New needs and training modalities for the sustainable transfer of know-how on food and agriculture statistics in the COVID-19 era1

Abstract

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Global Indicator Framework (GIF) has multiplied training needs due to the large number of new indicators to be monitored by countries, whereas COVID-19-related social distancing restrictions have provided an unexpected springboard for the proliferation of cutting-edge virtual training tools and modalities. This has exposed a panoply of new data-related skills needed by contemporary statisticians, and therefore the types of training that could be most appropriate for acquiring these skills. This paper analyses the changing context and nature of training, with particular reference to the experience of FAO as a custodian agency for a large share of SDG indicators. The combination of different learning modalities, appropriately blended into a coherent learning programme, is shown to have the greatest impact, with one modality reinforcing the strengths and dampening the limitations of another.

1.Introduction

The nature of statistical training is rapidly changing. The endorsement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Global Indicator Framework (GIF) in 2017 by the UN General Assembly multiplied training needs due to the large number of new indicators to be monitored by countries, whereas COVID-19-related social distancing restrictions have provided an unexpected springboard for the proliferation of cutting-edge virtual training tools and modalities.

This paper analyses the changing context and nature of training, with particular reference to the experience of FAO as a custodian agency for a large share of SDG indicators. Section I will situate training within the broader capacity development model of international organizations, outlining FAO’s new approach to capacity development; the useful but increasingly blurred dichotomy between training and technical assistance; the key principles underpinning FAO capacity development strategy; and recent collaborations with training institutions on official statistics. Section II will trace the new training needs arising from the SDGs and COVID-19, and identify new data-related skills that deserve to be promoted with targeted training. Section III presents an analysis of training needs related to the SDG indicators under FAO custodianship, based on FAO’s 2019 Statistical Capacity Assessment addressed to SDG focal points in National Statistical Offices. The section will also provide some reflections on the need to better coordinate capacity assessments among international agencies. Section IV will delve into innovative learning solutions and delivery models, with particular reference to the combination of various training modes and tools; the need to appropriately plan training in order to maximize the effective use of new know-how; the complementary impact of training assessments and certification as a way to strengthen knowledge transfer, as well as the value of targeting training to different users of statistics, besides producers. The section will also offer a closer look into the profile of users of FAO e-learning courses and draw key lessons from FAO’s experience with this training modality. A final concluding section will summarize the key takeaways and consider some broader implications for the future of training.

2.Training as a component of the FAO capacity development strategy

2.1FAO new approach to capacity development

Since its foundation, FAO has been supporting Member Countries in strengthening their agricultural statistical systems and improving the skills of official statisticians, with capacity development having always been at the core of its interventions worldwide. Over time, FAO has enhanced its capacity development strategy to reach a more sustainable impact, implement the most advanced and up-to-date practices in the international development community and adapt to the changing needs of countries. FAO’s 2010 capacity development strategy[1] is underpinned by a series of principles inspired by the international debate on aid effectiveness, which is grounded in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the Accra Agenda for Action[2].

To make its capacity development approach more effective and sustainable, FAO has gradually shifted its focus from being the direct provider of “ad-hoc” training interventions to organizing programmes for transferring technical skills and know-how, playing a facilitating role, enabling coordination and collaboration, connecting actors and stakeholders, supporting national processes, and also targeting functional competencies, all to achieve longer-term impacts. Functional competencies include capacities relevant to individual and organizational effectiveness, such as leadership, advocacy and strategic planning, which are crucial for national decision makers and local actors to make the transformations needed towards longer term and sustainable outcomes. Functional competencies are a necessary complement to technical capacities, as they empower national actors such as Heads of National Statistics Offices (or other staff with managerial oversight) to effectively apply the new knowledge/skills and maximize the overall impact of the interventions. In this way, FAO’s new approach to capacity development aims to strike a better balance between technical and functional competencies, as both are crucial for ensuring that countries’capacities are enhanced in a sustainable way.

2.2Integration of training and technical assistance

Training has been and will undoubtedly continue to be a fundamental pillar of a well-rounded capacity development programme in any organization. Nonetheless, despite improving and evolving over time, training still needs to be integrated with other types of capacity development in order to produce maximum impact. For instance, a common distinction is that between training and technical assistance. Whereas training is critical for imparting basic knowledge, getting participants to a basic level of understanding and forging common objectives and a common language, technical assistance tackles specific issues with a problem-solving approach, offering an opportunity to put theoretical knowledge into practice, test solutions and verify whether they are appropriate for the problem at hand.

The distinction between training and technical assistance is sometimes mistakenly understood to mean that the two approaches offer alternative pathways, when in fact they are complementary and mutually reinforcing. For example, training is often a prerequisite for implementing more hands-on activities, and therefore technical assistance is of little value unless recipients have already been armed with a basic understanding of the problem area. Conversely, the directness, flexibility and ability to cater for highly customized requirements, allows technical assistance to build on previous trainings by putting theory into practice, while overcoming some of the common limitations of training, such as the fact that it does not always convene the right people and at the right moment. Therefore, training and technical assistance are complementary.

2.3Principles of the new FAO capacity development strategy

FAO capacity development interventions are now guided by the following principles[3]:

1) country-driven: provided only at the country’s request and designed collaboratively to ensure country ownership and leadership, for longer-term outcomes.

2) aligned and integrated within national priorities, to concretely support ongoing national processes and increase the likelihood of their success.

3) aligned with global frameworks (such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development) to ensure that country interventions are harmonized across countries, and synergetic in producing better development outcomes at regional and global levels.

4) based on national systems and local expertise: to capitalize on existing local capacities and assets and be fully coordinated with local and development actors in order to ensure effective harmonization, coordination, collaboration and inclusive partnerships for a greater impact.

5) built on mutual accountability of the actors involved: to monitor the quality of the training provided by FAO, as well as the impact on the skills of official statisticians.

6) systematic and integrated with technical assistance into broad, coherent and systematic programmes of capacity development (e.g. learning trails) targeting the implementation of strategic agricultural statistics plans (SPARS) and specific skill gaps of official statisticians.

7) designed using a combination of different delivery modalities (technical webinars, coaching, experience sharing, self-paced e-learning, mobile responsive programmes, online tutored courses).

8) integrating hands-on activities, based on relevant local/national case studies and practical examples.

9) informed by well-defined quality criteria (as established in the FAO Statistical Quality Assurance Framework) addressing processes, outputs and institutional setting associated with statistical data collection, analysis, interpretation and monitoring. The adoption of this quality assurance framework enables coordination and harmonization of national statistical systems and ensures a coherent and holistic approach for statistical quality management, thus ensuring trust and quality of official statistics.

10) providing a formal certification of the acquisition of new competences: the knowledge and skill acquired through the participation of national experts in training events is now based on the assessment of their performance and on a formal certification of the actual acquisition of new competences, that match their professional profile and enable them to support national processes, towards sustainability. As certification may provide a boost to career progression, this provides a further incentive for learners to complete a given training course.

All these general principles apply equally to statistical capacity development and to statistical training, in particular. For instance, statistical trainings no longer focus preponderantly on technical competencies, but also on functional competencies that are useful for both technical staff, managerial staff and policy-makers, such as leadership, interpersonal communication, professional development, quality management and similar competencies.

2.4Collaboration with training institutions on official statistics

Building partnerships and collaboration with training institutions and academic programmes is fundamental for broadening training in food and agriculture statistics. To this end, FAO actively collaborates with Regional Statistical Training Institutes, participates in the Global Network of Institutions for Statistical Training (GIST), and facilitates the mainstreaming of food and agricultural statistical training in academic programmes as demonstrated in the two concrete examples below.

2.4.1Collaboration of the FAO “Global Strategy to Improve Agricultural and Rural Statistics” with a post-graduate programme

As mentioned above, training is an integral part of a holistic capacity development strategy. One of the largest capacity development programmes implemented to date in the area of food, agricultural and rural statistics – the “Global Strategy to Improve Agricultural and Rural Statistics” (GSARS) – provides a good example of how to approach training in this perspective. The Global Strategy delineated a comprehensive training action plan [4] at the global and regional levels, taking into account training already provided by academic institutions (building on existing training programmes), country statistical capacity assessments and national strategies for the development of statistics.

The Global Strategy training plan was guided by a two-fold objective. On one side, the training activities aimed to upgrade the skills of targeted technical officers on the latest cost-effective methods pertaining to food, agriculture and rural statistics. Such initial training was then followed by more hands-on technical assistance projects to consolidate the newly acquired skills and catalyze the uptake of the new methods in the national data production cycle. The Global Strategy Evaluation[5]concluded that training followed by technical assistance on priority methodologies (e.g. Computer-assisted personal interviewing, Master Sampling Frame, Agriculture Cost of Production and Food Balance Sheets) has been critical for the uptake of cost-effective statistical methodologies in developing countries. A total of 960 participants from 82 countries (53 in Africa and 29 in the Asia-Pacific region) benefitted from training/workshops, which led to 99 Technical Assistance initiatives carried out in 44 countries (28 in Africa and 16 in Asia-Pacific) during a period of about five years.

At another level, the training strategy also aimed to address the structural capacity gaps in the institutions in charge of agricultural and rural statistics, such as the Ministry of Agriculture. Indeed, in several countries, the personnel in charge of statistics were found to have little or no formal statistical training, therefore impairing the capacity of their institutions to produce good quality and methodologically sound statistics. To cover this gap, the Global Strategy worked with regional statistical training institutions to develop a university curriculum in agriculture and rural statistics and implement a scholarship programme to sponsor the academic training of national staff. Scholarships were provided to 79 African agricultural data specialists from 40 countries to allow them to complete the studies leading to a Masters in Agricultural Statistics in one of the following African Statistical Training Centers: ENSEA-Abidjan, ENSAE-Dakar, EASTC Dar-Es-Salaam and ISSEA-Yaoundé.

The first phase of the Global Strategy was finalized before the COVID-19 outbreak, whereas the second phase is about to begin. In the midst of the pandemic, the “new normal” in terms of training modalities is characterized by further innovation and efficiency in the delivery of statistical training, as well as further reinforcing the centrality of training within the broader statistical capacity development strategy.

2.4.2Collaboration with regional statistical training institutes and the GIST network

FAO has a long-standing experience of collaboration with numerous regional institutes for statistical training, which it has further expanded in recent years in order to cater to the increased training needs arising from the SDG indicators. Similarly to the overall number of SDG indicators, which has quadrupled compared to the MDGs, the number of SDG indicators under FAO custodianship has quintupled, going from only four to 21. Training has been the principal component of the FAO’s statistical capacity development strategy for SDG indicators since 2016, bearing in mind the greater fitness for purpose of training over technical assistance for familiarizing countries with new concepts, methods, standards and definitions. The majority (13 out of 21) of the SDG indicators under FAO custodianship were initially classified in the Tier III category, i.e. not having yet an internationally agreed methodology. Once the methodology for each new SDG indicator was approved by the Interagency and Expert Group on SDG indicators (IAEG-SDG), training became the initial step of the capacity development strategy, aimed to ensure that countries were able to report the SDG indicators in the medium-term.

In addition to the examples of FAO’s collaboration with African Statistical Training Centers, mentioned above, FAO’s collaboration with regional statistical training institutes also include the Workshop on Monitoring Food Security in the Context of 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, which was co-organized by the Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (SESRIC) in 2017; the Workshop on SDG Indicators under FAO Custodianship co-organized with the Statistical Institute for Asia-Pacific (SIAP) in 2018; the Training Workshop on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Land Holding and Use To Support the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the Arab Region, co-organized with the Arab Institute for Training and Research on Statistics (AITRS) in 2018, and the Regional capacity development workshop for countries from Asia and the Pacific on Farm Survey Based SDG Indicators, co-organized with SIAP in 2019.

