Publishing and using parliamentary Linked Data on the Semantic Web: ParliamentSampo system for Parliament of Finland

Abstract

This paper presents a new infrastructure and semantic portal called ParliamentSampo for studying parliamentary speeches, culture, language, and activities in Finland. For the first time, the entire time series of some million plenary speeches of the Parliament of Finland (PoF) since 1907 have been converted from text into knowledge graphs and data services in unified formats, including CSV, Parla-CLARIN, ParlaMint, and RDF Linked Open Data (LOD). The speech data have been interlinked with a semi-automatically created ontology and a knowledge graph about the activities of over 2800 Members of Parliament (MP) and other speakers in the plenary sessions of the PoF. The data was enriched by data linking to external data sources and by reasoning into a broader LOD service. Knowledge extraction techniques based on Natural Language Processing (NLP) were used for automatic semantic annotations and topical classification of the speeches. The data and data services have been used in Digital Humanities (DH) research projects and for application development, especially for developing the in-use semantic portal ParliamentSampo. The infrastructure and the portal were published on February 14th 2023 on the Web using the open CC BY 4.0 license, and quickly gathered thousands of users, including citizens, media, politicians, and researchers of politics. ParliamentSampo is a new member in the “Sampo” series of over 20 interlinked LOD services and semantic portals in Finland, based on a national Semantic Web infrastructure. Although the paper uses Finnish parliamentary data as a case study, the approach, methods, and tools presented can be adapted also to other parliamentary datasets in other countries.

1.Parliamentary plenary speeches as FAIR data for problem solving

A foundation of democracy in any constitutional state based on rule of law is openness and transparency of political decision making. An important requirement of this is provision of open access to parliamentary data for the voters, media, parliamentarians, and researchers of politics. The minutes of plenary sessions in parliaments in particular provide lots of information about the democratic decisions made, political life, language, and culture [4,15].

This paper concerns the problem of publishing and using data about the plenary session speeches of parliaments and the parliamentarians involved in the discussions. As a case study, the Parliament of Finland (PoF) in considered. An infrastructure and system called ParliamentSampo – Parliament of Finland of the Semantic Web is presented that is based on openly available data services and Linked Open Data (LOD) knowledge graphs (KG) in a SPARQL endpoint [18,21]. The data has been used in parliamentary research studies and for creating an in-use semantic portal ParliamentSampo.11

The minutes of the plenary sessions of the PoF have been available openly as printed books at the Library of Parliament and Archive of Parliament, and later also through the PoF’s open data service as scanned PDF documents, HTML pages, or as XML documents, depending on which parliamentary sessions are in question.22 However, they have not been published as data in accordance with the modern FAIR principles in a Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Re-usable form for searching, browsing, and data analytic applications.33 If the user knows during which parliament a speech was given, he could download, e.g., a scanned minutes book, which can be over thousand pages long, and search for the speech and other information in the document. But if one wants, for example, to find out the answers to the following questions, this kind of online service and research method based on downloading and close-reading documents is not a viable solution:

1. Question: Which MP was the first to speak about “NATO” in the PoF? Answer: Mr. Yrjö Enne, the SKDL party, May 27, 1959

2. Question: Who and which party have talked the most about the political concept of “finlandization”? Answer: Mr. Georg Ehrnrooth, the National Coalition Party

3. Question: Who has given most often regular speeches (varsinainen puheenvuoro in Finnish) and when? Answer: Mr. Veikko Vennamo, the SMP Party, over 12600 speeches in 1945–1987 in total

4. Question: Which MP most often interrupted with an interjection the speeches of ministers Annika Saarikko, Krista Kiuru, and Sanna Marin in the parliament 2019–2022? Answer: Mr. Ben Zyskovicz. In the cases of Saarikko and Kiuru, 46% of the interruptions are due to him, and in the case of Marin 39%.

The answers to this kind of questions, for example, can be determined computationally with the help of the ParliamentSampo’s data, LOD service, and portal to be discussed in this paper. This system is based on the national Finnish LOD infrastructure [19] and the “Sampo Model” [17] that (1) explicates principles for collaborative LOD production based on a shared ontology infrastructure, and (2) principles for user interface design where semantic faceted search and browsing is seamlessly integrated with data-analytic tools needed in DH research [27]. This approach arguably suggests for a paradigm change of Digital Humanities (DH) on the Semantic Web [16].

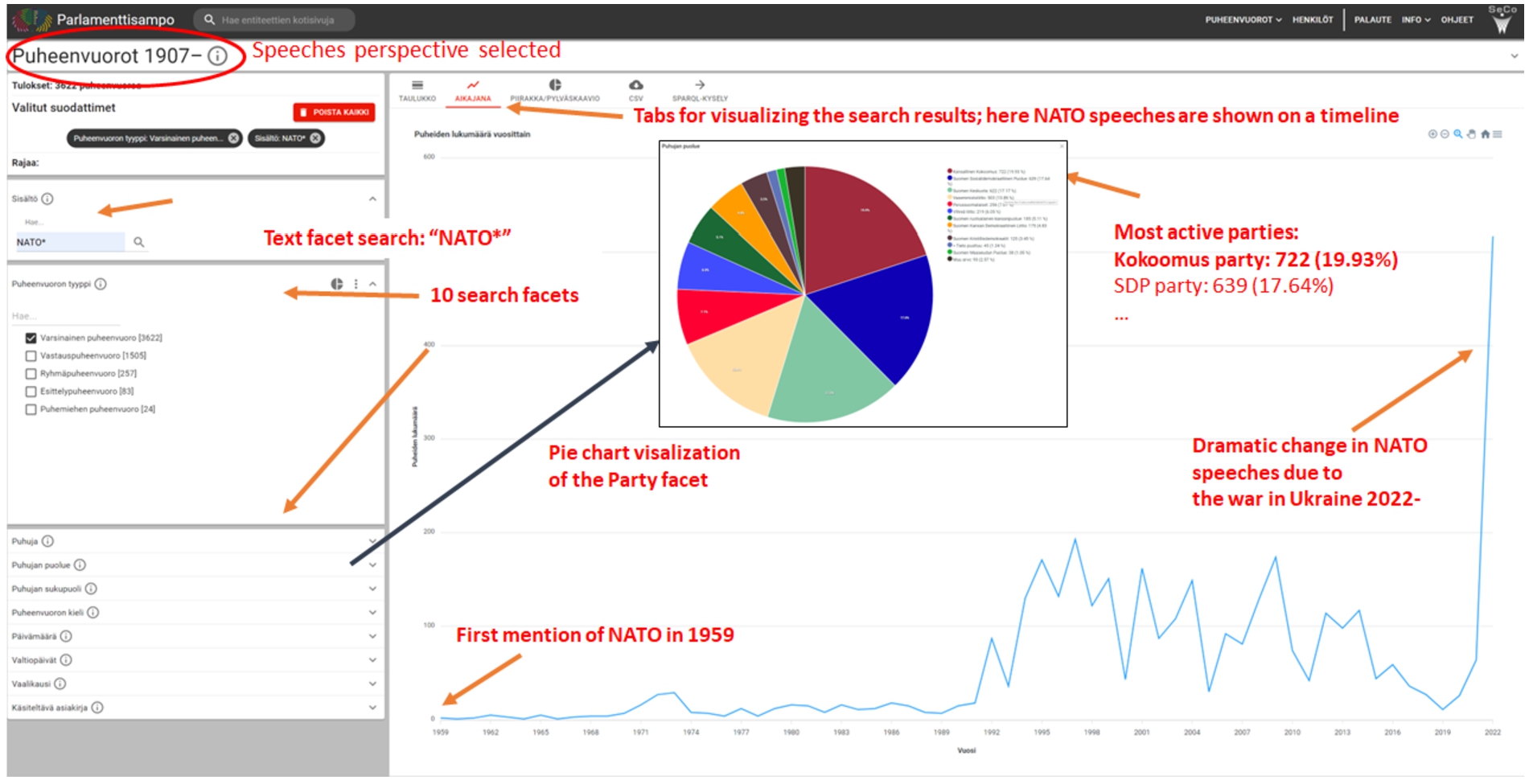

For example, to answer question (1) all speeches mentioning “NATO” can be first filtered using the text search facet. The results can then be sorted by the time of the speech or by visualizing them on a timeline. For question (2) the faceted search hit counts available on the speaker facet and on the party facet after filtering speeches mentioning “finlandization” tell the answer; the distributions of speeches along facets can also be visualized using, e.g., a pie chart on the facet. For answering question (3), the speech type facet is first set for filtering regular speeches. After this the speaker facet hit counts tell that Mr. Vennamo has given most speeches. By selecting him next on the speaker facet the result set of his regular speeches can be visualized on a timeline. Answering question (4) is based on the fact that interruptions were marked in the original textual transcripts of the primary minutes’ data and were extracted as RDF data when transforming texts into linked data. Google Colab with Python scripting based on SRARQL querying the underlying triplestore was used to calculate an “interruption matrix” telling who has interrupted whom and how often.

This paper presents the data publishing infrastructure ParliamentSampo about the speeches and politicians of the PoF, starting from 1907 when the PoF was established. The focus is on the data about the speeches given during the plenary sessions of the PoF. To cater different user needs, this data is published in different formats, including CSV tables, XML-based formats Parla-CLARIN and ParlaMint, and, most importantly, as Linked Open Data knowledge graphs in RDF form. The usability of the infrastructure has been tested in Digital Humanities (DH) research projects and in developing the semantic portal ParliamentSampo in use on top of the LOD service SPARQL endpoint.

This paper is a substantially extended version of our earlier workshop paper [21],44 extending and aggregating results from our other papers about ParliamentSampo, too [9,22,23,42,67]. For the first time, the full ParliamentSampo system is presented, including OCR work, data transformations, ontology creation, data publishing, semantic portal implementation, as well as demonstrations on using the LOD service and the portal application. The data resources, services, and portal were published on the Web on February 14th, 202355 and were soon used by thousands of end users.

In the following, related research on parliamentary data is first reviewed (Section 2). After this the data-driven creation of the underlying ontology of the PoF is discussed in Section 3 and the data production pipeline of the mostly textual speech data and its different outputs are explained (Section 4). Examples of using the ParliamentSampo speech data in different ways are given to illustrate the usability of the infrastructure in research (Section 5). In Section 6, the ParliamentSampo portal is presented as an application of the LOD service and its open SPARQL endpoint. In conclusion, results of our work are summarized (Section 7) and further development suggested.

2.Related work on parliamentary speech data

Parliaments and cultural heritage organizations in different countries have created parliamentary speech corpora and digital parliamentary datasets of both historical and contemporary parliaments [12,37]. The goal of this work has been to improve the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and re-usability of these key documents of democratic societies for the public, researchers, and other users. The digitization has also allowed researchers to engage in novel and interdisciplinary research using the new parliamentary data. As part of the digitization and research initiatives, web user interfaces and data services have been developed that allow to browse, study, and download the digitised materials. An example of this is the Lipad project and the Canadian Hansard66 [3].

The projects on parliamentary data have focused on the curation, annotation, and harmonization of the national parliamentary corpora. Also semantic web technologies have been applied for linking and enriching the parliamentary data with other datasets. In the pioneering project Linked Data of the European Parliament (LinkedEP), the debates of the European Parliament and the political affiliation information were connected as linked data into other datasets, such as DBpedia and the EuroVoc thesaurus [76]. The LinkedEP data was made available through a SPARQL endpoint and an online user interface. The Open Data Portal of the European Parliament provides today lots of datasets as LOD and in CSV format.77 Other examples of linked data parliament initiatives are the LinkedSaeima for the Latvian parliament [7], the Italian Parliament data,88 and the historical Imperial Diet of Regensburg of 1576 project [6]. An EU level initiative for harmonization and annotation of national parliamentary corpora is the ParlaMint project as part of the CLARIN infrastructure.99 The ParlaMint project applies the TEI-based Parla-CLARIN scheme,1010 and created uniformly annotated multilingual parliamentary corpora with its partners. The ParlaMint II corpus involves 27 national parliamentary corpora [54] (see also [55]).

In Finland, the minutes of the PoF have been digitized by the Parliament itself, but are challenging to use, as they have been produced separately for different periods, stored in different data formats, vary in quality, and lack descriptive metadata [36,67]. Subsets of Finnish parliamentary debates have been published before:

1. The FIN-CLARIN’s Language Bank1111 [41] contains the speech corpus 2008–2016 of linguistically annotated plenary debates and also links to the session videos [48].

2. The Voices of Democracy project has produced a research corpus that includes grammatically annotated plenary minutes in 1980–2018 as well as interviews of veteran MPs conducted by the PoF after 1988 [2].

3. The International Harvard ParlSpeech Corpus [62] contains speeches of the Finnish parliamentarians 1991–2015 but has gaps in the coverage.

