The impact of new judging criteria on 10-8 scores in MMA

Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of changes in judging criteria on 10-8 scores in Zuffa-owned mixed martial arts (MMA) promotions. Utilizing a differences-in-differences framework, the 2017 liberalization of 10-8 scoring criteria in the Unified Rules of MMA is examined across various judge groups. Findings suggest that traveling judges and Nevada judges – those most likely to be at the forefront of the regulatory evolution of the sport – had already liberalized their 10-8 scoring one year prior to the effective date of the new criteria. Other judges appear to have effectively implemented the new criteria since January 2017 with 10-8 probabilities on par with traveling and Nevada judges. The effect of an earlier change in judging criteria is also examined in Nevada. Results suggest the numerous and distributed regulatory agencies involved in the sport of MMA were effective in the implementation of new policies for scoring rounds.

1Introduction

“[Traveling judges have] figured out the criteria they’re judging off, and no matter where they are or where they go, they’re using that criteria.”

– John McCarthy, Bellator commentator,

COMMAND head instructor

The “10-Point Must” system in mixed martial arts (MMA) is a legacy scoring system from boxing whereby judges award 10 points to the winner of each round and nine points or fewer to the round loser. First appearing in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) at UFC 21 in July 1999, the 10-Point Must System would later be codified into the judging criteria of the original Unified Rules of MMA in 2001.

While both sports now utilize the 10-Point Must System for scoring, a key distinction between boxing and MMA matches is the number of scheduled rounds. A boxing match can be scheduled in even increments of 4–12 rounds, with the number of rounds increasing as boxers approach championship caliber. Title fights are generally 12 rounds while non-title fights are typically 10 rounds or fewer. MMA bouts, on the other hand, are typically three-round affairs, while title fights are scheduled for five rounds.1

In a three-round fight, a judge’s decision to score a round 10-8 instead of 10-9 – doubling the reward for winning the round – can easily be the difference between a fighter earning a 28-28 draw instead of losing 28-29 when the opponent wins the other two rounds.2 And the decision to score a 10-8 has historically been more difficult in MMA than boxing. While 10-8s in boxing do not require a knockdown, California’s judging criteria in 2017 stated, “The knockdown should count as one point,” and the Pod Index has found that all three boxing judges unanimously agree on 10-8 rounds 93% of the time (Gift, 2018a). In MMA, there is no such knockdown rule and judges unanimously agreed on a 10-8 round only 8.7% of the time from 2001–2012, increasing to 26.1% by 2017 (Gift, 2018a). Hence, this paper will examine the impact of two changes to the 10-8 scoring criteria in MMA intended to liberalize their usage for “the evolution of the sport and the fairness to the fighters” (Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports, 2016, pp. 3).

While much of the extant MMA literature has been devoted to analyses of UFC pay-per-view buyrates (Watanabe, 2012; Tainsky, Salaga, & Santos, 2013; Watanabe, 2015; and Reams & Shapiro, 2017), researchers have also studied the marginal revenue product of UFC fighters (Gift, 2020) and examined the impact of fight night bonuses (Gift, 2019b) and cage size (Gift, 2019a) on various aspects of fighter performance.

The two papers most closely related to the present study are Collier, Johnson, and Ruggiero (2012) and Gift (2018c). Both studies analyzed the performance determinants of MMA judging decisions with Collier et al. using aggregate bout statistics and the final bout outcome and Gift examining the round-by-round scoring decisions of judges in “close margin” 10-9 rounds. Collier et. al also tested for the impact of non-performance measures (age and height) and found no statistical effect. Gift’s analysis found that MMA judges tend to show bias towards larger betting favorites, fighters with an insurmountable lead, and the fighter who won the previous round. In contrast to Collier et al. and Gift, the judging decision of interest in the present study is not who wins or loses a bout or round, but rather the decision to award a 10-8 score instead of 10-9 when the round-winning fighter is not in dispute.

In MMA, judges do not work for individual promoters such as the UFC or Bellator. Instead they work for state and local athletic commissions and their workload throughout a year and requirements for training can vary from commission to commission. Contrary to more traditional sports, MMA is a sport of regulatory fiefdoms. Each athletic commission defines the ruleset for regulated MMA bouts within its jurisdiction. When no regulatory agency exists, promoters will self-regulate or contract with a regulatory body such as the Mohegan Department of Athletic Regulation, which Bellator utilizes when it travels internationally to an unregulated jurisdiction. At the national level in the United States, the Unified Rules of MMA are maintained by the Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports (ABC), a non-profit organization composed of member athletic commissions. Amendments to these rules are approved by member commissions at an annual meeting, but the fact remains: The ABC maintains no regulatory authority over local commissions and can only recommend policy. Thus, as distributed regulators, each state or local commission ultimately selects the rules for MMA within its boundaries.

Fortunately, changes to the judging criteria within the Unified Rules have not been controversial, unlike other changes such as the definition of a grounded fighter. Thus, the question of interest is: How well has the network of distributed regulators across the sport of MMA implemented agreed upon changes to the scoring criteria 10-8 rounds? Utilizing a non-experimental difference-in-differences framework across time and local jurisdictions, I find that traveling and Nevada judges – those most likely to be at the forefront of the regulatory evolution of the sport – had already liberalized their 10-8 scoring prior to the most recent change in January 2017. However, other judges quickly caught up in 2017 and maintained 10-8 probabilities on par with traveling and Nevada judges. Additionally, over a longer time horizon, multiple efforts to liberalize 10-8 scoring appear to have been effective in Nevada. These findings can have value not only to the athletic commissions who oversee the judges, but also to the fighters, coaches, promoters, and even fans seeking more “fairness to the fighters.”

2MMA judging criteria

The UFC, presently the world’s largest MMA promoter, held its first event on November 12, 1993. Initially described as “no holds barred” fighting, there were only two rules – no biting and no eye gouging – and fights could only end by a tapout or corner stoppage. The first appearance of judges and decision finishes occurred at UFC 7.5 in December 1995. Using the scoring categories of aggressiveness, best strikes, and grappling techniques, a panel of three judges evaluated the fight as a whole, revealing winners on paddles which would then be shown to the film crew and the audience.

Shortly after Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta bought the UFC in January 2001, the Unified Rules of MMA were authorized by the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board, including judging criteria for scoring rounds.3 The particular criterion of interest in this paper is that used to double the reward for winning a round: a score of 10-8 instead of the most frequent score of 10-9. According to the initial Unified Rules of MMA, “A round is to be scored as a 10-8 Round when a contestant overwhelmingly dominates by striking or grappling in a round.” (Emphasis added; New Jersey State Athletic Control Board, 2001, pp. 8).

MMA’s judging criteria would remain unchanged for roughly 12 years until 2012 (but effective January 2013), when the ABC approved certain changes in order “to bring a greater clarity with respect to the overall criteria of MMA judging” (Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports, 2012, pp. 2). The definition of a 10-8 round was relaxed from a fighter overwhelmingly dominating to instead winning by a “large margin.” In particular, “A round is to be scored as a 10-8 Round when a contestant wins by a large margin, by effective striking and or effective grappling that have great impact on the opponent” (Emphasis added; Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports, 2012, pp. 5). Soon thereafter, the unwritten “Two D’s” of Dominance and Damage for determining 10-8 rounds originated and began circulating.

In August 2016, in order “to evolve mixed martial arts ... ,” the ABC once again passed changes to the judging criteria (Raimondi, 2017, pp. 1). Effective January 1, 2017, a 10-8 round was still defined as a fighter winning by a large margin, however the new criteria liberalized what constituted a “large” margin by incorporating the Three D’s of Dominance, Damage (also known as “Impact”), and Duration, and explicitly noting when a judge “shall always” score a 10-8 versus when a judge “must consider” at 10-8 score. It was also the first time the concepts of Damage, Dominance, and Duration were explicitly put in writing. Damage is when a fighter impacts their opponent significantly in a round. Evidence of damage could include physical harm such swelling or lacerations as well as striking or grappling maneuvers that lead to a diminishing of the opponent’s “energy, confidence, abilities and spirit.” Dominance in striking is when a fighter forces their opponent to continually defend. In grappling, it is when a fighter takes dominant positions and uses those positions to “attempt fight ending submissions or attacks.” Duration is essentially the amount of time a fighter spent inflicting heavy damage or dominating the action. See Appendix A for a complete description of the expansive new 2017 judging criteria.

