Counting Indigenous American Indians and Alaska Natives in the US census

Abstract

US census data on Indigenous American Indians have progressed from no data at all to very poor and inconsistent data to smaller (but still significant) undercounts on Indigenous lands. The first US census, conducted in 1790, explicitly excluded American Indians from being counted, in accordance with the US Constitution. Much has changed. As the U.S. gears up for the 24

1.Overview

This paper describes the experience of Indigenous people in a national census, specifically American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN). The United States (US) has the longest continuous census in the world [1]. In 1790, the first US census explicitly excluded American Indians from being counted as part of the population, in accordance with the US Constitution [2]. Since a primary purpose of the census was to determine representation in the US House of Representatives in Congress, this exclusion meant that American Indians were not only uncounted, but unrepresented. Instead, American Indians were seen as citizens of their respective sovereign Tribes.

Much has improved. As the US gears up for the 24

The US census has become the primary source of data on AIAN people, as well as the basis of funding for many Tribal programs and policies [4, 5]. Census data are assumed to measure actual population change. Changes in questions and methods have an impact, but US census data are viewed as resilient. However, the US census is conducted only once a decade. Undercounts, particularly on reservations and other Tribal lands, result in loss of funds for some of the poorest Americans. These undercounts remain until the next census is conducted ten years later. In modern times, most Americans received census forms in the mail. Causes of AIAN undercounts include the lack of mailing addresses on reservations and remote rural locations. Since the census is conducted once each decade, undercounts have a long-lasting impact. In 2020, for the first time, most Americans will answer the census on-line. This is anticipated to be an issue on reservations, where internet access is much less than the rest of the country [6]. The Tribes, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), which represents federally-recognized Tribes and other American Indian groups have worked with the US Census Bureau to raise participation rates and improve results. There is much to learn from these joint efforts, which may improve participation and reliability in counting Indigenous populations world-wide.

2.Indigenous people throughout the world

Altogether, there are over 300 million Indigenous people in the world. Many countries have Indigenous populations, but data are scarce [7]. Whereas Indigenous populations vary widely in where they live, there are similarities across countries. Typically, Indigenous people tend to be the original inhabitants of their respective countries, have a small share of the total population, reside in remote areas and have different cultures and languages. Data on Indigenous people are hard to obtain, as national population surveys and studies often do not have large enough samples to disaggregate and provide separate reliable estimates. Thus, Indigenous people are often invisible in population studies in their own countries, making it difficult or impossible to address their issues. This is critical as Indigenous peoples tend to be less well-off economically and to have poorer health [7].

National censuses throughout the world have an essential role to provide data on Indigenous people. Since censuses count everyone within their borders, small Indigenous population and sample sizes are much less of an issue in obtaining reliable estimates.

3.Indigenous people in the US

This article describes the experience of two Indigenous groups – American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN) – in the US census, history, how it is conducted, how it is used and what is anticipated for the 2020 census. The United States has four major Indigenous population groups: American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders (i.e. Guam, American Samoa, Marshall Islands). According to the last census, conducted in 2010, out of nearly 310 million residents, 5.3 million (1.6 percent) reported their race was AIAN, either solely or in conjunction with another race. About 2.9 million (0.9 percent) reported AIAN as their only race. About 1 million reported their race as Native Hawaiian (with or without another race) or Other Pacific Islander. This paper does not cover the Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander populations, because their history and legal status are so different from the AIAN peoples [7].

American Indians are the original Indigenous inhabitants of the continental US, having lived there for many thousands of years. The continental United States consist of 48 States, excluding Alaska and Hawaii. Alaska Natives include certain American Indian Tribes, Eskimos and Aleuts (from the Aleutian Islands). The AIAN population consists of 574 federally-recognized Tribes and about 60 state-recognized Tribes. Federal recognition came mainly from treaties between Tribes and the US government, although some have been recognized through Executive Orders from the President, judicial action or legislation to be federally-recognize [8]. On December 20, 2019, the Little Shell Tribe of Montana became the latest Tribe to achieve federal-recognition after more than 100 years of negotiation [9]. Federal legislation, policy and programs overwhelmingly cover commonly members of federally-recognized Tribes. Membership is determined by criteria set by each Tribe, often those possessing one-quarter or more ancestry (blood quantum).

