Boundaries and coordination of the National Statistical System (NSS)

Abstract

The production and dissemination of Official Statistics on a national level involves besides the National Statistical Institutes sometimes numerous institutional actors. International references such as the European Statistics Code of Practice, ESCoP, or the United Nations Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, UNFPoS, are organisational frameworks that aim at clarifying and facilitating to clarify and facilitate coordination amongst different producers of data and statistics. However, since the organisation of National Statistical Systems (NSS) varies considerably between the poles of centralisation and decentralisation, the different roles of data producers and various producers of Official Statistics, as well as the coordination of collaboration, is often far from being unambiguously understood. This paper is based on a presentation given at a session (IPS-071) jointly organised by the Statistical Office of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) at the 62

1.Introduction: What is the National Statistical System and why do we need it?

In modern societies, statistical information seems to be available in abundance, at any time, almost everywhere and on any topic. The popular production of statistics by whichever actor or institution and its spread has to be distinguished from the production and dissemination of “Official Statistics”, which is the result of coordinated actions of administrative bodies in line with standardised methodologies in order to ensure the highest possible degrees of comparability and quality. The National Statistical System embraces all such administrative bodies; it is an organised approach to the provision of high quality data and statistics, which provides the basis for reliable and comparable information. Within this system, the respective roles and responsibilities are clearly and transparently assigned and the coordination is an ongoing endeavour in which the members of the NSS are engaged in order to ensure relevant Official Statistics of high quality.

The objective of Official Statistics is to serve political decision makers, as well as the broader society, by providing impartial information about societal developments and phenomena as well as to monitor performance of political and/or economic actions:

“Almost every country in the world has one or more government agencies (usually national institutes) that supply decision-makers and other users including the general public and the research community with a continuing flow of information (…). This bulk of data is usually called official statistics. Official statistics should be objective and easily accessible and produced on a continuing basis so that measurement of change is possible” [1].

