The development of a lifetime care model in comprehensive spina bifida care

Abstract

PURPOSE:

To describe the development and implementation of the Children’s of Alabama (COA) Spina Bifida (SB) Lifetime-Care-Model, including standardized care protocols and transition plan.

METHODS:

In 2010, members of the pediatric team at COA began to evaluate limitations in access to care for patients with SB at various stages of life. Through clinic surveys, observations, and caregiver report, a Lifetime-Care-Model was developed and implemented. Partnerships were made with adult medicine colleagues to create an interdisciplinary model at each stage. Since developing this program, it has evolved to include standardized care protocols.

RESULTS:

Since 2011, there have been 42 prenatal clinics; 114 families received counseling and prenatal care. Of these, 106 have delivered at our center and established care in our pediatric clinic. There are currently 474 patients in the pediatric and 218 in the adult clinics.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our institutional experience suggests that patients with SB benefit from continuity of care throughout their lifetime. This article describes early failures which led to an evolution in approach and implementation of a Lifetime-Care-Model which results in a smooth transition between all phases of life. We hope that other institutions may adapt and build upon it to create programs unique to their specific patient needs.

1.Introduction

Spina bifida (SB) is the most common permanently disabling birth defect in the United States [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Prior to the 1970’s, the mortality was 38%; recent important advances in neurosurgery, genitourinary surgery, gastroenterology, and physical medicine and rehabilitation have contributed to improve survival such that 75–85% of individuals with SB now survive into adulthood [2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9]. However, this progress has created new challenges regarding where and how SB patients will receive optimal care as adults. Pediatric providers have a different spectrum of practice that does not include common adult diagnoses such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia and understandably limit their scope of practice accordingly [10, 11, 12]. Furthermore, the practicalities of hospital policy, liability, and 3

1.1Background

The pediatric SB team at Children’s of Alabama (COA) has provided longitudinal interdisciplinary comprehensive care for individuals and families with SB since 1993. Children’s of Alabama is an independent tertiary pediatric medical center that shares an academic relationship with the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Care in the pediatric SB clinic began at the time of diagnosis and continued through early adult years. For some families, this started with family counseling at the time of prenatal diagnosis of a neural tube defect (NTD), and for the remainder it began at the birth of an affected child. Maximizing the benefits of a multi-disciplinary care model has translated into improved quality of life and an extended lifespan [13, 14]. By 2008, COA had approximately 525 patients followed annually through the pediatric SB clinic. Prior to the development and adoption of the Lifetime Care Model there was not a systematic approach to prenatal visits, transition of care, or adult management. Typically, families affected by SB were unknown to us until after delivery of the affected child. Additionally, there was no coordinated method for aging individuals out of the pediatric clinic. There was a lack of standardization which resulted in variation in the age of transition. Adult care was fragmented and partnerships and collaborations had not been developed or nurtured.

Table 1

Demographic data on cohort followed through pediatric and adult spina bifida clinics 2008–2018

| All patients in pediatric clinic ( | All patients in adult/transition clinic ( | |

| Age in years, mean | 11 (range 2 months–21 years) | 32 (range 20 years–74 years) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 243 (51.3%) | 136 (62.4%) |

| Male | 231 (48.7%) | 74 (37.6%) |

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| Open myelomeningocele | 352 (74.3%) | 190 (87.2%) |

| Non-myelo (closed spina bifida) | 122 (25.7%) | 28 (12.8%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 330 (69.6%) | 178 (81.7%) |

| Black | 80 (16.9%) | 38 (17.4%) |

| Asian | 45 (9.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 19 (4.0%) | 2 (0.09%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 429 (90.5%) | 217 (99.6%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 45 (9.5%) | 1 (0.04%) |