Federally-recognized Tribes are sovereign nations with their own governments (e.g. Tribal councils) and boundaries with distinct cultures, histories and (often) languages. Tribal lands include reservations, pueblos, colonies, Rancherias and villages (in Alaska), but are often referred to collectively as reservations. Altogether, Tribal lands are often referred to as Indian Country [8].

The AIAN people are also referred to as Native Americans, particularly by non-AIAN people.

4.Historical overview

Censuses, which count entire populations have been conducted for thousands of years. It will probably never be known which census is the oldest. One of the earliest censuses, according to the Population Research Bureau, was an agricultural census undertaken nearly 6,000 years ago in Babylon. The oldest surviving population census was collected by the Han Dynasty in the year 2 CE [10]. In what is now the United States, some Tribes conducted their own censuses prior to American settlement, often through oral histories and paintings on buffalo hides [8].

While the US Census is not the oldest census, it is noteworthy for many reasons and much more than a population count. The purpose of the census, in the Constitutional mandate, is to draw districts within States for which members of the House of Representatives in Congress, can be elected. The US became the first nation to use a census “…to apportion political representation” [1]. Over time, the purposes of the census were expanded. Legislation was written to allocate funding for policy initiatives and program funding on the basis of census population counts in jurisdictions (i.e. state, counties, metropolitan areas and Tribes). Finally, the decennial census has been and continues to be used for scientific research and population trends.

The first mention of American Indians in the U.S. Constitution is the exclusion of American Indians, because, as Tribal members, they were not considered Americans and not taxed [2].

“…Representatives…according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three-fifths of all other Persons.”

This exclusionary language concerned two aspects of how American Indians lived in the first 100 to 150 years of American history: citizenship and residence on tribal lands. American Indians were excluded from the census, since, as non-citizens, they could not be represented in Congress. American Indians were considered citizens of their Tribes, but not American citizens. The phrase “Indians not taxed” was shorthand for the vast majority who lived with their Tribes on Indian lands. Over the decades, this meant American Indians who lived on reservations. The effects of non-citizenship and residence on Tribal lands directly impacted if and how the census was conducted until modern times.

Table 1

US Census counts of American Indians/Alaska Natives

| Year | Number (AIAN only race) | Number (AIAN and other races) | Total AIAN only race and with other races |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 237,196 (0.4%) | – | 0.4% |

| 1920 | 244,400 (0.2%) | – | 0.2% |

| 1930 | 334,000 (0.3%) | – | 0.3% |

| 1940 | 343,400 (0.2%) | – | 0.2% |

| 1950 | 508,700 (0.3%) | – | 0.3% |

| 1960 (with Alaska) | 551,700 (0.3%) | – | 0.3% |

| 1970 | 827,300 (0.4%) | – | 0.4% |

| 1980 | 1,420,400 (0.6%) | – | 0.6% |

| 1990 | 1,929,200 (0.8%) | – | 0.8% |

| 2000* | 2,447,989 (0.9%) | 1,643,345 (0.6%) | 4,119,301 (1.5%) |

| 2010* | 2,932,248(0.9%) | 2,288,331 (0.7%) | 5,220,579 (1.7%) |

The US census has been gathering data every ten years from 1790 to 2020. As such, it is often referred to as the decennial census. During the early decades, census data was collected by US Marshalls going door to door, often on horseback. Table 1 contains census counts of the AIAN people [8]. As can be seen, census counts began not in 1790, but a century later in 1890. What little we know before 1890 for the vast majority who lived on Tribal lands is from a few Tribal censuses, such as the Cherokee census of 1835. During this period, very few American Indians had left their Tribes and assimilated into the general American population. They were counted in the censuses, but there was no way to separately identify them, because the only racial categories were White, Black and Mulatto [8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15].

Until 1887 (three years before the 1890 Census), American Indians had lost almost all of their lands, due to removal, war and treaties with Tribes. Tribal members were confined to reservations, administered by Indian Agents from the Department of War. Tribal members could not leave their reservations without written permission from an Indian Agent. Indian Agents also counted American Indians for the decennial censuses. There were no uniform criteria, but there were census schedules, intended to obtain degrees of assimilation. Such data included degree of Indian blood, Tribe, traditional dress, place of residence, polygamy and language. Indian Agents continued to provide census and annual planning data until around 1930 [13].