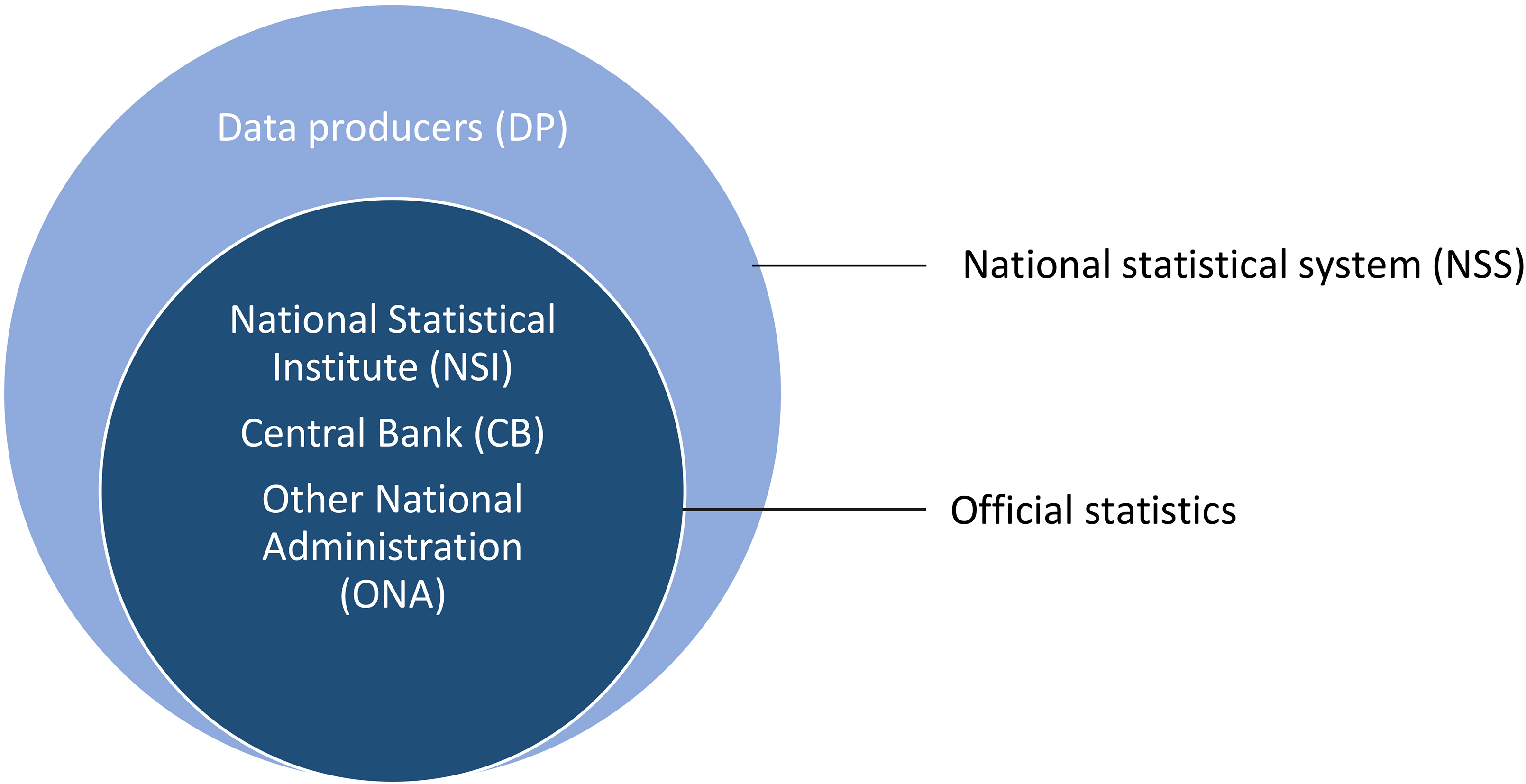

Figure 1.

Boundaries of the National Statistical System (NSS) and Official Statistics.

In most countries, National Statistical Institutes (NSIs) produce Official Statistics by either collecting data through various means (e.g. surveys or registers), or using data collected for all kind of purposes by other data producers. This work is often complemented through statistics produced by “Other National Administrations or Authorities” (ONAs), like Central Banks (CBs), Ministries and Agencies. Although Central Banks could be seen as an ONA in the National Statistical System, we will treat them here as an entity apart, which is mainly the result of their often somewhat different role in the context of the coordination of the NSS.

In the perspective proposed here, all producers of Official Statistics – NSIs, CBs and ONAs – as well as data producers (DPs) that deliver data which will be further processed by producers of Official Statistics are parts of the National Statistical System. The degree to which the above mentioned reference frameworks like the ESCoP or the FPoS are also to be applied to DPs might differ between countries. However, these frameworks remain the main reference for producers of Official Statistics.

Although Data providers deliver input for the production of Official Statistics, they are not to be considered themselves producers of Official Statistics.

Typically, all producers of Official Statistics in the NSS do so by referring to standardised methodologies and nomenclatures while adhering to clearly defined quality standards.

The NSIs not only play a central role in implementing such standards for themselves. They are also supposed to monitor and follow-up on the implementation of these standards by other producers of Official Statistics and data producers according to the ESCoP. The obligations and rights of NSIs are usually defined by some kind of Generic Statistical Law on Statistics (e.g. UN GLOS, [2]). The Statistical Law provides amongst other things also the legal basis for collection of data by various means (including microdata access to other administrative data holders), as well as the mandate to produce Official Statistics in line with the ESCoP or the UNFPoS.

As mentioned before, a somewhat special situation arises often with National Central Banks since legal provisions often prevent any “outside” coordination of the statistics produced; we will come back to this point in a dedicated paragraph further down.

The European Code of Practice, ESCoP [3], as well as the UN Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, UNFPoS [4], are the entities that define criteria under which producers of Official Statistics collect data, produce statistics on various topics and disseminate results, while keeping up to the highest quality standards. Both international reference documents stress the importance of coordination of the different actors that make up the National Statistical System (NSS).

