Abstract

New Zealand typifies countries that were colonized in that its indigenous population has long remained disproportionately affected by child protection services and their periods of doctrinaire practices, despite decades of reviews, reforms and promises to change. The very broad scope of child welfare services and their complexity require strong means of holding them to account. Diverse operational practices, as well as differing views of the science and received wisdoms are just some of the elements which create a system which is disconnected for those who engage with it. Public agency performance measures and transparency are not sufficient to bring about the degree of accountability that will meet the needs of public legitimacy when there are diverse communities with different histories with child welfare services to take account of. Strong independent oversight is needed to determine what might make it possible for trust to be properly placed, and legitimacy to be sufficiently established at a system level in order to support social workers in their difficult work amongst all communities. The problems for child welfare services in establishing political legitimacy have significant parallels in how agency and system accountability needs to be established across many unrelated forms of public administration.

1.Introduction

In many countries with indigenous populations, child protection and justice systems have a long history of disproportionate treatment involving both child removal and incarceration rates much higher than experienced by other group. In New Zealand this difference has led to rates for Ma¯ori that are often around seven times that of the European population, particularly since the 1960s. A recent increase in the already disproportionate share of Ma¯ori children in State care has again put a spotlight on the legitimacy for Ma¯ori of how the State is involved in the care and protection of children, including the number and form of the removals of babies at birth. For these services whose fundamental elements have come into question, belatedly strengthening of the forms of accountability and transparency is insufficient. Change includes resolving the difficulty of the State in understanding and engaging with Ma¯ori family structures, called wha¯nau, because of their nature. The system, policy or institutional change that Ma¯ori judge would bring legitimacy to ways of ensuring the care and protection of children would not obviate the future need to strengthen how those involved are held to account.

Child welfare services are extensive in their reach, diverse in organizational forms and beliefs, with the most fundamental part being the family, wha¯nau or relevant kin group. The characteristics that make such a complex system work are a common focus; mutual trust and respect; strong collaboration; shared knowledge and continuous improvement. A good number of case studies [4] report that too few of these characteristics are seen across child welfare services at present, and the paucity of regular formal reporting reinforces this conclusion.

It is not unusual for the accountabilities placed on public service agencies to become focused on the efficiency of the agency rather than their impact on the wider communities that they were set up to serve, or the means by which they are or have been performed. The formalized processes by which families and wha¯nau can hold to account the statutory childcare and protection services have been shown to be weak. Weakness in accountability is a consequence of and contributes to a cultural bias against Ma¯ori. The agencies of the State which deal with children have long had a disproportionate effect on Ma¯ori, and current practices cannot ignore the way that past racism will determine the nature and operation of the selection criteria now and into the future.

In practice, in whatever way the tensions between responsiveness and the sufficiency of evidence are balanced when forming judgments, there are personal costs. On one hand, death can result from failure to respond when circumstances justify extreme actions; on the other hand, the process of removal itself has harmful consequences for mothers and the family and wha¯nau that are left behind. In a fully functioning system, how the system as a whole can balance risk is critical if its legitimacy is to be properly accepted in difficult situations. Having trust in the judgements of those empowered to decide when to place children in the care of the State requires demonstrable confidence in the system as a whole – not simply the individuals on the front line.

2.The scope of child welfare services

The wider family or wha¯nau is the dominant means by which children are usually cared for when their own mothers are in adverse circumstances, by supporting them or substituting for the care and protection they give their children. The grandparents of wha¯nau and families care in this way for about twice as many children as do statutory services. These carers often give up jobs to do this through personal choice and obligation. In such situations there can be support from the child welfare system including families and wha¯nau. Iwi and Ma¯ori health and social service providers also work alongside wha¯nau to support the directions they set.

