Physician distress: Where are we and what can be done

Abstract

Depression, suicidal ideation, burnout, and moral injury are on the rise among physicians. Depression and suicidal ideation are mental health disorders that result from multiple interacting factors including biological vulnerabilities and acute stressors. Medical treatment for depression and suicidal ideation is critical to interrupt the potentially deadly progression to suicide that occurs when one’s ability to find hope and other solutions is clouded by despair. Yet, stigma and perceived stigma of seeking treatment for mental health disorders still plagues medical providers. Transitions during medical training and practice can be particularly vulnerable time periods, though newer evidence suggests that overall, physicians are not at an increased risk of suicide compared to the general population. While burnout and moral injury are common among rehabilitation physicians, unlike depression, they are not directly associated with suicidal ideation. Opportunities for continued improvement in mental health resources and institutional support exist across the spectrum from medical student to staff physician. With wellness now increasingly supported and promoted by various medical organizations and recognition of the importance of access to effective mental health treatment, regaining hope and positivity while restoring resiliency in physicians, trainees, and medical students is possible.

1Introduction

In the United States (US), depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide rates have risen in the general population. Adult antidepressant use as measured over a 30-day period in the US was 1.8% from 1999 to 2002 and markedly increased to 13.2% by 2015-2018 [1, 2]. Suicide rates reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention increased by a striking 37% between 2000 and 2021 [3]. Historically, physician suicide rates were believed to be even greater than the general population [4–6]. However, more recent evidence suggests that physicians are not at an increased rate of suicide compared to the general population, though there are certain vulnerable periods for physician death by suicide [7]. Regardless, an estimated 119 physicians die by suicide every year in the US [8]. Every one of these deaths is one physician death too many.

2Suicidal ideation and suicide risk

Suicidal ideation is one important warning sign for suicide. Suicidal ideation is a general term used to describe thoughts, wishes, and contemplations of suicide ranging from thoughts that one would be better if dead to having an actual suicide plan [9]. Though not always an indication of future suicide, suicidal ideation should always be addressed as it may be a sign of extreme distress [10, 11]. Physicians have a higher rate of suicidal ideation than the general population, though the rate of suicide is not increased [7, 12]. While most commonly associated with depression in the lay literature, suicidal ideation is not diagnostic for depression and can be present in many other mental health conditions [13]. Depression and unaddressed mental health concerns require medical attention. Depression and suicidal ideation can lead to suicide but are very treatable conditions.

Recent studies suggest gender differences related to physician suicide. Women physicians have an elevated suicide mortality risk compared to the general population. Conversely, male physicians have a lower rate of suicide compared to their non-physician peers, though male physicians who die by suicide still outnumber women at a proportion of 2 : 1 [14, 15]. In a study evaluating gender differences in suicide risk among medical students and physicians, female medical students and physicians at elevated risk of suicide, as indicated by Patient Health Questionaire-9 score > 15 or current suicidal ideation, had more severe depression and were more likely to report significant stress than men [16]. Male medical students and physicians at elevated risk of suicide were more likely to endorse suicidal ideation, intense anger, excessive alcohol use, or using other substances [16]. No significant difference has been found in ethnicity between physicians and non-physicians who die by suicide [15].

The presence of emotional exhaustion and lower self-valuation scores are associated with physician suicidal ideation [12]. Depressed mood, other mental health problems, suicidal ideation, previous suicide attempts, deaths of friends or family members, early childhood abuse, interpersonal problems, and physical health problems are all associated with suicide amongst medical students and physicians [15, 17, 18]. Beyond these personal and interpersonal characteristics and experiences, work related factors associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation or death by suicide include harassment, work disengagement, sickness presenteeism (working despite being sick), “problems at work,” and an individual’s belief they made a major medical error in the last three months [12, 15, 19, 20]. In fact, “known job problems” prior to suicide is one of the most robust contributors to physician suicide [15]. Importantly, protective work factors include the perception of empowering leadership and meaningful social connections [19, 21]. While work factors can contribute to the profound despair and hopelessness experienced by those with suicidal ideation, suicidal ideation and suicide are typically a result of multiple interacting factors including biological vulnerabilities. Acute stressors that outweigh someone’s ability to find other solutions besides suicide are never caused by a single thing (like work stress).