The European Statistical System (ESS), consisting of the National Statistical Institutes of the European Union (EU) as well as of the Member States of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and Eurostat, strengthened (especially in the revised version of the ESCoP from 2017) the aspects of quality, coordination and cooperation in the NSS. Principle 1bis.1 clearly points out the coordinating role of the NSIs:

“The National Statistical Institutes coordinate the statistical activities of all other national authorities that develop, produce and disseminate European statistics” [3].

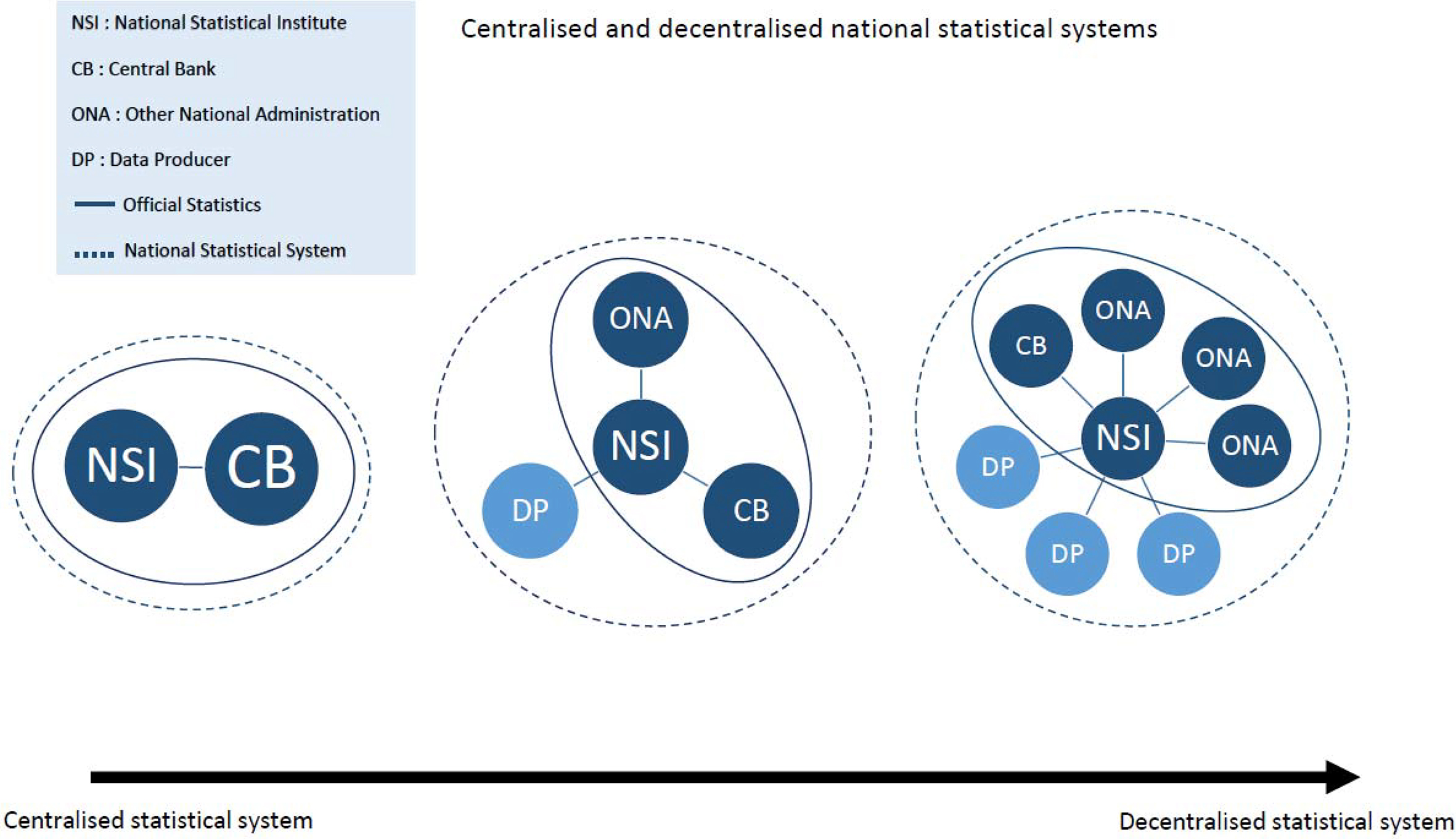

Figure 2.