Indian Agents faced operational statistical difficulties. The term “Indians not taxed” was especially problematic. In 1870, even the Superintendent of the Census, Francis Walker, was baffled. For example, by 1870, while the vast majority of American Indians lived on Tribal lands, there was intermarriage. What did it mean when a Tribal member was of mixed-race parentage? How were Whites counted if they lived on reservations? How were American Indians in Tribes counted if they lived adjacent to (but not on reservations)? Was there double counting? Were people excluded? No neat solutions were forthcoming, so discretion was given to the Indian Agents [1].

While many statistical issues arose when Indian Agents collected population data, one thing was clear. The population of American Indians had dropped precipitately to less than 240,000 people, as shown in Table 1. Although the original Indigenous population of the continental United States is not known, estimates range from four to twelve million [1, 8].

US Marshalls collected census data from 1790 to 1870, but as the population grew, the Census Bureau trained special workers, known as census workers or enumerators, to gather data from 1880 to 1950. Enumerators, like the US Marshalls before them, went from house to house. Race was recorded by observation [1, 12, 13]. On reservations and other Indian lands, Indian Agents continued to collect data until about 1930 [1, 12, 13].

In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act was enacted. This gave American Indians citizenship and the right to vote. American Indians remained members (i.e. citizens) of their respective Tribes. It is important to note that, while many American Indians got the right to vote in 1924, that full voting did not occur until the 1970’s, as a result of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964/5 [8].

The 1930 census was the first one after the Indian Citizenship Act. Indian Agents were asked to count Tribal members not only on, but off reservations [12]. A major change was made to how American Indians were viewed. Descriptions went from “Indians in the United States…” to “Indians of the United States” [1]. This change in law and tone resulted in census enumerators (not Indian Agents) performing census counts. In 1940, the phrase “Indians not taxed” was struck down in federal court, removing the final barrier to counting American Indians in the census on their own behalf [17].

5.1960 census

The 1960 census was a landmark one throughout the entire country. The 1960 census was the first one after Alaska and Hawaii achieved statehood as the 49

For the first time, mail-in questionnaires were sent out, rather than door-to-door enumerators. Census enumerators continued to be used, but only in cases of hard to reach populations (such as remote reservations) and those who did not return their mail-in questionnaires. Race became self-reported, not recorded by census enumerators through observation [1]. Most AIAN people now lived outside Indian Country in cities, suburbs and rural areas.

The 1960 census highlighted an important distinction in how AIAN people were identified: a distinction that carries over to this day. The US government had transferred interactions with the Tribes from the Department of War to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), located in the Department of Interior. The BIA identified AIAN people as those who were members of federally-recognized Tribes. As described previously, the process of federal recognition has complicated legal and historical connotations. The census (also a part of the government) identified racial categories in a broader demographic fashion based on the continent of origin. Specifically, AIAN was defined as those “…having origins in the original peoples of North America, and who maintain cultural identification through tribal affiliation or community recognition” [19].

6.1970 to 2010 censuses

Space was provided on the 1970 census for those who identified as AIAN to write in their Tribe. The 1970 census was the first one to provide separate estimates of American Indians on each of the reservations [Tribal] Directive 15 of 1977, which contained uniform racial criteria across the census and other federal surveys [19].

In 1980, a special supplement was added on to reservation and other Tribal lands to find out more detail about the lives of AIAN people. The questionnaire was tailored to be more appropriate for this population. For example, sheep herders and rug weavers were added to the list of occupations [20].

OMB Directive 15 was expanded for the category AIAN to include Indigenous people from the continent of South America and specifically mentioning Central America. This allowed Indigenous people from North and South America (but not originally from the United States) to identify as American Indians. Many of these respondents could be ascertained by the Tribe they wrote on the census [19].

Starting in 1980, there were and continue to be joint efforts on the part of the Census Bureau, Tribes and groups, notably the NCAI to increase AIAN participation, particularly those residing on reservations and other Tribal lands [4, 21]. The census is the only effort large enough to include all AIAN people. National population surveys do not have samples large enough to adequately provide separate reliable estimates on a year to year basis. Dress rehearsals of census procedures were held on reservations prior to the 1990 and 2000 censuses, while cognitive studies and focus groups on reservations were held for the 2010 and 2020 censuses. Local American Indians and Alaska Natives were recruited to be census enumerators on their reservations and Tribal lands. This helped with participation rates, finding remote dwellings and providing language skills [4]. In addition, extensive public relations campaigns were launched. These included posters, radio ads and art contests.