3Burnout

Distinctly different than depression, suicide, and suicidal ideation, but also a notable indication of distress in medical practice, is burnout. The World Health Organization describes burnout as an occupational phenomenon characterized by feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and reduced professional efficacy [22]. The estimated cost of physician burnout in the US is $4.6 billion [23]. Importantly, however, burnout should not be equated with depression or suicidality. In fact, after adjusting for the presence of depression, burnout is not directly associated with suicidal ideation. Burnout may exacerbate suicidal ideation in the presence of depression rather than by causing suicidal ideation or suicide directly [12]. Depression and suicidal ideation require medical attention. However, since burnout is not believed to increase suicide risk per se, some advocate that burnout may be safely addressed outside of the mental health care system [24].

Physicians who practice in the field of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) are not immune to burnout. PM&R residents who endorse a lack of adequate time for personal and family life were most likely to be burned out [25]. Over half of practicing PM&R physicians also endorse experiencing burnout [26, 27], with the top three causes being 1) increasing regulatory demands, 2) workload and job demands, and 3) practice inefficiency and lack of resources. Higher burnout rate was associated with elevated levels of job stress and working more hours per week [27]. While the vast majority of respondents in these studies are likely to be PM&R physicians who care primarily for adults, it is likely that these also ring true for physicians in pediatric PM&R practice.

4Moral injury

Over the past several years, physicians have increasingly identified moral injury as the cause of burnout symptoms, whereas previously burnout might have been blamed on an individual’s own personal frailty. While moral dilemmas are ubiquitous in medicine, moral injury refers to the psychological distress associated with one’s own actions (or lack of them) when they are at odds with one’s beliefs or values in association with a medical system that constrains the physician’s ability to best care for the patient [27–29]. The concept of moral injury shifts the blame of burnout from the physician and their “inability to cope” to healthcare organizations and systems.

Many stressors may contribute to moral injury and burnout in physicians. One notable stressor is metrics that are unrealistic or beyond the physician’s control [26, 28]. In many institutions, the value of the physician is judged by the number of relative value units (RVUs) they generate and/or positive responses on patient satisfaction forms instead of medically relevant outcomes [30]. An overemphasis on RVU productivity encourages an assembly line approach to medical care, promoting shorter appointments, less time for empathetic interactions, and dissatisfaction with interactions [31]. It may hinder physicians’ abilities to comprehensively care for medically complex patients, like those frequently seen by pediatric rehabilitation physicians. Because follow up care generates fewer RVUs than new consultations or a procedural-only practice [32], over-reliance on RVUs as a defining metric for being a good physician by institutions also creates bias that can be harmful to patients. This bias includes greater difficulty for patients to get an appointment if they require longer appointment times or more than one clinic appointment, such as for those who are medically complex, require an interpreter, have communication impairments, or simply require ongoing follow-up. This may result in a physician struggling to balance the needs of the institution, the needs of the patient, and the needs of timely completion of documentation and billing, contributing to moral injury.

The true value of the popular metric of patient satisfaction can also be deceptive. A satisfied patient does not necessarily mean that the patient had good medical or rehabilitation care [33]. It may simply mean that the patient and family liked the provider. Patient satisfaction can also be related to the amount of time a provider is able to spend with the patient, or ease of parking, or stress of getting out the door to get to an early morning appointment. Much of this is out of the control of the physician and can exacerbate moral injury.

5Mental health stigma

Unfortunately, when physicians are under mental duress, many have a reluctance to seek help. In 2021, a national study of nearly 5,000 US physicians found those with suicidal ideation were less likely to seek help than physicians without suicidal ideation [12]. There continues to be a powerful stigma associated with mental illness among physicians and physicians-in-training, which contributes to a reduction in help-seeking behavior [34].