An empirical question of interest for fighters, coaches, fans, media, regulators, and promoters is: How effectively has MMA’s new judging criteria been implemented across local jurisdictions? Unlike other major sports, MMA does not have a central authority to advise and train all officials on rules/criteria changes. Training sessions from judges at the forefront of the sport are available in various locations throughout a typical year, but requirements for updated training vary by jurisdiction. Also varying greatly by jurisdiction are the number of sanctioned MMA events available each year for judges to work and gain experience. For example, 69 professional MMA events were held in California in 2018 and 34 in Nevada. Meanwhile, Alabama, North Dakota, Vermont, and West Virginia were home to only two events each, according to the site operator of the MMA database Tapology.com (Kelliher, 2019).

3Data

3.1Fightmetric

The dataset for the present study was obtained from FightMetric, the official statistics provider for the UFC. For each round and fighter, FightMetric tracks over 100 performance statistics covering striking, damage, knockdowns, takedowns, grappling, and submissions, as well as time spent with and without control in various positions such as the clinch, guard, half guard, side control, mount, and having an opponent’s back. In addition to the UFC, FightMetric tracked performance statistics for World Extreme Cagefighting (WEC) and Strikeforce events. Zuffa LLC, the corporate entity which owns and operates the UFC, acquired the rival WEC and Strikeforce promotions in December 2006 and March 2011, respectively.4 Bouts in these promotions while under Zuffa ownership will be utilized in the second sample period of the present study as described below.

In addition to fighter performance statistics, FightMetric acquired judge scorecards for many past UFC, WEC, and Strikeforce events held in two of the most active jurisdictions, Nevada and California, as far back as 2001 and 2006, respectively.5 In January 2016, FightMetric initiated the collection and tracking of scorecards for every UFC event, conditional on the regulating athletic commission publicly releasing such information. Thus, the potential dataset for the present study can be seen in Table 1 and is tabulated by judge-round scored. All scored rounds are included regardless of whether the fight ultimately went to a decision or ended by knockout or submission in a subsequent round.

Table 1

Judge-rounds scored by jurisdiction

| Year | Nevada | California | New York | Other Domestic | International | Total |

| 2001 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75 |

| 2002 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 54 |

| 2003 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 |

| 2004 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90 |

| 2005 | 192 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 192 |

| 2006 | 321 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 378 |

| 2007 | 369 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 414 |

| 2008 | 354 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 408 |

| 2009 | 411 | 108 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 519 |

| 2010 | 399 | 243 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 642 |

| 2011 | 468 | 120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 588 |

| 2012 | 303 | 147 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 450 |

| 2013 | 357 | 144 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 501 |

| 2014 | 339 | 108 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 447 |

| 2015 | 126 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 147 |

| 2016 | 432 | 108 | 129 | 372 | 630 | 1,671 |

| 2017 | 333 | 123 | 147 | 474 | 663 | 1,740 |

| 2018 | 255 | 105 | 159 | 672 | 708 | 1,899 |

| 2019 | 60 | 0 | 45 | 324 | 237 | 666 |

| Total | 4,983 | 1,383 | 480 | 1,842 | 2,238 | 10,926 |

Note: For all Zuffa-owned UFC, WEC, and Strikeforce events with scorecards tracked by FightMetric and unanimous judge agreement on the round winner in the 2001–2019 sample period.

The 10-8 scoring decision is a determination as to whether a fighter won by a close margin (10-9) or overwhelmingly dominated or won by a large margin (10-8, depending on the time period of the bout). Hence, if a 10-8 is being considered by a judge, the round winner should be apparent. The data supports this notion as there was only a single disagreement on the round winner in 409 rounds with at least one 10-8 score.6 Since the relevant decision being examined is the extent to which the winning fighter dominated the action, the sample for the present study, as seen in Table 1, is composed of all rounds in which judges unanimously agreed upon the winner. In other words, given judge agreement on which fighter won the round, the decision of interest is whether a 10-8 score is warranted over a 10-9.7

Two sample periods will be employed in this study:

1. 2016–2019 Sample Period: All UFC events with available scorecards held across 47 local jurisdictions from January 30, 2016 (the first observed date of FightMetric’s widespread scorecard collection) through April 20, 2019.

2. 2001–2019 Sample Period: All UFC, WEC, and Strikeforce events with available scorecards held in Nevada from September 28, 2001 (the first Zuffa-operated UFC event in the state) through April 20, 2019.

The 2016–2019 sample period can be seen towards the bottom of Table 1. Nevada, California, and New York were the three most active jurisdictions in terms of unanimous judge-rounds scored, with other domestic and international locations each contributing a sizeable number of scores. The 2001–2019 sample period can be seen in the Nevada column on the left.