Parliamentary data is used in many fields, such as linguistics, political science, legal studies, media studies, economics, and history. Parliamentary debates data combined with the political affiliation information of the speakers allows to study, e.g., (political) language and its use, legislative processes, political decision-making, and the debated societal issues (see for example [12,37]). Metadata and annotations make it possible to structure and differentiate the speeches, for example, between parties, gender, government-opposition role, or by professional groups, and to filter and analyse the speeches based on the annotated features. Parliamentary data also allows long-term studies as the data often extends over several decades or even a century [13].

Parliamentary debates have also been used in thematic and conceptual analyses (e.g., [10,13,26,29,31,60]) and to study the language and the opinions of the parties or MPs (e.g., [1,2,5,44,49]). The speech data have been used in translation studies using, for example, the EuroParl Corpus1212 of the European Parliament debates.

Several linguistic and social science studies have been conducted using debates of the PoF. La Mela [36], also Kettunen and La Mela [31], have studied the history of Nordic right of public access to nature, and examined the quality of the previous PoF open data. The digitized minutes have been utilized in the development of language technology methods [31]. Andrushschenko et al. [2] have used their grammatically structured corpus for selected digital humanities research cases. Simola [65] has explored the differences in political speech between parties in the long term (1907–2018), and Makkonen and Loukasmäki [47] have used topic modeling to study the plenary debates of PoF in 1999–2014. The FIN-CLARIN’s Parliamentary Corpus has been used, for example, by Lillqvist et al. [43] in their study on debates about public debt.

Previous applications of the Finnish parliamentary data cover only a small part of the entire time series of the Finnish parliamentary speeches. Data analysis tools to examine the results are few, such as the concordance analysis of the Language Bank Korp, where the words found are visualized in their textual contexts with statistics about word occurrences.

3.An ontology of the Parliament of Finland and its MPs

The data in ParliamentSampo consists of two core datasets, i.e., knowledge graphs (KG), that cover the lifetime of the PoF staring from 1907:

1. Ontology and data about the MPs and PoF A prosopographical knowledge graph called P-KG has been created for representing biographical data about all ca. 2800 Finnish MPs and other speakers in plenary sessions and their activities, and about related parties, groups, organizations, and other entities of the PoF. [42] We will call the data model of the P-KG as the PoF Ontology.

2. Speeches of Plenary Sessions This dataset contains all speeches of the Finnish parliamentary plenary debates since the PoF was established in 1907, totalling ca. 985000 speeches by the end of 2022. These data have been transformed into a Linked Data knowledge graph [67] called S-KG. In addition, the speech data have been published as CVS tables and using the XML TEI-based format Parla-CLARIN.1313 In addition, a subcorpus in ParlaMint format was created as part of the Pan-European ParlaMint II project.1414

The data transformation pipeline of ParliamentSampo contains accordingly two branches: one for creating the ontology and data about the politicians and the PoF [42] and one for transforming their speeches [9,66,67] into data.

This section describes the Ontology of PoF, i.e., the data model, and how it was populated with data instances in order to create the P-KG. The P-KG is used as a basis for the S-KG described later in Section 4.

3.1.How the Parliament of Finland works

The organization and activities of the PoF are is documented in [15]. Legislation procedures in PoF can be initiated today by a government bill (hallituksen esitys in Finnish), by a parliamentarian’s proposal (kansanedustajan esitys) of an MP, or as citizen’s initiative (kansalaisaloite). The process starts with referral discussion (lähetekeskustelu) that sends the bill to a committee in whose expertise domain the bill/proposal/initiative is related to. The committees consist of 17 or 21 MPs and vice members. At the moment, there are 16 permanent committees in PoF. Based on a report of the committee the parliament then has a first discussion about the legal document in question after which still some modifications to the document can be made. Later on there is a second discussion where the document is finally either accepted or rejected. There are hence usually three plenary sessions where a document is discussed. In addition to legislative matters, the PoF discusses in plenary sessions also many other matters, such as the state budget proposals and interpellons of the opposition parties.

The organizational structure of the PoF has evolved in time. Creating an overarching ontology over different times is a challenge due to the dynamic nature of the PoF: lots of parties, groups and other organizational units, have been established, restructured, and vanished since 1907. Reassembling the history of the POF from the documents available was deemed infeasible. Furthermore, it turned our that explicit descriptions of how the parliaments have worked in history were no readily available. We therefore created the PoF ontology in a data-driven fashion based on the data available concerning the MPs and other speakers in the plenary sessions and governments making the proposals [21].

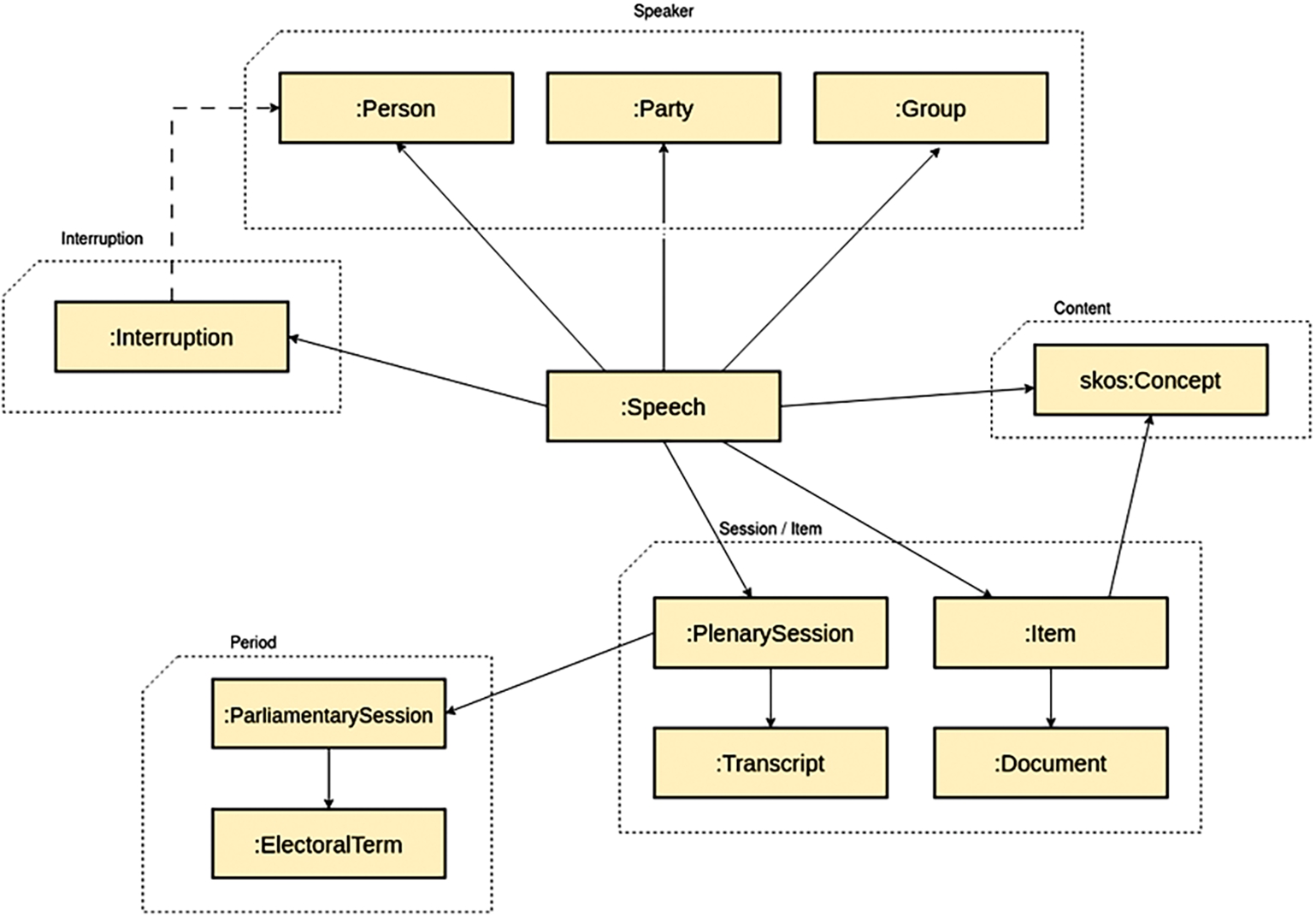

Fig. 1.

Pipeline of transforming data about the MPs and other speakers of the plenary sessions into the ontology of the PoF.

The data transformation pipeline for the P-KG is depicted in Fig. 1. The most important primary data source for creating the PoF ontology was the database of MPs provided by the PoF with some additional information from the Finnish Government web pages (on the left in the figure). It contains in a custom XML format biographical data about all MPs, such as date and place of birth, periods of time as an MP, electoral districts, memberships in parties, committees, other groups, and organizations, and publications of the MPs. From this data it was possible by using XML structures and Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Linking (NEL) to extract ontological classes for the PoF Ontology, such as electoral districts, parties, and committees, and at the same time populate the ontology with instances of people, committees, and other classes. Regular expressions worked well for NER and NEL was performed using custom Python scripting.

The XML data was first transformed into a CSV table people.csv. This data was then extended with data about ca. additional 200 speakers in the PoF that have not been MPs and therefore were not included in the MP database of the PoF. The needed additional data, including, e.g., family relations, events of personal biographical history, and photographs, was available from the open data sources of the Government,1515 BiographySampo.fi [20,70], and Wikidata.1616

3.2.Data model for parliamentary actors, groups, and events

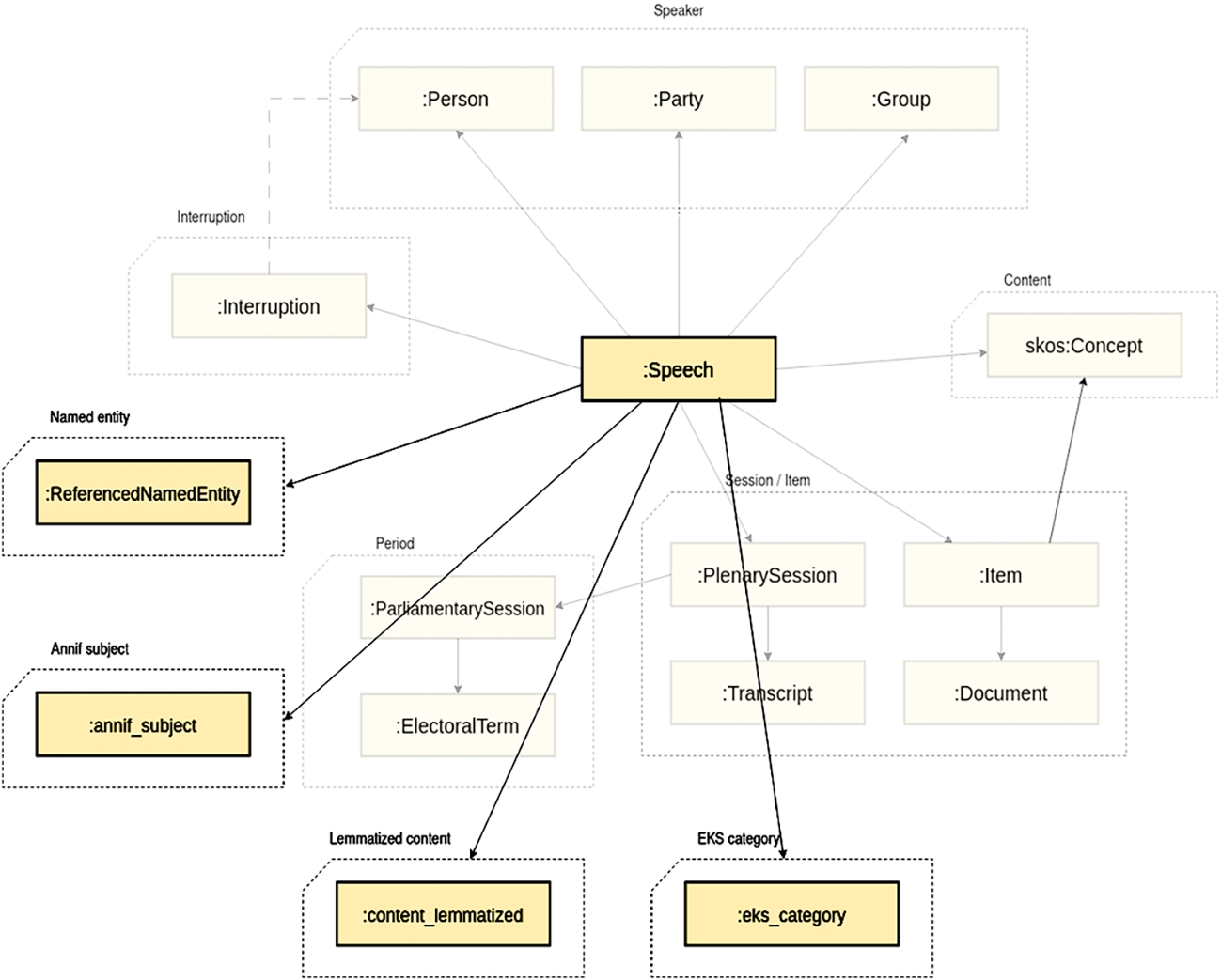

The data model of the PoF Ontology extracted from the data is presented in Fig. 2. It is based on the Bio CRM [74] ontology, an extension of CIDOC CRM1717 for representing biographical information based on role-centric modeling. Bio CRM makes a distinction between attributes, relations, and events, where entities participate in different roles in a qualified manner. The namespaces used in the model are described in the figure on the left.