Continuum of the NSS from centralised to decentralised.

Furthermore, the “Quality Assurance Framework (QAF) defines concrete quality standards for statistical processes and outputs which are covered by principles 7 to 15 of the European Statistics Code of Practice and can be seen as an additional measure for building trust in Official Statistics. The adherence to these quality criteria is also object to regular reporting within the ESS.11

In a similar vein, the UNFPoS stipulate under point 2. of the chapter “Legislation” activities and responsibilities of the national statistical office:

“The coordination of statistical activities across government (and, for countries with federal systems, with state/provincial governments), including the roles and responsibilities of other agencies” [4].

Hence, the institutionalisation of a National Statistical System, which specifies clearly its members, as well as the producers of Official Statistics is a precondition for its organisation and coordination. It ensures the assignment of tasks to its members and their compliance with national and international methodologies and nomenclatures in the production of data and/or Official Statistics with the NSI as a coordinator. In this way the NSS also contributes to avoiding duplication of efforts, as well as undue burdening of respondents, while establishing agreements about efficient and effective data collection, including the use of non-statistical government data files. The creation of a NSS in which the outcomes of various data collections are comparable or can at least meaningfully be related to each other based on harmonised concepts, definitions, classifications and sampling frames builds the basis for trusted statistical production.

The National Statistical Institutes exercise a coordination and control function as concerns the quality of processes and the use of concepts and methodologies while regularly issuing transparent reporting on the compliance with agreed standards of all actors involved. NSIs and Central Banks (CBs) coordinate those parts of statistical production that are to be considered Official Statistics in mutual accordance. It is also up to the NSI to designate who else is to be considered a producer of Official Statistics while keeping-up with the quality criteria defined. This “branding” is also a basic ingredient in creating and maintaining wide spread trust in Official Statistics and will be addressed further down.

2.Centralised vs. decentralised National Statistical Systems

The way in which a NSS is concretely organised varies with the number of other national producers/authorities in the field of statistics.

We might distinguish in this regard more “centralised” National Statistical Systems, with only one or few entities being responsible for the production of Official Statistics in a country on one side and more “decentralised” NSS with numerous ONAs accompanying the work of the National Statistical Institutes on the other side of this continuum.

Whether a country has a more centralised or a more decentralised NSS depends at least partially also on its political, administrative, social and spatial/territorial organisation – federal states like the USA, Germany or Switzerland tend to have more ONAs than more centralised countries like France, Sweden or China.

In a centralised NSS, the NSI (and the CB) are exclusive producers of Official Statistics that collect and process data and disseminate the statistical results. Some of the advantages of a centralised National Statistical System are:

• The concentration of expertise;

• User’s perception of the NSI as a “brand” for Official Statistics;

• The less problematic coordination and enforcement of quality and standards in statistical production and dissemination within the NSI.

Disadvantages of a centralised system might occur with regard to:

• The availability of non in-house expertise;

• The distance to (regional) users.

Decentralisation of a NSS might occur as “territorial” decentralisation or as “functional” decentralisation.22 In a territorial decentralised NSS the production of Official Statistics from data collection to dissemination is often done by regional entities, while in a functionally decentralised NSS production of Official Statistics is often done by Ministries or other specialised agencies.

Clearly, the more decentralised a NSS, the more demanding becomes the task of coordinating all the actors and the more important becomes the “branding” of Official Statistics as a means for the NSI to exercise its responsibility when it comes to keeping-up with international standards and to ensure the requested quality.