| Functional lesion level | ||

| Thoracic (flaccid lower extremities) | 72 (15.2%) | 86 (39.4%) |

| High-lumbar (hip flexion present) | 41 (8.6%) | 28 (12.8%) |

| Mid-lumbar (knee extension present) | 110 (23.2%) | 42 (19.3%) |

| Low-lumbar (foot dorsiflexion present) | 73 (15.4%) | 19 (8.7%) |

| Sacral (foot plantarflexion present) | 178 (37.6%) | 43 (19.7%) |

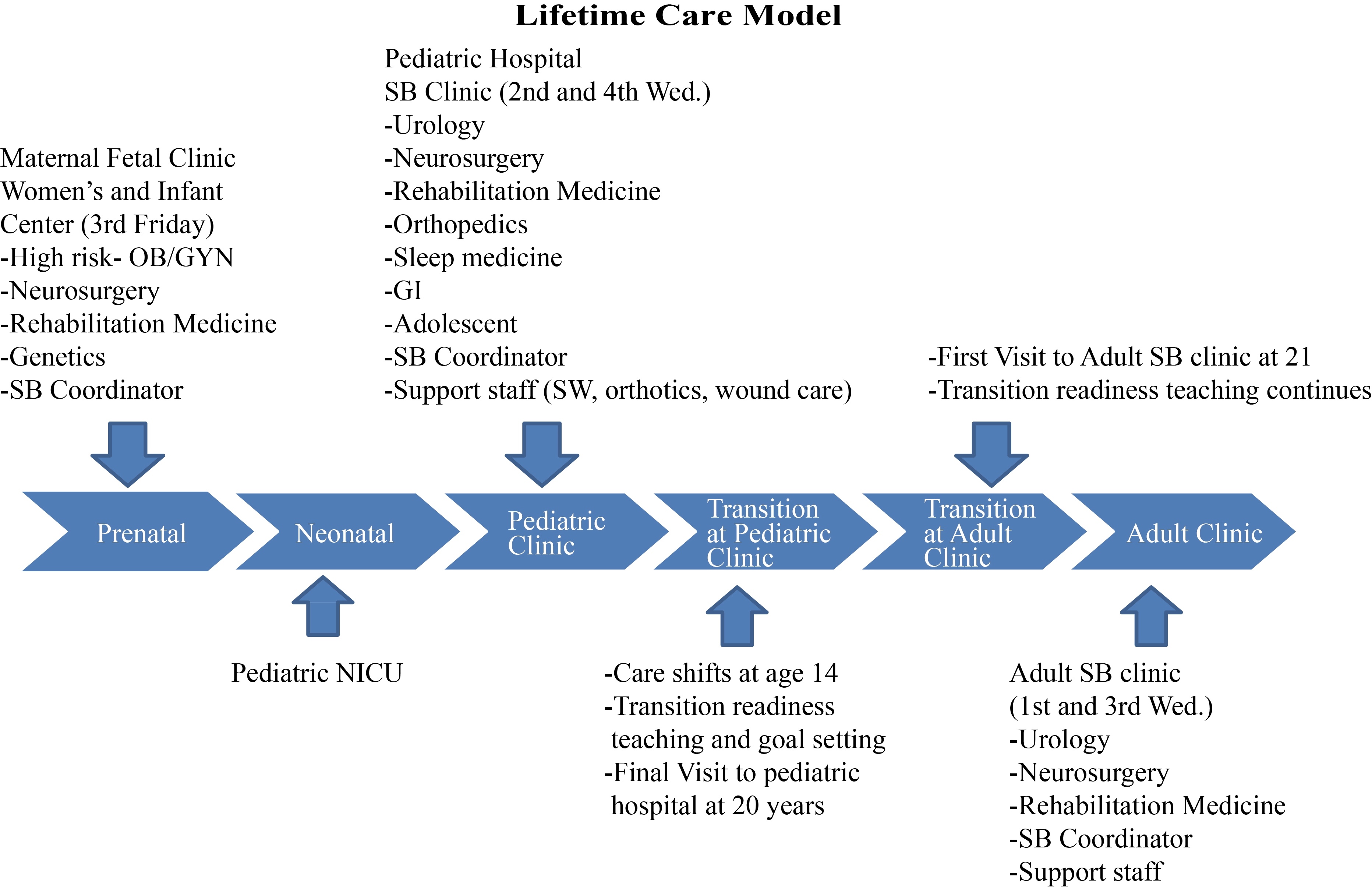

Figure 1.

Lifetime Care Model.

2.Methods

2.1The development of the lifetime care model

In 2010, we evaluated deficiencies in the care provided to patients in our pediatric clinic. Through clinic surveys, observations, caregiver reports, and a focus group meeting comprised of parents of children with SB, adults with SB, and community partners, we discovered that there were two periods where care was missing: prenatal counseling during pregnancy and the transitioning period of individuals with SB into adulthood. These results lead to a paradigm shift in our provision of care and the development of a lifetime care model (Fig. 1). This model represents a critical evolution from a SB pediatric clinic to a holistic SB program committed to lifetime care. In practical terms it became apparent that prenatal counseling, a proper transition protocol, and an adult interdisciplinary comprehensive care program were needed. Partnerships were developed with the Departments of Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFM), Adult Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R), and Adult Urology. The interdisciplinary adult SB clinic began in 2010 when the Medical Director (a pediatric neurosurgeon) and the pediatric SB program coordinator partnered with adult PM&R and adult urology within the context of an existing adult spinal cord injury clinic. From its inception, the model for these clinics strove to provide comprehensive continuity of care that emphasizes the value of each patient as a unique, autonomous individual. A close relationship with our local SB chapter (SBA of AL) has also proven to be beneficial in facilitating communication and nurturing relationships between the care team and the SB community.

3.Results

Since 2011, we have held 42 prenatal clinics in the multi-disciplinary maternal fetal clinic and 114 families have received counseling and prenatal care. Of these, 106 have gone on to deliver within our center and establish care in our pediatric clinic. Two of the families terminated the pregnancy, 4 were followed at another facility, and 2 were lost to follow up. There are 474 patients in the pediatric clinic and 218 in the adult clinic. Demographics of this cohort are detailed in Table 1. Eighty-six of the patients followed in the adult clinic were transitioned from COA (39.4%) since the development of our transition protocol. The majority of the patients seen in the adult clinic were patients who were previously lost to follow-up or received their pediatric care at other centers. Standardized protocols of care were created to the maximum extent possible to encompass the systems of care encountered by individuals with SB (Table 2).

