship to politics, perceived through membership of a political party, participation in political associations and allegiance to a political party are also important in the analysis of political participation.

During the Governance, Peace and Security surveys carried out by the NSI in 2015 and 2017, the populations stated whether or not they had participated in the general presidential elections of 2010 and 2015. In 2010, turnout in the first round of elections was 83.5%, with a score of 66.2% among those aged under 25, 89.6% among those aged 36 to 45 and 94.9% among those aged over 56 [13]. In 2017, just over half of the population aged 18 and over voted (51.8%). This rate is much lower than in 2010 (Table 1). When we look at the distribution of this rate by age group, it is relatively low compared to the rates for the same age group in 2010: 20.3% among those aged under 25, 51% among those aged 25–34 and 62% among those aged 35–44 (NSI, 2015). Also, with data from the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC), the observation of a decline in voter turnout is also confirmed. From 83.7% and 81.1% in the first and second rounds of the 2010 election, this rate was 52.9% in the single round of the 2015 election.

Table 1

Percentage of individuals aged 18 and over who participated in the electoral process and reasons for not voting, by socio-demographic characteristics, Côte d’Ivoire, 2017

| Reasons for not voting | |||||||||

|

| % of individuals aged 18 and over who voted in the most recent elections | No candidates representing your wishes | Voting is pointless | Not regis- tered on the electoral rolls | Other reason | % of people aged 18 and over who are interested in politics | % of individuals aged 18 and over who are members of a political party | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 51.6 | 4.8 | 8.3 | 60.8 | 26.2 | 11.0 | 4.3 | ||

| Female | 52.0 | 4.6 | 8.7 | 64.6 | 22.0 | 5.0 | 2.7 | ||

| Age group | |||||||||

| Aged 18–24 | 20.3 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 74.8 | 18.3 | 5.1 | 1.6 | ||

| Aged 25–34 | 51.0 | 5.1 | 10.3 | 62.4 | 22.2 | 7.8 | 3.0 | ||

| Aged 35–44 | 62.9 | 7.0 | 11.3 | 51.0 | 30.6 | 9.5 | 4.1 | ||

| Aged 45–54 | 72.0 | 8.6 | 12.0 | 45.3 | 34.1 | 9.2 | 5.6 | ||

| Aged 55 and over | 70.9 | 5.3 | 9.6 | 47.6 | 37.6 | 10.3 | 5.0 | ||

| Level of education | |||||||||

| None | 52.2 | 2.8 | 5.8 | 64.1 | 27.3 | 7.1 | 3.1 | ||

| Primary | 55.3 | 6.5 | 9.7 | 62.9 | 20.8 | 8.0 | 4.1 | ||

| Secondary | 51.0 | 7.2 | 12.1 | 59.4 | 21.3 | 9.4 | 3.7 | ||

| Higher | 44.2 | 5.2 | 11.9 | 61.9 | 20.9 | 10.1 | 3.9 | ||

| Côte d’Ivoire | 51.8 | 4.7 | 8.5 | 62.7 | 24.1 | 8.0 | 3.5 | ||

Sources: 2017 ERI-ESI survey, GPS module, NSI; calculations by the author.

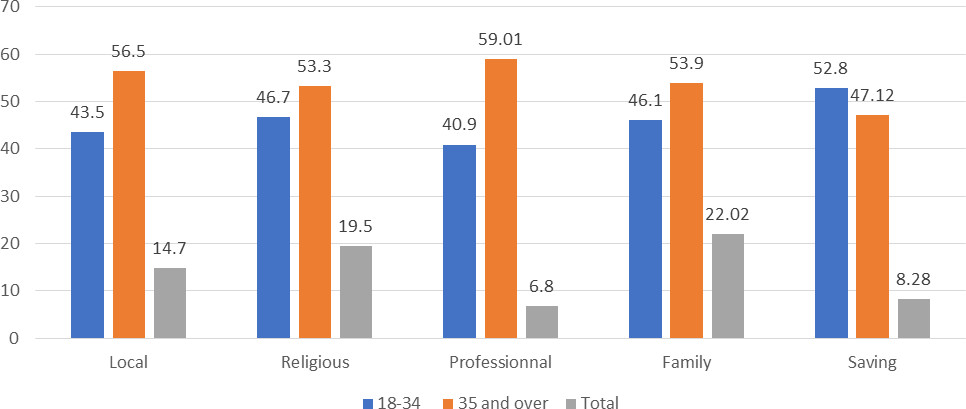

Figure 3.