Besides its collaboration with regional statistical training institutes, FAO is also a founding member of the Global Network of Institutions for Statistical Training (GIST), and has worked to support key objectives of the Network, including defining country needs in the wake of the new demands arising out of the 2030 Agenda and SDGs; assessing gaps in training offer and training needs; systematically sharing calendars and materials of training courses through a web-based platform; and harmonizing statistical training courses/curricula in line with international guidelines and standards. The vision of a global repository that gathers training material across multiple statistical domains as well as the 17 SDG Goals has recently become reality[6]: the Statistics portal of UNSDG-Learn, developed by members of the GIST Network, hosts numerous self-paced courses (including the entire suite of FAO SDG indicators e-learning courses), synchronous face-to-face resources, as well as micro-learning videos.

The GIST Network has also recently undertaken a study on the sustainability of training programmes at National Statistical Offices, which provides crucial insights into how training is organized in a number of countries, the key challenges faced by National Statistical Offices in prioritizing and delivering training courses – particularly in the context of the current pandemic – as well as useful ways to overcome these challenges and put training back onto a more sustainable path. FAO is taking the recommendations included in this study into serious consideration, and has already implemented a number of those that are applicable to international organizations, including: designing trainings that also target managers and decision-makers, such as to foster greater ownership and prioritization; shifting to online training and making optimal usage of all available online tools; carefully identifying training needs and the right persons that should receive training; and developing tailored programmes that may involve blending different training modalities[7].

One area recommended in the same study, which FAO is still in the process of implementing, is to more systematically evaluate the impact of training. FAO has hitherto relied predominantly on “level 1” evaluation, which – following Kirkpatrick’s model[8] of the four levels of training evaluation – usually consists of a short survey to be completed by the trainee either at the end of the training or shortly thereafter. Being quick and easy to administer, this type of evaluation is unsurprisingly the most common form of evaluation for statistical training courses[9]. However, aside from some basic information on how the trainees react to the training, it is not really able to tell us how much knowledge participants have gained (level 2), what changes have occurred as a result of the training in terms of learners applying the new knowledge in their work (level 3), or to what extent the material had a positive impact on the business/organization (level 4). Given the sizeable resources invested by FAO in developing and implementing such training programmes, the organization is currently working to upgrade its evaluations of statistical training programmes at levels 2, 3 or even level 4 as a better way of measuring the impact of the training programmes.

3.New training needs arising from the SDGs and the COVID-19 pandemic

3.1New training needs arising from the SDGs

The global SDG indicator framework is the foundation of the 2030 Agenda’s follow-up and review process. It comprises 232 unique SDG indicators, whose purpose is to monitor progress towards the 169 SDG targets. Data submitted by national statistical institutions are validated and analyzed on an annual basis by the respective custodian agencies that prepare storylines for each indicator, which form the basic building blocks of the global SDG Progress Report. This Report, in turn, is the main document informing the annual High-Level Political Forum (HLPF), which is responsible for the follow-up and review of the 2030 Agenda.

The novelties of the global SDG indicator framework, particularly with respect to its predecessor the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) indicator framework, have been well documented[10]. However, the question of how the novel nature and expanded scope of the SDG indicator framework has impacted training needs has not been thoroughly examined. The first key distinction between the MDG indicators and SDG indicators is the sheer size of the current framework compared to its predecessor. The 232 unique indicators dwarf the roughly 60 MDG indicators, outnumbering them almost four to one. In addition, a staggering proportion of the SDG indicators were initially completely new, and addressing new statistical domains not traditionally covered by official statistics. As a result, almost two fifths of the SDG indicators were initially classified in the “Tier III category”[11], not yet having an internally recognized methodology for their compilation. In the case of the SDG indicators under FAO custodianship, the proportion of indicators initially categorized as Tier III indicators was even higher, i.e. over 60 percent (13 out of 21).

The implications of these two changes alone on the training needs of countries are difficult to overstate. Countries were already struggling to produce many of the 60 MDG indicators (for instance, almost no country itself had been able to produce MDG indicator 1.9 on the “Proportion of population below minimum level of dietary energy consumption”), when suddenly they were confronted with an additional 88 Tier III indicators whose methodology was still in the making and which eventually they would have to become not only familiar with, but also able to implement in practice.

While all remaining Tier III indicators were effectively upgraded by the 2020 Comprehensive Review[12], after an arduous process of methodological development and approval under the aegis of the IAEG-SDG[13], the unmet training needs of countries are still manifest today (June 2021), when over 40 percent (97 out of 232) of global SDG indicators remain in the Tier II category, meaning that the majority of countries are still unable to produce them. From another perspective, for 9 out of 17 Goals, the proportion of countries and territories with available data is 60 percent or less[14]. In such cases, by definition it is difficult or often impossible to calculate regional and global aggregates and thus properly monitor progress at global or regional level.

Aside from the quantitative and qualitative leap represented by the expanded number of SDG indicators, in general, and the large proportion of them beginning their life with a non-established methodology, another key structural change with respect to the MDGs is the fact that the SDG indicators require the involvement of a wider spectrum of data providers – even entities that may not have hitherto been considered part of the National Statistical System (NSS). This requires the NSO to play a leading role in coordinating the NSS and in ensuring that data provided by other entities comply with national and international quality standards. Most of the NSOs in the world are not prepared to provide data stewardship to the many data producers within the NSS, and need to be trained to perform these important new functions.

3.2New training needs due to the COVID-19 outbreak

The COVID-19 outbreak at the beginning of 2020 has had a major impact not only on the socio-economic fabric of countries around the world, but also on the activities of the global statistical community. In particular, the COVID-19 outbreak has affected statistical activities at international levels in many ways:

1) Social distancing measures and lockdowns have caused a disruption in data sproduction at country level. In several countries, most ongoing or planned data collections such as surveys and censuses have been put on hold. It is difficult to predict when these activities will resume, but it is very likely that official national data on many SDG indicators, including those under FAO custodianship, as well as basic statistics, will be available with a delay, or not be available at all for 2020 and 2021 in many countries.

2) Because of these disruptions, most statistical capacity development programs in support of SDG measurement led by UN Agencies, and traditional data collections have been affected. Delays in implementation have occurred and some project objectives were significantly revised either to ensure projects stayed on scope and budget, or to adapt them to new data demands and data collection methods. According to a CCSA assessment of the COVID impact, around 80 percent of CCSA members reported being affected negatively in their ability to deliver training[15]. Most UN Agencies shifted technical assistance and training to the virtual space, increasing the number of webinars, on-line workshops and trainings, and remote-consulting.

3) The COVID-19 outbreak has triggered new data demands and priorities. Real-time information is needed to evaluate the impact of the outbreak on the socio-economic situation and livelihood of people, especially of the poor that have been hit more heavily by the interruptions of many economic activities. The breadth and depth of these new data gaps can only be filled using alternative data sources and new data collections methods and tools.

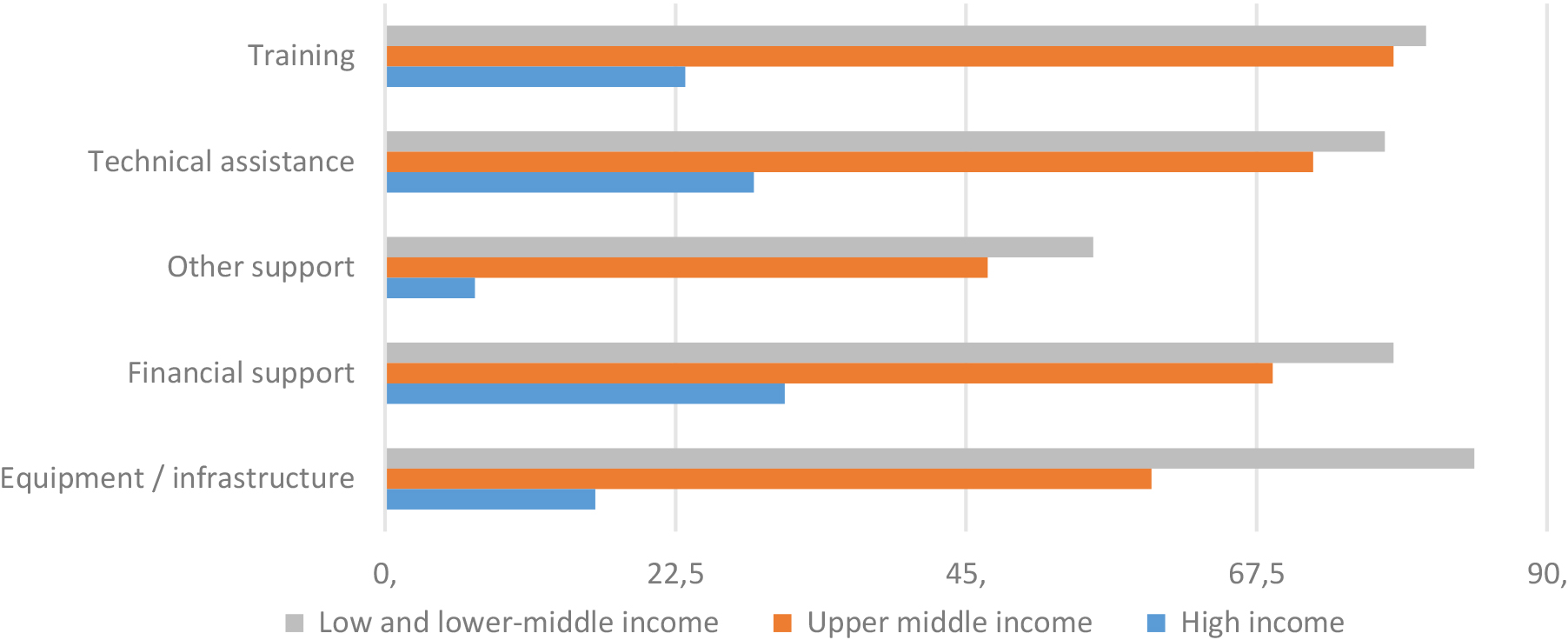

Of course, there are big disparities by income group in the capacity of countries to cope with the impact of COVID relying on their own resources. According to the UNSD/WB NSO assessments of COVID impact [16] conducted during 2020 and reproduced in Fig. 1 below, only few high-income countries were in need of any kind of support, while two-thirds or more of upper middle-income countries reported that they required technical assistance, training and financial support. In particular, 80 percent of low and lower middle income countries; 78 percent of upper middle income countries, and 23 of high income countries indicated that more training is needed. For low and lower-middle income countries, most voiced a stronger need for every type of support.

Figure 1.

Proportion of National Statistics Office staff in need of additional support to face the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Source: UNSD and World Bank, “Monitoring the state of statistical operations under the COVID-19 Pandemic”, 5 June 2020, Highlights from a global COVID-19 survey of National Statistical Offices.

The surveys also highlighted that only 58 percent of NSOs indicated that the office has adequate ICT facilities for remote training of staff and enumerators. In spite of these infrastructural issues, remote training of NSO staff has become widespread in countries of all income levels, although low and lower-middle income countries lagged somewhat behind.

