Governments measure during the COVID crisis and statistical implications in national accounts: The case of tax deferrals1

Abstract

During the COVID-19 crisis many European governments have implemented major policy measures to support companies and households coping with the sharp decline in economic activity. Correctly interpreting and recording these measures in the national accounts was a major challenge for compilers who had to ensure not only timely but also independent, reliable, and comparable statistics in exceptional circumstances. High quality official statistics are fundamental for public finance monitoring, both at quarterly and at annual level. They provide informative basis for policy makers and economic analysts and play a central role in the context of the European fiscal surveillance process. This paper discusses how the Italian Statistical institute (ISTAT) managed to quickly respond to the sudden increase in the need for public finance information in the aftermath of government interventions to contrast the consequences of COVID-19 crisis. In particular, the paper focuses on one of the first fiscal actions Italian government enforced immediately following the outbreak that is deferrals of tax obligations. According to OECD (2021) this is the main fiscal relief European countries have introduced in response to Covid crisis. The urgency of giving appropriate trace of these actions in the framework of national accounts has raised a significant methodological issue for compilers, and its solution can be exemplary of an innovative approach to provide data during extraordinary periods remaining as compliant as possible with the conventional processes and codified rules. The approach is based on the combination of new data sources with already existing data, on a strengthen interaction among data providers and government agencies to assure a speedier access to administrative data (Ministry of Finance and Revenue Agency), and on a strict collaboration with European institutions (Eurostat).

1.Introduction

During the COVID-19 crisis European governments have implemented unprecedented policy measures to help companies and households against the economic effects brought about by the pandemic and to support the economic activity rebound as quickly as possible [1, 2]. Reliable fiscal data are crucial to evaluate the impact on public finance of these massive policy packages. In this respect, national accounts, and government finance statistics (GFS) in particular, took an important role in providing not only timely data as the crisis progressed, but also reliable information for the assessment of the fiscal effort put in place by governments and thus their fiscal stance [3]. In fact, GFS are underlying the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) that form the basis of the European fiscal monitoring. Therefore, correctly interpreting and recording Covid policy interventions in the framework of national accounts was a major challenge for compilers, also for the amount of public resources involved and the novelty of many of the actions taken by governments.