Membership of an association (%), young people and adults. Sources: 2017 ERI-ESI survey, GPS module, NSI; calculations by the author.

While it is true that the difference in rates (between declarations in the survey and official results) can be explained by several factors, in particular demographic movements (migration and deaths), the exclusion of collective households living in institutions, together with the fact that the declaration by respondents is an a posteriori reconstruction of variable reliability influenced by certain aspects such as who won in the elections, the fact remains that there is a decrease in turnout for the presidential elections. For young people, the reasons for this low level of enthusiasm could be explained by the fact that they are not registered on the electoral rolls. Almost three quarters of young people aged 18 to 24 are not registered (undoubtedly because they were not of voting age). The same is true of 62.4% of young people aged 25–34 and 51.9% of adults aged 35–40.

Added to this is the perception that young people have of voting. For those who did not vote, 4.7% of young people aged 18–24 think voting is pointless. The percentage of those who believe voting is pointless rises to 10.3% and 11.3% for those aged 25–34 and adults aged 35–44, respectively. The rate falls among those aged over 55 (9.6%).

The other element of political participation is membership of or allegiance to a political party. At this level, there is still a low degree of participation in political activities among young people (Fig. 2): 1.6% among those aged 18–24 and 3% among those aged 25–34. These proportions are slightly more than doubled and tripled among those aged 35–44 (4.1%) and those aged over 55 (5%).

As regards their relationship with politics, we see a general feeling of dislike among the population when it comes to political affairs. This phenomenon is more pronounced among young people, with only 8.4% of those aged 18–34 showing an interest in politics. A concrete manifestation of this disinterest is the low proportion, specifically 10.9% and 13.3%, among the two age groups (aged 18–34 and aged over 35) who say they discuss politics in their daily lives.

Another aspect of political participation is the participation of individuals in demonstrations (political demonstrations, strikes and petitions). The survey allows us to see that very few individuals (2.2%) have participated in demonstrations, regardless of their age.

3.2.3Social participation

Social participation is understood through involvement with associations and analysed through the participation of individuals in local neighbourhood associations, religious, professional or family associations or a savings group or tontine.

Of the five types of associations that were identified in the survey, participation in family-type associations is the highest. More than one in five people (22%) are a member of one. Then come religious and local associations, with membership rates of 19.5% and 14.7%, respectively. Savings associations account for 8.3% of the population, with only 6.8% belonging to a professional association (Fig. 3).