The key idea of the model is to represent an actor’s activities as a sequence of events (bioc:Event) in places (crm:E53_Place) and in time (:Timespan) with the actors (bioc:Person) participating in different roles (bioc:Actor_Role), such as :Member, :Representative, etc.

There are almost 200 different roles in use in the PoF Ontology. The data model has been populated by the MP database and related sources as well as by using a set of external domain ontologies, such as places based on the ontology YSO Places,1818 groups and organizations (harvested from the data), and vocations based on the AMMO ontology [34]. Table 1 summarizes the number of instances of the main classes of the data model of Fig. 2, and Table 2 lists the number of different event types extracted.

Table 1

Resources

| Resource type | Count |

| Timespan | 10733 |

| Label | 6115 |

| Place | 4543 |

| Person | 2828 |

| Publication | 1727 |

| Vocation | 1456 |

| School, College | 670 |

| Parliamentary Group | 89 |

| Government | 76 |

| Committee | 54 |

| Organization | 54 |

| Electoral District | 46 |

| Party | 44 |

| Parliamentary Body | 38 |

| Ministry | 12 |

| Affiliation Group | 10 |

Table 2

Events

| Event type | Count |

| Career Event | 14756 |

| Position of Trust | 12788 |

| Committee Membership | 6669 |

| Municipal Position of Trust | 4740 |

| Event of Education | 3722 |

| Birth | 2828 |

| Parliamentary Group Membership | 2280 |

| Electoral District Candidature | 2211 |

| Death | 2071 |

| Government Membership | 1637 |

| Governmental Position of Trust | 1615 |

| Affiliation | 1397 |

| Parliament Membership | 966 |

| Honourable Mention | 537 |

| International Position of Trust | 364 |

| Membership Suspension | 25 |

3.3.Data quality and validation

The ontology was created in a data-driven fashion. This means that if the data misses something, say the membership of an MP in a particular committee at a time, then the list of members in that committee instance is incomplete. It is known that the data is not fully complete. For example, the MP database for some old committees record only their chairs, not ordinary memberships. Checking and analysing possible missing data has not been done systematically afterwards; it is assumed that the database is complete in this sense and that the user is aware about the fact that this may not always be the case. Validation could be done based on historical sources that, e g., provide lists of members in different committees in different times if such data can be found.

For validating the transformed data, the data model and its integrity constraints can be presented in a machine-processable format using the ShEx Shape Expressions language.1919 We have made initial validation experiments with the PyShEx2020 validator. Based on the experiments, we have identified some errors both in the schema and the data. We plan a full-scale ShEx validation phase integrated in the data conversion and publication process to spot and report errors in the dataset.

3.4.PoF ontology available online

The linked data is available on the LDF.fi platform as separate graphs interlinked with the S-KG in a SPARQL endpoint.2121 The PoF Ontology with instance data are also available as RDF Turtle files on Zenodo.org2222 using the CC BY 4.0 license. In addition, the central CSV data file people.csv about the MPs and other speakers in the plenary session are available at the national CSC Allas data store2323 and is updated on a daily basis.

The data can be downloaded also through the ParliamentSampo portal that includes tools for CSV download, too. In this way the CSV data can be filtered before downloading using the faceted search engine of the portal. For example, only data about the people of a particular party during a period of time can be downloaded.

4.Speech data of plenary sessions

This section describes the data model of the Speech Graph S-KG and how it was transformed from the mostly textual plenary session minutes from different times.

4.1.Transformation pipeline for speech data

The plenary discussions in PoF consist of sessions where particular topics or proposals, such as bills of government, are discussed. Each session consists of a series of speeches of six different types, such as Speech of the Speaker, Group Speech, and Regular Speech.

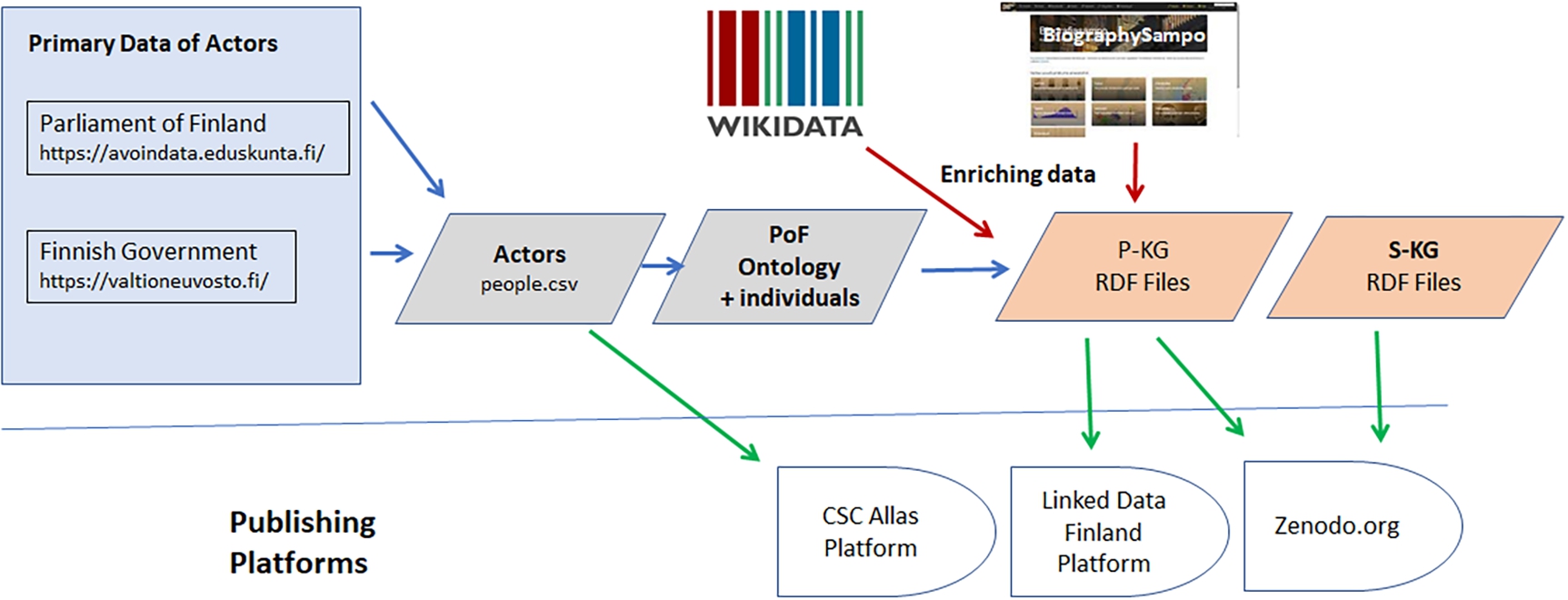

Fig. 3.

Pipeline for transforming the minutes of plenary sessions into speech data.

Figure 3 illustrates the process used for transforming the minutes of the plenary sessions into datasets and data services on different publishing platforms. The data is first transformed into simple literal data CSV tables that are published using the national CSC Allas data store.2424 The CSV format can be of use for DH researchers developing and using their own tools, and this data publication also serves as the primary source for publishing semantically richer versions of the data. The CSV data is then enriched into Parla-CLARIN XML TEI2525 form that includes, e.g., identifiers for the speakers, and into ParlaMint format where additional linguistic annotations pertaining to, e.g., named entities in the texts are explicated. Also a ParlaMint subcorpus has been created and published as part of the larger collection European ParlaMint corpora provided by the ParlaMint platfrom2626 [11]. The semantically richest publication form of the data is the RDF 1.1. Turtle2727 version. This publication combines the KGs of speech data and the related P-KG of prosopograhical data, based on the PoF Ontology enriched with additional data from external sources (cf. Section 3). This data has been published as data dumps on the Allas Store and Zenodo.org, and as a LOD service on the Linked Data Finland platform2828 [25], including a SPARQL endpoint, content negotiation of URIs, linked data browsing, and other services. When enriching the CSV tables into XML and RDF formats, also the interruption markup in the speeches is extracted from the text and transformed into structured forms that can be used in data analyses.

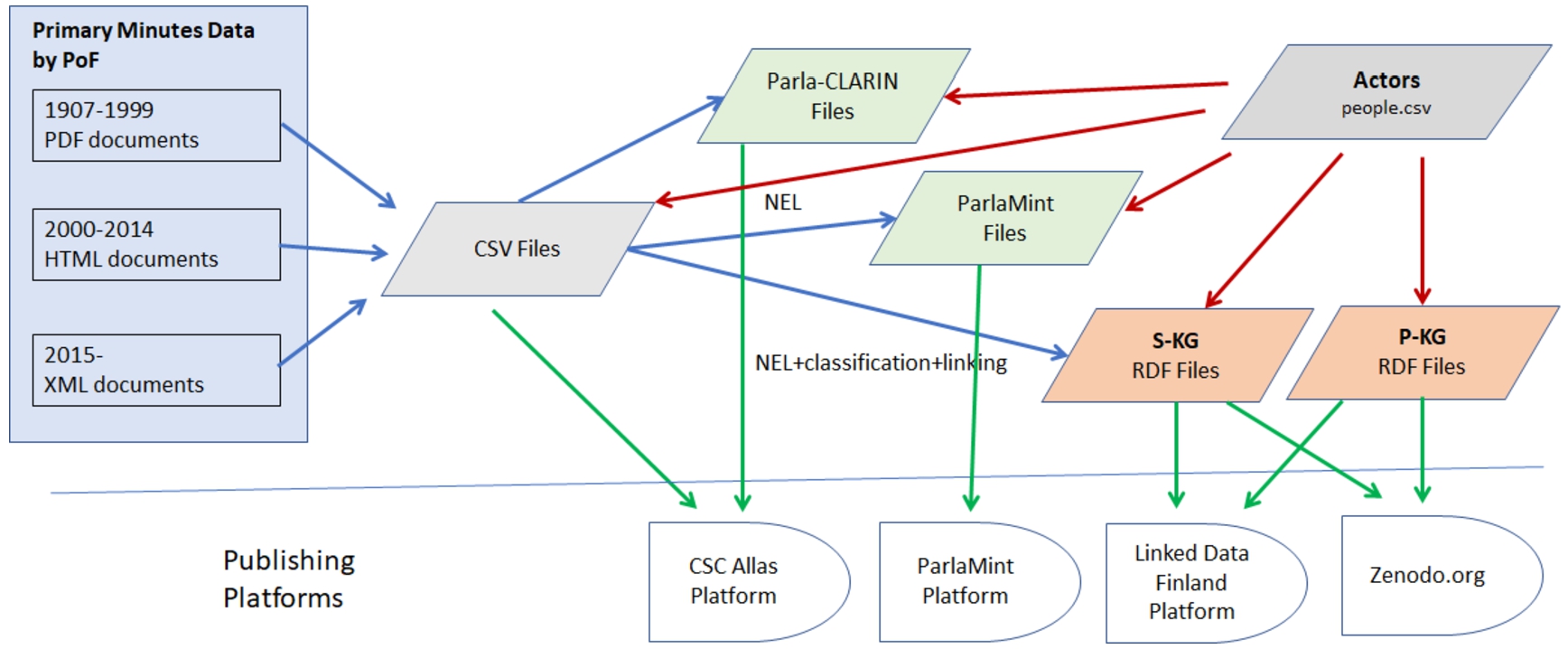

Fig. 5.

Data model for the linguistic annotations of speech data 2015– in the default namespace https://ldf.fi/schema/semparl/, with the related speech data model in the background.

The data model of S-KG is depicted in Fig. 4. The speeches of the latest and best quality dataset 2015– have been annotated with extracted named entities, keywords, and topical categories, and the data also includes lemmatized versions of the speeches. The data model for these annotations can be seen in Fig. 5. More documentation about the S-KG data model can be found in [66,67], on the Linked Data Finland platform homepage of ParliamentSampo, and by using the namespace URL in a browser.

4.2.Speeches as CSV tables

In the transformation process the minutes are first transformed into simple textual CSV files. The rationale for producing and publishing CSV tables is that they can be used easily by spreadsheet programs for analysing the data and by using various computational methods. From a computational point of view, the CSV data can be created automatically because no advanced data processing, such as named entity linking, is included in process. The only exception to this are the URI identifiers for the speakers and parties that are extracted from the Actors file people.csv (cf. Fig. 3 on the right) based on the PoF Ontology. The CSV is also a useful format for checking and correcting errors in the results of data transformations, such as OCR errors. An example of another national parliament corpus that makes use of CSV and TSV formats is the Talk of Norway (1998–2016) [39].