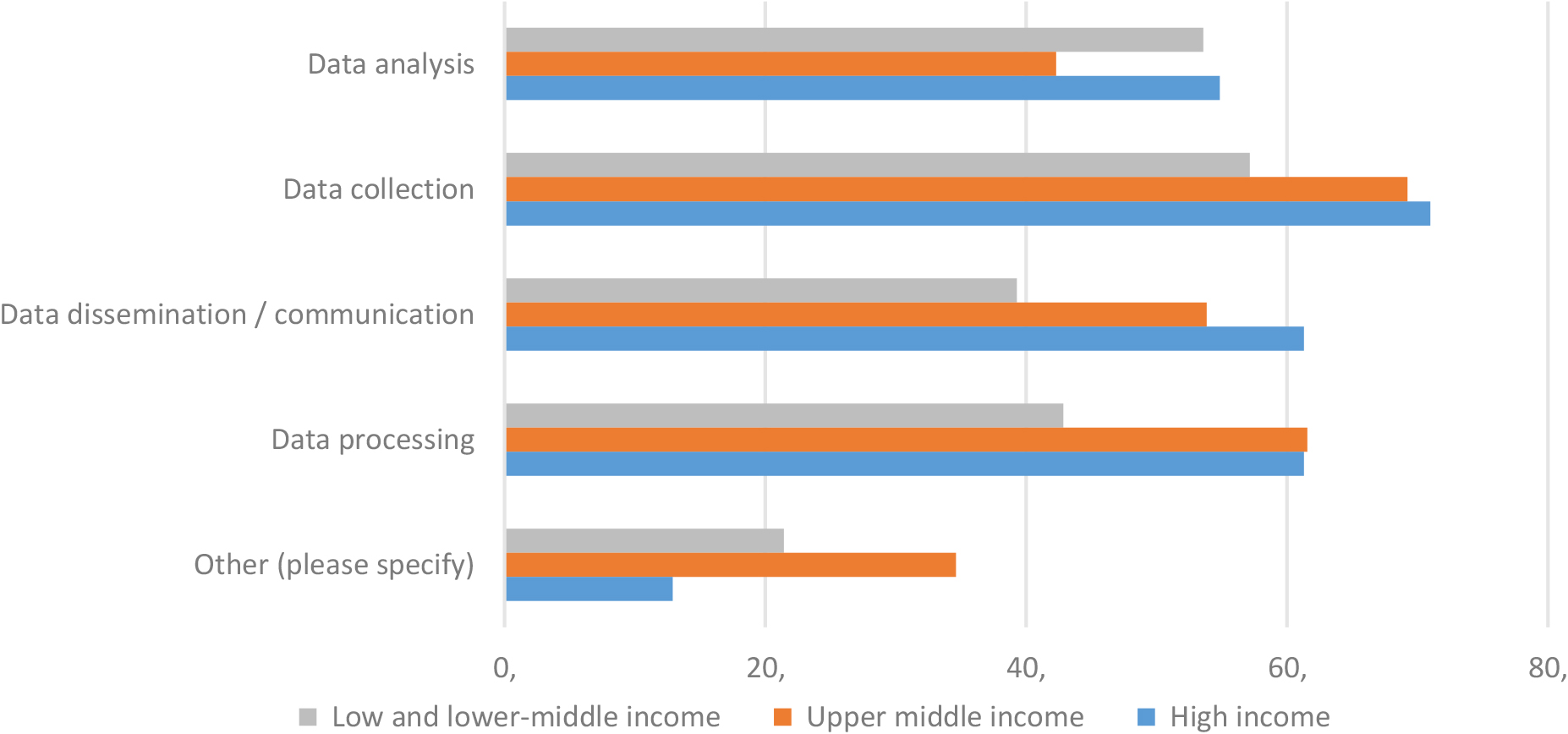

Figure 2.

Proportion of NSO staff participating participate in remote trainings amidst the COVID-19 crisis by topics. Source: UNSD and World Bank, “Monitoring the state of statistical operations under the COVID-19 Pandemic”, 5 June 2020, Highlights from a global COVID-19 survey of National Statistical Offices.

Most UN Agencies have immediately organized a series of interventions to mitigate the most unsettling effects of the pandemic on the statistical programmes and activities at country-level, including the provision of financial support, equipment and infrastructure support, technical assistance and training. As can be seen in Fig. 2 below, generally speaking over 40 percent of NSOs reported that their staff participated in remote trainings amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, with the highest concentration of these trainings focused on data collection. Trainings on data analysis, processing and dissemination also saw a high attendance, with some variation across countries of different income groups.

FAO has developed an integrated set of complementary actions in response to these challenges:

1) In order to evaluate the impact of the outbreak on food security/food access and their causes, FAO has planned to conduct repeated, rapid assessments of food insecurity using the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES). The FIES[17] is the basis of one of the official indicators to monitor SDG target 2.1, i.e. SDG indicator 2.1.2 (prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity). The FIES module has been adapted to capture the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on households’ability to access food, slightly modifying the reference period and wording of the FIES questions to make them more effective in monitoring food insecurity trends in relation to the pandemic. Moreover, specific questions have been added in order to isolate the impact of COVID-19 from that of other concomitant causes of households’ inability to access food. Several countries have already contacted FAO requesting remote training and technical support to adapt their FIES module to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and make it fit for an emergency situation, as well as for using alternative modalities of data collection (phone or web interviews).

2) Scale up the activities of FAO’s newly established Data Lab for Statistical Innovation to: a) strengthen the capacity of the Organization to produce and analyse real time information from new data sources so that emerging crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can be pro-actively addressed; and b) fill data gaps and validate available data at country-level with alternative data sources. In particular, the Data Lab was created in 2019 to bolster the organization’s capacity to use alternative data sources (e.g. big data, satellite data, sensor data and web data) and innovative statistical methods (nowcasting, small-area estimation, text mining, etc.) to complement traditional data sources and address the key challenges of FAO’s statistical system, such as large data gaps at the country level, outdated information, lack of disaggregated data. The knowledge acquired on these new methods and tools in the Data Lab unit will be transferred to the rest of the Organization, but especially to member countries, though the implementation of dedicated training programmes fostering the modernization of national statistical systems.

3) Accelerate the use of Earth Observation (EO) data to produce crop mappings, crop area and crop yield estimates and forecasts. In 2019, FAO laid out a multiyear workplan[18] to progressively boost FAO’s internal capacity to generate robust crop statistics within the new EO big data landscape, combined with machine learning and deep learning algorithms, and to build capacity in countries for the uptake of the EO-based solutions by delivering in-country technical assistance and training. The implementation of this workplan has already kick-started with the establishment of key partnerships (with the European Space Agency, the Academia – e.g. UCL Louvain, and other UN Agencies – e.g. UNODC), the recruitment of a Spatial Data Scientist, and the launch of country-level activities in pilot countries (Senegal, Uganda, Lesotho, Afghanistan).

In response to the data needs driven by the COVID-19 outbreak, FAO plans to accelerate the implementation of its workplan on the use of EO data in order to produce high resolution national crop maps, crop area and crop yield estimates of the main crops, thus expanding its implementation to 40-60 countries in the next two years.22

The information produced will be used to forecast the agricultural production of key commodities, ensuring proper planning of the downstream operations of their value-chain. In the medium term, this information will help identify strategies that will facilitate the access of small-scale food producers to markets and therefore counterbalance more rapidly the possible impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on their livelihoods. Finally, in a second phase, methods to produce this information will be documented and transferred to all countries through training programmes and technical assistance

4) Provide guidance and support to countries in order to collect nationally-representative information using official data sources, but by adopting new data collection tools. This action foresees the use of alternative data collection modes for existing farm surveys to minimize or avoid face-to-face interviews (during the quarantine period). Existing good practices of developed countries in using alternative modes of data collection to face-to-face interviews (e.g. use of registers, phone interviews, web interviews) are not always easy to extend to developing countries, given the absence/low quality of farm registers and the under-coverage of mobile networks in remote rural areas. Moreover, specific constraints are posed when administering complex questionnaires which are not manageable by telephone.

Other solutions could, however, be envisaged and tested: i) substantially simplifying existing questionnaires that could be administered through simplified phone interviews for household-based farms and through web applications for the non-household sector; ii) applying innovative methods for reducing the sample size in order to limit the number of face-to-face interviews, while maintaining sufficient levels of representativeness of the sample; iii) developing specific protocols for remotely organising efficient training of supervisors/enumerators; and v) analysing the possibility of using unexplored existing national data sources. All these solutions would of course imply a minimum availability of conditions of accessibility and communication at country level. The guidelines prepared on the basis of the literature review and case studies in pilot countries will be the basis for organizing training programmes and providing technical support to countries in the use of alternative data collection modes and data sources.

3.3New data-related skills

The traditional educational background of professional statisticians may no longer be sufficient to deal effectively and proficiently with the new types of data sources and the new analytical and computational requirements that should be essential components of the skill-set of a contemporary statistician.

Firstly, Big data are becoming pervasive in today’s society, with commercial entities, government agencies and academic institutions all seeming progressively interested in capturing and analyzing them. Big data are not usually collected through planned processes and consequently cannot be the object of traditional data handling approaches. In order to analyse Big data, it is necessary to explore large, complex and seemingly unrelated sets of raw data, looking for significant correlations and new and unanticipated connections among them, using artificial intelligence (AI)-driven data analytics platforms, powerful enough to handle data sets of huge dimensions. Machine learning, which is an automated process that extracts data patterns using AI algorithms, is the way in which Big data are converted into a new type of knowledge. Big data analytics can be defined as the iterative and exploratory process of using advanced technologies and analytical techniques to reveal critical information, such as hidden and/or meaningful data patterns, trends and associations. Moreover, the need to integrate different data sources, the widespread use of geospatial information, and the growing application of new technologies, such as cloud computing, are all developments that have led to the emergence and rapid propagation of a new job profile, the “data scientist”. Data science involves the computational aspects of carrying out a complete data analysis, including acquisition, management, manipulation, visualization, and transformation of Big data into usable information and knowledge. This typically involves some mixture of statistics and large-scale computing. More and more universities today are incorporating data science into their statistics curricula, providing an opportunity for students to learn a new approach to statistical thinking, practice and computation[19].

These kinds of professionals are still generally rare in National Statistical Offices, especially those of developing countries. Their skill-set is also almost impossible to acquire solely through short-term training courses or training-on-the-job. Possible solutions are therefore for NSOs to recruit a higher proportion of data scientists – properly trained in accredited Universities - or to encourage young staff to follow post-graduate programmes in this area. Eventually, when these new kinds of professionals have reached a critical mass within the organization, the most efficient way of employing their skills is to create mixed units that combine traditional statisticians and data scientists to facilitate the application of traditional and new approaches for addressing the statistical challenges faced by the organization from different perspectives.

4.Statistical capacity assessment of training needs

Having reviewed the new training needs arising from the SDGs and COVID-19 and identified new data-related skills that require targeted training, this section presents an analysis of training needs related, in particular, to the SDG indicators under FAO custodianship. The section will also provide some recommendations on how to better coordinate capacity assessments among international agencies.

4.1The 2019 FAO SDG Capacity Assessment: Analysis of training needs

The Statistical Capacity Assessment for the FAO-relevant SDG indicators was conducted to provide insights about the strengths and weaknesses of member countries’ national statistical systems regarding their capacity to monitor and report the 21 SDG indicators under FAO custodianship. By the closing date of February 2020, 114 countries had answered the questionnaire, yielding a global response rate of 58 percent[20].