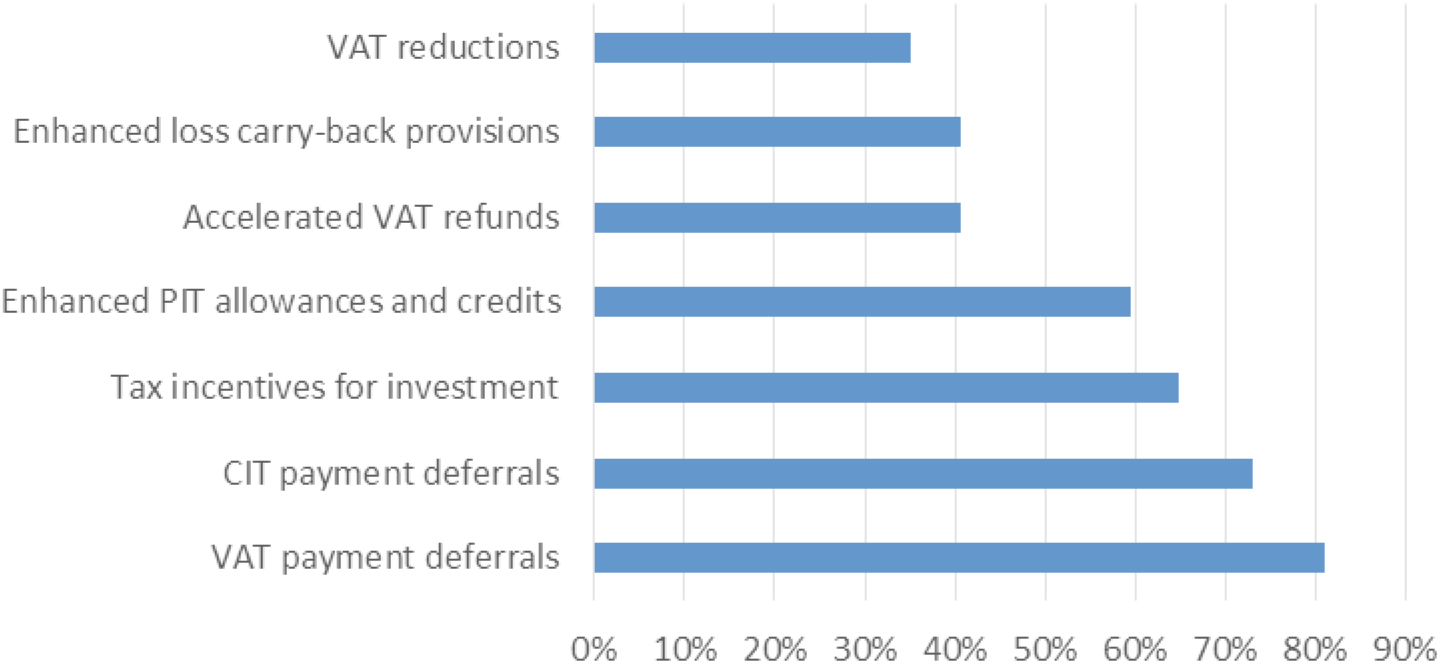

Figure 1.

Most common tax measures in OECD countries, % shares of countries reporting tax measures. Source: OECD (2021).

This paper focuses on deferrals of tax obligations, one of the first fiscal actions European countries enforced immediately following the outbreak. We discuss how the Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), that is responsible in Italy for the compilation of GFS/EDP data, addressed the methodological, data sources and estimation issues related to the recording of postponement of payment deadlines in the national accounts.

The paper is structured as follows. We very briefly describe tax deferrals during the COVID-19 in paragraph 2. The treatment of tax deferrals in general government account is presented in paragraphs 3 and 4. Finally, paragraph 5 concludes.

2.Tax deferrals during the pandemic

Tax deferrals are one of the most common measures adopted in Europe as a first response at the pandemic crisis in early 2020 and they allow companies to shift payments of tax obligations to when normal activity resumes [4, 5]. The measure is intended to support companies significantly impacted by a loss of income due to COVID-19, but also to prevent possible ripple effects throughout the economy resulting from companies’ difficulties to pay for wages, intermediate consumptions, and interests on debt. It was only later after the outbreak that more comprehensive fiscal strategies were introduced to promote recovery (such as tax incentives for investment).

According to OECD, in 2020 more than 80% of OECD countries have taken measures to defer tax payments for corporations, while a smaller share has removed tax obligations [6, 7, 8]. Beyond country specificity, tax postponements show similarities, such as being limited to specific sectors and/or areas (generally where the decline in turnover was most severe), being granted without the payment of either interest or penalties and the deferral of VAT payments playing a key role. In some cases, tax deferrals continued beyond the restricted period of business suspension.

In Italy deferrals and suspension of several taxes and social contributions was one of the first action taken in the aftermath of the pandemic outbreak. Deadlines were postponed and sometimes tax obligations were waived; collection procedures and payment demand were also deferred, like inspection notices and payments due for various procedures to correct tax positions. The legal framework was gradually defined as the economic context worsened, from the first selective interventions in March 2020, limited in time (March-June) and in areas/sectors covered, to the most recent ones directed to larger beneficiaries. Details on deferrals, by type of tax are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1

Tax deferrals in Italy in 2020

| Type of tax | Deferral | New deadlines |

|---|---|---|

| Withholding taxes for employees | Monthly payments (March–May 2020) | Two options:

|

| Monthly payments (Nov–Dec. 2020) | 30th April 2021 | |

| Withholding taxes for self-employed | Monthly payments (March–May 2020) | Two options:

|

| Monthly payments (Nov–Dec. 2020) | 30th April 2021 | |

| Personal income tax | 2020 tax advance (Nov.–Dec. 2020) | 30th April 2021 |

| Company tax | 2020 tax advance (Nov.–Dec. 2020) | 30th April 2021 |

| IRAP | 2020 tax advance (Nov.–Dec. 2020) | 30th April 2021 |

| VAT | Monthly and quarterly payments (March–May 2020) | Two options:

|

| Monthly and quarterly payments (Nov.–Dec. 2020) and December 2020 monthly advance (Dec 2020) | 30th April 2021 | |

| Regional and Municipal income tax-surcharge | ||

| Tax on lotto, lotteries and betting | Payment due in December 2020 |

Source: Authors’ elaborations based on national legislation.