Despite efforts, there were undercounts on reservations. Undercounts of those who lived on or near reservations was calculated by the Census Bureau to be 12.2 percent in 1990 and 4.9 percent in 2010. Although this was an improvement, it was the highest undercount rate in the country [22]. The effects of these undercounts are estimated to be about $3,000 per person, while AIAN people have the highest poverty rates of any racial or ethnic group in the country at nearly 25 percent [22, 23].

The Census Bureau identifies those who live on or near reservations as hard to count. Causes of AIAN undercounts include the lack of mailing addresses on reservations and remote rural locations. Tribes rely on census counts to allocate program funding. During the 20

Reservations and other Indigenous lands are typically remote and rural. By 2010, most people who reported AIAN as their only race did not live on reservations or other American Indian lands. Specifically, almost one in three (32.9 percent) lived on reservations, other American Indian lands or Alaska Village areas [25].

Funding for many Tribal programs is dependent on census data and is written into legislation or regulations. These programs include Education Grants, Head Start (for preschoolers), Native American Employment and Training, the Indian Health Service (the primary source of health care on reservations), Medicaid (health care for people with disabilities or in poverty), Urban Indian Health Program, SNAP (vouchers for food to low-income families and individuals), Aging Programs, Indian Housing Block Grant, Indian Community Development Block Grant and Housing Choice Vouchers [26, 4]. In addition, adherence to the Voting Rights Act and the Equal Employment Opportunity Act are dependent on census data [4]. Besides programs, it is important to note that census data affects policy, markets, distribution chains and investment for the entire population, including AIAN people.

7.Multiple races in the 2000 and 2010 censuses

In 1960, 551,700 (0.3 percent) of the population identified themselves as AIAN. This number almost quadrupled by 1990 when nearly two million American identified themselves as AIAN. This growth was deemed demographically impossible and could not be explained by immigration of Indigenous people from Central and South America. Part of the increase was due to people who no longer had the stigma of reporting their race as AIAN and part was due to other Americans who believed they had some AIAN ancestry, whether or not they had proof. Thus, while reservations and other Tribal lands experienced undercounts, the population off the reservations seemed to experience overcounts [8].

Beginning in 2000, multiple races were allowed to be reported on the census. This had little effect on the numbers of larger racial groups, such as white, African-American and Asians. However, it had an outsize impact on the AIAN population due its small size. In 2000 as shown in Table 1, approximately 4.1 million people (1.5 percent) reported themselves as AIAN. However, of these, only 2.5 million (59.4 percent) reported AIAN as their only race, while the remaining 1.6 million (40.6 percent) reported AIAN along with another race. By 2010, 5.2 million people (1.7 percent) reported their race as AIAN, of which 56.2 percent reported AIAN as their only race. In 2010, of the nearly 2.3 million people who reported AIAN along with another race, the majority (62.6 percent) reported themselves as white and AIAN, followed by 11.8 percent who reported African-American along with AIAN. Characteristics for those who reported AIAN as their only race were different from those who reported multiple races, including AIAN. The BIA reported in 2010 that 1,969,167 people were enrolled members of federally-recognized Tribes: a figure closer to the number of the 2.3 million who reported AIAN as their only race than to the total of 5.2 million [8]. While no official preference is given to AIAN only versus AIAN with other races, most research is performed using the AIAN only population [8].

8.American community survey

The decennial census is considered a worthwhile, if not perfect, effort. Its main limitation is that it is conducted only once every decade. This is not likely to change as the mandate is written into the Constitution. Other countries, such as Australia and Canada, have censuses every five years or so. Besides differences in periodicity, there are differences in how undercounts are adjusted. For example, Australia used a Census Post-Enumeration Survey (PES) in 2011 and 2016 to rebase the Australian Estimated Resident Population. The PES is a valuable data source for small populations in Australia, although it brings its own flaws and limitations [27]. The US takes a somewhat different approach with its post enumeration census surveys. The purpose of PESs, called Census Coverage Measurement (CCM) in 2010, are intended to measure coverage errors overall and for subpopulations, such as AIAN living on reservations and other Indigenous lands. Results are used to improve the next census [28].