Historically, the medical licensure process did little to reduce concern of the stigma of seeking medical care for mental health concerns among physicians. Fortunately, many state medical boards have made changes in licensure questions to better comply with recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) with over 70% only asking about current conditions causing impairment and avoiding questions about mental health diagnoses or those distinguishing between physical and mental health conditions [35]. Despite improvements, most state medical boards have not fully implemented all FSMB recommendations [35, 36]. Other sources of hesitancy for seeking care include fears about discrimination in hospital credentialing and consequences related to personal and liability insurance if a mental health diagnosis is disclosed [6]. Despite the progress made, the concern about the potential impact of mental health diagnosis on medical licensure remains a barrier to some physicians who might otherwise seek treatment. In fact, when asked, nearly 40% of physicians reported that they would avoid seeking medical care for a mental health condition because of concerns about their medical licensure [37]. Physician training programs are actively working to provide up to date and accurate information regarding mental health and licensing as medical groups and national laws drive states to update medical licensing policies [38].

Reduced mental health help-seeking in medical students and residents stems from fear of documentation in their academic record, negative perceptions from others, and concerns about privacy, confidentiality, and risk to future career opportunities [39–41]. In a 2015 study, nearly 60% of medical students with burnout felt that residency program directors would pass over an application if they were aware that a student had a mental health condition [40]. In this same study, about 50% of medical students agreed that their peers and patients held negative attitudes about mental illness and that patients would not want them as their doctor if they knew that the student had been treated for a mental health concern [40]. While training programs continue to improve mental health and wellness supports for medical students and physicians in-training, these negative perceptions may contribute to students and trainees not accessing support and treatment.

The culture of medicine and physicians themselves have contributed to the stigma of mental health conditions [42]. There is a history of shame and silence surrounding mental illness in medicine, including a reluctance to disclose a concern to others, and this needs to change. Furthermore, access to care has been shown to be a major concern related to reduced help seeking in medical students and physicians [43]. This includes finding time for an appointment that fits into a busy schedule. Physicians are reluctant to take time off and shift the burden of work to their colleagues, while students and physicians-in-training may worry about missing learning opportunities from missed procedures or patient care.

6Transitional vulnerability

Vulnerable times for death by suicide are not unique to medicine. Studies in the military population show an increased rate of suicide immediately following separation compared to active-duty service members [44]. In the general population, depression is common in young adults [45], an age when many are going through medical training and embarking on their medical careers. In medicine, data on medical cohorts suggest that times of transition may be associated with higher rates of suicide. Burnout and depression rise dramatically during medical school, with medical students having higher rates of depression and burnout than the general population, despite the opposite being true at medical school matriculation [46, 47]. During internship, the prevalence of suicidal ideation increases [17]. On the other hand, there is a glimmer of good news, as deaths by suicide in medical and surgical residents in the US is lower than the age and gender matched general population [48]. Suicide during residency is more likely to occur early in residency and in the first and third quarters of the year, possibly related to the stress of transitions from medical school to residency and from each residency year to the next [48].

At completion of medical training, both work and personal stresses can build in a short period. Questions about mental health may be encountered when seeking state medical licensure [35–37]. The open and proactive approach to addressing mental health and encouraging well-being during medical training may become barriers to state licensing and securing a job. Physicians must pass high-stakes examinations after completion of residency and fellowship to become board certified. Deferred student loan debt from undergraduate and medical school may need to be addressed. Many new physicians move to a medical practice or medical system where they have no personal connections or support. In a different medical system, they need to navigate a new electronic medical record while also learning to shoulder the sole responsibility for patient care. New doctors in an academic or university practice might also experience the added pressure of expectations for tenure track and academic promotion.