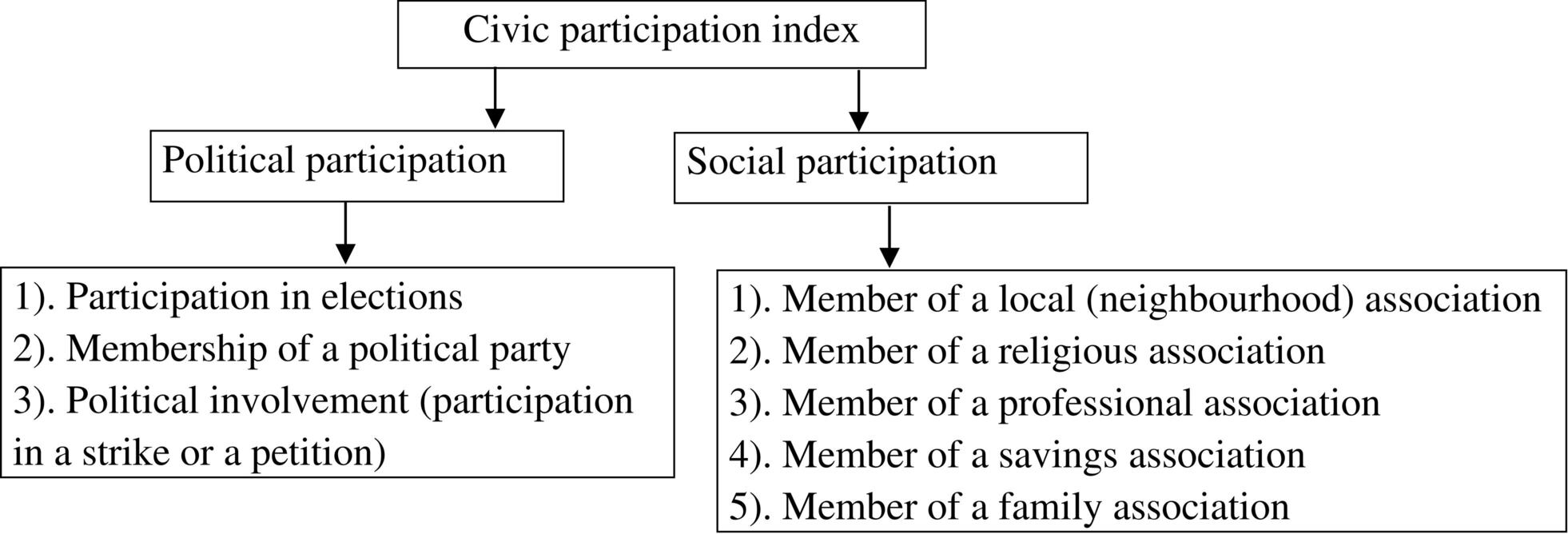

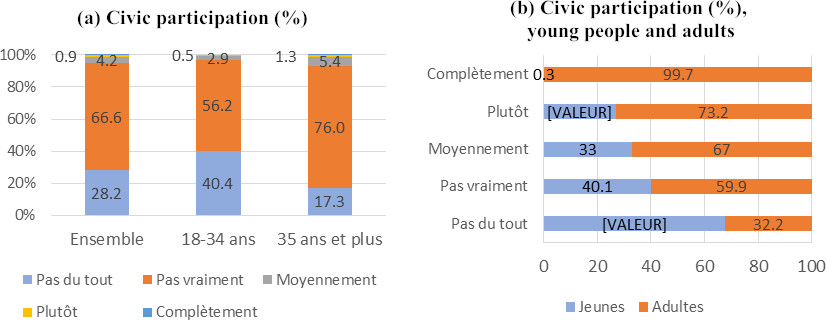

Figure 4.

Construction of the civic participation index.

Figure 5.

Sources: 2017 ERI-ESI survey, GPS module, NSI; calculations by the author.

People may have multiple affiliations. Thus, four in ten people (39.8%) are members of at least one association (less than 3% of whom are leaders). This means that, in contrast, 60% of citizens have no involvement in an association. In general, we find that young people are less involved in associations than their elders, 34.7% of young people and 45.8% of adults are members of at least one association.

3.3The civic participation index

In order to better assess the civic participation of young people, we have constructed a civic participation index. The civic participation index reports on two aspects of this participation: social participation and political participation. Each of these is broken down into sub-indicators, which in turn correspond to the aggregation of several variables. Figure 4 presents the different variables that made it possible to construct the index. The methodological approach used to calculate the civic participation index is inspired by the approach adopted for the calculation of the global governance index [24] and the approach used by [2] to analyse multidimensional poverty. The civic participation index is the simple arithmetic mean of all normalised variables. The final result is expressed on a scale from 0 (the worst result) to 1 (the best possible result). The different values used by the different indices have been grouped together on a Likert scale, using the following terms: “Not at all”, “Not really”, “Moderately”, “Rather” and “Completely”.

The civic participation index was constructed taking the political and social participation indices into account in its definition. In general, the population has a low level of participation in civic activities. Indeed, nearly three in ten people, or 28.2% of the population, do not participate at all in civic activities (Fig. 5a), while 66.6% are not fully involved and only 4.2% are truly active in civic activities.

Among the population that is not involved at all in civic activities, more than two-thirds are young people (67.8%) (Fig. 5b).

4.Econometric model

In this section, we will present the variables and the econometric method used for the estimates.

4.1Explanation of the model

In our study, the civic political and social participation of young people will be analysed using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method. To shine a light on participation among young people, we will carry out three types of regression:

• a general regression on the three types of participation for the population as a whole, distinguishing between young people and adults;

• a second regression with the three types of participation on the sub-population of young people;

• a third regression with the three types of participation on the sub-population of adults.

Aside from these regressions, we also performed two regressions to estimate the interaction between political and social participation. The aim here is to determine whether the two types of participation influence one another and in what sense.