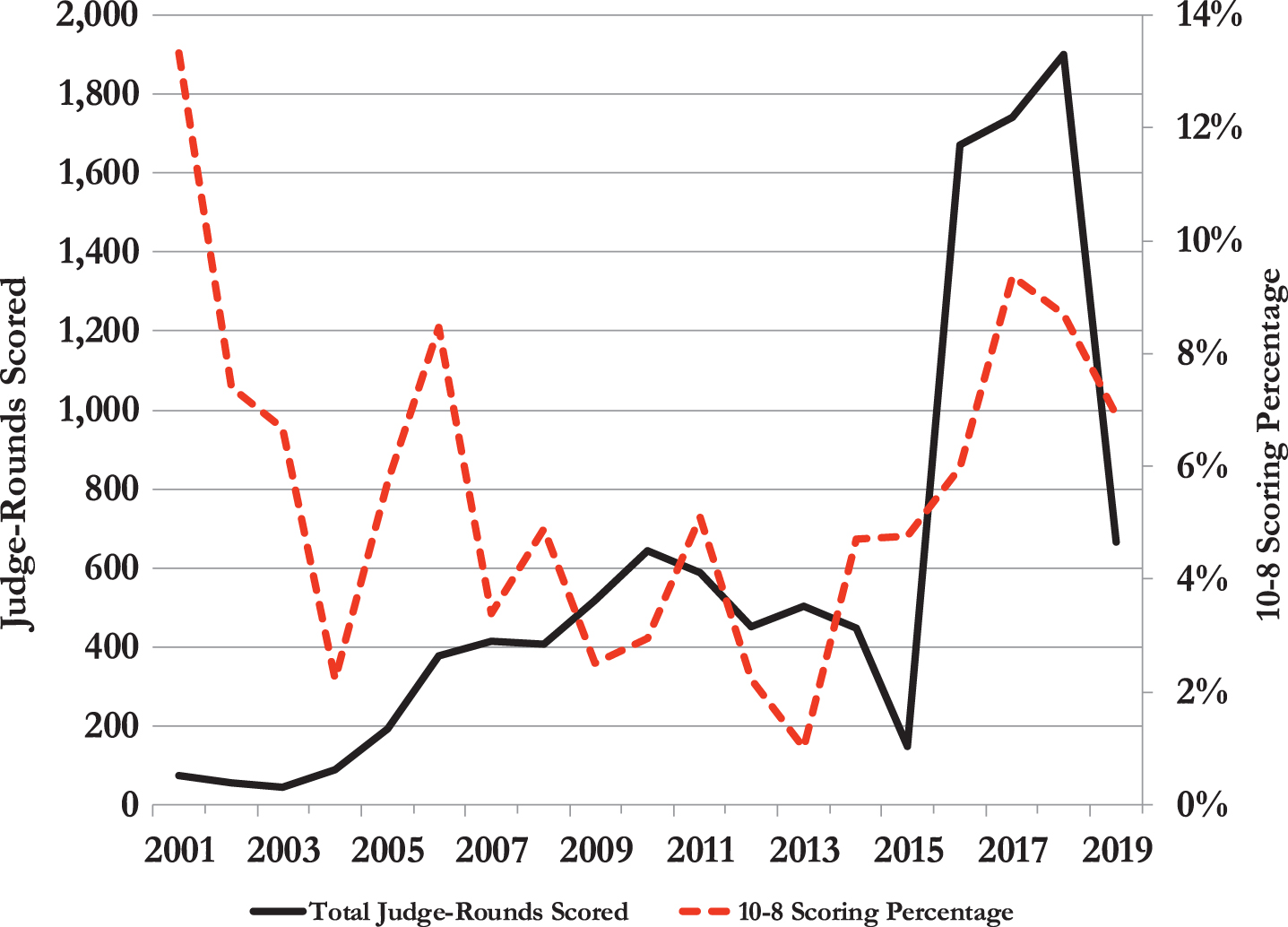

3.2Descriptive statistics

Raw data over the entire 2001–2019 period is presented in Fig. 1. Available scorecards for unanimous rounds increased substantially in 2016 when FightMetric initiated a rigorous collection process. When examining the percentage of unanimous judge-rounds assigned a 10-8 score, the right-most tail appears to increase in recent years as one would expect from a liberalization of the 10-8 criteria. However, early years contain higher 10-8 scoring percentages than might be expected when earning a 10-8 required overwhelming domination. One possibility is the fights themselves may have been more lopsided in the early years of modern MMA, typically taken to be from 2001 when the Fertitta brothers purchased the UFC. 10-8 scores may have required more domination in these early years, yet the matchups may have been more lopsided. As the sport developed, better athletes entered, and coaching and training methods improved, a reduced amount of domination may help explain the apparent downward trend in 10-8 scoring percentages through roughly 2013. The data appears supportive in this regard as unanimous round winners during 2001–2006 had higher pre-fight standard normalized win probabilities (59.2%) and tended to out-land their opponents each round with more knockdowns (+0.11), damage (+0.19), and power strikes to the head (+6.37) than in any other period covering 2007–2012, 2013–2016, and 2017–2019. However, regardless of the precise cause, the changes in raw 10-8 scoring percentages over time help highlight the importance of controlling for in-cage fighter performances when evaluating 10-8 scores, as will be addressed in Section 4 below.

Fig. 1

Judge-rounds scored and 10-8 scoring percentages by year. Note: For all Zuffa-owned UFC, WEC, and Strikeforce events with scorecards tracked by FightMetric and unanimous judge agreement on the round winner.

Tables 2 and 3 present descriptive statistics on the binary outcome variable, 10-8 Score, and the 29 control variables of fighter performance utilized in the two samples of the present study. All control variables are the difference in performance statistics between the winning and losing fighter. Both tables show that fighters who unanimously win their rounds tend to both land and miss more strikes than losing fighters, or put another way, they tend to be more active. This may partially be due to the winning fighter more often being in a position of control, as can be seen towards the bottom of each table. Fighters who win rounds unanimously also tend to get more knockdowns, do more visible damage, and land more takedowns (slams and non-slams) than unanimous round losers.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics in the 2016–2019 sample period

| Variable | N | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

| 10-8 Score | 5,976 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 |

| Head Jabs Landed | 5,976 | 4.38 | 10.0 | –46 | 62 |

| Head Jabs Missed | 5,976 | 1.11 | 8.15 | –37 | 35 |

| Head Power Landed | 5,976 | 5.80 | 7.82 | –19 | 78 |

| Head Power Missed | 5,976 | 1.98 | 8.91 | –34 | 42 |

| Body Jabs Landed | 5,976 | 1.68 | 5.42 | –24 | 57 |

| Body Jabs Missed | 5,976 | 0.08 | 1.18 | –6 | 9 |

| Body Power Landed | 5,976 | 1.45 | 3.86 | –14 | 32 |

| Body Power Missed | 5,976 | 0.14 | 2.05 | –11 | 11 |

| Leg Jabs Landed | 5,976 | 0.64 | 3.86 | –27 | 40 |

| Leg Jabs Missed | 5,976 | 0.01 | 1.07 | –9 | 7 |

| Leg Power Landed | 5,976 | 0.79 | 3.44 | –21 | 16 |

| Leg Power Missed | 5,976 | 0.06 | 1.30 | –9 | 9 |

| Knockdowns | 5,976 | 0.08 | 0.34 | –1 | 4 |

| Damage | 5,976 | 0.08 | 0.32 | –1 | 1 |

| Takedown Slams | 5,976 | 0.08 | 0.42 | –3 | 4 |

| Takedowns Landed (No Slam) | 5,976 | 0.43 | 1.06 | –5 | 6 |

| Takedowns Missed | 5,976 | –0.08 | 1.82 | –10 | 8 |

| Submission Chokes Attempted | 5,976 | 0.06 | 0.42 | –2 | 3 |

| Submission Locks Attempted | 5,976 | 0.00 | 0.31 | –5 | 3 |

| Tight Submission | 5,976 | 0.01 | 0.13 | –1 | 1 |

| Standups | 5,976 | –0.35 | 0.98 | –6 | 4 |

| Sweeps | 5,976 | 0.02 | 0.31 | –2 | 2 |

| Clinch Control Time | 5,976 | 0.15 | 0.72 | –4 | 5 |

| Guard Control Time | 5,976 | 0.22 | 0.68 | –4 | 4 |

| Half Guard Control Time | 5,976 | 0.17 | 0.51 | –3 | 3 |

| Side Control Time | 5,976 | 0.08 | 0.33 | –2 | 4 |

| Mount Control Time | 5,976 | 0.04 | 0.21 | –2 | 3 |

| Back Control Time | 5,976 | 0.09 | 0.45 | –2 | 4 |

| Miscellaneous Control Time | 5,976 | 0.33 | 0.72 | –3 | 4 |

Note: Data is at the judge-round level. For all UFC events with scorecards tracked by FightMetric and unanimous judge agreement on the round winner.

Table 3

Descriptive statistics in the 2001–2019 sample period

| Variable | N | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

| 10-8 Score | 4,983 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 |

| Head Jabs Landed | 4,983 | 6.58 | 12.7 | –67 | 86 |

| Head Jabs Missed | 4,983 | 1.41 | 7.46 | –48 | 42 |

| Head Power Landed | 4,983 | 5.49 | 6.73 | –13 | 69 |

| Head Power Missed | 4,983 | 2.68 | 8.06 | –30 | 38 |

| Body Jabs Landed | 4,983 | 2.89 | 7.27 | –41 | 53 |

| Body Jabs Missed | 4,983 | 0.01 | 0.99 | –6 | 9 |

| Body Power Landed | 4,983 | 1.54 | 3.50 | –11 | 32 |

| Body Power Missed | 4,983 | 0.05 | 1.66 | –9 | 11 |

| Leg Jabs Landed | 4,983 | 0.39 | 3.61 | –27 | 40 |

| Leg Jabs Missed | 4,983 | –0.03 | 0.98 | –7 | 8 |

| Leg Power Landed | 4,983 | 0.69 | 3.20 | –21 | 25 |

| Leg Power Missed | 4,983 | 0.01 | 0.98 | –6 | 5 |

| Knockdowns | 4,983 | 0.08 | 0.32 | –1 | 3 |

| Damage | 4,983 | 0.10 | 0.34 | –1 | 1 |

| Takedown Slams | 4,983 | 0.09 | 0.40 | –2 | 4 |

| Takedowns Landed (No Slam) | 4,983 | 0.58 | 1.21 | –4 | 6 |

| Takedowns Missed | 4,983 | –0.16 | 2.00 | –10 | 7 |

| Submission Chokes Attempted | 4,983 | 0.08 | 0.57 | –3 | 3 |

| Submission Locks Attempted | 4,983 | 0.01 | 0.42 | –3 | 4 |

| Tight Submission | 4,983 | 0.01 | 0.22 | –1 | 1 |

| Standups | 4,983 | –0.43 | 1.05 | –8 | 4 |

| Sweeps | 4,983 | 0.00 | 0.34 | –2 | 2 |

| Clinch Control Time | 4,902 | 0.16 | 0.78 | –4 | 4 |

| Guard Control Time | 4,902 | 0.41 | 0.99 | –4 | 5 |

| Half Guard Control Time | 4,902 | 0.27 | 0.58 | –2 | 4 |

| Side Control Time | 4,902 | 0.13 | 0.42 | –2 | 4 |

| Mount Control Time | 4,902 | 0.05 | 0.27 | –1 | 4 |

| Back Control Time | 4,902 | 0.13 | 0.50 | –2 | 4 |

| Miscellaneous Control Time | 4,902 | 0.39 | 0.68 | –3 | 4 |

Note: Data is at the judge-round level. For all Zuffa-owned UFC, WEC, and Strikeforce events held in Nevada with scorecards tracked by FightMetric and unanimous judge agreement on the round winner. Sample size is slightly smaller for control time variables as some older events did not have Time In Position (TIP) tracked.

4Model

This paper uses a non-experimental difference-in-differences framework across time and local jurisdictions to examine the impact of judging criteria changes on 10-8 scores in MMA. Judge scoring decisions are estimated using a logit model over a sample of rounds where all three judges unanimously agreed upon the winner. In this context, suppose the observable 10-8 and 10-9 scoring decisions derive from a latent judging preference variable y* specified as

(1)

for the 2016–2019 sample period, where jgt denotes judge-round j in group g in time period t. T1 is an indicator variable equal to one in the new judging criteria time period of 2017–2019, G is an indicator variable equal to one when judge-bouts are scored by the group of interest, and X is a vector of 29 differenced fighter performance statistics serving as controls. As in Gift (2018a), all regression results employed clustered standard errors at the bout level.