7The path forward

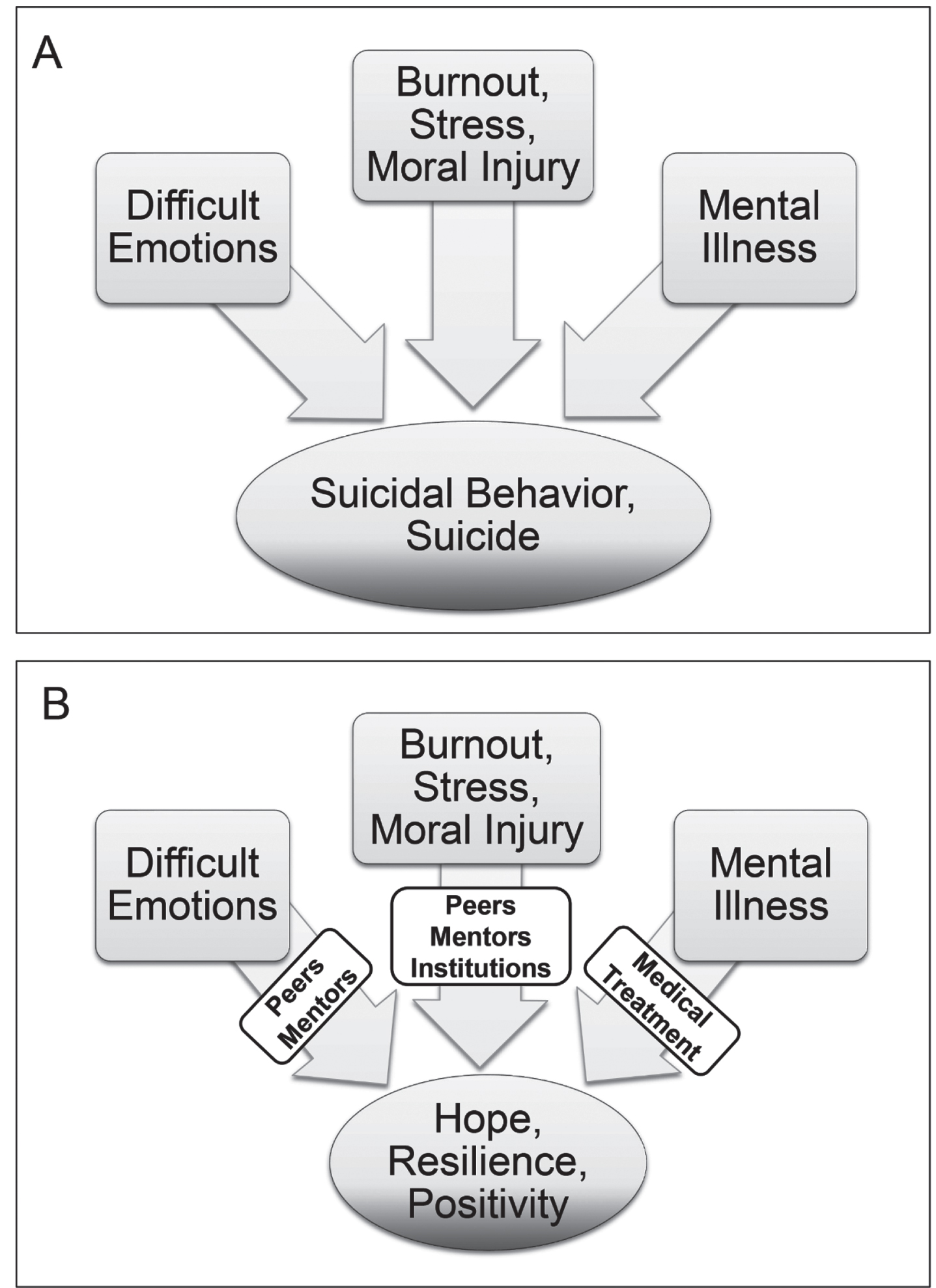

The American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) have increased emphasis on addressing modifiable factors in physician training that affect wellness (Fig 1). For example, there is increased acknowledgement of and training around the normal emotions experienced during difficult conversations with patients, bad patient outcomes, and disagreements among care providers. At the medical student, intern, resident, and fellow levels, efforts to address modifiable institutional factors to mitigate burnout include implementing duty hours, a culture of safety, an emphasis on adequate sleep and self-care, and attention to personal medical appointments [49–51]. Basic well-being concepts of mindfulness, self-awareness, self-care, self-compassion, cognitive flexibility and reframing, conflict resolution, emotional regulation, appreciation, gratitude, and maintaining empathy are increasingly used as cornerstones in medical school and residency training. These well-being concepts also highlight the complex and coexistent biological factors, personal factors, and work factors that can result in an individual’s distress when mixed with acute stressors. Training related to safe and diverse learning and work environments raises awareness of unintentional bias and microaggressions and promotes inclusion and belonging. Faculty are encouraged to role model sharing of their own personal mental health experiences to help decrease the stigma of mental health issues and increase medical trainee’s help-seeking behavior [52].

Fig. 1

In physician training, modifiable factors of difficult emotional situations, burnout, chronic stress, moral injury, and mental illness affect wellness and can lead to suicidal behavior and suicide in the setting of acute stressors (A) When this occurs, peer support, mentorship, institutional support and resources, and when needed, medical treatment should be utilized to change the outcome (B) These modifiable factors do not resolve at end of physician training but remain throughout a physician’s career necessitating ongoing vigilance and support.

Unfortunately, after training is completed, institutional support for physicians in these areas of well-being varies by specialty, employer, and geographical region. While the American Medical Association (AMA) does have some resources available [53], there is no standardization across the industry. More attention is being brought to this issue with the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act (P.L. 117-105), signed into law by President Biden on March 18, 2022 [54]. This law establishes initiatives to address mental health and resiliency of health care students, trainees, and professionals, such as promotion of evidence-informed strategies to improve well-being and a program to encourage health professionals to seek treatment [38]. A rollout of systematic interventions for physicians in clinical practice is in process due to this federal law, though how and when they are rolled out will vary across medical institutions.