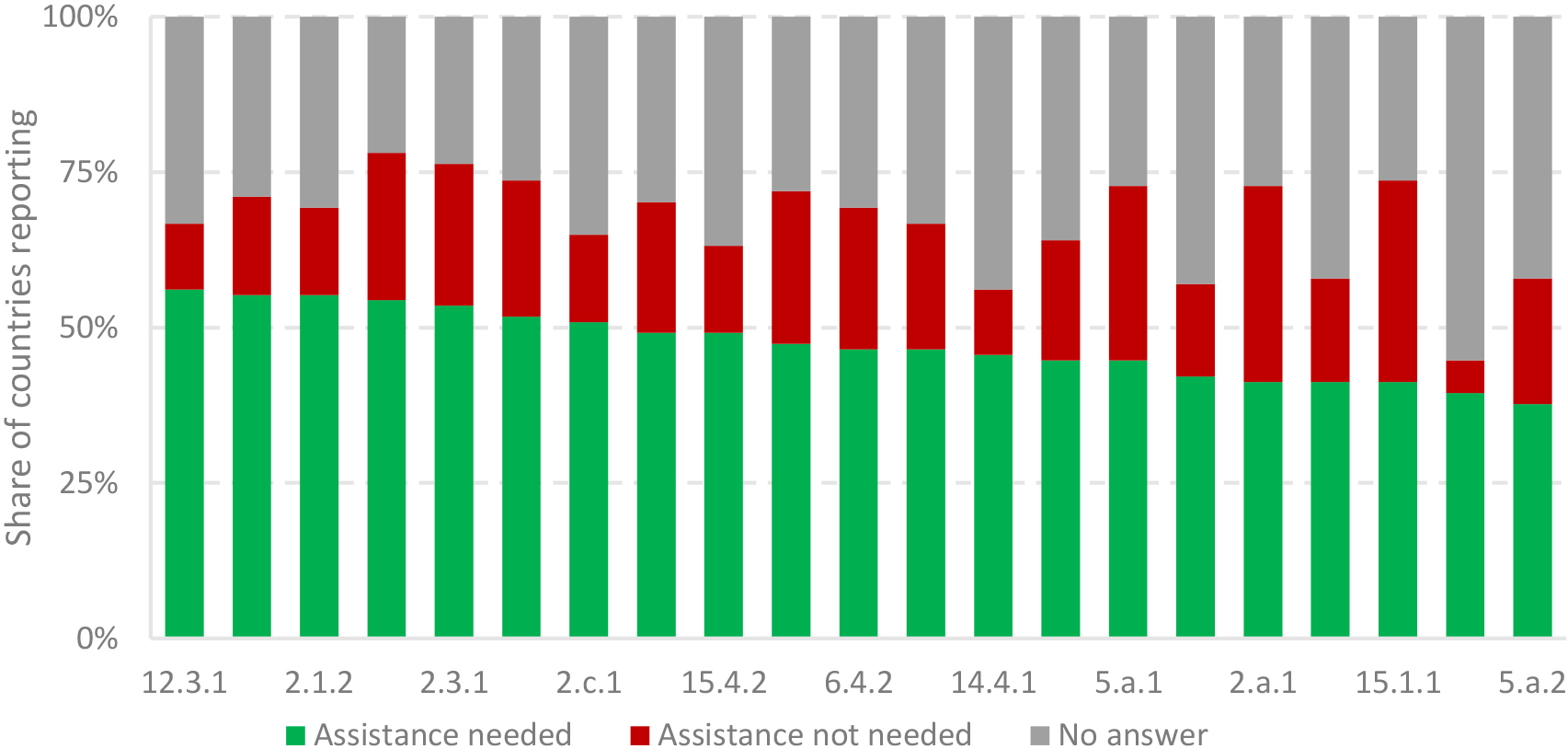

Figure 3.

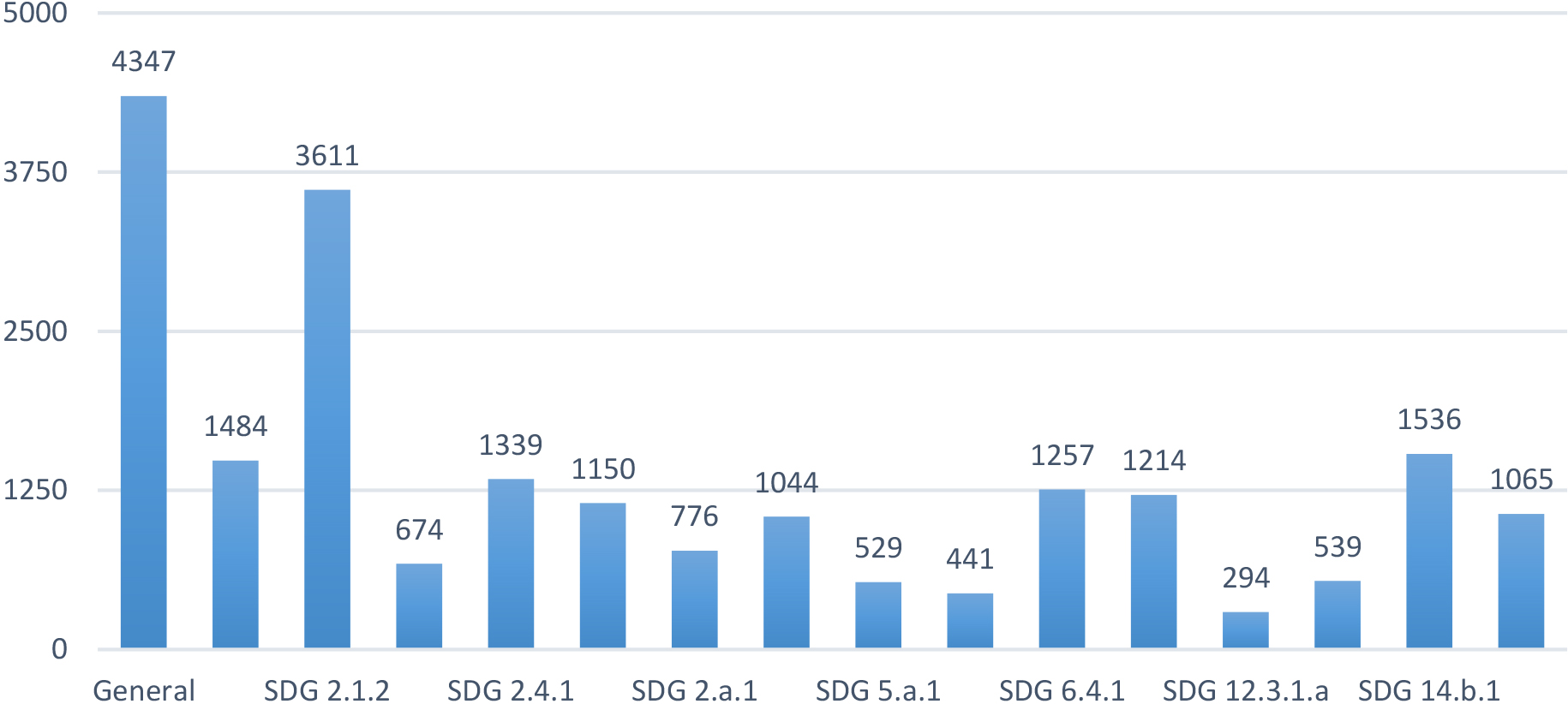

Requests for assistance for producing/compiling SDG indicators, by indicator.

The Assessment aimed to provide insights about the strengths and weaknesses of the national statistical systems worldwide, concerning their capacity to monitor and report the SDG indicators under FAO custodianship, with the underlying intent of assisting FAO in designing more targeted interventions and mobilizing resources to support countries in producing the relevant SDG indicators.

The survey questionnaire was organized in various sections to collect information on the national coordination mechanisms for SDG reporting, current food and agriculture data availability, plans for filling data gaps, and needs for technical and financial support. The target respondents were the National Coordinator for SDG Monitoring or the SDG focal point nominated by the Director General of the National Statistics Office in each country.

Overall, the survey results showed that the majority of countries do not regularly conduct most of the key data collection activities that provide the main data sources to compile the SDG indicators related to food and agriculture. In addition, most data collection activities not carried out recently are not generally planned to be conducted in the near future. As a result, the expectation is that these countries will not be able to compile many SDG indicators that primarily rely on such data in the short and medium-term. It is important to highlight that this situation, assessed before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, can only have deteriorated due to the lockdowns and related restrictions imposed by the pandemic, as documented in the 2020 UNSD/WB survey of NSOs examined in the previous section.

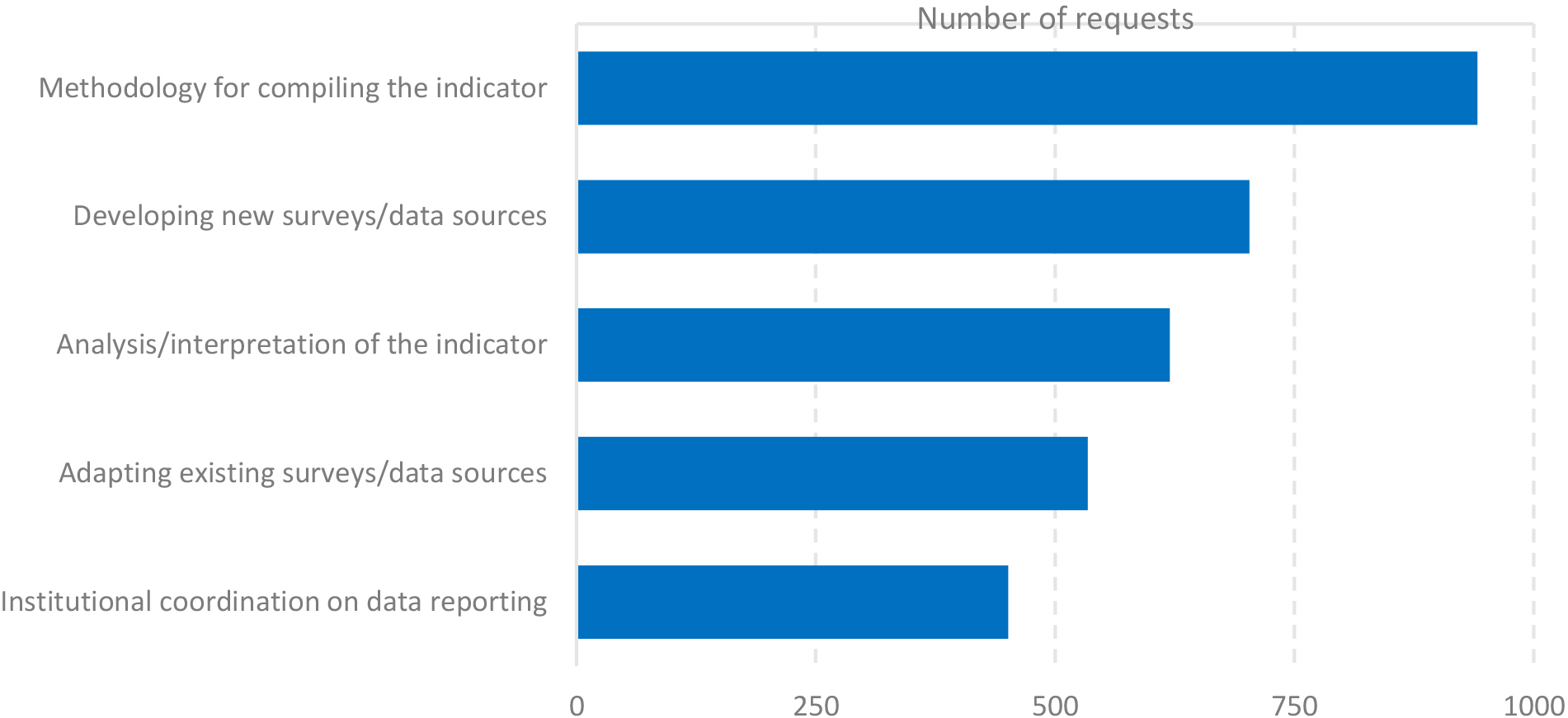

Figure 4.