4.2The variables

Table 2

Results of the estimates

| Explanatory | Civ. Part. | Pol. Part. | Soc. Part. | Civ. Part. | Pol. Part. | Soc. Part. | Civ. Part. | Pol. Part. | Soc. Part. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| variables | General regressions | Young people (aged 18–34) | Adults (aged 35 and over) | ||||||

| Age group (ref | |||||||||

| Young person | |||||||||

| Place of residence (ref | |||||||||

| Other urban cities | 3.05E-03 | 4.05E-03 | 1.43E-03 | 1.28E-02 | 1.40E-02 | 1.17E-02 | |||

| Rural area | 1.14E-02 | 9.22E-03 | 9.57E-03 | 1.07E-02 | 4.87E-03 | 1.51E-02 | 1.42E-02 | 1.39E-02 | 1.44E-02 |

| Income level (ref | |||||||||

| Middle class | 5.85E-04 | 2.21E-03 | 3.53E-03 | 3.63E-03 | 2.42E-03 | 1.02E-03 | 5.57E-03 | ||

| Wealthy | 8.53E-03 | 1.20E-03 | 1.32E-02 | 8.24E-03 | 9.87E-03 | 5.82E-03 | 1.24E-02 | 1.14E-03 | 2.15E-02 |

| Level of education (ref | |||||||||

| Primary | 6.85E-03 | 4.79E-03 | 1.02E-02 | 1.04E-02 | 1.33E-03 | ||||

| Secondary | 1.69E-02 | 1.19E-02 | 1.98E-02 | 2.54E-02 | 1.84E-02 | 3.20E-02 | |||

| Higher | 3.35E-02 | 2.47E-02 | 4.46E-02 | 1.95E-03 | 9.02E-02 | 6.30E-02 | 1.30E-01 | ||

| Employment status (ref | |||||||||

| Actively employed | 2.13E-02 | 2.89E-02 | 7.93E-03 | 1.80E-02 | 3.09E-02 | 6.03E-04 | 1.06E-02 | ||

| Unemployed ILO | 1.75E-02 | 4.86E-02 | 3.33E-02 | 2.36E-02 | 4.68E-02 | 1.19E-02 | 4.51E-02 | ||

| Potential workforce | 4.19E-04 | 1.21E-02 | 5.65E-03 | 9.98E-03 | 7.89E-03 | ||||

| Migratory profile (ref | |||||||||

| Internal migration | 1.99E-03 | ||||||||

| International migration | 5.27E-03 | 5.01E-04 | |||||||

| Gender (ref | |||||||||

| Male | 2.31E-02 | 3.52E-02 | 4.34E-03 | 1.94E-02 | 2.72E-02 | 1.22E-02 | 2.91E-02 | 2.72E-02 | 3.29E-02 |

| Marital status (ref | |||||||||

| Married | 2.22E-02 | 9.29E-03 | 3.82E-02 | ||||||

| Single | 7.45E-03 | 1.25E-02 | 6.70E-05 | 2.80E-02 | |||||

| Corruption index | |||||||||

| Crime Index | 3.46E-02 | 3.03E-02 | 7.03E-02 | ||||||

| Trust in the State Index | 3.94E-01 | 3.32E-01 | 3.71E-01 | 2.29E-02 | 2.48E-02 | 5.31E-02 | |||

Sources: 2017 ERI-ESI survey, GPS module, NSI; calculations by the author. Notes:

Our model is composed of two types of variables:

• traditional socio-demographic variables: gender, level of education, place of residence, poverty status, employment status and marital status;

• the variables that frame political and social life: the perception of insecurity, the perception of corruption and trust in the State.

Our variable of interest relating to young people was divided into two as follows: 0

For the explained variables, three variables were used: the civic participation index and the political and social participation sub-indices, the construction of which was explained in the previous section.

4.3Results

The results of our regressions are shown in Table 2. Three estimates were carried out with two different dependent variables. Model 1 performs a regression on the various explanatory variables on the civic participation index. As their dependent variable, models 2 and 3 use political and social participation, on which regression is also performed on the same explanatory variables. The analysis of the results of these regressions confirms that young people participate less, all else being equal, in civic activities, both political and social; this is an initial finding of the article, confirming the hypothesis of low civic participation among young people.

Given that participation by citizens in political and social activities is considered to be the hallmark of a democratic society, ensuring social cohesion and peace, it is important to work to increase the involvement of young people in civic activities. To achieve this, it is necessary to identify the variables on which action should be taken. Our various findings support the hypothesis that civic participation among young people is influenced by the socio-demographic characteristics of the population and by certain characteristics of the economic, security and institutional environment.

With regard to socio-demographic characteristics, living in rural areas (compared to Abidjan) increases the civic participation of young people, both political and social. This is also the case for the oldest people. In contrast, when young people live in urban areas (outside Abidjan), their involvement in civic activities decreases. This finding is due solely to the decline in social participation, since political participation increases. Civic participation, both political and social, increases for adults living either in cities outside Abidjan or in rural areas, compared to those in Abidjan.