A comprehensive approach to physician wellness is critical. Physician resilience and wellness are not entities to check off a list but rather continuous aspirational goals that require nurturing throughout training and one’s career. As one transitions from medical student to medical practice, wellness and resilience needs evolve. Yet, few organizations and institutions have a model of care for physicians that reflects the evolving wellness and resilience needs [55]. Furthermore, physician-led interventions appear to have only a small positive impact as compared to the greater impact when physician mental health and well-being are supported and prioritized at the organizational level [55, 56]. At an institutional level, providing education, resources, and protected time for physicians to learn and grow their skills to effectively work in and lead clinical care teams, communicate respectfully with all individuals, and give and receive feedback is especially important in the early career stage. It is critical to learn how to establish reasonable expectations for patients, colleagues, and oneself as well as set boundaries for work and life. With the goals of facilitating physician engagement, sense of purpose, and lifelong learning, professional development may include pathways or tracks for growth, recognition of success, and promotion in areas of interest.

Institutions can provide education and support, reduce burden, improve system efficiencies, and remove barriers to seeking mental health care. Stepping away from an emphasis on RVU and patient satisfaction metrics, particularly in an early stage of a physician’s career, can facilitate creation of clinical calendars with appointment lengths appropriate for the complexity of patients. This will facilitate comprehensive and patient-centered evaluations, discussion of all clinical options with patients and families, and adequate time for the patient and family to ask questions—all contributing to a higher level of patient care excellence and physician satisfaction. Institutions can support new physicians through a transition period that provides protected time for learning to navigate the medical record, identifying and meeting with clinical and academic mentors and collaborators, and creating or improving practice area(s) of interest.

As fellow physicians, we can also support each other. We need to check on each other. For our new colleagues, we can act to reduce loneliness, stress, uncertainty, and sense of disconnection that can occur when transitioning in one’s career or to a new organization. Ask about activities your new colleagues enjoy and help them (and their families) connect with organizations or groups in the community. Formal and informal mentorship programs facilitate connection and intentional career direction setting.