3.1The spina bifida program

3.1.1Prenatal

The SB prenatal clinic meets monthly and is attended by physicians from MFM, pediatric neurosurgery, pediatric rehabilitation medicine, the SB program coordinator, genetic counselors, and nurse clinicians. These clinics are held as interdisciplinary “round table” discussions tailored specifically to the needs of the families instead of as one-on-one consultations. They are carefully conducted so as to promote immediacy and open communication yet retain their fundamental multi-disciplinary content. As such, the goal has been to simultaneously optimize expertise and encourage sensitivity. The MFM physician addresses issues related specifically to pregnancy and delivery. The neurosurgeon discusses neurologic prognosis and surgical treatments including placode closure and hydrocephalus management. The PM&R physician provides information related to the child’s estimated neurologic capabilities and necessary care directed to support those abilities. Families are provided with educational materials and contact information for state resources available to individuals with special health care needs. Families are offered a tour of the COA Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and given information on our care protocols. The coordinator provides an overview of multi-disciplinary care and serves as a central point of contact for coordination of care. This role is central to the success of the overall program as the complexity of the medical issues and the multi-disciplinary care that treats them is often overwhelming, confusing, and intimidating.

3.1.2Neonatal

After delivery, infants are admitted to the NICU and an echocardiogram and an ultrasound of the kidneys and bladder is performed. Myelomeningocele closure is performed within 48 hours unless a co-existent lethal anomaly is detected. Thereafter, daily clinical examinations are performed to determine the need for hydrocephalus intervention. An MRI scan of the brain and spine is performed to obtain a baseline assessment of each child’s specific neuroanatomy. A bladder-management protocol is initiated, including clean intermittent catheterization (CIC). Orthopedic assessment includes scoliosis X-rays, a hip ultrasound, and treatment recommendations for foot deformities. Family support and new patient teaching is provided to the parents by the SB program coordinator. The “New Parent Journal” and monographs available from the Spina Bifida Association are distributed to each new family. The “New Parent Journal” is a medical diary we created to provide families with a mechanism to track all health information in real time. The family also receives shunt teaching, latex allergy precautions, car seat instructions, teaching with physical therapy staff, and referral to Early Intervention services before discharge. Finally, families are provided follow-up appointments which typically include a neurosurgery “wound check” appointment two weeks after discharge and a multidisciplinary SB Clinic appointment within three months which includes urodynamic testing. The typical length of stay after delivery for the infant is 2–4 weeks.

3.1.3Pediatric

The pediatric SB clinic meets twice a month and is comprised of providers from pediatric rehabilitation medicine, pediatric neurosurgery, pediatric urology, pediatric orthopedics, pediatric gastroenterology, pediatric sleep medicine, adolescent medicine, nursing, care management/care coordinator, social work, physical therapy, orthotics, nutrition, and research support staff. Children are typically seen in this clinic every 3 months for the first year of life, every 6 months from years 1–5, and annually after the age of 5. Preferred protocols for surveillance testing in the pediatric SB clinic are summarized in Table 2.

Developmental milestones are assessed at each visit by pediatric rehabilitation medicine and appropriate referrals are made for early intervention or outpatient therapy. An academic and educational history is taken as appropriate based on age, including assessment of academic performance, special education services, or school-based therapy services. Additional neuropsychological testing is frequently ordered to further evaluate any behavioral or cognitive challenges that the child may be experiencing at school or in the home.

After each clinic there is a post-visit multidisciplinary care review, in which providers from multiple disciplines discuss each patient individually and care plans are developed and coordinated in an interdisciplinary fashion. It is an explicit goal of the clinic to create an atmosphere where patients and families are active participants in their wellness and care and are provided with useful, practical information and teaching. We strive to utilize their time in clinic to optimize the amount of resources and education provided. A letter from each discipline is then sent to the patients’ primary care physician at the end of each visit. In addition, there is a dedicated, published telephone line for the SB program that is shared with referring providers’ offices which results in an average volume of 5–8 telephone calls per week.

3.1.4Adolescence

The focus during adolescence is to begin to foster

Table 2

Spina bifida – plan of care guidelines

| Before initial | First SBC visit | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | 1–5 years | 6 years–13 years | 13 years–21 years | 21 | |

| discharge from | 3 months post | ||||||||

| hospital | discharge | ||||||||

| Vital signsassessment | HC for 2 yrs | Height/weight protocol followed HC for 2 yrs | Height/weight protocol followed HC for 2 yrs | Height/weight protocol followed HC for 2 yrs | Height/weight protocol followed HC for 2 yrs | Height/weight protocol followed HC for 2 yrs | Height/weight protocol followed HC for 2 yrs | Height/weight protocol followed HC for 2 yrs | Height/weight protocol followed HC for 2 yrs |

| Consults(specialties) | Neurosurgery,urology, orthopedics, physical therapy | Neurosurgery, urology, orthopedics, rehab medicine | Neurosurgery, urology, orthopedics, rehab medicine, GI | Neurosurgery, urology, rehabmedicine | Neurosurgery, urology, orthopedics, rehab medicine, GI | Neurosurgery, urology, orthopedics, rehab medicine, GI | Neurosurgery, urology, orthopedics, rehab medicine, GI | Neurosurgery, urology, orthopedics, rehab medicine, GI | Neurosurgery, urology, rehabmedicine |