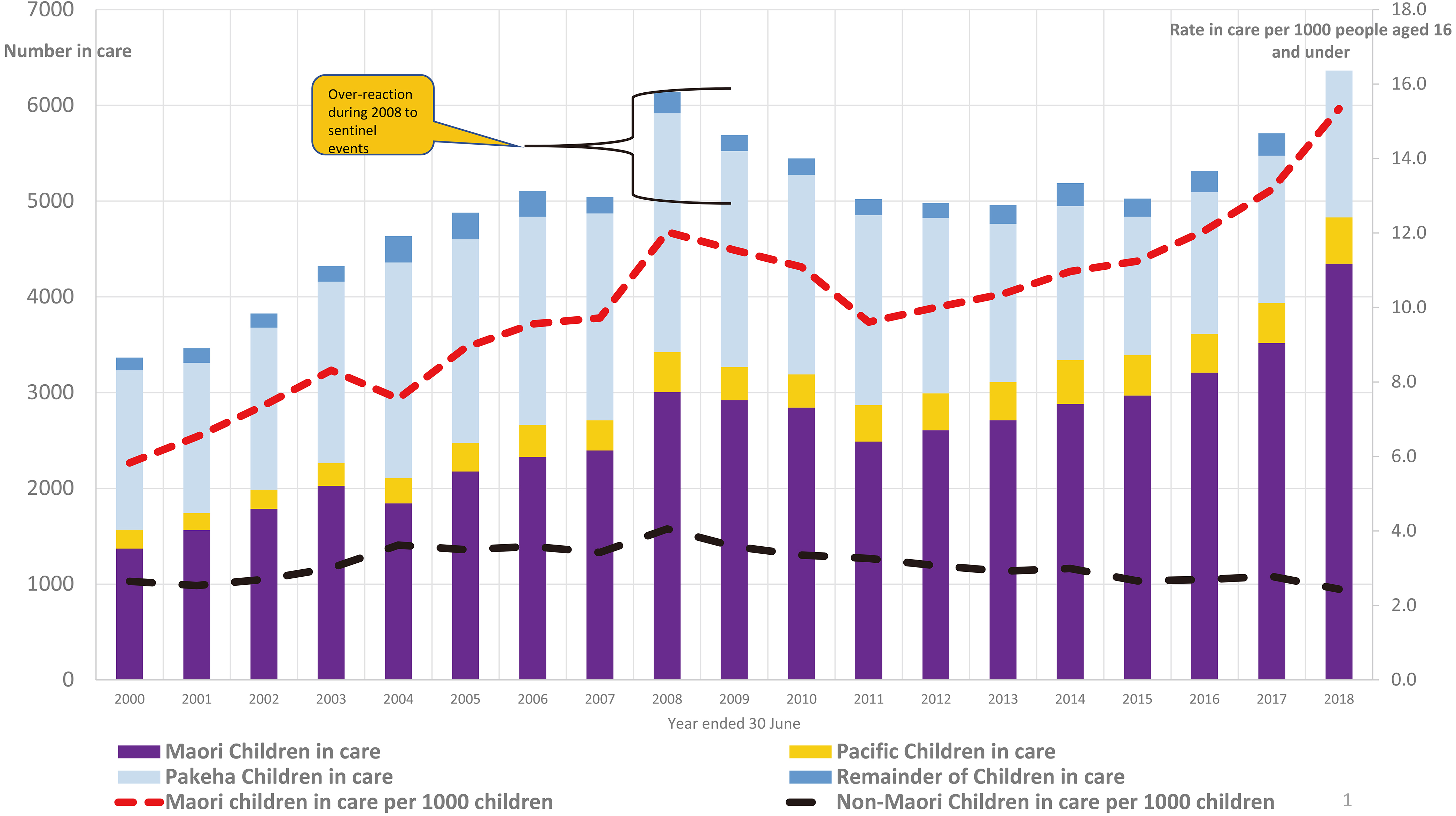

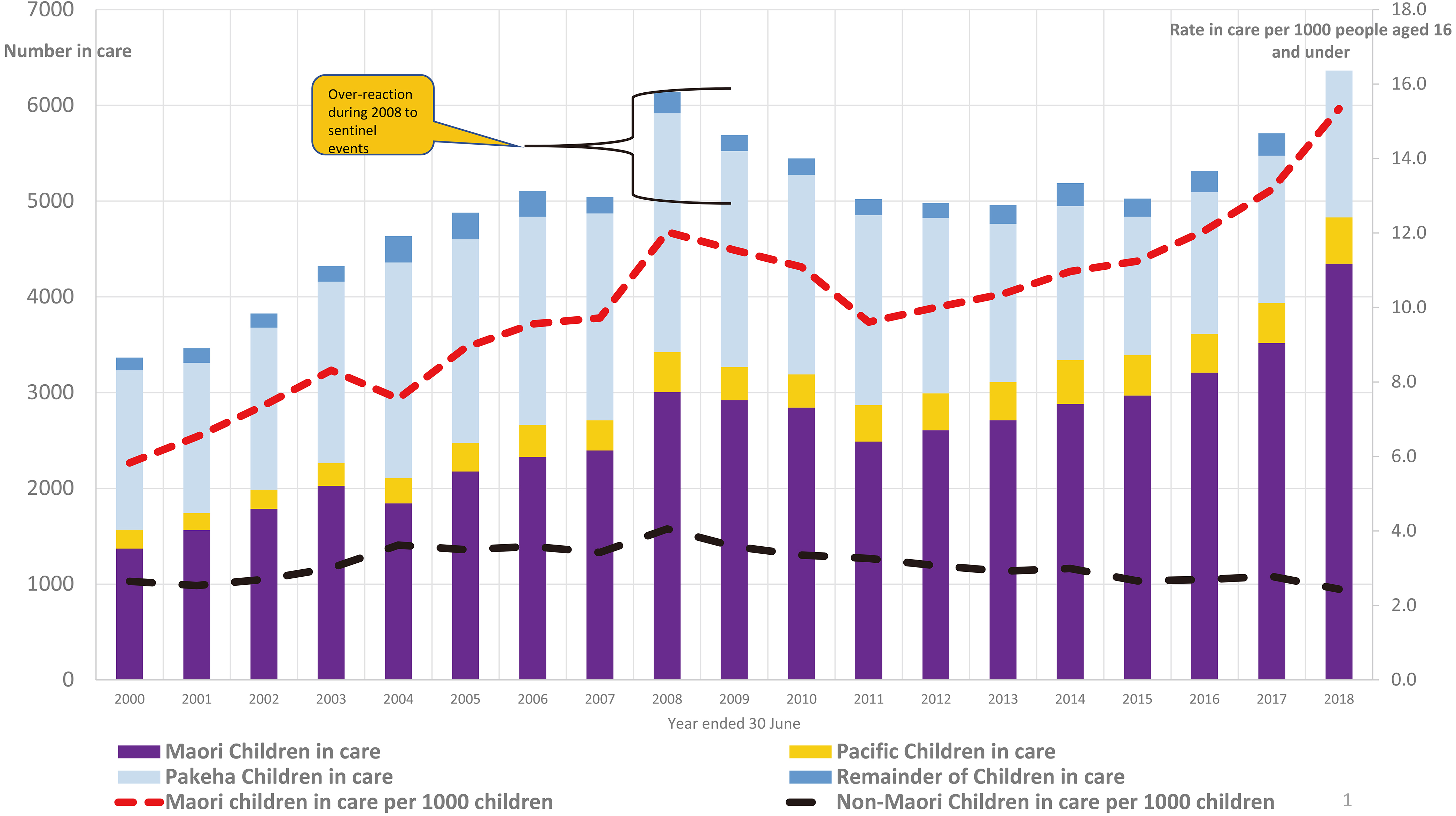

Figure 1.

Maori number and population rate in care of Oranga Tamariki compared to Non-Ma¯Aori. Sources: CYPS statistics, MSD Website. Official Information Act requests of Oranga Tamariki. Author calculation of age specific rates. “Pacific” includes children of a Pacific Island ethnicity born either in New Zealand or in their country of origin.

Where it has reason, the State can choose to enforce its legal authority, systems and resources on any individual family or wha¯nau, subject to the oversight of the Family Court. The nature of this authority, the power of its reach and potential disempowerment of families is not balanced by the forms of accountability established by Parliament for the oversight of the Executive. Independent means are needed to provide reason for the community collectively to accept the legitimacy of this State authority, while still challenging individual decisions. This independent demonstration of political legitimacy needs to occur alongside comprehensive regular reporting and research of the context within which the child welfare system as a whole operates to care for children. When this does not occur, then the State by default demands its frontline staff to function in accord with the authority acknowledged in statute of their role, but without proper resolution of the political legitimacy of their actions by those that should do so.

The power of the State to break up families and to remove children in order to protect a child from continuing harm is a dimension of family policy that is embedded in statute, as is choosing where a child that is removed is to be placed, and for how long. When the immediate safety of children determines outcomes, it is still important that their future life course and the resources of wha¯nau and families have a place in influencing decisions by all players, especially the Family Court. How this works needs to be properly systematized so that its effectiveness is not dependent on any party with a focus on particular outcomes.

3.Child Welfare services of the State have not had the same effect on different cultural groups

Seeking a wha¯nau voice in the child welfare services of the State has been obligatory in law since the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989. Up to now this voice has been weakly heard or avoided, so that wha¯nau have had few means or resources to hold the child care and protection system of the State to account for how wha¯nau members enter this statutory system or are treated in it. Child welfare services have operated in the past in a wider environment where wha¯nau are not