Most importantly, we can all speak up. If you see, hear, or notice something different about a colleague, ask how they are doing. Let them know why you are asking. Personal connections are important. They are humanizing. They take time but reduce isolation. They are critical in recognizing a colleague in distress and permitting that colleague to say something. Just as you do not need to be an emergency medicine physician to save a life through CPR, you do not need to be a mental health provider to save a life through showing earnest concern and compassion. Ignoring or downplaying the signs or symptoms of depression or suicidal ideation in oneself or colleagues can be just as deadly as ignoring or downplaying symptoms of a myocardial infarction or stroke. As physicians, we recognize the fundamental value of every patient’s life, and it is time we recognize the fundamental value of our own.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our physician colleagues, friends, and family who have been lost to suicide. If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, call or text 988 or go to 988lifeline.org.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical considerations

This study is exempt from Institutional Review Board approval.

Funding

None.

References

[1] | Health, United States, [2017]: Table [080]. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/data-finder.htm |

[2] | Brody DJ , Gu Q . Antidepressant use Among Adults in the United States, 2015-2018. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db377.htm |

[3] | Suicide Data and Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, US Department of Health & Human Services; 2023 [updated 2023 August 10]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html |

[4] | Aasland OG , Hem E , Haldorsen T , Ekeberg Ø . Mortality among Norwegian doctors 1960-2000. BMC Public Health. 2011 Mar;11:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-173 |

[5] | Bucknill JC , Tuke DH . Manual of Psychological Medicine: containing history, nosology, description, statistics, diagnosis, pathology, and treatment of insanity, with an appendix of cases. London: Churchill; 1858. |

[6] | Center C , Davis M , Detre T , et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. (2003) Jun 18; 289: (23). doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3161 |

[7] | Dyrbye LN , West CP , Satele D , et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. Mar. (2014) Mar;89: (3):443–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134 |

[8] | Gold KJ , Schwenk TL , Sen A . Physician Suicide in the United States:Updated Estimates from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Psychol Health Med. (2022) Aug;27: (7):1563–1575. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1903053 |

[9] | MB26.A Suicidal ideation. World Health Organizaiton; 2023. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/778734771 |

[10] | McHugh CM , Corderoy A , Ryan CJ , Hickie IB , Large MM . Association between suicidal ideation and suicide: meta-analyses of odds ratios, sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value. BJPsych Open. (2019) Mar;5: (2):e18. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2018.88 |

[11] | ten Have M , de Graaf R , van Dorsselaer S , et al. Incidence and course of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the general population. Can J Psychiatry. (2009) Dec;54: (12):824–33. doi: 10.1177/070674370905401205 |

[12] | Shanafelt TD , Dyrbye LN , West CP , et al. Suicidal Ideation and Attitudes Regarding Help Seeking in US Physicians Relative to the US Working Population. Mayo Clin Proc. (2021) Aug;96: (8):2067–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.01.033 |

[13] | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. |

[14] | Duarte D , El-Hagrassy MM , Couto TCE , Gurgel W , Fregni F , Correa H . Male and Female Physician Suicidality: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) Jun 1;77: (6):587–597. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0011 |

[15] | Ye GY , Davidson JE , Kim K , Zisook S . Physician death by suicide in the United States: 2012-2016. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) Feb;134: . doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.064 |

[16] | Pospos S , Tal I , Iglewicz A , et al. Gender differences among medical students, house staff, and faculty physicians at high risk for suicide: A HEAR report. Depress Anxiety. (2019) Oct;36: (10):902–920. doi: 10.1002/da.22909 |

[17] | Malone TL , Zhao Z , Liu T-Y , Song PXK , Sen S , Scott LJ . Prediction of suicidal ideation risk in a prospective cohort study of medical interns. PLoS One. (2021) Dec 2;16: (12):e0260620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260620 |