Number of requests for assistance for producing/compiling SDG indicators, by type of assistance.

Figure 5.

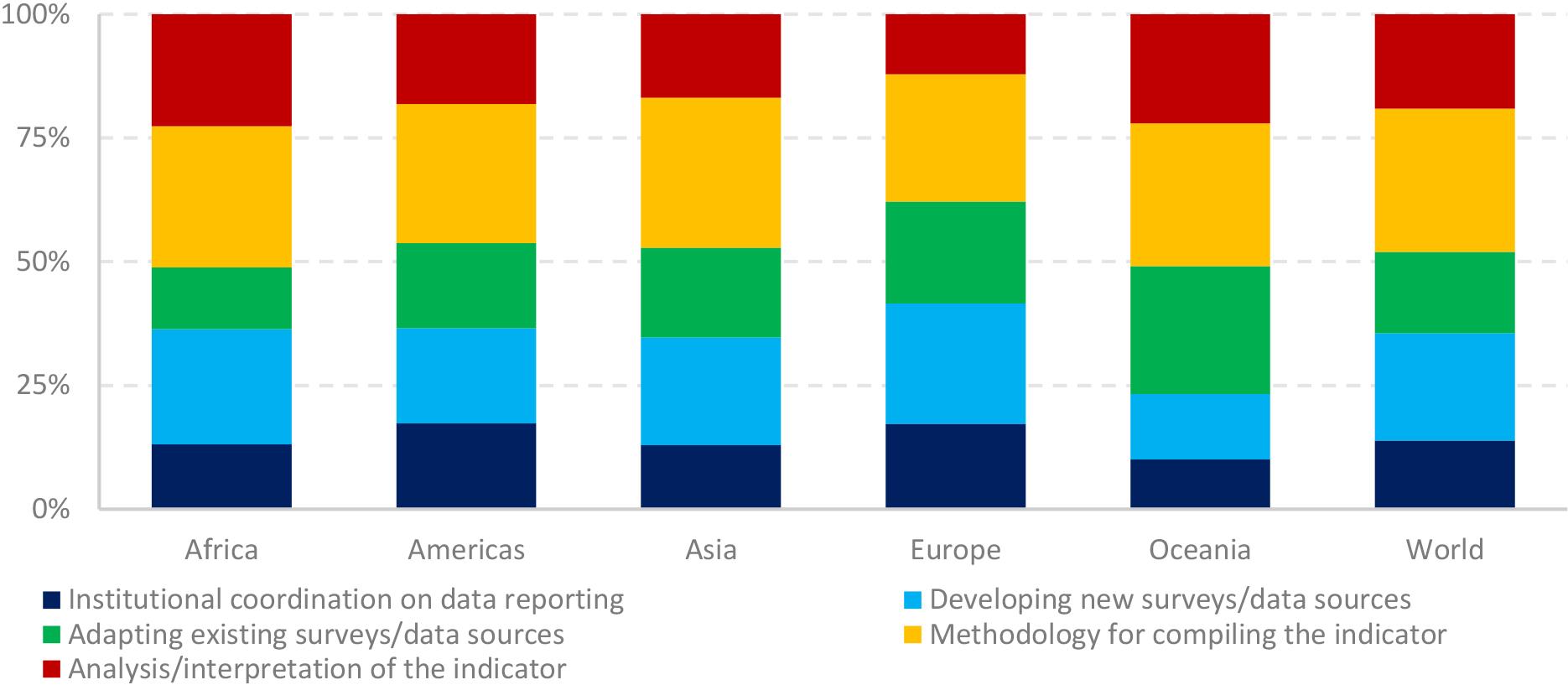

Types of assistance requested by region.

Another key finding of the 2019 FAO assessment was that most countries seem to have established the required mechanisms for coordinating SDG monitoring and reporting, yet many were still not able to identify an indicator-specific national focal point for most of the SDG indicators under FAO custodianship. This is a major impediment to effective reporting that explains many of the existing data gaps, as well as certain discrepancies between the data available in the global SDG database and the information reported by countries. The absence of indicator-specific focal points not only suggests shortcomings in national coordination mechanisms, but, crucially, hampers the potential effectiveness of training programmes. In this scenario, countries will typically nominate an ad-hoc participant to a training initiative organized by a custodian agency, who is not necessarily the person that will continue to be responsible for coordinating the national reporting of the indicator in the future, therefore potentially underutilizing the knowledge gained.

The final critical finding of the assessment was that 75 percent of countries reported that they would require some form of assistance to produce SDG indicators under FAO custodianship. This is not all too surprising considering that the statistical capacity of developing countries is typically constrained by the low availability of resources (internal or external), and therefore depends substantially on external capacity development support (both training and technical assistance) to maintain currently used data sources, enhance the quantity and quality of data required for the publication of SDG indicators, and strengthen inter-institutional coordination. The dependency on external assistance and additional resources is an important indication of the capacity of countries’statistical systems. Figure 3 shows that in general, at least 40 percent of the countries requested support for producing and compiling a given SDG indicator. This figure exceeds 55 percent in certain cases.

One evident limitation of the 2019 FAO Statistical Capacity Assessment is the fact that the questionnaire did not distinguish the principal modality of capacity development, i.e. training and/or technical assistance. On the contrary, relevant questions only explicitly mentioned technical assistance rather than training, to the extent that, in hindsight, technical assistance was to some degree conflated with capacity development in the broader sense.

Figure 6.

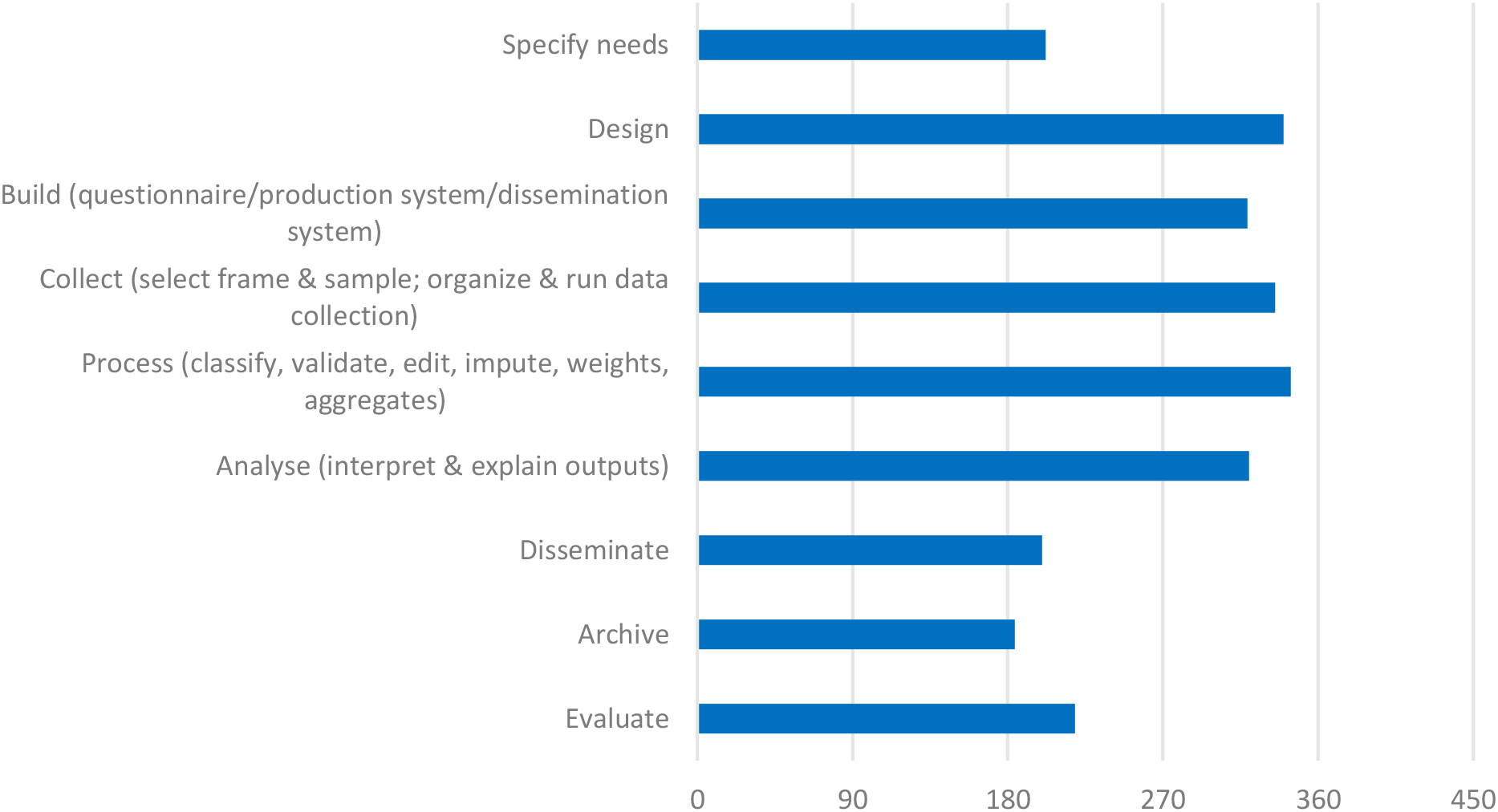

Number of requests for assistance for data collection, by phase (multiple requests can be made for any phase).

Despite this, if we accept the premise that questions regarding technical assistance may have probed into broader capacity development needs that included training, it may be possible to infer training needs more specifically from the specific type of assistance requested. Figure 4, for instance, shows the number of requests for assistance for producing and/or compiling the SDG indicators under FAO custodianship, disaggregated by type of assistance. As can be seen, assistance on the methodology for compiling the indicator gathered the highest overall number of requests, which is revealing because this is precisely the type of support, within the typology of Fig. 4, which is best served by a focused training programme rather than technical assistance missions, according to what has been explained in section I.b above. Another type of assistance within the typology of Fig. 4 that could also potentially benefit from training is the analysis and interpretation of the indicator, which comes in third place based on the number of requests. By contrast, developing new surveys or other data sources, adapting existing sources as well as fostering institutional coordination on data reporting, are all activities that are more effectively supported by a technical assistance stricto sensu, in which an FAO officer can work side-by-side with the national counterpart and flesh out the most appropriate solution.

Following the same typology of capacity development needs, and the premise that training would be a more effective delivery modality for supporting countries with the methodology for compiling the indicators and with the analysis and interpretation of the indicator, it is also possible to distinguish the intensity of training needs across continents. Figure 5 reveals some differences regarding the type of assistance requested across continents. In Africa and Oceania, for instance, the combined requests for methodological support and support on the analysis and interpretation of the indicator account for over 50 percent of requests overall, pointing to a key role for training in the continent. In the Americas and Asia, the same proportion is 46 percent, whereas in Europe it is only 38 percent, indicating a relatively smaller role for training in this region compared to technical assistance.