recognized in regular statistics nor has much of the history of research and scholarship played a part in policy or practice. When wha¯nau are recognized they are most often seen through an extended nuclear family lens, if that. The Puao-te-Ata-tu report (Department of Social Welfare 1986) remains a major point of reference for assessing how significant challenges by Ma¯ori to the legitimacy of State action need to be addressed. An expert review in 2015 (Ministry of Social Development. 2016) was the most recent to report on progress.

The State’s child protection agency, Oranga Tamariki, reported that it had taken into its care 6,365 children at 31 December 2018, being made up of one in 65 of all Ma¯ori children and one in 400 of all other children aged 17 and under. Placing of children into the custody of the State has disproportionately affected Ma¯ori for some seventy years, most particularly in the decade after 1972/73. Those Ma¯ori boys who entered the care and protection system in that decade continued in later life to be institutionalized at a far greater rate than any group that went before, as was the cohort of their children. More recent trends are presented in Fig. 1.

While 1.5 percent of Ma¯ori children aged 17 and under are currently in the care of Oranga Tamaraki, it has been estimated by an expert review [6] that during their childhood, one in five children overall would have had some experience of the care and protection system by the time they reached 17 years. Since 2015, the number of babies removed from mothers by the State has increased by one third, with all except one of the increased 70 babies being Ma¯ori.

In the context of weak mechanisms that demonstrate accountability, the recent increase in the share of care and protection actions involving Ma¯ori bring uncertainty to how further changes in law that came about from July 2019 could affect later generations. Strong and trustworthy vindication of the State’s child care and protection system is needed because of the damaging and perverse effects on the welfare of mothers and their children (including the unborn) when they withdraw their trust in institutions that exist primarily for their care, by avoiding the help they exist to give. The mix of bodies that have an increased statutory responsibility for the welfare of children is now quite pervasive. The State’s child care and protection system has yet to assure those who operate alongside it or who are the subject of its use of its statutory powers about the full integrity and coherence of the system as it now stands. The State has not tried hard enough to do that with Ma¯ori, yet they make up the majority of the children in its custody.