[18] | Marcon G , Massaro Carneiro Monteiro G , Ballester P , et al. Who attempts suicide among medical students? Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2020) Mar;141: (3):254–264. doi: 10.1111/acps.13137 |

[19] | Eneroth M , Gustafsson Sendén M , Løvseth LT , Schenck-Gustafsson K , Fridner A . A comparison of risk and protective factors related to suicide ideation among residents and specialists in academic medicine. BMC Public Health. (2014) Mar 22;14: :271. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-271 |

[20] | Gold KJ , Sen A , Schwenk TL . Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2013) Jan-Feb;35: (1):45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.08.005 |

[21] | Follmer KB , Jones KS . Mental Illness in the Workplace: An Interdisciplinary Review and Organizational Research Agenda. Journal of Management. (2017) ;44: (1):325–351. doi: 10.1177/0149206317741194 |

[22] | QD85 Burnout. World Health Organization; 2023. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f |

[23] | Han S , Shanafelt TD , Sinsky CA , et al. Estimating the Attributable Cost of Physician Burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. (2019) Jun 4;170: (11):784–790. doi: 10.7326/M18-1422 |

[24] | Menon NK , Shanafelt TD , Sinsky CA , et al. Association of Physician Burnout With Suicidal Ideation and Medical Errors. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) Dec 1;3: (12):e2028780. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28780 |

[25] | Bean AC , Schroeder AN , McKernan GP , et al. Factors Associated With Burnout in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Residents in the United States. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2022) Jul 1;101: (7):674–684. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001886 |

[26] | Bateman EA , Viana R . Burnout among specialists and trainees in physical medicine and rehabilitation: A systematic review. J Rehabil Med. (2019) Dec 16;51: (11):869–874. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2614 |

[27] | Sliwa JA , Clark GS , Chiodo A , et al. Burnout in Diplomates of the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation—Prevalence and Potential Drivers: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Survey. PM R. (2019) Jan;11: (1):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2018.07.013 |

[28] | Dean W , Talbot SG . Hard hits of distress. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. (2020) ;13: (1):3–5. doi: 10.3233/PRM-200017 |

[29] | Dean W , Talbot SG , Caplan A . Clarifying the Language of Clinician Distress. JAMA. (2020) Mar 10;323: (10):923–924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21576 |

[30] | Porter ME . What Is Value in Health Care? N Engl J Med. (2010) Dec 23;363: (26):2477–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024 |

[31] | Kim SS , Park BK . Patient-perceived communication styles of physicians in rehabilitation: the effect on patient satisfaction and compliance in Korea. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2008) Dec;87: (12):998–1005. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318186babf |

[32] | Ponsford MW , Bilszta JL , Olver J . Burnout in rehabilitation medicine trainees: a call for more research. Intern Med J. (2022) Mar;52: (3):495–499. doi: 10.1111/imj.15709 |

[33] | Kennedy GD , Tevis SE , Kent KC . Is there a relationship between patient satisfaction and favorable outcomes? Ann Surg. (2014) Oct;260: (4):592–8; discussion 598-600. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000932 |

[34] | Wallace JE . Mental health and stigma in the medical profession. Health (London). (2012) Jan;16: (1):3-–18. doi: 10.1177/1363459310371080 |

[35] | Saddawi-Konefka D , Brown A , Eisenhart I , Hicks K , Barrett E , Gold JA . Consistency Between State Medical License Applications and Recommendations Regarding Physician Mental Health. JAMA. (2018) Ma y18;325: (19):2017–2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2275 |

[36] | Gold KJ , Shih ER , Goldman EB , Schwenk TL . Do US Medical Licensing Applications Treat Mental and Physical Illness Equivalently? Fam Med. (2017) Jun;49: (6), 464–467. |

[37] | Dyrbye LN , West CP , Sinsky CA , Goeders LE , Satele DV , Shanafelt TD . Medical Licensure Questions and Physician Reluctance to Seek Care for Mental Health Conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. (2017) Oct;92: (10):1486–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.06.020 |