The 2001–2019 sample period utilizes only one group, Nevada judges, and tests for apparent changes in 10-8 scoring over the longest time frame of 2001–2019 with the model

(2)

where T2 is a categorical variable identifying the three time periods of interest for 10-8 judging in MMA: 2001–2012, 2013–2016, and 2017–2019.

5Empirical results

5.12016–2019 sample period

A difference-in-differences framework is utilized in the 2016–2019 sample period, allowing for the possibility that certain groups of judges were influenced more effectively by the 2017 change in 10-8 judging criteria. A number of reasons could lead to differences across judging groups. As Panel 1 of Table 4 shows, the number of unanimous UFC judge-rounds scored varies greatly across jurisdictions. Thus, judges in some areas, such as the top three in Nevada, New York, and California, may have more annual repetitions applying the criteria in major MMA events. Another possibility is awareness and training. Certain jurisdictions may devote more effort towards being at the forefront of rule and criteria changes, and either require or encourage judges to receive training more regularly. And the trainers themselves may have an effect. The top referee and judge in the sport, “Big” John McCarthy, whose COMMAND officials training program is the premier provider of ABC-certification, resided in California and Nevada throughout both sample periods. While McCarthy would regularly travel as the top official in the sport, it is possible he had more frequent interactions with California and Nevada officials.

Table 4

Judge-rounds scored in the 2016-2019 sample period

| Panel 1 | State or Local Jurisdiction | Judge-Rounds Scored | Percent | Panel 2 | Judge | Rounds Scored | Percent |

| 1. | Nevada, USA | 1,080 | 18.1% | 1. | Sal D’Amato | 516 | 8.6% |

| 2. | New York, USA | 480 | 8.0% | 2. | Derek Cleary | 470 | 7.9% |

| 3. | California, USA | 336 | 5.6% | 3. | Chris Lee | 381 | 6.4% |

| 4. | England, U.K. | 291 | 4.9% | 4. | Jeff Mullen | 215 | 3.6% |

| 5. | Texas, USA | 213 | 3.6% | 5. | Marcos Rosales | 194 | 3.2% |

| 6. | Arizona, USA | 177 | 3.0% | 6. | Glenn Trowbridge | 163 | 2.7% |

| 7. | Pennsylvania, USA | 144 | 2.4% | 7. | Dave Hagen | 153 | 2.6% |

| 8. | Sao Paulo, Brazil | 132 | 2.2% | 8. | Tony Weeks | 153 | 2.6% |

| 9. | Missouri, USA | 126 | 2.1% | 9. | Ben Cartlidge | 140 | 2.3% |

| 10. | Tennessee, USA | 126 | 2.1% | 10. | Junichiro Kamijo | 126 | 2.1% |

| 11. | Hamburg, Germany | 123 | 2.1% | 11. | Michael Bell | 123 | 2.1% |

| 12. | Distrito Federal, Mexico | 120 | 2.0% | 12. | Eric Colon | 122 | 2.0% |

| 13. | Illinois, USA | 117 | 2.0% | 13. | Paul Sutherland | 121 | 2.0% |

| 14. | Georgia, USA | 111 | 1.9% | 14. | Howard Hughes | 110 | 1.8% |

| 15. | Zuid-Holland, Netherlands | 102 | 1.7% | 15. | Guilherme Bravo | 105 | 1.8% |

| 16. | Victoria, Australia | 99 | 1.7% | 16. | Mark Collett | 101 | 1.7% |

| 17. | Ceara, Brazil | 93 | 1.6% | 17. | Dave Tirelli | 100 | 1.7% |

| 18. | Alberta, Canada | 90 | 1.5% | 18. | Cardo Urso | 94 | 1.6% |

| 19. | Florida, USA | 81 | 1.4% | 19. | Brian Puccillo | 87 | 1.5% |

| 20. | New Jersey, USA | 78 | 1.3% | 20. | Ric hard Winter | 86 | 1.4% |

| 21. | Rio De Janeiro, Brazil | 78 | 1.3% | 21. | Doug Crosby | 76 | 1.3% |

| 22. | New South Wales, Australia | 75 | 1.3% | 22. | Evan Field | 73 | 1.2% |

| 23. | South Australia, Australia | 69 | 1.2% | 23. | Andy Roberts | 70 | 1.2% |

| 24. | Idaho, USA | 66 | 1.1% | 24. | Charlie Keech | 69 | 1.2% |

| 25. | Wisconsin, USA | 66 | 1.1% | 25. | Hallison Pontes | 63 | 1.1% |

| 26. | Colorado, USA | 60 | 1.0% | 26. | Anthony Dimitriou | 58 | 1.0% |

| 27. | New Brunswick, Canada | 60 | 1.0% | 27. | Adalaide Byrd | 54 | 0.9% |

| 28. | Virginia, USA | 60 | 1.0% | 28. | Ron McCarthy | 54 | 0.9% |

| 29. | Moscow, Russia | 57 | 1.0% | 29. | Andreas Gruner | 49 | 0.8% |

| 30. | Oklahoma, USA | 57 | 1.0% | 30. | Pawel Harasim | 49 | 0.8% |

| All Others | 1,209 | 20.2% | All Others | 1,801 | 30.1% | ||

| Total | 5,976 | 100.0% | Total | 5,976 | 100.0% |

Note: Panel 1 shows the Top 30 judge-rounds scored by state or local jurisdiction. Panel 2 shows the Top 30 rounds scored by individual judge. For all UFC events with scorecards tracked by FightMetric and unanimous judge agreement on the round winner.

It should be noted that some of the 2017 changes to the Unified Rules of MMA were controversial. In addition to amending the judging criteria, the ABC also approved changes to the composition of fouls in the sport. Specifically, the ABC altered the definition of a grounded fighter and removed a foul for heel strikes to the kidney, among other less controversial changes. Referred to generally as MMA’s “new rules,” many states adopted the ABC-approved new set of fouls, but others did not. Hence, the “rules” of professional MMA could vary depending on the state or jurisdiction in which an event was held. This led to confusion among UFC announcers and fans as to whether the new –and uncontroversial –judging criteria were also in effect in jurisdictions which did not fully adopt the new set of fouls. Since 10-8 scoring involved a change in criteria rather than a change to the set of fouls, “all” judges should have been using the new standard in the 2017–2019 sample period “as a fluid criteria to adjudicate a round,” according to Jerin Valel of the COMMAND program (Gift, 2018b). Yet, as noted above, it is possible groups of judges were influenced differently by the new criteria.

Given the possibilities for different treatment effects of the 10-8 criteria change across jurisdictions, the first group examined is the top three scoring states in the data (see Table 4, Panel 1) relative to all other jurisdictions. Hence, G equals one when a judge-round is scored in Nevada, New York, or California and zero otherwise.

Table 5 presents difference-in-difference regression results for the three groups that will be examined in this study. While results from the fighter performance control variables are not the primary focus, they display strong consistency across the three groupings and appear to make economic sense. The most influential performance factor for a 10-8 score is knocking the opponent down. Also influential are having dominant (i.e., controlling) positions, damaging the opponent’s face, attempting submissions, and landing power strikes to the head, body, and legs.