| Tests | Head CT (asindicated byNSU) renal u/s, hip ultrasounds | FS MRI, urodynamics, RUS, DMSA, FBP, AP/ Lat scoli, AP pelvis headcircumference recorded | RUS, AP pelvis, head circumference recorded, order sleep study to be done before age 5 | RUS, head circumference recorded, FS MRI | RUS, AP pelvis, head circumference recorded | FS MRI everyother appt. until age 5, RUS every 6 months, UDS isyearly unless hostile bladder is identified then every 6 months (urology protocol is followed), scoli and pelvis films annually based on physician order | RUS, KUB (ifhome cath) annually, FS MRI every other year, scoli films as ordered, UDS repeated with concerns of tethered cord, or when developingcontinence program | RUS, KUB (ifhome cath) annually, FS MRI every other year, scoli films as ordered, UDS repeated with concerns of tethered cord, or when developingcontinence program, order sleep study to be repeated after age 15 | RUS, KUB, UDS as indicated |

| Treatmentsand medications | Urology protocol, hydrocephalus management | Urology protocolbeing followed;hydrocephalus management being followed | Urology protocolbeing followed;hydrocephalus management being followed.Initiate bowelprogram | Urology protocolbeing followed;hydrocephalus management being followed.Follow bowelprogram | Urology protocolbeing followed;hydrocephalus management being followed.Follow bowelprogram | Ophthalmology, social workers,speech, skin care, early puberty,neuropsychology, seizures, mentalhealth (especially depression andanxiety), or dietitian as indicated. Order sleep study before age 5. Order neuropsych in 1st grade. Follow bowel program | Ophthalmology, social workers,speech, skin care, early puberty,neuropsychology, seizures, mentalhealth (especially depression andanxiety), or dietitian as indicated. Order sleeps study after age 15.Follow bowel program | Begin administering PHQ9, TRAQ, family impact,teen screen.Follow bowel program | Continue TRAQand ITP through 30th year. Follow bowel program |

Figure 2.

Individualized Transition Plan (ITP). Modeled after Sample Plan of Care from gottransition.org.

|

Table 2, continued | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before initial | First SBC visit | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | 1–5 years | 6 years–13 years | 13 years–21 years | 21 | |

| discharge from | 3 months post | ||||||||

| hospital | discharge | ||||||||

| Activity | Regular activity astolerated, unlessotherwise indicated by MD | Exercise daily | Exercise daily | Exercise daily | Exercise daily | Exercise daily | Exercise daily | Maintains or increases activity levels and functionality to fullest potential levels | Maintains or increases activity levels and functionality to fullest potential levels |

| Teaching | Latex, shunt, folic acid, catheter training, bowel management, basic knowledge of SB,New parent journal and Health Guide for Parents given and reviewed | Bowel mgmt,weight mgmt,shunt teachingreviewed, cathteaching reviewed, new parentjournal reviewed | Bowel mgmt,weight mgmt,shunt teachingreviewed, cathteaching reviewed, new parentjournal reviewed | Bowel mgmt,weight mgmt,shunt teachingreviewed, cathteaching reviewed, new parentjournal reviewed | Bowel mgmt,weight mgmt,shunt teachingreviewed, cathteaching reviewed, new parentjournal reviewed | Bowel management, locate community activities, new parent journal reviewed | Bowel management, locate community activities, new parent journal reviewed | Transition teachingbegins. DevelopITP, Ensure working bowel program | Ensure workingbowel program,maximize education. Job training |

| D/C planning casemanagement | EI referral made, NSU wound check appt. scheduled,first SBC appt,scheduled, Urodynamics scheduled, SBC Doctors assigned, emergency plan reviewed | Follow up appts will be mailedthe day after the visit along with referrals as indicated by MD | Follow up appts will be mailedthe day after the visit along with referrals as indicated by MD | Follow up appts will be mailedthe day after the visit along with referrals as indicated by MD | Follow up appts will be mailedthe day after the visit along with referrals as indicated by MD | Follow up appts will be mailed the day after the visit along with referrals as indicated by MD. Recommend school based therapy at age 3 | Follow up appts will be mailedthe day after the visit along with referrals as indicated by MD | Follow up appts will be mailedthe day after the visit along with referrals as indicated by MD | Follow up appointments made prior to leaving clinic |

| Psychosocial | Pt and or caregiver possess basic knowledge of SB and treatment options | Knowledge increases with reinforcement | Knowledge increases with reinforcement | Knowledge increases with reinforcement | Knowledge increases with reinforcement | Maintains positive coping skills and support system | Maintains positive coping skills and support system | Begin future planning through ITP | Maintains positive coping skills and support system |

| Other interventions | SBA of AL information reviewed, phone numbers of SB parents in AL, CRS information given, Ronald McDonald House and transportation reviewed | Maintains reliable transportation and adaptive devices, ensure patient is receiving early intervention | Maintains reliable transportation and adaptive devices, ensure patient is receiving early intervention | Maintains reliable transportation and adaptive devices, ensure patient is receiving early intervention | Maintains reliable transportation and adaptive devices, ensure patient is receiving early intervention | Maintains reliable transportation and adaptive devices, ensure patient is receiving earlyintervention, determine familyneeds and provide assistance | Maintains reliable transportation and adaptive devices, ensure patient is receiving earlyintervention, determine familyneeds and provide assistance | Drivingassessment, IEPassistance | Maintains reliable transportation and adaptive devices |

| Follow-up plan | 3 months | 3 months | 3 months | 3 months | 3 months | 6 months until age 5 | Every year unless otherwise noted | Every year unless otherwise noted | Every year unless otherwise noted |