The speech data comes from three sources and formats depending on the time of the plenary session:

1. Corpus 1907–1999 The older plenary session minutes were available only in PDF format.2929 These documents, often over thousand pages long, have been created by the PoF who has digitized the printed minutes books of all plenary sessions.

2. Corpus 1999–2014 From halfway 1999 to the end of 2014, the minutes were available also in already structured HTML form at the PoF’s web pages.3030 The HTML documents were transformed into CSV tables.

3. Corpus 2015– The plenary session minutes from 2015– are available also based on a custom-made XML schema from the Avoin eduskunta API.3131 These XML documents were transformed into the CSV tables.

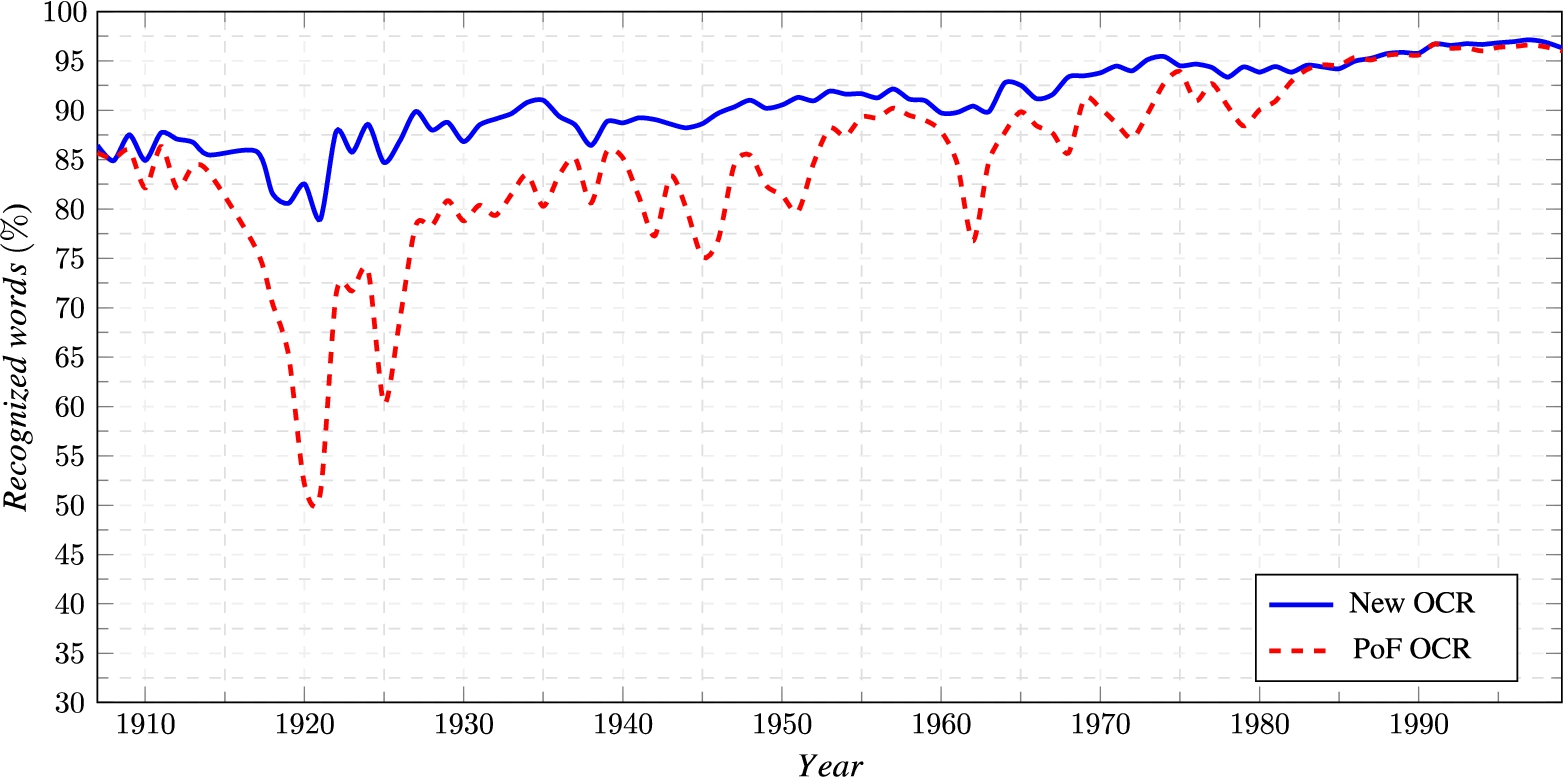

Fig. 6.

The percentage of recognized words with LAS tool using original PoF OCR (red dashed line) and our new OCR (blue line) results.

In order to extract their textual contents, we re-OCRed the PDF documents of the Corpus 1907–1999 using multilingual Deep Neural models, as presented in [9]. Figure 6 shows the percentage of recognized words across the whole documents with the Language Analysis Command-Line Tool (LAS) [45] using the original PoF documents and our new OCR results. The new OCR results are consistently better than the original PoF version, with the biggest improvement for the material from 1920s, which is the most challenging period of time due to poor paper quality. The words are recognized on multilingual datasets using only Finnish morphology so they do not show the absolute word accuracy rate, which is estimated to be in the 98–99 % range for Finnish text [9]. Finally, long documents were split into 1–8 separate PDF files, each containing the minutes for several plenary sessions. The extracted texts were structured by Python scripting into the set of CSV tables.

Fig. 7.

OCR example. On the left is a part of the original PDF-document; on the right is the same part with recognized text. [66].

![OCR example. On the left is a part of the original PDF-document; on the right is the same part with recognized text. [66].](https://content.iospress.com:443/media/sw-prepress/sw--1--1-sw243683/sw--1-sw243683-g007.jpg)

Figure 7 shows an example of the original minutes for a plenary session on the left. In general, the minutes consist of items (or topics), marked here in bold (except the row Keskustelu: (debate/conversation)). The item header is followed by (1) a possible list of related documents, (2) chairman’s opening comments, (3) possible debate section marked by Keskustelu: (debate/conversation), and (4) finally a decision and a closing statement. Also the later minutes available in structured HTML and XML formats mostly follow this layout and logic.

Each source corpus 1–3 format differs in terms of the metadata included in the minutes. However, all formats contained the following core metadata elements about the session, speaker, and the speech: (1) Session data: session identifier, session date, session ending and starting times (2) Speaker data: last name, speaker’s role/title (3) Speech data: speech content, speech type, related documents, and debate topic. In the final speech CSV tables, each row contains an individual speech with the content and metadata elements represented in columns.

The structure of the CSV Tables 1907–1999 and the CSV tables based the HTML-formatted minutes in 2000–2014 are fairly similar with over 20 metadata fields, such as speech identifies, session, data, start and end times, name of the speaker, his/her party and so on. The CSV table format based on the XML files 2015– contains the following columns for metadata about speeches: party, topic, content, speech_type, status, version, link, lang, name_in_source, speaker_id, speech_start, speech_end, speech_status, and speech_version. More documentation about the data can be found at the Allas Store site.

In addition to metadata about a speech, the speech text itself contains mark-up metadata about possible interruptions of the speech using a special bracketed notation. In data 1907–1999 interruptions are marked with parentheses “(interruption text)” and after that with brackets “[interruption text]”. The interruptions are made by other people during the speech and in many cases the minutes also tell who made the interruption. For example, text “... nostamiseksi [Arto Satosen välihuuto] hallitusohjelman ...” means that MP Arto Satonen made an interruption (shouted something) at this point of a fellow speaker’s speech. In the CSV data the marked interruptions are left intact in texts but were extracted as new metadata that can be used in data analyses during the next data processing steps.

The practises on how minutes of plenary sessions should be recorded are described in a lengthy 147-page document of the Minutes Office of the PoF (“pöytäkirjatoimisto” in Finnish) [32]. It is not fully known what kind of changes in practice there have been at different times. These changes may have implications on data analyses in some cases. For example, in 2021 it was decided that if the speaker only gives the floor to the next speaker without other content in his/her speech, then this is not recorded as a distinct speech of the speaker for simplicity. If the number of all kind of speeches in different times is analyzed, a change in the recording practise of course may skew results statistically.

The CSV tables are published as files that were created on a parliamentary session basis, one file per parliamentary session (valtiopäivät) with the name speeches_YEAR[_N].csv, where YEAR = 1907, 1908, …and [_N], N = II | XX is optional. For example, the speeches from 1925 are in the file speeches_1925.csv. However, occasionally there have been two parliamentary sessions referring to the same calendar year.3232 For example, the speeches from the first parliamentary session of 1918 are in the file speeches_1918.csv and speeches from the second parliamentary session are in speeches_1918_II.csv. The years 1915 and 1916 are missing because the PoF did not convene then due to the World War I. In 1917 between first and second parliament, two unofficial meetings were held. These meetings have been given (originally lacking) order numbers for the sake of itemization. Files containing data from these meeting are marked by _XX.

The CSV tables are available openly under the CC BY 4.0 license at the Allas data repository.3333 The folder there includes (1) a zip file that contains the CSV data files of all parliamentary sessions, (2) the parliamentary session files as separate CSV files, and (3) a link to documentation. The last file of the current parliamentary session is updated daily. The CSV data of the past years is stable but can be updated on an irregular basis when, e.g., OCR errors etc. are found in the data. Information about the updates will be stored in the readme.txt file stored in the same folder as the CSV files. As new minutes are published by the PoF on their data service, the CSV table of the current year is updated automatically on a daily basis with the new speeches.

4.3.Speeches in Parla-CLARIN and ParlaMint formats

The XML TEI-based Parla-CLARIN [11] schema is an attempt to define a common XML-based annotation model for parliamentary debates on an international level.3434 For example, the Slovene parliamentary corpus siParl (1990–2018) has been encoded with the Parla-CLARIN schema [55]. Currently, the Parla-CLARIN schema is implemented in the ParlaMint project,3535 which establishes a comparable and interoperable corpus of European parliamentary corpora for comparative research. This format is a specialization of Parla-CLARIN extending it with, for example, linguistic and named entity mention annotations.

Parla-CLARIN format includes not only speeches but also means for representing data about the context of the debates including data about the speakers, parties, related organizations, and places in a systematic way using XML identifiers for cross-reference. A benefit of using XML-based formats is the possibility of validating documents syntactically based on their schema definition.

The Parla-CLARIN version of the ParliamentSampo speeches is available at the Allas data store using a file system similar to that of the CVS tables.3636 The ParlaMint subcorpus is available at the ParlaMint data repository.3737

4.4.Publication as Linked Open Data

The LOD version of the speech data was created from the CSV tables, too [66,67]. The latest corpus 2015– has been annotated semantically using Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques as discussed in [69]:

1. Named Entity Linking. Mentions of the MPs and places were extracted, disambiguated semantically, and linked to corresponding resources with URIs in the PoF Ontology data. These annotations facilitate, e.g., network analyses on MPs and parties based on mutual references in speeches as discussed in [56–58].

2. Automatic keyword annotation. Finnish NLP technology was applied also for annotating the speeches automatically using the YSO ontology3838 [64] of the National Library of Finland and the Annif automatic annotation tool3939 [68]. Ontology-based keywords facilitate semantic search and content-based analyses of the speeches. The data includes also keywords extracted using the traditional TF-IDF method.

3. Automatic topical library classification. The EKS subject headings4040 vocabulary of the Library of Parliament and Archive of Parliament was transformed into a SKOS4141 ontology, and the sessions were indexed automatically based this. EKS subject headings annotations facilitate hierarchical topical classification of the sessions and their speeches.

4. Linguistic data. The data also includes additional linguistic analysis data, such as lemmatized versions of the speech texts.

In the S-KG, the speeches of the most recent parliamentary term 2019–2022 were automatically classified using the EKS categories. These categorizations are not exclusive but multi-label: a document may belong to different categories. In order to carry out the classification, the keywords were used as the basis for the internal text representation of the system, as described in more detail in [40]. The keywords were transformed into word embeddings via the corresponding pre-trained fastText model [50], which are then pooled together to create the document representation. The NLP-based annotations have been published as part of the ParliamentSampo RDF Turtle data dump in Zenodo.org4242 and as linked open data on the Linked Data Finland platform.4343

5.Using the ParliamentSampo data

This section discusses briefly different ways of using the ParliamentSampo infrastructure described above.

5.1.Exporting the data for external use

A simple way for a researcher to use ParliamentSampo data is to download it from the data services presented above for local use, and then apply one’s favourite tools for data analysis, such as spreadsheets, R4444 environment for statistical analysis, or Gephi4545 for network analysis. For filtering subsets of interest in the big data, SPARQL querying can be used in flexible ways. It is also possible to install a local SPARQL server for linked data on one’s own computer, for example Fuseki,4646 which is also used in the LDF.fi service. The materials in the LDF.fi service are published using container technology (i.e., Docker4747), which means that installing the data, the server, and possible versioned software packages is automatic and effortless.