Civic participation is higher among men than women. The latter are actually less engaged in activities, despite the numerous awareness-raising campaigns, as well as actions aimed at promoting gender issues, which are now a requirement for development projects and programmes.

As for level of education, the completion of at least primary and secondary level education among young people paradoxically reduces their involvement in civic activities (compared to those who have not attended school), both political and social. It is only when young people attain a higher level of education that they develop a greater interest in civic activities. This finding is different for adults, whose participation tends to increase with level of education (primary, secondary and higher).

Migration (internal or international) is a factor common to the entire population, both young people and adults, that reduces civic participation, whether political or social. However, the model of participation according to level of poverty differs according to age group. There is little involvement by young people from wealthy families in civic activities, while for adults it is quite the opposite. The latter are more likely to participate in the various civic activities (political and social), even if the effects are not linear.

The characteristics of the economic, security and institutional environment also play a significant role in the civic participation of the population. In situations of high corruption or criminality, civic participation, both political and social, declines among young people and adults. For young people, the effects of corruption and crime can spread to other political and social spheres, through election rigging, disinformation, delinquency, kidnappings and crime. This finding may explain their low level of involvement in civic activities when they perceive that the environment is corrupt and that crime is widespread.

Finally, one of the key findings of this research is the role that political participation plays on social participation and vice versa. Indeed, it appears that the two types of participation influence one another positively: the more a person participates politically, the more they become involved socially and vice versa.

5.Conclusion

The objective of this study was to contribute to the enrichment of the literature on civic participation by analysing the determining factors of engagement in public activities among young people in Côte d’Ivoire. First, we proposed a review of the existing literature on this subject at conceptual and operational level. This review allowed us to better define the concept of civic participation, in two dimensions (political and social), that underlies the construction of our civic participation index.

In order to better understand the low level of involvement of young people in civic activities, we opted for three-stage modelling. The first presents the overall state of civic participation across the sample. In a second stage, we performed the same regressions on young people and adults, separately. Our analysis was coupled with a descriptive statistical analysis that allowed us to analyse the civic participation, both political and social, of the two age groups in our sample.

The low level of civic participation among young people, both political and social, hinders the consolidation of democracy, which would provide an assurance of social cohesion in Côte d’Ivoire.

The various findings have highlighted the factors that need to be addressed in order to increase the civic participation of young people. Among these factors, young people take into consideration the security environment in place. Indeed, the more public safety is assured, the more likely young people are to engage in public activities. The same is true when they are in a less corrupt environment. Their engagement in public activities is also associated with their level of education, the standard of living of their parents, their professional situation and their migratory background. The more educated young people are, the higher their parents’ income and the more they are in employment, the more engaged they are at both political and social levels.

In order to examine the effects of civic participation among young people in greater depth, future research could analyse the dynamics of civic participation by comparing the two years that were the subject of GPS surveys (2015 and 2017), more specifically identifying the contribution of the different variables that enabled the construction of the civic participation index.

Notes

1 https://www.coe.int, Council of Europe.

2 Conventional political participation includes voting in elections, campaigning for voting, working for a political party and discussing politics. Unconventional political participation relates to signing petitions, taking part in political demonstrations (meetings) and writing political articles or blogs and sharing them on social media. Social (or civic) participation involves helping people in need, helping to solve problems affecting the community, fundraising for charities, etc.

3 Global warming, pollution, global poverty, the use of cheap labour in the developing world, the greed of multinational companies, human rights (globally) and street art.

4 The GPS-SHaSA initiative, which is part of the Strategy for the Harmonization of Statistics in Africa, aims to develop, test and institutionalise measurement instruments. Intended for the national statistical institutes (NSIs) of the countries of Africa, it is coordinated by the African Union, with institutional and financial support from UNDP and scientific support from the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement – IRD). For the SHaSA, a technical working group was composed of representatives of NSIs from the five African regions, the IRD’s Joint Research Unit for Development, Institutions and Globalisation (unité mixte de recherche Développement Institution et Mondialisation – DIAL) and civil society organisations [23].