Abbreviations used in table for space: HC

Individualized Transition Plan (ITP)

This plan will be developed with your Spina Bifida team and it will become part of your medical record.

Name: Date of Birth:

Primary Diagnosis: Secondary Diagnosis:

| Prioritized Goals | Current Status/Plans | Actions | Target Date | Date Complete |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maximize Education | ||||

| 2. Working Bowel Program | ||||

| 3. | ||||

| 4. | ||||

| 5. |

Initial Date of Plan: Last Updated: Transitioning Patient Signature:

Parent/Caregiver Signature: Clinician Signature: Clinician Phone:

independence. Our goal for this group is to provide a comfortable environment, where patients feel free to ask questions and are secure to begin handling their own self-care needs. Focus is placed on school, adolescent health, secondary sexual development, menstrual period management, and early sexual behavior issues. These visits include evaluation by an Adolescent Medicine Physician. Importantly, during this period, we begin some physician interactions with adolescents without a parent present. This experience is meant to prepare individuals for an adult model of healthcare, in which patients must take increasing responsibility for their own care rather than relying solely upon caregivers and parents.

3.1.5Transitioning to adult care

Our protocol for transition readiness and education has grown from our experiences in the adult SB clinic. We performed an analysis of factors related to adults with SB self-identifying as disabled. Results showed that 56.4% identified themselves as permanently disabled, with the most important predictors of disability being poor bowel continence and low education [8, 25]. These findings were incorporated into the pediatric transition protocol. Transition readiness assessment begins at age 13. At each annual SB clinic visit, from age 13 to 30, we administer the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ), which is a validated, quantitative measure of a patient’s readiness for adult medical care. The results of the TRAQ allow us to individualize our approach to transition education needs. Transition education is provided through the Individualized Transition Plan (ITP) (Fig. 3.1.4). Although the transition plan is standardized to the clinical practice, it is also individualized to the patient. The ITP’s role for transition to adult medical care is analogous to the Individualized Education Program (IEP) in the educational process at the grade school level. At age 13, each patient completes his or her first TRAQ. In the next annual visit, patients receive their first ITP.

The ITP is comprised of 5 measurable goals with action items to achieve those goals. The first two goals on each ITP are geared towards maximizing education and establishing a working bowel continence program. These goals are based on the results of our own disability study. The clinic coordinator uses the results from the TRAQ and information gathered from the patient/caregiver to develop a third, measurable, patient-specific goal. The fourth goal is identified by the caregiver and the fifth goal is developed by the transitioning patient. The ITP becomes part of the patients’ medical record and each year the clinic coordinator reviews progress and sets new measurable goals.

After the last pediatric clinic visit at the age of 20, referrals are made to the adult SB Clinic, and medical records and imaging studies are transferred to the adult clinic. The first visit to the adult clinic happens at age 21. Patients are then followed through this clinic lifelong and receive coordinated care through their lifetime in the adult environment. The SB Program Coordinator as well as the SB Medical Director (a Pediatric Neurosurgeon) attend and staff both clinics which creates a continuity of care and familiarity with the patients. Pediatric providers remain available during adult clinic to answer questions as they arise.

Figure 3.

Components of Initial Intake History, Physical Examination, and Health Review during initial Adult Spina Bifida Clinic.

Components included in adult SBC visit:

• Recent Shunt Revisions

• Physical Exam with Motor and Sensory Status (Neurological Exam)

• Pain or Spasticity

• Skin Breakdowns or Pressure Ulcers

• Bladder Program

• Bowel Program

• Nutrition and Dietary Needs

• Evaluate for Sleep Apnea

• HPV Vaccines

For females:

• Menstrual Cycles and LMP

• Reproductive Function and Pregnancy

• Birth Control

• Breast Exams and PAP Smears

• Sexual Abuse

During or at the end of the visit – DME needs such as:

• Wheelchair/Cushion (New and Repairs)

• Ankle foot orthotics

• Knee foot orthotics

If at any point during the transition period the patient becomes sick or needs surgical intervention, their needs are addressed in the pediatric health care system. We believe that efforts to transition patients with active medical issues are unlikely to be successful and may compromise the success of the program. If the active medical issues extend beyond the patient’s 21

Figure 4.

Preferred protocols for surveillance testing in Adult Spina Bifida Clinic. Paradigms have arisen from provider and published clinical experience.