An attempt to gather data at the local level (i.e. states, counties, metropolitan areas and Tribes) was undertaken with the implementation of the American Community Survey (ACS). From 1940 to 2000, the Census Bureau collected data using a short form and a longer version (called the long form). The short form was used for redistricting and certain policy and research purposes, but the long form provided a richness of socio-demographic and economic data. The ACS is conducted continuously (not just every ten years) and is based on data from previous long forms. In this way, rich local data can be collected and analyzed every year, not just once a decade [8].

In the 2010 census, as well as the 2020 census, only the short form was used. The ACS samples are not as representative of AIAN remote communities as the decennial census. This is due to sampling concerns pertaining to remote reservations in smaller populated areas of the US. There is a discrepancy between total AIAN population counts from the census and those from ACS. In fact, ACS yearly estimates dropped after the 2010 census [29]. NCAI has recommended that population totals only be used from the decennial census. In 2010 and 2020, data on most socio-demographic and economic characteristics can only be obtained from the ACS. However, there is a note of caution. The NCAI recommends that percentages be used from the ACS, but not population figures derived from those percentages. For example, while the percentage of AIAN in poverty can be quoted from the ACS, it is not recommended that a total number of AIAN in poverty be derived and used [30].

9.2020 census

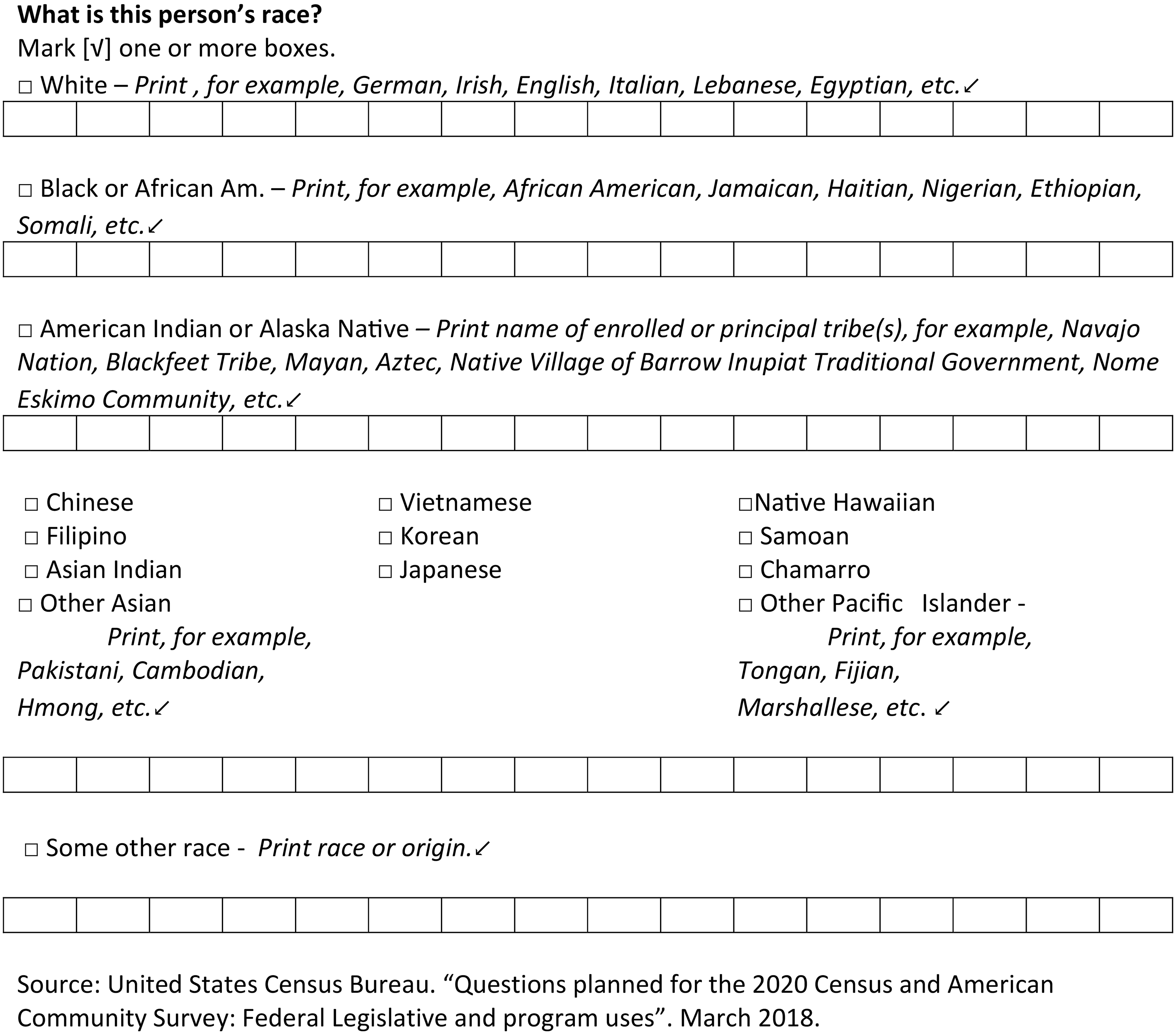

The 2020 race question appears in Fig. 1 [31]. The 2020 census will be the first to include the provision for respondents to answer on-line, as well as by mail or an enumerator. Since AIAN have much lower rates of broadband coverage and access to the Internet, this is expected to be a concern. The NCAI and the Census Bureau have been planning accordingly by outreach efforts and hiring AIAN enumerators, including those who speak AIAN languages [32, 33].

Figure 1.

2020 US Census race question.

As in earlier recent censuses, outreach efforts are being developed to include radio and television ads, posters, brochures and digital materials to target AIAN people and address their concerns. An example is shown below [34]:

2020 Census Snapshot for American Indian/Alaska Natives What is the census? Every 10 years, the United States counts everyone living in the country on April 1. Our tribes do not share enrollment numbers with the government, so it is important for all American Indians and Alaska Natives to participate in the 2020 Census. What’s in it for me? The 2020 Census is an opportunity to provide a better future for our communities and future generations. By participating in the 2020 Census, you