In the absence of specific questions distinguishing between training and technical assistance needs, it is also possible to approximate this distinction based on a different typology of support needs, this time by phase of data collection. These phases are broadly based on the Generic Statistical Business Process Model (GSBPM). Figure 6 shows which phases of data collection processes require the most/least support.

The question then becomes which of these phases is more amenable to training and which to technical assistance. In our view, training would be most effective as a capacity development modality in the early preparatory phases as well as late phases in the GSBPM cycle, whereas technical assistance would be most appropriate for the intermediate phases that require a more hands-on approach. Therefore, we see training as being more effective for supporting countries in the specification of needs, design, analysis, dissemination, archiving and evaluation phases, whereas technical assistance as more appropriate for the process, building and collection phases. With this admittedly somehow coarse distinction, the overall number of requests for support by countries that could be addressed through training slightly exceeds the number of requests that could be addressed via technical assistance.

All these result are particularly useful for planning purposes, as capacity development programmes can be better tailored with regard to their scope, modality and regional preferences.

4.2The need to better coordinate capacity assessments among international agencies

Before developing the 2019 Statistical Capacity Assessment, FAO carefully reviewed other recent studies of statistical capacity assessment to determine the degree to which some information could already be derived therefrom, and therefore reduce the extent of FAO’s questionnaire accordingly, in the interest of relieving countries’response burden. One could broadly distinguish between two main types of assessments:

On the one hand, there are general “outcome-level” assessments that are meant to monitor the results of capacity development efforts, and therefore can provide some evidence of unmet training and/or technical assistance needs. Such assessments include the World Bank’s Statistical Capacity Indicator Dashboard[21], the Open Data Watch’s Open Data Inventory[22], as well as the still-to-be developed SDG indicator 17.18.1 “Statistical capacity indicator for Sustainable Development Goals”. Such type of outcome-level assessment can be useful in performing comparisons across countries and therefore in selecting countries to be targeted for capacity development initiatives. However, they are less suitable for clarifying the precise type of support that is appropriate for a given capacity gap. On the other hand, there are “input-level” assessments, which seek not only to provide aggregate scores and country rankings, but also to elucidate the underlying drivers and factors constraining the capacity of national statistical systems to produce data. Like the aforementioned FAO 2019 Statistical Capacity Assessment, such assessments may be able to indicate not only the unmet capacity development needs in general, but also those needs that are better served by training compared to other types of support. Such assessments include the African Development Bank’s (AfDB) “Country Assessment of Agricultural Statistical Systems in Africa”[23], ESCAP’s 2017 “Report on the Capacity Screening of Economic Statistics in Asia and the Pacific”[24], PARIS21’s “Measuring Statistical Capacity Development” reports[25], as well as the UN Statistical Division’s “Assessment of the Statistical Capacity of National Statistical Systems to Compile Global SDG Indicators”[26].

Despite the number of such assessments, none of them seemed to be sufficiently focused on agriculture- and food-related statistics and/or SDG indicators. They are too generic or not comprehensive enough to extract lessons about the compilation the FAO-relevant SDG indicators. On the other hand, meaningful results can only be extracted with a large country coverage, as well as consistent information coming from various data sources. Bearing these two considerations in mind, FAO deemed it necessary to develop a standard questionnaire addressed to all member countries in order to ensure international comparability.

The downside of this approach is that the reporting burden on countries continues to increase instead of decrease, which may provoke criticism of international organizations. Clearly, there is a need to reconsider the approach whereby individual international organizations undertake their own statistical capacity assessments, likely increasing the burden of respondent countries and international organizations themselves. There are also cases where assessments are carried out, but their results are not published or not published in a way that can be informative to other organizations, further limiting their potential value.

Whereas a capacity assessment will inevitably require the gathering of information specific for each international organization, there is a lot of information that could be common for all or almost all agencies. Specific information includes qualitative information on the national statistical infrastructure, fleshed out in a way that sheds light on the real capabilities of the countries in implementing the specific indicators, with reference to specific definitions, classifications, standards and data sources. By contrast, there is a plethora of general information that could be useful for all agencies, including information on the main census/survey instruments in place, how they are organized and what is their frequency, the structure of the National Statistical System, the role of the National Statistical Office, the presence of an SDG reporting coordination body and NSO SDG focal point.

All this points to the need for a much more coordinated approach among international organizations in carrying out statistical capacity assessments. One straightforward solution would be to determine a common core questionnaire that would be administered with an agreed regularity (for example every three years), to be complemented by a system of rotating modules that would collect agency-specific information at specific intervals. The common core questionnaire will itself greatly reduce the reporting burden on countries, whereas the rotating modules sent at specific intervals will further accommodate countries by ensuring that a large number of similar requests are not addressed to National Statistical Systems during the same reporting period. In the past, FAO presented this approach to the Global Network of Institutes for Statistical Training, but unfortunately it did not gain enough traction at the time. We also note that the UN Statistical Division’s statistical capacity assessment to some extent approximates the requirements of the common core assessment described above, although it is probably too generic to serve this purpose in its current format and would therefore require to be further adapted.

5.Innovative learning solutions and delivery models

5.1Combination of various training modalities and tools

New complex global challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, all call for innovative learning methodologies and delivery solutions, involving multiple stakeholders within and across countries. These include experience-sharing events and live interviews, self-paced e-learning courses, mobile responsive programmes, technical webinars and online tutored blended learning programmes, that are relevant – now more than ever – to maximize statistical capacity development support, foster countries’ ownership, and ensure large-scale uptake and impact. In essence, it is the combination of different learning modalities, appropriately blended into a coherent learning programme, which is likely to have the greatest impact, with one modality reinforcing the strengths and dampening the limitations of another.

The strategic choice of FAO in the specific selection of innovative learning solutions is based on each solution’s advantages in: 1) reaching a wider target audience and giving access to training to geographically dispersed communities, 2) having a greater impact, bearing in mind that training can be made available to anyone, anywhere and at any time and can thus be integrated in a “blended” manner, in combination with other methods; and 3) having a greater return on investment, allowing to reach thousands of individuals throughout the world therefore, resulting in a highly cost-effective method.

A key training tool that responds to all the three criteria above is the e-learning course[27]. E-learning materials provide “just in time” resources suitable for both self-study and on-the-job training, where individuals learn at their own pace, anywhere and anytime. This can be a particularly useful attribute, for example, in conflict and post-conflict zones, where accessing decision-makers and other stakeholders raises even greater challenges. In addition, e-learning resources can be easily integrated with other training modalities. Regarding the return on investment, developing e-learning programmes is indeed more expensive than preparing classroom materials or organizing training-of-trainers’events – especially when multimedia or highly interactive methods are adopted. However, this initial cost is more than offset by the substantially lower delivery costs for e-learning as compared to traditional face-to-face trainings, which require printing of materials, instructor time, and participants travel and job time lost to attend classroom sessions. In addition, while traditional methods can reach a very limited number of individuals per year, e-learning can reach a theoretically unlimited number of individuals throughout the world, therefore providing a highly cost-effective method.

For the above-mentioned reasons, FAO has designed and developed multilingual SDG Indicators e-learning courses, offered free of charge as global public goods through the FAO e-learning Academy (e-learning.fao.org), both to contribute to the implementation of the SDG 2030 Agenda and to concretely support member countries in the collection, analysis, monitoring and reporting of the SDG indicators under FAO custodianship. These courses (see the complete list in Annex 1) explain the relevance of the SDG indicator for the SDG target, describe step-by-step the compilation methodology agreed at international level, and guide countries in the collection analysis, interpretation, monitoring and reporting of each SDG indicator, under FAO custodianship.

The content of the SDG Indicators courses is gender-inclusive, culturally sensitive, engaging, and rich in interactive elements, examples, relevant case-studies, step-by-step walk-throughs, guided tutorials, hands-on activities and interactive case-based scenarios. The content is developed following a logical learning sequence that is aligned with current state-of-the-art adult learning methodologies, theories and strategies, thus offering a learning experience with a clear purpose, with realistic objectives, measurable outcomes, and a learning pathway that matches the targeted professional profiles.

As mentioned above, a key advantage of e-learning resources is that they are easily integrated with other training modalities[28], primarily through the following mechanisms: i) asynchronous self-paced e-learning for Internet delivery and downloadable format; ii) synchronous Internet-based e-learning courses led by subject matter experts (tutors) and facilitators and iii) asynchronous self-paced e-learning and face-to-face training. As such, FAO is developing a number of targeted capacity development activities by combining and integrating the SDG Indicator e-learning courses. In some instances, in order to ensure the same level of basic knowledge and skills, participants in training events have been requested to take the online self-paced e-learning courses in advance, as a pre-requisite for their participation in a training event, therefore offering a combination of online and face-to-face approaches. In another instances, the self-paced e-learning courses are integrated with online blended learning programmes, specific peer-to-peer activities and assignment, online topic-based discussions, Q&A fora and live sessions. Such blended learning programmes increase experience sharing and social interaction between participants, while framing the challenges to the national context. They have therefore proven to be very successful in providing an individualized learning experience and in supporting national processes.

Figure 7.

Number of learners per SDG indicator FAO e-learning course.

A third example are online technical webinars based on the FAO e-learning courses. These live sessions have proven particularly successful in providing “just-in-time” training opportunities, once again based on a combination between live events and online self-paced courses. Furthermore, a growing number of academic institutions have included the FAO SDG indicator e-learning courses in their curricula. In particular, the Universities of Buenos Aires (Argentina) and Parma (Italy) have integrated the FAO e-learning courses in the programme of their joint International Master in Food Technology (MITA), thus offering a new combination of training methodologies merging formal university education and online self-paced courses.

5.2Planning and assessment of training to maximize the effective use of acquired know-how

In order to respond to the specific learning needs and maximize the impact of training initiatives, there are a number of good practices and lessons learnt that should be taken into account to the extent possible. Firstly, the training intervention should be tailored and targeted to country-specific needs. A good way of doing this is by conducting multi-stakeholder and multi-disciplinary learning needs assessments, in close collaboration with the target audience groups; collaboratively designing the learning intervention based on the country needs and developing the content capitalizing on local expertise, involving country institutions in the design, development and delivery. It is also useful to deliver training interventions in the local language or benefiting from the support of a local institution for the translation, as well as incorporating both local specificities and challenges, as well as regional and global perspectives.