Preferred protocol for surveillance testing includes:

|

3.1.6Adult care

The Care Coordinator initiates transition by scheduling the patient for a visit at the adult SB Clinic. The patient’s first transitional visit is a comprehensive exam that is performed by the physiatrists and their nurses (Fig. 3). Studies are completed in the mornings and the results are reviewed and explained with each patient and their caregiver, provided the patient has given verbal consent for the caregiver to remain in the room. It is important that the patient realizes that they are the patient, and that they are expected to conduct an informed, forthright discussion of their own medical history. At this visit, depending on their cognitive and functional maturity, the patient likely becomes their own advocate for their healthcare needs. The emphasis is now focused on ‘independence’ rather than ‘dependence’. Transitioning from pediatrics to adult care is understandably difficult, but we insist that our patients establish a primary care provider (PCP) to oversee their continuity of care. Our team maintains an active list of regional and state wide primary care physicians and works to facilitate communication between our patients and PCPs.

The adult SB Clinic currently meets twice a month. These visits continue annually for the first 5 years after transition and may be extended to 18–24 months interval based on patient’s progress with transition and their medical needs. Surveillance studies to support clinic visits are outlined in Fig. 4.

3.2Data collection for research and quality improvement

Patients in both pediatric and adult clinics are enrolled in the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry (NSBPR http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/spinabifida/nsbprregistry.html) during routine clinical care [27, 28, 29]. TRAQ data and the development of the ITP are included at the designated clinic ages. Data collected as part of the NSBPR are used in quality improvement studies, to understand patient outcomes, and to make modifications to the SB transition program.

4.Discussion

We have found that the needs of the transition population are complex, multi-factorial and varied. They center on themes of autonomy, mutual respect and expectations that the patient will take on greater independence in their own care [4, 20, 23]. The process for establishing an adult clinic not only includes identifying a suitable location and adult providers but also recognizing that the best care is delivered in a paradigm that emphasizes holistic lifelong care [4, 15, 22]. We embrace a lifetime care model because it promotes independence of the patient and prepares the patient and family for current and future needs within a context of care that emphasizes the value of each patient as a unique, autonomous individual. Defining the age of transition based on behavior or other arbitrary metrics is neither appropriate nor optimal [4, 24]. The capability for transition must be developed over years and involve the patient, family, and care team. In this context, the logistical transfer of care from the pediatric to the adult environment is triggered by an actual chronological age but occurs as a culmination of a carefully developed incremental process [20, 23, 30].

We have also learned that transitioning from pediatric to adult care requires both transfer of care and transition of responsibility. This process does not happen quickly or easily. Considerable learning and growth must take place within the patient and the family.

Medical complexity fosters lifelong physical and psychological dependence upon caregivers [20, 24, 28]. Caregivers grow accustomed to meeting exceptional needs and being depended upon. Despite being guided by well-constructed ITPs and harboring the goal of greater potential for independence and fulfillment, the transition process is typically challenging and stressful for patients and caregivers alike. Adult patients’ needs are different than those of childhood and require different services and models of care to optimize support [24, 31]. Reciprocal communication between the pediatric and adult care providers must be continuously nurtured and encouraged. The outcomes and challenges in the adult clinic should shape and direct quality improvement efforts in the pediatric clinic.

There are several gender-specific issues that substantially impact transition. Females with SB often demonstrate development of secondary sexual characteristics and puberty between the ages of 10 and 12 which is somewhat earlier than non-affected women [21, 22, 30, 33]. Our patients and families were consistently unaware of these issues and other related issues fundamental to women’s health such as fertility, pregnancy capability, and sexual evolution to maturity. Most patients and many families had limited or no basic awareness of the physiologic capability of women with SB to conceive and bear children after the onset of menarche. Some felt that SB itself conferred sterility and was an inherently reliable form of contraception. Other important issues that represented evolution of the current transition model included risk of abuse due to a daily need for bladder catheterization and the natural development of sexual awareness.

Therefore, the topics of sexual readiness, sexual activity, birth control, sexually transmitted diseases, and sexual abuse must be addressed prior to transition to adult care [20, 21, 32]. Some prophylactic measures may be started as early as 12 years of age (i.e., HPV vaccine) but the overall process is a gradual one that begins in early adolescence and continues through transition.

To truly optimize transition and adult care, it is crucial to address specific problems such as depression, social isolation, physical pain, and desire for work [19, 30]. Solving the physical location of where patients will receive their care as adults is an important but ultimately logistical first step. Finding willing adult providers is an important but in and of itself insufficient second step. By contrast, an ITP-driven program builds knowledge, confidence, and a relationship with an interdisciplinary care team. The transition model must seek strategies for helping patients maximize their learning, capacity to work, and sense of being a functional contributor to society in order to improve their overall quality of life [22, 24, 30]. The transition model has to be standardized and agreed upon by all parties in order to be effective. It should be specific to the clinic and individualized to the patient.

Finally, we have found that having a knowledgeable, compassionate, approachable coordinator is central to the success of the Lifetime Care Model. While the program coordinator is central to the effort and imparts great impact on the overall success of the program, the program must be structured in such a way as to not be dependent on any given individual. Important steps in assuring this difficult component include standardizing policies, procedures and protocols that guide clinical care. In addition, we have constructed specific manuals that detail the daily and weekly logistic tasks that are essential to a smooth clinic operation.