help provide an accurate count of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Your responses to the 2020 Census can help shape how billions of dollars in federal funds are distributed each year for programs and grants in our communities. The 2020 Census is our count. Our responses matter. Regardless of age, nationality, ethnicity, or where we live, we all need to be counted. Responding to the 2020 Census is: Easy In early 2020, every household in the United States will receive a notice to complete the census online, by phone, or by mail. Safe Your responses to the 2020 Census are confidential and protected by law. Personal information is never shared with any other government agencies or law enforcement, including federal, local, and tribal authorities. Important The federal government and local American Indian and Alaska Native leaders and decision-makers will use 2020 Census data in a variety of ways that can benefit Native people and our communities. 2020 Census. Gov.

How AIAN people will be counted in the 2020 census depends on the overall census environment in the US. For the 2020 census overall, eight factors have been identified as overall data concerns in a challenging environment with escalating costs: (1) fiscal constraints, (2) rapidly changing use of technology, (3) information explosion, (4) distrust of government, (5) declining response rates, (6) increasingly diverse population, (7) informal complex living arrangements and (8) a more mobile population [35]. Each of these factors affect census data collection among AIAN, however distrust is arguably the most potent. Many government policies and exploitation by researchers has had negative effects for Tribes and AIAN people.

Deciding on standard census materials and methods is a complex and detailed process. The most salient influence on how a census should be conducted are its purposes, which are representation in congress and to get a complete count and basic description of US residents. Other factors, including stewardship of public funds, influence the planning process for each US census. Advocacy groups of various types often lobby to shape the US census. Elected officials represent their constituents in important ways. There are some groups that give voice about counting AIAN people in the census. Perhaps the most notable group is the NCAI. On January 9, 2020, the NCAI gave written testimony to the US House of Representatives Committee of Oversight and Reform in the Oversight Hearing on Reaching Hard-to-Count Communities in the 2020 census. This testimony formalized concerns about census methods impacting redistricting (i.e. boundaries for Congressional representatives) and voter registration, federal funding and local Tribal governance. The NCAI testimony detailed challenges in Indian Country and specified how census participation can improve to assure accuracy [36].