An example of using the ParliamentSampo data externally is reported in [10]. For this case study in political science, the Parla-CLARIN version was downloaded and a subset of the speeches 1960–2020 was filtered and analyzed further using custom XML-based tools. The authors studied how the language used in discussing environmental politics has evolved in Finland in the speeches of different parties. Eleven central environmental terms were selected from the EKS subject headings thesaurus, speeches where these terms were used were then extracted, and various quantitative analyses based on them were presented and compared with the strategy plans of the parties with qualitative interpretations. The analyses showed, for example, a constantly increasing intensity of environmental debates and a rhetorical shift of language from protecting the nature to issues of climate change.

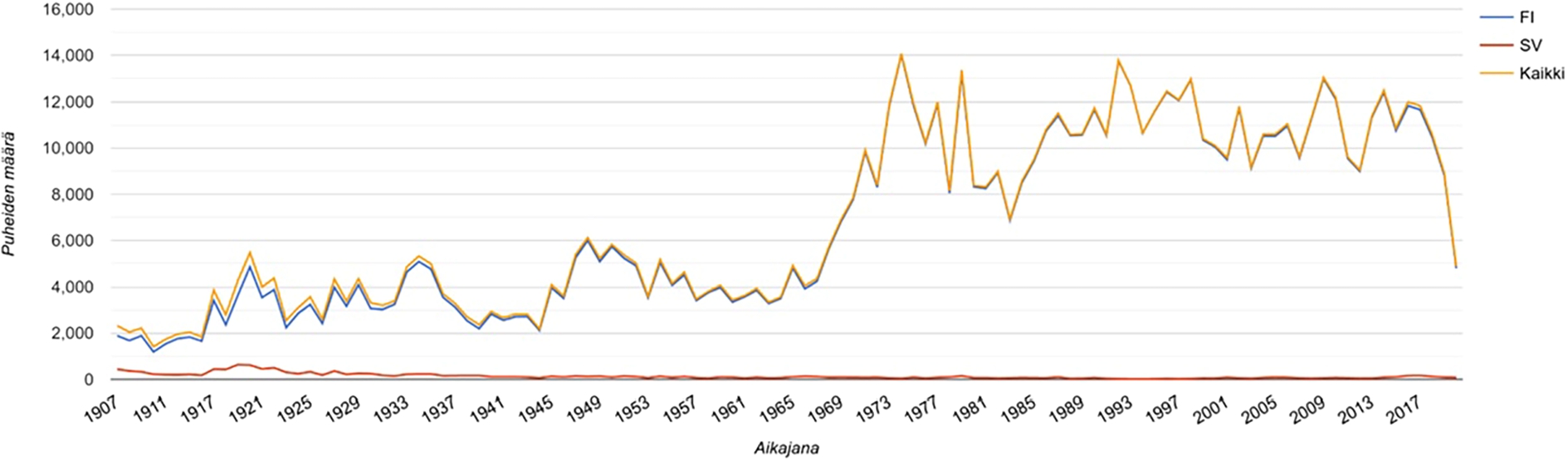

Fig. 8.

Number of speeches in different languages (y-axis) on the timeline (x-axis).

5.2.Querying the endpoint and studying results

SPARQL is a flexible way to query RDF data. The search result is presented in a tabular format that can be examined as it is and be visualized and used for application-specific analyzes. For example, Fig. 8 shows a visualization of the number of Finnish (FI), Swedish (SV) and all (Kaikki) speeches (y-axis) in the S-KG graph on a timeline from 1907 to 2021 (x-axis). Before the WW2, there have been more speeches in Swedish than today, but the number remains very small. The graphic was created using the Yasgui editor4848 [63], which can be used to edit SPARQL queries, target them to an online SPARQL endpoint, and to show the results using visualizations.

5.3.Data-analysis by scripting

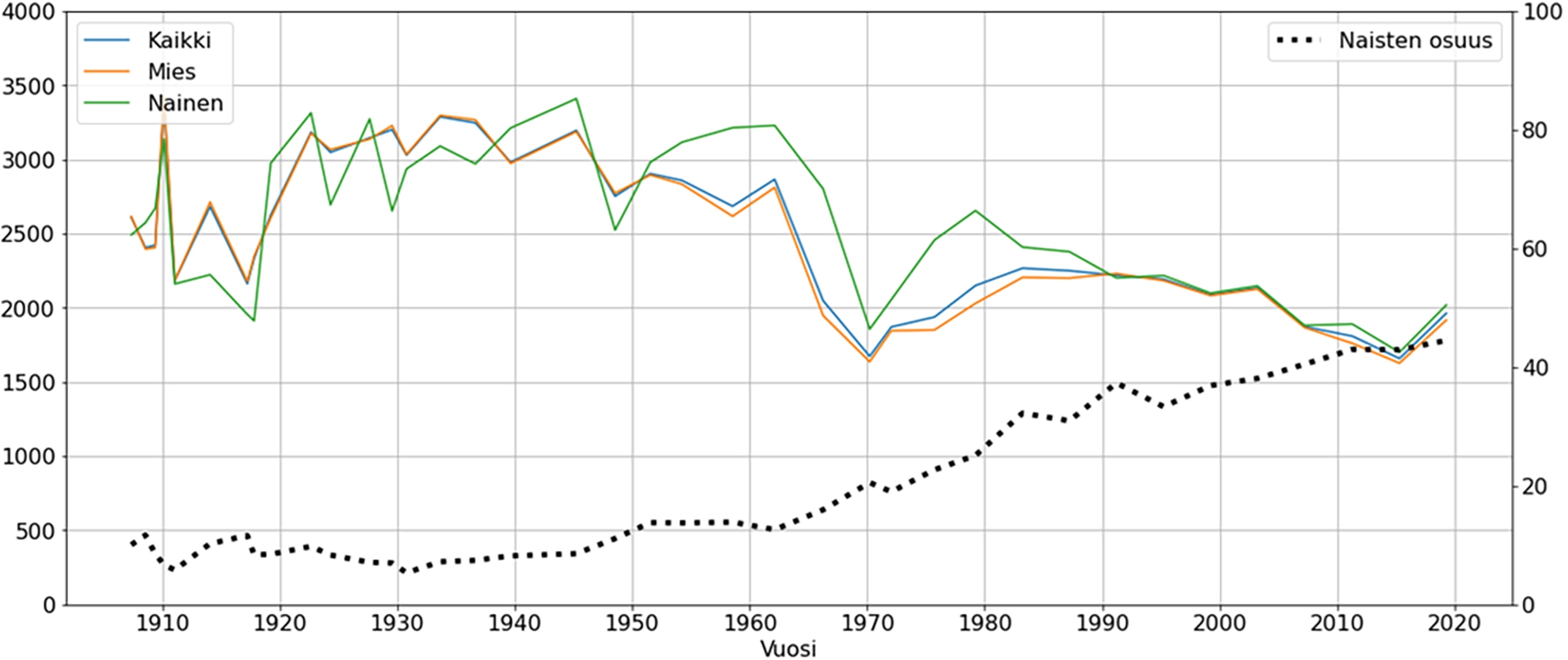

Fig. 9.

Average annual lengths of all (kaikki), male (mies), and female (nainen) speakers, and the raising proportion of speeches by female speakers (naisten osuus).

The PoF data can be examined computationally using, for example, Python scripting and Jupyter notebooks in the Google Colab4949 environment. Then one can use the simple HTTP protocol to perform SPARQL queries and after this analyze and visualize query results using tools provided by the programming environment, e.g., by Python libraries. An example analysis of using Google Colab is presented in Fig. 9. It shows the yearly (x-axis) average lengths (y-axis) of speeches of all speakers (Kaikki), male speakers (Mies), and female speakers (Nainen), as well as the raising proportion of speeches by female speakers (Naisten osuus).

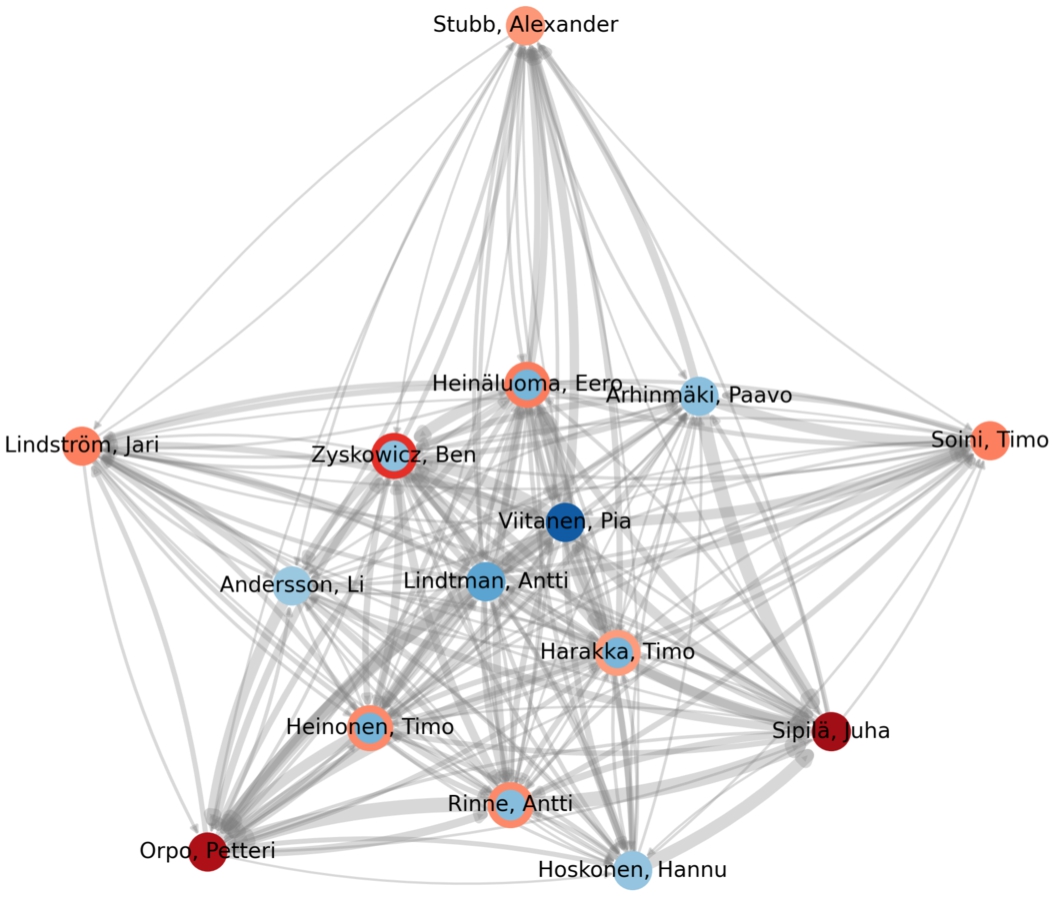

Fig. 10.

Ten MPs with highest hub and authority values based on the HITS algorithm. The darker red, the larger authority value, and the darker blue, the larger hub value.

In [57], examples of analysing networks of MPs referencing to each other in their speeches during the electoral term 2015–2019 were given using the Python package NetworkX [14]. Such a reference network has MPs as nodes and arcs point from the speaker to the mentioned person. The weight of the link corresponds to the total number of speeches with at least one mention. The network has in total 214 MPs that have been mentioned or have mentioned someone. The total number of mentions to other MPs extracted from the speeches is over 25000. Mentions of people who were not MPs or ministers at the chosen electoral term were filtered out of the result set. Analyses of this kind of reference networks can reveal, e.g., most active and influential MPs in parliamentary debates and help to recognize possible disputes between MPs or parties.

To study and visualize the network, hub and authority values were calculated using the HITS algorithm [33]. Ten MPs with highest authority values and ten nodes with highest hub values are shown in Fig. 10. From the MPs with the highest authority values, Juha Sipilä, Timo Soini, and Petteri Orpo were ministers and leaders of their parties during the 2015–2019 term. During the same years, Jari Lindström was also a minister and Antti Rinne from the opposition served also as leader of his party. Five MPs, Eero Heinäluoma, Timo Harakka, Timo Heinonen, Pia Viitanen, and Ben Zyskowicz, are both top hubs that make references as well as top authorities often mentioned by other MPs. None of the MPs with highest hub values were ministers.

5.4.Developing applications on top of the LOD service

The ParliamentSampo data service adopts the 5-star Linked Data model,5050 extended with two more stars, as suggested in the Linked Data Finland model and platform [25]. The 6th star is obtained by providing the dataset schemas and documenting them. The ParliamentSampo schema can be downloaded from the service5151 and the data model is documented using the LODE service.5252 The 7th star is achieved by validating the data against the documented schemas to prevent errors in the published data. ParliamentSampo attempts to obtain the 7th star by applying different means of combing out errors in the data within the data conversion process. The ParliamentSampo data model and its integrity constraints are presented in a machine-processable format using the ShEx Shape Expressions language5353 [72]. We have made initial validation experiments with the PyShEx5454 validator. Based on the experiments, we have identified errors both in the schema and the data, and a full-scale ShEx validation phase for the data conversion is underway.