In general, for those taxpayers that opted for the deferral of payments of major taxes (personal income tax and VAT) two payment options were set:

1. 100% by September 2020, in a single payment or in 4 instalments (with last payment in December 2020);

2. the total amount due payable in two parts:

– 50% by the 16th of September 2020, in a single payment or in 4 instalments (with last payment in December 2020);

– the remaining 50% by the 16th of January 2021, in a single payment or in instalments, with a maximum of 24 instalments allowed (and with the first one to be paid starting from the 16th of January 2021).

In addition, for selected companies, payments of tax advance related to personal income tax, company tax and Irap due in November and December 2020 are postponed to April 2021. In both cases, no interests, or penalties for delays in payment are due by the taxpayers.

3.The treatment of tax deferrals in the general government account

Principle and recording rules for national accounts are defined by the European System of Accounts (ESA 2010) and by the Manual on government deficit and debt (MGDD) [9, 10]. However, in case of tax deferrals, no precise accounting guidance is currently included in the European regulation. In the context of the MGDD, only a few broad recommendations are given with respect to changes in due date for payments of taxes, but always within the year. In the aftermath of the first actions undertaken by governments to deal with the economic effects of the pandemic, the need for further guidance in respect of more complex transactions or of cases not fully covered by the current system of rules emerged. Since March 2020 Eurostat issued draft guidelines for member states to achieve harmonised recording of similar policy measures across Europe, including the postponement of tax obligations [11]. Alongside ISTAT begun a constant exchange with the EU institution to converge on a common approach on several issues, tax deferrals in general government account included. In 2020 and 2021, this issue was discussed in different settings and in different forms: both in the occasional exchanges with the EDP and the GFS representatives and in the Task Forces and Working Groups (GFS TF, EDP WG). In January 2021, the issue was also dealt with during the EDP visit that Eurostat made to ISTAT.