Table 5

Logit regressions of 10-8 Score for the 2016–2019 sample period

| Independent Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||||

| (NV/CA/NY Group) | (Traveling Judge Group) | (NV Judge Group) | |||||||

| Beta | S.E. | AME | Beta | S.E. | AME | Beta | S.E. | AME | |

| 2017–2019 Period | 0.695*** | 0.258 | 1.175*** | 0.268 | 1.274*** | 0.300 | |||

| Group Indicator | 0.382 | 0.365 | 1.311*** | 0.312 | 1.351*** | 0.320 | |||

| 2017–2019 Period×Group | –0.247 | 0.413 | –1.200*** | 0.349 | –1.223*** | 0.360 | |||

| Head Jabs Landed | 0.046*** | 0.010 | 0.2% | 0.047*** | 0.009 | 0.2% | 0.047*** | 0.009 | 0.2% |

| Head Jabs Missed | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.0% | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.0% | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.0% |

| Head Power Landed | 0.121*** | 0.011 | 0.5% | 0.121*** | 0.011 | 0.5% | 0.122*** | 0.011 | 0.5% |

| Head Power Missed | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.0% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.0% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.0% |

| Body Jabs Landed | –0.019 | 0.024 | –0.1% | –0.021 | 0.023 | –0.1% | –0.022 | 0.023 | –0.1% |

| Body Jabs Missed | –0.060 | 0.073 | –0.3% | –0.038 | 0.072 | –0.2% | –0.047 | 0.072 | –0.2% |

| Body Power Landed | 0.065*** | 0.023 | 0.3% | 0.067*** | 0.023 | 0.3% | 0.068*** | 0.023 | 0.3% |

| Body Power Missed | 0.009 | 0.054 | 0.0% | 0.011 | 0.055 | 0.0% | 0.008 | 0.055 | 0.0% |

| Leg Jabs Landed | –0.012 | 0.022 | –0.1% | –0.010 | 0.021 | 0.0% | –0.009 | 0.021 | 0.0% |

| Leg Jabs Missed | –0.172* | 0.092 | –0.8% | –0.183** | 0.091 | –0.8% | –0.181** | 0.092 | –0.8% |

| Leg Power Landed | 0.099*** | 0.026 | 0.4% | 0.098*** | 0.025 | 0.4% | 0.097*** | 0.025 | 0.4% |

| Leg Power Missed | 0.117* | 0.066 | 0.5% | 0.117* | 0.067 | 0.5% | 0.116* | 0.067 | 0.5% |

| Knockdowns | 1.262*** | 0.177 | 5.6% | 1.288*** | 0.181 | 5.6% | 1.289*** | 0.180 | 5.6% |

| Damage | 0.431** | 0.220 | 1.9% | 0.454** | 0.220 | 2.0% | 0.439** | 0.220 | 1.9% |

| Takedown Slams | 0.011 | 0.197 | 0.1% | 0.001 | 0.200 | 0.0% | –0.002 | 0.200 | 0.0% |

| Takedowns Landed (No Slam) | –0.065 | 0.140 | –0.3% | –0.043 | 0.140 | –0.2% | –0.038 | 0.140 | –0.2% |

| Takedowns Missed | –0.070 | 0.053 | –0.3% | –0.080 | 0.053 | –0.4% | –0.082 | 0.053 | –0.4% |

| Submission Chokes Attempted | 0.440*** | 0.150 | 1.9% | 0.442*** | 0.154 | 1.9% | 0.454*** | 0.154 | 2.0% |

| Submission Locks Attempted | 0.665** | 0.213 | 2.9% | 0.662*** | 0.221 | 2.9% | 0.669*** | 0.214 | 2.9% |

| Tight Submission | 0.364 | 0.439 | 1.6% | 0.380 | 0.418 | 1.7% | 0.405 | 0.420 | 1.8% |

| Standups | –0.036 | 0.142 | –0.2% | –0.030 | 0.142 | –0.1% | –0.025 | 0.143 | –0.1% |

| Sweeps | –0.160 | 0.226 | –0.7% | –0.141 | 0.221 | –0.6% | –0.125 | 0.219 | –0.5% |

| Clinch Control Time | 0.307** | 0.144 | 1.4% | 0.313** | 0.146 | 1.4% | 0.317** | 0.145 | 1.4% |

| Guard Control Time | 0.396*** | 0.124 | 1.7% | 0.409*** | 0.126 | 1.8% | 0.416*** | 0.127 | 1.8% |

| Half Guard Control Time | 0.748*** | 0.134 | 3.3% | 0.754*** | 0.130 | 3.3% | 0.756*** | 0.130 | 3.3% |

| Side Control Time | 0.681*** | 0.155 | 3.0% | 0.675*** | 0.154 | 3.0% | 0.670*** | 0.153 | 2.9% |

| Mount Control Time | 0.824*** | 0.286 | 3.6% | 0.838*** | 0.291 | 3.7% | 0.821*** | 0.290 | 3.6% |

| Back Control Time | 0.911*** | 0.123 | 4.0% | 0.921*** | 0.122 | 4.0% | 0.905*** | 0.122 | 4.0% |

| Miscellaneous Control Time | 0.770*** | 0.117 | 3.4% | 0.767*** | 0.112 | 3.4% | 0.759*** | 0.112 | 3.3% |

| Constant | –6.304*** | 0.288 | –6.844*** | 0.300 | –6.951*** | 0.328 | |||

| N | 5,976 | 5,976 | 5,976 | ||||||

Note: Standard errors are clustered at the bout level. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

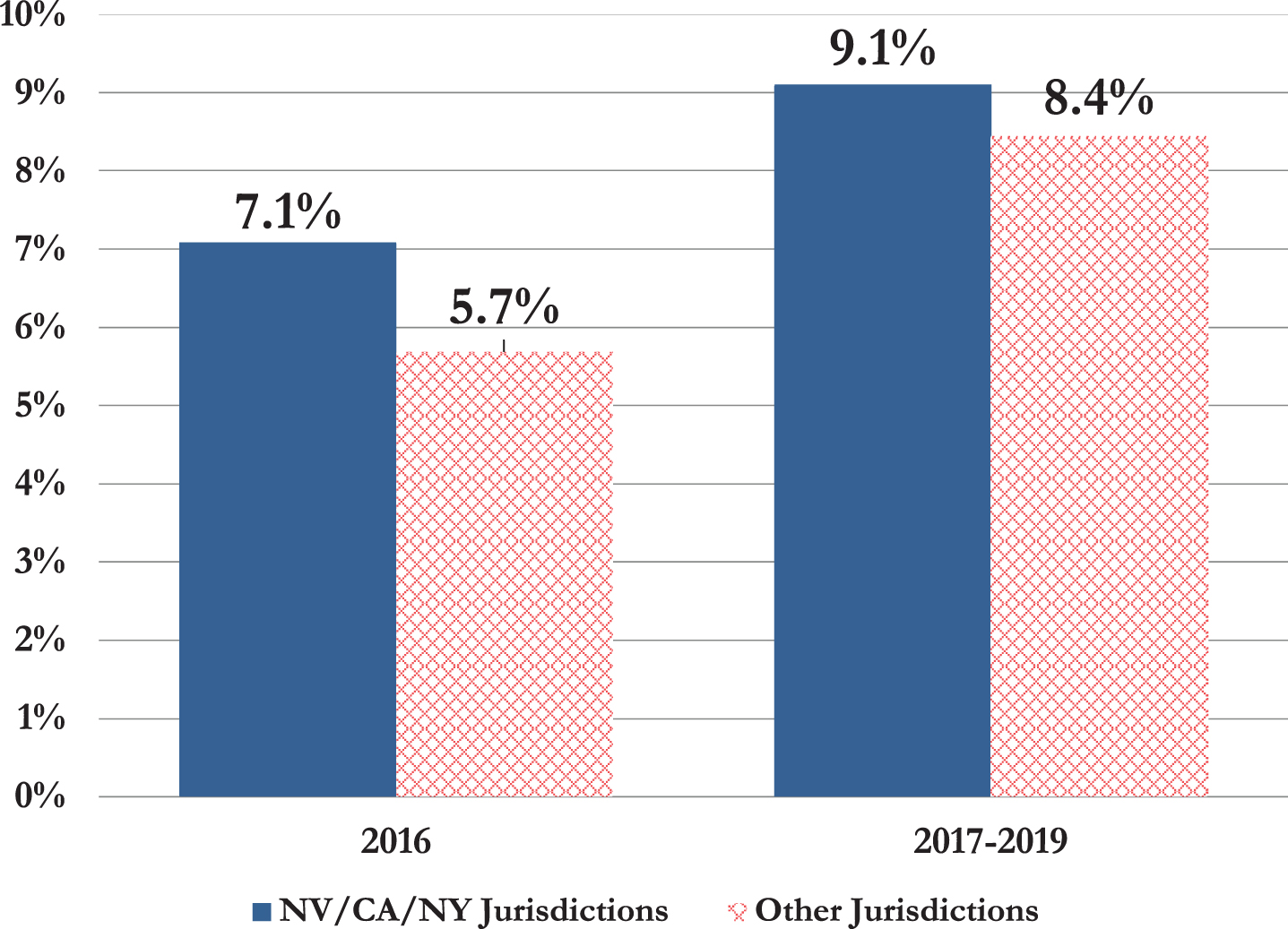

The difference-in-difference effect is the time-group interaction, which is negative and insignificant for the NV/CA/NY grouping. Figure 2 presents the results visually, showing the predicted probabilities of a 10-8 score in the four time-group combinations. While 10-8 probabilities increased in each group over time, the change in non-NV/CA/NY jurisdictions was the only with statistical significance. NV/CA/NY judges appeared to already score 10-8s more frequently in 2016, and there was not a significant difference in how scoring probabilities between each group changed over time.