The Linked Data service is powered by the Linked Data Finland5555 publishing platform that along with a variety of different datasets provides tools and services to facilitate publishing and re-using Linked Data. All URIs are dereferenceable and support content negotiation by using HTTP 303 redirects. The data is available as an open SPARQL endpoint.5656 As the triplestore, Apache Jena Fuseki5757 is used as a Docker container, which allows efficient provisioning of resources (CPU, memory), portability, and scaling. Varnish Cache web application accelerator5858 is used for routing URIs, content negotiation, and caching.

The data services and the SPARQL endpoint can be used for developing applications. To investigate and test these opportunities, the semantic portal ParliamentSampo discussed in the next section was developed using the open SPARQL endpoint.

6.The ParliamentSampo portal

The ParliamentSampo portal5959 is based on the Sampo model [17] and the Sampo-UI framework [27,61]. The idea here is to demonstrates how the SPARQL data service can be used for developing applications for Digital Humanities research. In the portal, the data can be filtered using faceted search [75] based on ontologies, and the results can then be analyzed with the help of seamlessly integrated visualizations and data analytic tools. The data can be accessed along application perspectives for studying (1) speeches in different times and (2) the MPs and other speakers of PoF, based on the interlinked knowledge graphs S-KG and P-KG, respectively.

6.1.Application perpectives for speeches and MPs

Based on the Sampo-UI framework, the landing page of the portal contains application perspectives through which instances of the classes of the underlying KGs can be searched and studied [27]. In this case, there are perspectives for speeches and people. Their instances can be searched using faceted search and after filtering a subset of interest (1) individual instances can be studied by looking at their homepages or (2) the whole subset can be analyzed as a whole. In both cases, a set of tabs are available for visualizing or analyzing the instance (a speech or person) or a set of them, say the speeches of MPs belonging to a party during a certain time period.

Fig. 11.

Using faceted search to filter and analyze speeches about NATO.

For example, in Fig. 11 the user has selected the Speeches perspective. Ten search facets, such as Content, Speaker, Party, (Speech) Type are available on the left. The search result, i.e., the speeches found, is shown by default in traditional tabular form on the right, but the result can also be visualized in other forms by selecting one of the five tabs on the top. Here the timeline visualization (AIKAJANA) is used. The user has written a query “NATO*” in the Content text facet, the speech type facet is set to regular speeches, and then 3622 regular speeches that mention the word “NATO” in its various inflectional forms have been filtered into the search result starting from 1959. In addition to the timeline visualization, by clicking on the pie chart visualization button on the Party facet, the distribution of NATO speeches in terms of parties is shown: the most active party with 722 speeches has been the right wing National Coalition Party Kokoomus.

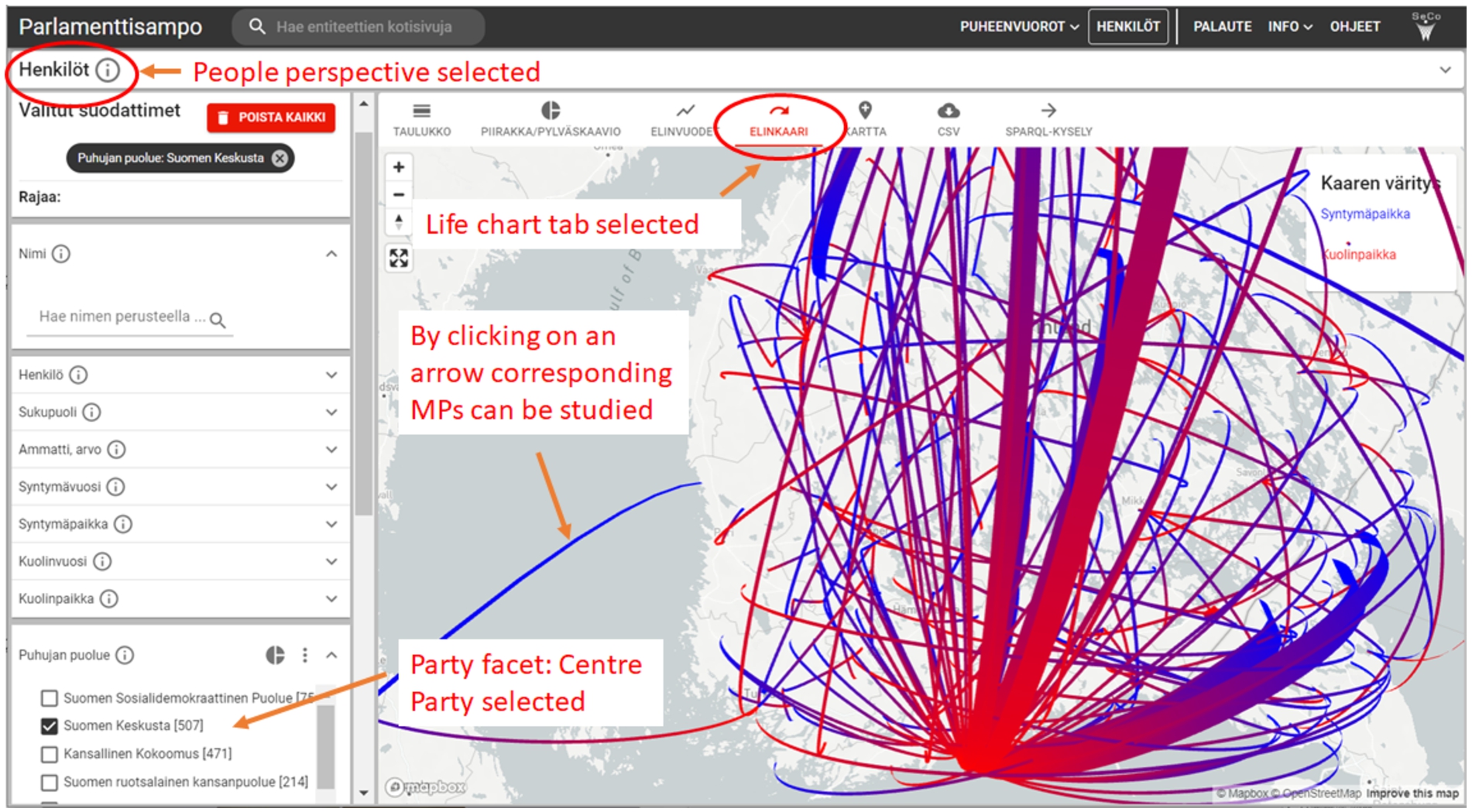

Fig. 12.

Using faceted search to study MPs, here using life charts of the members of the Centre Party from their places of birth to places of death.

A similar kind of application perspective with faceted search and tabs for visualizing the results is available for studying the MPs. Here 16 facets, such as Name, Gender, Party, Occupation etc. are available for filtering a target group of MPs and other speakers that can then be visualized on tabs as a result table (TAULUKKO), using statistic pie charts and histograms (PIIRAKKA/PYLVÄSKAAVIO), using a timeline of births and deaths of the people (ELINVUODET), by life charts on maps (ELINKAARI), or by showing events related to the speakers on a map (KARTTA). In Fig. 12, the facets are shown on the left and the result set on the different tabs on the right. Here the 507 members of the Centre Party were selected using the facet Party of the Speaker (Puhujan puolue) on the left and the life chart visualization tab is used. It shows arcs from the places of birth of the speakers (blue end) to places of death (red end). The MPs of this party, focusing on country side farming matters, have clearly moved from all over Finland to Helsinki for their old age. By clicking on an arc, links to the homepages of the corresponding people can be found for close reading.

One user group of a system like ParliamentSampo is media. Now it is possible to easily find out and analyze what the politicians have actually said in the Parliament and also give links to particular speeches of interest for immediate close reading. This possibility may in the future have an effect on political speech culture. For example, several journalists of the leading Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat have recently published the following articles (in Finnish) based on ParliamentSampo, involving discussions related to, e.g., gender balance and racist speeches:

– Sonia Zaki: Nearly million speeches. The most active members of the Parliament have given amazingly many speeches. Here they are. (Melkein miljoona puhetta. Eduskunnan puheliaimmat kansanedustajat ovat pitäneet täysistunnoissa hengästyttävän määrän puheita. Tässä he ovat.) Helsingin Sanomat, June 26, 2022.6060

– Veera Paananen: Even if the Parliament has been equalized the men interrupt other speakers much more often than women. (Vaikka eduskunta tasa-arvoistui miehet keskeyttävät muita puhujia yhä paljon enemmän kuin naiset.) Helsingin Sanomat, Dec. 26, 2022.6161

– Veera Paananen: Minister Ville Tavio has spoken about population change many time at the Parliament. (Ministeri Ville Tavio on puhunut väestönvaihdosta useita kertoja eduskunnassa.) Helsingin Sanomat, July 3, 2023.6262

– Alli Hallonblad: Members of the True Finn party have spoken about Islam and Africa much more often than members of the other parties. (Perussuomalaiset ovat puhuneet islamista ja Afrikasta eduskunnassa huomattavasti enemmän kuin muut puolueet.) Helsingin Sanomat, Aug. 7, 2023.6363

6.2.Implementation

The portal UI was implemented using a new declarative version of the Sampo-UI framework6464 [61]. Here the UI with its components can be created on top a SPQRQL endpoint by using only SPARQL to access the data and with little programming by using a set of configuration files in JSON format in three main directories: (1) configs. JSON files configuring the portal and its perspectives. (2) sparql. SPARQL queries referred to in the configs files. (3) translations. Translations of things like menu items and labels for different locales. When creating a new UI configuration, existing UI components, such as those for the facets and visualization tabs, can be re-used, and the system can also be extended with new components. Sampo-UI has been found efficient and handy to use in practise, and it has been used to create some 15 portals in the Sampo series6565 [17] of LOD systems.

7.Discussion and future work

This paper presented, discussed, and illustrated principles for publishing and using parliamentary textual and prosopographical data as Linked Open Data, using the PoF as a case study. The first experiments of using the data presented are promising in filtering patterns of possibly interesting phenomena in Big Data using distant reading [52]. However, traditional close reading by a human is needed as before in interpreting the results. The system presented provided several novelties in relation to the related works discussed in Section 2.

A major challenge in creating data analyses like the ones shown in this paper is related to the quality of the data produced. Historical (meta)data can be incomplete and our knowledge about it is uncertain. Also using more or less automatic means for transforming and linking the data leads to problems of incomplete, skewed, and erroneous data [46]. This as well as difficulties in modeling complex real world ontologies become sometimes embarrassingly visible when using and exposing the knowledge structures to end-users. For example, it is difficult to categorize historical occupations and historical places as they change in time, and the methods of network analysis can be very sensitive to even small errors in the data or biases in the sampling schemes. The same problems exist in traditional systems but are hidden in the non-structured presentations of the data. In general, more data literacy [35] is usually needed from the end-user when using data analytic tools.

The ParliamentSampo datasets make it possible to find and study the speeches of the plenary debates of PoF as well as data about the speakers and other entities in the PoF. For the first time, a “machine-understandable” data corpus covering the whole history of the PoF since 1907 including nearly million speeches and over 2800 parliamentarians has been created and published openly as harmonized enriched open data with data services. Usefulness of the datasets and services has been demonstrated by using them in data analyses and by implementing the ParliamentSampo portal in use that demonstrates how the data can be used for application development.

In traditional close reading, the researcher is forced to delimit the data studied on, e.g., temporal or thematic grounds. Digital methods applied to big data, such as that of the ParliamentSampo, make it possible to study political culture and language without such limitations. For example, new themes and topics can be identified automatically or semi-automatically (e.g., [51,71]) and the language of politics and its long-term changes can be studied (e.g., [8,28,38,47,53,59,73]). Furthermore, by linking the speeches to data about the parliamentarians and their activities and other entities in the PoF and beyond, the social contexts of language users, such as education, gender, age, and social networks can be studied (e.g., [30,56,58]).

Planned future development of ParliamentSampo includes using and extending the system in parliamentary research studies, correcting the historical data based on user feedback that is collected, e.g., using the portal, validating the data using ShEx shape expressions,6666 and maintaining the data services as part of the national FIN-CLARIA/DARIAH-FI research infrastructure program.6767 Continuous updates to the data are needed, for example, after elections and other changes in the MPs and other speakers in the parliament.

The ParliamentSampo data does not contain the committee reports or other background materials. However, these have been published by the PoF electronically or in print as part of the minutes, and are also processed in the Lakitutka project.6868 ParliamentSampo data already includes links to Lakitutka contents when available. ParliamentSampo data does not contain the final statutes (legislation) either, but they are being published by the Finlex and LawSampo6969 systems [24] to which links are already provided. The system includes also links to more recent materials published by the PoF, such as video recordings of the plenary sessions.