[38] | Remove Intrusive Mental Health Questions from Licensure and Credentialing Applications. Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation; 2023. Available from: https://drlornabreen.org/removebarriers/ |

[39] | Dunn LB , Green Hammond KA , Roberts LW . Delaying care, avoiding stigma: residents’ attitudes toward obtaining personal health care. Acad Med. (2009) Feb;84: (2):242–50. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819397e2 |

[40] | Dyrbye LN , Eacker A , Durning SJ , et al. The Impact of Stigma and Personal Experiences on the Help-Seeking Behaviors of Medical Students With Burnout. Acad Med. (2015) Jul;90: (7):961–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000655 |

[41] | Guille C , Speller H , Laff R , Epperson CN , Sen S . Utilization and barriers to mental health services among depressed medical interns: a prospective multisite study. J Grad Med Educ. (2010) Jun;2: (2):210–4. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00086.1 |

[42] | Brower KJ . Professional Stigma of Mental Health Issues: Physicians Are Both the Cause and Solution. Acad Med. (2021) May 1;96: (5):635–640. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003998 |

[43] | Ey S , Moffit M , Kinzie JM , Choi D , Girard DE . “If you build it,they will come”: attitudes of medical residents and fellows aboutseeking services in a resident wellness program. J Grad Med Educ. (2013) Sep;5: (3):486–92. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00048.1 |

[44] | Shen Y-C , Cunha JM , Williams TV . Time-varying associations of suicide with deployments, mental health conditions, and stressful life events among current and former US military personnel: a retrospective multivariate analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) Nov;3: (11):1039–1048. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30304-2 |

[45] | Goodwin RD , Dierker LC , Wu M , Galea S , Hoven CW , Weinberger AH . Trends in U.S. Depression Prevalence From 2015 to 2020: The Widening Treatment Gap. Am J Prev Med. (2022) Nov;63: (5):726–733. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.05.014 |

[46] | Rotenstein LS , Ramos MA , Torre M , et al. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA. (2016) Dec 6;316: (21):2214–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324 |

[47] | Brazeau CMLR , Shanafelt T , Durning SJ , et al. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med. (2014) Nov;89: (11):1520–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000482 |

[48] | Yaghmour NA , Brigham TP , Richter T , et al. Causes of Death of Residents in ACGME-Accredited Programs 2000 Through 2014: Implications for the Learning Environment. Acad Med. (2017) Jul;92: (7):976–983. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001736 |

[49] | ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2021 [updated 2022 July 1]. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programreq-uirements/cprresidency_2022v3.pdf |

[50] | ACGME Common Program Requirements (Fellowship). Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2021 [updated 2022 July 1]. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programreq-uirements/cprfellowship_2022v3.pdf |

[51] | GSA COSA Working Group on Medical Student Well-Being. UME Systemic Recommendations to Support Medical Student Well-being. Washington, D.C.: American Association of Medical Colleges; 2022. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/career-development/affinity-groups/gsa/cosa-working-group-medical-student-well-being. |

[52] | Vaa Stelling BE , West CP . Faculty Disclosure of Personal Mental Health History and Resident Physician Perceptions of Stigma Surrounding Mental Illness. Acad Med. (2021) May 1;96: (5):682–685. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003941 |

[53] | Practice Management: Physician Health. American Medical Association; 2023. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health |

[54] | 117th Congress. H.R.1667 - Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act. 117th Congress; 2021- 2022 [updated 2022 March 18]. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1667. |

[55] | Cordova MJ , Gimmler CE , Osterberg LG . Foster Well-being Throughout the Career Trajectory: A Developmental Model of Physician Resilience Training. Mayo Clin Proc. (2020) Dec;95: (12):2719–2733. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.002 |

[56] | Panagioti M , Panagopoulou E , Bower P , et al. Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. (2017) Feb 1;177: (2):195–205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674 |