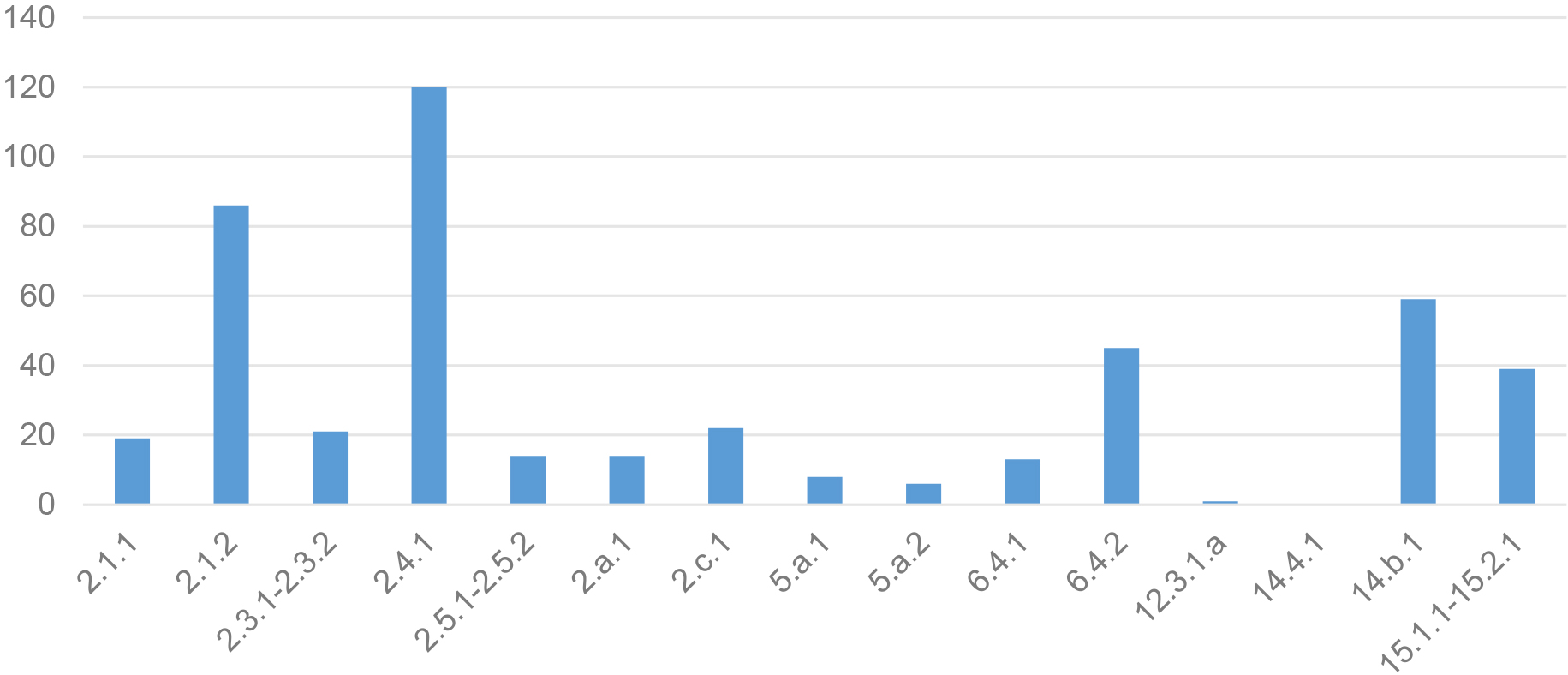

Figure 8.

Badges issued for SDG e-learning courses (all languages).

The current COVID-19 context has also highlighted the usefulness of short, mobile-compatible and responsive courses that allow for “learning-on-the-go”, anytime and anywhere, providing a much-coveted flexibility to in-service professionals who wish to upgrade their competences. For similar reasons, offering an offline, downloadable version of the courses, to enable access even in low bandwidth and poor-connectivity areas, should become standard practice across international organizations.

Last but not least, when it comes to organizing live events – whether virtual or physical – the importance of correctly timing the intervention with respect to the practical implementation or bottleneck at hand, cannot be overemphasized. To some extent, this issue is related to the concept of supply versus demand-driven interventions. In the past, supply-driven interventions were not only based on what was available, rather than on what was really needed by countries, but they also paid little regard to whether the training was appropriately timed with respect to the data cycle of each country. For instance, the impact of a training on new census of agriculture guidelines would be incomparably higher if the training took place during the early preparatory phases of a new census, rather than five years before the next census is planned. This is therefore another critical dimension to consider in the planning and tailoring of training interventions.

5.3A closer look into the profile of participants of FAO e-learning courses

Up to now, the cumulative total number of learners of the FAO SDG Indicator e-learning courses is 21,300, of which one fifth are learners of the general introductory course, and the other four fifths are learners of different SDG indicator courses, as shown in the graph below. The e-learning course on SDG indicator 2.1.2 – Prevalence of Moderate and Severe Food Insecurity – appears to be the most sought after (see Fig. 7), whereas the course on 12.3.1.a – Food Loss Index – appears to have gathered the fewest learners. However, a proper comparison between the number of learners across SDG indicators should also take into account the different release dates of each course, available in Annex 1. For instance, the e-learning course on 12.3.1.a was released a full two-and-a-half years after the course on 2.1.2, owing to the much later date at which the methodology of 12.3.1.a was definitively approved by the IAEG-SDG.

Knowledge assessment tests are used consistently throughout the FAO SDG-indicator e-learning courses to reinforce learning, increase active participation, increase retention and memorization of concepts ad principles, increase interactivity and provide learners with an opportunity to practice their understanding of the indicators and their interpretation. As such, the courses now include short tests at defined intervals throughout the course, as well as a final general evaluation. Passing the final scenario-based performance evaluation with a score of 75 percent or higher provides learners with an official certification granted by FAO through the Digital Badges system, which certifies the acquisition of competencies that match the professional profiles required by countries. The chart below illustrates the number of such Badges hitherto issued across the different SDG indicator e-learning courses. These numbers should also be qualified taking into consideration not only the different release dates of the courses themselves, but also the fact that the Badge certification system was in many cases introduced after the initial release date. For example, while the course on SDG indicator 2.4.1 appears to have the greatest number of certified learners, the proportion of certified learners out of the total number of students is greater for SDG indicator 14.b.1, given that this course has fewer overall learners.

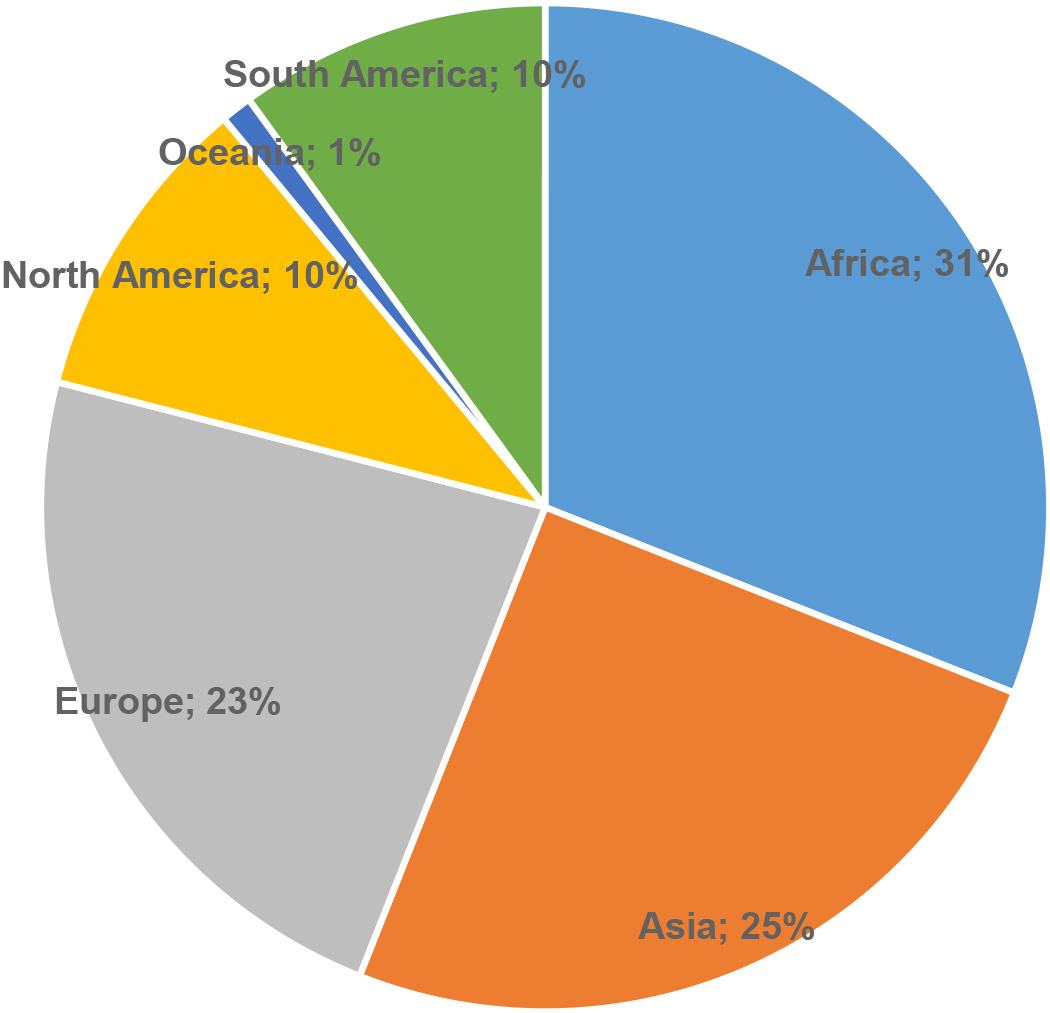

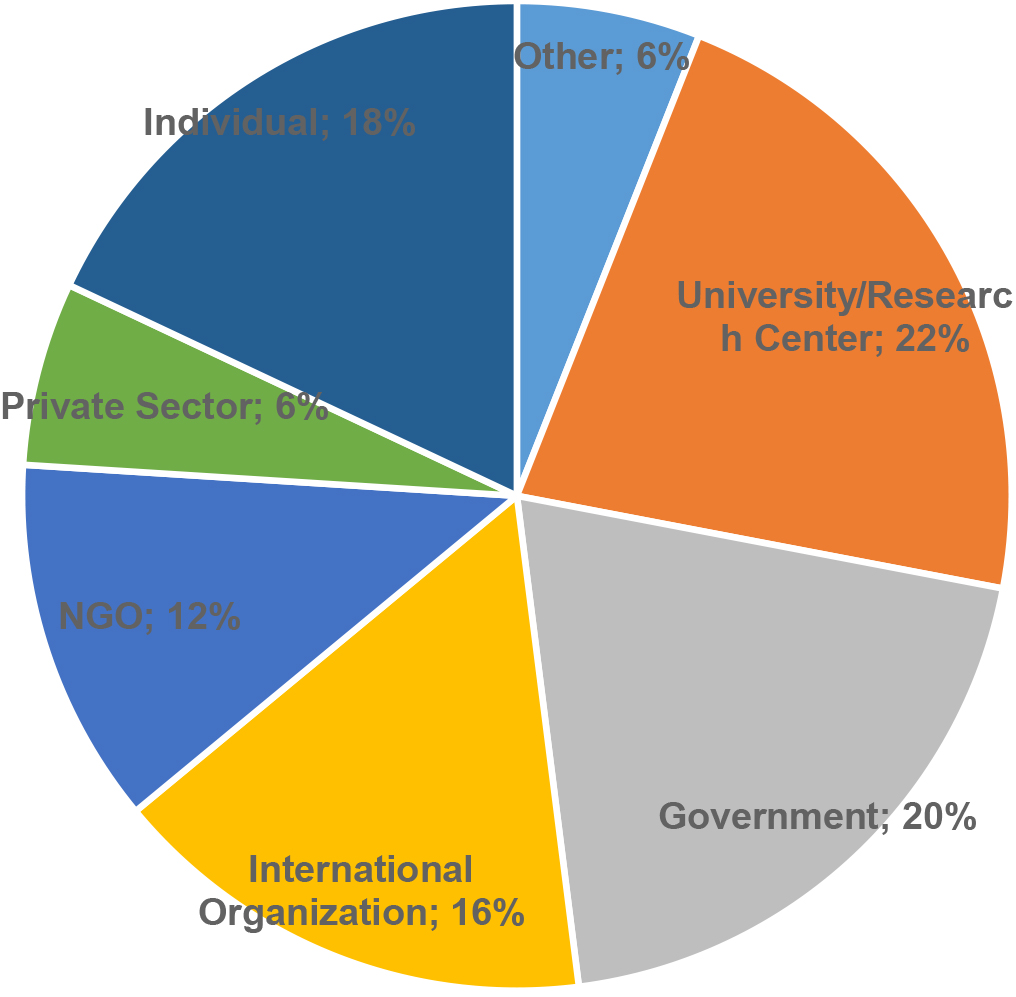

In addition, the first pie chart below illustrates the geographic distribution of the learners of the FAO SDG indicator courses. As can be seen, the greatest share of learners are from Africa (31%), followed by Asia (25%), Europe (23%), North and South America (both 10%) and Oceania (1%). The second pie chart below illustrates the institutional background of learners. Learners from academia (22%) and from government institutions (20%) account for the largest share of learners, followed by an encouraging share of 18% for private individuals without any particular organizational affiliation. Learners from international organizations (16%), non-governmental organizations (12%), the private sector (6%) and other types of institutions (6%) account for the remaining share of users of the FAO SDG indicator e-learning courses. The varied geographical and institutional origin of learners attests not only to the ability of FAO’s SDG indicator e-learning courses to reach a broader audience, but also to the wider appeal of the courses well beyond their primary intended target group of government officials.