In this paper, Finnish parliamentary data was used as a case study. However, the approach, methods, tools, and lessons learned presented are more general and can be re-used and adapted also to other parliamentary datasets in other countries in the future, and on an international level for, e.g., publishing and studying the speeches and other data of the European Parliament.

Notes

1 The whole ParliamentSampo project is presented at the homepage https://seco.cs.aalto.fi/projects/semparl/en/.

2 Open data services of the PoF: https://avoindata.eduskunta.fi/#/fi/home.

3 FAIR Data principles: https://www.go-fair.org/.

4 This paper got the Best Paper Award in the International Workshop on Knowledge Graph Generation from Text (TEXT2KG) Workshop co-located with the ESWC 2023 conference.

5 Publication event homepage: https://seco.cs.aalto.fi/events/2023/2023-02-14-parlamenttisampo/.

13 Parla-CLARIN homepage: https://github.com/clarin-eric/parla-clarin.

24 Allas Store: https://a3s.fi/parliamentsampo/speeches/csv/index.html.

29 Parliament of Finland open data: https://avoindata.eduskunta.fi/#/fi/digitoidut/download.

31 Open PoF API: https://avoindata.eduskunta.fi/#/fi/home.

32 Due to the Government resigning prematurely and thus starting a new parliamentary session.

37 See the current ParlaMint 2.1 version http://hdl.handle.net/11356/1432.

41 Simple Knowledge Organization System: https://www.w3.org/TR/skos-reference/.

59 Available at: https://parlamenttisampo.fi.

64 Sampo UI open code and documentation: https://github.com/SemanticComputing/sampo-ui.

65 For a full list of Sampo systems see: https://seco.cs.aalto.fi/applications/sampo/.

68 Lakitutka portal: https://lakitutka.fi/.

69 Available at: https://lakisampo.fi.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Esko Ikkala, Mikko Koho, and Minna Tamper for their contributions in the ParliamentSampo project earlier. Fruitful collaborations and discussions with Kimmo Elo, Jenni Karimäki, and Anna Ristilä of the University of Turku, Center for Parliamentary Studies, are acknowledged regarding the use cases and research on parliamentary culture. ParliamentSampo is based on the open data from the PoF: thanks to Ari Apilo, Sari Wilenius, and Päivikki Karhula of PoF for collaborations. Our work was funded by the Academy of Finland in the projects Semantic Parliament7070 and FIN-CLARIAH,7171 as well as by CLARIN.eu in the ParlaMint II project.7272 Our work is also related to the EU project InTaVia7373 and the EU COST action Nexus Linguarum7474 on linguistic linked data data resources and analysis. Thanks to Finnish Cultural Foundation for the Eminentia Grant of the first author. The project used the computing resources of the CSC – IT Center for Science.

References

[1] | G. Abercrombie and R. Batista-Navarro, Sentiment and position-taking analysis of parliamentary debates: A systematic literature review, Journal of Computational Social Science 3: ((2012) ), 245–270. doi:10.1007/s42001-019-00060-w. |

[2] | M. Andrushchenko, K. Sandberg, R. Turunen, J. Marjanen, M. Hatavara, J. Kurunmäki, T. Nummenmaa, M. Hyvärinen, K. Teräs, J. Peltonen and J. Nummenmaa, Using parsed and annotated corpora to analyze parliamentarians’ talk in Finland, Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 185: (1) ((2021) ), 1–15. doi:10.1002/asi.24500. |

[3] | K. Beelen, T.A. Thijm, C. Cochrane, K. Halvemaan, G. Hirst, M. Kimmins, S. Lijbrink, M. Marx, N. Naderi, L. Rheault, R. Polyanovsky and T. Whyte, Digitization of the Canadian parliamentary debates, Canadian Journal of Political Science 50: (3) ((2017) ), 849–864. doi:10.1017/S0008423916001165. |

[4] | C. Benoît and O. Rozenberg (eds), Handbook of Parliamentary Studies: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Legislatures, Edward Elgar Publishing, (2020) . doi:10.4337/9781789906516. |

[5] | L. Blaxill and K. Beelen, A feminized language of democracy? The representation of women at westminster since 1945, Twentieth Century British History 27: (3) ((2016) ), 412–449. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hww028. |

[6] | R. Bleier, F. Zeilinger and G. Vogeler, From early modern deliberation to the Semantic Web: Annotating communications in the records of the imperial diet of 1576, in: Proceedings of the Digital Parliamentary Data in Action (DiPaDA 2022) Workshop Co-Located with 6th Digital Humanities in the Nordic and Baltic Countries Conference (DHNB 2022), M. La Mela, F. Norén and E. Hyvönen, eds, CEUR WS, Vol. 3133: , (2022) , pp. 86–100, http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3133/paper06.pdf. |

[7] | U. Bojārs, R. Darģis, U. Lavrinovičs and P. Paikens, LinkedSaeima: A Linked Open Dataset of Latvia’s parliamentary debates, in: Semantic Systems. The Power of AI and Knowledge Graphs. SEMANTiCS 2019, Springer, (2019) , pp. 50–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33220-4_4. |

[8] | P. DiMaggio, M. Nag and D. Blei, Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of U.S. Government Arts funding, Poetics 41: (6) ((2013) ), 570–606. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.004. |

[9] | S. Drobac, L. Sinikallio and E. Hyvönen, An OCR pipeline for transforming parliamentary debates into Linked Data: Case ParliamentSampo – Parliament of Finland on the Semantic Web, in: Digital Humanities in the Nordic and Baltic Countries, 7th Conference, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, (2023) , In press, https://seco.cs.aalto.fi/publications/2022/drobac-et-al-ocr-2022.pdf. |

[10] | K. Elo and J. Karimäki, Luonnonsuojelusta ilmastopolitiikkaan: Ympäristöpoliittisen käsitteistön muutos parlamenttipuheessa 1960–2020, Politiikka 63: (4) ((2021) ), https://journal.fi/politiikka/article/view/109690. doi:10.37452/politiikka.109690. |

[11] | T. Erjavec, M. Ogrodniczuk, P. Osenova et al., The ParlaMint corpora of parliamentary proceedings, Lang Resources & Evaluation 57: ((2022) ), 415–448. doi:10.1007/s10579-021-09574-0. |

[12] | D. Fišer, M. Eskevich, J. Lenardič and F. de Jong (eds), Proceedings of the Workshop ParlaCLARIN III Within the 13th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, European Language Resources Association, Marseille, France, (2022) , https://aclanthology.org/2022.parlaclarin-1.0. |

[13] | J. Guldi, Parliament’s debates about infrastructure: An exercise in using dynamic topic models to synthesize historical change, Technology and Culture 60: (1) ((2019) ), 1–33. doi:10.1353/tech.2019.0000. |

[14] | A.A. Hagberg, D.A. Schult and P.J. Swart, Exploring network structure, dynamics, and function using NetworkX, in: Proceedings of the 7th Python in Science Conference, G. Varoquaux, T. Vaught and J. Millman, eds, Pasadena, CA, USA, (2008) , pp. 11–15. doi:10.25080/TCWV9851. |

[15] | M. Hidén and H. Honka-Hallila, Miten Eduskunta Toimii, Edita Publishing, Helsinki, (2006) . |

[16] | E. Hyvönen, Using the Semantic Web in digital humanities: Shift from data publishing to data-analysis and serendipitous knowledge discovery, Semantic Web – Interoperability, Usability, Applicability 11: (1) ((2020) ), 187–193. doi:10.3233/SW-190386. |

[17] | E. Hyvönen, Digital humanities on the Semantic Web: Sampo model and portal series, Semantic Web – Interoperability, Usability, Applicability 14: (4) ((2022) ), 729–744. doi:10.3233/SW-190386. |

[18] | E. Hyvönen, Parlamenttisampo avaa eduskunnan miljoona puhetta ja kansanedustajien verkostot kaikkien tutkittaviksi, Tieteessä tapahtuu 41: (1) ((2023) ), https://seco.cs.aalto.fi/publications/2023/hyvonen-parlamenttisampo-tt-2023.pdf. |

[19] | E. Hyvönen, How to Create a National Cross-Domain Ontology and Linked Data Infrastructure and Use It on the Semantic Web, Semantic Web – Interoperability, Usability, Applicability, (2024) , https://doi.org/10.3233/SW-243468. doi:10.3233/SW-243468. |

[20] | E. Hyvönen, P. Leskinen, M. Tamper, H. Rantala, E. Ikkala, J. Tuominen and K. Keravuori, BiographySampo – publishing and enriching biographies on the semantic web for digital humanities research, in: The Semantic Web. 16th International Conference, ESWC 2019, Proceedings, Springer, (2019) , pp. 574–589. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-21348-0. |

[21] | E. Hyvönen, L. Sinikallio, P. Leskinen, S. Drobac, R. Leal, M.L. Mela, J. Tuominen, H. Poikkimäki and H. Rantala, Plenary speeches of the Parliament of Finland as Linked Open Data and data services, in: Joint Proceedings of the Second International Workshop on Knowledge Graph Generation from Text and the First International BiKE Challenge Co-Located with 20th Extended Semantic Conference (ESWC 2023), CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Vol. 3447: , (2023) , pp. 1–20, https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3447/. |

[22] | E. Hyvönen, L. Sinikallio, P. Leskinen, S. Drobac, J. Tuominen, K. Elo, M. La Mela, M. Koho, E. Ikkala, M. Tamper, R. Leal and J. Kesäniemi, Parlamenttisampo: Eduskunnan aineistojen linkitetyn avoimen datan palvelu ja sen käyttömahdollisuudet, Informaatiotutkimus 40: (2) ((2021) ). doi:10.23978/inf.107899. |

[23] | E. Hyvönen, L. Sinikallio, P. Leskinen, M. La Mela, J. Tuominen, K. Elo, S. Drobac, M. Koho, E. Ikkala, M. Tamper, R. Leal and J. Kesäniemi, Finnish Parliament on the Semantic Web: Using ParliamentSampo data service and semantic portal for studying political culture and language, in: Digital Parliamentary Data in Action (DiPaDA 2022), Workshop at the 6th Digital Humanities in Nordic and Baltic Countries Conference, Long Paper, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Vol. 3133: , (2022) , pp. 69–85, http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3133/paper05.pdf. |

[24] | E. Hyvönen, M. Tamper, E. Ikkala, M. Koho, R. Leal, J. Kesäniemi, A. Oksanen, J. Tuominen and A. Hietanen, LawSampo portal and data service for publishing and using legislation and case law as Linked Open Data on the Semantic Web, in: AI4LEGAL-KGSUM 2022: Artificial Intelligence Technologies for Legal Documents and Knowledge Graph Summarization 2022, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Vol. 3257: , (2022) , pp. 41–50, http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3257/paper5.pdf. |

[25] | E. Hyvönen, J. Tuominen, M. Alonen and E. Mäkelä, Linked Data Finland: A 7-star model and platform for publishing and re-using linked datasets, in: The Semantic Web: ESWC 2014 Satellite Events, Revised Selected Papers, Springer, (2014) , pp. 226–230. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-11955-7_24. |

[26] | P. Ihalainen and A. Sahala, Evolving conceptualisations of internationalism in the UK Parliament: Collocation analyses from the league to Brexit, in: Digital Histories: Emergent Approaches Within the New Digital History, M. Fridlund, M. Oiva and P. Paju, eds, Helsinki University Press, (2020) , pp. 199–219. doi:10.33134/HUP-5-12. |

[27] | E. Ikkala, E. Hyvönen, H. Rantala and M. Koho, Sampo-UI: A full stack JavaScript framework for developing semantic portal user interfaces, Semantic Web – Interoperability, Usability, Applicability 13: (1) ((2022) ), 69–84. doi:10.3233/SW-210428. |

[28] | C. Jacobi, W. van Atteveldt and K. Welbers, Quantitative analysis of large amounts of journalistic texts using topic modelling, Poetics 4: (1) ((2016) ), 89–106. doi:10.1080/21670811.2015.1093271. |

[29] | J. Jarlbrink and F. Norén, The rise and fall of ‘propaganda’ as a positive concept: A digital reading of Swedish parliamentary records, 1867–2019, Scandinavian Journal of History ((2022) ), e1–e21. doi:10.1080/03468755.2022.2134202. |

[30] | Z. Jelveh, B. Kogut and S. Naidu, Detecting latent ideology in expert text: Evidence from academic papers in economics, in: Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), ACL, (2018) , pp. 1804–1809. |

[31] | K. Kettunen and M. La Mela, Semantic tagging and the Nordic tradition of everyman’s rights, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 37: (2) ((2021) ). doi:10.1093/llc/fqab052. |

[32] | Kirjo – Kirjaamisohjeet, Guidelines for recording minutes of plenary sessions at Parliament of Finland, (2021) . |

[33] | J.M. Kleinberg, Authoritative sources in a hyperlinked environment, Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery 46: ((1999) ), 604–632. doi:10.1145/324133.324140. |