Fig. 2

Estimated 10-8 Score probabilities by jurisdiction groups in the 2016–2019 sample period. Note: For all UFC events with scorecards tracked by FightMetric and unanimous judge agreement on the round winner.

Since judges do not always work exclusively in their primary jurisdiction, and certain judges travel extensively, two other groupings are examined. In a 2018 interview, John McCarthy described “traveling judges” as those who frequently work events in different jurisdictions for major promotions such the UFC and Bellator, sometimes specifically at the promoter’s request. McCarthy noted that traveling judges have figured out the scoring criteria, “and no matter where they are or where they go, they’re using that criteria” (Gift, 2018c)

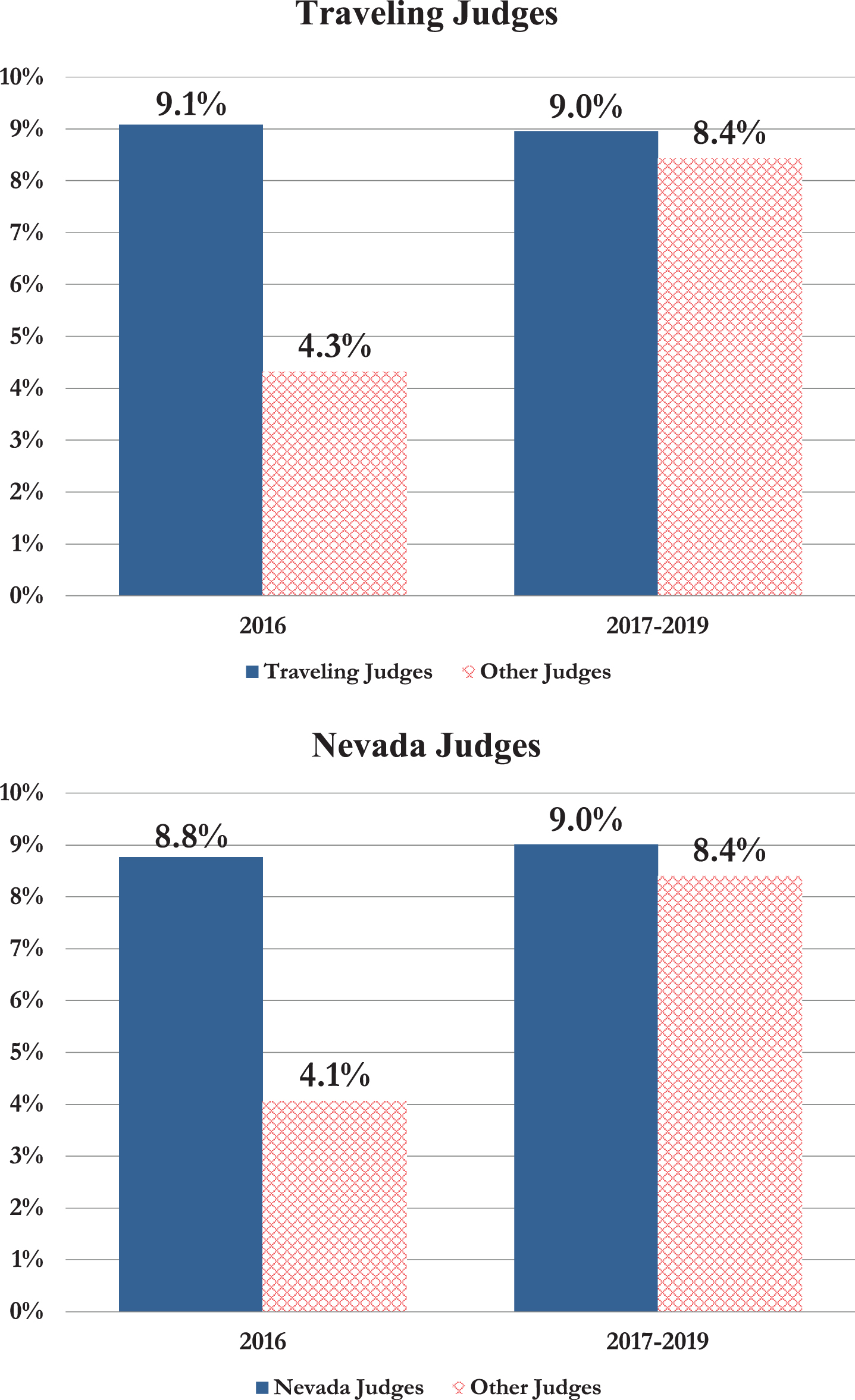

One would expect traveling judges to be at the forefront of the sport’s regulatory evolution, no matter the jurisdiction. In addition, they interact with local judges as they travel, potentially transferring knowledge before events begin or at the conclusion when officials typically debrief. A traveling judge is defined as any NV/CA/NY judge who appears in two of the three states during the sample period. 10 judges qualified for traveling status, with nine of those 10 judges appearing in the top 11 of rounds scored as shown in Panel 2 of Table 4.8 For this second grouping, G equals one when a judge-round is scored by a traveling judge, regardless of jurisdiction, and zero otherwise. As shown in Table 5, there is a significant difference-in-difference effect between traveling and all other judges. The negative coefficient on the time-group interaction might seem to indicate that traveling judges became less likely to score 10-8 rounds in 2017–2019 than their counterparts, but Fig. 3 helps to better interpret the results.

Fig. 3

Estimated 10-8 Score probabilities by judge type groups in the 2016–2019 sample period. Note: For all UFC events with scorecards tracked by FightMetric and unanimous judge agreement on the round winner.

As the top portion of Fig. 3 shows, traveling judges had essentially already liberalized their 10-8 scoring in 2016 before the new criteria went into effect. While not effective until January 1, 2017, the criteria were publicized and passed a vote at the ABC annual meeting in early-August 2016. It is not unreasonable to believe the criteria were debated and discussed among top judges well in advance of the vote. Results suggest traveling judges –likely more in-tune to the regulatory evolution of the sport –had already internalized the new 10-8 scoring criteria in 2016 while other judges had not. Over time, non-traveling judges appear to have been effectively advised and trained on the new criteria, as their probability of scoring a 10-8 in a round with a unanimous winner increased to statistical parity with their traveling judge counterparts.

Since eight of the 10 traveling judges worked substantially in Nevada, a final analysis groups Nevada judges who worked in the state in the pre- and post- periods (2016 and 2017–2019) against all other judges. Results can be seen in Table 5 and bottom portion of Fig. 4 and are qualitatively the same as for traveling judges.

Fig. 4

Estimated 10-8 Score probabilities in the Nevada jurisdiction for the 2001–2019 sample period. Note: For all Zuffa-owned UFC, WEC, and Strikeforce events with scorecards tracked by FightMetric and unanimous judge agreement on the round winner.