Hence, some of the positive aspects of a decentralised NSS are:

• Ministries/ONAs maintain functions of a producer of Official Statistics in absence of respective capacities/competencies at the NSI

• Closer to users of Official Statistics

Disadvantages of decentralisation of which some were already mentioned are:

• Difficulties in maintaining effective planning and coordination across the NSS

• Often significant involvement of ONAs (Ministries, etc.) which might open the door for political influences in the coordination of the NSS

• Difficulty in communicating and implementing common standards, methodologies and practices.

As should have become clearer by now, there is no one “recipe” when it comes to the organisation of a National Statistical System and the concrete national situations may vary considerably. However, the endeavour of maintaining a well-coordinated system that produces high quality and comparable statistical outputs is a common objective.

3.Trust in Official Statistics and the importance of “branding”

The perception and the diffusion of statistical figures and analysis presumes that the obtained information is trustworthy. There are some empirical indications that the idea behind the concept of Official Statistics is easier to transmit in centralised systems:

“(…) during the cognitive testing it became clear that at least in the United States the concept of “official statistics” was not clearly understood by respondents – something that was not observed in countries with more centralised statistical systems” [7].

NSIs and international organisations have repeatedly conducted surveys in order to measure trust in Official Statistics (e.g. [8]).

Clearly, in order to be perceived as impartial providers of relevant and qualitatively high-standard information, all producers of Official Statistics need to be distinguished from other sources of information. This is where “branding” becomes important. It is not only about accomplishing the use of official information against lower quality information or even disinformation; it is also about being perceived as the major provider of information for concrete problems and needs. In its third edition the UN Handbook of Statistical Organisation [9] states that:

“Recognizing quality in statistics and using them with trust are closely associated with the recognition of the agency that has compiled them. The wider the agency’s recognition, the greater the acceptance of the information because of the element of trust. However, to gain the widest possible recognition, the statistical agency must be visible, and its visibility increases if it stands on its own as part of the central Government.”33

Hence, the brand of an NSI or ONA as a representative or a part of Official Statistics is an important source of identification for users. The establishment and consequent use of a dedicated registered logo eases the recognition of Official Statistics and should be considered an accompanying measure in all statistical dissemination.

4.Central Banks in the National Statistical System

Another important point that needs to be addressed here refers to the special role of Central Banks (CB) in the National Statistical System. Central Banks are in most countries relevant producers of Official Statistics as well as data providers and users of Official Statistics. No matter if a NSS is centralised or decentralised, in many countries Balance of Payments (BoP) are produced by the respective Central Banks although in some cases the NSI and the CB jointly compile BoP. In other cases the NSI also compiles BoP while receiving data from the CB. As these examples show, the production of National Account statistics relies, often heavily, if not exclusively, on Central Bank figures on money, banking and financial markets. As already mentioned before, one of the problems when it comes to the cooperation between NSIs as the central coordinators of the NSS and CBs comes from the fact that the latter are often by law obliged to exclude any external influence. In the European Union for example, the independence principle of the European Central Bank (ECB) and the national Central Banks is fixed through article 108 of the Treaty establishing the European Community [10]:

“Neither the ECB, nor a national Central Bank (…) shall seek or take instructions from Community institutions or bodies, from any government of a Member State or from any other body”.

However, since there are often corresponding needs for statistics as concerns the monitoring of the efficiency of political and economic measures, it is imperative to ensure consistency amongst figures also with regard to the System of Accounts (e.g. SNA 2008/ESA 2010) which calls for cooperation between NSIs and the statistical units of CBs. As concerns balance of payment statistics within the EU, the responsibility for the production of BoP is therefore shared between the ECB and the European Commission (Eurostat). The respective division of tasks and responsibilities is fixed through a Memorandum of Understanding [11] between both administrative bodies. As is specified by an earlier version of this MoU which is also still valid [12]:

“Responsibility means the right and obligation to take the initiative in advancing the development of economic and financial statistics; in instigating and carrying through the necessary legal measures; in ensuring that data are collected and processed; in acting as the prime source of publication, and disseminating data accordingly; and in keeping the data relevant to user needs and economic and financial conditions.”