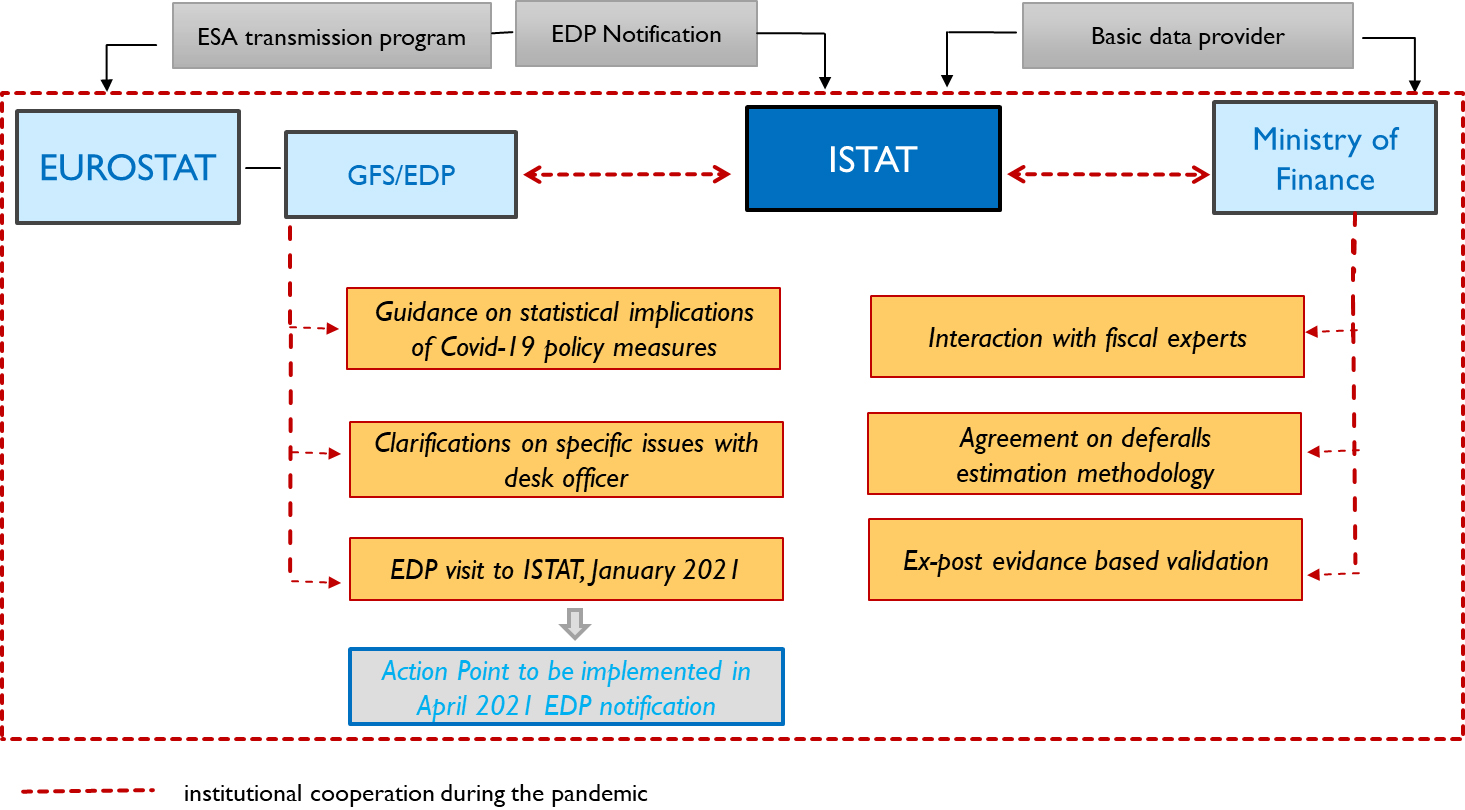

Once agreed on the most appropriate approach, it was then necessary to adjust/amend the estimation methodology of taxes to the new regulatory framework. This involved ISTAT collaboration with the Department of Finance (the main tax data provider) and the integration of the basic data normally used in tax estimation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Institutional interaction and actions during the pandemic.

3.1The recording of tax in general government account: the case of tax deferrals

ESA 2010 recommends that taxes are recorded according to the accrual principle, that implies in the same reference period as the taxable event (“Taxes (…) are recorded when the activities, transactions or other events occur which create the liabilities to pay taxes”, ESA 2010 §4.26 e §4.82). On the contrary, cash-based reporting is the least preferred approach as it records taxes in the reference period when cash is received or paid. At the same time, MGDD sets out that only taxes whose certainty of collection is guaranteed should be included as revenues in General Government account (“Unpaid taxes and social contributions must imperatively not be recorded as government revenue and, as a matter of principle; in the long run there must be full convergence between accrued and paid amounts”, MGDD §2.2.1.1). According to ESA2010, two alternative methods of estimate can be applied, depending on data source availability. In case assessments and declarations are used the amounts shall be adjusted by a coefficient reflecting assessed and declared amounts never collected (AD method). In case of cash receipts as basic data, they shall be time adjusted so that the cash is assigned when the activity took place to generate the tax liability (TAC method). This adjustment is based on the average time difference between the activity and cash tax receipt (ESA §4.27). In summary, the accrual time of recording and the certainty of revenues collection are the two key principles underlying the estimation of taxes in the framework of national account.

Italy mostly applies a TAC method with a maximum of two months adjustment, also considering the timeline of fiscal data reporting within the EDP Notification.22 The time lag adjustment includes payments made in January and, in some cases, in February of year T

As explained, the Covid legislation set the postponement of tax payments due in 2020 to 2021 and 2022. In order to still guarantee accrual estimation and to avoid an improper general government deficit impact due to a double-count of taxes in one period and no recording in another period, the two months TAC methodology has been amended,44 assigning the cash payments spread over 24 instalments to the year 2020 where they accrued. The drawback is that with this approach it is necessary to estimate the future amounts collected with the risk of backward revisions when updated information will be available. The implementation of the described theoretical approach presents difficulties related to incomplete or unavailable information.

3.2The estimation of tax deferrals to be imputed on accrual

The treatment of tax deferrals, as described above, implies the estimation of the unknown amount payable by taxpayers in the future, to be imputed in national account in 2020, according to the accrual principle. Moreover, the estimate has to include also a calculation of the taxes not expected to be eventually collected because of the effect of the crisis and thus to include the difficulties the tax payers faced to be compliant with tax obligations. Therefore, an abatement coefficient has to be applied.