10.Research uses

The Census Bureau will release a report on AIAN people. Data dissemination efforts are being undertaken in conjunction with Tribes and the NCAI. The ACS will continue on-line profiles for individual reservations. In addition, the NCAI is committed not only to collecting data, but in using it for policy and program research to improve the lives of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Tribes are being encouraged in data dissemination and research. The right to be counted includes the right to tell their own stories in their own ways. There are many research efforts that have been or will be undertaken.

Examples from the NCAI include data books about reservations, online descriptions of reservations, analyses on Tribal justice, population trends, cancer registries, analyses from the Indian Health Service and local analyses by states [37, 4].

One of the most creative examples comes from the National Center for Health Statistics within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Center for Health Statistics plans to produce reliable and unbiased mortality estimates, including national life tables and life expectancy measures for the US American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) population. Previous estimates of AIAN mortality were judged to be inaccurate due to problems with race reporting on death records (conventional death rate measurement) or because of insufficient sample size in previous linkage studies (data from the National Longitudinal Mortality Study). The current project will link all AIAN respondents from the 2010 US Census (both those who self-identified as AIAN only or in combination with another race) to the National Death Index (NDI). Under this project, linkage of census records with the NDI will eliminate known racial deficiencies in AIAN death records; use of the entire AIAN population will ensure a sufficient number of deaths to produce reliable mortality measures. Current plans are to link the AIAN population from the 2010 Census to the NDI for one year of mortality follow-up [38].

11.Conclusions

American Indians have come a long way with respect to the American census. There was no virtually participation during the first 100 years, as American Indians were not considered citizens of the US. By 1890, counts of American Indians on reservations was made by Indian Agents, not American Indians themselves. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 was a pivotal event, because American Indians became citizens and had the right to be counted. Attempts to count the AIAN people has been a journey, where undercounts on Tribal lands have steadily decreased. Although there remains risk for systemic exclusion in the 21

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the co-chair, Dr. Sam Notzon, International Group for Indigenous Health Measurement, the Population and Housing Censuses editor and editor of this special edition Jean-Michel Durr for his interest and encouragement, as well as the current Editor-in-Chief Dr. Pieter Evaraers and General Editor, Dr. Kirsten West. This article would not be possible without the love and sacrifice of our ancestors. We dedicate this paper to them, as well as to American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States who continue to keep our culture alive. Of special note are those who left us far too early, especially Ari Gerzowski of the Blackfeet Tribe.

References

[1] | Jobe MM. Native Americans and the U.S. census: A brief historical survey. University Libraries Faculty and Staff, Contributions. University of Colorado, Boulder. Spring (2004) . |

[2] | The Constitution of the United States. Article 1, Section 2. (1789) . |

[3] | National Indian Council on Aging, News Blog. 2020 census especially important for tribes. https://www.nicoa.org/2020-census-especially-important-for-tribes/. |

[4] | US Census Bureau. Tribal consultation handbook: Background materials for Tribal consultation on the 2020 census. Economic and Statistics Administration. Fall, (2015) . |

[5] | Lee K, Welsh B. The 2020 census is coming. Will Native Americans be counted? Los Angeles Times. June 13, (2019) . |

[6] | US Census Bureau. It takes extra effort by the U.S. census bureau to reach people far outside urban areas. America Counts. December 23, (2019) . |

[7] | Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (the Lancet-Lowitja Global Collaboration): a population study. Lancet (London, England). (2016) ; 388: (10040): 131-57. |

[8] | Connolly M, Gallagher M, Hodge F, Cwik M, O’Keefe V, Jacobs B, Adler A. Identification in a time of invisibility for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States. Statistical Journal of the International Association of Official Statistics. March (2019) ; 35: (71-89). |

[9] | McLaughlin K. A big moment finally comes for the Little Shell: Federal recognition of their tribe. Washington Post. December 21, (2019) . |

[10] | Population Research Bureau. Milestones and moments in global census history. September 4, 2019. Available from https://www.prb.org/milestones-global-census-history/ Downloaded December 16, (2019) . |

[11] | US Census Bureau. History – Censuses of American Indians. Available from https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/censuses_of_american_indians.html Downloaded 27/11/2019. |