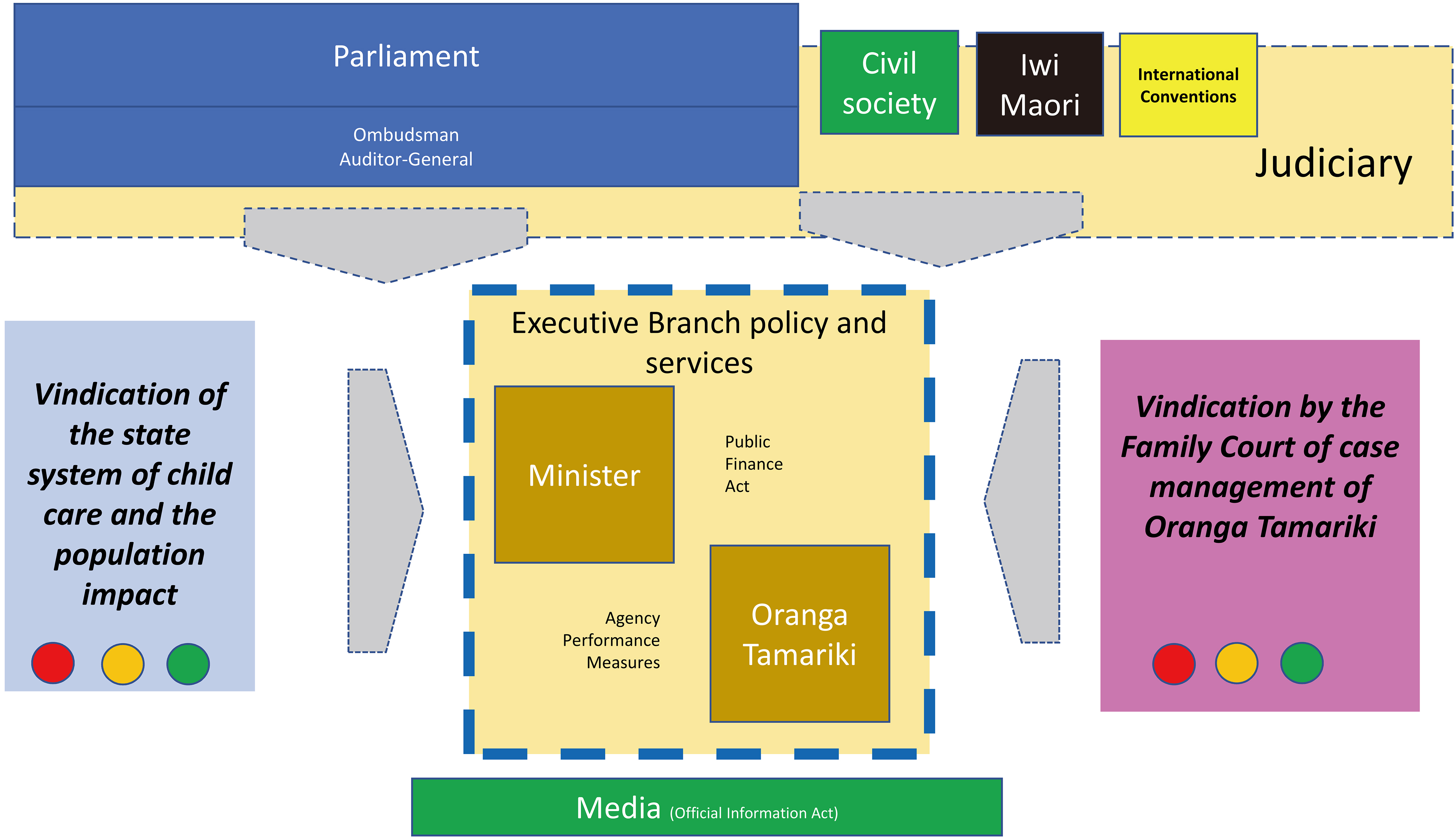

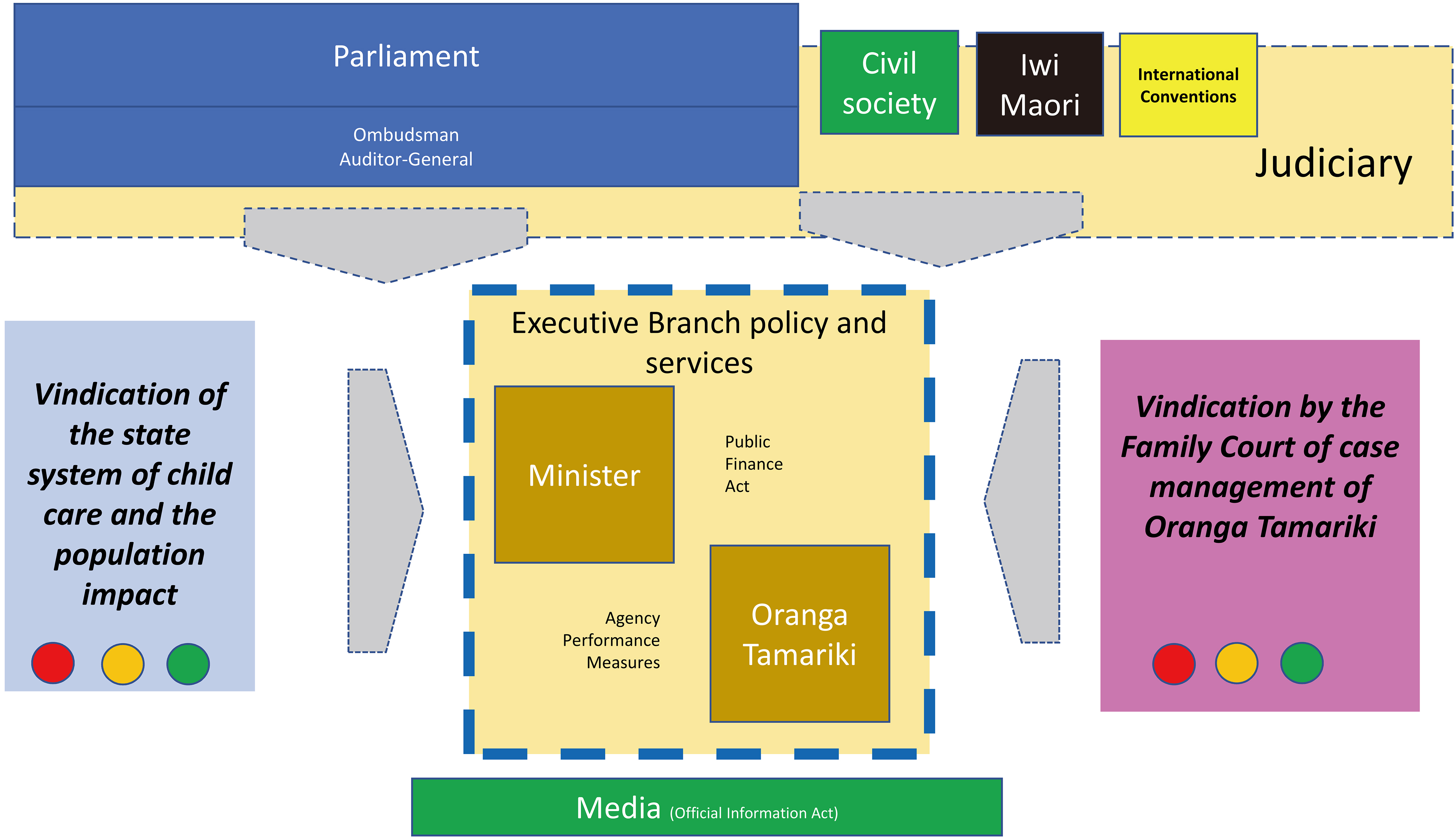

Figure 2.

Oversight of the trustworthiness of state child care and protection.

4.Come-at-ability and legitimacy

The proper use of any State sanctioned powers to remove people from where they are, whether it be to incarcerate them or place them in some other form of custody or guardianship, must always involve proportionate oversight so that all know that their the lawful rights are able to be enforced. Even when the legitimacy of State action is generally accepted, retaining trust may necessitate that compliance with the rule of law be transparent, and that actions be properly overseen or reviewable by a judicial body independent of executive government. Because the State has long used its authority to take custody of Ma¯ori children at a disproportionate rate this has periodically led to several generations of Ma¯ori seeking to challenge to the legitimacy of this State action.

When they have reason to challenge the legitimacy of State actions, individuals, civil society and the media will find ways to withdraw trust in any action by the State. Institutions and roles outside executive government including Parliamentary Officers, Appeal Courts and Parliamentary petitions might be vehicles for this, but individuals need to have common access to them. The breadth and extent of accountability should depend on the impact when citizens withdraw trust. The diverse accountability mechanisms and multiple roles of different parts of the system that we have now do not provide citizens with an informed basis for granting or withdrawing trust. How the various parts connect is shown in Fig. 2.

We know very little about how the decisions of the Family Court influence the practices of Oranga Tamariki. This means that critical components of the statutory childcare and protection system can escape effective scrutiny because of the weak accountability of some other part. Similarly, we know little about the how and when the other parts of the State’s child care and protection system interact where it includes social workers, police, midwives, hospitals, obstetricians, lawyers and non-government organisations.