Although the coordination of statistical production between administrative bodies on the European level is strictly speaking not identical to the one on the NSS level, the above example of the MoU between Eurostat and the European Central Bank is a good example of how the coordination within the NSS can be arranged between administrative bodies that are by law supposed to be “independent” producers of Official Statistics.

5.Conclusions

There is generally a broad agreement amongst producers of Official Statistics that the National Statistical Institutes are in the key role of coordinating the National Statistical System in order to ensure the common use of methodologies and quality standards. Data providers are part of the NSS and are thus also coordinated by the NSI, but they are not to be considered producers of Official Statistics themselves. Centralisation and decentralisation are important characteristics in the organisation of the NSS that have to be recognised.

In order to distinguish Official Statistics from other commercial or private producers of statistics, the use of a brand “Official Statistics” with a dedicated logo (preferably of the NSI) should be used. This is especially beneficial in more decentralised NSSs since it eases the recognition of Official Statistics for the users.

Central Banks or their statistical units often play a central role in the compilation of financial, monetary and banking statistics. Since they are frequently obliged to keep up with principles of independence the coordination with other producers of Official Statistics such as the NSIs has to be arranged through dedicated memoranda or similar provisions.

Notes

1 In order to also ensure the political backup needed for producers of Official Statistics especially with regard to impartiality, the European Commission introduced the concept of “Commitment on Confidentiality”: “The Commitments were intended as a means to involve national governments in responsibility for the level of a country’s compliance with the European Statistics Code of Practice, thus establishing a link between the Code and governments that was previously missing” (Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council; COM (2018) 516 final, [5, p. 2]).

2 See also de Vries [6] on the distinction of “Territorial decentralisation” and “Functional or sectoral decentralized systems”.

3 An updated version of the UN Handbook of Statistical Organisation with support from EFTA is currently under preparation (state: spring 2020).

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Mr. Lars Svennebye, Mr. Christian Stadler and Mr. Steven Vale for critical comments on an earlier version of this paper and Ms. Ella Brown for proof reading.

References

[1] | Biemer, P. and Lyberg, L., Introduction to Survey Quality, Wiley, (2003) . |

[2] | United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Generic Law on Official Statistics for Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia; New York: United Nations, (2016) . |

[3] | European Commission; European Statistics Code of Practice, (2017) . Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/quality/european-statistics-code-of-practice. |

[4] | United Nations Statistical Division, UN Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, (2015) . Available from: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/dnss/gp/Implementation_Guidelines_FINAL_without_edit.pdf. |

[5] | Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council; COM (2018) 516 final, (2018) . |

[6] | De Vries, W.F.M., The Organization of Official Statistics in Europe, UNSD, (2014) . Available from: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/dnss/docViewer.aspx?docID=125#start. |

[7] | OECD, Measuring Trust in Official Statistics. Cognitive Testing, (2011) , 4–5. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/sdd/50027008.pdf. |

[8] | Alldritt, R. and Wilcock, J., Why measure trust in Official Statistics?; paper presented at 58 |

[9] | United Nations Statistical Division, Handbook of Statistical Organization, Third Edition; New York: UN (2003) , 17. Available from: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/SeriesF/SeriesF_88E.pdf. |

[10] | European Union, Treaty on European Union and of the Treaty Establishing the European Community, (2002) . Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12002E/TXT&from=EN. |

[11] | Eurostat/European Central Bank, Memorandum of Understanding between Eurostat and the European Central Bank/Directorate General Statistics on the quality assurance of statistics underlying the Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure, (2016) . Available from: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/legal/pdf/en_mou_between_the_ecb_and_eurostat_2016_f_sign.pdf. |

[12] | Eurostat/European Central Bank, Memorandum of Understanding on Economic and Financial Statistics, (2003) . Available from: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/legal/pdf/en_mou_with_eurostat1.pdf. |