See Appendix 1 for a detailed list of early failures and lessons learned.

5.Conclusions

SB is one of the most complex chronic medical conditions compatible with life through adulthood. As comprehensive, interdisciplinary care has improved survival, new needs have arisen. The purpose of this report is to describe our institutional experience in providing SB care to children and adults. Early failures led to an evolution in approach and paradigms which we have collectively called the Lifetime Care Model. To do this, we have developed standard care protocols from prenatal diagnosis to adulthood, and developed a process to facilitate a smooth transition between all phases of life. Our SB transition protocol is not a universal solution but rather represents one model that has been successful in transition. We hope that other institutions may adapt and build upon it to create programs unique to their specific patient needs.

Acknowledgments

Betsy Hopson’s research has been supported by the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry Project (NSBPR). Dr. Rocque’s research has been supported by NIH Grant 1KL2TR001419, and by the Kaul Pediatric Research Institute of Children’s of Alabama.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not have any conflict of interest to report. This specific project did not have any funding.

References

[1] | Bowman RM, McLone DG, Grant JA, Tomita T, Ito JA. Spina bifida outcome: A 25 year prospective. Pediatr Neurosurg (2001) ; 34: : 114-120. |

[2] | McLone DG. Results of treatment of children born with a myelomeningocele. Clin Neurosurg (1983) ; 30: : 407-12. |

[3] | Oakeshott P, Hunt G, Kerry S, Strauss DJ, Shavelle RM, Reynolds RJ. Survival and mobility in open spina bifida: Comparison of results from the United States and United Kingdom. Int J Disabil Hum Dev (2008) ; 7: : 101-106. |

[4] | Piatt J. Treatment of myelomeningocele: A review of outcomes and continuing neurosurgical considerations among adults. J Neurosurg Pediatrics (2010) ; 6: : 515-25. |

[5] | Shin M, Besser LM, Siffel C, Kucik JE, Shaw GM, Lu C, et al. Prevalence of spina bifida among children and adolescents in 10 regions in the United States. Pediatrics (2010) ; 126: : 274-9. |

[6] | Bakaniene I, Prasauskiene A, Vaiciene-Magistris N. Health-related quality of life in children with myelomeningocele: a systematic review of the literature. Child Care Health Dev (2016) ; 42: (5): 625-43. |

[7] | Lorber J. Spina bifida cystica. Results of treatment of 270 consecutive cases with criteria for selection for the future. Arch Dis Child (1972) ; 47: (256): 854-73. |

[8] | Rocque BG, Bishop ER, Scogin MA, Hopson BD, Arynchyna A, Boddiford CJ, et al. Assessing health related quality of life in children with Spina Bifida. J Neurosurg Pediatr (2015) ; 15: : 144-9. |

[9] | Talamonti G, D’Aliberti G, Collice M. Myelomeningocele: Long-term neurosurgical treatment and follow-up in 202 patients. J Neurosurg (2007) ; 107: : 368-86. |

[10] | American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians, American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics (2002) ; 110: (6): 1304-6. |

[11] | Binks JA, Barden WS, Burke TA, Young NL. What do we really know about the transition to adult centered health care? A focus on cerebral palsy and spina bifida. Arch Phys Med Rehabil (2007) ; 88: : 1064-73. |

[12] | Colver AF, Merrick H, Deverill M. Study protocol: Longitudinal study of the transition of young people with complex health needs from child to adult health services. BMC Public Health (2013) ; 13: (1): 675. |

[13] | Al-Hazmi HH, Trbay MS, Gomha AB, Elderwy AA, Khatab AJ, Neel KFU. Nephrological outcomes of patients with neural tube defects: Does a spina bifida clinic make a difference? Saudi Med J (2014) ; 35: (1): S64-S67. |

[14] | Kaufman BA, Terbrock A, Winters N, Ito J, Klosterman A, Park JS. Disbanding a multidisciplinary clinic: Effects on the health care of myelomeningocele patients. Pediatr Neurosurg (1994) ; 21: (1): 36-44. |

[15] | Vinchon M, Dhellemmes P. The transition from child to adult in neurosurgery. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg (2007) ; 32: : 3-24. |

[16] | Aguilera DM, Wood DL, Keely C, James HE, Aldana PR. Young adults with spina bifida transitioned to a medical home: A survey of medical care in Jacksonville, Florida. J Neurosurg Pediatr (2016) ; 17: : 203-7. |

[17] | Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: A systematic review. Arch Dis Child (2011) ; 96: (6): 548-53. |

[18] | Freeman KA, Castillo H, Castillo J, Liu T, Schecter M, Wiener JS, et al. Variation in bowel and bladder continence across US spina bifida programs: A descriptive study. J Pediatr Rehabil Med (2017) ; 10: (3-4): 231-41. |

[19] | Mahmood D, Dicianno B, Bellin M. Self-management, preventable conditions and assessment of care among young adults with myelomeningocele. Child Care Health Dev (2011) ; 37: (6): 861-65. |

[20] | Sawin KJ, Rauen K, Bartelt T, Wilson A, O’Connor RC, Waring WP, et al. Transitioning adolescents and young adults with spina bifida to adult healthcare: Initial findings from a model program. Rehabil Nurs (2014) ; 17: : 1-9. |