Because the oversight of the State’s child care and protection system does not extend beyond agency performance measures and strategic plans, these do not bring a genuine understanding of the workings of the whole child welfare system. There is weak recognition in policy of the importance of family and wha¯nau in their independent and practical resolution of short term or longer breakdown in the care of children, or the costs they bear. Because of the different institutional cultures and incentives of those who may play a part in determining the outcomes for any individual child, proper oversight needs to be able to provide a relevant window on bodies that have varying degrees of independence in how they meet their statutory obligations including those to families and wha¯nau. A high degree of operational independence exists alongside varied oversight and weak connections. The disproportionate intensity of State action on Ma¯ori needs vindication, which in itself would be expected to challenge the fundamentals of the system. Transparency is not enough when the focus is selectively narrowed to weak self-reporting of the practices of operational activity. This obscures scrutiny of decision-making processes and long-term impacts, as well as of how underlying models of care and protection are applied in practice. O’Neill 2009 argues that a proliferation of accountability mechanisms by governments did not necessarily increase trust. She asks whether systems of accountability are meant to replace trust or to improve the basis for placing and refusing trust. In arguing that trustworthy oversight that can hold the State to account must have an authority that is beyond that applied by institutions engaged in the activity, O’Neill noted that:

“To be accountable is not merely to carry a range of tasks or obligations, for example to provide medical treatment to those in need, to make benefit payments to those entitled to them, or to keep proper accounts. It is also to carry a further range of second-order tasks and obligations to provide an account of or evidence of the standard to which those primary tasks and obligations are discharged, typically to third parties, and often to prescribed third parties.”