In order to provide reliable estimation of expected revenues (to be recorded as 2020 accrued data), the methodology was developed in collaboration with the Fiscal Department of the Ministry of Finance that provided additional information compared to the routine basic data provision. In particular, the first step focused on the first set of deferrals (March–May 2020), whose payments were due to start already in September 2020. The first evidence of actual payments in September 2020–December 2020 have been used as the basis of the remaining part of deferrals payable in 2021 and 2022. The methodology is based on micro data (by fiscal codes), thus allowing the comparison between the amount of payments made in “ordinary” periods with those made in the months affected by deferrals and in the months in which repayments were due. This ensures a more robust estimate of deferred payments than aggregate data. By matching the payments made by individual fiscal codes both in September (when one-time payment was allowed) and in October and November (when repayment in instalments was expected), it was also possible to identify taxpayers who opted for one time payments and those who chose to pay in instalments.

Many problematic issues have been affronted when considering the tax accrual estimate for the year 2020:

• taxpayers do not have to submit additional communication to the Revenue Agency neither concerning the choice to postpone tax payments nor concerning the number of instalments eventually used. Only for VAT a specific code (“codice tributo”) for the payment of deferred amounts was introduced;

• the actual amount of the taxes collected will be known only when all the instalments will be paid and also the possible use of tax declarations as an alternative data source is affected by the fact that they will be available with 2 years delay (2020 tax declaration available only after late 2023);

• the high degree of uncertainty over the ability of taxpayers to settle their liabilities in the future require distinguishing the “deferral” effect from the “crisis” effect on tax receipts.

The same methodological approach based on microdata was used to estimate deferrals involving November and December 2020 payments.

As for uncollectible amounts (payment unlikely to be collected by the tax Authority), a prudential approach was applied by considering the average probability of default of Italian non-financial corporations as reported in official outlooks.

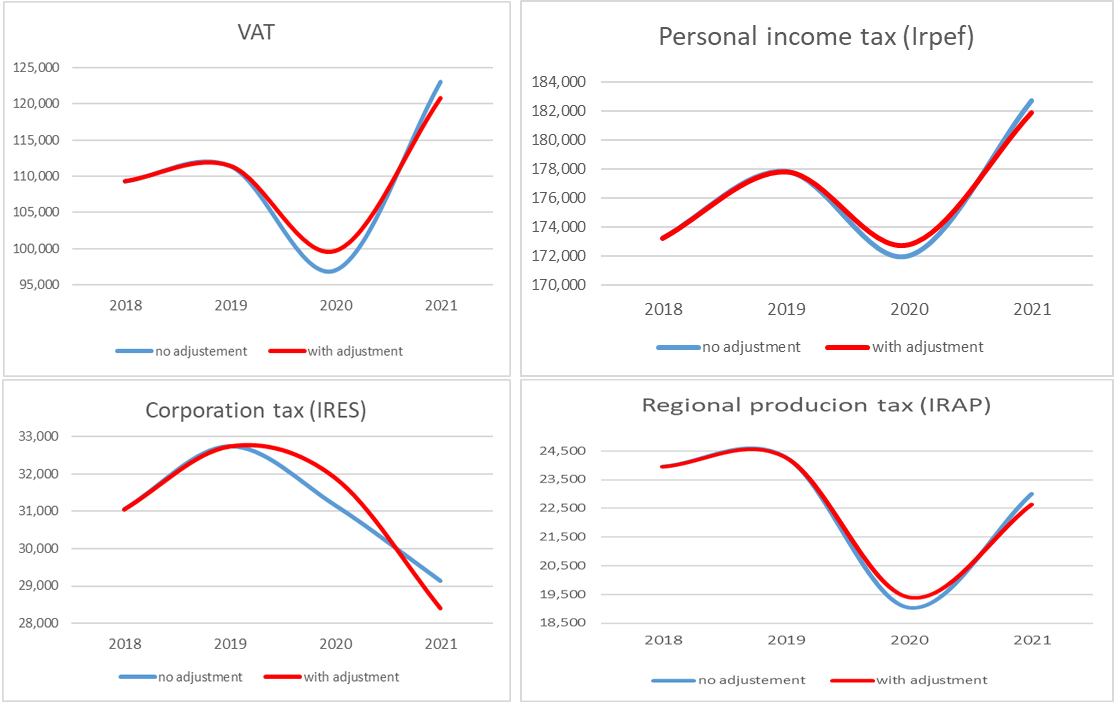

Figure 3.

Taxes in general government account, series adjusted with deferrals (2008–2021, mln of euro). Source: ISTAT, our elaboration on national accounts data.