5.4Training targeted to different users of statistics

Because statistics are only relevant if they are widely used, an integrated statistical capacity development programme should also aim to build not only the technical and function capacities of data producers, but also the data literacy of data users. This is an area that is generally more difficult to tackle given the variety of possible data users and the level of investment required to build data processing and analytical skills among all potential users.

For this reason, training that targets data users tends to focus on building the knowledge of the various user segments on the statistical products that are more relevant to their needs. For advanced data users who are already skilled in quantitative analysis and modelling (e.g. researchers), training focuses on promoting and facilitating access to micro-level data assets. To this end, in October 2020 FAO conducted a webinar targeting research centers and academia to promote its Food and Agriculture Microdata Catalogue (FAM) and train participants on how to use it. Launched in 2019, the FAM now has an inventory of over 950 micro datasets, collected through farm and household surveys, which contain information related to agriculture, food security, and nutrition.

Figure 9.

Distribution of FAO SDG-indicator e-course learners by Region.

This webinar significantly increased the number of users requesting access to the FAM, as well as the number of papers produced based on FAM data. FAO also increasingly works with national statistical offices to build their own capacity to disseminate their micro-data assets and engage with advanced users to train them on using these data assets.

For more intermediated data users, who are generally more interested in accessing existing indicators, data visualizations, tables and statistics-derived analytical products, training is generally part of the capacity development activities aiming at support users in customizing their own tables or reports (e.g. policy or programme analysts, monitoring and evaluation specialists, data repackaging specialists). For example, all FAO SDG indicator e-learning courses have a component meant to train data users on interpreting the indicators and using them for decision-making.

Figure 10.

Distribution of FAO SDG-indicator e-course learners by Institutional Background.

In addition, all technical support activities provided to national statistical agencies on data production (e.g. conduct of agriculture surveys or censuses, food loss assessments, production of food security indicators…) now include a training component to assist statistical agencies in better communicating results and products to data users. In some cases, there may even be targeted training sessions with data users to discuss these products and how they can be used in decision-making process. Moreover, some training and capacity development activities also bring together users and data producers to train and support them on the development and dissemination of analytical reports (e.g. Voluntary National Reviews, National report of the state of food security…).

Finally, for more basic users who are only interested in the latest statistical results and analytical reports (e.g. media, general public), training activities focus on building the capacity of national statistical agencies in writing effective communication briefs or press-releases.

6.Conclusion

This paper has analyzed the changing context and nature of statistical training brought about by the combined effect of the expanded SDG indicator framework, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the cross-cutting impact of technological innovation. With reference to the experience of FAO as a custodian agency of 21 SDG indicators, we have highlighted the role of training within the FAO’s broader capacity development strategy, which aims to raise its impact in a sustainable way, implement the most advanced and up-to-date practices in the international development community, and adapt to the changing needs of countries. In particular, FAO has gradually shifted from providing ad-hoc training intervention to playing a facilitating role, enabling coordination and collaboration, connecting actors and stakeholders, supporting national processes, and also targeting functional capacities in addition to technical capacities, all to achieve longer-term impacts. In this perspective, training emerges as one of two key pillars of capacity development, along with technical assistance, with both pillars being complementary and mutually reinforcing. Training is especially important in the initial phases of a broader capacity development intervention, for getting participants up to a basic level of understanding, whereas technical assistance is more effective at later stages in order to trouble-shoot specific issues. This is corroborated by the 2019 FAO Statistical Capacity Assessment, which gathered a high proportion of assistance requests on aspects and phases of the data production cycle that are best served by training, such as on the methodology for compiling the indicators as well as on the analysis and interpretation of the indicators.

In an effort to broaden training in food and agriculture statistics, FAO actively collaborates with Regional Statistical Training Institutes, participates in the Global Network of Institutions for Statistical Training (GIST), and facilitates the mainstreaming of food and agricultural statistical training in academic programmes. FAO has jointly organized a series of training initiatives in collaboration with Regional Statistical Training Institutes in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, which have served to address many of new training needs triggered by the adoption of the SDG indicator framework. FAO is also implementing the Global Network of Institutions for Statistical Training’s (GIST) key recommendations about maximizing the impact of training for National Statistical Offices, such as designing trainings that also target managers and decision-makers; shifting to online training and making optimal usage of all available online tools; carefully identifying training needs and the right persons to receive training; and more comprehensively evaluating the impact of training. A number of these principles already underpinned the training plan of the FAO’s Global Strategy to Improve Agricultural and Rural Statistics, which worked with regional statistical training institutions to develop a university curriculum in agriculture and rural statistics and implement a scholarship programme to sponsor the academic training of national staff. While all the above joint initiatives have yielded fruitful results, there is still scope for further collaboration in certain domains. For instance, joint capacity assessments among international organizations could dramatically reduce duplication of efforts and country response burden, considering that a large share of information is commonly used by virtually all agencies.

While the SDGs already presented an enormous challenge for National Statistical Systems, the COVID-19 pandemic put a spanner in the works of many statistical processes, including capacity development activities. Social distancing measures and lockdowns disrupted data production at country level and most statistical capacity development programs in support of SDG measurement led by UN Agencies, at exactly the moment that the outbreak triggered a host of new data demands and priorities. FAO responded to this new landscape by quickly switching to virtual training modalities, through which it has managed to keep up the momentum of increasing the average country reporting rate on the SDG indicators under its custodianship, while also conducting rapid assessments of food insecurity in order to evaluate the impact of the COVID outbreak on food access.

A specific training tool whose value has soared in this context is the e-learning course, which is easily integrated with other training modalities and can thus respond to the specific learning needs and maximize the impact of training initiatives. The varied geographical and institutional origin of learners, described in section IV, attests not only to the ability of FAO’s SDG indicator e-learning courses to reach a broad audience, but also to the wider appeal of the courses well beyond their primary intended target group of government officials. Regardless of the particular tool selected, however, the key principles and good practices that should always underpin trainings, should be to: tailor the intervention to country-specific needs; correctly timing the intervention with respect to the issue to be addressed, and target both managers and the technical officers that deal with the particular domain on a day-to-day basis. In addition, training should not be provided only - to data producers; a series of recent initiatives by FAO also demonstrate the value of developing trainings targeted to different profiles of users of statistics.

Paradoxically, the COVID-19 pandemic has also served to highlight, with even greater urgency, the new data-related skills needed by contemporary statisticians, and therefore the types of training that could be most appropriate for acquiring these skills. The traditional educational background of professional statisticians needs to include training on Big data, integration of different data sources, geospatial information and the application of new technologies, effectively bringing the statistician closer to the profile of the data scientist. To this end, the FAO newly established Data Lab for Statistical Innovation aims to strengthen the capacity of the Organization to produce and analyse real time information from new data sources, fill data gaps and validate available data at country-level with alternative data sources, including Earth Observation data. It also aims to provide guidance and support to countries in order to collect nationally-representative information using official data sources, but adopting new data collection tools.

Notes

2 In the context of limited “in situ” data, as is often the case in many developing countries (and now even more frequent in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak), supervised approaches are hardly applicable. In such context, unsupervised approaches are more appropriate as they require far less “in situ” data, while they need a large volume of unlabelled training data (historical time series) for class identification and data validation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank FAO’s SDG indicator focal points, statisticians, data scientists and capacity development officers for their continued efforts at improving FAO’s support to countries.

Supplementary data

The supplementary files are available to download from http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/SJI-210853.

References

[1] | FAO. Corporate Strategy On Capacity Development. 2010. http://www.fao.org/capacity-development/our-vision/en/. |

[2] | OECD. Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and Accra Agenda for Action. 2005-2008. https://issat.dcaf.ch/download/501/3145/The%20Paris%20Declaration%20on%20Aid%20Effectiveness%20and%20the%20Accra%20Agenda%20for%20Action.pdf. |

[3] | FAO. Enhancing FAO’s Practices For Supporting Capacity Development Of Member Countries Learning Module 1. 2010. http://www.fao.org/3/i1998e/i1998e.pdf. |

[4] | FAO, World Bank and UN Statistics Division. Action Plan of the Global Strategy to improve agricultural and rural statistics - For Food Security, Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development. Rome; 2012. |

[5] | FAO. Evaluation of the Global Strategy to Improve Agricultural and Rural Statistics (GSARS). Rome; 2019. Accessible at www.fao.org/evaluation). |

[6] | |

[7] | Global Network of Institutions for Statistical Training (GIST). Sustainable statistical training programs at National Statistical Offices. 2020. https://unstats.un.org/gist/resources/documents/. |

[8] | KirkpatrickDL., Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels, Berrett-Koehler, 1994. |

[9] | Global Network of Institutes for Statistical Training (GIST). An introduction to evaluation of statistical training courses. 2021. https://unstats.un.org/gist/resources/documents/. |

[10] | See for instance MacFeely S, The 2030 Agenda: An Unprecedented Statistical Challenge. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Global Policy and Development. 2018. |

[11] | Tier Classification for Global SDG Indicators (as of 10 November 2016), accessible on the IAEG-SDG webpage here: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/meetings/iaeg-sdgs-meeting-04/. |

[12] | E/2020/24*-E/CN.3/2020/37*Economic and Social Council, Official Records, 2020, Supplement No. 4, Statistical Commission Report on the fifty-first session (3–6 March 2020) https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/2020-comp-rev/. |

[13] | See Gennari P and Navarro DK. Validation of methods and data for SDG indicators? Statistical Journal of the IAOS (2019) ; 35: ; 735-741, 735. |

[14] | Source: DESA SDG database, DCO visualization. |

[15] | CCSA and Paris21 Impact Survey, Survey on the impact of COVID-19 on CCSA members October 2020 Key facts & analysis Final report. |

[16] | UNSD and World Bank, “Monitoring the state of statistical operations under the COVID-19 Pandemic”, 5 June 2020, https://covid-19-response.unstatshub.org/survey/covid-19-nso-survey-report-1.pdf; the second and third assessment took place in August and December 2020: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/covid19-response/covid19-nso-survey-report-2.pdf;https://unstats.un.org/unsd/covid19-response/covid19-nso-survey-report-3.pdf. |

[17] | Cafiero C, Kepple A, Ballard T. The Food Insecurity Experience Scale Development of a Global Standard for Monitoring Hunger Worldwide. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, (2013) . |

[18] | FAO-EOSTAT: EO data for Official Agricultural Statistics, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/3004c4ffd8fa4d11870863106b024d6b. |