Holding the child care and protection system to account needs independent oversight comparable to that of the Ombudsman. It has to be able to make transparent the actions of the courts and know how the institutions and courts challenge their own practices through the impact on children, family and wha¯nau. The focus on the child cannot escape consideration of its family and wha¯nau, mothers and the science of child development. Because the impact on Ma¯ori of State care and protection has had such a long reach and high impact, this must shape the way the State recognizes that it has a special need to be able to be held to account at any time by iwi Ma¯ori, for its outcomes, practices, evidence base and underlying philosophy. What makes indigenous communities unique is that it is only through child-birth and the survival of children that they will continue to exist. Immigration can play no part in their demographic dynamism.

5.The consequences for attaining trust of the different histories of Ma¯ori and Pa¯keha¯

The long reach of past experiences and practices continues to affect the trust and attitudes to State custody today by older generations of Ma¯ori men and women. Jackson (1987) and Williams (2019) provide a comprehensive distillation of the place of the justice and child welfare systems in the colonisation of New Zealand and the continuing impact on Ma¯ori. In New Zealand, as in Canada and Australia, two particular doctrinaire policies dominated child welfare practice for long periods up to the mid-1980s, leaving residual effects on the cohorts that they were applied to.

During the 1970s, a longitudinal study by the Department of Social Welfare of all boys born in 1957 [2] found that two out every five Ma¯ori boys had come into contact with the care and protection system by age 16 years, with one in fourteen being placed in a custodial institution. This shameful taking of Ma¯ori boys into State custody took place for over a decade until it abated in the mid-1980s. These children are now disproportionately represented in prisons.

The parents, grandparents or even great grandparents of some of the Ma¯ori children of today will have been subject to the 1955 Adoption Act, as teenage mothers, fathers or babies. During the peak period between 1944 and 1980 it is estimated that some 87,000 Ma¯ori and non-Ma¯ori babies of mainly teenage unmarried mothers and fathers were placed in adoption, with many of these mothers under duress to do so. The father was often not recorded on the birth certificate.

A much larger share of adult Ma¯ori have been through State custody in New Zealand compared to any other ethnic group. Because Ma¯ori wha¯nau involve a much larger “family circle”, then where historical contact by wha¯nau members with the State’s child care and justice systems increase the possibility of being selected as at risk, young Ma¯ori who wish to be mothers will be more likely to be required to be assessment. This contributes to system bias, even if the tests themselves that focus on previous contact with the Justice or child protection services have been designed to be administered without bias. The cumulation of historical factors, demographic and social structures and selective monitoring strengthen the shadow cast by past bias and predetermine the outcome of selection criteria. Each additional selection criterion by the statutory child protection and care system widens the gap between the opportunities of motherhood faced by Ma¯ori and those of non-Ma¯ori women even when they have the same likelihood of being a good mother.

The economic gains in the post war period came at the cost of the rapid urbanisation of Ma¯ori which took place at a time when strong wha¯nau structures would have been especially important for the major demographic transition and population growth that high fertility and falling mortality underpinned. The impact of the 1984 Lange government’s policies on employment opportunities fell hard on the cohorts who were born in the latter part of this demographic transition but before the decline in fertility rates. These were the cohorts affected most by the very high levels of State custody of Ma¯ori children over the decade from 1973/74.

Where Ma¯ori are able to contend that colonial patterns of the past are still in operation when social attitudes and values are built into legislation and social services, these policies in turn serve, at best, to undermine or undervalue differing patterns of social behavior in raising children and, at worst, to deliberately fragment social and psychological supports.

6.Influences on the shape and operation of child welfare services

6.1Risk

The child care and protection system of the State will make a difference between life and death for a small number of children, while for many others it may bring the only means of redress and response to situations of abuse. In the face of complexity in the system in its rules, practices and powers, for most people knowledge of what the State does comes from rare highly visible cases. These cases typically involve the death of a baby by the intentional violence of a carer, or the contested removal of a baby at birth from its mother. By how they respond to such sentinel events when they become of public interest, those who manage the operations of the State, in public administration as well as politicians, can determine their effect on future policy and practice. There are a multiplicity of participants who could seek to minimize the potential for their association with a sentinel event. It is the children and their wha¯nau who bear the consequences when State responses have shown a predisposition towards lowering the threshold for child removal, hence removing more children from their family into State custody. The future life of the child, its mother, family or wha¯nau must be a demonstrable part of consideration for removal and consequent placement.

When individuals withdraw trust because they judge that removal processes do not have legitimacy for their community, we cannot predict the range of unintended consequences. The welfare of mothers and children is affected if they think that they need to avoid any of the institutions of the State, for example where mothers and others avoid contact those who provide health care, security and safety from harm. Because processes for the vindication of the practices and outcomes of child care and protection are weak, the State is poorly prepared when challenged in cases where problems have arisen. By not being able to identify whether sentinel cases typify their practice or are outliers, community doubts about the legitimacy of State actions can grow.

The evidence informing judgements in complex cases will not always be strong or able to be independently substantiated. Statutory obligations to know what makes up the family, wha¯nau or other most relevant relationship group requires cultural understanding and sensitivity that is likely to challenge the norms that were embedded in public policy in the past. This will be more so at a time of change when the threshold for harm has become more loosely defined and case law around applying new law is limited or absent. Getting it right or wrong, other harms are likely to be a consequence when power is variably applied in situations of uncertainty. A recent study suggest that there is a greater likelihood of ethnic bias when social workers are at the point of making substantive decisions than at other times when balancing safety and possibility of harm [4].