[21] | Dicianno BE, Bellin MH, Zabel AT. Spina bifida and mobility in the transition years. Am J Phys Med Rehabil (2009) ; 88: (12): 1002-6. |

[22] | Le JT, Mukherjee S. Transition to adult care for patients with spina bifida. Phys Med Rehab Clin N America (2015) ; 26: (1): 29-38. |

[23] | Kelly MS, Thibadeau J, Struwe S, Ramen L, Ouyang L, Routh J. Evaluation of spina bifida transitional care practices in the United States. J Pediatr Rehabil Med (2017) ; 10: (3-4): 275-281. |

[24] | Rekate HL. The pediatric neurosurgical patient: The challenge of growing up. Semin Pediatr Neurol (2009) ; 16: : 2-8. |

[25] | Davis MC, Hopson BD, Blount JP, Carrol R, Wilson TS, Powell DK, et al. Predictors of permanent disability among adults with spinal dysraphism. J Neurosurg Spine (2017) ; 27: : 169-77. |

[26] | Dupepe EB, Hopson B, Johnston JM, Rozzelle CJ, Oakes WJ, Blount JP, et al. Rate of shunt revision as a function of age in patients with shunted hydrocephalus due to myelomeningocele. Neurosurg Focus (2016) ; 41: (5): E6. |

[27] | Sawin KJ, Liu T, Ward E, Thibadeau J, Schechter S, Soe MM, et al. The National Spina Bifida Patient Registry: Profile of a large cohort of participants from the first 10 clinics. J Pediatr (2015) ; 166: (2): 444-50, e441. |

[28] | Wang JC, Lai CJ, Wong TT, Liang ML, Chen HH, Chan RC, et al. Health related quality of life in children and adolescents with spinal dysraphism: Results from a Taiwanese sample. Childs Nervous Syst (2013) ; 29: : 1671-79. |

[29] | Thibadeau JK, Ward EA, Soe MM, Liu T, Swanson M, Sawin KJ, et al. Testing the feasibility of a National Spina Bifida Patient Registry. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol (2013) ; 97: (1): 36-41. |

[30] | Mukherjee S. Transition to adult health care for adolescents with spina bifida: Research issues. Scientific World Journal (2007) ; 7: : 1890-95. |

[31] | Young NL, McCormick A, Mills W, Barden W, Boydell K, Law M, et al. The Transitions Study: A look at youth and adults with cerebral palsy, spina bifida and acquired brain injury. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr (2006) ; 26: (4): 25-45. |

[32] | Grimsby GM, Burgess R, Culver S, Schlomer BJ, Jacobs MA. Barriers to transition in young adults with neurogenic bladder. J Pediatr Urol (2016) ; 12: (4): 258-61. |

[33] | Menstruation in Girls and Adolescents: Using the Menstrual Cycle as a Vital Sign. Committee Opinion No. 651. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol (2015) . |

Appendices

Appendix 1: List of early failures and lessons learned during the process of Lifetime Care Model Development

Early failures:

1– Despite a prolonged institutional/program commitment to patients with dysraphism, our program initially had important domains of care for which no support or care was provided. Profound disparities of care existed in supporting these critical domains. These included prenatal consultation and transitional care.

2– Transition was based on subjective behavior thresholds of “adult-like behavior” (e.g., tattoos, smoking, pregnancy, high school graduation, etc.) instead of a chronological age. This made it very difficult to inform patients/caregivers of how long they could be followed in the pediatric facility.

3– We did not have partnerships with adult providers in our area or a presence of continuity in the adult environment.

4– Initially our prenatal SB consults were routinely scheduled into the regular Pediatric Neurosurgery Clinic. These clinics were not optimally structured to support the unique needs of a prenatal visit with a serious diagnosis and resulted in frustration and increased isolation for the families.

5– We had no indication or planning process to ensure that patients were ready for adult living or adult healthcare.

6– The culture of care provision in the adult environment was different and education of the entire support staff including nursing and administrative support was needed to assure availability of adult providers.

7– After the transition program was developed, we initially began teaching at age 19. This proved to be too late and did not leave enough time to prepare them for transition. We have evolved to initiating preparation for transition at age 14.

Lessons learned/changes implemented:

1– Transition should be individualized to the patient but standardized to the program. Each transitioning patient has unique needs which require patient specific goals to ensure their readiness for transition. The age of transition should be consistent across patients.

2– Transition involves more than finding a location for clinic. Instead, the most important component involves a plan to ensure readiness that begins in adolescence and incorporates important provisions of self-care.

3– Reciprocal communication between pediatric and adult teams is necessary. Ideally, the pediatric team will remain available to answer questions and provide historical information to the adult team. It is also critically important that the adult team provide the pediatric team with outcome data on their patients to help refine the framework for education and priorities of care (e.g., bowel management) during the pediatric years.

4– Educating patients to understand and communicate their health care needs with adult providers is an important but challenging task in the transition process.

5– Sexuality should be discussed and addressed during the transition process and prior to the patient arriving in the adult facility.