[34] | M. Koho, L. Gasbarra, J. Tuominen, H. Rantala, I. Jokipii and E. Hyvönen, AMMO ontology of Finnish historical occupations, in: Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Open Data and Ontologies for Cultural Heritage (ODOCH’19), Vol. 2375, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, (2019) , pp. 91–96, http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2375/. |

[35] | T. Koltay, Data literacy for researchers and data librarians, Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 49: (1) ((2015) ), 3–14. doi:10.1177/0961000615616450. |

[36] | M. La Mela, Tracing the emergence of Nordic allemansrätten through digitised parliamentary sources, in: Digital Histories: Emergent Approaches Within the New Digital History, M. Fridlund, M. Oiva and P. Paju, eds, Helsinki University Press, (2020) , pp. 181–197. doi:10.33134/HUP-5-11. |

[37] | M. La Mela, F. Norén and E. Hyvönen, (eds), Digital Parliamentary Data in Action (DiPaDA 2022): Introduction, in: Proceedings of the Digital Parliamentary Data in Action (DiPaDA 2022) Workshop Co-Located with 6th Digital Humanities in the Nordic and Baltic Countries Conference (DHNB 2022), Vol. 3133: , CEUR WS, (2022) , pp. 1–8, http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3133/paper00.pdf. |

[38] | S.-M. Laaksonen and M. Nelimarkka, Omat ja muiden aiheet: Laskennallinen analyysi vaalijulkisuuden teemoista ja aiheomistajuudesta, Politiikka 60: (2) ((2018) ), 132–147. |

[39] | E. Lapponi, M.G. Søyland, E. Velldal and S. Oepen, The talk of Norway: A richly annotated corpus of the Norwegian Parliament, 1998–2016, Language Resources and Evaluation 52: (3) ((2018) ), 873–893. doi:10.1007/s10579-018-9411-5. |

[40] | R. Leal, J. Kesäniemi, M. Koho and E. Hyvönen, Relevance feedback search based on automatic annotation and classification of texts, in: 3rd Conference on Language, Data and Knowledge (LDK 2021), Open Access Series in Informatics (OASIcs), Vol. 93: , Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, Dagstuhl, Germany, (2021) , pp. 18:1–18:15, ISSN 2190-6807. ISBN 978-3-95977-199-3. doi:10.4230/OASIcs.LDK.2021.18. |

[41] | M. Lennes, FIN-CLARIN and Language Bank Parliamentary Data. Workshop “Digital Parliamentary Data and Research”, Aalto University, Finland, (2019) , https://www2.helsinki.fi/en/helsinki-centre-for-digital-humanities/workshop-digital-parliamentary-data-and-research. |

[42] | P. Leskinen, E. Hyvönen and J. Tuominen, Members of Parliament in Finland knowledge graph and its Linked Open Data service, in: Further with Knowledge Graphs, Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Semantic Systems, 6-9 September 2021, IOS Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, (2021) , pp. 255–269. doi:10.3233/SSW210049. |

[43] | E. Lillqvist, I.K. Kavonius and M. Pantzar, “Velkakello tikittää”: Julkisyhteisöjen velka suomalaisessa mielikuvastossa ja tilastoissa 2000–2020, Kansantaloudellinen Aikakauskirja 116: (4) ((2020) ), 581–607, https://journal.fi/politiikka/article/view/77163. |

[44] | M. Magnusson, R. Öhrvall, K. Barrling and D. Mimno, Voices from the far right: A text analysis of Swedish parliamentary debates, SocArXiv ((2018) ). doi:10.31235/osf.io/jdsqc. |

[45] | E. Mäkelä, LAS: An integrated language analysis tool for multiple languages, J. Open Source Software 1: (6) ((2016) ), 35. doi:10.21105/joss.00035. |

[46] | E. Mäkelä, K. Lagus, L. Lahti, T. Säily, M. Tolonen, M. Hämäläinen, S. Kaislaniemi and T. Nevalainen, Wrangling with non-standard data, in: Proceedings of the Digital Humanities in the Nordic Countries 5th Conference, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, (2020) , pp. 81–96, http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2612/paper6.pdf. |

[47] | K. Makkonen and P. Loukasmäki, Eduskunnan täysistunnon puheenaiheet 1999—2014: Miten käsitellä LDA-aihemalleja?, Politiikka 61: (2) ((2019) ), 127–159, https://journal.fi/politiikka/article/view/77163. |

[48] | A. Mansikkaniemi, P. Smit and M. Kurimo, Automatic construction of the Finnish Parliament speech corpus, in: Proc. Interspeech 2017, (2017) , pp. 3762–3766. doi:10.21437/Interspeech.2017-1115. |

[49] | A. Martínez Arranz, S.T. Zech and M. Bonotti, Political parties and civility in Parliament: The case of Australia from 1901 to 2020, Parliamentary Affairs 77: (2) ((2023) ), 371–399. doi:10.1093/pa/gsad008. |

[50] | T. Mikolov, E. Grave, P. Bojanowski, C. Puhrsch and A. Joulin, Advances in pre-training distributed word representations, in: Proceedings of the International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), (2018) . |

[51] | D. Mimno, Topic Regression, PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst, (2012) . |

[52] | F. Moretti, Distant Reading, Verso Books, (2013) . |

[53] | J.B. Mountford, Topic modeling the red pill, Social Sciences 7: (3) ((2018) ). doi:10.3390/socsci7030042. |

[54] | M. Ogrodniczuk, P. Osenova, T. Erjavec, D. Fišer, N. Ljubešic, Ç. Çöltekin, M. Kopp and K. Meden, ParlaMint II: The show must go on, in: Proceedings of the Workshop ParlaCLARIN III Within the 13th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, D. Fišer, M. Eskevich, J. Lenardič and F. de Jong, eds, European Language Resources Association, Marseille, France, (2022) , pp. 1–6, https://aclanthology.org/2022.parlaclarin-1.1.pdf. |

[55] | A. Pancur and T. Erjavec, The siParl corpus of Slovene parliamentary proceedings, in: Proceedings of the Second ParlaCLARIN Workshop, European Language Resources Association, (2020) , pp. 28–34, https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/2020.509parlaclarin-1.6. |

[56] | H. Poikkimäki, Eduskunnan täysistuntojen puheenvuorojen henkilömainintoihin perustuvien verkostoiden analyysi, Master’s thesis, Aalto University, Department of Computer Science, (2023) . |

[57] | H. Poikkimäki, P. Leskinen and E. Hyvönen, Applying Network and Bibliometric Analyses to Mentions of Politicians in Plenary Speeches: Case ParliamentSampo – Parliament of Finland on the Semantic Web, (2024) , Submitted for evaluation, https://seco.cs.aalto.fi/publications/2023/poikkimaki-et al-ps-networks-2023.pdf. |

[58] | H. Poikkimäki, P. Leskinen, M. Tamper and E. Hyvönen, Analyses of networks of politicians based on Linked Data: Case ParliamentSampo – Parliament of Finland on the Semantic Web, in: Semantic Web and Ontology Design for Cultural Heritage (SWODCH 2022), Turin, Italy, Proceedings, CEUR WS Proceedings, (2022) , Accepted, https://seco.cs.aalto.fi/publications/2022/poikkimaki-et-al-2022.pdf. |

[59] | S. Purhonen and A. Toikka, “Big Datan” haaste ja uudet laskennaliset tekstiaineistojen analyysimenetelmät: Esimerkkitapauksena aihemallianalyysi tasavallan presidenttien uudenvuodenpuheista 1935–2015, Sosiologia 53: (1) ((2016) ), 6–27, http://elektra.helsinki.fi/se/s/0038-1640/53/1/bigdatan.pdf. |

[60] | K.M. Quinn, B.L. Monroe, M. Colaresi, M.H. Crespin and D.R. Radev, How to analyze political attention with minimal assumptions and costs, American Journal of Political Science 54: ((2010) ), 209–228. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00427.x. |

[61] | H. Rantala, A. Ahola, E. Ikkala and E. Hyvönen, How to create easily a data analytic semantic portal on top of a SPARQL endpoint: Introducing the configurable Sampo-UI framework, in: VOILA! 2023 Visualization and Interaction for Ontologies, Linked Data and Knowledge Graphs 2023, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Vol. 3508: , (2023) , https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3508/paper3.pdf. |

[62] | C. Rauh, P. De Wilde and J. Schwalbach, The ParlSpeech data set: Annotated full-text vectors of 3.9 million plenary speeches in the key legislative chambers of seven European states (V1), Harvard Dataverse, (2017) . doi:10.7910/DVN/E4RSP9. |

[63] | L. Rietveld and R. Hoekstra, The YASGUI family of SPARQL clients, Semantic Web – Interoperability, Usability, Applicability 8: (3) ((2017) ), 373–383. doi:10.3233/SW-150197. |

[64] | K. Seppälä and E. Hyvönen, Asiasanaston muuttaminen ontologiaksi. Yleinen suomalainen ontologia esimerkkinä FinnONTO-hankkeen mallista, (2014) , https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/96825. |

[65] | S. Simola, A Century of Partisanship in Finnish Political Speech, (2020) , https://sites.google.com/site/sallasimolaecon/home/research. |

[66] | L. Sinikallio, Eduskunnan täysistuntojen pöytäkirjojen muuntaminen semanttiseksi dataksi ja julkaiseminen verkkopalveluna, Master’s thesis, University of Helsinki, Department of Computer Science, (2022) . |

[67] | L. Sinikallio, S. Drobac, M. Tamper, R. Leal, M. Koho, J. Tuominen, M.L. Mela and E. Hyvönen, Plenary debates of the Parliament of Finland as Linked Open Data and in Parla-CLARIN markup, in: 3rd Conference on Language, Data and Knowledge, LDK 2021, Schloss Dagstuhl- Leibniz-Zentrum fur Informatik GmbH, Dagstuhl Publishing, (2021) , pp. 1–17, https://drops.dagstuhl.de/opus/volltexte/2021/14544/pdf/OASIcs-LDK-2021-8.pdf. |

[68] | O. Suominen, Annif: DIY automated subject indexing using multiple algorithms, LIBER Quarterly 29: (1) ((2019) ), 1–25. doi:10.18352/lq.10285. |

[69] | M. Tamper, R. Leal, L. Sinikallio, P. Leskinen, J. Tuominen and E. Hyvönen, Extracting knowledge from parliamentary debates for studying political culture and language, in: Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Knowledge Graph Generation from Text and the 1st International Workshop on Modular Knowledge Co-Located with 19th Extended Semantic Conference (ESWC 2022), Vol. 3184: , S. Tiwari, N. Mihindukulasooriya, F. Osborne, D. Kontokostas, J. D’Souza and M. Kejriwal, eds, CEUR WS, (2022) , pp. 70–79, International Workshop on Knowledge Graph Generation from Text (TEXT2KG 2022), http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3184/TEXT2KG_Paper_5.pdf. |

[70] | M. Tamper, P. Leskinen, E. Hyvönen, R. Valjus and K. Keravuori, Analyzing Biography Collection Historiographically as Linked Data: Case National Biography of Finland, Semantic Web – Interoperability, Usability, Applicability, (2021) , accepted, https://seco.cs.aalto.fi/publications/2021/tamper-et-al-bs-2021.pdf. |

[71] | T.R. Tangherlini and P. Leonard, Trawling in the sea of the great unread: Sub-corpus topic modeling and humanities research, Poetics 41: (6) ((2013) ), 725–749. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.002. |

[72] | K. Thornton, H. Solbrig, G.S. Stupp, J.E.L. Gayo, D. Mietchen, E. Prud’hommeaux and A. Waagmeester, Using shape expressions (ShEx) to share RDF data models and to guide curation with rigorous validation, in: The Semantic Web. ESWC 2019, Springer, (2019) , pp. 606–620. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-21348-0_39. |

[73] | A. Törnberg and P. Törnberg, Muslims in social media discourse: Combining topic modeling and critical discourse analysis, discourse, Context and Media 13: ((2016) ), 132–142. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2016.04.003. |

[74] | J. Tuominen, E. Hyvönen and P. Leskinen, io CRM: A data model for representing biographical data for prosopographical research, in: Proceedings of the Second Conference on Biographical Data in a Digital World 2017 (BD2017), Vol. 2119: , CEUR Workshop Proceedings, (2018) , pp. 59–66, http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2119/paper10.pdf. |

[75] | Y. Tzitzikas, N. Manolis and P. Papadakos, Faceted exploration of RDF/S datasets: A survey, Journal of Intelligent Information Systems 48: (2) ((2017) ), 329–364. doi:10.1007/s10844-016-0413-8. |

[76] | A. Van Aggelen, L. Hollink, M. Kemman, M. Kleppe and H. Beunders, The debates of the European Parliament as Linked Open Data, Semantic Web – Interoperability, Usability, Applicability 8: (2) ((2017) ), 271–281. doi:10.1007/s42001-019-00060-w. |

![PoF ontology data model [42] based on Bio CRM.](https://content.iospress.com:443/media/sw-prepress/sw--1--1-sw243683/sw--1-sw243683-g002.jpg)