The State childcare and protection system comprises different professional and institutional structures and cultures. Each of these have embedded in them attitudes to risk and these differ across medical, legal and welfare cultures, police, different civil service groups, community sector organisations and iwi Ma¯ori, as well as judges and politicians. Thresholds of risk can become volatile after sentinel events, resource shifts, frequent institutional restructuring or policy redirection. Conflicting views on practice or philosophical matters that are not properly confronted can affect trust within the wider family and wha¯nau welfare system. One outstanding example arises because of the very different views held by midwives and social workers on the way a mother should connect with her baby immediately after birth in the event that a forcible removal of a baby has been planned.

6.2Reactions to sentinel events

In a small country such as New Zealand, it is not unusual in the justice sector or in child protection for rare events to influence law changes. This also occurs in health but with lower frequency. The greater the chance that rare or sentinel events can determine policy, the more vital it is that responses to any rare event are seen in the context of a strong well-established evidence base as well as practices that are demonstrably up to the task. The power of a single event to influence public policy and practice can be stronger the more horrific the case and the attention associated with it. This may be contrary to evidence. In New Zealand, for the last 25 years, there has been little evidence of change in children being at risk of harm. No noticeable trends exist in recorded incidents of infant death by intentional injury. As often occurs with rare events, a low average number can be associated with a high degree of year to year variability. In New Zealand the annual average of each of fatal and non-fatal intentional injury to children aged four years and under for both Maori and non-Maori was unchanged or lower in the nine years to 2018 compared to the nine years to 2008 to.

There have been attempts to prevent some of the nearly 300 forced baby removals in 2018, and a small share of these attempts have been become highly visible to the public.

Table 1

State removal of Babies from mothers, Non-Ma¯ori and Ma¯ori

| Year ended June | Total number of removals of babies1 | Total removals per 1000 births | Ma¯ori removals2 | Ma¯ori removals per 1000 Ma¯ori births | Non-Ma¯ori removals per 1000 births | Total births3 | Ma¯ori births3 |

|---|

| 2012 | 225 | 3.7 | | | | 61,032 | 17,385 |

|---|

| 2013 | 216 | 3.6 | | | | 59,862 | 16,905 |

|---|

| 2014 | 227 | 3.9 | | | | 58,608 | 16,518 |

|---|

| 2015 | 211 | 3.5 | 110 | 6.7 | 2.3 | 59,616 | 16,470 |

|---|

| 2016 | 247 | 4.2 | 147 | 8.9 | 2.4 | 58,995 | 16,545 |

|---|

| 2017 | 275 | 4.7 | 178 | 10.9 | 2.3 | 58,344 | 16,323 |

|---|

| 2018 | 281 | 4.7 | 179 | 10.3 | 2.4 | 60,321 | 17,394 |

|---|

Neither of these extreme forms of rare event is a substitute for an effective, accurate and comprehensive window on the State’s child care and protection system, and on the context within which it has to operate. In the absence of an informed window, a rapid escalation in the removal of children by the State can more easily triggered by the publicity of a particular case, than a change in the number of such deaths. The Table 1 shows the most recent glaring example of such escalation following three highly publicized deaths very young children in 2007. During 2008, the number of children aged under 17 years taken into the care and protection of the State increased by 1,092 or 21.6%. In the following three years, the number in care fell back to below its previous level and did not exceed the 2007 level again until 2014.

6.3Validation of the science behind child welfare practice and policy

The science that influences thinking about child protection has seen major changes and significant reversals over the past seventy years since the professionalization of social work began to evolve. The transparency and validation of the application of any science should be a matter of periodic scrutiny. In particular, this concerns theories of child removal and adoption, trauma, social work training and methods of quality assurance. Early research by the Department of Social Welfare into the experiences of birth mothers following adoption pointed to a high need for understanding and ensuring ways of managing the impact on the mother’s physical and mental health of any such loss of a child.

The common rules, obligations and tests of eligibility that are being applied to Ma¯ori have been based on analysis and knowledge dominated by the characteristics generally measured and modelled for Pa¯keha¯ because of the limited scale of Ma¯ori-specific statistical sources. In the application of policies developed in this way, such ethnic bias inevitably leads to that part of the population which is Ma¯ori often being systematically identified and treated as outliers, rather than as a community whose distinct characteristics need to be measured and reliably accounted for. This failure to account for, measure and treat as distinct, the differences from culture, social and demographic structures remains, as does weak understanding of the effect of the pathways experienced by earlier generations of Ma¯ori. The rules that bring mothers to the attention of the State’s childcare and protection system need to be regularly audited by relevant professionals including those with deep knowledge of wha¯nau to identify whether they are potential sources of systemic bias against Ma¯ori. For each case, how wha¯nau were involved in the process should be reported on by each of the key agencies and the wha¯nau, and these reports should be summarised in an annual report that is independently audited by a body that is culturally and professionally appropriate. Apart from a minimal piecemeal start in publishing of statistics, the most visible sign that change is occurring is the recently established Oranga Tamariki Evidence Centre. This is the first move by the government’s child protection service in nearly two decades to embed in the organization a research system about child welfare and build on the rich legacy of research and evidence that occurred in New Zealand between the 1960s to 1980s. While it is far from enough, it has become a well valued move and its visibility and range of work has become well connected to those who play a part in either challenging or validating the important work that child protection has to do.