5.22001–2019 sample period

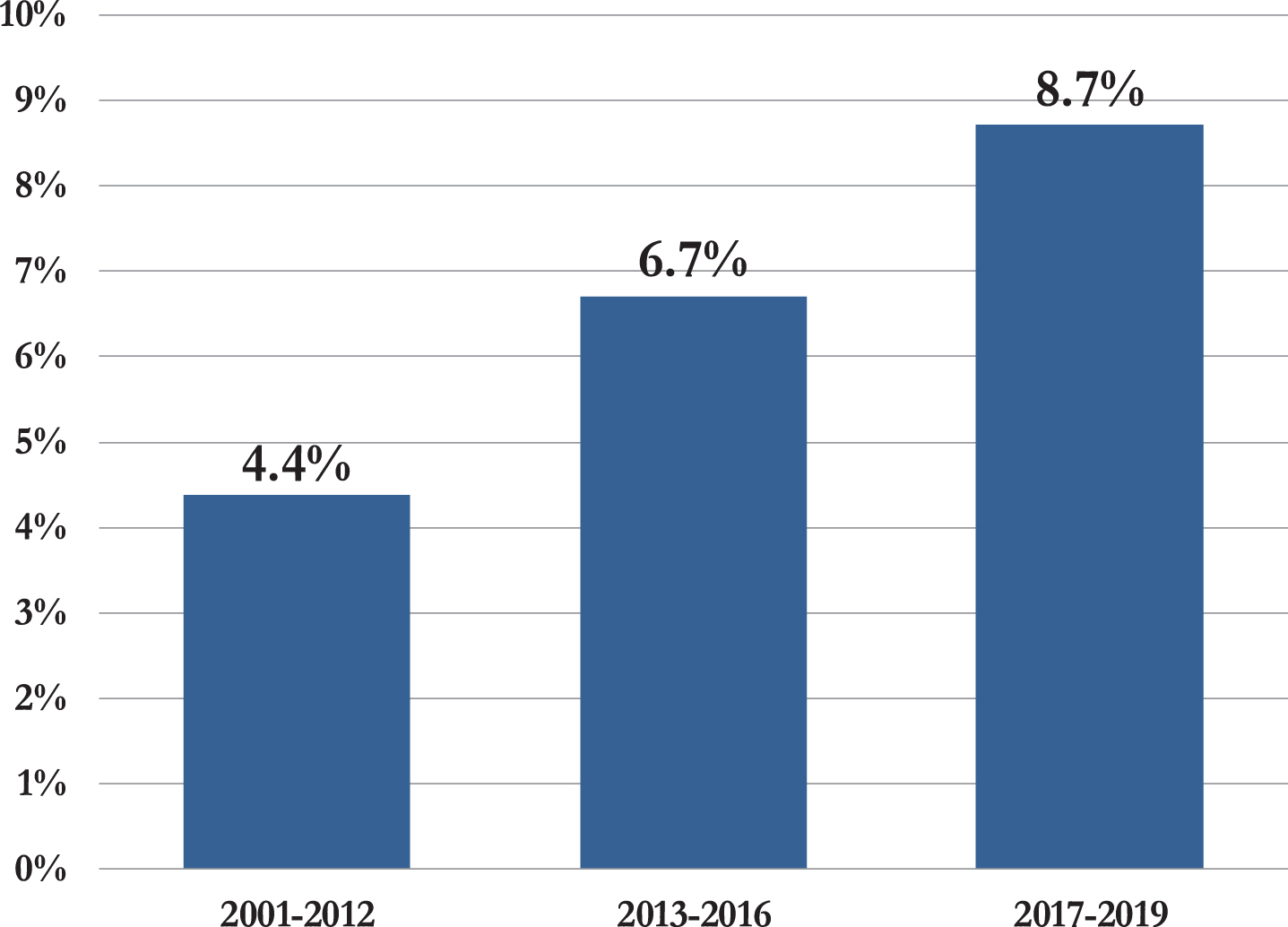

For a broader examination of the evolution of 10-8 scoring in MMA, judging in Nevada can be analyzed from 2001–2019. A difference-in-differences approach cannot be utilized, but differences over time can be examined as the 10-8 scoring criteria was liberalized from overwhelmingly dominant (2001–2012) to winning by a large margin with the Two D’s (2013–2016) to a new description of large margin and the Three D’s (2017–2019).

Table 6 shows that both time effects are positive and significant while Fig. 4 suggests that each effort to liberalize 10-8 scoring was effective in the state of Nevada. Controlling for fighters’ in-cage performances, the probability of a unanimous round winner earning a 10-8 score roughly doubled from 4.4 percent in 2001–2012 to 8.7 percent in 2017–2019.

Table 6

Logit regressions of 10-8 Score for the 2001–2019 sample period

| Independent Variables | Beta | S.E. | AME |

| 2013–2016 Period | 0.688** | 0.273 | |

| 2017–2019 Period | 1.125 *** | 0.290 | |

| Head Jabs Landed | 0.039 *** | 0.008 | 0.1% |

| Head Jabs Missed | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.0% |

| Head Power Landed | 0.139** | 0.015 | 0.5% |

| Head Power Missed | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.0% |

| Body Jabs Landed | –0.005 | 0.015 | 0.0% |

| Body Jabs Missed | 0.015 | 0.131 | 0.1% |

| Body Power Landed | 0.063** | 0.025 | 0.2% |

| Body Power Missed | 0.025 | 0.088 | 0.1% |

| Leg Jabs Landed | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.0% |

| Leg Jabs Missed | –0.051 | 0.155 | –0.2% |

| Leg Power Landed | 0.063 | 0.039 | 0.2% |

| Leg Power Missed | 0.081 | 0.106 | 0.3% |

| Knockdowns | 1.443 *** | 0.303 | 4.8% |

| Damage | 1.081 *** | 0.246 | 3.6% |

| Takedown Slams | 0.418 | 0.272 | 1.4% |

| Takedowns Landed (No Slam) | 0.359** | 0.161 | 1.2% |

| Takedowns Missed | 0.016 | 0.062 | 0.1% |

| Submission Chokes Attempted | 0.311 * | 0.161 | 1.0% |

| Submission Locks Attempted | 0.190 | 0.204 | 0.6% |

| Tight Submission | 0.570 | 0.484 | 1.9% |

| Standups | 0.370** | 0.162 | 1.2% |

| Sweeps | 0.567 | 0.354 | 1.9% |

| Clinch Control Time | –0.026 | 0.250 | –0.1% |

| Guard Control Time | 0.167 | 0.117 | 0.6% |

| Half Guard Control Time | 0.146 | 0.167 | 0.5% |

| Side Control Time | 0.684 ** | 0.149 | 2.3% |

| Mount Control Time | 0.270 | 0.208 | 0.9% |

| Back Control Time | 0.535 *** | 0.147 | 1.8% |

| Miscellaneous Control Time | 0.772 *** | 0.145 | 2.6% |

| Constant | –6.750 *** | 0.311 | |

| N | 4,902 | ||

Note: Standard errors are clustered at the bout level. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

6Discussion and conclusion

The Unified Rules of MMA have, in practice, become divided following two controversial changes to the set of fouls in the sport. A 2019 report had “at least 10” different MMA rulesets being used in North America (Raimondi, 2019). Yet changes to the 10-8 scoring criteria were uncontentious. How they have been implemented across a distributed regulatory network with marked differences in the frequency of events and potentially-divergent views on the foul portions of the Unified Rules is a relevant empirical question for fighters, coaches, fans, promoters, media, and the regulators themselves.

The most recent 10-8 judging criteria change in MMA was not an unanticipated shock. It was a process involving debate and discussion within the ABC’s MMA Rules and Regulations Committee, which may have influenced the findings of this study as traveling and Nevada judges appear to have been aware of the trajectory of the debate on 10-8 scores.

When analyzing the impact of the 2017 criteria change at the jurisdiction level, it appears the probability of 10-8 scoring increased over time. But I do not find a significant effect of the criteria change on the top three jurisdictions relative to all others. One potential reason for this finding is that top judges such as Sal D’Amato and Derek Cleary frequently travel across multiple jurisdictions and appeared many times in both jurisdictional groups.

When judges were grouped differently and classified as traveling/non-traveling or Nevada/non-Nevada judges, regardless of jurisdiction, results strongly supported a substantial initial difference between judging groups in 2016 prior to the criteria change. In each case, judges classified in a group likely closer to the forefront of the sport’s evolution (i.e., traveling and Nevada judges) were already scoring 10-8 rounds at more than double the likelihood of their counterparts. Possible explanations could include self-selecting into more frequent training, training with the top official in the sport, or more frequent attendance at ABC meetings and knowledge of the policy considerations of the Rules and Regulations Committee. Yet by the 2017–2019 period, all groups of judges had reached statistical parity as knowledge of and training on the new 10-8 scoring criteria appears to have been successfully executed across a distributed network of regulators.

One potential caveat to the analyses of this study is a possible selection problem around data availability. Not every athletic commission releases scorecards upon the conclusion of a fight. Thus, it is possible commissions which choose to release scorecards may also signal an emphasis on judging priorities within their jurisdiction. While non-traveling and non-Nevada judges appear to have quickly caught up with their counterparts, it is possible this selection mechanism could mask a resistance to change in jurisdictions where scorecards are private.

MMA is not a sport where rules change frequently. In fact, the word “rules” is a misnomer, better described as judging criteria and local regulations regarding fouls. Over 18 years in the present study, there have only been two changes to the criteria for scoring 10-8 rounds. And while regulators may disagree on certain elements of the Unified Rules, such as the applicable set of fouls, the evidence of this study suggests they have effectively coordinated and effectuated change with respect to a critical element of three- and five-round MMA fights: When to double a fighter’s reward for winning a round with a score of 10-8 instead of 10-9.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for helpful comments and suggestions from conference participants for the Western Economic Association and Eastern Economic Association, as well as two anonymous peer reviewers. I would like to thank Rami Genauer of FightMetric for data access and Steven Kelliher of Tapology for the personal interview.