4.The 2020 accrual estimation of taxes: Some results

The main taxes affected by the deferral’s legislation, namely, VAT, personal income tax and corporation tax are shown in Fig. 2 for the years 2019–2021. Series adjusted with the deferrals in 2020 and 2021, as reported in the latest release of the account, are compared with those unadjusted. The adjusted series are those relevant for the impact on general government accounts.

First 2020 release in April 202155 was revised after six months in the October 2021, mainly for the changes of deferrals to be imputed. The new estimate provided by the Department of Finance was based on an ex-post analysis of evidence emerged since August 2021. When considering revision (Table 2), we find that the preliminary figures are good predictors of the final figures for VAT: the ratio of deferrals to taxes and the rate of change in respect to the previous year remain almost unchanged in all three releases of accounts. On the other hand, for personal income tax, corporation tax and regional production tax analysed indicators stabilise since the second release.

Table 2

Tax deferrals revisions by type of tax (%)

| Deferrals imputed/tax (%), year 2020 | |||

| I release (*) | II release (**) | III release (***) | |

| VAT | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Personal income tax | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Corporation tax | 4.5 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Regional producion tax | 5.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Rate of change, 2020/2019 (%) | |||

| I release (*) | II release (**) | III release (***) | |

| VAT | |||

| Personal income tax | |||

| Corporation tax | |||

| Regional producion tax | |||

(*)Apr. 2021. (**)Sep. 2021. (***)Apr. 2022. Source: ISTAT, our elaboration on national accounts data.

5.Conclusion

The tax deferral was one of the first actions adopted by the Italian government to react to the economic consequences of the pandemic crisis, set by the law as one-off and with a unique application in the crisis period. The recording in national account was a major challenge for ISTAT. It was necessary to respond to the needs for reliable official statistics with a prompt adaptation of the methodological framework, of the estimation approach and of the reference basic data. It was shown how collaboration between the institutions involved fosters the convergence process to ensure comparable and consistent data.

Notes

2 Details are reported in the EDP Inventory for Italy.

3 Revenues collected through roll procedures, tax instalments and late payments incurring after February T

4 Tax deferrals have been set by the law as one-off and with a unique application in the crisis period. In this respect, the MGDD clarifies that when a change is expected to be temporary and would affect the cash amounts received by government, it should not be taken into account under an accrual recording (MGDD 2.3.2.3.12).

5 ISTAT publishes annual general government accounts in fixed cycle, twice a year, alined with the timeline of the EDP notifification (in April and September).

References

[1] | Anderson J, Bergamini E, Brekelmans S, Cameron A, Darvas Z, Domínguez Jíménez M, Midões, The fiscal response to the economic fallout from the coronavirus. Bruegel Datasets; (2020) . |

[2] | IMF, Fiscal Monitor Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic IMF Fiscal Affairs Department; October (2021) . |

[3] | Biancotti C, Rosolia A, Veronese G, Kirchner R, Mouriaux F, Covid-19 and official statistics: a wakeup call?, Questioni di Economia e Finanza, banca d’Italia, February; (2021) . https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/qef/2021-0605/QEF_605_21.pdf. |

[4] | ECB, The initial fiscal policy responses of euro area countries to the COVID-19 crisis, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 1/2021; (2021) . |

[5] | OECD, “Most common tax measures in selected regions: Shares of countries reporting tax measures in each group”, in Tax Policy Reforms 2021: Special Edition on Tax Policy during the COVID-19 Pandemic, OECD Publishing, Paris; (2021) . doi: 10.1787/8199e49b-en. |

[6] | OECD, Tax Policy Reforms 2021: Special Edition on Tax Policy during the COVID-19 Pandemic (report); published 21 April 2021. |

[7] | Eurofound, COVID-19: Policy responses across Europe, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg; (2020) . |

[8] | European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the Council. One year since the outbreak of COVID-19: fiscal policy response; 3 March 2021. |

[9] | REGULATION (EU) No 549/2013 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2013 on the European system of national and regional accounts in the European Union; (2013) . |

[10] | Eurostat, Manual on Government Deficit and Debt. Implementation of ESA 2010. 2019 Edition. |

[11] | EUROSTAT (2020), Draft note on statistical implications of some policy measures in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic; April (2020) . https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/1015035/2041357/Draft+note+on+statistical+implications+of+some+policy+measures+in+the+context+of+the+COVID-19+measures+-+09+April+2020/efc6d52f-39e0-fd92-c760-f27d90676ef0. |