Because of the complexity of child welfare services, a sample of cases should be regularly followed through the system in order to evaluate and improve processes and connections between the parts of the system. There needs to be a comprehensive mapping of the interactions with children, families and wha¯nau of any agency whose actions involve obligations and responsibilities to the child care and protection system of the State. For example, understanding and ensuring ways of managing the impact on the mother’s physical and mental health of removal of any children from a mother should be required whatever the justification for such removal. Because the connections between organisations are vital, such as the proper and comprehensive informing of the Family Court, then a review and feedback process between these institutions needs to be established. Keddell and Hyslop 2019b surveyed three regional operations of Oranga Tamariki and identified a number of practical reasons that limit a commonality of practice and continuous improvement approaches.

Child care and protection concerns highlight limitations in the evidence available for regular scrutiny and oversight by Parliament, courts, civil society and iwi Ma¯ori. The publication of statistics about the operation and impact of care and protection services has reduced over the past two years and minimal information is available regularly. Statistical reporting of the entry and exit of stay in the State care and protection system needs to be timely, regular and comprehensive. It should provide information on the age, ethnicity of individuals along with the statutory basis for the State’s involvement and the circumstances that triggered that involvement. Such information should be available in a readily useable form such as spreadsheets. Where children are placed in care, and when they leave is important, as is knowledge of how the wider institutions of the State for education and health are contributing to the wellbeing of children in the care of the State.

7.Conclusion

Child welfare services are wide-ranging, and they do not readily form into a coherent system. Yet without understanding their many parts and complexity we can undermine the protection of the rights of any child to the care and support of kin. Strengthening accountability is just one step in this. The State can be blind to the predominance of care that is that provided by families and wha¯nau, particularly grandparents for children who are in situations of concern. This form of care needs to be reflected in policy and practice, and the application of the powers of the State must support rather than endanger this.

The legitimacy for mothers, family and wha¯nau of the actions by the State when acting to protect the welfare of children will not be established by the performance measures and fiscal oversight that make agencies accountable to the Ministers of the day. Where huge differences have existed and continue to do so in the processes and outcomes experienced among communities, then the much more complex requirements of legitimacy need to be understood at a community level. Whereas in the past children have been taken into State care on a scale we would never countenance now, then among communities that were affected, strong memories will remain among the grand-parents and great grand-parents of the children of today, or their friends and relations. Doubts of legitimacy will be magnified by experience of processes which do not recognize, respect and take account of the distinct history, demography and cultural institutions and mores of communities which remain disproportionately targets of State agencies. Because the earlier disproportionate impact on Ma¯ori children of State custody remains at the historically high rates, it requires much more transparency than exists at present, to facilitate ongoing scrutiny and inform the development and support of alternative approaches. The experiences of Pacific children justify similar scrutiny.

Accountability needs to be comprehensive, have independent elements and be focused on the outcome for the child and their kin, as well as the quality of the processes with which they engage. Having wide ranging accountability will not prevent harms but lacking adequate means to hold the State to account enables further harms. The intensity and nature of accountability should depend on the impact when citizens withdraw trust. What happens to children once in the care of the State brings different risks of neglect and harm to their continuing welfare and life chances that need overseeing.

Ma¯ori who are great grand-parents and grand-parents today were part of cohorts that experienced severe forms of discrimination and disproportionate involvement in earlier versions of the current State institutions. This harmed the later lives of many. The legitimacy of State action needs to be earned, rather than just asserted. Ma¯ori and Pa¯keha¯ their different histories and pathways require not only different processes but also they should shape the nature of accountability. Statistical practices that should play a part in building legitimacy must involve forms of continuous improvement, evaluation studies and operational research of processes. Cohort studies are essential for understanding the impact on diverse communities, which will necessitate a continuing vigilance in the measurement of ethnicity. As child protection services focus increasingly on the apparent delinquency of mothers compared to that of children, the characteristics of mothers and the basis for their selection needs to be able to be monitored. Mothers in indigenous communities generally have their first child much younger, and may have themselves been in care, yet both of these are characteristics often found in risk models which lead to screening. In such a complex area, case studies become critical tools, as is independent oversight and reporting. A key New Zealand initiative will be an independent oversight function established in the Office of Children’s Commissioner. Given that the regulation and monitoring of child protection has been in place since the Child Welfare Act of 1925, putting in place this new oversight function ought to be accelerated, now that Oranga Tamariki has begun its third year. All statistical reporting of the State care and protection system needs to be timely, regular and comprehensive. It needs to distinguish between the entry and exit of stay in State care and protection system and the analysis of those in State care at regular intervals.

Child welfare services exemplify many of other activities that public services carry out that depend on the goodwill of the public for their effectiveness. As agency accountability measures have increasing focused on fiscal measures and outcomes information, the legitimacy of the practices that are employed by agencies has become less demonstrable. Few aspects of public administration, from running population censuses to collecting tax, can escape such obligations although they may be evaded all too frequently.