[12] | U.S. National Archives. Indian census rolls, 1885–1940. Available from https://www.archives.gov/research/census/native-americans/1885-1940.html Downloaded 27/11/2019. |

[13] | US Census Bureau. Indian census rolls, 1885–1940. M-595. (1967) . |

[14] | Collins JP. Native Americans in the census, 1860–1890. National Archives. Geneaology Notes. Summer (2006) ; 38: (2). |

[15] | Snipp CM. Racial measurement in the American census: Past practices and implications for the future. American Review of Sociology. (2003) ; 29: : 563-588. |

[16] | US Census Bureau. History – Census Instructions. Available from https://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/census_records/censuses/instructions/ Downloaded January 1, (2020) . |

[17] | Office of the Solicitor General, Department of Interior. Opinions of the Solicitor General. September 4, (1940) . |

[18] | US Census Bureau. Measuring Race and Ethnicity Across the Decades: 1790–2010 (Images Mapped to 1997 US Office of Management and Budget Classification Standards. Available from https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/race/MREAD_1790_2010.html Downloaded January 13, (2020) . |

[19] | Office of Management and Budget. Directive No. 15. Race and ethnic standards for federal statistics and administrative reporting (as adopted on May 12, (1977) ). |

[20] | US Census Bureau. Bicentennial Edition, Volumes 1 and 2; Washington, DC; (1975) . |

[21] | US Senate. Making Indian Country Count: Native Americans and the 2020 census. Hearing before the Committee on Indian Affairs United States Senate One Hundred Fifteenth Congress Second Session, February 14, 2018. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC, (2018) . |

[22] | National Congress of American Indians. Census: will you count factsheet? Tribal Directory. |

[23] | Trahant M. The 2020 census is in deep trouble and tribes will lose big. Indian Country Today. September 12, (2018) . |

[24] | Ratcliffe M, et al. Defining Rural at the US Census Bureau. American Community Survey and Geography Brief. ACSGEO-1. US Census Bureau. December (2016) . |

[25] | Norris T, et al. The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. US Census Bureau. January (2012) . |

[26] | Leadership Conference Education Fund. Will you count? American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 2020 Census. Center on Poverty and Insecurity. Georgetown University. Washington, DC. April 27, (2018) . |

[27] | Griffiths K, et al. The identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in official statistics and other data: critical issues of international significance. Statistical Journal of the International Association of Official Statistics. March, (2019) ; 3: (91-106). |

[28] | US Census Bureau. Coverage measurement-post-enumeration surveys. Available from https://www.census.gov/coverage_measurement/post-enumeration_surveys/ Downloaded 2/6/ 2020. |

[29] | Deweaver N. ACS (American Community Survey) data on the American Indian Alaska Native population: A look behind the numbers. National Congress of American Indians. February 18, (2013) . |

[30] | Private correspondence between corresponding author and NCAI. December 17, (2019) . |

[31] | United States Census Bureau. Questions planned for the 2020 Census and American Community Survey: Federal Legislative and program uses. March (2018) . |

[32] | Azure B. Don’t be counted out, be counted in the 2020 census. Char-Koosta News. November 7, (2019) . |

[33] | Fontenot AE. 2020 Census Program Memorandum Series: 2018.06: 2020 census non-English support. United States Census Bureau. February 27, (2018) . |

[34] | US Census Bureau. 2020 Census Snapshot – American Indians/Alaska Natives: Census Partnership AIAN One-Pager. July 2009. Available from https://www.2020census.gov/content/dam/2020census/partnership/materials/july/Handout_for_American_Indian_and_Alaska_Native_Audience.pdf?#. |

[35] | US Census Bureau. 2020 Census Operational Plan: A new design for the 21st century. December 2018. Version 4.0. Available from https://ww2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/planning-docs/2020-oper-plan4.pdf. |

[36] | National Congress of American Indians. Written Testimony of Kevin J. Allis, CEO NCAI. U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform Oversight Hearing on Reaching Hard-to-Count Communities in the 2020 Census. January 9, (2020) . Washington, DC. |

[37] | National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center. Disaggregating American Indian & Alaska Native data: A literature review. A report of the National Congress of American Indians to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Washington, DC. July (2016) . |

[38] | Arias E, Schauman WS, Eschbach K, Sorlie PD, Backlund E. The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. (2008) ; 2: (148). |