References

[1] | Archonte F. Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance, Examining Public Administration. Public Administration. (2006) ; 6: (Special Issue): 66-75. |

[2] | Alkire S, Foster JE. Understandings and Misunderstandings of Multidimensional Poverty Mea-surement. Journal of Economic Inequality. (2015) ; 9: : 289-314. |

[3] | AUC, ECA and AfDB. Strategy for the Harmonization of Statistics in Africa (SHaSA). Addis Ababa: African Union Commission; (2010) . |

[4] | Dalton, Weldon. Partisans and the Institutionalization of the Party System. Party Politics. (2007) ; 13: : 170-179. |

[5] | Dostie-Goulet E, Guay J. Social Networks and the Development of Political Interest. Journal of Youth Studies. (2013) ; 12: (4): 405-421. |

[6] | Dostie-Goulet E, Guay J. Teaching Civic Education in Québec High Schools. Sherbrooke: Sherbrooke University; (2014) . |

[7] | Franklin M. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democra-cies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; (2004) . |

[8] | Geys B. Rational Theories of voter Turnout: a review. Political Studies Review. (2006) ; 4: (1): 16-35. |

[9] | Grondlund K, Setala M. Political trust, satisfaction and voter turnout. Comparative European Politics. (2007) ; 5: (4): 400-422. |

[10] | Hetherington JM. The Effect of Political Trust on the Presidential Vote. The American Political Science Review. (1999) ; 93: (2): 311-326. |

[11] | Howe TR. International Child Welfare: Guidelines for Educators and A Case Study from Cyprus. Journal of Social Work Education. (2010) ; 46: : 425-443. |

[12] | INS. Overall Results of the General Population and Housing Census. Abidjan: National Institute of Statistics; (2014) . |

[13] | NSI. National Report on the State of Peace and Security Governance. Abidjan: National Institute of Statistics; (2014) . |

[14] | NSI. Report of the Integrated Regional Survey on Employment and the Informal Sector, Governance, Peace and Security (GPS). Abidjan: National Institute of Statistics; (2017) . |

[15] | INS. Report of the Survey on the Measurement of the Information Society. Abidjan: National Institute of Statistics; (2019) . |

[16] | Jansen JP, Van Den Bosh F, Volberda HW. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science. (2006) ; 52: (11): 1661-1674. |

[17] | Yang K, Callahan K. Citizen Involvement Efforts and Bureaucratic Responsiveness: Participatory Values, Stakeholder Pressures, and Administrative Practicality. Public Administration Review. (2007) ; 67: (March-April): 249-264. |

[18] | Martyn B, Dimitra P. Youth civic and political engagement. London: Routledge Press; (2019) . |

[19] | Milbrath LW, Goel ML. Political participation: how and why do people get involved in politics. American Review in Political Science. (1978) ; 72: (4): 1482-1484. |

[20] | Nabatchi T. Putting the public back into public values research: designing participation to identify and respond to values. Journal of Public Administration. (2012) ; 72: (5): 699-708. |

[21] | Nakhaie R. Social capital and political participation. Canadian Journal of Political Science. (2008) ; 41: (4): 835-860. |

[22] | O’Neil SK. Political participation after reform: Pensions politics in Latin America. Harvard University; (2006) . |

[23] | Razafindrakoto M, Roubaud F. The Governance, Peace, and Security in a Harmonized Framework for Africa (GPS-SHaSA) modules: development of an innovative statistical survey methodology. Statéco. (2015) ; 109: : 122-158. |

[24] | Renaud F. The Word Governance Index (WGI): Why Should World Governance Be Evaluated, and for What Purpose? Forum for a New Global Governance. Paris; (2009) . |

[25] | Rohner D, Paul C. Democracy, Development, and Conflict. Journal of the European Economic Association. (2008) ; 6: (2-3): 531-540. |

[26] | Scott JK. Municipal Government Web Sites Support Public Involvement? Public Administration Review. (2006) ; 66: (3): 341-353. |

[27] | Tavares AF, Carr JB. So close, yet so far? The effects of city size, density, and growth on local civic participation. Journal of Urban Affairs. (2012) ; 35: (3): 283-302. |

[28] | Trounstine J. All politics is local: the re-emergence of the study of city politics. Perspectives on Politics. (2009) ; 7: (3): 611-618. |

[29] | Riker WH, Ordeshook PC. A theory of the calculation of voting. American Political Science. (1968) ; 62: (March): 25-42. |

[30] | Royo S, Yetano A, Acerete B. E-participation and environmental protection: are local governments really engaged?. International Journal of Public Administration. (2013) ; 74: (1): 12-20. |

[31] | Souad SB, Rafika K. Citizen Participation: A Matter of Competency. European Journal of Social Sciences. (2022) ; 5: : 2:24-38. |

[32] | Van Ham C, Smets K. The embarrassment of riches? A meta-analysis of individual-level research on voter turnout. In: ELECDEM Closing Conference. European University Institute; June 28–30 (2012) . |