References

1 | Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports. 2012. MMA judging criteria revisions. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from: https://www.abcboxing.com/Unified_Rules_of_MMA_Judging_Criteria.pdf |

2 | Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports. 2016. Unified Rules of Mixed Martial Arts. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from: https://www.abcboxing.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/unified-rules-mma-2019.pdf |

3 | Gift, P. (2018) a. BE Analytics: Crunching the numbers on the first full year of new 10-8 scoring. Bloodyelbow.com. Retrieved February 7, 2020, from: https://www.bloodyelbow.com/2018/2/1/16958692/be-analytics-crunching-numbers-2017-10-8-judging-scoring-criteria-ufc-mma-editorial |

4 | Gift, P. (2018) b. McCarthy clears up confusion surrounding judging criteria and MMA’s new rules. Bloodyelbow.com. Retrieved February 7, 2020, from: https://www.bloodyelbow.com/2018/3/6/17083716/referees-john-mccarthy-jerin-valel-judging-criteria-new-old-unified-rules-mma-interview |

5 | Gift, P. (2018) c. Performance evaluation and favoritism: evidence from mixed martial arts, Journal of Sports Economics 19: (8), 1147–1173. |

6 | Gift, P. (2019) a. Entertainment design in mixed martial arts: Does cage size matter? Journal of Applied Sport Management 11: (2), 11–26. |

7 | Gift, P. (2019) b. Performance bonuses and effort: Evidence from fight night awards in mixed martial arts, International Journal of Financial Studies 7: (1), 13. |

8 | Gift, P. (2020) . Moving the needle in MMA: On the marginal revenue product of UFC fighters, Journal of Sports Economics 21: (2), 176–209. |

9 | Kelliher, S. (2019) . Personal interview. |

10 | New Jersey State Athletic Control Board. 2001. Mixed Martial Arts Unified Rules of Conduct. Retrieved February 7, 2020, from: https://www.nj.gov/lps/sacb/docs/martial.html |

11 | Raimondi, M. (2017) . Click Debate: How will the new judging criteria affect how MMA bouts are scored? Retrieved February 7, 2020, from: https://www.mmafighting.com/2017/1/8/14200886/click-debate-how-will-the-new-judging-criteria-affect-how-mma-bouts-are-scored |

12 | Raimondi, M. (2019) . ABC survey: At least 10 different MMA rulesets being used in North America. Retrieved February 7, 2020, from: https://www.mmafighting.com/2019/4/16/18358920/abc-survey-at-least-10-different-mma-rulesets-being-used-in-north-america |

13 | Reams, L. & Shapiro, S. (2017) . Who’s the main attraction? Star power as a determinant of Ultimate Fighting Championship pay-per-view demand, European Sport Management Quarterly 17: (2), 132–151. |

14 | Tainsky, S. , Salaga, S. , & Santos, C. (2013) . Determinants of pay-per-view broadcast viewership in sports: The case of the Ultimate Fighting Championship, Journal of Sport Management 27: , 43–58. |

15 | USA Today 2008. MMA timeline. USAToday.com. Retrieved June 12, 2013, from: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/2008-05-29-mma-timeline_N.htm |

16 | Watanabe, N. (2012) . Demand for pay-per-view consumption of Ultimate Fighting Championship events, International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 11: , 225–238. |

17 | Watanabe, N. (2015) . Sources of direct demand: An examination of demand for the Ultimate Fighting Championship, International Journal of Sport Finance 10: , 26–41. |

Appendices

Appendix A

Excerpt of “MMA Judging Criteria/Scoring-

Approved August 2, 2016”

(Effective January 1, 2017; Emphasis and

capitalization in original)

10–8 Round

8.1A 10 –8 Round in MMA is where one fighter wins the round by a large margin

A 10 –8 round in MMA is not the most common score a judge will render, but it is absolutely essential to the evolution of the sport and the fairness to the fighters that judges understand and effectively utilize the score of 10 –8. A score of 10 –8 does not require a fighter to dominate their opponent for 5 minutes of a round. The score of 10 –8 is utilized by the judge when the judge sees verifiable actions on the part of either fighter. Judges shall ALWAYS give a score of 10 –8 when the judge has established that one fighter has dominated the action of the round, had duration of the domination and also impacted their opponent with either effective strikes or effective grappling maneuvers that have diminished the abilities of their opponent.

Judges must CONSIDER giving the score of 10 –8 when a fighter shows dominance in the round even though no impactful scoring against the opponent was achieved. MMA is an offensive based sport. No scoring is given for defensive maneuvers. Using smart, tactically sound defensive maneuvers allows the fighter to stay in the fight and to be competitive. Dominance of a round can be seen in striking when the losing fighter continually attempts to defend, with no counters or reaction taken when openings present themselves. Dominance in the grappling phase can be seen by fighters taking DOMINANT POSITIONS in the fight and utilizing those positions to attempt fight ending submissions or attacks. If a fighter has little to no offensive output during a 5 minute round, it should be normal for the judge to consider awarding the losing fighter 8 points instead of 9.

Judges must CONSIDER giving the score of 10 –8 when a fighter IMPACTS their opponent significantly in a round even though they do not dominate the action. Effectiveness in striking or grappling which leads to a diminishing of a fighter’s energy, confidence, abilities and spirit. All of these come as a direct result of negative impact. When a fighter is hurt with strikes, showing a lack of control or ability, these can be defining moments in the fight. If a judge sees that a fighter has been significantly damaged in the round the judge should CONSIDER the score of 10 –8.

Impact

A judge shall assess if a fighter impacts their opponent significantly in the round, even though they may not have dominated the action. Impact includes visible evidence such as swelling and lacerations. Impact shall also be assessed when a fighter’s actions, using striking and/or grappling, lead to a diminishing of their opponents’ energy, confidence, abilities and spirit. All of these come as a direct result of impact. When a fighter is impacted with strikes, by lack of control and/or ability, this can create defining moments in the round and shall be assessed with great value.

Dominance

As MMA is an offensive based sport, dominance of a round can be seen in striking when the losing fighter is forced to continually defend, with no counters or reaction taken when openings present themselves. Dominance in the grappling phase can be seen by fighters taking dominant positions in the fight and utilizing those positions to attempt fight ending submissions or attacks. Merely holding a dominant position(s) shall not be a primary factor in assessing dominance. What the fighter does with those positions is what must be assessed.

Duration

Duration is defined by the time spent by one fighter effectively attacking, controlling and impacting their opponent; while the opponent offers little to no offensive output. A judge shall assess duration by recognizing the relative time in a round when one fighter takes and maintains full control of the effective offense. This can be assessed both standing and grounded.

Notes

1 Non-title fights in MMA are sometimes scheduled for five rounds. For example, all main event matchups in the UFC, whether title or non-title fights, are scheduled for five rounds unless there are extenuating circumstances such as a short-notice replacement.

2 In the 2016-2019 sample period of the present study, 90.4% of bouts were scheduled for three rounds while only 9.6% where scheduled for five.

3 While many states utilized these Unified Rules of MMA, they were officially codified by the ABC in 2009.

4 The WEC and Strikeforce, and their associated fighters, were absorbed into the UFC in 2010 and 2013, respectively.

5 MMA was legally sanctioned in Nevada in 2001 and California in 2006.

6 In the second round of Chris Leben vs. Patrick Cote at UFC Fight Night 1, two judges scored the round for Cote (10-9 and 10-8) while the third judge scored a 10-9 for Leben.

7 While a score of 10-7 is technically possible, it occurs when a judge believes the referee did not do his or her job and a “stoppage is warranted” (Raimondi, 2017, pp. 4). Out of 10,926 judge-rounds in the overall sample, only three were scored a 10-7, each time by a single judge. In practice, the three 10-7 scores essentially served as very decisive 10-8s, and therefore are coded as 10-8 scores in the paper. Results are qualitatively the same and virtually identical when the three 10-7 rounds are excluded from the analysis.

8 The 10 traveling judges are Michael Bell, Derek Cleary, Sal D’Amato, Dave Hagen, Junichiro Kamijo, Chris Lee, Ron McCarthy, Jeff Mullin, Marcos Rosales, and Glenn Trowbridge. Ron McCarthy scored the fewest rounds in the sample and appears at position 28. But as John McCarthy’s son, it is reasonable to expect him to be at the leading edge of judging evolution in the sport.